Abstract

Resilience has become a focal point of academic research investigating the impact of adverse disruption to the well-being of people, systems, the built environment, ecosystems, and climate. However, the proliferation of this work has not been accompanied by increasing clarity about the core meaning of resilience as a singular construct, threatening its relevance and complicating its use in practice. To improve the application of resilience in cross-disciplinary and convergence approaches to sustainability and well-being research, this work synthesized resilience conceptualizations across disciplines with novel artificial intelligence (AI)-augmented approaches. Using open-source applications for text mining and machine-learning-based natural language processing algorithms for the examination of text-as-data, this work mapped the content of 50 years of academic resilience work (24,732 abstracts). Presented as thematic and statistical textual associations in a series of network maps and tables, the findings highlight how specific measurements, components, and terminologies of resilience relate to one another within and across disciplines, emphasizing what concepts can be used to bridge disciplinary boundaries. From this, a converged conceptualization is derived to answer theoretical questions about the nature of resilience and define it as a dynamic process of control through the stages of disruption and progression to an improved state thereafter. This conceptualization supports a cross-disciplinary meaning of resilience that can enhance its shared understanding among a variety of stakeholders, and ultimately, the rigor and uniformity of its application in addressing sustainability and well-being challenges across multiple domains.

Keywords:

resilience; well-being; health; systems; convergence; review; AI; sustainable development; Leximancer; VOSviewer 1. Introduction

Resilience has become a focal point of academic research investigating the impact of adverse disruption to people, systems, the built environment, ecosystems, and climate [1]. Although resilience research spans diverse settings and units of analysis, the proliferation and variety of this work have not been accompanied by increasing clarity about the core meaning of resilience as a singular construct [2,3] (p. 2). Resilience thus remains “deceptively simple […], rife with hidden complexities” and “unresolved questions” that limit shared meaning in its use as a disaster and disruption mitigation framework across disciplines and contexts [4] (p. 39). The wide appeal of cross-disciplinary and convergence research can be a valuable asset in directly influencing policies that offer inclusive, sustainable, multi-domain solutions to complex real-world challenges, but only if the terms and definitions used in the research understood uniformly among contributing stakeholders [5,6]. A more consolidated conceptualization of resilience across the disciplinary landscape could help justify answers to theoretical questions about its frame of reference, increase its shared meaning as a construct, and thus ultimately enhance the rigor and relevancy of resilience research among government agencies, academicians, and practitioners [7,8].

Prior work has attempted to synthesize resilience research to this end but has been constrained by scope, discipline, typology, or domain [9,10,11]. Since the first published mention of resilience in the context of sustainability occurred just over 50 years ago in 1973 [12], this study employs artificial intelligence (AI)-augmented approaches to perform a content-driven mapping of the resilience literature during the last five decades. The work first offers a brief history of the concept of resilience, as well as an overview of ongoing theoretical questions relating to its conceptualization. It then outlines the techniques used to access, clean, and analyze a corpus of 24,732 resilience research abstracts. This approach also provides a new methodological blueprint to improve large-scale cross-disciplinary text analyses and review processes more generally for other researchers.

Presented as thematic and statistical textual associations in a series of network maps and tables, the findings highlight how specific measurements, components, and terminologies of resilience relate to one another within and across disciplines, emphasizing what concepts can be used to bridge disciplinary boundaries and better apply resilience towards advancing inclusive, multi-domain health and well-being interventions. From this textual analysis, a converged conceptualization is derived to answer theoretical questions about the nature of resilience and define it as a dynamic process of control through the stages of disruption and progression to an improved state thereafter. This conceptualization supports a cross-disciplinary meaning of resilience that is derived from diverse perspectives. As such, it enhances a shared understanding of resilience and can support improved rigor of its application in addressing sustainability and well-being challenges across multiple domains

1.1. Background on the Resilience Landscape

The pressing need to understand resilience in a less fragmented manner is apparent, as the scientific understanding of the interdependence of human, biological, and physical domains becomes clearer [13] (p. 38), and multiple levels of consideration must be incorporated to avoid harm in each [3]. As such, wide-scale problems facing humankind require concepts or frameworks that support the study of these domains through a more collective lens [14,15]. This lens, termed panarchy in the early 2000s [16], is often positioned as an evolution of resilience as a concept [6] and gives way to the contemporary application of convergence, an approach to large-scale problem solving that requires inter- and trans-disciplinarity in “working across and beyond several disciplines” [17] and demands the synthesis of multiple perspectives, methods, tools, and analytical approaches [18,19]. Presumably, as the importance of conceptual interconnectivity and transcending disciplinary boundaries has become more commonplace within the philosophy of scientific production [17], resilience should continue to divest from segmented applications in support of those that can be used meaningfully across contexts through shared conceptualizations and translations [20].

Despite its potential for use in convergence research, resilience has evolved within a complex etymological and disciplinary history [21]. Resilience originates from the Latin word resiliere, which means to jump or bounce [22], but its meanings in English until the 20th century have been as diverse as shrinking, avoiding, (physically) jumping, rebounding, possessing fortitude, acting fickle, or maintaining physical integrity [23,24]. Holling’s 1973 seminal work within the discipline of systems ecology, Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems [12], is frequently credited as the first academic use of resilience as a broad sustainability concept [15,25,26]. Within systems ecology, resilience often refers to the degree to which a physical or ecological system can absorb disruptions while retaining basic function and structure [13,25]. Its subsequent early uses in ecological disciplines often focused on how to limit the severity of human-driven environmental accidents by increasing the capacity of the environment to sustain them [27].

Simultaneously, resilience was also examined in the mid-20th century within more human-centered disciplines such as psychology and anthropology [23,24]. Here, resilience was initially positioned as an individual’s positive and negative responses to trauma [23,24], as well as a child’s developmental response to severe psychopathology and/or life disruptions [28,29]. Within these contexts, resilience has not necessarily demanded an ecological, systems-oriented approach [23] (p. 2712), but rather, emphasized more focus on examining biological reactions, psychological coping, and behavioral responses to adverse events as mediated by other factors such as age, family history, social class, culture, history, and gender [30] (p. 7).

The two applications began to merge as human development, geography, and economics took more interest in understanding resilience as a societal resistance to various types of life disruptions and disaster shocks [31,32]. As international efforts (such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, SDGs) began to emphasize the importance of balancing human and environmental functions to work symbiotically [22,27,33], resilience work expanded to better understand these functions by way of also examining adjacent concepts such as vulnerability, adaptation, development, well-being, and sustainability [26].

1.2. Ongoing Theoretical Questions

To meet this challenge of better understanding the interactions of human and non-human systems in the context of health and well-being, especially within the past decade, resilience has been applied to examine the growing numbers of specific elements, groups and systems across disciplines and sub-disciplines [3]. This has simultaneously generated a litany of theoretical questions about what resilience is at its core, or if it is, in fact, merely an “under-theorized term of art” difficult to apply across contexts [15] (p. 143). Extensive work reviewing various resilience definitions [3,7,20,34] often finds they do not necessarily answer or account for theoretical questions within their definitional scope [35]. Although theoretical conflicts about resilience may continue to be debated, and resilience can maintain specific disciplinary applications, consolidating justifiable answers across a variety of disciplinary perspectives can help come to a functional conclusion that makes resilience as a concept easier to apply uniformly across a variety of contexts by a variety of stakeholders in support of convergence approaches to sustainability challenges.

At a broader level, summarized briefly here, current conflicts regarding the conceptualization of resilience focus on the following: the types of items to which the resilience can be applied, the specific properties of the item and its state of operating to which resilience bears reference, and the extent to which resilience is distinct from other (related or conflated) states of optimal function or quality. First, these conflicts raise a question as to what resilience specifically refers or measures. Disciplines seem to agree that resilience means maintaining some degree of endurance or retaining some essential qualities of optimal function [23,33]. However, both the degree and temporal frame can be unclear [25], often casting resilience into one of three distinct categories [36]: (1) the pre-disturbance ability to subsume disturbance before fundamentally changing to a new (positive or negative) state (sometimes termed persistence or the capacity to absorb shocks); (2) the within-disturbance ability to return to the state before disruption (sometimes termed transition or the capacity to bounce back); or (3) the post-disturbance ability to adapt to a disruption and evolve in structure, function, and organization (sometimes termed transformation or the capacity to advance forward). Casting resilience into one of these areas has methodological and practical implications [37], as each category demands focus on different qualities and behaviors of the item or stage under investigation [3].

