Abstract

To better address the inequities and inequalities brought by the monotonous approach to low-carbon development, it is necessary to actively explore inclusive low-carbon development (ILCD) pathways, and low-carbon policy (LCP) synergy plays a crucial role in ILCD. This paper manually collected LCP data from 30 provinces in China from 2010 to 2019 and conducted a study using text analysis to measure LCP subject synergy, LCP tool synergy, and LCP overall synergy. At the same time, an indicator analysis framework of ILCD was constructed to measure the efficiency of ILCD at the provincial level through the super-efficient SBM model. On this basis, the impact of LCP synergy on regional ILCD is explored to reveal its mechanism of action, and heterogeneity is explored. The results show the following: (1) In general, LCP subject synergy, LCP tool synergy and LCP overall synergy all effectively promote regional ILCD. (2) Both LCP subject synergy and LCP tool synergy are indispensable. Policy synergy can positively affect ILCD only when both policy subjects and policy instruments are highly synergistic, while ILCD is significantly weakened when both policy subjects and policy instruments are lowly synergistic. (3) The stronger the innovation capacity of provinces, the stronger the contribution of LCP synergy to ILCD. (4) In non-resource-based regions, the effect of LCP subject synergy on regional ILCD is more significant, and the effect of LCP tool synergy is not significant, while the opposite is true for resource-based regions. The study plays a certain reference significance for the government to improve LCP synergy and promote regional ILCD.

1. Introduction

Addressing climate change is an important issue in the world today [1]. Since the introduction of low-carbon development, many countries have been actively exploring effective ways to synergize climate governance and economic growth. Major countries around the world have announced carbon peaking or carbon neutral targets [2], and a wide range of LCPs are aimed at promoting a low-carbon industrial transition, achieving sustainable economic development, and promoting coordinated social development [3]. However, at the national level, each country is at a different stage of development, with marked differences between countries in terms of their stage of economic development, resource endowment, ecological environment, and political systems [4]. The monotonous approach to low-carbon development ignores the different challenges and dilemmas faced by countries in achieving climate change goals, which may aggravate global inequality, slow down the intrinsic dynamics of economic development, and impede a sustainable global green transition and long-term climate governance [5]. At the industry level, low-carbon development means that the energy mix needs to be transformed from fossil to clean-energy-led, which will have a serious impact on labor-intensive traditional industries, bring about unemployment, health and security problems, lead to an increase in the gap between rich and poor, and hinder inclusive growth [6,7]. At the regional level, some regions have already decoupled their economic growth from carbon emissions and have taken the lead in achieving carbon peaking, while some other provinces are still in a state of pending decoupling and face greater pressure to reduce carbon and transition. Many local governments lack the ability to coordinate policies when faced with the constraints of both economic growth and carbon emission reduction and thus adopt a “one-size-fits-all” LCP, which hurts sustainable economic growth and social development [8]. At the enterprise level, some enterprises, especially small and micro-enterprises, are less able to resist risks in the process of low-carbon development due to their weak capital chain, limited resources and insufficient innovation capacity, and the “crowding-out effect” and “follow the cost effect” of energy saving and carbon reduction bring serious challenges to their survival and development [9]. At the residential level, the public’s participation in traditional low-carbon governance and willingness to live a low-carbon life still have much room for improvement, and the costs of low-carbon governance are often passed on to consumers through taxes or higher commodity prices, resulting in the public not becoming the direct beneficiaries of low-carbon development. Therefore, the global climate governance paradigm must promote a shift away from a single low-carbon development paradigm, take full account of the diversity and inclusiveness of low-carbon development approaches, and actively explore ILCD models.

As a comprehensive goal, ILCD requires comprehensive synergy among various elements and subjects in society, in which the government’s LCP plays a crucial macro-regulatory role, especially under the multi-objective orientation, the government’s choice of matching and comprehensive application of LCP is a key factor in the effectiveness of ILCD. China is today the world’s leading carbon emitter, and the Chinese government is actively assuming its international responsibility to address climate change, widely adopting and effectively implementing various LCPs and achieving remarkable results in the field of low-carbon development [10]. However, in reality, there are still some problems in China in terms of LCP synergy: First, the contradiction and conflict of LCP have led to the ILCD “going its way”. For example, since the central government announced the ‘3060’ carbon target in 2020, some local governments have adopted “campaign carbon peak” and “one-size-fits-all” policies to complete the carbon emission reduction tasks, which are not always appropriate or realistic. For example, the energy saving and emission reduction targets issued by different departments are not compatible in practice in the thermal power and steel industries [11]. Second, the duplication and singularity of LCP tools have led to the lack of ILCD efficiency. The government’s extensive use of target-setting instruments in promoting low-carbon development has resulted in duplication of resources, poor marketization, and a single form of policy instruments, which has reduced social participation and equality of opportunity, creating a silo of lack of coordination and integration between low-carbon development and inclusive growth [12], resulting in low ILCD efficiency. The above-mentioned practical problems make the regional ILCD lack a clear LCP as a basis, which leads to an imperfect long-term mechanism and thus hinders the transformation of results. The report of the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China proposes to actively and steadily promote carbon neutralization, which requires the government to strengthen inter-departmental communication and coordination, improve the quality of LCP, and at the same time, enrich policy tools and optimize resource allocation to improve the effect of LCP on the ground.

Much of the existing research on LCP treats single or multiple LCP as independent and examines the effectiveness of particular types of LCP, such as command-and-control, market regulation, public participation, etc. Some scholars also study the role of policy synergy on regional development from the level of macro policy effect evaluation. However, there are still some parts that need further improvement. On the one hand, the existing research on the measurement of LCP synergy is relatively singular, mainly focusing on combining several LCPs to observe their policy effects, and it lacks a microscopic portrayal of LCPs issuing subjects and policy tools from the perspective of LCP text analysis. On the other hand, the existing research on ILCD mainly focuses on the construction of an evaluation index system, and there is still room for further enrichment of ILCP measurement. At the same time, the existing studies on the influence factors of ILCP are weak, and LCP and its synergy are neglected as the key factors affecting ILCD. Few studies have systematically discussed the influence mechanism of LCP synergy on ILCD, and there is a lack of in-depth analysis from the perspective of different types of low-carbon policy synergy. In summary, this paper will focus on the following questions: (1) Can LCP synergy better contribute to regional ILCD? (2) How do the two types of LCP synergy (policy subject synergy and policy tools synergy) play different roles in regional ILCD, and what are their mechanisms? (3) Are regions at different stages of development and with different resource endowments affected to the same extent?

