Abstract

This study, grounded in the Value-Belief-Norm (VBN) theory, examines how tourism sustainability influences pro-environmental tourist behavior through the mediating roles of environmental knowledge and eco-destination image and the moderating role of biospheric value. Data were collected from 396 tourists visiting major destinations in Northern Cyprus via an online survey. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was employed to assess direct, mediating, and moderating effects. The findings reveal that tourism sustainability positively influences social engagement propensity, with both environmental knowledge and eco-destination image acting as significant mediators. Moreover, biospheric values were found to enhance the relationship between tourism sustainability and both mediators, although no moderating effect was observed between tourism sustainability and social engagement propensity. This study extends the application of the VBN theory in the tourism context by framing social engagement as a norm-driven outcome. It provides valuable insights for destination managers aiming to promote sustainable behaviors in emerging eco-tourism settings. This study is limited by its cross-sectional design and single-destination focus. Future research could explore diverse cultural settings and adopt longitudinal approaches to validate and expand upon these findings.

1. Introduction

The rapid expansion of the global tourism industry has brought significant economic, social, and cultural benefits, particularly in regions such as the Eastern Mediterranean. Since 1974, Cyprus has experienced substantial growth in trade and tourism, establishing itself as a key destination in the region [1,2,3,4]. However, this rapid expansion has also posed challenges in maintaining a balance between economic development and environmental sustainability. Sustainable tourism aims to maximize socio-economic benefits while mitigating negative environmental impacts, ensuring the long-term viability of destinations [5]. This approach requires a collective effort to conserve resources, promote safety, and encourage community collaboration in addressing environmental concerns within the tourism sector [6].

A crucial factor in achieving tourism sustainability is the role of tourists themselves, particularly their social engagement propensity, which reflects their inclination to participate in pro-social behaviors that enhance sustainable tourism practices [7,8]. Social engagement has been recognized as an essential factor in fostering sustainability, as tourists actively contribute to destination conservation and community well-being [9,10]. Research in Northern Cyprus highlights how traveler behaviors and employee engagement at tourism destinations play a pivotal role in advancing sustainability initiatives and fostering social participation [11,12,13].

One of the primary enablers of social engagement in sustainable tourism is knowledge about the environment, which equips tourists with the necessary awareness to engage in responsible environmental behaviors. Increased environmental knowledge has been linked to a reduction in the negative impacts of tourism, as informed tourists are more likely to adopt sustainable behaviors that promote ecological preservation and safety [14,15,16]. Similarly, eco-destination image plays a crucial role in shaping tourist perceptions and behaviors, as a strong eco-friendly image encourages repeated visits, enhances overall satisfaction, and reinforces sustainable practices [17].

Another critical determinant of sustainable tourism behavior is biospheric value, which refers to an individual’s intrinsic motivation to protect and sustain the natural environment [18]. Individuals with strong biospheric values are more likely to engage in sustainable tourism practices out of a moral obligation rather than external incentives [19]. Prior research highlights that biospheric values influence pro-environmental behaviors, making them an essential factor in achieving sustainability goals [20,21].

Furthermore, raising tourists’ environmental awareness and fostering engagement with sustainable tourism practices is crucial [22]. Environmental knowledge and eco-destination image play a fundamental role in shaping tourists’ perceived responsibility and willingness to act sustainably [6]. When tourists recognize the environmental consequences of their travel behaviors, they are more likely to internalize sustainability norms and engage in pro-environmental tourism practices [23,24]. The importance of environmental messaging reinforces the notion that effective communication strategies are essential for transforming tourists’ environmental awareness into concrete sustainable behaviors, particularly in destinations where water scarcity and environmental degradation pose significant risks [25].

Recent research has further emphasized the critical influence of environmental knowledge and eco-destination image in shaping sustainable tourist behaviors [26,27,28]. For instance, Kim et al. [29] demonstrated that tourists with higher environmental awareness are more inclined to support green initiatives at destinations. Similarly, Luong [30] highlighted that an eco-destination image can significantly impact tourists’ revisit intentions and pro-environmental actions. In addition, Lee et al. [31] found that perceptions of sustainability initiatives contribute to stronger destination loyalty and ethical engagement.

While previous studies have explored the relationships between tourism sustainability, environmental knowledge, and eco-destination image, limited research has integrated these variables within a unified theoretical framework such as the Value-Belief-Norm (VBN) theory, especially in emerging eco-tourism contexts [32,33]. Moreover, there is a scarcity of empirical work examining how biospheric values interact with environmental knowledge and destination image to shape tourists’ pro-social intentions [9,18,34,35]. Existing research has underscored the ambivalent nature of tourists, who often express a willingness to support sustainability initiatives but also prioritize personal experiences and well-being [36,37]. Moreover, individuals carry both moral and hedonic tendencies, which shape their travel experiences in complex ways [9]. Despite these insights, there is limited understanding of how tourism sustainability and biospheric values interact to shape social engagement propensity among tourists.

To address this gap, the present study adopts the VBN theory [38] as the theoretical foundation for examining the psychological mechanisms underlying pro-social behavior in sustainable tourism [27]. The VBN theory proposes that individual values influence beliefs about environmental consequences, which in turn activate personal norms that drive pro-environmental behavior [39]. This framework has been widely used to explain pro-environmental behavior (PEB) in various contexts [40], but its application in eco-tourism settings, particularly in emerging economies, remains underexplored [32,41]. This study applies the VBN theory to investigate how tourism sustainability influences social engagement propensity among tourists, with a particular focus on the mediating roles of knowledge about the environment and eco-destination image, as well as the moderating role of biospheric value. Specifically, this research aims to address the following key questions:

- To what extent does tourism sustainability influence travelers’ social engagement propensity?

- How do knowledge about the environment and eco-destination image mediate the relationship between tourism sustainability and social engagement propensity?

- What role does biospheric value play in moderating the relationship between tourism sustainability and social engagement propensity?

By addressing these questions, this research extends VBN theory by incorporating social engagement as a pro-environmental behavioral outcome, contributing to a broader understanding of sustainable tourism behaviors. While prior studies have applied the VBN framework to consumer sustainability choices [27,36], this study applies the model to tourist engagement, knowledge acquisition, and destination perceptions—key components in driving long-term sustainability behaviors in tourism [35,42]. Furthermore, by examining how biospheric values moderate sustainable behavior outcomes, this study enhances the VBN model’s applicability to emerging tourism sustainability research, particularly in eco-tourism contexts [18,37,43,44]. The findings are expected to provide practical insights for policymakers and tourism managers on how to develop strategies that strengthen tourists’ pro-environmental engagement through knowledge dissemination, eco-friendly destination marketing, and value-driven sustainability programs. By empirically testing the VBN model’s hierarchical structure, this study seeks to provide a comprehensive understanding of the psychological mechanisms that drive sustainable tourism behaviors, ultimately contributing to the development of more resilient and sustainable tourism destinations.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the theoretical framework and hypothesis development, Section 3 outlines the research methodology, Section 4 discusses the data analysis and results, and Section 5 provides the implications, limitations, and recommendations for future research.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Value-Belief-Norm (VBN) Theory

The VBN Theory, developed by Stern et al. [38], provides a comprehensive framework for explaining PEB by emphasizing the hierarchical relationships between values, beliefs, and personal norms. The VBN model integrates Schwartz’s [45] value theory, the New Environmental Paradigm (NEP) [46,47], and the Norm Activation Model (NAM) [45] to explain how individuals’ values influence their environmental beliefs, which in turn activate personal norms that guide pro-environmental actions. In the tourism sector, the NEP framework has been widely used to assess individuals’ environmental worldviews and sustainability-related behaviors [27,48]. This perspective emphasizes minimizing environmental degradation, fostering respect for host cultures, and promoting the economic sustainability of tourism destinations [9].