Incidentally, how resilience is categorized brings up related questions about resilience’s distinction from or relation to adjacent concepts such as stability, vulnerability, adaptation, growth, and sustainability that must be adequately defined to better account for the multi-layered effects of interventions on interconnected human- and non-human systems. Situationally, these adjacent concepts may be treated as conditions for or components of resilience [26] or analytical antonyms that may not be able to co-occur with resilience [25]. A system’s components, for example, may fluctuate widely, being either highly diverse and/or highly unstable—which is incidentally often considered a definition of vulnerability and a negative quality associated with resilience [38]. But whether or not this behavior actually helps or hinders a system’s or sub-element’s capacity to cope or even adapt is likely dependent on measurement, level, or scale [39]. The question remains in both ecological [39,40] and social contexts [8]. Similar conflations exist in the adjacent concepts of growth, development, adaptation, recovery, and sustainability, which are all sometimes used interchangeably, but may also imply ontological impossibilities depending on whether resilience is defined as a return or an evolution [25]. In the former case, concepts such as growth, development, or adaptability may be antithetical in that they imply a progression towards something new [23,26,41], and in the latter, that recovery assumes a return to something that no longer exists [42].

Fundamentally, these questions relate to whether and how resilience can be streamlined and applied in ways relevant to both human and non-human systems [20,25,33]. It has been argued that domain separation is necessary in resilience research because specific situational dynamics of resilience must be understood [36] in that indicators or prerequisites of resilience may be weakly correlated or unrelated to one another [30,43,44]. More modern scholarship tends to argue that this question can be addressed by situating the work within a specific level of function (i.e., micro vs. macro), as well as relying on cross-disciplinary (e.g., human geography, environmental economics) lenses and vocabularies [42,45,46]. As these cross-disciplinary lenses have expanded into their own areas of study [25,27], and the view of physical, ecological, social, and other systems as interconnected entities has become more commonplace [47], resilience has the potential to be applicable in convergence contexts, but relevant, streamlining clarifications about its composition and applications are likely necessary for this to occur [20,34].

Ultimately, an optimal conceptualization of resilience to apply in a convergence or cross-disciplinary context should ideally account for the considerations of multiple components of a group or system to avoid the benefit of one component at the extreme expense of another [48] (p. 110). Resilience, when ill-defined as “many things” [2] (p. 2), can raise unaddressed questions about what perspectives should be emphasized and what capacities, speeds, and end states are desirable or not [49,50]; in other words, what specific individuals, structures, or systems are resilient; to what they are resilient; and what end their resilience reaches [48,51]. Failing to answer these questions risks choosing inappropriate research approaches and reducing the potential for meaningful broader impacts of development projects [3,9], especially in convergence contexts, but unfortunately, these fragmentations and unanswered questions remain commonplace [1].

2. Methods

In response to these challenges, this work seeks to translate and synthesize these complexities to define resilience in a manner that can be more meaningful and functional across various applications. Through the analysis of text-as-data, the work examines how resilience concepts, as well as disciplinary influences and topical focus over time, map across the resilience research landscape and functionally illustrate how resilience can be better applied within and across disciplines. With this, it aims to present a more complete understanding of how the research repository at large consolidates answers to theoretical questions about the nature of resilience in support of the notion that resilience can be framed as something dynamic and interconnected in line with cross-disciplinary and convergence research approaches [6].

2.1. Semi-Systematic Mapping

Various reviews of resilience work attempt to come to conceptual resolutions about its composition, however, they remain constrained by volume [9,52,53]; disciplinary domains [11,54,55,56]; or specific populations [21,57,58,59]. To address these issues, this work takes a semi-systematic mapping approach to examine the academic resilience landscape more wholistically across disciplines. A semi-systematic approach presents a “broad overview [of a] research area” that “track[s] development over time” [60] (p. 334), balancing documented collection criteria with a wider scope of inclusion to summarize different disciplinary perspectives in an overarching narrative [61] (p. 2).

2.2. Computer-Assisted and AI-Augmented Approaches

Broadly, AI refers to using non-human means to perform tasks typically associated with human intelligence or cognitive decisions [62]. AI-augmented text analysis techniques—such as process automation, machine learning, and natural language processing that improve analytical task performance and can be trained to identify and interpret language patters [63]—are common solutions to improve logistical challenges in examining large volumes of text [64,65,66]. Fundamentally, they can enhance the ability to approach an enormity of text data with systematization and transparency beyond what standard approaches can handle [67]. For research reviews and concept mapping specifically, AI-augmented approaches can enhance the speed of retrieval and ease of inclusion screening [68], as well as increase the amount of input reviewed for more comprehensive understandings of the topic at hand [69].

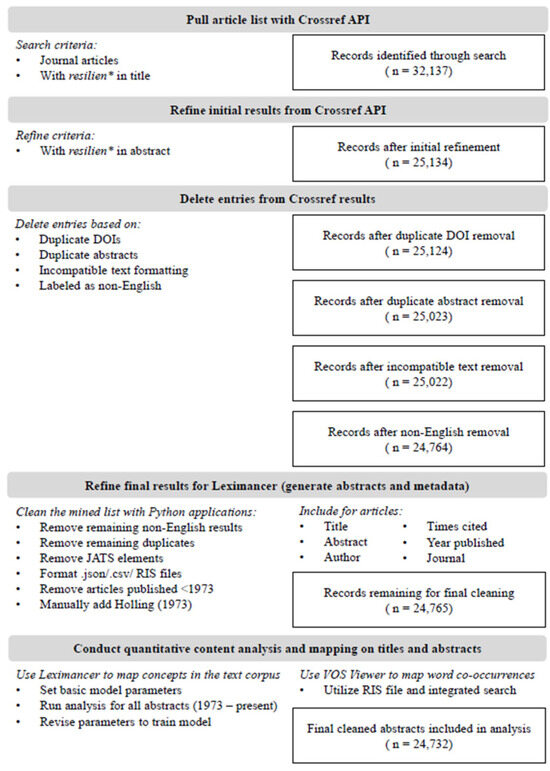

This work relied on two AI-augmented approaches to text analysis: (1) Python applications to automate a variety of text extraction processes for data retrieval, data cleaning, and file preparation (e.g., [70]); and (2) unsupervised machine learning, natural language processing, and network mapping techniques that used mathematical and probabilistic algorithms to quantify and model relationships between words and analytical units within the text [64,71,72]. These approaches and their benefits enabled the logistical capacity to produce a functional synthesis of resilience concepts across a large volume of work transcending disciplines. Additionally, the application of available automation tools in a novel procedural combination (Figure 1) served as a use case to trial their viability as a mechanism for other researchers.

Figure 1.

Text retrieval, cleaning, and analysis process.

2.2.1. Database Selection and Search Criteria

Crossref is a digital object identifier (DOI) registration agency that offers a variety of services including a metadata retrieval application programming interface (API). Crossref was chosen as the academic literature database to mine because of automation capabilities within the API, as well as compatibility with the other tools and software used. Within the API, users may query all registered Crossref objects and retrieve the relevant metadata in a JSON format. Objects classified as journal articles, containing one or more of “resilient”, “resilience”, and “resiliency” in the title and containing an abstract, were collected in February 2024. Initially, 32,137 objects meeting the search criteria were retrieved. All objects had DOIs.

2.2.2. Text Extraction, Cleaning, and Analysis Preparation

After initial API retrieval, objects were screened for the following inclusion criteria: the article must be published in 1973 or later, the abstract must contain one of more of “resilient”, “resilience”, and “resiliency”, and the abstract must be written in English. The originating year was set at 1973, the year in which the work [12] frequently credited with the first use of resilience in a sustainability context was published [15,25,26]. Since Crossref metadata does not include a field for language, the Python library ‘langdetect’ was used to assign language tags to each abstract. Additionally, duplicate abstracts were excluded. After screening the retrieved objects for these criteria, 24,731 remained. Holling’s 1973 work [12] was added manually to the dataset because it was indexed in Crossref without an abstract, bringing the total number of abstracts to 24,732. Crossref abstracts are typically submitted in journal article tag suite (JATS) format. The Python library ‘BeautifulSoup’ was utilized to remove JATS elements from the raw text of the abstracts. No abstracts were discarded at this stage.

In preparation for text analysis, a CSV consolidated all objects with columns for entry number, article title, abstract, year of publication, number of citations received at the time of API retrieval, year of publication, journal of publication, and DOI. Groupings of publication time and number of citations were calculated and added. The number of times cited was gathered specifically for bibliometric data analysis, as an indicator of a paper’s influence [73].

2.2.3. Content Analysis of Text

Content analysis is the “objective, systematic, and quantitative description” of the content of a text to make observations and inferences about it based on specific characteristics [74] (p. 18). Two AI-augmented software tools—VOS Viewer and Leximancer—provided visual and numeric representations of the themes and concepts emerging from the content of the abstract repository, as well as how they related to one another.

