1. Introduction

Climate change and environmental degradation are exacerbating extreme weather events and placing significant pressure on enterprises to reduce carbon emissions and pursue sustainable development. Concurrently, persistent social issues, such as wealth inequality, educational disparities, and unequal employment opportunities, highlight the need for businesses to foster social equity and inclusiveness through CSR co-creation activities [

1]. The rapid development of digital technologies, such as the Internet, social media, big data, and artificial intelligence, has provided new platforms and means for the co-creation of CSR, facilitating a transition in its activities, shifting from conventional offline formats to online platforms. This shift has led to the emergence of virtual CSR co-creation initiatives, exemplified by Alipay’s “Ant Forest” and “Ant Manor”, as well as WeChat’s “Donate Steps” and other similar endeavors. These innovative and consumer-friendly activities offer participants a novel and thrilling experience while allowing them to engage in cost-free and accessible public welfare activities, thereby attracting a substantial number of consumers. Virtual CSR co-creation refers to the activities in which companies strategically plan and encourage valuable consumer participation through Internet platforms and social media technologies [

2,

3]. The unique attributes of virtual CSR co-creation lie in its virtuality, interactivity, ecological focus, and emotional orientation. It also differs from other forms of online consumer engagement, such as social media interactions or online reviews, by focusing specifically on CSR activities and fostering a sense of collective responsibility and purpose among participants. The process leverages the collective intelligence and resources of consumers by providing a more accessible, scalable, and engaging way for individuals to contribute to societal welfare. As co-creation becomes increasingly prevalent in virtual CSR initiatives, companies are confronting a multitude of challenges. First, consumers have a limited understanding of virtual co-creation, resulting in a low willingness to participate. Second, consumer trust in companies is relatively low, particularly during the virtual co-creation process, where insufficient information transparency further diminishes consumer engagement. Additionally, companies lack effective interaction mechanisms, which fail to fully stimulate consumer enthusiasm. These challenges not only affect the effectiveness of virtual co-creation but also hinder the realization of CSR. And, while offline CSR initiatives offer face-to-face interactions and tangible rewards, online platforms offer greater accessibility and scalability but often struggle with user engagement and retention. This necessitates a deeper understanding of the factors that motivate consumers to participate in virtual CSR co-creation activities. Emotional factors, such as identification, enthusiasm, and satisfaction, play a crucial role in consumer willingness to participate in such activities. Online environments lack the immediate social cues and physical rewards present in offline settings, making emotional connections and satisfaction with the activity itself even more important. Identification with the CSR values and goals can foster a sense of belonging and purpose, while enthusiasm and satisfaction can mitigate the potential for boredom or disengagement that may arise in virtual settings. Furthermore, interaction factors, including community platform interaction and offline interaction, also influence consumer willingness to participate.

In recent years, as environmental issues have gained significant attention, firms across various industries and countries are expected to implement green initiatives [

4]. By leveraging virtual communities to engage consumers in co-creation activities, enterprises not only foster a positive brand image and enhance their reputation but also draw attention to pressing social issues [

5]. Prior research highlights that multiple stakeholder pressures can serve as catalysts, motivating firms to adopt greener production practices [

6,

7,

8]. The existing research on CSR co-creation predominantly focuses on specific industries and regions, limiting its generalizability. For example, Cai and Zhou (2014) examined green innovation in Chinese enterprises, with limited applicability to other economies [

7]. Additionally, most studies concentrate on manufacturing, neglecting green practices in other sectors like services. A key limitation is the lack of attention to how emotional and interaction factors affect consumer participation in CSR activities, especially given the growing reliance on virtual platforms. Although social presence in online environments is acknowledged [

9], its mediating role between the emotional/interaction factors and consumer willingness to participate in virtual CSR co-creation remains underexplored.

Recognizing the limitations of solely focusing on internal resources, many firms have turned their attention to open innovation [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. For instance, Alipay’s Ant Forest initiative urges individuals to care for the environment, reduce carbon emissions, and preserve natural landscapes. Keep’s public welfare running activities realize the co-creation of social value through the combination of sports and public welfare. For example, the “Dream Stadium” project provides children in remote areas with sports facilities by exchanging consumers’ running miles for charity materials. This model not only enhances consumers’ participation in public welfare but also conveys positive social values through sports. In today’s business landscape, sustainability is an area of growing interest for most organizations [

15,

16]. Several studies indicate that environmental performance correlates with higher financial performance [

17,

18]. These activities provide participants with a novel and thrilling experience, allowing them to engage in cost-free and accessible public welfare efforts, thus attracting substantial consumer participation.

