Abstract

Plant resources have been used by humans for their wellbeing for ages. Tribal communities live in far flung areas in close proximity with forests and have a rich cultural heritage and traditional knowledge of forest resources. The present study was carried out in the Rajouri district of Jammu and Kashmir to document the traditional knowledge of plant usage and local perception towards biodiversity conservation. A total of 86 informants were selected through non-probability sampling using a convenience sampling method based on easy access, availability and relevance of informants. During the present study, a total of 92 plant species belonging to 85 genera and 57 families were recorded. Fabaceae and Rosaceae were found to be dominant families. In terms of growth forms, herbaceous species were dominant, followed by trees. Leaves were the most common parts used, followed by fruits. These plant species are used for different purposes such as medicine, edibles, fodder and dye making. A number of plant species were found to be multipurpose in use. Most of the documented plant species are collected by local people from the wild. Local people perceived that the populations of many species, such as Dolomiaea costus, Dioscorea deltoidea and Dolomiaea macrocephala, have declined in recent decades. Climate change, urbanization, deforestation, pollution, overexploitation and species invasion are some of the major threats to biodiversity perceived by the local people. Therefore, the establishment of protected areas and cultivation of wild species are recommended to safeguard forest wealth of the area. Furthermore, mass awareness and cooperation-building programs are highly recommended so that locals can enthusiastically participate in conservation and management programs.

1. Introduction

Large proportions of people living in different parts of the world, including India, are nature-dependent and fulfill their daily needs of food, fodder and medicine from their surroundings []. Natural bioresources such as forests play a significant role in the livelihood of indigenous or tribal communities []. Indigenous people, who have long-standing traditions of resource utilization, frequently have an extensive understanding of how complex natural systems behave in their own localities. This information has been built up over many years of observations that have passed down from generation to generation []. A community’s traditional knowledge is crucial for identifying beneficial plants, as such plants have frequently been examined by generations of indigenous people [,]. Therefore, traditional knowledge of utilization of bioresources or ethnobotanical knowledge is intrinsic and stems from a long-established repository of wisdom and knowledge. Indigenous knowledge of biodiversity conservation has been recognized by a large group of scholars, practitioners, policy makers and even ethnic communities. This wide recognition of indigenous knowledge is an optimistic advancement in current intricate global scenarios []. Although the indigenous people are mostly illiterate, they have a rich legacy of social and cultural rituals and a constructive opinion of biodiversity conservation and management []. Numerous factors, including age and gender, as well as factors such as education, occupation and psychological factors, have an impact on traditional knowledge; however, age and gender are the most frequently investigated for their impact on traditional knowledge []. The precise documentation of this knowledge is vital, as it is dynamic and changes with time, age, culture and resources. Furthermore, this treasure of information now remains largely restricted to elders []. Currently, there is a shift away from just documenting ethnobotanical data to a more practical approach that acknowledges and emphasizes the necessity of conservation and sustainable use of plant resources []. One of the most pressing concerns faced by nations and the world is the loss of biodiversity and the need for conservation for future generations []. Indigenous people play a significant role in biodiversity conservation all over the world because of their close links to flora and fauna []. For instance, the traditional forest management practices of the Chinese Yi community are deeply connected with their religious practices, traditions, folklore and burial rituals []. Thus, traditional practices strive to balance ecosystem services, as they link culture and nature []. The application of indigenous knowledge practices has considerably enhanced biodiversity conservation around the globe. This has improved ecosystem services, thereby benefitting different stakeholders including forest owners, timber wood industrialists and visitors, as well as religious and environmental groups []. Examining traditional knowledge can aid in ensuring that forest resources continue to sustainably supply a range of products and services. Conventional methods of conserving wildlife and forest resources, such as fencing off protected areas or fining trespassers, frequently lead to conflicts between locals and the authorities in charge of managing wildlife and forests, especially when the former are reliant on forest products and services []. The traditional knowledge method is superior to conventional strategies because it prevents such conflicts and uses fewer state resources to enforce laws to protect wildlife and forest resources. However, traditional knowledge has been lost over time because it is typically transmitted orally through historical tales, legends, myths and songs []. The 1992 Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit firmly recognized the relevance of indigenous knowledge in the protection of biodiversity (Article 8j) and encouraged its implementation as a new standard in protecting the environment []. Studies have revealed that local people often develop more positive perceptions and attitudes when they receive more benefits from the surrounding forests. Community involvement leads to solid partnerships and high response rates, resulting in effective and successful biodiversity conservation [].

