Abstract

This study investigates how displaced women entrepreneurs in Ethiopia’s fragile institutional environment apply effectuation principles to sustain their businesses. Through analysis of five effectuation dimensions, we find that while affordable loss strategies and means orientation enhance business resilience, traditional effectuation approaches like partnership formation and rigid control mechanisms often prove ineffective in displacement contexts. This research makes three key contributions: first, it extends effectuation theory by identifying how institutional fragility fundamentally alters the utility of entrepreneurial strategies; second, it reveals displaced women’s innovative adaptations through informal networks and risk-minimising approaches; and third, it challenges universal applications of effectuation principles in crisis settings. This study contributes to sustainable entrepreneurship by demonstrating both the relevance and constraints of effectuation theory in crisis-affected environments. It underscores the importance of flexible, resourceful strategies for women entrepreneurs navigating systemic challenges, offering insights for policymakers and support organisations. Practical implications include designing capacity-building programmes that promote adaptive strategies, such as risk management and resource optimisation, while addressing the challenges of partnerships and rigid control mechanisms. By aligning with the goals of sustainable development, this research not only highlights the potential of effectuation principles but also unravels their limitations, providing a nuanced understanding of how entrepreneurial strategies can foster resilient livelihoods and sustainable economic practices in crisis-affected regions.

1. Introduction

Between 2019 and 2023, internal displacement rose sharply from 50.3 to 75.9 million people worldwide, driven largely by conflict, climate crises, and socio-political instability [1,2,3]. This ongoing crisis has severely impacted access to livelihoods, basic services, and psychological well-being [3]. By 2023, 90% of IDPs were displaced by conflict and 10% by climate-related disasters [4]. This paper is motivated by the urgent need to support displaced women entrepreneurs, who face compounded barriers. It explores how effectuation theory can illuminate the ways these women creatively leverage limited resources, navigate uncertainty, and rebuild agency through entrepreneurship.

The intensification of global conflicts, climate crises, and socio-political upheavals has led to unprecedented levels of forced displacement, with millions of individuals uprooted from their homes and livelihoods. Among these displaced populations, entrepreneurship has emerged as a vital mechanism for survival and socio-economic integration. For displaced women entrepreneurs, who often face compounded vulnerabilities due to intersectional barriers, entrepreneurial activity offers a pathway to sustain livelihoods, achieve independence, and rebuild agency. In this context, effectuation theory provides a robust conceptual framework for understanding how these individuals navigate uncertainty and resource constraints to establish and sustain businesses.

Effectuation theory, pioneered by Sarasvathy (2001) [5], fundamentally reorients entrepreneurial strategy by shifting the focus from causation—where predefined goals are pursued through optimal means—to effectuation, where entrepreneurs co-create opportunities by leveraging available resources and partnerships. The theory comprises five core principles: means orientation (EMO), affordable loss (EAL), leveraging contingencies (ECO), partnership orientation (EPO), and control orientation (EC). Each principle of effectuation offers unique insights into the entrepreneurial strategies employed by displaced populations. Means orientation (EMO) emphasises starting with existing resources such as skills, knowledge, and networks [6,7]. For displaced women, this principle underscores the importance of leveraging informal networks, cultural capital, and entrepreneurial ingenuity in the absence of formal support systems. Affordable loss (EAL) highlights the willingness to take calculated risks within acceptable limits [8], facilitating iterative learning and sustainable venture development [9,10]. This approach is crucial for entrepreneurs in displacement settings, where high uncertainty necessitates prudent risk management.

Leveraging contingencies (ECO) involves turning unexpected events into opportunities, a critical skill for navigating the rapidly shifting market conditions in displacement contexts [11]. For instance, IDWs often exhibit remarkable adaptability by pivoting their business models in response to environmental shocks or resource constraints. Partnership orientation (EPO) focuses on building strategic alliances and securing commitments from partners to reduce uncertainty [12]. Collaborations with host communities, NGOs, and diaspora networks are often central to displaced women’s entrepreneurial success. Lastly, control orientation (EC) encourages entrepreneurs to focus on controllable factors rather than attempting to predict uncertain futures [13]. This principle fosters flexibility and resilience, enabling displaced entrepreneurs to navigate instability effectively.

Research Context and Questions

While effectuation theory provides a valuable lens for understanding entrepreneurial strategies under uncertainty, its application in displacement contexts warrants critical examination. Displacement settings are characterised by systemic barriers, such as restricted access to financial systems, formal markets, and social capital, which challenge the foundational assumptions of effectuation. Critics, including Jones and Li [13,14], argue that the theory’s emphasis on short-term adaptability may impede long-term scalability and planning, particularly for marginalised groups like displaced women.

Ethiopia provides an important setting for examining these dynamics. With over 3 million internally displaced people (IDPs) as of 2023, driven by ethnic conflicts, environmental disasters, and political instability, the country represents one of the largest displacement crises globally [15]. Displaced women in Ethiopia face profound challenges, including limited access to financial resources, formal markets, and social safety nets [16,17]. Nonetheless, many of these women have turned to entrepreneurship as a means of economic survival and resilience. Their experiences provide a unique opportunity to explore how effectuation principles are operationalised in displacement contexts, particularly in low-income, resource-scarce settings.

This study addresses these theoretical and practical gaps by investigating the relationship between effectuation principles and business longevity among displaced women entrepreneurs in Ethiopia. Employing a survey of 439 displaced women entrepreneurs and analysing the data using a Generalised Linear Model (GLM), this study seeks to answer the following research questions:

- How do effectuation principles—means orientation, affordable loss, leveraging contingencies, partnership orientation, and control orientation—affect business longevity among displaced women entrepreneurs?

- How can these findings inform policy and support mechanisms to enhance the resilience and sustainability of businesses initiated by displaced women entrepreneurs?

The findings suggest that effectuation principles play a critical yet complex role in shaping business longevity in displacement contexts. Affordable loss (EAL) emerges as a significant positive predictor of sustained business operations, reaffirming its importance in managing risks and fostering iterative learning. Similarly, means orientation (EMO) demonstrates marginally significant positive effects, emphasising the value of resourcefulness and leveraging existing capabilities. In contrast, control orientation (EC) and partnership orientation (EPO) exhibit significant negative effects, raising questions about the limitations of these principles in volatile displacement settings.

This study critically contributes to the understanding of effectuation principles by highlighting their contextual limitations in the unique setting of ID women entrepreneurs in Ethiopia. While effectuation theory emphasises flexibility, leveraging contingencies, and forming partnerships [18], the findings challenge the assumed universality of these principles. The negative and significant impact of control orientation (EC) and partnership opportunities (EPO), along with the non-significance of contingency orientation, underscores how structural barriers such as inadequate legal recognition, discrimination, and marginalisation by host communities inhibit the practical application of these principles [18,19,20].

By exposing the limitations of effectuation in contexts of forced displacement, this study not only enriches theoretical discourse but also paves the way for future research to examine alternative frameworks suited to vulnerable and resource-deprived entrepreneurs. It advocates for more nuanced approaches that account for structural inequities, the lack of institutional support, and socio-cultural dynamics in such environments [21]. This contributes to advancing the discourse on entrepreneurial resilience and adaptation, providing valuable insights for policymakers and practitioners seeking to design inclusive interventions that foster sustainable entrepreneurship among displaced populations [21,22].

The paper is structured as follows: The next section reviews the literature on effectuation theory and displaced entrepreneurship, situating this study within the broader scholarly discourse. The methodology section outlines the survey design, sample characteristics, and analytical framework. The results section presents the empirical findings, followed by a discussion of their theoretical and practical implications. This paper concludes with recommendations for future research and policy interventions aimed at fostering entrepreneurial resilience in displaced populations.

