Abstract

One of the key issues in sustainable tourism research is the gap between tourists’ expressed friendly attitudes towards sustainable behaviors and their actual behaviors. Although many “low-carbon” themed restaurants have emerged during the low-carbon transformation of the Chinese tourism industry, low-carbon food services have not been significantly improved. This study takes food as the entry point to explore tourists’ behavior and attitudes towards low-carbon tourism in relation to food. We conducted two interviews. The first interview was a semi-structured contextual interview with 120 tourists who had experiences in food streets, aiming to identify the core user group: low-carbon attitude-friendly tourists with high-carbon food behaviors. The second interviews was an in-depth interview based on grounded theory with 29 core users, analyzing the four main reasons for their high-carbon food behaviors and their requirements for low-carbon food services in tourism. Based on this, we extracted four design elements for low-carbon tourism food services: low-carbon information show service, low-carbon service product attractiveness improvement, low-carbon food environment atmosphere creation, and service providers’ low-carbon behaviors. Through these four service elements, we constructed a low-carbon tourism food service design framework based on the core users’ needs, discussed the mechanism of service elements, and provided service design suggestions accordingly. The research results can be helpful for tourism providers, low-carbon tourism researchers, and designers.

1. Introduction

Global climate change characterized by global warming is a significant environmental challenge facing humanity today, and research indicates that carbon emissions from the tourism industry are a significant factor in causing climate change [1]. China’s carbon emissions and environmental pollution are very serious. In 2009, the State Council of China released Document 41, which defined tourism as a pillar industry of the national economy and highlighted the necessity for tourism to prioritize energy saving and emission reduction [2]. After Brown and Belisle examined the influence of food on tourism, food gradually became the focal point of tourism study [3,4,5,6]. Studies show that tourists allocate one-third of their total expenses to food consumption during their travels [7,8]. More tourists visit cities than natural sightseeing in China, which means that the low-carbon transformation of city tourism will have a greater impact on the overall low-carbon transformation of the Chinese tourism industry [9,10,11]. Many tourist cities in China have seen the emergence of numerous restaurants with “green” and “low-carbon” as their promotional content, after the low-carbon transformation of the tourism industry began [12,13]. Restaurants play a significant role in the food system of city tourism [14]. In the past, China’s tourism catering industry primarily focused on developing restaurants’ low-carbon energy consumption, procurement, and transportation, with little consideration given to customers’ attitudes and demands towards low-carbon services, including specific services they need [15]. Although experts have started to recognize the impact of tourists’ low-carbon willingness on the tourism industry, research on tourists’ attitudes and demands towards low-carbon food services remains limited [16]. Therefore, it is important to pay attention to the low-carbon service of tourism food. More emphasis is placed on the user in service design. The design of low-carbon tourism must take into account the perspectives of tourists. Developing more comprehensive low-carbon-tourism indicators requires a focus on design elements from the standpoint of travelers [17]. Therefore, it is necessary for us to understand the actual food behavior and attitude towards low-carbon tourism of tourists who have experienced dine-in in city during their travels. We will explore the reasons behind high-carbon food behavior and uncover the demand for low-carbon food services among tourists.

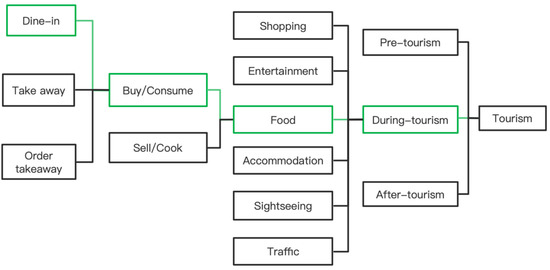

The tourism experience process is divided into pre-tourism, during tourism, and post-tourism [18]. Service implies the interaction between the provider and the served recipient, and food service is the interaction between the food service provider and the consumer [19,20]. In this study, tourism food experience refers to the behaviors of tourists related to food during their travels. Our study focuses on the food experience in tourism, with a specific target group of tourists who have had dine-in experiences during their city travels. The aim of this research is to identify the demand of tourists for low-carbon food services in tourism, construct a low-carbon tourism food service design framework, and to provide theoretical references and design recommendations for such services. Figure 1 show the research focus of this study.

Figure 1.

Research Focus.

We conducted semi-structured situational interviews based on grounded theory, and the research questions were: What are the causes of high-carbon food actions in core users? What are the core users’ requirements for low-carbon services for tourism food?

To address the research question, we conducted two interviews. The first interview aimed to identify the core users by exploring their attitudes and behaviors. The second interview aimed to investigate the demand of these core users for low-carbon food services in tourism based on their high-carbon behavior motivation. As a result, we established a low-carbon tourism food service design framework. Our contribution is to provide food low carbon service design suggestions and theoretical support for Chinese tourism cities and famous food tourism destinations, especially areas dominated by large food districts. Ultimately, the research results may help to promote the development of low carbon services in China’s tourism industry.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Low-Carbon Tourism Food Service

Low-carbon tourism is an approach to tourism development that is directed by sustainable tourism and focuses on low-carbon technologies and consumption [21,22]. Low-carbon consumption also includes the tourist food consumption, food consumed by tourists during tourism is referred to as “tourism food” [23]. In food service, it is divided into hard and soft systems, with physical products and products collectively referred to as hard systems and human activities collectively referred to as soft systems [24]. Tourists will experience the food service through six tasks: Search, order, wait, eating, pay, and after meal [25,26]. In this study, low-carbon tourism food service refers to the low-carbon service enjoyed by tourists during their tourism food experience.

