Abstract

This study investigates the environmental and socioeconomic dimensions of domestic cycling tourism in Slovenia, focusing on “double pollution” and “greenhushing” practices. The aim is to evaluate the sustainability of cycling tourism by examining its indirect environmental impacts, particularly emissions from ancillary travel behaviours such as car usage to reach cycling destinations. Utilizing data from 2011 to 2021, this research employs factor analyses using the principal component analysis (PCA) extraction method and vector autoregression (VAR) modelling to explore relationships between key socioeconomic, environmental, and tourism-related variables. This study identifies three common factors influencing cycling tourism: (1) socioeconomic and urban dynamics, (2) tourism-driven environmental factors, and (3) climatic sustainability challenges. Results highlight that cycling tourism contributes to emissions due to associated car travel, counteracting its eco-friendly image. Findings reveal that favourable economic conditions and urbanisation drive tourism demand, while increased tourist arrivals correlate with higher emissions. This study also uncovers greenhushing, where stakeholders underreport the environmental costs of cycling tourism, leading to mistaken perceptions of its sustainability. This study concludes that, while domestic cycling tourism supports economic growth and health, its environmental benefits are compromised by ancillary emissions. Transparent environmental reporting, enhanced public transport, and local bike rental systems are recommended to mitigate these challenges and align cycling tourism with Slovenia’s sustainability goals.

Keywords:

bicycles; greenwashing; greenhushing; sustainability; tourism; vector autoregression (VAR) 1. Introduction

Tourism has long served as a cornerstone of economic growth, cultural exchange, and regional development, making significant contributions to the economies of both developed and developing nations. Among the various forms of tourism, domestic cycling tourism has recently gained prominence as a noteworthy sector that aligns closely with the principles of sustainable travel. Unlike motorised tourism, domestic cycling tourism is celebrated for its minimal ecological footprint and for fostering a deeper connection between travellers and the natural environment. By cycling, tourists immerse themselves more fully in their surroundings, often gaining a richer and more authentic experience of local culture, natural landscapes, and regional heritage. Additionally, domestic cycling tourism enhances the health and well-being of travellers, integrating physical activity as a fundamental aspect of their travel experience [1,2].

In Slovenia, domestic cycling tourism [3] has received significant attention due to the country’s natural landscapes, commitment to environmental sustainability, and proactive approach to green tourism initiatives. With its picturesque scenery, mountainous terrain, and extensive network of cycling paths, Slovenia offers an ideal environment for cycling enthusiasts. Collaborating with local tourism operators, the Slovenian government actively promotes cycling as a sustainable travel option, aligning with the nation’s long-term sustainability objectives. This dedication to domestic cycling tourism aims to mitigate the environmental impact of traditional tourism while fostering regional economic growth and supporting local communities. However, as domestic cycling tourism expands in Slovenia, it raises questions about its overall environmental impact. While cycling itself is low-emission, the travel habits of tourists—often involving car journeys to reach cycling destinations—add additional environmental costs, raising concerns about the genuine sustainability of domestic cycling tourism.

1.1. Greenhushing and Double Pollution in Domestic Cycling Tourism—Motivation of This Study

The environmental ramifications of domestic cycling tourism present a nuanced landscape, as many tourists depend on motor vehicles to transport their bicycles to various destinations. This phenomenon raises a paradox: although cycling is inherently eco-friendly, the vehicular travel required to access cycling locales contributes to emissions that may counteract the environmental advantages of cycling. The concept of “double pollution” arises when tourists engage in both car and bicycle use, culminating in a net increase in carbon emissions [4]. Such a dual impact complicates the conventional domestic cycling tourism narrative, challenging the presumption that it remains a sustainable alternative.

Empirical studies demonstrate that vehicle emissions, mainly from personal automobiles, significantly exacerbate air pollution and augment carbon footprints in regions densely populated by tourists [5]. This issue becomes particularly salient in Slovenia, as numerous cycling tourists resort to driving to picturesque areas with limited public transportation options. Consequently, the overall environmental benefits attributed to domestic cycling tourism may be compromised, thereby raising critical inquiries regarding the alignment of domestic cycling tourism with Slovenia’s sustainability objectives. This research endeavours to investigate the extent to which domestic cycling tourism in Slovenia contributes to double pollution, seeking to elucidate the impact of such emissions on the overarching environmental consequences of tourism and exploring the potential for alternative travel practices to mitigate these effects [6].

The proliferation of domestic cycling tourism has engendered heightened scrutiny regarding the portrayal of its environmental impacts. Traditionally, tourism operators and marketers accentuate the sustainable attributes of domestic cycling tourism, often neglecting or minimising the environmental costs associated with travel behaviours, notably car usage. This phenomenon, termed “greenhushing”, involves deliberately underrepresenting or omitting specific environmental impacts to maintain a favourable public perception [7]. In domestic cycling tourism, greenhushing may manifest when tourism operators emphasise the eco-friendly essence of cycling while failing to acknowledge the emissions resulting from car travel that typically precede cycling activities. This results in stakeholders—including policymakers, consumers, and local communities—receiving an incomplete understanding of the environmental burdens tied to domestic cycling tourism [8].

Greenhushing presents substantial challenges for sustainable tourism frameworks, as it obfuscates the comprehensive scope of environmental impacts, potentially leading to deficiencies in policy development and strategic planning. Without transparent and thorough reporting, accurately assessing the true sustainability of tourism practices becomes increasingly arduous, potentially leading to ill-informed policy decisions [9]. This research explores the prevalence of greenhushing within Slovenia’s domestic cycling tourism sector, evaluating whether the environmental repercussions stemming from associated travel behaviours are underreported. A comprehensive understanding of greenhushing practices is imperative for constructing precise sustainability assessments and ensuring domestic cycling tourism effectively aligns with broader environmental objectives.

The motivation for this study stems from the intricate dual role of domestic cycling tourism. While it is marketed as an environmentally sustainable alternative, it may inadvertently lead to environmental degradation due to accompanying travel behaviours [10]. This phenomenon, called double pollution—where tourists use both cars and bicycles—necessitates thoroughly examining the net environmental benefits of domestic cycling tourism. By investigating whether emissions from car travel substantially counteract the sustainability advantages of cycling, this research tries to provide a balanced perspective on the environmental impact of domestic cycling tourism.

Furthermore, the concept of greenhushing offers a compelling area for exploration. As public awareness of greenwashing—the practice where companies inflate their environmental commitments—has increased, greenhushing has become a more subtle but equally significant issue. Unlike greenwashing, which involves false or exaggerated claims, greenhushing refers to the selective withholding of information. In the context of domestic cycling tourism, this may include omitting details about the environmental costs of travelling to cycling destinations, thereby creating a misleading impression of sustainability. Understanding the practices related to greenhushing is essential for ensuring that the ecological impacts of domestic cycling tourism are fully disclosed.

1.2. Objectives of This Study

This study aimed to investigate several socioeconomic and environmental variables of domestic cycling tourism in Slovenia. The primary goal was to analyse the relationship between domestic cycling tourism demand and factors of cycling tourism on Slovenia’s sustainability goals. In particular, this research sought to determine whether domestic cycling tourism, accounting for all associated travel behaviours, has a net positive or negative effect on environmental sustainability.

