Abstract

Modular construction is emerging into the limelight in the construction industry as one of the front-running modern methods of construction, facilitating multiple benefits, including improved productivity. Meanwhile, Circular Economy (CE) principles are also becoming prominent in the Building Construction Industry (BCI), which is infamous for its prodigious resource consumption and waste generation. In essence, the basic concepts of modular construction and CE share some commonalities in their fundamental design principles, such as standardisation, simplification, prefabrication, and mobility. Hence, exploring ways of synergising circularity and modularity in the design stage with a Whole Life Cycle (WLC) of value creation and retention is beneficial. By conducting a thorough literature review, supported by expert interviews and brainstorming sessions, followed by a case study, the concept of Design for Circular Manufacturing and Assembly (DfCMA) was proposed to deliver circularity and modularity synergistically in circularity-oriented modular construction. This novel conceptualisation of DfCMA is envisaged to be a value-adding original theoretical contribution of this paper. Furthermore, the findings are expected to add value to the BCI by proposing a way forward to synergise circularity and modularity to contribute substantially towards an efficient circular built environment.

1. Introduction

Unrestrained consumption patterns and the population growth trends of humankind are exerting unprecedented pressure on the planet and its resources [1]. Hence, analogising Earth to a single spaceship with a cyclical ecological system, an economy capable of “continuous reproduction of material form even though it cannot escape having inputs of energy” was envisioned [2] (p. 8). Based on this ideation, the concept of Circular Economy (CE) is progressing as an alternative to the linear economy where resources are utilised as long as possible, and maximum value is exploited by reusing, recovering and regenerating at the end of their service lives [3]. CE intends to preserve product integrity at a higher technical and economic longevity and maximise product utilisation via value chains [4]. Accordingly, CE can be characterised as “an industrial system that is restorative and regenerative by intention and design” which aims to keep resources at their highest utility and value at all times [5] (p. 7).

The Building Construction Industry (BCI) is gaining attention as a priority in transitioning towards a CE, given its disreputable performance in energy consumption, Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions, excessive material extractions and wastage [6]. Furthermore, BCI is responsible for 35% of global energy consumption, 38% of carbon dioxide emissions, 40–50% of global material extraction and an annual material loss during construction and demolition of nearly 40% of mass when extracted (including, but not limited to concrete, bricks, gypsum, tiles, ceramics, wood, glass, metals, plastic, solvents, asbestos, and excavated soil) [7] (p. 48). Hence, CE transition is seen as the future imperative of BCI [8]. However, the CE transition in the BCI seems to be slow and inconsistent, questioning the understanding and readiness of the BCI for Design for Circularity (DfC) [9]. A CE that is restorative and regenerative by intention and design calls for DfC, which requires shifting design practices from object-centric thinking to a systematic design framework underpinning the systematic perspective of CE transition [10]. The systematic perspective of CE transition in the BCI aims to guarantee that buildings are designed for circularity with necessary system conditions, reverse cycles, and business models to ensure the value retention of production systems [11,12]. Hence, DfC can be introduced as a systems-thinking framework (based on Porter’s generic value chain notion) accommodating multi-criterion decision-making within an eco-system of stakeholders to create, develop and sustain circular value throughout the whole building life cycle to enable CE transition [13,14].

Even with the poor performance of the BCI, demand for its services is rising drastically, and it is now facing a deficit of 1.6 billion units in global housing demand, which is expected to increase by 3 billion by 2050 [15]. Aggravating the situation, it is predicted that 60% of the world’s population will be urbanised by 2030, which is anticipated to further increase to 70% by 2050 [16]. The study further envisions modular buildings as the “next generation of housing” as governments are now pivoting towards Off-Site Construction (OSC) methods as a possible solution to tackle these issues. The UK government advocates OSC and prefabrication to cater for approximately 5000 houses per year, or 3% of new housing [17]. The Modern Methods of Construction Taskforce (the MMC Taskforce) of the New South Wales Government in Australia is investing 10 million AUD in OSC and prefabrication as a part of their AUD 224 million Essential Housing Package Budget for the 2023–2024 financial year [18]. Based on the Construction Productivity Roadmap launched in 2011, Singapore continues to engage OSC and prefabrication methods as an efficient and wholesome means of improving productivity [19]. China is also promoting modular construction and prefabrication as a means of enhancing productivity, resource efficiency, and environmental performance, and it expects to reach 30% of new buildings that will be prefabricated within the next decade [20]. The 2023 Policy Address of Hong Kong established that the Modular Integrated Construction (MiC) approach will be employed in public housing to ensure better quality and expedited project delivery [21]. According to [22], 6% of all new construction projects use permanent modular construction, amounting to USD 12 billion in North America in 2022, while the total number of relocatable modular buildings in use is approximately 500,000.

Current modular building designs are primarily based on traditional buildings and need suitable design guidelines [16]. To address this shortcoming, Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DfMA) is increasingly proposed as a design framework to optimise and streamline modular building design processes [23]. DfMA originated initially in the manufacturing paradigm and provides a systematic methodology to evaluate and improve product design, considering the downstream activities of the manufacturing and assembly value chain [24]. Hence, it can be defined as a design approach that specialises in “the design for ease of manufacture of the collection of parts that will form the product after assembly” (Design for Manufacturing (DfM)) and “the design of the product for ease of assembly” (Design for Assembly (DfA)) [23,25].

