Abstract

The Lower Silesian Voivodeship is one of 16 Polish voivodeships—it covers the Lower Silesia region. The area was chosen for this study due to its location at the crossroads of three countries (Poland, the Czech Republic, and Germany), centuries-old traditions in terms of the tourist function, wealth of nature, and the specificity of its demographic potential (almost total replacement of the regional community after World War II). The article identifies the main components of the settlement network and refers to the 11th Sustainable Development Goal. The purpose of this article is to analyze demographic changes and the evolution of the tourist function in Lower Silesia, with particular focus on their correlations and spatial diversification. The conducted analyses were based on the statistical data provided by the Local Data Bank of the Statistics Poland (LDB SP). Synthetic measures of development were used to analyze the tourist function. The research period varies depending on the particular stage and results from the availability of statistical data. The core of the research covers the years 1946–2023. It was established that Lower Silesia is characterized by a developed tourist function but, simultaneously, has been experiencing an increasingly pronounced demographic crisis. The research findings point to divergent choices made by the users–residents and users–tourists. The leaders in terms of the tourist function include, i.e., the Karkonosze County and Jelenia Góra city with county rights and, at the same time, the rapidly depopulating areas. The leading cities of Lower Silesia are not developing in an even manner; in this respect, the region is moving away from the 11th Sustainable Development Goal.

1. Introduction

It is natural that humans need good quality space to exist [1]. Given the increasing degree of urbanization in this context, urban space is of particular importance [2,3]. This has already been recognized at the level of Sustainable Development Goals—specifically the 11th Goal [4,5,6]. Theories explaining the development of regions repeatedly highlight the need to strive for sustainable development of the entire area and avoid creating excluded spaces [7,8,9]. It is therefore important to track the development in different parts of the regions—both the leading cities and the entire area of the region.

The cross-border region addressed in this study, i.e., Lower Silesia, constitutes a special case. Firstly, the area is located at the crossroads of three countries, the European Union Member States, i.e., Poland, the Czech Republic, and Germany. Consequently, the freedom of movement and settlement of people (in other words: the users of space) has been ensured here since 2004 by the EU regulations. Poland’s accession into the European Union structures changed the previous border protection policy towards a policy featuring highly advanced economic integration by creating customs unions and areas of free movement for people through reducing or eliminating border controls [10,11,12].

Secondly, the region has a centuries-old tradition of tourism. Significant changes in economic relations and the location of services, due to the increased freedom of border crossing, have been observed in the Polish–Czech border area [13,14,15]. In addition, the region’s transportation accessibility has improved significantly in recent years. The processes of European integration accompanied by the development of cross-border road connections resulted in the border no longer posing a communication barrier. The transformations of road networks in border areas, which in the Polish-Czech region have a particularly positive influence on the development of tourism [16], have also exerted a great impact on these changes.

Thirdly, the changes in national borders which took place after World War II led to an almost total replacement of the regional community [17,18].

Lower Silesia as a historic region may, as a certain simplification, be identified with the Lower Silesian Voivodeship, which occupies approx. 19.9 thousand km2, i.e., 6.4% of Poland’s territory. The voivodeship is connected with a few large geographic regions: the Silesian Lowland, the Silesian–Sorbian Lowland, the Sudeten Foothills, and the Sudetes [19].

Tourism has been developing in the Lower Silesia region for centuries. Before 1945, when the area was within the borders of Germany, the natural, scenic, and cultural values of the region were appreciated, contributing to the significant development of tourism. After the region entered the structures of Poland, an initial slump in the development of this economy sector was recorded: the national economy required time to stabilize after World War II. The political transformation of Poland in the late 1990s was also a difficult moment for Lower Silesian tourism. Regardless of incidental difficulties, tourism in the area covered by the study has developed and is developing in an impressive way. This is due to the significant concentration of historic urban complexes, architectural and building structures as well as high natural attractiveness [20]. It is worth noting that the cultural heritage in the Lower Silesian Voivodeship is characterized by the highest number of objects listed in the register of historic monuments in the country.

It has been emphasized in the source literature that Lower Silesia, especially the Sudetes Mountain range, belong to the most attractive areas in Poland, boasting a long tourist tradition. This appeal comes from, among others, landscape values (two national parks; twelve landscape parks, one of which is of a cross-border character [21]; natural wonders (waterfalls, river breaks, picturesque rock formations); numerous spa towns [22], good skiing areas; and others). Currently, the Lower Silesian Voivodeship is the third largest region in Poland in terms of the number of tourists. The long-term popularity of Lower Silesia attracts attention to the negative aspects of tourism. The adoption of Social Exchange Theory for the purposes of the tourist function indicates that local communities evaluate tourism on the basis of costs and benefits—the prevalence of costs (also understood as inconveniences) can lead to anti-tourist attitudes [23,24]. The Index of Irritation directly describes the stages of evolution regarding attitudes toward tourists—from euphoria to hostility [25]. In this context, it is worth analyzing the attitudes of both tourists and locals toward the same space.

Beyond any doubt, tourism is a success story of the region under study. Unfortunately, this success is accompanied by the simultaneous disturbing demographic phenomena. Depopulation processes have been a part of the Lower Silesian demographic transition for many years [26]. The greatest population decline was observed in the municipalities located in the southern part of the voivodship (including Wałbrzych, Kamienna Góra, Mieroszów, Platerowka, Jelenia Góra, Przeworno, Świeradów-Zdrój, Duszniki-Zdrój, Nowa Ruda, and Głuszyca). The interesting problem, which also requires analysis, is the fact that depopulation does not spare the very attractive areas in terms of tourism [27,28].

The purpose of this article is to analyze demographic changes and the evolution of the tourist function in Lower Silesia, with particular focus on their correlations and spatial diversification. The answers to the following research questions were investigated:

- Are the populations of the leading Lower Silesian cities developing in an even manner?

- What kind of quantitative changes have been identified in the populations of Lower Silesian counties?

- Does the development of the county’s tourist function (indicative of the user–tourist interest) coincide with the user–resident interest in the county?