Specific objectives included the following: First, reviewing existing research on greenhushing in tourism, which included analysing how environmental impacts are reported in previous studies and identifying the gaps in disclosure of domestic cycling tourism. Second, determining the key variables influencing domestic cycling tourism. This objective involved cataloguing the factors typically associated with tourism’s environmental impact, such as CO2 emissions from transportation, urbanisation levels, and investments in environmental protection. These variables provided a foundation for examining domestic cycling tourism’s broader environmental footprint. Third, assessing potential biases in previous research on domestic cycling tourism’s environmental impact. This objective sought to determine whether past studies might have presented a skewed or incomplete view of cycling tourism’s sustainability, particularly concerning travel-related emissions. It involved critically analysing existing literature and environmental reports to identify any inconsistencies or omissions in reported data. And, fourth, investigating whether domestic cycling tourism leads to double pollution.

1.3. Research Gap and Development of Hypotheses

This study aimed to clarify the environmental impacts of cycling-based tourism in Slovenia, challenging the belief that cycling-related travel is inherently eco-friendly. While domestic cycling tourism encourages low-impact travel, evidence suggests that associated travel practices, such as driving to cycling destinations, can diminish its environmental benefits. Therefore, the literature gap is regarding the environmental impact of cycling tourism with its direct and indirect effects. It is threefold [11]. First, while existing research extensively highlights the economic, health, and sustainability benefits associated with cycling tourism, it often overlooks the hidden environmental costs related to ancillary travel behaviours, such as car usage, to reach cycling destinations [12]. This oversight challenges the common perception that cycling tourism is inherently environmentally friendly. Second, the concept of “double pollution”, which encompasses emissions from car travel and cycling activities, has received limited attention in the literature [13,14]. Third, while the issue of greenwashing has been widely discussed, the more subtle practice of “greenhushing”—the intentional underreporting of negative environmental impacts—has yet to be thoroughly examined within the context of cycling tourism [7,15]. This research addresses these gaps by critically analysing the dual environmental impact of cycling tourism and assessing the prevalence of greenhushing practices in Slovenia’s tourism sector. In doing so, it offers a more nuanced perspective on the sustainability of cycling tourism, challenging oversimplified assumptions and promoting a more transparent and comprehensive approach to sustainable tourism research and policy development [16,17].

This study contributes to sustainable tourism literature by conceptualising and empirically validating the “double pollution” phenomenon, highlighting the dual environmental impact of ancillary car travel and cycling activities. It also advances the discourse on “greenhushing”, revealing its role in underreporting tourism-related environmental costs.

By examining and following existing literature and theoretical frameworks, we derived and set two hypotheses (H) and a research question (RQ). They are ultimately proposing a refined research inquiry of “double pollution” (i.e., emissions resulting from both car travel and cycling) and the concept of “greenhushing” within the tourism sector.

Socioeconomic and Environmental Determinants of Domestic Cycling Tourism Demand: Previous research indicates that the demand for tourism, particularly cycling-based travel, is influenced by various socioeconomic and environmental factors. Economic indicators, such as real GDP and real income levels, are crucial in determining the affordability of leisure activities, thereby affecting tourism demand. Socioeconomic factors, including educational attainment and urban population density, also play a significant role in shaping preferences for cycling as a mode of travel, as more highly educated populations tend to exhibit greater environmental awareness and health consciousness. Additionally, environmental conditions, such as average temperature and sunshine hours, directly impact outdoor activities, with favourable weather conditions often boosting tourism demand.

In light of these considerations, we hypothesised that socioeconomic and environmental variables significantly influence the demand for domestic cycling tourism in Slovenia.

H1.

Socioeconomic and environmental factors, including real GDP, urban population density, and climate conditions, significantly affect the demand for domestic cycling tourism in Slovenia.

Double Pollution from Cycling-Based Tourism: Cycling tourism is often perceived as a low-impact, eco-friendly mode of travel, but the reality is more complex when considering related travel behaviours. Many tourists use private vehicles to transport bicycles to cycling destinations, particularly on weekends or leisure trips, mostly domestic tourists. This practice results in “double pollution”, where car usage and cycling contribute to carbon output, negating some of the environmental benefits of domestic cycling tourism. We proposed the following hypothesis to examine whether domestic cycling tourism in Slovenia indeed results in double pollution:

H2.

Cycling-based tourism in Slovenia significantly contributes to double pollution due to the combined outputs from car travel to cycling sites and activities.

Research Question

Greenhushing, a term describing companies’ tendency to downplay or conceal information on their sustainability actions to avoid scrutiny or critique, is an emerging issue in environmental disclosures. In domestic cycling tourism, greenhushing may occur when tourism operators promote the eco-positive aspects of domestic cycling tourism while omitting negative environmental impacts, such as emissions from car travel, to reach cycling areas.

The concept of greenhushing suggests that certain aspects of domestic cycling tourism’s environmental footprint may be systematically underreported or omitted from public discussions. This selective disclosure creates an incomplete picture of domestic cycling tourism’s true sustainability, potentially misleading consumers and policymakers. Studies on greenwashing have shown that such practices can erode public trust, and greenhushing, though less overtly deceptive, has similar effects regarding reduced transparency and accountability. Considering this context, we proposed the following hypothesis:

RQ: Based on factor analyses using the PCA extraction method and VAR modelling results, greenhushing practices in Slovenia’s tourism sector lead to double pollution ethics.

This study is organised into the following sections. The Section 2 situates the research within the existing body of knowledge on sustainable tourism, with particular attention to greenhushing and the environmental ramifications of domestic cycling tourism. The Section 3 delineates the research design, detailing the econometric techniques and data sources employed throughout this study. Factor analyses using the principal factor analysis (PCA) extraction method were utilised to ascertain critical environmental and socioeconomic determinants, while VAR was used to examine the dynamic interrelationships among these variables. The Section 4 presents the empirical findings derived from the factor analyses using the PCA extraction method and VAR models, scrutinising the influence of domestic cycling tourism on various environmental indicators. In Section 5, the findings are interpreted through the lens of the greenhushing phenomenon of domestic cycling tourism. The Section 6 synthesises this study’s findings and puts policy recommendations for policymakers and practitioners within the tourism sector. This study aspires to contribute meaningfully to the discourse on sustainable tourism by furnishing a more nuanced perspective on the environmental impact of domestic cycling tourism.

2. Literature Review

This literature review analyses existing research on domestic cycling tourism, focusing on its environmental and socioeconomic aspects while also considering potential drawbacks, notably its indirect environmental impacts. To understand the environmental footprint of domestic cycling tourism, this research incorporates studies on greenwashing and greenhushing within the tourism sector, emphasising how selective reporting can obscure the true effects of tourism (sports) activities. By assessing key methodological approaches and pinpointing research gaps, this section aims to establish a foundation for examining domestic cycling tourism’s dual role as both a sustainable practice and a potential source of pollution linked to ancillary travel behaviours.

2.1. Sustainable Tourism and Environmental Impact

The evolution of sustainable tourism practices has emerged as a significant focal point in tourism studies since the 1990s, fuelled by an escalating awareness of tourism activities’ ecological and social ramifications. Refs. [18,19] were pioneers advocating for sustainable tourism practices, promoting a tourism model that respects natural resources, conserves biodiversity, and minimises pollution. In alignment with these early frameworks, the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) established guidelines emphasising that genuine sustainability in tourism must encompass not only economic factors but also environmental and social dimensions [20]. Within this context, domestic cycling tourism has garnered increasing attention for its potential to align with sustainable tourism principles.

Cycling tourism inherently changes reliance on motorised vehicles, mitigates noise pollution, and is characterised by a limited carbon footprint [21,22]. Scholars contend that cycling facilitates a slower travel pace, which fosters deeper engagement with local cultures and natural environments, enhances cultural exchange, and encourages preservation efforts [23,24]. The authors of [25,26] cautioned that all forms of tourism contribute to carbon emissions—directly or indirectly—thereby complicating the assessment of the actual environmental impact of cycling tourism.

