Abstract

The main goal of this article is to give an overview of the importance of district heating and specifically emphasize its continued use with alternative fuels in the upcoming post-lignite era. The results of the cost–benefit analysis for district heating in the transition period after show promise and positivity. By examining key aspects undergoing changes and conducting a SWOT analysis related to this shift, this study sheds light on various benefits for the economy, society, and the environment in sustaining district heating post-lignite era. Additionally, it introduces a solution tailored to meet all district heating needs in Western Macedonia, Greece, during both the transitional phase and after phasing out existing lignite units as, per Greek National Energy and Climate Plan requirements. This devised solution ensures comprehensive coverage of all district heating demands.

1. Introduction

The global shift from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources is a massive challenge, with the goal of slowing down greenhouse gas, which is a primary reason for climate change all over the world. The fair shift plan is a framework that guarantees that employees and those communities where fossil fuels are in use do not lose interest when the global transition phase from fossil fuels to renewable fuels starts. One of the essential prerequisites to mitigate the human and community effects of the global shift from lignite to renewable fuel resources is an acknowledgement of a fair shift plan. The plan stimulates a fair and inclusive shift, considering workers’ working attitudes in financial and social terms and the creation of top-quality places in upcoming new sectors of the renewable industry. One of the crucial measures to mitigate climate change is a fair shift plan strategy of using lignite to generate energy from other types of fuels. The plan provides a fair and neutral ground for economic development and renewable energy use. Working with coal will bring some complications in the near future, but we can manage it if countries follow strategies of helper programs to fulfill emergency sectors. The replacement of fossil fuels with other types of resources and the use of renewable energy are needed to form a sustainable future. Today, global society is facing climate change with high complications, and is working with gaseous and radiation generation due to big industries located in human areas. Sustainability and renewable energy are not plans for today. They must be the work of global society and, more correctly, the work of the government, which writes the rules for humanity. Building a fair and inclusive shift in the renewable industry may be problematic, but initiating a transition plan in some sectors of the world economy has proved to be successful and is safe in size terms. The benefit of renewable energy is that it shows potential positive energy sources that can provide working industry without Sunday and professional leaves.

Recently, multiple research studies have examined the shift towards cleaner and more sustainable energy sources.

More specifically, ref. [1] explored the district heating system in the Copenhagen area, focusing on the relationship between heat conservation and heat delivery in buildings from an economic standpoint. In ref. [2] conducted an analysis of a novel method for classifying district heating systems according to their geographical location, size, heat concentration, and demand from end-users, with a specific emphasis on accurately predicting and optimizing energy loads. In the study of [3], the researchers examined the use of solar and biomass district heating systems in regions with low to moderate population density in the Mediterranean. The methodology was implemented in a case study located in southern Spain. In [4], the researchers analyzed Greece’s efforts to gradually phase out its use of lignite, examining the environmental, economic, and social state of the municipality of Megalopolis and offering solutions for a just energy transition.

In ref. [5] suggested techniques for utilizing exergy loss in a district heating system in northern China, which has substantial energy consumption and contributes to severe winter smog. By integrating with natural gas, thoroughly investigating the energy-saving potential of coal-fired cogeneration offered an efficient solution to the issues. The research of [6] presented thermal efficiency of buildings in the UK and offered suggestions for essential architectural adjustments to support fourth and fifth generation district heating systems. Also, they determined that crucial sectors to focus on include developing a proficient staff, establishing pertinent metrics and benchmarks, and offering financial assistance for initial stage design investigation.

In the study of [7], the researchers investigated the correlation between combustion parameters and gaseous pollutant emissions from coal-fired boilers, while ref. [8] discussed the impacts, challenges, and opportunities of decarbonizing the Western Macedonia region in Greece. Also, ref. [9] implemented a district heating system that minimized carbon emissions by utilizing low-temperature water, waste heat, and natural gas for heating, and employed a heat pump and thermal storage for efficient heat and power distribution. The implementation of clean heating systems in Chinese cities holds great potential for reducing energy consumption, reducing emissions, and improving the economic sustainability of district heating systems.

The paper of [10] performed a comprehensive analysis of the scientific literature regarding zero-emission neighborhoods, positive energy districts, and related concepts pertaining to environmentally sustainable communities, while ref. [11] examined the existing heating conditions in China and suggested utilizing a spatial system analysis approach to assess the viability of heating solutions. A qualitative inquiry on the choice of heating solution in various regions of China was conducted using the spatial system analysis method.

The study of [12] found that districts can achieve full energy system decarbonization without biomass by depending exclusively on wind and solar electricity. Utilizing power-to-heat and power-to-gas technologies in a polygeneration solution, together with flexible operation, can achieve full decarbonization. In the recent research of [13], they examined the obstacles of implementing a low-carbon district heating system that relies on reducing biomass incineration and completely eliminating fossil fuels. In the study of [14], the researchers described the implementation and results of simulation models for efficient thermal networks, specifically in a real case study involving a building renovation project in Italy, with a focus on optimizing indoor comfort conditions and minimizing energy consumption and emissions.

In the study of [15], multigeneration high-temperature systems that use fossil fuels, solar heat, and molten salts as heat storage mediums are reviewed, while the study by [16] examines the following two scenarios: individual building heating, and centralized district heating. It evaluates ways to increase renewable energy sources in centralized heat supply, focusing on technical solutions for municipal buildings to assess their effectiveness.

Finally, the article of [17] introduces a novel technology for producing heat without carbon emissions for district heating. This technology involves a fuel cell combined heat and power generation system with carbon dioxide capture, as well as a two-stage cascade high-temperature heat pump.

The gradual weaning of Greece from fossil fuels with the shutdown of all lignite units by 2028 forms the basis of the plan for the transition to a climate-neutral era. At the European level, the European Green Deal [18] and the new National Climate Law [19], which turns the political commitment into a legal obligation, envisage that Europe will be the first climate-neutral continent until 2050.

The Greek government’s Just Development Transition Plan [20] (ESEK Government Gazette B’ 4893/31-12-2019, 2019) emphasizes environmental protection, encourages competitive power generation technologies, and promotes diversification of the production model. The main elements of the Just Development Transition Plan for the region of Western Macedonia, Greece, include the following actions:

- Creation of 2GW Photovoltaic parks;

- Creation of a 200 MW Photovoltaic Park in Kozani, Greece;

- The voluntary retirement of Public Power Corporation (PPC) regular staff in the lignite areas, which is fully self-financed;

- Rehabilitation of the PPC mines;

- Ensuring the district heating operation even after the lignite units’ withdrawal;

- Speeding up the spatial planning process for the development of the lignite areas;

- Yield of lignite resource;

- Financing of lignite areas from Carbon Dioxide (CO2) emission rights auctions;

- Support local solid waste management agencies;

- Highlighting and supporting the developmental role of the University of Western Macedonia;

- Submission to the European Union’s Commission of a request to characterize lignite areas as special tax zones with special tax incentives.

