Analysis of the Causes and Configuration Paths of Explosion Accidents in Chemical Companies Based on the REASON Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

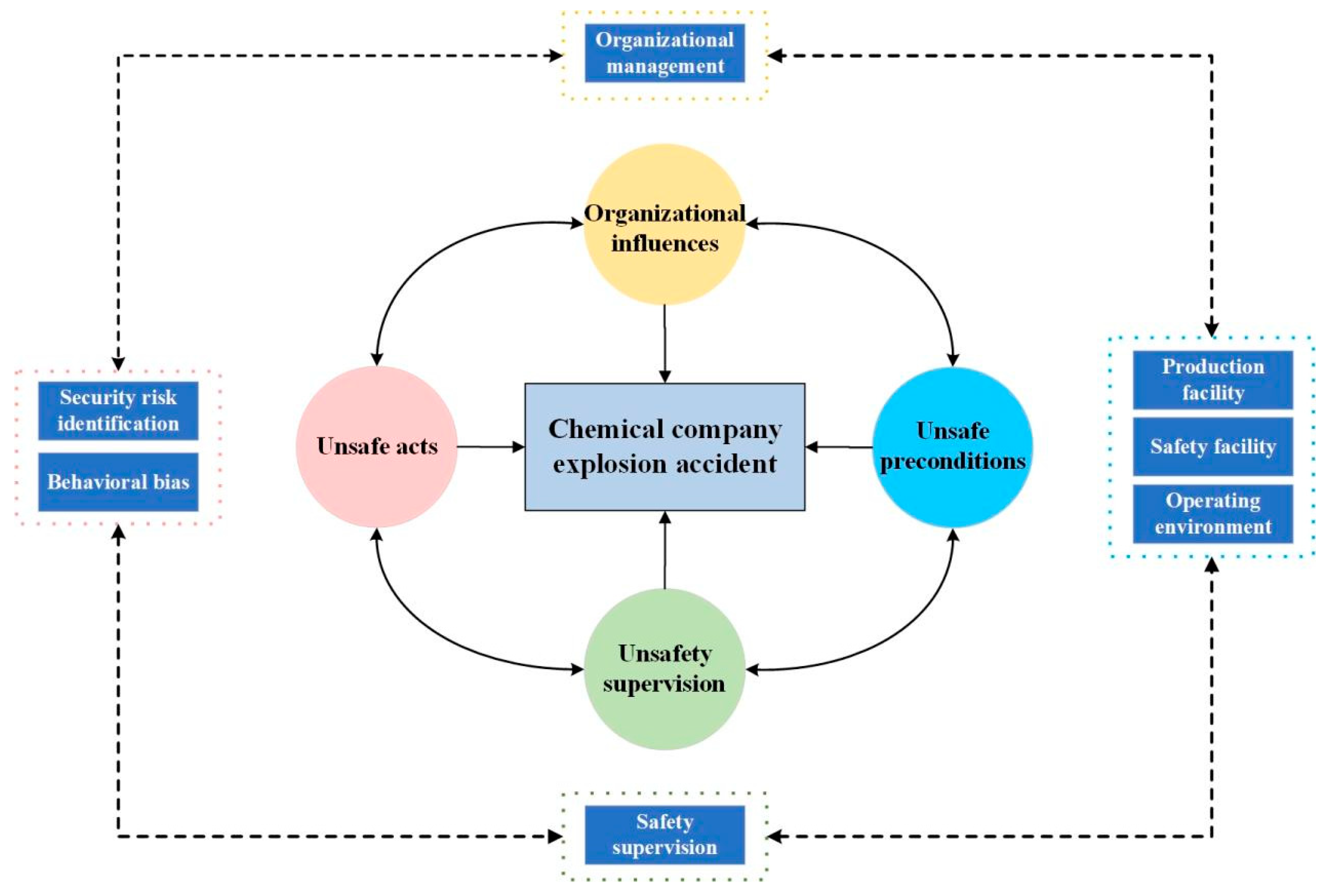

2. Research Framework

3. Analysis of the Causes of Explosions in Chemical Company

3.1. Methods

3.2. Case Selection

3.3. Variable Selection and Assignment

3.4. Results and Discussion

3.4.1. Analysis of the Necessary Conditions for Chemical Explosion Accidents

3.4.2. Analysis of Conditional Configurations for Chemical Explosion Accidents

- (1)

- Organizational management deficiencies type.