Leximancer was used to facilitate a text-based content analysis of the abstract collection, discover key concepts, examine interrelations between them, and visualize these relationships. Leximancer is a text data-mining tool that uses machine learning algorithms to assist in rapid, quantifiable identification of concepts and themes, especially in large volumes of text [75]. It has been shown to be a reliable tool to enhance qualitative [76] and quantitative [77] approaches to text analysis by means of a stable and replicable process [75,76,78]. Approaches using Leximancer have been used successfully for research synthesis and core concept mapping in various disciplinary contexts (e.g., in cross-cultural psychology [78]; literacy studies [79]; education [80]; tourism and hospitality [81]) as well as in specific domains of resiliency [82,83,84,85,86,87]. The current work builds on these prior AI-supported resilience reviews by expanding the inclusion of research by 30 years [85] and considering disciplinary perspectives beyond the more limited scopes of urban planning [83], disaster recovery [82,84], corporate sustainability [87], and industrial ecology [86] that have been previously investigated with similar methods.

Leximancer has the capacity to support unsupervised and supervised analytical approaches, but its default is to rely on an initial in vivo unsupervised parsing of text input that can be refined later through parameter specification [88]. Salient concepts of interest are comprised of underlying key words that generally travel together throughout the text, and a sentence “is only tagged as containing a concept if the accumulated evidence (the sum of the weights of the keywords found) is above a set threshold” [88] (p. 9).

Table 1 details the process and specific model parameters used in this analysis. The CSV file of abstracts and attributes served as the text input. After an initial run, the algorithm was further trained by removing stop words (i.e., commonly occurring words with grammatical function); merging concepts (i.e., associating concepts with the same word stem); reducing concepts (i.e., ignoring structural concepts, such as functional words or headings); and defining new concepts (i.e., manually inserting concepts, labelling frequently used words as concepts, and/or associating concepts to create additional ones), in this case, to examine the use and associations of specific terms debated in theoretical literature.

Table 1.

Process and settings for analysis in Leximancer.

The final trained algorithm produced a visual concept network map consisting of grey circular nodes and statistical outputs of word and concept co-occurrences. The size of a grey concept node represents the prominence of a concept, and nodes are grouped based on similarity to other concepts. The larger the concept node, the more often the concept is coded in the text along with the other concepts displayed. Gray lines connected to concepts show which concepts share the strongest conceptual similarity [89]. Proportionally sized colored circles (with large circles shaded red being the most prominent and smaller circles shaded purple being least) group concepts into themes, that is, concepts that appear together in the same piece of text and attract one another strongly [88] (p. 12).

VOS Viewer was used to visualize networks of bibliographic- and text-based data from fields in the Crossref metadata (e.g., titles, abstracts, keywords). VOS Viewer is software designed to interface with major academic databases and automatically process the metadata into network visualizations, as well as perform unsupervised machine learning analyses to uncover deeper patterns between terms or datapoints [90]. In its network maps, each term is represented by a circle; the diameter and label size represent the frequency of the term. VOS Viewer automatically performs cluster analysis, which uses an unsupervised AI-augmented algorithm to identify groups of words (i.e., objects) that are densely connected to others within the group and sparsely connected to those outside of the group. The unique clusters are identified by color. VOS Viewer interfaces directly with the Crossref API, allowing the same papers analyzed by Leximancer to be pulled directly via DOI. Because Crossref data lacked subject codes for abstracts, VOS Viewer was also used to map co-occurrences of key words in titles as a proxy for article subjects. This capability in VOS Viewer to network shared terms and key words [91] can be used for mapping research concepts [92] and has been performed successfully across disciplines [93,94,95].

3. Results

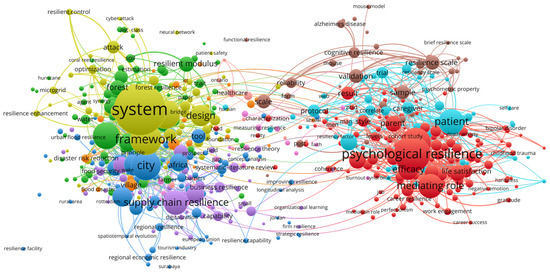

3.1. Conceptualization of Resilience Across the Repository

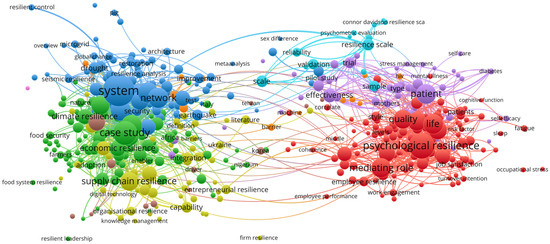

The resilience research repository examined resilience across a wide variety of subject applications. Based on the most frequently co-occurring title key words (as a proxy for article subjects), the subject cluster of system was the most prominent, followed by the cluster of psychological resilience (Figure 2). Other clusters centered around specific human subjects of interest (e.g., parent, patient, caregiver); systems-based areas of resilience (e.g., supply chain, rural, regional, or economic resilience); ecological settings (e.g., forests, coral reefs, water); or methodologies and measurements (e.g., scale, validation, psychometric property). Human- (e.g., parent, patients, caregivers, men) or emotion-oriented (e.g., empathy, gratitude, trauma, self-care) subjects clustered around the subject of psychological resilience; non-human subjects (such as cities, regions, ecosystems, design, disasters) clustered around that of systems resilience. Some bridging subjects between the two primary clusters of the map included resilience theory, enhance resilience, improving resilience, characterization, reliability, scale, and prediction.

Figure 2.

VOS Viewer network map with article title keyword co-occurrences. Title field pulled with binary counting, minimum occurrences of 10 (1150 total); top 60% (690) most relevant kept.

Of 122 topical concepts that emerged across the text repository, resilience was the most relevant, followed by additional concepts that included system, change, health, social, community, and development (Table 2; Appendix A, Table A1 and Table A2).

Table 2.

Top 25 concepts with associated counts, top co-occurring concepts by likelihood, and relevance statistics. Count is the number of text segments identified with the concept. Relevance is the percentage frequency of text segments coded with the concept, relative to the frequency of the most frequent concept (in this case, the time cluster 2020 or later).

Of the primary concepts co-occurring with resilience (Table 3), psychological occurred the most frequently, followed by relationship, role, and positive. Concepts that were most likely to mention resilience included mediating (95% likelihood), relationship (88% likelihood), psychological (83% likelihood), and satisfaction (74% likelihood).

Table 3.

Top 10 concepts co-occurring most frequently with resilience with count of co-occurrences and likelihood of co-occurrence. Likelihood approximates the conditional probability that if the data discusses a co-concept, it also mentions the initial concept.

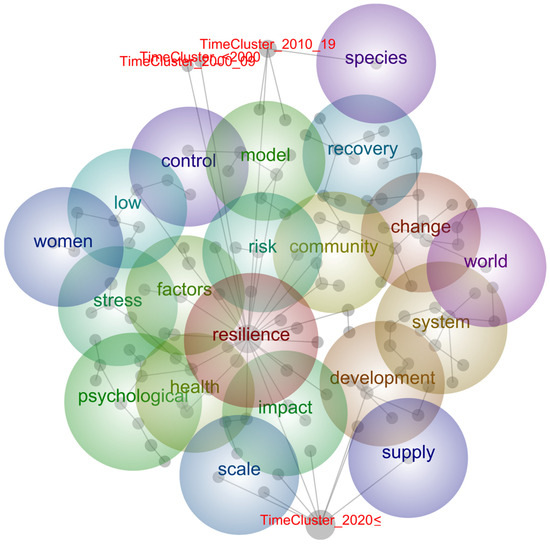

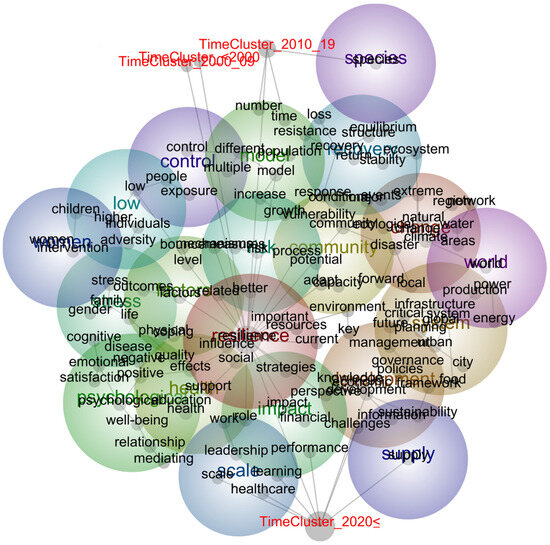

Resilience was the central theme anchoring the thematic map (Figure 3). Human-oriented themes included health, psychological, stress, and women. Systems- or environment-oriented themes included system, world, community, and species. Process- or quality-oriented themes included scale, supply, impact, development, factors, low, risk, control, model, recovery, and change. Themes were comprised of 122 clustered concepts (Figure 4), many of which—such as policies, strategies, growth, vulnerability, sustainability, health, management, and forward—overlapped or bordered multiple themes.

