Abstract

This research assesses the involvement of green urban spaces in creating social interaction among the residents of a neighborhood. It emphasizes the significance of urban parks, particularly in the context of Saudi Arabia’s New Vision 2030, and showcases the proactive approach of Jubail Industrial City in planning and distributing parks. The study delves into the legibility of parks, exploring factors that impact user experiences, including accessibility and amenities. It highlights how park design can influence social interactions. Furthermore, the research underscores the importance of social interaction within neighborhood parks, especially among diverse cultural and age groups. The results prove to be a significant output for future use in enhancing the quality of green spaces and providing efficient means of social interaction among people. The study’s findings, such as increased social interaction with diverse amenities and improved safety perceptions, contribute to sustainable urban planning by fostering social cohesion, enhancing ecological benefits through tree cover, and building community resilience, aligning with Vision 2030’s sustainability goals. Recommendations are provided to improve the park user experience and promote increased utilization of neighborhood parks.

1. Introduction

Cities worldwide are experiencing rapid urbanization, leading to increased population density and the division of urban areas into suburbs and districts [1]. In Saudi Arabia, the New Vision 2030 initiative emphasizes the creation of livable, sustainable urban environments, with urban green spaces playing a pivotal role in enhancing residents’ quality of life [2,3]. Consequently, the New Vision 2030 initiative aligns with global metamodern urban narratives, blending modernist goals of sustainability and livability with an acknowledgment of cultural pluralism and complexity, aiming to create public spaces that foster human flourishing [4,5]. Vision 2030 prioritizes three sustainability pillars: environmental quality (e.g., biodiversity, heat mitigation), social cohesion (e.g., inclusive community spaces), and urban resilience (e.g., accessible infrastructure). This study addresses these pillars by investigating how green spaces in Jubail enhance social interaction, support ecological health through native vegetation [6], and promote resilient urban design, filling a knowledge gap in culturally diverse Saudi contexts [7,8]. Jubail Industrial City, a forward-thinking urban center, has prioritized park development for over four decades, integrating green spaces into its districts to serve as communal hubs for social interaction [9]. However, there is a knowledge gap regarding how these parks facilitate social interactions among diverse cultural and age groups in Saudi Arabia, particularly in the context of neighborhood parks [7,8].

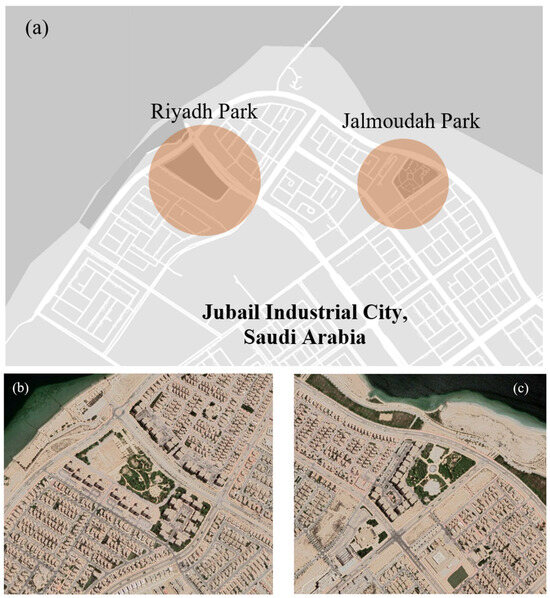

This study aims to investigate the impact of urban green spaces on social interaction in Jubail’s neighborhoods, focusing on two parks: Riyadh Park and Jalmoudah Park. By examining factors such as park legibility, accessibility, amenities, and cultural diversity, the research seeks to understand how park design influences social cohesion [10,11]. The findings aim to inform urban planners and policymakers in designing sustainable parks that enhance social, environmental, and urban outcomes, aligning with Vision 2030′s sustainability framework.

Literature Review

Urban green spaces are dynamic fields oscillating between modernist ideals of planned, functional design and postmodern relationality, embodying a metamodern “both/and” approach that balances structure with emergent social and emotional potentials [4,5]. Parks and playgrounds are critical components of sustainable urban development, providing environmental, social, and health benefits [2,3,12]. This study adopts a metamodern lens, viewing parks as relational spaces where social interactions emerge from hybrid landscapes (blending cultural identities) and affective atmospheres (emotional resonance), integrating rational planning with co-created experiences [4]. Jan Gehl’s Life Between Buildings underscores human-centered design, advocating for “lively, safe, sustainable” spaces [13], while spatial syntax highlights ecological relationships between urban elements [14].

Social Cohesion and Cultural Inclusivity: Parks promote environmental equity, ensuring access to healthy outdoor spaces [15]. Immigrants use parks to build cultural connections [16], and social cohesion reduces depressive symptoms [17,18]. Accessibility, safety, and inclusivity attract diverse users [19,20], with parks fostering creativity and tolerance through multicultural experiences [21,22,23,24]. These findings reflect relational space, where parks act as hybrid arenas for cultural exchange, oscillating between planned inclusivity and emergent intercultural dialogue [4,5].

