Building an Agricultural Biogas Supply Chain in Europe: Organizational Models and Social Challenges

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Context and Scope

1.2. Study Goals

2. Materials and Methods

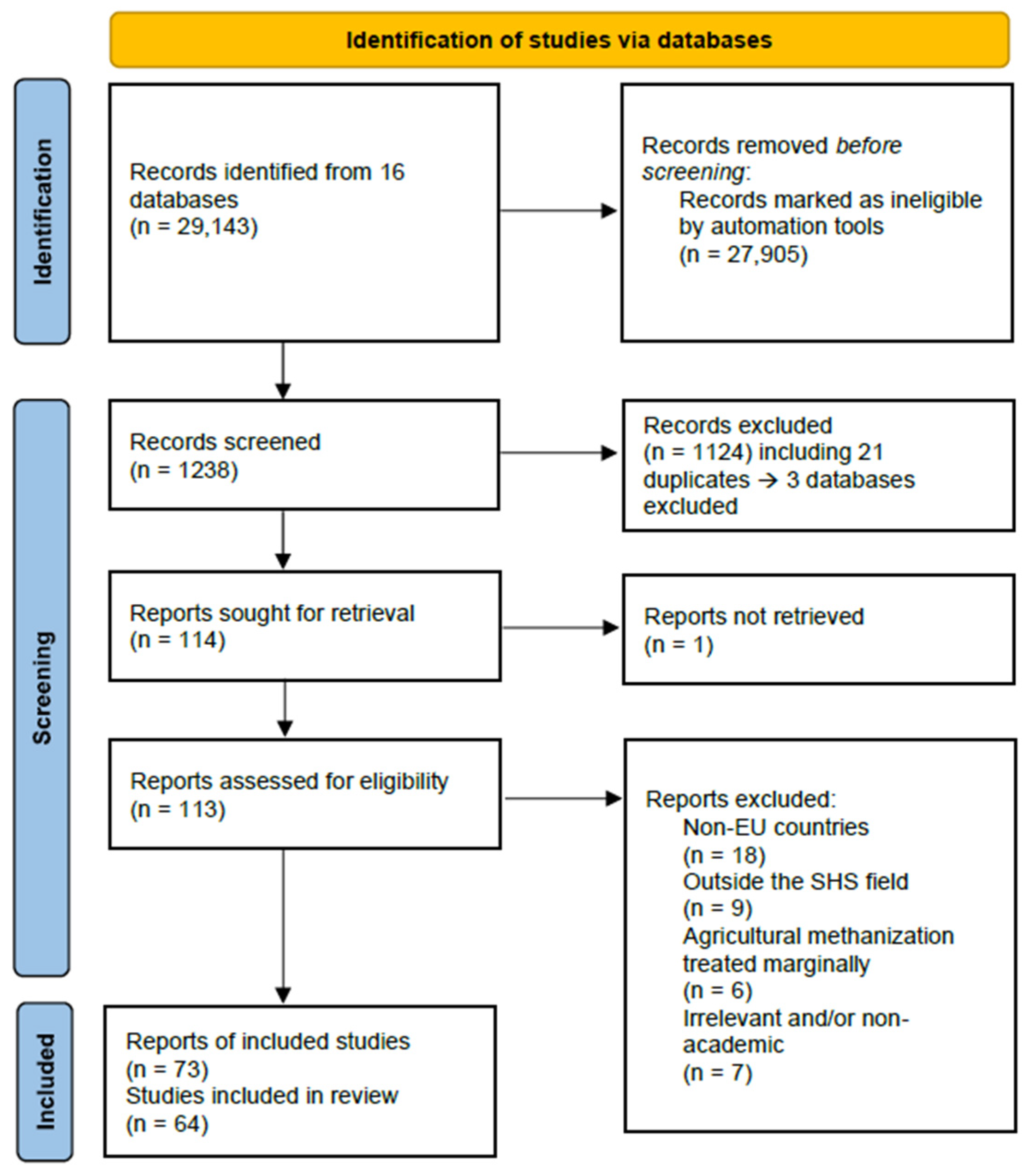

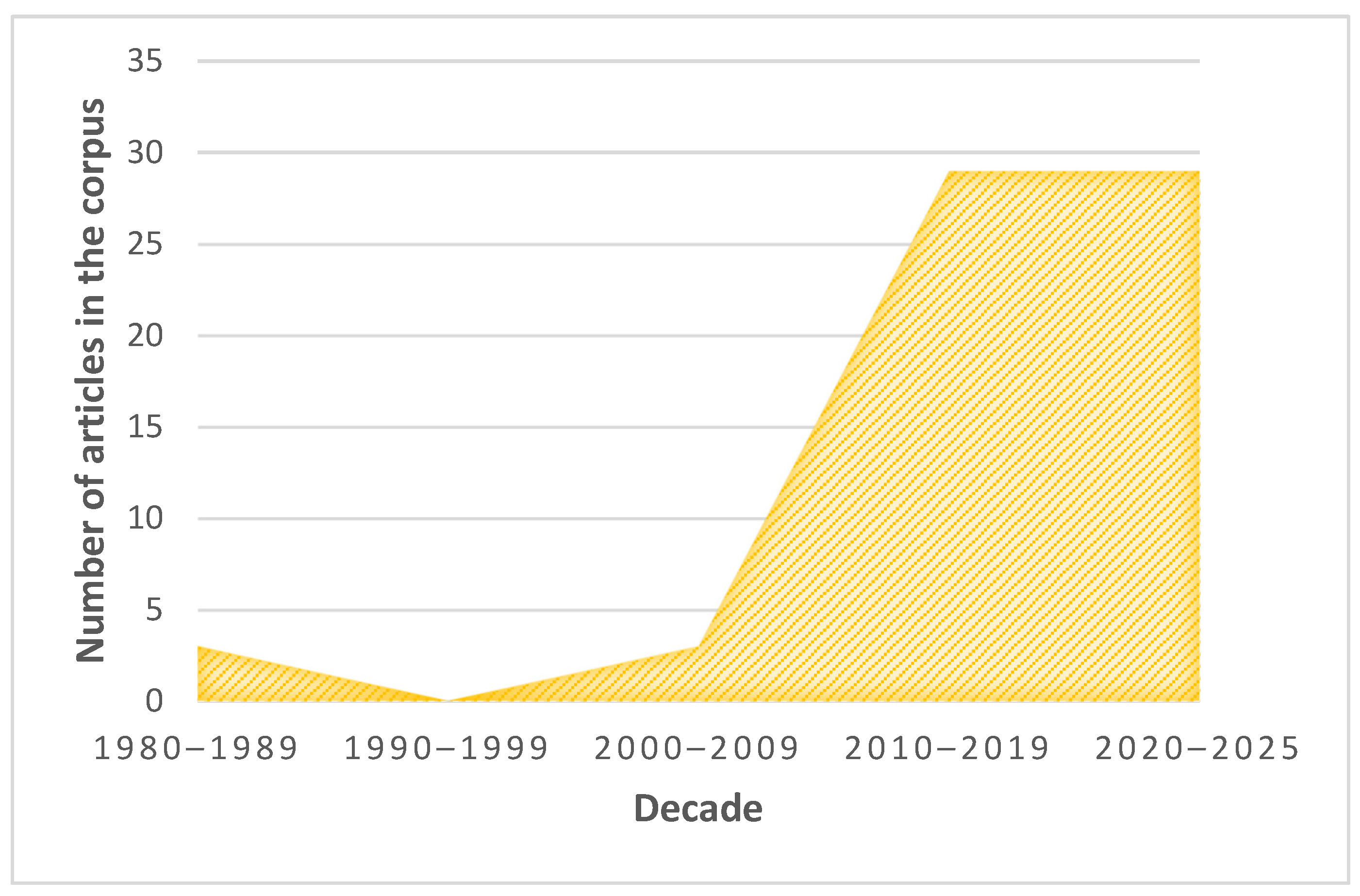

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Literature Assessment

- We focused on articles primarily dealing with European contexts (for instance, removing cases of comparisons between countries from different continents and global literature reviews), removing eighteen articles from the corpus;

- A few articles (nine more) were too far removed from the social sciences;

- Some (six more) turned out to only briefly broach anaerobic digestion. Others (seven more) were more akin to reports from actors outside the academic field.