DfMA is still emerging as a design approach in the field of modular construction in the BCI and is yet to achieve its full potential in embracing OSC technologies [26,27]. Regarding future directions of modular building design, incorporating sustainable design and construction techniques in modular construction is frequently emphasised [27,28]. This inclusion is critical as mass production can effectively influence the environmental impacts throughout the Whole Life Cycle (WLC) of a building [29]. Even though ‘sustainability of modular construction’ and ‘sustainable modular building design’ are widely discussed in the BCI [29,30,31], topics such as ‘circularity of modular construction’ and ‘circular modular design and construction’ are seldom mentioned [4,32]. Regardless, modular construction has great potential to embody circularity because of its distinct intrinsic characteristics that are not limited to industrial construction, disassembly, and reuse [33]. Even though modular construction facilitates waste reduction, principal CE goals are neither objectively targeted nor explicitly focused. Thus, their full potential is not realised, specifically during the design stage. Hence, it is worth exploring whether synergising circularity and modularity during design can yield optimum benefits in both modular construction and CE. Accordingly, this study aims to investigate current DfMA approaches in modular construction and identify the potential for improvements concerning CE goals through DfC. Thereby, the study proposes the concept of Design for Circular Manufacturing and Assembly (DfCMA) that envisages integrating and synergising circularity and modularity in terms of design to yield optimum benefits in modular construction. Therefore, the research objectives are as follows:

- Proposing and conceptualising Design for Circular Manufacturing and Assembly (DfCMA) as a design framework to deliver circularity and modularity synergistically in circularity-oriented modular construction in the Building Construction Industry (BCI).

- Developing a template for a Design for Circular Manufacturing and Assembly (DfCMA) process to demonstrate potential ways and means of introducing circularity into the Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DfMA) process in circularity-oriented modular construction in the Building Construction Industry (BCI).

For this purpose, a comprehensive literature review was conducted to conceptualise DfCMA in the BCI. This endeavour was followed by interviews with experts in CE and modular construction, brainstorming sessions and the preliminary phase of a case study to identify possible ways and means of introducing or injecting more circularity into a typical DfMA process, as presented below under the following sections and sub-sections.

2. Literature Review

The following section reviews the extant literature in order to provide a better understanding of the study.

2.1. Modular Construction in the Building Construction Industry (BCI)

Off-Site Construction (OSC) is a process of planning, designing, fabricating and assembling building components or elements in a factory to facilitate fast and efficient construction of a building on site [4]. On the other hand, prefabrication can be identified as a manufacturing process that takes place in a factory to form a specific component by combining the required materials before installation of the final product [27]. Precast, prefabrication and modular construction methods are in the spectrum of construction modularity, where the increase in components manufactured and assembled off-site contributes to a higher level of modularity [31]. Here, modularity is an umbrella term that describes the technology of off-site manufacturing, which results in modular components [19]. It is based on the degree of prefabrication, which may range from basic components to complete buildings [31]. Hence, ‘modular construction’ can be identified as a part of OSC and characterised as a “building approach with three-dimensional (3D) units that enclose usable space and form part of the completed building or structure” [34] (p. 64). Modular Integrated Construction (MiC) is also one of the OSC methods, but distinguished as separate, complete and fully-finished three-dimensional-volumetric modules that are manufactured off-site and then transported to the site for direct installation of a complete building [28,31].

Modular construction necessarily focuses on enhancing construction productivity [34] in terms of improved quality, expedited project execution and reduced WLC costs [4,28,31]. Sustainability is invariably a secluded benefit of modular construction [16,28,29]. However, the CE benefits of modular construction have hitherto been overlooked, creating a literature gap and a need within the industry to explore the CE benefits of modular construction in the design stage, since 80% of sustainability impacts are decided during the design stage [35]. Through a theoretical lens of value, it is during the upstream value chain activities that the value is created, and it is during the downstream activities that the value is retained at the highest possible level [36]. This is driven by design that is, in turn, grounded on the elimination of waste and pollution, circulation of products and materials at their highest value, and regeneration of nature [37].

Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DfMA) and Design for Circularity (DfC) as design approaches are juxtaposed in the following sub-section.

2.2. Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DfMA) and Design for Circularity (DfC) in the Building Construction Industry (BCI)

Table 1 analyses DfMA and DfC under different criteria.

Table 1.

Review of DfMA and DfC.

As shown in Table 1, DfMA and DfC have overlapping themes and elements, some of which complement each other, spotlighting the possibility of synergies in addressing their shortcomings. There is vast room for improvement of concepts and practices in both these developing areas, illuminating the path of synergising the two concepts to conceptualise Design for Circular Manufacturing and Assembly (DfCMA). For example, Lean Construction approaches that have reduced waste in construction in general are even more relevant and applicable to modular construction, given their aim to eliminate non-value-adding activities in the manufacturing and assembly processes. Lean construction principles and practices therefore have significant potential in bridging DfMA and DfC as a means of resource optimisation through waste reduction [31,46]. The overall conceptualisation will be discussed in the upcoming sections, followed by the methodology used with potential materials and methods for ways forward.

3. Methodology, Materials and Methods

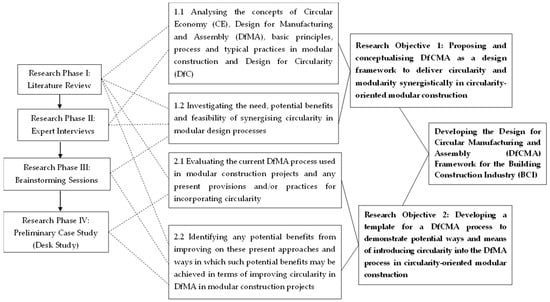

The study adopted a qualitative research methodology, as demonstrated in Figure 1. The qualitative approach is justified given the uniqueness of the BCI and construction value chain compared to other industries [55,56]. As the study advances a theory synthesis to offer novel insights into the DfMA concept by linking it to DfC, a structured and justified research methodology was formulated, which requires a systematic approach based on a cogent argument [57].