The region of Western Macedonia, Greece, is greatly affected by these developments. Delignification will take place with particular attention to social and economic impacts, employment, and energy security, given that the region has been almost exclusively dependent on lignite for decades.

After the closure of the lignite units, Western Macedonian regions seem to face the threat of unemployment, low health, reduced employment and development opportunities, poverty, non-absorption of the workforce, mine rehabilitation, and the environment. The plan will implement the just transition through particular mechanisms, such as the European and National Just Transition Fund [21].

- The importance of just transition was first used in North America in the early 1990s. Its use was purely to support workers affected by problems with formulating and implementing environmental protection policies.

- In recent years, just transition has been linked to tackling climate change. It is the only way out for businesses and regions affected by climate change measures. The Paris Agreement on Climate Change [22] emphasizes the need to consider the “imperatives of a just transition of the workforce to the new situation and the creation of decent work and high-quality jobs in line with nationally defined development priorities”.

- Similar information can be found in the Communication on the European Green Deal [18], specifying that the Agreement sets forth the objective of converting the European Union into an equitable and prosperous society characterized by a contemporary, competitive, and resource-efficient economy, and achieving complete elimination of greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. The European Commission says that this transformation must be equitable, i.e., “prioritizing people and taking care of the regions, sectors and workers who will face the greatest challenges” [23].

- The European Union prioritizes and promotes the solution of district heating to save energy and heating/cooling costs with a simultaneous reduction in greenhouse gasses and energy dependence on fossil fuels. District heating is an environmentally friendly solution based on European Energy Saving and Energy Efficiency guidelines [24].

- The countries of Central Europe, as well as the Scandinavian countries with a tradition in district heating, have improved the energy and environment further, and at the same time, economic results of these systems through the use of Renewable Energy Sources (RES). The utilization of RES, and mainly the use of biomass and thermal solar systems, which started in the 1990s with the development of the technology, led to thermal energy supply and cooling systems entirely from RES supplying the district heating/district cooling networks.

As a result, local communities reap significant benefits such as increasing residents’ incomes and developing new business activities that lead to new, high-level jobs. Thus, local communities that were in decline were revitalized with the development of industrial activities, while at the same time, the research and education sectors were strengthened. Characteristic examples are the cities of Güssing in Austria, Marstal in Denmark, and the city of Poderwijk in the Netherlands, but also the country of Denmark as a whole [23].

The novelty of this paper is that it provides a thorough examination and a SWOT analysis regarding the expenses and emissions linked to several alternative energy sources that could support the continued operation of district heating in Western Macedonia, Greece, during the upcoming period after lignite.

The remaining five sections of the paper are as follows: a section describing the future of district heating during the meta-lignite period, a section presenting the implementation plan proposal, a section explaining the analysis proposed framework, the section performing the heating costs analysis, the section illustrating the SWOT analysis performed, and finally, the conclusions section.

2. District Heating during the Post-Lignite Period

The future of district heating in Western Macedonia, Greece, is at risk due to the government’s decision to stop lignite electricity production in the context of the European Commission’s decisions to reduce the use of fossil fuels for electricity production drastically. In particular, concerning safeguarding the future of district heating in the broader area of Kozani, the competent bodies are called upon to effectively deal with the problem of continuous operation with the use of alternative fuels, aiming at the same time to preserve jobs and general wellbeing for the benefit of citizen users of the services heating. The importance of district heating, ensuring the continued operation of the Kozani’s system and in the rest of the district heating in Western Macedonia, and the undoubted benefits of their operation in supporting clean energy and a greener and more resilient environment, are an essential part of this study. The aim is to ensure the environmental, economic, and social benefits that the region enjoys to date.

The operation of district heating contributes to the optimal exploitation of primary energy, achieving energy savings, improving the system’s efficiency, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions, especially carbon dioxide. The above constitutes a national goal as described in the Greek National Energy and Climate Plan [20], highlighting the priorities and the development potential of our country in matters of energy and dealing with climate change, but also a goal of the European Union.

In Northern Greece, district heating systems were studied and installed for the heating needs of citizens in three cities of the Region of Western Macedonia (Ptolemaida, Kozani, and Amyntaio). It is noteworthy that almost the entire Greek energy system has been located in this area, both with the lignite mines and with the production units that supply the country with electricity, for more than 60 years, due to the increased performance and the improved exploitation of the region’s domestic fuel (lignite).

District heating systems provide cost-effectiveness for interconnected consumers about alternative sources and technologies of urban indoor heating and domestic hot water production. Severe environmental problems were observed and recorded in the area during the past, with prominent air pollution from lignite mines, power production plants, and city dwellers’ use of oil for heating spaces. Undoubtedly, district heating is a good practice in a sustainable, economically attractive, and environmentally friendly heating model.

Today, in the Region of Western Macedonia, the district heating of Ptolemaida, Kozani, and Amyntaio is operational, supplied by lignite stations of PPC.

Following the country’s decision to cease lignite electricity production, which was taken in the context of the European Commission’s decisions to drastically reduce the use of fossil fuels in the production of electricity, a critical situation is created for the future of the above district heating system, which the competent companies, as well as the respective municipalities, should deal with to ensure the future of district heating, the preservation of jobs, and ultimately the interest of citizens who use these services.

According to the retirement planning of the existing lignite units operating in Western Macedonia, the units supplying thermal energy to the district heating of Kozani, Units III and IV of the Steam Power Station (SPS) of Agios Dimitrios are to be retired by December 2023 and Unit V by December 2025, while, according to the same plan, on August 2020, the withdrawal of Units I and II of Amyntaio SPS will be implemented, and on April 2021, so will the withdrawal of Units III and IV of the Kardia SPS.

Switch to an Alternative Heating Model

The operating regime of the lignite units operating in Western Macedonia necessitates the transition to other modes of operation of district heating. It is worth noting that the continuous upward trend in the annual cost of CO2 emission rights, which started from 4.54 EUR/tCO2 in 2013, reached 25.6 EUR/tCO2 in 2021, and its continuation reaching today 71 EUR/tCO2, puts a terrible burden on the operating costs of the lignite units in the region.

Also, following the Industrial Emissions Directive (2010/75/E.U.) [25] and the stricter limits that were set for other gaseous pollutants (sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, particles, etc.), the withdrawal of the lignite units of Kardia SPS and Amyntaio SPS was a one-way solution since there was no way to comply with the new emission limits. Consequently, the first problems of meeting district heating need in Ptolemaida and the broader region of Amyntaio began to appear. The problems worsened further within the framework of the directive mentioned above regarding the integration of the lignite units of the Ag. Dimitrios in the Greek National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP) and their forced withdrawal if there is no possibility of upgrading until December 2023 (Unit III and IV) and until December 2025 (Unit V).