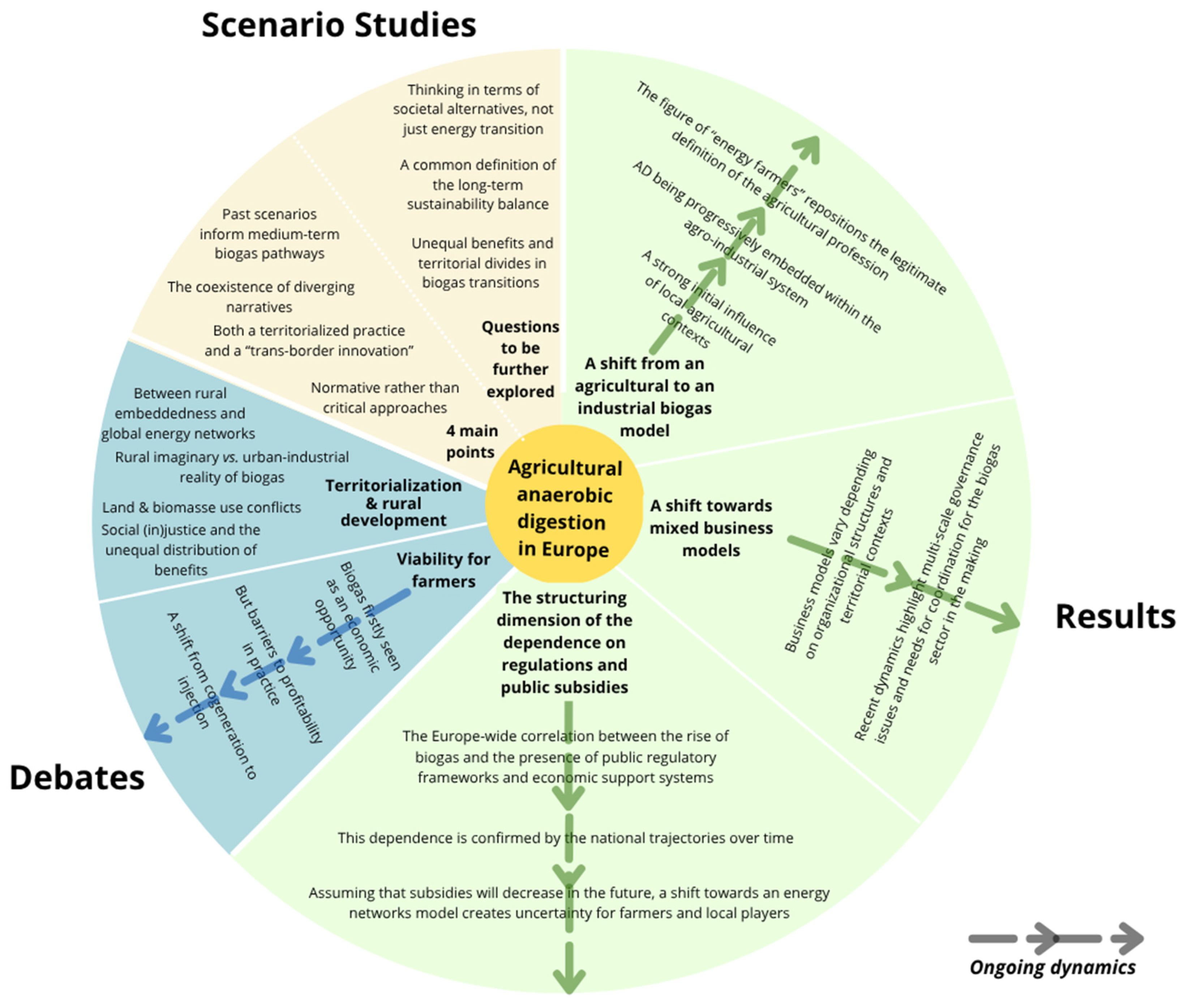

2.3. Literature Synthesis

- The initial positions of farmers and the industrial evolution;

- The typologies of the business models of farms and biogas plants;

- Contextual and regulatory tools and barriers, with a focus on the role of public subsidies and their evolution;

- The economic viability of biogas and the problem of its limited returns for farmers;

- Its contributions to local rural development;

- The current scenario and future studies.

3. Results: A European Model Based Primarily on Farmers and Public Subsidies

3.1. From an Agricultural to an Industrial Model?

3.1.1. The Role of Local Farming Contexts in the Early Development of Biogas

3.1.2. The Integration of Anaerobic Digestion into the Agro-Industrial System

3.1.3. “Energy Farmers” and the Redefinition of the Agricultural Profession

3.2. Towards Mixed Business Models?

3.2.1. How Organizational and Territorial Dynamics Shape Business Models

3.2.2. Multi-Scale Governance and Coordination Challenges

- The “internalization and symbiosis model” is characterized by a logic of self-reliance and self-sufficiency: the farmers control maintenance costs to the highest possible extent by internalizing them, use their own manure as input and limit external interventions as much as possible. Here innovation relies on an empirical approach—farmers learn by doing and gain expertise as they operate their plant. These units, which are often installed by members of the first generation of adopters (before 2015), have received—at least initially—strong support from public subsidies and favor cogeneration heating.

- The “small farmers group model” hinges on cooperation between livestock breeders and grain farmers, rethinking their agricultural projects collectively. These units require more sizeable investments and are often monitored by specialized operators. They more often hire employees, and purchase the majority of their inputs (often from cooperatives). Knowledge transmission plays a key role: breeders share their expertise on plant operation, whereas grain farmers bring their knowledge on spreading digestate.

- The “grain farmer biogas injection model” refers to projects operated by farmers specializing predominantly in grain, either individually or as a small group of farmers. These units are propped up by high initial investments, often compensated for by contracts with cooperatives and agrobusiness firms to ensure supply and biogas sales. This model is characterized by the hiring of employees from the industrial sector, trained by the manufacturers and the farmers themselves, and by a growing specialization in the plants’ administrative and commercial management.

- The “partial outsourcing and generic technology model” reflects an increased dependence on industrial actors. It is mainly adopted by farmers who invested in biogas after 2015, individually or in small groups, and who operate turnkey plants built by private operators. These units are characterized by a strong dependence on the expertise of manufacturers, the partial outsourcing of management and high investment costs due to the large numbers of actors involved. The researchers stress the challenges faced by these farmers, especially pointing to frequent technical issues (design defects, oversizing, etc.), the high bankruptcy rate and the exposure to the ebbs and flows of public subsidies.

- The emerging model of “joint projects between agricultural cooperatives and investors” is less widespread but increasingly followed. While it could strike a balance between territorial anchoring and access to financial resources, it also raises the question of governance and of the distribution of added value among the actors [19] (pp. 23–30).

