Abstract

The 2023 Global Sustainable Development Report identified sustainable cities and communities as a critical area for in-depth review, emphasizing the need for systematically examining theoretical knowledge and guidance on the direction of development This article reviews the relevant literature from the Web of Science core database over the past decade and introduces Professor Verganti’s theoretical perspective of “design-driven innovation” to summarize technological research, user needs/demand, and design, providing a new theoretical dimension for the research on sustainable communities. To this end, this study employs three econometric tools—VOSviewer, RStudio Bibliometric, and CiteSpace—to analyze status and trends visually. The findings reveal that the design level has garnered the most research results, with the USA as the primary contributor and China as the country with the most development potential. Moreover, the most prominent research topics within the three perspectives are microbial communities, sustainable development goals, and ecosystem services, with recent research highlights focusing on artificial intelligence, social innovation, and tourism. In conclusion, this article proposes a strategic framework for the future development of sustainable communities, encompassing consolidation of technical foundations, clarification of demand orientation, and updating design specifications and theories to provide diverse solutions.

1. Introduction

Sustainable communities have increasingly attracted academic attention in recent years, focusing on the achievement of social, economic, and environmental balance through comprehensive planning and development strategies. Although there is no official definition, a consensus has emerged regarding their essential characteristics: promoting sustainable lifestyles through effective planning, construction, and transformation. The 11th of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, “Sustainable Cities and Communities” (SDG 11), does not distinguish between cities and communities [1]. The target statement, “Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable”, underscores the importance of both cities and communities in realizing this goal, which, if accomplished, can also serve as a foundation for achieving other sustainable development objectives [2].

With a solid policy foundation and robust organizational support, the significance of sustainable community initiatives has increased, leading to the implementation of related projects worldwide. In Toronto, the Sustainable Neighborhood Improvement Action Plan (SNAP) focuses on energy conservation, expanding urban forests, water conservation, stormwater management, and local food production to foster more resilient communities. The Rockefeller Foundation in the United States has launched a global initiative called the 100 Resilient Cities Network (100RC) to assist cities in addressing their challenges and enhancing their resilience [3]. The Shanghai Municipal Bureau of Planning and Natural Resources issued the “Guidelines for the Planning of the 15-Min Community Life Circle in Shanghai” in August 2016 [4]. This concept of a 15-min community living circle highlights walkability and the rationality of the layout of public service facilities, including transportation systems, in urban planning, as well as their relationship with the structural layout of residential zones. Overall, following the completion of the large-scale rapid urbanization phase, a critical issue for future development will be improving urban sustainability. Summarizing and drawing lessons from various sustainable community studies has also become a priority.

The development of sustainable communities necessitates the integration of knowledge and methodologies from a diverse array of disciplines, including environmental science, social science, and economics. However, current research often fails to fully leverage these interdisciplinary resources, resulting in limitations to both the depth and breadth of inquiry at theoretical and practical levels. First, the existing research tends to focus on technological advances and transformational outcomes [5], a bias that leads research to overlook the social and economic dimensions of community sustainability. Additionally, there has been a failure to implement some well-established technologies in underdeveloped regions [6]. Second, community members are the main stakeholders in a community, and their needs go far beyond technical and material dimensions to include deeper needs such as emotional, cultural, and social interactions [7]. However, these needs are often marginalized in research, resulting in findings that may not adequately respond to the real and diverse needs of communities. Finally, exploration of modes of innovation appears to be inadequate in the existing research. Despite the gradual emphasis on market-oriented green innovation, most existing research on sustainable communities investigates sustainable technologies or specific community cases but lacks organization and summarization of existing research content and exploration of future research trends [8].

Innovation is closely linked to development trends. Design innovation not only integrates technological and market factors but also permeates community culture and daily life, fostering deeper innovation and transformation. Verganti [9] suggests that new development can be promoted through design innovation that addresses deep-seated emotional and socio-cultural needs. Current trends in sustainable community research reveal that traditional sustainable community innovations stem from two primary approaches. The first is disruptive innovation, which leverages technological breakthroughs such as the internet of things (IoT) and artificial intelligence (AI). The second approach involves incremental innovation and various micro-innovations based on market analysis. For a considerable time, these two modes of innovation have dominated community innovation. However, the task of sustainable community innovation at this stage necessitates a more nuanced understanding to clarify overarching goals. To address this research gap, this paper introduces a third approach to driving innovation: comprehensive innovation driven by design innovation that is oriented toward deep emotional and socio-cultural needs, as illustrated in Figure 1. This type of design-driven sustainable community offers significant advantages, including user-centered innovation, meaning making, and theme creation.

Figure 1.

Design-driven innovation model.

In summary, this paper explores sustainable communities through the lenses of technology, needs, and design in both past and future development processes. It employs visual knowledge mapping tools to identify comprehensive and effective strategies for achieving sustainable community development. Utilizing CiteSpace, VOSviewer, and Bibliometrix R as analytical tools, this study aimed to (a) expand the existing literature on sustainable communities and (b) gain insights into publishing trends, literature collaborations, research progress and impact, research hotspots, and emerging trends related to sustainable communities from the perspectives of technology, needs/requirements, and design.

2. Research Methodology

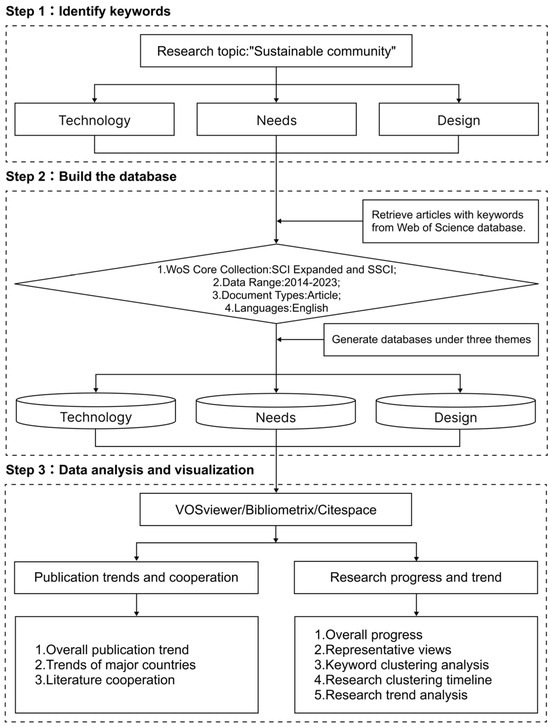

2.1. Research Framework

As illustrated in Figure 2, the framework comprised several stages: data collection, preprocessing and cleaning, bibliometric analysis, cross-validation and comparison, interpretation and synthesis, reporting, and dissemination. First, the research directions for sustainable community perspectives were identified as follows: technology, needs/demand, and design. Second, searches were conducted on the Web of Science (WoS) to obtain databases of papers related to these three topics. Finally, the data were imported into VOSviewer, Bibliometrix, and CiteSpace for visual analysis to derive current research findings regarding sustainable communities from the three aforementioned perspectives.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of data collection, data analysis, and data visualization.