As global interest in sustainable tourism intensifies [27,28], the popularity of cycling tourism has surged [29], with governmental entities increasingly promoting it as a viable alternative to car-based travel. In Slovenia, for instance, cycling tourism aligns with national sustainability, whereby cycling initiatives bolster eco-friendly travel while simultaneously stimulating local economies. Nonetheless, some scholars argue that associated emissions may obscure the perceived sustainability of cycling, particularly those arising from automobile travel to cycling destinations, and authors refer to them as “ancillary emissions [30,31]”. These emissions challenge the perception of cycling as inherently low-impact, indicating that a comprehensive evaluation of its sustainability necessitates considering these indirect factors [32].

2.2. Cycling Tourism: Economic, Social, and Environmental Benefits

Cycling tourism extends its benefits beyond environmental sustainability, significantly enhancing local economies, promoting health, and fostering social dynamics. Research by the authors of [33] underscores the economic potential of cycling tourism, illustrating how bicycle-friendly destinations attract tourists who invest considerable time and financial resources within local communities. This patronage supports small businesses and local services, thus contributing to economic vitality. The authors of [34,35,36] further assert that cycle tourists often pursue distinctive experiences, which leads them to explore rural environments, interact with local enterprises, and ultimately stimulate rural economic development. Such economic advantages highlight that cycling tourism is a model of environmentally conscious travel and a mechanism for economic empowerment, particularly for regions that may otherwise struggle to attract visitors.

Regarding health benefits, cycling tourism encourages physical well-being by facilitating active travel. Authors found that the physical activity associated with cycling is instrumental in mitigating stress, enhancing mental health, and contributing to an enriching travel experience, which aligns with broader public health objectives. Socially, cycling tourism fosters unique interactions with local communities, thus creating avenues for cultural exchange and mitigating the alienation frequently associated with conventional tourism modalities. These characteristics render cycling tourism attractive for those seeking genuine and sustainable travel experiences. Nevertheless, the environmental implications of cycling tourism are inherently complex. While cycling is widely recognised as a low-impact mode of transportation, others contend that tourists often resort to vehicular travel to access cycling destinations, resulting in emissions that undermine the purported sustainability of cycling tourism. This phenomenon, termed “double pollution”, reveals a paradox where the environmentally friendly practice of cycling is compromised by the ecological costs associated with commuting to and from cycling locales. The concept of double pollution underscores the necessity for a nuanced comprehension of the sustainability of cycling tourism, one that encompasses both its direct and indirect environmental impacts [37,38,39].

2.3. Greenwashing and Greenhushing in Cycling Tourism

The concepts of greenwashing and greenhushing are crucial in discussions of tourism sustainability. Greenwashing involves misleading consumers about the environmental benefits of a product or service and is prevalent in tourism, where operators promote eco-friendly practices while downplaying negative impacts, such as transportation.

In contrast, greenhushing involves companies intentionally minimising their sustainability achievements to circumvent scrutiny. For example, operators may fail to disclose the emissions from travel to cycling destinations in cycling tourism, creating a distorted view of cycling as a fully sustainable practice. Greenhushing is particularly common in eco-friendly sectors, where companies fear full disclosure could harm their reputation [40].

The increasing prevalence of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) reporting in the business world offers investors valuable information about the environmental impact of companies. However, in contrast to financial reporting, ESG reporting currently lacks strict standards, which can result in inconsistencies and the problem of greenwashing. Greenwashing involves falsely portraying a company as more sustainable than it is through misleading information or setting unrealistic sustainability targets. Regulators are increasingly vigilant about greenwashing, and investors are taking note. The EU has introduced proposed regulations to enhance the transparency and comparability of ESG information in financial products. Companies must establish a strong ESG governance program, provide ESG training for their teams, keep up with regulatory changes, anticipate and plan for potential greenwashing risks, and prioritise transparency in their ESG reporting to foster trust and create value.

On the other hand, greenhushing is when a company chooses not to publicise its ESG information due to concerns about stakeholder reactions and investor perceptions. Although not openly deceitful, greenhushing restricts the amount and calibre of accessible information. This lack of transparency makes it difficult to assess corporate climate goals and exchange decarbonisation best practices [41,42].

Swestiana et al. [43] delve into the effects of greenwashing and greenhushing on tourist trust within the volunteer tourism (VT) context. Greenwashing, characterised by companies’ exaggerated environmental claims, has eroded tourist trust. In contrast, greenhushing, which involves a subtler approach to green communication, is presented as a viable option for smaller VT operators. Their research employed a quasi-experimental design involving international students to compare levels of trust between greenwashing and greenhushing. Their findings suggest that greenhushing strategies engender greater trust, hinting at their potential to be more impactful in promoting sustainable tourism.

The article [44] delves into the growing issue of deceptive marketing tactics employed by companies that tout themselves as “carbon-neutral” or “net zero” by utilising carbon credits in voluntary carbon markets. These credits often lack reliability, as they do not guarantee permanent carbon removal, thereby contributing to what is known as “climate washing”. The article examines the existing consumer protection laws and ongoing legal actions related to these misleading assertions, underscoring the challenges in regulating carbon-neutral marketing. It advocates for more stringent regulations and improved consumer awareness to ensure genuine corporate climate commitments and shield consumers from deceptive environmental advertising.

The article [45] explores the growing significance of domestic cycling tourism as an alternative and sustainable tourism form. It highlights cycling’s economic, health, and environmental benefits and its role in promoting sustainable tourism practices. Their study reviews the development of domestic cycling tourism globally, the impact of bike-sharing systems, and the economic aspects of domestic cycling tourism. It emphasises the need for improved infrastructure and strategic planning to enhance domestic cycling tourism, making it an integral part of sustainable development and local cultural experiences.

Despite the growing body of literature on domestic cycling tourism [37], research gaps persist, particularly concerning the environmental drawbacks associated with ancillary travel behaviours. It is necessary to account for indirect emissions in tourism research; however, no studies have explicitly addressed the concept of “double pollution” in domestic cycling tourism. This notion, which encompasses the combined use of cars and bicycles, introduces an additional layer of complexity that challenges the assumption that domestic cycling tourism is inherently sustainable. Greenhushing is common in eco-conscious sectors, as companies are reluctant to disclose negative environmental consequences [46].

3. Materials and Methods

This methodology and data section describes the data sources, variables, and econometric methods used to analyse the environmental and socioeconomic impacts of domestic cycling tourism in Slovenia. This study aimed to evaluate the dual environmental impact of domestic cycling tourism—both its eco-friendly and potentially polluting aspects. To achieve this, we utilised a combination of factor analyses using the PCA extraction method and vector autoregression (VAR) to explore the relationships among various determinants, focusing mainly on variables related to tourism demand, environmental indicators, socioeconomic factors, and potential “double pollution” associated with car use in domestic cycling tourism.

3.1. Data

The primary data for this study were derived from the Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia (SORS), supplemented by data from Statista. The dataset spanned from 2011 to 2021, providing a comprehensive overview of tourism and environmental variables over 11 years. This period allowed us to analyse trends before, during, and after significant global events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, which had notable impacts on travel behaviours and environmental indicators. The data were reported annually, with each variable captured yearly.

3.1.1. Tourism-Related Variables and Motorisation Variables

The variables included in Table 1 are TA_SI, the total tourist arrivals in Slovenia, indicating the level of tourism demand; CAR_1000inhab, which is the number of cars per 1000 inhabitants, showing car dependency in the population; CAR_1000INHAB_LJ, the motorisation rate specifically in Ljubljana, the capital, reflecting urban car usage; CAR_1000INHAB_NM, which is the motorisation rate in Novo Mesto, providing a comparison with Ljubljana; and CAR_OLD, the average age of cars, with older cars generally emitting more pollutants.