3.3. The Dependence on Regulations and Public Subsidies

3.3.1. A Widespread Reliance on Subsidies

3.3.2. The Long-Term Institutionalization of Public Support in National Trajectories

3.3.3. Biogas Futures: Towards a Global Energy Network Model?

4. Discussion: How Viable Are the Biogas Supply Chains in Europe?

4.1. How Viable Is Anaerobic Digestion for Farmers?

4.1.1. Biogas Initially Perceived as an Economic Opportunity by Farmers

4.1.2. Barriers to Profitability in Practice

4.1.3. A Shift from Cogeneration to Injection

4.2. Does Farm-Fed Anaerobic Digestion Contribute to Local Rural Development?

4.2.1. Territorial Roots vs. Global Energy Transition

4.2.2. Social Justice and the Unequal Distribution of Biogas Benefits

4.2.3. Land Use Conflicts in the Context of Biogas Development

- Increased land pressure, accentuated by competition between food production and energy crop production;

- Changes in crop rotation, with fewer crops intended for human and animal consumption, and more maize and cereals harvested for anaerobic digestion;

- Social impacts, with a widening gap between farmers who have been able to invest in anaerobic digestion and others who have had no access to such economic opportunities, causing new forms of rural poverty [40].

4.2.4. The Rural Imaginary vs. The Urban–Industrial Reality of Biogas

5. Scenario Studies

5.1. Scenarios as Embedded Action-Research: A Normative Rather than Critical Approach

5.2. Agricultural Anaerobic Digestion as Both a Territorialized Practice and a “Trans-Border Innovation”

5.3. The Role of Uncertainty in Shaping Biogas Trajectories

- The greening of gas: In this narrative, biomethane is given a key role in the energy transition, and as such, biomethane production needs to be stepped up in large-scale facilities.

- “The champagne of the energy transition”: This narrative expresses doubts as to whether there are enough usable residues available and concerns about the high costs involved. Biomethane production can only be justified, therefore, if there is no other alternative strategy to move to a low-carbon economy, and the use of maize as an energy crop is not encouraged given the competition with food productions for land use.

- The “energy farmer 2.0”, associated with job creation and local economic activity.