The social environment of neighborhoods significantly influences park use. Higher levels of social cohesion correlate with fewer depressive symptoms among park users [17,18], while accessibility, safety, and inclusivity attract diverse populations [19,20]. Turna and Bhandari [25] analyzed park usage patterns, demonstrating their role in facilitating recreational activities and community engagement. Similarly, Xu et al. [26] found that new parks positively impact residents’ physical activity, mental health, and social interaction. Zhang et al. [7] emphasized that urban green spaces provide settings for shared experiences, enhancing neighborhood social ties, while Ramezani Mehrian et al. [27] highlighted their role in improving urban livability.

Health and Well-Being: Green spaces reduce anxiety in low-income areas [28,29] and supported mental health during COVID-19 [30]. Park legibility, shaped by spatial design and seating orientation, enhances user experience [10]. Affective atmospheres, such as natural sounds, create emotional resonance, encouraging social interaction [4,31]. Ecological Sustainability: Parks preserve biodiversity and mitigate urban heat with native plants and tree cover [6]. Green alleys enhance connectivity [6], aligning with modernist sustainability goals and postmodern ecological complexity [4].

Park design and amenities, such as sports courts, playgrounds, and walking paths, significantly influence social activities [32,33]. Cohen et al. [34] noted that facilities like restrooms and picnic areas enhance park legibility and user engagement. Chen et al. [11] found that esthetic appeal and cleanliness are critical for social interaction, often outweighing the mere presence of facilities. Park renewal projects, as observed in Belgium, increase utilization, physical activity, and social cohesion [35]. Natural sounds in parks further encourage group interactions compared to artificial noise [31].

Multicultural experiences in parks enhance creativity and foster tolerance, promoting social justice and community harmony [21,22,23,24]. Studies show no significant differences in park use among racial groups, with physical activity and social interaction being primary purposes [8,36,37,38,39]. Different demographic groups benefit uniquely: older adults engage in physical and social activities for healthy aging [33], while adolescents use parks for social connectedness [40]. Jennings and Bamkole [41] emphasized that well-maintained parks promote inclusivity, with natural elements and amenities like benches facilitating social interaction among older adults [42,43]. Interracial contact in parks can reduce prejudice and encourage civic engagement [44].

Vision 2030 Contextualization: Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 reflects metamodern aspirations, blending modernist urban planning with postmodern cultural diversity, positioning parks as spaces for social cohesion and sustainability within global urban narratives [2,3,4,5]. Gaps remain in understanding how park design fosters social dynamics in culturally diverse Saudi contexts, which this study addresses through a metamodern lens.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The study was conducted in Jubail Industrial City, Saudi Arabia. The zones and parks were selected at one of the city’s new districts called Jalmoudah. A sampling criteria technique was developed to select the sample location for the study which included the consideration of a modern and newly built area, the accommodation type near the area, and the ethnicity of the residents of the area. Jalmoudah is a newly built district in Jubail Industrial City and the selected parks are surrounded by different types of housing units comprising large and medium-sized villas, apartment complexes, and seafront locations, as shown in Figure 1a. Also, the residents of the area come from varying cultural backgrounds. The study included two parks: Riyadh Park, covering approximately 25,000 square meters, and Jalmoudah Park, spanning approximately 18,000 square meters. The satellite images of the parks are provided in Figure 1b,c showing their neighborhoods, as well as photos from both parks shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 1.

(a) Key plan of Jubail Industrial City, (b) satellite image of Riyadh Park, and (c) satellite image of Jalmoudah Park showing respective neighborhoods.

Figure 2.

Photo of Riyadh Park.

Figure 3.

Photo of Jalmoudah Park.

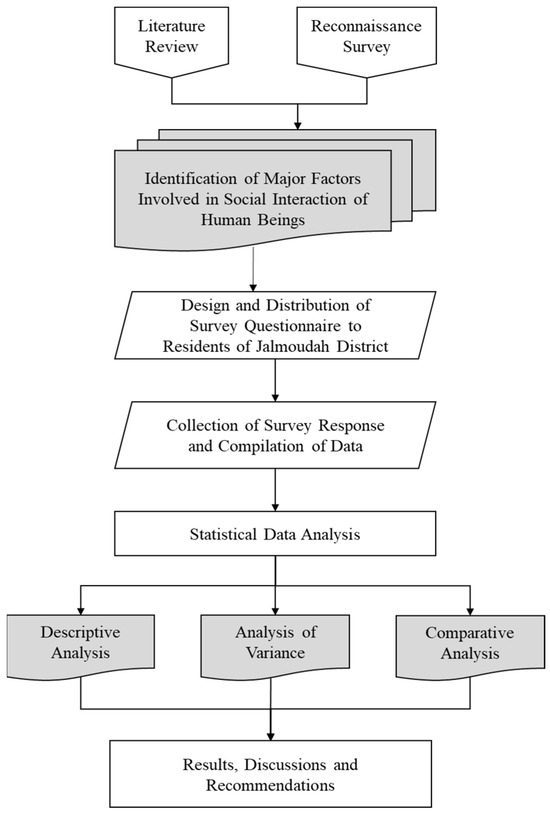

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

This study uses a mixed-method survey that was structured and assembled by the authors. It focuses on applying quantitative and qualitative techniques to assess the relationship between cultural background, social interaction, and improvement criteria by investigating the participant’s needs. Initially, an extensive literature review was performed, and a reconnaissance survey was conducted around various parks in the city to list the factors involved in the social interaction of human beings and to observe the basic trends and culture of people visiting the parks. Based on these details, a comprehensive questionnaire was designed to be distributed to the residents of the selected area. The complete steps followed for the achievement of objectives through this study are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Research methodology and procedure of analysis.