The VBN theory extends the NAM by incorporating the influence of individual values (biospheric, altruistic, and egoistic) and ecological worldview (NEP) [32,49]. Biospheric values are particularly relevant in sustainable tourism, as they reflect individuals’ deep-seated concern for nature and the well-being of ecosystems [19,44]. These values influence tourists’ awareness of environmental consequences, their perceived responsibility to mitigate harm, and ultimately, their engagement in pro-environmental behaviors such as supporting sustainable tourism practices, engaging with eco-destinations, and actively contributing to conservation efforts [20,21,50].

The VBN theory has been extensively applied to explain sustainable consumer behaviors, such as mobility choices [51], eco-friendly accommodation preferences [52], risk recognition and willingness to accept responsibility [53], and pro-environmental travel decisions [32,54,55]. More recently, the VBN framework has been widely adopted in sustainable tourism research, including studies on environmentally conscious travel behaviors [56], sustainable cruise tourism [57], and air pollution reduction [58]. Despite its significance in sustainability research, few studies have applied the VBN model to examine social engagement propensity in tourism. Given that tourist engagement behaviors are influenced by environmental values, perceptions of destinations, and personal responsibility norms [8], the VBN framework is particularly well-suited for investigating how tourism sustainability translates into social engagement through knowledge about the environment and eco-destination image.

2.2. Tourism Sustainability

Tourism sustainability represents a multidimensional framework that addresses the environmental, social, and economic challenges of the global tourism industry [59]. In line with the VBN Theory [38], this study focuses on the environmental dimension of sustainability, conceptualizing sustainable tourism as behaviors that minimize harm to the environment [36]. Sustainable tourism behaviors are driven by individual values (biospheric, altruistic, and egoistic), beliefs (ecological worldview, awareness of consequences, and ascription of responsibility), and norms (personal obligations to act pro-environmentally) [49]. Within the tourism sector, sustainability initiatives encourage environmentally responsible behaviors such as choosing sustainable travel modes, staying in green hotels, conserving resources, and minimizing waste during travel [27].

The increasing recognition of sustainable tourism in both academia and practice reflects its role in aligning environmental conservation with economic and social benefits [36]. Sustainable tourism practices not only protect the environment but also enhance tourists’ willingness to support eco-friendly services and products, benefiting both public stakeholders and private businesses [23,24,27]. However, for sustainability initiatives to be effective, understanding the psychological mechanisms behind tourists’ sustainable behaviors is essential [35,60].

Research on sustainable tourism has largely focused on behavioral intentions as a predictor of actual sustainability behaviors [28]. While behavioral intention does not always translate into action, it is a key driver of pro-environmental behaviors in tourism settings [61]. Although actual sustainable behavior is difficult to measure directly, past research has examined pro-environmental behavioral patterns such as visits to eco-friendly attractions, participation in green activities, and purchasing sustainable accommodations [40]. In line with VBN theory, tourists’ sustainable behaviors are guided by their underlying values, beliefs about environmental consequences, and the moral obligation to act responsibly toward the environment [49].

For sustainability to be effective, social engagement in sustainability efforts should enhance the overall impact of sustainable tourism initiatives [9]. Community-based sustainability programs, eco-tourism experiences, and interactive sustainability education campaigns can reinforce tourists’ personal responsibility and commitment to sustainable behaviors [59]. In Cyprus, for example, tourism sustainability plays a crucial role in economic growth, employment generation, and investment attraction, while also promoting environmental preservation and cultural sustainability [11]. By integrating VBN theory, this study seeks to examine how tourism sustainability influences social engagement propensity through environmental knowledge and eco-destination image while considering biospheric values as a moderating factor.

2.3. Social Engagement Propensity

Social engagement propensity in tourism refers to an individual’s willingness to participate in tourism-related interactions and contribute to socially responsible behaviors [8]. This concept extends beyond individual tourist experiences to encompass broader societal and environmental engagement, making it an essential factor in sustainable tourism. In line with VBN theory [38], social engagement propensity is shaped by an individual’s values, beliefs, and personal norms, which influence their pro-social and pro-environmental behaviors. The integration of biospheric values, awareness of consequences, and perceived responsibility plays a crucial role in determining tourists’ willingness to engage in sustainability-oriented social exchanges [19,21].

Social engagement originates from social psychology, where it is conceptualized as a voluntary act that reflects moral values such as tolerance, respect, and social responsibility [9]. According to Shin et al. [62], social engagement is shaped by prior experiences and perceptions of social utility, influencing individuals’ decisions to engage in tourism activities that support environmental and social well-being. In the tourism context, Diallo et al. [8] provide empirical evidence that social engagement significantly drives responsible behavior, reinforcing the connection between sustainability values and tourists’ pro-environmental actions. In this study, social engagement propensity is conceptualized as a key behavioral outcome within the VBN model, reflecting tourists’ willingness to actively participate in sustainability initiatives through social interactions, environmental advocacy, and community involvement. Destinations that reinforce eco-friendly values through education and environmental messaging can increase tourists’ perceived responsibility and enhance their social engagement [7,25,63]. As a behavioral expression of internalized norms, social engagement is essential to sustaining responsible tourism ecosystems.

2.4. Tourism Sustainability and Social Engagement Propensity

Sustainable tourism fosters social engagement by encouraging responsible behaviors, enhancing interactions between tourists and local communities, and promoting eco-friendly practices [35]. When tourists perceive a destination’s sustainability initiatives as aligned with their personal values and beliefs, they are more likely to engage in community-based tourism activities, volunteerism, and conservation efforts [36]. According to the VBN model, tourists’ awareness of environmental consequences and their ascription of responsibility toward sustainability lead to stronger personal norms, which drive pro-social engagement behaviors [39,49]. In sustainable tourism settings, this translates into tourists actively participating in eco-tourism experiences, interacting with local communities, and supporting conservation initiatives [64]. These behaviors enhance their overall travel experience while simultaneously contributing to the long-term sustainability of destinations [7,9,62]. Based on the VBN model’s hierarchical structure, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H1:

Tourism sustainability has a positive impact on social engagement propensity.

2.5. Tourism Sustainability and Knowledge About the Environment

Tourism sustainability is closely linked to environmental knowledge, as informed tourists are more likely to adopt sustainable behaviors that minimize environmental degradation. Environmental knowledge plays a crucial role in ensuring that tourism minimizes harm to ecosystems while maximizing its educational and cultural benefits [65]. Knowledge about the environment enables tourists to identify sustainable travel options, adopt conservation behaviors, and make responsible choices regarding waste management, resource consumption, and interactions with local communities [14]. VBN theory suggests that knowledge acquisition is a belief-driven process, wherein tourists with heightened awareness of environmental consequences feel a moral obligation to engage in sustainability-supportive behaviors [36,49].

Furthermore, research highlights that environmental education enhances tourists’ ability to respond to climate-related challenges, adapt their behaviors, and contribute positively to sustainability efforts [66,67]. This aligns with VBN theory’s assumption that individuals must first recognize environmental challenges (awareness of consequences) before they feel a personal obligation to act sustainably (personal norms activation) [38]. As tourism sustainability initiatives expand, access to environmental knowledge becomes increasingly important, empowering tourists to engage in responsible decision-making that aligns with sustainability goals [36,68,69]. Based on the VBN framework, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H2:

Tourism sustainability has a positive impact on knowledge about the environment.