2.2. Research Methods

The bibliometric method employed in this study has been utilized across various fields, with relevant measurement software continuously updated through iterations to enhance document analysis capabilities and visual mapping quality. In this research, three measurement tools—VOSviewer, RStudio Bibliometrix, and CiteSpace—were used to cross-check the gaps in each tool and ultimately obtain the most accurate research data regarding perspectives on sustainable communities. VOSviewer is a program developed for constructing and viewing bibliometric maps [10]. It can display maps in various ways, such as network visualization, overlay visualization, and density visualization. The Bibliometrix R package provides a set of tools for quantitative research in bibliometrics and scientometrics and is written in the R language, an open-source environment and ecosystem [11]. CiteSpace can perform visual network analysis on articles retrieved from a database in a specific field, enabling a clearer view of research progress and development trends in that field [12]. In this paper, VOSviewer (version 1.6.19.0) was utilized to create national cooperation network maps. The Bibliometrix R tool (accessed on 28 July 2023) was employed to generate various types of visual charts, to compare data, and to supplement findings from the other two measurement software programs. Additionally, CiteSpace (version 6.2.4.0) was used to investigate keyword clustering, keyword time zones, and emerging terms from three perspectives relating to sustainable communities.

2.3. Data Sources

In this study, we utilized the Web of Science (WoS) to establish an information base and employed advanced retrieval methods to analyze the literature sources in English from the WoS core collection, specifically, the Science Citation Index Expanded and the Social Sciences Citation Index. The search query for sustainable communities from the technology perspective was structured as follows: (TS = (sustainable community)) AND TS = (technology) and 2023 or 2022 or 2021 or 2020 or 2019 or 2018 or 2017 or 2016 or 2015 or 2014 (Publication Years) and Article (Document Types) and English (Languages). For the needs perspective, the search terms were as follows: ((((TS = (residents’ needs)) OR TS = (residents’ preferences)) OR TS = (user requirement)) OR TS = (people needs)) AND TS = (sustainable community) and 2023 or 2022 or 2021 or 2020 or 2019 or 2018 or 2017 or 2016 or 2015 or 2014 (Publication Years) and Article (Document Types) and English (Languages). For articles from the design perspective, the search formula was as follows: TS = (sustainable community design) and 2023 or 2022 or 2021 or 2020 or 2019 or 2018 or 2017 or 2016 or 2015 or 2014 (Publication Years) and Article (Document Types) and English (Languages). After screening, 2862 and 1686 articles were retained for the technology and needs perspectives, respectively, yielding a total of 4844 analyzable samples from the literature.

3. Publication Trends and Cooperation

3.1. Overall Publication Trend

The number of published papers on a topic serves as a key indicator of research activity and can help identify trends in the growth of sustainable community research as well as the evolution of research interests [13]. Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of papers on sustainable community topics in the Web of Science (WoS) core journals over the past decade (2014–2023), highlighting publishing trends from the perspectives of technology, needs/demand, and design. This field of research has experienced continuous growth, particularly between 2019 and 2021, with the number of articles peaking in 2022. Among the specific topics, the design perspective has been the most frequent, followed by technology, while the demand perspective has had the fewest publications. The gap between technology- and needs/demand-perspective papers widened after 2019. Introducing the calculation of the overlap rate of articles under the three perspectives facilitated assessment of whether the research content between the different perspectives is interrelated and whether scholars have tended to synthesize and analyze issues from multiple perspectives. In this study, all article data on sustainable communities from the three perspectives were introduced into CiteSpace, to identify the number of overlapping articles and calculate the overlap rate to reveal whether the research content has been consistent across perspectives. The overlap rate remained between 10% and 16%, indicating that scholars have typically analyzed a single perspective rather than considering multiple perspectives simultaneously.

Figure 3.

The annual distribution of the literature in the field of sustainable community from 2014–2023.

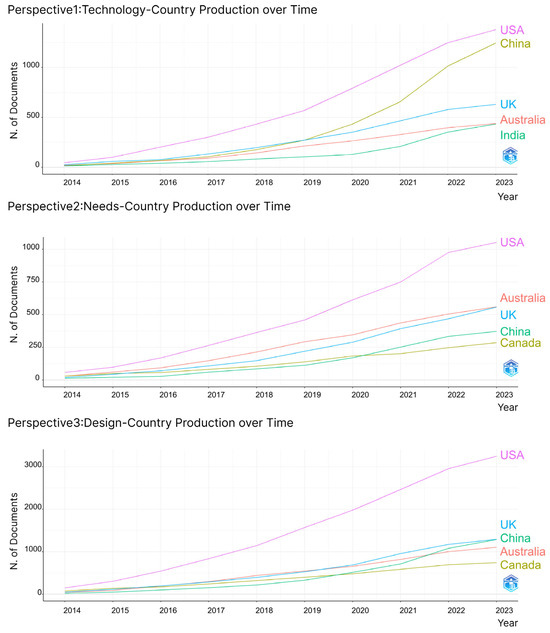

3.2. Trends of Major Countries

Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of the top five countries in terms of the numbers of publications related to the technology, needs/demand, and design perspectives. From the technology perspective, the leading countries are the USA, China, the UK, Australia, and India. The USA stands out with a substantial number of publications, exceeding 1000 in 2021. This indicates that the USA maintains a high level of research output in the field of sustainable community technology. China’s publication count has consistently increased, surpassing the UK in 2019, which suggests that China is placing significant emphasis on the technical aspects of sustainable communities, highlighting its potential for future research breakthroughs. From the needs perspective, the top five countries are the USA, Australia, the UK, China, and Canada, in that order. Notably, China surpassed Canada in the number of papers published in 2021. This ranking indicates that the USA places considerable emphasis on the demand aspect of sustainable communities, while the UK and China are gradually increasing their research investment in this area. From the design perspective, the leading countries are the USA, the UK, China, Australia, and Canada. The USA remains significantly ahead in terms of the number of publications, while the other four countries exhibit similar publication counts. China has experienced substantial growth in this area, with the number of papers published in 2023 nearing that of the second-ranked country.

Figure 4.

Country production of literature in the field of sustainable community from 2014–2023.

The top six countries in sustainable community research, considering technology needs, demand, and design perspectives, are the USA, China, the UK, Australia, India, and Canada. As illustrated in Figure 4, the USA has had a substantial collaborative influence, establishing it as the leading research country in sustainable communities. Furthermore, China’s increasing publication volume across all three levels signifies its growing focus on sustainable communities, positioning it as a country with considerable future research potential in these areas.

