Abstract

The rural landscape serves as a window to showcase regional culture and can drive the development of the rural cultural tourism industry. However, driven by the rural revitalization strategy, the construction of rural landscapes in the Yangtze River Delta region faces the challenges of homogeneity and lack of authenticity. A regional evaluation of the rural landscape and strategic suggestions are key to solving this problem. Therefore, this study selected three representative villages in the Yangtze River Delta region and established a regional evaluation model of the rural landscape in the Yangtze River Delta from the perspective of the ecological–production–living concept, utilizing the analytic hierarchy process, a tourist questionnaire survey, IPA, and Munsell color analysis. The results show that (1) the core indicator of the rural landscape regionality is the life landscape, followed by the production landscape, and finally, the ecological landscape; (2) the overall satisfaction of the rural landscape is high, and the satisfaction of the water network landscape is significantly higher than other indicators; (3) the results of IPA show that what needs to be maintained are traditional dwellings and historical relics, and what needs to be improved are sign design and rural public art design; (4) Munsell color analysis shows that the characteristics the of rural landscape in the Yangtze River Delta region are diverse and inclusive. This study is of great significance for maintaining the characteristics of the rural landscape in the Yangtze River Delta region and promoting the protection of rural landscape style under different regional conditions.

1. Introduction

In the context of globalization, rural landscapes, exemplifying the ideal of harmonious human–nature coexistence, have garnered increasing attention from the global community [1]. The intrinsic connection between humans and the natural environment is reflected not only in maintaining ecological balance but also in profoundly influencing psychological well-being [2]. This urban population growth has led to challenges such as environmental degradation, the reduction in green spaces, and heightened living stresses, thereby prompting a reassessment of the significant value of rural landscapes [3]. Concurrently, the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) emphasizes that rural tourism continues to make a growing contribution to the global economy by providing employment opportunities for local communities and promoting diversified rural economic development [4]. Increasing attention is also being directed toward the conservation and sustainable development of rural landscapes. They are recognized not only for their aesthetic value but also as essential for biodiversity conservation, cultural heritage preservation, and the enhancement of community cohesion [5]. China’s expansive rural areas and substantial agricultural population form the cornerstone of its agrarian civilization, rendering rural development a matter of unique cultural significance. In recent years, rural landscape construction has become a pivotal element in China’s rural revitalization strategy [6]. In the Yangtze River Delta—the most economically developed region in China—rural landscapes exemplify the characteristic features of Jiangnan water towns [7]. However, industrialization and urbanization in recent years have eroded these landscapes’ distinctive regional traits [8].

Since the 1978 reform and opening-up, China has consistently prioritized the development of farmers, agriculture, and rural areas, recognizing these as its foremost national objectives [9]. Over the past decade, the importance of rural development has steadily increased, accompanied by shifts in the driving forces behind rural landscape construction. In 2017, China introduced the Rural Revitalization Strategy, aimed at enhancing the competitiveness and productivity of its agricultural sector and facilitating the transition from a large agricultural producer to a strong agricultural power [10]. During this period, efforts to develop rural landscapes were primarily driven by the need to meet the population’s material requirements through agriculture, leading to substantial transformations in rural landscapes. In 2023, China proposed the “Beautiful and Harmonious Villages” initiative, emphasizing the integration of livability with economic vibrancy in rural areas [11]. This policy underscores the aesthetic value of rural areas, marking a shift in the focus of rural landscape construction from material needs to aesthetic priorities. While these policies have driven forward rural landscape development, challenges such as diminishing regional distinctions and the homogenization of rural landscapes remain prevalent [12].

Theoretically, the concept of ecological–production–living landscapes, unique to China and rarely applied internationally, has significantly influenced the development of the country’s rural regions. In November 2013, the Third Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee adopted the Decision on Major Issues in Deepening Reform, which called for establishing a spatial planning framework and delineating regulatory boundaries for production, living, and ecological spaces. Subsequently, in December 2013, the Central Urbanization Work Conference stressed the need to construct a “reasonable structure of production, living, and ecological spaces” to promote efficient production, livable local environments, and sustainable ecological systems. Since its introduction, the concept of ecological–production–living landscapes has been continuously refined in China, evolving into a well-developed theoretical framework [13]. The concept aims to coordinate the development of production, living, and ecological spaces to foster human–nature harmony and advance sustainable socioeconomic growth [14]. The ecological–production–living landscapes of diverse towns provide customized pathways for rural landscape planning, characterized by their unique functional attributes and spatial logics. The natural underpinnings of ecological landscapes establish the environmental carrying capacity and conservation thresholds essential for planning. The industrial attributes of production landscapes influence the functional zoning and circulation layout within spatial configurations. The cultural heritage embedded in living landscapes infuses place-making with its intrinsic value.

At the practical level, rural landscapes in the Yangtze River Delta region are confronted with several pressing issues. Firstly, ecological systemic imbalance manifests in diminished water network connectivity, shrinking natural shorelines, and homogenized agricultural development, leading to biodiversity decline and the erosion of local ecological gene pools. Secondly, the authenticity of living landscapes is compromised; facade-style renovations have distorted architectural aesthetics, while rural depopulation has left traditional dwellings abandoned and in disrepair. Moreover, cultural symbols such as ancestral halls and productive landscapes have experienced memory disconnection due to excessive exploitation. Thirdly, the value chain of productive landscapes has fractured, with agricultural non-grainization and the proliferation of homogenized cultural tourism industries. Outsourcing specialty products and superficialization of handicraft experiences have resulted in low industrial added value, trapping these landscapes in a dual crisis of commodification and loss of local value. Consequently, the comprehensive enhancement of rural landscapes is pivotal to successfully implementing the rural revitalization strategy.

In academic research, the evaluation of rural landscapes has emerged as a significant area of study. In response to the developmental needs of rural areas, rural landscape evaluation primarily encompasses multiple domains, focusing on aesthetic quality [15], landscape sensitivity assessment, and landscape threshold evaluation. Most rural landscape evaluations tend to emphasize spatial correlation analysis from the perspective of environmental protection [16]. For research on rural landscape assessment in China, studies on ecological and aesthetic functions are relatively abundant [17,18,19]. However, research on social functions remains comparatively limited [20], particularly in terms of macro-level assessments that comprehensively evaluate the economic, cultural, and ecological values of rural landscapes in China. Therefore, establishing an operational comprehensive evaluation system for rural landscapes holds considerable research value. This approach has practical implications for rural landscape assessment and guides rural landscape planning.

In the realm of methodological applications, contemporary research on rural landscape evaluation is predominantly grounded in the theoretical frameworks of four primary academic schools of landscape evaluation [21]. The most frequently employed evaluation methods are categorized into two primary approaches: the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) and psychophysical methodologies [22]. Within the psychophysical school, methods include the Scenic Beauty Estimation (SBE) method [23,24], the Beauty Estimation Method (BIB-LCJ), the Semantic Differential (SD) method, the Human Physiological and Psychological Index (PPI) method [25], single-factor evaluation, and the Law of Comparative Judgment (LCJ). While the SBE method effectively evaluates many landscapes, it lacks sufficient comparative analysis [26]. The BIB-LCJ method enhances the possibility of landscape comparisons but involves a significant workload, limiting the sample size [27]. The SD method employs adjective pairs to reflect psychological perceptions of landscapes at a cognitive level. However, its outcomes are influenced by factors such as the selection of landscape sample photos, the determination of adjective pairs, and variations among evaluators [28]. The PPI method objectively assesses landscape aesthetics by measuring physiological indicators like brain waves and heart rate; however, its high equipment costs and challenges in large-scale application restrict its utility. The single-factor evaluation method facilitates rapid quantitative analysis of individual landscape elements but overlooks the synergistic effects of multiple factors. The LCJ method, a statistical ranking approach based on pairwise comparisons, yields reliable results but is constrained by sample size and is prone to causing evaluator fatigue. The AHP, a multi-criteria decision-making method, compares and ranks problems based on predefined criteria, constructing a hierarchical structure to identify optimal solutions [29]. By circumventing the need for extensive dataset analysis, decomposing complex problems, and simplifying calculations [30], AHP is adopted in this study for its methodological rigor and practical applicability.

This study is grounded in the theoretical framework of ecological–production–living spaces and seeks to address three critical issues in current rural landscape evaluation by integrating the methods of color geography. First, existing evaluation systems struggle to quantify the value of rural landscapes. Second, academic understanding of this theory remains largely confined to its role as a policy tool, with insufficient in-depth applied research. Third, there is a lack of correlation between the analysis of visual elements of rural landscapes and their functional aspects. Through this approach, the study aims to bridge these gaps and provide a more comprehensive understanding of rural landscape evaluation.