2.6. Knowledge About the Environment and Social Engagement Propensity

Knowledge about the environment plays a crucial role in shaping tourists’ social engagement propensity by fostering awareness, responsibility, and participation in sustainability initiatives. According to the VBN theory [38], individuals with a strong ecological worldview and awareness of environmental consequences are more likely to develop personal norms that drive pro-social and pro-environmental behaviors [19,21,70]. In tourism, this means that tourists who are well-informed about environmental issues are more inclined to engage in sustainability-driven social interactions, contribute to conservation efforts, and participate in eco-friendly tourism activities [36,62]. Environmental knowledge not only influences individual sustainability decisions but also encourages collective action within tourism destinations. It enhances entrepreneurial opportunities in sustainable tourism, attracts eco-conscious investors, and motivates businesses to integrate sustainability into tourism services [67,71,72]. Additionally, understanding the environmental dynamics of specific regions helps stakeholders make informed decisions regarding tourism sustainability while reinforcing tourists’ commitment to environmental responsibility [9,73]. The integration of sustainability awareness into tourism experiences also strengthens social engagement propensity, as tourists who recognize the impact of their behaviors on the environment are more likely to interact with local communities, support eco-tourism initiatives, and advocate for responsible tourism practices [63]. By linking environmental knowledge with sustainable engagement behaviors, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H3:

Knowledge about the environment has a positive impact on social engagement propensity.

2.7. Tourism Sustainability and Eco-Destination Image

Tourism sustainability significantly influences the eco-destination image, shaping tourists’ perceptions of a destination’s environmental commitment [18,74]. The VBN theory [38] explains how individual values and beliefs about sustainability shape their attitudes toward eco-friendly destinations. An eco-destination image represents tourists’ perceptions of a destination’s environmental quality, sustainability initiatives, and conservation efforts [18]. Positive perceptions are reinforced when destinations prioritize eco-friendly tourism practices, ensuring minimal environmental impact while enhancing visitor experiences [17]. Travelers evaluate eco-destination image based on cultural customs, local sustainability efforts, and environmental preservation, particularly in European island destinations such as Cyprus [75]. Sustainable tourism initiatives enhance eco-destination image by integrating nature conservation, green infrastructure, and responsible tourism policies, ultimately influencing tourist satisfaction, revisit intentions, and destination loyalty [74,76]. In line with VBN theory, as tourists become aware of a destination’s sustainability efforts and perceive their travel choices as impactful, their personal norms activate pro-environmental behaviors, reinforcing their preference for eco-friendly destinations [36]. Given the role of sustainability in shaping tourists’ perceptions and reinforcing destination competitiveness [77,78], this study proposes:

H4:

Tourism sustainability has a positive impact on the eco-destination image.

2.8. Eco-Destination Image and Social Engagement Propensity

A destination’s eco-destination image significantly shapes tourists’ social engagement propensity by influencing their perceptions of sustainability, community interaction, and environmental responsibility. The VBN theory [38] explains how individuals’ sustainability values and beliefs influence their engagement in social behaviors, particularly in eco-friendly tourism settings [32,44,52,56]. Travelers who perceive a destination as environmentally responsible are more likely to develop a sense of moral obligation to support its sustainability initiatives and engage in pro-social behaviors [36]. A strong eco-destination image enhances tourists’ willingness to interact with local communities, participate in conservation activities, and support sustainable tourism efforts [30,79]. As social engagement is critical to tourism sustainability, destinations that align with eco-conscious travelers’ expectations foster higher engagement, satisfaction, and destination loyalty [62,80]. Moreover, a positive eco-destination image encourages word-of-mouth advocacy, further reinforcing sustainability engagement among future visitors [33,77,78]. Given the role of eco-destination image in driving sustainable social interactions, this study proposes:

H5:

Eco-destination image has a positive impact on social engagement propensity.

2.9. The Mediating Role of Knowledge About the Environment

Environmental knowledge is a key driver of pro-environmental behavior in tourism, influencing tourists’ ability to make sustainable decisions and engage in environmentally responsible activities. In this context, knowledge about the environment serves as a crucial mechanism linking tourism sustainability to social engagement propensity, as it enhances tourists’ awareness of sustainability issues and their responsibility toward environmental preservation [36]. Environmental knowledge encompasses awareness of ecological conditions, conservation strategies, and sustainable practices, enabling tourists to make informed choices that align with sustainable tourism principles [81,82]. Research suggests that tourists with higher environmental knowledge are more likely to engage in responsible tourism behaviors, actively participate in conservation efforts, and adopt sustainable practices in their travel experiences [14]. This aligns with VBN theory, which posits that as individuals become more aware of environmental consequences, their sense of personal obligation to engage in sustainability-driven behaviors strengthens [49].

In eco-tourism destinations such as Cyprus, tourism sustainability is heavily reliant on natural scenery, favorable climatic conditions, and high-quality tourism services, all of which are enhanced by tourists’ environmental awareness [4,83,84]. As sudden environmental changes become more prevalent, knowledge about the environment empowers tourists to navigate risks, adopt precautionary measures, and make sustainability-oriented travel decisions [6,16]. By fostering greater environmental awareness, knowledge about the environment strengthens the relationship between tourism sustainability and social engagement propensity, ensuring that tourists actively contribute to sustainability initiatives while fulfilling their travel expectations [63,85]. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H6:

Environmental knowledge positively mediates the relationship between tourism sustainability and social engagement propensity.

2.10. The Mediating Role of Eco-Destination Image

The eco-destination image serves as a crucial determinant of tourists’ behavioral decisions, particularly in sustainable tourism contexts. A strong eco-destination image reinforces tourists’ belief in sustainability efforts, leading to higher levels of social engagement propensity as they feel a moral obligation to contribute to the environmental and social well-being of the destination [36]. A positive eco-destination image fosters greater tourist satisfaction, encourages repeat visits, and enhances overall destination loyalty [30,74,76]. Tourists who perceive a destination as environmentally responsible are more likely to engage in pro-sustainability behaviors, supporting community-driven conservation initiatives and eco-tourism programs [86,87]. Furthermore, the eco-destination image acts as a psychological bridge, reinforcing the connection between tourism sustainability and social engagement propensity, as tourists who recognize a destination’s sustainability efforts are more inclined to interact with local communities and participate in eco-friendly tourism experiences [88,89]. By shaping tourists’ perceptions and expectations, a strong eco-destination image amplifies the impact of tourism sustainability on social engagement propensity, ensuring that sustainability efforts translate into meaningful and lasting visitor engagement [18]. Based on this understanding, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H7:

Eco-destination image positively mediates the relationship between tourism sustainability and social engagement propensity.

2.11. The Moderating Role of Biospheric Value

Biospheric values (BV) play a crucial role in shaping individuals’ environmental beliefs and behaviors, particularly in sustainable tourism contexts. According to the VBN theory [38], values influence individuals’ awareness of environmental consequences, which in turn activate personal norms that drive pro-environmental behaviors [19]. Among the three key values identified by Stern [49]—biospheric, altruistic, and egoistic—biospheric values prioritize environmental protection and the preservation of ecosystems, making them highly relevant to sustainable tourism [18]. Tourists who strongly identify with biospheric values are more likely to assess destinations based on environmental sustainability, respond proactively to environmental changes, and engage in responsible tourism behaviors [37]. These values moderate the relationship between tourism sustainability and its key behavioral outcomes, as they influence how tourists interpret knowledge about the environment, eco-destination image, and social engagement propensity [90,91].

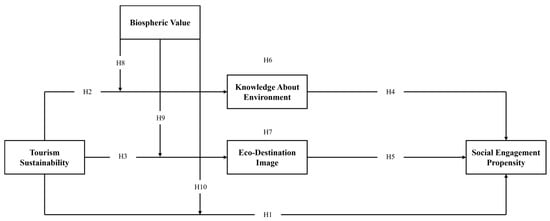

Individuals with high biospheric values are more likely to seek, process, and apply environmental knowledge, strengthening the link between tourism sustainability and awareness of environmental issues [18]. In contrast, those with low biospheric values may not internalize sustainability information as deeply, resulting in a weaker relationship [92]. For example, the influence of tourism sustainability on eco-destination image depends on tourists’ value orientations. Those with strong biospheric values evaluate destinations based on sustainability efforts and conservation initiatives, reinforcing the destination’s eco-friendly reputation [41,90]. However, for tourists with low biospheric values, the impact of sustainability initiatives on eco-destination image may be less pronounced [18]. Tourists with high biospheric values feel a stronger moral obligation to engage in sustainability-related social interactions, making them more likely to participate in conservation programs, community-based tourism, and eco-tourism activities [37,44,93]. Conversely, those with low biospheric values may not perceive social engagement in sustainability as a personal responsibility, weakening the effect of tourism sustainability on social engagement propensity [20,31]. Based on the VBN framework and the moderating role of biospheric values (Figure 1), the following hypotheses are proposed:

Figure 1.