Based on the above, in combination with technological development, clean energy occupies the first role with undeniable superiority, competing with lignite. Therefore, it is necessary to consider solutions that do not rely on lignite as a fuel to cover the thermal needs in Western Macedonia, Greece. In this context, [23] examines four different technologies of Renewable Energy Sources: (a) the co-production of electricity and heat from biogas, (b) solar thermal with seasonal heat storage and heat pumps, (c) the production of heat from boilers biomass, and (d) the co-production of electricity and heat with the Organic Rankin Cycle (O.R.C.) technology with biomass fuel. According to the NECP [20], some conditions are established that contribute to the protection of the environment and the health of citizens, as follows:

- Reduction in greenhouse gas emissions;

- Improvement of Energy Efficiency by at least 38% until 2030;

- Lignite-free electricity production by 2028.

Under these conditions, the European Union’s new development strategy for a society ruled by law, a modern society with the ultimate goal of zero net greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, will be achieved.

3. The Project Plan Implementation Proposal

This section presents the only solution designed and programmed to ensure the coverage of the needs of all district heating in the region under study, both during the transitional stage and after the withdrawal of the existing lignite units in the region, following the specifications of the NECP [20]. It includes the interconnection of Kozani’s district heating facility with the thermal power distribution and production provisions planned, the location of which is planned to be within the site of the Kardia SPS. With this specific project, the Kozani district heating installation will be functionally connected to the unified district heating system of Amyntaio, Kozani, and Ptolemaida, as foreseen by the signing of the Memorandum above, to ensure the coverage of the district heating needs of Western Macedonia both during the transitional stage and after the withdrawal of the existing lignite units in the area during the implementation of the NECP.

3.1. Description of the Project

In more detail, the interconnection project, according to the data of Kozani’s Municipal Water Supply and Sewerage Company (DEYAK) [26], includes the construction of a system of underground steel, factory-insulated superheated water transfer pipelines from the production facilities and the transfer pumping station within the Kardia SPS field to the central transmission and distribution pumping stations of the Kozani District Heating facility in the Kasla area at the city of Kozani. Based on the existing peak of the Kozani district heating system combined with the thermal demand due to the future expansions of the system in Kozani, the nominal thermal power transmission capacity is projected to reach 195 MWth.

The pipelines will be designed in such a way as to provide the Kozani district heating system with the possibility of supplying thermal energy both from the internal thermal energy production units of Kardia SPS, from the under-construction PPC’s Cogeneration of Electricity and Heat (COH) unit, the layout of the natural gas boilers, as well as from the new Ptolemaida V lignite Unit of PPC SA, which is in the final stage of completion, through the existing interconnection pipeline that connects the Kardia SPS with the Ptolemaida district heating system. The existing district heating infrastructures should be utilized.

Therefore, it is proposed to build a new transmission pipeline, starting with the interconnection facilities at the Kardia SPS, which will be connected to the already existing transmission system of the Kozani district heating system. The connection will occur within the proposed bathhouse, in a North–Northwest position of the Drepano settlement. The new pipeline will be a double pipeline consisting of a supply and a return pipeline, with a trench length of approximately 8.3 km.

In order to be able to receive the nominal transmission power from the Kozani district heating system, it is also planned to install a single transmission pipeline from the connection point in the area of Drepano up to the interconnection facilities in the area of Kasla, with a tunnel length of approximately 7.9 km.

In addition, for the necessary connections of the new pipeline with the existing ones, a new double pipeline will be installed in the area of the Drepanos bathhouse, with an estimated trench length of approximately 1 km. According to the above, the total length of the trench will reach 16.2 km.

More specifically, the transport medium is hot-superheated water, and the transport pipelines will be pre-insulated steel with polyurethane (PUR) insulation and polyethylene (PEH) protective casing, suitable for installation directly on the ground. Underground, there will be installed, along the entire length, an integrated leak detection system and isolation valve devices inside wells with discharge-ventilation valve devices on both sides.

3.2. Feasibility of the Project

The implementation of this project will substantially contribute to maintaining and continuing the operation of the Kozani district heating system in the post-lignite period, especially after the formulation of the revised Greek national energy and climate plan in compliance with the new business plan of PPC S.A., based on which the withdrawal of the existing lignite units operating in Western Macedonia and, in particular, those supplying thermal energy to the district heating of Kozani is foreseen. Ensuring an alternative installation supply with thermal power is imperative so that it is not forced to stop its operation with enormous economic, environmental, and social consequences.

Today, the SPS of Ag. Dimitrios is the only thermal energy source for the Kozani district heating system, providing more than 95% of the system’s thermal energy. However, the recent developments regarding the use of domestic lignite as a fuel for power generation units, combined with the exhaustion of the permitted operating hours of the units in Western Macedonia that supply thermal energy to the district heating systems in the region, are a challenge for district heating companies, which are required to transform their existing business model radically, adapting the operation to the remaining lignite power generation units in the area or even producing all the thermal energy of their systems themselves.

According to the retirement planning of the existing lignite units operating in Western Macedonia, the units supply thermal energy to the district heating of Kozani.

3.3. Impact of the Project

Ensuring the supply of the Kozani district heating installation is planned to be made from new sources of thermal power production, as follows:

- The new COH unit of PPC S.A. with nominal power of 85 MWel/65 MWth located within the Kardia NPP;

- The design and construction of a new arrangement of high-efficiency natural gas boilers with a nominal thermal power of ~140 MWth also located in Kardia, as well as

- The new Ptolemaida V lignite unit, with a nominal thermal output capacity of 140 MWth.

Given the above, the district heating system operation after 2023 is supposed to be ensured. In that case, it will undoubtedly contribute to maintaining the economic and environmental benefit of the region and its citizens and strengthening its business development. In summary, the main benefits are as follows:

- Maintaining and ensuring the sustainability of district heating as a primary heating system for residents;

- Optimal utilization and saving of primary fuel energy;

- Maintenance and increase in thermal energy recovery potential from cogeneration, as well as the possibility of expansion of the district heating networks of Kozani;

- Substitution of the use of oil in the state-of-the-art boilers of DEYAK, and the restoration of their role from reserve boilers to cutting-edge boilers for which they were initially combined with natural gas as fuel;

- The increase in the level of environmental protection due to the performance of cogeneration and the low level of emissions of the new COH unit as well as the new lignite unit, and finally maintaining a competitive heating tariff for urban and extra-urban use contributes to social cohesion and the well-being of residents.