To this end, this paper takes 30 provinces in China from 2010 to 2019 as the research objects. Firstly, an “input–output” indicator system is constructed based on three dimensions: economic growth, social inclusion, and low-carbon development, and the efficiency of ILCD in different provinces is measured from the perspective of efficiency. Secondly, using text collection and analysis, we measured the degree of the synergy of regional LCP in terms of the synergy of LCP subjects and the synergy of LCP tools. Finally, the impact of LCP synergy on regional ILCD and the mechanism of the two types of policy synergy approaches are dissected, and the regional heterogeneity of this impact is further explored. The proposed policy recommendations may be beneficial for government departments to enhance LCP synergy, and they also provide some decision-making references for countries such as China to formulate LCP and promote regional ILCD more effectively.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. The “Literature Review and Theoretical Analysis” section summarizes the existing studies and sorts out the mechanism of LCP synergy on ILCD. The “Methods and Data” section clarifies the measurement tools and data sources of the main indicators. The “Empirical Results and Analysis” section reports the results of the empirical analysis. The “Conclusion” section summarizes the main findings of the study, while the “Discussion” section further explores the policy implications of the study.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Analysis

2.1. LCP Synergy, LCP Subject Synergy, and LCP Tools Synergy

The concept of “policy synergy” was first introduced by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) as a way to make public policies compatible, coordinated, and supported by different governments and government departments through communication and dialogue to solve complex problems and achieve common goals [13]. Most of the studies on policy synergy have been conducted from the macro-perspective of national governance, focusing on a series of issues such as national security, official promotion, and environmental protection, aiming to paint a picture of cooperative governmental governance [14], portray the performance of inter-governmental relations, compare the mechanisms of multi-subject interaction, and find ways to improve the effectiveness of social governance through social network analysis [15]. With the increasing severity of climate change, LCP and their synergy have gradually become the focus of attention of many scholars, and the existing studies have mainly achieved two results: first, starting from LCP themselves, we analyze the evolution and changes of LCP, the objectives of policy synergy and the classification of policy synergy [16,17]. The study finds that along with the urgency of climate change issues and the increasing complexity of contemporary national governance systems, the governance of climate change has gradually gone beyond the responsibility of individual public sectors and has begun to span multiple areas, increasingly becoming a transboundary issue [18]. To improve the level of low-carbon development and governance capacity, the coordination and interaction among various sectors for low-carbon development have become more frequent, and a trend of sectoral cooperation has emerged in the process of LCP formulation [19]. The goal of LCP synergy is to improve cross-border governance effectiveness and efficiency in addressing complex climate change issues through coherent LCP outputs that can be translated into coherent action across multiple institutions, thereby taking advantage of policy combinations, avoiding policy externalities, and reducing the costs of policy operations [20]. Second, it focuses on the effects of LCP and evaluates the effectiveness of LCP through qualitative and quantitative methods, combining regional-level indicators from various dimensions such as economy, energy, and the environment [21,22,23].

LCP subject synergy refers to the fact that LCP synergy has a plurality of subjects, i.e., the authority subjects involved in the LCP process are interconnected and participate in governance together. The narrow sense of subjects includes all the authority structures and policy structures involved in the LCP process, while the broad sense of subjects covers social organizations, enterprises, the public, and other actors. This approach not only increases the motivation of participants but also promotes the flow and sharing of information in the network, reduces the possibility of policy conflicts and offsets [24], improves policy coordination, and creates more effective and equitable solutions to climate problems [25]. In practice, various government departments can use a variety of tools to unify policy goals and coordinate the participation of all parties in the policy process. The General Office of the CPC Central Committee and the General Office of the State Council jointly promulgated the Regulations on the Handling of Official Documents by Party and Government Organs in 2012, which stipulates that “Party and government organs at the same level, and Party and government organs and other organs at the same level, may issue joint documents when necessary. China’s LCP is gradually evolving towards the direction of multi-body coordination, and cross-departmental cooperation is becoming more frequent and complex” [26].

LCP tools synergy refers to the multiplicity of instruments in LCP synergy, i.e., the content of LCP contains a variety of policy measures to jointly achieve policy goals [27]. LCP tools are measures to achieve climate governance goals, which are designed, organized, and applied to form policies. LCP tools are the means to achieve LCP goals, and the effective implementation of policies requires the synergy of policy instruments. In the classification of LCP tools, academics generally classify LCP into three categories: administrative-command, market-regulated, and public-participatory. The administrative-command type LCP tools highlight the legal and administrative means to directly manage and supervise production behaviors, which are mandatory and timely [28]. The disadvantage is that they are not flexible enough and may drive out the good money from the bad. Market-regulated LCP tools are designed by administrative bodies based on the “polluter pays” principle, aiming to solve the externality problem or internalize the externality through market mechanisms to guide the subjects to reduce carbon emissions [29]. Compared with administrative policy instruments, it gives individuals more autonomy to choose so that they can make the best choice with their benefits [30,31]. Public participation LCP tools are based on the growing popularity of low-carbon development concepts and the increasingly improved Internet environment, and they indirectly promote a stricter implementation and enforcement of relevant low-carbon laws, regulations, and technical standards through social opinion, moral pressure, exhortation, green consumption, etc. [32]. The extensive public participation in low-carbon governance can provide feedback to the government on the needs and opinions of various social strata and organizations through different participation mechanisms, thus reducing the implementation of government tracking and inspection activities and helping to improve policy inclusiveness and reduce government management costs [33].

2.2. Inclusive Low-Carbon Development

The ILCD is an extension of the concepts of inclusive growth, inclusive green growth, and low-carbon development. To address the growing income disparity, inequitable development opportunities, and unequal distribution of development outcomes in the process of economic development, the Asian Development Bank [34] first proposed inclusive growth, aiming to seek a coordinated social and economic development approach to growth and advocating equal participation of all in economic development opportunities and equal sharing of economic development outcomes [35,36]. Subsequently, many scholars and institutions have expanded the meaning of inclusive growth from the perspectives of promoting sustainable development, reducing poverty, alleviating development imbalance among regions, increasing employment opportunities, and promoting gender equality [37,38,39,40]. However, as economic development and industrialization progressed, the problems of ecological environment deterioration and natural resources depletion have become more and more obvious and become important factors limiting the development of regions, and the inclusive growth model containing only “economic–social” two-dimensional objectives can no longer meet the development needs of many regions. The inclusive green development model, which includes “economic–social–environmental” three-dimensional objectives, has been developed. Inclusive Green Development was first formally introduced at Rio + 20 in 2012 to connect inclusive growth and green development with the world’s interests [41], and in March 2016, the United Nations announced the new sustainable development goals (SDGs), and many countries and regions began to implement this new development strategy with inclusive green development as the core content [42]. The research on inclusive green development has mainly focused on enriching the theoretical connotation, evaluation index construction, and measurement of inclusive green development, and a more mature evaluation index system has been formed [43,44,45,46]. With the increasing global carbon emissions, climate change has become one of the most urgent issues in the world, especially since the Paris Agreement established the long-term goal of “keeping the global average temperature rise within 2 °C within this century, and striving to control the temperature rise no more than 1.5 °C”. Many countries are actively exploring effective ways to synergize economic development and climate governance. However, the existing framework of inclusive green development focuses more on environmental pollutants such as emissions, wastewater, and solid waste, and the focus on carbon emissions and the energy consumption is somewhat lacking. As a result, ILCD, which integrates the concept of low-carbon development, has emerged.