Research model.

H8:

Biospheric values moderate the relationship between tourism sustainability and knowledge about the environment, with the positive relationship being stronger among tourists with high biospheric values compared to those with low biospheric values.

H9:

Biospheric values moderate the relationship between tourism sustainability and eco-destination image, with the positive relationship being weaker among tourists with low biospheric values.

H10:

Biospheric values moderate the relationship between tourism sustainability and social engagement propensity, with the positive relationship being stronger among tourists with high biospheric values compared to those with low biospheric values.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Site

The study was conducted in Northern Cyprus, a region recognized for its unique blend of natural beauty and cultural heritage, making it a popular destination for tourists from various countries. Cyprus, the third-largest island in the Mediterranean, has a rich history of mass tourism that began in the 1960s, despite internal political challenges [22,94,95]. In Northern Cyprus, tourism development followed a distinct trajectory after the Turkish intervention in 1974, which partitioned the island into Turkish and Greek sectors [1,2,4].

The Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) has developed a robust tourism industry, contributing significantly to its economy with a 30.7% share of the GDP in 2022, with 1.9 million tourists visiting in 2023 [96]. The study sites included the cities of Kyrenia, Famagusta, and Nicosia, which are notable for their rich history, natural landscapes, and heritage tourism, attracting millions of tourists annually [13,97]. These destinations are also at the forefront of sustainable tourism development, aligning with the broader goals of ecological protection and local economic development [2,98]. By focusing on these key areas, this study offers valuable insights into the role of tourism sustainability in shaping tourists’ social engagement propensity behavior.

3.2. Data Collection

To examine the research objectives and test the hypotheses, a quantitative research design was employed using cross-sectional data collected via self-administered questionnaires. This approach, well-regarded in social sciences for its efficiency in gathering structured data from diverse populations [99,100,101], was applied to tourists in Kyrenia, Famagusta, and Nicosia, key destinations in Northern Cyprus [102]. The data collection spanned three months and involved face-to-face distribution of questionnaires, utilizing a convenience sampling method to ensure broad participation from tourists with varying experiences [103]. Before responding, participants were briefed on the study’s goals, with only voluntary respondents completing the survey. Of the 623 distributed questionnaires, 432 were returned, and after eliminating incomplete responses, 396 valid questionnaires remained, resulting in a response rate of 63.5%. This robust dataset provides a reliable foundation for investigating the relationship between eco-destination image, environmental knowledge, biospheric values, and tourists’ social engagement behaviors.

3.3. Construct Measurements

To ensure the robustness and precision of the measurement instruments used in this study, a multi-stage validation process was undertaken. First, the questionnaire was carefully reviewed by academicians and practitioners to ensure the content validity of the measurement items. The back-translation technique was employed to maintain linguistic and contextual accuracy, wherein professional bilingual experts translated the original English version into Turkish and then back into English [104,105,106]. This process helped to verify the equivalence of meaning and ensure that the items remained consistent across languages [107]. The final Turkish version was also reviewed by local tour operators who provided valuable feedback, contributing to the refinement of the instrument.

Prior to formal data collection, a pre-test was conducted to assess the clarity and usability of the measurement items. Five tourism management professors provided feedback on the wording, layout, and comprehensibility of the questionnaire, leading to revisions that enhanced the clarity of the items. Subsequently, a pilot test was conducted with a sample of 30 tourists in Northern Cyprus using a convenience sampling method. The results of this pilot study were analyzed to evaluate the reliability and validity of the constructs. Cronbach’s alpha values for all latent variables exceeded 0.700, indicating good internal consistency and reliability [108]. Moreover, the standard factor loadings for all items were greater than 0.500 and significant at the 0.001 level, demonstrating strong construct validity [109].

In line with the rigor expected in tourism research, the constructs used in this study were measured using multi-item, 5-point Likert scales, ranging from Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (5). Tourism sustainability was measured using 10 items drawn from previous studies [110,111]. Eco-destination image was assessed with four items adapted from well-established scales [18,74,112]. Knowledge about the environment was measured using three items from Choi and Johnson’s [113] work. The construct of biospheric value was captured using four items from recent studies [19,31,91]. Finally, tourists’ social engagement propensity behavior was measured with four items adapted from Diallo et al. [8]. These multi-item measures ensured a comprehensive assessment of each construct, facilitating robust statistical analysis in the subsequent stages of the research.

4. Analysis and Results

To analyze the data and test the hypothesized relationships, this study utilized a comprehensive statistical procedure. Descriptive statistics and reliability analysis were first conducted using SPSS version 23. The data’s normality was assessed, with skewness values ranging from −1.006 to 1.201 and kurtosis values between −0.969 and 4.874, all falling within acceptable limits, confirming that the assumption of normal distribution was not violated [114,115]. The demographic profiles of the respondents and internal consistency of the study constructs were also analyzed using SPSS. For hypothesis testing, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was performed using Amos version 26, following a two-step approach [116]. First, the measurement model was assessed to confirm the reliability and validity of the constructs, followed by an evaluation of the structural model. The bootstrapping method with 5000 subsamples was applied to ensure the significance of factor loadings and path coefficients [117].

4.1. Respondent Profile

In terms of gender distribution, 59.1% of the respondents were male, while 40.9% were female. Age-wise, the majority of the respondents were between 40 and 50 years old (40.9%), followed by those aged 29–39 years (37.9%). Educational attainment was notably high, with 68.7% holding undergraduate or graduate degrees. Geographically, the sample was primarily drawn from Kyrenia (57.6%), followed by Famagusta (27.5%) and Nicosia (14.9%). Additionally, a higher percentage of respondents were single (56.6%) compared to married individuals (37.9%). For a more comprehensive breakdown of these characteristics, refer to Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic profile of the respondents.

4.2. Common Method Variance

To address concerns related to common method variance (CMV), a critical issue in studies relying on self-reported data, we implemented both procedural and statistical remedies [118]. As recommended by Podsakoff et al. [119], ensuring respondent anonymity and confidentiality was a key procedural step in this study. This approach encourages more truthful responses by minimizing the respondents’ apprehension about how their data might be used, thereby reducing the likelihood of bias [120]. Statistically, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted to detect the presence of CMV. The results of the unrotated factor analysis revealed five distinct factors, together explaining 65.45% of the total variance. The first factor accounted for only 33.849% of the variance, which is well below the 50% threshold commonly used to indicate problematic CMV [119]. These findings suggest that CMV is not a significant issue in this study, confirming the robustness of the data and its findings.

4.3. Assessment of the Measurement Model

The assessment of the measurement model demonstrates that it fits the data well, as evidenced by the fit indices shown in Table 2, which meet the acceptable standards based on Hu and Bentler’s [121] model evaluation criteria. To validate the model, reliability of the constructs was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability scores, as outlined in Table 3. The Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.783 to 0.926, comfortably exceeding the minimum threshold of 0.700 [108], indicating acceptable internal consistency across the constructs. Furthermore, composite reliability scores, which ranged from 0.794 to 0.936, confirmed the reliability of the measurement items [117]. Table 3 shows that all constructs met the reliability threshold, supporting the internal consistency of the measurement model.

Table 2.

Fit indices of the measurement model.

Table 3.

Reliability and convergent validity analysis.