Local food is considered by some scholars as a potential means to shape the destination image and promote sustainable tourism [27,28,29]. However, achieving sustainability in food service requires consideration of various aspects. For instance, the production process of food needs to take into account low-carbon procurement, preparation, and presentation [30]. Moreover, the carbon footprint of food products, particularly meat, has been studied extensively [31,32]. In addition to food, the quality of restaurant services plays a crucial role in promoting sustainability. Quantitative analyses have shown that combining intelligent and humanized services can enhance the competitiveness of restaurant brands [33]. Displaying sustainable menus can also increase guests’ willingness to engage in low-carbon activities [34,35]. Although these studies provide valuable information on sustainable food services in tourism, they lack comprehensive analysis of the entire dining experience for tourists. Through the service design of low-carbon services that enhance the food experience, it is possible to effectively influence the behavior of both tourists and providers, which can contribute to reducing the carbon footprint of food in tourism.

2.2. Low-Carbon Tourism Attitude and Behavior of Tourists

Low-carbon tourism is a response in action to the notions of sustainable tourism and ecotourism, it is a mode of operation [36]. Our study of tourists’ low-carbon attitudes and behaviors is based on the existing research literature on sustainable tourism. The term “tourist carbon attitude” refers to the attitude of tourists towards low-carbon tourism when engaging in tourism activities [37]. When tourists are more concerned about the environment, they are more likely to reduce behaviors that harm the environment [38,39]. “Tourist carbon behavior” refers to the behaviors of tourists related to carbon emissions when engaging in tourism activities [40]. Low-carbon behaviors include being willing to pay more for green hotels, saving water and energy during the tourism process, reducing waste, and recycling [41]. Tourists who properly handle solid waste and prefer to consume local products are known as environmentally friendly tourists. They are more concerned about carbon offset credits, product eco-labels, tourism charity, and environmental issues [42,43]. Sustainable consumption of food is identified as a key component of sustainable food in sustainable food reports [44]. In a book published in 2020, China’s Green Consumption Initiative describes green consumption practices such as energy-saving acts, resource conservation, waste separation, not wasting food, local food, and decreasing solid waste [45,46].

With the growing popularity of the sustainable concept, people have become more inclined towards sustainability attitudes. However, some studies have found that there is a gap between the environmental attitudes expressed by tourists and their actual tourism behaviors. They may express a friendly attitude, but they are unlikely to renounce the pleasure of less sustainable choices [47,48,49,50]. Many scholars have collected questionnaires and quantitatively analyzed tourists’ willingness for sustainable tourism. They believe that tourists’ altruistic values are the inducement for their environmental protection behavior [51]. They have identified five factors that influence tourists’ environmental protection behavior: habitual behavior, environmental attitude, available facilities, the need to rest from environmental responsibilities, and tourism social responsibility [19]. It has been found that young people have a positive attitude towards sustainable food, but their willingness to actually purchase sustainable food is low. Participation, perceived availability, certainty, perceived consumer efficacy, values, and social norms have been identified as factors contributing to this gap [52]. While many studies have focused on tourists’ low-carbon attitudes, few researchers have used qualitative analysis to explore the reasons for the gap between tourists’ low-carbon attitudes and behaviors.

In summary, most studies on low-carbon tourism food have focused on the production and carbon footprint of food, and analysis of individual food services. There is a lack of research on low-carbon food services from a systemic perspective. Most studies on tourists have been quantitative surveys of their low-carbon tourism intentions, with few studies examining their actual behavior. Some researchers suggest the need for qualitative studies based on green segmentation of consumers to investigate this phenomenon [53]. Therefore, it is crucial to identify and study tourist attitudes and behaviors to determine their low-carbon food service needs.

3. Research Methods

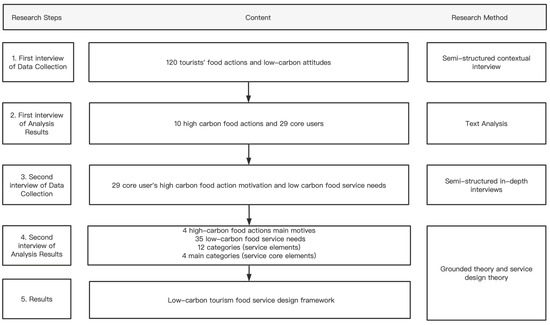

We first conducted a desk research, which can help this study to better understand the current status of the low-carbon transition in China’s tourism industry. Secondly, user research and analysis were conducted based on grounded theory using the interview method, Figure 2 shows the research process of this study.

Figure 2.

Research process.

3.1. Grounded Theory

Grounded theory is a set of analytical methods that are organized and generalized from primary sources, With the development of grounded theory, three schools of thought have been formed, namely, “classical grounded theory”, “procedural grounded theory”, and “constructivist grounded theory” [54]. This study analyzed the user interview data based on the coding method of procedural grounded theory. The main reasons for using this research method are as follows:

This study is without a direct hypothesis, and its variables and experimental model are unclear as food service involves a complex service system with various stakeholders [24].

- (1)

- On the other hand, this study was unable to predict the behavior and requirements of food-service providers and visitors in advance. Therefore, it is necessary to use the exploratory Grounded Theory and conduct in-depth interviews to uncover the underlying elements and relationships [55].

- (2)

- Procedural grounded theory often uses purposive sampling, which is consistent with the purpose of our study [56].

- (3)

- The coding method of procedural grounded theory can make our element extraction process clearer [57].

3.2. Interview Method

In qualitative research, the interview method is one of the most widely used and most researched methods by researchers to uncover the real behavioral and psychological characteristics of research subjects [58,59]. The reasons for using the interview method in this study were:

- (1)

- It is difficult to obtain more realistic responses in the form of questionnaires, both in terms of finding tourists’ high-carbon food actions and tourists’ attitudes toward low-carbon tourism.