The research was based on the data provided by the Local Data Bank of the Statistics Poland (LDB SP). A long-term observation was attempted, and the research period derives from the availability of statistical data.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characteristics of the Research Process

The first stage of the research conducted consisted of a library query. It was decided to adopt the perspective of a space user—a permanent resident and a tourist. The research period for the population of the leading cities covered the years 1946–2023. In the case of Wroclaw only, the period was extended to 1939–2023. For the remaining counties, the time perspective covering the years 1995–2023 was adopted. These periods derive from the availability of data in the LDB SP. The LDB SP is an official, and the largest, database in Poland providing data on the economy and households, innovation, public finance, society, demography, and the environment [29]. The SP performs tasks in the field of public statistics [30]; therefore, a reliable source of statistical data was selected. Each time the data were obtained, the definitions used in public statistics were checked [31], and it was ensured that the data were comparable for the entire period under study. Regarding the data needed to calculate the tourist function indicators, the compatibility of statistical definitions with the indicator construction was also checked.

It should be clarified that the LDB SP provides data for counties since 1995, despite the fact that counties were established as a result of the administrative reform which took place in 1999 (the data were recalculated accordingly). For the research addressing tourism, the analyzed period was shortened to 2010–2023 (as in previous studies, the need to shorten the research period was due to data availability in the resources provided by LDB SP).

The analysis of the development level regarding the tourist function, performed for the period 2010–2023, was carried out based on the synthetic development measure (SDM) calculated using the standardized sums method combined with the unitization method. As the synthetic measure of development is a popular and widely recognized method of linear ordering [32,33,34] it was decided to use it.

The adopted research procedure includes the following:

- Defining variablesThree indicators were defined:

- Baretje–Defert’s tourist function index [35],

- Charvat’s index of tourism intensity [36],

- Tourist accommodation density index [37],

All of the above indicators were considered stimulants without a veto threshold and were not given weights (they were considered equivalent).

The choice of indicators results from their widespread recognition in the source literature [38,39,40,41] and a long tradition of their application in scientific research. It is worth noting that they have already been mentioned by Warszyńska and Jackowski in their monograph [37], which directly cites the original publications of Baretje and Defert “Aspects economiques du tourisme” as well as Chavat and Cerny “Untraditionelle Elemente bei der Erfassung der Fremde-nverkhersintensitat”. In addition, such a choice of indicators ensures the comparability of the results to the previously performed studies addressing the areas territorially linked to the most valuable natural areas of Poland (which will be the subject matter of other future studies) [42]. The selection of the above-mentioned indicators was also influenced by the availability of statistical data, which did not depend on the Authors.

The group of the aforementioned indicators complement each other and reflect three aspects of tourism performance—the infrastructural, social, and spatial ones. The Baretje–Defert tourist function index shows the relationship between the number of beds in accommodation establishments and the number of residents, reflecting the extent to which an area is equipped to receive tourists. Charvat’s index of tourism intensity allows for assessing tourism pressure on a local community, showing the number of overnight stays per 100 residents. It is useful for assessing the impact of tourism on the daily functioning of a region. The accommodation density index allows for determining the concentration of accommodation infrastructure in an area.

- 2.

- Conducting the zero unitarization procedure of (Z) variables for the entire period simultaneously (2010–2023).

Unitarization was performed using the following formula:

explanatory notes:

x—variable value;

j—variable j;

i—object (county);

t—time (year).

Such a unitization formula allows for obtaining values in the range [0, 1]. This method is simple, effective, and as useful as the latest methods applied in the unitization of features [43,44,45].

- 3.

- SDM construction according to the standardized sum method with a common development pattern for 2010–2023.

- 4.

- Assigning ranks to counties and comparing county positions in the ranking.

As indicated earlier, the data provided by the LDB SP were used to calculate the aforementioned indicators. The findings are presented in figures generated using QGIS software 3.34 PRIZREN.

2.2. Characteristics of Lower Silesia—Introductory Information and Description of the Main Urban Centers

Lower Silesia is not only a voivodeship, i.e., a part of the country separated as a result of an artificial administrative division, but also a historic and geographic region. Both the western and southern borders of the Lower Silesian Voivodeship serve, at the same time, as state borders with the Federal Republic of Germany (border length 80 km) and the Czech Republic (border length 434 km) [46]. The post-war history of administrative divisions regarding the described area is interesting: The area was detached from Germany and annexed to the Polish People’s Republic. After World War II, Lower Silesia functioned as the Wroclaw Voivodeship; this status persisted in the years 1945–1974.

Next, following the project implementation to increase the number of voivodships in Poland in 1975, four voivodships were established in the studied area: Jelenia Góra, Legnica, Wałbrzych, and Wroclaw Voivodships (Figure 1). In 1999, the idea of a smaller number of voivodships was revisited, and thus the concept of a single voivodship covering the region of Lower Silesia was established. The name of the voivodeship was changed: in 1945–1974, it was Wroclaw Voivodeship, but from 1999 to now, it has been the Lower Silesian Voivodeship.

Figure 1.

Administrative division of Poland in 1945–1974 and 1975–1998 (explanatory figure). Source: own compilation based on [47].

Almost 60% of the region’s area is covered by agricultural land. Next on the list (approx. 31% of the area) are forest land, trees, and bushlands. Urbanized and built-up areas account for approx. 7%. The smallest share of Lower Silesia’s area is taken up by water areas and wasteland, occupying a total of less than 2% of the voivodship’s area. The difference between the highest (Zieleniec) and the lowest (Skidniów) location is 831 m. When the points are compared—the highest point is Śnieżka, while the lowest one is also the lowest location—the value goes up to 1533 m. There are 15 mountain peaks higher than 1000 m above sea level in the Lower Silesian Voivodeship, which does increase the tourist attractiveness of the area [48].

The capital of the region is the city of Wroclaw, which is not only an economic but also a cultural center. Already in the early 2000s, it was noticeable that the city was changing towards a multifunctional metropolis, increasingly strengthening ties with other European metropolises, as evidenced, e.g., by the growing foreign passenger traffic at Wroclaw Airport [49]. The city authorities, using neoliberal branding strategies and contributing to the organization of major events, such as Euro 2012, positioned the city in the global economy, resulting in an influx of tourists, foreign capital, and also highly skilled migrants [50]. For many years, Wroclaw has been perceived by its residents as a multicultural city; it happened despite the objectively low share of migrants in the general population [51].

Wroclaw’s rank has been gradually rising—in 2016, the city was the European Capital of Culture, which significantly contributed to the promotion of Lower Silesian cultural heritage [52]. Wroclaw is an important destination in the city break category—it offers a convenient nightlife infrastructure [53]. It is also becoming a smart city, friendly to both tourists and residents [54].