3.3. Cooperation in the Literature

To construct a geographic collaboration network analysis of the literature, we focused on the countries with which the various studies’ authors were affiliated, as this is the default setting in VOSviewer [14]. Figure 5 shows the collaborations among publishing countries, with the circle size representing a country’s influence and the density of connections indicating cooperation levels, simultaneously revealing dense connections between nations with regard to sustainable communities across the three perspectives, signifying strong international cooperation. The USA and China dominate technological collaborations, while Serbia, Mozambique, Malawi, and Nepal have a smaller influence, and Lithuania has not yet collaborated on work from this perspective. From the demand perspective, England and the USA have strong cooperation and influence, with most countries, except Turkey and Madagascar, closely cooperating. From the design perspective, the USA remains the central hub, and there is no clear hierarchical division of cooperation influence among countries, indicating that many countries have similar levels of academic cooperation.

Figure 5.

Cooperation among countries in publishing research articles from the perspectives of technology, needs and design.

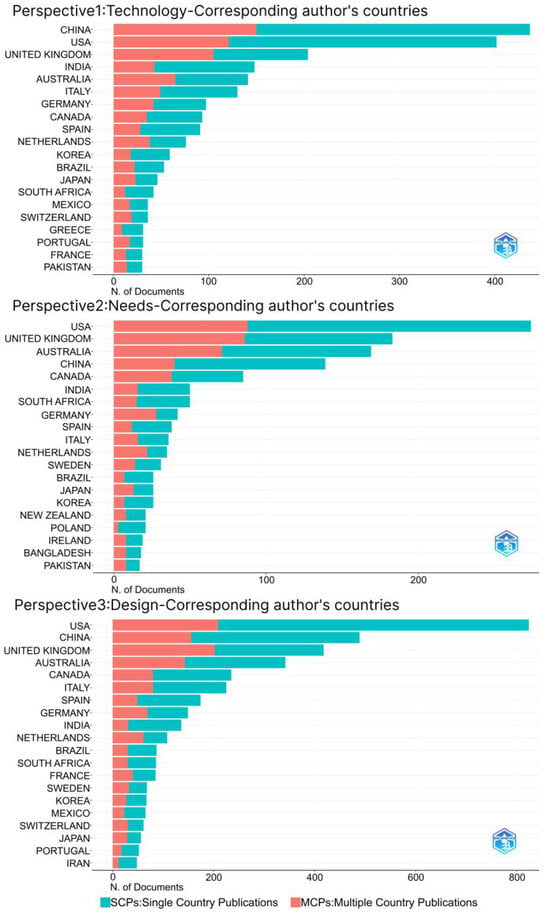

Urban regeneration is a crucial strategic choice for promoting urban development on a global scale [15]. Figure 6 illustrates author collaboration with regard to country of origin, with blue bars representing single-country publications (SCPs) and red bars indicating multiple-country publications (MCPs). Research on sustainable community topics primarily involves domestic scholars across various disciplines. In the realm of sustainable community technology, studies from China and the United States predominantly feature domestic authors, accounting for approximately two-thirds of the total publications. The United Kingdom exhibits a relatively balanced approach to domestic and international collaboration, thereby creating more opportunities for global research partnerships. Germany, the Netherlands, and Japan also demonstrate a high level of international cooperation. In the area of research into sustainable community demand, most countries’ research has primarily been produced by domestic authors, with the exception of the UK, Germany, and the Netherlands, which significantly emphasize multinational author collaboration, leading to more comprehensive perspectives. Overall, most countries continue to prioritize domestic author cooperation in sustainable community research, with the UK standing out as an exception, as it emphasizes international collaboration across all three research levels related to sustainable communities.

Figure 6.

Countries of the corresponding authors of research articles from the perspectives of technology, needs and design.

4. Research Progress and Trends

4.1. Overall Progress

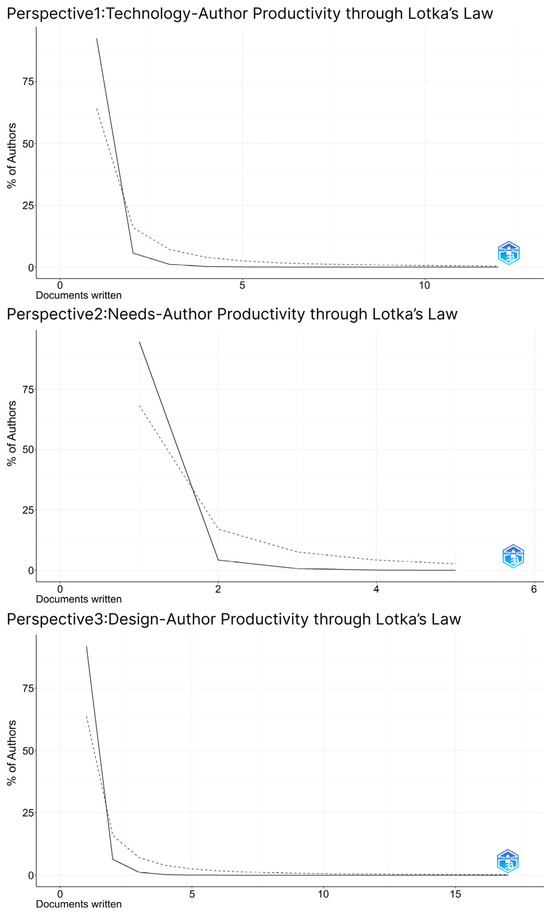

Lotka’s law is a power law that describes the frequency of scholarly publications [16]. In Figure 7, the horizontal axis represents the output of articles and the vertical axis represents the proportion of corresponding authors. Under the “technology perspective”, 12,684 scholars participated in research into sustainable communities, including 11,743 authors who contributed to a single article, accounting for 92.6% of the total. Thirty-eight scholars participated in 5 or more articles, including five scholars who contributed to 10 or more articles in the field. The results show that most scholars in the field of sustainable community technology are relatively new, but a few have published more in-depth research results. From the “needs/demand” perspective, 7681 scholars participated in the research, with 94.9% publishing one article and only one scholar publishing five or more. This suggests that research in this field is still in its infancy. From the “design” perspective, 21,527 scholars participated in the research, with 91.9% publishing one article. Fifty-one scholars published 5 or more articles, and one scholar contributed to 17 articles, indicating more in-depth research in this field. Overall, most of these scholars have engaged in sustainable community research to some extent, but the number of scholars deeply invested in research is relatively small, and the number of scholars involved in subsequent academic output is lower than expected.

Figure 7.

Lotka’s law graph from the perspectives of technology, needs and design.

4.2. Representative Views

The comprehensive analysis of all the retrieved literature directly reflected the research trends and progress related to sustainable communities. Additionally, to refine the key research topics concerning sustainable communities at the technology, needs/demand, and design levels from a more comprehensive and realistic perspective, we selected the 10 articles with the highest citation frequency from each level for analysis, as listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Studies related to affordable housing projects.

At the technological level, the direction of research into sustainable communities was focused on computer science and chemistry; however, in recent years, the research focus has gradually shifted to biochemistry and social sciences. Simultaneously, the content of research into sustainable communities at the technological level has been diverse, including the sharing economy [17], chain management [18], synthetic organic electrochemistry [19], and smart and connected communities [20].