There is no unified understanding of the concept of ILCD in the academic community. Xin et al. [47] see ILCD as a coupling of low-carbon development and inclusive growth. On the one hand, it should focus on the regional differences in the process of achieving the goal of “carbon peak and carbon neutral” and avoid the campaign-type emission reduction; on the other hand, it should take into account inter-regional equity and the sharing of results. According to Xiao et al. [48], ILCD is used to promote the overall carbon reduction target while taking into account the equity and sharing of regional economic development, and to achieve the Pareto improvement of overall low-carbon economic growth through flexible and diversified LCP instead of losing one region over another. Current research on ILCD has focused on the measurement of ILCD and its influencing factors. Xin et al. [47] constructed an economic growth–social inclusion–low-carbon development (ESC) analysis framework and an evaluation indicator system to characterize ILCD, and they found that renewable energy technology innovation significantly contributed to ILCD in both local and neighboring areas. Yang et al. [49] adopt the base difference entropy weight method to measure the comprehensive level of low-carbon inclusive growth of all provinces in China and established a link between ILCD and the connotation of high-quality development. Xiang et al. [50] used a two-way fixed effects model to empirically test the impact of digital economy development on ILCD, and they found that the digital economy has a significant inverted U-shaped impact on regional ILCD in China.

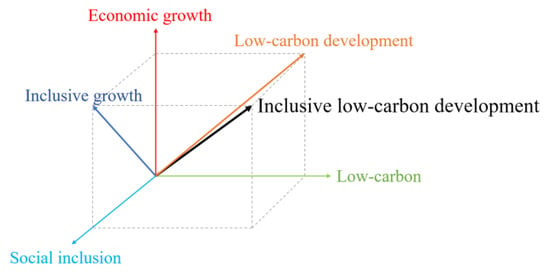

In summary, this paper argues that the conceptual content of ILCD should include the following three dimensions: (1) promoting economic development and improving residents’ welfare. Stable economic growth is not only a long-term requirement for regional development but also an important guarantee for improving residents’ welfare, reducing poverty, and improving their living standards in education, healthcare, and retirement. (2) Enhance social inclusion. In the development process, we should emphasize equal opportunities and fruit sharing, narrow the income distribution gap, while allowing vulnerable groups to be protected, and pay attention to the balance of all parties and social stability in economic growth. (3) Promote energy conservation and low-carbon development. Low-carbon development is an inherent requirement of sustainable development, and it should promote the construction of a “resource-saving” and “environment-friendly” society, improve energy efficiency while reducing carbon emissions [46], promote the innovation and application of low-carbon technologies, and advocate low-carbon lifestyles. At the same time, the three dimensions of ILCD need to be balanced with each other, and economic development, social inclusion, and low-carbon environmental protection should have “harmonization” rather than “fragmentation” to achieve sustainable social development [51]. The conceptual content of ILCD is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual content of ILCD.

2.3. LCP Synergy and ILCD

ILCD is a systemic activity spanning economic, social, resource, and environmental fields, and its government should emphasize the coordination of multiple elements, which makes it more necessary to strengthen LCP synergy among different governments and different government departments to coordinate to solve complex problems and achieve multidimensional goals. However, there is a paucity of literature that focuses on and analyzes in depth the impact of LCP synergy on ILCD, and no in-depth and systematic academic analysis and discussion on the impact of LCP synergy on ILCD has been conducted in the literature. Meanwhile, although there are research results that provide operational and quantitative ideas for the measurement of policy synergy and realize that policy synergy has an important impact on governance effectiveness [52,53], few studies have combined LCP synergy with ILCD and conducted empirical analysis using regional-level data and textual analysis methods.

This paper summarizes the impact mechanism of LCP synergy on ILCD in the following aspects: (1) LCP synergy extends and deepens government policy network connections by covering multiple subjects and strengthening sectoral coordination, which improves the quality of LCP formulation and implementation effectiveness and fosters a favorable external environment for regional ILCD. Generally speaking, the cooperation of more closely related government departments increases the overall density of the network, facilitates the interaction of heterogeneous resources, information flow, and consistent actions in the network, reduces the possibility of LCP conflicts with a better climate change governance system, and helps to implement LCP precisely. In terms of specific practices, multiple departments such as provincial ecological and environmental departments, development and reform commissions, industry and information departments, and finance departments can cooperate as policy synergists to introduce energy-saving and carbon-reducing measures, establish clear emission reduction targets and unified reward and punishment standards, set up scientific research projects on low-carbon technologies, collaborative innovation center construction, and other policies, and allocate special funds to effectively improve government administrative efficiency and the effectiveness of capital use. They can also coordinate and balance regional economic development and low-carbon governance as well as jointly promote ILCD in society. (2) LCP synergy provides a solid internal impetus for regional ILCD by enriching LCP tools, optimizing resource allocation, expanding and deepening social network connections, and increasing the frequency of communication and cooperation among carbon emission reduction subjects through government orders, market regulation, and public participation. The three types of LCP tools act on each dimension of ILCD from different perspectives. The administrative-command LCP tools clarify the governance mechanism of ILCD and build the institutional guarantee, which consolidates the foundation of ILCD; the market-regulation LCP tools can use the market-regulation mechanism to allocate various social resources efficiently and enhance the vitality of ILCD; the public participation LCP tools promote the public participation and supervision of the whole process of regional ILCD, which is conducive to improving the status of disadvantaged groups and promoting social equity, and broadening the breadth of ILCD. The three types of policy tools are coordinated to build a development pattern in which inclusive growth and low-carbon environmental protection are mutually reinforcing. In this process, policy synergy leads to a “relational contract” among social actors such as government departments, upstream and downstream enterprises, universities and research institutions, and the general public, which helps to expand social networks [54] and lay a good foundation for regional ILCD. (3) LCP synergy extends and deepens the network connection between government, enterprises, and the public in both bottom–up and top–down directions in the ILCD system. In governance practice, LCP synergy enables enterprises and the public to precisely and effectively connect with relevant government departments, and their actual needs can be accurately communicated from the bottom up, making LCP formulation more inclusive and targeted, taking into account the demands of all parties in society. LCP with consistent goals and complete tools are also easily accepted by enterprises, academic and research institutions, and the public, which helps to continuously improve STI policies and optimize the STI governance system.