Table 1.

Tourism and Motorisation Indicators.

Table 1 offers valuable insights into the relationship between tourism and car dependency in Slovenia, two critical factors for understanding the environmental impact of domestic cycling tourism, which is calculated from the model:

where is a new defined variable for cycling tourism in Slovenia, is the number of domestic tourist arrivals in Slovenia, and is the number of bikes imported into Slovenia.

Data on tourist arrivals (TA_SI) highlight Slovenia’s appeal as a travel destination, while motorisation rates (CAR_1000inhab) reveal the population’s reliance on private vehicles, particularly in urban areas such as Ljubljana (CAR_LJ) and Novo Mesto (CAR_NM). The age of the vehicle fleet (CAR_OLD) is included, as it influences emissions; older cars tend to generate more pollution. By analysing these indicators, researchers can investigate how rising tourism might indirectly affect the environment through increased car usage. This table aids in identifying trends in car dependency, urban motorisation, and their potential connections to domestic cycling tourism.

3.1.2. Environmental Variables

The variables included in Table 2 are CO2_newCAR, which is the average CO2 emissions per kilometre from new passenger cars, indicating pollution from vehicle use; CO2_Gg_Residents, which is CO2 emissions attributed to Slovenian residents, measured in gigagrams, to show local environmental impact; CO2_Gg_nonresidents, the CO2 emissions from non-residents, offering insights into tourism-related emissions; N2O_tones, which is nitrous oxide emissions in tons, a measure of greenhouse gases that contribute to climate change; and CH4_tones, which is methane emissions in tons, representing another potent greenhouse gas.

Table 2.

Environmental and Emission Indicators.

The environmental indicators table details key pollution metrics associated with transportation and tourism. It includes CO2 emissions from residents and non-residents, reflecting the environmental burden of local and tourist activities in Slovenia. Table 2 is crucial for comprehending the broader environmental impact of domestic cycling tourism, particularly given that car emissions significantly contribute to pollution. It also presents data on nitrous oxide and methane emissions, drawing attention to additional greenhouse gases influenced by tourism activities. By examining these variables, the table enables researchers to investigate the dual pollution phenomenon, where tourists travel by car before transitioning to bicycles, and to evaluate Slovenia’s emissions within the context of tourism.

3.1.3. Urbanisation, Population, and Education Variables

The variables included in Table 3 are UPRSCH, which is the population without primary school education, reflecting educational disparities; PRSCH, the population with primary school education, indicating basic educational attainment; SSCH, which is the population with secondary school education, marking mid-level education; UNI_1, UNI_2, UNI_3, which are the number of university graduates by cycle (first, second, and third), showing advanced educational attainment; and URB, which is the urban population, indicating urban density and potential tourism demand.

Table 3.

Education and Demographic Indicators.

The education and demographic indicators table offers valuable insights into the socioeconomic profile of Slovenia. It presents data on educational attainment across various levels, from primary to higher education. Data on the urban population are included, illustrating population density that may correlate with infrastructure supporting domestic cycling tourism. GDP data add context to the economic conditions, enabling an exploration of how financial stability can influence educational outcomes and urban development. This table is a crucial resource for understanding the social and demographic landscape in which domestic cycling tourism occurs, highlighting how education levels and urbanisation may impact environmental awareness, tourism behaviour, and recreational preferences among residents and visitors.

3.1.4. Public Transport, Weather, and Meteorological Variables

The variables included in Table 4 are Tis, the average annual temperature, which may affect tourism seasonality; PRECI, the precipitation levels, potentially impacting outdoor activities like cycling; SUN_DAY, which is total sunshine hours, a factor in promoting outdoor tourism; SNOW_DAYS, the days with snowfall, indicating seasonal weather conditions; TRAVEL, which is total bus rides, suggesting reliance on public transport; TRAVEL_CITY, which is city-specific bus rides, showing urban transport usage; and TRAVEL_TRAIN, which is train rides, an alternative to car travel for tourists.

Table 4.

Weather and Travel Indicators.

The weather and travel indicators table emphasises the environmental and transportation conditions that influence tourism. Weather data—temperature, precipitation, sunshine, and snowfall—reflect Slovenia’s climate, affecting tourism seasonality and outdoor activities. Additionally, the table provides insights into public transportation usage, detailing the number of bus and train rides and highlighting the accessibility and popularity of public transit among locals and tourists. This information is crucial for understanding how environmental factors and transportation options shape tourism behaviour. High public transport usage may indicate a reduced reliance on cars, potentially leading to lower tourism-related emissions and promoting more sustainable domestic cycling tourism practices.

3.1.5. Economic and Financial Variables

In Table 5, the variables included are BIK_euro, the total bicycle expenditures expressed in euros, indicating the popularity and market size of cycling in Slovenia; BIK, the number of bike imports; BIK_HS, the household ownership of bikes as a percentage; GDP_R, the real gross domestic product, showing Slovenia’s annual economic performance; INV_ENV_SI_euro, the total of investments in environmental protection, representing the country’s commitment to sustainability; and INV_ENV_SI_state_euro, which is state-specific investments in environmental protection, reflecting government allocations toward environmental goals.

Table 5.

Economic Indicators.

The economic indicators in Table 5 offer valuable insights into the financial landscape of domestic cycling tourism in Slovenia. The table highlights annual bicycle spending and captures essential economic measures such as GDP influencing tourism and recreational activities. Investments in environmental protection, both at the state level and in total, reflect Slovenia’s commitment to sustainability, potentially attracting eco-conscious tourists and benefiting domestic cycling tourism. This table illustrates the connection between economic prosperity and the growth of domestic cycling tourism, revealing trends in how economic well-being and environmental dedication may drive interest in sustainable tourism practices. Overall, it provides a solid foundation for examining the role of economic factors in the evolving landscape of domestic cycling tourism.

3.1.6. Road Safety and Health Variables

Table 6 includes variables such as LEA_days, which is the average number of days lost to illness per employee; DEA_10000_inhab, which is the number of road fatalities per 10,000 inhabitants; EMPLOY_SI, which indicates the employment rate, indicating economic conditions; and wages, both real gross wages (GW_R) and real net wages (NW_R), which could impact health behaviours and access to resources.

Table 6.

Road Safety and Health Indicators.

Table 6 illustrates the interconnectedness of public health, road safety, and employment conditions, indicating that higher wages and employment rates often correlate with enhanced health outcomes and better access to resources. Additionally, the data suggest that older vehicles contribute to pollution and road safety risks, potentially affecting tourists’ perceptions of safety, especially for domestic cycling tourism.

A list of all the variables included in the modelling is included in Appendix A, where the dependent variable is cycling tourism, which is defined in Equation (1).

3.2. Methodology

This study employed factor analysis and VAR to assess Slovenia’s environmental and socioeconomic impacts of domestic cycling tourism. Factor analyses using the PCA extraction method identified key underlying dimensions from the dataset, revealing patterns among related variables and reducing data complexity. This approach was beneficial for identifying clusters of associated variables, such as those linked to pollution, tourism demand, or economic factors. First, data normalisation ensures comparability across variables, so data were normalised. This step standardised variables with different scales (e.g., CO2 emissions, GDP, and temperature). Second, factor extraction using principal factor analysis (PCA) was applied to extract factors, with eigenvalues greater than one retained for interpretation. This process revealed latent factors related to tourism demand, environmental conditions, and motorisation.

VAR was used to explore dynamic relationships among the variables, mainly focusing on how changes in one variable (e.g., tourist arrivals) impact other variables over time. VAR allows us to capture the interdependence of variables without presuming a specific causal direction, making it suitable for analysing complex systems where tourism, environment, and socioeconomic factors interact.

