Abstract

Food waste has become an increasingly common and serious global problem, affecting the guarantee of food security in China and the sustainable development of the national agricultural and food system. Urban households are the main source of food waste on the consumer side. Given China’s unique culture, economy, and social environment, the drivers of food waste in urban households need to consider broader social, psychological, and situational factors in order to provide a basis for formulating and implementing targeted policy measures. This article conducts a grounded theoretical analysis of semi-structured interview data from 56 urban households in China and constructs a driving factor model for food waste in urban households in the Chinese context. Research has found that the influencing factor system of food waste in Chinese urban households includes seven interrelated main categories. Among them, risk perception has a direct effect on responsibility awareness and behavioral tendencies, responsibility awareness and environmental pressure have a direct effect on behavioral tendencies, behavioral tendencies have a direct effect on behavioral choices, perception barriers play a moderating role in the impact of risk perception on responsibility awareness and behavioral tendencies, and behavioral constraints play a moderating role in the impact of behavioral tendencies on behavioral choices. This study enriches the research on the mechanism of food waste behavior in Chinese households, providing scientific basis for the formulation of intervention strategies for food waste in Chinese households, and also providing reference for revealing the mechanism of food waste behavior in other countries with similar cultural backgrounds.

1. Introduction

As the economy rapidly develops and urbanization progresses swiftly, global food waste has seen a significant increase over the past few decades. Food waste has become an increasingly prevalent and severe global issue [1]. Annually, approximately 1.6 to 2.5 billion tons of food are lost or wasted globally, accounting for 32% to 40% of human food consumption [2]. Compared to the annual loss and waste of 1.3 billion tons reported by the Food and Agriculture Organization more than a decade ago [3], there has been no significant reduction in global food loss and waste. The situation remains dire in terms of reducing food loss and waste. Food waste not only squanders agricultural and food resources but also leads to substantial economic losses, triggers serious environmental crises, exacerbates social inequalities, and severely hampers the sustainable development of the food and agricultural system [4]. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) call for a reduction in food losses in production and supply chains, including post-harvest losses, and aim to halve per capita global food waste at the retail and consumer levels. Moreover, the 2021 United Nations Food Systems Summit called for actions to reduce food waste to safeguard joint societal and environmental interests.

China, as a key implementing country of the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the world’s largest emerging economy with the second-largest population, plays a pivotal role in managing food waste to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). With rising income levels and the pursuit of a higher quality of life, an increasing number of Chinese residents have moved beyond frugal food consumption habits. There is a growing demand for diversity, nutrition, taste, freshness, and health in food [5], leading to ‘hedonic, competitive, and luxurious’ consumption attitudes among some citizens [6]. Between 2014 and 2018, China’s annual total food production averaged 1.293 billion tons, with actual utilization and consumption amounting to 1.068 billion tons, resulting in a high food loss and waste of approximately 349 million to 400 million tons [7]. The issue of food waste is increasingly affecting the security of China’s food supply and the sustainable development of the national agricultural and food system, garnering growing attention.

Food waste is concentrated in the consumption stage of the food supply chain, with households being the primary source of food waste at the consumption end [8]. According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) report, 61% of global food waste occurs in household consumption, with 13–59% being avoidable [9]. Compared to developed countries, household food waste in developing countries has not received sufficient attention, but this does not mean that developing countries do not have serious food waste issues [10]. As the world’s largest emerging economy, China has experienced significant household waste phenomena due to its booming economy and rapid urbanization over the past decade. Research by Li et al. found that over 90% of Chinese households exhibit food waste, with an average waste of 9.9% of the total meal preparation [11]. Estimates by Song et al. put the annual per capita household food waste in Chinese provinces at 12–33 kg [12], which is lower than many developed countries. However, multiplied by China’s large population base, the total volume of household food waste in China is staggering.

Current research on household food waste in China focuses on the assessment of food waste volumes, correlations with demographic characteristics, environmental impacts, and policy recommendations [13,14]. For example, Zhu et al. assessed the level of food waste in 1479 rural Chinese households, analyzing the characteristics and regional differences of rural household food waste in China and discussing its impact on resources and the environment [15]. Hou et al. measured the extent of food waste among different gender groups and explored the key factors influencing food waste levels among these groups [16]. Liu et al. assessed different strategies for preventing and reducing food waste based on differences in gender, education level, family annual income, dining out, and ordering food ingredients among urban and rural families in China [17]. Obuobi et al. explored the factors that predict household food waste behavior from a moral perspective [18]. Cheng et al. explored the spatial and temporal differences in the environmental impact of food waste between urban and rural areas based on macro food consumption data in China [19]. Although these studies address the drivers of wasteful behavior, most considerations remain at the demographic level. Given the weak explanatory power of demographic factors on household food waste, there is a need for more explanatory socio-psychological behavioral models.

In terms of the mechanisms and drivers of food waste formation, extensive research has been conducted internationally, yielding significant results [20]. On one hand, the characteristics of the food itself, such as spoilage, expiration, and quality defects, contribute to household food waste [21]. On the other hand, numerous studies show that consumer attributes and behaviors significantly impact household food waste [22]. Overall, the main drivers of household food waste include lifestyle of family members [23], their social, economic, and environmental awareness [24], purchasing, processing, and storage habits [25], and demographic variables such as family size, income, and age [26]. Additionally, perceived behavioral control and personal norms are significant drivers of the willingness to waste food [27]. Meanwhile, scholarly research on the mechanisms of food waste formation in Chinese households is increasing. For example, Luo et al. analyzed food waste in rural Chinese households, showing that food waste is related to economic development and significantly affected by food preparation habits and family characteristics [28]. Zhang et al. found, in their study of urban households in Wuhan, that consumers’ perceptions significantly influence the amount of food waste per meal per person [29]. Jiang et al. found that household food waste decreases over time, influenced by factors such as income, family size, and regional dietary habits [30]. These studies often focus on specific behaviors or a few particular factors, without addressing the broader socio-psychological and situational factors affecting household food waste. Currently, there are few comprehensive qualitative studies on the mechanisms and drivers of food waste in Chinese households. China’s unique cultural, economic, and social environments mean that the motives, behaviors, and consequences of household food waste may differ significantly from those in other cultural contexts. These issues limit our deep understanding of the phenomenon of household food waste in China and also affect the effectiveness of targeted policy measures.

At present, China still exhibits a prevalent dual economic structure between urban and rural areas, leading to a typical division of households into urban and rural categories. As urbanization progresses, the current urban population has reached 902 million, accounting for 63.89% [31]. Due to the long-standing urban–rural dichotomy, there is a noticeable difference in the perception of food waste between urban and rural households in China [32]. Factors such as income disparities, lifestyle habits, food costs, and distribution channels result in generally higher levels of food waste in urban households compared to rural ones. Compared to rural families, urban households are more accessible for interviews, making data collection easier. As the influence of grounded theory continues to grow within the international community of social science research, its application in social psychology has become increasingly widespread, particularly in the field of consumer behavior [33]. Although there are existing analyses based on well-established theories such as the norm activation theory and the theory of planned behavior addressing the factors influencing urban household food waste behavior [34,35], a comprehensive and systematic coverage of all significant factors and their interrelationships remains theoretically unsupported. In contrast to established theoretical frameworks, grounded theory follows a bottom-up approach, avoiding predetermined factor compositions and relationships. The fundamental principle of this theory is to conduct a thorough analysis of raw data to distill core concepts and theoretical frameworks. It emphasizes maintaining the integrity and comprehensiveness of the data throughout the research process, avoiding subjective assumptions and preconceived notions, as well as the openness and comprehensiveness of the original data, systematically considering the interaction of factors such as family consumption habits, psychological factors, and social environments. Therefore, researchers are required to employ ‘theoretical sampling’ standards, purposefully selecting study subjects, organizing, and analyzing the gathered raw data, ultimately to generate and validate a theory [36]. This allows for an in-depth exploration of the underlying causes behind the phenomenon of family food waste, providing a theoretical basis for the formulation of effective waste reduction strategies. Additionally, the flexibility of grounded theory enables researchers to make timely adjustments based on new phenomena and issues that arise during the research process, ensuring the timeliness and adaptability of the study results. Given these factors, this study advocates the use of qualitative research methodologies, such as grounded theory, to deeply explore the underlying logic and socio-cultural roots of food waste behaviors in Chinese urban households. This approach aims to provide policymakers with more precise data support and theoretical bases, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of responses to this challenge.