5.4. Revisiting Past Scenarios to Inform Medium-Term Biogas Pathways

6. Outlook

6.1. Accounting for Unequal Benefits and Territorial Divides in Biogas Transitions

6.2. What Are the Long-Term Environmental and Agricultural Trade-Offs?

6.3. From Energy Transition to Societal Alternatives: Broadening the Perspective

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Uçkun, K.E.; Stamatelatou, K.; Antonopoulou, G.; Lyberatos, G. Production of biogas via anaerobic digestion. In Handbook of Biofuels Production. Processes and Technologies; Luque, R., Campelo, J., Clark, J., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Energy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 259–301. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, L.-A.; Peter, S.; Zagata, L. Conceptualising Multi-regime Interactions: The Role of the Agriculture Sector in Renewable Energy Transitions. Res. Pol. 2015, 44, 1543–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheer, A.; Sardar, M.F.; Younas, F.; Zhu, P.; Noreen, S.; Mehmood, T.; Farooqi, Z.U.; Fatima, S.; Guo, W. Trends and Social Aspects in the Management and Conversion of Agricultural Residues Into Valuable Resources: A Comprehensive Approach to Counter Environmental Degradation, Food Security, and Climate Change. Biores. Techno. 2023, 394, 130258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinát, S.; Cowell, R.; Navrátil, J. Rich or Poor? Who Actually Lives in Proximity to AD Plants in Wales? Biom. Bioener. 2020, 143, 105799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, A.P. Bounded Biofuels? Sustainability of Global Biogas Developments. Soc. Rur. 2013, 54, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alan, H.; Köker, A.R. Analyzing and Mapping Agricultural Waste Recycling Research: An Integrative Review for Conceptual Framework and Future Directions. Res. Pol. 2023, 85, 103987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brémond, U.; Bertrandias, A.; Steyer, J.-P.; Bernet, N.; Carrere, H. A Vision of European Biogas Sector Development Towards 2030: Trends and Challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 287, 125065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevzorova, T.; Kutcherov, V. Barriers to the Wider Implementation of Biogas as a Source of Energy: A State-of-the-art Review. Energy Strat. Rev. 2019, 26, 100414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, E.; Raggi, A. Out of Sight, out of Mind? The Importance of Local Context and Trust in Understanding the Social Acceptance of Biogas Projects: A Global Scale Review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 91, 102697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sourie, J.-C. L’agriculture, source d’énergie: Le point sur les techniques d’utilisation de la biomasse. Éco. Rur. 1980, 138, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amand, R.; Corbin, S.; Cordellier, M.; Deléage, E. Les agriculteurs face à la question énergétique: Mythe de la transition et inertie du changement. Sociologies 2015, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzalone, G.; Mazaud, C. L’énergiculteur, figure de la diversification en agriculture. Nouv. Rev. Trav. 2021, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attarça, M.; Lassalle de Salins, M. Quand l’entrepreneur devient entrepreneur politique. Le cas du développement de la méthanisation agricole en France. Rev. Fr. Gest. 2013, 232, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béline, F.; Girault, R.; Peu, P.; Trémier, A.; Téglia, C.; Dabert, P. Enjeux et perspectives pour le développement de la méthanisation agricole en France. Sci. Eaux Ter. 2012, 7, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béline, F.; Peu, P.; Dabert, P.; Trémier, A.; Le Guen, G.; Damiano, A. La méthanisation en milieu rural et ses perspectives de développement en France. Sci. Eaux Terr. 2013, 12, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthe, A.; Grouiez, P.; Dupuy, L. Les “upgradings stratégiques” des firmes subordonnées dans les CGV: Le cas des éleveurs investissant dans des unités de méthanisation. Rev. D’éco. Indus. 2018, 163, 187–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthe, A.; Fautras, M.; Grouiez, P.; Issehnane, S. Les formes d’unités de méthanisation en France: Typologies et scénarios d’avenir de la filière. Agr. Env. Soc. 2020, 10, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthe, A.; Grouiez, P.; Fautras, M. Heterogeneity of Agricultural Biogas Plants in France: A Sectoral System of Innovation Perspective. J. Innov. Eco. Manag. 2022, 38, 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bioteau, T.; Béline, F.; Laurent, F.; Girault, R.; Tretyakov, O.; Boret, F.; Balynska, M. Analyse spatialisée pour l’aide à la planification des projets de méthanisation collective. Sci. Eaux Ter. 2013, 12, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolzonella, D.; Fatone, F.; Cecchi, F. Aperçu de la méthanisation agricole en Italie. Sci. Eaux Terr. 2013, 12, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdin, S. Concertation, localisation, financements. Analyse des déterminants du déploiement de la méthanisation dans le Grand-Ouest français. Éco. Rur. 2020, 373, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brühne, T.; Tempel, M.; Deshaies, M. Les paysages postmodernes de l’énergie en Rhénanie-Palatinat. Rev. Géo. Est 2015, 55, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camguilhem, S. Contestation civique des unités de méthanisation agricole, une mise en discussion publique des risques. Les Enj. De L’info. Et De La Com. 2018, 18, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrière, J.-P. Les potentialités économiques de la production de biométhane en vue d’usages collectifs. Éco. Rur. 1984, 161, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condor, R. L’entrepreneuriat collectif dans la méthanisation agricole. Syst. Alim. 2019, 4, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couturier, C. Méthanisation agricole: Quelle rentabilité selon les projets? Sci. Eaux Terr. 2013, 3, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delhoume, C.; Caroux, D. Quel rôle des agriculteurs dans la transition énergétique? Acceptation sociale et controverses émergentes à partir de l’exemple d’une chaufferie collective de biomasse en Picardie. VertigO 2014, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garambois, N.; Reguer, I.; Schruijer, F.; Pirard, N. Transition énergétique et durabilité de l’agriculture: Les limites et paradoxes du développement de la méthanisation agricole. Étude comparée en Bretagne et Grand-Est. Terr. En Mouv. 2022, 55, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grouiez, P. Une analyse de filière des dynamiques de revenus de la méthanisation agricole. Notes Et Études Soc.-Éco. 2021, 49, 41–61. [Google Scholar]