To achieve the aforementioned objectives and address the lack of a comprehensive landscape evaluation system in rural areas, this study establishes a rural landscape evaluation framework based on the ecological–production–living spaces concept. This framework comprises three primary elements—ecological landscapes, living landscapes, and productive landscapes—along with 25 specific indicators. Additionally, considering that color is a crucial representation of regional cultural identity [31] and plays a key role in the diversity of rural landscapes [32], this study innovatively incorporates color assessment of the research area, with the results integrated into subsequent recommendations. Through the analysis of color characteristics in typical rural cases in the Yangtze River Delta, the study not only refines existing evaluation methods but also enhances the applicability of the ecological–production–living spaces theory in rural contexts. The research outcomes provide concrete guidance for rural landscape construction in the Yangtze River Delta while offering a new theoretical perspective and practical paradigm for enhancing regional aesthetics in global rural development.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Rural Landscape Evaluation

The rural landscape encompasses natural features and agricultural production activities [33]. Among these, rural agricultural landscapes constitute a significant component of the overall rural landscape [34]. Agricultural activities, historical heritage, and folk traditions collectively characterize rural agricultural landscapes. The evaluation of rural landscapes involves conducting surveys and analyses within designated areas [35]. Employing appropriate landscape evaluation techniques facilitates the identification of rural resources and provides recommendations for the conservation-oriented development of rural landscapes.

The academic community has evaluated rural landscapes across various dimensions, including rural landscape resource evaluation [34], landscape diversity evaluation [36], landscape characteristic evaluation [37], landscape multifunctionality evaluation [38], and landscape quality evaluation [39]. From a methodological perspective, rural landscape research has employed a variety of approaches, with quantitative methods playing a pivotal role. These methods include Scenic Beauty Evaluation (SBE) [23,24], single-factor evaluation, comparative judgment (LCL), Semantic Differential analysis (SD), fuzzy comprehensive evaluation (FCE), and AHP [40,41], with SBE and AHP being the most widely applied. Previous studies on rural landscapes have predominantly utilized single-factor evaluation methods, resulting in a lack of research that assesses rural landscape resources from multiple perspectives. Concurrently, the rapid advancement of rural construction in China has led to issues such as the loss of cultural identity, reduced landscape distinctiveness, and the homogenization of development, highlighting the importance of regional studies on rural landscapes in advancing rural revitalization and landscape planning [42].

2.2. Ecological–Production–Living Landscapes and Colors

The ecological–production–living landscapes represent the fundamental spatial domains for human activities [43]. Production landscapes, in particular, are centered on providing processing and management services for material production [44]. Ecological landscapes are vital for maintaining the natural conditions necessary for human survival and for delivering ecological goods and services [45]. Living landscapes focus on meeting human needs for living and leisure, serving as regional spaces for residence and daily activities [46]. The ecological–production–living landscapes, as an innovative concept integrating rural natural and cultural landscapes, seamlessly combine production, living, and ecological landscapes. This approach not only enhances rural resource utilization but also promotes the harmonious development of rural ecology, economy, and culture, fostering a balanced relationship among humans, nature, the economy, and society, which is essential for advancing rural landscapes [40,47].

In the fields of sustainable development and territorial spatial planning, the theory of ecological–production–living spaces, as a core innovation in China’s ecological civilization construction, has garnered significant scholarly attention in recent years. At the theoretical construction level, Ling (2022) systematically elucidated the theoretical essence of optimizing ecological–production–living spaces, highlighting the concept’s role in harmonizing human–land relationships and restructuring spatial functions as a critical policy tool for resolving urban–rural development conflicts [48]. The study emphasized the synergy effect of these spaces, ultimately providing a three-dimensional framework of “ecological conservation, production upgrading, and living quality enhancement” for the rural revitalization strategy. In terms of regional practices, Tang (2003) used an elasticity model to simulate the rural human settlement environment in Changsha, revealing that frequent transitions between production and ecological spaces were the primary cause of landscape system vulnerability [49]. This study validated the critical role of the dynamic balance of ecological–production–living spaces in enhancing regional resilience. Long (2012), employing a matter–element model to assess land suitability in Zengcheng, Guangzhou, proposed a technical pathway for optimizing the functional integration of ecological–production–living spaces through land consolidation [50]. This approach provided a quantitative analytical paradigm for urban–rural integration. These studies collectively underscore the theoretical and practical significance of the ecological–production–living framework in promoting sustainable development and spatial optimization.

From an international comparative perspective, Seto’s (2012) global meta-analysis of urbanization revealed that East Asia, represented by China, is undergoing rapid “non-agricultural transformation of production spaces”, highlighting the unique applicability of the ecological–production–living spaces theory in regions with acute human–land conflicts [51]. The shrinking of living spaces and the fragmentation of ecological spaces caused by population outflows necessitate the functional restructuring of these three spaces to achieve rural revitalization, aligning with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals’ call for urban–rural balance. In terms of methodological innovation, Long (2012) introduced the theory of land use transition, constructing a classification system for ecological–production–living spaces and uncovering the evolution of Chinese rural areas from “production-dominated” to “integrated ecological–production–living ” paradigms [50]. These contributions underscore the theoretical and practical relevance of the ecological–production–living framework in addressing global and regional challenges in sustainable development.

However, existing research still faces three significant gaps. First, there is insufficient micro-level analysis of the coupling mechanisms of ecological–production–living landscapes, particularly the role of regional cultural symbols such as colors and architectural forms in spatial differentiation. Second, the international academic community’s understanding of China’s ecological–production–living spaces theory remains largely confined to policy interpretation, lacking theoretical feedback grounded in local practices. This study aims to address these gaps by integrating landscape ecology, color geography, and space syntax to construct an ecological–production–living landscape evaluation system tailored to the rural areas of the Yangtze River Delta. This approach seeks to bridge the research divide between “theoretical Sinicization” and “practical internationalization”, offering a more nuanced and applicable framework for both local and global contexts. Third, with the advancement of rural landscape construction, socio-economic development, and rising material living standards, the demand for personalization in rural landscape design has increased significantly. Beyond meeting basic material needs, the visual aesthetics of landscapes have become an increasingly important area of focus. On the one hand, rural color, as a vital component of visual aesthetics, constitutes a significant research area in rural planning and landscape design. Conversely, color is the most regionally distinctive core element of village landscapes and serves as a key criterion for assessing their quality [52]. Therefore, advancing regional studies on village colors and integrating the ecological–production–living landscapes concept with regional color research [53] can more effectively capture the integrated representation of land, spatial structures, and material elements.

2.2.1. Rural Ecological Landscape

Ecological resources represent the most significant developmental advantage of rural regions [54]. Conceptually, ecological landscapes provide a sustainable environment for human survival and deliver essential goods and services [55]. The primary factors shaping rural ecological landscapes are topography, climate, and biodiversity. Topography is the most regionally distinctive feature of rural China. For example, the names of rural areas often reflect their topographical features [56,57]. Furthermore, topography provides the foundational framework that shapes the spatial arrangement of human settlements [58,59]. Variations in elevation and slope affect the movement of surface materials and energy flows, thereby shaping the structure and spatial distribution of rural land use types [60]. Climate is a critical determinant of agricultural productivity and the quality of rural living environments [61,62]. In China, rapid urbanization has significantly reduced the capacity of rural areas to adapt to climate change [63]. Compared to urban regions, rural areas in China are more dependent on natural systems, making them more vulnerable to changes that impact daily life [64]. However, the lack of climate governance frameworks in most rural areas of China exacerbates the risks to sustainable development [61,65]. Biodiversity is a defining feature of rural landscapes. The interdependence between human activities and local flora and fauna is a central aspect of rural life [66]. During the 1950s, scientists in Europe and North America began focusing on the conservation of rural biodiversity, including farmland birds, bats, and hedgerows [67]. Scholars, aiming to balance environmental conservation with the EU’s agricultural context, introduced the concept of “rewilding”, which seeks to restore the dynamism and natural wildness of rural ecosystems [68]. The interrelationship between human activities and native species [66] highlights the critical question of how to utilize native biodiversity to guide the development of rural landscapes in China [69].

