Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) has the potential to significantly advance the management of nonpoint source pollution (NPSP), a critical environmental issue characterized by diffuse sources and complex transport mechanisms. This study systematically examines current AI applications addressing NPSP through bibliometric and systematic analyses. A total of 124 studies were included after rigorous identification, screening, and eligibility assessments based on the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) framework. Key findings from the bibliometric analysis include publication trends, regional research contributions, author and journal contributions, and core concepts in NPSP. The systematic analysis further provided: (a) a comprehensive synthesis of NPSP characterization, covering pollution sources, key drivers, pollutants, transport pathways, and environmental impacts; (b) identification of emerging AI technologies such as the Internet of Things, unmanned aerial vehicles, and geographic information systems, and their potential applications in NPSP contexts; (c) a detailed classification of AI models used in NPSP assessment, highlighting predictors, predictands, and performance metrics specifically in water quality prediction and monitoring, groundwater vulnerability mapping, and pollutant-specific modeling; and (d) a critical assessment of knowledge gaps categorized into AI model development and validation, data constraints, governance and policy challenges, and system integration, alongside proposed targeted future research directions emphasizing adaptive governance, transparent AI modeling, and interdisciplinary collaboration. The findings from this study provide essential insights for researchers, policymakers, environmental managers, and communities aiming to implement AI-driven strategies to mitigate NPSP.

1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a transformative technology with applications across various domains, such as climate change modeling [1], hydrometeorological forecasting (e.g., temperature and precipitation) [2,3], waste and water resource management [4,5,6], and pollution detection [7]. Through its ability to process and analyze vast and complex datasets, AI supports predictive analytics, pattern recognition, and decision-support systems, enabling more effective mitigation strategies [8,9]. For example, Zulkifli et al. [10] developed AI-based predictive models for pollutant loads and their impact on water bodies, allowing for proactive planning and targeted pollution control measures. By analyzing complex relationships between critical factors (e.g., slope, land cover, runoff, rainfall intensity), AI can assist in optimizing management strategies, such as identifying the most effective land use practices or suggesting the location of best management practices to minimize pollutant runoff [9,11]. Given its potential, AI is increasingly being explored as a solution to one of the most persistent and complex environmental challenges: nonpoint source pollution (NPSP).

NPSP has emerged as one of the most critical threats to both ecosystems and the management of water resources [12,13,14]. NPSP refers to pollution that originates from multiple diffuse sources, such as land surfaces or the atmosphere, rather than a single, identifiable point. It is typically carried by rainfall or snowmelt as it moves over or through the ground, eventually entering lakes, rivers, wetlands, coastal waters, and underground water resources. The source and magnitude of pollution cannot be accurately identified. This makes it a leading threat to water quality and one of the most challenging forms of water pollution to manage globally [15,16]. From a scientific and technical perspective, NPSP refers to the diffuse discharge of pollutants into the environment from multiple sources such as agricultural lands, urban stormwater runoff, and atmospheric deposition, making it inherently challenging to monitor and mitigate effectively. Agriculture is currently a major contributor to NPSP with activities such as livestock and poultry breeding, field irrigation, and excessive use of pesticides and fertilizers [17]. Despite thorough exploration and diligent efforts, viable and scalable solutions for addressing NPSP remain elusive [12,18]. Researchers have embraced interdisciplinary research methods integrating AI and associated technologies (e.g., Internet of Things (IoT), drones, remote sensing, Geographic Information System (GIS), satellites) to address the systemic complexity of NPSP and support more adaptive management strategies [19,20,21,22]. However, despite growing interest in AI applications in NPSP research, their practical implementation remains limited.

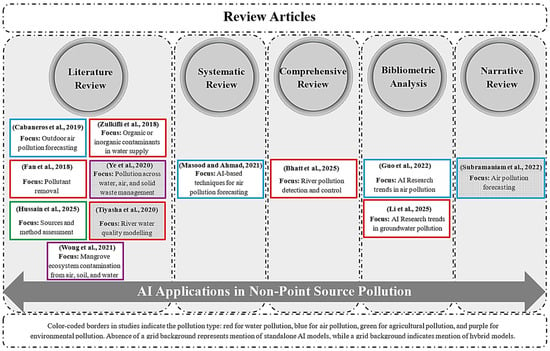

To date, while AI has been widely applied in environmental pollution research, only a limited number of review studies have specifically addressed its applications in NPSP. These review articles are summarized in Figure 1 and Supplementary Table S1. They either cover a wide range of pollution types, from air and water to agricultural and multi-environmental contexts, or adopt a broad approach without directly referencing NPSP. The reviews vary in format, including bibliometric, systematic, comprehensive, and narrative methods, and address diverse pollution types, ranging from air and water to agricultural and multi-environmental contexts. For example, Cabaneros et al. [23] reviewed standalone AI models for air pollution forecasting, while Fan et al. [24] assessed hybrid artificial neural network (ANN) models for pollutant removal in water treatment. Hussain et al. [25] examined the role of AI, remote sensing, and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) in supporting data-driven mitigation strategies in agricultural pollution. Zulkifli et al. [10] focused on AI-based detection of contaminants in water supply systems using wireless sensor networks. Tiyasha et al. [26] traced the evolution of AI models for river water quality modeling, highlighting a shift toward hybrid and ensemble techniques. Similarly, Wong et al. [27] explored the use of back propagation neural network (BPNN) and support vector machine (SVM) in analyzing pollutant interactions across air, soil, and water in mangrove ecosystems. Ye et al. [28] investigated AI applications in wastewater treatment and early warning systems, while Bhatt et al. [29] evaluated deep learning (DL) models for real-time river pollution control. Additionally, bibliometric reviews by Guo et al. [30] and Li et al. [31] have explored AI trends in air pollution and machine learning in groundwater pollution research, respectively.

Figure 1.

Review articles on AI applications in NPSP [10,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33].

Despite the growing number of AI-related environmental reviews, several critical aspects of NPSP remain underexplored. There is a need to synthesize and clarify the following:

- The AI methods applied in NPSP and the metrics used to evaluate their performance.

- The technical trade-offs associated with current AI methods, including data availability and quality, computational complexity, and model interpretability.

- The integration of AI with supporting technologies (remote sensing, IoT, and GIS) enhances the scalability, efficiency, and precision of NPSP monitoring and control.

- The key knowledge gaps, unresolved challenges, and emerging opportunities that can inform future research, policy development, and real-world implementation of AI-based NPSP solutions.

Therefore, this study aims to address these gaps through a combination of bibliometric analysis and systematic review of AI applications in NPSP, guided by the following objectives:

- To provide a status update on the current structure and evolution of AI applications in NPSP research.

- To provide a function-based classification of AI models, mapping their inputs, outputs, and roles in solving specific NPSP challenges such as nutrient loading, runoff prediction, and source identification.

- To offer a comparative synthesis of commonly used AI techniques (e.g., ANN, SVM, and hybrid models), assessing their respective strengths and limitations in terms of data requirements, computational costs, scalability, and interpretability.

- To explore how AI can be enhanced through integration with remote sensing, IoT, GIS, and other enabling technologies, improving its applicability for real-time, large-scale NPSP management.

- To identify and categorize critical knowledge gaps, including (a) AI model development, optimization, and validation, (b) data limitations and monitoring challenges, (c) governance, policy, and social dimensions, and (d) system integration (IoT, remote sensing, GIS) and to propose targeted directions for future research, emphasizing adaptive governance, transparent model development, and interdisciplinary solutions.

Table 1 shows a list of abbreviations.

Table 1.

List of abbreviations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Framework Adoption

The methodology adopted in this study ensured a robust and structured approach, aligning with the esteemed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) standards. By using this methodology, key findings were systematically identified and extracted to contribute to a deeper comprehension of the interconnection between AI and NPSP.

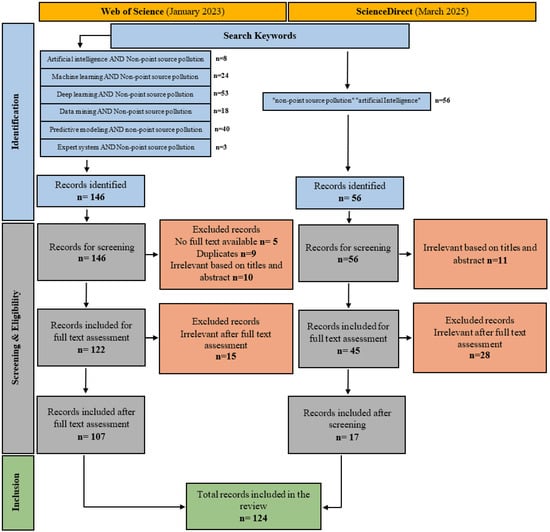

The PRISMA method was chosen due to its transparent and rigorous procedures that document the steps of the review process, making it easy for others to replicate, verify, and build upon [34]. The PRISMA checklist includes critical items such as details on the specific sources searched, the search strategies employed, eligibility criteria for including or excluding studies, and assessment of study quality based on internal and external validity. Most importantly, the PRISMA framework provides a flow diagram visually depicting the main phases of identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion of studies (Figure 2). This flow diagram facilitates obtaining a set of high-quality, relevant articles that can be relied upon to represent the current state of research on NPSP accurately.