Figure 1.

Research Methodology.

In Phase I, an extensive literature review was conducted to analyse the concepts of modular construction, CE, DfMA, and DfC in the BCI. Furthermore, the theoretical process of DfMA in the manufacturing paradigm and the BCI was explored. The analysis helped identify the shared values of DfMA and DfC, paving the path to understanding the synergies whereby the two concepts can complement each other. In addition, the theoretical DfMA process in the BCI was outlined, along with the possibility of synergising CE principles in the DfMA process. In Phase II, eight semi-structured interviews with CE experts in the BCI were carried out to further demarcate the concept of DfC in the BCI from a construction value chain perspective, and the potential benefits and feasibility of synergising circularity in design processes and insights on circularity of modular construction. The rationale for the expert interviews in Phase II was to elucidate the practical insights and understandings of the interviewees based on their attitudes, opinions and experiences [46] to be beneficially grounding the DfC as a systematic approach of a circular design process to create and sustain value throughout the construction value chain. Table 2 presents the profile of CE experts in Phase II.

Table 2.

Profile of expert interviewees in Phase II.

In Phase III, brainstorming sessions were carried out with five CE researchers in the BCI research domain in order to investigate the need, potential benefits and feasibility of synergising circularity in modular design processes and also to identify any provisions and practices for incorporating circularity in the theoretical DfMA process outlined in Phase I of the study. The rationale for brainstorming with CE researchers is that they are well endowed with the conceptualisation of theoretical concepts in order to ground new theories. Table 3 presents the profile of CE researchers in Phase III.

Table 3.

Profile of participants in Phase III.

For the brainstorming sessions, a creative design thinking technique called SCAMPER was used to generate new ideas systematically [58]. SCAMPER is an acronym that stands for the following, as demonstrated in Table 4.

Table 4.

SCAMPER technique guide adapted from [59].

The participants were first enlightened or updated on current theories of DfC and DfMA in order to brainstorm the synergies between the two concepts and the possibility and benefits of incorporating circularity in the DfMA process in principle. Sample framing of the expert interviewees of Phase II and the participants of Phase III was through purposive sampling based on their academic or industry experience in CE and modular construction fields. Given the epistemological and methodological nature of the study, data saturation was assumed when no new data were collected, indicated by data redundancy or replication [46,60].

During Phase IV, a preliminary case study was conducted to further delve into developing the DfCMA process and explore any existing practices in modular construction that can complement and support DfCMA. A single case study offers a “force of example”, which in the context of the BCI, even though it cannot prompt generalisation, may decipher intrinsic knowledge in actual practical circumstances [61]. The specific steel modular building was selected for the study as it was a ‘critical case’ [62] that allowed the authors to appraise the DfCMA constructs and features in the case qualitatively.

Hence, as the preliminary stage of a continuous study, a desk study was conducted to analyse the case based on documents from the project and readily available data online. The collected data were analysed manually using content analysis as manual coding improves the focus on the data set, compared to reliance on an automated process, which might lose the focus on the contextual meaning of the dataset [63]. The results of the data collection and analysis using the above materials and methods are presented as follows.

4. Results

The results of the study are here presented under the following sub-sections.

4.1. Shared Values and Overlapping Themes of Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DfMA) and Design for Circularity (DfC)

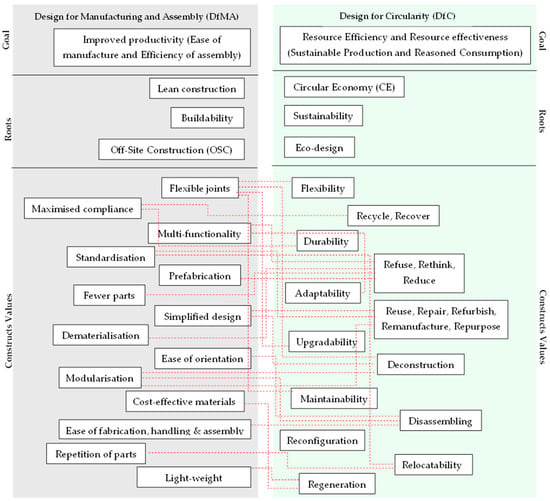

It was observed that DfMA and DfC have numerous overlapping constructs and commonalities. These enabled the groundwork to be laid for establishing clear synergies between the two concepts. Figure 2 demonstrates the shared values of DfMA and DfC. For example, modularity is a key construct of DfMA in terms of productivity, as OSC reduces on-site work, enhances quality control, and provides safer working conditions. In terms of DfC, modularity also entails CE benefits, as production in a controlled environment improves materials management efficiencies. Further, modularisation enables scalability and customisation that makes them flexible and adaptable through simplified disassembly at the perceived End-of-Life (EoL) of the building. Prefabrication of modules also promotes closed-loop resource chains as they enhance transportation and storage, assuming the role of a ‘material inventory’. According to the participants, modularisation can be identified as an opportunity for co-creation from a value perspective, as stakeholders are encouraged to engage actively in the long term to create value. Regarding resources, participants opined that modularisation not only enhances material efficiency but also reduces waste generation. It was also suggested that modules can be optimised for better energy performance and reduced Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions.

Figure 2.

Shared values of DfMA and DfC.

When a building is viewed as an assembly of dismantlable (i.e., disassemblable) components rather than a monolithic structure, it contributes to Design for Disassembly (DfD). Modules with flexible joints are one of the key principles of DfMA that effectively enable DfD. DfD enhances the circularity of a building by promoting dynamism, as buildings can be systematically dismantled at their perceived EoL to be relocated or refurbished. In this case, steel modular buildings were preferred over concrete modules with rigid and complex connections, whereas steel bolted or mechanical connections are more flexible and dismantlable. Steel as a construction material also promotes circularity as steel is durable and yet reliable over time. Steel is also highly reusable and recyclable, with a reduced carbon footprint. Hence, steel modular buildings with flexible connections were considered as ideal examples of DfCMA.