- (2)

- Interviews can leave relatively sufficient room for participants to think and express themselves, and the researcher can also carefully observe the external expressions and internal psychology of the interviewees, so as to understand as deeply as possible the attitudes and emotions of the interviewees towards this dine-in low-carbon service.

- (3)

- The exploration of participants’ food actions and attitudes requires the researcher to guide the participants to recall a complete dine-in experience, and the researcher can help the participants recall more details through continuous and repeated questioning.

Therefore, to gain a comprehensive understanding of the tourist dine-in experience and to discover the real food behavior of low-carbon-attitude-friendly tourists, we used only the interview method for the user study.

Two semi-structured contextual interviews were conducted for this study, to unpack the research purpose-based conversation around the tourists’ food experiences and guide tourists to articulate how they were acting at the time and their moods and attitudes in a particular context [60]. The second in-depth core user interview was conducted to discover the reasons for the high-carbon food actions and their requirements for low-carbon-tourism food services.

The recruitment of participants needs to take into account differences in food available in different regions of China and differences in the food consumption of tourists [61]. In the first random food street interviews, four cities in South, North, Central, and Eastern China were chosen (Guangzhou, Beijing, Chengdu, Xiamen). These four cities are known for their morning tea, northern food, hot pot, and seafood respectively [62,63,64,65]. We selected interview moderators in each city in close proximity to well-known tourist destinations. On the same holiday, four moderators randomly selected tourists on the street until each obtained 30 valid interview texts [66] (see Appendix A for specific participant information). After analyzing the interview data, we obtained 29 core users. The participants in the second in-depth interview were 29 core users, a group of tourists who were somewhat conscious of low-carbon environmental protection and friendly towards low-carbon-tourism food practices. Their high-carbon food actions are much easier to change [16,67]. Each participant consents to the use and disclosure of their information. Table 1 shows a summary of the two interviews.

Table 1.

Summary of the two interviews.

4. Research Process and Results

4.1. Analysis and Results of the First Interview Data Collection

4.1.1. First Interview of Data Collection

A total of 120 valid text data were collected in the first interviews. The purpose of the interviews was to discover the high-carbon food actions of the participants, as well as to find the core users. Each interview lasts for 5–10 min. Table 2 shows the participants information.

Table 2.

First interview participants information.

Before beginning an interview, moderators should have a clear understanding of the primary interview objectives, but they should not have any predetermined preconceptions [68]. For smooth data collection, we designed the interview guide before the interview as shown in Table 3. The first part of the interview guide was constructed to collect information from the participants, The second part to guide them—in a way that did not indicate the purpose of the study—to recall the actions that arose during the food experience [25,26,44]. The third part explores participants’ attitudes toward low-carbon information, products, services, and rules of restaurants during their tourism food experiences [37,41,42,43]. The framework for the interviews was formed based on the main purpose of the first round of research, while the detailed interview questions were based on realistic interview situations and the sensitivity of the moderators.

Table 3.

First round of interview guide.

4.1.2. First Interview of Analysis Results

Food-related tourism carbon emissions are associated with food waste, garbage accumulation, and resource and energy waste caused by tourists [69,70]. From the interview data, we obtained 33 food actions. After excluding non-carbon-related actions that do not result in high-carbon emissions, a total of 10 high-carbon food actions remained. Table 4 shows the summary of the participants’ high-carbon food actions.

Table 4.

Summary of participants’ high-carbon food actions.

By analyzing the participants’ attitudes towards low-carbon information, products, services, and rules of restaurants during their tourism food experiences, we identified 36 tourists who had a friendly attitude towards low-carbon tourism. Table 5 provides an example of the screening process used to identify these friendly tourists.

Table 5.

Example of participant attitude refinement.

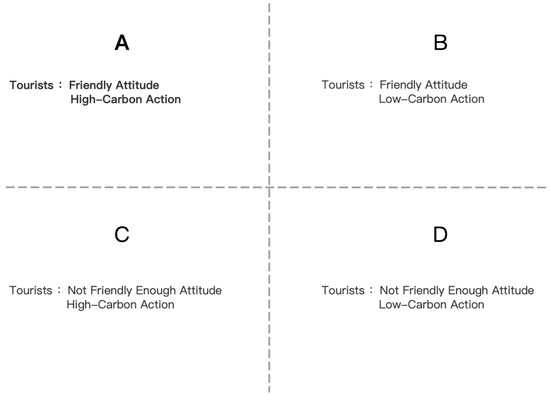

Out of the 36 tourists who have a friendly attitude towards low carbon, 29 had high-carbon food actions. In terms of participants’ real food actions and attitudes towards low-carbon tourism, we divided the participants in this interview into four categories as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Classification of participants.

Tourists in Category A are friendly to low-carbon tourism but have some high-carbon actions when it comes to real food experiences; they are concerned about low-carbon service in restaurants and have some low-carbon awareness, only that high-carbon actions arise for various reasons. Category B is for tourists who have a friendly attitude towards low-carbon tourism and do not act in a high-carbon way during their food experience, who have a good awareness of low-carbon and are aware of the environmental impact of their actions and show it in their real actions. Category C is for tourists who are not concerned about low-carbon tourism, feel that low carbon is not very important in tourism, and have real high-carbon actions. Category D is for tourists who are not concerned about low-carbon tourism and feel that low carbon is not very important in tourism, although they did not have any high-carbon food actions this time. Users of category B are well in control of their actions without much help. Users in categories C and D, because of their poor attitudes towards low-carbon tourism, find it difficult to make design interventions. Category A tourists have a friendly attitude towards low-carbon tourism and are more likely to intervene in action by design, so our core user group is the category A users. Their needs for low-carbon-tourism food services are more worthy of our attention.

