The Impact of Host–Guest Interactions Among Young People on Cultural Sustainability: A Case Study of Dialects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Host–Guest Interaction

2.2. Destination Dialect Perceptions

2.3. Exclusive Perceptions

2.4. Negative Emotions

2.5. Tourist Citizenship Behaviors

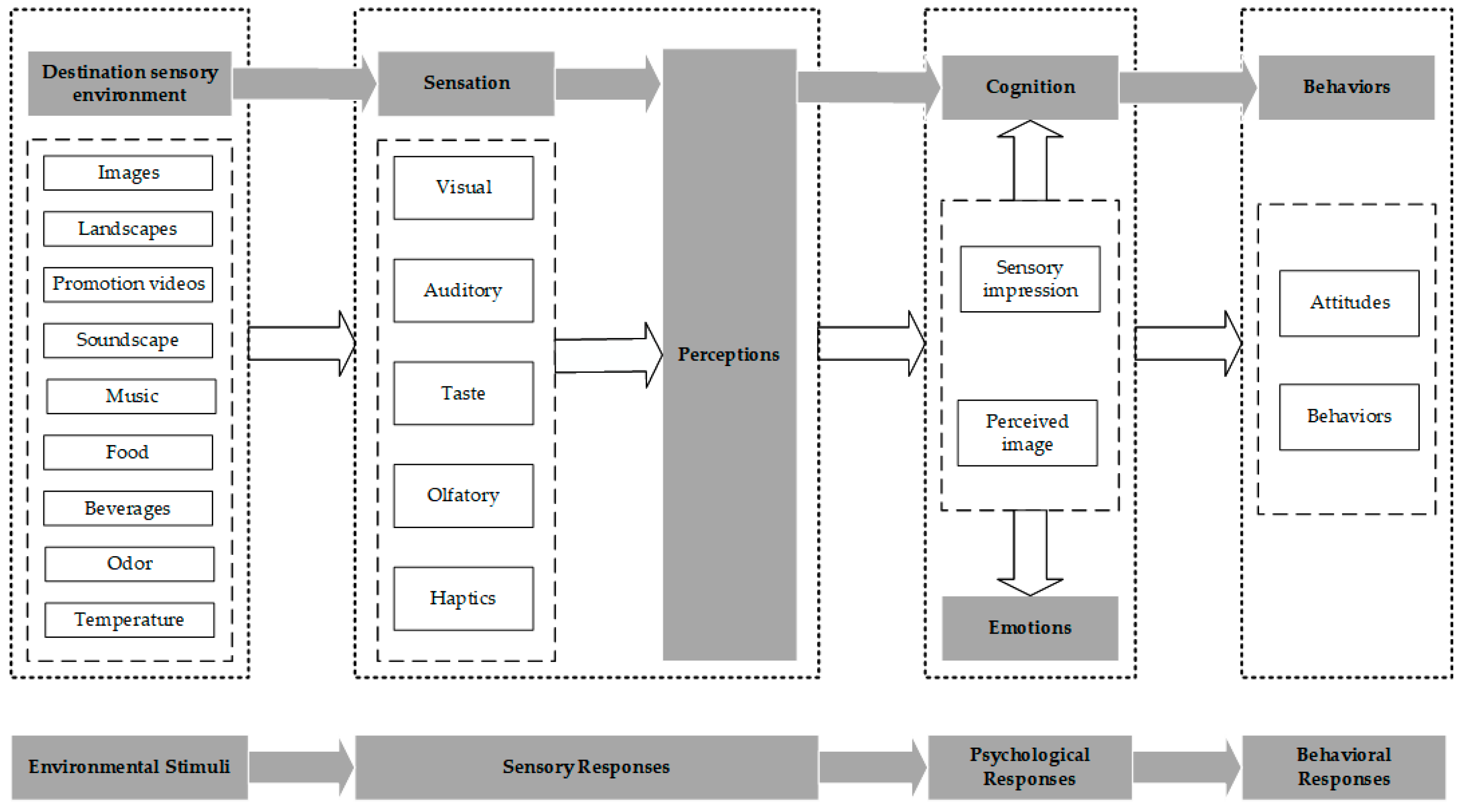

2.6. Sensory Marketing Theory

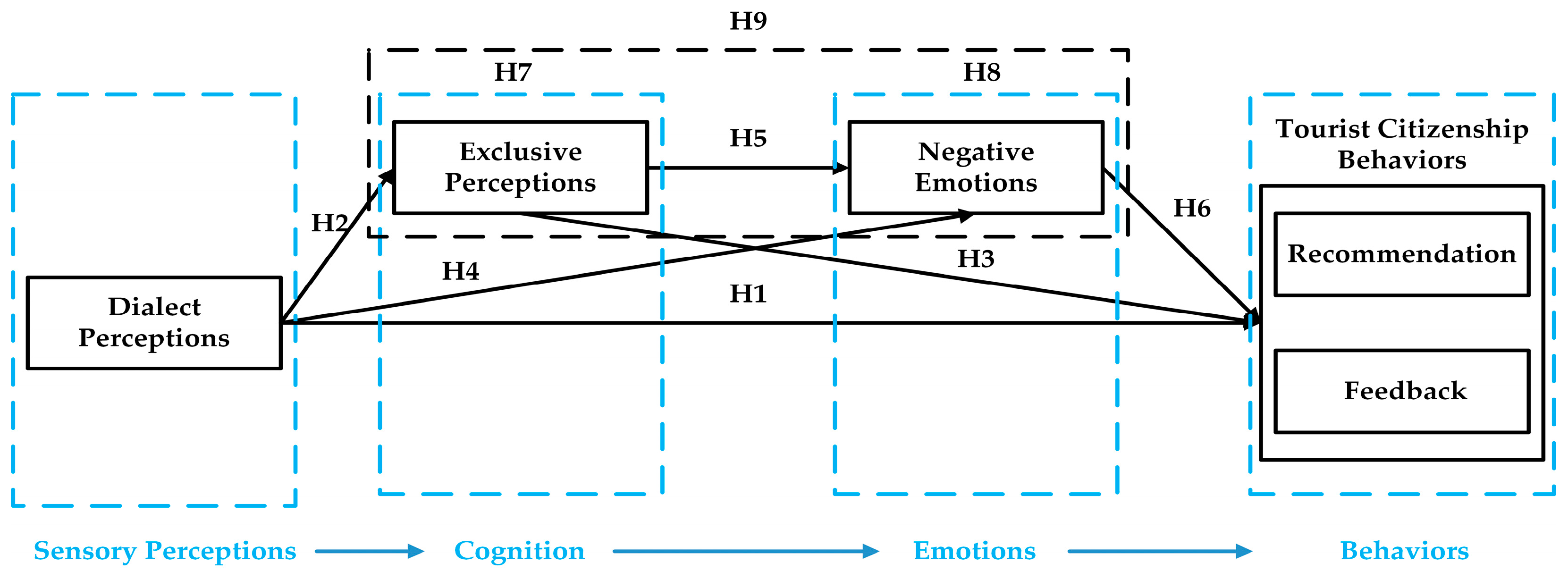

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. Destination Dialect Perceptions and Tourist Citizenship Behaviors