This study conducted in-depth interviews with members of 56 households to understand the driving factors behind food waste in urban Chinese families and to develop a driving factor model for food waste in urban households in the Chinese context. This model aims to assist policymakers, scholars, and practitioners in designing and sharing effective prevention practices. The contributions of this paper are as follows: (1) This paper conducted in-depth interviews with urban residents in China and collected first-hand data on the formation process of household food waste behavior. Based on these data, the key driving factors of food waste in Chinese urban households were summarized using grounded theory and a conceptual model of key driving factors of household food waste suitable for the Chinese context was constructed. (2) Based on the mature theoretical framework and existing research findings, a detailed explanation of the conceptual model of key driving factors was provided, and new findings on the influencing factors of food waste in urban households in the Chinese context were proposed. (3) Based on the research results and conclusions, strategic suggestions are proposed to reduce food waste in urban households in China, providing a reference basis for further policy interventions targeting food waste in urban households in China.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material Description

This study initially designed a survey questionnaire, which included 10 questions reflecting personal/family basic information, four questions on daily dining habits, 15 questions on food waste behavior, and 7 questions to guide divergent thinking. To better achieve the research objectives, the study adopted a combination of online and offline methods for conducting in-depth personal interviews. Given the significant urban–rural disparities in China, households in different regions and income groups may exhibit substantial differences in food waste behavior. To ensure the representativeness of the sample, this study covers seven regions in China, as well as different individual and family structural characteristics. Finally, a total of 56 individuals participated in the interviews, with 40 being conducted online, each lasting about 55 min, and 16 being conducted offline, each lasting about 45 min. This process resulted in 56 audio files of the interviews, which, with the respondents’ consent, were recorded, archived, and organized into interview transcripts, totaling nearly 250,000 words. For this paper, 42 of these interview transcripts were randomly selected for coding analysis and model construction, while the remaining 14 were reserved for testing theoretical saturation. The geographical distribution of the respondents is shown as below: 5 samples in Northwest region, 11 samples in North China regions, 6 samples in Northeast region, 9 samples in Central China region, 13 samples in East China region, 4 samples in Southwest region, and 8 samples in South China region. The statistical data of the respondents are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic information about the interviewees (N = 56).

2.2. Research Methods

Grounded theory was employed in this paper to examine the driving factors of food waste in Chinese urban households, which was developed by scholars Glaser and Strauss in 1967, designed for generating new theories from empirical data [37]. The specific steps are as follows:

Step 1: Open coding. Open coding is a method of detailed analysis of interview records or other raw data, involving the classification and tagging of each word, sentence, and paragraph of the text to identify significant phenomena or events from the data. This process aids in the formation of preliminary concepts and in determining the categories to which these concepts belong.

In this paper, after conducting interviews with each interviewee, the researcher immediately replays the interview recordings repeatedly, transcribes them into text in a timely manner, carefully reads, deeply understands, and analyzes the interview text, and writes an analysis memorandum. On the basis of textual materials, researchers carefully analyze the sentences and paragraphs in the original interview materials, extract semantic blocks from the text based on their own insights, define phenomena through “labeling”, select content related to the research topic in the textual materials, and label them. As suggested by Zhang et al. [38] and Rankohi et al. [39], tags that appeared three or more times can be retained. Furthermore, we conceptualize and aggregate similar phenomena found in the labels based on the memo and the researcher’s cognition to generate concepts. Finally, multiple concepts with the same or similar phenomena are aggregated into a concept group, and the concept group is named with a more abstract name and unified into the corresponding category.

To ensure the accuracy of the coding results, this study adopts an open principle to accept any possible concepts in the absorbed data. Using NVivo 11.0 qualitative analysis software, the original words of the interviewees are used as the basic material for extracting initial concepts, and the original interview text is encoded line by line.

Step 2: Axial coding. The primary task of axial coding is to discover and establish various connections between independent categories, explore the underlying logical relationships between categories, and develop core and sub-categories [40].

In this paper, for the categories formed in open coding, in-depth analysis of the relationships between categories is conducted through axial coding, further establishing the connections between categories and integrating them into higher-level main categories. Axis coding can organize experiential materials in a new, clearer, and more integrated way. In this study, the initial categories obtained during the open coding stage were induced based on concept groups. Some categories have significant similarities or belong to the same larger concept category, and further higher-level induction is needed for these categories. In order to deeply explore the interrelationships between various factors and maximize the explanatory power of the focused categories, this section further clarifies the hierarchical relationships between the initial categories so that categories can more accurately and comprehensively explain the phenomenon. After further induction and summarization, a structural framework system for factors affecting Chinese urban residents’ food waste is finally obtained.

Step 3: Selective coding. According to Amaral and Figueiredo [41], selective coding is a process of further integrating and refining preliminary analysis results. In this process, researchers extract ‘core categories’ with generalizability from the main categories and attempt to systematically connect these core categories with other related categories by constructing typical models. Additionally, researchers need to analyze and verify the interrelationships among these categories and develop a ‘Story Line’ to describe the narrative and behavioral phenomena of the entire study, ultimately forming a theoretical framework.

In this paper, researchers conducted interviews closely around the theme of influencing factors on food waste in Chinese urban households, carefully screening and filtering out irrelevant information before analyzing the collected interview data. During the data analysis process, the focus is always on the central theme, and through open coding and axial coding, the main categories of food waste in Chinese urban households can be ultimately formed.

Step 4: Validity testing. In the data analysis stage, due to differences in personal cognition and knowledge reserves, different researchers may have different grasp of interview details and interview materials, resulting in different coding results. Therefore, most qualitative researchers believe that coding consistency needs to be tested. Miles and Huberman proposed a method to compare whether the coding of different encoders is consistent, known as recorder consistency, which involves having several people simultaneously encode a manuscript and then comparing the encoding results to determine whether the same encoding and theme have been achieved. Generally speaking, frequency can be used to calculate the proportion of similar codes, while reliability statistics (kappa) are used to compare systematic data. In NVivo 11.0, the “encoding comparison” function is provided to achieve consistency check of the recorder. In this study, six researchers familiar with NVivo 11.0 software and the characteristics of food waste in urban households were divided into two groups to independently encode 42 texts. Then, the consistency of the coding results between the two groups was measured through the “Encoding Consistency Percentage” function in Nvivo 11.0 software to ensure the reliability of the study.

Besides, following the practices of Züleyha and QURESHİ [42], the theoretical saturation test is necessary, aiming to test the completeness and comprehensiveness of the research theory construction, thereby helping to ensure that the research results have high credibility and effectiveness. When newly collected data cannot provide new insights or improve existing theories, it can be considered that the theory has reached saturation.