Dematerialisation is a critical CE practice that promotes resource efficiency and reduces raw material extraction. At the same time, fewer parts, design simplification and reduced inventory are key constructs of DfMA, although for different reasons. Reduction of time and cost is the primary focus of DfMA since the fewer the parts and simpler the design, the higher the time-efficiency and cost-efficiency. However, these constructs highly promote DfC as fewer resources are produced and consumed, and less will be extracted and disposed of. Hence, these constructs also minimise waste generation and would be a key solution to the construction waste generation plaguing the BCI. Under ideal conditions, waste generation would reach zero by employing DfMA in modular construction. Participants also noted that DfMA associated with lean construction would reduce non-value-adding activities and components of the construction value chain, facilitating DfC.

Standardisation is another key construct of DfMA that has noteworthy inter-linkages with DfC. In DfMA, standardisation is desirable as it promotes modularity, reusable parts, mass production, easier assembly, enhanced quality, and the possibility of automating the process. When standardised, parts of the product would be interchangeable, simplifying the assembly process and minimising custom parts, which would result in reducing design costs and complexity in manufacturing and assembly. Design errors would also be significantly lowered, thus improving consistency and reliability. Standardisation not only promotes mass production but also mass customisation, where the buildings are mass-produced, with the flexibility of customised design features such as interior designing without significantly increasing the cost. Concerning DfC, standardisation offers ease of reusability and disassembly without significant adjustments. Specifically, standardised connections promote direct disassembly and reassembly. In addition, standardisation promotes optimised and streamlined manufacturing and resource consistency, enhancing resource efficiency and promoting closed loops.

Another salient synergy between DfMA and DfC is that DfA and DfM effectively promote R-strategies such as Refuse, Rethink, Reduce, Reuse, Repair, Refurbish, Remanufacture, Repurpose, Recycle, Recover, or Design for Excellence (DfX) approaches such as Design for Recycling (DfR), Design for Remanufacturing and Reuse (DfRe), Design for Deconstruction (DfD), and Design for Adaptability (DfA). However, it is critical to understand that DfA and DfM do not necessarily target circularity. They primarily focus on productivity yet offer several circular benefits as by-products. Furthermore, the participants assumed a scenario of a fully dismantlable (i.e., disassemblable) and mobile (i.e., relocatable) modular building to demonstrate its capability to adapt directly. Such a building not only promotes adaptability, but also durability and resilience promoted by flexibility. In addition, such a building would also promote the CE principle, ‘Sharing Economy’, for example, mobile or temporary buildings. However, such a concept should be reinforced with necessary ownership and business models such as product-as-a-service.

These shared values and overlapping themes of DfMA and DfC promise their synergy, establishing not only efficient and effective but also sustainable modular construction practices.

4.2. Need, Potential Benefits and Feasibility of Design for Circular Manufacturing and Assembly (DfCMA)

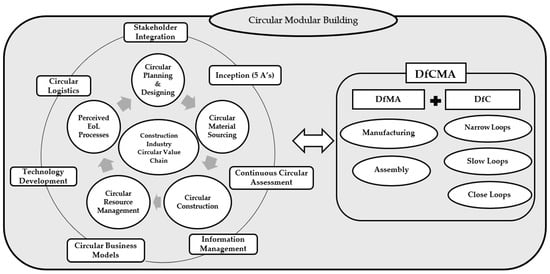

Based on the above synergies, a conceptual framework was developed to structure and operationalise the Design for Circular Manufacturing and Assembly (DfCMA) concept to deliver a circularity-oriented modular building, i.e., ‘circular modular building’. Figure 3 illustrates the conceptual framework of DfCMA.

Figure 3.

Conceptual framework of DfCMA.

This framework was also underpinned by the literature review in Phase I and was developed based on the expert interviews of Phase II. The vision was to synergise DfM and DfA elements of the DfMA concept by designing material and energy loops to narrow, slow, and close resource loops to achieve circularity in the BCI. It was expected to be incorporated into the construction industry value chain based on [13] to create and sustain circular value. The deliverable of the conceptual framework is a ‘circular modular building’, which is idealised as an optimised modular building that is designed, planned, built, operated, maintained, and deconstructed in a manner consistent with CE principles. Such is expected to create value through a rationalised design process, improved material selection, and optimised planning and logistics with a deliberate focus on circularity where value is retained in the Whole Life Cycle (WLC) of the modular project emulating closed loops.

The interviewees and participants in both Phase II and III emphasised vindication for such synergy. Even though the benefits of individual concepts and benefits derived through the synergies between DfMA and DfC are evident not only in the extant literature but also in modular projects, their application is very limited in the BCI. Let alone the individual concepts, their integration and synergy to exploit the best environmental, economic and social potential is seldom explored. This gap is reinforced by the need for a conscious redesign of frameworks by aligning their different objectives in a consolidated agenda rather than seeking scattered benefits as by-products of individual concepts. In other words, even though ad-hoc CE practices are observed in modular construction practices, a systematic and explicitly unified approach such as DfCMA is absent in the BCI.