- (2)

- Supervision deficiency type.

- (3)

- Behavioral–risk linkage type.

3.4.3. Robustness Test

4. Measures to Prevent Chemical Explosion Accidents

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bai, M.; Qi, M.; Shu, C.M.; Reniers, G.; Khan, F.; Chen, C.; Liu, Y. Why do major chemical accidents still happen in China: Analysis from a process safety management perspective. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 176, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R. Analysis of production safety accidents in chemical companies from 2000 to 2020. Plast. Ind. 2023, 51, 17–22+78. [Google Scholar]

- Darbra, R.M.; Palacios, A.; Casal, J. Domino effect in chemical accidents: Main features and accident sequences. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 183, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Wu, C.; Reniers, G.; Huang, L.; Kang, L.; Zhang, L. The future of hazardous chemical safety in China: Opportunities, problems, challenges and tasks. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 643, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Xiao, L.; Lin, Y.; Yuan, D.; Wang, J. A statistical analysis of hazardous chemical fatalities (HCFs) in China between 2015 and 2021. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcin, E.; Ciftcioglu, G.A.; Guzel, B.H. Human factors analysis by classifying chemical accidents into operations. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Woo, J.; Kang, C. Analysis of severe industrial accidents caused by hazardous chemicals in South Korea from January 2008 to June 2018. Saf. Sci. 2020, 124, 104580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wei, L.; Wang, K.; Duo, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhang, S.; Su, M.; Zeng, T. Exploring human factors of major chemical accidents in China: Evidence from 160 accidents during 2011–2022. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2024, 89, 105279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Fu, G.; Yan, M. Investigation and analysis of a hazardous chemical accident in the process industry: Triggers, roots, and lessons learned. Processes 2020, 8, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonyora, M.; Ventura-Medina, E. Investigating the relationship between human and organisational factors, maintenance, and accidents. The case of chemical process industry in South Africa. Saf. Sci. 2024, 176, 106530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niciejewska, M.; Idzikowski, A.; Škurková, K.L. Impact of technical, organizational and human factors on accident rate of small-sized enterprises. Manag. Syst. Prod. Eng. 2021, 29, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.W.; Yao, H.Q.; Wu, T.C. Applying data mining techniques to analyze the causes of major occupational accidents in the petrochemical industry. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2013, 26, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidam, K.; Hurme, M. Analysis of equipment failures as contributors to chemical process accidents. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2013, 91, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, D.; Wu, C. Characteristics of hazardous chemical accidents during hot season in China from 1989 to 2019: A statistical investigation. Saf. Sci. 2020, 129, 104788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.C.; Sun, X.; Li, Y.F.; Zhu, X.D. Analysis on the spatial and temporal change of chemical accidents and its suggestions: A case study in coastal areas of Jiangsu Province. China Saf. Sci. J. 2010, 20, 129–135. [Google Scholar]

- Dakkoune, A.; Vernières-Hassimi, L.; Leveneur, S.; Lefebvre, D.; Estel, L. Risk analysis of French chemical industry. Saf. Sci. 2018, 105, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Li, Y.; Zhou, J.; Huang, Z.; Wu, Z. Comparative study of the hazardous chemical transportation accident analyses using the CREAM model and the 24 Model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikwan, F.; Sanders, D.; Hassan, M. Safety evaluation of leak in a storage tank using fault tree analysis and risk matrix analysis. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2021, 73, 104597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Fan, Y.; Niu, Y. Routes to failure: Analysis of chemical accidents using the HFACS. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2022, 75, 104695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, C.; Yang, F.Q. Exploring hazardous chemical explosion accidents with association rules and Bayesian networks. Reliab. Eng. Sys. Saf. 2023, 233, 109099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholamizadeh, K.; Alauddin, M.; Aliabadi, M.M.; Soltanzade, A.; Mohammadfam, I. Comprehensive failure analysis in Tehran Refinery Fire accident: Application of AcciMap methodology and quantitative domino effect analysis. Fire Technol. 2023, 59, 453–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Song, B.D. Causation chain analysis on explosion accident of chemical process based on HCNAM-BN. J. Saf. Sci. Technol. 2017, 13, 145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.Y.; Wang, T.Y.; Liang, Y.Q.; Qu, L.N.; Li, P. Analysis on human factors of fire and explosion accidents in chemical companies based on HFACS. J. Saf. Sci. Technol. 2020, 16, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Reason, J. Human Error; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, X.F.; Zhu, M.J. Analysis on influencing factors and configuration paths of human-caused accidents in coal mines. Saf. Coal Mines 2023, 54, 245–250. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.Q.; Pan, J.; Zhang, Z.C. Effects of the interaction among civil aviation unsafe factors to air crash: A crisp-set qualitative comparative analysis of 45 cases. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2020, 20, 11809–11817. [Google Scholar]