Other cities presenting supra-regional significance are Wałbrzych, Legnica, and Jelenia Góra. An analysis of the territorial structure based on the administrative division shows that Lower Silesia includes 26 counties, 4 cities with county rights, and 169 municipalities. The resident population of Lower Silesia amounts to 2.9 million, i.e., an average of 144 inhabitants per km2. The discussed region has reached a high level of demographic urbanization—almost 68% of the region’s population resides in cities [55].

A long-term regional analysis of the development of the Lower Silesia demographic structure identifies three phases of development in the studied region: the phase of settlement and development, the phase of development stabilization under the conditions of the country’s industrialization, and the phase of transformation to the market economy [56]. Lower Silesia experienced two processes of transformation: The first took place shortly after the end of World War II and was caused by the post-war change in borders, resulting in the region’s incorporation into the structures of Poland. The second transformation was initiated along with the transformation of the entire Polish economy: In 1989, Lower Silesia, following the rest of the country, began to move away from the centrally planned economy model and implemented the principles of market economy. The accession of Poland to the European Union in 2004 was an impulse reinforcing the phenomena initiated in 1989.

3. Results

3.1. Population of Lower Silesia—Long-Term Studies

One of the effects of the post-war border changes that took place in Europe was the replacement of communities in Lower Silesia—almost the entire population of German nationality left the described region. Already, by the end of 1946, the Polish population was estimated at 1,166,000—the newcomers arrived predominantly from central Poland and as repatriates from the USSR [18]. Not only Poles were found among the new residents of the region—in 1947, as a result of the so-called “Operation Vistula”, the representatives of both Ukrainian and Lemko populations were forced to move to the studied area [57]. The settlement activity continued not only during the first post-war years—in the period 1950–1960, 27,655 families were moved to the agricultural areas of Lower Silesia [58]. In the post-war years, Lower Silesia experienced a significant increase in birth rate—over 30% [59]. As time passed, the birth rate values gradually decreased, and since 1998, it has reached a negative value. The Lower Silesian population is subject to an increasingly accelerated aging process.

Characteristic for the settlement network of Lower Silesia—requiring a separate analysis—are the cities of supra-regional importance, i.e., Wroclaw, Jelenia Góra, Wałbrzych, and Legnica.

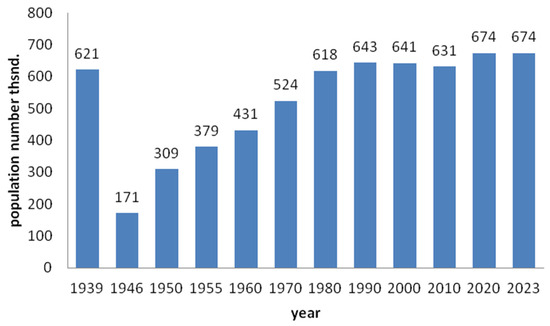

The conducted demographic analysis of Wroclaw shows that in the post-war period, a very high population growth rate was recorded—despite that, however, the capital of Lower Silesia did not rebuild its pre-war demographic potential until the 1980s (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Population of Wroclaw in the period 1939–2023. Source: own compilation based on the statistics provided by the LDB SP.

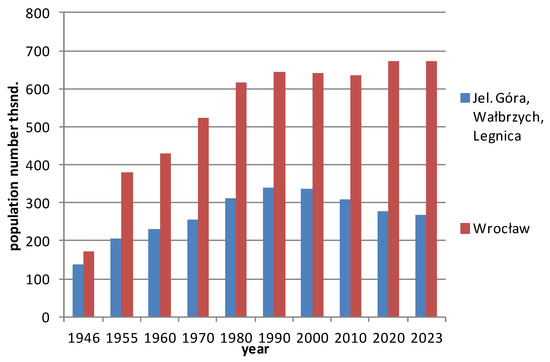

An analysis covering the population of the other three aforementioned cities shows that they were developing at different rates. In the postwar years, the largest population growth was recorded in Legnica—in the years 1946–1955, the population of this center doubled. During the same period, a similar growth in population was observed in Wałbrzych (50.73%). The community of Jelenia Góra increased the least—by only 15.24%. Jelenia Góra experienced a boom in the period 1970–1980 when the city population increased by more than 55%. At the same time, the population of Legnica went up by about 20%, while the respective figure for Wałbrzych was less than 7%. It is worth highlighting, however, that the rapid growth in Jelenia Góra’s population was largely due to administrative changes—in 1973, the villages of Czarne and Goduszyn were annexed to the city; in 1976, the village of Maciejowa, the city of Cieplice Śląskie Zdrój, and also the town of Sobieszów [Miasta na prawach powiatu w województwie dolnośląskim w 1998, 1999] were annexed to the city [57]. Until 1989, Wałbrzych was considered the most steadily developing Lower Silesian city of supra-regional importance. After the post-war population surge, Wałbrzych’s population was increasing steadily by approx. 6% per decade—the city has never again experienced any rapid changes in this regard. Beginning in 1989, Wałbrzych’s situation started to deteriorate—high structural unemployment recorded in the city significantly worsened the quality of life of its residents. Currently, Wałbrzych’s population—similarly to the other analyzed cities—has been declining.

In the period 1946–2023, the total population of Jelenia Góra, Legnica, and Wałbrzych never exceeded that of Wroclaw. This fact confirms the huge difference in demographic potential between the capital and the other largest urban centers of the region. Unfortunately, a progressive stratification of Wroclaw potential and the other analyzed centers is well visible (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Population of Wroclaw compared to the population of Jelenia Góra, Legnica, and Wałbrzych in the period 1946–2023. Source: own compilation based on the statistics provided by the LDB SP.

As already mentioned, the Lower Silesia region is characterized by a high percentage of the population residing in cities—this status has persisted continuously since the post-war period. Immediately after World War II, the urban population rate in, at that time, the Wroclaw Voivodship was 40.4%, and by the mid-1960s, the rate in question had already reached 62.6% [18]. The upward trend in urban population continued in Lower Silesia in subsequent years as well. In the voivodships established in 1975, the Wroclaw and Wałbrzych Voivodeships led the way in this respect. The other two voivodships (Jelenia Góra and Legnica) presented an urban population rate approx. 10% lower than the above-mentioned ones but still higher than the national average. Currently, urban population accounts for about 70% of Lower Silesia population. This result ranks the region as second in the country after the Silesian Voivodeship.