3. Methodology and Data

3.1. Data Source and Sample Selection

In this paper, 30 provinces in China from 2010 to 2019 were selected as the research sample (Tibet, Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan in China are not included in the research sample of this paper due to large missing data). In terms of low carbon policy data collection, 1522 environmental protection policies issued by provincial administrative units from 2010 to 2019 were collected manually following the principles of relevance, authority and openness, and furthermore, policies with less relevance to low carbon development and energy conservation and consumption reduction were excluded, and 702 low carbon policy data were finally screened. On this basis, the textual analysis of low-carbon policies was conducted article by article, and the types and numbers of low-carbon policy-making subjects and policy measures were counted to calculate the annual low-carbon policy synergy of each province. Provincial economic, social and financial data are mainly obtained from the China Statistical Yearbook, CSMAR and Wind databases. Carbon emission data are mainly from the CEADs database.

3.2. Variable Definition

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

The core dependent variable of this paper is ILCD. In terms of measurement, ILCD has been measured mainly by constructing an evaluation index system, but the evaluation index system has problems of mixing process and outcome indicators, duplicating similar indicators, and difficulty in measuring some indicators, which cannot effectively reflect the relationship between the subsystems of each element. Therefore, this paper constructs the ILCD efficiency indicator as a proxy variable from the perspective of “input–output”, which refers to the relationship between the input factors of production activities and their economic output under the constraints of “inclusiveness” and “decarbonization”. The ILCD efficiency is the ratio between the input factors of production activities and their combined outputs of economic output, social welfare, and carbon reduction under the constraints of “inclusiveness” and “decarbonization”. Based on the connotation of ILCD, this paper constructs a scientific, systematic and data-accessible ILCD efficiency evaluation system based on the selection of indicators.

In terms of models, given that the super-efficient SBM (Slacks-Based Measure) model can effectively solve the problem in that the SBM model has no solution when multiple decision units are valid, it is more widely used in productivity measurement. Therefore, this paper adopts the super-efficient-non-desired Malmquist production index method (SBM-Malmquist) to measure the ILCD efficiency at the inter-provincial level in China. The input and output variables are as follows.

Inputs: Three indicators are selected: labor, capital, and energy. Among them, the number of employees at the end of the year is selected to characterize labor input, the stock of fixed asset investment is measured by the perpetual inventory method to characterize capital input, and electricity consumption is selected to characterize resource input.

Output: In this paper, three first-level indicators were selected from the perspective of desired output and non-desired output. Desired output mainly refers to the socioeconomic benefits brought by economic activities; referring to the study by Zhao et al. [55], a total of 6 specific indicators are included, among which GDP and local fiscal revenue characterize economic output, while total retail sales of social consumer goods, the number of health technicians per 10,000 people, pension insurance coverage rate, and a teacher–student ratio of general primary and secondary schools characterize economic activities from 4 aspects of resident consumption, health care, social security, and education services, respectively. The social welfare is brought about by economic activities. The undesired output includes both carbon emissions and social output. The higher the level of carbon emission, the lower the level of “low carbonization”. For social output, three specific indicators are selected: unemployment rate, the ratio of urban residents’ disposable income to rural residents’ disposable income, and the ratio of urban and rural residents’ consumption level, which represent the degree of equality of development opportunities, the degree of fairness of income distribution, and the degree of sharing of development results, respectively. The larger the above three indicators are, the less “inclusive” the economic activity is. Because of the specificity of the DEA model for the selection of indicators, the entropy value method is used to convert the data containing several secondary indicators.

3.2.2. Independent Variable

The core independent variables in this paper include: the synergy of LCP subjects, the synergy of LCP tools, and the overall synergy of LCP. Referring to the study of Zhao et al. [56], the specific measures are as follows.

The degree of the LCP subject synergy mainly refers to the degree of the synergy of the subjects enacting the policy. If the policy is jointly issued by more than one policy-making body, it is considered to have policy body synergy. Since the LCPs selected in this paper are all at the provincial level, the degree of policy subject synergy is mainly affected by the number of joint issuing departments, and the annual LCP subject synergy degree of each province is calculated as follows:

where t denotes the year, i denotes the province, K denotes the number of LCP issued in province i in year t, and k denotes the kth policy issued in province i in year t. PSk denotes the subjective synergy of the k policy, which is expressed by the number of joint issuing departments. Subi,t represents the annual LCP synergy of province i in year t by summing up all the policies issued in province i and taking the average value.

The degree of the LCP tool synergy instruments mainly refers to the degree of the synergy of the contents involved in the policy. This paper mainly adopts the classification method that has been widely used by scholars to classify LCP into command-and-control (setting energy-saving and carbon-reduction standards, low-carbon performance assessment of officials, no-coal zones, etc.), market-regulated (carbon emissions trading, energy-use rights trading, environmental protection tax, etc.) and public participation (carbon inclusion system, low-carbon travel, low-carbon transportation, etc.) based on different regulatory instruments. In this paper, we adopt the content analysis method, and if multiple instruments are involved in the content of this policy at the same time, it is considered that there is policy tools synergy. The annual LCP tool synergy degree of each province is calculated by the formula:

where PTk denotes the tool synergy of policy k. If the policy content contains only one of the three types of LCP: command-and-control, market regulation or public participation, the value is 1; if the policy content contains two of the three types of instruments, the value is 2; if all three types of instruments are involved, the value is 3. The synergy of all policy instruments enacted in province i in year t is summed up, and the average value is calculate. Then, Tooli,t denotes the annual synergy of LCP tools in province i in year t.

The synergy of LCP subjects and the synergy of LCP tools connect the government network and emission reduction subjects from the “bottom–up” and “top–down” directions, respectively. Based on this, the product of the synergy of LCP subjects and the synergy of LCP tools is used to measure the overall annual synergy of LCP in each province, which is calculated as follows.

3.2.3. Moderating Variables

In this paper, regional innovation capacity is selected as the moderating variable. The regional ILCD development is closely related to the local science and technology innovation capacity, and it cannot be separated from the government’s innovation incentive guiding behavior represented by financial allocation [57]. In this paper, the logarithm of annual R&D investment of provinces is used as the proxy variable of regional innovation capacity, which avoids the interference of differences in economic development levels among different provinces.