2. Theoretical Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Effectuation

The effectuation approach to entrepreneurship involves flexible, adaptive, and experimental strategies for enterprising efforts based on cognitive framing of opportunities rather than rational planning [23,24,25]. Under pure uncertainty conditions, effectuation theory suggests that “decision-makers will rely on their existing means and a logic of control to activate useful ties, utilize affordable loss, and start building a new future, be it a new market, a new product, or a new organization...” [5,26]. The context of forced internal displacement provides a rich setting to examine the effects of effectuation on women’s enterprising and sustained business operation as it assumes uncertain and dynamic environments where future states are not predetermined but rather created through entrepreneurial actions [27,28,29,30]. Effectuation decision-making logic consists of five facets to address perceived uncertainty: means orientation, affordable loss, contingency orientation (flexibility), control orientation, and partnership opportunity (pre-commitments) [31,32]. This approach allows entrepreneurs to change or adapt goals given resource constraints.

The effectuation theory is particularly effective in uncertain business environments, offering a strategic management approach to navigate uncertainties and drive entrepreneurial success [33]. Research has shown that the effectuation principles have a significant impact on entrepreneurial performance [33,34,35,36]. For instance, experimentation and flexibility have been found to positively influence the competitiveness of entrepreneurs [36]. Additionally, the use of effectuation principles, such as affordable loss and leveraging contingencies, has been associated with improved venture performance [35]. Effectuation also helps entrepreneurs view uncertainty as an opportunity rather than a barrier, leading to more proactive internationalisation efforts. Read et al. [37] identified favourable associations between performance and a focus on means orientation, forming partnerships, and leveraging contingencies.

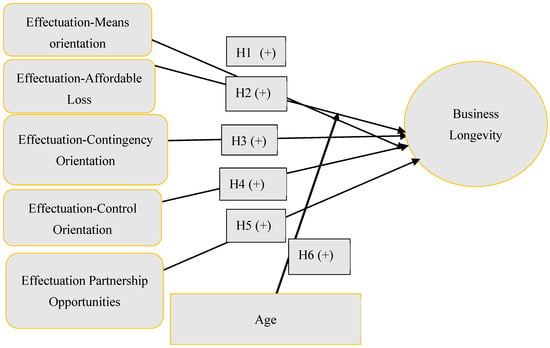

Scholars have pointed out that the context for effectuation is characterised by radical uncertainty, goal ambiguity, and environmental uniformity [38,39,40]. However, such positioning has been critiqued for its insufficient attention to social, cultural, or bounded rationality [41,42,43]. Therefore, it is important to look beyond the contextual influence on generic uncertainty and examine how other underlying mechanisms can be a source of uncertainty when entrepreneurs interact with their surroundings and other social agents [40,42]. Drawing on the contingency theory, Shirokova et al. [44] found “an effectual behavioural logic” useful under conditions of uncertainty and resource constraints in the less developed financial and cultural-cognitive institutions. Figure 1 summarises the research model.

Figure 1.

Research model.

2.2. Means Orientation

The effectuation means orientation (EMO) principle emphasises that entrepreneurs should focus on the resources currently available to them rather than chasing distant, often uncertain resources. The effectuation principle of means orientation offers insights into displacement entrepreneurship by emphasising non-predictive control strategies in resource-constrained environments. Entrepreneurs leverage their existing means (who they are, what they know, and whom they know) to exploit opportunities and acquire resources [45]. The logic is that entrepreneurs shape their venture paths based on their immediate means, rather than a pre-determined vision, adapting as they go [32]. The relationship between effectuation means orientation and firm performance has been examined in several studies. Nienhuis [46] found that means-based actions, rather than goal-based ones, positively influence performance. Furlotti [47] highlighted that means-based entrepreneurial actions improve new venture performance, especially when moderated by opportunity recognition and process control practices. Furthermore, Cowden et al. [26] revealed that entrepreneurs adjust their use of effectual decision-making based on uncertainty levels, increasing it during extreme uncertainty to ensure survival. Given that displaced entrepreneurs often face limited external support and unpredictable markets, businesses that focus on means orientation can be more resilient and adaptable. By drawing on their available resources, displacement entrepreneurs are better positioned to weather shocks and uncertainties in the market, ensuring greater business sustainability. The iterative, adaptable approach offered by EMO enables them to pivot and adjust as conditions change, which is crucial for long-term operation. Thus, the following hypothesis is advanced:

H1.

There is a positive relationship between effectuation means orientation (EMO) and the sustained operation of businesses run by displacement entrepreneurs.

2.3. Affordable Loss

Affordable loss refers to the process through which entrepreneurs assess the potential worst-case outcomes of their actions and establish the extent of loss they are willing to bear [48]. This concept encompasses various dimensions, including opportunity costs, the loss of time, attention, commitment, or financial capital. Accordingly, entrepreneurs adopt a prudent approach, ensuring that they do not commit more resources than they can reasonably afford to lose [49]. This approach is particularly relevant for entrepreneurs in uncertain environments, such as developing countries [50] and disaster recovery situations [51]. EAL encourages entrepreneurs to estimate what they can risk and determine their willingness to lose in pursuing a venture [31]. It extends beyond economic considerations to include social losses like status and reputation [8]. The principle is closely linked to other effectuation concepts like flexibility and pre-commitments [52]. While the EAL principle is generally associated with effectuation, some research suggests it may have a prevention focus, potentially negatively impacting entrepreneurial orientation [52]. Understanding and applying EAL can foster resilient entrepreneurial strategies and aid in decision-making in dynamic markets [53]. In the context of internal displacement, women entrepreneurs are often forced to operate in highly precarious conditions with limited access to resources and safety nets. The affordable loss principle allows them to start and grow businesses without exposing themselves or their families to excessive operational risk. By only investing what they can afford to lose, these women increase their chances of long-term business survival. The iterative nature of the affordable loss approach enables them to learn from small failures, recalibrate, and continue operating, which is crucial in an unpredictable and resource-scarce environment. This approach not only aligns with the experiences of displaced women but also allows them to assess opportunities in a manner that mitigates financial risks [7] while focusing on the longer-term goal of sustaining their business and supporting their families. Based on the foregoing discussion, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H2.

There is a positive relationship between effectuation affordable loss (EAL) and the sustained operation of businesses run by internally displaced women.

2.4. Contingency Orientation

The effectuation contingency orientation (ECO) principle is rooted in the idea that entrepreneurs should embrace and leverage unexpected events and changes rather than trying to avoid them [54]. Instead of planning for every possible risk, entrepreneurs operating under contingency orientation adapt their strategies dynamically in response to unforeseen circumstances, viewing surprises as opportunities to pivot and innovate. This flexibility allows them to take advantage of emerging opportunities that may arise from unexpected events, changes in the market, or environmental shifts. Refugees or displaced women often engage in necessity-driven entrepreneurship [55] due to limited employment opportunities in host countries, leveraging their innate entrepreneurial traits and adapting to new economic landscapes. The effectuation approach, which emphasises flexibility and leveraging contingencies, is particularly relevant in high-uncertainty environments like those faced by refugee entrepreneurs [56]. For IDPs, the ability to remain flexible and responsive to their new environments is vital. As they navigate the complexities of their host communities, they can capitalise on unexpected opportunities that arise, such as shifts in local demand or new partnerships with other entrepreneurs or organisations [57]. This adaptability is particularly important in conflict-affected areas, where economic conditions can change rapidly and unpredictably [58].

Displaced women entrepreneurs frequently lack access to traditional financial systems, formal training, and social networks that typically support entrepreneurial endeavours [7,59]. In such settings, a strong contingency orientation allows these women to pivot and adapt their business models swiftly to survive amidst rapid changes in their environment [10,60]. The flexible and adaptive nature of ECO makes it a powerful approach for maintaining long-term business operations, especially for entrepreneurs who cannot rely on stable market conditions or institutional support. This study proposes the following hypothesis:

H3.