4. The Proposed Analysis Methodology Framework

The analysis carries out critical parameters that change in the context of the transition to the post-lignite period, which is the reduction in primary energy use of fossil fuels, the environmental impact/level of greenhouse gas emissions (CO2), the economic competitiveness in terms of consumers, the economic impact on the local community, as well as the economic benefit due to the reduced cost of CO2 emission rights. The methodology lies in investigating and analyzing these indicators and the change in these indicators. The evaluation is based on the cost–benefit analysis of environmental, economic, and social indicators (Social Cost–Benefit Analysis). In this study, we benchmarked the case that the transition to the post-lignite period was not made with the continued use of district heating, and the alternative scenario of the transition to the post-lignite period and the possible non-use of district heating.

4.1. Heating Costs Analysis

Economic evaluation through cost–benefit analysis in this section is about analyzing economic indicators. It concerns the choice of alternative indoor heating technologies and indicates an average residential area of 100 m2. The alternative heating technologies and possible scenarios selected for examination are the following: (a) heating using oil, (b) heating using natural gas, (c) heating with a high-temperature heat pump (electric energy), and d) the analysis of heating costs using solid fuels (wood and pellets).

4.1.1. Analysis of Heating Costs Using Oil

This section examines the option of heating the interior of a house with an average area of 110 m2 using oil. The cost–benefit components, which are taken into account during the analysis, are the following [27]:

- The unit price of thermal energy;

- Primary fuel energy required;

- The annual heating cost.

It is worth noting that results using the following equations are illustrated in bold fonts in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4, while the rest of the input data are taken from [26].

Table 1.

Analysis of heating costs using oil.

The discount of this scenario to district heating is 66.51%, and it is related to the price of district heating given by this Equation:

District heating discount = 1 − (District heating unit price + Value Added Tax (VAT)/Special cost per unit) (%)

4.1.2. Analysis of Heating Costs Using Natural Gas

This section considers the option of heating the interior of a house with an average area of 110 m2 using natural gas. The cost–benefit components which are considered are as follows [28]:

- The thermal energy unit price;

- Required thermal energy for space heating;

- The annual cost of heating with natural gas.

Table 2.

Analysis of heating cost using natural gas.

Table 2.

Analysis of heating cost using natural gas.

| Average residential area | Ε | 110 | m2 |

| Specific consumption of thermal energy | e | 130 | kWh/m2 year |

| Required thermal energy for space heating | Hout | 14,300.00 | kWh |

| Efficiency rating of a conventional natural gas boiler | n% | 90.00% | % |

| Primary fuel energy required | Hin | 15,888.89 | kWh |

| COMPETITIVE CHARGES | |||

| NATURAL GAS supply charge unit price | Πc | 0.13000 | EUR/kWh |

| % discount provided | disc | 0.00% | |

| NATURAL GAS supply charge | Π | EUR 2272.11 | |

| Monthly fee | Am | EUR 5.50 | EUR/month |

| Annual fixed charge | Ay | EUR 66.00 | |

| Partial Total COMPETITIVE Charges | Ax | EUR 2338.11 | |

| REGULATED CHARGES | |||

| Distribution network capacity charge unit (2021) | ΜΧΔ(ΔΔ) | 0.688756561 | EUR/kW/year |

| Distribution network capacity charge (2021) | XΔ | EUR 13.78 | (for 20 kW) |

| Distribution network energy billing unit (2021) | ΜΧΕ(ΔΔ) | 0.017563852 | EUR/kWh |

| Distribution network energy fee (2021) | ΧΕ | EUR 279.07 | EUR |

| Transmission network energy charging unit (2021) | ΜΧΕ(ΔΜ) | 0.00215 | EUR/kWh |

| Transmission network energy fee (2021) | ΧΕ(Μ) | 34.16 EUR | |

| Partial total of adjustable charges | ΡΧ | 327.01 EUR | |

| Other charges | |||

| Charge of special consumption tax on NATURAL GAS | ΧΕΦΚ | 0.00108 EUR | |

| Special consumption tax on NATURAL GAS | ΕΦΚ | 17.16 EUR | |

| Special Fee DETE 0.5% | ΔΕΤΕ | 13.41 EUR | |

| TOTAL NET WORTH EUR | 2695.69 EUR | ||

| VAT 6% | VAT | 160.94 EUR | |

| Total annual cost of heating with natural gas | C | 2856.63 EUR | EUR |

| Specific cost of thermal energy unit | Cs | 199.76 EUR | EUR/MWh |

| Discount in relation to district heating | = | 74.61% |

Where Hout = E × e, Hin = Hout × n%, Π = [(ΠC × Hin) × (1-disc)] ×1.1, Ay = (Am × 12), Ax = (Ay + Π), XΔ = ΜΧΔ (ΔΔ) × 20, ΧΕ= ΜΧΕ (ΔΔ) × Hin, XΕ (Μ) = ΜΧΕ (ΔΜ) × Hin, ΡΧ = (XΔ + ΧΕ + XΕ (Μ)), ΕΦΚ = ΧΕΦΚ × Hin, ΔΕΤΕ = (ΕΦΚ + ΡΧ + AX ) × 0.5%, C = ΔΕΤΕ + ΕΦΚ + ΡΧ + AX, Cs = (C/Hout) × 1000.

As shown in Table 2, the discount to district heating is 74.61%.

4.1.3. High Temperature Heat Pump Heating Cost Analysis (Electricity)

This section considers the option of heating the interior of a house with an average area of 110 m2 using a high-temperature heat pump. The cost–benefit components are [28]:

- The thermal energy unit price;

- The final cost of heating;

- Required energy consumption;

- Special cost of thermal energy.

Table 3.

High-temperature heat pump heating.

Table 3.

High-temperature heat pump heating.

| Typical house building 110 m2—medium quality of thermal insulation | Ε | 110 | m2 |

| Specific consumption of thermal energy | e | 130 | kWhTh/m2 year |

| Required energy consumption (kWh/heating period), | Hout | 14,300.00 | kWhTh |

| Coefficient of performance (COP) of a high-temperature heat pump | COP | 2.8 | |