Figure 2.

PRISMA diagram for article inclusion/exclusion in this systematic review.

2.2. Database Sourcing and Search Strategy

This section constitutes the identification phase of PRISMA. The studies were identified through a systematic search from the “Web of Science” and “ScienceDirect” databases, chosen for their multidisciplinary coverage of peer-reviewed academic sources. An iterative process was used to develop a comprehensive search string that captured all relevant studies that addressed the topic in the title, abstract, or keywords. The first search string, conducted in January 2023 on the Web of Science database, consisted of the following combinations connected by the Boolean operator “AND”: Artificial intelligence AND Nonpoint source pollution, Machine learning AND Nonpoint source pollution, Data mining AND Nonpoint source pollution, Expert systems AND Nonpoint source pollution, Predictive modeling AND nonpoint source pollution, and Deep learning AND Nonpoint source pollution. Each combination yielded the following number of results: eight studies for “Artificial intelligence AND Nonpoint source pollution”, 24 studies for “Machine learning AND Nonpoint source pollution”, 53 studies for “Data mining AND Nonpoint source pollution”, 18 studies for “Expert systems AND Nonpoint source pollution”, 40 studies for “Predictive modeling AND nonpoint source pollution”, and three studies for “Deep learning AND Nonpoint source pollution.” In total, 146 unique, English-language, peer-reviewed articles were identified from this search. A second search was conducted in March 2025 to enhance the quality of the study by incorporating more recent publications. This follow-up search, using the keywords “nonpoint source pollution” combined with “artificial intelligence” (using the quotation strategy), was performed on the ScienceDirect database and was limited to studies published in 2024 and 2025. To specifically evaluate whether variations in our search terms would yield significantly different article pools, we conducted a sensitivity analysis. More details are presented in Supplementary Table S2. A total of 56 studies were identified from this search, bringing the total number of studies to 202 (146 + 56).

2.3. Eligibility Criteria and Screening

This section corresponds to the second and third phases (Eligibility and Screening) of the PRISMA framework. Each retrieved article was carefully reviewed to determine its suitability for inclusion in the systematic review. Eligibility was assessed based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined in Table 2, with a focus on the article’s relevance, methodological rigor, and alignment with the study’s objectives. In addition to meeting the predefined general criteria such as language, document type, and keyword relevance, each article was evaluated for scientific rigor and completeness. Quality assessment was based on the clarity of research objectives, transparency in methodology (e.g., model design, training, and validation), data availability, and peer-review status. Particular attention was given to whether the study presented original methods, empirically tested models or comparative evaluations of AI techniques. Studies lacking robust methodology, reproducible outcomes, or adequate explanation of AI application were excluded. This ensured that only high-quality, relevant, and empirically sound studies were included in the final synthesis.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The screening phase, conducted according to the eligibility criteria, consisted of two distinct stages. The initial stage involved thoroughly evaluating study titles, abstracts, and keywords, focusing on including the key search terms “artificial intelligence” and “nonpoint source pollution.” This rigorous initial screening excluded 21 (10 + 11) irrelevant studies, yielding 181 (136 + 45) potentially relevant articles for further review. However, it was identified that there were nine duplicates among them, and an additional five articles were inaccessible in full text. Consequently, 167 (122 + 45) distinct records remained for full-text assessment. The second stage comprised a more in-depth evaluation of full-text articles based on the eligibility criteria previously discussed. The second stage led to the exclusion of 43 (15 + 28) additional articles.

2.4. Study Selection Process

This section addresses the inclusion phase of PRISMA. It encompasses 124 (107 + 17) studies that successfully passed the identification, screening, and eligibility phases. These studies meticulously satisfied the predefined eligibility criteria and were comprehensively analyzed and incorporated into the synthesis. Conversely, 39 articles were excluded at various stages for different reasons. The specific reasons for exclusion at each phase were carefully documented to ensure transparency in the systematic review process. Specifically, nine articles were removed as duplicates found during the database searches. Another ten studies were screened out based on their titles, abstracts, and keywords not relating to the designated scope of applying AI techniques to monitor and address NPSP. After a full-text review, 15 articles lacked sufficient data or were unrelated to the core subject matter. Lastly, five studies had to be excluded because the full texts were unavailable even after exhaustive attempts to retrieve them from various sources, preventing an adequate evaluation.

2.5. Data Extraction and Preparation

Data for this review were collected through both automated and manual extraction methods. Bibliometrix/Biblioshiny (www.bibliometrix.org (accessed on 17 June 2025)), an online data analysis framework based on the shiny (install.packages(“bibliometrix”), library(bibliometrix) package in R software (Version 4.2.3.), was utilized to extract bibliometric data (authors, date and number of publications, citations, journals, and country affiliation) [35]. Additionally, VosViewer (www.vosviewer.com (accessed on 17 June 2025)), which features a text mining function [36] was used for keyword extraction. Keywords with a frequency of five or more were selected to support co-occurrence and thematic analyses. These high-frequency terms were treated as indicators of each article’s core content and research focus.

To complement the automated extraction, a structured data extraction spreadsheet was also developed to manually gather content-specific information from each study systematically. This included detailed entries on the type and classification of AI models used, supporting technologies, their specific applications to NPSP, the pros and cons of the models, associated technical or implementation challenges, and knowledge gaps identified by the authors. Each article was reviewed manually to ensure consistency, accuracy, and comparability across all data entries.

2.6. Data Analysis

The extracted data were analyzed through a combination of Bibliometrix/Biblioshiny and VosViewer. Bibliometrix and Biblioshiny, integrated with R software (Version 4.2.3.)’s shiny package, facilitated the exploration of diverse facets of this study [35]. This included annual publication trends, collaborative patterns among authors from different nations, scientific productivity of countries and authors, and themes associated with NPSP. The tool also has a text mining feature for keyword extraction, facilitating keyword analysis, and determining the number of citations. The keywords present in a study serve as a concise summary and refinement of its core content. To gain insights into the research trends and directions in AI applications in NPSP, keywords with a frequency of five or greater are drawn as a word cloud.

A publication trend analysis was conducted using a simple linear regression equation (Equation (1)) and the coefficient of determination (R2) (Equation (2)) to quantify and model the temporal trend in the number of AI-based NPSP publications.

where y is the number of publications, x is the year, a is the slope, b is the y-intercept, n is the number of observations, is the average number of publications, is the predicted number of publications for a given year, and Yi is the actual number of publications for that year.

Multiple correspondence analysis was also conducted using the R software (Version 4.2.3.)’s shiny package to illustrate the interconnections among the keywords, condensing complex data with multiple variables into a two-dimensional representation. This approach enables the exploration of relationships between keywords, identifying co-occurrence patterns, and revealing underlying themes within the bibliometric data [35]. The distance between the points on the created graph reflects the similarity between the keywords, and the ones moving toward the central point indicate that they have received significant attention in recent years [35,37].

A classification tree of the AI models used in NPSP studies was created using the RStudio software (Version 2024.12.1+563) “collapsibletree” package in RStudio, based on the learning methods and algorithm purposes defined by Mukhamediev et al. [38]. Spatial distributions of the studies across different regions were mapped using Bibliometrix to look for geographic patterns.

2.7. Summarizing and Reporting of the Results

The findings of this study were illustrated using a range of visualization techniques. Bar graphs effectively visualized the chronological evolution of publication output and the journals in which they were published. Network maps depicted interactions among authors and co-authors, while geographical maps provided insight into international collaboration patterns. A thematic map and word cloud were employed to dissect and illustrate the core themes of AI-focused NPSP research. A collapsible tree diagram was created using the RStudio software (Version 2024.12.1+563) to elucidate AI classifications, and customized figures were employed to explain the PRISMA framework and application of AI in NPSP and the challenges that emerged from the selected studies. This array of visualization techniques helps communicate the study’s findings in a readily understandable manner.