3.2. Destination Dialect Perceptions, Exclusive Perceptions, and Tourist Citizenship Behaviors

3.3. Destination Dialect Perceptions, Exclusive Perceptions, Negative Emotions, and Tourist Citizenship Behaviors

3.4. The Mediating Role of Exclusive Perceptions and Negative Emotions

3.5. Research Models

4. Methodology

4.1. Design of Measurements

4.2. Data Collection

4.3. Data Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Respondent Profile

5.2. Common Method Bias Analysis

5.3. Measurement Model Analysis

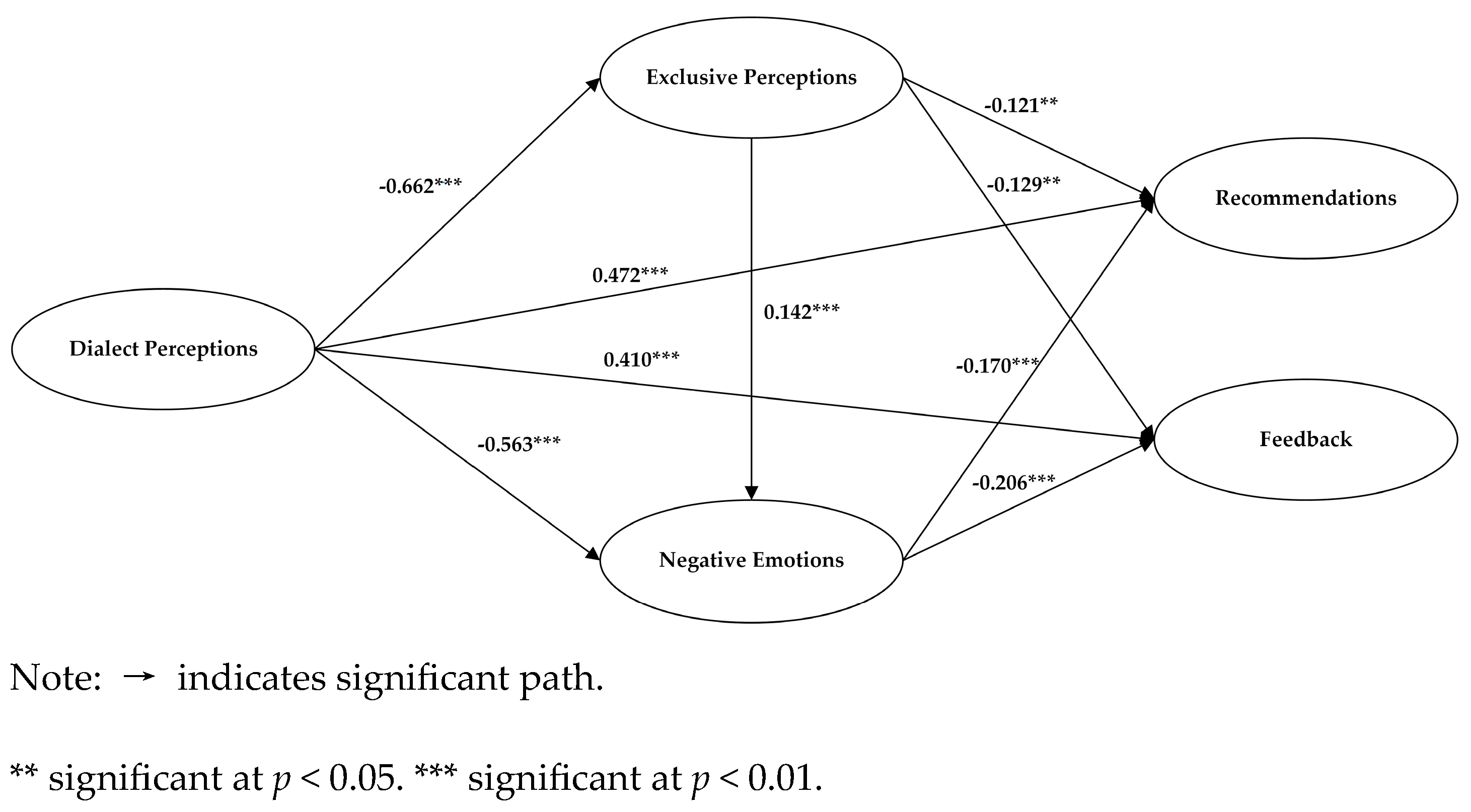

5.4. Structural Model Analysis

5.5. Multiple-Chain Mediation Effect Analysis

6. Discussion, Implications, and Limitations

6.1. Discussion

6.2. Theoretical Implications

6.3. Practical Implications

6.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhu, J.; Grigoriadis, T.N. Chinese Dialects, Culture & Economic Performance. China Econ. Rev. 2022, 73, 101783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Fang, F. ‘I Feel a Sense of Solidarity When Speaking Teochew’: Unpacking Family Language Planning and Sustainable Development of Teochew from a Multilingual Perspective. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2024, 45, 1375–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Tan, Z. Influence of Dialect Diversity on Level of Urban Innovation—Empirical Evidence Based on 276 Cities in China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 208, 123667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney-Squire, K. Sustaining Local Language Relationships through Indigenous Community-Based Tourism Initiatives. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonardi, S.; Martini, U.; Hull, J.S. Minority Languages as Sustainable Tourism Resources: From Indigenous Groups in British Columbia (Canada) to Cimbrian People in Giazza (Italy). Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 83, 102859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruch, H. Dialect Contact in Real Interactions and in an Agent-Based Model. Speech Commun. 2021, 134, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Promoting or Preventing Labor Migration? Revisiting the Role of Language. China Econ. Rev. 2020, 60, 101407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Do Languages Matter? The Impact of Local Dialect Proficiency on Multidimensional Poverty Alleviation among Rural-to-Urban Migrants in China. Cities 2024, 150, 105094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallay, E.; Pykett, A.; Smallwood, M.; Flanagan, C. Urban Youth Preserving the Environmental Commons: Student Learning in Place-Based Stewardship Education as Citizen Scientists. Sustain Earth 2020, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirehie, M.; Gibson, H.J.; Buning, R.J.; Coble, C.; Flaherty, M. Towards an Understanding of Family Travel Decision-Making Processes in the Context of Youth Sport Tourism. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 21, 100644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruesga-Benito, S.M.; González-Laxe, F.; Picatoste, X. Sustainable Development, Poverty, and Risk of Exclusion for Young People in the European Union: The Case of NEETs. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Látková, P.; Vogt, C.A. Residents’ Attitudes toward Existing and Future Tourism Development in Rural Communities. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, Y.; Faresse, S.; Henning, C.; Trotter, P.D.; Ackerley, R.; Croy, I. Measuring Differences in Social Touch: Development and Validation of the Short Touch Experiences and Attitudes Questionnaire (TEAQ-s). Personal. Individ. Differ. 2025, 233, 112890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Wei, M. Differences in Automatic Emotion Regulation after Social Exclusion in Individuals with Different Attachment Types. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2022, 185, 111296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, K.L.; Quas, J.A. Compensatory Prosocial Behavior in High-Risk Adolescents Observing Social Exclusion: The Effects of Emotion Feedback. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2024, 241, 105840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantano, E.; Viassone, M.; Boardman, R.; Dennis, C. Inclusive or Exclusive? Investigating How Retail Technology Can Reduce Old Consumers’ Barriers to Shopping. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 68, 103074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, K.-T.; Jiang, Y.; Teng, F. Putting Oneself in Someone’s Shoes: The Effect of Observing Ostracism on Physical Pain, Social Pain, Negative Emotion, and Self-Regulation. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 166, 110217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M.C.; Cogswell, J.E.; Smith, M.B. The Antecedents and Outcomes of Workplace Ostracism: A Meta-Analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maduku, D.K. How Environmental Concerns Influence Consumers’ Anticipated Emotions towards Sustainable Consumption: The Moderating Role of Regulatory Focus. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 76, 103593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arıca, R.; Çorbacı, A. The Mediating Role of the Tourists’ Citizenship Behavior between the Value Co-Creation and Satisfaction. Adv. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 8, 125–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultén, B. Sensory Marketing: An Introduction, 1st ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2020; ISBN 978-1-5264-2324-5. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.; Tu, H. Does Sincere Social Interaction Stimulate Tourist Immersion? A Conservation of Resources Perspective. J. Travel Res. 2023, 62, 469–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Cao, L. How Do Positive Host-Guest Interactions in Tourism Alter the Indicators of Tourists’ General Attachment Styles? A Moderated Mediation Model. Tour. Manag. 2024, 105, 104937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C. Cultural Similarity and Guest-Host Interaction for Virtual Tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 58, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apollo, M. Does the Altitude of Habitat Influence Residents’ Attitudes to Guests? A New Dimension in the Residents’ Attitudes to Tourism. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2020, 31, 100312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, H.; Ma, J. Does Positive Contact Between Residents and Tourists Stimulate Tourists’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior? The Role of Gratitude and Boundary Conditions. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 1774–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.A. Sustainable Tourism Employment: A Comprehensive Overview of Tourism Employees’ Experience from a Tourist-Employee Interaction Perspective. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 60, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woosnam, K.M.; Joo, D.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Johnson Gaither, C.; Sánchez, J.J.; Brooks, R. Rural Residents’ Social Distance with Tourists: An Affective Interpretation. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 27, 939–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, D.; Woosnam, K.M. Measuring Tourists’ Emotional Solidarity with One Another—A Modification of the Emotional Solidarity Scale. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 1186–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, C.B.; Deng, B.; Sun, J. Memorable Interactive Experiences between Hosts and Guests in B&Bs and Their Generation Process: The Host Perspective. Tour. Manag. 2024, 102, 104861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X. Host-Guest Interactions in Peer-to-Peer Accommodation: Scale Development and Its Influence on Guests’ Value Co-Creation Behaviors. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 110, 103447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Wu, W.; Liu, A.; Zhan, C.; Su, W. Tourists’ on-Site Immersive Experience for Shortening Psychological Distance in the Context of Homologous and Non-Homologous Cultures. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 58, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonardi, S.; Scholl-Grissemann, U.; Peters, M.; Messner, N. Leveraging Minority Language in Destination Online Marketing: Evidence from Alta Badia, Italy. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2024, 31, 100857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J. Integration of Migrants in Poverty Alleviation Resettlement to Urban China. Cities 2022, 120, 103501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Kong, F. Association Between Intergenerational Support, Social Integration, and Subjective Well-Being Among Migrant Elderly Following Children in Jinan, China. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 870428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Chen, G.; Huang, S.S.; Bao, J. Understanding Chinese Tourists’ Perceptions of Cantonese as a Regional Dialect. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitlin, S.; Kwon, H.W.; Firat, R. In- and out-Groups across Cultures: Identities and Perceived Group Values. Soc. Sci. Res. 2021, 97, 102569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Long, Z.; Chen, L.; Li, W. How Does Linguistic Diversity Matter? The Case of Trade Credit. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 92, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharchuk, H.A.; Shevlin, A.; van Hell, J.G. Are Our Brains More Prescriptive than Our Mouths? Experience with Dialectal Variation in Syntax Differentially Impacts ERPs and Behavior. Brain Lang. 2021, 218, 104949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Yan, B. From Soundscape Participation to Tourist Loyalty in Nature-Based Tourism: The Moderating Role of Soundscape Emotion and the Mediating Role of Soundscape Satisfaction. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2022, 26, 100730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Z. How Does a Historical Linguistic Landscape Influence Tourists’ Behavioral Intention? A Mixed-Method Study. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2024, 53, 101294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinuales, G.; Thomas, V.L. Not so Social: When Social Media Increases Perceptions of Exclusions and Negatively Affects Attitudes toward Content. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, I. Feeling Included and Excluded in Organizations: The Role of Human and Social Capital. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paşamehmetoğlu, A.; Guzzo, R.F.; Guchait, P. Workplace Ostracism: Impact on Social Capital, Organizational Trust, and Service Recovery Performance. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 50, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beld, M.H.M. The Impact of Classroom Climate on Students’ Perception of Social Exclusion in Secondary Special Education. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 103, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matías-García, J.A. From Current to Possible Selves: Self-Descriptions of Resilient Post-Compulsory Secondary Education Spanish Students at Risk of Social Exclusion. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2023, 155, 107257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, L.M. Enhancing Leader Inclusion While Preventing Social Exclusion in the Work Group. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2023, 33, 100902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Chen, K.; Guo, X. Online Anthropomorphism and Consumers’ Privacy Concern: Moderating Roles of Need for Interaction and Social Exclusion. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.; Mattila, A.S. Feeling Left out and Losing Control: The Interactive Effect of Social Exclusion and Gender on Brand Attitude. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjåstad, H. Short-Sighted Greed? Focusing on the Future Promotes Reputation-Basedgenerosity. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2019, 14, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L. The Influence of Social Exclusion on Adolescents’ Social Withdrawal Behavior: The Moderating Role of Connectedness to Nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 87, 101951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, J.