Figure 3.

Leximancer semantic map of resilience research abstracts. Themes shown at 25%. Concepts shown at 0%. Concept dot size reflects extent to which concept co-occurs with others.

Figure 4.

Leximancer semantic map of resilience research abstracts. Themes shown at 25%. Concepts shown at 100%. Concept dot size reflects extent to which concept co-occurs with others.

Concepts clustered around the theme of resilience included better, strategies, and resources. Other notable associations included the concepts of adapt, capacity, and forward clustering near the theme of community; quality, education, support, and work clustering near the theme of health; well-being, satisfaction, and positive clustering around the theme of psychological; sustainability, framework, knowledge, and management clustering around the theme of development; level and outcomes clustering around the theme of factors; and exposure, multiple, and different clustering around the theme of control (Table 4).

Table 4.

Auto-generated themes and selection of concepts clustering around themes.

Predictive thesaurus terms found additional indicators for specific topics or terms from the resilience literature that related to a given concept (Table 5). Some concepts were predicted more clearly by systems-oriented terms, such as equilibrium (predicted by computable, depositional, ecologists, process-based, subsumed), stress (predicted by oxidative, defeat, acculturative), or return (predicted by environment-friendly, irreversibly, non-equilibrium). Other concepts were predicted more clearly by human-oriented terms, such as adapt (predicted by absorptive, flexibility, cross-scale, panarchy), control (predicted by locus, impulse, command, effortful), or sustainability (predicted by livable, risk-informed, specializing, human-centricity).

Table 5.

Adjacent terms from the literature with their top 10 co-occurring concepts by likelihood and top (non-stem) thesaurus terms based on score. Thesaurus score refers to how strongly the presence of the thesaurus term predicts the noted concept.

3.2. Disciplinary Influence and Topic Development over Time

Examining and categorizing texts by time cluster allowed an understanding of the extent to which disciplinary concentrations, consolidations, and concept associations shaped resilience over time in development of current applications. Generally, resilience was not a prominent topic of research based on production until past 2010, after which it showed sharper increases and disciplinary expansion, especially past 2020 (Table 6).

Table 6.

Production of papers by time cluster.

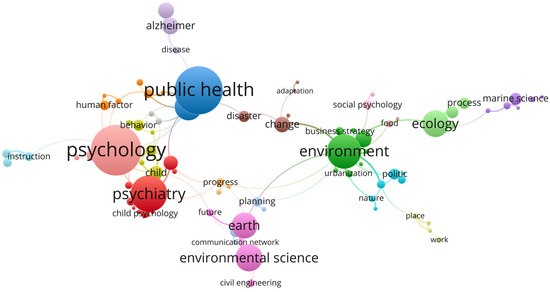

Although the most frequently cited article [12] across the repository was from the discipline of systems ecology (cited 10,038 times), and papers from both psychology and systems ecology continued to be cited highly over time, disciplinary influence began to expand in the early 2000s. Papers from engineering, human geography, psychology, and systems ecology drove top citations, and those from urban studies and business management showed more influence past 2020 (Appendix B). Viewing disciplinary scope and interconnections connections by journal title key words showed similar prominence of human- and systems-oriented disciplinary clusters with relevant sub-topics (e.g., environment > ecology > evolution > marine science; psychology > psychiatry > child psychology), but also connections between them via bridging topics such as change and disaster, as well as progress, planning, adaptation, and public health (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

VOS Viewer network map of abstracts with journal title key word co-occurrences. Journal title field pulled with 632 keywords with 280 manually selected for field indication.

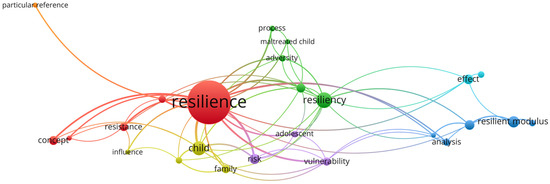

Shifts and expansions in conceptual and subject focus were also shown over time (Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9), extending to a range of disciplines, sub-disciplines, and topical focal points. Prior to 2000 (Figure 6), the scope of resilience subjects was more limited, remaining more concentrated in those such as evaluations of resilience moduli and system disturbance, with a small developing area of child and adolescent resilience amidst stress and adversity. Vulnerability as a subject was located on the periphery with associations to both systems and human applications. In the early 2000s (Figure 7), the focus began to divide into subject clusters retaining systems- and human-oriented applications. Resilience in a human context expanded into more specific areas such as families, children, women, and adults more generally. Additionally, there was an emergence of interest in causal and relational mechanisms such as role, protective factors, response, and interaction. Systems resilience began to cluster around subjects of ecological and community resilience. Vulnerability was a connecting node between subjects about systems like disaster, as well as human ones like child. Adversity was connected to both vulnerability and adaptation.

Figure 6.

VOS Viewer network map of abstracts published prior to 2000 with title keyword co-occurrences. Title field pulled with binary counting, minimum occurrences of 3 (25 total); all relevant kept.

Figure 7.

VOS Viewer network map of abstracts published between 2000 and 2009 with title keyword co-occurrences. Title field pulled with binary counting, minimum occurrences of 5 (64 total); all relevant kept.

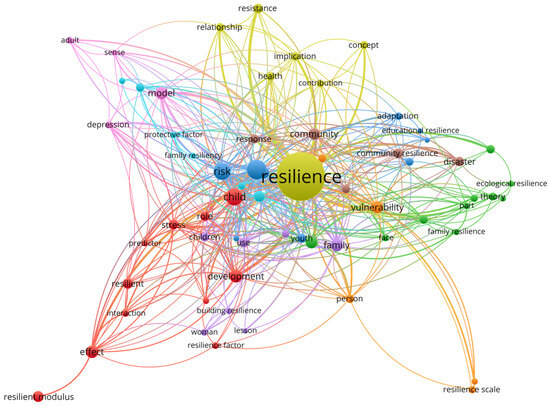

Figure 8.

VOS Viewer network map of abstracts published between 2010 and 2019 with title keyword co-occurrences. Title field pulled with binary counting, minimum occurrences of 10 (287 total); top 60% (172) most relevant kept.

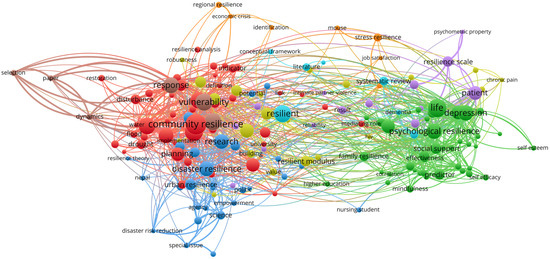

Figure 9.

VOS Viewer network map of abstracts published 2020 and later with title keyword co-occurrences. Title field pulled with binary counting, minimum occurrences of 10 (847 total); top 60% (508) most relevant kept.

In the mid-2000s (Figure 8), clearer human and social subject groupings emerged, distinct from community, environment, or systems ones. Human-centered concepts continued to present alongside psychological topics (e.g., social support, mindfulness, depression, self-esteem), and systems-centered topics showed emphasis on environmental and disaster planning (e.g., drought, flood, planning, building, response). However, more bridging subjects also began to appear between these clusters, to include comparative study, conceptual framework, and reliability. Sub-disciplinary applications (e.g., urban resilience, regional resilience, disaster resilience, psychological stress resilience) also emerged. A selection of quantifiable, systems-oriented subjects (e.g., dynamics, restoration, disturbance) remained at the periphery of the map near the systems cluster.

The topical map of post-2020 work (Figure 9) presented the most diverse conceptualization of resilience, with six distinct subject clusters. However, each cluster also expanded to include more specific resilience applications considering multiple, possibly interconnected sub-topics (e.g., not merely earthquakes but seismic resilience; not merely community resilience but urban resilience or food security; not merely economic resilience but supply chain resilience, organizational resilience, entrepreneurial resilience) and specific target groups of inquiry (e.g., parents, young adults, cancer patients, individuals with specific types of disease, students, employees). Bridging terms situated between the primary clusters included more schematizing subjects such as scale, reliability, protocol, validation, effectiveness, and holistic terms such as improving resilience, resilient society, resilience perspective, resilience capacity, capability, and barrier.