3. Results

3.1. Bibliometric Analysis

3.1.1. Trends in Scientific Studies on AI in NPSP

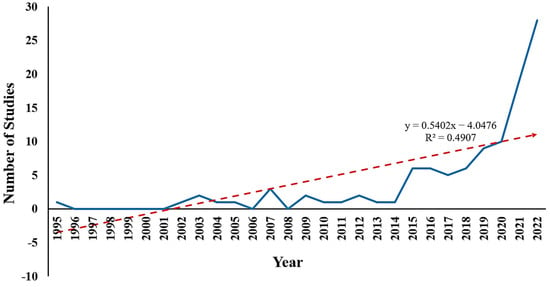

The application of AI techniques to address NPSP has progressed over the past few decades, as NPSP continues to be a widespread environmental challenge [39]. Peer-reviewed studies published between 1995 and 2022 were used in the trend analysis. As illustrated in Figure 3, the amount of AI-based research in NPSP has grown substantially since 1995. The fitted line (y = 0.5402x − 4.0476; R2 = 0.4907) demonstrates a moderate growth in publication rate over time. Notably, over 50% of the studies were published during the six years (2017–2022). The surge in publications indicates a growing interest in utilizing AI to address environmental issues associated with NPSP, particularly as more robust data sources and computational methods become available.

Figure 3.

Annual distribution of publications.

3.1.2. Country Productivity and Collaboration

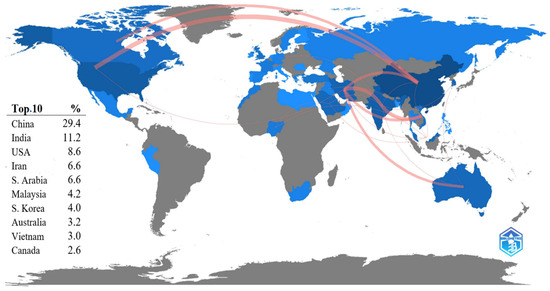

Figure 4 illustrates both the global distribution of publications and the collaborative efforts among countries in the field of AI applications for NPSP. China leads significantly with 29.4% of the total publications, followed by India (11.2%) and the United States (8.6%), reflecting their dominant research presence. However, the findings also highlight a notable limited contribution from regions such as South America and Africa, revealing a critical gap in global research efforts that could affect these regions’ ability to tackle local pollution challenges effectively. Beyond individual country productivity, Figure 4 reveals important patterns of international collaboration. The thick connector line between China and the United States, representing seven joint publications, indicates a strong bilateral synergy in applying AI to NPSP problems. Similarly, Iran’s collaborative links with Vietnam (five), China (three), and Australia (three) demonstrate an active role in global research networks. These partnerships highlight the importance of scientific cooperation in advancing technological solutions to diffuse pollution. Such collaborations foster knowledge exchange, enhance model development, and build capacity across regions with varying levels of expertise. Encouraging broader international partnerships, especially involving underrepresented continents (e.g., South America and Africa), is essential to ensure a more inclusive and globally responsive approach to AI-based NPSP management.

Figure 4.

Map showing the productivity and collaboration among countries (lines’ size indicating the collaboration frequency (thickest line: 7; thinnest line: 1), color variation indicating percentage of documents produced in the total selected documents in this study (darkest blue: 29.4%, lightest blue).

3.1.3. Author, Citation, and Source Analysis

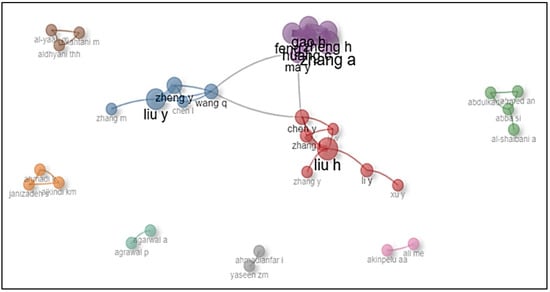

This authorship analysis examines the contributions of several authors to the literature, particularly AI-focused NPSP research. Figure 5 highlights the most prolific authors within the selected research articles, with Liu H. leading in publication volume (4 publications), followed by Liu Y. and Zhang A. tied in second place (3 publications). Although those authors have collaborated on multiple research papers, they primarily served as co-authors because of their cooperation, close contact, and mutual interest in the specific topic. Figure 5 also depicts numerous clusters, each representing a group of researchers focusing on a particular application of AI in NPSP. However, only three of the nine clusters reveal significant research collaboration. The most extensive collaboration clusters are centered around Liu H. and Zhang A., who collaborated with six other authors. The first cluster, led by Liu H., focuses on studies about water quality monitoring using satellite and machine learning [20], mitigation of fertilizer-based pollution [40], characteristics of NPSP research [41], performance and trends in NPSP modeling research [42] air pollution [43], and nonpoint pollutant sources management [19]. The second cluster, led by Liu Y., focuses on studies related to pollution in drinking water source areas [44], river pollution under the rainfall-runoff impacts [45], prediction of urban water quality [46], and heavy metal contamination concentration in surface waters [47]. The third cluster, led by Zhang A., predominantly involves studies on data-driven machine learning in environmental pollution [48,49,50]. These clusters highlight these authors’ focused research efforts and collaborations in AI applications in NPSP.

Figure 5.

Network map showing authorship analysis. The size of the nodes reflects the frequency. The more the item occurs, the larger the node and font size. The colors indicate the cluster to which a node has been assigned.

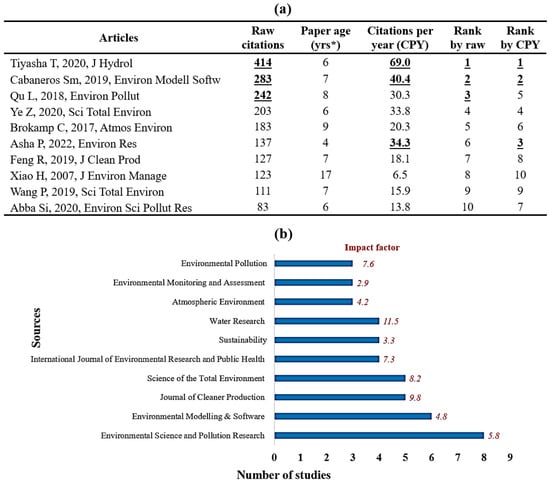

The paper titled “A comprehensive analysis of AI models for river water quality modeling: 2000–2020” by Tiyasha et al. [26] stands out as the most frequently cited article among the chosen papers for this review, with 414 citations (Figure 6a). The significant citations reflect this study’s influence on the NPSP field. The paper, titled “A Review of ANN Models for Ambient Air Pollution Prediction”, authored by Cabaneros et al. [23], holds the second position with a total of 283 citations. A comparison of these papers across both raw citation counts and citations per year (CPY) reveals consistent dominance by Tiyasha et al. [26], which leads with 414 raw citations and an impressive 69.0 CPY. This robust performance across both metrics underscores the paper’s foundational significance and enduring relevance in the field. Cabaneros et al. [23] similarly maintain their strong position, accumulating 283 raw citations and averaging 40.4 CPY, solidifying their sustained impact since publication, although at a slightly slower rate than the top-ranked paper. However, this alignment between raw citations and CPY is not consistent across all top-performing articles, emphasizing the importance of considering publication age in assessing influence. For example, Qu et al. [47], while ranking third in raw citations with 242, occupy the fifth position when considering citations per year (30.3 CPY). This suggests a steady but perhaps less rapid accumulation of citations over its 8-year lifespan. Conversely, Asha 2022 [51], despite being sixth in raw citations with 137, demonstrates a more rapid recent impact by moving up to third place in citations per year (34.3 CPY). This rapid ascent in CPY for a relatively newer paper (published in 2022) highlights its immediate relevance and significant contemporary influence, indicating that it is quickly becoming a key reference in the field despite having less time to accumulate raw citations. This distinction between cumulative impact (raw citations) and current scholarly attention (citations per year) provides a more nuanced understanding of a paper’s evolving influence within the research landscape.

Figure 6.

Most cited papers (a) and top 10 journals (b). Bold and underlined values indicate the top three articles in each category. *: Paper age in years. Numbers in red indicate journal impact factors [23,26,28,47,51,52,53,54,55,56].

This study also investigates the sources of the publications addressing AI in NPSP (Figure 6b). A catalog of environmental science and water management journals addressing issues related to NPSP was explored. Figure 6 highlights the top 10 journals that have significantly contributed to the field by publishing influential articles over the past decade. Environmental Science and Pollution Research (8 publications; Impact Factor (IF): 5.8), based in Germany, emerged as the most prominent journal in this area in terms of publication volume. Among the journals with the highest impact factors, Water Research (5 publications; IF: 11.5) from the United Kingdom, along with the Journal of Cleaner Production (6 publications; IF: 9.8) and Science of the Total Environment (6 publications; IF: 8.2) from the Netherlands, stand out for their significant contributions. Other journals also played a role, including Atmospheric Environment (UK), Environmental Modelling and Software (Netherlands), Environmental Monitoring and Assessment (Netherlands), The International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health (Switzerland), and Sustainability (Switzerland). While some journals, like Environmental Science and Pollution Research, lead in publication volume, others, such as Water Research, despite a lower number of publications, demonstrate higher impact factors, indicating a focus on highly cited research. Journals with the highest impact factors, such as Water Research, Journal of Cleaner Production, and Science of the Total Environment, indicate a trend toward publication in more rigorous, multidisciplinary outlets. These journals provide invaluable insights and research findings that enhance our understanding of today’s complex environmental challenges.