| Required low voltage electricity | Hin | 5107.14 | kWhel |

| Electricity charge unit price | Xe | 0.11936 | EUR (>2000 kWhel) |

| Electricity supply charge surcharge clause | Ρ | 0.34 | EUR/kWhel |

| Heating period electricity supply cost-net value | Π | 2346.02 | EUR |

| Special cost of electricity transmission system | CEΜ | 0.0056 | EUR |

| Cost of electricity transmission system | Δμ | 28.60 | EUR |

| Special cost of electricity distribution system | CΕΔ | 0.0213 | EUR |

| Cost of electricity distribution system | Δδ | 108.7821 | EUR |

| Other charge EUR special cost | Xλ | 0.00007 | EUR |

| Expenditure of other charges | Δλ | EUR 0.35750 | |

| Special Cost ΕΤΜΕAΡ | CΕΤΜΕAΡ | EUR 0.017 | |

| Expenditure ΕΜΕAΡ | ΔΕΜΕAΡ | EUR 86.821 | |

| Special ΥΚΩ cost | CΥΚΩ | 0.0850 | |

| ΥΚΩ expenditure | ΔΥΚΩ | EUR 434.11 | |

| Estimated cost of fixed assets | Δπ | EUR 50 | |

| Net value of total electricity expenditure | Ce | 3054.69 | EUR |

| 6% VAT cost borne by the consumer | VAT | 183.28 | EUR |

| Final cost of heating with a heat pump | CH | 3237.97 | EUR |

| Electricity supplier discount rate | 10.00 | % | |

| Final consumer cost | C | 2914.17 | EUR |

| Special cost of thermal energy | Cs | EUR 203.79 | |

| Discount in relation to district heating | = | 75.11% |

Where Hout = E × e, Hin = Hout/COP, Π = [(Xe + Ρ) × Hin], Δμ = CEΜ × Hin, Δδ = CEΔ × Hin, Δλ = Χλ × Hin, Ce = Π + Δμ + Δδ + Δλ + ΔΕΜΕAΠ + ΔΥΚΩ + Δπ, CH = Ce × 6%, Cs = (C/Hout) × 1000.

As a conclusion from Table 3, the discount to district heating is 75.11%, which is related to the price of district heating.

4.1.4. Analysis of Heating Costs Using Solid Fuels (Wood and Pellets)

In this section, two options for heating the interior of a house with an average area of 110 m2 are examined using a wood boiler and pellets. The cost–benefit components, which are taken into account during the analysis, are the following [27]:

- The thermal energy unit price;

- Required thermal energy for space heating;

- The annual cost of heating with a wood boiler and pellets, respectively.

Table 4.

Analysis of heating costs using firewood in wood boilers.

Table 4.

Analysis of heating costs using firewood in wood boilers.

| Type of Wood. | Beech | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture percentage on liquid M % | % | 30.00% | |

| Lower calorific value on liquid | Hu | 12.15 | MJ/kg |

| Lower calorific value on liquid | Hu | 3.37 | kWh/kg |

| Product purchase price | p | EUR 120.00 | EUR/χ.κ.μ. stacked up |

| Weight per kgm of stacked beech firewood | w | 453.00 | kg/χ.κ.μ. stacked up |

| Combustion device | Wood boiler | ||

| Average efficiency % | n | 70.00% | |

| Average residential area | Ε | 110 | m2 |

| Specific consumption of thermal energy | e | 130 | kWh/m2 year |

| Required thermal energy for space heating | Hout | 14,300.00 | kWh |

| Primary fuel energy required | Hin | 20,428.57 | kWh |

| Required amount of wood in kilograms | m | 6053.91 | kg |

| Required volume of wood in m3 | V | 13.36 | m3 |

| Fuel supply cost EUR | CΠ | EUR 1603.68 | EUR |

| Annual maintenance cost boiler | Cm | 5.00% | |

| Final annual heating expense | C | EUR 1683.87 | EUR |

| Special energy cost | SEC | EUR 117.75 | EUR/MWhTh |

| Discount in relation to district heating % | = | 56.93% |

Where Hout = E × e, Hin = Hout/n%, m = Hin/Hu, V = m/w, CΠ = V × p, C = CΠ × (1 + Cm), SEC = (C/Hout) × 1000.

As described in Table 4 and Table 5, the discount to district heating is 56.93% using a wood boiler and 52.20% using pellets.

Table 5.

Analysis of heating cost using wood pellets.

Substituting district heating with any other heating method, as examined during the economic analysis carried out and reflected in the above Tables, is considered unprofitable. Therefore, it is necessary to use district heating and to continue its operation during the post-lignite period. The significant reduction in operating costs brought about by district heating leads to the saving of financial resources by consumers, thus strengthening the local community and maintaining jobs while simultaneously developing the market. In addition, it is worth noting that saving resources is also important at the national level, given that oil is an imported fuel. The summary comparison Table (Table 6) of alternative heating methods is presented below [27]:

Table 6.

Comparison of alternative heating methods.

It is also interesting that even with any change in the values of the indicators of all alternative energy sources, whether oil itself, electricity, solid fuels, or even natural gas, the use of district heating was found to remain more advantageous.

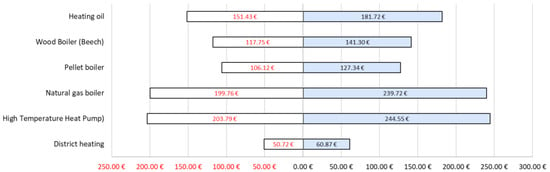

For the analysis of the change in the average cost per unit price of thermal energy, the tornado graph was constructed [29]. The configuration of this diagram is determined by the change caused by the main factor that determines the economic viability of substituting the use of district heating compared to any other heating method, namely the average unit price cost of the thermal energy when this parameter changes to +20%. In this way, the fact is confirmed that even with any change in the values of the indicators of all alternative energy sources, the use of district heating is judged to remain more advantageous. Figure 1 includes a diagram of the percentage change in the average unit price cost of thermal energy of alternative heating methods.

Figure 1.

The change in average cost of thermal energy unit price.

4.2. CO2 Emissions and Other Pollutants Analysis

This section’s environmental analysis, through cost–benefit analysis, is about the analysis of environmental indicators. It concerns the emissions of greenhouse gas pollutants, mainly carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, as well as the polluting emissions of sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen oxides (NOx), and suspended particles (PM2.5), depending on the type of alternatives selected of indoor heating technologies.

The alternative heating technologies and possible scenarios selected for consideration are (a) emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other pollutant emissions using heating oil, (b) emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) using a high-efficiency heat pump temperatures (electricity), and (c) the emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) as well as other polluting emissions using firewood (solid fuels) for heating [30].

As it is analyzed in [30], to quantify the environmental benefit, and particularly the reduction in CO2 emissions, it is initially estimated that 80% of the serviced surface uses oil for heating, 15% uses a high-temperature heat pump, and 5% of the serviced surface uses solid fuel pellets. Next, the overall carbon dioxide emissions of the specific heating mix will be compared with the CO2 emissions of district heating use [30].

4.2.1. Emissions of Carbon Dioxide (CO2) and Other Pollutant Emissions Using Heating Oil

This section examines the CO2 emissions of 80% of the serviced area that uses oil for heating (Table 7). Determining the environmental benefit requires estimating the amount of heating oil consumed based on the current situation by consumers.