One foremost opportunity promoting synergy between DfC and DfMA is Design for Deconstruction (or Disassembly) (DfD). DfMA makes DfD viable where modular buildings will be disassembled, relocated, reused or refurbished instead of demolition and landfilling. DfMA also ensures flexibility and adaptability to dynamically operate, maintain, and disassemble during the value retention phase of the modular building. Another potential of DfCMA is in promoting sustainability. Even though the sustainable benefits of circular modular buildings have yet to be quantified through research, participants in Phase III highlighted that DfCMA can enhance environmental, economic, and social sustainability. Both literature and empirical data conveyed the importance of intricate eco-systems in implementing DfC and DfMA in the construction value chain. Hence, composite development of a DfCMA eco-system would be practical since both the individual concepts of DfMA and DfC are presently ‘trending’ in the BCI.

Based on the elucidated knowledge from the data collected in phases II and III, the conceptual DfCMA framework was expounded, as demonstrated in Table 5.

Table 5.

Supplement to the conceptual DfCMA framework.

The proposed DfCMA is characterised by Design for Manufacturing (DfM), Design for Assembly (DfA), Design for Narrowing Resource Loops (DfNL), Design for Slowing Resource Loops (DfSL) and Design for Closing Resource Loops (DfCL) [25,64] and correlated with the Construction Industry Circular Value Chain where DfM, DfA and DfNL primarily focus on Circular Planning and Designing, Circular Material Sourcing and Circular Construction analogous to the ‘Value Creation’ phase, and DfSL and DfCL focus on Circular Resource Management and Perceived EoL Processes, or in other terms the ‘Value Retention’ phase. A non-exhaustive list of strategies for DfM, DfA, DfNL, DfSL and DfCL are presented as examples. In addition, a participant in Phase III proposed the European framework for sustainable buildings: ‘Level(s)’, which was developed to assess the sustainability performance of buildings to assess the impact of DfCMA with necessary adaptations quantitatively. Notably, ‘Indicator 2: Resource efficient and circular material life cycles’ promotes design optimisation to facilitate circular flows, as listed below [65].

- Bill of quantities, materials and lifespans

- Construction and demolition waste

- Design for adaptability and renovation

- Design for deconstruction

4.3. Proposed Design for Circular Manufacturing and Assembly (DfCMA) Process for Modular Construction in the Building Construction Industry (BCI)

Having qualitatively analysed the DfCMA concept in Phases I-III, the next step was investigating how to introduce circularity into the DfMA process. Table 6 lists the parameters of the case study to provide the background information for the analysis.

Table 6.

Case Profile.

The case was then qualitatively investigated in terms of the availability and application of DfCMA constructs, as presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

DfCMA analysis of the case study.

It can be observed that several DfCMA features are present in the case study. Its better performance as a modular building indicates how the synergised application of DfMA and DfC can potentially provide successful results [68]. However, it must be noted that the case has neither systematically applied DfCMA as a concept nor in its processes. Indeed, realising that this innovative novel concept, as proposed in this paper, is yet to be applied, the authors recognised and analysed the scattered elements and constructs of DfCMA that were identified. Nevertheless, the case provides pronounced pointers on how systematic implementation of DfCMA can benefit the modular construction industry in terms of productivity and circularity.

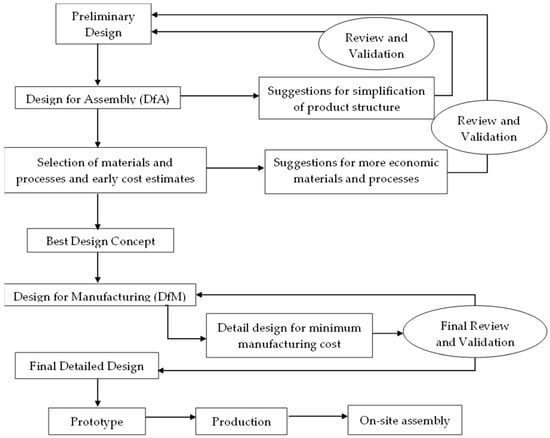

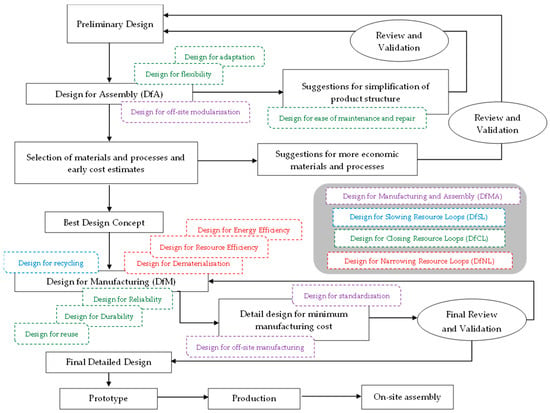

Having investigated the DfCMA features of this case, the next step was to propose a conceptual DfCMA process. For this purpose, a typical DfMA process for modular construction in BCI was theoretically developed, drawing insights from the manufacturing paradigm [24] and prefabrication of non-structural components [23], as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Typical DfMA process in Modular Construction, adapted from [23,24].

Based on the preliminary evaluation of the case, Figure 5 depicts the conceptual DfCMA process, as extracted and ‘constructed’ (i.e., mapped) from this case study.

Figure 5.

Proposed conceptual DfCMA process in Modular Construction.

The results analysed from the four data collection phases are discussed below.

5. Discussion

While the novel term of Design for Circular Manufacturing and Assembly (DfCMA) itself is coined and proposed in this study, as far as targeting more sustainable modular construction in the BCI, neither the idea of ‘circular modular buildings’ nor CE transition in modular construction is novel in the extant literature. Among them, ref. [33] proposes strategies to overcome CE transition in modular construction, while ref. [69] proposes strategies to overcome sustainability gaps in modular construction. The authors of [32] explored ‘circular modular construction projects’ in Hong Kong and proposed critical success factors for implementing and managing them. The paper [32] highlights that the most critical aspects of circular modular buildings are design decisions, which require consideration of longer economic life, deconstruction, and waste management. The study further identifies the need for stakeholder collaboration during the design stage with a Whole Life Cycle (WLC) perspective of the building. Further, an explicit approach of integrating CE principles in modular construction for standardisation, modularisation, longevity, resource efficiency, disassembly, deconstruction, adaptability, flexibility, remanufacturing, recoverability, and energy efficiency is put forward that supports the underlying rationale for this study of advocating a systematic and conscious synergy of DfC and DfMA in modular construction in the BCI [32].