The Indian Himalayan region (IHR), which spans up to 4, 19, 873 km2 and stretches from the trans-northwest to the eastern Himalaya, is blessed with a variety of physiography, climate, soil and biological diversity. It has an extensive altitudinal range (300–8000 m amsl) and great diversity of ecosystems, which support a wide range of microclimates and niches for flora and fauna []. Alpine, temperate subalpine and subtropical plant groups make up the vegetation along an altitudinal gradient. The region harbors approximately 18,440 plant species, of which 25.3% are endemic [,]. Furthermore, it is home to several ethnic tribal groups, such as the Gujjars, Bakerwals, Paharis and Bhotiyas, which have rich and diverse customs and traditional knowledge. These tribes or Himalayan races inhabit remote areas and depend on local bioresources for survival. The traditional use of plant species has been a crucial component of social, cultural and religious aspects of these ethnic communities []. The indigenous knowledge of the local communities in the Rajouri district of Jammu and Kashmir, India, which is located in the northwestern Himalaya, has been the subject of various studies [,,,,]. However, these studies were primarily focused on the documentation of traditional medicinal plants and their uses. A considerable indigenous knowledge database still exists within the ethnic groups of the study area, calling for its exploration and documentation. Furthermore, no study has been carried out on local perceptions regarding the conservation and management of plant resources in the area.

Against this backdrop, the present study was conducted to achieve the following objectives:

- Exploration and documentation of the plant species used by local communities of the Rajouri district to meet their day-to-day requirements;

- Determination of the perception of local people towards conservation and management of biodiversity in the area.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

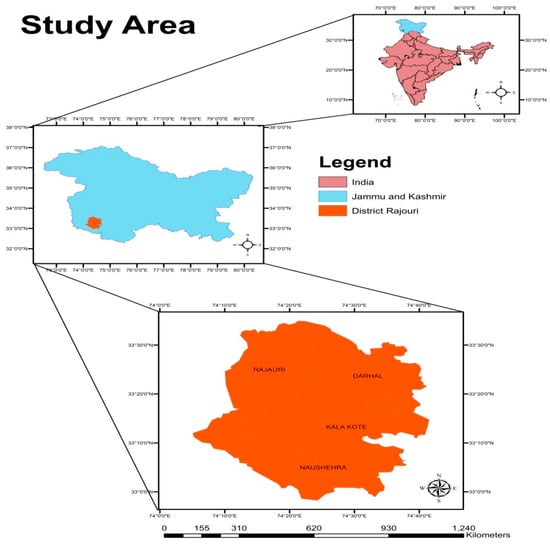

Rajouri is a district of the Jammu region in the union territory of Jammu and Kashmir, India. Total area of the district is 2630 km2, with geographic coordinates of 70–74°4′ E longitude and 32°58′–33°35′ N latitude (Figure 1). It is overshadowed by Poonch in the north, Jammu in the south, Reasi in the east and Kashmir in the west. Rajouri represents remarkable diversity with respect to altitude, topography and edaphic factors. The terrain is largely hilly and montane in nature. In terms of climate and vegetation, the district is broadly divided into four zones, viz., subtropical, temperate, subalpine and alpine zones, each representing remarkable diversity in term of its flora and fauna. People from different linguistic groups reside within the region; however, the nomadic Gujjar and Bakerwal tribes make up the majority of the population. Originally and ethnically, both these tribes were pastoral nomads and speak the same language, i.e., “Gojri” and differ only in the type of animal rearing and nature of migration. Gujjars rear buffaloes, possess small pieces of land and houses and are semi-nomadic, whereas Bakerwals are completely nomadic, rear flocks of sheep and goats and are always migratory. Besides these two tribes, the Pahari community makes up a significant portion of the district’s population, with a fraction of the population accounted for by the Kashmiri community. These communities are dependent on the neighboring forests for their livelihood and day-to-day requirements. Agriculture and animal husbandry are the main occupations of the majority of the population of the area. Traditional knowledge is dispersed among the general populace and is transmitted orally to succeeding generations [,].

Figure 1.

Map showing the location of the study area.

2.2. Survey and Sampling

Field surveys and sampling were carried out from May to September 2022. A total of 86 informants were selected through non-probability sampling using a convenience sampling method based on easy access, availability and relevance of informants according to Henrich et al. []. Open-ended semi-structured questionnaires were used for data collection. Furthermore, interviews and group discussions were organized in which local inhabitants were invited to participate. Prior to conducting interviews and distributing questionnaires, oral consent was obtained from all the informants. The questionnaire was divided into three parts. The first part of the questionnaire included questions about demographic features of the informants, such as age, gender, level of education and ethnicity. The second part consisted of questions regarding the utilization of plant bioresources by the local informants to generate information on the local names of plants, their life forms and habitats, part(s) used, purpose and methods of use. In the third part of the questionnaire, questions regarding the perception of locals towards biodiversity conservation and management were included.

Field visits were carried out, and local guides were hired for collection of the enlisted plant species. Relevant information such as plant habit, habitat and date of collection, was recorded in a field notebook. Furthermore, fresh samples of the plant species were collected and later mounted on herbarium sheets following standard herbarium practices []. All the plant samples mounted on herbarium sheets were identified up to the species level using local and regional floras [,,,,]. The latest botanical nomenclature and families were retrieved from Plants of the World Online (https://powo.science.kew.org, accessed on 10 October 2022). The identified and well-labeled specimens were deposited in the Herbarium, Centre for Biodiversity Studies, Baba Ghulam Shah Badshah University, Rajouri, Jammu and Kashmir, India. A systematic review of relevant literature was carried out to assess the threat status of the documented plant species.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Demographic Profile of the Informants

A proportion of 63.96% of informants were male, and 36.04% were female. Based on age, the informants were divided into four categories: 25–35 years (17.44%), 36–45 years (25.60%), 46–55 years (31.39%) and 55–65 years (26.74%). Concerning education level, 25.58% were illiterate, 20.48% had attended school up to the primary level, 23.25% up to the middle school level, 19.76% up to the secondary level and 11.62% up to higher secondary level or above. Most of the informants belonged to the Gujjar community (43.02%), followed by the Bakerwal community (25.58%) and the Pahari community (19.76%), and rest were from the Kashmiri community (11.62%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic profile of informants.

