Abstract

As the gig economy grows, the side hustle has become a hot topic; however, little research has focused on the influence of side-hustle behavior from a microscopic perspective. This study explores how and when individual skill variety affects side-hustle intention from an individual level. Based on self-determination theory, this study constructs an influence model of individual skill variety on side-hustle intention with role breadth self-efficacy as the mediator and side-hustle meaningfulness as the moderator. Data collected from 402 individuals in China through a questionnaire survey were used for empirical analysis. The results indicate that (a) individual skill variety is positively associated with side-hustle intention; (b) role breadth self-efficacy plays a mediating role in the relationship between individual skill variety and side-hustle intention; (c) side-hustle meaningfulness moderates the relationship between role breadth self-efficacy and side-hustle intention, and moderates the mediating effect of role breadth self-efficacy. Finally, the theoretical implications and limitations are discussed.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the gig economy, which is based on the sharing economy, has gradually grown with the innovation of Internet technology. McKinsey, a well-known business consulting firm in the United States, wrote a research report to predict future employment trends; it proposed that “the future career trend is the gig economy” and predicted that the total annual revenues of the global gig economy will be as high as USD 1.5 trillion by 2030. The rise of the gig economy led to the demise of the standard employment relationship and an increase in a wide range of non-standard employment relations [1,2,3]. In this new context, various terms have emerged, such as multiple job holding, moonlighting, side hustle, and part-time job. They represent a similar meaning. However, as the gig economy sweeps the world, side hustle has become the more popular term as it more closely relates to the burgeoning gig economy [4,5,6]. Hence, we mainly use the term side hustle to conduct our research. However, as we refer to the relevant literature, other terms will occasionally appear below. Experts estimate that between 5% and 35% of the working population in the United States juggles multiple jobs [7]. Approximately 10.5% of British workers in Britain hold second jobs [8].

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated such a process because side hustles are more needed in this period [9]. The abovementioned details indicate that the gig economy is prosperous, and non-standard employment relations in the gig economy are bound to become a hot topic in human resource management and continue for a long time. In China, the gig economy is also flourishing. According to the China County Gig Economy Survey Report in 2019, the number of people with gig income in the county market reached 52.27%, among which there were both main business income and gig income, accounting for 24.72% of the total. The report also shows that more than 90% of county users are willing to engage in a side hustle. Thus, the development trend of the new occupation of the side hustle will become a hot spot in future economic development, and the study of side-hustle behavior will gradually become an important topic for scholars.

Because of the research on the influencing factors of side-hustle intention, the previous literature on multiple job holding has identified several potential motives behind the side hustle [10,11]. First, early empirical research focused on time-limited motivation and believed employees hold side hustles out of financial need. The second occupation allows low-income people to maintain their livelihoods [12]. Second, according to the standard labor–leisure model, employees may be constrained by hours. That is, employees are willing to work more but are not offered the chance to do so in their primary occupation due to overtime pay or the provisions of the Labor Code [13]. With the deepening of research, apart from financial motivation, more and more scholars have identified additional motives for a side hustle. Finally, employees may have a side hustle for non-material benefits such as skills and experience or self-actualization [14,15,16,17]. These initial investigations provide an important window into a side hustle, but they are still limited. Few studies have been conducted to understand the relationship between individual skill variety and side-hustle intention. In China, as an important representative of atypical employment, side hustles have occupied an increasingly important position in economic activities. In contrast, the theoretical community has not matched the theoretical research, and the relevant papers are even fewer. Based on self-determination theory, this study explores the effects of individual skill variety on side-hustle intention based on self-determination theory.

In conclusion, based on self-determination theory, this study constructs the influence model of individual skill variety on side-hustle intention, in which role breadth self-efficacy is the mediator and side-hustle meaning is the moderator. The contributions of this study are as follows. First, this study enriches the research on a side hustle in the gig economy. Second, this study reveals the influence mechanism of individual skills on side-hustle intention via role breadth self-efficacy, broadening the antecedent variable of side-hustle intention. Third, this study extends the boundary conditions of the influence of individual skills on the side-hustle intention by introducing side-hustle meaningfulness.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Side-Hustle Intention

Globalization, technological advances, economic uncertainty, and the establishment of digitalization provide opportunities for alternative work arrangements [18]. In this new context, individuals have a wider range of career options and opportunities that allow them to enrich their work experience and derive greater satisfaction from their work [19].