2.3. Research Questions and Hypotheses

This study addresses the following questions:

- How do park design and amenities influence social interaction among diverse groups in Jubail’s neighborhoods?

- What demographic factors (age, gender, nationality) affect park-based social interaction?

- How do safety and accessibility perceptions shape park usage?

Hypotheses included the following: (1) parks with diverse amenities increase social interaction; (2) younger adults and females engage more in social activities; (3) perceived safety enhances park visitation.

Research Design: A mixed-method approach was employed, combining a literature review, questionnaire survey, and statistical analysis (Figure 4). The study focused on Riyadh Park and Jalmoudah Park in Jubail Industrial City.

For statistical analysis, the response mean, and response standard deviation were calculated by using Equations (1) and (2), respectively.

where x is the corresponding value provided by the respondent and n is the total number of respondents for a specific question.

Moreover, the response percentage obtained for all questions was assessed separately and the factor that received the highest number of selections was considered the highest priority. Along with this, the response to all questions was compared together as well by using the method of Weighted Averages (Aw). The following equation was used to calculate the WA of each factor.

where Aw is the Weighted Average, Ri is the number of respondents for a specific level n of the Likert scale, and n ranges from 1 to 5.

2.4. Structure of Survey Questionnaire

To build up the study, the survey tool was used with both open- and closed-ended questions to be addressed by the residents of the area to measure and evaluate the eligibility of outdoor spaces for users, the application of human factors, and cultural and social factors. The questionnaire was divided into three major sections: biographical information and attributes, social behavior, and opinions and recommendations. The biographical information questions included the options for the gender, age, social status, and nationality of the respondent. These factors are used to analyze their social behavior by comparison with the data obtained in their sections. The questions included in social behavior and opinions and recommendations are shown in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Questionnaire to assess social behavior of people in parks.

Table 2.

Questionnaire to obtain opinions on facilities in parks.

3. Results

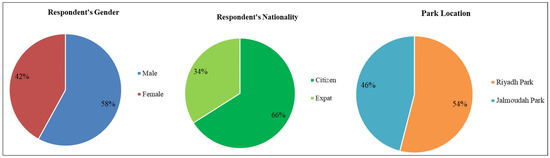

The survey (95 distributed, 83 responses) addressed research questions, revealing how park design, demographics, and perceptions influence social interaction. As mentioned earlier, two locations were selected for the survey, and 46 people responded from Riyadh Park, contributing to 54% of the total respondents. In contrast, this number is 46% for Jalmoudah Park with 37 respondents, as shown in Figure 5. The data obtained through the responses was compiled and analyzed in various aspects. The analysis included descriptive statistical analysis, analysis of variance, and comparative analysis. The demographic data of the respondents, as shown in Figure 5, shows that almost 65% of the respondents belonged to the age group of 30–45, which is a young and experienced class of educated people who have a good understanding of social norms and living standards. Of the respondents, 58% were male, whereas 42% were female. Also, 66% of them were Saudi citizens, whereas 34% were from other nationalities and were living as expatriates.

Figure 5.

Demographical analysis of the respondents.

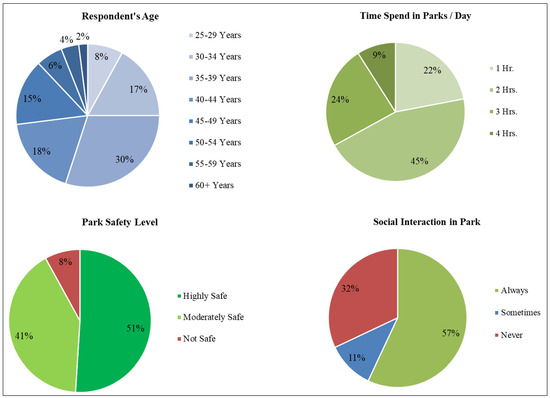

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

The data obtained for the other few questions, as shown in Figure 6, is put through descriptive analysis, and the results are shown in Table 3. Figure 6 shows that most of the people spend almost 2 h. in the park, and 51% of the people consider the park highly safe. A good number of people agreed that they visit the park for social interaction. The values mentioned in the response mean column are the average of the scale value opted by the respondents. For better clarification, the second column shows the interpreted average value of each parameter. The low values of standard deviation for these categories show that the difference in people’s opinion is less. Hence, the results can be considered sufficiently reliable and are eligible for further analysis.

Figure 6.

Graphical presentation of responses of park visitors.

Table 3.

Descriptive analysis of data obtained through survey.