3.2. Diversity of Useful Plant Species

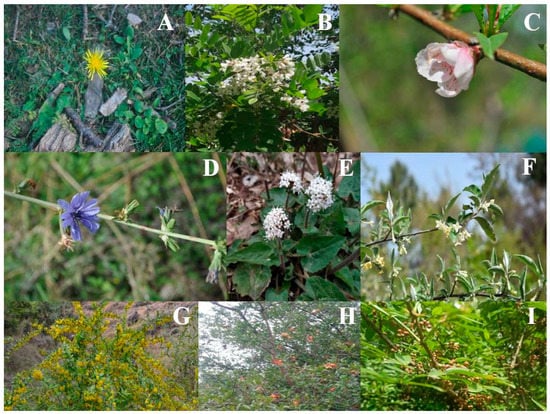

In the present study, a total of 92 plant species belonging to 85 genera and 57 families were recorded (Table S1). Some of the economically important plant species are presented in Figure 2. The most dominant families were Fabaceae and Rosaceae, with seven species each, followed by Asteraceae, with five species, and Euphorbiaceae, Rutaceae and Solanaceae (three species each). Thirteen families were represented by two species each, and thirty-eight families were represented by a single plant species. The dominance of these plant families may be attributed to their extensive distribution and abundance in the study area []. Furthermore, the presence of nutraceutical and other bioactive compounds may contribute to their dominance []. The plants of the Fabaceae family are able to grow in nutrient-deficient soils and can be found in abundance in local forests []. The dominance of these plant families among ethnic communities have also been reported in previous studies [,,,,,].

Figure 2.

Some of the economically important plant species in the regions. (A) Taraxacum sect. Taraxacum; (B) Robinia pseudoacacia; (C) Prunus persica; (D) Cichorium intybus; (E) Valeriana jatamansi; (F) Elaeagnus umbellata; (G) Berberis lycium; (H) Punica granatum; (I) Zanthoxylum armatum.

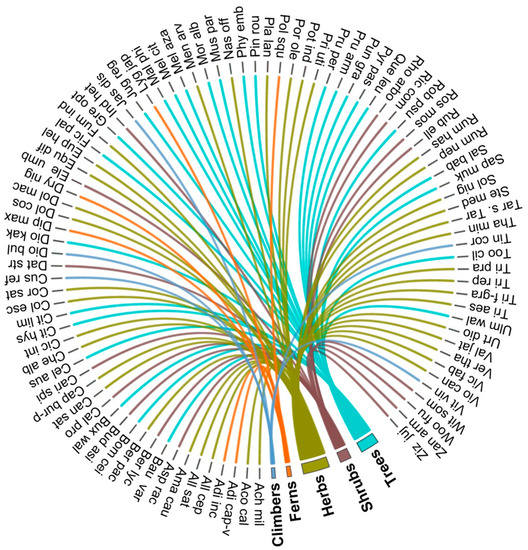

Based on the growth forms of the documented plant species, herbaceous forms were most dominant (38 species), followed by trees (27 species), shrubs (16 species), ferns (6 species) and climbers (5 species) (Figure 3). The dominance of herbaceous species may be due to their abundance, ease of collection and method of use (24,33,37). The results of the present study are comparable with those of related studies in which herbaceous species have been documented as the dominant species used by local people [,,,,].

Figure 3.

Growth forms of documented plant species.

The majority of the documented species (73 species) grow in self-maintaining populations in natural or semi-natural ecosystems (i.e., wild). These wild species have been found to grow in a variety of habitats, such as woodlands, grasslands, shrublands, roadsides and agricultural fields. Plant species such as Dolomiaea costus and Dolomiaea macrocephala grow in alpine areas, whereas plant species such as Diplazium maximum, Adiantum capillus-veneris and Adiantum incisum grow in shady, moist habitats. Nine plant species were reported to be cultivated by local people in their gardens and agricultural and farm lands. Furthermore, some wild species, such as Amaranthus caudatus, Ficus palmata, Grewia optiva, Morus alba, Prunus persica, etc., are also cultivated by the local people and grow both in the wild and in domestic settings (Table S1). The dominance of wild plant species in traditional systems has also been reported in other relevant studies [,]. Overharvesting of these plant species from the wild has put tremendous pressure on their natural populations; therefore, there is an urgent need to conserve such valuable plant species []. The most urgently needed aspects of the integrative conservation of these plant species may be the cultivation or, more broadly, the preservation of their germplasm. It is also important to retrieve knowledge about plants and their properties possessed by quickly disappearing cultures [].

