Abstract

Overtourism is appearing more and more often in large world-famous cities and in many rural regions, where the infrastructure capacity is insufficient for large numbers of visitors. In rural communities, this creates resistance to tourism, traffic congestion, or damage to nature. Therefore, destinations experiencing tourism growth must have a strategy to prevent and limit the harmful effects of overtourism. The article presents a methodology that first identifies manifestations of overtourism in a destination and then uses a standardized procedure to evaluate the usability of different types of strategies in a selected destination. This procedure should lead to the creation of a comprehensive plan guaranteeing the sustainable development of tourism in the destination. The use of the methodology is explained at 12 rural locations in the Czech Republic, which were selected concerning the diversity of manifestations of overtourism.

1. Introduction

Overtourism is a problem that many successful destinations are facing [,,,,]. It is a factor limiting the development of these destinations and causing negative attitudes towards tourism among the local population [,,,]. The development of tourism, which was previously seen as a valuable element of local development in these destinations, is suddenly perceived as undesirable, with visitors labelled as invaders displacing locals and tourism service providers seen almost as enemies [,,,]. Yet the reasons for the emergence of overtourism in destinations can often be addressed, often in advance, in a preventive manner. In the Czech environment, inadequate tourism infrastructure often plays a key role, with congestion acting as a trigger for dissatisfaction among local residents [,,]. On the other hand, a good strategy for preventing the emergence of overtourism, or a strategy for eliminating its negative effects, can ensure the long-term undisturbed development of tourism in a destination without significant protests from the local population [,,,].

Due to the topicality and seriousness of the overtourism phenomenon, there are a number of academic articles dealing with this topic (from a number of articles it was possible to highlight, for example [,,]). If we were to narrow down the selection to articles that focus on the development of strategies to combat this negative phenomenon, we would find numerous case studies on different types of destinations, ranging from cities to coastal resorts [,,], to natural areas and reserves [,,], general articles on overtourism that point out the various elements that need to be taken into account in strategies but not describing them [,,,,], and finally analyses and proposals for real strategies, or comparisons between them [,,]. A key indicator in many studies is the tourism carrying capacity of a site [,,], which, however, like the whole concept of overtourism, is only very vaguely defined, as it is practically impossible to quantify objectively what number of tourists is already excessive or damaging to the site [,,]. Nevertheless, various mathematical expressions of carrying capacity dominate many strategies for mitigating the negative effects of overtourism [,,].

Another current approach to the topic is to emphasize the use of modern technologies, especially everything that is “smart”, i.e., constantly up-to-date and accessible via the internet [,,]. Although the results of these approaches are still often questionable, many experts see them as the future of sustainable destination management (but some others doubt, see []). A third important trend is the emphasis on the uniqueness of each location, especially taking into account the differences between urban and rural areas, developed and developing countries, etc. [,,]

A major problem in developing strategies to combat the manifestations of overtourism is that often this is due to the success of previous campaigns to attract tourists to a destination or region []. Thus, good place branding can result in unintended overtourism, leading some key actors to believe that the ideal approach to reversing this trend is to stop promoting the destination [,,] and reduce the flow of money into the creation of tourism infrastructure. However, as expert studies show [,], this problem requires a much more sophisticated approach, combining a range of measures both in communicating with visitors, in establishing rules in endangered natural sites and overtourism-affected communities, in planning the development of tourism infrastructure and, where appropriate, in introducing various regulations. The trend in recent years has been to focus on the quality of services rather than the quantity and to try to create a steady-state tourism in the destination [].

Overtourism often stems from FOMO (fear of missing out) [,]. Once a destination is well-known, visited or even iconic, many people get the feeling that if they miss the destination they will miss out. This unfortunately makes it very difficult to limit the negative effects of overtourism once it has already broken out, and much more beneficial to prevent it. However, many destinations neglect preventive measures and only react to the situation once overtourism has already occurred [,].

The aim of this article was to present a method to mitigate the negative effects of overtourism. This method was presented at two scientific conferences [,] where its use was discussed with experts in the field of tourism and nature conservation. However, in the form of a technical article and its application to a set of 12 selected sites, it is published here for the first time. The purpose of applying the method to a given tourist destination is to develop a comprehensive strategy that will either limit the occurrence of overtourism (in the case of regulatory measures) or at least mitigate its negative impacts on the local population and nature.

1.1. (Over)tourism Impacts

Tourism, while contributing significantly to economic development and cultural exchange, is not without its array of challenges, spanning social, cultural, economic, and ecological dimensions. This section explores the multifaceted impacts of tourism, highlighting the complex interplay between the industry and its host communities and environments. Tourism can exert profound social effects on destination communities. Rapid tourism growth may lead to social inequalities, as the economic benefits are not uniformly distributed [,]. Local residents may face increased living costs, housing shortages, and job competition, exacerbating pre-existing disparities. Moreover, cultural clashes and misunderstandings may arise, impacting social cohesion and local identity [,].