For our researchers, the analysis of qualitative research data is very tedious and laborious, requiring a lot of time. In order to improve efficiency, this study used the qualitative analysis software NVivo 11.0 to assist in the coding and analysis of the data. However, the entire data analysis and induction process mainly relies on the researcher’s own cognitive and analytical abilities. Through continuous communication with urban residents and repeated comparison of interview data, the researcher’s research conclusions are revised.

3. Results

3.1. Open Coding Results

According to the open coding (Step 1 in Section 2.2), after organizing data collected from 42 respondents, tags such as ‘resource wastage’, ‘decline in social ethos’, and ‘environmental improvement’ were identified, and 65 initial concepts and 17 initial categories are obtained. To save space, Table 2 presents all initial categories, some original data sentences, and the corresponding initial concepts.

Table 2.

Concepts and initial categories formed by open coding.

3.2. Axial Coding Results

According to the axial coding (Step 2 in Section 2.2), it was found that the different categories derived from open coding indeed have intrinsic connections at the conceptual level. Based on the interrelationships and logical sequence of 17 categories, this study identified seven main categories: perception awareness, perceptual barriers, responsibility awareness, environmental pressure, behavioral constraints, behavioral tendencies, and behavioral choices. The specific contents of these categories are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Main categories formed by axial coding.

3.3. Selective Coding Results

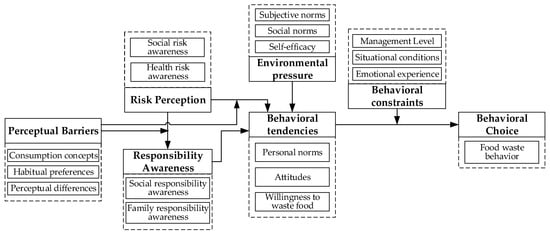

According to the selective coding (Step 3 in Section 2.2), by analyzing the context conditions, the seven main categories of food waste in Chinese urban households obtained through axial coding (named risk perception, perceptual barriers, responsibility awareness, environmental pressure, behavioral constraints, behavioral tendencies, and behavioral choice) can form a core category named “Influencing Factors and Mechanisms of Food Waste Behavior”. The typical relational structure of the main categories is shown in Table 4, and a new conceptual model of the influencing factors on urban family food waste behavior was constructed accordingly, as shown in Figure 1.

Table 4.

Typical relational structure of the main category.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of influencing factors on food waste behavior in urban households in China.

3.4. Validity Testing Results

- (1)

- Coding consistency test results

According to the validity testing (Step 4 in Section 2.2), the results showed that the initial coding consistency percentage of all nodes between the two groups was between 84.55% and 97.43%.

- (2)

- Theoretical saturation test results

According to the validity testing (Step 4 in Section 2.2), for the theoretical saturation test, this study utilized an additional 14 interview transcripts to test for theoretical saturation. Via in-depth analysis and continual comparison, the driving factors of food waste behavior among all additional 14 interviewees fall within the scope of the main and sub-categories, and the logical relationship between the factors conforms to the relationship shown in Figure 1, that is, no new concepts or categories that could influence the core category were unearthed. Hence, it can be concluded that the model has achieved theoretical saturation.

3.5. Statistical Analysis Results of Factor Importance

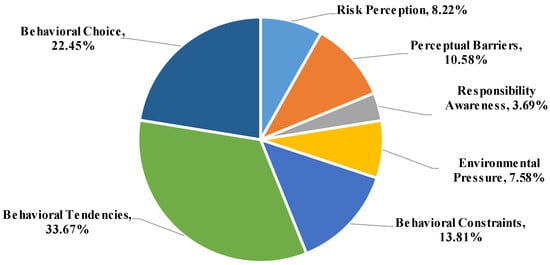

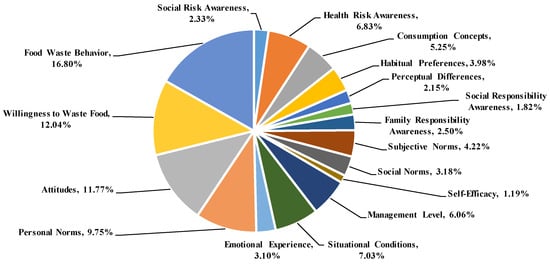

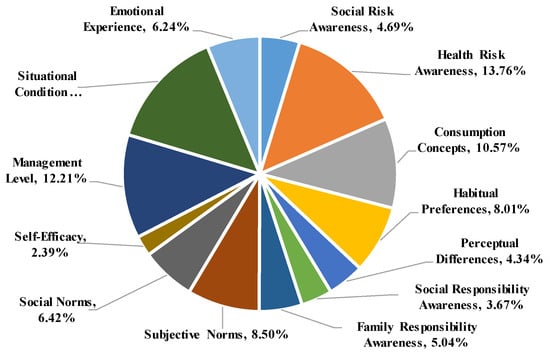

The axial coding identified seven main categories: perception awareness, perceptual barriers, responsibility awareness, environmental pressure, behavioral constraints, behavioral tendencies, and behavioral choices, which can be seen as the main category factors of food waste in Chinese urban households. The proportion of reference points in each category is shown in Figure 2, reflecting its degree of influence. It can be seen that the total proportion of reference points involved in behavioral tendencies and behavioral choice exceeds 50% of all reference points. This is because behavioral tendencies and behavioral choice are outcome factors in the entire conceptual model. When explaining other factors, respondents often mention concepts in these two main categories in their text materials. In comparison, among the remaining five main categories that have impacts on food waste behavior tendencies and behavior choice, the number of reference points in responsibility attribution is relatively small, only about 3.69%, indicating that the impact of responsibility attribution is not high. Furthermore, Figure 3 shows the proportion of reference points in all sub-categories. It can be seen that food waste behavior, willingness to waste food, attitude, and personal norms have the highest number of reference points. The above subcategories are also included in the two main categories of behavior tendency and behavior choice.

Figure 2.

The proportion of reference points in the main category.

Figure 3.

The proportion of reference points in the sub-category.

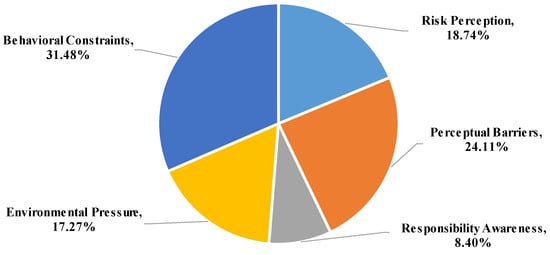

To further analyze the key influencing factors of food waste behavior in Chinese urban households, considering that behavioral tendencies and choice were the results of multiple factors, this section removed these two main categories and analyzed the number of reference points for the remaining five main categories and their sub-categories. The results are shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Figure 4.

The proportion of reference points in the main category without Behavioral Tendencies and Behavioral Choice.

Figure 5.

The proportion of reference points in the sub-category without Behavioral Tendencies and Behavioral Choice.