-H.; Park, M.; Yoo, J. The Roles of Sensory Perceptions and Mental Imagery in Consumer Decision-Making. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, A. An Integrative Review of Sensory Marketing: Engaging the Senses to Affect Perception, Judgment and Behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2012, 22, 332–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, S.; Tung, V.W.S. Understanding Residents’ Attitudes towards Tourists: Connecting Stereotypes, Emotions and Behaviours. Tour. Manag. 2022, 89, 104435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashdan, T.B.; Farmer, A.S. Differentiating Emotions across Contexts: Comparing Adults with and without Social Anxiety Disorder Using Random, Social Interaction, and Daily Experience Sampling. Emotion 2014, 14, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Zhang, J.; Qiu, M.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, H. From Mixed Emotional Experience to Spiritual Meaning: Learning in Dark Tourism Places. Tour. Geogr. 2019, 22, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monterrubio, C.; Andriotis, K.; Rodriguez-Munoz, G. Residents’ Perceptions of Airport Construction Impacts—A Negativity Bias Approach. Tour. Manag. 2020, 77, 103983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.B.; Yan, L.; Mak, C.K. Service Encounter Failure, Negative Destination Emotion and Behavioral Intention: An Experimental Study of Taxi Service. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 40, 100886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Kim, J.-H. The Cause-Effect Relationship between Negative Food Incidents and Tourists’ Negative Emotions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M.J. Memories Are Not All Positive: Conceptualizing Negative Memorable Food, Drink, and Culinary Tourism Experiences. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2024, 54, 101296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawijn, J.; Biran, A. Negative Emotions in Tourism: A Meaningful Analysis. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 2386–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Tang, B.; Nawijn, J. Eudaimonic and Hedonic Well-Being Pattern Changes: Intensity and Activity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 103008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Revenge Buying: The Role of Negative Emotions Caused by Lockdowns. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 75, 103523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Liu, Y.; Hu, J.; Cao, X. The Effect of Tourist-to-Tourist Interaction on Tourists’ Behavior: The Mediating Effects of Positive Emotions and Memorable Tourism Experiences. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 55, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gezhi, C.; Xiang, H. From Good Feelings to Good Behavior: Exploring the Impacts of Positive Emotions on Tourist Environmentally Responsible Behavior. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 50, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Attribution Theory and Negative Emotions in Tourism Experiences. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 40, 100904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, M. Customers as Good Soldiers: Examining Citizenship Behaviors in Internet Service Deliveries. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.S.; Tsaur, S.-H. We Are in the Same Boat: Tourist Citizenship Behaviors. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Jayawardhena, C.; Osburg, V.-S.; Yoganathan, V.; Cartwright, S. Social Sharing of Consumption Emotion in Electronic Word of Mouth (eWOM): A Cross-Media Perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, G.; Liu, M.; Xu, J.; Cao, J.; Yang, J. How Does Tour Guide Humor Influence Tourist Citizenship Behavior? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 50, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, S.-H.; Yang, T.-L.; Tsai, C.-H. Tour Leader Likeability and Tourist Citizenship Behaviours: Mediating Effect of Perceived Value. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 2628–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J. Identifying Antecedents and Consequences of Well-Being: The Case of Cruise Passengers. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 33, 100609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Li, C.S.; McCabe, S. Expanding Theory of Tourists’ Destination Loyalty: The Role of Sensory Impressions. Tour. Manag. 2020, 77, 104026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Wong, I.A.; Lin, Z.C. How Folk Music Induces Destination Image: A Synthesis between Sensory Marketing and Cognitive Balance Theory. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2023, 47, 101123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trang, N.T.; Yoo, J.J.-E.; Joo, D.; Lee, G. Incorporating Senses into Destination Image. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2023, 27, 100760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, L.H.N.; Lei, S.S.I.; Chow, C.W.C.; Lam, L.W. Sensory Marketing in Hospitality: A Critical Synthesis and Reflection. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 35, 2916–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.W.; Wan, L.C. Inspiring Tourists’ Imagination: How and When Human Presence in Photographs Enhances Travel Mental Simulation and Destination Attractiveness. Tour. Manag. 2025, 106, 104969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losada, N.; Mota, G. “Slow down, Your Movie Is Too Fast”: Slow Tourism Representations in the Promotional Videos of the Douro Region (Northern Portugal). J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 11, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, M. Visual Elements in Advertising Enhance Odor Perception and Purchase Intention: The Role of Mental Imagery in Multi-Sensory Marketing. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 78, 103752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.