There is a positive relationship between effectuation contingency orientation (ECO) and the sustained operation of businesses run by internally displaced women.

2.5. Control Orientation

The effectuation principle of control orientation is crucial for understanding displacement or refugee entrepreneurship. Effectuation emphasises control over prediction in entrepreneurial action, particularly under uncertainty [32]. Control orientation in effectuation involves flexibility, experimentation, and fluid goals [61], which can be beneficial for sustainable entrepreneurship in developing contexts [62]. Ko et al. [63] argue that the control dimension of effectuation logic encourages firms to assess their available resources and be more willing to experiment, leading to improved performance outcomes. This adaptability allows firms to pivot quickly in response to market demands, enhancing their overall performance. In the context of internal displacement, where future conditions are highly uncertain and external support is limited, control orientation offers a pathway for ID women to maintain agency over their entrepreneurial ventures. By focusing on the variables they can influence—such as leveraging local networks, adapting to immediate market needs, and maintaining flexible operational strategies—these women are more likely to sustain their businesses over time. The principle of control orientation provides a sense of empowerment and resilience, enabling ID women to continue operating their businesses despite ongoing challenges and uncertainties. By controlling the factors they can manage, they are able to continue generating income and supporting their families, which enhances the sustainability of their ventures in the long term. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4.

There is a positive relationship between effectuation control orientation (EC) and the sustained operation of businesses run by internally displaced women.

2.6. Partnership Opportunity

Internally displaced women face unique challenges in starting and maintaining businesses due to resource scarcity, limited access to capital, and the absence of supportive institutions. The effectuation principle of partnership opportunity plays a crucial role in understanding displacement and refugee entrepreneurship. Partnership opportunities become vital in these conditions because they enable ID women entrepreneurs to leverage external resources and expertise, reducing the burden of entrepreneurship in a highly volatile environment. Displaced and/or migrant entrepreneurs leverage resources from various networks to create opportunities in host country markets [64]. The comprehensive review of Harima and Freudenberg [65] highlights the critical role of partnership opportunities (EPO) as displaced and refugee entrepreneurs leverage social capital, informal networks, and local partnerships to navigate and overcome challenges in hostile business environments. By forming strong partnerships, displaced women can gain access to crucial inputs such as raw materials, financing, and customer networks, all of which contribute to sustaining their business operations [66]. Additionally, partnerships provide a mechanism for sharing risk, learning from partners, and innovating in response to market changes, enhancing the long-term viability of their ventures. Given the uncertainty and instability of displacement, partnerships allow these women to create more secure and resilient business models that are adaptable to their changing environments. Sarasvathy’s [5] foundational work on effectuation theory, along with contemporary research by Harima and Freudenberg [65], supports these claims by showing how partnership-oriented approaches enhance the flexibility and adaptability of entrepreneurs, especially in resource-constrained environments like those faced by displaced individuals. Based on the foregoing review, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H5.

There is a positive relationship between effectuation partnership opportunities (EPO) and the sustained operation of businesses run by internally displaced women.

2.7. Age of the Entrepreneurs

The age of displaced women entrepreneurs positively influences their ability to sustain business operations over time. This relationship arises from age-related factors such as accumulated experience, broader social networks, and psychological traits like resilience and adaptability, all of which enhance the effective application of entrepreneurial principles. Older entrepreneurs often possess a wealth of knowledge and expertise, enabling them to leverage effectuation principles like means orientation and strategic partnerships more effectively. Research by Khurana et al. [67] suggests that while the use of causation and effectuation logics does not statistically vary by age, experience significantly shapes how these principles are applied in practice. Additionally, older entrepreneurs typically exhibit higher entrepreneurial self-efficacy, supported by career experiences and well-established social capital, which facilitate resource acquisition and decision-making in uncertain environments [68]. Furthermore, psychological traits associated with age, such as greater resilience, enhance their capacity to navigate challenges, fostering sustained business operations [69]. In contrast, younger entrepreneurs may lack these advantages, facing barriers such as limited networks and experience, which can impact their ability to sustain ventures. Hence, this study advances the following hypothesis:

H6.

There is a positive relationship between the age of displaced women entrepreneurs and their ability to sustain business operations over a prolonged period.

3. Materials and Methods

This study was conducted in Ethiopia to explore the entrepreneurial opportunities available to internally displaced women residing in the vicinity of Addis Ababa. Collecting data from internally displaced populations presents unique challenges compared to refugees, as noted by [70]. Most African internally displaced women are engaged in informal sole trading activities such as street vending, home-based kiosks, open market spaces, and farmer markets. Consequently, considerable effort was required to locate these women and obtain their consent to participate in this research.

This study adopted a survey research strategy, using a structured questionnaire to capture the experiences, aspirations, and barriers faced by internally displaced women in accessing entrepreneurial opportunities. Stratified sampling was employed based on geographic strata, defined by three towns surrounding Addis Ababa: Koye Feche, Burayu, and Sululta. A comprehensive register of displaced women operating microenterprises in each location served as the sampling frame. Proportional allocation was used to draw the sample: 217 women from Koye Feche, 190 from Burayu, and 233 from Sululta. Of these, valid responses were received from 149, 130, and 160 women, respectively. This approach aligns with standard stratified sampling techniques aimed at ensuring representativeness across the three towns [71]. This paper presents findings from the survey component of a broader mixed-methods study involving 439 displaced women. While the overall study also included qualitative interviews with purposively selected internally displaced (ID) women, this analysis focuses on the survey data. To enhance the reliability of responses and mitigate social desirability bias, the survey employed anonymity, indirect interviewer-administered questionnaires, and trust-building strategies [72].

The survey questionnaires were meticulously translated into local languages to enhance comprehension and then cross-checked back to English to maintain accuracy and reliability. The data collection instrument included a five-point Likert scale to measure perceptions of entrepreneurial opportunity identification, ranging from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (5). To operationalise the construct of effectuation, 20 validated measurement items were used, following the frameworks established by Chandler et al. [23] and Frese et al. [73]. These measures encompass dimensions of effectuation such as means orientation, affordable loss, contingency orientation, control orientation, and partnership opportunities. The dependent variable—years of business operation—is ordinal, measured on a five-point scale, by years of operation, ranging from less than a year to over ten years, with longer operation times signifying greater business resilience and sustainability. While an ordinal logistic model was initially applied, it showed poor fit. A Generalised Linear Model (GLM) with ordinal logit specification was used instead [74], meeting model assumptions and improving performance.

The survey was conducted face-to-face by four trained research assistants between May and July 2022 in three towns surrounding Addis Ababa—Burayu, Sululta, and Koye Feche—where many IDPs had been relocated. Face-to-face data collection was advantageous in this displacement context, enabling rapport building [75], clarifying questions, and including participants with limited literacy or digital access, thereby enhancing data quality and participation, especially among vulnerable groups [76].

Data coding and analysis were conducted using SPSS Version 28. Descriptive statistics were calculated to summarise the data, and reliability analysis was performed to assess the internal consistency of the effectuation constructs. Cronbach’s Alpha for the effectuation scale was 0.886, exceeding the benchmark of 0.7, indicating strong reliability.

Construct Reliability and Validity

Table 1 reports the standardised factor loadings, Composite Reliability (CR), Average Variance Extracted (AVE), and Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) for each construct associated with the five core effectuation principles: means orientation, affordable loss, contingency orientation, control orientation, and partnership opportunities. All constructs exhibit strong internal consistency, with CR and Cronbach’s Alpha values exceeding the commonly recommended threshold of 0.70 [77], indicating reliable measurement. AVE values for all constructs are above the 0.50 benchmark, demonstrating acceptable convergent validity. The factor loadings of all indicators are statistically significant (p < 0.001) and above 0.60, providing support for item reliability.