3.2. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)

ANOVA is a statistical method used to analyze the differences between the means of two or more groups or treatments. It is often used to determine whether there are any statistically significant differences between the means of different groups. The seven variables involved in the research were tested and analyzed to find the relationship between them. The results of the test are shown in Table 4. From the table, there is a strong relationship between the groups as the Probability (p-value) result is very low and lies within the range of 0.05, as highlighted in the table. The relationship of one variable with the other is discussed below one by one in the comparative analysis.

Table 4.

Results of analysis of variance (ANOVA).

3.3. Comparative Analysis

Comparative analysis is performed using the Q-Test. This test helps to evaluate whether a questionable data point should be retained or discarded. In general, this test can be thought of as comparing the difference between the questionable number and the closest value in the set to the range of all numbers. The results of the Q-Test performed for the compiled data are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Results of comparative analysis (Q-Test).

3.3.1. Relationship of Age with Other Variables

In Table 5, the analysis result demonstrates that age is a significant factor affecting the social interaction level of neighborhood parks. The age variable was examined with various dependent variables. The p-value for age relative to the dependent variables has almost the same ratio of −2.2 × 10−14 except for the relationship of age to safety in parks, where the p-value achieved 6.57 × 10−9.

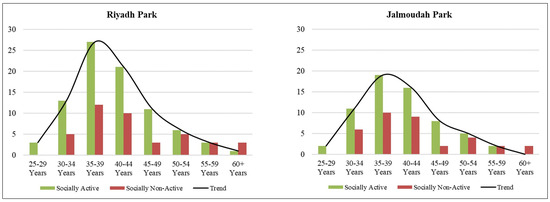

Addressing research question 2, demographic analysis showed that 65% of respondents were aged 30–45, 58% were male, and 66% were Saudi. ANOVA results (p < 0.05, Table 4) indicated significant differences in social interaction by age, gender, and nationality. Younger adults (30–45) and females reported higher social engagement (75% vs. 35% for males), supporting Hypothesis 2. Expatriates showed lower interaction in Jalmoudah Park, possibly due to fewer culturally relevant amenities (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Age vs. social interaction of visitors.

Addressing research question 3, 51% rated parks as highly safe, encouraging visitation (Figure 6). Suggestions for fencing and first aid stations indicate safety concerns, particularly in Jalmoudah Park. Accessibility (e.g., walking paths) was positively associated with interaction, supporting Hypothesis 3.

The participants were asked for their reasons for being socially active or non-active, and the responses received indicate that the visitors prefer not to socialize with new people for several reasons including that they prefer to spend their time with their families or that they just visit the park for physical activity. Also, it is important to note that the difference between being socially active and non-active decreases with the increase in age. Elderly respondents mentioned that they do not interact with new people as they already have enough contact in their social lives.

3.3.2. Relationship of Gender with Other Variables

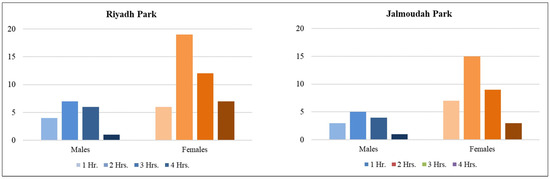

From Table 5, the data represents a substantial variation between gender and the time spent in parks with a p-value of 6.57 × 10−9. On the other hand, there are no considerable differences in gender relational to nationality.

The bar charts shown in Figure 8 illustrate the distribution of participants by gender and time spent in each park. As clearly visible, females enjoy the green spaces more than the males. Most people spend at least 2 h a day in the parks. Furthermore, as per the collected data, females show a higher level of social interaction among each other as compared to males. The data shows that 75% of women agreed that they visit the park to meet new people or they come as a group of neighbors to enjoy some time with children during the daytime, whereas this value was found to be only 35% among males.

Figure 8.

Gender vs. time spent in parks for visitors.

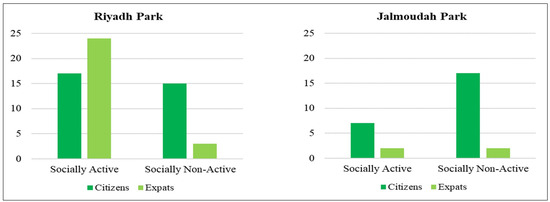

3.3.3. Relationship of the Social Interaction with the Nationality

The graph shown in Figure 9 demonstrates the deviation of the social interaction level between parks and the nationality of the visitors. Although mixed results were found after the analysis, Riyadh Park has significantly increased social interaction levels for citizens and the expat population. In contrast, the citizens who were not socially interactive scored almost similar average numbers in both parks compared to the expats. This difference is found to be the reason for the basic facilities available in both parks. Riyadh Park is found to be ahead in development. That is why there is a bigger number of visitors in Riyadh Park as compared to Jalmoudah Park, as also visible in Figure 7.

Figure 9.

Nationality vs. social interaction of visitors.