A side hustle refers to income-generating work performed on the side of a full-time job [6]. The side-hustle intention is defined as the willingness of individuals to carry out a side hustle beside their full-time job. As individuals’ proactive behavior, a side hustle includes solving problems and finding ways to change work situations [20,21,22]. Of course, going beyond the organization’s boundaries and current formal role to generate side-hustle intentions is also a proactive behavior because the essence of having a side hustle is employees’ proactive behavior to explore a wider range of roles. In the organization, employees always want to be able to find their stage and use their full energy. Therefore, they will be more proactive in finding opportunities to use their talents. When employees’ full-time work cannot meet their ambitions to show their talents, they will seek change, such as doing side hustles to fill their free time to make the most of their talents. For them, a side hustle can provide the opportunity to learn new functions and practice new skills, allowing them to make the most of their free time to achieve self-improvement and be able to take on more roles [23].

2.2. Individual Skill Variety

Individual skill variety is an extension of the definition of skill variety. Skill diversity is an important part of the job characteristics model, and its definition is the degree to which a job involves various activities in carrying out the duty, which demands the use of several different skills and talents of the employee [24]. Though the later literature pointed out that additional skills may not be valuable for the job, they make sense to individuals [25]. Following this perspective, individual skill variety is defined in this study as an individual possessing various skills or knowledge through training programs or job rotations [26].

2.3. Side-Hustle Meaningfulness

Meaning refers to the magnitude of an individual’s perceived value in an activity and is an individual’s subjective understanding and recognition of work experience [27,28,29]. Side hustles provide varying degrees of meaning or degrees to which individuals feel that activities have value and importance [30]. Side-hustle meaningfulness refers to the meaning that employees perceive in their side hustles, which can also be summarized as the degree of recognition of side hustles by employees [6]. A side hustle may be meaningful for various reasons; for example, some part-time jobs can give employees additional income and a higher quality of material life, or they may be able to meet personal interests and work needs [31]. In addition, pursuing self-actualization can also enrich the meaning of a side hustle [32].

2.4. Role Breadth Self-Efficacy

Bandura proposed the concept of self-efficacy [33]. Parker further developed the concept by proposing role breadth self-efficacy, which refers to how individuals view themselves as capable of carrying out broader and more proactive work roles beyond traditional and prescribed technical requirements [34]. Unlike general self-efficacy, role breadth self-efficacy is a specific type of self-efficacy. It focuses not merely on a particular talent but on the broader role competency that employees perceive. Furthermore, role breadth self-efficacy has been shown to inspire proactive behavior at work [21,22,35,36,37,38,39,40].

2.5. Self-Determination Theory

Self-determination theory is one of the major macro theories about human motivation in psychology [41,42]. It assumes that human beings are positive, growth-oriented organisms with a tendency towards psychological growth and development. Self-determination theory evolved from research on intrinsic and extrinsic motivations and expanded to include research on work organizations and other domains of life [41]. It proposes a classification of autonomous motivation and controlled motivation. Autonomous motivation is an individual’s motivation to engage in a certain behavior out of the inner will (such as interests, hobbies, etc.). Meanwhile, controlled motivation refers to the individual’s motivation to engage in a certain behavior out of internal or external pressure (such as guilt, command, etc.). Self-determination theory emphasizes people’s inherent and autonomous motivational propensities for learning and growing and regards autonomous motivation as high quality [43,44]. To discuss the conditions for internalizing extrinsic motivations, the theory argues that three basic psychological needs underlie high-quality motivation. When these needs are satisfied, employees show their highest quality efforts and well-being [45]. These three basic psychological needs are autonomy, relatedness, and competence.

2.6. Individual Skill Variety and Side-Hustle Intention

According to self-determination theory, employees with skill variety may have the autonomous motivation to engage in a side hustle. In other words, the higher the individual skill variety is, the higher the intrinsic motivation to engage in side hustle is. In general, the more skills employees have, the more qualified they are for a wide range of roles, and they will be more willing to try a side hustle, and their side-hustle intentions will be stronger. Some studies have asserted that competence may be a prerequisite for certain types of proactive behavior [46]. Limitations of abilities will limit employees to define more roles [47]. First, exploring a wider range of roles means being able to take on more tasks, and it is all built on a variety of individual skills. Second, when individuals have multiple skills, they are more likely to combine different knowledge and skills to burst into creativity, to make more active extra-role behavior, such as producing side-hustle intention. Thus, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1.

Individual skill variety positively affects side-hustle intention.

2.7. Mediating Role of Role Breadth Self-Efficacy on the Relationship of Individual Skill Variety and Side-Hustle Intention

According to previous research, a range of skills training can lead to higher role breadth self-efficacy [48], as role breadth self-efficacy is based on mastering enough experience and skills. The more skills employees master, the stronger their abilities, and their confidence in their role will also double, so they will be more relaxed about work tasks and even make proactive behaviors. Self-determination theory also provides relevant evidence; competency is one of the three basic psychological satisfactions. The more skills employees hold, the more competent they are. The more likely it is that employees’ autonomous motivation is stimulated, and role breadth self-efficacy will expand this autonomous motivation to develop side-hustle intentions [49]. In addition, self-determination is an experience-based choice; individuals can make choices about their actions based on full awareness of their needs (the need for self-actualization and display of talent) and environmental information (the prevalence of side hustles).