This quantity is a function of (a) the estimated thermal energy that should be provided for heating the interior spaces of the buildings, (b) the average estimated degree of efficiency of the oil boilers currently used by consumers to serve their needs, and finally, (c) from the characteristic elements of the fuel and, in particular, the average density and lower calorific value of the heating oil. The cost–benefit components, which are taken into account during the analysis, are the following [27]:

- The required thermal energy for space heating;

- The required primary fuel energy;

- Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions;

- Emissions of sulfur oxides (Sox);

- Emissions of Nitrogen oxides (Nox);

- The emissions of suspended particles (PM2.5).

Table 7.

Emissions of gaseous pollutants for heating using oil [30].

Table 7.

Emissions of gaseous pollutants for heating using oil [30].

| Number of buildings that use heating oil | 4551 | ||||

| Average density of heating oil | ρ | 0.836 | kg/lt | ||

| Lower calorific value | Hu | 42.800 | kJ/kg | 11.890 | kWh/kg |

| Average efficiency of domestic boilers | % | 87.00% | % | ||

| Heating Oil Oxidation Coefficient | OF | 1 | |||

| Total surface | Εsum | 2800.000 | m2 | ||

| Heated surface using heating oil (80% of all houses) | Ε | 2240.000 | m2 | ||

| Specific consumption of thermal energy | e | 130.00 | kWh/m2 year | ||

| Required thermal energy for space heating | Hout | 291,200.00 | MWhTh | ||

| Primary fuel energy required | Hin | 334,712.64 | MWhTh | ||

| Primary fuel energy required | Hin | 1204.97 | TJ | ||

| Specific coefficient of Carbon Dioxide emissions | SC_CO2 | 73.78 | tCO2/TJ | ||

| Specific coefficient of Sulfur oxides emissions | SC_SOx | 0.495 | tSOx/TJ | ||

| Specific coefficient of Nitrogen oxides emissions | SC_NOx | 0.142 | tNOx/TJ | ||

| Specific coefficient of suspended particle emissions | SC_PM2.5 | 0.0193 | tPM2.5/TJ | ||

| Total CO2 emissions | CO2 | 88,902.36 | tCO2 | ||

| Total emissions of sulfur oxides SOx | Sox | 596.46 | tSOx | ||

| Total emissions of nitrogen oxidesNOx | NOx | 171.11 | tNOx | ||

| Total emissions of suspended particles PM2.5 | PM2.5 | 23.26 | tPM2.5 | ||

4.2.2. Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Emissions Using High Temperature Heat Pump (Electricity)

This section examines the CO2 emissions of 15% of the serviced area that uses electricity for heating (Table 8). Determining the environmental benefit requires estimating the amount of electricity consumed based on the current situation by the consumers. The cost–benefit components, which are considered during the analysis, are the following:

- The required energy consumption for space heating;

- The required low-voltage electricity;

- The proportional energy with the respective participation percentage of the energy mix;

- Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions.

Table 8.

Emissions of gaseous pollutants for heating using a heat pump [30].

Table 8.

Emissions of gaseous pollutants for heating using a heat pump [30].

| Number of Buildings Using Heat Pumps | 853.00 | |||||

| Heated surface using a heat pump (15% of all houses) | Ε | 420,000.00 | m2 | |||

| Specific consumption of thermal energy | e | 130.00 | kWhTh/m2 year | |||

| Required energy consumption | Hout | 54,600,000.00 | kWh/heating period | |||

| High temperature pump Coefficient of Perfonce (COP) | 2.80 | |||||

| Low voltage electricity required | Hin | 19,500,000.00 | kWh | |||

| Energy Origin | Turnout | Proportional Energy (kWhel) | Proportional Energy (TJ) | Specific coefficient of Carbon Dioxide Emissions (tCO2/TJ) | Total carbon dioxide emissions (tCO2) | |

| Lignitic | 10.40% | 2,028,000.00 | 0.5633 | 116,997 | 65.90831 | |

| Natural gas | 32.10% | 6,259,500.00 | 1.7388 | 59.44 | 103.3513 | |

| Hydroelectric | 14.00% | 2,730,000.00 | 0.7583 | 0 | 0 | |

| Renewable | 31.50% | 6,142,500.00 | 1.7063 | 0 | 0 | |

| Connections | 12.00% | 2,340,000.00 | 0.6500 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total: | 169.25961 | |||||

4.2.3. Emissions of Carbon Dioxide (CO2) and Other Pollutant Emissions Using Solid Fuel-Pellets

This section examines the CO2 emissions of 5% of the served area that use solid fuel pellets for heating (Table 9). Determining the environmental benefit requires initially assessing the primary energy provided by fuel pellets. This quantity is a function of (a) the energy of consumers using pellets, (b) the estimated energy of consumers for heating the space using solid fuels and, more specifically, pellets, and (c) the average estimated degree of efficiency of pellet boilers currently used by consumers to serve their needs. The cost–benefit components, which are taken into account during the analysis, are the following [31]:

- The provided primary energy fuel pellets;

- Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions;

- Emissions of nitrogen dioxide (N2O);

- Methane emissions (CH4);

- Emissions of sulfur oxides (Sox);

- Emissions of Nitrogen oxides (NOx);

- The emissions of suspended particles (PM2.5).

Table 9.

Emissions of gaseous pollutants for heating using solid fuel-pellets [30].

Table 9.

Emissions of gaseous pollutants for heating using solid fuel-pellets [30].

| Number of buildings using PELLETS | 284 | |

| Heated surface using PELLETS (m2) (5% of all houses) | 14,000.00 | m2 |

| Billed thermal energy of district heating consumers | 240,000.00 | MWhTh |

| Consumer energy using pellets, Hout | 12,000.00 | MWhTh |

| Average efficiency of pellet boilers, n | 80.00% | |

| Granted Primary energy of pellet fuel, Hin | 15,000.00 | MWhTh |

| Granted Primary energy of pellet fuel, Hin | 54.00 | TJ |

| Specific coefficient of Carbon Dioxide emissions CO2 | 4.166666667 | tCO2/TJ |

| Specific emission factor of Nitrous Oxide N2O | 0.0050 | tΝ2O/TJ |

| Specific coefficient of CH4 Methane emissions | 0.0100 | tCH4/TJ |

| Specific coefficient of emissions of oxides of Nitrogen NOx | 0.0600 | tΝOx/TJ |

| Specific emission factor of solid PM10 (unburned/ash) | 0.0150 | tPM10 eq/TJ |

| Total CO2 emissions | 225.00 | tCO2 |

| Total N2O emissions | 0.27 | tN2O |

| Total CH4 emissions | 0.54 | tCH4 |

| Total NOx emissions | 3.24 | tNOx |

| Total PM10 emissions | 0.81 | tPM10 |

4.2.4. Emissions of Carbon Dioxide (CO2) and Other Pollutant Emissions Using District Heating

This section examines the CO2 emissions of 100% of the serviced area that use district heating for heating (Table 10). Determining the environmental benefit requires estimating the amount of heating oil consumed based on the current situation by consumers. This quantity is a function of (a) the estimated thermal energy that should be provided for heating the interior spaces of the buildings, (b) the average estimated degree of efficiency of the oil boilers currently used by consumers to serve their needs, and finally, (c) from the characteristic elements of the fuel and, in particular, the average density and lower calorific value of the heating oil. The cost–benefit components, which are taken into account during the analysis, are the following [26]:

- The total thermal energy supplied to the system;

- Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions;

- Emissions of sulfur oxides (SOx);

- Emissions of Nitrogen oxides (NOx);

- The emissions of suspended particles (PM2.5).