2.2.2. Rural Life Landscape Characteristics

The rural living landscape encompasses both tangible and intangible cultural landscapes shaped by human interaction with nature. It serves as a tangible medium for storytelling, spatially representing the history of the populace and preserving the cultural memory and essence of rural life [70]. The tangible cultural landscape of rural areas constitutes the physical manifestation of living landscapes, including rural architecture [71,72], historical sites [73,74,75], and rural exhibition spaces [76,77,78]. Rural architecture, in particular, plays a pivotal role in expressing the regional uniqueness of rural living landscapes. Rural architecture in China demonstrates significant regional variation, especially in ancient structures that predate industrial civilization. Examples include the Hakka tulou, characterized by circular, square, and octagonal designs; Huizhou architecture, known for its white walls and black tiles; and the cave dwellings of northern Shaanxi, a distinctive cave-style housing formed on the Loess Plateau. Furthermore, rural buildings with diverse modern architectural aesthetics function as repositories of rural collective memory [79].

Intangible landscapes constitute an essential component of living landscapes. They embody implicit cultural expressions that encapsulate humanity’s integration of production and life, illustrating the interplay of economic, political, and ideological dimensions, as exemplified by local performances [80,81], culinary traditions [82,83], and folk practices [84,85]. The rural living landscape is intrinsically linked to rural culture and serves as a vital medium for showcasing rural cultural heritage. However, differences in geography, lifestyle, and cultural foundations lead to rural living landscapes exhibiting significant regional uniqueness.

2.2.3. Rural Production Landscape Characteristics

Rural production landscapes are shaped by the derivative development of rural and agricultural processes, serving as territorial spaces primarily dedicated to agricultural production while also fulfilling ecological functions. These landscapes employ efficient, energy-conserving, and eco-friendly production methods to transform natural resources into material goods, thereby meeting the demands of production and daily living [86].

As a defining feature that distinguishes rural landscapes from urban ones [87], production landscapes are primarily expressed through public art and the rural night economy. Rural public art design serves as a vital expression of artistic engagement in rural areas, contributing to the revitalization of rural cultural spirit and enhancing the tourism experience [88]. The rural night economy refers to a diverse nighttime consumption market rooted in rural living landscapes, encompassing dining, tourism, shopping, entertainment, sports, exhibitions, and performances [89]. The emergence of the rural night economy has significantly transformed rural production landscapes.

In contemporary China, rural industries are transitioning from traditional agriculture to leisure agriculture, progressing toward rural tourism development [90]. Leveraging tourism to stimulate agricultural development can promote the restructuring of the agricultural industry [91]. These changes will have a substantial impact on rural production landscapes.

2.2.4. The Color of Rural Landscapes

Color is the “soul” of landscape design. As a core component of landscape design, its significance extends beyond the material level of visual perception to the spiritual dimensions of cultural symbolism, ecological adaptability, and emotional experience, making it the essence of landscape design. From the perspective of visual cognition theory, Gestalt Psychology reveals the holistic perception mechanism of human vision towards color, where differences in brightness, saturation, and hue construct the spatial hierarchy and visual order of landscapes [92]. This theoretical foundation underscores the profound role of color in shaping both the aesthetic and functional aspects of landscapes. In the experience of landscapes, color is perceived visually, tied to tangible entities, and represents the most dynamic and unpredictable aspect of visual perception [93]. In the 1960s, French color scientist Professor Jean-Philippe Lenclos introduced the concept of “landscape color characteristics”, which includes elements such as topography, plant ecology, soil color, cultural significance, vernacular architecture made from local materials, and distinctive decorations observed in folklore and festivals [94]. Color is the primary language of landscape, defining the spirit of a place through visual impact and psychological cues before individuals interpret its form and function [95]. This perspective underscores the foundational role of color in shaping human perception and emotional engagement with landscapes, emphasizing its significance in the design process.

Rural colors, often considered the most direct cultural “living fossils”, play a crucial role in showcasing cultural confidence [96]. For example, vibrant and visually appealing landscape facilities can enhance the aesthetic quality and atmosphere of residential areas [97]. Therefore, rural colors serve as a visual abstraction of rural ecological–production–living landscapes. Analyzing rural colors in a manner tailored to local conditions offers both a direct visual assessment of rural regional characteristics and a meaningful reflection of rural culture. From the perspective of cultural semiotics, Roland Barthes defines color as a “visual symbol carrying social significance” [98], whose application in landscapes essentially represents the materialization of cultural encoding. For instance, the use of yellow glazed tiles in Chinese classical gardens symbolizes imperial authority, while the white walls and black tiles of Jiangnan water towns metaphorically convey the philosophy of “harmony between humans and nature”. These examples illustrate how color systems achieve the visual translation of regional culture. Jean-Philippe Lenclos’ research in color geography further demonstrates that regional color landscapes are the result of long-term interactions among climatic conditions, resource endowments, and cultural traditions [99]. This perspective highlights the deep interconnection between color, culture, and environment in shaping landscape aesthetics.

From the perspective of ecological design theory, the environmental regulation function of color makes it a crucial interface connecting artificial landscapes with natural systems. Appropriate color configurations can mitigate the disruption of biological behaviors caused by human interventions. For instance, the natural color schemes of native plants in urban green spaces help maintain the foraging rhythms of insects and birds, while the preservation of “site memory colors” such as rust red and cement gray in industrial site transformations promotes functional integration between artificial landscapes and natural ecosystems through visual continuity [100]. This approach underscores the ecological significance of color in fostering harmonious interactions between human-made and natural environments.

In contemporary landscape design practice, the soulful role of color is further exemplified in its dynamic narrative capabilities. Spanish designer Agustín Pérez creates a chromatic dialog between the deep blue of the sea and the beige of architectural structures, incorporating the interplay of light and shadow with tidal changes to construct an ecological narrative with a temporal dimension [100]. This concept of treating color as a “fluid design language” demonstrates that color is not merely an overlay of visual elements but a central link connecting landscape functions, culture, and ecology. It endows spaces with unique identity, awakens collective memory, regulates environmental perception, and ultimately shapes the emotional paradigms of human interaction with space. This perspective highlights the transformative power of color in creating meaningful and immersive landscape experiences.

2.3. Summary

The introduction of the ecological–production–living landscapes concept provides a comprehensive theoretical framework for rural landscape conservation and development. The reconstruction of rural ecological–production–living landscapes entails not only the creation of new landscape forms but also the reorganization of relationships between humans and nature, humans and society, and interpersonal connections. Therefore, the rational planning of production, living, and ecological spaces is essential for promoting rural landscape development within the framework of ecological civilization. Although significant academic attention has been devoted to the ecological, production, and living dimensions of rural landscapes, research on their regional characteristics remains relatively limited. This study integrates the ecological–production–living landscapes concept with rural color studies to explore the regional characteristics of rural landscapes in depth, providing both theoretical and practical guidance for their high-quality development.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

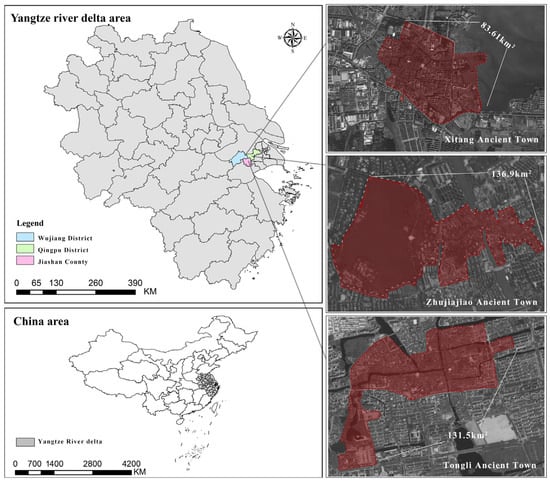

This research focuses on three representative rural areas in the Yangtze River Delta region of China as empirical case studies: Tongli Town in Wujiang District, Suzhou, Jiangsu Province; Xitang Town in Jiaxing, Zhejiang Province; and Zhujiajiao Town in Qingpu District, Shanghai (Figure 1). In the Chinese administrative system, towns represent a primary level of administrative division and house various government agencies. These towns serve as rural areas, comprising multiple villages. In urban regions, the equivalent administrative division to towns is the sub-district office, which consists of several communities at the sub-district level. Towns encompass both natural scenery and culturally significant landscapes resulting from human activities, including traditional villages, farmhouses, countryside stages, and rural public art. Geographically, the three towns are situated in adjacent county-level administrative areas, each belonging to distinct provincial jurisdictions. Strategically, while the three towns fall under different administrative jurisdictions, they are integrated within a national policy framework for coordinated development in the Yangtze River Delta region. From the perspective of cultural customs, the three towns are located within China’s Wu cultural area [101], sharing linguistic and traditional similarities while exhibiting profound distinctions from other regions of China. The ancient towns of Tongli, Xitang, and Zhujiajiao are exemplary cases for interpreting rural landscape construction in the Yangtze River Delta from ecological, production, and living dimensions. These towns fully embody the ecological foundation of “water network polder fields”, the living pattern of “water–land symbiosis”, and the productive model of “agricultural, cultural, and tourism integration”. Representing wetland conservation, cultural consumption, and urban–rural symbiosis development paths, respectively, their differentiated practices offer diverse paradigms for regional rural revitalization. The current status of their ecological–production–living landscapes is as follows. This selection provides a comparative framework for understanding the multifaceted approaches to sustainable rural development in the region.