-H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, X.; Liu, P.; Zhuang, M.; Hu, M. Flow in Soundscape: The Conceptualization of Soundscape Flow Experience and Its Relationship with Soundscape Perception and Behaviour Intention in Tourism Destinations. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 2090–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J. The Role of Natural Soundscape in Nature-Based Tourism Experience: An Extension of the Stimulus–Orga. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 25, 707–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, T.; Woszczynski, A.B.; Crowell, D. Musical Attributes, Cultural Dimensions, Social Media: Insights for Marketing Music to Consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 82, 104103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, A.M.W.; Yeh, S.-S.; Zhou, Y.; Hung, C.-W.; Huan, T.-C. Exploring the Influence of Historical Storytelling on Cultural Heritage Tourists’ Value Co-Creation Using Tour Guide Interaction and Authentic Place as Mediators. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2024, 50, 101198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chang, M.; Luo, X.; Qiu, R.; Zou, T. How Perceived Authenticity Affects Tourist Satisfaction and Behavioral Intention towards Natural Disaster Memorials: A Mediation Analysis. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2023, 46, 101085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, J. Social Identity Theory. In The International Encyclopedia of Media Psychology; Bulck, J., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–7. ISBN 978-1-119-01107-1. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, G.; Hu, J.; Du, Q.; Xiang, M. Impact of Sincere Social Interaction on Tourist Citizenship Behavior—Perspective from “Self” and “relationships. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 61, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldorai, K.; Kim, W.G.; Li, J.J. I’m Broken inside but Smiling Outside: When Does Workplace Ostracism Promote pro-Social Behavior? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 101, 103088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, B. Emotions Are Social. Br. J. Psychol. 1996, 87, 663–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, J.; Hwang, Y. Sending Warmth with Corporate Social Responsibility Communication: Leveraging Consumers’ Need to Belong. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 54, 336–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, G.; Dewani, P.P.; Kulashri, A. Social Exclusion and Consumer Responses: A Comprehensive Review and Theoretical Framework. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 1537–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The Role of Positive Emotions in Positive Psychology. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Lu, C. Does Tourism Mental Fatigue Inhibit Tourist Citizenship Behavior? The Role of Psychological Contract Breach and Boundary Conditions. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 55, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.K.; Sharma, A.; Bose, S.; Singh, G. Consumer-Brand Relationship: A Brand Hate Perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 144, 1293–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhigang, W.; Lei, Z.; Xintao, L. Consumer Response to Corporate Hypocrisy from the Perspective of Expectation Confirmation Theory. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 580114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Du, Y.; Wang, S. Service Robots vs. Human Staff: The Effect of Service Agents and Service Exclusion on Unethical Consumer Behavior. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 55, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.Q.; Lau, V.M.-C. COVID-19-Induced Negative Emotions and the Impacts on Personal Values and Travel Behaviors: A Threat Appraisal Perspective. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 51, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwu, F.; Nwali, A.C.; Ugwu, L.E.; Okafor, C.O.; Ozurumba, K.C.; Onyishi, I.E. Mediating Roles of Employee Cynicism and Workplace Ostracism on the Relationship between Perceived Organizational Politics and Counterproductive Work Behavior. Career Dev. Int. 2023, 28, 314–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.W.-C.; Pan, S.-Y. Different Emotional and Behavioral Reactions to Customer Mistreatment among Hotel Employees: A Multilevel Moderated Mediation Model. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 54, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Cheng, Y.; Ni, Y. Staging a Comeback? The Influencing Mechanism of Tourist Crowding Perception on Adaptive Behavior. Tour. Manag. 2024, 100, 104827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, V.T.; Nguyen, N.; Pervan, S. Retailer Corporate Social Responsibility and Consumer Citizenship Behavior: The Mediating Roles of Perceived Consumer Effectiveness and Consumer Trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X. Why Does Service Inclusion Matter? The Effect of Service Exclusion on Customer Indirect Misbehavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 68, 103005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunçel, N.; Kavak, B. Being an Ethical or Unethical Consumer in Response to Social Exclusion: The Role of Control, Belongingness and Self-esteem. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Lee, C.-K.; Sirgy, M.J. Examining the Differential Impact of Human Crowding versus Spatial Crowding on Visitor Satisfaction at a Festival. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, E.W.; Xu, J.; Ding, Y. To Be or Not to Be Unique? The Effect of Social Exclusion on Consumer Choice. J. Consum. Res. 2014, 40, 1109–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Muktadir, M.G. SPSS: An Imperative Quantitative Data Analysis Tool for Social Science Research. Int. J. Res. Innov. Soc. Sci. 2021, 05, 300–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 3. SmartPLS GmbH, Boenningstedt. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. 2024, 10, 32–49. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Pick, M.; Liengaard, B.D.; Radomir, L.; Ringle, C.M. Progress in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling Use in Marketing Research in the Last Decade. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 1035–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, M.; Yun, J.; Yu, S. My Smart Speaker Is Cool! Perceived Coolness, Perceived Values, and Users’ Attitude toward Smart Speakers. Int. J. Hum. –Comput. Interact. 2021, 37, 560–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-J.; Van Witteloostuijn, A.; Eden, L. Common Method Variance in International Business Research. In Research Methods in International Business; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avkiran, N.K. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: Recent Advances in Banking and Finance; International Series in Operations Research and Management Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-71691-6. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H.J.; Shin, J.; Ponto, K. How 3D Virtual Reality Stores Can Shape Consumer Purchase Decisions: The Roles of Informativeness and Playfulness. J. Interact. Mark. 2020, 49, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, P.; Wood, E. Familiarity and Novelty in Aesthetic Appreciation: The Case of Intangible Cultural Heritage in China. Ann. Tour. Res. 2024, 105, 103696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assiouras, I.; Skourtis, G.; Giannopoulos, A.; Buhalis, D.; Koniordos, M. Value Co-Creation and Customer Citizenship Behavior. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 78, 102742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Ma, X.; Xu, X.; Liu, Y. Treat for Affection? Customers’ Differentiated Responses to pro-Customer Deviance. Tour. Manag. 2022, 93, 104619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinucci, M.; Mazzoni, D.; Pancani, L.; Riva, P. To Whom Should I Turn? Intergroup Social Connections Moderate Social Exclusion’s Short- and Long-Term Psychological Impact on Immigrants. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 99, 104275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Who Sets Prices Better? The Impact of Pricing Agents on Consumer Negative Word-of-Mouth When Applying Price Discrimination. Tour. Manag. 2025, 106, 105003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Wei, W.; Lyu, J. Does Linguistic Diversity Make Destinations More Sophisticated? Exploring the Effects on Destination Personality. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2024, 31, 100828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, M. Connecting Tourists to Musical Destinations: The Role of Musical Geographical Imagination and Aesthetic Responses in Music Tourism. Tour. Manag. 2023, 98, 104768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Luo, Q.; Li, M. Meaningful Body Talk: Emotional Experiences with Music-Based Group Interactions. Tour. Manag. 2025, 106, 105008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barraclough, A.D.; Schultz, L.; Måren, I.E. Voices of Young Biosphere Stewards on the Strengths, Weaknesses, and Ways Forward for 74 UNESCO Biosphere Reserves across 83 Countries. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 68, 102273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, F.; Stephens, J.; Tiwari, R. Towards Psychosocial Well-Being in Historic Urban Landscapes: The Contribution of Cultural Memory. Urban Sci. 2020, 4, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çiftçi, Ş.F.; Çizel, B. Exploring Relations among Authentic Tourism Experience, Experience Quality, and Tourist Behaviours in Phygital Heritage with Experimental Design. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2024, 31, 100848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbe, S. Restoration of Multifunctional Cultural Landscapes: Merging Tradition and Innovation for a Sustainable Future; Landscape Series; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 30, ISBN 978-3-030-95571-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, P.-T.; Ho, M.-T.; Huang, M.-L. Understanding the Impact of Tourist Behavior Change on Travel Agencies in Developing Countries: Strategies for Enhancing the Tourist Experience. Acta Psychol. 2024, 249, 104463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochado, A.; Stoleriu, O.; Lupu, C. Wine Tourism: A Multisensory Experience. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 597–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muskat, B.; Hörtnagl, T.; Prayag, G.; Wagner, S. Perceived Quality, Authenticity, and Price in Tourists’ Dining Experiences: Testing Competing Models of Satisfaction and Behavioral Intentions. J. Vacat. Mark. 2019, 25, 480–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treude, M.; Schostok, D.; Reutter, O.; Fischedick, M. The Future of North Rhine-Westphalia-Participation of the Youth as Part of a Social Transformation towards Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, B.; Tsai, C.-H.K.; Su, C.-H.J.; Jantes, N.; Chen, M.-H.; Liu, J. Formation of a Tourist Destination Image: Co-Occurrence Analysis of Destination Promotion Videos. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2023, 27, 100763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H. Familiarity and Homogeneity Affect the Discrimination of a Song Dialect. Anim. Behav. 2024, 209, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shi, D.; Qi, X.; Liu, X.; Huang, Z. How Figurative Language Affects Officer Live Streaming Effectiveness: A Benign Violation Perspective. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 59, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S. The Advantages and Disadvantages of Using Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches and Methods in Language “Testing and Assessment” Research: A Literature Review. J. Educ. Learn. 2016, 6, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Kaushal, V. Perceived Brand Authenticity and Social Exclusion as Drivers of Psychological Brand Ownership. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | Construct Measures | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DP | Dialect Perceptions | Lu et al. (2019) [36] | |