Convergent validity, which reflects how well the items measure the constructs they are intended to represent, was also confirmed. As shown in Table 3, all factor loadings exceeded the threshold of 0.689 and were statistically significant at the 0.001 level [109]. Additionally, the average variance extracted (AVE) values for the constructs ranged between 0.548 and 0.612, surpassing the minimum recommended value of 0.500 [122], which further indicates sufficient convergent validity [123]. These findings confirm that the indicators consistently represent their respective latent constructs.

To evaluate discriminant validity, which ensures that the constructs are distinct from one another, the square roots of the AVEs were compared with the correlation coefficients between each pair of constructs [122]. Table 4 shows that the square roots of the AVEs were greater than the corresponding correlations, thus confirming that discriminant validity was achieved [124]. This means the constructs in the model are uniquely measured, without significant overlap, ensuring the robustness and clarity of the measurement model.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity.

4.4. Evaluation of the Structural Model

The structural model evaluation demonstrated a good fit with the data, as indicated by several fit indices: χ2/df = 1.34, CFI = 0.99, NFI = 0.98, IFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.93, SRMR = 0.03, and RMSEA = 0.05. According to Hu and Bentler’s [121] guidelines, these values suggest the structural model sufficiently represents the relationships among the variables. The model’s ability to explain the hypothesized relationships is confirmed through these fit indices, reflecting its robustness and validity for further interpretation [125].

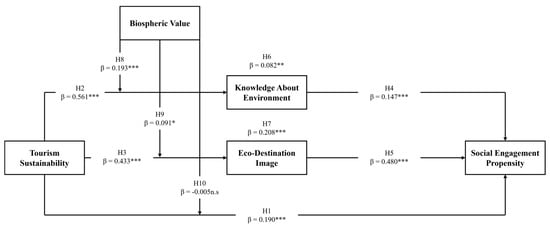

Table 5 presents the detailed results of the hypothesis testing within the structural model. The findings reveal that tourism sustainability had a significant positive impact on social engagement propensity (β = 0.190, p < 0.001), supporting H1. Additionally, knowledge about the environment (β = 0.561, p < 0.001) and eco-destination image (β = 0.433, p < 0.001) are both significantly influenced by tourism sustainability, supporting H2 and H3, respectively. Furthermore, knowledge about the environment also showed a significant positive effect on social engagement propensity (β = 0.147, p < 0.001), thereby supporting H4. Finally, eco-destination image demonstrated a positive effect on social engagement propensity (β = 0.480, p < 0.001), providing evidence for H5. These relationships are visually represented in Figure 2, which depicts the structural model’s pathway diagram.

Table 5.

Results of the structural model test.

Figure 2.

Structural model pathway diagram and hypothesis testing results. Note(s): *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.010, * p < 0.050, n.s. insignificant.

4.5. Mediation Analysis

To assess the mediating roles of knowledge about the environment and eco-destination image in the relationship between tourism sustainability and social engagement propensity, a two-step mediation analysis was conducted using the bootstrapping method recommended by Preacher and Hayes [126]. This approach, using 5000 resamples with a 95% confidence interval (CI), is particularly effective in detecting indirect effects in mediation models [127]. We employed the bootstrapping percentile method available in AMOS version 26 to execute the simple mediation analysis [128]. The results of H6 demonstrated that knowledge about the environment significantly mediates the relationship between tourism sustainability and social engagement propensity. Specifically, tourism sustainability exhibited a significant indirect effect on social engagement propensity through environmental knowledge, with a standardized indirect effect of β = 0.082 ** (LB = 0.052, UB = 0.154), supporting H6.

Furthermore, the mediation analysis confirmed the role of eco-destination image as a mediator in the relationship between tourism sustainability and social engagement propensity. As shown in Table 6, the indirect relationship between these variables is statistically significant, with eco-destination image positively mediating the effect (β = 0.208 ***, LB = 0.201, UB = 0.346), thus providing support for H7. These findings suggest that both knowledge about the environment and eco-destination image are crucial mechanisms through which tourism sustainability enhances tourists’ propensity for social engagement. The mediation effects are graphically illustrated in Figure 2, further underscoring the strength of the indirect pathways.

Table 6.

Results of indirect and interaction effect test.

4.6. Moderation Effect Test

To assess whether biospheric value moderates the relationships between tourism sustainability and the variables of knowledge about the environment, eco-destination image, and social engagement propensity, a moderation analysis was conducted. Due to concerns about multicollinearity between interaction terms, each moderating effect of biospheric value was tested separately [129,130]. The results from the direct effect analysis indicated that biospheric value significantly impacts both knowledge about the environment (β = −0.173, t = −5.031, p < 0.001) and eco-destination image (β = 0.241, t = 9.210, p < 0.001), but not social engagement propensity (β = 0.038, t = 1.144, n.s.).

However, the interaction effect analysis demonstrated that biospheric value significantly moderates the relationships between tourism sustainability and both knowledge about the environment (β = 0.193, p < 0.001) and eco-destination image (β = 0.091, p < 0.050). These findings support H8 and H9, indicating that biospheric value strengthens the positive effects of tourism sustainability on both knowledge about the environment and eco-destination image. In contrast, no significant moderating effect was found for the relationship between tourism sustainability and social engagement propensity (β = −0.005, n.s.), leading to the rejection of H10.

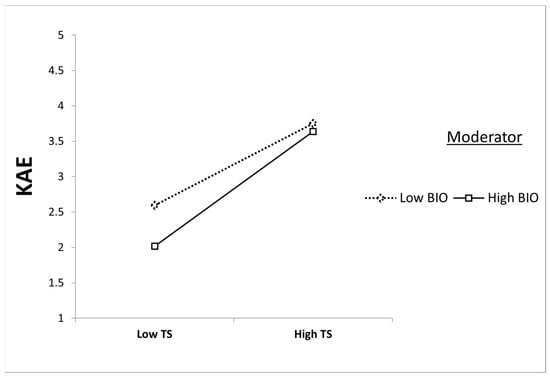

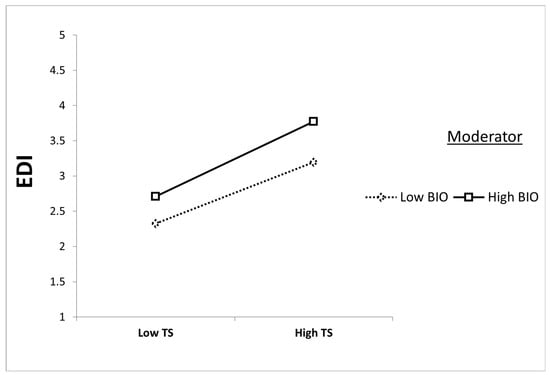

The overall moderation results are detailed in Table 6 and visually represented in Figure 3 and Figure 4. Specifically, Figure 3 shows that biospheric value enhances the positive relationship between tourism sustainability and knowledge about the environment—this relationship is notably stronger among tourists with high biospheric values. Similarly, Figure 4 illustrates that the relationship between tourism sustainability and eco-destination image is also stronger among tourists with higher biospheric values. These findings highlight the critical role of biospheric values in moderating how tourists perceive both environmental knowledge and eco-destination image within the context of sustainable tourism.

Figure 3.

Moderating effect of biospheric value on the tourism sustainability and knowledge about the environment relationship.

Figure 4.

Moderating effect of biospheric value on the tourism sustainability and eco-destination image relationship.

