Abstract

Decision-making within families considerably affects daily pro-environmental practices. While parental influence on children is known, the influence of children on environmental choices within families has yet to be thoroughly investigated, particularly in Asia. There are almost no reports regarding parent–child bidirectional transmissions in terms of environmental attitudes, psychological barriers, and pro-environmental behaviors (PEBs) in the Asian context. This study aimed to examine the parent–child bidirectional transmissions of environmental attitudes, psychological barriers, and PEBs in an Asian context, specifically in Japan and China. A total of 815 parent–child pairs (children ages 9–18) were recruited from Japan and China to participate in online questionnaire surveys. Regression analysis and structural equation modeling based on the actor–partner independence model revealed a bidirectional within-family socialization process of environmental attitudes, psychological barriers, and PEBs in the two countries. Children can transfer environmental knowledge and practices to their parents, which has been underestimated in the literature, particularly in Asia. Furthermore, our results suggest that Chinese children have more potential to act as catalysts in their family’s sustainable shift than Japanese children, given their substantial influence on family decision-making. The potential role of children in transmitting pro-environmental choices to their parents is also discussed.

1. Introduction

Children’s roles regarding environmental issues are complex and manifold. Children are not only future victims and game changers but also today’s contributors to climate change and environmental problems. Households with children consume significantly more energy than those without [1]. Existing research on climate change has mainly focused on parents’ influence on their children rather than the opposite. The scarcity of research on children’s influence on parents regarding climate change issues is primarily because of the difficulty in directly obtaining information from children on this topic. In addition, many scholars believe that parent-to-child influence accounts for most of the transmission of environmental behaviors and values. To date, very little is known about children’s role and influence in the family decision-making process or how it correlates with parents’ environmental attitudes and pro-environmental behaviors (PEBs), especially in the Asian context; children are undervalued as potentially powerful agents in promoting PEB.

A considerable amount of literature has been published on parent–child similarities in environmental attitudes and behaviors [2,3,4,5]. For example, significant and positive correlations were found between Danish parents and children, although with different strengths in terms of specific pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors [2]. Leppänen et al. (2012) found that fathers and daughters had the most significant relationship in environmental attitudes among Finnish families [5]. Casaló and Escario (2016) analyzed data from 16 countries and found positive associations between parents’ and children’s environmental concerns, especially for girls [6].

The most current literature attributes parent–child similarities to parental influence or power, especially from a developmental psychological aspect [7,8]. In the environmental domain, previous research provides evidence that parents are the primary socialization catalysts in conveying environmental attitudes, concerns, and behaviors [3,4,9,10,11]. Consistent with social learning theory, intergenerational flows have confirmed that children adopt socially desirable values by observing the behaviors of essential others, such as parents and older siblings [12]. Therefore, the family is the primary and most potent socialization agent throughout childhood and adolescence [5].

A growing body of literature has examined the reverse direction of children’s influence on family decision-making in recent decades. For example, children usually get what they want while shopping with parents through “pester power” [13,14]. Supermarkets can manipulate the placement of goods to encourage children to become advocates for healthier food choices [15]. In addition, studies show that parents tend to be receptive to the influence of adolescents in domains where adolescents are perceived as experts, such as Internet utilization [16]. Recently, researchers have sought to assess the impact children have on their parents in the environmental domain. To date, considerable evidence shows that children can transfer environmental education between generations [17,18]. Williams et al. (2016) reported that young children (ages 7–9) could spur flood education on their parents [19]. Legault and Pelletier (2000) found that parents expected more for local environmental conditions after their children completed a one-year environmental education program than a control group, indicating pro-environmental transmission from children to their parents [20]. In England, the two-year “Taking Home Action on Waste (THAW)” project carried out between 2005 and 2007 observed not only a substantial increase in primary children’s knowledge of waste and participation in recycling but also an immediate positive impact on other family members’ waste-related behaviors [21]. In the United States, middle school children with educational interventions designed to build climate change concerns among parents have been indirectly shown to have increased parents’ environmental concerns compared to the untreated group [22]. Most recently, Chinese children’s environmental knowledge was found to have a greater potential to influence their parents’ PEB than parents’ influence on their children [23]. Dillion (2002) claimed that children’s crucial role in adult development is undervalued and overlooked [24]. Currently, data collection methods concerning children’s influence rely on adults reporting the phenomenon on behalf of the children because of the difficulty of involving children in experimental studies. Previous research has also found that parents may not realize that their children are influencing them, highlighting the importance of obtaining data directly from children to guarantee the accuracy of investigations [17].

Children have several advantages as changing agents of PEB. First, it is relatively more straightforward to regularly provide formal environmental education to children than to adults [18]. Second, children can better receive and digest scientific facts, avoiding the negative influence of political ideologies and worldviews on sensitive topics compared to adults [25,26]. Third, children are more trustworthy than other unfamiliar sources to their parents, which makes the information-conveying process more effective [25]. Fourth, the birth rate is declining continuously in many countries, including East Asian countries, such as Japan and China, making children more powerful both in families and in the public than before, as society increasingly cherishes them.

While the awareness of the climate crisis is increasing, many still fail to adopt environmentally friendly behaviors. Research has suggested that the gap between awareness and action can be attributed to structural and psychological barriers. Structural barriers, such as insufficient infrastructure, limited access to sustainable products, financial limitations, and policy restrictions, are external factors that hinder pro-environmental actions [27,28]. In contrast, psychological barriers are internal obstacles that limit individuals’ engagement in sustainable behaviors [29]. Unlike structural barriers, which can be addressed through policies and technology, psychological barriers are often intertwined with emotional and cognitive responses. Therefore, they are more personal and difficult to identify and overcome. Psychological barriers vary among individuals and are influenced by personal values, beliefs, experiences, and social contexts. Previous studies have identified considerable psychological barriers from various perspectives. Lacroix et al. (2019) [30], drawing from earlier work [29,31], introduced the 22-item Dragons of Inaction Psychological Barriers (DIPB) scale, which measures barriers across five dimensions: unnecessary change, conflicting goals and aspirations, interpersonal relations, lack of knowledge, and tokenism.

Psychological barriers may influence parents and children differently because of generational differences, developmental stages, and social roles. Parents struggling with existing demands and taking care of their offspring often prioritize convenience and cost savings over environmental concerns. Carrus et al. (2008) suggested that past behaviors and negatively anticipated emotions hinder adults’ PEBs [32]. By contrast, children, who face fewer time constraints and financial obligations than their parents, are still heavily influenced by social factors in their environmental actions [33]. Collado et al. (2017) also found a stronger “best friends effect” in older children concerning environmentalism, while younger ones were more influenced by their parents [10].