On the one hand, the diversity of skills can provide conditions for employees to expand the breadth of their roles, and they can keep a high level of role breadth self-efficacy. In addition, some previous studies have shown that initiatives such as job design (e.g., task control, job expansion), skills training, workplace communication, and participation in improvement groups may contribute to role breadth self-efficacy. On the other hand, individuals who define their role broadly will be more motivated to engage in proactive behaviors than those who define their role more narrowly [22]. Hence, employees with high role breadth self-efficacy are more convinced of their abilities to perform well and will be more likely to take the initiative [50]. Taking together the above arguments and evidence, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 2.

Individual skill variety positively affects role breadth self-efficacy.

Hypothesis 3.

Role breadth self-efficacy positively affects side-hustle intention.

Hypothesis 4.

Role breadth self-efficacy mediates the relationship between individual skill variety and side-hustle intention.

2.8. Moderating Role of Side-Hustle Meaningfulness

Side-hustle meaningfulness refers to the meaningfulness that employees perceive in their side hustles, which can also be summarized as the degree of recognition of side hustles by employees. Specifically, by engaging in a side hustle, an individual can obtain additional economic income to meet their basic living needs, meet individual interests, and realize self-worth. The meaningfulness of a role affects how deeply an individual will invest themselves in the role [51,52]. Thus, we can refer that side-hustle meaningfulness contributes to individuals’ side-hustle intention. The more meaning employees perceive, the higher the extrinsic motivation to engage in a side hustle is, and the side-hustle intention is higher. According to self-determination theory, both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation affect individuals’ behavior intention. Role breadth self-efficacy is seen as intrinsic motivation, while side-hustle meaningfulness is seen as extrinsic motivation. Therefore, role breadth self-efficacy and side-hustle meaningfulness affect side-hustle intention. When individuals perceive higher side-hustle meaningfulness, the higher role breadth self-efficacy they perceive, the higher the willingness to engage in a side hustle. Conversely, when individuals perceive lower side-hustle meaningfulness, indicating that the employees’ recognition of the side-hustle is low, they will avoid investing in the side-hustle, which will weaken the effect of the role breadth self-efficacy on the side-hustle intention. Thus, we contend the following:

Hypothesis 5.

Side-hustle meaningfulness positively moderates the relationship between role breadth self-efficacy and side-hustle intention; the greater the employee’s perception of the meaningfulness of a side-hustle, the greater the influence of role breadth self-efficacy on the side-hustle intention.

Hypothesis 4 reveals the mediating role of role breadth self-efficacy on the relationship between individual skill variety and side-hustle intention. Finally, Hypothesis 5 indicates the moderating effect of side-hustle meaningfulness on the relationship between role breadth and self-efficacy. Based on the above assumptions, we can infer that side-hustle meaningfulness will further moderate the mediating effect of role breadth self-efficacy on the relationship between individual skill variety and side-hustle intention. In sum, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 6.

Side-hustle meaningfulness regulates the mediating role of role breadth self-efficacy. The higher the side-hustle meaningfulness, the stronger the mediating effect of the role breadth self-efficacy between individual skill variety and side-hustle intention.

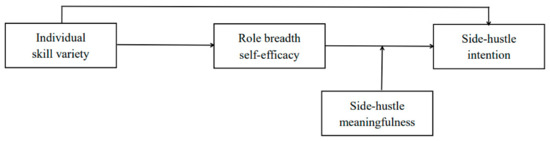

Based on the above research assumptions, the theoretical research framework constructed is shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1.

Theoretical model.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedures

In this study, we adopted an online survey to collect data. From June to August 2021, electronic questionnaires were sent to individuals using the questionnaire data collection platform “credamo” in China. The anonymity of the questionnaire was emphasized in the questionnaire, and the participants were informed that the content filled in was only for academic research, so as to ensure that the participants answered truthfully according to the actual situation. In addition, a screening question “At present, do you have a full-time job? And do you have any part-time jobs?” was designed in the questionnaire. The respondents who answered, “At present, I have a full-time job, and I don’t have any part-time jobs?” could continue to participate in the questionnaire. A total of 500 questionnaires were collected, 98 were discarded for patterned responses, such as alternating between options or clicking the midpoint or random responses [53], leaving 402 valid questionnaires, with a response rate of 80%. Sample descriptions are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The results of demographic information (n = 402).