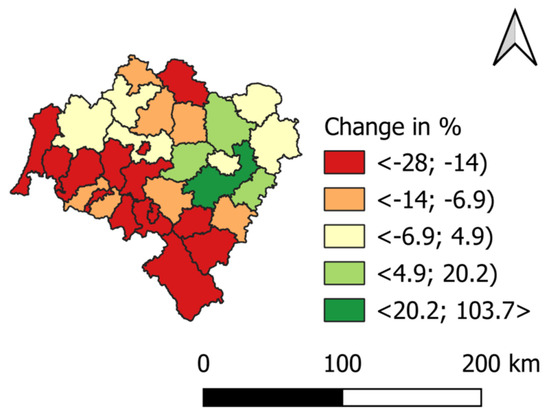

An analysis of the population of Lower Silesian counties indicates that during the period 1995–2023, a decrease in population was recorded in the majority of counties (22 out of 30). The percentage change in population between the beginning and end of the indicated period is shown in Figure 4. The classes were determined according to Jenks’ rule. The predominance of the counties surrounding Wroclaw over the other counties in the studied region is clear; green color indicates population growth. Unfortunately, all cross-border counties are significantly affected by depopulation (shades of red).

Figure 4.

Changes in the population of Lower Silesian counties—comparison of the data for 1995 and 2023. Source: own compilation in QGIS program.

An analysis of the figures shows that a decrease of more than 10% in population was recorded in as many as 16 of the analyzed counties. More than a 10% increase occurred in two counties (Trzebnica 17%, Środa 20%). Only the Wroclaw County recorded a population growth of more than 100% (104%). The largest percentage population decline was reported in Wałbrzych city with county rights (−28%).

Taking the number of residents as a criterion, the ranking was developed, and the counties were given ranks (the highest rank means the most favorable situation). A comparison of rankings from the first (1995) and last (2023) years covered by the analysis shows that only five counties did not change their ranking. These were the following counties (the ranking is given in parentheses): Lubin County (6), Świdnica County (3), Wołów County (24), Złotoryja County (27), and Wroclaw city with county rights (1). A decrease in 15 counties was recorded, i.e., Jelenia Góra County city with county rights, Dzierżoniów County, Kamienna Góra County, Wałbrzych County, Zgorzelec County, Wałbrzych city with county rights, Jawor County, Kłodzko County, Lubań County, Lwówek Śląski County, Ząbkowice County, Legnica city with county rights, Głogów County, Góra County, and Karkonosze County. In the case of 10 counties, a higher ranking was recorded: Milicz County, Legnica County, Oława County, Strzelin County, Bolesławiec County, Oleśnica County, Polkowice County, Trzebnica County, Środa County, and Wroclaw County.

Concluding the discussion of the demographic and social situation in Lower Silesia, it should be emphasized that not only is the demographic crisis becoming more pronounced now, but also very disturbing forecasts have been made. Statistics Poland, in its forecast for 2040, has assumed a further increase in the population of the Wroclaw County (by 39,500 people or 26.1%), Trzebnica County (by 4600 people or 5.4%), Środa County (by 1200 people or 2.1%), and Oława County (by 0.3 thousand people or 0.4%). The least favorable situation is expected in Jelenia Góra (a decline by 17,400 people or 22.1%), Wałbrzych (a decline by 24,400 people or 19.9%), and Kamienna Góra County (a decline by 8200 people or 19.1%) [60].

3.2. Tourism in Lower Silesia

The centuries-old tourist traditions developed in the region allow specifying two main tourist destinations—the Sudeten (for tourism based on sightseeing, recreation and spa values) and the city of Wroclaw (for tourism based on cultural values) [61].

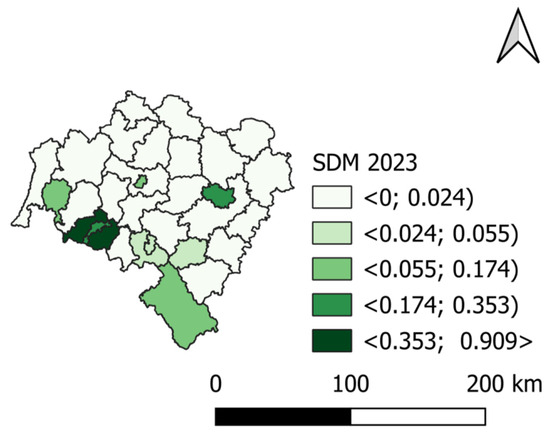

The above is confirmed by an analysis of the SDM value characterizing the level of the tourist function realization in Lower Silesian counties. The findings justify the conclusion that the Karkonosze County (leader) and Wroclaw city with county rights (vice-leader) dominated throughout the period covered by the study—the most favorable situation is presented in Figure 5 by the most saturated green. They were followed by Jelenia Góra County and Legnica city with county rights. A comparison of SDM values for 2010 and 2023 shows that the degree of the tourist function realization declined only in eight analyzed counties (Milicz County, Wołów County, Środa County, Strzelin County, Polkowice County, Trzebnica County, Góra County, and Zgorzelec County)—see Figure 5.

Figure 5.

SDM—level of realization of tourism function in 2023. Source: own compilation in QGIS program.

In the last year of the study (2023), the highest SDM values in the land counties were recorded in the Karkonosze County (0.9094), the Lubań County (0.1738), and the Kłodzko County (0.1683). This suggests the popularity of the Karkonosze region and the Kłodzko Basin. Wroclaw dominates among the townships (0.3529). The other townships presented the following SDM values: Jelenia Góra County (0.2003); Legnica County (0.1644); Wałbrzych County (0.0540). Among the counties characterized by an increase in tourism (SDM 2023 > SDM 2010), the Karkonosze County stands out (0.4153 → 0.9094)—it is not only the leading county in the tourist function realization but also the one recording a spectacular increase in the SDM values. The vice-leader—Wroclaw city with county rights—also recorded a significant increase in the SDM value (0.213 → 0.3549).