Figure 1.

Study area.

3.1.1. Ecological Landscape: Commonalities and Divergences in Natural Foundations and Governance Approaches

The ecological landscapes of the three towns are all located in the core area of the Yangtze River Delta, exhibiting minimal differences. Each town relies on the natural foundation of “water network polder fields”, forming an ecological pattern of “parallel rivers and streets, water–land symbiosis”. For instance, Tongli’s waterways and 49 ancient bridges create a complete water system, Xitang’s 9 waterways and 24 stone bridges form an “eight-zone connected” water network, and Zhujiajiao’s Cao River and Dianpu River constitute a “golden waterway”. All three towns maintain the ecological functions of their water bodies through measures such as river dredging and water circulation projects. For example, Tongli has completed ecological restoration for over 20 streets and all waterways, while Zhujiajiao has established a smart river chief system and promoted the remediation of dead-end rivers. Tongli, centered around a national wetland park with a wetland coverage rate of 85.41% [102], features a composite ecosystem of forests, fields, and water networks, emphasizing authenticity and biodiversity in ecological conservation. Xitang focuses on “blue-green intertwined” ecological restoration, such as the garden-style renovation around Xiangfu Lake, which added 360,000 square meters of greenery [103] and integrates natural and cultural landscapes through its “ecological shoreline connectivity project”. Zhujiajiao highlights “urban–rural symbiosis” in ecological governance, balancing agricultural conservation and tourism development through ecological compensation mechanisms, while promoting prefabricated buildings and green energy applications, resulting in a more composite ecological landscape characteristic of urban suburbs.

3.1.2. Living Landscape: Tensions and Adaptations in Traditional Continuity and Modern Transformation

All three towns preserve the classic Jiangnan architectural style of “white walls and black tiles with small bridges and flowing water”, while emphasizing dynamic conservation. For example, Tongli adheres to the principle of “repairing the old as it was” to restore cultural heritage sites like the Tuisi Garden, Xitang authentically preserves 16 intangible cultural heritage items such as field songs and paper-cutting, and Zhujiajiao maintains the commercial-residential layout of “streets in front and rivers behind”. Each town employs smart management systems, such as Tongli’s “Smart Ancient Town” and Xitang’s “Digital Twin”, to enhance residents’ quality of life. Tongli, with around 12,000 indigenous residents, centers its living landscape on “traditional water town life”, preserving folk activities like lianxiang dancing, with high community engagement. Xitang, the most commercialized, retains daytime scenes such as riverside laundry and teahouse performances, while transforming into a modern entertainment hub at night with its “moonlight economy”, featuring light corridors and live music. Zhujiajiao fosters strong interactions between locals and tourists through experiences like traditional letter-writing at the Qing Dynasty Post Office and making Apo Zongzi (glutinous rice dumplings), though commercial activities pose some challenges to the authenticity of daily life.

3.1.3. Productive Landscape: Circulation and Integration of Industrial Models and Cultural Assets

From the perspective of productive landscapes, all three towns have developed production chains that transform cultural heritage into tourism consumption. For instance, Tongli leverages cultural heritage sites like the Tuisi Garden to promote educational tourism, Xitang has created a national cultural tourism IP through its Hanfu Culture Week, and Zhujiajiao positions itself as a “world vacation hub” to develop business tourism. Each town emphasizes the revitalization of traditional handicrafts, such as embroidery in Tongli, indigo dyeing in Xitang, and pickle-making in Zhujiajiao. Tongli’s productive landscape features a composite model of “agriculture + culture”, preserving traditional farming practices like rice cultivation while transforming intangible cultural heritage through spaces like the “Water Town Wedding Customs Museum”. Xitang is characterized by “tourism + cultural creativity”, with immersive experiences like “Jiangnan Hundred Scenes” and an extended Hanfu industry chain, showcasing a youthful and trendy productive landscape. Zhujiajiao stands out for its diverse business and leisure activities, adopting a “small scenic areas + self-operated events” model after eliminating entrance fees to attract business clientele. It also integrates modern industries like biopharmaceuticals and sports, reflecting the highest degree of urbanized integration in its productive landscape.

Overall, Tongli, Zhujiajiao, and Xitang, as typical water town settlements in the Yangtze River Delta, share common ecological–production–living landscape features rooted in water town culture. However, they also exhibit certain divergences due to differences in geographical location and development paths (Table 1). In terms of ecological landscapes, all three towns are situated in the same geographic region, characterized by flat terrain and a crisscrossing water network typical of the Yangtze River Delta. Regarding living landscapes, they all embody a cultural atmosphere of “valuing commerce and emphasizing literature”, preserving the intrinsic cultural ambiance of “small bridges, flowing water, and households” in the region. From the perspective of productive landscapes, tourism and agriculture are highly developed in all three towns, reflecting a well-balanced state of ecological–production–living landscapes. These characteristics make them representative and exemplary cases within the Yangtze River Delta region.

Table 1.

Ecological–production–living landscapes of Tongli Ancient Town, Zhujiajiao Ancient Town, and Xitang Ancient Town.

3.2. Study Design

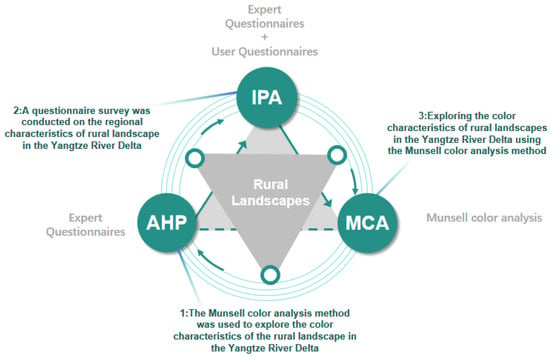

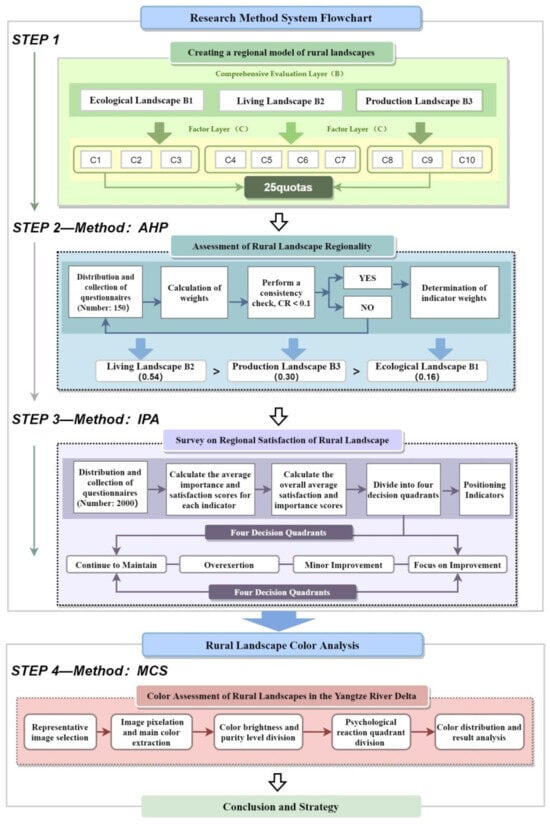

Initially, a rural landscape indicator evaluation system is constructed from the “production–living–ecology” perspective, employing the AHP to assess the significance of various rural landscape elements. Subsequently, a questionnaire survey is administered to evaluate visitor satisfaction regarding the regional characteristics of the triangular rural landscape, and the results are integrated with the findings from the layer analysis method to analyze the importance and satisfaction of the rural landscape. Additionally, utilizing the Munsell color analysis method, this study investigates the color characteristics of rural landscapes in the Yangtze River Delta. Finally, based on the results of the preceding research, strategic recommendations for the construction of rural landscapes are presented. The research structure is depicted in Figure 2. The flowchart of the research methodology system is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the conceptual hierarchy of the study.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the research methodology system.