In relation to sustainable communities, at the demand level, the primary research directions in the past 10 years have involved environmental sciences. The earliest study was by the research team of Stylidis and Dimitrios, who considered the demand preferences of community residents and tourists simultaneously in the context of sustainable community demand. They emphasized that community planners should address the impact of flexibility in tourism and measure residents’ needs [21]. In the context of demand, researchers into sustainable communities have launched discussions around demand for healthy aging [22], energy security [23], and sustainable food systems [24], among other research content.

To sum up, sustainable community construction must address Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, namely physiological needs, safety, social needs, esteem, and self-actualization. Regarding sustainable communities at the design level, most of the highly cited literature is from 2014, with a wide range of research directions. Research on sustainable communities in the design field has not formed a systematic research structure.

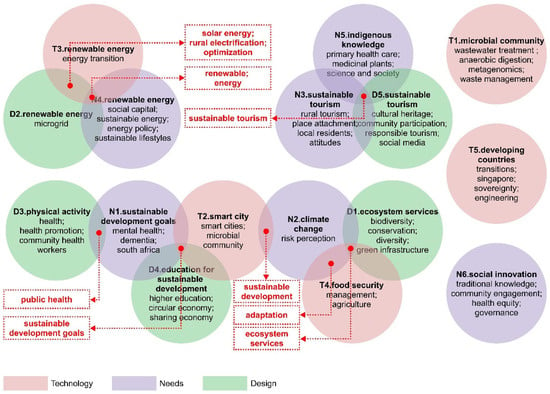

4.3. Keyword Clustering Analysis

Table 2 presents keyword clusters related to sustainable communities from the perspectives of technology, needs/demand, and design. The technical topics include microbial communities, smart cities, renewable energy, food security, and challenges faced by developing countries. The demand perspective emphasizes sustainable development goals, climate change, sustainable tourism, renewable energy, indigenous knowledge, and social innovation. The design perspective encompasses ecosystem services, renewable energy, physical activity, education for sustainable development, and sustainable tourism. A comparison of research topics across these clusters (Figure 8) revealed intersections among the technology, needs/demand, and design perspectives. The red clusters in Figure 8 represent technical perspectives, while the purple and green clusters correspond to demand and design perspectives, respectively. Notably, sustainable development goals, ecosystem services, and renewable energy have been common research topics across all three perspectives. Additionally, sustainable tourism and public health have been addressed from both the needs/demand and design perspectives, whereas sustainable development and adaptation are prevalent in the research from both the technological and needs/demand perspectives.

Table 2.

The clusters involved in this study.

Figure 8.

Intersection of research into technology, needs and design.

4.4. Research Clustering Timeline

To understand the origins, advancements, and emerging trends in research into sustainable communities, as well as to identify key topics in the research and development process, we created a research clustering timeline diagram based on keyword cluster analysis, as illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Research clustering timeline from the perspectives of technology, needs and design.

In the field of sustainable community technology, some research topics have existed for a long time, first appearing before 2014, and these continue to receive ongoing attention. These perspectives have been studied for at least 10 years and have developed steadily. Among the five identified clusters, three can be classified as long-term active research topics: microbial communities, smart cities, and food security. Combining microbial community and sustainable technology perspectives has yielded significant research results in environmental science, agronomy, biology, and other disciplines. Microbial fuel cells (MFCs) are potentially a sustainable method for treating wastewater via organic acid fermentation without any pretreatment, requiring detailed analysis of MFCs’ microbial communities [25]. In addition, research on the technological aspects of sustainable community renewal is a long-term topic in developing countries. Reviewing successful cases of appropriate technology (AT), H Shin et al. [26] conclude that the basic principles and framework of grassroots innovation (GI) can be applied to AT projects as a driving force for sustainable development in developing countries: background, driving force, niche, organizational form, and resource foundation.

In the field of sustainable community needs, development goals, climate change and sustainable tourism have been concerns for researchers for nearly 10 years. Måns Nilsson’s team [27] proposed a method for evaluating the relationships among goals, to help policymakers better understand the interdependence between sustainable development goals. Hoegh-Guldberg et al. [28] discussed the recent IPCC special report on global warming of 1.5 °C, noting that these upgraded climate-related risks may hinder the realization of the United Nations’ sustainable development goals, especially for low- and middle-income countries. Targeting underdeveloped regions with tourism development potential, HLK Leite et al. [29] identified cooperation as an effective strategy for promoting economic development in underdeveloped regions through tourism routes, and called for future research that could utilize a geographic perspective to examine the differences between the Eastern and Western paradigms, focusing on the concepts of destinations and smart destinations, including their impacts on tourists. G Yfantidou et al. [30] noted that sustainable tourism was currently seen as a tool for economic development, population welfare, and environmental protection. Local governments should be empowered financially to play a significant role in providing adequate infrastructure, leadership, legislation, and financial support. Facilities, products, and services also needed to be repositioned to attract tourists to these destinations.

In the field of sustainable community design, five research topics have long existed and have received scholars’ attention: ecosystem services, renewable energy, physical activity, education for sustainable development, and sustainable tourism. First, for communities with ecotourism aspirations, the three key areas most in need of multilateral support are waste management, reception skills, and market access [31]. Second, a lot of work has been carried out using solar and wind energy as renewable energy sources, but ocean energy has only recently been seriously considered. B Soudan [32] assessed the potential for coastal communities in underdeveloped regions to utilize marine energy for power generation and proposed an off-grid baseload generation system design. Third, Bjørnarå et al. [33] introduced the concept of sustainable sports activities, proposing that active transportation is not only a carbon-friendly mode of transportation but also an opportunity to increase physical activity. Sports activities in local communities can promote sustainability by reducing fossil fuel consumption. Fourth, higher education institutions (HEIs) can play a crucial role in achieving a sustainable societal transformation in the future. Berchin et al. [34] focused on discussing development, education, research, and training. Therefore, community resilience is enhanced by promoting knowledge and collaboration within local communities. Fifth, Seduikyte, et al. [35] proposed a preliminary framework for sustainable community-based tourism (SCBT), offering an important development direction for promoting research and sustainability-oriented practices, accelerating tourism development, and optimizing its management in the 21st century.

4.5. Research Trend Analysis

Table 3 presents the relevant information on emerging terms related to sustainable communities from the perspectives of technology, needs/demand, and design. This information aids in understanding the changes in research directions within these fields.

Table 3.

Emergence of words involved in this study.

At the technical level, the evolution of emerging terms can be divided into periods. Between 2014 and 2016, the research focused on community and wastewater treatment [36]. From 2017 to 2019, keywords emerged such as developing countries, decision making, sustainable energy, and community energy [26]. Ecosystem services and artificial intelligence also gained attention, with the former playing a crucial role in promoting the well-being and livelihood of vulnerable communities and the latter becoming increasingly popular in architecture, engineering, and construction [37].

At the demand level, emerging terms have shown a connecting pattern, with no new terms appearing in the past two years. Participation, energy, and social innovation are the latest keywords of interest. Stakeholder participation in community renewal is significant, and more participation can lead to a better, more comprehensive and accurate understanding of needs [38].