| DU | DialectUnderstanding | ||

| 1 | DU1 | The dialect gives me a sense of the local history and culture. | |

| 2 | DU2 | The on-the-ground exposure to the dialect enables me to know more about it. | |

| 3 | DU3 | The pronunciation and intonation of the dialect is very unique. | |

| FU | Functionality | ||

| 4 | FU1 | The on-the-ground exposure to the dialect satisfies my curiosity about culture. | |

| 5 | FU2 | I want to pay for products with dialect elements. | |

| 6 | FU3 | The on-the-ground exposure to the dialect makes me excited. | |

| 7 | FU4 | It is worthwhile to be exposed to the dialect on this trip. | |

| CA | Captivation | ||

| 8 | CA1 | I am now captivated by the dialect. | |

| 9 | CA2 | The on-the-ground exposure to the dialect makes my trip fulfilling. | |

| 10 | CA3 | The dialect is fascinating. | |

| 11 | CA4 | I don’t mind when the locals speak the dialect. | |

| 12 | CA5 | I am OK with the tourism service provided in the dialect. | |

| 13 | CA6 | Communication is evident when I communicate with locals who speak. | |

| LC | LocalCharacteristics | ||

| 14 | LC1 | The local atmosphere created by the dialect is unique. | |

| 15 | LC2 | The dialect enables me to feel the local characteristics. | |

| 16 | LC3 | The dialect enables me to know the local characters of the local people. | |

| 17 | LC4 | The dialect enables me to feel the local culture. | |

| 18 | LC5 | The dialect well expresses the local characteristics. | |

| 19 | LC6 | The dialect is displayed in various ways. | |

| EP | ExclusivePerceptions | Wan et al. (2014) [104] | |

| 20 | EP1 | The use of dialect at that destination can ignore our feelings and perceptions. | |

| 21 | EP2 | The destination will not ask for our needs. | |

| 22 | EP3 | This destination doesn’t care about our suggestions. | |

| 23 | EP4 | The destination won’t take our advice. | |

| 24 | EP5 | The destination won’t consult with us. | |

| NE | NegativeEmotions | Kim et al. (2015) [103] | |

| 25 | NE1 | Bored. | |

| 26 | NE2 | Sleepy. | |

| 27 | NE3 | Irritated. | |

| 28 | NE4 | Angry. | |

| TCB | TouristCitizenshipBehaviors | Groth (2005) [67] | |

| TRB | Tourists’ Recommendations Behaviors | ||

| 29 | TRB1 | Recommend the destination to your family. | |

| 30 | TRB2 | Recommend the destination to your peers. | |

| 31 | TRB3 | Recommend this destination to anyone interested in it. | |

| 32 | TRB4 | Recommend this destination to my colleagues and others. | |

| TFB | Tourists’FeedbackBehaviors | ||

| 33 | TFB1 | Fill out a tourist satisfaction survey. | |

| 34 | TFB2 | Provide helpful feedback to the service staff. | |

| 35 | TFB3 | Provide information when surveyed by the business. | |

| 36 | TFB4 | Inform business about the excellent service received by an individual employee. |

| Variable | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 224 | 44.8 |

| Female | 276 | 55.2 | |

| Age | 20 to 25 | 143 | 28.6 |

| 26 to 30 | 162 | 32.4 | |

| 31 to 35 | 108 | 21.6 | |

| 36 to 39 | 87 | 17.4 | |

| Education | Below high school/secondary school | 27 | 5.4 |

| Junior college | 137 | 27.4 | |

| Undergraduate | 239 | 47.8 | |

| Postgraduate and above | 97 | 19.4 | |

| Occupation | Student | 128 | 25.6 |

| Civil servant | 61 | 12.2 | |

| Enterprise employee | 222 | 44.4 | |

| Freelancer | 32 | 6.4 | |

| Business owners | 56 | 11.2 | |

| Other | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Monthly income | CNY 0 to 3000 | 127 | 25.4 |