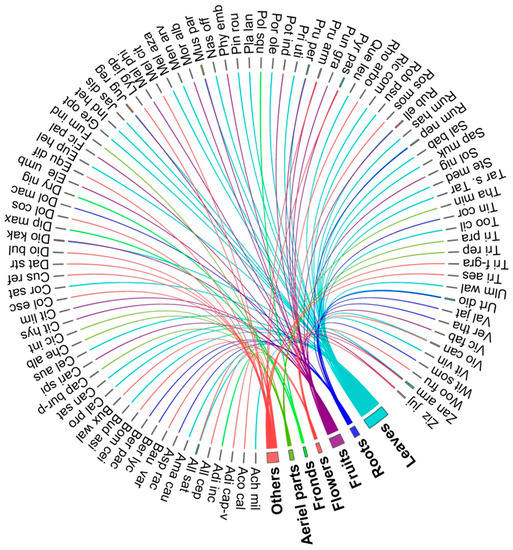

3.3. Utilization Pattern

Indigenous people make use of a variety of plant components, including leaves, roots, stems, branches, flowers, fruits, seeds, fronds, stems, bark and sometimes whole plants, depending on inherited knowledge and the availability of the plants and plant parts to the local community. In the present study, the most common plant parts used were leaves (42.39%), followed by fruits (22.82%), roots (10.86%), aerial parts (7.60%), flowers (6.52%), fronds (4.34%), rhizome (4.34%), seeds (4.34%), whole plants (3.26%), stem (2.17%), bulbs (2.17%), bark (1.08%), branches (1.08%), corms (1.08%) and wood (1.08%) (Figure 4). According to researchers, leaves are frequently employed in traditional usages as medicine, food and fodder because they are easy to harvest; additionally, because they are actively photosynthesizing, they contain more secondary metabolites than any other part of the plant [,]. Furthermore, plucking of leaves causes no harm to the parent plant. Other related studies have also reported leaves as the dominant parts used in traditional systems [,,,].

Figure 4.

Parts of documented plant species used by local people.

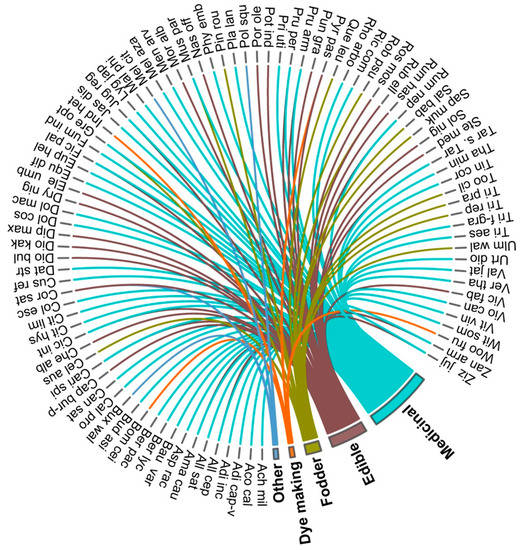

Based on the utilization pattern of the documented plant species, fifty-six species were found to be used for medicinal purposes, and thirty-two species were reported as edible, with thirteen species used as fodder, four species for dye making and four species for other purposes (ornamentals, spices and wood craft) (Figure 5). Of these species, seventeen plant species were reported to be of multipurpose value. The findings of this study are in line with those of other relevant studies in which it has been reported that plants are used mainly for medicinal, edible, fodder and dye-making purposes by local inhabitants [,]. Plant parts or the whole plant may be utilized after being prepared in a variety of forms, such as paste, powder, cooked, decoction, etc., while some are utilized in raw form (Table S1). Similar methods of preparation have been reported by other researchers in their studies [,].

Figure 5.

Uses of the documented plant species.

3.4. Conservation Status of the Plant Species

Over the decades, a large number of species have become threatened due to various anthropogenic activities, such as habitat loss or modification, overharvesting of commercially valuable plants, unrestricted animal grazing and unsustainable development activities [,]. Among the 74 plant species growing in the wild reported in the present study, nine plant species have been categorized under different threat categories by various researchers in Jammu and Kashmir (Table 2). Furthermore, one species, Dolomiaea costus, is critically endangered, and two other species, Acorus calamus and Ziziphus jujube, are categorized as of least concern according to the IUCN []. The threatened species include some alpine species growing at higher altitudes in specific pockets, such as Dolomiaea costus and Dolomiaea macrocephala. Some other threatened plant species have specific habitat preferences (Acorus calamus, Dioscorea deltoidea and Valeriana jatamansi), growing in one or a few specific types of habitats, and therefore have narrow ecological amplitudes. Furthermore, some of the reported plant species that are facing considerable anthropogenic pressures (Buxus wallichiana) or have narrow distributions (Elaeagnus umbellata) have not been assessed for their threat categorization to date.

Table 2.

Threat status of some of the documented plant species.