3.2.1. Assessment of Rural Landscape Regionality

Research on rural landscapes began in the 1960s in countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States [104]. For instance, the UK developed a rural evaluation system in response to the 1986 Countryside Act, emphasizing that evaluation before design is an effective method for protecting rural landscapes. In the 1990s, British landscape scholar Bacon argued that landscape evaluation should focus on conservation value, landscape resources, aesthetic value, and spatial integrity. The United States established natural resource landscape evaluation systems in 1979 and 1986 [105]. Korean scholar Sung utilized Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to evaluate mountain landscapes [106]. German researcher Steinhardt applied fuzzy judgment theory and hierarchical methods to evaluate landscape cases [107]. Gulinck constructed a landscape evaluation framework based on visuality, integrity, and diversity, applying it to practical cases [108]. Czech scholars Miklos and Ruzicka proposed a landscape ecological planning method [109], encompassing ecological evaluation, landscape ecological analysis, landscape components, and practical recommendations, which has been well-received. These studies collectively highlight the evolution and diversity of approaches in rural landscape evaluation and planning.

Research in China started later, but in recent years, many scholars have proposed evaluation systems and methods for rural landscapes to provide reliable solutions for landscape planning, protection, and sustainable development. Liu Binyi et al. (2002) developed a landscape evaluation system based on five levels and 21 indicators, including compatibility, sensitivity, accessibility, and scenic beauty of rural landscapes [110]. Chen Wei (2007) introduced the AVC comprehensive evaluation system for rural landscapes, focusing on three target layers: vitality, attractiveness, and carrying capacity [111]. Ding Wei (1994) established a rural landscape ecological evaluation system based on the ecological environment assessment of Haimen County, Nantong, incorporating 36 indicators across three systems: agricultural production, rural industry, and residential life [17]. Xiao Duning (1998) proposed criteria for landscape ecological evaluation, including uniqueness, diversity, livability, functionality, and aesthetic value [112]. Liu Liming (2003) constructed a rural landscape evaluation system using three dimensions: aesthetic effect, ecological quality, and social impact [21]. Lu Bingyou (2001) built a landscape ecological evaluation system from four perspectives: ecology, resources, society, and economy of agricultural landscapes [113]. These studies collectively reflect the growing emphasis on comprehensive and multidimensional approaches to rural landscape evaluation in China.

The AHP is a multi-criteria decision-making approach introduced by T.L. Saaty in the 1980s, which combines qualitative and quantitative analysis systems [114]. The AHP method compares and ranks items according to established criteria and gathers respondents’ preferences via surveys to evaluate the relative importance of these items. A hierarchical structure is created through pairwise comparisons, leading to the determination of the optimal solution.

This paper, drawing on extensive historical and cultural materials related to the Yangtze River Delta, constructs a rural landscape evaluation system for Jiangnan from the perspective of ecological–production–living landscapes. It builds upon Liu Shilin’s (2011) classification of Jiangnan cultural resources [115] and references Professor Zhou Wuzhong’s Neo-Ruralism theory [116], which emphasizes the harmony of ecology, living, and production. Additionally, it incorporates domestic and international rural landscape evaluation indicators. The evaluation system is designed based on the following three principles: (1) The indicators should reflect the essence and developmental patterns of Yangtze River Delta culture; (2) the content of each indicator should embody the ecological and regional characteristics of the Yangtze River Delta rural landscapes; (3) the indicator system should integrate the industries and industrial chains of the Yangtze River Delta rural areas. This approach ensures a comprehensive and culturally grounded framework for evaluating rural landscapes in the region.

Therefore, this research will utilize the AHP methodology to develop a rural landscape evaluation system from the perspectives of ecological, production, and living spaces. The evaluation criteria and content for various goal layers will be represented through four hierarchical levels: A (Goal Layer), B (Factor Layer), C (Indicator Layer), and D (Sub-Indicator Element Layer). The A layer constitutes the rural landscape evaluation framework. The B layer classifies the landscapes into ecological, production, and living categories. The C layer further classifies ecological landscapes into topographical and geomorphological, climatic, and biodiversity landscapes; living landscapes into architectural, folk, culinary, and spiritual landscapes; and production landscapes into agricultural, industrial, and tourism landscapes. The D layer is detailed based on the preceding factor layer, culminating in a total of 25 sub-indicators. Based on the aforementioned standards, this establishes the evaluation model tree for rural landscapes in the Yangtze River Delta (Table 2).

Table 2.

Regional factors of rural landscape.

The significance of the model tree is evaluated on a 9-point scale. The AHP questionnaire is expected to distribute 150 copies, comprising 50 to doctoral candidates in design-related disciplines, 50 to university educators in design fields, and 50 to personnel from relevant government agencies in the three towns. The mean scores of the selected experimental subjects will be utilized to outline the relative importance scale values among the factors, and SPSS 22. will be employed for weight calculations. The formula for calculating weights is as follows:

In the equation, n refers to the number of evaluation factors; ( = 1, 2, …, n) is the value derived from the comparison of the relative importance between the factor and the k factor. Consequently, the weight value of each evaluation factor relative to the A goal layer can be determined, as expressed in the following formula:

The maximum eigenvalue is

And a consistency check is performed; the formula is

3.2.2. Questionnaire Survey on Rural Landscape Satisfaction

This study will conduct a questionnaire survey to assess the satisfaction levels of rural landscapes in the three towns. The survey will reference the Visual Resources Management (VRM) questionnaire, a landscape evaluation method developed by the Bureau of Land Management of the U.S. Department of the Interior for assessing the value of land landscapes. This research modifies the VRM system by incorporating two additional layers into the evaluation structure, categorizing the options into five categories: “Very Satisfied”, “Satisfied”, “Neutral”, “Unsatisfied”, and “Very Unsatisfied”. To assist respondents in indicating their attitudes, each indicator will be explicitly described using these five attitude categories.

This paper conducted a reliability analysis on the questionnaire using SPSS software, specifically employing the Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient method to test the consistency of the questions. The formula is as follows:

In this formula, n represents the total number of questions in the scale, denotes the variance of scores for the i-th question, and is the variance of the total scores across all questions. In addition to the qualitative questionnaire content of questions 1–16, a reliability analysis was conducted on the comprehensive satisfaction scores for the 25 indicators of ecological–production–living landscapes in question 17. The results are as follows:

The overall reliability of the questionnaire exceeds 0.7 (Table 3), while the reliability for the evaluation of ecological–production–living landscape indicators is 0.967 (Table 4). This demonstrates that the questionnaire has high reliability in evaluating rural landscapes in the Yangtze River Delta and assessing ecological–production–living landscape indicators.

Table 3.

Overall reliability statistics.

Table 4.

Reliability statistics for ecological–production–living indicators.

A reliability analysis of the items in the overall questionnaire yielded the following results:

In terms of questionnaire validity, among the respondents, 57.58% were female and 42.42% were male. The majority had an educational level of bachelor’s degree or higher, with the most common income range being CNY 10,000 to 20,000. Most tourists were from Jiangsu, Shanghai, Zhejiang, and Anhui, with a significant portion being government and corporate employees. The rural tourism attractions drew a highly educated demographic, predominantly consisting of nearby tourists and residents. This indicates that the sample is representative of the target population, enhancing the validity of the questionnaire results.

The detailed content of the rural landscape satisfaction survey questionnaire aligns with the D-level indicators of the AHP questionnaire. The questionnaire survey was conducted in an online format, utilizing the Questionnaire Star function available in the WeChat mobile app. The plan was to distribute 2000 online survey questionnaires, with distribution scheduled for the year 2024.

3.2.3. IPA of the Importance and Satisfaction Levels of Rural Landscape Regionality

This research utilizes the Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA) method to investigate the relationship between the importance and satisfaction levels of rural landscapes from the perspectives of production, living, and ecology. The IPA method is a commonly applied survey analysis technique for integrated evaluation, known for its objectivity and clarity.