4.2. Analysis and Results of the Second-Interview Data Collection

4.2.1. Second Interview of Data Collection

A total of 29 valid text data from in-depth interviews were collected in the second interview. Participants are 29 core users. Table 6 shows the participants information.

Table 6.

Second interview participants information.

Each interview lasts for 30–40 min. The purpose of this interview was to discover the reasons for the high-carbon food actions of core users and their requirements for low-carbon-tourism food services. Based on the results of the first interview, the interview guide explores core users in two ways: first, to explore the causes of their high-carbon food action, and second, to explore their requirements for low-carbon food services. Interview-specific questions were asked based on the results of the first core users interview. Table 7 shows the second interview guide.

Table 7.

Second round of interview guide.

4.2.2. Second Interview of Analysis Results

Due to the large number of Chinese transcripts involved in the interview sample and coding process, only the results of the analysis are presented in this study.

The original core users interview data was processed based on Grounded Theory to uncover the reasons for core users high-carbon food actions and suggestions for low-carbon food services. A total of 145 sentences were extracted from the section on the causes of high-carbon food actions, and the inductive classification yielded a total of 34 initial causes and 12 sub-causes after secondary induction. A further grouping of the 12 sub-causes revealed that the reasons why core users would have high-carbon food actions fall into four main categories: (A) the participant is limited by real conditions (75.86%), (B) the participant is influenced by others (65.52%), (C) the participants’ actions are influenced by food attitudes (62.07%), and (D) the participant has a lack of low-carbon knowledge(48.28%).

Open coding is a conceptualization of the source material that has been repeatedly categorized and generalized. A total of 153 raw sentences were extracted from the original text about low-carbon food services. A total of 35 low-carbon food-service needs were obtained by analyzing user touchpoints and psychology from the perspective of user research. Table 8 shows the process of extracting the service design needs.

Table 8.

The extraction process for the user needs.

Axial coding is a further conceptual refinement based on open coding, specifies the attributes and dimensions of the categories [71]. We classified semantically similar concepts among the 35 service needs extracted and distilled them into 12 categories. Table 9 shows the classification results.

Table 9.

12 Categories.

Selective coding is the exploration of the intrinsic connection between axial codes [72].

Find the main categories and inductively refine them to obtain the core categories that can connect all categories [73]. We studied low-carbon tourism food services and identified four low-carbon tourism food service design elements according to the logical relationship between different service categories: Low-Carbon Information Show Service, Low-Carbon Service Product Attractiveness Enhancement, Low-Carbon Food Environment Atmosphere Creation, Low-Carbon-Behavior of Service Provider. We annotated the extracted categories, and Table 10 shows the main and relevant category concepts.

Table 10.

Composition of the main category.

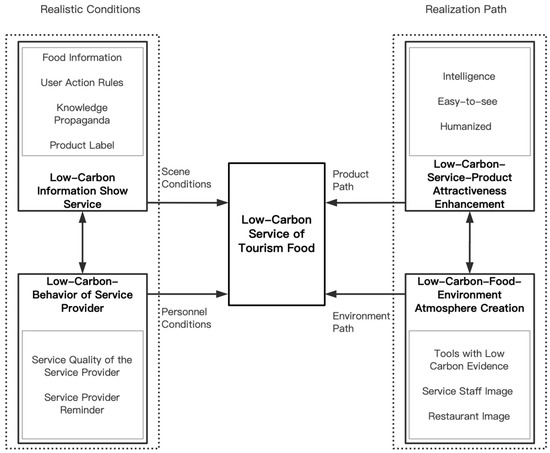

Based on the coding results, we developed a low-carbon tourism food service design framework centered on tourists: P.E.B.I. Low-Carbon Tourism Food Service Design Framework shown in Figure 4. The framework includes:

Figure 4.

P.E.B.I. Low-Carbon Tourism Food Service Design Framework.

P: Low-Carbon Service Product Attractiveness Enhancement, E: Low-Carbon Food Environment Atmosphere Creation, B: Low-Carbon Behavior of Service Provider, and I: Low-Carbon Information Show Service. Next, we discuss around this framework.

5. Discussion

Our core category is Food Low-Carbon Service, which refers to the low-carbon service that tourists experience when engaging in food-related activities. The core category enables the extracted service design elements to be strung together into a coherent whole. The structure of the storyline includes the Low-Carbon Information Show Service and the Low-Carbon Behavior of Service Providers, which are the realistic conditions for designing low-carbon tourism food services. The implementation of low-carbon tourism food service design requires service scenarios with low-carbon information display and service providers with low-carbon literacy. Low-Carbon Service Product Attractiveness Enhancement and Low-Carbon Food Environment Atmosphere Creation are the realization paths of Low-Carbon Tourism Food Service Design. By enhancing the attractiveness of Low-Carbon service products and creating a Low-Carbon service environment, we can improve the quality of low-carbon tourism food service.

5.1. Realistic Conditions: Service Scenarios and Service Personnel Guarantee the Realization of Low-Carbon Tourism Food Service Design

Low-Carbon Information Show Service and Low-Carbon Behavior of Service Provider is the foundation of low-carbon tourism food services design, which is a realistic condition to have. Low-Carbon Information Show Service and Low-Carbon-Behavior of Service Provider constitute the foundation for the realization of low-carbon tourism food services design, and are the essential conditions that must be met. The presence of Low-Carbon Information Show Service and Low-Carbon-Behavior of Service Provider directly impacts the establishment of low-carbon tourism food services. There is an interplay between Low-Carbon Information Show Service and Low-Carbon Behavior of Service Provider. A complete low carbon information show service can help service providers to provide more specific low carbon services to core user. Low carbon behavior of service providers can help core user to better understand the low carbon information displayed.