4.7. Explanatory Power of the Structural Model

The explanatory power of the structural model was assessed using R2 values, which indicate how well the model accounts for the variance in the endogenous variables [131]. The results show that the model explained 32.2% of the variance in knowledge about the environment, 50.8% in eco-destination image, and 53.8% in social engagement propensity. According to Cohen’s [131] thresholds, these R2 values demonstrate a large explanatory power. These findings suggest that the model has a strong ability to explain the relationships between the constructs.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study advances the theoretical application of the VBN theory in the tourism domain by examining how tourism sustainability influences tourists’ social engagement propensity through the mediating mechanisms of environmental knowledge and eco-destination image and the moderating role of biospheric value. Guided by the VBN framework [21,38], which posits that individuals’ environmental behaviors are shaped by their values, beliefs, and personal norms, the findings of this study offer novel insight into how value-driven psychological processes inform sustainable tourist behavior. The results reaffirm the significance of biospheric-oriented values and ecological worldviews in activating pro-social and pro-environmental actions in tourism settings, thereby enriching our theoretical understanding of sustainability engagement.

5.1. Discussion of Key Findings

The study’s first major finding supports H1, confirming that tourism sustainability positively influences social engagement propensity. This supports the VBN model’s assertion that individuals who recognize the sustainability value of a destination are more inclined to engage socially through pro-environmental behavior [36,49]. Consistent with prior research, such as Lee and Jan [132] and Stylidis et al. [133], tourism sustainability efforts have been shown to foster a sense of community connection and participatory behaviors, validating its impact on social engagement. This aligns with earlier tourism studies demonstrating that sustainability practices promote community interaction and responsibility [8,134]. While sustainable tourism has been extensively examined in Asian [135] and Western contexts [136], limited attention has been given to Mediterranean destinations like Northern Cyprus, where socio-cultural factors may influence sustainability perceptions and engagement behaviors differently. This underscores the need for cross-cultural research that includes underrepresented regions in environmental psychology [137,138,139,140].

H2 and H3 were also supported, revealing that tourism sustainability enhances tourists’ knowledge about the environment and eco-destination image. This aligns with the VBN theory’s belief component, where awareness of environmental consequences is shaped by contextual cues such as visible sustainable practices [68,81]. The more tourists encounter sustainability-oriented efforts, the more obligated they feel to acquire relevant environmental knowledge [14,69]. This is in line with findings from Chen and Tung [141] and Woosnam et al. [142], who reported that sustainable initiatives significantly contribute to tourists’ environmental cognition and their evaluative perceptions of destinations. These results suggest that sustainability messages embedded within the tourism experience effectively activate cognitive engagement among visitors.

Furthermore, support for H4 and H5 indicates that knowledge about the environment and eco-destination image significantly fosters social engagement propensity. According to VBN, such knowledge reinforces ascription of responsibility, which in turn activates personal norms that guide pro-social behavior [19,67]. This finding resonates with previous research showing that informed tourists are more inclined to support green initiatives and actively participate in local sustainability efforts [9,143]. Recent studies [14,29,144,145,146,147] also show that image-based and knowledge-driven perceptions of ecological destinations contribute to heightened behavioral engagement, indicating that cognitive and perceptual factors jointly shape tourists’ social actions.

In terms of mediation, the confirmation of H6 demonstrates that environmental knowledge mediates the relationship between sustainability and social engagement. This sequential process is aligned with the VBN model, wherein value-based awareness precedes the formation of personal norms, which then lead to behavior [14,49]. This finding adds to previous literature on pro-environmental behavior by reinforcing the pivotal role of knowledge as a cognitive bridge between sustainability values and actual behavioral expressions [26,27,28,40]. Similarly, H7 was supported, showing that eco-destination image mediates the influence of tourism sustainability on social engagement. This affirms the notion that when travelers perceive a destination as authentically eco-friendly, it positively shapes their ecological worldview—an important belief structure in the VBN model [30,89]. These results complement findings by Liu et al. [77] and others [74,79], who identified destination image as a key mediator that translates tourists’ perceptions into sustainable behavioral intentions.

With regard to the moderating role of biospheric values, the results confirmed H8 and H9, demonstrating that these values amplify the effects of tourism sustainability on environmental knowledge and eco-destination image. This supports earlier studies showing that individuals with strong biospheric values are more responsive to environmental cues and internalize sustainability messaging more deeply [90,91]. As Luong [18] observed, biospheric values enhance the personal relevance of ecological information, thereby boosting both cognitive and emotional engagement. These findings extend the VBN framework by emphasizing how personal values condition the strength of sustainability’s cognitive effects.

However, H10 was not supported, indicating that biospheric values do not significantly moderate the relationship between tourism sustainability and direct social engagement behavior. This contrasts with studies that identified strong direct links between values and behavior [19,90,148]. One possible explanation is that while biospheric values enhance awareness and perceptions, they may require additional emotional, motivational, or situational triggers to influence overt behavior. This suggests that the link between values and engagement may depend on intervening variables such as emotional attachment, place identity, or perceived behavioral control, which were not measured in this model [20,93]. This nuanced finding contributes to the theoretical refinement of the VBN model, highlighting potential gaps between belief systems and behavioral manifestations.

Taken together, these findings contribute to a broader understanding of how sustainable tourism influences tourist behavior through multiple cognitive and perceptual pathways. By integrating both mediation and moderation mechanisms, the current study offers a more comprehensive model of tourist engagement that incorporates value-based processing, belief formation, and perceptual framing. The application of the VBN theory to a Mediterranean eco-destination context also adds to the cross-cultural body of environmental psychology, suggesting that while foundational mechanisms may be stable, the strength and form of these relationships can differ across socio-cultural settings.

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

This study makes significant theoretical contributions by extending the VBN theory into the sustainable tourism context. By integrating constructs such as tourism sustainability, knowledge about the environment, eco-destination image, biospheric values, and social engagement propensity, the research provides a comprehensive application of VBN to explain pro-environmental tourist behavior. This responds directly to calls in the literature for broader contextual applications of VBN in emerging tourism economies and nature-based destinations [32,36].

Theoretically, this study extends the VBN model by incorporating eco-destination image as a key evaluative belief, revealing a novel pathway to social engagement in tourism behavior. First, this study advances the VBN framework by demonstrating how environmental values (biospheric), ecological beliefs (eco-destination image and environmental knowledge), and personal norms (social engagement propensity) work in a sequential and interdependent manner to explain sustainable behavior among tourists. This contributes to a more detailed understanding of the value → belief → norm chain within an eco-tourism context, operationalizing the VBN model more explicitly than prior tourism studies. While prior studies have applied VBN to examine behavior in domains such as transportation [58], lodging [52], and protected areas [149], few have fully tested the causal chain of VBN in a tourism engagement setting. This study fills that gap by showing how environmental knowledge and destination perceptions mediate the value–norm–behavior linkage, reinforcing the explanatory power of VBN beyond intention to include socially engaged pro-tourism behavior [19,27,49]. Moreover, this theoretical refinement addresses emerging debates about how different belief types interact with value structures in environmentally sensitive domains such as tourism [14].

Second, the study contributes theoretically by reconceptualizing social engagement propensity as an expression of activated personal norms within the VBN model. Whereas past research framed social engagement from behavioral or psychological perspectives [8], this study positions it as the normative outcome of a belief system triggered by values and beliefs about tourism sustainability. In doing so, it provides a novel extension of VBN theory, highlighting that social interaction and community participation are not just behavioral outputs but norm-based responses to environmental concern. This reconceptualization enriches theoretical understandings of how social dimensions of sustainability are inherently tied to internalized value systems [62].

Third, this study expands the role of eco-destination image as a cognitive belief construct within the VBN chain. Although earlier studies have emphasized its influence on destination choice and loyalty [76,89], its theoretical role within environmental value systems has remained underexplored. By introducing eco-destination image as an evaluative belief that directly links sustainability values to social behavior, the study adds depth to belief formation processes within the VBN theory. By demonstrating that eco-destination image mediates the relationship between sustainability values and engagement behaviors, the study positions it as a vital belief component that influences both awareness of environmental consequences and the ascription of responsibility—core beliefs in the VBN framework [36,38]. This refinement highlights the dynamic interaction between affective and cognitive evaluations in sustainability-driven decision-making [133,142,144,147].