Table 10.

Emissions of gaseous pollutants for heating using district heating [30].

Table 10.

Emissions of gaseous pollutants for heating using district heating [30].

| Number of interconnected buildings in the Kozani District | 5689 | |

| Area served (m2) | 2,800,000 | |

| Billed Thermal energy of District Heating consumers | 240,000.00 | MWhTh |

| Average total thermal degree of District Heating installation | 75.00% | |

| Total Thermal Energy Delivered to the system | 320,000.00 | MWhTh |

| Installed oil boiler energy | 16,000.00 | |

| MWh to TJ Conversion Factor | 0.00360 | |

| Fuel details | ||

| Lower Heating Value of Petroleum (LHV) | 42.80 | TJ/KT |

| Average Density of Heating Oil (ρ) | 0.837 | kg/l |

| Heating Oil Oxidation Factor (OF) | 1 | |

| Average efficiency of domestic boilers % | 87.00% | |

| Average purchase price of heating oil for domestic consumers (net value) | EUR 1.306 | EUR/lt |

| Specific coefficient of Carbon Dioxide Emissions (CO2) EF04 | 73.78 | tCO2/TJ |

| Specific coefficient of Sulfur Oxides Emissions (SOx) EF09 | 0.495 | tSOx/TJ |

| Specific coefficient of Emissions of Nitrogen Oxides (NOx) EF01 | 0.142 | tNOx/TJ |

| Specific coefficient of Emission of suspended particles PM2.5 EF10 | 0.0193 | tPM2.5/TJ |

| Peak boiler room heating oil emissions | ||

| Total CO2 emissions | 84,994.56 | t CO2 |

| Total emissions of sulfur oxides SOx | 570.24 | tSOx |

| Total emissions of Nitrogen oxidesNOx | 163.584 | tNOx |

| Total emissions of suspended particles PM2.5 | 22.2336 | tPM2.5 |

| PPC lignite emissions | ||

| Coefficient of carbon dioxide CO2 | 0.24 | t CO2/MWth |

| Total CO2 emissions | 207.36 | t CO2 |

In the context of the environmental analysis, the measurement of environmental air pollutants on an annual basis in the Kozani area was included. As an environmental indicator, the objective of the analysis is the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and CO2. Based on the above, the substantial contribution of district heating to an improved quality of the atmosphere with a reduction in the emissions of the main gaseous pollutants by 4.58% is demonstrated. There is a significant environmental benefit to the use of district heating.

The main environmental benefit is primarily due to the continuation of district heating and the utilization of this technology to cover the energy needs. More specifically, limiting mainly the consumption of heating oil and lignite will have the expected result of a significant reduction in emissions of greenhouse gas pollutants with a principal reduction in CO2 emissions as well as the other equally important polluting gasses.

The expected environmental benefit, as obtained based on the results presented in Table 11 and the summary diagram, is as follows:

Table 11.

Total environmental emissions of gaseous pollutants [30].

4.3. SWOT Analysis

With the SWOT analysis, we identify and capture the strengths and weaknesses of the transition to the post-lignite period and the opportunities and threats that appear during the transition. The strong points define the advantages of the transition in terms of its benefits to the environment, the reduction in the carbon footprint and the transition to a completely different, non-polluting environment, while correspondingly, the vulnerabilities are revealed, that is, those that give a negative image within the development of the local society, at an economic and work level. Opportunities for this transition are the reduction in primary energy use of fossil fuels and the economic benefit due to the reduced cost of CO2 emission rights. However, some developments do not lead to any advantage, but to the creation of a form of threats, such as the loss of specialized personnel from the region, reduced employment opportunities, and the use of alternative sources of heating methods other than district heating, which increases the cost of living of its people in the specific areas [32]. This analysis is presented in the following Table 12:

Table 12.

SWOT analysis Table.

5. Discussion

The operation of district heating in the post-lignite period is crucial for a greener and more resilient Europe. As shown in this paper, the benefits of district heating compared to other energy sources are significant and have considerable economic, social, and environmental implications. The Kozani district heating facility, established in 1993, has been pioneering in the field, and now serves 5689 buildings and an interconnected surface area exceeding 2,800,000 m2.

This heating installation is environmentally friendly, a significant advantage for a region like Kozani, which is heavily impacted by existing mining activities and electricity generation. The operation of district heating contributes to environmental protection through reduced greenhouse gas emissions, providing an expected annual environmental benefit of 18,515.87 tCO2 from replacing oil boilers.

The pricing policy for district heating is highly competitive against alternative indoor heating technologies, leading to high rates of attracting new consumers. Even with changes in the values of indicators of all alternative energy sources, district heating remains more advantageous.

The implementation of projects like these can also stimulate new professional activities and jobs, offering significant social, environmental, and secondary economic benefits. The interconnection project of Kozani’s district heating facility is a model at the European level, and is crucial for the transition to cleaner energy forms across Western Macedonia.

6. Conclusions

To conclude, district heating in Western Macedonia played a vital role in the transition after the lignite period, providing many benefits, both environmentally and economically, and becoming an exemplar at the European level. The project reflects the gradual substitution of W Macedonia lignite power plants, promoting the decarbonization of the Greek energy mix towards the target of a green and self-sufficient EU. The project underscores the gradual replacement of Western Macedonia’s lignite power plants, aiming to decarbonize the country’s energy mix.

According to the present work, the benefit of the operation of district heating compared to other energy sources is indisputable and of significant importance both for the economy and for the social and environmental benefits enjoyed by the region. A significant advantage is the fact that the operation of the Kozani district heating facility contributes significantly to the protection of the environment, mainly due to the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by substituting heating oil or other conventional fuels for interconnected consumers. In addition, from the implementation of systems such as those proposed, new professional activities and jobs can be developed, with significant social, environmental, and secondary economic benefits.