3.2.4. Control Variables

With reference to the existing literature, factors that may affect regional ILCD such as natural resource endowment, local government competition, cultural resources, and administrative regions are selected as control variables in this paper, and regional and year fixed effects are controlled for. The selection of indicators and their rationale are as follows: According to the theory of comparative advantage, natural resource endowment plays an important role in the dominant industries and development patterns of regions, and the concentration of resource-based industries may inhibit regional low-carbon development, which in turn affects regional ILCD, so this paper uses the ratio of the number of employees in extractive industries to the total population at the end of the year to measure it [58]. The “administrative centralization” and “fiscal decentralization” are important features of China’s governance model, and the fiscal capacity and competitiveness of local governments can affect the inclusive development of a region [59]. For this reason, this paper uses the fiscal balance ratio to measure this. Cultural resources refer to the spiritual and cultural contents that generate direct or indirect economic benefits for residents, and their richness and quality directly affect the development of the regional cultural economy and thus the regional ILCD, which is measured by the number of library books per 10,000 people in this paper [60]. The administrative area is controlled by drawing on the study of Cartier [61].

3.3. Model Construction

To test the effects of LCP subject synergy, LCP tools synergy, and LCP overall synergy on enterprise-independent innovation, respectively, a mixed panel model is constructed as follows.

where ILCD denotes ILCD efficiency, Sub, Tool, and Syn denote LCP subject synergy, LCP tools synergy, and LCP overall synergy, respectively, Control denotes the set of control variables, GINNOV denotes regional green innovation capacity, Syn × GINNOV is the key explanatory variable for the moderating effect, t denotes year, i denotes province, α, β, δ, and φ denote coefficients, and ε, γ, η, and θ denote standard errors. Meanwhile, to avoid the problem of possible heteroskedasticity among different industries and thus obtain more robust standard errors, the regressions are clustered at the inter-provincial level.

4. Empirical Results and Analysis

4.1. Baseline Regression

Table 1 reports the regression results of policy synergy and regional ILCD. Column (1) of Table 1 demonstrates the effect of LCP subject synergy on regional ILCD, and the regression results show that the coefficient is 0.0421 and is significant at the 5% level. This indicates that a high degree of synergy among LCP subjects extends and deepens the policy network connection from the government level, and the close network connection promotes the sharing and exchange of information among governance subjects, strengthens the degree of coordination among different departments, enhances the quality of LCP formulation and implementation effectiveness, and can provide clearer and more accurate path guidance for regional low-carbon development. At the same time, a good relationship among multiple subjects can better take into account the fairness of regional development opportunities, reduce the possibility of policy fluctuations, help reduce the risk of development and green innovation of economic subjects at all levels, and cultivate a good external environment for regional ILCD.

Table 1.

Regression results between LCP and ILCD.

Column (2) of Table 1 demonstrates the impact of synergy of the LCP tools on regional ILCD, and the regression results show that the coefficient is 0.0357 and significant at the 1% level. This indicates that LCP covering multiple policy instruments can lead various social organizations in various aspects, including government, market, and public, to carry out comprehensive and systematic cooperation, help all social sectors at the regional level to expand and deepen low-carbon network connections, promote the access to low-carbon resources by various subjects, and optimize the effective allocation and utilization of resources by government and enterprises. At the same time, the synergistic policy tools increase the frequency of communication and cooperation among various social sectors, enable the disadvantaged groups to be more protected in development, facilitate the region to maintain a balance in economic development, and provide sufficient internal motivation for regional ILCD.

Column (3) of Table 1 incorporates the overall policy synergy into the model with a coefficient of 0.0122 and is significant at the 1% level, which again confirms the promoting effect of policy synergy on ILCD. Specifically, policy synergy promotes regional ILCD through two mechanisms: synergy among policy subjects and synergy among policy instruments. On the one hand, the synergy among policy subjects builds government policy networks, uses close network connections to communicate the unified goals of various departments, improves the quality of LCP formulation and implementation effectiveness, and fosters a favorable external environment for emission reduction. On the other hand, the coordinated use of multiple policy tools leads various social organizations to communicate and cooperate, expanding and deepening the social network connection between government and enterprises and helping emission reduction subjects to effectively access and utilize various resources. At the same time, the bottom–up and top–down implementation and feedback mechanisms between the two networks contribute to the continuous optimization of the regional ILCD model and the positive cycle.

Column (4) of Table 1 demonstrates the moderating effect of regional innovation capacity on the main effect. The coefficient of Syn × GINNOV is 0.144 and is significant at the 5% level, indicating that high policy synergy promotes ILCD more strongly in provinces with stronger green innovation capacity. The possible reason is that a high degree of LCP synergy can provide regions with clear and explicit low-carbon innovation directions and a good external environment for innovation, while regions with stronger green innovation capacity can better access and effectively deploy and utilize innovation resources such as low carbon applied research, supporting carrier construction, and innovation talent pool in the region, thus contributing to the low-carbon development of the region. At the same time, with the promotion of policy synergy, regions with stronger innovation capacity can create more green jobs, enhance regional equality of opportunities, reduce social risks, and bring a certain buffer to the most vulnerable groups, thus significantly enhancing the inclusive growth of the region.

To further investigate the complementary effects of LCP subject synergy and LCP tools synergy on regional ILCD, this paper generates the 0–1 variable Sub_High to measure the high or low regional subject synergy with the median of LCP subject synergy as the benchmark, and Sub_High = 1 when the regional annual subject synergy is higher than the median, and vice versa. On the basis of this, if both regional policy subjects and policy tools are highly synergistic (i.e., both Sub_High and Tool_High are 1), then a dummy variable Sub_High and Tool_High with the value of 1 is generated. A total of four dummy variables are generated by this logic, corresponding to the four cases of high synergy between policy subjects and policy tools, the high synergy between policy subjects and low synergy between policy tools, the low synergy between policy subjects and high synergy between policy tools, and low synergy between policy subjects and policy tools. Meanwhile, the dummy variables are regressed with regional ILCD efficiency. The regression results are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Regression of LCP subject synergy; LCP tool synergy grouping.