Table 1.

Factor loadings, CR, AVE, and Cronbach’s Alpha.

To improve model fit and reliability, the affordable loss construct was refined by retaining only two items with the strongest loadings. Likewise, ECO3 and ECO4 were removed from the contingency orientation construct for similar reasons. Despite the item reduction, both constructs maintained acceptable reliability and validity metrics, supporting their continued inclusion in the measurement model.

Overall, the measurement model supports the reliability and validity of the constructs representing the effectuation principles, confirming their suitability for further analysis and theoretical application.

To examine the relationship between effectuation principles, age, and business sustainability, a Generalised Linear Model (GLM) with ordinal logit regression was employed. This method was chosen due to the ordinal nature of the dependent variable, “Years in operation”, allowing for robust analysis of the odds of sustained business and to account for the heterogeneity of respondents. Independent variables included aggregated constructs of effectuation principles: AggEMO (means orientation), AggEAL (affordable loss), AggECO (contingency orientation), AggEC (control orientation), and AggEPO (partnership opportunities). The respondent’s age, household role, number of children, and sector were included as control variables to assess their moderating effect on the relationship between effectuation principles and business sustainability.

The specified GLM Ordinal Logistic Regression model is expressed as follows:

where

Log[P(Y ≤ j)/(1 − P(Y ≤ j) = β0(j) + β1AggEMO + β2AggEAL + β3AggECO + β4AggEC + β5AggEPO + β6Age

P(Y ≤ j): The cumulative probability of the dependent variable Y being in category j or lower.

β0(j): The threshold (intercept) for the j-th category. There will be J − 1 thresholds (where J is the number of categories of Y).

β1, β2, β3, β4, β5, β6: The coefficients for the independent variables (AggEMO, AggEAL, AggECO, AggEC, AggEPO, age) explain their influence on the sustainability outcome.

The proportional odds assumption implies that the coefficients β1, β2, β3, β4, β5, and β6 are the same across all categories of Y.

The model fit was assessed using various statistical tests to ensure the validity and robustness of the results (Table 2). The Omnibus Test (likelihood ratio test) yielded a significant result (χ2 = 83.025, p < 0.001), indicating that the specified model provided a significantly better fit than the null model. Goodness-of-fit measures, including deviance (Deviance/df = 0.600) and Pearson Chi-Square (Pearson/df = 0.982), suggested an adequate model fit. Furthermore, the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC = 1029.395) provided a baseline for model comparison, with lower values indicating better fit.

Table 2.

Model fit indicators.

The multicollinearity diagnostic test indicates no multicollinearity in the independent variables used (see the estimated test statistics in Table 3). Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs) were below the critical threshold of 10 (e.g., AggECO = 1.988, AggEAL = 1.151), while tolerance values exceeded 0.1 (e.g., AggECO = 0.503, AggEAL = 0.869), indicating no multicollinearity concerns. These test statistics support the appropriateness of the inclusion of these independent variables in the model.

Table 3.

Multicollinearity diagnostics.

These measures collectively validate that the GLM with ordinal logit regression is statistically robust and suitable for exploring the effect of effectuation principles on business sustainability in this study. We have chosen a baseline model with the lowest Akaike Information Criterion by estimating the impacts of the explanatory variables mostly used in the literature.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Sociodemographic Profile

The demographic profile of the study participants reveals significant insights into the key characteristics of the internally displaced women in Ethiopia (see Table 4). A majority of the respondents (55.6%) are aged 20–29 years, with 32.6% aged 30–39 years, indicating a predominantly young and potentially energetic workforce. However, the lower representation of women aged 40 years and above (9.5%) may suggest that older women face barriers to entrepreneurial participation, such as physical limitations or societal expectations, which could limit the diversity of experience within the entrepreneurial landscape.

Table 4.

Sociodemographic status of study households.

Educational attainment is a critical factor influencing entrepreneurial capability, with 68.2% of respondents having no formal education or only a primary-level education. This limited educational background may constrain the respondents’ ability to access formal business opportunities, navigate regulations, or adopt innovative practices. Conversely, it highlights the potential for training programmes targeting basic business and financial skills to empower these women entrepreneurs.

Marital and household roles also provide crucial implications. A majority (76.8%) are traditionally or religiously married, with 77% identifying as wives/partners in their households, suggesting that their entrepreneurial efforts are likely driven by family needs. The significant proportion of respondents managing households with three or more children (55%) underscores the necessity for flexible business models that accommodate caregiving responsibilities. These findings emphasise the importance of addressing educational and resource gaps, tailoring interventions to support young and family-centred entrepreneurs, and creating inclusive opportunities for older women.

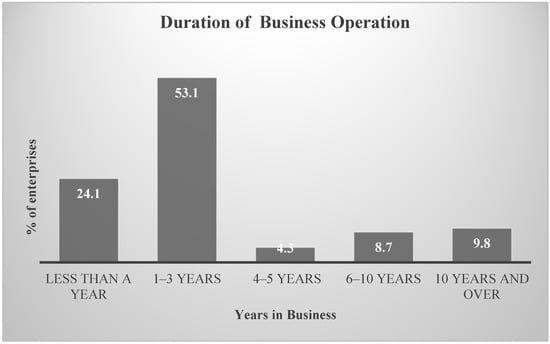

The data indicates that while many internally displaced women in Ethiopia may have had prior business experience, their current businesses have only been operating for a relatively short period since relocation (see Figure 2). Specifically, 53.1% have operated their current businesses for 1–3 years, and 24.1% for less than a year, while only 22.8% have continued for four years or more. This suggests that most are re-establishing or adapting their entrepreneurial activities in new localities following displacement.

Figure 2.

Business longevity.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics: Opportunities for Enterprising

Table 5 presents descriptive statistics for the application of effectuation principles by internally displaced women entrepreneurs in Ethiopia. Among the five dimensions, means orientation (EMO) exhibited the highest adherence, with respondents strongly agreeing on leveraging personal knowledge (M = 1.54, SD = 0.698), motivation (M = 1.97, SD = 0.935), and competencies (M = 1.92, SD = 1.032). This reflects a strong reliance on existing resources to navigate entrepreneurial challenges. Affordable loss (EAL), on the other hand, demonstrated moderate agreement, with the highest mean (M = 3.08, SD = 1.321) indicating cautious investments to avoid financial ruin. These results suggest a pragmatic approach to managing risks amidst uncertainty.

Table 5.

Effectuation in enterprising opportunities.

The other dimensions showed more variability. Contingency orientation (ECO) highlighted adaptability in acting on surprises (M = 2.01, SD = 0.908) and exploiting contingencies to some extent (M = 2.15, SD = 0.941). The displaced women entrepreneurs showed moderate agreement with effectuation control orientation behaviours, with mean scores ranging from 2.16 to 2.36 on a 5-point Likert scale. The strongest agreement was with influencing trends (M = 2.16, SD = 0.969), while the least agreement was with co-creating future markets (M = 2.36, SD = 1.100), suggesting a more individual and reactive approach to shaping business environments rather than collaborative or future-focused strategies. Lastly, partnership opportunities (EPO) had the lowest adherence, with high mean values indicating limited engagement with partners early in the business process (M = 3.03, SD = 1.291). This suggests potential constraints in accessing networks or forming collaborations. Overall, the findings reveal strong reliance on internal resources, cautious risk-taking, and moderate adaptability, while partnerships remain an underutilised strategy.

4.3. Generalised Linear Logistics Mode Results and Hypothesis Testing

This section presents the results of the Generalised Linear Model ordinal logistics regression (GLM) analysis and the hypothesis testing conducted to examine the relationship between various effectuation principles and the sustained operation of businesses run by displaced women entrepreneurs. The findings are reported using parameter estimates, significance levels, and odds ratios, providing insights into the extent to which the advanced hypotheses were supported (Table 6).