4. Results

This section presents this study’s results of factor analyses using the PCA extraction method and VAR on domestic cycling tourism demand, double pollution, and greenhushing.

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

The descriptive analysis is presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Descriptive Statistics.

The descriptive statistics provide key insights into the variables influencing cycling tourism and related environmental and socio-economic factors in Slovenia. The share of households with bicycles (BIK_SH_HOU) averaged 83.94 (SD = 11.08), indicating moderate variation in bicycle ownership. Bicycle expenditures (BIK_euro) were relatively high, with a mean of 142.09 and considerable variability (SD = 45.46), reflecting diverse consumer spending patterns.

Motorisation-related metrics, such as the motorisation rate (CAR_1000inhab) with a mean of 103.17 (SD = 3.48), highlighted a consistent reliance on cars. In contrast, the average car age (CAR_OLD) was 115.26 years (SD = 8.40), indicating an ageing vehicle fleet. Environmental indicators for CO2 emissions by residents (CO2(Gg)_Residents) and non-residents (CO2(Gg)_non-residents) showed means of 90.94 (SD = 4.92) and 130.64 (SD = 38.16), respectively, suggesting that non-resident tourism contributes significantly to emissions.

Tourism metrics revealed variability in tourist arrivals (TA_SI), with a mean of 135.42 (SD = 36.64). Domestic arrivals (TA_DOM) were lower, averaging 114.63 (SD = 22.25). Public transport usage, such as city bus rides (TRAVEL_CITY, mean = 110.45, SD = 29.99), showed higher variability than train travel (TRAVEL_TRAIN, mean = 87.75, SD = 14.37). Overall, these results emphasise the interplay of transportation, environmental impacts, and tourism in Slovenia.

4.2. Results of Factor Analysis

Table 8 presents the results of factor analyses using the PCA extraction method. The PCA findings offer valuable insights into the interplay between cycling tourism, environmental sustainability, and socio-economic factors in Slovenia.

Table 8.

Factor Analysis; Extraction Method: PCA.

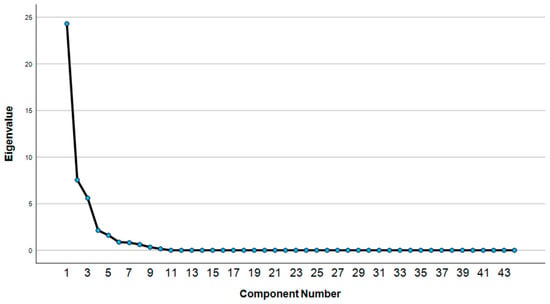

All variables had extraction values above 0.5, except rain, which indicated that all variables could be included in this research. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure was 0.842, indicating sample adequacy for PCA. Bartlett’s test for sphericity was significant (p < 0.001), suggesting correlations among variables suitable for the analysis. Of the three extracted factors (Figure 1), Factor 1 accounted for 55.24% of the variance, Factor 2 for 17.15%, and Factor 3 for 12.73%, resulting in a cumulative explanation of 85.13%.

Figure 1.

Scree Plot.

Additionally, high communalities (>0.9) were found in GDP (0.983), urban population (0.979), and bicycle imports (0.946), whereas low communalities (<0.5) were reflected in snow days (0.166) and temperature (0.484), suggesting these variables contribute less to the overarching patterns.

Based on Table 8 of factor loadings and Figure 1, three factors were identified, each representing a distinct latent construct. The factors were defined and named based on the patterns of variable loadings within each element.

Factor 1: Socio-Economic and Urbanisation Dynamics has key variables with high loadings: BIK_euro (0.991), BIK_import (0.917), GDP_R (0.987), CAR_1000inhab (0.984), URB (0.937), UNI_1 (0.964), UNI_2 (0.932), and UNI_3 (0.936). This factor captures the economic and urban characteristics influencing cycling tourism. High GDP, urbanisation levels, and strong investment in bicycles (both financial and through imports) align with increased tourism demand. The loadings of education-related variables (UNI_1, UNI_2, and UNI_3) suggest that higher educational attainment correlates with urban development and eco-tourism behaviours. The latent variable was the Economic and Urban Growth Factor.

Factor 2: Environmental and Travel Behaviour Impacts has key variables with high loadings: CO2(Gg)_non-residents (0.863), TRAVEL_CITY (0.936), TA_SI (0.820), TRAVEL (0.804), and BIK_TOUR (0.702). This factor emphasises the environmental and behavioural dimensions of tourism. The high loadings of non-resident CO2 emissions and urban public travel suggest that external tourist activities and transportation choices play a critical role in emissions. High travel activity (TRAVEL, TRAVEL_CITY) signifies reliance on public and urban transport for cycling tourism, accompanied by domestic cycling tourism. The latent variable’s name was the Tourism (also domestic cycling tourism)-Driven Environmental Factor.

Factor 3: Climatic and Sustainability Challenges has key variables with high loadings: CO2(Gg)_Residents (0.937), CO2_tones (0.929), and SUN_DAY (0.710). So, the interpretation of this factor is the interaction between climatic conditions and sustainability challenges. Resident CO2 and total emissions dominate this factor, highlighting local environmental impacts. Sunshine duration (SUN_DAY) further linked climate as a factor influencing outdoor activities, including cycling. The name of the latent variable was the Climatic Sustainability Factor.

These three factors provide a nuanced perspective on the dimensions influencing cycling tourism in Slovenia. The Economic and Urban Growth Factor underscores the socio-economic foundations of tourism. The Tourism-Driven Environmental Factor emphasises the impact of external tourists and their travel behaviours on environmental conditions. Finally, the Climatic Sustainability Factor addresses the local climatic and sustainability challenges that intersect with tourism dynamics. Collectively, these factors present a comprehensive framework for understanding the complexities of cycling tourism and its broader implications for sustainable development.

Subsequently, the VAR model gave us the next step for the results. All latent variables were normally distributed by the Jarque Berra test, where the domestic cycling tourism variable was marginally normal with a . The VAR modelling results were:

where p values are in parenthesis.

where presents white noise and the Durbin–Watson statistic is 1.86.

The results of the VAR model indicate the dynamic relationship of cycling tourism (BIK_TOUR) with its lagged values and other factors (F) over time. The equations reflect how the current value of BIK_TOUR is influenced by its past values and other explanatory variables. Equation (2) shows that BIK_TOUR is negatively influenced by a constant term (−14.10) but positively impacted by its lagged value (BIK_TOUR_t-1) with a coefficient of 0.07 (p = 0.05) and another factor (F_1) with a coefficient of 2.26 (p = 0.06). The statistical significance (p-values close to 0.05) suggests moderate evidence for the relationship. Equation (3) incorporates a similar structure but includes F_2, where the constant is slightly higher (−17.88). The coefficients of BIK_TOUR_t-1 (1.07, p = 0.05) and F_2 (2.26, p = 0.06) show similar positive impacts. Equation (4) expands the analysis by including F_3. The Durbin–Watson statistic (1.86) indicates no significant autocorrelation, supporting the model’s reliability. The VAR results reveal that all factors influence domestic cycling tourism significantly.

5. Discussion

The findings from the PCA and VAR analyses support Hypothesis 1. The first principal component (F1), representing the Economic and Urban Growth Factor, highlights the significant influence of socio-economic components such as real GDP (loading = 0.987) and urban population density (represented by URB, loading = 0.937) on domestic cycling tourism (BIK_TOUR). The VAR results further confirm this, with F1 having a positive and significant coefficient (2.26, p = 0.06) in Equation (2), indicating that economic growth and urbanisation are key drivers of cycling tourism [13].