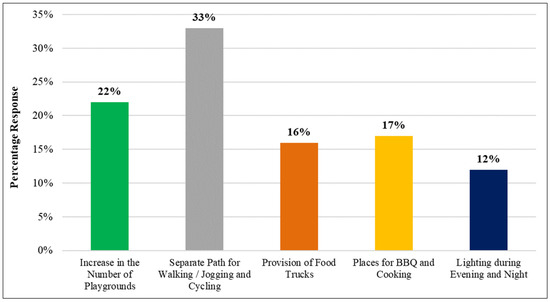

3.3.4. Opinion on Facilities in Parks

Regarding the opinion of the participants related to the required improvements in the parks, valuable data were collected as shown in Figure 10. Addressing research question 1, respondents spent about 2 h in parks, with Riyadh Park users reporting higher interaction due to playgrounds, BBQ areas, and tree cover (Table 3). A Q-Test confirmed strong relationships between amenities and interaction (Table 5). Respondents emphasized shaded areas in Riyadh Park for thermal comfort [6], supporting Hypothesis 1. Jalmoudah Park’s limited facilities correlated with lower engagement (Figure 10). Also, they opted for a similar option for children to have more playgrounds in the parks. Although a bit lower, the suggestion of adding food trucks, BBQ places, and improving the lighting during evening and night was also selected by the respondents. Notably, several respondents emphasized the need for more shaded areas provided by trees, which they associated with increased comfort during hot weather, particularly in Riyadh Park where tree cover was more extensive [6].

Figure 10.

Results of opinions of visitors.

Related to the safety level and arrangements in the parks, several participants suggested closing the park entries with fences to prevent children from going out. Others mentioned that a first aid box is a primary requirement in the case of any injury to the children and some of the visitors also mentioned the importance of having a guard during peak hours.

4. Discussion

This study provides insights into urban green spaces’ role in fostering social interaction in Jubail, aligning with Vision 2030’s metamodern goals [4,5]. Findings are systematically linked to research questions and prior research, reflecting parks’ dual nature as planned and emergent spaces. The findings confirm that park design, accessibility, and amenities significantly influence social cohesion, particularly in culturally diverse neighborhoods like Jalmoudah.

Research question 1 (Park Design and Amenities): Riyadh Park exhibited higher social interaction levels than Jalmoudah Park, likely due to its superior facilities, including playgrounds, restrooms, and esthetic appeal, as supported by Chen et al. [11]. This aligns with Gehl’s principles, which emphasize that well-designed public spaces with accessible amenities foster “life between buildings” and spontaneous social interactions [13]. The presence of extensive tree cover in Riyadh Park, as noted by respondents, likely enhances thermal comfort, encouraging longer visits and more social activities, consistent with the findings of Halder et al. (2025) [6]. This reflects a metamodern balance: rational planning (amenities) enables emergent sociality (relational space) [4].

Research question 2 (Demographic Factors): Younger adults and females showed higher engagement, consistent with the findings of Schmidt et al. [42]. Expatriate patterns suggest cultural barriers, highlighting parks’ hybridity as both inclusive and exclusionary spaces [4,5]. Research question 3 (Safety and Accessibility): Perceived safety and accessibility boosted interaction, echoing the findings of Cohen et al. [34]. Affective atmospheres, like natural sounds, enhance emotional resonance, encouraging sociality [4,31].

The significant relationship between age and social interaction (p-value ≈ −2.2 × 10−14) suggests that younger adults (30–45 years) are more socially active, possibly due to family-oriented visits, while older adults prefer familiar social circles, aligning with the findings of Schmidt et al. [42]. Gender differences were notable, with females spending more time in parks and engaging in higher amounts of social interaction (75% vs. 35% for males), reflecting cultural preferences for group activities among women in Saudi Arabia [45]. Nationality also played a role, with expatriates showing lower social interaction in Jalmoudah Park, potentially due to there being fewer culturally relevant amenities [8].

The findings resonate with metamodern urban studies, where parks oscillate between utopian aspirations (social cohesion) and complexity (cultural differences) [4,5]. Riyadh Park’s planned amenities contrast with Jalmoudah Park’s emergent interactions, illustrating parks’ dual nature [4]. Limitations include a small sample (n = 83), potential self-selection bias (respondents may be frequent park users), and ambiguous expatriate results, which may reflect cultural unfamiliarity. The cross-sectional design limits temporal insights. Future research could use longitudinal methods or qualitative interviews to explore cultural barriers. Also, the current study resonated with other studies emphasizing playgrounds and physical activity facilities, echoing the findings of Sun et al. [32], who noted that diverse amenities attract broader user groups. The preference for shaded areas and natural elements aligns with the findings of Chen and Kang [31], highlighting the role of natural sounds in encouraging group interactions.

The call for more tree planting in Jalmoudah Park supports the findings of Halder et al. (2025), who emphasize trees’ role in mitigating urban heat and enhancing user comfort [6]. The higher satisfaction in Riyadh Park supports the findings of Cohen et al. [34], who linked amenities like picnic areas to increased park use. The accessibility and design of Riyadh Park, which facilitate face-to-face interactions, reflect Gehl’s advocacy for human-scale urban environments that prioritize walkability and social engagement [13]. Furthermore, the potential for parks to support biodiversity, as seen in designs incorporating native plants, could enhance their ecological value in Jubail, aligning with the findings of Halder et al. (2025) [6]. However, this study extends these insights by contextualizing them in Jubail, where cultural diversity and Vision 2030 priorities shape park usage.