Table 6.

Generalised linear logit regression results.

4.3.1. Age Matters for Business Sustained Operation

The estimated mean of the parameter for the impact for respondent’s age is B(age) = 0.269 with the p-value = 0.026, and the exponentiated parameter is exp(0.269) = 1.309, which implies that as the respondents become older, on average, the odds of moving into a higher category of business sustainability increase by around 1.3 times with each age year (see Table 6). This suggests that older women, possibly those with more life experience, are better able to navigate the uncertainties of displacement and sustain their businesses over time. When seen in the lens of effectuation, age may correlate with a higher propensity for using pre-existing means—such as social capital, skills, or knowledge—more effectively; as effectuation theory suggests, entrepreneurs leverage their available means rather than waiting for ideal conditions.

As businesses move into longer duration categories, the odds ratios increase significantly, indicating that businesses are increasingly stable the longer they remain in operation. The largest portion of businesses (52.1%) fall into the “1–3 years” category, with odds 2.6 (Exp(B) = 2.627) times higher than for businesses lasting less than a year. However, businesses that survive beyond 3 years see a substantial improvement in stability, as indicated by much higher odds ratios for the 4–5 years, (Exp(B) = 3.649), “6–10 years, (Exp(B) = 8.593)”, and “10 years and over” categories, with odds increasing up to 8.6 times. The p-values further indicate the strength of these associations, with the 1–3-year threshold being marginally significant, while the other categories show strong statistical significance.

While our study focuses on operational longevity as a resilience proxy, we acknowledge its limitations in forced displacement contexts, where social capital (e.g., trust, networks) often plays a critical role [78]. Though not analysed here, our dataset captures preliminary social capital indicators (e.g., community connections), offering a foundation for future research. We clarify this as a boundary condition but argue that our findings remain valuable for understanding institutional persistence in non-conflict settings, while highlighting the need for complementary metrics in crisis scenarios. In addition, our analysis included age, education, marital status, number of children, and business sector as controls, based on their established relevance in livelihood resilience literature [79]. While age and the domestic services sector showed significant effects (p < 0.01), other controls were non-significant and excluded from final models to maintain parsimony [80].

4.3.2. Effectuation Affordable

The positive and highly significant coefficient for affordable loss (AggEAL) (B = 0.571, p < 0.001) indicates that as affordable loss increases, the likelihood of longer business durations rises significantly. The odds ratio (Exp(B) = 1.770) suggests that for every one-unit increase in affordable loss, the odds of displaced women being in a higher business duration category increase by 77%, holding other factors constant. This highlights the importance of financial resilience and risk management in sustaining business operations over time. This result is consistent with effectuation theory, where entrepreneurs assess and limit potential downsides (rather than maximising returns), particularly in uncertain environments like displacement contexts. This result indicates that in volatile settings, such as those faced by displaced people, focusing on affordable loss can be critical for survival. Displaced entrepreneurs often operate with limited resources, so risk-averse strategies—ensuring they do not lose more than they can afford—become key to longevity. This aligns with research that highlights the importance of survival strategies and resilience in displacement contexts [59,65]. The principles of affordable loss and leveraging means thus foster resource-based, iterative decision-making [50] and allow firms to innovate and adapt their offerings to local market conditions [81].

4.3.3. Effectuation Means Orientation

The positive coefficient for means orientation (AggEMO), B = 0.302, (0.05 < p < 0.10), suggests a marginally significant relationship with longer business durations. While not highly significant, the result indicates that as means orientation increases, there is a tendency for firms to operate for longer periods. The odds ratio (Exp(B) = 1.353) implies that for every one-unit increase in means orientation, the odds of being in a higher business duration category increase by approximately 35.3%, holding other factors constant. This hints at the potential role of resourcefulness and leveraging available means in contributing to business longevity, though further investigation may be needed to confirm this relationship. This is consistent with the effectuation principle of using what you have to create opportunities, as displaced entrepreneurs often have to make do with limited resources. Migrant and refugee entrepreneurship literature [82] emphasises that entrepreneurs in these contexts rely heavily on social capital, personal skills, and informal networks to establish and sustain businesses. The findings highlight the value of means orientation in helping displaced individuals adapt and thrive under constrained conditions.

4.3.4. Effectuation Contingency Orientation

The non-significant coefficient for contingency orientation (AggECO), B = −0.232, p = 0.213, indicates no meaningful relationship with business duration. The odds ratio (Exp(B) = 0.793) suggests a slight tendency for higher contingency orientation to reduce the odds of longer business durations by 20.7%, but this effect is not statistically reliable. Thus, contingency orientation does not significantly influence business longevity in this analysis. While effectuation emphasises flexibility and exploiting contingencies, displaced entrepreneurs might face structural challenges (e.g., legal barriers, movement barriers, limited access to markets or financing) that limit their ability to seize unexpected opportunities. Further, the institutional voids and uncertain environments in displacement contexts may restrict their ability to act on contingencies, aligning with literature that highlights such barriers, e.g., [59,83].

4.3.5. Effectuation Control Orientation

The negative and statistically significant coefficient for control orientation (AggEC) (B = −0.425, p = 0.008) indicates a significant relationship with shorter business durations. The odds ratio (Exp(B) = 0.654) suggests that for every one-unit increase in control orientation, the odds of being in a higher business duration category decrease by approximately 34.6%, holding other factors constant. This implies that rigid, control-oriented strategies may hinder business longevity, particularly in dynamic or uncertain environments. This is because displaced entrepreneurs face environments with extreme volatility and unpredictability, where attempts to control outcomes may backfire. This finding aligns with the work of Shepherd and Williams [84], who emphasise that displaced entrepreneurs in crisis-affected, resource-constrained environments often face unpredictable challenges that require flexibility and adaptability. Shepherd and Williams [84] argue that rigid control mechanisms can limit an entrepreneur’s ability to pivot or innovate in response to changing circumstances, such as shifting markets, scarce resources, or unstable conditions. Research on refugee and migrant entrepreneurship often points out that flexibility and adaptation are more critical than control [65]. In effectuation, entrepreneurs should embrace uncertainty rather than attempting to control it—this seems particularly relevant for displaced entrepreneurs, where control is often impossible due to external factors like government policies or economic instability.

4.3.6. Effectuation Partnership Orientation

The significant and negative coefficient for partnership opportunities (AggEPO) (AggEPO, B = −0.604, p < 0.001) indicates that a greater focus on partnership opportunities is associated with shorter business durations. The odds ratio (Exp(B) = 0.546 suggests that for every one-unit increase in partnership orientation, the odds of being in a higher business duration category decrease by approximately 45.4%, holding other factors constant. This implies that pursuing partnership opportunities may, in this context, hinder business longevity. This finding can be interpreted in light of Shepherd and Williams [84], who highlight the complexities of collaboration in crisis-affected and resource-constrained environments. While partnerships can provide access to resources and networks, they may also introduce dependencies, conflicts, or inefficiencies, particularly in unstable settings. Furthermore, in displacement contexts, partnerships might be more difficult to establish or sustain due to trust issues, legal constraints, or discrimination [85,86]. Displaced entrepreneurs might struggle to form stable partnerships in environments where their legitimacy or legal status is questioned [87]. Further, the absence of social connections can hinder their ability to identify and engage with potential partners, which is critical for entrepreneurial success [88]. They may thus rely more on close-knit social networks rather than broader partnerships, reflecting the importance of bonding social capital over bridging social capital [59].

5. Discussion, Conclusions, and Implications

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

This study critically examines the applicability of effectuation theory in fragile institutional environments characterised by displacement and economic instability. By testing core effectuation principles—affordable loss, means orientation, control orientation, contingency orientation, and partnership opportunities —this study uncovers both alignment and tension with existing literature, offering nuanced theoretical advancements.