Children’s influence and parent–child interactions in terms of environmental attitudes, psychological barriers, and PEBs in the Asian context have not been thoroughly investigated to date. Understanding child-to-parent intergenerational transmission could offer a potential avenue for children to connect with older generations as game-changers and hold significant importance across different cultural backgrounds.

2. Objectives and Hypotheses

2.1. Objectives

This study had two objectives: to examine intergenerational transmission between parents and children concerning environmental attitudes, psychological barriers, and PEBs and to compare the parent–child dyads in an East Asian context for their similarities and discontinuities between generations.

In this study, we focused on two countries: Japan and China. These two countries are significant contributors to regional and global economies, as well as to greenhouse gas emissions and climate change issues. Despite their different timelines and approaches, both countries are dedicated to balancing economic development and environmental conservation. Their approaches to environmental education reflect these priorities and are shaped by their unique cultural and policy contexts. In Japan, for example, programs in Shiga Prefecture, such as the Lake Biwa Floating School, forest-based experiential learning, and the Rice Paddies Project, engage elementary school students in hands-on activities that cultivate a deep connection to nature and promote ecological awareness [34]. These initiatives highlight Japan’s emphasis on immersive and place-based education. Meanwhile, in China, the integration of multimedia and web-based technologies into environmental education aims to increase student engagement and overcome the limitations of traditional teaching methods [35]. Curriculum reforms driven by environmental policies further emphasize the link between education and sustainable development, with higher educational attainment correlating with stronger pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors [36]. Together, these approaches demonstrate the dynamic strategies employed by both nations to foster environmental consciousness and action.

The parent–child relationship in the two countries is deeply rooted in Confucianism and is influenced by considerable modernization and Westernization. Both countries have experienced declining fertility rates since the 1970s: 1.3 births/woman for Japan and 1.2 births/woman for China in 2022 [37]. The historical change in the birth rate is sharp, particularly in China (i.e., 6.1 births/woman in 1970). This is primarily because of the one-child policy, a population planning initiative restricting families to a single child, implemented during the late 1980s and the mid-2010s to control overpopulation in the country. This policy significantly altered the country’s demographic landscape, family structure, and parenting styles [38]. Meanwhile, vast territory, diverse ethnicities and cultures, and imbalanced regional economic development contribute to diversity in parents’ values and socialization goals in child rearing [39,40].

2.2. Hypotheses

Combining our literature review with the similar yet considerably unique social situations in Japan and China, we assumed that fundamental parent–child relationships in pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors would be consistent across countries. However, some associations may be more salient in China. Given the changes in family structure introduced by the one-child policy, Chinese families might display closer parent–child bonds and greater influence from their children than Japanese families. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1:

Parents and children are associated on their respective psychological and behavioral characteristics.

H1a:

Parents’ environmental attitudes are positively related to their children’s environmental attitudes.

H1b:

Parents’ psychological barriers are positively related to their children’s psychological barriers.

H1c:

Parents’ PEBs are positively related to their children’s PEBs.

H2:

Parents’ and children’s PEBs can be explained by each other’s PEB indicators.

H3:

Chinese children exert a more decisive influence on the family decision-making process than Japanese children do.

H4:

The correlations of PEB indicators between parents and children are more robust in China than in Japan.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants, Sample, and Data Collection

The participants for this study were children and any one of their parents from the Tokyo Metropolitan Area (Japan, November 2020) and Shanghai (China, March 2021). Recruitment and survey participation were conducted online. The participants were recruited from local survey companies. All child participants met the following criteria: (1) between fourth grade in elementary school and third (final) grade in senior high school, equivalent to ages 9–18; (2) the youngest child in the family; (3) a native speaker of the official language of the country (Japanese or Chinese); and (4) living with the parent who responded to the questionnaire at the time of the survey. The parent participants were native speakers of the official language in the surveyed country who lived with a child who responded to the questionnaire.

The online survey was answered by each pair of parent and child separately but sequentially using a single device prepared by the parent. Parents read the instructions regarding this parent–child dyad survey and gave consent to participate in the survey by responding to the screening questions. Qualified respondents handed over their online devices to their children, which was considered parental consent for them to participate in the survey. Once the children completed their designated part, they were asked to return the device to their consenting parents to continue answering the parents’ part of the questionnaire. Approximately 50 parent–child pairs from each grade were recruited from each country. In Japan, 450 pairs of responses were collected, of which 363 were used for the analysis. In China, data from 455 pairs were obtained, and usable data comprised 452 pairs. The final sample consisted of 815 children (aged 9–18) matched with one of their parents. Table 1 presents the individual, family, and socio-economic attributes of the dataset. The Chinese dyad respondents lived in families with fewer heads, predominantly with a single child and younger parents, compared to the Japanese sample. Pairs were represented more by males in the Japanese sample, whereas the opposite was true for the Chinese pairs.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents by country.

3.2. Measurements

The questionnaire was designed to measure the following constructs: children’s influence on the family decision-making process, environmental attitudes, psychological barriers, and daily pro-environmental practices of parents and children. The original questionnaire was developed in English and translated into Japanese and Chinese by native speakers fluent in both English and the respective target languages. To ensure cultural appropriateness and linguistic accuracy, the translations were reviewed and revised by a group of native speakers with expertise in environmental psychology and survey design. For the children’s survey, special attention was given to using simple and age-appropriate language to ensure clarity and comprehension for the target age group (9–18 years).

3.2.1. Children’s Influence

Children’s influence on family decision-making was measured for seven environmental domains, namely food, purchases, transportation, travel, energy saving, waste reduction, and recycling, using a four-point Likert scale (1: Very much to 4: Not at all). These domains were selected as a common and comprehensive range of PEBs largely based on Lacroix et al. (2019) [30], which examined psychological barriers to PEBs. Decisions on daily leisure travel destinations were added to measure children’s influence, as it is one of the areas where children could have more power in family planning and can have significant environmental impacts depending on the type and distance of the destination [14,15,21,41,42]. Responses were calculated separately for each domain or as a mean score of seven. The scores were reversed, with higher scores indicating stronger family influence. Both children and parents were asked to answer this question.

3.2.2. Environmental Practice in Daily Life

Six domains (eating less meat, using public transportation, putting on more clothes rather than turning up the heat (moderate heating), reducing water use, making eco-friendly purchases, and recycling), based on the previous literature [30,43], were chosen to evaluate daily PEB. Both parents and children were asked this question, which was answered using a five-point Likert scale (1: Never to 5: Always, whenever possible). The responses were calculated separately for each domain, or a mean of six. Higher scores indicate greater engagement in PEBs.