Several limitations must be acknowledged. The sample size (83 respondents) may limit generalizability, and the cross-sectional design does not capture seasonal or longitudinal trends. Future research could employ larger samples and longitudinal methods to explore how park usage evolves over time. Additionally, qualitative interviews could provide deeper insights into cultural barriers to social interaction, particularly for expatriates. Future studies could also investigate how biodiversity-focused park designs impact user perceptions and ecological outcomes in Jubail’s arid climate [6].

The findings have practical implications for urban planners in Jubail and similar cities, including the following: Enhancing Jalmoudah Park with amenities and trees [6] could boost interaction. Green alleys and Gehl-inspired designs [6,13] align with metamodern goals of connectivity and human flourishing, addressing urban challenges like cultural integration and sustainability [4,5]. Incorporating multicultural design elements, such as spaces for intercultural events, could bridge cultural divides, as suggested by Powers et al. [44]. Drawing on Gehl’s principles, planners should prioritize pedestrian-friendly access and flexible urban furniture to create inviting, inclusive spaces that encourage spontaneous social interactions [13]. Moreover, aligning park design with environmental equity principles [15] ensures inclusive access for all demographic groups, fostering social cohesion and supporting Vision 2030′s livability goals.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study aimed to explore the factors that affect the social interaction of people within neighborhood parks and the improvement requirements to enrich the visitor’s experience. The study found a strong relationship between social interaction and cultural factors such as nationality, gender, and age groups, as these were examined using one-way ANOVA and comparative analysis. The results complemented each other when the assessments were performed for two different locations. Riyadh Park was significantly active for different ages and groups. This can be interpreted through many factors, such as the variety of residents living around each park, facilities, and safety level. The factors that were highlighted in the results were the availability of playgrounds, food trucks, BBQ spots, places for physical activities, and the level of night lighting. Respondents also emphasized the need for more shaded areas, particularly in Jalmoudah Park, to enhance thermal comfort during hot weather, aligning with the benefits of tree cover observed in Riyadh Park [6]. This in-depth study delivers insights and knowledge of the importance of the variety of users using the park, which affects the level of social interaction within and between neighbors and neighborhoods. Using parks to socialize with people from different cultural backgrounds is a healthy phenomenon for human beings. This study recognized the importance of different groups using the parks that positively affects the cycle of park visitation that is aligned with the visitors’ needs.

To enhance the social and ecological value of neighborhood parks in Jubail, we recommend the following:

- Increase the number of playgrounds, BBQ areas, and food truck spaces to attract diverse user groups and encourage social interaction.

- Improve lighting and safety features, such as fencing and first aid stations, to enhance user comfort and security.

- Incorporate multicultural design elements, such as spaces for intercultural events, to foster inclusivity among diverse residents.

- Plant more trees, particularly native species, in Jalmoudah Park to enhance thermal comfort and support biodiversity, drawing on the success of Riyadh Park’s tree cover [6].

- Develop green alleys or corridors to connect Riyadh Park and Jalmoudah Park with surrounding neighborhoods, improving pedestrian access and ecological connectivity [6].

- Incorporate design strategies inspired by Jan Gehl, such as circular seating arrangements to encourage face-to-face conversations, pedestrian-friendly access to enhance walkability, and flexible urban furniture (e.g., movable seats) to allow users to customize social spaces, fostering spontaneous interactions [13].

5.1. Guidelines for Designers and Officials

To shape parks that integrate people and nations, designers and officials should prioritize the following strategies, informed by this study’s findings and best practices in urban design [11,13,44]:

- Design Inclusive Spaces: Create flexible, multipurpose areas (e.g., open lawns, amphitheaters) that accommodate diverse activities like cultural festivals, sports, and communal dining, encouraging interactions across nationalities [44].

- Enhance Cultural Representation: Incorporate signage, art installations, or landscaping reflecting Jubail’s multicultural community (e.g., native and regional plant species) to foster a sense of belonging [6].

- Promote Accessibility and Connectivity: Ensure universal accessibility (e.g., ramps, shaded pathways) and connect parks via green corridors to integrate diverse neighborhoods, enhancing social cohesion [6,13].

- Foster Human-Scale Interaction: Use Gehl-inspired elements like clustered seating, low barriers, and clear sightlines to create intimate, welcoming environments that encourage dialogue and reduce cultural barriers [13].

- Engage Communities in Design: Involve residents from varied backgrounds in participatory design processes to ensure that parks reflect local needs and promote shared ownership, aligning with Vision 2030′s community focus [2].