It is worth highlighting that high SDM values are recorded by almost all counties territorially linked to national parks and/or resorts. Two national parks have been established in Lower Silesia: the Karkonosze National Park (territorially linked to the Karkonosze County and the city of Jelenia Góra) and the Stołowe Mountains National Park (territorially linked to the Kłodzko County). The ever-increasing popularity of protected areas allows for assuming that the tourist function will continue to develop in the aforementioned counties [42]. Lower Silesian resorts are located in the Kłodzko County (Polanica Zdrój, Kudowa Zdrój, Duszniki Zdrój, Lądek Zdrój, Długopole Zdrój); Lubań County (Czerniawa Zdrój, Świeradów Zdrój); Jelenia Góra city with county rights (Cieplice Zdrój); Wałbrzych County (Jedlina Zdrój, Szczawno Zdrój); and Dzierżoniów County (Przerzeczyn-Zdrój).

4. Discussion

Long-term studies addressing the demographic situation in Lower Silesia do not inspire optimism. What used to be an asset of Lower Silesia started changing into its increasingly visible problem. The post-war replacement of communities was combined with the arrival of young people in large numbers. Naturally and inevitably, in the 1990s, they gradually began entering their retirement age. Consequently, in 2019, the Lower Silesian Voivodship, according to Webb’s classification, was in the group of demographically inactive voivodships—type E, characterized by a regressive type of demographic development (negative birth rate was not compensated for by a positive migration balance) [28].

The growing (for more than two decades!) imbalance in demographic potential between the region’s capital and the other three leading cities also raises great concerns. It should be noted that all three former voivodship cities experienced a significant decline in population between 1995 and 2023.

In the context of depopulation processes, the positive features of the Wroclaw metropolis refer to Wroclaw being described as a crisis-proof city [62]; however, at the same time, the uneven spatial distribution of the region’s demographic resources cannot go unnoticed. On the one hand, today’s Wroclaw meets many criteria for becoming a development pole of international importance [63]. The growing concentration of foreign capital, the rapid growth of the private sector, the quality of the business environment, or Wroclaw’s role as a university city are emphasized. On the other hand, it is important to consider the factors which caused the population decline of former voivodship cities. In view of the future socio-economic development in the region, this fact cannot be downplayed—after all, the most important variables affecting development include, i.a.: the situation of population and the settlement network structure [64]. Wroclaw is also a driving force behind the phenomenon of suburbanization, which is unfavorable from the perspective of pursuing sustainable development. Among other things, an increased share of land planned for residential housing has been observed in the suburban zone of Wroclaw, along with the shrinking areas of arable land [65]. It is worth noting that the population statistics may be underestimated—it is indicated by the scale of construction activity in Wroclaw, suggesting that the city population is growing (the increase may be as high as 200 up to 220 thousand people since 2000). The situation in the city’s surrounding areas should be assessed similarly—suburbanization processes may be even more severe [66].

In an attempt to formulate recommendations aimed at counteracting the identified negative trends of depopulation and the domination of Wroclaw over other cities of the region, the Authors consider it necessary to implement such spatial management and regional policies that ensure a high quality of life for residents of the entire region. It is still people who are essential to the success of the region, despite the progress and changes that have occurred in recent years [67].

It is essential to

- Accelerate investment in transport infrastructure (rail and road) as well as counteract digital exclusion and develop the Internet (especially in mountainous areas, where coverage is often limited). The distance of peripheral counties from Wroclaw should decrease, both in terms of traveling time and data transfer capabilities.

- Apply the financially measurable incentives for investors locating businesses outside Wroclaw area (e.g., local tax reliefs).

- Promote business incubators also in the region’s smaller cities.

- Promote close contacts between educational institutions, universities, and the representatives of local business. Creating internship sites for pupils and students and also including entrepreneurs in Program Councils for a course of study related to their business will produce graduates dedicated to the local labor market needs (rather than the future unemployed).

- Decentralize public institutions: The policy of concentrating offices in the largest cities (and even in the country capital) is typical of Poland. This trend should definitely be reversed.

Unfortunately, errors in regional policy and support for regional development are noticeable in Poland. There are deficiencies even in the functioning of institutions established for this particular purpose—lack of professionals among the decision-makers [68]. In view of the above, it is necessary to recommend that the decision-makers benefit from the scientific studies describing models of the functional–spatial structure as the new elements of the voivodship development strategy [69].

In a long-term perspective, it is also advisable to take a conscious approach to migration—especially in the context of current events in Ukraine [70]—and to further intensify cross-border cooperation [71] while adopting a simultaneous perspective of supra-local development in the country [72].

A comparison of findings regarding demographic resources and the level of tourist function development in Lower Silesian counties points to the phenomenon of overtourism and gentrification [73,74,75]. It is thought-provoking that the Karkonosze County, Jelenia Góra city with county rights, and the Kłodzko County characterized by a high level of the tourist function development are simultaneously significantly affected by depopulation. It seems necessary to focus future studies on the level of municipalities as part of the above-mentioned counties—especially that some municipalities are territorially connected with national parks, which allows for accepting that the interest presented by tourists in this area will continue to grow [76]. Importantly, the source literature offers studies proving the symptoms of overtourism in Wroclaw; however, so far, they have been so insignificant in relation to the conditions of the metropolis functioning that the residents’ life quality has not been negatively affected [77]. It is therefore reasonable to ask how overtourism is evaluated in other counties. After all, depopulating counties with a developed tourist function have been identified in the area under study. Is the depopulation not resulting precisely from the negative effects of the tourist function overdevelopment? These questions seem to be the canvass for future research.

The problem is all the more worthy of interest because the phenomenon of overtourism has still been insufficiently studied in Poland. Some researchers—even in studies published less than 5 years ago!—doubted its existence [78,79]. On the contrary, there are few studies covering metropolises and small cities linked to the naturally valuable areas, in which the problem of overtourism in the Polish tourist space has been emphasized [80,81].

It also seems reasonable to make recommendations regarding the way SP collects and publicizes statistical data. The tourist function keeps evolving, and the ways of collecting data should evolve as well in order to allow better tracking of the phenomenon under study and adapt to the new perspective on tourism statistics [82].

The findings constitute an incentive for the Authors to conduct further analyses covering a comprehensive picture of the population situation and the occurrence of overtourism in the studied area. It seems necessary to analyze the reasons for the depopulation of Lower Silesian counties other than overdevelopment of the tourist function.