- Fiss, P.C. Building better causal theories: A fuzzy set approach to typologies in organization research. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 393–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A.; Elman, C. Qualitative research: Recent developments in case study methods. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2006, 9, 455–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Fu, G.; Yan, M. Comparative analysis of two catastrophic hazardous chemical accidents in China. Process Saf. Prog. 2020, 39, e12137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbar, H.A.; Shinohara, S.; Shimada, Y.; Suzuki, K. Experiment on distributed dynamic simulation for safety design of chemical plants. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2003, 11, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinodkumar, M.N.; Bhasi, M.J.S.S. Safety climate factors and its relationship with accidents and personal attributes in the chemical industry. Saf. Sci. 2009, 47, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, X. Research on Safety Regulation of chemical company under third-party mechanism: An evolutionary approach. Symmetry 2019, 11, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theophilus, S.C.; Esenowo, V.N.; Arewa, A.O.; Ifelebuegu, A.O.; Nnadi, E.O.; Mbanaso, F.U. Human factors analysis and classification system for the oil and gas industry (HFACS-OGI). Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2017, 167, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuselman, I.; Pennecchi, F.; Fajgelj, A.; Karpov, Y. Human errors and reliability of test results in analytical chemistry. Accredit. Qual. Assur. 2013, 18, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Lu, B.; Zhong, Y. Driving factors of urban community epidemic prevention and control capability: QCA analysis based on typical cases of 20 anti-epidemic communities in China. Front. Public Health 2024, 11, 1296269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.Q.; Wagemann, C. Set-Theoretic Methods for the Social Sciences: A Guide to Qualitative Comparative Analysis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 231–245. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, F.; Fu, C. Generation paths of major production safety accidents—A fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis based on Chinese data. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1136640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lu, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhou, A. Research on the Effective Reduction of Accidents on Operating Vehicles with fsQCA Method—Case Studies. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.H.; Shi, Y.Q.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, W.H.; Fu, G. Comparative study of systematic analysis on accident causes based on 24Model and accident investigation reports:taking Xiangshui explosion accident as an example. China Saf. Sci. J. 2022, 32, 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi, F.; Khoshmanesh zadeh, B.; Fatemi, F.; Gilani, N.; Alizadeh, S.S. Effective parameters on chemical accidents occurrence: Findings from a systematic review. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2020, 20, 1184–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Reniers, G. Chemical industry in China: The current status, safety problems, and pathways for future sustainable development. Saf. Sci. 2020, 128, 104741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S/N | Title of Accident Case | Date | Property Loss/Million Yuan | Casualties/Person |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Special Major Accident of “ November 22” Sinopec Donghuang Oil Pipeline Leakage and Explosion in Qingdao, China | 22 November 2013 | 75,000 | Deaths: 62 Injuries: 136 |

| 2 | Tangshan Kailuan Chemical Co., Ltd., “3.7” Major Explosion Accident, in Tangshan, China | 7 March 2014 | 1526.5 | Deaths: 13 Injuries: 0 |

| 3 | Major accident of “4–6” explosion at Tenglong Aromatic Hydrocarbons (Zhangzhou) Co., Ltd. in Zhangzhou, China | 6 April 2015 | 9457 | Deaths: 0 Injuries: 6 |

| 4 | Ningtai Chemical Co., Ltd. “4–13” general explosion accident in Taizhou, China | 13 April 2016 | 2.5 | Deaths: 0 Injuries: 1 |

| 5 | Zhejiang Huabang Pharmaceutical and Chemical Co., Ltd. “1–3” large explosive accident in Taizhou, China | 3 January 2017 | 400 | Deaths: 3 Injuries: 0 |