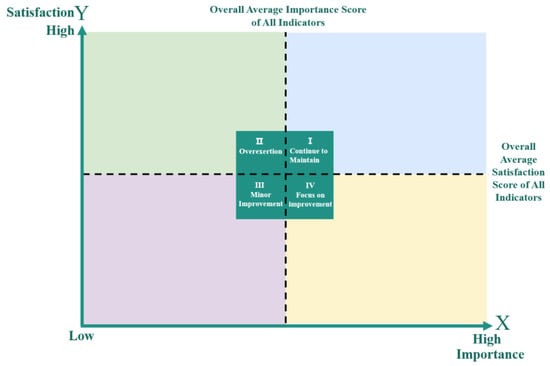

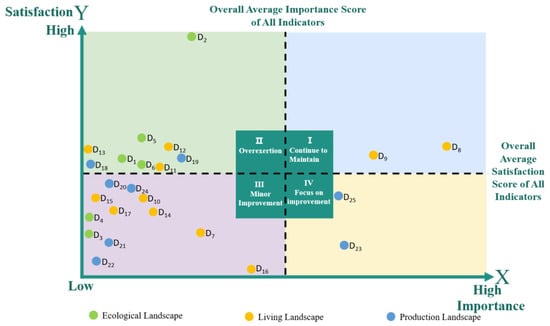

In the IPA, the X-axis denotes the importance scores of the indicators, while the Y-axis indicates the satisfaction scores of the indicators. The importance values are plotted on the X-axis and the satisfaction values on the Y-axis, with the intersection of the X and Y axes serving as the origin, forming quadrants in the coordinate system. The operational procedure for IPA is outlined as follows: The initial step involves calculating the average importance score and the average satisfaction score for each indicator. The second step involves calculating the total average importance score and the total average satisfaction score for all indicators. The third step involves using the total average importance score of all indicators as the dividing point for the X-axis and the total average satisfaction score of all indicators as the dividing point for the Y-axis, distinguishing the quadrants into four areas: “Continue to Maintain”, “Focus on Improvement”, “Minor Improvement”, and “Overexertion” (Figure 4). The fourth step involves positioning each indicator in the appropriate area according to its average importance score and average satisfaction score.

Figure 4.

Explanation of the IPA method.

This study’s IPA consists of 25 indicators. These 25 indicators correspond to the “Sub-factor Layer D” in the AHP and align with the rural landscape evaluation questionnaire. In the IPA, the X-axis denotes the importance of rural landscapes, and the values on the X-axis will utilize the weights of each indicator from the AHP in the regional evaluation of rural landscapes. The Y-axis indicates the satisfaction level of rural landscapes, with the values on the Y-axis derived from the results of the rural landscape evaluation questionnaire. To facilitate calculations, the satisfaction survey for rural landscapes will undergo value assignment. In the rural landscape evaluation questionnaire, the scoring is as follows: “Very Satisfied” receives five points, “Satisfied” receives four points, “Neutral” receives three points, “Unsatisfied” receives two points, and “Very Unsatisfied” receives one point.

3.2.4. Evaluation of Rural Landscape Colors

Using the IPA (Importance-Performance Analysis) results for the ecological, production, and living landscapes, factors that most require improvement (focus on improvement) and those that perform best (Continue to Maintain) were selected for color analysis. This approach ensures a balanced strategy of leveraging strengths and addressing weaknesses in future landscape design. The focus on improvement, which are areas of utmost importance but that received the lowest satisfaction levels, warrant particular attention. If these factors include multiple indicators, the top three most critical elements are prioritized for in-depth analysis and improvement. Similarly, the Continue to Maintain factors are also analyzed to ensure their sustained performance. This method ensures that landscape design is targeted and effective, addressing key areas for enhancement while maintaining existing strengths.

This research will investigate the color features of Tongli Town in Suzhou, Xitang Town in Hangzhou, and Zhujiajiao Town in Shanghai through Munsell color analysis, along with the factors affecting these color characteristics. The Munsell Color System (MCS) is a color classification and notation system established in 1905 by American artist and educator A.H. Munsell, aimed at standardizing and quantifying colors for more accurate description, classification, and identification. The Munsell Color System consists of three fundamental components: hue, value, and chroma. Hue denotes the basic property of color. The Munsell system divides hue into 10 levels, comprising five primary hues (red, yellow, green, blue, and purple) and five intermediate hues (yellow-red, green-yellow, blue-green, purple-blue, and red-purple). Various hues within the Munsell Color System can evoke distinct visual experiences and emotional reactions.

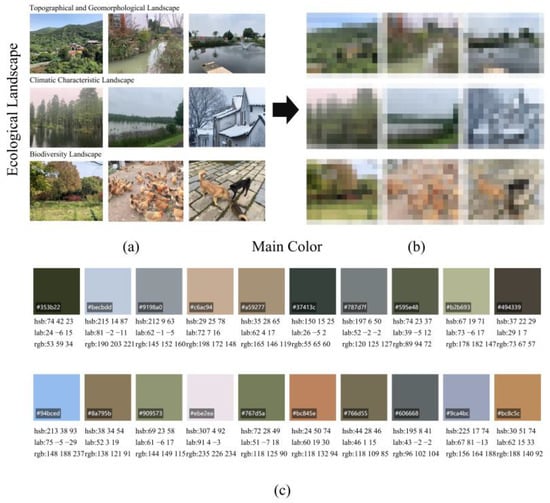

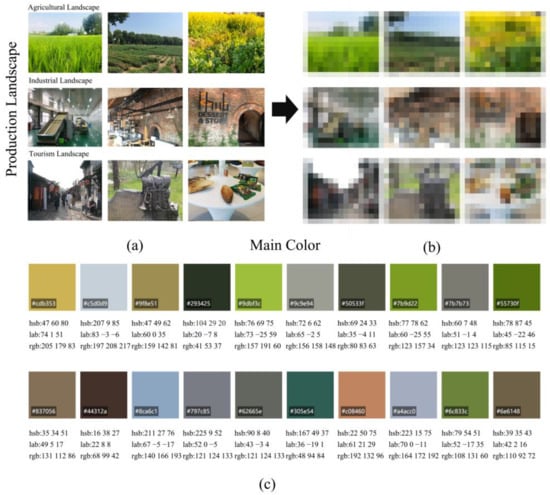

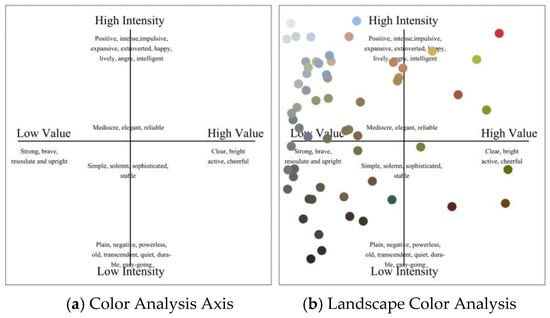

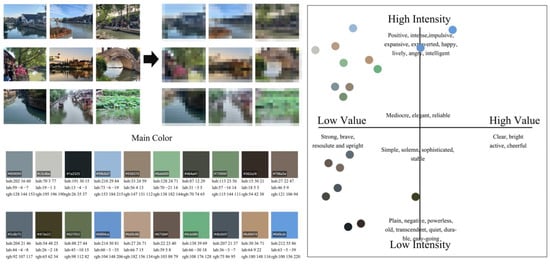

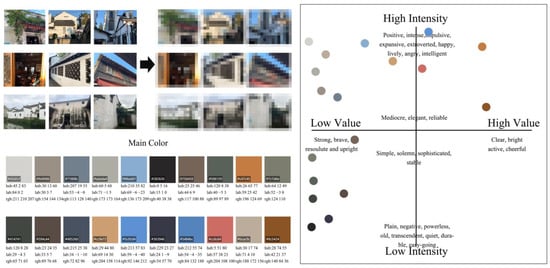

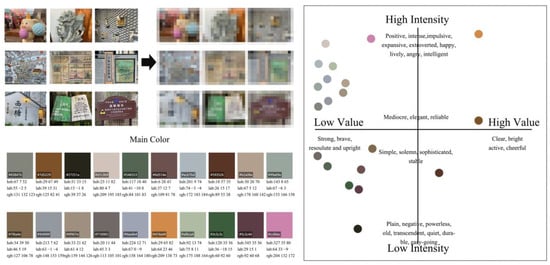

The procedure for assessing the colors of rural landscapes is outlined below. Initially, representative images of rural landscapes are selected (Figure 5a, Figure 6a and Figure 7a). These images undergo pixelation to extract the dominant colors(Figure 5b, Figure 6b and Figure 7b), which are then organized by brightness to determine the main color composition of the rural landscape (Figure 5c, Figure 6c and Figure 7c). Subsequently, color brightness and purity are divided into four quadrants according to the psychological responses they elicit at varying levels of brightness and purity. Ultimately, the extracted colors are placed in the quadrants based on their brightness and purity (Figure 8a). The concentration of color points provides insights into the overall psychological impact of the rural landscape (Figure 8b). To ensure a balanced perspective on production, ecology, and daily life, photos were selected according to the classification of this study. For ecological landscapes, three photos each of topography, climatic features, and biodiversity were chosen. For living landscapes, three photos each of architecture, local lodgings, cuisine, and spiritual landscapes were selected. For productive landscapes, three photos each of agriculture, industry, and tourism were included. These photos were pixelated using Photoshop, and SPSS software was used to statistically analyze the 20 dominant colors from the pixel data, thereby determining the primary color palette of the rural landscapes (Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8). The following color analysis method is illustrated using photos taken by the research team in rural areas of the Yangtze River Delta.