3.2. Measure

The scales of the main variables adopted in this study were developed in English, and so all scales were translated into Chinese to conduct a questionnaire in China. In addition, to ensure translation accuracy, we followed the standard translation and back-translation procedures [54]. All measures utilized 5-point Likert scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Side-hustle intention: Side-hustle intention was measured with a seven-item scale derived from the Seema [16]. Sample items included “I would like to find a part-time job outside my full-time job” and “I would consider a high-paying side hustle”.

Role breadth self-efficacy: Role breadth self-efficacy was measured with a seven-item scale developed by Parker and Williams [22]. Sample items such as “I feel confident when presenting information to a group of colleagues” and “I feel confident in suggesting different approaches for other department tasks”.

Individual skill variety: We measured individual skill variety by modifying the three-item scale developed by Morgeson and Humphrey [55]. An example item was “I think I have a variety of knowledge skills or strengths”.

Side-hustle meaningfulness: Side-hustle meaningfulness was measured with a ten-item scale developed by Sessions [6]. Example items included “Side hustle can bring me extra income” and “Side hustle can meet my self-realization need by satisfying my interest”.

Control variables: Previous literature has shown that demographic variables may influence individual side-hustle intention including gender, age, and education [6,16,17]. Thus, we controlled for variables such as gender, age, and education in this study. Gender was measured as a dummy variable (1 = male, 2 = female). Age was divided into five levels (1 = 18–25 years old, 2 = 26–30 years old, 3 = 31–35 years old, 4 = 36–40 years old, 5 = 41 years old or above). Education was divided into four levels (1 = high school or below, 2 = junior college, 3 = bachelor, 4 = master or above).

3.3. Reliability and Validity Tests

SPSS25.0 was used to test the reliability of all variables in this study. The results indicate that the Cronbach’s alpha of individual skill variety, role breadth self-efficacy, side-hustle meaningfulness, and side-hustle intention were 0.736, 0.856, 0.912, and 0.731, respectively (see Table 2). The Cronbach’s alpha for all variables were greater than the critical value of 0.7, indicating this questionnaire has good reliability.

Table 2.

Reliability and validity test results.

According to the convergent validity test criteria, the factor loading should exceed 0.5, the average variance extracted (AVE) should exceed 0.5 under ideal conditions, and 0.36–0.50 are acceptable, and the composite reliability (CR) should exceed 0.6. Table 2 shows that the factor loading, AVE, and CR of individual skill variety, role breadth self-efficacy, and side-hustle meaningfulness all met the criteria. While the factor loading for items 2 and 7 of side-hustle intention did not reach 0.5. Hence, we deleted those two items in subsequent analyses, and the value of AVE increased from 0.328 to 0.479, and the value of CR increased from 0.679 to 0.786. Therefore, the convergent validity of all variables reached the criteria.

AMOS 24.0 was used to conduct confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to test discriminant validity. The hypothetical four-factor model (i.e., individual skill variety, role breadth self-efficacy, side-hustle meaningfulness, and side-hustle intention) had a better fit to the data (χ2/df = 2.123, RMESA = 0.053, SRMR = 0.053, CFI = 0.929, TLI = 0.921) than the other competition models (see Table 3). The results of CFA confirmed that scales for variables in this study have good discriminant validity.

Table 3.

Confirmatory factor analyses.

3.4. Common Method Variance

To test the common method variance of the research model, we performed the Harman’s single-factor test [56,57]. The result shows that the first principal component has explained 28.605% loading (<50%), indicating the common method variance of this study is well controlled.

3.5. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

Table 4 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations of the study variables. From the perspective of variable correlation, role breadth self-efficacy was positively correlated with individual skill variety (r = 0.263, p < 0.01), and was positively correlated with side-hustle meaningfulness (r = 0.374, p < 0.01). Similarly, side-hustle intention was positively correlated with individual skill variety (r = 0.295, p < 0.01), role breadth self-efficacy (r = 0.387, p < 0.01), and side-hustle meaningfulness (r = 0.281, p < 0.01). These correlations are consistent with the expectations of the theory and provide initial support for the hypotheses.

Table 4.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations.

3.6. Hypotheses Testing

First, we used SPSS25.0 to conduct hierarchical regression analysis. The test results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Hypotheses test results.

Model 3 in Table 5 shows that individual skill variety positively correlates with side-hustle intention (β = 0.296, p < 0.01), supporting Hypothesis 1. Model 7 in Table 5 shows that individual skill variety positively correlates to role breadth self-efficacy (β = 0.279, p < 0.01). Thus, Hypothesis 2 is supported. Model 2 in Table 5 indicates that the positive association of role breadth self-efficacy and side-hustle intention is significant (β = 0.390, p < 0.01), and the role breadth self-efficacy can explain 19% of the total variation of the side-hustle intention, that is, the higher the role breadth self-efficacy level, the higher the output level of the side-hustle intention, and thus, Hypothesis 3 is verified.