The authors of [70] made use of a ‘transportable modular housing unit’ to demonstrate the environmental impact in terms of energy efficiency. The authors mention the transportability of the modular unit using a truck or a cargo ship without posing a negative impact on the environment at its perceived End-of-Life (EoL). Another study [71] harnesses a similar notion of ‘relocatable modular buildings’ to investigate their ability to deliver circularity and usability in the built environment. The authors state that relocating an entire building provides the highest level of adaptability and that relocatable modular buildings deliver circularity given the low risk associated with its ownership model (leasing), rapidity, multi-functionality, thermal and energy efficiency, and the possibility of adaptation and customisation. One of the critical opportunities of DfCMA is through Design for Deconstruction (or Disassembly) (DfD), which facilitates disassembling or deconstructing modular buildings that will be transported and relocated, thus supporting closed loops. DfD in circular modular buildings also contributes to the flexibility and adaptability of modules and components, ensuring their dynamism in the construction value chain.

Likewise, [72] describes the circular potential of ‘temporary modular buildings’ through DfD and reassembly, while [54] also emphasises that modules designed for disassembly enable reuse practices at the perceived EoL. These studies employ a similar research approach to investigating the environmental benefits of applying the CE principles of reuse and DfD in modular construction. While the authors of [54] conducted their research in Australia (developed economy), the study reported in [72] was carried out in Sri Lanka (developing economy). In both these studies, incorporating CE principles (reuse and DfD over recycling) in the modular building design process is posited. Advancing on these previous approaches, DfCMA takes a step forward by recommending focused and systematic integration of CE principles in the modular building design process based on DfMA as a methodological approach for evaluating and improving the design while synergising DfC.

6. Conclusions

This study coined the term and proposed the concept of Design for Circular Manufacturing and Assembly (DfCMA) that envisages synergising circularity (Design for Circularity (DfC)) and modularity (Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DfMA)) during the design stage. Such synergy is proposed as a part of ongoing research based on an extensive evaluation of the individual concepts given their shared values and commonalities, such as modularisation, dematerialisation, and standardisation. Following a thorough literature review, supported by expert interviews and brainstorming sessions, a conceptual DfCMA framework was developed. A conceptual DfCMA process was also proposed by conducting a case study analysis. The case study demonstrates how the synergy of DfC and DfMA in a modular construction project can deliver circularity and modularity. The study further stresses the importance of systematic implementation of DfCMA explicitly and consciously over ad-hoc practices.

The study contributes to theory by proposing an innovative concept of synergising circularity and modularity as encapsulated in DfCMA. The study also urges practitioners (such as clients and professionals) to methodically and deliberately adopt CE principles in modular buildings in the design stage. It also highlights that modular construction provides a suitable trajectory towards implementing circular practices in the BCI, and also that design as the initiation of the value creation is the ideal, and indeed necessary, starting point of CE implementation to ensure maximised value retention throughout the Whole Life Cycle (WLC) of a building. The findings also highlight the immediate need for a suitable eco-system to implement DfCMA, including guidelines, standards, innovative technologies, stakeholder collaboration, and business models. The study further prompts policymakers to factor the highlighted circularity and sustainability aspects in their Off-Site Construction (OSC) propositions into their strategy formulation and decision-making.