Consumer participation in virtual CSR co-creation activities inherently represents a collaborative process of social value creation. According to the theory of value co-creation, “consumer participation” denotes a cooperative effort between consumers and enterprises, highlighting consumers’ pivotal role as the primary agents driving this process. Consumer participation can be categorized into narrow and broad dimensions: narrow participation refers exclusively to tangible actions, while broad participation encompasses emotional involvement as well [

19]. Gamified reward mechanisms (e.g., behavior-based vs. result-based incentives) align with risk-sharing and transparency principles. Building on Jun et al. (2020), we argue that experiential interaction paths (e.g., social storytelling, real-time feedback) fulfill consumers’ needs for autonomy and competence, driving sustained co-creation [

20]. In addition, drawing from Infovision iCommunity’s case studies, virtual CSR platforms act as “digital commons”, where global and local values intersect (e.g., self-transcendence vs. self-enhancement cultural norms). Cognitive appraisal theory emphasizes that an individual’s cognitive appraisal of a situation influences his or her affective responses and behavioral decisions. In virtual CSR co-creation, emotional factors (e.g., vitality, sense of belonging) may influence consumers’ participation behavior by affecting their cognitive appraisal. Consumers’ willingness to participate fluctuates with their emotional responses throughout the participation process. In real-world contexts, consumer satisfaction with the content and outcomes significantly influences their willingness to participate. Additionally, their identification with the activity’s content and value, coupled with their enthusiasm for dedicating time, also shape their participation. The heightened environmental consciousness among consumers further motivates enterprises to reduce their negative environmental impacts [

21,

22]. Furthermore, the intricate themes that involve enterprises, consumers, and other stakeholders impart a social aspect to these activities. Stakeholders are recognized as individuals or groups that can influence the decisions, practices, or objectives of the organization [

23,

24]. It is particularly crucial to systematically communicate CSR outcomes to external stakeholders through corporate reports, as they lack access to private information from firms [

24]. Depending on consumers’ interactions with others during these activities, they can be divided into two categories—community platform interaction and offline interaction—both of which impact the consumer willingness to participate and the subsequent behaviors.