- Jayet, P.-A.; Sourie, J.-C. Les valorisations énergétiques des biomasses, difficultés et promesses. Éco. Rur. 1983, 158, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jutteau, P.; Lacquement, G. Transition énergétique, transformations de l’agriculture et héritages postsocialistes en Allemagne orientale. L’Esp. géo. 2019, 48, 359–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laboubée, C.; Couturier, C.; Bonhomme, S.; Damiano, A.; Simone, H.; Tignon, E.; Paillard, E.; Lelièvre, P.; Vrignaud, G.; Dumas Larfeil, C.; et al. Methalae: Comment la méthanisation peut être un levier pour l’agroécologie? Innov. Agro. 2020, 79, 373–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levasseur, P.; Aubert, P.-M.; Berger, S.; Charpiot, A.; Damiano, A.; Meier, V.; Quideau, P. Développement d’un calculateur pour déterminer l’intérêt technicoéconomique de la méthanisation dans les différents systèmes de productions animales: Méthasim. Innov. Agro. 2011, (17), 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazaud, C.; Pierre, G. Un territoire rural dans la transition énergétique: Entre démarche participative et intérêts particuliers. Lien Soc. Pol. 2019, 82, 118–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraine, M.; Ramonteu, S.; Magrini, M.-B.; Choisis, J.-P. Typologie de projets de complémentarité culture – élevage à l’échelle du territoire en France: De l’innovation technique à l’innovation territorial. Innov. Agro. 2019, 72, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffin, F.; Dormoy, C. Le méthaniseur et le paysage. Proj. Pays. 2021, 24, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakotovao, M.; Godard, L.; Sauvée, L. Dynamique agricole d’une filière de valorisation de la biomasse: Cas de la Centrale Biométhane en Vermandois. Éco. Rur. 2021, 376, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Sáez, A.J. Des terres très sollicitées en raison du développement de la biomasse comme source d’énergie renouvelable en Espagne. Rev. Europ. Droit Env. 2005, 2, 138–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vue, S.; Garambois, N. Politique énergétique allemande et agriculture au Jura souabe: Denrées agricoles ou méthane? Éco. Rur. 2017, 362, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiland, P. Production de biogaz par les exploitations agricoles en Allemagne. Sci. Eaux Terr. 2013, 3, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolino, A.M.; Giganti, P.; Denes dos Santos, D.; Falcone, P.M. A Matter of Energy Injustice? A Comparative Analysis of Biogas Development in Brazil and Italy. Energy Res. Soc. Sc. 2023, 105, 103278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, A. Insights to the Internal Sphere of Influence of Peasant Family Farms in Using Biogas Plants as Part of Sustainable Development in Rural Areas of Germany. Energy Sust. Soc. 2012, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluemling, B.; Mol, A.P.J.; Tu, Q. The Social Organization of Agricultural Biogas Production and Use. Energy Pol. 2013, 63, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burg, V.; Troitzsch, K.G.; Akyol, D.; Baier, U.; Hellweg, S.; Thees, O. Farmer’s Willingness to Adopt Private and Collective Biogas Facilities: An Agent-based Modeling Approach. Res. Cons. Recyc. 2021, 167, 105400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadiou, J.; Aubert, P.-M.; Meynard, J.-M. The Importance of Considering Agricultural Dynamics When Discussing Agro-environmental Sustainability in Futures Studies of Biogas. Futures 2023, 153, 103218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodkowska-Miszczuk, J.; Martinát, S.; Kulla, M.; Novotný, L. Renewables Projects in Peripheries: Determinants, Challenges and Perspectives of Biogas Plants—Insights From Central European Countries. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2020, 7, 362–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnhofer, I. Organic Farming and Rural Development: Some Evidence from Austria. Socio. Rur. 2005, 45, 308–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gava, O.; Favilli, E.; Bartolini, F.; Brunori, G. Knowledge Networks and Their Role in Shaping the Relations Within the Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation System in the Agroenergy Sector. The Case of Biogas in Tuscany (Italy). J. Rur. Stud. 2017, 56, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horschig, T.; Schaubach, K.; Sutor, C.; Thrän, D. Stakeholder Perceptions About Sustainability Governance in the German Biogas Sector. Energy Sust. Soc. 2020, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igliński, B.; Piechota, G.; Iwański, P.; Skarzatek, M.; Pilarski, G. 15 Years of the Polish Agricultural Biogas Plants: Their History, Current Status, Biogas Potential and Perspectives. Clean Techno. Env. Pol. 2020, 22, 281–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, N.P.; Halila, F.; Mattsson, M.; Hoveskog, M. Success Factors for Agricultural Biogas Production in Sweden: A Case Study of Business Model Innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 2925–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriechbaum, M.; Terler, N.; Stürmer, B.; Stern, T. (Re)framing Technology: The Evolution From Biogas to Biomethane in Austria. Env. Innov. Soc. Trans. 2023, 47, 100724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyytimäki, J.; Nygrén, N.A.; Pulkka, A.; Rantala, S. Energy Transition Looming Behind the Headlines? Newspaper Coverage of Biogas Production in Finland. Energy Sust. Soc. 2018, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyytimäki, J.; Assmuth, T.; Paloniemi, R.; Pyysiäinen, J.; Rantala, S.; Rikkonen, P.; Tapio, P.; Vainio, A.; Winquist, E. Two Sides of Biogas: Review of ten Dichotomous Argumentation Lines of Sustainable Energy Systems. Ren. Sust. Energy Rev. 2021, 141, 110769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnani, N. Exploring the Local Sustainability of a Green Economy in Alpine Communities: A Case Study of a Conflict Over a Biogas Plant. Mount. Res. Dev. 2012, 32, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateescu, C.; Dima, A.-D. Critical Analysis of key Barriers and Challenges to the Growth of the Biogas Sector: A Case Study for Romania. Biom. Conv. Bioref. 2020, 12, 5989–6002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navrátil, J.; Martinát, S.; Krejčí, T.; Klusáček, P.; Hewitt, R.J. Conversion of Post-Socialist Agricultural Premises as a Chance for Renewable Energy Production. Photovoltaics or Biogas Plants? Energies 2021, 14, 7164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niang, A.; Torre, A.; Bourdin, S. How do Local Actors Coordinate to Implement a Successful Biogas Project? Env. Sci. Pol. 2022, 136, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panoutsou, C.; von Cossel, M.; Ciria, P.; Ciria, C.S.; Baraniecki, P.; Monti, A.; Zanetti, F.; Dubois, J.-L. Social Considerations for the Cultivation of Industrial Crops on Marginal Agricultural Land as Feedstock for Bioeconomy. Biof. Bioprod. Bioref. 2022, 16, 1319–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pestalozzi, J.; Bieling, C.; Scheer, D.; Kropp, C. Integrating Power-to-gas in the Biogas Value Chain: Analysis of Stakeholder Perception and Risk Governance Requirements. Energy Sust. Soc. 2019, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowar, A. Agricultural Biogas—An Important Element in the Circular and Low-Carbon Development in Poland. Energies 2020, 13, 1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plieninger, T.; Bens, O.; Hüttl, R.F. Perspectives of Bioenergy for Agriculture and Rural Areas. Out. Agri. 2006, 35, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puupponen, A.; Lonkila, A.; Savikurki, A.; Karttunen, K.; Huttunen, S.; Ott, A. Finnish Dairy Farmers’ Perceptions of Justice in the Transition to Carbon-neutral Farming. J. Rur. Stud. 2022, 90, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorda, G.; Sunak, Y.; Madlener, R. An Agent-based Spatial Simulation to Evaluate the Promotion of Electricity From Agricultural Biogas Plants in Germany. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 89, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stürmer, B.; Leiers, D.; Anspach, V.; Brügging, E.; Scharfy, D.; Wissel, T. Agricultural Biogas Production: A Regional Comparison of Technical Parameters. Renew. Energy 2021, 164, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterveer, P.; Spaargaren, G. Meeting social challenges in developing sustainable environmental infrastructures in East African cities. In Social Perspectives on the Sanitation Challenge; van Vliet, B., Spaargaren, G., Oosterveer, P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, M.; Anderberg, S. Biogas policies and production development in Europe: A comparative analysis of eight countries. Biofuels 2022, 13, 931–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator | Europe | Global |