3.1.4. Co-Occurrence and Multiple Correspondence Analysis

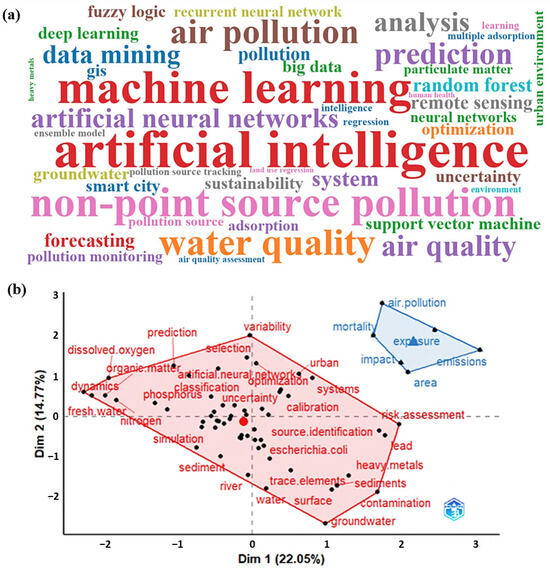

The co-occurrence analysis of the keywords indicates that “artificial intelligence (25 occurrences)”, “machine learning (16 occurrences)”, and “nonpoint source pollution (11 occurrences)” are the most commonly occurring keywords (Figure 7a). This finding suggests a significant focus on using AI and ML techniques to address NPSP issues. For instance, AI models such as random forest and support vector machines have been used to assess NPSP by estimating the input and export of nutrients in water bodies [44], and SOM and ANN for assessing water quality [57]. Five distinct patterns emerged from the co-occurrence analysis. The first revolves around the general application of ML for evaluating groundwater quality [58,59,60,61,62]. The second encompasses the use of SVM [63], RF [64], FL [62], and ANN [65] for assessing NPSP-related problems. The third emphasizes the connection between air pollution and water quality concerns [43,49,66]. The fourth investigates the overall use of AI for assessing NPSP from a sustainability environmental perspective [67]. The last one provides a comprehensive overview of various types of pollution [68]. In addition, a multiple correspondence analysis was conducted, which led to the creation of Figure 7b. The results showed two main clusters. Cluster 1 (in red) comprises 32 keywords related to pollution assessment, including risk assessment, prediction, variability, water type (surface, groundwater), and pollution type (chemical with N, P, dissolved oxygen, organic matter, and microbiological with E. coli). Cluster 2 (in blue) consists of six keywords (air pollution, mortality, impact, area, emissions, and exposure) focused on the pathway and impacts of pollution.

Figure 7.

(a) Wordcloud of keywords and (b) conceptual structure map.

3.2. Synthesis of AI Applications in NPSP Studies

3.2.1. NPSP Characterization

NPSP presents a complex environmental challenge and studies have focused on diffuse origins (Supplementary Table S1), across land-use activities, such as agriculture, urban runoff, atmospheric deposition, and industrial discharges [41,69]. Characterizing NPSP requires understanding its impact across a broad scope of pollution types and environmental settings. This includes water pollution, focus on river systems for detection and control [26,29,50], strategies for pollutant removal [24], and analysis of contaminants in groundwater and water supplies [31]. Air pollution is another significant area, emphasizing outdoor air pollution forecasting and broader AI research trends in air quality management [23,30,32,33]. Agricultural pollution is also a major contributor to NPSP, requiring dedicated study [25]. Expanding beyond single-media assessments, NPSP is increasingly viewed from a multi-environmental perspective, encompassing pollution across water, air, and soil, especially in vulnerable ecosystems like mangrove forests and in the general context of environmental pollution management [27,28].

The pollutants associated with NPSP are wide-ranging, and their occurrence exhibits significant spatiotemporal variability. Agricultural runoff is a major transport pathway of nutrients and sediment, while urban runoff contributes to a cocktail of chemicals and solids [70,71,72]. Atmospheric deposition, linking air pollution from industrial and vehicular emissions to water and soil contamination [43,51,71,73], is mostly associated with fine particulate matter and gaseous pollutants (e.g., NO2, CO2). Considering these complex dynamic processes associated with NPSP across different spatial scales, advanced monitoring and modeling techniques, such as AI, are needed to simulate pollutant behavior and quantify source contributions. See Table 3 for more details.

Table 3.

NPSP characterization based on factors such as pollution sources, drivers, pollutants, transport pathways, and impacts.

3.2.2. Integration of Emerging AI Technologies

AI applications in NPSP management have been enhanced through the synergistic integration of complementary technologies that support data acquisition and real-time monitoring. For instance, low-cost IoT stations (e.g., qHAWAX) [88] and mobile sensor networks [89] are deployed for real-time measurement of pollutant concentrations (e.g., NO2, PM), providing crucial localized data. Similarly, AI-enhanced toxicology platforms (e.g., ETAPM-AIT) [51] and smart agriculture systems with intelligent nutrient sensors [25,90] have integrated IoT networks to improve pollution monitoring and predictive precision. High-resolution spatiotemporal data for assessing urban water quality, agricultural runoff, and composting activities is obtained through unmanned aerial vehicles (e.g., drones) equipped with multispectral cameras [91,92], while satellite imaging platforms like Landsat and Sentinel-2 are widely applied to track broad-scale land-use change and pollutant dispersion [93,94,95]. GIS further enhances these capabilities by integrating diverse data streams to map pollutant transport pathways and identify pollution hotspots [44,54]. Together, these integrated tools provide AI models with the rich and diverse data necessary to detect pollution patterns, forecast pollutant loads, and inform timely, targeted interventions across complex NPSP landscapes.

Beyond data acquisition, the synergistic integration of these enabling tools with advanced AI techniques significantly amplifies model functionality, leading to substantial improvements in prediction accuracy and decision-support capacity. The robust and diverse data streams generated by sensors, UAVs, and remote platforms (e.g., satellites) provide ML models like XGBoost [91] and optimized extreme learning machines (ELM such as mixed kernel ELM with particle swarm optimization (PSO-MK-ELM) [95] with enriched input features, ultimately enhancing their generalizability and performance stability. Furthermore, DL architectures (e.g., ANNs), excel at modeling complex, long-term environmental trends by effectively leveraging the dense, high-frequency datasets originating from IoT and satellite networks [93,94]. To address the inherent consequences of NPSP (e.g., eutrophication), explainable tools like SHapley Additive exPlanation (SHAP) [83] offer crucial transparency by interpreting AI model inputs and outputs, fostering greater stakeholder trust and facilitating policy adoption. The integration of big data platforms like Hadoop MapReduce [89] translates AI-based air quality analyses into graphical formats (e.g., pollution maps) for practitioners and policymakers. Moreover, the coupling of AI with advanced analytical tools such as spectroscopy and fluorescence probes [96,97] allows for precise pollutant characterization, adding a critical layer of detail for pollutant source identification and real-time management strategies. These combinations equip AI frameworks with enhanced analytical depth, improved real-time responsiveness, and greater operational scalability, essential attributes for effectively tackling the multifaceted challenges of NPSP control.

3.3. AI Modeling Approaches in NPSP Management

3.3.1. Overview of AI Model Applications

AI models are extensively applied in NPSP assessment, offering enhanced predictive accuracy, automation, and adaptability across varied spatial contexts such as rivers [74,84], aquifers [76], marine ecosystems [98], and landfills [67]. Their ability of AI to model complex nonlinear relationships, process high-dimensional datasets, and capture spatiotemporal variability makes them particularly suited for addressing the diffuse and dynamic nature of NPSP [53]. AI techniques have been employed for major NPSP functional tasks such as water quality prediction, groundwater vulnerability mapping, and pollutant-specific modeling. Table 4 provides details about the AI models, inputs, outputs, and performance metrics used to evaluate the performance of the AI models.

Water Quality Prediction and Monitoring: AI models such as SVM, GEP, and MLP have been widely applied in river systems to estimate key water quality parameters, including electrical conductivity, total dissolved solids, and sodium adsorption ratio [74]. ANNs have facilitated virtual water quality monitoring by modeling a broad spectrum of chemical indicators, such as total suspended solids, chemical oxygen demand, and nutrients like sulfate, phosphate, bicarbonate, and nitrate [77]. For water quality index estimation, models like BPNN, ANFIS, and SVM used simple yet meaningful inputs such as dissolved oxygen, ammonia, and pH [53]. Similar approaches have also been successfully applied to assess NPSP in lakes, where DT, SVM, and ANN models predict WQI using variables like temperature, pH, turbidity, and coliform counts [99]. These applications demonstrate that AI models can effectively detect subtle pollution patterns and forecast water quality, thereby supporting real-time, data-driven decisions and the proactive management of NPSP for sustainable water resource protection.