5.1.1. Low-Carbon Information Show Service

Low-Carbon Information Show Service is the scene condition for implementing low-carbon tourism food service design. The low-carbon tourism food service design system cannot be separated from the scene with low-carbon information display, which can better convey the information of low-carbon food, rules, and knowledge in the restaurant to users through service design, so that users can understand the complete information of low-carbon products and the low-carbon services provided by the restaurant. Through interviews, we found that users expect low-carbon information displays to be more intuitive and distinct from other types of information displays. The guiding information should include all necessary information to help users make informed decisions.

5.1.2. Low-Carbon Behavior of Service Provider

Low carbon literate service providers are the personnel condition to achieve low carbon tourism food service design. Low-carbon tourism food service needs to be provided by low-carbon literate service providers to provide professional, timely and proactive services to users. Professional low-carbon services by service providers can give users confidence, timely services can help users better avoid high-carbon food actions, and proactive services can help users understand the restaurant’s low-carbon products and low-carbon rules. Through the interviews, we found that the core users prefer the service staff to improve the low-carbon service standard, especially the two aspects of service quality assurance and low-carbon reminder to the users.

5.2. Realization Path: Service Products and Service Environment to Enhance the Effect of Low-Carbon Tourism Food Services

The Low-Carbon Service Product Attractiveness Enhancement and Low-Carbon Food Environment Atmosphere Creation are ways to enhance the effect of low-carbon tourism food services, and they are the realization path to promote the development of low-carbon tourism food services. There is also interplay between Low-Carbon-Service-Product-Attractiveness Enhancement and Low-Carbon-Service-Environment Atmosphere Creation. Enhancing the quality of service products through intelligence, ease of see and humanized can reduce the burden on the service environment and create a more low carbon service environment for core user. Low-Carbon-Service-Environment Atmosphere Creation positively influences the low-carbon service product by creating a low-carbon image of the service tool, the service staff and the service restaurant, and increases core user trust in the service product.

5.2.1. Low-Carbon Service Product Attractiveness Enhancement

Low-Carbon-Service-Product-Attractiveness Enhancement is the product path to promote the development of low-carbon tourism food services. In order to enhance the low-carbon experience of core users, the intelligence, ease of seeing and humanization of service products should be enhanced. Service products must be able to give users positive feedback. The feedback method can be rewards or voice prompts. As core user do not receive feedback, it is difficult for them to maintain low-carbon behavior; thus, designing a multi-sensory response service approach to give core user timely low-carbon feedback on their food behavior can increase their confidence and willingness to be low-carbon [74,75]. The core users in the interviews mentioned that they wanted low carbon food services to be more interesting and reliable.

5.2.2. Low-Carbon Food Environment Atmosphere Creation

Creating a low-carbon service environment is an effective way to promote the development of low-carbon tourism food services. By providing have low-carbon evidence service tools and enhancing the low-carbon image of service personnel and restaurants, a low-carbon food environment can be created, which can subtly influence core users’ high-carbon food actions. Through interview, we found that core user easily combine “clean” with “low-carbon,” and clean products or a clean environment allows them to subconsciously maintain low-carbon actions with more ease. Therefore, the most important thing to focus on when creating a low-carbon atmosphere in restaurants is the clean visual image.

Based on the above analysis, under the background of low-carbon transformation in the tourism industry, future low-carbon tourism food service design should consider low-carbon information display design, Low-carbon ordering system design, low-carbon food environment design, and low-carbon service training for employees. We have provided design suggestions for these four design directions according to the analysis results. Table 11 shows the design suggestions for low-carbon tourism food services.

Table 11.

Design suggestions for low-carbon tourism food services.

6. Conclusions

The majority of the direct outcomes of high-carbon behavior in tourism dining-in experiences are related to food waste and restaurant-material waste, according to the findings of this study. The production of methane during the disposal of food waste has made food waste a significant global problem in recent years. Methane is a high-emitting greenhouse gas, and methane emission reduction is also a way to achieve low-carbon tourism [76,77].

Our research focuses on the dine-in experience of tourists during their travels and introduce the concept of low-carbon tourism food. Our study identifies the core users by analyzing the food behavior and attitude towards low-carbon among tourists. Through analyzing the underlying reasons for the high-carbon behavior of core users and exploring their needs for low-carbon tourism food services, we aim to extract key design elements for low-carbon tourism food services.

The reasons for high-carbon food behavior among core users can be categorized into four main categories: (A) limited by real conditions, (B) influenced by others, (C) influenced by food attitudes, and (D) lack of low-carbon knowledge. Based on these reasons, we identified 35 core user needs for low-carbon tourism food services, which were further categorized into 12 subcategories and four main categories: (1) Low-Carbon Information Show Service, (2) Low-Carbon Service Product Attractiveness Enhancement, (3) Low-Carbon Food Environment Atmosphere Creation, and (4) Low-Carbon Behavior of Service Providers. We identified the core category of Low-Carbon Food Service and developed a systematic framework for Low-Carbon Tourism Food Service Design based on the needs of core users. Realistic conditions for building low-carbon tourism food services include Low-Carbon Information Show Service and Low-Carbon Behavior of Service Providers, while Low-Carbon Food Environment Atmosphere Creation and Low-Carbon Behavior of Service Providers can also help to promote the development of low-carbon tourism food services.

It is also crucial to recognize that our study has some limitations; the element extraction data comes solely from tourists, the study area is limited to four cities in China, and the applicability to other types of tourists and other nations and locations is not addressed in this paper. In order to obtain real feedback from the core user, the data was collected using an interview method and the analysis of primary data using only qualitative analysis, which also has limitations.