3.2.3. Perceived Child’s/Parent’s Environmental Concerns, Knowledge, and Practices

For perceived environmental concern, participants were asked to indicate how much their parent or child participating in this survey was concerned about the environment using a five-point Likert scale (1: Not at all to 5: Very much). A single question, rather than a multidimensional scale, was used to gauge perceptions of concern, acknowledging that describing others’ characteristics is more challenging than describing one’s own. A similar question was asked regarding perceived environmental knowledge. Perceptions of parents’ (both fathers and mothers) and children’s environmental practices were collected by having each pair report the frequency of the same six behaviors as in the self-reports. Participants then rated how much they believed their pair mates expected them to practice PEBs (1: Not at all to 5: Very much). The responses were used separately for each domain, or as the mean of six. Using the Likert scale, higher scores indicate more favorable perceived environmental attitudes, behaviors, and expectations from the pair mate.

3.2.4. Environmental Attitude

The New Ecological Paradigm (NEP) scale [44] measures attitudes and beliefs about environmental issues, natural conservation, and human–nature relationships. NEP is one of the most widely used scales to measure general environmental attitude [45,46,47]. A 15-item version [44] was used as the parents’ questionnaire. The NEP for Children [48], a 10-item scale adapted specifically for children from the original scale, was used in the children’s questionnaire. In both questionnaires, respondents rated their agreement on a five-point Likert scale (1: Strongly disagree to 5: Strongly agree). The scores for a few of the items were reversed for consistent computation. Responses were averaged across items. Higher scores indicate more ecologically conscious attitudes and beliefs.

3.2.5. Environmental Concerns

The environmental concern index (ECI) [6], which includes six topics (air pollution, energy shortage, extinction of plants and animals, clearing of forests for other land use, water shortages, and nuclear waste), was adopted to investigate the environmental concerns of both parents and children. Both parent and child respondents were asked to rate their concerns with each environmental topic using a four-point Likert scale (1: This is not a serious concern to anyone to 4: This is a serious concern for me personally as well as others). Responses were calculated as a mean score of six. A higher mean score typically indicates a greater level of concern for or awareness of environmental issues.

3.2.6. Readiness to Change

Referring to individuals’ willingness and preparedness to make behavioral changes for the environment, “readiness to change” questions asked the respondents to describe the stages they go through when addressing PEBs [49]. As a key component of the transtheoretical model framework [50], readiness to change presents five stages: pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance. Understanding the stages of readiness helps develop effective strategies through tailored interventions to maximize the likelihood of success in adopting and maintaining PEBs [51,52]. Furthermore, it is essential to judge which family member subgroup—parents or children—is ahead in making and maintaining pro-environmental practices, potentially leading the family change in reducing environmental impacts.

3.2.7. Psychological Barriers

The 22-item DIPB scale by Lacroix et al. (2019) [30] was used to identify the underlying obstacles that hinder people’s willingness to implement PEBs, such as conflicting goals and aspirations, lack of knowledge, and interpersonal relations [53,54,55,56]. The DIPB score indicates an increased level of resistance or reluctance to engage in behaviors that mitigate climate change. DIPB is negatively associated with pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors [57]. Both parent and child respondents rated their agreement with each scale statement using a seven-point Likert scale regarding a certain behavior in six daily scenarios that they considered the most difficult to achieve: eating less meat, taking public transportation, putting on more clothes rather than turning up the heat (moderate heating), reducing water use, making eco-friendly purchases, and recycling.

3.3. Analysis

Data analyses to test the hypotheses were conducted in four steps using Stata 17.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA). First, paired and unpaired t-tests were conducted on each analyzed variable to test for differences between parents and children in Japan and China (testing H3). Second, Pearson’s correlation analysis was conducted to assess the strength of the associations between parent’s and children’s environmental attitudes and behaviors (H1 and H4). Third, multiple regression analysis was performed to identify significant predictors of parents’ and children’s PEBs in each country (H2). A hierarchical regression approach was employed to examine the predictability of parent- and child-related independent variables. For example, to predict parents’ PEBs, four models were assumed: parent-related (self-reported) and household variables (Model 1); parent-related and household variables and parents’ perceptions of the child (Model 2); parent-related and household variables and child-related variables (Model 3); and all concerning variables (Model 4). Hierarchical regression analyses were conducted for children’s PEBs in a similar manner. Furthermore, regression analyses were performed based on the child’s gender for each country, considering potential gender differences in parent–child relationships.

Parent–child interrelationships were examined using the actor–partner independence model (APIM), a statistical framework that analyzes dyadic relationships between two individuals (H2) [58]. The APIM not only captures the influences of the two individuals’ behaviors on their own outcomes (i.e., actor effect) but also their influences on each other (i.e., partner effect). Commonly used in studies involving family members, romantic partners, and other paired data (e.g., friends), the APIM demonstrates reciprocal effects [58,59]. In the present study, we (1) employed APIM to measure the influence of parents and children on each other in the process of reaching PEBs and (2) integrated environmental attitude and behavior variables (environmental concerns, readiness to change, psychological barriers, and PEBs) together with APIM into Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) based on the Theory of Planned Behavior [60] and Value-Belief-Norm theory [61]. We assumed that PEBs are initially triggered by environmental concerns that nurture attitudinal preparedness for behavioral changes but could be discouraged by psychological barriers through cross-influences between the pairs. This approach provides a comprehensive understanding of parent–child dynamics in the PEB decision-making process.