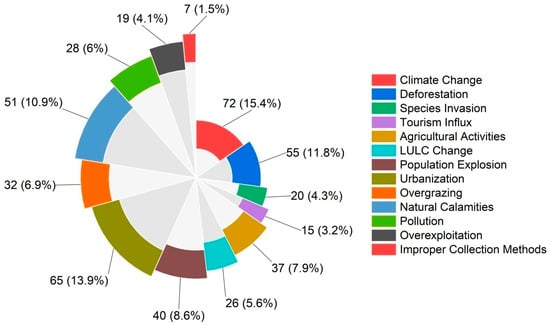

3.5. Local Perception towards Biodiversity Conservation and Management

In the present study, when respondents were asked how important the forests are, all the respondents agreed that the surrounding forests play an important role in their day-to-day life. Informants regarded the plants growing in the wild as equally important as cultivated plants and as an important source of their basic needs, such as wild edibles, fuel wood, fodder, medicines and dyes. Moreover, some of the informants also regarded wild plants such as Buxus wallichiana as an important source of their income. Wani et al. [] also reported that Buxus wallichiana generates an economic value of about INR 84,000 per annum per family. Most of the informants were of the view that the populations of some important plants, especially the medicinal species, such as Dolomiaea costus, Dolomiaea macrocephala and Valeriana jatamansi, have decreased to a great extent. The informants considered climate change, population explosion, the Mughal Road project, natural disasters, pollution, overgrazing, deforestation and urbanization as the major threats to biodiversity (Figure 6). Furthermore, when the informants were asked how important the conservation of biodiversity is, they revealed that the conservation of bioresources is directly linked with their present and future generations. The majority of the informants were ready to participate in biodiversity conservation and management programs. However, a portion of informants were reluctant about these programs and feared that under such programs, collection of resources from the wild will be prohibited, which will influence their livelihood. Insufficient progress in reducing the loss of biodiversity throughout the Indian Himalayan region may be due to the mismatch in conservation of species and ecosystems planned and valued by conservationists and marginalized communities, along with their dependence on these high-value ecosystems for diverse subsistence requirements [,]. Indigenous people using a resource have an understanding of how it can be maintained, and sustainable development cannot be achieved unless these resource users are active participants in management programs. Involving local representatives in planning and decision making is equally crucial [], and in order to ensure the sustainable use and management of natural resources, there is an increasing interest in the traditional ecological knowledge systems and practices of indigenous communities [].Combining traditional and scientific knowledge is essential and necessitates collaboration between regional researchers and native communities []. In order to effectively engage and move away from the indigenous vs. scientific paradigm and work towards greater autonomy for indigenous people, it is crucial to effectively put indigenous knowledge into practice []. Therefore, management practices need to be promoted that emphasizes the need for local participation in order to strike a balance between biodiversity conservation and meeting the basic requirements of such resource-dependent communities [].

Figure 6.

Threats to biodiversity perceived by the local people (in terms of total mentions) of the study area.