In the future, based on this study, the research objects of the study can be extended to low-carbon-tourism-friendly-tourists-with-high-carbon-behaviors in tourism transportation, sightseeing, entertainment, shopping, and accommodation to observe whether their real tourism behaviors are low-carbon. The scope of the study will also take into account pre-tour and after-tour studies in order to provide a complete observation of the tourism behaviors of the research object. The research methodology will use a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods for the next steps in the design and experiments. The aim will be to reduce the high-carbon behaviors of low-carbon-tourism-friendly tourists in terms of tourism transportation, tourism sightseeing, tourism entertainment, tourism shopping, and tourism accommodation, and to better achieve the goal of low-carbon tourism.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. and Y.P.; methodology, Y.L.; software, Y.L. and C.Y.; validation, Y.P. and Y.L.; formal analysis, Y.L.; investigation, Y.L.; resources, Y.L.; data curation, Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L. and C.Y.; visualization, Y.L. and X.Z.; supervision, Y.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. The raw data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

| Guang Zhou | Age | Gender | Source | Education | Work |

| vg1 | 35 | male | local tourists | Three-year college education | Self-employed |

| vg2 | 43 | female | local tourists | Three-year college education | Government staff |

| vg3 | 29 | male | local tourists | Master | Corporate staff |

| vg4 | 27 | female | local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Government staff |

| vg5 | 31 | male | local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Corporate staff |

| vg6 | 30 | male | local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Corporate staff |

| vg7 | 26 | female | local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Corporate staff |

| vg8 | 42 | female | local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Self-employed |

| vg9 | 25 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Corporate staff |

| vg10 | 27 | male | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Corporate staff |

| vg11 | 22 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vg12 | 23 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vg13 | 25 | male | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vg14 | 26 | female | non-local tourists | Master | Student |

| vg15 | 24 | male | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vg16 | 30 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Corporate staff |

| vg17 | 27 | female | non-local tourists | Three-year college education | Government staff |

| vg18 | 31 | male | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Corporate staff |

| vg19 | 22 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vg20 | 23 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vg21 | 27 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Corporate staff |

| vg22 | 29 | female | non-local tourists | Master | Teacher |

| vg23 | 35 | male | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Self-employed |

| vg24 | 38 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Corporate staff |

| vg25 | 45 | male | non-local tourists | Three-year college education | Self-employed |

| vg26 | 46 | female | non-local tourists | Three-year college education | Government staff |

| vg27 | 20 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vg28 | 21 | male | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vg29 | 22 | male | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vg30 | 21 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| Beijing | Age | Gender | Source | Education | Work |

| vb1 | 32 | male | local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Government staff |

| vb2 | 25 | female | local tourists | Master | Student |

| vb3 | 27 | female | local tourists | Master | Corporate staff |

| vb4 | 22 | female | local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vb5 | 36 | male | local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Self-employed |

| vb6 | 37 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Corporate staff |

| vb7 | 34 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Corporate staff |

| vb8 | 32 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Corporate staff |

| vb9 | 29 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Corporate staff |

| vb10 | 41 | male | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Government staff |

| vb11 | 26 | male | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Corporate staff |

| vb12 | 26 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Corporate staff |

| vb13 | 29 | female | non-local tourists | Doctor | Student |

| vb14 | 32 | male | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Self-employed |

| vb15 | 30 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Self-employed |

| vb16 | 34 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Corporate staff |

| vb17 | 29 | female | non-local tourists | Three-year college education | Self-employed |

| vb18 | 30 | male | non-local tourists | Doctor | Student |

| vb19 | 32 | male | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Corporate staff |

| vb20 | 31 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Corporate staff |

| vb21 | 37 | male | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Self-employed |

| vb22 | 37 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Government staff |

| vb23 | 34 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Corporate staff |

| vb24 | 26 | male | non-local tourists | Master | Corporate staff |

| vb25 | 24 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Corporate staff |

| vb26 | 27 | female | non-local tourists | Master | Corporate staff |

| vb27 | 23 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vb28 | 22 | male | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vb29 | 20 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vb30 | 25 | male | non-local tourists | Master | Student |

| Cheng Du | Age | Gender | Source | Education | Work |

| vc1 | 23 | female | local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vc2 | 22 | female | local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vc3 | 24 | male | local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vc4 | 21 | male | local tourists | Three-year college education | Student |

| vc5 | 27 | female | local tourists | Master | Student |

| vc6 | 31 | male | local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Corporate staff |

| vc7 | 25 | female | local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Government staff |

| vc8 | 28 | female | local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Self-employed |

| vc9 | 19 | female | local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vc10 | 18 | male | local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vc11 | 24 | female | local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vc12 | 27 | female | local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Corporate staff |

| vc13 | 28 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Government staff |

| vc14 | 32 | female | non-local tourists | Doctor | Teacher |

| vc15 | 33 | male | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Corporate staff |

| vc16 | 23 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vc17 | 22 | male | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vc18 | 23 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vc19 | 23 | male | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vc20 | 24 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vc21 | 22 | male | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vc22 | 20 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vc23 | 21 | male | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vc24 | 20 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vc25 | 20 | male | non-local tourists | Three-year college education | Student |

| vc26 | 21 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vc27 | 23 | male | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vc28 | 24 | male | non-local tourists | Three-year college education | Corporate staff |

| vc29 | 24 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vc30 | 28 | female | non-local tourists | Master | Government staff |

| Xia Men | Age | Gender | Source | Education | Work |

| vx1 | 24 | female | local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Corporate staff |

| vx2 | 46 | male | local tourists | Three-year college education | Government staff |

| vx3 | 26 | female | local tourists | Master | Student |

| vx4 | 27 | male | local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vx5 | 22 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vx6 | 23 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vx7 | 19 | male | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vx8 | 19 | female | non-local tourists | Three-year college education | Student |