4. Discussion

4.1. Basic Discussion on Research Results

- (1)

- Open coding

The results of open coding (Section 3.1) reveal that the initial concept of food waste in urban households extracted from the original data text reflects the basic understanding of household food waste by residents, including their cognition of the consequences of food waste, their cognition of physiological and psychological conditions, their moral and ethical cognition of food waste behavior, and their cognition of food waste behavior. Among them, the related concepts of food waste consequence cognition can be further summarized into two sub-categories: social risk awareness and health risk awareness. The related concepts of physiological and psychological conditions cognition can be further summarized into six sub-categories: consumption concepts, habitual preferences, perceptual differences, management level, situational conditions, and emotional experience. The related concepts of moral and ethical cognition of food waste behavior can be further summarized into eight sub-categories: social responsibility awareness, family responsibility awareness, personal norms, attitudes, subjective norms, social norms, self-efficacy, and willingness to waste food. The related concepts of food waste behavior cognition can be further summarized into one category: food waste behavior. Therefore, all initial concepts ultimately formed 17 sub-categories, comprehensively and systematically characterizing the internal and external influencing factors in the process of food waste in urban households.

- (2)

- Axial coding

The axial coding results (Section 3.2) reveal that the 17 sub-categories follow the driving paradigm of “perception-intention-condition-behavior”. Specifically, perception refers to an individual’s psychological cognition of the consequences caused by a certain phenomenon, as well as their internal moral and ethical requirements, intention is the degree to which an individual is inclined to take a certain behavior, condition is the constraint factors that an individual may face when forming a certain intention or taking a specific action driven by a specific intention, and action is the individual’s specific action.

In this paper, social risk awareness, health risk awareness, social responsibility awareness, family responsibility awareness, subjective norms, social norms, and self-efficacy to a certain extent reflect the individual’s perception in the process of household food waste. Social risk awareness and health risk awareness reflect the residents’ perception of the possible consequences of food waste, which can be summarized as the main category of risk perception. Social responsibility awareness and family responsibility awareness are the individual’s perception of the responsibility and obligation to reduce food waste, which can be summarized as the main category of responsibility awareness. Subjective norms, social norms, and self-efficacy are the individual’s perception of the subjective pressure and self-ability to reduce food waste, which can be summarized as the main category of environmental pressure. Personal norms, attitudes, and willingness to waste food reflect the intention formed by individuals based on their own beliefs, values, and moral standards, which can be summarized as the main category of behavioral tendencies. Consumption concepts, habitual preferences, perceptual differences, management levels, situational conditions, and emotional experiences all belong to the constraining factors of individuals in the formation of food waste behavior. Among them, consumption concepts, habitual preferences, and perceptual differences can affect the degree to which an individual’s perception becomes intentions, which can be summarized as the main category of perceptual barriers. Management levels, situational conditions, and emotional experiences can affect the degree to which an individual’s willingness becomes behaviors, which can be summarized as the main category of behavioral constraints. Food waste behavior refers to the specific behavior of household food waste, which can be summarized as the main category of behavior choice. Therefore, the above 17 sub-categories ultimately form 7 main categories: perceptual awareness, perceptual barriers, responsibility awareness, environmental pressure, behavioral constraints, behavioral tendencies, and behavioral choices, which not only more intuitively reflects the influencing factors of food waste behavior in urban households but also to a certain extent reflects the internal logical relationship between factors.

- (3)

- Selective coding

As presented by the selective coding results (Section 3.3), this paper analyzes the driving factors of food waste behavior in Chinese urban households through grounded theory, finding that the “Story Line” around the core category can be summarized as follows: Risk perception significantly impacts both responsibility awareness and behavioral tendencies; responsibility awareness and environmental pressure are also important factors influencing behavioral tendencies; behavioral tendencies significantly affect behavioral choice. Furthermore, perceptual barriers modulate the pathways from risk perception to responsibility awareness and behavioral tendencies; behavioral constraints modulate the impact pathway from behavioral tendencies to behavioral choice.

- (4)

- Validity testing

The coding consistency test results (Section 3.4) show that the coding consistency rate is between 84.55% and 97.43%, exceeding 70%, revealing that the overall consistency of the coders was reasonable [43] and the researcher’s own coding had high reliability.

- (5)

- Factor importance

According to the proportion of reference points in the sub-category without Behavioral Tendencies and Behavioral Choice (Figure 4 and Figure 5 in Section 3.5), it can be seen that without considering behavioral tendencies and choice, the number of reference points for behavioral constraints is the highest, accounting for 31.47%, followed by perceptual barriers at 24.11%, revealing that in the process of food waste formation in urban households in China, perceptual barriers and behavioral constraints play key roles. Specifically, in terms of sub-category dimensions, the proportion of reference points in the six sub-categories of health risk awareness, consumption concepts, habitual preferences, subjective norms, management level, and situational conditions exceeds the average level (7.69%), revealing that these factors are important driving factors for food waste in urban households. Based on the correlation between the factors in Figure 1, the driving mechanism of food waste can be expressed as follows: the attention of residents to family health drives a series of psychological activities related to food waste, forming behavioral tendencies (such as subjective norms). Their own consumption concepts and habitual preferences play an important regulatory role in this driving process. The planning and management ability of residents for food production, as well as the objective conditions of technology, economy, and physiology, will significantly affect the degree to which behavioral tendencies are transformed into specific actions.

4.2. Further Discussion on the Interaction Relationship between Factors

In addition to the basic discussion in Section 4.1, Section 4.2 will further discuss the interaction relationship between the main and sub-categories in the conceptual model (shown in Figure 1 in Section 3.3) of the influencing factors of food waste behavior in Chinese urban households obtained by grounded theory, including the direct interaction relationship between influencing factors (Section 4.2.1) and the regulatory relationship between influencing factors (Section 4.2.2), aiming to further reveal the formation mechanism of food waste behavior in Chinese urban households, which can provide a basis for proposing intervention policies to reduce household food waste in the future.

4.2.1. Analysis of the Direct Interaction Relationship between Factors

- (1)

- The direct effect of risk perception on responsibility awareness

According to the results of axial coding (Section 3.2), in the model of food waste behavior among urban families, risk perception refers to an individual’s perception of the social and health risks that food waste may bring, while responsibility awareness refers to an individual’s understanding of their responsibility to reduce food waste in the process of food consumption and disposal, including corresponding social and family responsibilities. The results shown in Figure 1 in Section 3.3 reveals that risk perception has direct effect on responsibility awareness, which is consistent with the basic assumption of norm activation theory, that is, individuals’ perception of the potential social and health risks associated with food waste can enhance their awareness of social and familial responsibilities, thus motivating them to assume greater responsibilities in their social and familial roles and leading to more responsible behaviors in food consumption [34]. In simple terms, when people are more aware of the risks posed by food waste, they pay greater attention to their roles in society and family, adopting more conservative and responsible consumption practices. Specifically:

- Direct interaction relationship between Social Risk Awareness and Social Responsibility: Awareness of social risks can enhance individuals’ understanding of the links between food waste and environmental and societal issues, thereby heightening their sense of social responsibility, consistent with the research by Kim et al. [44]. For instance, when people recognize the connection between food waste and societal issues such as resource scarcity and environmental pollution, they may feel obligated to act to reduce food waste, thus fostering sustainable development at the societal level.

- Direct interaction relationship between Health Risk Awareness and Family Responsibility: According to Duret et al. [45], there is a significant correlation between food waste and human health. If individuals understand the potential health risks associated with food waste, such as food safety issues and nutritional imbalances, they might take greater responsibility within their families by careful planning of food purchases and consumption to ensure the health of family members. The mechanism has also been revealed to some extent by Savelli et al. [46].