Concepts representing topical emphasis also changed across time (Figure 4, Table 7). Before 2010, the most salient concept was equilibrium, along with emerging applications exploring adversity in children and families. Between 2010 and 2019, the thematic focus was more closely related to change, modelling, and adaptation in an ecological and disaster recovery context. After 2019, the focus shifted to cluster around themes of health, development, and multi-dimensional (e.g., financial, performance, perspectives) impacts, also associated with high frequency of COVID-19 as a concept in the 2020≤ time cluster (Table 8).

Table 7.

Top 5 concepts occurring most frequently per time cluster, shown ranked by likelihood.

Table 8.

Top 5 concepts co-occurring most frequently with COVID post 2020, with count of co-occurrences and likelihood of co-occurrence.

4. Discussion

4.1. Resilience Is Oriented Towards Progression and Positive Change

First, the results offer insights on how the holistic landscape of resilience work answers questions regarding the procedural composition and reference points of resilience. The thematic synthesis favors a cross-disciplinary positioning of resilience more broadly as (1) a dynamic process or response that (2) results in a change that is (3) ultimately in some way positive for the entity undergoing change. This contrasts definitions that prefer to categorize resilience only as the state before a fundamental change [96] or the return to a pre-disturbance state [97] and aligns with those that position it as inclusive of process and progress [1,6] (p. 1670), [98] (p. 3).

This is supported by the prominence of change and development as key themes. Additionally, the concept of different emerged as salient and co-occurred frequently next to level, multiple, strategies, time and response, as did the concept process, which co-occurred with concepts such as forward, learning, and adapt. The concept of adapt was directly associated with the concept of change. All such terms imply dynamism in terms of non-statistic activities advancing towards a differentiated state. This implication was present across human- and systems-oriented contexts, in that the predictive term of adapt was cross-scaled, and change, as a theme, was comprised of the concepts of local, regional, and world in close proximity to one another. Although the concept of return retained some prominence within the overall repository, it appeared more limited in application to systems such as infrastructure, finances, physical properties or ecological conditions with a more direct measurable state of equilibrium or performance stability.

Finally, across the repository, the concept of resilience presents as highly related to the concepts of positive and well-being. The theme of resilience also includes the highly clustered concepts of better, strategies, and resources. Some definitions of resilience [33] suggest that the change which occurs must be to a non-essential component of the system, but the strong emergence of positive terminology across texts suggests that a clearly beneficial end-change could reasonably be associated with a critical or fundamental quality of an entity. The results collectively support the notion that being resilient means that the end state is neither merely any change, nor a return to a prior negative or undesirable quality, but rather, a progression to a state of improvement or positivity. Although various definitions propose the retention of some combination of these elements, the results justify a conceptualization that includes all three components applied in both human- and systems-oriented contexts.

4.2. Resilience Is Broadly a Process of Controlling Uncertainty Through Adversity

The results also highlight the relationships between terms adjacent to resilience (e.g., stability, recovery, vulnerability, growth, development, well-being, and sustainability) discussed commonly in the theoretical literature and how these distinctions may be meaningfully parsed for use in multi-level, multi-domain contexts that demand attention to them.

Stability, for example, falls under the theme of recovery. It co-occurs frequently with concepts of ecosystem, equilibrium, ecological, performance, and system, situating the use of both recovery and stability more as systems-oriented terms, particularly related to ecological or measurable contexts given its quantitative thesaurus terms. Concepts co-occurring with the concept of recovery include other measurable concepts such as loss, time, growth, and resistance; disaster or post-disaster were also related concepts and thesaurus terms. These associations suggest that using terms such as stability or recovery in a human context should be limited more to more directly measurable responses or outcomes from a specific disruptive event.

Vulnerability, on the other hand, is somewhat more commonly associated with human-oriented thesaurus terms (e.g., disempowering, well-being), although it co-occurs with both human- (e.g., population, exposure) and systems-oriented concepts (e.g., climate, mechanisms, natural, areas). It is associated most closely under the theme of community, although the associations generally support that vulnerability can reasonably be discussed either more generally or specifically in a human- or systems-oriented context. Development and sustainability seem to function as human–systems bridging terms, in that they co-occur frequently with those related to human-oriented systems (e.g., the concepts of city, policies, urban, food, supply, production, economic or the thesaurus terms of liveable, human-centricity) and could be associated with measurable outputs (e.g., food supply, production, economic activity, which can be quantified). Overall, the mapping of these adjacent terms supports both contextual and broader use with appropriate delineations, in line with the theoretical literature [33].

However, a particularly salient co-concept to resilience that emerged and appeared more applicable to the whole text repository was adversity. Similarly, control appeared as a theme in the broader map and was associated with concepts such as people, multiple, different, and exposure. Co-occurring concepts to control included both systems-related concepts (e.g., system, return, mechanisms) as well as human-related concepts (e.g., power, emotional), and predictive thesaurus terms (e.g., command, effortful) that implied control as active, deliberate (power, effortful) and oriented to an instigator and location (locus, intervention). These associations suggest that the process of control through exposure to adversity travels closely to resilience. This dimension of resilience is present in some definitions [22] (p. 43), especially those that attempt to be more comprehensive from a planning or intervention perspective [52], although some [25,99] do not consider control, or planning, across all stages of a disruption. Although some elements of resilience work may need to focus on a particular stage of a disruptive event, the broad analysis supports understanding multi-modal resilience enhancement by way of accounting for the entirety of the disruption process—before, during, and after—to localize different effects, command effort and power towards mitigation, and maintain control over the adversity that caused the disruption.

4.3. Resilience Can Be a Tool to Support Convergence

Finally, the results suggest that although resilience retains conceptual applications, it can nonetheless be applied meaningfully across disciplines to be used in convergence contexts. Resilience retains clear psychological or human-centered applications, along with systems- or environmentally oriented ones, for example, emphasizing different types of people (e.g., people with different ages, gender, employment status, familial status), circumstances (e.g., types of disease, area of living), ecosystems (e.g., forest, ocean), or system sub-components (e.g., supply chain, governance) to which resilience might apply. Themes show similar clusters, for example, in concepts of emotions, relationships, cognitive functions, or coping relating to the psychological domain and concepts of power, energy, food, infrastructure, healthcare, production, ecological conditions, and climate relating to systems or environment domains.

Nonetheless, resilience is also positioned to apply in convergence contexts in that it is discussed commonly alongside concepts concerning systems, health, community, and sociality, with change and adaptation as central topics connecting a variety of topical nodes. Especially going into the 2000s, measuring, characterizing, scaling, theorizing, and reviewing resilience became more common, demonstrating its application as a concept that connects systems, environments, and people and implying attempts to systematize relationships between them. Overall, the most salient adjacent concept to resilience is found, in fact, to be mediating, followed by relationship; the broader themes of factors, risk, community, and health all intersect closely with the theme of resilience. These proximities suggest that resilience can and must touch on multiple qualities and components of an entity to understand how it responds to a disruption, not exclusively focus on one disciplinary aspect due to definitional scope.

These findings also align with historical interpretations about the evolution of resilience [23,27], which suggest that large-scale, international projects (beginning in the early 2000s) that demanded convergence approaches—such as the SDGs and the examination of resilient global cities, and later, the global COVID-19 pandemic—required an expanded application of resilience as a way to examine the inherent interdependence of people and ecosystems, as well as the bidirectional influences of fluctuations in these areas on multiple levels (i.e., micro, meso, macro) of performance [13,25]. As the holistic mapping supported resilience as a dynamic, advancing, change-oriented and adaptive process, the most predictive terms associated with the concept of adapt vis-à-vis the resilience landscape are in fact flexibility, cross-scale, and panarchy. This supports the idea that resilience can be aligned with convergence approaches to research more generally, to examine how different elements of human-systems relationships change and contribute to end states of disruption or harmony [26,41].

4.4. Limitations

A primary limitation of the work is its reliance on a single database. Although Crossref is generally found to have a robust level of coverage [100], it does not capture relevant work from journals not indexed. Similarly, the abstracts pulled are only as good as the quality of metadata. Future iterations would expand the search to other databases and allow for content comparisons to examine how indexing promotes bias or exclusion in resilience work [101].

Additionally, the work is limited by the novelty of AI and text-mining processes that, while powerful, still present logistical difficulties, such as a lack of customization within search or analysis interfaces, processing rates, processing complexity, and access restrictions. The tools’ inability to access and clean data also constrained some analytical capacity. For example, no applications were found to reliably access and clean full paper texts, although this is mitigated by the volume of abstracts included. In this regard, the work is also limited by the inability to mine pertinent policy documents and grey literature, a potential shortcoming in the resilience space, where much work is pioneered and implemented by practitioners and non-academic organizations [102]. The inclusion of English-only articles is also driven by the emerging and largely inadequate capabilities of AI-augmented approaches to analyze concepts across multi-language texts [103], which substantiates criticisms that development discourse is overly western-centric [104]. Optimistically, future technological improvements and capacity to enhance research scale would address these points for greater inclusivity.