| CNY 3001 to 5000 | 75 | 15.0 | |

| CNY 5001 to 7000 | 90 | 18.0 | |

| CNY 7001 to 10,000 | 107 | 21.4 | |

| CNY 10,001 or more | 101 | 20.2 | |

| Number of visits | 1 | 275 | 55.0 |

| 2 | 149 | 29.8 | |

| Three or More | 76 | 15.2 | |

| Travel companion | None | 47 | 9.4 |

| Family | 215 | 43.0 | |

| Friends | 157 | 31.4 | |

| Fellow student | 10 | 2.0 | |

| Colleagues | 26 | 5.2 | |

| Tour group | 45 | 9.0 | |

| Total | 500 | 100.0 |

| Construct Measures | Items | Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DP | DU | DU1 | 0.906 | 0.927 | 0.936 | 0.610 |

| DU2 | 0.855 | |||||

| DU3 | 0.826 | |||||

| FU | FU1 | 0.914 | ||||

| FU2 | 0.804 | |||||

| FU3 | 0.813 | |||||

| FU4 | 0.819 | |||||

| CA | CA1 | 0.908 | ||||

| CA2 | 0.812 | |||||

| CA3 | 0.759 | |||||

| CA4 | 0.748 | |||||

| CA5 | 0.792 | |||||

| CA6 | 0.733 | |||||

| LC | LC1 | 0.931 | ||||

| LC2 | 0.818 | |||||

| LC3 | 0.798 | |||||

| LC4 | 0.752 | |||||

| LC5 | 0.775 | |||||

| LC6 | 0.795 | |||||

| EP | EP1 | 0.906 | 0.894 | 0.928 | 0.704 | |

| EP2 | 0.840 | |||||

| EP3 | 0.830 | |||||

| EP4 | 0.823 | |||||

| EP5 | 0.789 | |||||

| NE | NE1 | 0.937 | 0.897 | 0.922 | 0.765 | |

| NE2 | 0.860 | |||||

| NE3 | 0.846 | |||||

| NE4 | 0.852 | |||||

| TCB | TRB | TRB1 | 0.794 | 0.863 | 0.907 | 0.710 |

| TRB2 | 0.841 | |||||

| TRB3 | 0.802 | |||||

| TRB4 | 0.931 | |||||

| TFB | TFB1 | 0.912 | 0.863 | 0.908 | 0.712 | |

| TFB2 | 0.829 | |||||

| TFB3 | 0.809 | |||||

| TFB4 | 0.817 | |||||

| EP | NE | TRB | TFB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DP | 1.000 | 1.782 | 2.350 | 2.350 |

| EP | 1.782 | 1.818 | 1.818 | |

| NE | 1.794 | 1.794 |

| The Fornell–Larcker Criterion | HTMT Discriminant Validity | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DP | EP | NE | TRB | TFB | DP | EP | NE | TRB | TFB | |

| DP | 0.780 | |||||||||

| EP | −0.662 | 0.839 | 0.725 | |||||||

| NE | −0.657 | 0.515 | 0.874 | 0.715 | 0.571 | |||||

| TRB | 0.664 | −0.521 | −0.542 | 0.843 | 0.739 | 0.590 | 0.612 | |||

| TFB | 0.630 | −0.506 | −0.542 | 0.522 | 0.844 | 0.698 | 0.571 | 0.611 | 0.603 | |

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Path Coefficient | Hypothesis Testing |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | DP → TRB | 0.472 *** | Yes |

| H1b | DP → TFB | 0.410 *** | Yes |

| H2 | DP → EP | −0.662 *** | No |

| H3a | EP → TRB | −0.121 ** | Yes |

| H3b | EP → TFB | −0.129 ** | Yes |

| H4 | DP → NE | −0.563 *** | No |

| H5 | EP → NE | 0.142 *** | Yes |

| H6a | NE → TRB | −0.170 *** | Yes |

| H6b | NE → TFB | −0.206 *** | Yes |

| Effect | Mediation Path | Effect Value | Standard Error | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boost LLCI | Boost ULCI | ||||

| Indirect effect | DP → EP → TRB | 0.080 | 0.033 | 0.017 | 0.140 |

| DP → EP → TFB | 0.085 | 0.034 | 0.019 | 0.154 | |

| DP → NE → TRB | 0.096 | 0.027 | 0.043 | 0.154 | |

| DP → NE → TFB | 0.116 | 0.029 | 0.062 | 0.176 | |

| DP → EP → NE → TRB | 0.016 | 0.007 | 0.005 | 0.032 | |

| DP → EP → NE → TFB | 0.019 | 0.008 | 0.007 | 0.037 | |

| Direct effect | DP → TRB | 0.410 | 0.053 | 0.389 | 0.567 |

| DP → TFB | 0.472 | 0.047 | 0.306 | 0.508 | |

| Total effect | DP → TRB | 0.664 | 0.029 | 0.608 | 0.719 |

| DP → TFB | 0.630 | 0.033 | 0.564 | 0.690 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Geng, S.; Li, D. The Impact of Host–Guest Interactions Among Young People on Cultural Sustainability: A Case Study of Dialects. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310580

Geng S, Li D. The Impact of Host–Guest Interactions Among Young People on Cultural Sustainability: A Case Study of Dialects. Sustainability. 2024; 16(23):10580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310580

Chicago/Turabian StyleGeng, Songtao, and Danyang Li. 2024. "The Impact of Host–Guest Interactions Among Young People on Cultural Sustainability: A Case Study of Dialects" Sustainability 16, no. 23: 10580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310580

APA StyleGeng, S., & Li, D. (2024). The Impact of Host–Guest Interactions Among Young People on Cultural Sustainability: A Case Study of Dialects. Sustainability, 16(23), 10580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310580