| vx9 | 18 | male | non-local tourists | high school | Student |

| vx10 | 24 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vx11 | 26 | male | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Corporate staff |

| vx12 | 23 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vx13 | 24 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vx14 | 26 | male | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Self-employed |

| vx15 | 23 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vx16 | 22 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vx17 | 20 | male | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vx18 | 21 | male | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vx19 | 20 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vx20 | 21 | male | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vx21 | 23 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vx22 | 23 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vx23 | 19 | male | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vx24 | 20 | male | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vx25 | 21 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vx26 | 20 | male | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vx27 | 19 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vx28 | 24 | male | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vx29 | 24 | female | non-local tourists | Bachelor’s degree | Student |

| vx30 | 26 | male | non-local tourists | Master | Student |

References

- Lenzen, M.; Sun, Y.-Y.; Faturay, F.; Ting, Y.-P.; Geschke, A.; Malik, A. The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Guan, D.; Crawford-Brown, D.; Zhang, Q.; He, K.; Liu, J. A low-carbon road map for China. Nature 2013, 500, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tukker, A.; Jansen, B. Environmental impacts of products: A detailed review of studies. J. Ind. Ecol. 2006, 10, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H. The Impact of the Tourist Industries on the Agricultural Sectors: The Competition for Resources and the Market for Food Provided by Tourism; Social & Sectoral Planning, National Planning Agency: Kingston, Jamaica, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. Tasting tourism: Travelling for food and drink: Priscilla Boniface. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 627–628. [Google Scholar]

- Bélisle, F.J. Tourism and food production in the Caribbean. Ann. Tour. Res. 1983, 10, 497–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, T.Y. Developing a dual-perspective low-carbon tourism evaluation index system for travel agencies. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 1604–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orea-Giner, A.; Fusté-Forné, F. The way we live, the way we travel: Generation Z and sustainable consumption in food tourism experiences. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 330–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, G.; Page, S. Urban tourism research: Recent progress and current paradoxes. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Carbon Emission Accounting and Optimization of Urban Tourism System. Doctoral Dissertation, Henan University, Kaifeng, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. Research on the Mechanism of Factors Influencing Low-Carbon Behavior of Urban Tourist Hotels. Doctoral Dissertation, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Zhang, M. Route Choice of low-carbon industry for global climatechange: An issue of China tourism reform. Energy Procedia 2011, 5, 2283–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Guo, W.; Fan, J.; Guo, J.; Wang, M.; Zen, A. Policy framework and technology innovation policy of carbon peak and carbon neutrality. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2022, 37, 435–443. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Gössling, S. Sustainable Culinary Systems; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Amicarelli, V.; Aluculesei, A.-C.; Lagioia, G.; Pamfilie, R.; Bux, C. How to manage and minimize food waste in the hotel industry: An exploratory research. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2022, 16, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yang, M. The development of an evaluation model for low carbon tourism consumption behaviour and its empirical application. Consum. Econ. 2018, 34, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bergin-Seers, S.; Mair, J. Emerging green tourists in Australia: Their behaviours and attitudes. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2009, 9, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramayah, T.; Lee, J.W.C.; Lim, S. Sustaining the environment through recycling: An empirical study. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 102, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Merrilees, B.; Coghlan, A. Sustainable urban tourism: Understanding and developing visitor pro-environmental behaviours. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Su, B.; Tan, J. Developing an evaluation index system for low-carbon tourist attractions in China–A case study examining the Xixi wetland. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K.; Moscardo, G. Encouraging sustainability beyond the tourist experience: Ecotourism, interpretation and values. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 1175–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhanen, L.; Weiler, B.; Moyle, C.-L.; McLennan, C.-L.J. Trends and patterns in sustainable tourism research: A 25-year bibliometric analysis. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 517–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, N.; Law, R. Categorical classification of tourism dining. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 819–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomi, A.; Tussyadiah, I.P. Building the sociomateriality of food service. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 89, 102553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhu, H. A Review of Tourism Food Waste Research and Prospects. Hum. Geogr. 2021, 1003–2398. [Google Scholar]

- Mobley, C.; Vagias, W.M.; De Ward, S.L. Exploring additional determinants of environmentally responsible behavior: The influence of environmental literature and environmental attitudes. Environ. Behav. 2010, 42, 420–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.; Avieli, N. Food in tourism: Attraction and impediment. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 755–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Rand, G.E.; Heath, E. Towards a framework for food tourism as an element of destination marketing. Curr. Issues Tour. 2006, 9, 206–234. [Google Scholar]