- (2)

- The direct effect of risk perception on behavioral tendencies

According to the results of axial coding (Section 3.2), in the model of factors influencing food waste behavior in urban families, behavioral tendencies refer to the psychological tendencies exhibited by individuals towards food waste. The results shown in Figure 1 in Section 3.3 reveals that risk perception has direct effect on behavioral tendencies. Similarly, both the norm activation theory and the planned behavior theories reveal that awareness of consequences can significantly influence individual norms, thereby giving rise to behavioral tendencies [47]. The research conclusion of this article to some extent aligns with the assumptions of the above theory, that is, risk perception enhances individuals’ identification with internal norms when facing food waste, thereby transforming their behavioral attitudes and intentions, and effectively promoting more responsible food consumption behaviors [44]. Specifically:

- Direct interaction relationship between Social Risk Awareness and Individual Norms, Attitudes: Social risk awareness refers to an individual’s recognition of the adverse effects food waste can have on society and the environment. When individuals realize the connection between food waste and issues such as resource scarcity, environmental pollution, and climate change, they may internalize a personal norm—feeling an obligation to reduce food waste. According to Piras et al. [48], such internalized norms can change their attitudes and ultimately have a positive inhibitory effect on their food waste behaviors.

- Direct interaction relationship between Health Risk Awareness and Willingness to Waste Food: Health risk awareness refers to an individual’s understanding of the potential dangers that food waste could pose to their own and their family members’ health. According to Qian et al. [49], when family members pay more attention to food safety and hygiene, they may intentionally discard some food, and the amount of household food waste will also increase. This paper also reveals a similar conclusion, that is, health risk awareness reflects an individual’s perception of the potential harm that food consumption may bring to their own and family members’ health, and an individual’s health risk awareness may affect their willingness to waste household food.

Furthermore, these perceptual awareness factors do not exist in isolation; they can enhance or weaken each other. For example, social risk awareness and health risk awareness might jointly influence an individual’s behavioral norms, leading them to consider both their social responsibilities and health consequences when contemplating food waste issues.

- (3)

- The direct effect of responsibility awareness on behavioral tendencies

The results shown in Figure 1 in Section 3.3 reveals that responsibility awareness has direct effect on behavioral tendencies. Similarly, the norm activation theory reveals that awareness of responsibility can be seen as a central element driving individual behavioral tendencies [34,44]. The influencing factor system of food waste behavior in urban households obtained in this article also found that by reminding individuals of their social and family responsibilities, they can be motivated to translate their internal behavioral norms and attitudes into actual actions. Considering the connotation of sub-categories, the direct mechanism of responsibility awareness on behavioral tendencies can be understood from several perspectives:

- Direct interaction relationship between Social Responsibility Awareness and Individual Norms, Attitudes: Social responsibility involves an individual’s understanding of their role in society and the responsibilities they should fulfill [50]. When individuals feel a responsibility to reduce food waste to promote environmental protection, resource conservation, and social poverty reduction, this sense of social responsibility can become an internal behavioral norm, thereby influencing individual attitudes. For example, individuals may value food more and hold critical attitudes towards food waste, and then reduce their willingness to waste food.

- Direct interaction relationship between Family Responsibility Awareness and Individual Norms, Attitudes: Family responsibility involves an individual’s recognition of the duties they should fulfill within family life. In the context of food waste in this paper, this is reflected in the responsibility felt towards the health and well-being of family members. When individuals realize that reducing food waste can improve the nutritional status of family members and maintain stable family finances, they may internalize a family behavioral norm, such as organizing food purchases and consumption efficiently to reduce waste. Similarly, González-Santana et al. found that a responsible attitude towards family members is an important factor influencing individuals’ attitudes towards household food waste [51].

- Direct interaction relationship between Responsibility Awareness and Willingness to Waste Food: According to Parfitt et al. [52], responsibility awareness can directly impact individuals’ behavioral willingness regarding food waste. The research results of this article reveal that if individuals strongly feel that reducing food waste is their responsibility, they may be more inclined to implement specific measures, such as being more careful when buying food, improving food storage and preparation, and donating leftover food to those in need, thereby reducing food waste.

- (4)

- The direct effect of environmental pressure on behavioral tendencies

According to the results of axial coding (Section 3.2), in the system of factors influencing food waste behavior in urban families, environmental pressure refers to the driving or constraining forces that individuals face from society, culture, and beliefs, which may promote or hinder the occurrence of food waste tendencies. The results shown in Figure 1 in Section 3.3 reveal that subjective norms and social norms act on individual personal norms and attitudes under environmental pressures, thus affecting their willingness to waste food. Additionally, self-efficacy influences individuals’ confidence in their ability to successfully implement food waste reduction behaviors, thereby shaping their behavioral tendencies. The above impact relationship aligns with the basic assumptions of planned behavior theory [53], that is, behavioral attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (which can be seen as self-efficacy) are the three main variables that determine behavioral intention. Specifically:

- Direct interaction relationship between Subjective Norms and Personal Norms: As suggested by Ajzen [54], subjective norms involve an individual’s internal beliefs and guidelines about how they should act. In this paper, the qualitative research results may reveal that if individuals believe that reducing food waste is the appropriate action, they will internalize a personal norm, feeling obligated to take steps to reduce food waste. Then, this personal norm can influence their attitudes and inclinations toward food waste.

- Direct interaction relationship between Social Norms and Personal Norms: Social norms represent societal expectations and demands regarding individual behavior [55]. If society widely regards reducing food waste as a crucial task, these expectations may be internalized as personal behavioral norms by individuals, prompting them to feel responsible for meeting societal expectations and reducing food waste in their actions. Coşkun and Özbük [56] also confirms the existence of this mechanism, that is, the presence of social norms shapes individual attitudes and affects their tendencies toward food waste.

- Direct interaction relationship between Self-Efficacy and Personal Norms: Albert Bandura proposed the self-efficacy theory from the perspective of social learning in 1977 [57], pointing out that self-efficacy is a subjective evaluation of an individual’s ability to complete a certain aspect of work, which directly affects their behavioral motivation [58]. In the household food waste system of this paper, self-efficacy can enhance individuals’ motivation and commitment levels, thereby affecting their willingness to reduce food waste. In other words, if individuals are confident in their ability to reduce food waste, they may be more willing to follow personal norms and take concrete steps to practice food waste reduction.

- Direct interaction relationship between Subjective Norms, Social Norms, and Attitudes: Under the framework of planned behavior theory, subjective norms and social norms can interact to jointly influence an individual’s attitude [59]. According to the influencing factor system in this paper, if individuals believe that reducing food waste is the right action and their society also expects them to do so, they may develop a negative view of food waste, thereby increasing their motivation to reduce it. This conclusion is also consistent with the research findings of Graham-Rowe et al. [53] and Coşkun and Özbük [56] on the influencing factors of food waste within the framework of planned behavior theory.

- Direct interaction relationship between Self-Efficacy and Attitudes, Willingness to Waste Food: Since its inception, self-efficacy theory [58] has aroused great interest among motivational psychologists and is considered an important factor in explaining individual behavioral tendencies. A series of theories have emerged around the impact of self-efficacy on individual behavioral tendencies. For example, the Health Belief Model posits that self-efficacy is an important driving force for individuals to adopt specific healthy behaviors [60], and the Planned Behavior Theory suggests that perceived behavioral control (which can be seen as self-efficacy) is an important factor affecting behavioral intentions [61]. In this paper, self-efficacy refers to an individual’s perception of the difficulty of completing a behavior that helps reduce food waste and their confidence in completing that behavior. Self-efficacy not only affects personal norms but also directly influences individuals’ views and desires to reduce food waste. If individuals believe they can effectively reduce food waste, they may have a more positive outlook and be more motivated to take relevant actions.