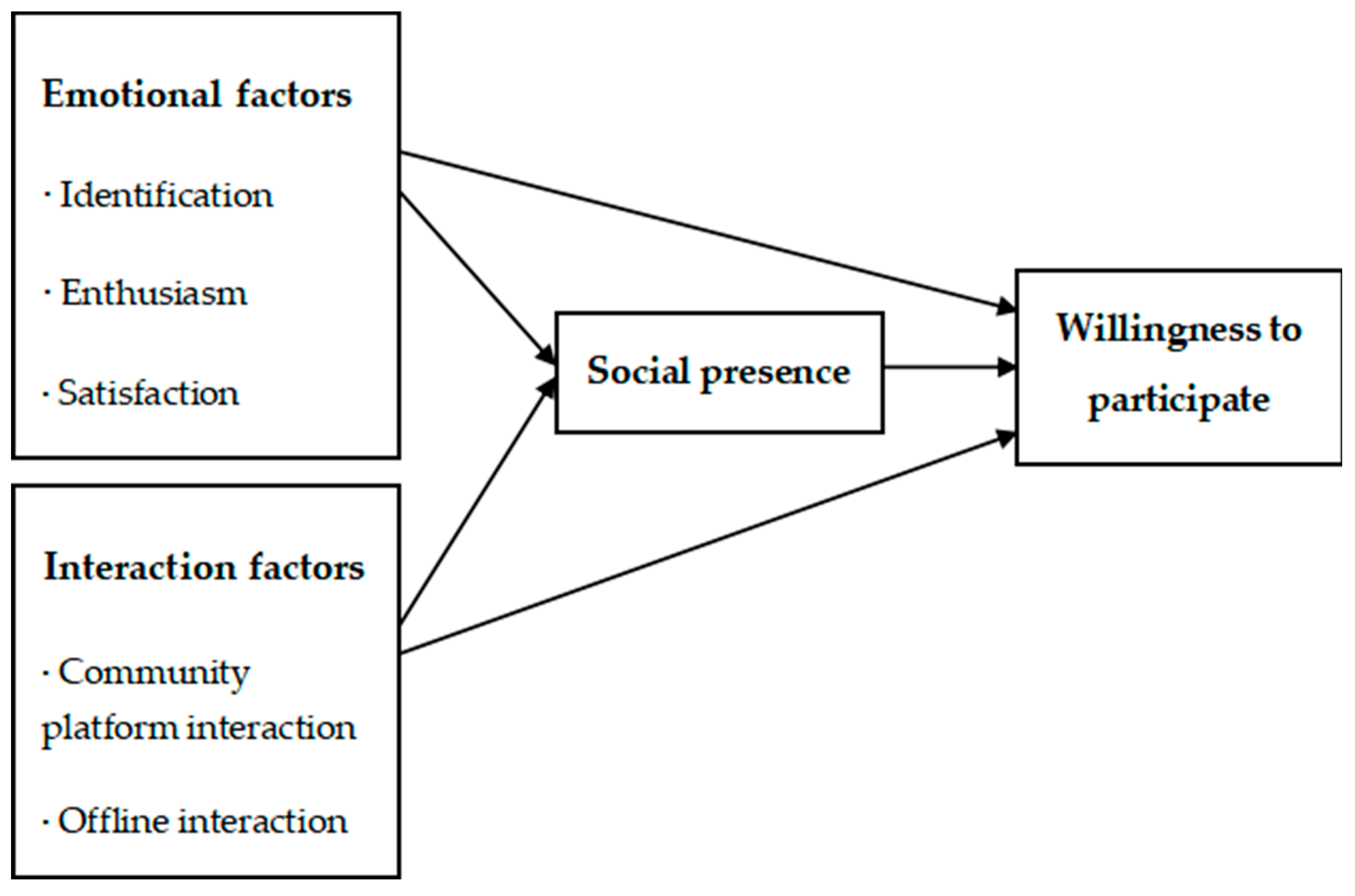

To address challenges, our research focuses on understanding the factors that influence consumer willingness to participate in virtual CSR co-creation activities. Specifically, we propose that emotional factors (identification, enthusiasm, and satisfaction) and interaction factors (community platform interaction and offline interaction) play a crucial role in determining consumer willingness to participate. This connection is grounded in the Stimulus–Organism–Response (S-O-R) model, which posits that external stimuli affect consumer behavior by influencing their psychology. In the context of virtual CSR co-creation activities, emotional factors, such as identification, enthusiasm, and satisfaction, are critical as they shape consumers’ emotional responses and attitudes towards the activities. Identification, enthusiasm, and satisfaction reflect affective evaluations rooted in Lazarus’s (1991) transactional theory of stress and coping. Identification fosters a sense of belonging [

25], enthusiasm activates intrinsic motivation [

26], and satisfaction aligns with goal attainment theory [

27]. When consumers feel a sense of unity and belonging (identification), enjoy participating (enthusiasm), and are satisfied with the outcomes (satisfaction), they are more likely to persist in their engagement. Similarly, interaction factors, both within the virtual community platform and offline, foster a sense of mutuality and camaraderie, enhancing consumer willingness to participate. According to the S-O-R model, external stimuli exert an impact on consumer behavior by affecting consumer psychology. We conceptualize enterprise-led virtual CSR co-creation activities as the primary stimulus. Such stimuli function as environmental cues that initiate cognitive and affective processing, akin to algorithmic nudges in social media [

28]. Notably, enterprise-led virtual CSR co-creation activities primarily occur online, devoid of face-to-face interactions among consumers and between consumers and enterprises [

29]. Social presence, in this context, pertains to the capacity of consumers to convey a sense of personal existence and social warmth through virtual communities and online messaging platforms. As posited by Swan and Shih (2005), social presence embodies the ability of consumers to present their “true selves” on online social media platforms during participation, thereby influencing reciprocal behaviors [

9]. Consequently, this study posits that social presence mediates the influence of emotional and interactive factors on consumer willingness to participate. This mediation is grounded in the dual-process model [

30], where social presence amplifies affective salience and reduces transactional uncertainty.

5. Construct Reliability and Validity

As shown in

Table 4, the α coefficients of all the variables are greater than 0.8, signaling a very high level of scale reliability. The CITC value of each item is above 0.3, denoting strong correlations among the items and good reliability. Furthermore, the “α coefficient when an item is deleted” for each item is lower compared to the overall α coefficient of its corresponding variable, suggesting that each item contributes positively to the variable’s α coefficient, thereby affirming the rationality of their inclusion. Collectively, the questionnaire employed in this study demonstrates excellent reliability, with the utilized variables and their respective measurement items exhibiting high internal consistency. This satisfies the reliability standards for empirical research and supports further in-depth analysis.