5.2. Contributions to Sustainability

This study contributes to sustainability by demonstrating how urban green spaces in Jubail enhance three key dimensions. Socially, the findings show that diverse amenities and inclusive design foster intercultural interaction and community cohesion, supporting social sustainability [44]. Environmentally, the emphasis on native tree planting and green corridors improves biodiversity, mitigates urban heat, and enhances air quality, aligning with ecological sustainability goals [6]. From an urban perspective, improved safety and accessibility features promote resilient, livable cities, contributing to Vision 2030′s sustainable urban growth objectives [2,3]. These insights provide a framework for designing sustainable parks that balance social vitality with ecological integrity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M.A. and B.M.A.; methodology, R.M.A., B.M.A. and T.A.; software, R.M.A. and A.H.A.; validation, R.M.A., B.M.A. and M.S.A.; formal analysis, H.M.N.A. and Z.A.A.E.; investigation, R.M.A.; resources, R.M.A.; data curation, B.M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, R.M.A. and B.M.A.; writing—review and editing, A.M.A. and M.S.A.; visualization, H.M.N.A. and Z.A.A.E.; supervision, B.M.A.; project administration, T.A.; funding acquisition, R.M.A., B.M.A., A.M.A., T.A., A.H.A., H.M.N.A., Z.A.A.E. and M.S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University (Approval Code IRB-PGS-2025-06-0075) on 4 February 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during this research are available from the corresponding author and can be provided upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Catalani, A.; Nour, Z.; Versaci, A.; Hawkes, D.; Bougdah, H.; Sotoca, A.; Ghoneem, M.; Trapani, F.; Catalani, A.; Nour, Z.; et al. Cities’ Identity Through Architecture and Arts; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.perlego.com/book/1476790/cities-identity-through-architecture-and-arts-proceedings-of-the-international-conference-on-cities-identity-through-architecture-and-arts-citaa-2017-may-1113-2017-cairo-egypt-pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Maniruzzaman, K.M.; Alqahtany, A.; Abou-Korin, A.; Al-Shihri, F.S. An analysis of residents’ satisfaction with attributes of urban parks in Dammam city, Saudi Arabia. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2021, 12, 3365–3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtany, A.; Jamil, R. Evaluation of Educational Strategies in the Design Process of Infrastructure for a Healthy Sustainable Housing Community. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2022, 13, 101665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlovič, R.; Matlovičová, K. The Metamodern Shift in Geographical Thought: Oscillatory Ontology and Epistemology, Post-disciplinary and Post-paradigmatic Perspectives. Folia Geogr. 2025, 67, 22–69. [Google Scholar]

- Storm, J.A.J. Metamodernism: The Future of Theory; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-0-226-78665-0. [Google Scholar]