The primary goal of this study is conceptual theorisation and proposal of DfCMA, hence the basic qualitative research methodology. Thus, the intrinsic methodological limitations, such as the judgements and personal bias of authors, interviewees and participants, and the lack of generalisability of the case study findings, are inevitable. Hence, it is recommended to step forward from the conceptualisation stage to quantitatively evaluate and validate the DfCMA framework and process through empirical research. Accordingly, quantitatively measuring the impact of employing DfCMA and developing DfCMA-specific performance indicators is recommended. It is also necessary to delve into the different building layers (such as the ‘Building level’, ‘Systems, assemblies and sub-assemblies’ level’, ‘Product and component level’, and ‘Material level’) by breaking down the building into different layers as it promotes better management of modular buildings across the WLC. Further research on barriers, enablers and drivers of DfCMA is also recommended, along with modelling the complex and dynamic inter-linkages between the different constructs and strategies in the DfCMA framework.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.G.D., S.T.N., M.M.K. and J.C.; Formal analysis, K.G.D., S.T.N., M.M.K. and J.C.; Methodology, K.G.D., S.T.N., M.M.K. and J.C.; Project administration, S.T.N., M.M.K. and J.C.; Supervision, S.T.N., M.M.K. and J.C.; Writing—Original draft, K.G.D.; Writing—Review & editing, K.G.D., S.T.N., M.M.K. and J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to acknowledge the Environment and Ecology Bureau of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government for financially supporting this study through the Green Tech Fund (Grant No.: GTF202110158). The paper also constitutes an output of part of a PhD research study carried out under the Hong Kong PhD Fellowship Scheme (No.: PF19-39440) of the HKSAR Government Research Grants Council.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of The University of Hong Kong (EA210475 on 23 November 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions and will be available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the expert interviewees and participants of the brainstorming sessions for volunteering their time and effort to make this study possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Arup. The Circular Economy in the Built Environment; Arup: London, UK, 2016; Available online: https://www.arup.com/insights/circular-economy-in-the-built-environment/ (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Boulding, K.E. The economy of the coming spaceship earth. In Environmental Quality in a Growing Economy; Jarrett, H., Ed.; Resources for the Future/Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MA, USA, 1966; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Geisendorf, S.; Pietrulla, F. The circular economy and circular economic concepts—A literature analysis and redefinition. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2017, 60, 771–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obi, L.; Arif, M.; Daniel, E.I.; Oladinrin, O.T.; Goulding, J.S. Establishing underpinning concepts for integrating circular economy and offsite construction: A bibliometric review. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2023, 13, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards a Circular Economy: Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Isle of Wight, UK, 2015; Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/towards-a-circular-economy-business-rationale-for-an-accelerated-transition (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Giorgi, S.; Lavagna, M.; Campioli, A. Circular economy and regeneration of building stock: Policy improvements, stakeholder networking and life cycle tools. In Regeneration of the Built Environment from a Circular Economy Perspective; Della Torre, S., Cattaneo, S., Lenzi, C., Zanelli, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme. 2020 Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction: Towards a Zero-Emission, Efficient and Resilient Buildings and Construction Sector; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. Available online: https://globalabc.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/2020%20Buildings%20GSR_FULL%20REPORT.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Zairul, M. The recent trends on prefabricated buildings with circular economy (CE) approach. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2021, 4, 100239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewagoda, K.G.; Ng, S.T.; Kumaraswamy, M.M.; Chen, J. Understanding and readiness of the building construction industry in designing for circularity: A comparison with manufacturing industries. In Proceedings of the AUBEA2023 Conference, Auckland, New Zealand, 26–28 November 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dokter, G.; Thuvander, L.; Rahe, U. How circular is current design practice? Investigating perspectives across industrial design and architecture in the transition towards a circular economy. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 692–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi-Afari, P.; Ng, S.T.; Chen, J. Developing an integrative method and design guidelines for achieving systemic circularity in the construction industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 354, 131752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, M.; Cordella, M. Does circular economy mitigate the extraction of natural resources? Empirical evidence based on analysis of 28 European economies over the past decade. Ecol. Econ. 2023, 203, 107607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewagoda, K.G.; Ng, S.T.; Chen, J. Driving systematic circular economy implementation in the construction industry: A construction value chain perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 381, 135197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewagoda, K.G.; Ng, S.T.; Kumaraswamy, M.M. Design for Circularity: The Case of the Building Construction Industry. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1101, 062026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charef, R. Is Circular Economy for the Built Environment a Myth or a Real Opportunity? Sustainability 2022, 14, 16690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, W.; Bai, Y.; Ngo, T.D.; Manalo, A.; Mendis, P. New advancements, challenges and opportunities of multi-storey modular buildings—A state-of-the-art review. Eng. Struct. 2019, 183, 883–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology. Modern Methods of Building Construction; Postnote No. 209; Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology: London, UK, 2003; Available online: https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/POST-PN-209/POST-PN-209.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Land and Housing Corporation: NSW Government. Available online: https://www.dpie.nsw.gov.au/land-and-housing-corporation/plans-and-policies/modern-methods-of-construction (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Building and Construction Authority. Prefabricated Pre-Finished Volumetric Construction (PPVC) Guidebook; Building and Construction Authority: Singapore, 2017. Available online: https://www1.bca.gov.sg/docs/default-source/docs-corp-news-and-publications/publications/for-industry/ppvc_guidebook.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Some Opinions of the CPC Central Committee and the State Council on Further Strengthening the Management of urban Planning and Construction; The State Council of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2016; Available online: http://ccprjournal.com.cn/news/9373.htm (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- HKSAR Government. The Chief Executive’s 2023 Policy Address; HKSAR Government: Hong Kong, China, 2023. Available online: https://www.policyaddress.gov.hk/2023/public/pdf/policy/policy-full_en.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Modular Building Institute. Modular Construction Reports & Industry Analysis; Modular Building Institute: Charlottesville, VA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.modular.org/industry-analysis/ (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Wasim, M.; Han, T.M.; Huang, H.; Madiyev, M.; Ngo, T.D. An approach for sustainable, cost-effective and optimised material design for the prefabricated non-structural components of residential buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32, 101474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boothroyd, G. Assembly Automation and Product Design; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Institute of British Architects. DfMA Overlay to the RIBA Plan of Work; Royal Institute of British Architects: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.architecture.com/knowledge-and-resources/resources-landing-page/dfma-overlay-to-the-riba-plan-of-work#available-resources (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Gao, S.; Jin, R.; Lu, W. Design for manufacture and assembly in construction: A review. Build. Res. Inf. 2020, 48, 538–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Shen, G.Q.; Xue, X. Critical review of the research on the management of prefabricated construction. Habitat Int. 2014, 43, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmageed, S.; Zayed, T. A study of literature in modular integrated construction—Critical review and future directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 124044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali, M.; Hewage, K. Life cycle performance of modular buildings: A critical review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 62, 1171–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Zhang, Z. Benchmarking the sustainability of concrete and steel modular construction for buildings in urban development. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 90, 104400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, R.W.M.; Loo, B.P.Y. Sustainability implications of using precast concrete in construction: An in-depth project-level analysis spanning two decades. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 378, 134486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuni, I.Y.; Shen, G.Q. Developing critical success factors for integrating circular economy into modular construction projects in Hong Kong. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 29, 574–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenbach, S.; Zeller, J.C.; Osebold, R. A Roadmap towards Circularity—Modular Construction as a Tool for Circular Economy in the Built Environment. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 588, 052027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Hon, C.K. Briefing: Modular integrated construction for high-rise buildings. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Munic. Eng. 2020, 173, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa, J.A.; Esparragoza, I.; Maury, H. Trends and Perspectives of Sustainable Product Design for Open Architecture Products: Facing the Circular Economy Model. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf.-Green Technol. 2019, 6, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedir, F.; Hall, D.M. Resource efficiency in industrialized housing construction—A systematic review of current performance and future opportunities. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 286, 125443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Circular Economy Glossary; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://emf.thirdlight.com/file/24/BGMwzd_BG.iZsrLBGtqmBgvFbCK/%5BEN%5D%20Circular%20Economy%20Glossary%20%7C%2030-09-21.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Tan, T.; Lu, W.; Tan, G.; Xue, F.; Chen, K.; Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Gao, S. Construction-Oriented Design for Manufacture and Assembly Guidelines. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Yu, J. Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DfMA) Checklists for Off-Site Construction (OSC) Projects. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nußholz, J.L.K.; Rasmussen, F.N.; Whalen, K.; Plepys, A. Material reuse in buildings: Implications of a circular business model for sustainable value creation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, L.C.M.; van Stijn, A.; Rasmussen, F.N.; Birkved, M.; Birgisdottir, H. Development of a life cycle assessment allocation approach for circular economy in the built environment. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, G. Circular economy strategies for adaptive reuse of cultural heritage buildings to reduce environmental impacts. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 152, 104507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-K.; McGovern, S.; Belsky, M.; Middleton, C.; Brilakis, I. A Suitability Analysis of Precast Components for Standardized Bridge Construction in the United Kingdom. Procedia Eng. 2016, 164, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomponi, F.; Moncaster, A. Circular economy for the built environment: A research framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arup; Ellen MacArthur Foundation. From Principles to Practices: First Steps Towards a Circular Built Environment; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: London, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/articles/first-steps-towards-a-circular-built-environment (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Langston, C.; Zhang, W. DfMA: Towards an Integrated Strategy for a More Productive and Sustainable Construction Industry in Australia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankohi, S.; Carlo, C.; Iordanova, I.; Bourgault, M. Design-for-Manufacturing-and-Assembly (DfMA) for the construction industry: A review. In Proceedings of the 2022 Modular and Offsite Construction (MOC) Summit, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 27–29 July 2022; 29 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Eissa, R.; El-adaway, I.H. Accelerating the Circular Economy Transition: A Construction Value Chain-Structured Portfolio of Strategies and Implementation Insights. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2024, 150, 04024077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasim, M.; Vaz Serra, P.; Ngo, T.D. Design for manufacturing and assembly for sustainable, quick and cost-effective prefabricated construction—A review. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2022, 22, 3014–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanters, J. Circular Building Design: An Analysis of Barriers and Drivers for a Circular Building Sector. Buildings 2020, 10, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campioli, A.; Dalla Valle, A.; Ganassali, S.; Giorgi, S. Designing the life cycle of materials: New trends in environmental perspective. Techne 2018, 16, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Tan, T.; Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, K.; Gao, S.; Xue, F. Design for manufacture and assembly (DfMA) in construction: The old and the new. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2021, 17, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, H.; Kim, H.-G.; Kim, J.-S. Integrated Off-Site Construction Design Process including DfMA Considerations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minunno, R.; O’Grady, T.; Morrison, G.M.; Gruner, R.L. Exploring environmental benefits of reuse and recycle practices: A circular economy case study of a modular building. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 160, 104855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chileshe, N.; Rameezdeen, R.; Hosseini, M.R. Drivers for adopting reverse logistics in the construction industry: A qualitative study. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2016, 23, 134–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Toit, J.L.; Mouton, J. A typology of designs for social research in the built environment. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2013, 16, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, E. Designing conceptual articles: Four approaches. AMS Rev. 2020, 10, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozyaprak, M. The Effectiveness of SCAMPER Technique on Creative Thinking Skills. J. Educ. Gift. Young Sci. 2015, 4, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Serrat, O. The SCAMPER Technique. In Knowledge Solutions: Tools, Methods, and Approaches to Drive Organizational Performance; Serrat, O., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 311–314. [Google Scholar]