The promising results of the present analysis suggest that it could be further enhanced with a sensitivity analysis of the risk manager’s assessments of other sets of risks. This could lead to a refined framework that is better tailored to the specific circumstances under investigation. The potential for operating existing pipelines using hydrogen also opens new perspectives for the continuation and further development of district heating. As such, district heating remains a promising, sustainable solution for meeting future energy needs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.K.K., O.E.D., A.T. and D.E.K.; Data curation, G.K.K., O.E.D. and A.T.; Formal analysis, G.K.K., O.E.D., A.T. and D.E.K.; Investigation, G.K.K. and A.T.; Methodology, G.K.K., O.E.D., A.T. and D.E.K.; Software, G.K.K., O.E.D. and A.T.; Supervision, G.K.K. and D.E.K.; Validation, G.K.K., O.E.D., A.T. and D.E.K.; Visualization, G.K.K., O.E.D. and A.T.; Writing—original draft, G.K.K., O.E.D. and A.T.; Writing—review and editing, G.K.K., O.E.D. and D.E.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Harrestrup, M.; Svendsen, S. Heat planning for fossil-fuel-free district heating areas with extensive end-use heat savings: A case study of the Copenhagen district heating area in Denmark. Energy Policy 2014, 68, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebi, B.; Mirzaei, P.A.; Bastani, A.; Haghighat, F. A Review of District Heating Systems: Modeling and Optimization. Front. Built Environ. 2016, 2, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizana, J.; Ortiz, C.; Soltero, V.M.; Chacartegui, R. District heating systems based on low-carbon energy technologies in Mediterranean areas. Energy 2017, 120, 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinakis, V.; Flamos, A.; Stamtsis, G.; Georgizas, I.; Maniatis, Y.; Doukas, H. The Efforts towards and Challenges of Greece’s Post-Lignite Era: The Case of Megalopolis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, W. Study on a novel district heating system combining clean coal-fired cogeneration with gas peak shaving. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 203, 112076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, M.-A.; Elrick, B.; Jones, G.; Yu, Z.; Burnside, N.M. Roadblocks to Low Temperature District Heating. Energies 2020, 13, 5893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwierzchowski, R.; Różycka-Wrońska, E. Operational determinants of gaseous air pollutants emissions from coal-fired district heating sources. Arch. Environ. Prot. 2021, 47, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziouzios, D.; Karlopoulos, E.; Fragkos, P.; Vrontisi, Z. Challenges and Opportunities of Coal Phase-Out in Western Macedonia. Climate 2021, 9, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Y. Low carbon district heating in China in 2025—A district heating mode with low grade waste heat as heat source. Energy 2021, 230, 120765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brozovsky, J.; Gustavsen, A.; Gaitani, N. Zero emission neighbourhoods and positive energy districts—A state-of-the-art review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 72, 103013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Urban, F. Carbon Neutral China by 2060: The Role of Clean Heating Systems. Energies 2021, 14, 7461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, R.; Saastamoinen, H.; Ikäheimo, J.; Abdurafikov, R.; Sihvonen, T.; Shemeikka, J. Decarbonised District Heat, Electricity and Synthetic Renewable Gas in Wind- and Solar-Based District Energy Systems. J. Sustain. Dev. Energy Water Environ. Syst. 2021, 9, 1080340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reda, F.; Ruggiero, S.; Auvinen, K.; Temmes, A. Towards low-carbon district heating: Investigating the socio-technical challenges of the urban energy transition. Smart Energy 2021, 4, 100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, M.; Sdringola, P.; Tamburrino, S.; Puglisi, G.; Donato, E.D.; Ancona, M.A.; Melino, F. Efficient District Heating in a Decarbonisation Perspective: A Case Study in Italy. Energies 2022, 15, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbari, H.R.; Mandø, M.; Arabkoohsar, A. A review study of various High-Temperature thermodynamic cycles for multigeneration applications. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 57, 103286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balode, L.; Zlaugotne, B.; Gravelsins, A.; Svedovs, O.; Pakere, I.; Kirsanovs, V.; Blumberga, D. Carbon Neutrality in Municipalities: Balancing Individual and District Heating Renewable Energy Solutions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, S.; Rola, K.; Urbancl, D.; Goričanec, D. Carbon-Free Heat Production for High-Temperature Heating Systems. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication on the European Green Deal; European Commision: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1588580774040&uri=CELEX%3A52019DC0640 (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Greek Goverment’s Gazzete FEK 105/27-5-22. National Climate Law—Transition to Climate Neutrality and Adaptation to Climate Change, Emergency Provisions to Address the Energy Crisis and Protect the Environment. 2022. Available online: https://www.elinyae.gr/ethniki-nomothesia/n-49362022-fek-105a-2752022 (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- ESEK Government Gazette B’ 4893/31-12-2019. National Energy and Climate Plan. 2019. Available online: https://www.elinyae.gr/sites/default/files/2020-02/4893b_2019.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Greek Ministry of Environment and Energy. Greece: Just Transition Development Plan of Lignite Areas; Greek Ministry of Environment and Energy: Athens, Greece, 2020.

- Erickson, L.; Brase, G. Paris Agreement on Climate Change. In Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Improving Air Quality; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; pp. 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markogiannakis, G. Alternatives to the District Heating Systems of W. Macedonia—The case of Ptolemaida. 2016. Available online: https://regionsbeyondcoal.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/DISTRICT_HEATING_EN.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- European Commision. Directive (EU) 2018/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Directive 2010/75/EU on Industrial Emissions (Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control); European Commision: Brussels, Belgium, 2010; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32010L0075 (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- DEYAK. 2021. Available online: www.deyakozanis.gr (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Greek Ministry of Environment and Energy. National Inventory Report of Greece for Greenhouse and Other Gases for the Years 1990–2019; Greek Ministry of Environment and Energy: Athens, Greece, 2021. Available online: https://ypen.gov.gr/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/2021_NIR_Greece.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Energy Exchange Group. 2020. Available online: www.enexgroup.gr (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Arabosis, K.; Karberis, A.; Sotirchos, A. Technical-Economic Evaluation of Investments; Law Library: Athens, Greece, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tripodi, A. Action Plan for the District Heating of Western Macedonia in the Post-Lignite Period. Master’s Thesis, Hellenic Open University, Patra, Greece, 2022. Available online: https://apothesis.eap.gr/archive/item/170494 (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- Forest Research. Carbon Emissions of Different Fuels. 2022. Available online: https://www.forestresearch.gov.uk/tools-and-resources/fthr/biomass-energy-resources/reference-biomass/facts-figures/carbon-emissions-of-different-fuels/ (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- World Wide Fund for Nature. Transition and Employment in Greece. 2021. Available online: https://wwfeu.awsassets.panda.org/downloads/report_just_transition_jobs_in_greece.pdf (accessed on 4 July 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).