The findings from the PCA and VAR analyses support Hypothesis 2. The second principal component (F2), representing the Tourism (also domestic cycling tourism)-Driven Environmental Factor, underscores the relationship between tourism activities, including domestic cycling tourism, and environmental impacts. Variables such as tourist arrivals (TA_SI, loading = 0.820) and CO2 emissions from non-residents (CO2_Gg_nonresidents, loading = 0.863) highlight that increased tourism drives higher emissions, mainly from transportation to cycling sites [47].

The third principal component (F3), representing the Climatic Sustainability Factor, also plays a critical role. It includes sunshine hours (SUN_DAY, loading = 0.710) and precipitation (PRECI, loading = −0.589), influencing the seasonality and attractiveness of cycling tourism. While favourable climatic conditions promote cycling tourism, they are indirectly linked to increased emissions through associated travel behaviours [42].

The VAR model confirms the influence of these factors, with F2 and F3 both significantly contributing to cycling tourism (BIK_TOUR) in Equations (3) and (4) (coefficient = 2.26, p = 0.06). These results support the concept of “double pollution”, where emissions from car travel to cycling destinations and cycling tourism activities combine, illustrating the need for integrated sustainable practices in Slovenia’s tourism sector.

The results of the factor analyses using the PCA extraction method and VAR modelling provide insights into the relationship between greenhushing practices and double pollution ethics in Slovenia’s tourism sector. The third principal component (F3), the Climatic Sustainability Factor, highlights the role of weather conditions, such as sunshine hours (SUN_DAY, loading = 0.710), in driving cycling tourism demand. However, it also reveals the environmental costs associated with emissions from associated travel behaviours. This is supported by the second principal factor (F2), the Tourism (also domestic cycling tourism)-Driven Environmental Factor, which emphasises the positive association between tourist arrivals (TA_SI, loading = 0.820, BIK_TOUR = −0.702) and non-resident CO2 emissions (CO2_Gg_nonresidents, loading = 0.863).

VAR results indicate that both F2 and F3 significantly influence cycling tourism, with coefficients of 2.26 (p = 0.06) in Equations (3) and (4). The results confirm the dual impact of tourism: while promoting sustainability narratives, it concurrently generates emissions, mainly from car travel to cycling destinations. These findings suggest that greenhushing practices in Slovenia’s tourism sector might obscure the full environmental impact of cycling tourism, as the reported eco-friendly benefits do not account for emissions generated by ancillary travel.

The authors of [7] highlighted that greenhushing often occurs in industries where eco-friendly branding is central to consumer appeal, as disclosing total environmental costs could harm a brand’s reputation.

Greenhushing in tourism challenges transparent environmental reporting and may prevent policymakers from understanding the full impact of tourism activities [8]. Without accurate data on emissions from ancillary travel, decisions on tourism development and sustainability policies will likely be based on incomplete information, leading to ineffective strategies [48]. For Slovenia, enhancing transparency in environmental reporting would allow for a more comprehensive understanding of the tourism sector’s actual environmental impact, supporting evidence-based policies aligned with sustainability goals.

Addressing greenhushing requires stricter reporting guidelines for tourism operators, particularly around emissions generated by travel behaviours [49]. In the case of domestic cycling tourism, operators should provide clear information on all emissions associated with tourism, including those indirectly generated through car travel. This transparency would foster accountability, enabling stakeholders to assess the actual environmental costs of domestic cycling tourism and make informed decisions about its growth and sustainability. Based on the findings, several policy recommendations can be proposed to facilitate the sustainable development of domestic cycling tourism in Slovenia. These policies specifically address the issues of double pollution, greenhushing, and accessibility, advocating for a balanced approach that amplifies the benefits of domestic cycling tourism while mitigating its associated environmental costs.

Firstly, policymakers should improve public transportation systems that connect urban centres with prominent cycling destinations to diminish car dependency. By improving rail and bus connectivity and providing dedicated bike storage on public transport, policymakers can encourage tourists to opt for more sustainable travel alternatives. Additionally, the implementation of shuttle services or park-and-ride facilities at major cycling hubs has the potential to reduce emissions significantly, thus addressing double pollution.

Secondly, tourism operators should be encouraged to expand local bike rental services to mitigate the environmental impact stemming from the transportation of bicycles via car, particularly in rural and picturesque areas. This initiative would decrease tourists’ need to transport bicycles, limiting car travel emissions. Investment in secure bike storage and maintenance facilities at key destinations would further bolster this initiative, enhancing the convenience and sustainability of domestic cycling tourism.

Thirdly, establishing a regulatory framework mandating transparent environmental reporting for tourism operators is vital for addressing the challenge of greenhushing. By requiring operators to disclose all emissions associated with tourism activities—encompassing indirect emissions from car travel—Slovenia can foster greater accountability and provide stakeholders with a comprehensive understanding of the tourism sector’s environmental footprint. Such transparency would empower policymakers to make informed, data-driven decisions, supporting the nation’s long-term sustainability objectives.

Fourthly, Slovenia could significantly benefit from establishing emission reduction targets tailored to the tourism sector. These targets would encourage operators to adopt eco-friendly practices and ultimately reduce emissions across the industry. By driving investment in sustainable tourism initiatives, these targets would incentivise the utilisation of renewable energy sources, carbon offset programs, and the local sourcing of materials and services.

Finally, public awareness campaigns promoting the environmental merits of public transportation and local bike rental services could play a pivotal role in further reducing emissions. By educating tourists about sustainable travel alternatives, Slovenia’s tourism industry could facilitate behavioural modifications that align with sustainability objectives and encourage eco-conscious practices among the travelling public [50,51].

Overall, this study isolates and defines the theoretical conceptualisation of “double pollution” by revealing how associated car travel undermines the perceived eco-friendliness of cycling tourism. Additionally, it advances the concept of “greenhushing” by uncovering systematic underreporting of tourism-related emissions, highlighting its ethical and managerial implications. These contributions enrich the theoretical discourse on sustainable tourism practices, urging future research to prioritise transparency, integrate multi-dimensional analyses, and address the indirect environmental impacts of tourism activities. This work establishes a critical foundation and raises awareness for developing policies that align tourism practices with broader sustainability goals.

6. Conclusions

This research sheds light on domestic cycling tourism’s sustainability complexities, challenging the assumption that it is inherently eco-friendly. While cycling tourism offers economic and health benefits, its environmental costs, particularly those associated with ancillary travel behaviours, require critical reassessment. By addressing greenhushing practices and implementing holistic sustainability measures, Slovenia’s tourism sector can align with broader environmental objectives and enhance its reputation as a leader in sustainable travel.

The results support Hypothesis 1. Socioeconomic and environmental factors, including real GDP, urban population density, and climate conditions, significantly affect the demand for domestic cycling tourism in Slovenia. The findings also confirm Hypothesis 2. Cycling-based tourism in Slovenia significantly contributes to double pollution due to the combined outputs from car travel to cycling sites and activities.

Regarding the research question (i.e., based on the factor analysis and VAR modelling results, can we confirm that greenhushing practices in Slovenia’s tourism sector lead to double pollution ethics?), this study identifies evidence of greenhushing practices in Slovenia’s tourism sector. The results confirm greenhushing practices through the Tourism (also domestic cycling tourism)-Driven Environmental Factor (F2), highlighting significant emissions from ancillary travel behaviours, and VAR modelling, which shows positive associations between tourist arrivals and CO2 emissions. This selective omission of environmental costs distorts cycling tourism’s sustainability narrative, complicating policymaking and fostering double pollution ethics.