4. Practical Implications and Limitations of the Study

The present study provides a thorough description of the plant species that are used by the local people of the study area for a variety of purposes, including food, fodder and medicine. This information will be helpful in developing cost-effective and reliable medicines, nutritional products, dyes, etc. The study will also be extremely helpful for researchers and workers studying plant systems in a variety of domains, such as phytochemistry, conservation and management, taxonomy, plant breeding, and ecology and environment. Furthermore, as stakeholder involvement is widely advocated for and considered one of the fundamental prerequisites for the achievement of sustainable development [], the findings of the present study will be helpful for cultural survival and biodiversity conservation and will contribute to the formulation of practices and policies for sustainable development and effective resource management in the region. However, the inclusion of only 86 respondents in the present study may have resulted in biasing of the sample. Therefore, in the future, comprehensive investigations need to be undertaken in which an ample number of informants is interviewed so that more precise information can be documented. The participation of a large number of people can also provide a wider and clearer picture of perceptions of regarding conservation and management of biodiversity in the area.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Rajouri district has a rich diversity of medicinal, edible and fodder plant species that are used by the locals for their basic requirements, as well as in traditional healthcare systems. Although these people are mostly illiterate, they have a rich social and cultural diversity and possess an immense knowledge of plant resources. Populations of various valuable plant species have declined over the years in the study area, as perceived by the local people. Major threats to biodiversity perceived by the locals include climate change and urbanization. The locals also perceived that there is a dire need to preserve these valuable plant species from further destruction in order to avoid their extinction from the region. However, the locals were reluctant to participate in biodiversity conservation and management programs, as they fear that through such programs, there will be a prohibition on the collection and utilization of such plant species, which, in turn, will negatively affect their livelihood. Based on the results of the present study, we recommend that biodiversity-rich habitats be identified and that protected areas be established in the region. Cultivation of wild plant species should be promoted among the masses in order to safeguard plant resources, as well as the livelihoods of locals. Additionally, the development of horticulture and wood craft trades (B. wallichiana) could help to generate amicable cooperation between resource users and policy makers in the region. More research should be carried out to identify and to prioritize plant species, habitats and plant communities for conservation and management. Furthermore, scientific collection methods should be disseminated among the masses. However, the livelihood of the locals should be prioritized and safeguarded in order to build confidence and trust among the local people so that collaborative conservation and management programs can be successfully initiated.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su15043198/s1, Table S1. Plant species documented in present study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.R. and Z.A.W.; methodology, Q.R. and Z.A.W.; software, Q.R. and Z.A.W.; validation, Q.R. and Z.A.W.; formal analysis, Q.R. and Z.A.W.; investigation, Q.R.; resources, M.H. and S.P.; data curation, Q.R. and Z.A.W.; writing—original draft, Q.R. and Z.A.W.; visualization, Q.R. and Z.A.W.; supervision, M.H. and S.P.; project administration, M.H. and S.P.; funding acquisition, S.S.; review and editing, Q.R., Z.A.W., M.H., S.P., A.A.S., S.S. and S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University for funding this work through the Small Groups Project under grant number R.G.P.1/360/43.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Oral consent was obtained from the respondents prior to conducting interviews.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the local people of district Rajouri for their participation and sharing of information. The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University for funding this work through the Small Groups Project under grant number R.G.P.1/360/43.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gadgil, M.; Berkes, F.; Folke, C. Indigenousknowledge: From local to global. Ambio 2021, 50, 967–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asif, M.; Haq, S.M.; Yaqoob, U.; Hassan, M.; Jan, H.A. A preliminary study on the ethno-traditional medicinal plantusage in Tehsil “Karnah” of District Kupwara (Jammu and Kashmir) India. Ethno. Res. Appl. 2021, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gadgil, M.; Berkes, F.; Folke, C. Indigenous knowledge for biodiversity conservation. Ambio 1993, 22, 151–156. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, P.A. Will tribal knowledge survive the millennium? Science 2000, 287, 44–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, M.O.; Farah, K.O.; Ekaya, W.N. Indigenous knowledge: The basis of the Maasai Ethnoveterinary diagnostic skills. J. Human Ecol. 2004, 16, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battiste, M.; Youngblood, J. Protecting Indigenous Knowledge and Heritage: A Global Challenge; ubcPress: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen, H.; Qaseem, M.F.; Amjad, M.S.; Bruschi, P. Exploration of ethno-medicinal knowledge among rural communities of Pearl Valley; Rawalakot, District Poonch Azad Jammu and Kashmir. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjad, M.S.; Qaeem, M.F.; Ahmad, I.; Khan, S.U.; Chaudhari, S.K.; Malik, N.Z.; Shaheen, H.; Khan, A.M. Descriptive study of plant resources in the context of ethnomedicinal relevance of indigenous flora: A case study from Toli Peer National Park, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishtiaq, M.; Maqbool, M.; Hussain, T.; Shah, A. Role of indigenous knowledge in biodiversity conservation of an area: A case study on tree ethnobotany of Soona Valley, District Bhimber Azad Kashmir, Pakistan. Pak. J. Bot. 2013, 45, 245–256. [Google Scholar]

- Farooquee, N.A.; Majila, B.S.; Kala, C.P. Indigenous knowledge system and sustainable management of natural resources in high altitude society in Kamaun Himalaya. Ind. J. Hum. Ecol. 2004, 16, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavhura, E.; Mushure, S. Forest and wild life resource–conservation efforts based on indigenous knowledge: The case of Nharira community in Chikomba district, Zimbabwe. Policy Econ. 2019, 105, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinlong, L.; Renhua, Z.; Qiaoyun, Z. Traditional forest knowledge of the Yi people confronting policy reform and social changes in Yunnan province of China. Policy Econ. 2012, 22, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, H.; Gonzalez, N.C. Bridging knowledge divides: The case of indigenous ontologies of territoriality and REDD+. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 100, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.N.; Hossain, M.M.; Chen, Y.; Siriwong, W.; Boonyanuphap, J. Stakeholders’ perception on indigenous community- based management of village common forests in Chittagong hilltracts, Bangladesh. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 100, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier-Salem, M.C.; Roussel, B. Patrimonies et saviors naturalists locaux. In Development Durable? Doctrine, Pratiques, Evaluations; Martin, J.Y., Ed.; Institut de Recherche pour le Développement: Paris, France, 2002; pp. 125–142. [Google Scholar]

- Bajracharya, S.B.; Furley, P.A.; Newton, A.C. Impacts of community-based conservation on local communities in the Annapurna Conservation Area, Nepal. Biod. Cons. 2006, 15, 2765–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samant, S.S.; Dhar, U.; Palni, L.M.S. Medicinal Plants of Indian Himalaya: Diversity, Distribution, Potential Values; GyanodayaPrakashan: Nainital, India, 1998; pp. 1–163. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, D.K.; Hajra, P.K. Floristic diversity. In Changing Perspectives of Biodiversity Status in the Himalaya; Gujral, G.S., Sharma, V., Eds.; British Council Division: New Delhi, India, 1996; pp. 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Folke, C. Traditional knowledge in socioecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2004, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarver, J.; Kumar, S.; Khan, M.; Ara, M.; Anand, V.K. Diversity, distribution and utilization pattern of economically important woody plants associated with agro-forestry in district Rajouri, J&K (Northwest Himalaya). Ethno Leafl. 2009, 13, 801–809. [Google Scholar]