The limitations highlight both that AI-augmented approaches are not a panacea for challenges in the analysis of big data [105], as well as that academic databases are not yet designed to function as a source of big data [106]. Nonetheless, this work represents an initial and accessible use case using readily available tools, presenting an example of text mining, mapping, and analysis far more extensive than manual processes could support.

5. Implications, Recommendations, and Conclusions

This work presents how themes, concepts, and components of resilience relate to one another within and across disciplines, supporting a more parsimonious definition of resilience as a dynamic process of control through the stages of disruption and progression to an improved state thereafter. This positioning consolidates answers to theoretical questions and is synthesized from multiple perspectives, providing a standardized point from which a variety of researchers, practitioners, and stakeholders can conduct resilience work and better account for the dynamics of disruption. Additionally, the associations among related terms highlight bridging concepts that investigators from various disciplines can use to explore more thoroughly in their own disciplinary contexts, as well as cross-disciplinary boundaries when terms representing topics, outcomes, and measures that apply to multiple components of human and system well-being.

The consolidated perspective of resilience resulting from this work helps avoid paradigmatic barriers inherent in other views of resilience that could limit opportunities for tailored interventions to increase resilience in multifaceted contexts such as emergency management, public policy, climate and hazard mitigation, and public health. It supports a broad positioning of resilience beyond frameworks or definitions guided by a focus on one academic discipline or goal. In applying this perspective on resilience, future work should attempt to understand and explain the dynamism of resilience as a process. The specific parameters of the starting state should be identified, along with the noted disruption and the specific details of its own progress. As disruption is presumed to have pre-, during-, and post-phases, characteristics of each should be considered, along with those of the entity that is changing during each phase of disruption. How these phases can or cannot be controlled more deliberately and by whom can provide insights into identifying vulnerabilities at various levels, such as locality, community, or society. Particularly in the post-disruption phase, resilience should be assessed in terms of the improvements or positive changes that an entity has reached or is reaching. If no change or negative change has occurred, questions should be asked regarding if the entity is resilient at all and whether resilience is the correct concept to assess. If an entity sustains positive change at the expense of another, these potential conflicts should be disclosed, considered, and justified in ongoing evaluation and intervention efforts.

As such, this approach to resilience can assist in better accounting for the components necessary to evaluate the most desirable end states and design the most suitable interventions. Given that interventions and outcomes can differ depending on the group, system, or element of focus, this application helps avoid work that inadequately answers to what the target is resilient, to where it ought to progress, and to whom or what the benefit of resilience applies. This emphasizes the need for policies guiding pre- and post-disturbance operations to engage people (i.e., state governments, local leaders, industry stakeholders, businesses, individuals in a community) and consider system components (i.e., climate, ecosystems, species, sub-species or production channels, materials, elements) at various levels throughout planning and intervention processes. For those leading or contributing to the development of resilience initiatives, accounting for these ways that components of resilience relate to one another can ensure that plans and interventions are comprehensive, inclusive, and known by all those who will take part in them across multiple domains. This way of applying resilience helps avoid irrelevant actions that neglect certain components of optimal function at the expense of others or continue to marginalize people and places that may already possess situational vulnerabilities that predispose them to be affected disproportionally by both disruptions and interventions.

Ultimately, the outcomes of comprehensive resilience research provide much more than a study of semantic issues that divide the literature base on this topic. The dynamic nature of resilience requires a flexible and inclusive operational definition to provide a roadmap relevant for all types of research on people, communities, and human systems [33] (p. 439). The conceptualization of resilience proposed in this work helps capitalize on the proliferation of AI-augmented tools to unify the currently fragmented evidence about resilience across disciplines. The result is a shared definition based on common terminology that can shape cross-disciplinary and applied research strategies in the future. If the conceptualization of resilience remains fragmented, especially given available tools to synthesize meaning and interventions across multiple perspectives, the term resilience and its underlying structure run the risk of ongoing fragmentation at best and obsolescence at worst. Progress in the consistent application of resilience is likely to improve the accessibility of sustainable solutions aimed at enhancing resilience across various contexts. This approach serves as a more pertinent method for achieving gradual and beneficial changes over time in addressing complex issues related to well-being.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.E. and M.M.V.; data curation, E.E. and M.E.T.; formal analysis, E.E. and M.E.T.; funding acquisition, M.M.V.; investigation, E.E. and M.E.T.; methodology, E.E. and M.E.T.; project administration, E.E.; resources, M.M.V.; software, E.E. and M.E.T.; supervision, M.M.V.; validation, E.E. and M.E.T.; visualization, E.E. and M.E.T.; writing—original draft, E.E. and M.E.T.; writing—review and editing, E.E., M.E.T. and M.M.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding for this research was provided by the Community Health and Economic Resilience Research Center of Excellence at Texas State University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. Ethical approval for this type of study is not required by the institute of the authors. Per the review of the institute’s Integrity and Compliance department conducted on 12 July 2024, the project did not fulfill the criteria of ‘human subject’ and is not regulated by US federal policy, 45 CFR § 46.102. Therefore, the project did not require review from the Institutional Review Board.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data were consolidated from an open-access indexing database via a publicly available API. Source code is openly available for review and reproduction on GitHub (https://github.com/MariaElise-T/ResilienceConceptualization (accessed on 9 April 2024)). Other applications, tools, software settings, and approaches are detailed sufficiently clearly within the manuscript for reproduction.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Lauren Lee for the thoughtful comments and suggestions during the editing process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

List of all concepts with associated counts and relevance statistics.

Table A1.

List of all concepts with associated counts and relevance statistics.