Management and public health were the earliest keywords relating to sustainable community design. A comprehensive decision-making structure was developed to support the sustainable management of Australian community buildings [39], and a conceptual framework was created to understand the characteristics of effective community participation [40]. Multi-functional land use is also becoming increasingly common, combining traditional agricultural production with convenient facilities and environmental protection [41]. Finally, in recent years, tourism has gained high attention and is likely to be a hotspot for design-level research in the coming years.

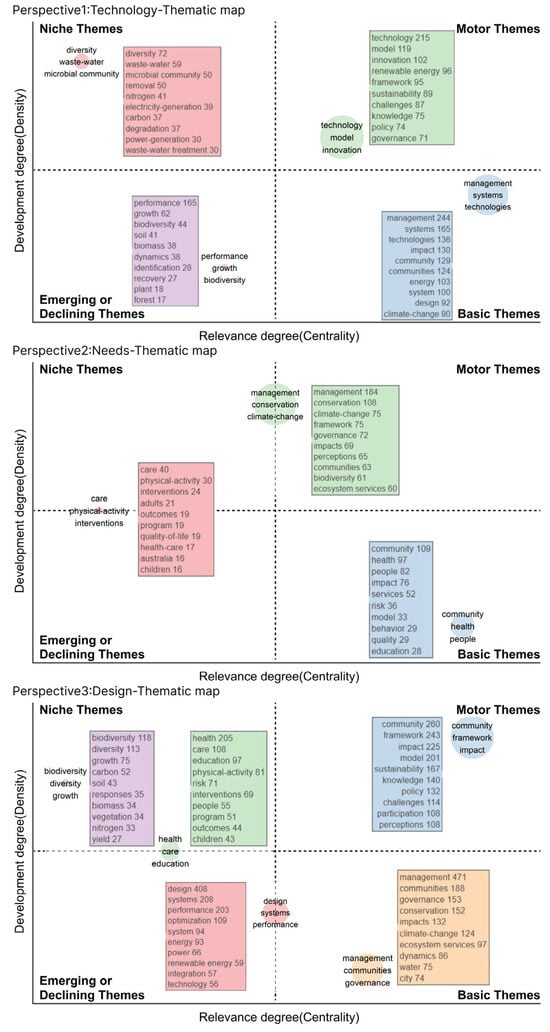

To investigate the dynamic patterns of research perspectives over time, we mapped all the clusters into a strategic diagram using two metrics: centrality and density [42]. Figure 10 displays the thematic map generated by the Bibliometrix R tool. The horizontal axis represents centrality (degree of relevance), while the vertical axis represents density (degree of development). Centrality measures the association between different topics, and density measures the cohesion between nodes. These attributes reflect the importance and development of topics.

Figure 10.

Thematic map from the perspectives of technology, needs and design.

In Figure 10, the first quadrant represents motor themes (important and well-developed), the second quadrant represents basic themes (highly developed and isolated), the third quadrant represents emerging or declining themes (marginal), and the fourth quadrant represents niche themes (important but not well developed). In relation to sustainable communities, technology and innovation are important research topics with strong development. By contrast, diversity, wastewater, and the microbial community are highly important but remain marginal and underdeveloped. Management-, systems-, and technology-related topics exhibit the best development status, while research into performance, growth, and biodiversity has garnered the least attention and development. Furthermore, sustainable community demand, management, conservation, and climate change are the most relevant and important topics. Community, health, and people represent well-developed basic topics, while care, physical activity, and interventions are the least valued. In sustainable community design, community, framework, and impact are important and well-developed topics, whereas management, communities, and governance are basic themes with good development status but lower importance. Finally, design, systems, and performance are marginal themes, while topics related to health, caring, education, biodiversity, diversity, and growth are not highly developed.

5. Discussion

5.1. Development Status and Problems

With regard to the current perspectives on development, the discussion surrounding sustainable communities has gained significant momentum, propelled by green development policies and robust sustainable development organizations. In the coming years, it is anticipated that topics related to sustainable communities will become a central focus of global academic discourse. Countries worldwide are actively pursuing both practical project implementation and theoretical exploration aimed at fostering sustainable community development. Regarding research trends and collaborations, the focus is primarily on sustainable community design. This focus encompasses a range of sustainable development activities, including intangible experience and service design, and the practical application of design standards and strategic approaches to the promotion of sustainable communities. Technological research with regard to sustainable communities has been particularly influential, offering a wealth of opportunities and potential for community building. Notably, the United States has been a leader in research on technology, needs, and design topics, and China is emerging as a promising contributor to the field. International collaborations are active, particularly in U.S.–China-led technological collaborations and U.K.–U.S.-led demand-related collaborations. The United States is also a major hub for international collaboration on design topics. Significant progress has been made in the area of sustainable community technologies, while relatively little research has been conducted on the demand side. Research in the area of design for sustainable communities has been the most comprehensive, with some scholars making notable breakthroughs. Research hotspots in relation to the theme of technology have focused on microbial communities, smart cities, renewable energy, food security, and developing countries, with growing interest in ecosystem services and artificial intelligence. The theme of demand emphasizes the Sustainable Development Goals, climate change, sustainable tourism, renewable energy, indigenous knowledge, and social innovation. The design perspective focuses on ecosystem services, renewable energy, and sustainable development through physical education and tourism, with tourism expected to be a central focus in the coming years.

Despite significant progress, there are still some limitations affecting research into sustainable communities.

- (1)

- From a technological perspective, cutting-edge advancements have long been influential; however, research in this area has often been confined to singular analysis and an outlook on application prospects, neglecting the grounded recommendations essential for the overall development of communities, particularly in underdeveloped regions. The unique challenges faced by these areas, such as limited access to resources and technology, underscore the importance of tailoring technological solutions to their specific contexts. Therefore, there is a pressing need to integrate the diverse fields of environmental science, social science, and economics to foster a more comprehensive understanding of the dynamics of sustainable communities.

- (2)

- From the perspective of need, there is a necessity for a more comprehensive understanding of the diverse and complex requirements of communities, which encompass both fundamental physiological needs and intricate socio-cultural needs. Specifically, the assessment of these needs in practice is currently restricted to individual cases and is challenging to address comprehensively on a larger scale. Consequently, an in-depth exploration of these needs is essential for the development of effective and inclusive sustainable community strategies.

- (3)

- From a design perspective, there is a recognized deficiency in systematic research frameworks, despite the abundance of existing research. The incorporation of design thinking, which prioritizes user-centered innovation and meaningful experiences, is essential for addressing the aesthetic, functional, and cultural dimensions of sustainable community development. Consequently, there is a pressing need for more comprehensive and strategic research into design, to effectively inform the development of sustainable communities.

5.2. Sustainable Strategy of Community Development

Based on research findings and emerging trends in sustainable communities over the past decade, we have developed an initial strategic model for sustainable community construction, as illustrated in Figure 11. Evidently, technology serves as the foundation and demand as the guide, combining relevant design specifications and theories to promote the comprehensive development of sustainable communities and provide detailed sustainable solutions for a greater number of communities.