Groundwater Vulnerability Mapping: In groundwater systems, AI is increasingly used for pollution vulnerability mapping and risk classification, providing critical insights for water resource management. BRT and KNN have been applied to nitrate vulnerability assessments by integrating hydrogeological, land-use, and topographic predictors, allowing for more precise identification of areas at risk of contamination [21]. CNN further enhances spatial modeling by capturing the heterogeneity of aquifer pollution, making it particularly effective in regions with complex spatial variability [76]. AI-based frameworks that combine PSO, SVM, and NBC have also been used for groundwater water quality index prediction using physicochemical profiles, including electrical conductivity, pH, alkalinity, sulfate, and nitrate [60]. Additionally, FL models provide rule-based classification for groundwater quality monitoring, offering enhanced interpretability that is valuable for regulatory and policy applications [62]. Building upon these diverse applications, AI enhances groundwater vulnerability mapping by automating the integration of diverse datasets to simulate scenarios and anticipate the impacts of land use, agriculture, and climate variability on groundwater quality, leading to more informed decision-making and proactive management strategies.

Pollutant-Specific Modeling: Assessing the levels of specific pollutants, such as trace metals and nutrients, is also a crucial component in addressing NPSP. In the context of highway runoff, the MT–GA hybrid model, combining Model Trees and a Genetic Algorithm, was used to predict concentrations of chromium, lead, zinc, total organic carbon, and total suspended solids [72]. Models such as WER-GBO, LSSVM, and ANFIS have demonstrated high accuracy in monthly sodium concentration prediction. These models are effective by capturing complex, non-linear relationships between input parameters, such as lag-time of discharge and sodium, and pollutant levels [100]. GBT has also been successfully used to predict arsenic concentrations using dissolved oxygen, pH, and salinity data; its ensemble nature allows it to handle complex interactions among these variables, leading to robust predictions [61]. RF, BRT, and LR have been utilized for arsenic hazard mapping in groundwater, integrating diverse spatial data to delineate areas prone to high arsenic levels [101]. Groundwater nitrate concentration mapping has been addressed using SVM, RF, and Bayesian-ANN, which integrate terrain, hydrology, and land-use data for improved spatial accuracy. These models can help identify complex spatial patterns and relationships between land surface characteristics and groundwater nitrate levels [64]. BGLM and BART have further contributed to nitrate modeling by offering probabilistic outputs and greater flexibility in handling variable-rich datasets. The Bayesian framework provides not just point predictions but also uncertainty estimates, which are crucial for risk assessment and decision-making [102]. Overall, the AI models are particularly advantageous for pollutant-specific tasks due to their ability to handle nonlinear interactions and optimize performance, even with limited or imbalanced datasets [26,32].

AI Applications in Other NPSP Contexts: Beyond traditional aquatic systems, AI has also been applied to NPSP sources such as landfill leachate, urban runoff, and marine sediments. Models like FL, RBFANN, and MLPANN have accurately predicted landfill leachate characteristics based on physicochemical parameters (e.g., hardness, turbidity, oxygen demand) and heavy metal concentrations (e.g., lead, chromium, cadmium) [67]. Genetic Algorithm–Ridge Regression models have also been used to assess aquifer vulnerability near landfill sites [58]. These models are capable of handling the complex, multivariate nature of leachate composition, which is crucial for treatment and monitoring. Additionally, they demonstrate AI’s ability to simulate complex subsurface processes and evaluate the potential for leachate migration to contaminate groundwater [58,67]. In coastal and marine settings, SVR and GA have been employed to predict polyaromatic hydrocarbon concentrations for pollution mapping, demonstrating the ability of these models to handle the complex fate and transport of pollutants in dynamic marine environments [98]. Similarly, the health and pollutant levels in mangrove ecosystems affected by multi-source pollution have been assessed using a range of AI models, including ANN, BPNN, GRNN, RBFNN, XGBoost, and FL. These models enable the integration of data from diverse pollution origins, facilitating a comprehensive evaluation of their cumulative impact on sensitive coastal ecosystems [27].

AI Model Performance: The effectiveness of AI models across diverse NPSP settings (e.g., rivers, lakes, highways, aquifers, mangroves, marine ecosystems) is consistently demonstrated by various performance metrics reported in the literature. Some of the commonly used metrics include R2, RMSE, MAPE, NSE, and AUC, which serve to validate model accuracy and reliability. For instance, studies using models like SVM, GEP, and MLP for river water quality estimation reported a high R2 value (0.88) and a low RMSE (19.71), signaling good model fit and minimal prediction error [74]. Similarly, hybrid and ensemble models have demonstrated effectiveness in predicting complex outputs. An MT–GA hybrid model achieved a high R2 (0.87) when predicting runoff metal concentrations [72]. In another study, WER-GBO and LSSVM models predicted monthly sodium loads with a low RMSE (0.639) [100]. Groundwater vulnerability assessments have also shown strong spatial predictive power. For example, CNN applications reported high AUC (0.95), indicating a significant signal and excellent predictive capability [76]. BRT applications likewise demonstrated classification reliability with a strong AUC value (0.79) [21]. Additionally, ANN and ANFIS models used in virtual monitoring and WQI prediction demonstrated strong modeling capabilities, capturing non-linear trends while maintaining acceptable MAPE (<10%) and NSE value (0.68) [53,77]. These consistent performance trends across diverse scenarios underscore AI’s capacity to deliver reliable, scalable, and context-sensitive predictions in support of proactive NPSP management.

Table 4.

Summary of AI Applications in NPSP.

Table 4.

Summary of AI Applications in NPSP.

| No | Purpose | Environmental Context | Applied AI Models | Input (Predictor) | Output (Predictand) | Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Water quality evaluation | River | SVM, GEP, MLP | EC, TDS, SAR | EC, TDS, SAR | RMSE, MAE, R2, DDR | [74] |

| 2 | Prediction of highway runoff quality | Highway | MT–GA | Cr, Pb, Zn, TOC and TSS annual average daily, antecedent dry period, rainfall, maximum 5-min rain intensity | Cr, Pb, Zn, TOC and TSS | R2 | [72] |

| 3 | Aquifer vulnerability mapping | Aquifer | CNN | Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Cl−, SO42−, HCO3− and HCO32− | Vulnerability maps: IVI, SVI, and TVI | AUC | [76] |

| 4 | Nitrate pollution vulnerability mapping | Groundwater | BRT and KNN | NO3−, Depth to groundwater, Hydraulic conductivity, Aquifer thickness, Net recharge, Distance from river, Drainage density, Land use, Well density, soil texture, permeability, and soil organic matter content, Surface slope. | Groundwater vulnerability maps, | Sensitivity, Specificity, Area under ROC curve, and Kappa | [21] |

| 5 | Virtual water quality monitoring | River | ANN | T, pH, TSS, hardness, alkalinity, EC, BOD, COD, DO, CO2, Ca, Mg, P, Cl−, SO42−, PO43 HCO3− and NO3− | T, pH, TSS, hardness, alkalinity, EC, BOD, COD, DO, CO2, Ca, Mg, P, Cr, Cl−, SO42−, PO43 HCO3− and NO3− | MAE, RMSE, R2, MAPE, NSE | [77] |

| 6 | Water quality prediction | River | BPNN, ANFIS, SVR), MLR | DO, BOD, T, pH, NH3, and WQI | WQI | DC, RMSE, and R | [53] |

| 7 | Water quality prediction | Groundwater | PSO, NBC, SVM | EC, pH, TDSs, TH, alkalinity, bicarbonate, Cl, SO4, NO3, fluoride, Ca, Mg, Na, K, Fe. | WQI | Confusion matrix | [60] |

| 8 | Water sodium concentration prediction | River | WER-GBO, LSSVM, ANFIS | Discharge and Na | Monthly sodium prediction | R, RMSE, KGE, MAE, MAPE, IA | [100] |

| 9 | Arsenic concentration prediction | River | GBT | As, DO, pH, T, salinity, DS | As concentration | R2 | [61] |

| 10 | Groundwater pollution vulnerability | Groundwater | GA-Ridge regression | Depth to water, net recharge, topography, and impact of vadose zone media | Depth to water, net recharge, topography, and impact of vadose zone media | MSE | [58] |

| 11 | Environmental pollution mapping | Near-shore marine sediments | SVR and GA | Total petroleum hydrocarbons descriptor | Total polyaromatic hydrocarbons | R, MSE, MAE, MAPD | [98] |

| 12 | Groundwater contamination modelling | Groundwater | BGLM, BRNN, BART, and BRR | Elevation, slope, plan curvature, profile curvature, annual rainfall, groundwater depth, distance from residential, distance from the river, Na, K, and topographic wetness index | Groundwater nitrate concentration | R2 | [102] |