| Concept | Count | Relevance (%) |

|---|---|---|

| resilience | 104,000 | 64 |

| system | 13,306 | 8 |

| change | 12,753 | 8 |

| health | 12,230 | 8 |

| factors | 11,926 | 7 |

| social | 11,218 | 7 |

| level | 10,683 | 7 |

| community | 10,438 | 6 |

| model | 9889 | 6 |

| development | 9716 | 6 |

| climate | 9592 | 6 |

| effects | 9562 | 6 |

| stress | 8339 | 5 |

| different | 7536 | 5 |

| support | 7508 | 5 |

| risk | 6630 | 4 |

| psychological | 6556 | 4 |

| adapt | 6540 | 4 |

| increase | 6344 | 4 |

| impact | 6190 | 4 |

| process | 6109 | 4 |

| environment | 6053 | 4 |

| relationship | 6008 | 4 |

| management | 5895 | 4 |

| role | 5798 | 4 |

| strategies | 5789 | 4 |

| disaster | 5732 | 4 |

| low | 5582 | 3 |

| positive | 5543 | 3 |

| urban | 5353 | 3 |

| life | 5337 | 3 |

| areas | 5255 | 3 |

| coping | 5136 | 3 |

| supply | 4938 | 3 |

| economic | 4811 | 3 |

| important | 4735 | 3 |

| future | 4716 | 3 |

| events | 4692 | 3 |

| work | 4574 | 3 |

| challenges | 4570 | 3 |

| sustainability | 4407 | 3 |

| higher | 4389 | 3 |

| vulnerability | 4370 | 3 |

| family | 4328 | 3 |

| time | 4253 | 3 |

| potential | 4248 | 3 |

| framework | 4220 | 3 |

| performance | 4200 | 3 |

| resources | 4098 | 3 |

| related | 3934 | 2 |

| policies | 3899 | 2 |

| city | 3825 | 2 |

| capacity | 3806 | 2 |

| key | 3741 | 2 |

| children | 3656 | 2 |

| conditions | 3654 | 2 |

| people | 3621 | 2 |

| negative | 3593 | 2 |

| recovery | 3588 | 2 |

| response | 3556 | 2 |

| quality | 3544 | 2 |

| measures | 3519 | 2 |

| control | 3379 | 2 |

| local | 3343 | 2 |

| outcomes | 3343 | 2 |

| current | 3329 | 2 |

| network | 3293 | 2 |

| individuals | 3232 | 2 |

| physical | 3231 | 2 |

| information | 3186 | 2 |

| critical | 3175 | 2 |

| education | 3155 | 2 |

| emotional | 3134 | 2 |

| population | 3100 | 2 |

| well-being | 3003 | 2 |

| better | 2991 | 2 |

| global | 2971 | 2 |

| governance | 2960 | 2 |

| water | 2941 | 2 |

| knowledge | 2915 | 2 |

| learning | 2877 | 2 |

| women | 2873 | 2 |

| multiple | 2852 | 2 |

| influence | 2795 | 2 |

| intervention | 2777 | 2 |

| natural | 2749 | 2 |

| planning | 2704 | 2 |

| growth | 2680 | 2 |

| food | 2596 | 2 |

| scale | 2439 | 2 |

| cognitive | 2436 | 2 |

| infrastructure | 2404 | 1 |

| species | 2394 | 1 |

| mechanisms | 2321 | 1 |

| number | 2216 | 1 |

| disease | 2183 | 1 |

| major | 2155 | 1 |

| ecological | 2112 | 1 |

| perspective | 2075 | 1 |

| financial | 2056 | 1 |

| power | 2037 | 1 |

| structure | 2035 | 1 |

| extreme | 2015 | 1 |

| healthcare | 1980 | 1 |

| energy | 1922 | 1 |

| adversity | 1843 | 1 |

| ecosystem | 1839 | 1 |

| satisfaction | 1823 | 1 |

| resistance | 1714 | 1 |

| production | 1711 | 1 |

| mediating | 1680 | 1 |

| loss | 1660 | 1 |

| leadership | 1634 | 1 |

| exposure | 1571 | 1 |

| gender | 1566 | 1 |

| world | 1529 | 1 |

| stability | 1401 | 1 |

| region | 1276 | 1 |

| forward | 520 | 0 |

| return | 484 | 0 |

| bounce | 372 | 0 |

| equilibrium | 212 | 0 |

| TAGS/TimeCluster | ||

| 2020≤ | 161,532 | 100 |

| 2010_19 | 59,206 | 37 |

| 2000_09 | 6315 | 4 |

| <2000 | 1384 | 1 |

Table A2.

List of all co-occurring resilience concepts with associated counts and likelihood statistics.

Table A2.

List of all co-occurring resilience concepts with associated counts and likelihood statistics.

| Concept | Co-Concept | Count | Likelihood (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| resilience | mediating | 1597 | 95 |

| resilience | relationship | 5259 | 88 |

| resilience | psychological | 5417 | 83 |

| resilience | satisfaction | 1353 | 74 |

| resilience | role | 4288 | 74 |

| resilience | bounce | 274 | 74 |

| resilience | well-being | 2203 | 73 |

| resilience | coping | 3758 | 73 |

| resilience | adversity | 1344 | 73 |

| resilience | positive | 4037 | 73 |

| resilience | perspective | 1507 | 73 |

| resilience | framework | 3016 | 71 |

| resilience | leadership | 1165 | 71 |

| resilience | support | 5308 | 71 |

| resilience | sustainability | 3098 | 70 |

| resilience | emotional | 2199 | 70 |

| resilience | capacity | 2626 | 69 |

| resilience | influence | 1928 | 69 |

| resilience | factors | 8165 | 68 |

| resilience | family | 2944 | 68 |

| resilience | supply | 3326 | 67 |

| resilience | social | 7548 | 67 |

| resilience | strategies | 3894 | 67 |

| resilience | urban | 3543 | 66 |

| resilience | resistance | 1133 | 66 |

| resilience | level | 7015 | 66 |

| resilience | adapt | 4255 | 65 |

| resilience | ecological | 1363 | 65 |

| resilience | mechanisms | 1476 | 64 |

| resilience | stress | 5279 | 63 |

| resilience | better | 1886 | 63 |

| resilience | life | 3336 | 63 |

| resilience | effects | 5905 | 62 |

| resilience | planning | 1663 | 62 |

| resilience | outcomes | 2054 | 61 |

| resilience | community | 6347 | 61 |

| resilience | process | 3702 | 61 |

| resilience | work | 2765 | 60 |

| resilience | related | 2373 | 60 |

| resilience | quality | 2133 | 60 |

| resilience | economic | 2892 | 60 |

| resilience | negative | 2150 | 60 |

| resilience | system | 7920 | 60 |

| resilience | management | 3496 | 59 |

| resilience | current | 1973 | 59 |

| resilience | development | 5738 | 59 |

| resilience | disaster | 3378 | 59 |

| resilience | important | 2787 | 59 |

| resilience | learning | 1692 | 59 |

| resilience | cognitive | 1429 | 59 |

| resilience | key | 2189 | 59 |

| resilience | knowledge | 1704 | 58 |

| resilience | performance | 2450 | 58 |

| resilience | gender | 911 | 58 |

| resilience | critical | 1847 | 58 |

| resilience | resources | 2381 | 58 |

| resilience | infrastructure | 1395 | 58 |

| resilience | city | 2219 | 58 |

| resilience | low | 3199 | 57 |

| resilience | financial | 1176 | 57 |

| resilience | individuals | 1848 | 57 |

| resilience | impact | 3508 | 57 |

| resilience | health | 6891 | 56 |

| resilience | potential | 2375 | 56 |

| resilience | risk | 3688 | 56 |

| resilience | future | 2603 | 55 |

| resilience | policies | 2151 | 55 |

| resilience | measures | 1937 | 55 |

| resilience | children | 2008 | 55 |

| resilience | environment | 3322 | 55 |

| resilience | vulnerability | 2392 | 55 |

| resilience | forward | 283 | 54 |

| resilience | higher | 2386 | 54 |

| resilience | education | 1705 | 54 |

| resilience | physical | 1728 | 53 |

| resilience | governance | 1583 | 53 |

| resilience | scale | 1302 | 53 |

| resilience | recovery | 1905 | 53 |

| resilience | network | 1736 | 53 |

| resilience | ecosystem | 962 | 52 |

| resilience | model | 5157 | 52 |

| resilience | different | 3882 | 52 |

| resilience | local | 1722 | 52 |

| resilience | increase | 3246 | 51 |

| resilience | equilibrium | 108 | 51 |

| resilience | challenges | 2317 | 51 |

| resilience | healthcare | 1003 | 51 |

| resilience | intervention | 1404 | 51 |

| resilience | response | 1791 | 50 |

| resilience | stability | 698 | 50 |

| resilience | return | 240 | 50 |

| resilience | exposure | 777 | 49 |

| resilience | climate | 4637 | 48 |

| resilience | power | 978 | 48 |

| resilience | change | 6068 | 48 |

| resilience | multiple | 1356 | 48 |

| resilience | women | 1361 | 47 |

| resilience | conditions | 1729 | 47 |

| resilience | growth | 1268 | 47 |

| resilience | people | 1701 | 47 |

| resilience | events | 2186 | 47 |

| resilience | natural | 1255 | 46 |

| resilience | structure | 929 | 46 |

| resilience | food | 1183 | 46 |

| resilience | information | 1439 | 45 |

| resilience | control | 1519 | 45 |

| resilience | disease | 977 | 45 |

| resilience | time | 1898 | 45 |

| resilience | energy | 853 | 44 |

| resilience | areas | 2325 | 44 |

| resilience | region | 560 | 44 |

| resilience | global | 1288 | 43 |

| resilience | major | 889 | 41 |

| resilience | population | 1254 | 40 |

| resilience | loss | 667 | 40 |

| resilience | water | 1146 | 39 |

| resilience | extreme | 781 | 39 |

| resilience | production | 646 | 38 |

| resilience | number | 812 | 37 |

| resilience | world | 541 | 35 |

| resilience | species | 828 | 35 |

Appendix B

Table A3.

Crossref ten most cited articles per decade.

Table A3.