Figure 11.

Strategic diagram for sustainable community solutions.

5.2.1. Consolidating the Technical Base

Viewing sustainable communities from a technological perspective, utilizing technology to address energy challenges is a key area of research. As a solution for sustainable development, community-based renewable energy necessitates thorough assessment and planning of resources, as energy systems consist of complex structures that include supply, transmission, distribution, and demand [43]. Regarding energy management, the strategic implementation of energy storage systems can enhance energy utilization rates and address temporal or local discrepancies between supply and demand. Community energy storage (CES) is anticipated to play a significant role in the energy transition [44], offering new opportunities for citizen engagement, increasing awareness of energy consumption and its environmental impacts [45], and necessitating effective communication and collaboration among community members. Waste management is also a critical aspect of energy issues, requiring the monitoring of waste logistics to promote resource utilization and safe disposal [46]. Furthermore, zero-emission neighborhoods (ZENs) represent an innovative concept, featuring responsive building clusters integrated into sustainability strategies [47].

Regional diversity in geography, economy, society, and culture necessitates the customization and optimization of energy policies and initiatives to fit local contexts. Solar energy stands out as the most effective clean-energy solution in some areas, while wind or geothermal energy may be better suited in others. In less developed regions, energy policy should focus on technologies tailored to local conditions, aiming to enhance energy access, curtail consumption, and alleviate energy poverty [48,49]. Moreover, the energy justice framework underscores the importance of equitable resource distribution, procedural fairness, and redress for historical injustices within the energy sector [50]. It is imperative that these principles guide the development and execution of energy policies and programs in underdeveloped areas, to ensure a just distribution of energy resources and to foster equitable social and economic progress.

Since the late 20th century, smart development has become central to the future of urban exploration. To foster sustainable communities, cities should adopt a smart approach as a guiding vision [51], which has been widely mentioned in relation to concepts such as “smart city”, “ecological city”, and “resilient city”. Community engagement is a recent topic in smart cities [52], with mobile applications related to sustainable development providing practical functions such as energy management tools, carbon footprint calculators, and sustainable transportation planning. The construction of basic digital infrastructure is a prerequisite for the development of smart cities. Less developed regions should prioritize investment in broadband networks and mobile communications technologies to ensure the rapid flow of information [53]. There is also a need to focus on utilizing low-cost smart technologies, such as solar-powered LED streetlights and low-cost sensors, to improve energy efficiency and reduce maintenance costs.

5.2.2. Clarifying Demand Orientation

The deficiencies in research into sustainable community development from a needs perspective include limited practical application, insufficient stakeholder engagement, under exploration of social needs and esteem, neglect of cultural needs and those relating to accessibility, and unmet needs in relation to self-actualization. Addressing these gaps is crucial for developing effective and inclusive strategies that can truly realize the potential of sustainable communities. Clearly defined needs help clarify the direction of tasks. In the process of building sustainable communities, it is essential to involve an increasing number of stakeholders in the development and management of community projects [54]. Maslow’s theory of the hierarchy of needs provides a theoretical framework that categorizes human needs into five levels: physiological, safety, social, esteem, and self-actualization [55]. This framework implies that community planners require a more holistic perspective to effectively interact and communicate with community stakeholders.

The Sustainable and Healthy Communities (SHC) program supports decisions fostering community sustainability by addressing the physiological and safety needs of residents [56]. Meanwhile, community energy initiatives (CEIs) offer opportunities for community participation, providing motivation and direct feedback on residents’ basic energy needs, to enable optimization [57]. Furthermore, sustainable community planners should foster social interaction, promote active participation, and establish partnerships to strengthen community cohesion and social connections. Ray Oldenburg’s concept of “third space” addresses residents’ social needs by creating informal public gathering places [58].

Community planners should ensure equal opportunities for all residents, promoting diversity and inclusivity to address their needs. Community mental health (CMH) focuses on psychological education, treatment, intervention, and stabilizing individuals who have experienced crises [59]. Moreover, support for vulnerable groups and provision of social services demonstrate respect and care. On the other hand, communities should integrate cultural activities and resources with consideration for cultural diversity [60]. Sustainable community planning should also meet the accessibility-related design needs of, for example, people with physiological defects and decline in normal activity, such as the disabled and the elderly [61].

Needs that relate to self-actualization include individual growth, development potential, and the achievement of personal goals. Sustainable communities should provide education, training, and innovation opportunities, encouraging personal development and creativity [62], thereby supporting entrepreneurship, innovative thinking, and a sustainable economy to meet these self-actualization needs.

5.2.3. Updating Design Specifications and Theories

Sustainable communities face challenges due to the insufficient integration of design thinking from a design perspective, inadequate attention to community infrastructure design, ineffective community service design, outdated design theories and practices, and a lack of geographically diverse sustainability frameworks. Addressing these gaps is essential for developing a more comprehensive and effective approach to sustainable community design. Design plays a crucial role in sustainable communities, encompassing various forms of participation and shaping the vision and goals of sustainable communities. Design can be reflected in the traditional sense, with visual appearance at its core [63]. However, community infrastructure design often lacks sensitive integration in the context of society, culture, and space [64]. For example, renewable energy discourse mainly focuses on the technical economy, but advocating for the daily aesthetic of renewable energy infrastructure and considering design thinking to create meaningful experiences are also important [65].

Additionally, incorporating intangible experiences into the traditional design process leads to design in service of the community. The service model, a new model based on service design, primarily addresses value-added activities based on user value and contact points [66]. Particularly for vulnerable groups such as the elderly, optimizing the community medical service system is a key aspect of sustainable community construction.

Design theory based on design practice also requires attention (e.g., sustainable design assessment, strategies, and methods related to communities). Since the 1990s, assessment methods such as BREEAM, LEED, and CASBEE have been constantly updated, including in communities [67]. In recent years, neighborhood sustainability assessment tools have become an active research field. Especially in developing countries, excessive urban populations exacerbate social and economic problems, necessitating detailed and rich community sustainability frameworks for various geographical regions [68].

In terms of sustainable design strategies, new concepts of urbanism emphasize ecological responsibility, thus improving natural environmental performance. Professor Timothy Beatley’s Biophilic Cities concept emphasizes cities rich in natural resources, seeking to protect and develop nature, and deeply connected to the natural world [69]. Park green spaces (PGSs) are crucial in enhancing residents’ quality of life and promoting environmental sustainability [70]. Pocket parks, for example, are an important part of green community infrastructure, providing support for sustainable community construction. Construction of ventilation corridors is another design practice method, using natural water bodies, urban green spaces, and trunk roads to facilitate air circulation and improve comfort. Meanwhile, a healthy social environment should be considered as one of the core issues relating to sustainable development [71].