- Halder, N.; Kumar, M.; Deepak, A.; Mandal, S.K.; Azmeer, A.; Mir, B.A.; Nurdiawati, A.; AlGhamdi, S.G. The Role of Urban Greenery in Enhancing Thermal Comfort: Systematic Review Insights. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; van Dijk, T.; Tang, J.; van den Berg, A.E. Green Space Attachment and Health: A Comparative Study in Two Urban Neighborhoods. International. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 14342–14363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughan, C.A.; Cohen, D.A.; Han, B. How Do Racial/Ethnic Groups Differ in Their Use of Neighborhood Parks? Findings from the National Study of Neighborhood Parks. J. Urban Health 2018, 95, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RCJ. Jubail Industrial City Guide. 2023. Available online: https://rcj.gov.sa/JicGuide/Beach.html (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Moulay, A.; Ujang, N. Legibility of neighborhood parks and its impact on social interaction in a planned residential area. ArchNet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2016, 10, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Sleipness, O.; Christensen, K.; Yang, B.; Park, K.; Knowles, R.; Yang, Z.; Wang, H. Exploring associations between social interaction and urban park attributes: Design guideline for both overall and separate park quality enhancement. Cities 2024, 145, 104714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnaim, A.; Dano, U.L.; Alqahtany, A.M. Factors Influencing Social Interaction in Recreational Parks in Residential Neighborhoods: A Case Study of the Dammam Metropolitan Area, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sorana, R. Interior Public Spaces. Addressing the Inside-Outside Interface—Graz University of Technology. SITA—Studii de Istoria si Teoria Arhitecturii. 2017. Available online: https://graz.pure.elsevier.com/en/publications/interior-public-spaces-addressing-the-inside-outside-interface (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Zhang, R.; Sun, F.; Shen, Y.; Peng, S.; Che, Y. Accessibility of urban park benefits with different spatial coverage: Spatial and social inequity. Appl. Geogr. 2021, 135, 102555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munet-Vilaró, F.; Chase, S.M.; Echeverria, S. Parks as Social and Cultural Spaces Among U.S.- and Foreign-Born Latinas. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2018, 40, 1434–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, L.G.; Arredondo, E.M.; McKenzie, T.L.; Holguin, M.; Elder, J.P.; Ayala, G.X. Neighborhood Social Cohesion and Depressive Symptoms Among Latinos: Does Use of Community Resources for Physical Activity Matter? J. Phys. Act. Health 2015, 12, 1361–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero Peña, J.E.; Kodali, H.; Ferris, E.; Wyka, K.; Low, S.; Evenson, K.R.; Dorn, J.M.; Thorpe, L.E.; Huang, T.T.K. The Role of the Physical and Social Environment in Observed and Self-Reported Park Use in Low-Income Neighborhoods in New York City. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 656988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mani, M.; Hosseini, S.M.; Ramayah, T. Parks as business opportunities and development strategies. Bus. Strategy Ser. 2012, 13, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, P.A.; Lopes, C.S.; da Silveira, I.H.; Faerstein, E.; Junger, W.L. Is living near green areas beneficial to mental health? Results of the Pró-Saúde Study. Rev. Saúde Pública 2019, 53, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, A.K.Y.; Maddux, W.W.; Galinsky, A.D.; Chiu, C.Y. Multicultural Experience Enhances Creativity: The When and How. Am. Psychol. 2008, 63, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayadi, K.; Abduh, A.; Basri, M. A meta-analysis of multicultural education paradigm in Indonesia. Heliyon 2022, 8, e08828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudigdo, A.; Pamungkas, O.Y. Multiculturalism in Children’s Literature: A Study of a Collection of Poems by Elementary School Students in Yogyakarta. Daengku J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Innov. 2022, 2, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena, J.A.; Rogers, M.R. Factors associated with multicultural teaching competence: Social justice orientation and multicultural environment. Train. Educ. Prof. Psychol. 2017, 11, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turna, N.; Bhandari, H. Role of Parks as Recreational Spaces at Neighborhood Level in Indian Cities. ECS Trans. 2022, 107, 8685–8694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, F.; Chen, L.; Zhang, W. Perceived urban green and residents’ health in Beijing. SSM—Popul. Health 2021, 14, 100790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramezani Mehrian, M.; Manouchehri Miandoab, A.; Abedini, A.; Aram, F. The Impact of Inefficient Urban Growth on Spatial Inequality of Urban Green Resources (Case Study: Urmia City). Resources 2022, 11, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raap, S.; Knibbe, M.; Horstman, K. Clean Spaces, Community Building, and Urban Stage: The Coproduction of Health and Parks in Low-Income Neighborhoods. J. Urban Health 2022, 99, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaeztavakoli, A.; Lak, A.; Yigitcanlar, T. Blue and Green Spaces as Therapeutic Landscapes: Health Effects of Urban Water Canal Areas of Isfahan. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulset, V.; Venter, Z.; Charlott, E.; Nordbø, A. Increased nationwide recreational mobility in green spaces in Norway during the COVID-19 pandemic. Environ. Int. 2023, 180, 108190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Kang, J. Natural sounds can encourage social interactions in urban parks. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 239, 104870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Tan, S.; He, Q.; Shen, J. Influence Mechanisms of Community Sports Parks to Enhance Social Interaction: A Bayesian Belief Network Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Maliki, N.Z.; Wang, Y. The Role of Urban Parks in Promoting Social Interaction of Older Adults in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.A.; Han, B.; Williamson, S.; Nagel, C.; McKenzie, T.L.; Evenson, K.R.; Harnik, P. Playground features and physical activity in U.S. neighborhood parks. Prev. Med. 2020, 131, 105945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppe, L.; Van Dyck, D.; De Keyser, E.; Van Puyvelde, A.; Veitch, J.; Deforche, B. The impact of renewal of an urban park in Belgium on park use, park-based physical activity, and social interaction: A natural experiment. Cities 2023, 140, 104428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolch, J.; Wilson, J.P.; Fehrenbach, J. Parks and park funding in Los Angeles: An equity-mapping analysis. Urban Geogr. 2005, 26, 4–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, K.; Elands, B.; Buijs, A. Social interactions in urban parks: Stimulating social cohesion? Urban For. Urban Green. 2010, 9, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, J.W.; Larson, L.R.; Green, G.T.; Kralowec, C. Outdoor recreation motivation and site preferences across diverse racial/ethnic groups: A case study of Georgia state parks. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2017, 18, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dade, M.C.; Mitchell, M.G.E.; Brown, G.; Rhodes, J.R. The effects of urban greenspace characteristics and socio-demographics vary among cultural ecosystem services. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 49, 126641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, E.; Veitch, J.; Loh, V.H.Y.; Salmon, J.; Cerin, E.; Mavoa, S.; Villanueva, K.; Timperio, A. Outdoor public recreation spaces and social connectedness among adolescents. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, V.; Bamkole, O. The Relationship between Social Cohesion and Urban Green Space: An Avenue for Health Promotion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, T.; Kerr, J.; Schipperijn, J. Associations between Neighborhood Open Space Features and Walking and Social Interaction in Older Adults—A Mixed Methods Study. Geriatrics 2019, 4, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, E.; Timperio, A.; Loh, V.H.; Deforche, B.; Veitch, J. Important Park features for encouraging park visitation, physical activity and social interaction among adolescents: A conjoint analysis. Health Place 2021, 70, 102617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, S.L.; Webster, N.; Agans, J.P.; Graefe, A.R.; Mowen, A.J. The power of parks: How interracial contact in urban parks can support prejudice reduction, interracial trust, and civic engagement for social justice. Cities 2022, 131, 104032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rio, C.J.; Saligan, L.N. Understanding physical activity from a cultural-contextual lens. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1223919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).