| 6 | Zhejiang Linjiang Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. “6–9” explosion in Hangzhou, China | 9 June 2017 | 525 | Deaths: 3 Injuries: 1 |

| 7 | “12.9” Major Explosion Accident of Juxin Biotechnology Co., Ltd. in Lianyungang, China | 9 December 2017 | 4875 | Deaths: 10 Injuries: 1 |

| 8 | Sichuan Yibin Hengda Technology Co., Ltd. “7–12” major explosion accident in Yibin, China | 12 July 2018 | 4142 | Deaths: 19 Injuries: 12 |

| 9 | The “11–28” Major Deflagration Accident at Shenghua Chemical Company of China National Chemical Corporation in Zhangjiakou, China | 28 November 2018 | 4148.9 | Deaths: 24 Injuries: 22 |

| 10 | Jiangsu Tianjia Yihua Co., Ltd. “3–21” particularly significant explosion accident in Xiangshui County, Jiangsu Province | 21 March 2019 | 198,635.1 | Deaths: 78 Injuries: 716 |

| 11 | Anhui Bayi Chemical Co., Ltd.’s “7.13” flash explosion accident in Bengbu, China | 13 July 2019 | 300 | Deaths: 2 Injuries: 0 |

| 12 | The “7–19” major explosion of Henan Gas Group’s Yima Gasification Plant in Sanmenxia, China | 19 July 2019 | 8170.1 | Deaths: 15 Injuries: 16 |

| 13 | Zhongwei United Xinli Chemical Co., Ltd. “8–29” Gas Furnace Explosion Accident in Zhongwei, China | 29 August 2019 | 700 | Deaths: 4 Injuries: 3 |

| 14 | Jiangsu Kailong Aluminum Industry Co., Ltd. “10–31” major explosion accident in Changshu City, Jiangsu Province | 31 October 2019 | 817 | Deaths: 4 Injuries: 2 |

| 15 | Hongye Biotechnology Co., Ltd. “4–8” explosion accident in Puyang, China | 8 April 2020 | 200 | Deaths: 1 Injuries: 2 |

| 16 | Yueyi biomass fuel processing plant “4–15” flash explosion accident in Meizhou, China | 15 April 2020 | 180 | Deaths: 0 Injuries: 2 |

| 17 | Zhongke (Guangdong) Refining and Chemical Co., Ltd. “9–19” flash explosion accident in Zhanjiang, China | 19 September 2020 | 300 | Deaths: 1 Injuries: 2 |

| 18 | Tianmen Chutian Biotechnology Co., Ltd. 9–28” explosion accident in Tianmen, China | 28 September 2020 | 542 | Deaths: 6 Injuries: 1 |

| 19 | Haizhou Pharmaceutical and Chemical Co., Ltd. “11–17” large-scale explosion accident in Jian, China | 17 November 2020 | 1000 | Deaths: 3 Injuries: 5 |

| 20 | Anda Hainabelle Chemical Co., Ltd. “12–19” emulsifying kettle explosion large accident in Anda, China | 19 December 2020 | 2405 | Deaths: 3 Injuries: 4 |

| 21 | Taizhou Mingfeng Resource Renewable Technology Co., Ltd. “12–22” large explosion and combustion accident in Taizhou, China | 22 December 2020 | 773 | Deaths: 3 Injuries: 1 |

| 22 | Huayang Dyeing and Finishing Company Limited “2–25” large explosion accident in Fuzhou, China | 25 February 2021 | 665 | Deaths: 6 Injuries: 7 |

| 23 | Hubei Xianlong Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. “2–26” large-scale explosion accident in Xiantao, China | 26 February 2021 | 484.9 | Deaths: 4 Injuries: 4 |

| 24 | Dajin Energy Co., Ltd.’s “5.9” liquefied petroleum gas cylinder major explosion accident in Fuzhou, China | 9 May 2021 | 495 | Deaths: 4 Injuries: 1 |

| 25 | Jiangxi Hongcheng Chemical Co., Ltd. “7–27” explosion accident in Jiujiang, China | 27 July 2021 | 112 | Deaths: 1 Injuries: 0 |

| 26 | Dalian Kunma Gas Co., Ltd.’s “9.10” major pipeline liquefied petroleum gas leakage and explosion accident in Dalian, China | 10 September 2021 | 1797.5 | Deaths: 9 Injuries: 4 |