Furthermore, these factors are not isolated; they can enhance or weaken each other. According to Soorani and Ahmadvand [62], subjective norms and social norms may jointly affect personal norms, causing individuals to consider both their beliefs and societal expectations when thinking about food waste issues. Self-efficacy might increase individuals’ desires to adhere to norms, encouraging them to actively take measures to reduce food waste.

- (5)

- The direct effect of behavioral tendencies on behavioral choice

The results shown in Figure 1 in Section 3.3 reveal that the direct impact of behavioral tendencies on behavioral choices involves an individual’s intrinsic motivations and decision-making processes. In the context of urban family food waste behavior, behavioral tendencies, including personal norms, attitudes, and the desire to reduce food waste, reflect an individual’s readiness or inclination to engage in food waste behaviors under specific circumstances. These tendencies influence individual behavior choices in the following ways:

- Direct interaction relationship between Personal Norms and Behavior Choice: As suggested by norm activation theory, personal norms are internal rules of behavior accepted by an individual, guiding how they should act in particular situations [63]. According to the influencing factor system in this paper, if personal norms align with the goal of reducing food waste, individuals are likely to choose behaviors that conform to these norms, such as purchasing food in appropriate amounts, properly storing, and preparing food to minimize waste.

- Direct interaction relationship between Attitudes and Behavior Choice: In the framework of planned behavior theory, attitudes are an individual’s evaluations and emotional tendencies towards a particular subject. When individuals have a negative view of food waste, they may avoid such behavior and tend to choose more economical dietary patterns. In other words, as stated by Kroesen et al. [64], attitudes can strengthen or weaken behavioral tendencies, thereby influencing behavior choices.

- Direct interaction relationship between Willingness to Waste Food and Behavior Choice: Whether it is norm planning theory or planned behavior theory, behavioral intention is the most direct influencing factor of behavioral choice. In the food waste system, the willingness to waste food reflects an individual’s proactiveness regarding food waste. If a person has a strong desire to reduce food waste, they are more likely to take concrete actions to reduce food waste.

Overall, behavioral tendencies can translate into specific motivations and plans, which are precursors to actual behavior. When individuals are highly motivated to reduce food waste and have clear objectives for executing such behavior, they will engage in corresponding actions, such as being more careful when purchasing and consuming food [65]. Faced with different behavior choices, individuals make decisions based on their personal norms, attitudes, and willingness to reduce food waste, and these decisions are reflected in their food waste behaviors.

4.2.2. Analysis of the Regulatory Relationship between Factors

- (1)

- The regulatory role of perceptual barriers in the impact of risk perception on responsibility awareness

The results shown in Figure 1 in Section 3.3 reveals that perceptual barriers play a moderating role in the impact of risk perception on responsibility awareness, meaning that individual perceptual obstacles can either strengthen or weaken the effect of risk perception on the sense of responsibility. For example, if an individual’s consumption beliefs and habitual preferences are inconsistent with the sense of responsibility for reducing food waste, they may feel confused or conflicted about this responsibility. Conversely, if individuals have fewer perceptual barriers, they may be more aware of their responsibilities and take corresponding actions. Specifically:

- The regulatory role of Consumption Beliefs in the impact of risk perception on responsibility awareness: Consumption beliefs shape an individual’s cognition of consumer behaviors and their associated responsibilities [66]. Positive consumption attitudes can encourage people to pay attention to the impact on the environment and society during the consumption process, while negative consumption attitudes may lead people to overlook the impact of consumption behavior on society and the environment. For example, under a restrained and responsible consumption attitude, consumers may choose environmentally friendly and sustainable products or opt for second-hand products when purchasing products, which can reduce waste of resources and negative impact on the environment. Under an unrestrained and socially irresponsible consumption attitude, consumers tend to use disposable products in large quantities and turn a blind eye to excessively packaged products, resulting in environmental pollution and resource waste. In the system of influencing factors of food waste, although individuals have a clear understanding of the risks that food waste may cause, they may be influenced by the concept of excessive consumption, which makes them unable to strongly believe that they are responsible for reducing food waste.

- The regulatory role of Habitual Preferences in the impact of risk perception on responsibility awareness: Habitual preferences can lead to biases in behavioral choices, and interventions in education and lifestyle are important ways to change habitual preferences [67]. In the system of influencing factors of food waste, when individuals are aware of the potential risks that food waste may cause, their own habitual preferences (such as a tendency towards high consumption or the use of disposable products) will encourage them to continue their behavior of food waste while ignoring their responsibility to reduce food waste.

- The regulatory role of Perceptual Differences in the impact of risk perception on responsibility awareness: The health belief model reveals that an individual’s perceived sensitivity and perceived severity can affect their behavioral choices, but these factors are usually involved in individual health behavior [68]. The research results of this paper confirm that individual perception differences are an important influencing factor in the process of food waste in urban households. If individuals have a keener awareness of the issues related to food waste, or a clearer understanding of the social and health problems caused by food waste, they may feel a deeper sense of social and family responsibility, thus being more willing to accept their role in reducing food waste and inclined to take appropriate actions.

- (2)

- The regulatory role of perceptual barriers in the impact of risk perception on behavioral tendencies

The results shown in Figure 1 in Section 3.3 reveals that in urban family food waste behavior, risk perception directly influences behavioral tendencies, and perceptual barriers moderate this influence. These barriers, such as deviations or misconceptions in consumption beliefs, habitual preferences, and perceptual differences, can alter the direct impact of risk perception on behavioral tendencies [69]. Specifically:

- The regulatory role of Consumption Beliefs in the impact of risk perception on behavioral tendencies: The study by Stangherlin et al. [70] shows that during the food purchasing process, the consumer beliefs (like the acceptance of inferior foods such as damaged packaging and approaching shelf life) are important factors causing food waste. The research results of this paper also confirm that consumption beliefs have an impact on food waste, but unlike previous studies [70], this paper further reveals the specific mechanism of consumption beliefs. When individuals consider excessive buying and consumption of food as reasonable or acceptable, it can reduce their perception of the social and health risks associated with food waste, thereby weakening their attitudes and motivations to take actions to reduce food waste.

- The regulatory role of Habitual Preferences in the impact of risk perception on behavioral tendencies: According to Kymäläinen et al. [71], long-term habitual preferences formed by individuals (such as vegetarianism) may be one of the important factors causing food waste. The research results of this paper further elucidate the role of habitual preference in household food waste, that is, individuals may waste food during purchasing and consumption due to long-established dietary preferences, even if they are aware of the issue of food waste.

- The regulatory role of Perceptual Differences in the impact of risk perception on behavioral tendencies: Similar to the role of perceptual barriers in the health belief model, this paper finds that perceptual differences may be widespread in the influencing factor system of food waste in urban households. For instance, some people may not view food waste as an urgent problem or may not be sensitive to the severe consequences of food waste. At this time, although they may realize that food waste can cause certain consequences, they may fail to recognize the serious impact their behavior has on the environment and society, which weakens the driving force of risk perception on behavioral tendencies.

Overall, as studied by Lak et al. [72], perceptual barriers may either reduce or enhance the effect of risk perception on behavioral tendencies. For example, when individuals accurately understand the severity of food waste but their consumption beliefs and habitual preferences prompt them to continue wasting food, perceptual barriers play a diminishing role. Conversely, if an individual’s perceptual barriers make them more aware of the food waste issue and motivate them to change their behavior, then these barriers enhance the effect.