- Aguboshim, F.C. Adequacy of sample size in a qualitative case study and the dilemma of data saturation: A narrative review. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2021, 10, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research. Qual. Inq. 2006, 12, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskarada, S. Qualitative Case Study Guidelines. Qual. Rep. 2014, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldana, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- van Stijn, A.; Gruis, V. Towards a circular built environment. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2020, 9, 635–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Levels(s): Putting Circularity into Practice; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [CrossRef]

- BROAD Group. Available online: http://en.broad.com/ (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. Garden A-1, Changsha. 2024. Available online: https://www.skyscrapercenter.com/building/garden-a-1/46320 (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Broad USA. BROAD Holon Building. Available online: https://broadusa.com/broad/holonbuilding/ (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Garusinghe, G.D.A.U.; Perera, B.A.K.S.; Weerapperuma, U.S. Integrating Circular Economy Principles in Modular Construction to Enhance Sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satola, D.; Kristiansen, A.B.; Houlihan-Wiberg, A.; Gustavsen, A.; Ma, T.; Wang, R.Z. Comparative life cycle assessment of various energy efficiency designs of a container-based housing unit in China: A case study. Build. Environ. 2020, 186, 107358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrö, R.; Jylhä, T.; Peltokorpi, A. Embodying circularity through usable relocatable modular buildings. Facilities 2019, 37, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawardana, J.; Sandanayake, M.; Kulatunga, A.K.; Jayasinghe, J.A.S.C.; Zhang, G.; Osadith, S.A.U. Evaluating the Circular Economy Potential of Modular Construction in Developing Economies—A Life Cycle Assessment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).