- Sims, R. Food, place and authenticity: Local food and the sustainable tourism experience. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Garrod, B.; Aall, C.; Hille, J.; Peeters, P. Food management in tourism: Reducing tourism’s carbon ‘foodprint’. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 534–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poore, J.; Nemecek, T. Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science 2018, 360, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Sharma, P.; Shu, S.; Lin, T.-S.; Ciais, P.; Tubiello, F.N.; Smith, P.; Campbell, N.; Jain, A.K. Global greenhouse gas emissions from animal-based foods are twice those of plant-based foods. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Kim, H.M.; Kim, I. The antecedent and consequences of brand competence: Focusing on the moderating role of the type of server in the restaurant industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 50, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, K.W.; Kim, D.; Kim, I. Robotic restaurant marketing strategies in the era of the fourth industrial revolution: Focusing on perceived innovativeness. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Joung, H.W.; Choi, E.K.; Kim, H.S. Understanding vegetarian customers: The effects of restaurant attributes on customer satisfaction and behavioral intentions. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2022, 25, 353–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M. Theoretical and Practical Aspects of Low Carbon Tourism. Ph.D. Thesis, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dolnicar, S.; Crouch, G.I.; Long, P. Environment-friendly tourists: What do we really know about them? J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binti Aman, A.L. The Influence of Environmental Knowledge and Concern on Green Purchase Intention the Role of Attitude as a Mediating Variable. Ph.D. Dissertation, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Sabate, R.; Sabaté, J. Consumer attitudes towards environmental concerns of meat consumption: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Evaluating regional low-carbon tourism strategies using the fuzzy Delphi-analytic network process approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.-T.J.; Lee, J.-S.; Sheu, C. Are lodging customers ready to go green? An examination of attitudes, demographics, and eco-friendly intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairweather, J.R.; Maslin, C.; Simmons, D.G. Environmental values and response to ecolabels among international visitors to New Zealand. J. Sustain. Tour. 2005, 13, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S.; Matus, K. Are green tourists a managerially useful target segment? J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2008, 17, 314–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, C.; Belchior, C.; Hoogeveen, Y.; Westhoek, H.; Manshoven, S. Food in a Green Light—A Systems Approach to Sustainable Food; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, A.M.; MacRae, R. Local Food Plus: The connective tissue in local/sustainable supply chain development. Local Environ. 2013, 18, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S. Research on the construction of green consumption model in China in the new era. Ecol. Econ. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.J.; Lin, L.M. Exploring attitude–behavior gap in sustainable consumption: Comparison of recycled and upcycled fashion products. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echegaray, F.; Hansstein, F.V. Assessing the intention-behavior gap in electronic waste recycling: The case of Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufique, K.M.R.; Islam, S. Green marketing in emerging Asia: Antecedents of green consumer behavior among younger millennials. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2021, 15, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, L. Reducing the Attitude-Behavior Gap in the Context of Sustainable Tourism. Batchelor’s Thesis, Metropolia University of Applied Sciences, Helsinki, Finland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.S.; Stepchenkova, S. Altruistic values and environmental knowledge as triggers of pro-environmental behavior among tourists. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1575–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the consumer “attitude–behavioral intention” gap. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElHaffar, G.; Durif, F.; Dubé, L. Towards closing the attitude-intention-behavior gap in green consumption: A narrative review of the literature and an overview of future research directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 122556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.; Pan, Y. Research on influencing factors of service interactive experience of digital gas station—The case from China. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 2151–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, I.T. Sampling in qualitative research. Purposeful and theoretical sampling; merging or clear boundaries? J. Adv. Nurs. 1997, 26, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, D.; Chen, X.; Meng, F.; Deng, Y. Application of programmatic version of grounded theory in psychological counseling training research. Chin. J. Ment. Health 2012, 26, 648–652. [Google Scholar]

- Fontana, A.; Frey, J. The art of science. Handb. Qual. Res. 1994, 361376. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z. Synthesis of Sociological Methods—Taking Questionnaire and Interview as Examples. Soc. Sci. 2016, 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, H. Research interview and its application status and prospect. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 1202–1205. [Google Scholar]

- Aspers, P.; Corte, U. What is qualitative in qualitative research. Qual. Sociol. 2019, 42, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Ma, X.Z. Tourist Experience Based on Guangzhou Tourism Market Survey. J. Sun Yatsen Univ. Forum. 2006, 1007–1792. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.; Niu, Y. Exploring Chinese and American tourists’ perceptions of food tourism in Beijing based on user reviews. Mod. Urban Stud. 2022, 8, 122–129. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Fen, M. A study on the image of Chengdu’s cuisine based on tourists’ perceptions. Gastron. Res. 2022, 36, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C.; Hou, Z.Q. Tourism Destination Image Perception Based on IWOM—Xiamen City as an Example. Trop. Geogr. 2013, 33, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvalsvik, F.; Øgaard, T. Dyadic interviews versus in-depth individual interviews in exploring food choices of Norwegian older adults: A comparison of two qualitative methods. Foods 2021, 10, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.P. A study on food waste behaviour of restaurant consumers in tourist cities. Resour. Sci. 2018, 40, 1186–1195. [Google Scholar]

- Weed, M. Research quality considerations for grounded theory research in sport & exercise psychology. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2009, 10, 502–510. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; Lu, L.; Yao, X.; Zhang, W.; Liu, W. UNEP Food Waste Index Report; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Capstick, S.; Khosla, R.; Wang, S.; van den Berg, N. Bridging the gap–the role of equitable, low carbon lifestyles. In The Emissions Gap Report; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, R.; Li, P.; Zhou, S. Research on the Dynamic Mechanism and Path of Virtual Reality Publishing Development. Publ. Sci. 2023, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Draucker, C.B.; Martsolf, D.S.; Ross, R.; Rusk, T.B. Theoretical sampling and category development in grounded theory. Qual. Health Res. 2007, 17, 1137–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Wu, T.; Yang, W.; Liang, Y. Research on the Driving Factors and Functional Mechanism of the Enterprise Technology Standards Alliance Facing the “Belt and Road”—Based on the Fusion Method of Text Mining and Procedural Grounded Theory. Nankai Manag. Rev. 2021, 24, 150–161. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst, M.O.; Banks, M.S. Humans integrate visual and haptic information in a statistically optimal fashion. Nature 2002, 415, 429–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Cao, S.; Pan, Y. The Relationship between the Use of Non-Verbal Information in Communication and Student Connectedness and Engagement in Online Design Education. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Defense Fund. Methane: A Crucial Opportunity in the Climate Fight. Available online: https://www.edf.org/climate/methane-crucial-opportunity-climate-fight (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Porter, S.D.; Reay, D.S.; Higgins, P.; Bomberg, E. A half-century of production-phase greenhouse gas emissions from food loss & waste in the global food supply chain. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 571, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).