4. Results

4.1. t-Tests

4.1.1. Paired t-Tests by Parents and Children

A series of paired-sample t-tests were conducted to compare environmental attitudes and behaviors between parents and their children in the two countries (Table 2). Japanese parents reported significantly less favorable attitude (NEP, 3.42 vs. 3.49, t = −3.31(362), p = 0.001), more serious environmental concern (ECI, 3.35 vs. 3.22, t = 3.11(362), p = 0.002), stronger intentions (readiness to change, 3.29 vs. 2.82, t = 7.84(362), p < 0.001), and smaller psychological barriers (DIPB, 3.34 vs. 3.50, t = −3.83(362), p < 0.001), compared with their children. Meanwhile, parents (M = 2.96, SD = 0.71) seemed to be more engaged in PEBs than the younger generation (M = 2.54, SD = 0.75) at the aggregate level, t = 10.82(362), p < 0.001. Similar patterns were also found for each PEB, namely, less meat (2.17 vs. 1.93, t = 4.49(362), p < 0.001), green transportation (2.85 vs. 2.69, t = 2.34(362), p = 0.020), energy saving (heating, 3.29 vs. 2.74, t = 9.49(362), p < 0.001; water use, 3.22 vs. 2.56, t = 10.56(362), p < 0.001), eco purchase (2.73 vs. 2.28, t = 8.32(362), p < 0.001) and recycling (3.53 vs. 3.02, t = 8.26(362), p < 0.001). In the Chinese pair sample, parents demonstrated lower attitude (NEP, 3.66 vs. 3.72, t = −3.68(451), p < 0.001), less serious concern (ECI, 3.63 vs. 3.70, t = −5.75(451), p < 0.001), performed better in eating less meat (2.70 vs. 1.90, t = 16.44(451), p < 0.001), and eco-purchases (3.19 vs. 2.88, t = 7.17(451), p < 0.001) than their children. In contrast, Chinese children reported higher behavioral scores in green transportation (3.53 vs. 3.10, t = 9.73 (451), p < 0.001), energy saving (heating, 3.31 vs. 3.12, t = 4.39(451), p < 0.001; water use, 3.30 vs. 3.17, t = 2.91(451), p < 0.001), and recycling (3.96 vs. 3.78, t = 4.01(451), p < 0.001) than their parents. There were no significant differences in readiness to change or psychological barriers between Chinese parents and their children.

Table 2.

Paired t-tests on environmental attitudes, psychological barriers, and PEBs between parents and children.

4.1.2. Unpaired t-Tests on Children and Parents by Country

Table 3 presents the independent sample t-test results for the same family member status—parent or child—between Japan and China. Chinese parents expressed more favorable attitudes, lower psychological barriers, and conducted more PEBs than Japanese parents, except for reducing water use (3.22 vs. 3.17, t = 0.69(813), p = 0.493). Similarly, Chinese children displayed “greener” attitudes, both in mindsets and behaviors, than Japanese children, except for meat consumption (1.93 vs. 1.90, t = 0.42(813), p = 0.673). Children’s influence in the family, as perceived by children and parents, was significantly higher in China than in Japan across all domains of environmental decision-making, as well as in the total average.

Table 3.

Unpaired t-tests on environmental attitudes, psychological barriers, PEBs, and children’s family influence by country.

4.1.3. Unpaired t-Tests by One-Child and Multiple-Child Families

Independent sample t-tests were performed to investigate the possible influence of the number of children in the family (Table 4). In Japanese multiple-child families, parents reported more energy saving (heating, 3.39 vs. 3.09, t = 2.68(361), p = 0.008; water use, 3.31 vs. 3.04, t = 2.35(361), p = 0.019), and more eco-purchases (2.81 vs. 2.57, t = 2.11(361), p = 0.035), along with children reporting more frugal water use (2.64 vs. 2.40, t = 2.08(361), p = 0.039). No significant difference was found in the children’s influence, either perceived by themselves or by their parents. In Chinese families, parents with more than one child had higher NEP (3.86 vs. 3.65, t = 3.11(450), p = 0.002), concern (3.83 vs. 3.61, t = 4.16(450), p < 0.001), lower psychological barriers (2.20 vs. 2.59, t = −3.87(450), p < 0.001), more moderate heating (3.71 vs. 3.08, t = 3.21(450), p = 0.001), and stronger perception of the child’s influence on recycling (3.45 vs. 3.11, t = 2.24(450), p = 0.026). Chinese children who had siblings reported higher NEP (3.85 vs. 3.72, t = 2.00(450), p = 0.046), concern (3.84 vs. 3.69, t = 3.49(450), p = 0.001), lower psychological barriers (2.37 vs. 2.60, t = −2.70(450), p = 0.010), and more influence on family transportation choice, as perceived by themselves (3.06 vs. 2.64, t = 2.80(450), p = 0.005) and their parents (3.52 vs. 3.16, t = 2.99(450), p = 0.005).

Table 4.

Unpaired t-tests on environmental attitudes, psychological barriers, PEBs, and children’s family influence by a number of children in the family.

4.2. Correlation

The results of the correlation analysis are presented in Table 5 (Japan) and Table 6 (China). Positive correlations were found between parents and children for NEP, ECI, readiness to change, DIPB, and PEBs in moderate (>0.3) to strong (>0.5) degrees for both samples. Furthermore, specific corresponding behaviors of parents and children were positively correlated in the moderate ranges (0.3 < r < 0.5 in Japan and 0.3 < r < 0.6 in China). Among them, eco-purchase behavior (r (361) = 0.476, p < 0.001) and heating behavior (r (450) = 0.597, p < 0.001) were highly correlated in Japan and China, respectively.

Table 5.

Correlation coefficients of analyzed variables in Japan.

Table 6.

Correlation coefficients of analyzed variables in China.

4.3. Multiple Linear Regression

Table 7 presents the hierarchical regression results for parents’ PEBs. The variance inflation factors (VIFs) were within the acceptable range (< 5) in all models, indicating no serious multicollinearity issues. In both countries, Model 4 yielded the largest R2 values, suggesting a greater predictive power of the full set of independent variables assumed in this study for parent’s PEBs. In Model 4 of the Japanese sample (F19,343 = 16.34, Adj R2 = 0.446), the parent’s education (β = 0.087, p = 0.036), environmental concern (β = 0.103, p = 0.043), readiness to change (β = 0.285, p < 0.001), and perception of their child’s PEB (β = 0.447, p < 0.001) were found to predict more engagement in PEBs among parents, while children’s readiness to change (β = −0.138, p = 0.019) was found to be negatively related to their parents’ PEBs. In China’s Model 4 (F19,432 = 25.40, Adj R2 = 0.507), being female (β = −0.104, p = 0.003), readiness to change (β = 0.080, p = 0.044), children’s influence perceived by parents (β = 0.079, p = 0.043), children’s PEBs perceived by parents (β = 0.390, p < 0.001), and children’s self-reported PEBs (β = 0.203, p = 0.002) were found to be positively related to parents’ PEBs.

Table 7.

Hierarchical regression on parents’ PEB.

Concerning the analyses of children’s PEBs, a quadratic square term of grade (grade2) was added to the regression models because of a nonlinear trend between children’s PEBs and their grades in both countries. The VIFs were below 10 in all regression models, except for Model 1, for both datasets, which is acceptable considering the considerably high VIFs for the two grade variables due to their nature of considerable multicollinearity (50–60). Table 8 summarizes the regression results for the children’s PEBs. Similar to the parent analyses, Model 4 (full model) yielded the largest R2 values, indicating that it was the best model. In this model, the Japanese children’s PEBs (F21,341 = 15.33, Adj R2 = 0.454) were predicted by their readiness to change (β = 0.280, p < 0.001), influence (β = 0.099, p = 0.020), the parents’ expectation perceived by their children (β = 0.119, p = 0.022), and PEBs by the mother (β = 0.170, p = 0.002) and the father (β = 0.220, p < 0.001) perceived by their child. The child’s grade was not significant in either the linear or quadratic functions. In China (F21,430 = 38.43, Adj R2 = 0.635), the child’s grade was significant in linear (β = −0.539, p = 0.010) and quadratic (β = 0.598, p = 0.004) functions. Readiness to change (β = 0.256, p < 0.001), parents’ expectation perceived by the children (β = 0.119, p = 0.005), and the fathers’ PEB perceived by the children (β = 0.509, p < 0.001) were found to be positive predictors.