| 27 | Inner Mongolia Zhonggao Chemical Co., Ltd. “10–22” explosion accident in Alxa, China | 22 October 2021 | 795 | Deaths: 4 Injuries: 3 |

| 28 | Linfen Dyeing and Chemical Group Co., Ltd. “12 · 28” explosion accident in Linfen, China | 28 December 2021 | 831 | Deaths: 4 Injuries: 0 |

| 29 | Henan Yutian Chemical Co., Ltd. “1–5” large-scale explosion accident in Anyang, China | 5 January 2022 | 547.9 | Deaths: 3 Injuries: 0 |

| 30 | Shanghai Petrochemical Co., Ltd. “6–18” 1 # ethylene glycol plant explosion accident in Shanghai, China | 18 June 2022 | 971.5 | Deaths: 1 Injuries: 1 |

| Categories | Name | Assignment Rules | Assignment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable | Status of accidents | Accident results (AR) | 1. Particularly major accident 2. Major accident 3. Serious accident 4. Ordinary accident | Particularly major accidents are assigned a value of 1. Major accidents are assigned a value of 0.67. Serious accidents are assigned a value of 0.33. Ordinary accidents are assigned a value of 0. |

| Conditional variables | Organizational influences | Organizational management (OM) | 1. Absence of on-site operational safety management 2. Unclear safety responsibility system 3. Organization of production operations in violation of the law 4. Deficiencies in production safety rules and regulations | All four conditions are assigned a value of 1; three of the conditions are assigned a value of 0.67; two of the conditions are assigned a value of 0.33; any one of the conditions is assigned a value of 0. |

| Unsafe preconditions | Production facility (PF) | 1. Defects or quality problems in production facilities, equipment and processes 2. Damage to equipment due to lack of maintenance or inadequate maintenance | Both conditions are assigned a value of 1; condition 1 is assigned a value of 0.67; condition 2 is assigned a value of 0.33; and neither condition is assigned a value of 0. | |

| Safety facility (SF) | 1. Lack of or ineffective safety precautions 2. Not mentioned in the accident investigation report | Condition 1 is assigned a value of 1; condition 2 is assigned a value of 0. | ||

| Operating environment (OE) | 1. Poor environment of the operation site 2. Not mentioned in the accident investigation report | Condition 1 is assigned a value of 1; condition 2 is assigned a value of 0. | ||

| Unsafety supervision | Safety supervision (SS) | 1. Lack of supervision by functional departments 2. Failure of local supervision | Both conditions are assigned a value of 1; condition 1 is assigned a value of 0.67; condition 2 is assigned a value of 0.33; and neither condition is assigned a value of 0. | |

| Unsafe acts | Security risk identification (SRI) | 1. Inadequate identification of risks and hazards 2. Weak security awareness | Both conditions are assigned a value of 1; condition 1 is assigned a value of 0.67; condition 2 is assigned a value of 0.33; and neither condition is assigned a value of 0. | |

| Behavioral deviation (BD) | 1. Illegal work or operational errors 2. Improper emergency response | Both conditions are assigned a value of 1; condition 1 is assigned a value of 0.67; condition 2 is assigned a value of 0.33; and neither condition is assigned a value of 0. | ||

| Accident Level | Division Criteria |

|---|---|

| Ordinary accident | The accident resulted in fewer than 3 deaths, fewer than 10 serious injuries, or direct economic damages of less than 10 million yuan. |

| Serious accident | The accident resulted in more than 3 but fewer than 10 deaths, more than 10 but fewer than 50 serious injuries, or a direct economic loss of more than 10 million yuan but less than 50 million yuan. |

| Major accident | The accident resulted in 10–30 deaths, 50–100 serious injuries, or a direct economic loss ranging from 50 million to 100 million yuan. |

| Particularly major accident | The accident resulted in 30 or more deaths, 100 or more serious injuries, or direct economic losses of 100 million yuan or more. |