- Dangwal, L.R.; Singh, T. Ethno-Botanical study of some forest medicinal plants used by Gujjar tribe of district Rajouri (J&K), India. In The Gujjars; Rahi, J., Ed.; J&K Academy of Art Culture and Languages: Srinagar, India, 2013; pp. 247–253. [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari, B.S. Ethno-medicinal plants used by the Gujjar-Bakerwal tribe and local inhabitants of District Rajouri of Jammu and Kashmir State. Glob. J. Res. Med. Plants Ind. Med. 2015, 4, 182. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, A.; Bharati, K.A.; Ahmad, J.; Sharma, M.P. New ethnomedicinal claims from Gujjar and Bakerwals tribes of Rajouri and Poonch districts of Jammu and Kashmir, India. J. Ethnophar. 2015, 166, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, Z.A.; Pant, S.; Singh, B. Descriptive study of plant resources in context of the ethnomedicinal relevance of indigenous flora; a case study from Rajouri-Poonch region of Himalaya. Ethno. Res. Appl. 2021, 21, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, M.; Edwards, S.; Moerman, D.E.; Leonti, M. Ethnopharmacological field studies: A critical assessment of their conceptual basis and methods. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 124, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.K.; Rao, R.R. Handbook of Field and Herbarium Methods; Today and Tomorrows Printers and Publishers: New Delhi, India, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, B.M.; Kachroo, P. Flora of Jammu and Plants of Neighborhood; Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh: Dehradun, India, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, J.B.; Kachroo, P. Flora of Pir Panjal Range (Northwestern Himalaya); Bishen Singh and Mahendra Pal Singh: Dehradun, India, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, N.P.; Singh, D.K.; Uniyal, B.P. Flora of Jammu and Kashmir; Botanical Survey of India; Ministry of Environment and Forests: Calcutta, India, 2002.

- Dar, G.H.; Malik, A.H.; Khuroo, A.A. A contribution to the flora of Rajouri and Poonch districts in the Pir Panjal Himalaya (Jammu & Kashmir), India. Check List 2014, 10, 317–328. [Google Scholar]

- Pant, S.; Wani, Z.A.; Farooq, A.; Sharma, V. Economically Important Plants of District Rajouri, J&K, Western Himalaya; Indu Book Services Private Limited: NewDelhi, India, 2021; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mir, T.A.; Jan, M.; Khare, R.K. Ethnomedicinal application of plants in Doodh ganga forest range of district Budgam, Jammu and Kashmir, India. Euro. J. Integ. Med. 2021, 46, 101366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Manhas, R.K.; Magotra, R. Ethnoveterinary remedies of diseases among milk yielding animals in Kathua, Jammu and Kashmir, India. J. Ethnophar. 2012, 141, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Hamal, I.A. Wild edibles of Kishtwar high altitude national park in northwest Himalaya, Jammu and Kashmir (India). Ethno Leafl. 2009, 13, 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay, B.; Dhaker, A.K.; Kumar, A. Ethnomedicinal and ethnopharmaco-statistical studies of Eastern Rajasthan, India. J. Ethnophar. 2010, 129, 64–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, M.S.; Abdelrasool, F.E.; Elsheikh, E.A.; Ahmed, L.A.M.N.; Mahmoud, A.L.E.; Yagi, S.M. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in the Blue Nile State, South-eastern Sudan. J. Med. Plants Res. 2011, 5, 4287–4297. [Google Scholar]

- Tali, B.A.; Khuroo, A.A.; Ganie, A.H.; Nawchoo, I.A. Diversity, distribution and traditional uses of medicinal plants in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) state of Indian Himalayas. J. Herbal Med. 2019, 17, 100280. [Google Scholar]

- Lone, P.A.; Bhardwaj, A.K. Traditional herbal based disease treatment in some rural areas of Bandipora district of Jammu and Kashmir, India. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2013, 6, 162–171. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R.; Manhas, R.K. Ethnoveterinary plants for the treatment of camels in Shiwalik regions of Kathua district of Jammu & Kashmir, India. J. Ethnophar. 2015, 169, 170–175. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.; Sharma, V.; Kumar, S.; Jaryan, V. An Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants of Billawar Region, Jammu and Kashmir, India. J. Moun. Res. 2021, 16, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.K.; Sharma, O.P.; Raina, N.S.; Sehgal, S. Ethno-botanical study of medicinal plants of Paddar valley of Jammu and Kashmir, India. Afr. J. Trad. Compl. Alter. Med. 2013, 10, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, Z.A.; Farooq, A.; Sarwar, S.; Negi, V.S.; Shah, A.A.; Singh, B.; Siddiqui, S.; Pant, S.; Alghamdi, H.; Mustafa, M. Scientific Appraisal and Therapeutic Properties of Plants Utilized for Veterinary Care in Poonch District of Jammu and Kashmir, India. Biology 2022, 11, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, A. Studies on pharmaceutical ethnobotany in the region of Turkmen Sahra, north of Iran: (Part1): General results. J. Ethnophar. 2005, 102, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.; Andrabi, S.A.H. An approach to the study of traditional medicinal plants used by locals of block Kralpora Kupwara Jammu and Kashmir India. Inter. J. Bot. Stud. 2021, 6, 1433–1448. [Google Scholar]