|---|---|---|

| Share of global biogas production (2017) | 54% of global production (364 TWh) | Asia: 31%, Americas: 14% |

| Number of biogas plants (2018) | 18,202 plants | China: ≈6000 plants (mostly small-scale); USA: ≈2200 plants |

| Installed capacity for electricity generation from biogas (2018) | 12.6 GW, representing 68% of global biogas electricity capacity | Global capacity: 18.1 GW China: 0.6 GW (≈3%) USA: 2.4 GW (≈13%) |

| Biogas energy use (2018) | 88.5% of European biogas is used for electricity and heat generation via combined heat and power (CHP) systems | USA: 40% for electricity, 60% for other uses (heat generation and biomethane production) |

| Ongoing market trends | Shift towards agricultural waste utilization and biomethane production | USA: Market dominated by municipal solid waste valorization China: Rapid development of both household-scale (cooking, lighting) and industrial biogas plants |

| Projected biomethane potential for 2050 | 64.2 billion m3/year (≈4.8% of UE-28 energy consumption) | Global potential estimate: ≈200 billion m3/year |

| Share of agricultural feedstocks in biogas production | Over 70% (crops, livestock manure, agricultural residues) | USA: 25–30% China: 40% (remainder from biowaste and wastewater treatment plants) |

| References | Empirical Paper/Review | Farmer, Farming and Evolutions | Typologies and Business Models | Regulatory Frames and Public Support | Economic Viability of Methanization | Local Rural Development | Scenarios and Future Studies | Considered Areas/EU Countries |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| French-language corpus | ||||||||

| Amand et al./2015 [12] | E* | X | X | X | X | France | ||

| Anzalone, Mazaud/2021 [13] | E | X | X | X | France | |||

| Attarça, Lassalle de Salins/2013 [14] | E | X | X | X | France | |||

| Béline et al./2012 [15] | E | X | France, Germany, Denmark | |||||

| Béline et al./2013 [16] | E | X | Germany, Denmark, France, Italy | |||||

| Berthe, Grouiez, Dupuy/2018 [17] | E | X | X | France | ||||

| Berthe et al./2020 [18] | E | X | X | X | X | France | ||

| Berthe, Grouiez, Fautras/2022 [19] | E | X | X | X | X | France | ||

| Bioteau et al./2013 [20] | E | X | France | |||||

| Bolzonella, Fatone, Cecchi/2013 [21] | E | X | Italy | |||||

| Bourdin/2020 [22] | E | X | France | |||||

| Brühne, Tempel, Deshaies/2015 [23] | E | X | Germany | |||||

| Camguilhem/2018 [24] | E | X | France | |||||

| Carrière/1984 [25] | E | X | X | X | France | |||

| Condor/2019 [26] | E | X | X | X | France | |||

| Couturier/2013 [27] | E | X | X | France | ||||

| Delhoume, Caroux/2014 [28] | E | X | X | France | ||||

| Garambois et al./2022 [29] | E | X | X | X | X | X | France | |

| Grouiez/2021 [30] | E | X | X | X | X | X | France | |

| Jayet, Sourie/1983 [31] | E | X | X | X | France | |||

| Jutteau, Lacquement/2019 [32] | E | X | X | X | Germany | |||

| Laboubée et al./2020 [33] | E | X | X | X | X | France | ||

| Levasseur et al./2011 [34] | E | X | France | |||||

| Mazaud, Pierre/2019 [35] | E | X | X | France | ||||

| Moraine et al./2019 [36] | E | X | X | X | France | |||

| Raffin, Dormoy/2021 [37] | E | X | France | |||||

| Rakotovao, Godard, Sauvée/2021 [38] | E | X | X | France | ||||

| Sánchez Sáez/2005 [39] | E | X | X | Spain and the EU | ||||

| Sourie/1980 [11] | E | X | X | X | France | |||

| Vue, Garambois/2017 [40] | E | X | X | X | X | Germany | ||

| Weiland/2013 [41] | E | X | Germany | |||||

| English-language corpus | ||||||||

| Alan, Köker/2023 [6] | R | X | X | X | Worldwide | |||

| Bertolino et al./2023 [42] | E | X | X | Italy, Brazil | ||||

| Bischoff/2012 [43] | E | X | X | Germany | ||||

| Bluemling, Mol, Tu/2013 [44] | R | X | X | Worldwide | ||||

| Brémond et al./2021 [7] | R | X | X | Germany, Denmark, Sweden, France, Italy | ||||