To explain the mediating effect, we followed Mathieu and Taylor’s meso-mediation analytical approach [58]. The first criterion for mediation would be a significant relationship between the independent and dependent variables. The second criterion for mediation would be a significant relationship between the independent and mediating variables. The third criterion is when the independent and mediating variables are placed in the regression model simultaneously, the mediating variable is significantly related to the dependent variable, and the significance of the independent variable on the dependent variable decreases or disappears. In the above, Hypotheses 1 and 2 were already supported, so we met the first two criteria. Compared with Model 3, the regression coefficient of individual skill variety on side-hustle intention in Model 4 decreased from 0.296 to 0.202 (p < 0.01). Moreover, the positive effect of the role breadth self-efficacy on the side-hustle intention was also significant (β = 0.334, p < 0.01). That is, role breadth self-efficacy partially mediates the influence of individual skill variety on side-hustle intention, and Hypothesis 4 is verified.

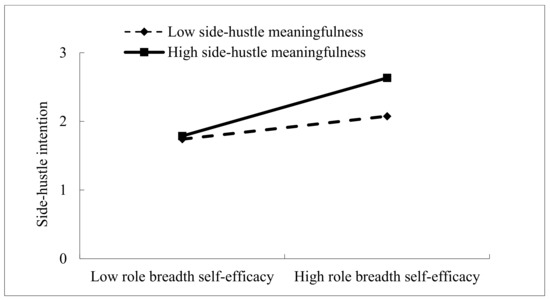

Model 5 in Table 5 shows that the interactive effect of role breadth self-efficacy and side-hustle meaningfulness on side-hustle intention is significant (β = 0.128, p < 0.01), which indicates that side-hustle meaningfulness positively moderates the relationship of role breadth self-efficacy and side-hustle intention. Furthermore, to explain more clearly the essence of the interaction effect of role breadth self-efficacy and side-hustle meaningfulness on side-hustle intention, we conducted simple slope analysis to examine the pattern of the moderating effect of side-hustle meaningfulness. We divided side-hustle meaningfulness into higher- and lower-level groups by adding and subtracting one standard deviation from the mean, performed a simple slope test, and plotted a simple effect analysis plot. Simple slope tests indicated that the positive effect of role breadth self-efficacy on side-hustle intention tends to be more positive when the employee perceives a higher level of side-hustle meaningfulness (+1SD, β = 0.088, p < 0.01) rather than the lower level of side-hustle meaningfulness (-1SD, β = 0.030, ns). Figure 2 shows that the simple slope was greater for high side-hustle meaningfulness than for low side-hustle meaningfulness. Therefore, Hypothesis 5 is supported.

Figure 2.

Interactive effects of side-hustle meaningfulness and role breadth self-efficacy on side-hustle intention.

Table 6 shows the results of the moderated mediating effect test. In the group of low side-hustle meaningfulness, the indirect effect of individual skill variety on side-hustle intention via role breadth self-efficacy is 0.030, which is insignificant (95% confidence interval = [−0.010, 0.071], containing 0); whereas in the group of high side-hustle meaningfulness, the indirect effect of individual skill variety on side-hustle intention via role breadth self-efficacy is 0.088, which is significant (95% confidence interval = [0.046, 0.136], excluding 0). In addition, the index of moderated mediation is 0.029 (95% confidence interval = [0.003, 0.059], excluding 0). Thus, the indirect effect of individual skill variety on side-hustle intention via role breadth self-efficacy is significantly moderated by side-hustle meaningfulness. Thus, Hypothesis 6 is supported.

Table 6.

Result of moderated mediating effect test.

4. Discussion

Based on self-determination theory, this study constructed an influence model of individual skill variety on the side-hustle intention with role breadth self-efficacy as the mediator and side-hustle meaningfulness as the moderator. Data collected from 402 individuals in China through a questionnaire survey were used for empirical analysis. The conclusions are as follows:

First, individual skill variety is positively associated with side-hustle intention. If employees have various skills and knowledge, their intention will certainly be to display their full talents and the realization of self-worth to find a stage. That is, the more extensive the skills an individual has, the more likely they are to engage in a side hustle to display their talents and realize their self-value.

Second, role breadth self-efficacy plays a mediating role in the relationship between individual skill variety and side-hustle intention. On the one hand, the more skills an individual has, the higher their sense of efficacy of being competent in multiple roles. On the other hand, the higher the individual’s role breadth self-efficacy, the higher their willingness to engage in a sideline hustle.