5.3. Limitations

This study has several limitations that must be acknowledged. First, the data sources were restricted by publication time, language, and type. These restrictions may have led to the omission of excellent research results in the field of sustainable communities. Second, this study on sustainable communities was divided into three levels, namely technology, needs/demand, and design, which may not have provided an accurate overview of the entire research landscape in relation to sustainable communities. Finally, the research in this paper remains mainly at the macro level, and micro-level inter-community differences still need to be explored and discussed more deeply. Future research should supplement and improve upon these levels. Despite these limitations, the combination of quantitative and qualitative analysis in this study offers a valuable perspective on sustainable community research over the past 10 years and provides important insights for future researchers in this field.

6. Conclusions

Sustainable communities are a hot topic in national sustainable development reports. This study systematically reviewed the formation of theoretical knowledge and developmental trends, providing significant insights into the construction of sustainable communities. The specific innovations are as follows:

- (1)

- Innovations in Theoretical Perspectives: In response to the prevailing emphasis on technological transformation outcomes in sustainable community research, which often neglects other vital aspects of community development, this article adopts Verganti’s perspective to advocate for development through design innovation that addresses profound emotional and socio-cultural needs. This framework transcends the limitations of traditional research by encompassing not only technical aspects but also social and economic influences on sustainable solutions.

- (2)

- Construction of the Strategy System: This article presents a preliminary model for sustainable community building and development strategies, informed by findings from sustainable community research over the past decade and anticipated future trends. The model is technology-driven and demand-oriented, integrating relevant design specifications and theories. Its goal is to foster the comprehensive development of sustainable communities, offering a new theoretical foundation and practical guidance for in-depth research and practice in this field. This approach holds significant theoretical and practical importance.

- (3)

- Integration of Multidisciplinary Approaches: This study has made innovative use of multidisciplinary integration in the field of sustainable community research, adopting analytical tools such as CiteSpace, VOSviewer, and Bibliometrix R to expand the research scope of the literature review. In addition, this study covers many disciplines, such as environmental sciences, social sciences, and economics, and builds a multidimensional, interdisciplinary, and comprehensive research system.

Considering this study’s limitations, future research should explore in depth issues relating to sustainable communities from the perspective of long-term development processes and multi-disciplinary research, thereby offering diverse solutions for the future development of sustainable communities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H. and Z.Z.; methodology, J.L.; validation, M.J., C.S. and Q.H.; formal analysis, Z.Z.; resources, J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.H.; writing—review and editing, Z.Z.; visualization, M.H.; supervision, J.L.; funding acquisition, M.J., C.S. and Z.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research received fundings from Key Laboratory of New Technology for Construction of Cities in Mountain Area, Ministry of Education (Grant No. LNTCCMA-20240108), Postdoctoral Science Foundation of Chongqing (Grant No. cstc2021jcyj-bshX0044) and the 2020 Shanghai Pujiang Program (2020PJC026).

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/#goal_section (accessed on 13 November 2023).

- Toniolo, S.; Pieretto, C.; Camana, D. Improving sustainability in communities: Linking the local scale to the concept of sustainable development. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 101, 107126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, S.; Levinson, R.; Ndongo, E.; Holzer, P.; Kazanci, O.B.; Homaei, S.; Zhang, C.; Olesen, B.W.; Qi, D.; Hamdy, M.; et al. Resilient cooling of buildings to protect against heat waves and power outages: Key concepts and definition. Energy Build. 2021, 239, 110869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanghai Releases the “15 Minute Community Life Circle” Plan. Available online: https://www.mnr.gov.cn/dt/dfdt/201810/t20181030_2310520.html?eqid=9a5322410000f6f900000003648ffe39 (accessed on 13 November 2023).

- Macke, J.; Sarate, J.A.R.; de Atayde Moschen, S. Smart sustainable cities evaluation and sense of community. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 239, 118103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tim, Y.; Cui, L.; Sheng, Z. Digital resilience: How rural communities leapfrogged into sustainable development. Inf. Syst. J. 2021, 31, 323–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlström, L.; Broström, T.; Widén, J. Advancing urban building energy modelling through new model components and applications: A review. Energy Build. 2022, 266, 112099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Milner, D. Visualizing the research of embodied energy and environmental impact research in the building and construction field: A bibliometric analysis. Dev. Built Environ. 2020, 3, 100010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Era, C.; Marchesi, A.; Verganti, R. Mastering technologies in design-driven innovation. Res.-Technol. Manag. 2010, 53, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Koutra, S.; Zhang, J. Zero-carbon communities: Research hotspots, evolution, and prospects. Buildings 2022, 12, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, D. Knowledge map of urban morphology and thermal comfort: A bibliometric analysis based on citespace. Buildings 2021, 11, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirri, C.; Swanson, H.; Meenar, M. Finding the “heart” in the green: Conducting a bibliometric analysis to emphasize the need for connecting emotions with biophilic urban planning. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yang, L.; Ma, H. Community participation strategy for sustainable urban regeneration in Xiamen, China. Land 2022, 11, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, S.; Perlin, M.; Matsushita, R.; AP Santos, A.; Imasato, T.; Borenstein, D. Lotka’s law for the Brazilian scientific output published in journals. J. Inf. Sci. 2019, 45, 705–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Sjöklint, M.; Ukkonen, A. The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 2047–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi, S.; Kouhizadeh, M.; Sarkis, J.; Shen, L. Blockchain technology and its relationships to sustainable supply chain management. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 2117–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, E.J.; Rosen, B.R.; Baran, P.S. Synthetic organic electrochemistry: An enabling and innately sustainable method. ACS Cent. Sci. 2016, 2, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Song, H.; Jara, A.J.; Bie, R. Internet of things and big data analytics for smart and connected communities. IEEE Access 2016, 4, 766–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Biran, A.; Sit, J.; Szivas, E.M. Residents’ support for tourism development: The role of residents’ place image and perceived tourism impacts. Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnicka, E.; Napierała, P.; Podfigurna, A.; Męczekalski, B.; Smolarczyk, R.; Grymowicz, M. The World Health Organization (WHO) approach to healthy ageing. Maturitas 2020, 139, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alstone, P.; Gershenson, D.; Kammen, D.M. Decentralized energy systems for clean electricity access. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, K.; Conard, M.; Culligan, P.; Plunz, R.; Sutto, M.P.; Whittinghill, L. Sustainable food systems for future cities: The potential of urban agriculture. Econ. Soc. Rev. 2014, 45, 189–206. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, T.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Bian, C.; Wang, X.; Xu, P. Power generation and microbial community analysis in microbial fuel cells: A promising system to treat organic acid fermentation wastewater. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 284, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Hwang, J.; Kim, H. Appropriate technology for grassroots innovation in developing countries for sustainable development: The case of Laos. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 1167–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, M.; Griggs, D.; Visbeck, M. Policy: Map the interactions between Sustainable Development Goals. Nature 2016, 534, 320–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoegh-Guldberg, O.; Jacob, D.; Taylor, M.; Bolaños, T.G.; Bindi, M.; Brown, S.; Camilloni, I.A.; Diedhiou, A.; Djalante, R.; Ebi, K.; et al. The human imperative of stabilizing global climate change at 1.5 °C. Science 2019, 365, eaaw6974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, H.d.L.K.; Binotto, E.; Padilha, A.C.M.; Hoeckel, P.H.d.O. Cooperation in rural tourism routes: Evidence and insights. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 57, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yfantidou, G.; Matarazzo, M. The future of sustainable tourism in developing countries. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 25, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, A.; Ruhanen, L.; Mair, J. Ecosystem services approach for community-based ecotourism: Towards an equitable and sustainable blue economy. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1665–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soudan, B. Community-scale baseload generation from marine energy. Energy 2019, 189, 116134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnarå, H.B.; Torstveit, M.K.; Stea, T.H.; Bere, E. Is there such a thing as sustainable physical activity? Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2017, 27, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berchin, I.I.; Dutra, A.R.d.A.; Guerra, J.B.S.O.d.A. How do higher education institutions promote sustainable development? A literature review. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapera, I. Sustainable tourism development efforts by local governments in Poland. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 40, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobulescu, R.; Fritscheova, A. Convivial innovation in sustainable communities: Four cases in France. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 181, 106932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazeem, K.O.; Olawumi, T.O.; Osunsanmi, T. Roles of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Enhancing Construction Processes and Sustainable Communities. Buildings 2023, 13, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthies, A.; Peeters, J.; Hirvilammi, T.; Stamm, I. Ecosocial innovations enabling social work to promote new forms of sustainable economy. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2020, 29, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalutara, P.; Zhang, G.; Setunge, S.; Wakefield, R. Factors that influence Australian community buildings’ sustainable management. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2017, 24, 94–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunton, G.; Thomas, J.; O’mara-Eves, A.; Jamal, F.; Oliver, S.; Kavanagh, J. Narratives of community engagement: A systematic review-derived conceptual framework for public health interventions. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, C.; Hamerlinck, J.; McKinlay, A. Institutional support for building resilience within rural communities characterised by multifunctional land use. Land Use Policy 2023, 132, 106808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.Y.; Li, M. Worldwide trends in prediabetes from 1985 to 2022: A bibliometric analysis using bibliometrix R-tool. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1072521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolokotsa, D. The role of smart grids in the building sector. Energy Build. 2016, 116, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, B.P.; van Oost, E.; van der Windt, H. Community energy storage: A responsible innovation towards a sustainable energy system? Appl. Energy 2018, 231, 570–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, D.; Swierczynski, M.; Stroe, D.I.; Norman, S.; Abdon, A.; Worlitschek, J.; O’doherty, T.; Rodrigues, L.; Gillott, M.; Zhang, X.; et al. An interdisciplinary review of energy storage for communities: Challenges and perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 79, 730–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ddiba, D.; Andersson, K.; Rosemarin, A.; Schulte-Herbrüggen, H.; Dickin, S. The circular economy potential of urban organic waste streams in low-and middle-income countries. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 1116–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taveres-Cachat, E.; Grynning, S.; Thomsen, J.; Selkowitz, S. Responsive building envelope concepts in zero emission neighborhoods and smart cities—A roadmap to implementation. Build. Environ. 2019, 149, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Rivas, U.; Tahri, Y.; Arjona, M.M.; Chinchilla, M.; Castaño-Rosa, R.; Martínez-Crespo, J. Energy poverty in developing regions: Strategies, indicators, needs, and technological solutions. In Energy Poverty Alleviation: New Approaches Contexts; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 17–39. [Google Scholar]