As shown in column (1) of Table 2, the coefficients of both high subject synergy and high instrument synergy of regional LCP are positive and significant at the 1% level, indicating that both high subject and instrument synergy can effectively promote regional ILCD. In columns (2) and (3), the coefficients of high subject synergy and low tool synergy and low subject synergy and high tool synergy are insignificant and negatively significant, respectively, indicating that neither high subject synergy nor high tool synergy alone can promote enterprise independent innovation; neither one of them is indispensable. In column (4), the coefficients of low subject synergy and low instrument synergy are negative and significant at the 5% level, indicating that low subject synergy and low instrument synergy have a significant inhibitory effect on regional ILCD. This indicates that when the synergy of LCP subjects and instruments is both low, the lack of coordination among sectors not only leads to possible conflicts in LCP formulation, it also fails to provide clear policy guidelines for regional development, and the confusion and deviation in LCP formulation and implementation also increase the external environmental risks of participating actors, reduce the equity of opportunities, and are not conducive to social inclusion. At the same time, a single policy instrument cannot effectively coordinate and integrate the elemental advantages of government, market, and public, and it cannot meet the complex needs of regional ILCD, which hinders regional ILCD.

4.2. Robustness Test

To ensure reliable results, this paper adjusts the number of periods of the explanatory variables and controls for the effect of regional innovation capacity. To better clarify the causal relationship, the LCP process begins with the identification of the policy issue and ends with the evaluation and closure of the policy, which often has a long period. Therefore, this paper treats the periods of the explanatory variables with one and two lags in the robustness test. Table 3 demonstrates the regression results of adjusting the periods of the explanatory variables. The results show that the significance level and coefficient sign of LCP synergy are not significantly different from the benchmark regression, indicating that the results of the benchmark regression are robust.

Table 3.

Adjusting for the number of periods of the explanatory variables.

4.3. Heterogeneity Study

The impact of LCP synergy on regional ILCD will be influenced by regional characteristics, and the relationship between the two will vary depending on the location, development stage, and resource endowment of provinces. To further clarify the heterogeneity of the impact of LCP synergy on ILCD, this paper refers to the study of Liu et al. [62] and divides the study sample into resource-based and non-resource-based provinces based on regional resource endowment and leading industries to discuss the heterogeneous impact of different regional resource endowment.

Table 4 shows the analysis results of the heterogeneous grouping regressions. It can be seen that in non-resource-based regions, the impact of LCP subject synergy on regional ILCD is more significant, and the impact of LCP tools synergy is not significant, while the situation in resource-based regions shows the opposite. Possible reasons follow. On the one hand, non-resource-based regions tend to have better industrial structure advantages, and they are more willing to pay attention to LCP dynamics, deeply understand the in-depth meaning of LCP, and quickly respond to LCP to follow the national low-carbon development goals and strategic needs of sustainable development. As a result, they can then better carry out the implementation of LCP goals, which eventually significantly contribute to regional ILCD. Meanwhile, in resource-based regions, due to the high dependence on resource-based industries, ILCD faces greater difficulties and challenges. Here, the government often adopts a wait-and-see attitude toward LCP, and the willingness of various departments to respond to LCP is low, which makes the linkage and communication channels between departments obstructed, resulting in the low synergy of LCP. As a result, the implementation of LCP is more difficult, and the promotion effect of ILCD is not significant. On the other hand, because non-resource-based regions tend to be in a dominant position in China’s economic development, they take on more social responsibilities and diversified political goals, enjoy a higher political status, and are prone to obtain policy tilts. Meanwhile, the synergy of LCP tools can combine a variety of policy measures to help resource-based regions integrate the advantages of local natural resources, make up for the shortcomings of policy instruments, and better coordinate the relationship between resource development and low-carbon development, making the synergy of LCP tools in resource-based regions stronger in promoting ILCD than in non-resource-based regions.

Table 4.

Regression of regional resource endowment groupings.

5. Conclusions

This paper examines the manually collected LCP data of 30 Chinese provinces from 2010 to 2019 through a textual analysis method, measures the synergy of LCP subjects and the synergy of LCP tools, constructs an analytical framework based on the conceptual connotation of ILCD, measures the efficiency of ILCD at the inter-provincial level through a super-efficient SBM model, explores the LCP synergy on regional ILCD, revealing its mechanism of action, and further explores its regional heterogeneity. The main conclusions obtained are as follows.

- In general, LCP subject synergy, LCP tool synergy, and LCP overall synergy all effectively promote regional ILCD.

- Both LCP subject synergy and LCP tools synergy are indispensable. Policy synergy positively affects ILCD only when both policy subjects and policy instruments are highly synergistic, while ILCD is significantly weakened when both policy subjects and policy instruments are not synergistic.

- Regional innovation capacity plays a positive moderating role between ICP synergy and ILCD: the stronger the innovation capacity of provinces, the stronger the contribution of LCP synergy to ILCD.

- In non-resource-based regions, the effect of LCP subject synergy on regional ILCD is more significant, and the effect of LCP tools synergy is not significant, while the opposite is the case in resource-based regions.

6. Discussion

Based on the above findings, this paper provides the following references and insights for government policy-making and regional ILCD.

First, government departments should be “coordinated” rather than “fragmented”. On the one hand, horizontal cooperation among various departments should focus on structure, approach, and procedures. For example, the government can make structural arrangements for policy synergy by building a joint warfare command, a comprehensive coordination center, and other deliberative and coordinating bodies. It can also focus on special tasks led by the main departments through joint documents, working groups, joint meetings, etc., and it can use the communication and collaboration of experts from various departments to carry out systematic and comprehensive thinking, promote the formulation of policies from the perspective of the main synergy, reduce the possibility of policy conflicts, and improve the accuracy of policy implementation. In terms of procedures, we need to have procedural arrangements and technical means to solve “cross-border problems” and choose more appropriate agenda-setting and decision-making procedures to promote synergy. On the other hand, communication at all vertical levels needs to be timely and consistent. Local governments need to maintain consistency with central government policies, learn the requirements of central government policies, and improve the situation of “implementation blockage”.

Second, the organic combination of government and market should be promoted. The government should provide stable development expectations and reduce the risks and costs of participation in low-carbon development through macro-LCP. They should also use a variety of LCP tools, such as administrative command, market regulation, and public participation, to promote the effective clustering of various factors. Specifically, on the one hand, the government should continue to make use of administrative command-based tools to increase carbon emission reduction in key industries and provide subsidies or tax incentives for green technology innovation in order to promote the endogenous power of inclusive low-carbon development in the region. On the other hand, the government should increase the investment in both market-regulated and public participation LCP tools. Government procurement policies can be used to support the development of green technologies, encourage financial institutions to develop green financial products, and implement other measures to highlight the decisive role of the market in resource allocation, build a national unified carbon market, and smooth the national circulation. The orderly flow and effective allocation of resources can be guided by demand so that the innovative achievements of enterprises can be applied in the market. At the same time, regulatory effectiveness can be improved through measures such as optimization of the business environment, protection of intellectual property rights, and improvement of the basic system of the market system to reduce the risks of vulnerable groups in low-carbon development. In the formulation and implementation of LCP, the method of widely soliciting opinions on issues related to the policy process can be adopted to proactively understand the actual needs of enterprises and the public and complete the precise implementation of LCP.