Fourth, the inclusion of biospheric value as a moderator enriches VBN theory by accounting for variations in the strength of belief-behavior relationships. While biospheric values have often been treated as antecedents [21,37,43,44], this study reveals that they also condition the effects of sustainability perceptions on environmental knowledge and eco-destination image. This adds theoretical nuance, suggesting that the salience of sustainability-related cues is amplified among those with stronger biospheric orientations [90,91], aligning with recent efforts to refine VBN’s predictive scope. This moderating insight extends current understandings of value-salience models, emphasizing that internal values not only initiate belief systems but also strengthen the responsiveness to environmental messaging [18,150].

Lastly, the study contributes to ongoing theoretical development by applying VBN in the context of a nature-based destination in an emerging economy, where cultural, ecological, and infrastructural dynamics differ from those in previously studied Western contexts. This helps address the call for context-specific validation of pro-environmental behavior models [28,32,137,138,151,152], particularly in regions such as Northern Cyprus, where tourism’s environmental and economic impacts are intertwined. The application of VBN in this socio-ecological setting demonstrates the model’s adaptability across cultural and developmental contexts, offering new directions for global sustainability scholarship. Furthermore, this cross-cultural application advances environmental psychology by demonstrating that VBN pathways remain robust even under different socio-cultural structures [153].

In sum, this research reaffirms the utility of VBN theory in predicting sustainable behavior in tourism and offers a theoretically grounded, context-sensitive framework for understanding how values, beliefs, and personal norms interact to shape tourists’ socially engaged, sustainability-driven actions.

5.3. Managerial Implications

This study offers several critical managerial implications for stakeholders aiming to enhance sustainable tourism practices. Anchored in the VBN theory, the findings suggest that tourism managers must formulate strategies that foster environmental values, cultivate ecological beliefs, and activate tourists’ personal norms toward sustainability. First, the results underscore the importance of promoting environmental knowledge as a cognitive foundation supporting pro-environmental decision-making. As knowledge about the environment mediates the relationship between tourism sustainability and social engagement, tourism operators should develop educational interventions such as guided eco-tours, sustainability workshops, or digital storytelling tools to raise tourists’ awareness of environmental challenges and conservation efforts [16,36]. Tourism authorities and eco-park managers could further implement structured environmental education campaigns, incorporating interactive exhibits and gamified learning experiences to emphasize local biodiversity and conservation practices. These initiatives are likely to activate awareness of consequences and ascription of responsibility—two key belief components in the VBN chain—thereby fostering a sense of moral obligation to engage in sustainable behaviors [21,81].

Second, the findings highlight the strategic importance of curating a strong eco-destination image to influence tourists’ perceptions and behaviors. As the eco-destination image was shown to both mediate and reinforce sustainable behavioral outcomes, managers should integrate sustainability narratives into destination branding and communication. This can include visual storytelling, user-generated green content, and certifications (e.g., eco-labels for accommodations or attractions) that visibly demonstrate environmental responsibility [76,89]. Destination marketing strategies led by tourism boards should emphasize success stories in conservation, community-driven eco-projects, and low-carbon infrastructure to enhance appeal among eco-conscious travelers. Such strategies help strengthen tourists’ ecological worldviews, thereby contributing to belief formation in the VBN model [49].

Third, social engagement propensity—interpreted in this study as an activated personal norm within the VBN framework—emerges as a behavioral endpoint that managers can stimulate through participatory programs. Community-based tourism projects, environmental volunteering opportunities, and cultural immersion initiatives can reinforce personal moral obligations and deepen tourists’ psychological engagement with sustainability goals [8,63]. Eco-park managers and community leaders could design programs encouraging visitors to participate in reforestation efforts, marine conservation activities, or local heritage preservation projects, thereby embedding pro-environmental norms into the tourist experience. Such engagement is not only beneficial for local communities but also enhances tourists’ emotional satisfaction and destination loyalty.

Fourth, the moderating role of biospheric values suggests that sustainability initiatives should be tailored to tourists’ environmental orientations. Tourism businesses should conduct psychographic segmentation to identify visitors with high biospheric values and design targeted experiences aligned with their concern for nature—such as low-impact tourism, biodiversity protection initiatives, or carbon-offset programs [18,91]. Additionally, integrating local biospheric values and traditional ecological knowledge into tourism product development can enhance authenticity and deepen tourists’ value alignment [20,31]. Policymakers can support such initiatives by offering incentives for tourism businesses that promote culturally rooted and environmentally respectful experiences, thereby encouraging broader industry-wide adoption of biosphere-sensitive practices.

Finally, tourism managers and policymakers should holistically consider the VBN framework—values, beliefs, and norms—in designing interventions that not only inform and attract eco-conscious travelers but also foster enduring behavior change. Strategic collaborations among public tourism authorities, NGOs, and private sector operators could facilitate the systemic application of VBN principles across marketing, visitor management, and sustainability certification programs. By cultivating a value-driven tourism experience that integrates education, image, engagement, and value alignment, destinations such as Northern Cyprus can position themselves as leaders in sustainable tourism.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

While this study advances the application of the VBN theory in sustainable tourism, several limitations offer avenues for future research. First, the sample predominantly consisted of older tourists, whose biospheric values and pro-environmental behaviors may differ from those of younger cohorts. Future research should aim for a more balanced demographic profile by including younger tourists to enhance external validity and better capture generational variations in sustainability engagement [152,153]. Second, the use of cross-sectional data limits causal inference, highlighting the need for longitudinal research designs that can trace how environmental beliefs, personal norms, and engagement propensities evolve over time. Third, this study did not examine emotional or affective drivers, such as place attachment or moral obligation, which could further enrich understanding of norm activation within the VBN framework. Future studies should also investigate other potential mediators and moderators—including emotional attachment, cultural norms, or digital media influence—that may shape pro-social engagement behaviors. Fourth, although the conceptual distinction between eco-destination image and environmental knowledge was theoretically justified, the cognitive overlap between these constructs suggests a need for further qualitative validation through interviews or focus groups.

Additionally, the reliance on convenience sampling and self-reported measures introduces potential biases, notably social desirability bias, as tourists may overstate their environmental engagement to align with perceived norms. To address this, future research could employ mixed-methods approaches or incorporate behavioral measures. As digital technologies increasingly influence tourists’ environmental awareness and behaviors, examining the role of eco-apps, augmented reality, and digital engagement tools could provide important insights into belief formation and social engagement processes. Finally, applying and testing the proposed model across culturally diverse destinations would strengthen generalizability and reveal context-specific dynamics, contributing both to theory development and to sustainable tourism practices.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, S.A.; formal analysis, H.Y.A.; supervision, H.Y.A.; validation, H.Y.A. and S.A.; writing—review and editing, S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the University of Mediterranean Karpasia.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants in this study provided their informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

The data from this study can be requested from the corresponding author, Sana Alashiq.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alipour, H.; Kilic, H. An Institutional Appraisal of Tourism Development and Planning: The Case of the Turkish Republic of North Cyprus (TRNC). Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atun, R.A.; Nafa, H.; Türker, Ö.O. Envisaging Sustainable Rural Development through ‘Context-Dependent Tourism’: Case of Northern Cyprus. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2019, 21, 1715–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guden, N.; Girgen, M.U.; Saner, T.; Yesilpinar, E. Barriers to Sustainable Tourism for Small Hotels in Small Island Developing States and Some Suggested Remedies. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2021, 13, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ince, E.; Öztüren, A. Strengths, Weaknesses and Challenges of Municipalities in North Cyprus Aspiring to Be a Sustainable Cittaslow Tourism Destination. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2021, 13, 528–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandcourt, M.-A.E. The Role of the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) in Tourism and Sustainable Development in Africa. In Routledge Handbook of Tourism in Africa; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; ISBN 978-1-351-02254-5. [Google Scholar]