- (3)

- The regulatory role of behavioral constraints in the impact of behavioral tendencies on behavioral choice

The results shown in Figure 1 in Section 3.3 reveals that in the framework of factors influencing food waste behavior in urban families, behavioral tendencies directly impact behavioral choices, while behavioral constraints moderate this influence through external factors such as management level, situational conditions, and emotional experiences. Specifically:

- The regulatory role of Management Level in the impact of behavioral tendencies on behavioral choice: According to Ko and Lu [73], professional cooking skills are important factors in effectively reducing food waste. The analysis of food waste in urban households in this paper also reveals that the individual’s ability to plan and manage food procurement, processing and storage, preparation, and cooking at various stages will to some extent affect the occurrence of food waste behavior. For instance, when an individual lacks a reasonable food purchase plan or mature cooking ability, even if they are willing to reduce food waste, their lack of self-management ability may still lead to actual food waste.

- The regulatory role of Situational Conditions in the impact of behavioral tendencies on behavioral choice: Individual or family specific circumstances, such as emotional state, economic situation, food storage and cooking conditions, and convenience conditions (such as whether the family has pets), may have an impact on their food waste behavior [74,75]. For example, when someone is in a bad mood, it might affect their appetite, leading to potential food waste even if they intend to reduce it; intelligent devices can better serve and supervise various aspects of household meals, reducing the occurrence of food waste in households; if storing food is convenient, even if individuals have a tendency to waste, they may choose to save food to reduce food waste. In addition, with the growth of household income and the improvement of quality of life, the demand for diversified food among residents continues to increase, and higher requirements will be placed on the freshness and unique flavor of ingredients. At this point, although residents may be willing to reduce food waste, some food waste behaviors still occur in reality.

- The regulatory role of Emotional Experiences in the impact of behavioral tendencies on behavioral choice: When facing food waste, there may be a potential difference between an individual’s emotional needs and the emotions they actually acquire, as well as a series of direct feelings that individuals receive from food stimuli through visual, auditory, olfactory, gustatory, and tactile senses. These emotional differences or feelings may lead to individual dissatisfaction or loss, affecting the degree to which an individual’s intention is transformed into specific behavior. For instance, when individuals worry that reducing food waste could lead to adverse consequences, such as health impairment, decreased quality of life, or loss of face, they might continue to waste food despite their desire to reduce it [76,77]. Moreover, according to Turner [78], sensory factors such as the appearance, smell, and taste of food can influence individual food choices. If food appears unappealing or tastes poor, individuals may be compelled to discard it, even if they are reluctant to waste. In the context of China, some factors may be more obvious, such as the face culture in modern society becoming a consumer cultural psychology of some residents, especially reflected in excessive banquets, hospitality, and gift giving. This is inconsistent with the mainstream values of diligence and thrift advocated by Chinese society. However, it is obvious that the willingness of residents to reduce food waste under the mainstream values will be greatly influenced by specific emotional cultures, making it difficult to fully translate it into concrete actions to reduce food waste.

In summary, the factors influencing food waste in Chinese urban households constructed in this paper have the following characteristics:

On the one hand, the 7 main categories and 17 subcategories included in the system (shown in Table 3) reflect the factors affecting food waste in Chinese urban households. The influence paths between some factors are consistent with existing mature theoretical frameworks or research conclusions [34,44,47,56], indicating that the research method in this paper is reliable. It should be noted that examining food waste phenomena based on mature theoretical frameworks (such as norm activation theory [44], planned behavior theory [56], health belief model [69], etc.) can reveal the formation mechanism of food waste behavior in specific dimensions, but it is difficult to ensure the comprehensiveness of factors. By contrast, this paper investigates the driving factors of food waste in Chinese urban households through grounded theory, without setting any assumptions in advance. Instead, it relies entirely on actual interview data to form a structured and systematic system, and the theoretical saturation test also reveals that the constructed theoretical system does not omit key variables (such as consumer attitudes, habitual preferences, health beliefs, and management level). Therefore, this paper focuses on the issue of food waste in urban households in China, and from a more open perspective, forms a more comprehensive system of influencing factors.

On the other hand, while maintaining consistency with the conclusions of mature theoretical frameworks, this paper also obtains some new findings on the formation mechanism of food waste in urban households in the Chinese context. Firstly, unlike the norm activation theory or planned behavior theory [44,56], risk perception in this paper is subdivided into social risk perception and health risk perception, and the corresponding responsibility awareness also includes social responsibility awareness and health responsibility awareness (shown in Table 3 and Figure 1). The results of the driving factors of food waste behavior in urban households (shown in Figure 1) reveal that with the continuous advancement of urbanization in China and improvement of life quality of urban families, urban residents are no longer only considering social problems such as resource waste and environmental pollution caused by food waste but also starting to consider food consumption more from the perspective of the health of family members, thus introducing “health” factors into the formation process of food waste behavior. Secondly, Table 4 and Figure 1 in this paper reveal the impact of perceptual barriers on the formation of food waste behavior in urban households, expanding the application of factors such as consumption habits and perceptual differences in consumer psychology and health belief models in the field of food waste. Thirdly, previous studies have confirmed that cooking conditions, emotions, and economic conditions are the influencing factors of food waste [74,75,77]. This paper further reveals the specific functions of these factors in food waste through grounded theory coding; that is, as a series of behavioral constraints, they affect the degree to which behavioral tendencies are transformed into behavioral choices (shown in Table 4 and Figure 1). Finally, the role of some social and cultural factors that reflect Chinese characteristics has also been found in the system of this paper (shown in Table 3). For example, face culture is an important Chinese-style emotional experience that constrains the transformation of food waste behavior tendencies into specific behavioral choices; the mainstream values of diligence and frugality will form a strong social norm, prompting individuals to form a belief in reducing food waste; the traditional virtues of the Chinese nation, as an inherent morality, will inspire individuals to form personal norms to reduce food waste. The above new findings more comprehensively and systematically depict the mechanism of food waste behavior in Chinese urban households and enrich and expand the conclusion system of the formation mechanism of food waste behavior in Chinese scenarios, which can provide important reference for further exploring intervention measures for food waste in Chinese urban households, thereby having significant theoretical contributions and practical policy values.

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

This study conducted in-depth personal interviews with 56 respondents using survey questionnaires and performed qualitative analysis of the data using grounded theory methods to explore the factors influencing food waste behavior in urban families. The theoretical model constructed and the research findings provide a theoretical supplement to studies in the following relevant fields.

- (1)

- In the grounded research on factors influencing food waste behavior in urban families, open coding identified 17 initial categories, which were further refined into 7 main categories: Risk Perception, Perceptual Barriers, Responsibility Awareness, Environmental Pressure, Behavioral Constraints, Behavioral Tendencies, and Behavioral Choice.

- (2)

- Through selective coding, the main categories formed by axial coding were further integrated and refined, forming an impact relationship structure consisting of five direct impact pathways and three regulatory pathways. Specifically, Risk Perception directly affects Responsibility Awareness and Behavioral Tendencies, Responsibility Awareness and Environmental Pressure directly affect Behavioral Tendencies, Behavioral Tendencies directly affect Behavioral Choice, Perceptual Barriers play a moderating role in the impact of Risk Perception on Responsibility Awareness and Behavioral Tendencies, and Behavioral Constraints play a moderating role in the impact of Behavioral Tendencies on Behavioral Choices.

- (3)

- According to the statistics of reference points for various factors, Perceptual Barriers and Behavioral Constraints play key roles in the formation of food waste in urban households in China. On the subcategory dimension, health risk awareness, consumption concepts, management level, and situational conditions are important driving factors for food waste in urban households. The concern of residents towards family health drives a tendency towards food waste, and their own consumption concepts can affect the strength of this driving force. The ability of residents to plan and manage food production, as well as their own objective and physiological conditions, will significantly affect the degree to which behavioral tendencies are transformed into specific actions.