Table 8.

Hierarchical regression on children’s PEB.

Table 9 presents the analysis results by gender and country based on Model 4. The child’s readiness to change and the father’s PEBs as perceived by the child were positive predictors in all regression results, while the mother’s PEBs was found to be positive only among Japanese boys (β = 0.209, p = 0.006). Parents’ expectation of their child’s PEBs was found to be a positive predictor among Japanese girls (β = 0.218, p = 0.007) and Chinese boys (β = 0.195, p = 0.002). Parents’ readiness to change (β = −0.250, p = 0.003) and PEBs (β = 0.221, p = 0.011), both self-reported by parents, were significant among Japanese girls. The grade-squared term was significant only among Chinese girls, and none for the linear grade variable.

Table 9.

Regression on children’s PEB by gender group based on Model 4.

4.4. APIM-SEM

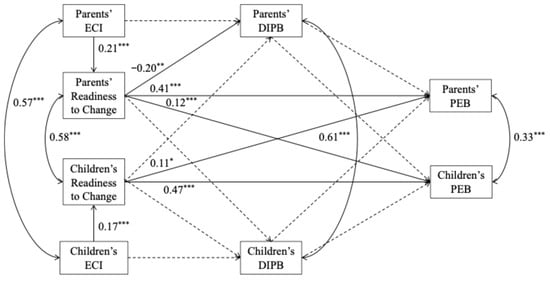

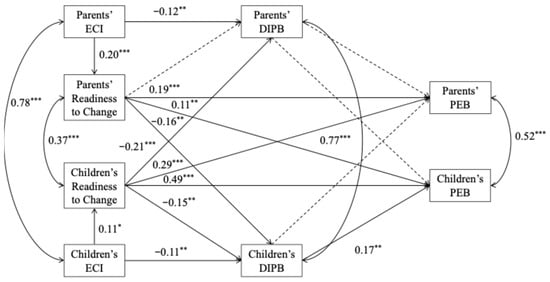

Figure 1 illustrates the relationships between Japanese parent–child dyads in environmental attitudes, psychological barriers, and PEBs using the SEM method integrated with APIM. The analysis yielded a good fit to the model (RMSEA = 0.064, CFI = 0.982). For both parents and children, the actor effects of readiness to change to their own PEB were significantly positive with similar strengths (βparents = 0.409, p < 0.001; βchildren = 0.470, p < 0.001). Furthermore, the partner effects of parents and children on readiness to change to PEB were positive (βparents-children = 0.116, p = 0.037; βchildren-parents = 0.114, p = 0.046), with slightly larger coefficients from parents to children. DIPB psychological barriers were not significant for PEBs, either as actor or partner effects. Figure 2 presents the APIM results for the Chinese parent–child dyads. The model fit indices were acceptable (RMSEA = 0.074, CFI = 0.981). Similar to the Japanese dyads, the actor effects of readiness to change on their own PEB were significant and positive (βparents = 0.187, p < 0.001; βchildren = 0.486, p < 0.001). The actor effect of children was stronger than that of parents. With regard to the partner effects, children had a stronger influence on parents from readiness to change to PEB (βchildren-parents = 0.286, p < 0.001) compared to the parents’ influence on children (βparents-children = 0.110, p = 0.008). Moreover, the partner effects of readiness to change to DIPB were significant and negative in both relationships (βparents-children = −0.159, p = 0.001; βchildren-parents = −0.206, p < 0.001). Children’s DIPB was found significant and positive toward their PEB (βDIPB-PEB = −0.168, p = 0.006), while parent’s DIPB was not.

Figure 1.

APIM-SEM results on Japanese parent–child relationships on environmental attitude, psychological barriers, and PEB. Note. N = 363. χ2(8) = 19.73, p = 0.011, RMSEA = 0.064, CFI = 0.982, SRMR = 0.045. Significant at * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. Solid and dotted lines indicate significant and insignificant paths, respectively.

Figure 2.

APIM-SEM results on Chinese parent–child relationships on environmental attitude, psychological barriers, and PEB. Note. N = 452. χ2(8) = 27.57, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.074, CFI = 0.981, SRMR = 0.053. Significant at * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. Solid and dotted lines indicate significant and insignificant paths, respectively.

5. Discussion

This study investigated the intergenerational transmission of environmental attitudes, psychological barriers, and PEBs using online questionnaire data from Japanese and Chinese families. As expected, we found significant positive correlations between the corresponding environmental attitudes, psychological barriers, and behaviors of parents and children in both countries, supporting H1(a, b, and c). Our study provides evidence of intergenerational consistencies in environmental attitudes, psychological barriers, and PEBs in Asian families. The findings are consistent with previous studies and add evidence to support the social learning theory [2,11,12,62,63]. Glass et al. (1986) argue that similarities may arise from the shared experiences that parents and their children have undergone, particularly those that shape attitudes [64]. Additionally, Grønhøj and Thoegersen (2012) attribute this parent–child consistency to their “identical socio-economic positions and physical locations” [3]. These arguments also apply to the Asian dyad samples.

The regression and APIM-SEM results suggest that PEBs by parents and children cannot be fully, but at least partially, predicted by partners’ attitudes, expectations, and behaviors (H2 supported). The regression results revealed that children’s own intentions (readiness to change), parents’ PEBs, and expectations perceived by children explained their PEBs in Japan and China. Supported by social learning theory, children’s perception of parents’ PEBs can function as descriptive norms within families and has great potential to encourage adolescents’ PEBs [3,12]. These results suggest that parents play a critical role in cultivating PEBs in the next generation, confirming the transmission from parents to children as part of the socialization process. Similarly, parents’ PEBs can be enhanced by children’s PEB (perceived or self-reported). This finding supports the reverse socialization process in which children can serve as catalysts and engage their parents in PEBs [17,41,65,66].