6.1. Limitations and Delimitations

This study has several limitations. First, it relies on secondary data from 2011 to 2021, which may not capture recent trends or changes in tourism behaviours. The data’s annual frequency limits the granularity of analysis, potentially obscuring short-term fluctuations in tourism demand and environmental impacts. Additionally, this study focuses on Slovenia, limiting the generalisability of findings to other regions with different tourism infrastructures and socioeconomic conditions. This research also assumes linear relationships in the VAR modelling, which may oversimplify complex interactions between variables. Furthermore, the analysis does not account for qualitative factors, such as tourists’ perceptions of sustainability or the role of cultural attitudes in shaping travel behaviours.

This study deliberately focuses on domestic cycling tourism in Slovenia, excluding international and other forms of domestic tourism. This focus allows for a detailed analysis of cycling tourism’s specific impacts but limits broader applicability. This research also emphasises quantitative methods, such as factor analysis using PCA method extraction and VAR, while qualitative insights are beyond its scope. By narrowing its focus to quantitative data, this study aims to provide objective and replicable findings, but it acknowledges the value of integrating qualitative perspectives in future research.

6.2. Implications

This research represents a pioneering investigation into double pollution and greenhushing within domestic cycling tourism. It incorporates various variables derived from secondary data, making its approach more evidence-based (using appropriate methodology all shocks are inserted in the studied time frame) than previous studies reliant on subjective interviews and surveys. Furthermore, the data encompass all relevant information from the study period.

The findings underscore the importance of integrating sustainable practices into tourism policies. Policymakers should prioritise investments in public transportation and local bike rental systems to reduce reliance on cars for accessing cycling destinations. Additionally, tourism operators should adopt transparent environmental reporting standards to build trust and support data-driven policy decisions. Implementing eco-friendly infrastructure, such as bike-sharing programs and secure bike storage, can promote sustainable travel behaviours.

This research contributes to the literature on sustainable tourism by providing a nuanced understanding of the indirect environmental impacts of cycling tourism. It introduces the concept of “double pollution” and its interplay with greenhushing, expanding the theoretical framework for evaluating the sustainability of tourism practices. This study also emphasises the need for holistic approaches that account for direct and indirect environmental costs.

Transparent environmental reporting should be mandated for tourism operators, ensuring comprehensive emissions disclosure from all tourism-related activities. Emission reduction targets tailored to the tourism sector could drive sustainable practices, encouraging the adoption of renewable energy and carbon offset programs. Public awareness campaigns highlighting sustainable travel alternatives can foster behavioural changes among tourists.

6.3. Future Research Directions

Future studies should address the limitations identified in this research. Collecting more granular data on tourists’ travel behaviours, including daily transportation choices and seasonal patterns, would provide deeper insights into the dynamics of cycling tourism. Expanding the scope to include international tourists and comparative analyses across regions with diverse infrastructures could enhance the generalizability of findings.

Qualitative research exploring tourists’ perceptions of sustainability and motivations for cycling tourism would complement quantitative analyses, offering a more comprehensive understanding of travel behaviours. Additionally, longitudinal studies examining the long-term impacts of policy interventions, such as investments in public transportation and bike-sharing systems, would provide valuable evidence for policymakers. Exploring the intersection of digital technologies and sustainable tourism could also be a fruitful avenue for research. For instance, studying the role of mobile apps in promoting eco-friendly travel behaviours or analysing the effectiveness of virtual tourism campaigns in reducing physical travel could offer innovative solutions to sustainability challenges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, S.G. and Š.B.; methodology, S.G.; software, S.G.; validation, Š.B.; formal analysis, S.G.; investigation, S.G.; resources, S.G.; data curation, S.G.; writing—original draft preparation, S.G. and V.Š.; writing—review and editing, Š.B. and V.Š.; visualisation, S.G.; supervision, Š.B.; project administration, S.G.; funding acquisition, S.G. and V.Š. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency, the Ministry of the Environment, Climate and Energy, and the Ministry of Cohesion and Regional Development, grant number CRP2023 V5-2331.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are secondary data and publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Names of all included variables in this research:

| BIK_SH_HOU | Share of households with bicycles. |

| BIK_euro | Expenditures on bicycles in euros. |

| BIK_import | Number of bicycles imported. |

| LEA_days | Average number of days lost due to illness. |

| CO2_newCAR | CO2 emissions from new passenger cars. |

| GW_R | Real gross wages. |

| NW_R | Real net wages. |

| SBI_R | Slovenian stock index in real terms. |

| CPI_2017 | Consumer Price Index with the base year 2017. |

| CO2(Gg)_Residents | CO2 emissions from residents in gigagrams. |

| CO2(Gg)_nonresidents | CO2 emissions from non-residents in gigagrams. |

| CO2_tones | Total CO2 emissions in tons. |

| CO | Carbon monoxide emissions. |

| INV_ENV_SI_euro | Investments in environmental protection in euros. |

| INV_ENV_SI_state_euro | State investments in environmental protection in euros. |

| CAR_1000inhab | Motorisation rate (number of cars per 1000 inhabitants). |

| DEA_10000_inhab | Road deaths per 10,000 inhabitants. |

| N20(Mg) | Nitrous oxide emissions in megagrams. |

| CH4_Mg | Methane emissions in megagrams. |

| CH4_tones | Methane emissions in tons. |

| N2O_tones | Nitrous oxide emissions in tons. |

| INV_ENV_BDP% | Investments in environmental protection as a percentage of GDP. |

| CAR_OLD | Average age of cars in years. |

| CAR_1000INHAB_LJ | Motorisation rate in Ljubljana (number of cars per 1000 inhabitants). |

| CAR_1000INHAB_NM | Motorisation rate in Novo Mesto (number of cars per 1000 inhabitants). |

| URB | Urban population. |

| GDP_R | Real Gross Domestic Product. |

| UPRSCH | Population without primary school education. |

| PRSCH | Population with primary school education. |

| SSCH | Population with secondary school education. |

| UNI_1 | First-cycle university graduates. |

| UNI_2 | Second-cycle university graduates. |

| UNI_3 | Third-cycle university graduates. |

| T | Average annual temperature. |

| PRECI | Annual precipitation in millimetres. |

| SUN_DAY | Number of sunshine hours annually. |

| SNOW_DAYS | Number of snowfall days annually. |

| TRAVEL | Total bus rides. |

| TRAVEL_CITY | City-specific bus rides. |

| TRAVEL_TRAIN | Train rides. |

| TA_SI | Tourist arrivals in Slovenia. |

| EMPLOY_SI | Employment rate in Slovenia. |

| TA_DOM | Domestic tourist arrivals. |

| BIK_TOUR | Domestic bicycle tourism. |

References

- Poljičak, A.M.; Šego, D.; Periša, T. Analysis of cycling tourism: Case-study Croatia. Int. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. 2021, 11, 454–464. [Google Scholar]