Thirdly, local governments should establish a dynamic management mechanism that is “tailored to local conditions”, taking into account such characteristics as local natural resources and technological innovation capabilities. When formulating LCP, the current characteristics and inherent laws of regional industrial development should be fully considered, and policies should be categorized for resource-based and non-resource-based regions. The government departments should further implement the concept of sustainable development, change the habit of “waiting and watching” for LCP, actively respond to and actively implement various LCP, open up communication channels between departments, and coordinate the traditional resource-based industries with the emerging industries in the process of industrial transformation. For non-resource-based regions, they should strengthen the synergy of low-carbon instruments, take advantage of the advanced local industrial structure, and enhance the joint application of LCP tools to make up for the shortcomings of policy instruments, thereby promoting ILCD.

Finally, it is necessary to focus on the combination of LCP and science and technology innovation policies to strengthen the role of science and technology innovation in promoting ILCD. The research in this paper verifies the positive regulation of regional science and technology innovation capacity on ILCD. Government departments can use digital technology to build institutionalized information platforms and big data collaboration centers, and they can combine various policy tools on this basis so as to create a favorable external environment and empower a solid internal capacity for enterprise independent innovation and lead the region to follow the development path of innovation-empowered ILCD. The government should strengthen the orderly flow and effective allocation of innovation resources, guide the integration of science and technology innovation with low-carbon development, and help green innovation results be applied in the market [63]. As the main body of independent innovation, enterprises should not be passive but active, deepen their understanding of LCP through precise interpretation of current policies and active participation in government–enterprise dialogues, respond proactively to the government’s call for green science and technology innovation, target national goals and strategic needs, respond quickly to industrial policies, make full use of the high-quality policy environment under policy synergy, make full use of various favorable conditions, and firmly grasp the opportunity to communicate with other subjects. We make full use of the opportunities of communication and exchange with other subjects, strengthen the cultivation of knowledge absorption capacity in the expansion of enterprise social network, open the channel of transformation of green technology achievements, and make science and technology innovation truly serve ILCD.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Y.; data collection, X.Y. and L.X.; methodology, X.Y. and L.X.; software, X.Y. and H.S.; writing—original draft, X.Y.; writing—review and editing, X.Y. and L.X.; data curation, X.Y. and L.X.; supervision, X.Y. and H.S.; resources, X.Y. and H.S.; funding acquisition, H.S.; project administration, H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71963030), Xinjiang Social Science Foundation of China (21BJY050), Major Projects of Science and Technology Ministry of China (SQ2021xjkk01800), Autonomous Region Science and Technology Major Projects (2022A01003), Xinjiang University National Security Research Provincial-Ministry Collaborative Innovation Center Youth Program (22GAZXCO2), Autonomous Region Postgraduate Research Innovation Project (XJ2022G013), Xinjiang University 2022 “Outstanding Doctoral Student Innovation Project” (XJU2022BS016), and Xinjiang University 2022 “Outstanding Doctoral Student Innovation Project” (XJU2022BS012).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lin, B.; Li, Z. Towards world’s low carbon development: The role of clean energy. Appl. Energy 2022, 307, 118160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grainger, A.; Smith, G. The role of low carbon and high carbon materials in carbon neutrality science and carbon economics. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 49, 164–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xin, L.; Li, J. Environmental regulation and manufacturing carbon emissions in China: A new perspective on local government competition. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 36351–36375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianco, V.; Proskuryakova, L.; Starodubtseva, A. Energy inequality in the eurasian economic union. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 146, 111155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Xu, Y.; Lou, Y.; Chen, Y. Low carbon transition in a distributed energy system regulated by localized energy markets. Energy Policy 2018, 122, 474–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Wang, B.; Xu, W.; Cui, Q.; Chen, H. Could China’s longterm low-carbon energy transformation achieve the double dividend effect for the economy and environment? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 20128–20144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.; Ding, D.; Fang, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, J. How do fossil energy prices affect the stock prices of new energy companies? Evidence from Divisia energy price index in China’s market. Energy 2019, 169, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Hong, W. Benefits and costs of campaign-style environmental implementation: Evidence from China’s central environmental protection inspection system. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 45230–45247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Xu, Y.; Sun, W. Evaluating China’s pilot carbon Emission Trading Scheme: Collaborative reduction of carbon and air pollutants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 11357–11358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Chang, Y.C. The evolution of low-carbon development strategies in China. Energy 2014, 68, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tie, M.; Zhu, M. Interpreting low-carbon transition at the subnational level: Evidence from China using a Natural Language Processing approach. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 187, 106636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Gu, K.; Dong, F.; Sun, H. Does the low-carbon city pilot policy achieve the synergistic effect of pollution and carbon reduction? Energy Environ. 2022, 11, 27018–27029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Wu, H.; Yang, S.; Tu, Y.P. Effect of environmental regulation policy synergy on carbon emissions in China under consideration of the mediating role of industrial structure. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 322, 116053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Li, L.P.; Zhu, L.M. Industry-University-Research Collaboration and Firm Innovation: Research on Enterprise Postdoctoral Workstation. J. Renmin Univ. China 2020, 2, 97–113. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Guha, J.; Chakrabarti, B. Making e-government work: Adopting the network approach. Gov. Inf. Q. 2014, 31, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W.; Berkhout, F.; Van Vuuren, D.P. Bridging analytical approaches for low-carbon transitions. Nat. Clim. Change 2016, 6, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, N.; Strachan, N. Methodological review of UK and international low carbon scenarios. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 6056–6065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lah, O. Decarbonizing the transportation sector: Policy options, synergies, and institutions to deliver on a low-carbon stabilization pathway. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Energy Environ. 2017, 6, e257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggetti, M.; Trein, P. Multilevel governance and problem-solving: Towards a dynamic theory of multilevel policy-making? Public Adm. 2019, 97, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Liu, J.; Zhou, S. Synergy evaluation of China’s economy–energy low-carbon transition and its improvement strategy for structure optimization. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 65061–65076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Bai, X. Experimenting towards a low-carbon city: Policy evolution and nested structure of innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragkos, P.; Tasios, N.; Paroussos, L.; Capros, P.; Tsani, S. Energy system impacts and policy implications of the European Intended Nationally Determined Contribution and low-carbon pathway to 2050. Energy Policy 2017, 100, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Lin, B. Rethinking the choice of carbon tax and carbon trading in China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 159, 120187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bergh, J.C.J.M.; Castro, J.; Drews, S.; Exadaktylos, F.; Foramitti, J.; Klein, F.; Konc, T.; Savin, I. Designing an effective climate-policy mix: Accounting for instrument synergy. Clim. Policy 2021, 21, 745–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Brewer, G.A. Substitution and supplementation between co-functional policy instruments: Evidence from state budget stabilization practices. Public Adm. Rev. 2010, 70, 914–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nibedita, B.; Irfan, M. The role of energy efficiency and energy diversity in reducing carbon emissions: Empirical evidence on the long-run trade-off or synergy in emerging economies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 56938–56954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, K.; Uyarra, E.; Laranja, M. Reconceptualising the ‘policy mix’ for innovation. Res. Policy 2011, 40, 702–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Zhao, S.; Ding, X.; Xin, L. How the Pilot Low-Carbon City Policy Promotes Urban Green Innovation: Based on Temporal-Spatial Dual Perspectives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J. Impact of Environmental Regulation on Green Technological Innovation: Chinese Evidence of the Porter Effect. China Financ. Econ. Rev. 2019, 8, 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Ho, M.S.; Ma, R.; Teng, F. When carbon emission trading meets a regulated industry: Evidence from the electricity sector of China. J. Public Econ. 2021, 200, 104470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Li, Z.; Yang, C. Spatial Interaction Spillover Effects between Digital Financial Technology and Urban Ecological Efficiency in China: An Empirical Study Based on Spatial Simultaneous Equations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitmarsh, L.; Seyfang, G.; O’Neill, S. Public engagement with carbon and climate change: To what extent is the public ‘carbon capable’? Glob. Environ. Change 2011, 21, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, T.R.; Stephens, J.C.; Wilson, E.J. Public perception of and engagement with emerging low-carbon energy technologies: A literature review. MRS Energy Sustain. 2015, 2, E11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asian Development Bank. Strategy 2020: The Long-Term Strategic Framework of the Asian Development Bank (2008–2020); Asian Development Bank: Mandaluyong, Philippines, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, T.; Qiu, W.; Li, J.; Hao, X. The impact of environmental regulation efficiency loss on inclusive growth: Evidence from China. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 268, 110700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, T.; Li, J. The effect of environmental regulation intensity deviation on China’s inclusive growth. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 34158–34171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S. Poverty Reduction Strategies—Lessons from the Asian and Pacific Region on Inclusive Development; Asian Development Bank: Mandaluyong, Philippines, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, I.; Zhuang, J. Inclusive Growth toward a Prosperous Asia: Policy Implications (No. 97); ERD working paper series; Asian Development Bank: Mandaluyong, Philippines, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Aoyagi, C.; Ganelli, G. Asia’s quest for inclusive growth revisited. J. Asian Econ. 2015, 40, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeleye, B.N.; Adedoyin, F.; Nathaniel, S. The criticality of ICT-trade nexus on economic and inclusive growth. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2021, 27, 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, S.; Sandhu, S.C.; Wachirapunyanont, R. Inclusive Green Growth Index: A New Benchmark for Quality of Growth; Asian Development Bank: Mandaluyong, Philippines, 2018; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11540/8988 (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Albagoury, S. Inclusive Green Growth in Africa: Ethiopia Case Study; University Library of Munich: Munich, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Ding, W.; Yang, Z.; Yang, G.; Du, J. Measuring China’s regional inclusive green growth. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 713, 136367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, Z.; Chen, H. and research on the level of inclusive green growth in Asia-Pacific region. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J. The dynamic coupling nexus among inclusive green growth: A case study in Anhui province, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 49194–49213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Xu, Y. Evaluation of China’s pilot low-carbon city program: A perspective of industrial carbon emission efficiency. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2022, 13, 101446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, L.; Sun, H.; Xia, X. Renewable energy technology innovation and inclusive low-carbon development from the perspective of spatiotemporal consistency. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 20490–20513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.Y.; Sun, H.; Wang, H.; Xin, L. From “pilot” to “diffusion”: Analysis of inclusive low-carbon growth effect of low-carbon city pilot policy. Ind. Econ. Res. 2022, 3, 28–40. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Xiang, X.; Deng, F.; Wang, F. Towards high-quality development: How does digital economy impact low-carbon inclusive development?: Mechanism and path. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 41700–41725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, X.; Yang, G.; Sun, H. The impact of the digital economy on low-carbon, inclusive growth: Promoting or restraining. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, L.; Sun, H.; Xia, X. Spatial–temporal differentiation and dynamic spatial convergence of inclusive low-carbon development: Evidence from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 5197–5215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candel, J.J.; Biesbroek, R. Toward a processual understanding of policy integration. Policy Sci. 2016, 49, 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Li, T.; Albitar, K. Does Energy Efficiency Affect Ambient PM2.5? The Moderating Role of Energy Investment. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 707751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, R. Alliances and networks. Strateg. Manag. J. 1998, 19, 293–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Gao, X.T.; Liu, Y.X.; Han, Z.L. Evolution Characteristics of Spatial Correlation Network of Inclusive Green Efficiency in China. Econ. Geogr. 2021, 9, 69–78+90. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Chi, X.; Sun, Z.J. Synergy or Fragment: The Influence of Policy Synergy on Firm Independent Innovation. China Ind. Econ. 2022, 8, 175–192. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Zhang, L.; Tarbert, H.; Yan, Z. Analysis on spatio-temporal characteristics and influencing factors of industrial green innovation efficiency—From the perspective of innovation value chain. Sustainability 2021, 14, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Su, X.; Ran, Q.; Ren, S.; Chen, B.; Wang, W.; Wang, J. Assessing the impact of energy internet and energy misallocation on carbon emissions: New insights from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 23436–23460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Wang, J.; Cao, J.; Ren, S.; Ran, Q.; Wu, H. The spatial spillover effect of urban sprawl and fiscal decentralization on air pollution: Evidence from 269 cities in China. Empir. Econ. 2021, 63, 847–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Meng, X.; Wang, Y.; Guo, J.; Feng, F. Study of the spatial divergence features and motivating factors of energy green consumption levels in “2 + 26” cities. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 19776–19789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cartier, C. What’s territorial about China? From geopolitical narratives to the ‘administrative area economy’. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2013, 54, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xin, L.; Li, J.; Sun, H. The Impact of Renewable Energy Technology Innovation on Industrial Green Transformation and Upgrading: Beggar Thy Neighbor or Benefiting Thy Neighbor. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Cao, Y.; Feng, C.; Guo, K.; Zhang, J. How do heterogeneous R&D investments affect China’s green productivity: Revisiting the Porter hypothesis. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 825, 154090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).