Third, side-hustle meaningfulness moderates the relationship between role breadth self-efficacy and side-hustle intention and the mediating effect of role breadth self-efficacy. For example, role breadth self-efficacy motivates the “I can do it” drive for individuals to engage in a side hustle. In contrast, side-hustle meaningfulness motivates “It is worth doing” for individuals to engage in a side hustle. Thus, side-hustle meaningfulness positively moderates the relationship between role breadth self-efficacy and side-hustle intention; the greater the employee’s perception of the meaningfulness of a side-hustle, the greater the influence of role breadth self-efficacy on the side-hustle intention.

4.1. Theoretical Implications

First, this study extends the research on the antecedent of side hustles. Previous literature on the antecedent of a side-hustle or multi-job holding includes three main categories: financial, psychological fulfillment, and career development [59,60]. Among these three main motivations, financial motivations are mentioned the most [61,62,63,64]. Some research holds that individuals’ interest in fulfilling personal needs is the motivation for a side hustle [65]. This study finds that individual skill variety has a positive effect on side-hustle intention. The reason may be that individuals with multiple skills hope to find a stage to give full play to their various skills to realize their value better. Thus, this conclusion supports previous research on the motivation of psychological fulfillment [65] and extends the research on the antecedent of side hustles.

Second, this study reveals the influence mechanism of individual variety on side-hustle intention. A large number of studies have proved that self-efficacy can predict individual behavior. Bandura introduced self-efficacy into the explanatory model of human behavior and recognized that self-efficacy would affect human behavior [66,67,68]. Role breadth self-efficacy is a specific type of self-efficacy; it focuses not only on a particular talent but also on the broader role competency that employees perceive [35,36,37,38]. According to self-determination theory, this study explains the mediating role of role breadth self-efficacy between the relationship of individual skill variety and side-hustle intentions. Role breadth self-efficacy has been proven to predict proactive behavior [50,69]. This study finds that individual skill variety may strengthen role breadth self-efficacy, providing impetus for individuals to generate side-hustle intentions. This conclusion enriches the research on the role breadth self-efficacy and broadens the influence mechanism of individual skill variety on side-hustle intention.

Third, this study extends the boundary conditions of the influence of individual skills on a side hustle by introducing side-hustle meaningfulness. Side-hustle meaningfulness refers to the meaningfulness that employees perceive in their side hustles, which can also be summarized as the degree of recognition of side hustles by employees [6]. However, some researchers have also indicated that the meaningfulness of a role affects how deeply an individual will invest themselves in the role [51]. Few studies have focused on side-hustle meaningfulness. This study takes the step to introduce side-hustle meaningfulness into the model of individual skill variety on side-hustle intention and finds that side-hustle meaningfulness moderates the mediating effect of role breadth self-efficacy. This conclusion not only enriches the research on side-hustle meaningfulness but also reveals the boundary conditions of the influence mechanism of individual skill variety on side-hustle intention through role breadth self-efficacy.

4.2. Limitations and Future Research

First, the questionnaire method was used in this study; although the process of preparing and administering the questionnaire was strictly controlled, it is still an indirect measurement. Hence, future research should consider using quasi-experimental or field-based research methods in future studies, which help improve the accuracy of research conclusions.

Second, some earlier studies concluded that women were more likely than men to develop side-hustle intentions [15]. In this study, the ratio of men to women was slightly uncoordinated, which may also affect the accuracy of the results. Thus, future research should increase the sample size and achieve a balanced collection of samples in enterprises as much as possible (e.g., harmonize the ratio of men to women), using larger and more heterogeneous samples of participants differing in relevant socio-demographic characteristics such as age, gender, education level, industry background, and job position. By doing so, the conclusions can be more realistic and convincing, and the application value of the research would be improved further.

Lastly, this study focuses on the antecedent of side-hustle intention but does not consider the outcomes of side hustles. However, organizations are concerned whether employees undertaking side hustles could harm their full-time job. Therefore, future research should consider how side hustles affect full-time job performance.

Author Contributions

Investigation, Z.M.; data analysis, P.T. and Z.M.; writing—original draft preparation, P.T.; writing—review and editing, H.W. and Z.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Conen, W. Multiple jobholding in Europe: Structure and dynamics (Research Report No. 20). WSI Study. 2020. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/225443 (accessed on 8 January 2022).

- Conen, W.; Schippers, J. Self-Employment as Precarious Work: A European Perspective; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Conen, W.; Stein, J. A panel study of the consequences of multiple jobholding: Enrichment and depletion effects. Transf. Eur. Rev. Labour Res. 2021, 27, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sessions, H.; Nahrgang, J.D.; Vaulont, M.J.; Williams, R.; Bartels, A.L. Do the hustle! Empowerment from side-hustles and its effects on full-time work performance. Acade. Manage. J. 2021, 64, 235–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.; Andersen, E.; Davey, L.; Valcour, M. Even Senior Executives Need a Side Hustle. Harvard Business Review, 29 November 2017. Available online: https://hbr.org/2017/11/even-senior-executives-need-a-side-hustle (accessed on 8 January 2022).