Figure 5.

Process of extracting dominant tones from ecological landscapes.

Figure 6.

Process of extracting dominant tones from living landscapes.

Figure 7.

Process of extracting dominant tones from productive landscapes.

Figure 8.

The distribution of color character coordinates of the main colors of the ecological-living-ecological landscape.

4. Results

4.1. Topography, Architectural Landscapes, and Tourism Landscapes Are the Most Critical Factors Within the Ecological, Production and Living Landscapes

According to the results of the AHP questionnaire, the living landscape serves as the primary indicator of rural landscape regionality, followed by the production landscape and the ecological landscape (Table 5). At the indicator level, topography and geomorphology are identified as the most critical aspects of the ecological landscape, while the architectural landscape predominates in the living landscape. Additionally, the tourism landscape is the most significant component of the production landscape. Among the 25 specific indicators, key factors include traditional dwellings, historical relics, signage design, rural nightscapes, and public art design. From an ecological landscape perspective, the Yangtze River Delta region exhibits pronounced water network features, which significantly represent its regional identity. The flora and fauna are inherently regional, making plant and fauna landscapes vital representations of regional characteristics and placing them in a relatively prominent position. In terms of living landscape characteristics, traditional dwellings and historical relics serve as core elements in expressing the regional identity of rural landscapes in the Yangtze River Delta. Regarding production landscape characteristics, public art design and signage design play crucial roles, emphasizing that artistic aesthetics are primary objectives of rural landscapes in the Yangtze River Delta. This focus aligns closely with the implementation of China’s rural revitalization strategy, particularly concerning the growth of rural tourism.

Table 5.

Weight distribution of scheme levels in the assessment of rural landscape regionality.

4.2. Certain Factors in the Living and Productive Landscapes Require Improvement in Satisfaction Levels

This study ultimately collected 1983 valid questionnaires. The survey results indicated that respondents expressed a high degree of satisfaction with rural landscapes overall (Table 6). Among the individual survey items, “satisfied” was the most frequently selected option, followed by “neutral”, “very satisfied”, “dissatisfied”, and “very dissatisfied”. The combined proportion of respondents selecting “dissatisfied” and “very dissatisfied” across all items was less than 4%. However, approximately 30% of respondents rated their satisfaction with rural landscapes as “neutral”.

Table 6.

Questionnaire results of rural landscape visitors.

The questionnaire indicates that the rural ecological environment is the most significant appeal of rural landscapes and the key feature that distinguishes them from urban landscapes. The rural landscapes in the Yangtze River Delta are rich in cultural significance, with their poetic charm and iconic imagery of small bridges, flowing streams, and homes creating a distinct regional impression. The natural rural landscapes of the Yangtze River Delta receive high satisfaction ratings, particularly the water network-based ecological landscapes, which should be emphasized in future planning to develop water-themed ecological landscapes representative of the region. Future planning and design should prioritize enhancing the design of traditional dwellings, historical relics, signage design, handicrafts ornaments, and village exhibition spaces.

4.3. The IPA (Importance-Performance Analysis) Indicates That Most Indicators Are in a Good State, While a Small Number of Indicators in the Productive Landscape Urgently Require Improvement

According to the results of the IPA (Figure 9), out of the 25 indicators, two are categorized as “Maintain Performance”, specifically historical relics and traditional dwellings. Nine indicators are classified as “Over-Exertion”, namely water network landscapes, plant landscapes, mountain landscapes fauna landscapes, regional vernaculars, village feast traditions, seasonal folk customs, agricultural products, and agricultural planting areas. Twelve indicators are categorized as “Secondary Improvement”, including temperature and humidity conditions, rainy season landscapes, village exhibition space, soral literature, traditional performing arts, regional culinary specialties, spatial layout, traditional belief systems, product processing facilities, rural nightscapes, industrial buildings, and handicraft ornaments. Two indicators are classified as “Key Improvement”, specifically public art design and signage design. The “Maintain Performance” category contains fewer indicators, while the “Secondary Improvement” category encompasses the most, suggesting that the regional characteristics of rural landscapes still have room for enhancement.

Figure 9.

IPA results.

4.4. The Design of Ecological–Production–Living Landscapes Needs to Focus on Several Key Color Factors

By conducting a color evaluation of key factors in the ecological–production–living landscapes of the three ancient towns, the factors requiring focused attention are identified as follows: the water network landscape in ecological landscapes, traditional dwellings, and historical relics in living landscapes, and signage design and public art in productive landscapes.

First, the water network landscape received the highest satisfaction score in the IPA, which is directly linked to the well-developed water systems in the Yangtze River Delta rural areas. Each ancient town has created a series of waterfront landscapes around its water networks, and the ambiance of small bridges, flowing water, and households has become a major attraction for tourists and a signature feature of the region. The mature development of water network landscapes allows for color analysis to identify their dominant color characteristics, which can then be referenced in the design of water network landscapes in other rural areas.

Second, the IPA results show that traditional dwellings and historical relics in the living landscapes also achieved high satisfaction and high importance, making them the most well-developed factors in the three ancient towns. Due to the effective preservation of ancient town buildings and their subsequent commercial development, many ancestral halls and former residences have been well-maintained. Analyzing the colors of these buildings provides critical design insights for the inheritance and protection of traditional architecture in the Yangtze River Delta rural areas.

Third, rural signage design and public art are identified as factors in urgent need of improvement. Color analysis can determine whether these elements lack vitality. As seen in the earlier color analysis of the Yangtze River Delta, most rural colors tend to be steady and tranquil, with vibrant colors primarily coming from tourism landscapes, which create an enthusiastic atmosphere and enhance visitor experiences, thereby stimulating consumption. Signage design plays a crucial role in guiding human flow in urban and rural spaces, necessitating the use of warm and lively colors to empower its function.

4.4.1. Color Analysis of the Water Network Landscape in Ecological Landscapes

The primary colors of the water network landscape are evenly split between high-purity, low-brightness tones, and low-purity, low-brightness tones (Figure 10). Overall, the palette tends toward darker shades. This is primarily due to the brickwork (RGB 121, 106, 94) of the embankments and arched bridges, which are constructed using local materials. Additionally, the presence of moss and other aquatic plants on these materials contributes to the darker colors near the shore (RGB 26, 35, 37). Most ancient towns retain traditional wooden structures, resulting in darker hues for waterfront buildings (RGB 54, 42, 38). These color characteristics provide valuable design references for the renovation of waterfront structures in the Yangtze River Delta rural areas. The water network landscape also features numerous plants along the banks, predominantly evergreen species with minimal seasonal variation, whose colors mainly fall within the high-purity, low-brightness quadrant (RGB 138, 182, 144; RGB 115, 144, 111; RGB 98, 112, 82; RGB 108, 176, 128). The water quality in the three ancient towns is excellent, with some high-purity, low-brightness colors representing the inherent colors of the water (RGB 128, 144, 153) and reflections of the sky (RGB 153, 184, 215; RGB 104, 148, 206). This color combination creates a comfortable rural environment.

Figure 10.

The color of the water network landscape of the three villages and the distribution of the color personality coordinates of the main colors.

4.4.2. Traditional Dwellings and Historical Relics Are in a Relatively Good Condition

In the IPA, the color performance of traditional dwellings and historical relics falls within the “maintain the status quo” quadrant. The color distribution exhibits a dual characteristic of “stable base with vibrant accents”, aligning with the cultural aesthetics of the Yangtze River Delta rural areas, which emphasize “low-key restraint as the main theme, complemented by festive vitality” (Figure 11). Traditional architectural colors are concentrated in the low-brightness, low-purity range (RGB 89, 76, 68; RGB 54, 57, 70; RGB 40, 38, 38). Among these, the blue brick walls (RGB 173, 173, 164) and original wooden frames (RGB 196, 124, 69) form a low-purity, low-brightness base, reflecting the material heritage of the “white walls and black tiles” tradition. A small portion of accent colors are distributed in the high-purity, high-brightness range, typical examples being festive lanterns (RGB 204, 108, 100) and decorations (RGB 140, 84, 36), with their area strictly controlled within 10%, adhering to the “60-30-10” color harmony principle [117]. The color strategy for the dwellings and historical relics in the three ancient towns injects vitality into daily life while maintaining historical authenticity. The dark-tone base effectively connects with the blue-gray system of the water network landscape, creating visual continuity of “land and water in harmony”. High-saturation accent colors, through positional constraints and brightness buffering, avoid disrupting the traditional atmosphere, resulting in a well-balanced living landscape effect.