Crossref ten most cited articles per decade.

| Article Title | Journal | Year | Times Cited | Discipline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resilience and stability of ecological systems | Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics | 1973 | 10,038 | Systems ecology |

| Catastrophes and resilience of a zero-dimensional climate system with ice-albedo and greenhouse feedback | Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society | 1979 | 48 | Systems ecology |

| Rebound resilience of tendons in the feet of sheep | Journal of Experimental Biology | 1978 | 17 | Biology |

| Polyurethane elastomer as a possible resilient material for denture protheses: A microbiological evaluation | Journal of Dental Research | 1975 | 16 | Engineering/materials science |

| Analysis of an all-metallic resilient pad gas-lubricated thrust bearing | Journal of Lubrication Technology | 1975 | 9 | Engineering/materials science |

| The effect of certain fiber properties on bulk compressional resilience of some man-made fibers | Textile Research Journal | 1973 | 7 | Engineering/materials science |

| Torsion resilience pendulum * | Rubber Chemistry and Technology | 1970 | 3 | Engineering/materials science |

| Metallurgical characterization of high resilience stainless steel orthodontic wires | Journal of Applied Chemistry and Biotechnology | 1975 | 3 | Engineering/materials science |

| Development of resilience and retention of strength and abrasion resistance in durable-press-treated flame-retardant cotton fabrics | Textile Research Journal | 1977 | 3 | Engineering/materials science |

| A cantilever mounted resilient pad gas thrust bearing | Journal of Lubrication Technology | 1977 | 2 | Engineering/materials science |

| Reliability, resiliency, and vulnerability criteria for water resource system performance evaluation | Water Resources Research | 1982 | 1215 | Systems ecology/marine science |

| Combat experience and emotional health: Impairment and resilience in later life | Journal of Personality | 1989 | 247 | Psychology |

| Early successional pathways and the resistance and resilience of forest communities | Ecology | 1988 | 218 | Systems ecology |

| Maltreated infants: Vulnerability and resilience | Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry | 1985 | 199 | Psychology/child development |

| Energy flow, nutrient cycling, and ecosystem resilience | Ecology | 1980 | 198 | Systems ecology |

| A programming model for analysis of the reliability, resilience, and vulnerability of a water supply reservoir | Water Resources Research | 1986 | 189 | Systems ecology/marine science |

| Dynamics of resilient-friction base isolator (R-FBI) | Earthquake Engineering and Structural Dynamics | 1987 | 161 | Engineering/materials science |

| Alternative indices of resilience | Water Resources Research | 1982 | 72 | Systems ecology/marine science |

| Ordination analysis of components of resilience of Quercus Coccifera Garrigue | Ecology | 1987 | 53 | Systems ecology |

| Vulnerability and resilience in adolescence: Views from the family | The Journal of Early Adolescence | 1985 | 51 | Psychology/child development |

| Resilience and development: Contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity | Development and Psychopathology | 1990 | 1756 | Psychology |

| Competence in the context of adversity: Pathways to resilience and maladaptation from childhood to late adolescence | Development and Psychopathology | 1999 | 632 | Psychology |

| Resilience as process | Development and Psychopathology | 1993 | 571 | Psychology |

| Resilience and thriving: Issues, models, and linkages | Journal of Social Issues | 1998 | 558 | Psychology |

| Resilience concepts and findings: Implications for family therapy | Journal of Family Therapy | 1999 | 472 | Psychology |

| The concept of family resilience: Crisis and challenge | Family Process | 1996 | 404 | Psychology |

| The Emanuel Miller Memorial lecture 1992: The theory and practice of resilience | Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry | 1994 | 380 | Psychology/child development |

| Conserving biological diversity through ecosystem resilience | Conservation Biology | 1995 | 346 | Systems ecology |

| The role of self-organization in the promotion of resilience in maltreated children | Development and Psychopathology | 1997 | 311 | Psychology |

| The adjustment of children with divorced parents: A risk and resiliency perspective | Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry | 1999 | 268 | Psychology/child development |

| The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work | Child Development | 2000 | 4707 | Psychology/child development |

| A framework to quantitatively assess and enhance the seismic resilience of communities | Earthquake Spectra | 2003 | 2948 | Engineering/materials science |

| Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness | American Journal of Community Psychology | 2007 | 2701 | Psychology |

| Climate change, human impacts, and the resilience of coral reefs | Science | 2003 | 2648 | Systems ecology/marine science |

| Social and ecological resilience: are they related? | Progress in Human Geography | 2000 | 2637 | Human geography |

| Regime shifts, resilience, and biodiversity in ecosystem management | Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics | 2004 | 2404 | Systems ecology |

| Resilience in the face of catastrophe: Optimism, personality, and coping in the Kosovo crisis | Journal of Applied Social Psychology | 2002 | 1962 | Psychology |

| A resilient, low-frequency, small-world human brain functional network with highly connected association cortical hubs | The Journal of Neuroscience | 2006 | 1938 | Psychology/neuroscience |

| Resistance, resilience, and redundancy in microbial communities | Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences | 2008 | 1933 | Systems ecology/microbiology |

| Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-item measure of resilience | Journal of Traumatic Stress | 2007 | 1728 | Psychology |

| Psychological resilience | European Psychologist | 2013 | 1238 | Psychology |

| Social capital and community resilience | American Behavioral Scientist | 2014 | 993 | Psychology |

| Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population | American Journal of Public Health | 2013 | 980 | Psychology |

| Resilience as a dynamic concept | Development and Psychopathology | 2012 | 896 | Psychology |

| What is resilience? A review and concept analysis | Reviews in Clinical Gerontology | 2010 | 894 | Psychology |

| Changing disturbance regimes, ecological memory, and forest resilience | Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment | 2016 | 865 | Systems ecology |

| Global Perspectives on resilience in children and youth | Child Development | 2013 | 787 | Psychology/child development |

| Resilience in business and management research: A review of influential publications and a research agenda | International Journal of Management Reviews | 2015 | 753 | Business management |

| Ensuring supply chain resilience: Development of a conceptual framework | Journal of Business Logistics | 2010 | 753 | Business management |

| Toward principles for enhancing the resilience of ecosystem services | Annual Review of Environment and Resources | 2012 | 726 | Systems ecology |

| Research opportunities for a more resilient post-COVID-19 supply chain: Closing the gap between research findings and industry practice | International Journal of Operations & Production Management | 2020 | 490 | Business management |

| Resiliency of environmental and social stocks: An analysis of the exogenous COVID-19 market crash | The Review of Corporate Finance Studies | 2020 | 472 | Business management |

| Introducing the 15-min city: Sustainability, resilience and place identity in future post-pandemic cities | Smart Cities | 2021 | 465 | Urban studies |

| Viable supply chain model: integrating agility, resilience and sustainability perspectives, lessons from and thinking beyond the COVID-19 pandemic | Annals of Operations Research | 2020 | 421 | Business management |

| Harnessing rhizosphere microbiomes for drought-resilient crop production | Science | 2020 | 416 | Systems ecology |

| Resilience of local food systems and links to food security: A review of some important concepts in the context of COVID-19 and other shocks | Food Security | 2020 | 408 | Systems ecology/food security |

| Resilience, COVID-19-related stress, anxiety and depression during the pandemic in a large population enriched for healthcare providers | Translational Psychiatry | 2020 | 384 | Psychology |

| Symptoms of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, depression, levels of resilience and burnout in Spanish health personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | 2020 | 381 | Psychology |

| Resilience strategies to manage psychological distress among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A narrative review | Anaesthesia | 2020 | 316 | Psychology |

| Shape adaptable and highly resilient 3D braided triboelectric nanogenerators as e-textiles for power and sensing | Nature Communications | 2020 | 270 | Engineering/materials science |

* Note. This paper was not included in the conceptual analysis, as it pre-dated 1973.

References

- Mayar, K.; Carmichael, D.G.; Shen, X. Resilience and systems: A review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downes, B.J.; Miller, F.; Barnett, J.; Glaister, A.; Ellemor, H. How do we know about resilience? An analysis of empirical research on resilience, and implications for interdisciplinary praxis. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 14041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, F.S.; Jax, K. Focusing the Meaning(s) of Resilience: Resilience as a descriptive concept and a boundary object. Ecol. Soc. 2007, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, H.B. Understanding the concept of resilience. In Handbook of Resilience in Children; Goldstein, S., Brooks, R.B., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Huang, W.; Bu, Y. Interdisciplinary research attracts greater attention from policy documents: Evidence from COVID-19. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundstrom, S.M.; Angeler, D.G.; Bell, J.; Hayes, M.; Hodbod, J.; Jalalzadeh-Fard, B.; Mahmood, R.; VanWormer, E.; Allen, C.R. Panarchy theory for convergence. Sustain. Sci. 2023, 18, 1667–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwick, S.M.; Bonanno, G.A.; Masten, A.S.; Panter-Brick, C.; Yehuda, R. Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: Interdisciplinary perspectives. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2014, 5, 25338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyena, S.B.; Gordon, S. Bridging the concepts of resilience, fragility and stabilisation. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2015, 24, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aburn, G.; Gott, M.; Hoare, K. What is resilience? An integrative review of the empirical literature. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 980–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafer, A.; Green, J.; Goreham, G. A community resilience framework for community development practitioners building equity and adaptive capacity. Community Dev. 2019, 50, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisto, A.; Vicinanza, F.; Campanozzi, L.L.; Ricci, G.; Tartaglini, D.; Tambone, V. Towards a Transversal Definition of Psychological Resilience: A Literature Review. Medicina 2019, 55, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1973, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.; Salt, D. Resilience Thinking: Sustaining Ecosystems and People in a Changing World; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Garmestani, A.S.; Benson, M.H. A framework for resilience-based governance of social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.; Cooper, M. Genealogies of resilience: From systems ecology to the political economy of crisis adaptation. Secur. Dialogue 2011, 42, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]