- Sessions, H. Comforted by Role Continuity or Refreshed by Role Variety?: Employee Outcomes of Managing Side-Hustle and Full-Time Work Roles; Arizona State University: Tempe, AZ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Manyika, J.; Lund, S.; Bughin, J.; Robinson, K.; Mischke, J.; Mahajan, D. Independent Work Choice Necessity and the Gig Economy; McKinsey Global Institute: Chicago, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Baimbridge, M.; Zhu, Y. Multiple job holding in the United Kingdom: Evidence from the British Household Panel Survey. Appl. Econ. 2009, 41, 2751–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azavedo, M. Side hustles in the COVID-19 era. A preliminary investigation in UK and Thailand on informal and part-time work during a period of employment turmoil. Tech. Soc. Sci. J. 2022, 29, 381–389. [Google Scholar]

- Campion, E.D.; Caza, B.B.; Moss, S.E. Multiple Jobholding: An Integrative Systematic Review and Future Research Agenda. J. Manag. 2019, 46, 165–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böheim, R.; Taylor, M.P. Actual and Preferred Working Hours. Br. J. Ind. Relations 2004, 42, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlman, R. Observations on Overtime and Moonlighting. South. Econ. J. 1966, 33, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesen, J. Overtime pay regulation and weekly hours of work in Canada. Labour Econ. 2001, 8, 691–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heineck, G.; Schwarze, J. Fly me to the moon: The determinants of secondary jobholding in Germany and the UK. SSRN Electron. J. 2004, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panos, G.A.; Pouliakas, K.; Zangelidis, A. Multiple Job Holding, Skill Diversification, and Mobility. Ind. Relations: A J. Econ. Soc. 2014, 53, 223–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seema; Choudhary, V.; Saini, G. Effect of Job Satisfaction on Moonlighting Intentions: Mediating Effect of Organizational Commitment. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2020, 27, 100137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seema, M.; Sachdeva, G. Moonlighting intentions of IT professionals: Impact of organizational commitment and entrepreneurial motivation. J. Crit. Rev. 2019, 7, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelli, P.; Keller, J.R. Classifying work in the new economy. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2013, 38, 575–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petriglieri, G.; Ashford, S.; Wrzesniewski, A. Thriving in the gig economy. In HBR’s 10 Must Reads 2019: The Definitive Management Ideas of the Year from Harvard Business Review; Williams, J.C., Davenport, T.H., Porter, M.E., Iansiti, M., Eds.; Harvard Business Review Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 109–116. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, S.K.; Bindl, U.K.; Strauss, K. Making Things Happen: A Model of Proactive Motivation. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 827–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Collins, C.G. Taking Stock: Integrating and Differentiating Multiple Proactive Behaviors. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 633–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Williams, H.M.; Turner, N. Modeling the antecedents of proactive behavior at work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 636–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashford, S.J.; Caza, B.B.; Reid, E.M. From surviving to thriving in the gig economy: A research agenda for individuals in the new world of work. Res. Organ. Behav. 2018, 38, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J.R.; Oldham, G.R. Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1976, 16, 250–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, G.E. Skill-utilization, skill-variety and the job characteristics model. Aust. J. Psychol. 1983, 35, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, A.; Stuetzer, M.; Obschonka, M.; Salmela-Aro, K. The growth of entrepreneurial human capital: Origins and development of skill variety. Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 59, 645–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, B.D.; Dekas, K.H.; Wrzesniewski, A. On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Res. Organ. Behav. 2010, 30, 91–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; LoBuglio, N.; Dutton, J.E.; Berg, J.M. Job crafting and cultivating positive meaning and identity work. Adv. Posit. Organ. Psychol. 2013, 1, 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F. Meanings of Life; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Brief, A.P.; Nord, W.R. Work and meaning: Definitions and interpretations. In Meanings of Occupational Work: A Collection of Essays; Lexington Books/D. C. Health and Company: Lexington, MA, USA, 1990; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, J.M.; Grant, A.M.; Johnson, V. When Callings Are Calling: Crafting Work and Leisure in Pursuit of Unanswered Occupational Callings. Organ. Sci. 2010, 21, 973–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autin, K.L.; Herdt, M.E.; Garcia, R.G.; Ezema, G.N. Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction, Autonomous Motivation, and Meaningful Work: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective. J. Career Assess. 2021, 30, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Reflections on self-efficacy. Adv. Behav. Res. Ther. 1978, 1, 237–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K. Enhancing role breadth self-efficacy: The roles of job enrichment and other organizational interventions. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 835–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Den Hartog, D.N.; Belschak, F.D. Work Engagement and Machiavellianism in the Ethical Leadership Process. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 107, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hartog, D.N.; Belschak, F.D. When does transformational leadership enhance employee proactive behavior? The role of autonomy and role breadth self-efficacy. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, B., Jr.; Marler, L.E. Change driven by nature: A meta-analytic review of the proactive personality literature. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 75, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, D.J.; Kamdar, D.; Morrison, E.W.; Turban, D.B. Disentangling role perceptions: How perceived role breadth, discretion, instrumentality, and efficacy relate to helping and taking charge. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1200–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, K.; Griffin, M.A.; Rafferty, A.E. Proactivity Directed Toward the Team and Organization: The Role of Leadership, Commitment and Role-breadth Self-efficacy. Br. J. Manag. 2009, 20, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornau, K.; Frese, M. Construct Clean-Up in Proactivity Research: A Meta-Analysis on the Nomological Net of Work-Related Proactivity Concepts and their Incremental Validities. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 62, 44–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Olafsen, A.H.; Ryan, R.M. Self-Determination Theory in Work Organizations: The State of a Science. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2017, 4, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, C.S.; Ryan, R.M. Self-Determination Theory in Human Resource Development: New Directions and Practical Considerations. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2018, 20, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Bernstein, J.H.; Brown, K.W. Weekends, Work, and Well-Being: Psychological Need Satisfactions and Day of the Week Effects on Mood, Vitality, and Physical Symptoms. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 29, 95–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W.; Ryan, K. A meta-analytic review of attitudinal and dispositional redictors of organizational citizenship behavior. Pers. Psychol. 1995, 48, 775–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graen, G.B. Role-making processes within complex organizations. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Rand Mcnally: Chicago, MI, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Morgeson, F.P.; Delaney-Klinger, K.; Hemingway, M.A. The Importance of Job Autonomy, Cognitive Ability, and Job-Related Skill for Predicting Role Breadth and Job Performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, P.; He, W.; Long, L.-R. Why and When Empowering Leadership Has Different Effects on Employee Work Performance: The Pivotal Roles of Passion for Work and Role Breadth Self-Efficacy. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2017, 25, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, P.-C.; Han, M.-C.; Chiu, S.-F. Role Breadth Self-Efficacy and Foci of Proactive Behavior: Moderating Role of Collective, Relational, and Individual Self-Concept. J. Psychol. 2014, 149, 846–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, M.G.; Ashforth, B.E. Fostering meaningfulness in working and at work. In Positive Organizational Scholarship: Foundations of a New Discipline; Berret-Koehler: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003; Volume 309, p. 327. [Google Scholar]