| 13 | Water quality prediction | Lake | SVM, DT, ANN | T°, pH, turbidity, and coliforms | WQI | MSE, RMSE, and RSE | [99] |

| 14 | Groundwater quality monitoring | Groundwater | FL | pH, T°, turbidity COD, BOD, PO4, NO2, NO3, NH4, DO, EC, and FC | WQI | [62] | |

| 15 | Landfill leachate penetration management | Landfills | FL, RBFANN, and MLPANN | Fe, Pb, Cr, Cd, Molybdenum, N, Al, Na, COD, TDS, EC, Cl, hardness, turbidity | Predicted leachate | R2 RMSE: | [67] |

| 16 | Spatial groundwater nitrate concentration estimation | Groundwater | SVM, RF, Baysia-ANN | Elevation, slope, plan curvature, profile curvature, rainfall, piezometric depth, distance from the river, distance from residential, Na, K, and topographic wetness index | Groundwater nitrate concentration | R2, RMSE | [64] |

| 17 | Groundwater arsenic hazard Modelling | Groundwater | RF, BRT, LR | Elevation, slope, aquifer connectivity, distance from the Ganges and other major rivers, minor rivers, streams and estuaries, groundwater depth and fluctuation, potential groundwater recharge, groundwater-fed irrigated area, land cover, and population. | As concentration | Sensitivity Specificity Accuracy | [101] |

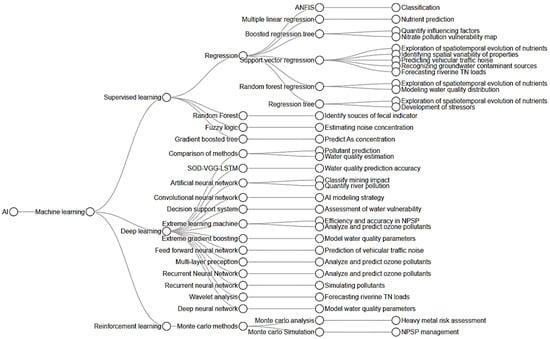

3.3.2. Classification of AI Techniques

Understanding AI hierarchical classification is essential when looking at AI models in NPSP. In Figure 8 and Table 1, the AI models applied in addressing NPSP issues were classified based on the AI classes generated by Mukhamediev et al. [38]. In NPSP studies, three subclasses of ML were identified: supervised learning (SL), deep learning (DL), and reinforcement learning (RL). SL includes several AI models, such as SVM, applied to estimate the input and export of nutrients [44]. RF, a decision tree-based ensemble learning method, has demonstrated its efficacy in evaluating spatial water quality distribution and identifying features impacting the water quality [103]. Boosted regression trees were used to quantify the effects of nonpoint source nitrate pollution in groundwater [21]. ANNs have been widely employed to model and predict water quality parameters affected by NPSP [57]. FL can form the basis for implementing control strategies to enable decision-making or supervisory control for pollution minimization and mitigation processes [104]. FL was also used to control the aerobic stage of wastewater treatment processes [28], while ANFIS assisted in predicting the water quality index [65].

Figure 8.

Subsections of AI classes linked to NPSP models.

The findings suggest that DL methods are the most prominent subset of AI in the NPSP method, focusing on precision and accuracy for predictions [105]. CNN was used to map the total aquifer pollution vulnerability [76]. FFNN models and predicts water quality [65]. RNN was used to analyze and accurately forecast pollutants [52]. LSTM was applied for water quality prediction [55], while DNN showed good performance in pollution forecasting [32].

The results indicate that the RL model used to assess NPSP employed Monte Carlo (MC) simulation, which is well-suited for complex simulations and is mainly applied in combination with other AI models. MC simulation techniques were used to quantify uncertainty while applying ANN for pollution forecasting [106]. A water quality risk assessment was conducted using MC simulation and the artificial neural network method [107]. Virtual water quality monitoring was performed using Monte Carlo-optimized artificial neural networks [77]. Combining ANN, RF, and MC simulations developed a machine learning-based algorithm for water supply pollution source identification [108]. These innovative approaches enable real-time monitoring and adaptive management [66], allowing for quick responses to changing environmental conditions [26].

3.3.3. Advantages and Limitations of AI Models

AI models have been widely adopted to address the complex, non-linear, and dynamic nature of NPSP due to their inherent flexibility, proficiency in analyzing large and heterogeneous environmental datasets, ability to uncover pollution trends, and capacity to generate accurate pollution predictions at regional, national, and global scales [9,109]. Models such as ANN, SVM, and RF have demonstrated strong performance in predicting water quality indices, nutrient loads, and pollutant concentrations across diverse systems, including rivers, lakes, groundwater, and urban runoff [24,53,99]. ANNs are particularly tolerant of incomplete datasets and effective in modeling pollutant transport and water quality, while RF models are known for their robustness against overfitting and ability to handle noisy NPSP data [91]. LSTM and CNN are especially suited for capturing temporal pollution dynamics and spatial heterogeneity from remote sensing data, respectively [78,83]. ANFIS offers relative interpretability advantages and is particularly useful in uncertainty-prone scenarios or for early warning systems, although they are generally less effective for highly dynamic NPSP processes unless integrated with other modeling techniques [67,110]. Similarly, ensemble learning methods (e.g., WER-GBO, LSSVM, PSO-SVM, GA-ANN) can significantly boost pollution prediction accuracy and stability by combining the strengths of multiple models, though they often introduce added complexity and higher computational overhead [29,83]. These high capabilities and sophisticated functions make AI models very useful for NPSP assessment.

However, despite their advantages, AI models also present several limitations (Table 5). A primary concern is the “black-box” nature of deep learning models such as ANN, CNN, and LSTM, which limits interpretability and transparency [10,32]. The lack of transparency into how predictions (e.g., pollutant concentrations, transport pathways) are generated may undermine trust and confidence in the model results. This can hinder their acceptance and effective use in decision-making and regulatory contexts such as setting water quality standards, guiding pollution control interventions, and supporting environmental impact assessments [56,76]. Furthermore, many AI models (e.g., ANN, LSTM, CNN) require large volumes of high-quality, representative training data, which are often unavailable or imbalanced in real-world environmental monitoring settings (e.g., surface water bodies, catchments/watersheds, agricultural fields, urban areas) [51]. These models may also sometimes struggle to generalize beyond the specific conditions of the training dataset, reducing their reliability when applied to different locations, time periods, and aforementioned environmental contexts [51,110]. Overfitting remains a risk, particularly when data is noisy or unbalanced, and many advanced models (e.g., GBM, RT, CART) also impose high computational demands [85,111]. Additionally, training instability on small datasets and the need for expert knowledge for hyperparameter optimization limit the accessibility and scalability of these models [112,113]. Ultimately, while AI models offer powerful tools for improving the accuracy and depth of NPSP analysis, their successful deployment depends on balancing predictive capabilities with transparency, data requirements, and usability within real-world decision-making frameworks.

Table 5.

Pros and cons of AI models applied in NPSP.

3.4. Knowledge Gaps and Future Research Directions

Despite recent advancements in using AI for nonpoint source pollution (NPSP) assessment, several key research gaps still require attention. These fall into four main areas: (a) AI Model Development, Optimization, and Validation; (b) Data Limitations and Monitoring Challenges; (c) Governance, Policy, and Social Dimensions; and (d) System Integration.

When focusing on AI model development, many studies aimed at predicting water quality struggle with selecting the most appropriate inputs and do not fully utilize ensemble optimization techniques, which limits both AI model performance and generalizability [53]. Moreover, DL models like CNNs and LSTM networks are not yet fully utilized in AI-based environmental monitoring platforms such as OAI-AQPC and ETAPM-AIT. This limits their ability to effectively capture complex spatiotemporal pollution dynamics [51,89]. Data-related challenges represent another significant gap. Limited data availability, inconsistent spatial and temporal resolution, and insufficient standardization make it harder to effectively monitor pollution and properly validate models [20,83].

On the policy side, AI-based studies often fail to integrate important socio-political factors such as population dynamics, income inequality, stakeholder perspectives, and environmental justice considerations. Yet, including these is crucial for developing pollution management strategies that are truly inclusive and actionable [91,116]. Finally, insufficient research demonstrates the effective integration between AI systems and crucial enabling technologies such as IoT sensor networks, remote sensing platforms, and GIS. This lack of integration makes it challenging to achieve synchronized pollution data collection, scale up for real-time, basin-wide applications, and ensure different systems work together smoothly to support quick and informed decision-making in pollution management [27,29,73]. Future research on AI applications in NPSP should address these critical gaps to enhance model robustness, data availability, policy relevance, and cross-system integration. More details on these knowledge gaps and recommended research directions are summarized in Table 6 below.

Table 6.

Summary of knowledge gaps and direction for future studies.