5.2. Affordable Loss as a Survival Mechanism

Our findings confirm that affordable loss remains a critical strategy for entrepreneurs in displacement contexts, supporting Sarasvathy’s [5] foundational argument that uncertainty drives risk-minimising behaviour. However, while effectuation theory frames affordable loss as a strategic choice, our study reveals that displaced women entrepreneurs adopt it out of necessity rather than opportunity [89]. This aligns with Dew et al.’s [31] observation that extreme uncertainty amplifies effectual logic but challenges the assumption of deliberate entrepreneurial agency. The ways in which the effectuation logic manifested in the study context may reflect human tendencies to use safety-seeking heuristics under increasing uncertainty, which may act as potential constraints to the full use of effectuation logic due to the unaffordability of the perceived loss [11]. In displacement contexts, affordable loss is thus less a calculated heuristic and more an imposed survival tactic, suggesting a need to reconceptualise this principle in crisis settings.

5.3. Means Orientation: Resourcefulness Amid Scarcity

Our study highlights that means orientation—leveraging existing resources—plays a marginal but notable role in displacement entrepreneurship. This aligns with bricolage theory [90], demonstrating that displaced entrepreneurs “make do” with limited means. However, unlike traditional effectuation logic, which assumes entrepreneurs actively shape opportunities, our findings suggest that in fragile contexts, means-driven actions are often reactive rather than strategic [91]. This reinforces the idea that effectuation principles manifest differently under extreme constraints, requiring a revised theoretical framework that accounts for compromised agency.

5.4. The Limits of Contingency Adaptability

Effectuation theory celebrates flexibility, arguing that entrepreneurs should leverage contingencies [92]. Yet our study finds that contingency orientation has no significant impact in displacement contexts. This supports Fisher’s [24] contention that excessive adaptability can lead to decision paralysis in hyper-volatile environments. When institutional conditions shift unpredictably, displaced entrepreneurs may abandon contingency planning altogether, resorting instead to heuristic, instinctive decision-making. This finding questions the universality of effectuation’s adaptability principle and calls for a more context-sensitive understanding of entrepreneurial resilience.

5.5. The Paradox of Control Orientation

Effectuation theory posits that entrepreneurs exert control to navigate uncertainty [5]. However, our findings reveal that control orientation is counterproductive in fragile institutional environments. This contradicts conventional effectuation wisdom but supports Arend et al.’s [41] argument that in highly unstable settings, rigid control strategies fail because external conditions are too volatile to manage. Displaced entrepreneurs, instead of seeking control, often abandon long-term planning altogether, relying instead on reactive, short-term adaptations. This finding necessitates a refinement of effectuation’s control principle, recognising that its utility diminishes as institutional instability increases.

5.6. Partnerships as a Double-Edged Sword

While effectuation theory emphasises partnerships as a key resource mobilisation strategy [37], our study finds that in displacement economies, partnerships often introduce vulnerabilities rather than stability. This aligns with Webb et al.’s [93] research in conflict zones, where alliances can lead to exploitation or distrust. Institutional fragility erodes the trust needed for effective collaborations, forcing entrepreneurs to rely on tight-knit, informal networks rather than formal partnerships [65]. This challenges effectuation’s universal endorsement of partnerships and suggests that in fragile contexts, bonding social capital (strong ties within displaced communities) may be more valuable than bridging social capital (external alliances).

Collectively, these findings advance effectuation theory by delineating its boundary conditions in fragile contexts [50], demonstrating how institutional voids fundamentally reconfigure the utility of partnerships, control, and adaptability [94], and bridging effectuation with vulnerability studies to reveal that displaced entrepreneurs’ strategies emerge from compromised agency rather than purely effectual reasoning [65]. This synthesis points toward a “fragility-contingent effectuation” framework that acknowledges institutional fragility not merely as a contextual factor but as a constitutive force reshaping entrepreneurial decision-making, where traditional effectuation principles may be maintained, modified, or abandoned depending on the severity of environmental instability, thereby offering a more nuanced theoretical lens for understanding entrepreneurship in extreme uncertainty.

5.7. Policy and Practical Implications

This study’s findings have critical implications for policymakers, development agencies, and practitioners supporting displaced entrepreneurs in fragile institutional contexts. First, traditional entrepreneurship training programmes—often designed for stable-market environments—require fundamental restructuring to align with the realities of displacement economies. Our research suggests these initiatives should prioritise affordable loss strategies through microinsurance or risk-sharing mechanisms [95], while avoiding overemphasis on formal partnerships that may prove ineffective or even harmful in fragile settings. Instead, interventions should focus on strengthening informal networks within displaced communities [96], which often serve as more reliable support systems than external alliances.

Second, this study underscores the urgent need to address structural barriers that constrain displaced women entrepreneurs. The negative impacts observed for both control orientation and partnership strategies highlight the necessity for legal reforms to simplify business registration processes [19] and financial inclusion initiatives tailored to entrepreneurs who typically lack conventional collateral [70]. Additionally, given the psychological toll of operating in extreme uncertainty, psychosocial support mechanisms should be integrated into entrepreneurial programmes to help prevent decision paralysis [97].

Finally, policymakers must recognise and leverage the role of informal institutions in displacement contexts where formal systems are weak or exclusionary. This includes supporting informal savings groups that displaced entrepreneurs already rely upon [98], facilitating community-based trust-building initiatives to mitigate partnership risks [99], and developing hybrid assistance models that thoughtfully blend effectuation principles with locally adaptive strategies [100]. These approaches acknowledge both the constraints and innovative adaptations that characterise entrepreneurship in fragile environments, moving beyond conventional frameworks to create more effective support systems for displaced business owners.

5.8. Research Limitations and Future Directions

While this study provides valuable insights into effectuation in fragile contexts, several limitations must be acknowledged when interpreting the findings. The focus on a single displacement economy (Ethiopia) raises questions about generalisability to other regions experiencing different forms of displacement (e.g., conflict versus climate-induced), suggesting the need for comparative studies across diverse crisis settings [89]. Additionally, our measures of entrepreneurial resilience may not fully capture the dynamic survival strategies employed in crisis contexts [101,102], pointing to the value of mixed-methods approaches that combine quantitative analysis with qualitative assessments of social capital and community networks [103], and longitudinal studies tracking entrepreneurial adaptations to prolonged instability [104].

These limitations reveal several critical directions for future research. First, there is an urgent need to refine effectuation’s core constructs through operational definitions that account for varying degrees of institutional fragility, addressing current conceptual ambiguities while maintaining theoretical generalisability. Second, studies should examine dynamic institutional interactions, exploring how effectuation strategies evolve alongside fluctuating instability levels and potentially developing stage models of entrepreneurial adaptation. Third, research must investigate alternative resource mobilisation strategies, particularly how entrepreneurs compensate for disrupted networks through informal institutions and improvised solutions not currently captured by effectuation theory [90]. Fourth, given our findings about the limited role of orientation, future work should explore cognitive adaptations and decision-making heuristics unique to high-uncertainty contexts.

Moving beyond pure effectuation theory, future studies should integrate complementary theoretical lenses to better explain entrepreneurial behaviours in fragile environments. Combining effectuation with institutional theory [105] would better account for structural constraints, while linkages with bricolage theory could illuminate displaced entrepreneurs’ reliance on improvisation. Together, these directions would advance a more nuanced understanding of entrepreneurship in displacement contexts while developing practical frameworks to support vulnerable business owners navigating extreme uncertainty.