As shown in

Table 5, the KMO value is 0.934, exceeding the threshold of 0.7. The results of Bartlett’s test of sphericity are significant at the 0.001 level, indicating a high degree of correlation among the measurement items and their suitability for further factor analysis.

This study employs confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess the structural validity of the conceptual model. This study comprises 26 analysis items, with an effective sample size of 232, which is nine times the number of items, indicating a sufficient sample size for conducting factor analysis.

As illustrated in

Table 6, the rate of the cumulative variance explained is 77.742%, indicating that the factors of the seven dimensions selected by the model can explain the scale information well. The factor loading coefficients for all items exceed the threshold of 0.4, and within each dimension, the items demonstrate a high correlation with the corresponding factors. This indicates that the measurement items designed for the seven variables, namely identification, enthusiasm, satisfaction, community platform interaction, offline interaction, social presence, and willingness to participate, can be effectively categorized into seven corresponding factors. Overall, the scale exhibits a strong structural validity.

As shown in

Table 7, the factor loading coefficients of most variable items exceed 0.7, with a few, such as the factor loading coefficient of 0.688 for SP4, closely approaching the threshold. The AVE values for the variables are 0.6547, 0.6767, 0.7332, 0.7147, 0.6804, 0.6081, and 0.6397, all surpassing the standard of 0.5. Similarly, the CR values are 0.8829, 0.8932, 0.8918, 0.9085, 0.8646, 0.8606, and 0.8765, respectively, each exceeding the benchmark of 0.7. Overall, the scale demonstrates good convergent validity.

As shown in

Table 8, the AVE square root values for most variables surpass the highest absolute correlation coefficients between these variables and others. Only the AVE square root value for social presence falls slightly below the absolute correlation coefficients with other variables, yet it remains very close. In summary, these results demonstrate that the scale possesses good discriminant validity.

6. Data Analysis and Results

In this study, the theoretical model undergoes further validation through the application of structural equation modeling (SEM), with the analysis conducted using AMOS 28.0. The model fit indices, such as the absolute fit index (e.g., GFI, RMSEA), value-added fit index (e.g., CFI, IFI, NNFI), and parsimonious fit index (e.g., CMIN/DF, PGFI, PNFI), are selected for validation and evaluation. The model can be considered as well fitted if the individual indices satisfy the standard requirements [

57]. As illustrated in

Table 9, all model fit indices satisfy the criteria, indicating that the model exhibits a good fit.