4. Discussion

4.1. AI in NPSP: Current Status and Perspectives

The findings highlight the status of AI-based research for NPSP and provide valuable insights into the trends and collaborations in this field. The recent increase (Figure 3) in research indicates a growing recognition within the scientific community of AI’s potential for improving NPSP source identification [55,117,118], forecasting [50,53], and remediation efforts [47]. This highlights AI’s potential in developing practical solutions for NPSP and underscores the importance of integrating advanced technologies into environmental research [33,55,119]. As for country productivity, China is leading in AI applications for NPSP, accounting for a significant portion (29.4%) of the total publications (Figure 3). Collaborations between China and other countries, such as the United States, Canada, Iran, and Australia, are also prominent, indicating a scientific synergy among these nations in employing cutting-edge technologies to address NPSP challenges.

Nevertheless, given the significant impact of NPSP, it is reasonable to anticipate even greater collaboration, considering that NPSP is a worldwide issue. The findings suggested limited involvement from the South American continent. Balance in participation across continents could positively impact the productivity and economic growth of nations (e.g., South America) over time, especially as the use of AI in NPSP contexts becomes more critical for achieving sustainability goals [116]. With sufficient domestic research and development, South American countries may be better prepared to leverage cutting-edge AI techniques that can help monitor pollution sources, model impacts on ecosystems and human health, and design cost-effective remediation strategies. Increased engagement from scientists and decision-makers could help address this disparity and better position these nations for long-term environmental protection and economic prosperity [65,116].

Several authors, such as Liu H., Liu Y., and Zang A., have demonstrated their involvement in AI applications in NPSP research by conducting studies focusing on water quality monitoring [20] and prediction [120], pollution mitigation [40], and data-driven machine learning [49] (Figure 5). These authors remain the most productive authors for collaborating on several studies. Their contributions and collaborations demonstrate their significant involvement and expertise in AI-focused NPSP research, however, Tiyasha et al. [26] and Cabaneros et al. [23] were the two most cited studies according to our results (Figure 6). Together, these two papers significantly contribute to the field of NPSP by shedding light on the application of AI models in water quality modeling, the use of ANN models in air pollution prediction, and the risk analysis of heavy metal concentration in waters. Moreover, by offering valuable insights, methodologies, and recommendations for further research, these studies aim to advance the understanding, prediction, and mitigation of environmental pollution. However, the proximity in time between these top two ranked papers suggests that the rate of citations is not significantly influenced by the publication period but rather by the content of the papers. This suggests that the content of a publication is very important. This study’s co-occurrence and multiple correspondence analysis addressed the content aspect by shedding light on underlying themes and writing directions of the studies on AI applications for NPSP assessment (Figure 7). This can help identify gaps and under-explored areas, preventing duplication of efforts. It also provides ideas for future research by highlighting popular AI models and factors like impacted water bodies and pollution types. Seeing what types of pollution, like nutrients, organic matter, and microbes may shape how they prioritize certain issues

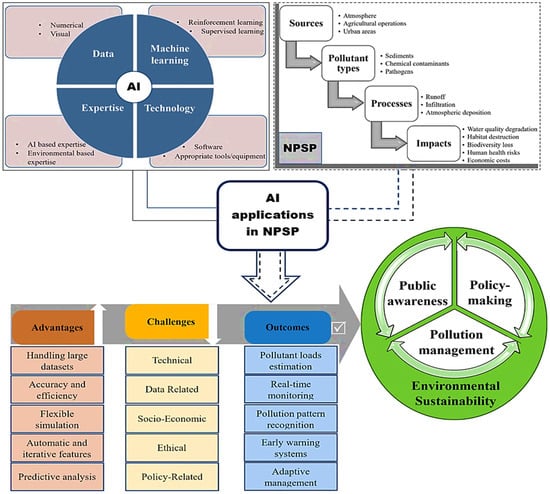

The recent advancement of AI has shown how it can be a crucial tool in addressing the complex challenges posed by NPSP [49]. To effectively utilize AI for NPSP mitigation, it is essential to have a comprehensive structure underlying the NPSP system that covers various aspects, as shown in Figure 9. AI-driven solutions rely on diverse data types, including visual and numerical data, to understand the complexities of NPSP sources and pollutant types [54,121]. Data is then processed and analyzed using supervised, reinforcement, and deep learning models to extract meaningful insights [38]. The successful application of AI in NPSP mitigation also depends on the technology available, specialized software, and appropriate tools [66,90]. Additionally, expertise in both environmental domains and AI is crucial for developing and deploying AI-based models tailored to address NPSP challenges comprehensively. The combination of AI’s analytical capabilities and environmental insights empowers decision-makers and stakeholders to proactively combat NPSP from various sources, such as the atmosphere [115], agricultural operations, and urban areas [122]. By focusing on sediment [98], chemical contaminants, and pathogens [10,118] as pollutant types, AI can identify sources [118], track their movement through processes like runoff and infiltration [67], and predict impacts on water quality, human health [61], and the economy [116].

Figure 9.

A broad perspective on AI applications in NPSP.

As NPSP is a widespread environmental issue with diverse ecological and societal consequences [49], integrating environmental and AI expertise can transform NPSP management strategies. AI-driven solutions offer a proactive approach to NPSP using historical [121] and real-time data [90] to identify potential hotspots and prioritize intervention efforts. Various ML techniques, as presented in Figure 8, have been used to assess NPSP. The scientific community must determine the most effective methods for NPSP and environmental pollutant assessment [49]. This classification provides researchers with a roadmap of recommended models for specific projects on NPSP [104]. It is crucial to establish the links between AI models (e.g., SVM, ANN, MLP) and other AI algorithms (e.g., GA, MC, KNN), as emphasized by Mukhamediev et al. [38] since they can improve the performance of the model.

The application of AI in NPSP offers numerous advantages, such as the ability to handle vast and complex datasets [57], as well as the ability to make precise and efficient estimations and predictions [65]. Moreover, AI’s flexibility in simulating pollution scenarios [123] and its automatic and iterative features empower researchers to develop adaptive management approaches, ensuring prompt and effective responses to pollution issues [90]. Although the applications of AI in NPSP may encounter obstacles, their advantages for NPSP may outweigh these challenges. AI-driven NPSP solutions can be pivotal in a broader context of environmental sustainability. They enhance pollution management and raise public awareness by providing accessible and real-time data [66,90,124]. This increased awareness can trigger a sense of responsibility, leading to more sustainable practices. Moreover, AI can support evidence-based policy-making by providing comprehensive data and insights, ensuring environmental policies are based on scientific rigor [125].

4.2. AI in NPSP: Opportunities and Challenges

The integration of AI into NPSP assessment and management represents new opportunities to address some of the most complex aspects of NPSP (e.g., diffuse sources, complex causes, and lack of clear, simple solutions), considering that AI is capable of learning complex, non-linear, and high-dimensional relationships directly from data, which are inherently characteristic of NPSP dynamics [9,112]. This inherent suitability translates into significant opportunities for enhancing NPSP management despite documented limitations (see Table 5). Some of the opportunities that AI presents include:

- Early Detection of Pollution Events by processing high-frequency time-series data, allowing for real-time anomaly detection (e.g., sudden spikes in pollutant concentrations), enabling rapid response to pollution incidents and mitigation of downstream ecological and health impact [57,88].

- Effective Use of Incomplete Data by inferring patterns, imputing missing values, or building robust models to improve applicability in data-scarce regions, to ensure broader geographic implementation of pollution management strategies [10,24,30].

- Precision Monitoring with Ensemble Models by combining the strengths of multiple AI models to improve prediction stability and reliability, making them highly suitable for complex or variable pollution scenarios [85,102].

- Scalable Integration Across Data Systems by facilitating data integration from diverse sources (e.g., IoT sensor networks, weather databases, satellites, GIS) [90,91] and types (e.g., meteorological, water quality, geospatial, physiochemical data) into AI models, allowing for dynamic scenario planning, pollution hotspot identification, and real-time decision support [45,74,97].

Despite these substantial opportunities, the application of AI in NPSP contexts is not without challenges. Key challenges include:

- Interpretability and Transparency (The “Black Box” Problem): The most prominent limitation is the complexity and lack of transparency in how many advanced AI models, particularly DL models (LSTM, ANN, CNN), arrive at their predictions. Often labeled as “black boxes”, these models make it difficult to understand the underlying reasoning process. This may make it difficult for any stakeholders who require clear and scientific explanations of model outputs to validate the model logic and outputs that can be communicated and trusted by the public [70,114].

- Data Availability, Quality, and Representativeness: Many AI models (e.g., DL models) require large volumes of high-quality and representative training data to perform effectively. In environmental settings relevant to NPSP (e.g., scattered monitoring stations across large watersheds, intermittent sampling), such data are often sparse, incomplete, inconsistent in quality, or imbalanced (e.g., focusing on specific conditions or locations). Furthermore, significant data heterogeneity (variability in measurement methods, spatial scales, and temporal coverage) can severely affect model generalizability, limiting their reliability when applied across diverse geographic regions or different temporal contexts than the training data [57,85].