5.9. Conclusions

This study challenges the universal applicability of effectuation theory, demonstrating that its principles operate differently—and sometimes counterproductively—in fragile institutional environments. While affordable loss and means orientation remain relevant, control orientation, partnerships, and contingency adaptability often fail in displacement contexts, calling for a contextualised revision of effectuation theory that integrates institutional fragility as a core moderator rather than a peripheral condition. Such a reconceptualisation must account for how informal networks [99], trust deficits [106], and crisis-induced cognitive heuristics [11] fundamentally reshape effectual logics in displacement economies. These findings not only demand hybrid entrepreneurial frameworks that bridge effectuation with vulnerability studies, bricolage, and institutional theory but also underscore for policymakers the need for tailored interventions addressing structural barriers while leveraging informal resilience mechanisms. Ultimately, this integrated approach will enable both scholars and practitioners to better support displaced entrepreneurs navigating the extreme uncertainties of fragile economies.

Funding

This research received funding from the British Academy Grant ID: TGC\200186.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the study was approved by the BAL Faculty Research Ethics Committee (REF 473014) on 26 April 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

This research adheres to all the research ethics principles. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bellizzi, S. The health of internally displaced people (IDPs), between conflicts and the increasing role of climate change. J. Travel Med. 2025, 32, taae151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yigzaw, G.S.; Abitew, E.B. Causes and impacts of internal displacement in Ethiopia. Afr. J. Soc. Work. 2019, 9, 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Tesfaw, T.A. Internal displacement in Ethiopia: A scoping review of its causes, trends and consequences. J. Intern. Displac. 2022, 12, 2–31. [Google Scholar]

- IDMC. Conflicts Drive New Record of 75.9 Million People Living in Internal Displacement. 14 May 2024. Available online: https://www.internal-displacement.org/news/conflicts-drive-new-record-of-759-million-people-living-in-internal-displacement/ (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Sarasvathy, S.D. Causation and effectuation: Toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 243–263. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Dajani, H.; Marlow, S. Empowerment and Entrepreneurship: A Theoretical Framework. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2013, 19, 503–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasvathy, S.; Kumar, K.; York, J.G.; Bhagavatula, S. An effectual approach to international entrepreneurship: Overlaps, challenges, and provocative possibilities. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, E.M.; Domenico, M.D.; Sharma, S. Effectuation and home-based online business entrepreneurs. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2015, 33, 799–823. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Liu, L.; Chen, Q. The Effectiveness of Effectuation: A Meta-Analysis on Contextual Factors. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2021, 27, 777–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Luo, B.; Sun, Y. How can entrepreneurs achieve success in chaos? the effects of entrepreneurs’ effectuation on new venture performance in China. Kybernetes 2020, 49, 1407–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, D.C.; Ryman, J.A.; Makani, J. Effectuation, Innovation and Performance in SMEs: An Empirical Study. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2016, 19, 214–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idemudia Ebegbetale, C. Effectuation and causation decision making logics of managing uncertainty and competitiveness by Nigerian retail business entrepreneurs. Facta Univ. Econ. Organ. 2021, 18, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renton, M.; Simmonds, H. Effectuation and morphogenesis in the new Zealand fairtrade marketing system. J. Macromarketing 2019, 39, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, O.; Li, H. Effectual entrepreneuring: Sensemaking in a family-based start-up. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2017, 29, 467–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDMC. Global Report on Internal Displacement 2023; Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Beriso, B.S. Determinants of economic achievement for women entrepreneurs in Ethiopia. J. Innov. Entrep. 2021, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudeta, K.H.; van Engen, M.L. Work-life boundary management styles of women entrepreneurs in Ethiopia—“Choice” or imposition? J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2018, 25, 368–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Sha, Y.; Yang, K. The Impact of Decision-Making Styles (Effectuation Logic and Causation Logic) on Firm Performance: A Meta-Analysis. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2023, 38, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onuh, E.M. Assessment of the role of government in addressing the challenges of internally displaced persons in Abuja, Nigeria camps. Afr. J. Soc. Issues 2023, 5, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voznyak, H.; Mulska, O.; Druhov, O.; Patytska, K.; Tymechko, I. Internal Migration During the War in Ukraine: Recent Challenges and Problems. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2023, 21, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendra-Pons, P.; Belarbi-Muñoz, S.; Garzón, D.; Mas-Tur, A. Cross-country differences in drivers of female necessity entrepreneurship. Serv. Bus. Int. J. 2022, 16, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, J.; Kohn, K.; Miller, D.; Ullrich, K. Necessity entrepreneurship and competitive strategy. Small Bus. Econ. 2022, 44, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, G.N.; DeTienne, D.R.; McKelvie, A.; Mumford, T.V. Causation and effectuation processes: A validation study. J. Bus. Ventur 2011, 26, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, G. Effectuation, causation, and bricolage: A behavioral comparison of emerging theories in entrepreneurship research. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2012, 36, 1019–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, S.; Sarasvathy, S.D. Knowing what to do and doing what you know: Effectuation as a form of entrepreneurial expertise. J. Priv. Equity 2005, 9, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowden, B.; Karami, M.; Tang, J.; Ye, W.; Adomako, S. The spectrum of perceived uncertainty and entrepreneurial orientation: Impacts on effectuation. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2024, 62, 381–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Tornikoski, E.T. Perceived uncertainty and behavioral logic: Temporality and unanticipated consequences in the new venture creation process. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, S.; Sarasvathy, S.D.; Dew, N.; Wiltbank, R. Response to Arend, Sarooghi, and Burkemper (2015): Cocreating effectual entrepreneurship research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2016, 41, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, B.; Heydenrych, J. Technology Orientation and Effectuation—Links to Firm Performance in the Renewable Energy Sector of South Africa. S. Afr. J. Ind. Eng. 2015, 26, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welter, C.; Kim, S. Effectuation under risk and uncertainty: A simulation model. J. Bus. Ventur. 2018, 33, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dew, N.; Read, S.; Sarasvathy, S.D.; Wiltbank, R. Effectual versus predictive logics in entrepreneurial decision-making: Differences between experts and novices. J. Bus. Ventur. 2009, 24, 287–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasvathy, S.D. Effectuation. In Effectuation: Elements of Entrepreneurial Expertise; Anonymous Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Aggrey, O.K.; Djan, A.K.; Antoh, N.A.D.; Tettey, L.N. “Dodging the Bullet”: Are Effectual Managers Better off in a Crisis? A Case of Ghanaian Agricultural SMEs. J. Enterprising Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2021, 15, 755–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyana, S.M.; Masurel, E.; Paas, L.J. Causation and Effectuation Behaviour of Ethiopian Entrepreneurs: Implications on Performance of Small Tourism Firms. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2018, 25, 791–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fath, B.P.; Fiedler, A.; Whittaker, D.H. Overcoming the liability of outsidership in institutional voids: Trust, emerging goals, and learning about opportunities. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2017, 35, 262–284. [Google Scholar]