5. Conclusions

Lower Silesia, despite its advantages (such as cross-border location and natural and cultural heritage), is facing an increasingly pronounced demographic crisis. After World War II, an almost complete replacement of the population took place. Until the 1990s, a high birth rate was recorded, and since 1998, its decline has been observed, while currently, the deepening process of population aging is very noticeable. Wroclaw (the region’s capital) rebuilt its pre-war demographic potential only in the 1980s, which proves the difficulties in this respect. The conducted research indicates the progressive depopulation of most counties. Only the so-called city-adjacent counties of Wroclaw can be evaluated positively. Unfortunately, uneven development of the leading Lower Silesian cities is also observed, with Wroclaw as the leader, while other urban centers of supra-regional importance (Wałbrzych, Jelenia Góra, Legnica) present a significantly lower demographic potential, and their strength, relative to the voivodeship capital, has been steadily decreasing over the past two decades. It is hard to consider it coinciding with the pursuit of sustainable development in the region—Lower Silesia is moving away from the 11th Goal of balanced development in this regard, rather than approaching it. The forecasts of the Statistics Poland are all the more worrying: they indicate a further concentration of the population around Wroclaw and a deepening depopulation of the periphery, especially medium-sized cities and border counties. This should definitely be assessed as a negative outcome.

The development of the tourist function has traditionally been the most extensive in the Sudetes mountain range and in Wroclaw. In principle, this function is beneficial to the local and regional economy, but in the case of overtourism or tourist gentrification, it can negatively affect the quality of life of permanent residents. The leaders in the realization of the tourist function—as measured by the SDM indicator—are the Karkonosze County and the city of Wroclaw. It should be highlighted that the highest indicators are achieved by the counties linked to national parks and resorts, including Kłodzko County, Lubań County, and Jelenia Góra County. Further development of tourism in the protected and resort areas of Lower Silesia can be expected.

The results of this study confirm the divergent choices of users–residents and users–tourists regarding Lower Silesian counties characterized by the most developed tourist function. This acts as an incentive to break down future studies to the level of municipalities. It is significant that the leaders in terms of the tourist function include the Karkonosze County and Jelenia Góra city with county rights, being, at the same time, the rapidly depopulating counties.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K.-D.; methodology, A.K.-D.; software, M.H.; validation, A.K.-D. and M.H.; formal analysis, K.P. and A.S.; investigation, A.K.-D., M.H. and K.P.; resources, A.S.; data curation, A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K.-D. and A.S.; writing—review and editing, M.H.; visualization, A.S.; supervision, A.K.-D.; project administration, M.H.; funding acquisition, M.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was fully funded by the National Science Centre, Poland, Grant number 2024/53/B/HS6/01241, Grant title: Challenges of Spatial Policy under the conditions of urban Tourism gentrification (SPOT).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LDB SP | Local Data Bank of the Statistics Poland |

| SDM | Synthetic Development Measure |

References

- Jamalishahni, T.; Turrell, G.; Foster, S.; Davern, M.; Villanueva, K. Neighbourhood socio-economic disadvantage and loneliness: The contribution of green space quantity and quality. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, K.W.; Mak, C.M.; Wong, H.M. Effects of environmental sound quality on soundscape preference in a public urban space. Appl. Acoust. 2021, 171, 107570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, K.; Auld, C. Leisure, public space and quality of life in the urban environment. Urban Policy Res. 2003, 21, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabiyeva, G.N.; Wheeler, S.M.; London, J.K.; Brazil, N. Implementation of sustainable development goal 11 (sustainable cities and communities): Initial good practices data. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurumi, Y.; Yamada, T. A framework to assess the local implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 11. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 84, 104002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.L.; Mbah, M.F.; Dinis, M.A.P.; Trevisan, L.V.; de Lange, D.; Mishra, A.; Rebelatto, B.; Ben Hassen, T.; Aina, Y.A. The role of artificial intelligence in the implementation of the UN Sustainable Development Goal 11: Fostering sustainable cities and communities. Cities 2024, 150, 105021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, N.G. Planning Local Economic Development: Theory and Practice; SAGE Publications: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, N.M. Revising classical regional development theories. Informe Gepec 2021, 25, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotti, N.F.; Fratesi, U.; Oberst, C. Regional economic theories as drivers of the EU Cohesion Policy. In EU Cohesion Policy; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 2024; pp. 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jańczak, J. Borders and border dimensions in Europe. Between frontierisation and boundarisation. Public Policy Econ. Dev. 2014, 2, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directorate-General for Migration and Home Affairs. Europe Without Borders. The Schengen Area; European Commission: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2015.

- Furmankiewicz, M.; Buryło, K.; Dostal, I.; Hełdak, M.; Lipsa, J.; Zathey, M. Planning and practice of the development of the Polish-Czech transborder road network: From ineffective top-down plans to bottom-up lack of coordination? Eur. Spat. Res. Policy 2025. in print. [Google Scholar]

- Böhm, H.; Opioła, W. Czech–Polish Cross-Border (Non) Cooperation in the Field of the Labor Market: Why Does It Seem to Be Un-De-Bordered? Sustainability 2019, 11, 2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołodziejczyk, K. Cross-border public transport between Poland and Czechia and the development of the tourism functions of the region. Geogr. Pol. 2020, 93, 261–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furmankiewicz, M.; Buryło, K.; Dołzbłasz, S. From service areas to empty transport corridors? The impact of border openings on service and retail facilities at Polish-Czech border crossings. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2020, 28, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potocki, J.; Kachniarz, M.; Piepiora, Z. Sudetes—Cross-border region? In The International Conference Hradec Economic Days 2014. Economic Development and Management of Regions. Peer-Reviewed Conference Proceedings, Part V; Jedlicka, P., Ed.; Gaudeamus: Hradec Králové, Czech Republic, 2014; pp. 191–200. [Google Scholar]

- Bierwiaczonek, K.; Dymnicka, M.; Kajdanek, K.; Nawrocki, T. Miasto, Przestrzeń, Tożsamość: Studium Trzech Miast: Gdańsk, Gliwice, Wrocław; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar: Warsaw, Poland, 2017; pp. 124–128. [Google Scholar]

- Raport: Przekroje Terenowe (Area Cross-Sections) 1945–1965. Seria “Statystyka Regionalna”; GUS: Warszawa, Poland, 1967; Volume 7.