5.2. Policy Recommendations

Based on the correlation structure between the influencing factors of food waste in Chinese urban households constructed through grounded theory in this paper, the following policy recommendations are proposed to help reduce food waste in Chinese urban households.

- (1)

- Strengthen public education and awareness and enhance residents’ awareness and responsibility towards food waste risks. The research results of this paper reveal that risk perception and responsibility awareness are important factors affecting food waste. Improving residents’ understanding of the consequences and responsibilities of food waste can promote the formation of individual behavioral tendencies to reduce food waste. On the one hand, the severity of food waste can be introduced through media platforms such as advertisements, social media, and television programs, as well as seminars, lectures, and online courses, to convey the negative impact of food waste on the environment and society. On the other hand, through lectures, training, and other means, it is conveyed to residents that their behavior is directly related to food waste and reducing food waste is everyone’s responsibility. This can enhance residents’ sense of responsibility for reducing food waste, thus stimulating their enthusiasm to reduce food waste.

- (2)

- Effectively utilizing environmental pressure to strengthen the tendency to reduce food waste. The research results of this paper show that environmental pressure can have a significant impact on individual behavior and is an important factor in stimulating residents to develop a tendency to reduce food waste. On the one hand, strengthen the construction of laws and regulations, such as legislation to ensure that individuals fulfill their responsibilities in food recycling and waste reduction or establishing a comprehensive food waste monitoring and reporting system, in order to strengthen subjective and social norms for reducing food waste. On the other hand, strengthen the values of advocating food conservation and opposing waste, creating an anti-waste atmosphere in the society which can encourage people to cherish food, and reduce food waste through practices like “Clean Your Plate Campaign”. In addition, residents should learn and practice appropriate food storage, preparation, and consumption technologies to improve food utilization efficiency and actively participate in food recycling and volunteer services, which can enhance their enthusiasm for and confidence in reducing food waste.

- (3)

- Continuously optimizing the social consumption environment to create and improve external conditions to reduce food waste. According to the research results of this paper, the situational condition is an important behavioral constraint factor that significantly affects the degree to which food waste behavior tendencies are transformed into specific behavioral choices. On the one hand, it is necessary to provide objective conditions for creating a social atmosphere that reduces food waste. For example, supermarkets can set up dedicated areas to sell expired food at promotional prices to encourage purchases; restaurants can offer meals of various sizes to meet different customer needs; improving the quality of food packaging and storage technology can extend the shelf life of food, thereby reducing food waste caused by improper storage. On the other hand, government agencies should provide necessary resources to support reducing food waste, such as conducting food storage and processing training, promoting food recycling technologies and projects. In addition, households with means can effectively dispose of kitchen waste by purchasing smart kitchen equipment or keeping pets, thereby reducing leftover food. Through these measures, an environment conducive to food conservation can be created, thereby reducing food waste.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.G. and H.G.; methodology, S.G.; formal analysis, S.G.; investigation, S.G.; resources, H.G.; data curation, S.G. and H.G.; writing—original draft preparation, S.G.; writing—review and editing, S.G. and H.G.; visualization, H.G.; supervision, H.G.; project administration, H.G.; funding acquisition, H.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Jilin Science and Technology Society Project (No. SKH2022202).

Institutional Review Board Statement

According to the Measures for the Ethical Review of Life Sciences and Medical Research Involving Humans (https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2023-02/28/content_5743658.htm, accessed on 18 February 2023) jointly issued by Chinese Health Commission, Ministry of Education, Ministry of Science and Technology and Traditional Chinese Medicine Bureau, ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the absence of sensitive data and to the processing of data with the assurance of the confidentiality and anonymization of the personal information of all the subjects involved in the study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the possibility of identifying participants through the interview transcripts, they will not be publicly available to ensure their right to be anonymous. However, the authors are happy to send redacted transcripts (that remove all identifiable information) upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Eičaitė, O.; Baležentis, T. Disentangling the sources and scale of food waste in households: A diary-based analysis in Lithuania. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 46, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Z.; Dierenfeld, E.S.; Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Shurson, G.C. A critical analysis of challenges and opportunities for upcycling food waste to animal feed to reduce climate and resource burdens. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 203, 107418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2019: Moving Forward on Food Loss and Waste Reduction; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jansson-Boyd, C.V.; Mul, C. Drivers That Affect Households to Reduce Food Waste: A UK Qualitative Study. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Zhang, H. Characterization, environmental impact and reduction strategies for the delivery food waste generated by urban and township residents in Jiuquan, China. Waste Manag. 2024, 174, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, D.; Wang, Q. Diet anthropological study of food waste problem in Chinese dining table. J. Qinghai Minzu Univ. 2021, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, L.; Liu, X.; Lu, S.; Cheng, G.; Hu, Y.; Liu, J.; Dou, Z.; Cheng, S.; Liu, G. China’s food loss and waste embodies increasing environmental impacts. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvennoinen, K.; Nisonen, S.; Katajajuuri, J.-M. Food waste amount, type, and climate impact in urban and suburban regions in Finnish households. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 378, 134430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Food Waste Index Report 2021. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/unep-food-waste-index-report-2021 (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Bhatia, A.; Sharma, S. Identifying determinants of household food waste behavior in urban India. Clean. Waste Syst. 2023, 6, 100105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jiang, Y.; Qing, P. Estimates of household food waste by categories and their determinants: Evidence from China. Foods 2023, 12, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Semakula, H.M.; Fullana-i-Palmer, P. Chinese household food waste and its’ climatic burden driven by urbanization: A Bayesian Belief Network modelling for reduction possibilities in the context of global efforts. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 202, 916–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, D.; Apolzan, J.W.; Li, R.; Roe, B.E. Unpacking the decline in food waste measured in Chinese households from 1991 to 2009. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 160, 104893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Duan, H.; Andric, J.M.; Song, M.; Yang, B. Characterization of household food waste and strategies for its reduction: A Shenzhen City case study. Waste Manag. 2018, 78, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.X.; Luo, Y.; Huang, H.Q.; Huang, D.; Wu, L.P. The characteristics, environmental impacts, and countermeasures of rural household food waste in China. Res. Agric. Mod. 2022, 43, 948–956. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, C.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, M.; Guo, X.; Fu, H. The neural mechanism of food waste behavior in Chinese households from the perspective of gender differences. J. Nat. Resour. 2022, 37, 2531–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Shang, J.; Liu, C.; Wang, H.; Wang, S. Policy Recommendations for Reducing Food Waste: An Analysis Based on a Survey of Urban and Rural Household Food Waste in Harbin, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obuobi, B.; Zhang, Y.; Adu-Gyamfi, G.; Nketiah, E. Households’ food waste behavior prediction from a moral perspective: A case of China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 10085–10104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S.; Song, G.; Yang, D.; Yao, L.; Jiang, Z.; Zhao, M. Spatial–temporal and structural differences in the carbon footprints embedded in households food waste in urban and rural China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 35009–35022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Zhang, Z. Research progress and implications of household food waste studies: New contents, new methods and new perspectives. J. Nat. Resour. 2023, 38, 1178–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermanussen, H.; Loy, J.-P.; Egamberdiev, B. Determinants of food waste from household food consumption: A case study from field survey in Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, C.; De Laurentiis, V.; Corrado, S.; van Holsteijn, F.; Sala, S. Quantification of food waste per product group along the food supply chain in the European Union: A mass flow analysis. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 149, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]