- Nunkoo, R.; Gursoy, D.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Effects of Social Media on Residents’ Attitudes to Tourism: Conceptual Framework and Research Propositions. In Theoretical Advancement in Social Impacts Assessment of Tourism Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; ISBN 978-1-003-41319-6. [Google Scholar]

- Chuah, S.H.-W.; El-Manstrly, D.; Tseng, M.-L.; Ramayah, T. Sustaining Customer Engagement Behavior through Corporate Social Responsibility: The Roles of Environmental Concern and Green Trust. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 262, 121348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diallo, M.F.; Diop-Sall, F.; Leroux, E.; Valette-Florence, P. Responsible Tourist Behaviour: The Role of Social Engagement. Rech. Appl. Mark. (Engl. Ed.) 2015, 30, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diallo, M.F.; Diop-Sall, F.; Leroux, E.; Vachon, M.-A. How Do Tourism Sustainability and Nature Affinity Affect Social Engagement Propensity? The Central Roles of Nature Conservation Attitude and Personal Tourist Experience. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 200, 107503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Doorn, J.; Lemon, K.N.; Mittal, V.; Nass, S.; Pick, D.; Pirner, P.; Verhoef, P.C. Customer Engagement Behavior: Theoretical Foundations and Research Directions. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safshekan, S.; Ozturen, A.; Ghaedi, A. Residents’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior: An Insight into Sustainable Destination Development. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Miao, L.; Huang, Z. (Joy) Customer Engagement Behaviors and Hotel Responses. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 33, 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibnou-Laaroussi, S.; Rjoub, H.; Wong, W.-K. Sustainability of Green Tourism among International Tourists and Its Influence on the Achievement of Green Environment: Evidence from North Cyprus. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.-M.; Wu, H.C. How Do Environmental Knowledge, Environmental Sensitivity, and Place Attachment Affect Environmentally Responsible Behavior? An Integrated Approach for Sustainable Island Tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 557–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, M.; Ansari, N.; Raza, A.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H. Fostering Employee’s pro-Environmental Behavior through Green Transformational Leadership, Green Human Resource Management and Environmental Knowledge. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 179, 121643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keles, H.; Yayla, O.; Tarinc, A.; Keles, A. The Effect of Environmental Management Practices and Knowledge in Strengthening Responsible Behavior: The Moderator Role of Environmental Commitment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunitie, M.F.; Saraireh, S.; Al-Srehan, H.S.; Al-Quran, A.Z.; Alneimat, S.; Al-Hawary, S.S.; Alshurideh, M.T. Ecotourism Intention in Jordan: The Role of Ecotourism Attitude, Ecotourism Interest, and Destination Image. Inf. Sci. Lett. Int. J. 2022, 11, 1815–1822. [Google Scholar]

- Luong, T.-B. Eco-Destination Image, Environment Beliefs, Ecotourism Attitudes, and Ecotourism Intention: The Moderating Role of Biospheric Values. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 57, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J.I.M.; Steg, L. Value Orientations and Environmental Beliefs in Five Countries: Validity of an Instrument to Measure Egoistic, Altruistic and Biospheric Value Orientations. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2007, 38, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anicker, N.; Bamberg, S.; Pütz, P.; Bohner, G. Do Biospheric Values Moderate the Impact of Information Appeals on Pro-Environmental Behavioral Intentions? Sustainability 2024, 16, 2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L. Values, Norms, and Intrinsic Motivation to Act Proenvironmentally. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2016, 41, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafieieh, M.; Ozturen, A.; Rezapouraghdam, H.; Karatepe, O.M. Does Critical Thinking Mediate the Relationship between Sustainability Knowledge and Tourism Students’ Ability to Make Sustainable Decisions? Sustainability 2024, 16, 5655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adongo, C.A.; Taale, F.; Adam, I. Tourists’ Values and Empathic Attitude toward Sustainable Development in Tourism. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 150, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeke, A. (Nick) Creating Sustainable Tourism Ventures in Protected Areas: An Actor-Network Theory Analysis. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedict, S.; Hussein, H. An Analysis of Water Awareness Campaign Messaging in the Case of Jordan: Water Conservation for State Security. Water 2019, 11, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeter, C.; Fechner, D.; Dolnicar, S. Progress in Field Experimentation for Environmentally Sustainable Tourism—A Knowledge Map and Research Agenda. Tour. Manag. 2023, 94, 104633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T.; Olk, S.; Thomsen, T.U. A Meta-Analysis of Sustainable Tourist Behavioral Intention and the Moderating Effects of National Culture. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 32, 883–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.-T.B.; Zhu, D.; Liu, C.; Kim, P.B. A Meta-Analysis of Antecedents of pro-Environmental Behavioral Intention of Tourists and Hospitality Consumers. Tour. Manag. 2022, 93, 104566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-S.; Kim, J.; Thapa, B. Influence of Environmental Knowledge on Affect, Nature Affiliation and Pro-Environmental Behaviors among Tourists. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, T.-B. Eco-Destination Image, Place Attachment, and Behavioral Intention: The Moderating Role of Eco-Travel Motivation. J. Ecotourism 2024, 23, 631–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-K.; Olya, H.; Ahmad, M.S.; Kim, K.H.; Oh, M.-J. Sustainable Intelligence, Destination Social Responsibility, and pro-Environmental Behaviour of Visitors: Evidence from an Eco-Tourism Site. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; and Gupta, A. Pro-Environmental Behaviour among Tourists Visiting National Parks: Application of Value-Belief-Norm Theory in an Emerging Economy Context. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, C.; Vinhas da Silva, R.; Antova, S. Image, Satisfaction, Destination and Product Post-Visit Behaviours: How Do They Relate in Emerging Destinations? Tour. Manag. 2021, 85, 104293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, H.; Chen, J.; Li, W. Applying Ecotourism Knowledge and Destination Image in Planned Behavior Theory in Ecotourism. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2024, 33, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A.; Nguyen, T.H.H.; Morrison, A.M. Sustainable Tourist Behavior: A Systematic Literature Review and Research Agenda. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 3356–3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Consumer Behavior and Environmental Sustainability in Tourism and Hospitality: A Review of Theories, Concepts, and Latest Research. In Sustainable Consumer Behaviour and the Environment; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-1-003-25627-4. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, H.; Dai, J.; Tan, S.; Zhang, H. From Biospheric Values to Tourists’ Ecological Compensation Behavioural Willingness: A Comprehensive Model Test Based on the Value-Identity-Personal Norm and Normative Activation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 32, 2540–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A Value-Belief-Norm Theory of Support for Social Movements: The Case of Environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Denley, T.J.; Woosnam, K.M.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Boley, B.B.; Hehir, C.; Abrams, J. Individuals’ Intentions to Engage in Last Chance Tourism: Applying the Value-Belief-Norm Model. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1860–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvajal-Trujillo, E.; Pérez-Gálvez, J.C.; Orts-Cardador, J.J. Exploring Tourists’ pro-Environmental Behavior: A Bibliometric Analysis over Two Decades (1999–2023). J. Tour. Futures 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beall, J.M.; Boley, B.B.; Landon, A.C.; Woosnam, K.M. What Drives Ecotourism: Environmental Values or Symbolic Conspicuous Consumption? J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1215–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Lee, K.; Fairhurst, A. The Review of “Green” Research in Hospitality, 2000–2014: Current Trends and Future Research Directions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 226–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateş, H. Merging Theory of Planned Behavior and Value Identity Personal Norm Model to Explain Pro-Environmental Behaviors. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 24, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Lee, S.; Lee, C.-K.; Reisinger, Y. Volunteer Tourists’ Environmentally Friendly Behavior and Support for Sustainable Tourism Development Using Value-Belief-Norm Theory: Moderating Role of Altruism. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2022, 25, 100712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative Influences on Altruism1. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1977; Volume 10, pp. 221–279. [Google Scholar]