- McKibben, W.B.; Silvia, P.J. Evaluating the Distorting Effects of Inattentive Responding and Social Desirability on Self-Report Scales in Creativity and the Arts. J. Creative Behav. 2017, 51, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgeson, F.P.; Humphrey, S.E. The Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ): Developing and validating a comprehensive measure for assessing job design and the nature of work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1321–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathieu, J.E.; Farr, J.L. Further evidence for the discriminant validity of measures of organizational commitment, job involvement, and job satisfaction. J. Appl. Psychol. 1991, 76, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, J.E.; Taylor, S.R. A framework for testing meso-mediational relationships in Organizational Behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2007, 28, 141–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, J.; Gold, M. ‘Portfolio Workers’: Autonomy and Control amongst Freelance Translators. Work. Employ. Soc. 2001, 15, 679–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, G.; Fronteira, I.; Jesus, T.S.; Buchan, J. Understanding nurses’ dual practice: A scoping review of what we know and what we still need to ask on nurses holding multiple jobs. Hum. Resour. Heal. 2018, 16, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averett, S.L. Moonlighting: Multiple motives and gender differences. Appl. Econ. 2001, 33, 1391–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickey, H.; Watson, V.; Zangelidis, A. What Triggers Multiple Job-Holding? A State Preference Investigation; Centre for European Labour Market Research: Aberdeen, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, B.T.; Husain, M.M.; Winters, J. Multiple job holding, local labor markets, and the business cycle. IZA J. Labor Econ. 2016, 5, 4–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throsby, D.; Zednik, A. Multiple job-holding and artistic careers: Some empirical evidence. Cult. Trends 2011, 20, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caza, B.B.; Moss, S.; Vough, H. From Synchronizing to Harmonizing: The Process of Authenticating Multiple Work Identities. Adm. Sci. Q. 2018, 63, 703–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; WH Freeman and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychol. Health 1998, 13, 623–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Health Promotion by Social Cognitive Means. Health Educ. Behav. 2004, 31, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beltrán-Martín, I.; Bou-Llusar, J.C.; Roca-Puig, V.; Escrig-Tena, A.B. The relationship between high performance work systems and employee proactive behaviour: Role breadth self-efficacy and flexible role orientation as mediating mechanisms. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2017, 27, 403–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).