- Computational Demands and Expertise Requirements: Many AI models (e.g., GBM, ensemble learning) impose high computational demands, often requiring access to specialized hardware like powerful GPUs and significant processing times for training and testing [24,30,85,88]. Applying these models effectively in NPSP assessment often involves processing large, complex datasets (e.g., multi-year pollutant records) and simulating hydrological and pollutant transport processes across diverse landscapes (e.g., urban areas, agricultural fields, coastal wetlands), which further increase computational demands. Moreover, the application of AI requires specialized expertise in model selection, architecture design, hyperparameter optimization, and results interpretation [53,115]. Therefore, the effective application of AI in this area requires combining AI expertise with environmental and NPSP domain knowledge. This need for interdisciplinary expertise, combined with high computational requirements, can present significant barriers to the widespread adoption and practical implementation of AI in NPSP management.

However, these challenges should not discourage the adoption of AI in NPSP research and practice, as the growing urgency of environmental degradation underscores the need for scalable, adaptive, and accurate tools like AI. Therefore, even with their shortcomings, the ability of AI to uncover pollution patterns (e.g., dominant pollutant sources), enhance predictive precision, and support evidence-based interventions highlights its growing importance as an essential instrument for sustainable and effective NPSP management.

4.3. Assumptions and Limitations

This study systematically searched peer-reviewed papers using various combinations of keywords related to AI and NPSP and the presented results represent the timeline and searchwords used. Different search timelines and terms may have resulted in different studies being identified. Additionally, it should be noted that only the “Web of Science” and ScienceDirect search engines were used for this study, which may limit the scope of coverage, potentially excluding relevant studies from other databases such as Scopus, IEEE Xplore, or regional repositories like CNKI. While non-English studies were excluded to avoid translation and interpretation challenges, we recognize this as a limitation. However, we recommend the inclusion of multilingual and regionally indexed databases in future studies to provide a more comprehensive global perspective. Some studies may have been missing, as keywords were not explicitly mentioned in the titles, abstracts, and publications. The results may not reflect all available information about AI applications in NPSP. However, we believe the selected documents contain the information necessary to draw valid and reliable conclusions.

The study also utilized bibliometric analysis, a powerful tool for analyzing large amounts of data from different sources. However, it is essential to acknowledge the limitations of bibliometric analysis. The software used for bibliometric analysis, such as Biblioshiny, can introduce inaccuracies if inputs are not thoroughly reviewed beforehand, and the programmer’s biases can affect the software’s decision-making capabilities. Despite these limitations, it is also essential to consider co-authorship and keyword analysis in this study. Authors who collaborated on multiple documents were included, and keywords with a frequency of five or more were considered. Different selection conditions would have yielded different results. Nonetheless, the findings are highly relevant to future scientific research on the applications of AI in NPSP.

5. Conclusion and Next Steps

The present study demonstrates the evolving research landscape regarding AI applications for NPSP management. It highlights the essential role of enabling technologies such as IoT, GIS, and remote sensing in facilitating real-time pollution monitoring and enhancing the accuracy and scalability of AI models. Furthermore, the study categorized the AI models while critically assessing current limitations and future research needs related to AI model development, data constraints, and the crucial need for robust governance and policy frameworks, thereby bringing together the need for expertise from both environmental science and AI modeling.

Building on these insights, we propose the following actionable steps for future research and implementation:

- Develop AI-Driven Early Warning Systems: Create real-time monitoring platforms using machine learning (e.g., LSTM, CNN) to forecast runoff events like phosphorus spikes following rainfall or pesticide discharge post-irrigation. Couple these systems with watershed models (e.g., SWAT-AI hybrids) to issue alerts and recommend pre-emptive measures such as delayed fertilizer application or buffer activation.

- Advanced Explainable and Robust AI Models: Use interpretable AI (e.g., SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), based on cooperative game theory, Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME)) to ensure transparency in predictions of NPSP. For example, explain how each feature, rainfall, land slope, and fertilizer application, contribute to increasing or decreasing nitrate concentrations in runoff, considering both global interpretability (overall feature importance across the model) and local interpretability (feature impact on individual predictions). Validate models using multi-watershed datasets across different climates and land uses. Standardize model performance reporting (e.g., RMSE, MAE, recall, F1 score), including uncertainty quantification, to facilitate reproducibility and policy uptake.

- Integrate Governance and Policy Frameworks: Develop institutional guidelines for AI-based environmental decision-making that mandate transparency, data ethics, and fairness. Engage local stakeholders (farmers, community groups, regulators) in the design and deployment phases. Address environmental justice by prioritizing pollution monitoring in historically marginalized or overburdened regions.

- Invest in Enabling Infrastructure: Fund the deployment of low-cost water quality sensors (e.g., nitrate, turbidity, pH) and remote sensing systems (e.g., drones, satellites). Develop open-access geospatial databases and cloud-computing platforms (e.g., Google Earth Engine) to allow researchers and agencies to access, share, and analyze environmental data at scale.

- Focus on Emerging and Understudied Pollutants: Use AI techniques (e.g., ensemble learning, anomaly detection) to map and model microplastic dispersion, legacy pesticides, antibiotic runoff, and emerging contaminants. Conduct integrated modeling of their sources (e.g., landfills, plasticulture), transport mechanisms, and ecological/human health risks in different agroecosystems.

A critical next phase of this work involves systematically evaluating and quantitatively ranking the performance of various AI models across key NPSP assessment domains—such as water quality forecasting, pollution source identification, and groundwater vulnerability mapping—using standardized, comparable metrics. This effort will equip researchers and practitioners with evidence-based guidance for selecting the most effective AI tools tailored to specific pollution scenarios. Ultimately, continued research and multidisciplinary collaborative efforts are essential to reach the transformative potential of AI in achieving sustainable NPSP management by enabling precision pollution control, data-informed policymaking, and sustainable environmental practices.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su17135810/s1, Table S1: Synthesis of review papers included in this study; Table S2: Sensitivity analysis.

Author Contributions

A.M. and A.A.: Conceptualization, Visualization, Methodology. A.A.: Resources, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. A.M., R.N., K.P., L.H., M.J., B.W. and A.A.: Data curation and writing—original draft preparation. A.M. and A.A.: Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA-NIFA) to Florida A&M University through Non-Assistance Cooperative Agreement grant no. 58-6066-1-044. Additionally, support from USDA-NIFA capacity building grants 2017-38821-26405 and 2022-38821-37522, USDA-NIFA Evans-Allen Project, Grant 11979180/2016–01711, USDA-NIFA grant no. 2018-68002-27920, as well as National Science Foundation Grant no. 1735235 awarded as part of the National Science Foundation Research Traineeship and Grant no. 2123440.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Herbert Franklin, and Ernesta Hunter for their feedback and editing support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahi, Y.; Dilcan, C.C.; Koksal, D.D.; Gultas, H.T. Reservoir Evaporation Forecasting Based on Climate Change Scenarios Using Artificial Neural Network Model. Water Resour. Manag. 2022, 37, 2607–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandhi, A.; Srinivas, V.V.; Nanjundiah, R.S.; Nagesh Kumar, D. Downscaling Precipitation to River Basin in India for IPCC SRES Scenarios Using Support Vector Machine. Int. J. Climatol. 2008, 28, 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandhi, A.; Srinivas, V.V.; Kumar, D.N.; Nanjundiah, R.S. Role of Predictors in Downscaling Surface Temperature to River Basin in India for IPCC SRES Scenarios Using Support Vector Machine. Intl J. Climatol. 2009, 29, 583–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovič, G. Wastewater Management Using Artificial Intelligence. E3S Web Conf. 2018, 45, 00050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morain, A.; Ilangovan, N.; Delhom, C.; Anandhi, A. Artificial Intelligence for Water Consumption Assessment: State of the Art Review. Water Resour. Manag. 2024, 38, 3113–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.W.; Lei, Y.; Lin, B.; Zhou, Y.L.; Gu, Z.H. Artificial Intelligence Model for Water Resources Management. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Water Manag. 2010, 163, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zharikova, E.P.; Grigoriev, J.Y.; Grigorieva, A.L. Artificial Intelligence Methods for Detecting Water Pollution. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 988, 022082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlenbrook, S.; Yu, W.; Schmitter, P.; Smith, D.M. Optimising the Water We Eat—Rethinking Policy to Enhance Productive and Sustainable Use of Water in Agri-Food Systems across Scales. Lancet Planet. Health 2022, 6, e59–e65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z. Assessment of Influencing Factors on Non-Point Source Pollution Critical Source Areas in an Agricultural Watershed. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 141, 109084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]