- Jan, M.; Mir, T.A.; Khare, R.K. Indigenous medicinal usage of family Solanaceae and Polygonaceae in Uri, Baramulla, Jammu and Kashmir. J. Med. Herbs Ethnomed. 2020, 6, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, Z.A.; Pant, S. Ethnomedicinal study of plants used to cure skin diseases and healing of wounds in Gulmarg Wildlife Sanctuary (GWLS), Jammu & Kashmir. Ind. J. Trad. Know. 2020, 19, 327–334. [Google Scholar]

- Tali, B.A.; Khuroo, A.A.; Nawchoo, I.A.; Ganie, A.H. Prioritizing conservation of medicinal flora in the Himalayan biodiversity hotspot: An integrated ecological and socioeconomic approach. Environ. Cons. 2019, 46, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, M.; Khuroo, A.A.; Ahmad, R.; Rasheed, S.; Malik, A.H.; Dar, G.H. Threatened Flora of Jammu and Kashmir State. In Biodiversity of the Himalaya: Jammu and Kashmir State; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 957–995. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017. Available online: http://www.iucnredlist.org (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Nayar, M.P.; Sastry, A.R.K. Red Data Book of Indian Plants; BSI: Calcutta, India, 1988; Volumes 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, K.S.; Gillett, H.J. IUCN Red List of Threatened Plants; Compiled by the World Conservation Monitoring Centre; IUCN—The World Conservation Union: Gland, Switzerland; Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Molur, S.; Walker, S. Report of the Workshop “Conservation, Assessment and Management Plan for Selected Medicinal Plants of Northern, Northeastern and Central India”; (BCPP Endangered Species Project) Zoo Outreach Organisation; Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, India: Coimbatore, India, 1998; p. 62. [Google Scholar]

- Dar, G.H.; Naqshi, A.R. Threatened flowering plants of the Kashmir Himalaya—A checklist. Orien. Sci. 2001, 6, 23–53. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, C.S.; Suresh, B.L.; Suresh, G. Red List of Threatened Vascular Plant Species in India; ENVIS, Botanical Survey of India; Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India: Howrah, India, 2003.

- Ved, D.K.; Kinhal, G.A.; Ravikumar; Prabhakaran; Ghate, U.; Sankar, R.V.; Indresha, J.H. CAMP Report: Conservation Assessment and Management Prioritization for Medicinal Plants of Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh and Uttaranchal; Foundation for Revitalization of Local Health Traditions: Bangalore, India, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wani, Z.A.; Bhat, J.A.; Negi, V.S.; Satish, K.V.; Siddiqui, S.; Pant, S. Conservation Priority Index of species, communities, and habitats for biodiversity conservation and their management planning: A case study in Gulmarg Wildlife Sanctuary, Kashmir Himalaya. Front. For. Glob. Chan. 2022, 5, 995427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, Z.A.; Islam, T.; Satish, K.V.; Ahmad, K.; Dhyani, S.; Pant, S. Cultural value and vegetation structure of Buxus wallichiana Bail. In Rajouri-Poonch region of Indian Himalayan region (VSI: Mountainous regions). Trees For. People 2022, 7, 100182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, U.; Adams, W.M.; Díaz, S.; Lele, S.; Mace, G.M.; Turnhout, E. Biodiversity and the challenge of pluralism. Nat. Sustain. 2021, 4, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, Z.A.; Satish, K.V.; Islam, T.; Dhyani, S.; Pant, S. Habitat suitability modelling of Buxus wallichiana Bail.: An endemic tree species of Himalaya. Vegetos 2022, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.K.; Rai, A.; Abdelrahman, K.; Rai, S.C.; Tiwari, A. Analysing challenges and strategies in land productivity in Sikkim Himalaya, India. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, S.C.; Mishra, P.K. Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Resource Management: A Conceptual Framework. In Traditional Ecological Knowledge of Resource Management in Asia; Rai, S.C., Mishra, P.K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.K.; Rai, A.; Rai, S.C. Indigenous knowledge of terrace management for soil and water conservation in the Sikkim Himalaya, India. Ind. J. Trad. Know. 2020, 19, 475–485. [Google Scholar]

- Silori, C.S. Perception of local people towards conservation of forest resources in Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve, north-western Himalaya, India. Biodivers Conserv. 2007, 16, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.C.; Jordan, A.; Searle, K.R.; Butler, A.; Chapman, D.S.; Simmons, P.; Watt, A.D. Does stakeholder involvement really benefit biodiversity conservation? Biol. Conserv. 2013, 158, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).