The SEM results also confirmed the associations between parents and children at two levels in both countries: (1) parents’ or children’s indicators predicting their own PEBs, and (2) interrelationships between parents and children. At the first level, individuals with stronger concerns, regardless of whether they are parents or children, are more likely to show stronger intentions and eventually engage more in PEBs. The results confirm the predictive power of readiness to change, serving as a PEB intention, as suggested by the Theory of Planned Behavior [49,60]. DIPB psychological barriers were not significant for either actor or partner effects but were only significant in Chinese children. This may be explained by two factors: (1) compared to the older generation in China (parents), the recently enhanced environmental education has better equipped the younger generation (children) to connect key psychological stages related to PEBs, advancing their decision-making processes, and (2) the unequal economic development between the two countries contributes to differences in structural and psychological barriers. In China, substantial structural barriers, such as inconsistent policy enforcement and underdeveloped techno-social systems, disrupt the link between environmental attitudes and behaviors [27,67]. These barriers increase both the physical and psychological efforts to engage in PEBs, with children likely facing mental struggles about whether to act, making DIPB a hindrance. By contrast, Japan’s long-standing environmental conservation efforts and legislation may have fostered well-established public awareness, social norms, and pro-environmental habits, resulting in psychological barriers that play a less significant role. On the second level, actor and partner effects between readiness to change and PEBs were found in parent–child dyads. These findings, along with those from the regressions, support H1 and H2 regarding intergenerational transmission in encouraging PEBs to mitigate climate change.

Attitudinal and behavioral differences have been detected between parents and children in Japan. The paired t-tests revealed that the older group is “greener”. These results are in line with previous findings that children hold weaker environmental attitudes, concerns, and pro-environmental performance compared with their parents [2,6,68,69]. In contrast, the results were mixed in Chinese families: children reported more PEBs than their parents. Considering China’s relatively short environmental conservation history, current children benefit more from environmental education in school curricula, which may not have been available or well-designed during their parents’ schooling. These findings are encouraging as they reveal children’s ability to acquire up-to-date environmental knowledge and skills through formal school education accessible for all and other channels such as friends and communities.

A series of correlation analyses and t-tests in this study imply that Chinese children act as powerful influencers in family decision-making compared to Japanese children (supporting H3). The “powerful children” in China are likely social products of the one-child policy [70]. This means that nurturing children as change agents can effectively accelerate sustainable shifts at the household level. Correlation analyses yielded mixed results for the degree of parent–child ties in the two countries (partially supporting H4). Chinese dyads exhibited stronger connections in PEBs (transportation, heating, and water use), concerns, and psychological barriers, but not in others, such as NEP and readiness to change, compared with the Japanese pairs. This inconsistency may be attributed to the varying predictive powers of these measurements in two different cultural contexts. Additionally, the paired t-tests results (Table 2) indicate that Chinese children engage more in transportation, heating, and water-use behaviors than their parents. This suggests that Chinese children may influence their parents’ PEBs in these areas, offering further evidence of a reverse socialization process within families. According to t-tests by country, both Chinese parents and children expressed more environmentally friendly attitudes, lower psychological barriers, and scored higher on most PEBs than Japanese respondents. However, this difference should be interpreted with caution. Scholars have found significant cultural effects on response styles, more specifically, on rating scales [71,72]. Studies show that, compared to Western respondents, both Japanese and Chinese respondents are more likely to avoid extremely positive answers and tend to respond neutrally. Moreover, this tendency was more salient among Japanese respondents than among Chinese ones [73].

The regression results by child’s gender suggest that gender differences exist in intergenerational transmission and vary across cultures. Fathers from both countries in our samples were observed to substantially influence children’s PEBs compared to mothers. While both Asian mothers and fathers endorse Confucian values that emphasize family structures and respect for authority, mothers are generally more influential on children; however, fathers tend to contribute more to children’s achievements [74,75]. The complex gender-specific transmission of PEBs requires further research.

The findings of this study provide valuable insights into the intergenerational transmission of PEBs within families in Japan and China. However, these results must be interpreted considering significant macro-level differences between the two countries, including their environmental policy histories, economic development trajectories, and social structures, which likely influence family dynamics around environmental attitudes and behaviors. Japan’s environmental trajectory, characterized by a post-war focus on waste management, evolved into comprehensive recycling laws and sustainable resource management strategies by the 1990s, fostering a culture of environmental responsibility within families [76]. China, on the other hand, has transitioned from reactive environmental policies in the late 20th century to proactive green growth strategies, including sustainable education and governance reforms, which emphasize international cooperation and learner-driven sustainability practices [77,78]. Japan’s longer history of stable environmental policies and social norms emphasizing harmony with nature may have facilitated deeper intergenerational transmission of environmental attitudes and behaviors. This occurred despite Japanese children having a relatively weaker influence in family decision-making compared to Chinese children, which may explain why H4 is only partially supported. In contrast, China’s recent but rapid adoption of environmental policies and education programs equips children with strong environmental knowledge and behaviors, positioning them as key agents of change in influencing older generations. These macro-level differences underscore the importance of understanding how societal and cultural contexts shape micro-level variations in family dynamics, particularly the mutual influence between parents and children in PEB transmission.

The current study has some limitations. First, our data were collected in November 2020 (Japan) and March 2021 (China) when the world was struggling with the COVID-19 pandemic. The influence of physical conditions and emotions on environmental decision-making remains unknown. Second, the study employed cross-sectional data, which limited the ability to establish definitive causality in the intergenerational transmission. In-person interventions were not feasible during the pandemic due to limited access to families, particularly children, under strict precautionary measures. To address this, future research could employ experimental interventions to rigorously examine the causal effects. Also, a short-term, diary-based longitudinal approach might offer more nuanced insights into the daily fluctuations of environmental attitudes and behaviors within the family [79]. These two methods would provide a deeper understanding of the bidirectional influences on PEBs, ultimately offering a more comprehensive view of intergenerational transmission in family settings. Third, the unbalanced gender composition of the parent samples may have induced bias in interpreting parent–child dynamics. Since parental influence on children’s environmental attitudes and behaviors may vary by parent gender, future research should use a more balanced sample to enhance the generalizability of the findings. Another limitation of this study is the potential influence of translation and cultural response biases. Although the survey questions were carefully translated into Japanese and Chinese, subtle differences in interpretation may still exist, which could affect how respondents understood and answered the questions. Finally, previous studies have suggested that parenting styles and gender differences influence intergenerational transmission [5,22,66,80]. Further research on parenting styles, gender combinations in dyads, and cultural differences in sustainable family choices is required.