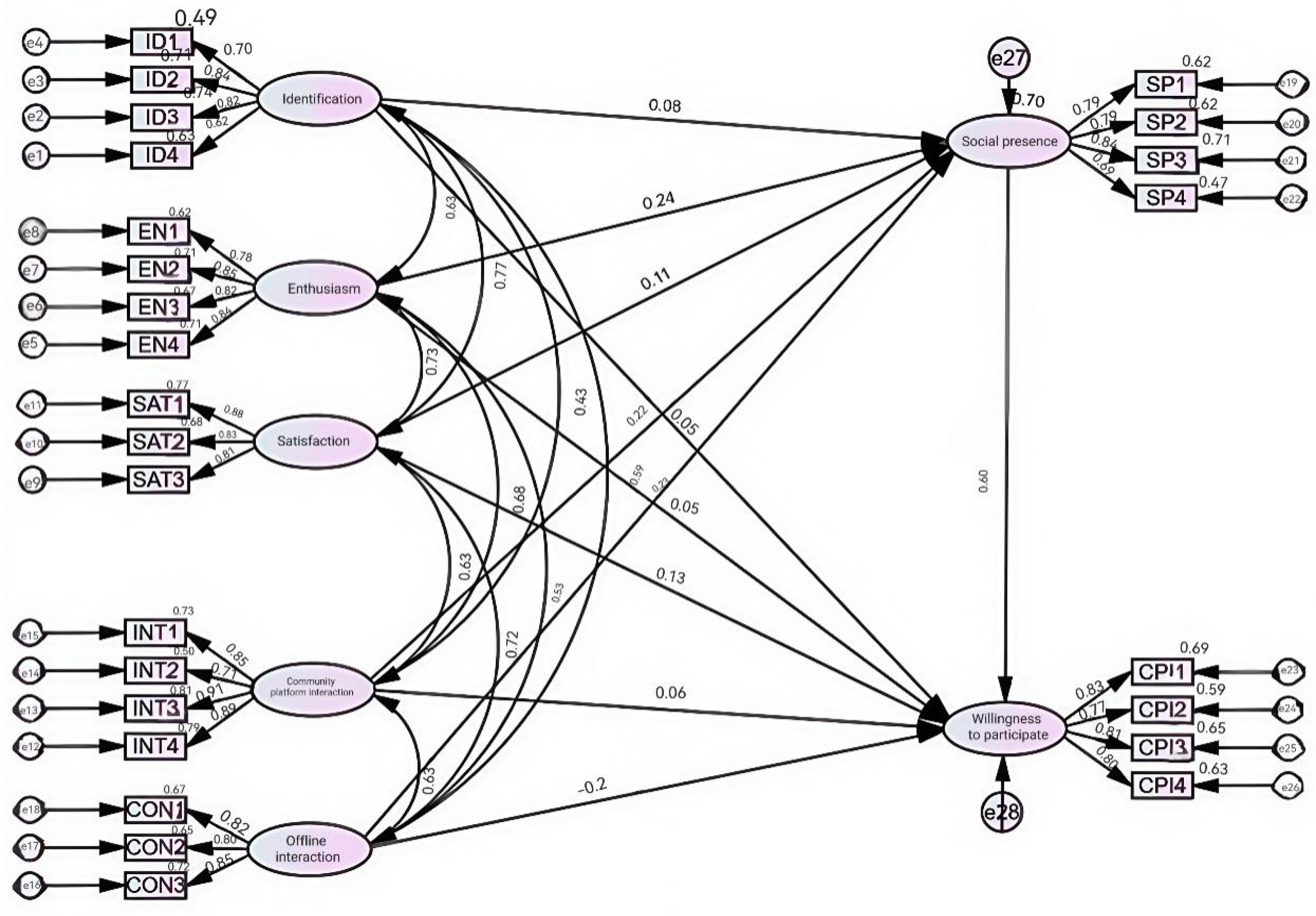

As shown in

Figure 2 and

Table 10, the hypotheses proposed in this study all posit positive effects, thus a hypothesis is considered valid if the standardized path coefficient β falls within the range (0, 1) and the significance level

p is less than 0.05. According to the results in

Table 10, it can be seen for H1a that β equals 0.055 and is significant at the

p < 0.05 level, confirming the validity of H1a. For H1b and H1c, the β values are 0.046 and 0.133, respectively, both with

p-values below 0.05, validating these hypotheses as well. For H2a, while β is 0.057, the

p-value of 0.552 exceeds 0.05, rendering H2a invalid. Similarly, H2b shows a β of −0.019 and a

p-value of 0.848, also exceeding 0.05, thus invalidating H2b. Lastly, H3 demonstrates a β of 0.602 with a

p-value less than 0.05, confirming its validity.

This study hypothesizes that social presence plays a mediating role, and the hypothesis is valid when the significance level of

p < 0.05. According to

Table 11, the

p-values for H4a, H4b, and H4c are all greater than 0.05, thus the hypotheses are not supported; whereas, the

p-values for H4d and H4e are 0.003 and 0.01, respectively, both falling below 0.05, confirming the validity of the hypotheses.

8. Conclusions

This study examined the effects of emotional and interaction factors on the consumer willingness to participate in virtual CSR co-creation activities, with a particular focus on the mediating role of social presence. Our results indicate that emotional factors, including identification, enthusiasm, and satisfaction, positively influence consumer willingness to participate in virtual CSR co-creation activities. Among these factors, enthusiasm emerged as the most significant predictor, underscoring the importance of fostering enjoyable and engaging experiences for consumers. Secondly, our study reveals that social presence plays a crucial role in mediating the relationship between interaction factors (both community platform interaction and offline interaction) and consumer willingness to participate. This finding highlights the significance of creating a sense of social connection and belonging within virtual CSR communities. Thus, this work extends the Stimulus–Organism–Response (S-O-R) model by incorporating social presence as a mediator in the context of virtual CSR co-creation. Furthermore, it provides empirical evidence on the relative importance of emotional and interaction factors in shaping consumer willingness to participate, with implications for the design and promotion of virtual CSR initiatives.

This study innovatively applies the S-O-R framework to virtual CSR co-creation, identifying algorithmically mediated stimuli as novel environmental cues and revealing social presence’s unique mediating role. It also parses emotional factors into identity-driven and experience-driven pathways, offering fresh insights for affective computing in non-transactional contexts.