- Handy, S.; Van Wee, B.; Kroesen, M. Promoting cycling for transport: Research needs and challenges. Transp. Rev. 2014, 34, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lőrincz, K.; Banász, Z.; Csapó, J. Customer involvement in sustainable tourism planning at Lake Balaton, Hungary—Analysis of the consumer preferences of the active cycling tourists. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttry, C.J. Allerton Park Climate Action Plan: Transportation; MUP Capstone: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rico, A.; Martínez-Blanco, J.; Montlleó, M.; Rodríguez, G.; Tavares, N.; Arias, A.; Oliver-Solà, J. Carbon footprint of tourism in Barcelona. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. Sustainable tourism development: A critique. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; Elgammal, I.; Lamond, I. Greenhushing: The deliberate under communicating of sustainability practices by tourism businesses. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1007–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuti, D.; Pizzetti, M.; Dolnicar, S. When sustainability backfires: A review on the unintended negative side-effects of product and service sustainability on consumer behavior. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 1933–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talpur, S.; Nadeem, M.; Roberts, H. Corporate social responsibility decoupling: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. J. Appl. Account. Res. 2024, 25, 878–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciascai, O.R.; Dezsi, Ș.; Rus, K.A. Cycling tourism: A literature review to assess implications, multiple impacts, vulnerabilities, and future perspectives. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, R.; Goodman, A.; Aldred, R.; Nakamura, R.; Tatah, L.; Garcia, L.M.T.; Woodcock, J. Cycling behaviour in 17 countries across 6 continents: Levels of cycling, who cycles, for what purpose, and how far? Transp. Rev. 2022, 42, 58–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumsdon, L. Transport and tourism: Cycle tourism–a model for sustainable development? J. Sustain. Tour. 2000, 8, 361–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šobot, A.; Gričar, S.; Šugar, V.; Bojnec, Š. Sustainable Cycling: Boosting Commuting and Tourism Opportunities in Istria. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harford, J.D.; Karp, G. The effects and efficiencies of different pollution standards. East. Econ. J. 1983, 9, 79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Haigh, R.; Liszka, S. Greenwashing and greenhushing: Risks and opportunities from the gap between brand sustainability perceptions and performance. J. Brand Strategy 2024, 13, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seele, P.; Gatti, L. Greenwashing revisited: In search of a typology and accusation-based definition incorporating legitimacy strategies. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, L. Greenhushing: A Systematic Literature Review. In MIC 2024: Next Generation Challenges: Innovation, Regeneration and Inclusion, Proceedings of the Joint International Conference, Trento, Italy, 5–8 June 2024; University of Primorska Press: Koper, Slovenia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Wang, M.; Ragavan, N.A.; Poulain, J.P. Tourism Governance Towards Sustainability: A Review and a Metagovernance Model. The Elgar Companion to Tourism and the Sustainable Development Goals; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2024; pp. 260–283. [Google Scholar]

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. Sustainable tourism: An evolving global approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 1993, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Sarkar, P. A Study on the Impact of Environmental Awareness on the Economic and Socio-Cultural Dimensions of Sustainable Tourism. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Rev. 2024, 3, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Walking and Cycling: Latest Evidence to Support Policy-Making and Practice. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289057882 (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Can, A.; L’hostis, A.; Aumond, P.; Botteldooren, D.; Coelho, M.C.; Guarnaccia, C.; Kang, J. The future of urban sound environments: Impacting mobility trends and insights for noise assessment and mitigation. Appl. Acoust. 2020, 170, 107518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, M. Embodiment in active sport tourism: An autophenomenography of the tour de france alpine “cols”. Sociol. Sport J. 2020, 38, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, H.; Pouw, W.; Fuchs, S. On the Relation Between Leg Motion Rate and Speech Tempo During Submaximal Cycling Exercise. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2024, 67, 3931–3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fruhen, L.S.; Benetti, P.; Kanse, L.; Rossen, I. Why not pedal for the planet? The role of perceived norms for driver aggression as a deterrent to cycling. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Balas, M.; Mayer, M.; Sun, Y.Y. A review of tourism and climate change mitigation: The scales, scopes, stakeholders and strategies of carbon management. Tour. Manag. 2023, 95, 104681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streimikiene, D.; Svagzdiene, B.; Jasinskas, E.; Simanavicius, A. Sustainable tourism development and competitiveness: The systematic literature review. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Ramakrishna, S.; Hall, C.M.; Esfandiar, K.; Seyfi, S. A systematic scoping review of sustainable tourism indicators in relation to the sustainable development goals. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 1497–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Meng, B.; Kim, W. Emerging bicycle tourism and the theory of planned behavior. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 292–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrkajic, V.; Vukelic, D.; Mihajlov, A. Reduction of CO2 emission and non-environmental co-benefits of bicycle infrastructure provision: The case of the University of Novi Sad, Serbia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 49, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nangini, C.; Peregon, A.; Ciais, P.; Weddige, U.; Vogel, F.; Wang, J.; Creutzig, F. A global dataset of CO2 emissions and ancillary data related to emissions for 343 cities. Sci. Data 2019, 6, 180280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minarta, R.R.; Ko, J. What are the stimulants on transportation carbon dioxide emissions?: A nation-level analysis. Energy 2024, 296, 131179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.H. Pedaling beyond ratings: A data-driven quest to Unravel the determinants of guided bicycle-tour satisfaction. Tour. Manag. 2024, 103, 104906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D. Tourism in the polycrisis: A Horizon 2050 paper. Tour. Rev. 2024; ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Gössling, S. Extending the theoretical grounding of mobilities research: Transport psychology perspectives. Mobilities 2023, 18, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniele, C.; Elena, M.; Evangelia, P. Assessing the role of public transportation to foster city bike tourism. The case of Italy. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2023, 12, 101015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejón-Guardia, F.; Rialp-Criado, J.; García-Sastre, M.A. The role of motivations and satisfaction in repeat participation in cycling tourism events. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2023, 43, 100664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derman, E.; Keles, H. A Conceptual Evaluation of Cycling Tourism in the Context of Sustainable Tourism. J. Tour. Gastron. Stud. 2023, 11, 1382–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilco, C.; Leon, L.; Chammy, L.; Derek, P. Rest station’s value-added amenities for biking tourism and leisure: Perspectives of seasoned bicyclists and infrequent bicyclists. Transp. Policy 2024, 149, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; Lynes, J. Corporate social responsibility in tourism and hospitality. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1027–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwashing, Greenhushing and Greenwishing: Don’t Fall Victim to These ESG Reporting Traps. Available online: https://www.esgtoday.com/guest-post-greenwashing-greenhushing-and-greenwishing-dont-fall-victim-to-these-esg-reporting-traps/ (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Tao, Z. Do not walk into darkness in greenhushing: A cross-cultural study on why Chinese and South Korean corporations engage in greenhushing behavior. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2024, 7, e401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swestiana, A.; Kusworo, H.A.; Fandeli, C. Greenwashing or greenhushing? A Quasi-experiment to correlate green behaviour and tourist’s level of trust toward communication strategies in volunteer tourism’s website. J. Kepariwisataan Destin. Hosp. Dan Perjalanan 2022, 6, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, C. Misleading markets: Consumer protection in the age of climate washing. West Va. Law Rev. 2023, 126, 367. [Google Scholar]

- Casselbrant, A.; Wibner, F. Hållbarhetsinriktad varumärkesutveckling och strategiska anpassningar: Energibolags relationer och strategier: En kvalitativ studie om hållbarhetskommunikation, CSRD och dess påverkan på varumärkesimage och intressentrelationer, 2024. Tour. Gastron. Stud. 2023, 11, 1382–1394. [Google Scholar]

- Carra, M.; Pavesi, F.C.; Barabino, B. Sustainable cycle-tourism for society: Integrating multi-criteria decision-making and land use approaches for route selection. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 99, 104905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, V.; Marasco, A.; Apicerni, V. Sustainability communication of tourism cities: A text mining approach. Cities 2023, 143, 104590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, W.; Alarcón, S. How can rural tourism be sustainable? A systematic review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; McCabe, S. Sustainability and marketing in tourism: Its contexts, paradoxes, approaches, challenges and potential. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 869–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poveda-Pareja, E.; Marco-Lajara, B.; Úbeda-García, M.; Manresa-Marhuenda, E. The paradox between means and end: Workforce nationality diversity and a strategic CSR approach to avoid greenwashing in tourism accommodations. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, R.P. How Greenwashing Affects Firm Risk: An International Perspective. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2024, 17, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).