Figure 11.

The Color and Color Character Coordinate Distribution of the Residential and Historical Landscape of Three Villages.

4.4.3. Signage Design and Public Art Lack Vitality

In the IPA, the color performance of signage design and public art falls within the quadrant requiring urgent improvement. The color characteristics of rural signage and public art design resemble those of the water network landscape, residential landscapes, and historical relics, with most colors concentrated in the high-purity, low-brightness, and low-purity, low-brightness ranges (RGB 39, 37, 26; RGB 127, 106, 78). Only a small number of cultural and creative artworks (RGB 204, 132, 172) and signage (RGB 209, 138, 73) evoke a warm and positive attitude among tourists (Figure 12). Most sculptures in the three ancient towns are stone carvings (RGB 158, 164, 180), with colors leaning toward steadiness. The color vibrancy of directional signs and maps is relatively low (RGB 109, 81, 78; RGB 89, 53, 38; RGB 92, 60, 68), failing to create effective visual stimulation. The alignment of IPA results with survey data reveals that such designs have not fulfilled the dual roles of guiding function and cultural expression. There is an urgent need for optimization through enhanced color contrast and strengthened regional symbols.

Figure 12.

The Color Characteristics and Coordinate Distribution of the Identity Landscape Colors of Three Villages.

From the perspective of key factors requiring improvement, the water network landscape in ecological landscapes received the highest evaluation, indicating that the three ancient towns have achieved significant success in rural ecological protection. Their plant combination methods can be applied to the construction of ecological landscapes in other rural areas. Traditional dwellings and historical relics in the living and productive landscapes showed favorable results, suggesting that the color application of traditional architecture in the three ancient towns has gained public recognition, providing valuable experience for other rural areas in the Yangtze River Delta. However, signage design and public art, despite sharing similar color schemes with architectural colors, did not achieve satisfactory outcomes. The colors of these factors failed to attract significant attention from tourists, necessitating targeted improvements in future landscape designs.

5. Discussion

The current homogenization of rural landscapes highlights the insufficient attention paid by mainstream academic research paradigms to the representation of regional culture and ecological synergy mechanisms. Based on the IPA’s identification of key factors in ecological–production–living landscapes and the empirical analysis of color geography, this study reveals the strengths and weaknesses of rural landscapes in the Yangtze River Delta in terms of ecological connectivity and seasonal color richness of farmland. The IPA results clarify the priorities for systemic ecological protection and the value transformation of productive landscapes, while color analysis quantifies the explicit pathways for expressing regional characteristics from the perspectives of visual perception and cultural representation. Building on this, the study further focuses on the internal functions of the three landscapes: the inherent fragility of ecological landscapes, the erosion of authenticity in living landscapes, and the disconnection in the value chain of productive landscapes. Subsequent discussions will center on these strengths and weaknesses, integrating landscape ecology and cultural semiotics theories to propose a targeted design framework that balances ecological resilience, cultural distinctiveness, and industrial efficiency. This provides an empirically grounded theoretical foundation for addressing the challenge of rural landscape homogenization.

5.1. Ecological Landscapes Need to Maintain Their Strengths While Fostering Innovation

This study proposes a problem-oriented design strategy based on IPA and color perception theory. In the dimension of ecological landscapes, the quadrant distribution of “overconsumption” and “secondary improvement” revealed by IPA results fundamentally reflects the ecological fragility of natural landscapes and the adaptive boundaries of human intervention. Organically formed water networks and mountain landscapes have low response thresholds to high-intensity development, while dynamic elements such as rainy season landscapes offer flexible space for design innovation. In terms of color analysis, the “evergreen base + seasonal accents” color pattern in the Yangtze River Delta rural areas is viewed as a visual mapping of regional ecology and climatic conditions. It emphasizes that color is not merely an aesthetic element but also an explicit expression of ecological adaptability. For instance, the high proportion of native plants like camphor trees is essentially a long-term adaptation to the subtropical humid climate.

The rural landscapes of the Yangtze River Delta exhibit certain advantages in ecological landscapes, which can serve as significant innovation points in landscape design. Based on the findings from the IPA, all ecological landscape metrics are positioned within the “Overexertion” and “secondary improvement” quadrants. Specifically, the development of water network landscapes, plant landscapes, mountain landscapes, and landscapes of fauna excessive effort. This outcome can be attributed to the intrinsic nature of ecological landscapes, which are formed organically and are challenging to modify through human intervention. The “temperature and humidity environment” and “rainy season landscapes” fall under “secondary improvement” initiatives. Consequently, pursuing design innovations specifically for “rainy season landscapes” is a viable option. In terms of color evaluation, ecological landscapes are characterized by vibrant and harmonious colors, primarily high-purity, low-brightness hues. This is particularly evident in the Yangtze River Delta region, where the abundance of evergreen plant species and mild climate are conducive to the growth of camphor trees, osmanthus, magnolias, and broad-leaved trees. The frequent occurrence of rainy seasons enables most plants to thrive, resulting in a landscape that remains verdant throughout the year and serves as a significant source of vibrant colors in rural settings. Large areas of vibrant colors outside the green spectrum should be avoided to prevent disrupting the aesthetic harmony of the overall ecological landscape.

Addressing the current conditions, the strategy for enhancing ecological landscapes emphasizes the adoption of a design philosophy centered on indigenous natural elements. The objective of this strategy is to showcase the distinctive regional characteristics, poetic essence, and sustainability of the rural ecological landscapes in the Yangtze River Delta, aiming to achieve an ideal harmony between humanity and nature. Ecological landscape design should prioritize water elements, creating a “water network landscape system” that embodies the geographical features of the Yangtze River Delta [118]. Bank designs should favor natural ecological forms, extensively utilizing native materials such as wooden piles, local flora, and Taihu stones to promote an environmentally friendly bank appearance. Additionally, it is essential to develop a “plant landscape” that reflects the unique attributes of the Yangtze River Delta, selecting crops and medicinal plants that align with local growth cycles and seasons, ensuring that cultivated and essential farmland remains unharmed, and incorporating native flora for aesthetic enhancement. Furthermore, by integrating the ecological philosophy of “the unity of nature and humanity,” a meticulously designed green landscape can effectively connect water systems with residential structures, fostering a poetic habitat that harmonizes human existence with nature [94]. The design should encompass the planning of rural parks, hiking paths, and landscape streams, leveraging a tree-dominated landscape arrangement to establish an ideal ecological configuration with flowing water in front of homes and dense woodlands behind, thereby achieving a harmonious unity of water, farmland, forests, lakes, and residential environments.

The above practical strategies are essentially the embodied expression of theoretical applications: water network restoration corresponds to the “patch-corridor” theory in landscape ecology, enhancing landscape connectivity through the reconstruction of continuous ecological shorelines; plant layer configuration aligns with the theory of regional color adaptation, transforming climate adaptability into recognizable color symbols; and rainy season landscape design integrates the dynamic concept of “landscape as a process”, making natural hydrological processes the core elements of landscape narratives. These design strategies provide a replicable operational paradigm for addressing the challenges of “over-intervention” and “loss of distinctiveness” in ecological landscape development. Their value extends beyond the Yangtze River Delta, offering reference significance for rural ecological landscape planning in global humid climate regions.

5.2. Living Landscapes Exhibit Typical and Representative Characteristics

After completing the systematic diagnosis and optimization strategy derivation for ecological landscapes, the research perspective shifts to the living dimension within the ecological–production–living landscapes—as the core carrier of rural socio-cultural heritage and residents’ daily experiences, the quality of residential landscapes directly influences place identity and life well-being. IPA results indicate that traditional dwellings and historical relics perform exceptionally well in the evaluation of living landscapes, highlighting the effectiveness of material cultural heritage protection in the Yangtze River Delta region. However, issues such as imbalanced color control in new constructions and insufficient visualization of intangible cultural landscapes have also been exposed. Below, we conduct targeted analysis based on the existing strengths and weaknesses of residential landscapes, integrating color semiotics theory.

The living landscape represents the most culturally distinctive feature of rural areas in the Yangtze River Delta region. It is essential to preserve its inherent state while incorporating strategic chromatic enhancements to enrich its aesthetic and cultural value. This approach not only maintains the authenticity of the rural environment but also elevates its visual appeal, ensuring a harmonious blend of tradition and modernity. Such a practice aligns with the broader goal of sustainable development, where cultural preservation and aesthetic innovation coexist to foster a resilient and vibrant rural identity.