- Wyrzykowski, J. The Position of Lower Silesia on Domestic and International Tourist Market. Ekon. Probl. Tur. 2014, 4, 417–429. [Google Scholar]

- Stacherzak, A.; Hełdak, M. Uwarunkowania rozwoju turystyki a rozwój gospodarczy obszarów wiejskich Dolnego Śląska. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. We Wrocławiu 2011, 151, 978–987. [Google Scholar]

- Uglis, J.; Jęczmyk, A. Development of the tourist function within areas of lower silesian landscape parks. Econ. Reg. Stud. 2017, 10, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogowska-Sawicz, M. Factors activating the development of towns with a spa and touristic character in Lower Silesia during 2015–2019. Bibl. Reg. 2021, 21, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R. Toward a more comprehensive use of social exchange theory to study residents’ attitudes to tourism. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 39, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraskevaidis, P.; Andriotis, K. Altruism in tourism: Social exchange theory vs altruistic surplus phenomenon in host volunteering. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 62, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabawa, I.W.S.W.; Suwintari, I.G.A.E.; Semara, I.M.T.; Effendie, M.W.; Pertiwi, P.R. Tourist’s Bizarre Behaviors in Bali: Deconstruction of Irritation Index Theory from Gen Z Perspective. Pusaka J. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 7, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieślak, M.; Krupowicz, J.; Kuropka, I.; Radzikowska, B. Procesy Demograficzne w Byłych Województwach Dolnośląskich w Latach 1975–1997; Wydawnictwo Akademii Ekonomicznej im. Oskara Langego we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ciok, S. Rozwój osadnictwa na Dolnym Śląsku po II wojnie światowej. Tendencje i kierunki zmian. In Przemiany Ludnościowo-Osadnicze na Dolnym Śląsku po II Wojnie Światowej; Łoboda, J., Ed.; Acta Universitatis Wratislaviensis. Studia Geograficzne: Wrocław, Poland, 1994; Volume LXI. [Google Scholar]

- Górecka, S.; Kozieł, R.; Tomczak, P. Przemiany demograficzne na Dolnym Śląsku w latach 1999–2007. In Rozprawy Naukowe Instytutu Geografii i Rozwoju Regionalnego Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego; Łoboda, J., Ed.; Dolny Śląsk, Studia Regionalne: Wrocław, Poland, 2009; pp. 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bank Danych Lokalnych—Local Data Bank. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/ (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Organizacja Statystyki Publicznej—Organization of Public Statistics. Available online: https://bip.stat.gov.pl/organizacja-statystyki-publicznej/urzedy-statystyczne (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Słownik Pojęć—Glossary of Statistical Terms. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/metainformacje/slownik-pojec/pojecia-stosowane-w-statystyce-publicznej/listadziedziny.html (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Bal-Domańska, B. Propozycja procedury oceny zrównoważonego rozwoju w układzie presja—Stan—Reakcja w ujęciu przestrzennym. In Taksonomia, Klasyfikacja i Analizadanych—Teoria i Zastosowania; Jajuga, K., Walesiak, M., Eds.; Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2016; Volume 427, pp. 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hellwig, Z. Zastosowanie metody taksonomicznej do typologicznego podziału krajów ze względu na poziom ich rozwoju oraz zasoby i strukturę wykwalifikowanych kadr. Prz. Stat. 1968, 4, 307–327. [Google Scholar]

- Strahl, D. Metody porządkowania liniowego w ocenie rozwoju regionalnego. In Metody Oceny Rozwoju Regionalnego; Strahl, D., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Akademii Ekonomicznej: Wrocław, Poland, 2006; pp. 160–190. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk, A. Geografia Turyzmu (Geography of Tourism); PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lijewski, T.; Mikułowski, B.; Wyrzykowski, J. Geografia Turystyki Polski (Geography of Tourism in Poland); PWE: Warszawa, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Warszyńska, J.; Jackowski, A. Podstawy Geografii Turyzmu (Basics of Tourism Geography); PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Marković, S.; Perić, M.; Mijatov, M.; Doljak, D.; Žolna, M. Application of tourist function indicators in tourism development. J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijić SASA 2017, 67, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krukowska, R.; Świeca, A. Tourism function as an element of regional competitiveness. Pol. J. Sport Tour. 2018, 25, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szromek, A. Przegląd wskaźników funkcji turystycznej i ich zastosowanie w ocenie rozwoju turystycznego obszaru na przykładzie gmin województwa śląskiego. Zesz. Naukowe. Organ. i Zarządzanie/Politech. Śląska 2012, 61, 295–309. [Google Scholar]

- Štefko, R.; Vašaničová, P.; Litavcová, E.; Jenčová, S. Tourism intensity in the NUTS III regions of Slovakia. J. Tour. Serv. 2018, 9, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulczyk-Dynowska, A. Parki Narodowe a Funkcje Turystyczne I Gospodarcze Gmin Terytorialnie Powiązanych; Wydawnictwo UPWr: Wrocław, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kukuła, K. Metoda unitaryzacji zerowanej na tle wybranych metod normowania cech diagnostycznych. Acta Sci. Acad. Ostroviensis 1999, 4, 5–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kukuła, K. Zero unitarisation method as a tool in ranking research. Econ. Sci. Rural. Dev. 2014, 36, 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, D.; Singh, B. Feature wise normalization: An effective way of normalizing data. Pattern Recognit. 2022, 122, 108307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocznik Statystyczny woj. Dolnośląskiego 2023 (Statistical Yearbook of the Lower Silesian Voivodeship); GUS: Warszawa, Poland, 2023.

- Portal Statystyczny. Available online: https://portalstatystyczny.pl (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Rocznik Statystyczny woj. Dolnośląskiego 2015. (Statistical Yearbook of the Lower Silesian Voivodeship); GUS: Warszawa, Poland, 2015; Volume I.

- Korenik, S. Znaczenie dużych miast w rozwoju Dolnego Śląska—Wybrane uwagi. In Obszary Metropolitarne, a Rozwój Regionalny i Lokalny; Szołek, K., Zakrzewska-Półtorak, A., Eds.; Biblioteka Regionalistyki: Wrocław, Poland, 2004; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Jaskulowski, K.; Pawlak, M. Migration and lived experiences of racism: The case of high-skilled migrants in Wrocław, Poland. Int. Migr. Rev. 2020, 54, 447–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolińska, K.; Makaro, J. O Wielokulturowości Monokulturowego Wrocławia; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego: Wrocław, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sanetra-Szeliga, J. Culture and heritage as a means to foster quality of life? The case of Wrocław European Capital of Culture 2016. Taylor Fr. J. 2022, 30, 514–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwanicki, G.; Dłużewska, A. Potential of city break clubbing tourism in Wrocław. Bull. Geogr. Socio-Econ. Ser. 2015, 28, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Brzuśnian, A. Wrocław jako przykład miasta inteligentnego. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. We Wrocławiu 2017, 470, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rocznik Statystyczny woj. Dolnośląskiego (Statistical Yearbook of the Lower Silesian Voivodeship) 2024; GUS: Warszawa, Poland, 2024.