6. Conclusions

This study confirmed the bidirectional socialization process in terms of environmental attitudes, psychological barriers, and daily pro-environmental practices within families in Japan and China. Our findings suggest that children can transfer environmental knowledge and practices to their parents. The role of children in navigating their families toward sustainable choices is undervalued, particularly in Asia. Therefore, school-based environmental education should aim to foster awareness of the problems, evidence-based knowledge, and pro-environmental attitudes in children from their early developmental stages, encouraging sustainable practices that can extend to family members. By empowering children with environmental values, schools can facilitate a “reverse influence,” enabling children to become agents of change and promote PEBs at home. Integrating these insights into educational strategies would create a ripple effect of sustainable behaviors, thus effectively bridging the gap between school-based education and family-based PEBs among a larger population. Our findings on intergenerational transmission in environmental attitudes and behaviors and on children’s potential as game changers can help in better and more effective design and implementation of environmental and educational policies and campaigns.

Author Contributions

X.L.: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft, visualization; N.K.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, resources, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition, supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by JSPS KAKENHI Grant No. 20K12278 and 23K28288.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Systems and Information Engineering, the University of Tsukuba (2020R404, 29 September 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all respondents involved in the study. The informed consent for children was obtained from legal guardians in accordance with the laws/regulations in the studied countries.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wallis, H.; Nachreiner, M.; Matthies, E. Adolescents and electricity consumption; investigating sociodemographic, economic, and behavioural influences on electricity consumption in households. Energy Policy 2016, 94, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grønhøj, A.; Thøgersen, J. Like father, like son? Intergenerational transmission of values, attitudes, and behaviours in the environmental domain. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grønhøj, A.; Thøgersen, J. Action speaks louder than words: The effect of personal attitudes and family norms on adolescents’ pro-environmental behaviour. J. Econ. Psychol. 2012, 33, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guastello, D.D.; Peissig, R.M. Authoritarianism, environmentalism, and cynicism of college students and their parents. J. Res. Personal. 1998, 32, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppänen, J.M.; Haahla, A.E.; Lensu, A.M.; Kuitunen, M.T. Parent-child similarity in environmental attitudes: A pairwise comparison. J. Environ. Educ. 2012, 43, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L.V.; Escario, J.-J. Intergenerational association of environmental concern: Evidence of parents’ and children’s concern. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 48, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acock, A.C.; Bengtson, V.L. Socialization and attribution processes: Actual versus perceived similarity among parents and youth. J. Marriage Fam. 1980, 42, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitbeck, L.B.; Gecas, V. Value attributions and value transmission between parents and children. J. Marriage Fam. 1988, 50, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, K.; Yorifuji, K.; Ohnuma, S.; Matthies, E.; Kanbara, A. Transmitting pro-environmental behaviours to the next generation: A comparison between Germany and Japan. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 18, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado, S.; Evans, G.W.; Sorrel, M.A. The role of parents and best friends in children’s pro-environmentalism: Differences according to age and gender. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 54, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeusen, C. The intergenerational transmission of environmental concern: The influence of parents and communication patterns within the family. J. Environ. Educ. 2014, 45, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory. Can. J. Sociol. 1977, 2, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossbart, S.; Hughes, S.M.; Pryor, S.; Yost, A. Socialization aspects of parents, children, and the internet. Adv. Consum. Res. 2002, 29, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, A.J.; Cullen, P. The child–parent purchase relationship: “Pester power”, human rights and retail ethics. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2004, 11, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingert, K.; Zachary, D.A.; Fox, M.; Gittelsohn, J.; Surkan, P.J. Child as change agent. The potential of children to increase healthy food purchasing. Appetite 2014, 81, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belch, M.A.; Krentler, K.A.; Willis-Flurry, L.A. Teen internet mavens: Influence in family decision making. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damerell, P.; Howe, C.; Milner-Gulland, E.J. Child-orientated environmental education influences adult knowledge and household behaviour. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 015016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvall, J.; Zint, M. A review of research on the effectiveness of environmental education in promoting intergenerational learning. J. Environ. Educ. 2007, 38, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.; McEwen, L.J.; Quinn, N. As the climate changes: Intergenerational action-based learning in relation to flood education. J. Environ. Educ. 2016, 48, 154–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legault, L.; Pelletier, L.G. Impact of an environmental education program on students’ and parents’ attitudes, motivation, and behaviours. Can. J. Behav. Sci. / Rev. Can. Des Sci. Du Comport. 2000, 32, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddox, P.; Doran, C.; Williams, I.D.; Kus, M. The role of intergenerational influence in waste education programmes: The THAW project. Waste Manag. 2011, 31, 2590–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, D.F.; Stevenson, K.T.; Peterson, M.N.; Carrier, S.J.; Strnad, L.R.; Seekamp, E. Children can foster climate change concern among their parents. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2019, 9, 458–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Jia, F. Intergenerational transmission of environmental knowledge and pro-environmental behavior: A dyadic relationship. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 89, 102058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, J.J. The role of the child in adult development. J. Adult Dev. 2002, 9, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, D.F.; Stevenson, K.T.; Peterson, M.N.; Carrier, S.J.; Strnad, R.; Seekamp, E. Intergenerational learning: Are children key in spurring climate action? Glob. Environ. Chang. 2018, 53, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, K.T.; Peterson, M.N.; Bondell, H.D.; Moore, S.E.; Carrier, S.J. Overcoming skepticism with education: Interacting influences of worldview and climate change knowledge on perceived climate change risk among adolescents. Clim. Chang. 2014, 126, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodson, M.; Marvin, S. Can cities shape socio-technical transitions and how would we know if they were? Res. Policy 2010, 39, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G.; Longhurst, N. Desperately seeking niches: Grassroots innovations and niche development in the community currency field. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R. The dragons of inaction: Psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacroix, K.; Gifford, R.; Chen, A. Developing and validating the dragons of inaction psychological barriers (DIPB) scale. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 63, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.D.; Chen, A.K.S. Why aren’t we taking action? Psychological barriers to climate-positive food choices. Clim. Chang. 2016, 140, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrus, G.; Passafaro, P.; Bonnes, M. Emotions, habits and rational choices in ecological behaviours: The case of recycling and use of public transportation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Green, R.J. Children’s pro-environmental behaviour: A systematic review of the literature. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 205, 107524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodama, T. Environmental education in formal education in Japan. Jpn. J. Environ. Educ. 2017, 26, 4_21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, N.W.; Li, N.J.; Wang, N.X.; Zhao, N.J. Application of computers in environmental education in China. In Proceedings of the 2010 2nd International Conference on Education Technology and Computer, Shanghai, China, 22–24 June 2010; pp. V3-87–V3-89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Niu, G.; Gan, X.; Cai, Q. Green returns to education: Does education affect pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors in China? PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. China—Data [Data Set]. Worldbank.org. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN?locations=CN&name_desc=false (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Jiang, Q.; Li, S.; Feldman, M.W. China’s population policy at the crossroads: Social impacts and prospects. Asian J. Soc. Sci. 2013, 41, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, E.; Liu, C.; Otsuki, E.; Mochizuki, Y.; Kashiwabara, E. Comparing child-care values in Japan and China among parents with infants. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2012, 18, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Farver, J.A.; Zhang, Z.; Zeng, Q.; Yu, L.; Cai, B. Mainland Chinese parenting styles and parent-child interaction. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2005, 29, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudet, H.; Ardoin, N.M.; Flora, J.; Armel, K.C.; Desai, M.; Robinson, T.N. Effects of a behaviour change intervention for girl scouts on child and parent energy-saving behaviours. Nat. Energy 2016, 1, 16091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, R.; Khoo-Lattimore, C. Same, same, but different: The influence of children in Asian family travel. Asian Cult. Contemp. Tour. 2018, 1, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R. Environmental psychology matters. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 541–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Jones, R.E. Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised NEP scale. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baierl, T.-M.; Johnson, B.; Bogner, F.X. Assessing environmental attitudes and cognitive achievement within 9 years of informal earth education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntanos, S.; Kyriakopoulos, G.; Skordoulis, M.; Chalikias, M.; Arabatzis, G. An application of the new environmental paradigm (NEP) scale in a greek context. Energies 2019, 12, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taye, F.A.; Vedel, S.E.; Jacobsen, J.B. Accounting for environmental attitude to explain variations in willingness to pay for forest ecosystem services using the new environmental paradigm. J. Environ. Econ. Policy 2018, 7, 420–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoli, C.C.; Johnson, B.; Dunlap, R.E. Assessing children’s environmental worldviews: Modifying and validating the new ecological paradigm scale for use with children. J. Environ. Educ. 2007, 38, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, B.T.; Toth, N.; Little, L.; Smith, M.A. Planning to save the planet. Environ. Behav. 2016, 48, 1049–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J.O.; DiClemente, C.C. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1983, 51, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatersleben, B.; Appleton, K.M. Contemplating cycling to work: Attitudes and perceptions in different stages of change. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2007, 41, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meloni, I.; Sanjust, B.; Sottile, E.; Cherchi, E. Propensity for voluntary travel behavior changes: An experimental analysis. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 87, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosone, L.; Chaurand, N.; Chevrier, M. To change or not to change? Perceived psychological barriers to individuals’ behavioural changes in favour of biodiversity conservation. Ecosyst. People 2022, 18, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desrochers, J.E.; Zelenski, J.M. Why are males not doing these environmental behaviors?: Exploring males’ psychological barriers to environmental action. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 42, 25042–25060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Kaida, N. Children’s Pro-environmental Attitudes and Behaviors in Climate Change Mitigation: Findings from Japan and China. J. Environ. Inf. Sci. 2024; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Mouchrek, N.; Cullen, C.; Ganino, A.; Gliga, V.; Kramer, P.; Mahesh, R.; Maunder, L.; Murray, S.; Scott, K.; Shaikh, T. Investigating environmental values and psychological barriers to sustainable behaviors among college students. Consilience 2023, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, J.; Castro, S.L.; Souza, A.S. Psychological barriers moderate the attitude-behavior gap for climate change. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, W.L.; Kenny, D.A. The actor–partner interdependence model: A model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2005, 29, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, L.; Kashy, D.A. Estimating actor, partner, and interaction effects for dyadic data using PROC MIXED and HLM: A user-friendly guide. Pers. Relatsh. 2002, 9, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.D.; Guagnano, G.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Y.; Li, J.; Xie, J.; Zhang, L.; Lou, Q. Will “green” parents have “green” children? The relationship between parents’ and early adolescents’ green consumption values. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 179, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallis, H.; Klöckner, C. The transmission of energy-saving behaviors in the family: A multilevel approach to the assessment of aggregated and single energy-saving actions of parents and adolescents. Environ. Behav. 2018, 52, 275–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, J.; Bengtson, V.L.; Dunham, C.C. Attitude similarity in three-generation families: Socialization, status inheritance, or reciprocal influence? Am. Sociol. Rev. 1986, 51, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterling, D.; Miller, S.; Weinberger, N. Environmental consumerism: A process of children’s socialization and families’ resocialization. Psychol. Mark. 1995, 12, 531–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentina, E.; Muratore, I. Environmentalism at home: The process of ecological resocialization by teenagers. J. Consum. Behav. 2012, 11, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiskanen, E.; Johnson, M.; Robinson, S.; Vadovics, E.; Saastamoinen, M. Low-carbon communities as a context for individual behavioural change. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 7586–7595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Sinkovics, R.R.; Bohlen, G.M. Can socio-demographics still play a role in profiling green consumers? A review of the evidence and an empirical investigation. J. Bus. Res. 2003, 56, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.Y.; Bowker, J.M.; Cordell, H.K. Ethnic variation in environmental belief and behavior. Environ. Behav. 2004, 36, 157–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, L.; Erkal, N.; Gangadharan, L.; Meng, X. Little emperors: Behavioral impacts of China’s one-child policy. Science 2013, 339, 953–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Van De Vijver, F. Bias and equivalence in cross-cultural research. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2012, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauro, J. Cultural Effects on Rating Scales. MeasuringU. Available online: https://measuringu.com/scales-cultural-effects/ (accessed on 5 February 2020).

- Chen, C.; Lee, S.; Stevenson, H.W. Response style and cross-cultural comparisons of rating scales among East Asian and North American students. Psychol. Sci. 1995, 6, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, R.; Tseng, V. Parenting of Asians. In Handbook of Parenting Volume 4 Social Conditions and Applied Parenting, 2nd ed.; Bornstein, M.H., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 59–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, J.B.K.; Shao, Y.; Wang, Q. Father, mother and me: Parental value orientations and child self-identity in Asian American immigrants. Sex Roles 2008, 60, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabar, H.; Hara, K.; Uwasu, M. Comparative assessment of the co-evolution of environmental indicator systems in Japan and China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2012, 61, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C.; Bi, C. Building sustainability education for green recovery in the energy resource sector: A cross country analysis. Resour. Policy 2023, 81, 103385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Tong, X. Fostering green growth in Asian developing economies: The role of good governance in mitigating the resource curse. Resour. Policy 2024, 90, 104724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, N.; Davis, A.; Rafaeli, E. Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2003, 54, 579–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelezny, L.C.; Chua, P.-P.; Aldrich, C. New ways of thinking about environmentalism: Elaborating on gender differences in environmentalism. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).