| Conditional Variables | Consistency | Coverage |

|---|---|---|

| Organizational management (OM) | 0.908842 | 0.490650 |

| ~Organizational management (OM) | 0.211486 | 0.239669 |

| Production facility (PF) | 0.635369 | 0.653846 |

| ~Production facility (PF) | 0.815861 | 0.462771 |

| Safety facility (SF) | 0.637192 | 0.436875 |

| ~Safety facility (SF) | 0.362808 | 0.284286 |

| Operating environment (OE) | 0.364631 | 0.400000 |

| ~Operating environment | 0.635369 | 0.348500 |

| Safety supervision (SS) | 0.908842 | 0.490650 |

| ~Safety supervision (SS) | 0.211486 | 0.239669 |

| Security risk identification (SRI) | 0.908842 | 0.439014 |

| ~Security risk identification (SRI) | 0.422060 | 0.635117 |

| Behavioral deviation (BD) | 0.755697 | 0.477535 |

| ~Behavioral deviation (BD) | 0.665451 | 0.577532 |

| Conditional Variables | Configuration Solution | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path 1 | Path 2 | Path 3 | Path 4 | Path 5 | |

| Organizational management (OM) |  | ● | ● | ● |  |

| Production facility (PF) | ⊗ |  |  |  | ● |

| Safety facility (SF) | — |  |  | — | ● |

| Operating environment (OE) |  | — | ⊗ |  |  |

| Safety supervision (SS) | ● |  |  | ● | ● |

| Security risk identification (SRI) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ⊗ |

| Behavioral deviation (BD) |  | ⊗ | — |  |  |

| Original coverage | 0.361896 | 0.301732 | 0.301732 | 0.152233 | 0.12124 |

| Unique coverage | 0.181404 | 0.0610757 | 0.12124 | 0.0920693 | 0.0610757 |

| Consistency | 0.853763 | 0.906849 | 0.829574 | 1 | 1 |

| Total coverage | 0.75752 | ||||

| Total consistency | 0.890675 | ||||

signifies a core condition is present, while

signifies a core condition is present, while  indicates a core condition is missing; ● denotes an auxiliary condition is present, and ⊗ signifies an auxiliary condition is missing. — indicates that a condition may or may not be present.

indicates a core condition is missing; ● denotes an auxiliary condition is present, and ⊗ signifies an auxiliary condition is missing. — indicates that a condition may or may not be present.| Conditional Variables | Configuration Solution | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path 1 | Path 2 | Path 3 | Path 4 | Path 5 | |

| Organizational management |  |  | ● |  |  |

| Production facility | ⊗ |  |  |  |  |

| Safety facility | — |  |  | — |  |

| Operating environment |  | — | ⊗ |  |  |

| Safety supervision | ● |  |  | ● | ● |

| Security risk identification | ● | ● | ● | ● | ⊗ |

| Behavioral deviation |  | ⊗ | — |  |  |

| Original coverage | 0.353055 | 0.321048 | 0.321047 | 0.161979 | 0.129001 |

| Unique coverage | 0.161009 | 0.0649855 | 0.129001 | 0.0979632 | 0.0649855 |

| Consistency | 0.842593 | 0.906849 | 0.829574 | 1 | 1 |

| Total coverage | 0.774006 | ||||

| Total consistency | 0.886667 | ||||

signifies a core condition is present, while

signifies a core condition is present, while  indicates a core condition is missing; ● denotes an auxiliary condition is present, and ⊗ signifies an auxiliary condition is missing. — indicates that a condition may or may not be present.

indicates a core condition is missing; ● denotes an auxiliary condition is present, and ⊗ signifies an auxiliary condition is missing. — indicates that a condition may or may not be present.Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, C.; Lu, B.; Shi, R. Analysis of the Causes and Configuration Paths of Explosion Accidents in Chemical Companies Based on the REASON Model. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9845. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16229845

Wang C, Lu B, Shi R. Analysis of the Causes and Configuration Paths of Explosion Accidents in Chemical Companies Based on the REASON Model. Sustainability. 2024; 16(22):9845. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16229845

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Chao, Bo Lu, and Ruyi Shi. 2024. "Analysis of the Causes and Configuration Paths of Explosion Accidents in Chemical Companies Based on the REASON Model" Sustainability 16, no. 22: 9845. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16229845

APA StyleWang, C., Lu, B., & Shi, R. (2024). Analysis of the Causes and Configuration Paths of Explosion Accidents in Chemical Companies Based on the REASON Model. Sustainability, 16(22), 9845. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16229845