- Benayed, W.; Awijen, H.; Bousnina, R.; Chroufa, M.A. Infrastructure for sustainable energy access in Sub-Saharan Africa: Leveraging social factors and natural capital. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 470, 143304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, D.; Ditta, A.A.; Cao, S.J. Energy justice and sustainable urban renewal: A systematic review of low-income old town communities. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 470, 143470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanelli, M. Analysing the role of information technology towards sustainable cities living. Kybernetes 2020, 49, 2037–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, B., Jr. The Role of Community Engagement in Urban Innovation Towards the Co-Creation of Smart Sustainable Cities. J. Knowl. Econ. 2023, 15, 1592–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Gu, J.; Martínez, O.S.; Crespo, R.G. Economic and environmental impacts of energy efficiency over smart cities and regulatory measures using a smart technological solution. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2021, 47, 101422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.S.; Adil, M.; Mirza, M.S.; Frigon, D. Sustainable community-based drinking water systems in developing countries: Stakeholder perspectives. J. Water Supply: Res. Technol. AQUA 2016, 65, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. Preface to motivation theory. Psychosom. Med. 1943, 5, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, N.; Lee, E.S.; Osterhaus, W.; Altomonte, S.; Amorim, C.N.D.; Ciampi, G.; Garcia-Hansen, V.; Maskarenj, M.; Scorpio, M.; Sibilio, S. Evaluation of integrated daylighting and electric lighting design projects: Lessons learned from international case studies. Energy Build. 2022, 268, 112191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloot, D.; Jans, L.; Steg, L. In it for the money, the environment, or the community? Motives for being involved in community energy initiatives. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 57, 101936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldosemani, T.I.; Shepherd, C.E.; Gashim, I.; Dousay, T. Developing third places to foster sense of community in online instruction. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2016, 47, 1020–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, L.; Roe, D. Recovery from versus recovery in serious mental illness: One strategy for lessening confusion plaguing recovery. J. Ment. Health 2007, 16, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, M.K.; Lee, M.H. Effects of community-based programs on integration into the mental health and non-mental health communities. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolidou, E.; Fokaides, P.A. Enhancing Accessibility: A Comprehensive Study of Current Apps for Enabling Accessibility of Disabled Individuals in Buildings. Buildings 2023, 13, 2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandri, O.J. Exploring the role and value of creativity in education for sustainability. Environ. Educ. Res. 2013, 19, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F. Design and implementation of industrial design and transformation system based on artificial intelligence technology. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarekegne, B. Just electrification: Imagining the justice dimensions of energy access and addressing energy poverty. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 70, 101639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Törnroth, S.; Nilsson, Å.W.; Luciani, A. Design thinking for the everyday aestheticisation of urban renewable energy. Des. Stud. 2022, 79, 101096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhu, T. Research on service design of community medical facilities based on aging-appropriate and elderly-centered. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. IOP Publ. 2019, 573, 012075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardi, U. Sustainability assessment of urban communities through rating systems. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2013, 15, 1573–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwasha, A.; Williams, R.G.; Iwaro, J. Modeling the performance of residential building envelope: The role of sustainable energy performance indicators. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 2108–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, F.; Gou, Z.; Lau, S.S.-Y.; Chung, K.-H.; Zhang, J. From biophilic design to biophilic urbanism: Stakeholders’ perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 211, 1444–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wang, C.; Deng, M.; Chen, Y. Coupling Coordination between Park Green Space (PGS) and Socioeconomic Deprivation (SED) in High-Density City Based on Multi-Scale: From Environmental Justice Perspective. Land 2023, 12, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Evaluating Parametric Form-Based Code for Sustainable Development of Urban Communities and Neighborhoods. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).