- Smolka, K.M.; Verheul, I.; Burmeister–Lamp, K.; Heugens, P.P. Get it together! synergistic effects of causal and effectual decision–making logics on venture performance. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2018, 42, 571–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, S.; Song, M.; Smit, W. A meta-analytic review of effectuation and venture performance. J. Bus. Ventur. 2009, 24, 573–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galkina, T.; Atkova, I. Effectual networks as complex adaptive systems: Exploring dynamic and structural factors of emergence. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2020, 44, 964–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grégoire, D.A.; Cherchem, N. A structured literature review and suggestions for future effectuation research. Small Bus. Econ. 2020, 54, 621–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitching, J.; Rouse, J. Contesting effectuation theory: Why it does not explain new venture creation. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2020, 38, 515–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arend, R.J.; Saroogh, H.; Burkemper, A. Effectuation as ineffectual? applying the 3e theory-assessment framework to a proposed new theory of entrepreneurship. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2015, 40, 630–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welter, C.; Mauer, R.; Wuebker, R.J. Bridging behavioral models and theoretical concepts: Effectuation and bricolage in the opportunity creation framework. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2016, 10, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Tao, Y.; Tao, X.; Xia, F.; Li, Y. Managing uncertainty in emerging economies: The interaction effects between causation and effectuation on firm performance. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 135, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirokova, G.; Morris, M.H.; Laskovaia, A.; Micelotta, E. Effectuation and causation, firm performance, and the impact of institutions: A multi-country moderation analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 129, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacho, F. The effect of effectuation principles on opportunity exploitation by entrepreneurs in a developing economy. J. Dev. Entrep. 2022, 27, 2250022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nienhuis, M.D. Effectuation and Causation: The Effect of Entrepreneurial Logic on Incubated Start-Up Performance: The Predictive Value of Effectuation in Business Plans. Master’s Thesis, University of Twente, Twente, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Furlotti, M.; Podoynitsyna, K.; Mauer, R. Means versus goals at the starting line: Performance and conditions of effectiveness of entrepreneurial action. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2020, 58, 333–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinic, I.; Sarasvathy, S.D.; Forza, C. ‘Expect the unexpected’: Implications of effectual logic on the internationalization process. Int. Bus. Rev. 2014, 23, 635–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenk, S.; Lüttgens, D.; Diener, K.; Piller, F. Learning from failures in business model innovation: Solving decision-making logic conflicts through intrapreneurial effectuation. J. Bus. Econ. Z. Für Betriebswirtschaft 2019, 89, 1097–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.M.; Ali, M.M.; Umer, L.S. Examining effectuation theory: Lessons for entrepreneurial activity in developing countries. Rev. Econ. Dev. Stud. Online 2021, 7, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monllor, J.; Pavez, I.; Pareti, S. Understanding Informal Volunteer Behavior for Fast and Resilient Disaster Recovery: An Application of Entrepreneurial Effectuation Theory. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2020, 29, 575–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmié, M.; Huerzeler, P.; Grichnik, D.; Gassmann, O.; Keupp, M.M. Some principles are more equal than others: Promotion- versus prevention-focused effectuation principles and their disparate relationships with entrepreneurial orientation. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2019, 13, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, S.; de Vasconcellos, S. Exploring the affordable loss principle: A systematic literature review. Internext Rev. Electrôn. Neg. Int. ESPM 2024, 19, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippi, S.; Kabous, L.; Hinz, A. Effectuation and lean startup in Swiss start-ups: An integrative analysis. In Proceedings of the ECIE 2023 18th European Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Porto, Portugal, 21–22 September 2023; pp. 730–738. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, W.M.; Bansal, S.; Kumar, S.; Singh, S.; Nangia, P. Necessity entrepreneurship: A journey from unemployment to self-employment. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 2024, 43, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherbib, J. Exploring the interplay between entrepreneurial orientation, causation and effectuation under unexpected COVID-19 uncertainty: Insights from large french banks. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 200, 123090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prijadi, R.; Santoso, A.S.; Balqiah, T.E.; Jung, H.; Desiana, P.M.; Wulandari, P. Does Effectuation Make Innovative Digital Multi-Sided Platform Startups? An Investigation of Entrepreneurial Behavior in Platform-Based Open Innovation. Benchmarking Int. J. 2023, 30, 3534–3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.W.M.; Kwong, C. Path- and place-dependence of entrepreneurial ventures at times of war and conflict. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2017, 35, 903–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dajani, H.; Akbar, H.; Carter, S.; Shaw, E. Defying contextual embeddedness: Evidence from displaced women entrepreneurs in Jordan. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2019, 31, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubner, S.V.; Baum, M. Entrepreneurs’ human resources development. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2018, 29, 357–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.P.; Hörisch, J. Reinforcing or counterproductive behaviors for sustainable entrepreneurship? the influence of causation and effectuation on sustainability orientation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 908–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawa, S.; Marks, J. An effectuation approach to sustainable entrepreneurship. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2024, 16, 1930–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, G.; Roberts, D.L.; Perks, H.; Candi, M. Effectuation logic and early innovation success: The moderating effect of customer co-creation. Br. J. Manag. 2022, 33, 1757–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassalle, P.; Shaw, E. Trailing wives and constrained agency among women migrant entrepreneurs: An intersectional perspective. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2021, 45, 1496–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harima, A.; Freudenberg, J. Co-creation of social entrepreneurial opportunities with refugees. J. Soc. Entrep. 2020, 11, 40–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dushime, J.; Muathe, S. Refugee entrepreneurship: Talent displacement, integration and social-economic inclusion in Kenya. Int. J. Entrep. Bus. Dev. 2023, 6, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Khurana, I.; Dutta, D.K.; Schenkel, M.T. Crisis and arbitrage opportunities: The role of causation, effectuation and entrepreneurial learning. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2022, 40, 236–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitlo, Q.; Pacho, F.T.; Liu, J.; Bhutto, T.A.; Xuhui, W. The Role of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy in Resources Acquisition in a New Venture: The Mediating Role of Effectuation. SAGE Open 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensel, R.; Visser, R. Does Personality Influence Effectual Behaviour? Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2020, 26, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Forcibly Displaced: Toward a Development Approach Supporting Refugees, the Internally Displaced, and Their Hosts, 1st ed.; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kish, L. Survey Sampling; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Tourangeau, R.; Yan, T. Sensitive questions in surveys. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 133, 859–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frese, T.; Geiger, I.; Dost, F. An empirical investigation of determinants of effectual and causal decision logics in online and high-tech start-up firms. Small Bus. Econ. 2020, 54, 641–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullagh, P. Generalized Linear Models, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen, K.; Landau, L.B. The dual imperative in refugee research: Some methodological and ethical considerations in social science research on forced migration. Disasters 2003, 27, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Protection Cluster Working Group. Handbook for the Protection of Internally Displaced Persons; UNHCR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning; EMEA: Andover, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, D.; Saade, F.; Wincent, J. How to circumvent adversity? refugee-entrepreneurs’ resilience in the face of substantial and persistent adversity. J. Bus. Ventur. 2020, 35, 105940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoones, I. Sustainable Livelihoods and Rural Development; Practical Action Publishing Rugby: Rugby, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell, F.E. Regression Modeling Strategies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Deligianni, I.; Voudouris, I.; Lioukas, S. Do effectuation processes shape the relationship between product diversification and performance in new ventures? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 41, 349–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wauters, B.; Lambrecht, J. Barriers to refugee entrepreneurship in Belgium: Towards an explanatory model. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2008, 34, 895–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloosterman, R.C. Matching opportunities with resources: A framework for analysing (migrant) entrepreneurship from a mixed embeddedness perspective. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2010, 22, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Williams, T.A. Local venturing as compassion organizing in the aftermath of a natural disaster: The role of localness and community in reducing suffering. J. Manag. Stud. 2014, 51, 952–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, S.; Naudé, W.; Stel, N. Refugee entrepreneurship: Context and directions for future research. Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 56, 933–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmich, M.; Mitra, J. Can entrepreneurship enable economic and social integration of refugees? A comparison of the economic, social and policy context for refugee entrepreneurship in the UK and Germany. J. Entrep. Innov. Emerg. Econ. 2023, 9, 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilbrunn, S.; Iannone, R.L. From center to periphery and back again: A systematic literature review of refugee entrepreneurship. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazlou, A.; Wennberg, K. How Kinship Resources Alleviate Structural Disadvantage: Self-Employment Duration Among Refugees and Labor Migrants. J. Enterprising Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2023, 17, 16–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dajani, H.; Marlow, S. Impact of women’s home-based enterprise on family dynamics: Evidence from Jordan. Int. Small Bus. J. 2010, 28, 470–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, T.; Nelson, R.E. Creating something from nothing: Resource construction through entrepreneurial bricolage. Adm. Sci. Q. 2005, 50, 329–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]