| Burg et al./2021 [45] | E | X | X | Switzerland | ||||

| Cadiou, Aubert, Meynard/2023 [46] | R | X | France | |||||

| Chodkowska-Miszczuk et al./2020 [47] | E | X | X | Poland, Slovakia, Czech Republic | ||||

| Darnhofer/2005 [48] | E | X | Austria | |||||

| Gava et al./2017 [49] | E | X | X | Italy | ||||

| Horschig et al./2020 [50] | E | X | X | Germany | ||||

| Igliński et al./2020 [51] | E | X | X | Poland | ||||

| Karlsson et al./2017 [52] | E | X | X | Sweden | ||||

| Kriechbaum et al./2023 [53] | E | X | X | X | Austria | |||

| Lyytimäki et al./2018 [54] | E | X | X | X | Finland | |||

| Lyytimäki et al./2021 [55] | E | X | X | X | Finland | |||

| Magnani/2012 [56] | E | X | X | Italy | ||||

| Mancini, Raggi/2022 [9] | R | X | X | Worldwide | ||||

| Martinát, Cowell, Navrátil/2020 [4] | E | X | X | Wales | ||||

| Mateescu, Dima/2020 [57] | E | X | X | Romania | ||||

| Mol/2013 [5] | E | X | X | Worldwide (especially EU—Asia) | ||||

| Navrátil et al./2021 [58] | E | X | Czech Republic | |||||

| Nevzorova, Kutcherov/2019 [8] | R | X | X | X | X | Worldwide (32 countries) | ||

| Niang, Torre, Bourdin/2022 [59] | E | X | X | France | ||||

| Panoutsou et al./2022 [60] | E | X | X | 18 EU countries | ||||

| Pestalozzi et al./2019 [61] | E | X | Germany | |||||

| Piwowar/2020 [62] | E | X | X | Poland | ||||

| Plieninger, Bens, Hüttl/2006 [63] | R | X | X | X | X | Germany | ||

| Puupponen et al./2022 [64] | E | X | X | X | Finland | |||

| Sheer et al./2024 [3] | R | X | Worldwide | |||||

| Sorda, Sunak, Madlener/2013 [65] | E | X | X | X | Germany | |||

| Stürmer et al./2021 [66] | E | X | Switzerland, Germany, Austria | |||||

| Sutherland, Peter, Zagata/2015 [2] | E | X | X | Germany, Czech Republic, United Kingdom | ||||

| Germany | France | UK | Sweden | The Netherlands | Denmark | Austria | Italy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biogas output (MWh per inhabitant), 2020–2021 | 1 | 0.1–0.3 | 0.1 | 0.25 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.15 | 0.1 |

| Economic instruments at the disposal of farmers | Investment subsidies, feed-in tariffs and green certificates | Investment subsidies, feed-in tariffs, tax bonuses and cuts | Investment subsidies (bidding), feed-in tariffs and green certificates | Investment subsidies, tax cuts | Investment subsidies, feed-in tariffs and tax cuts | Investment subsidies, feed-in tariffs and tax cuts | Investment subsidies (bidding) and green certificates | Investment subsidies, feed-in tariffs |

| Regulatory framework | Stable, favorable policies | Recent but favorable framework | Regulated support framework | Robust regulation | Strong regulation, fiscal challenges | Ambitious regulations | Changing legislation | Less structured legal framework |

| Main challenges | Technological lock-in, production costs | Lack of long-term support, slow adoption | Setting up costs, subsidy dependence | Lack of agricultural substrates, high costs | Bureaucratic complexity, limited market | Rigid regulation | Lack of infrastructure | Weak public support, high costs |

| Medium-term growth potential | Very high, emphasis on innovation | Growth expected, particularly in the use of agricultural byproducts | Moderate growth with targeted support policies | Stable growth, but limited by market size | Moderate growth with fiscal challenges | High potential but bureaucratic challenges | Moderate potential, increased use of agricultural byproducts | Slow growth, but increasing attention to organic waste |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hamman, P.; Dziebowski, A. Building an Agricultural Biogas Supply Chain in Europe: Organizational Models and Social Challenges. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5806. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135806

Hamman P, Dziebowski A. Building an Agricultural Biogas Supply Chain in Europe: Organizational Models and Social Challenges. Sustainability. 2025; 17(13):5806. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135806

Chicago/Turabian StyleHamman, Philippe, and Aude Dziebowski. 2025. "Building an Agricultural Biogas Supply Chain in Europe: Organizational Models and Social Challenges" Sustainability 17, no. 13: 5806. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135806

APA StyleHamman, P., & Dziebowski, A. (2025). Building an Agricultural Biogas Supply Chain in Europe: Organizational Models and Social Challenges. Sustainability, 17(13), 5806. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135806