- Kociszewski, J. Proces i efekty restrukturyzacji społeczno-gospodarczej Dolnego Śląska w przechodzeniu do gospodarki rynkowej. In Problemy Społeczne Dolnego Śląska; Ostasiewicz, W., Pisz, Z., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Instytut Śląski: Opole, Poland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Miasta na Prawach Powiatu w Województwie Dolnośląskim w 1998 r. (Cities with County Rights in Lower Silesian Voivodeship in 1998); Urząd Statystyczny we: Wrocławiu, Poland, 1999.

- Rocznik Statystyczny 1961; GUS: Warszawa, Poland, 1961.

- Portrety Regionów Polskich (Portraits of Polish Regions); GUS: Warszawa, Poland, 2003.

- Report: Procesy Demograficzne w Województwie Dolnośląskim w Latach 2010–2019 oraz w Perspektywie do 2040 r. (Demographic Processes in the Lower Silesian Voivodeship in 2010–2019 and Through to 2040; GUS: Wrocław, Poland, 2020. Available online: https://wroclaw.stat.gov.pl/opracowania-biezace/opracowania-sygnalne/ludnosc/procesy-demograficzne-w-wojewodztwie-dolnoslaskim-w-latach-2010-2019-oraz-w-perspektywie-do-2040-r-,3,2.html (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Gryszel, P. Możliwości kreowania markowych produktów turystycznych na Dolnym Śląsku. In Gospodarka Turystyczna; Rapacz, A., Ed.; Prace Naukowe AE; Wydawnictwo Akademii Ekonomicznej we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2005; Volume 1067, pp. 158–169. [Google Scholar]

- Miszczak, K. Wrocław miastem odpornym na kryzys? Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. We Wrocławiu 2017, 490, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Książek, S.; Suszczewicz, M. City profile: Wrocław. Cities 2017, 65, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnicki, Z.; Czyż, T. Główne aspekty regionalnego rozwoju społeczno-gospodarczego. In Rozwój Regionalny i Lokalny w Polsce w Latach 1989–2002; Parysek, J., Ed.; Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Poznań, Poland, 2004; pp. 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Tokarczyk-Dorociak, K.; Kazak, J.; Szewrański, S. The impact of a large city on land use in Suburban area–the case of Wrocław (Poland). J. Ecol. Eng. 2018, 19, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmytkie, R. Suburbanisation processes within and outside the city: The development of intra-urban suburbs in Wrocław, Poland. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2021, 29, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korenik, S. Czynniki i Bariery Rozwoju Regionalnego w Nowych Uwarunkowaniach; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Parteka, T. Rola instytucji wspierających rozwój regionalny (w tym agencji rozwoju regionalnego) w systemie wdrażania nowej polityki regionalnej. Koncepcje Nowej Polityki Reg. Ekspert. 2009, 153–174. [Google Scholar]

- Kafka, K. Model struktury funkcjonalno-przestrzennej jako element strategii rozwoju województwa. Rozw. Reg. Polityka Reg. 2025, 18, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janicki, W. Polityka migracyjna jako narzędzie wspierania rozwoju regionalnego. Stud. Migr.-Przegląd Pol. Migr. Stud.–Rev. Pol. Diaspora 2024, 193, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowski, A.; Dołzbłasz, S.; Komornicki, T.; Matczak, R.; Raczyk, A.; Wiśniewski, R.; Zaucha, J. New direcons of cross-border cooperation in Poland in the context of changing conditions: 2021–2027 and post-2027 programming periods. Policy Brief Comm. Spat. Econ. Reg. Plan. Pol. Acad. Sci. 2024, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Maleszyk, P.; Szafran, J. Strategia rozwoju ponadlokalnego jako nowy instrument zintegrowanego planowania–doświadczenia i rekomendacje. Rozw. Reg. Polityka Reg. 2024, 70, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruczek, Z. Turyści vs. mieszkańcy. Wpływ nadmiernej frekwencji turystów na proces gentryfikacji miast historycznych na przykładzie Krakowa. Tur. Kult. 2018, 3, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Główczyński, M. Gentryfikacja miast–przegląd literatury polskiej i zagranicznej. Rozw. Reg. Polityka Reg. 2017, 39, 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kruczek, Z.; Walas, B.; Chromy, J. Od euforii do irytacji. Analiza postaw mieszkańców Krakowa, hotelarzy i restauratorów wobec dalszego rozwoju turystyki. In Sport i Turystyka w Perspektywie Nauk Społecznych: Tradycje i Współczesność; Zowiosło, M., Kosiewicz, J., Eds.; Akademia Wychowania Fizycznego w Krakowie: Kraków, Poland, 2019; pp. 287–298. [Google Scholar]

- Rogowski, M.; Zawilińska, B.; Hibner, J. Managing tourism pressure: Exploring tourist traffic patterns and seasonality in mountain national parks to alleviate overtourism effects. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedyk, W.; Sołtysik, M.; Olearnik, J.; Barwicka, K.; Mucha, A. How overtourism threatens large urban areas: A case study of the city of Wrocław, Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozmiarek, M. Overtourism a interakcja w lefebrowskiej perspektywie. Change 2021, 8, 523–538. [Google Scholar]

- Zmyślony, P.; Pilarczyk, M. Identification of overtourism in Poznań through the analysis of social conflicts. Stud. Perieget. 2020, 2, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szromek, A.R.; Kruczek, Z.; Walas, B. The Attitude of Tourist Destination Residents towards the Effects of Overtourism—Kraków Case Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raszka, B.M.; Hełdak, M.; Ogórka, K.; Janik, W. Overtourism na obszarach chronionych na przykładzie Karkonoskiego Parku Narodowego oraz Szklarskiej Poręby. Tur. Kult. 2025, 1, 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basera, V.; Batinoluho, L. The Future Perspective of Tourism Statistics. J. Tour. Q. 2025, 7, 56–60. Available online: http://htmjournals.com/jtq/index.php/jtq/article/view/94 (accessed on 3 March 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).