Cultural erosion is a common consequence of tourism, where traditional practices and lifestyles may be commodified or altered to cater to tourist expectations. This can result in the loss of authenticity and the dilution of indigenous cultures. Additionally, the influx of tourists may lead to the degradation of cultural heritage sites, as increased visitation poses threats to the preservation of historical artifacts and structures [,].

While tourism is a major economic driver, its benefits are often unevenly distributed. Small businesses may struggle to compete with larger, international enterprises, leading to a concentration of wealth in the hands of a few. Dependence on tourism can make economies vulnerable to fluctuations in visitor numbers, exposing communities to economic instability [,].

Ecological consequences of tourism are manifested in environmental degradation, habitat destruction, and pollution. Overdevelopment of infrastructure to accommodate tourists can disrupt ecosystems, leading to deforestation, loss of biodiversity, and soil erosion [,]. Furthermore, increased waste generation and improper disposal practices associated with tourism contribute to environmental pollution [,].

Mitigating these impacts requires comprehensive and sustainable tourism management strategies. This involves the integration of community-based approaches, stringent regulations, and environmental conservation measures to ensure that tourism development aligns with the principles of responsible and ethical practices. In conclusion, the social, cultural, economic, and ecological impacts of tourism underscore the need for a holistic and conscientious approach to tourism management. Balancing the economic benefits with the preservation of cultural heritage and environmental integrity is imperative for fostering sustainable tourism practices.

1.2. Relationship between Tourism Carrying Capacity and Overtourism

Tourism carrying capacity and overtourism represent pivotal concepts in the discourse surrounding sustainable tourism management [,]. Carrying capacity refers to the maximum number of visitors that an area can accommodate without compromising its environmental, social, and cultural integrity. This metric is often determined by factors such as infrastructure, natural resource availability, and the capacity of local communities to absorb tourism-related impacts. In contrast, overtourism is a phenomenon characterized by an excessive influx of tourists, surpassing the established carrying capacity, leading to detrimental effects on the destination [,].

The key distinction between carrying capacity and overtourism lies in their temporal and quantitative aspects. Carrying capacity is a dynamic and adaptable measure that considers the sustainability of tourism over the long term. It involves careful planning and monitoring to ensure that tourism remains within the ecological and social limits of a destination. Overtourism, on the other hand, is an acute condition resulting from the sudden surge in tourist numbers, often overwhelming the capacity of a destination. It can lead to negative consequences such as environmental degradation, overcrowding, cultural erosion, and strained community relations [,,].

The concept of carrying capacity within the realm of tourism management is indeed dynamic, encompassing various factors that extend beyond mere physical limitations. This assertion is grounded in the understanding that the sustainable capacity of a destination is influenced by a confluence of variables, including visitor behavior, psychological carrying capacity, spatial dispersion, and environmental conditions.

Carrying capacity is intricately tied to the behavior of visitors [,]. The actions and choices of tourists play a pivotal role in determining the impact of their presence on a destination. For instance, responsible and sustainable tourist behavior, such as adherence to local regulations and cultural norms, can mitigate the negative effects on the destination’s social and cultural fabric.

Psychological carrying capacity introduces a subjective dimension to the concept, emphasizing the perceptions and tolerance levels of both residents and visitors. It is defined by how individuals perceive and experience the level of crowding, noise, and other environmental factors [,]. Understanding and managing psychological carrying capacity is crucial for maintaining a positive visitor experience and preventing the negative consequences associated with overcrowding.

The dispersion of visitors across the territory is a critical aspect of carrying capacity. Even if the overall number of tourists aligns with the physical capacity of a destination, uneven distribution can lead to localized congestion and environmental strain. Effective management involves strategies to encourage the equitable spread of visitors, reducing the impact on specific areas and fostering a more sustainable tourism model [,].

Carrying capacity is also contingent on environmental variables such as weather conditions and the time of year. Seasonal fluctuations and adverse weather can influence the capacity of a destination to accommodate visitors comfortably [,]. Understanding these climatic variations is essential for implementing adaptive management strategies that consider the dynamic nature of tourism demand.

This holistic perspective, supported by academic research, reinforces the need for comprehensive and adaptable tourism management strategies.

Effective management of carrying capacity involves proactive planning, stakeholder engagement, and the implementation of sustainable tourism practices. This may include the development of visitor quotas, infrastructure improvements, and community-based initiatives. Overtourism, however, necessitates immediate interventions to address the adverse impacts. Strategies may involve implementing visitor restrictions, diversifying tourism offerings, and fostering community participation in decision-making processes.

In conclusion, while carrying capacity serves as a proactive and long-term planning tool to ensure sustainable tourism, overtourism represents a critical condition resulting from the rapid surpassing of these capacity limits. Both concepts underscore the importance of comprehensive and adaptive tourism management strategies to preserve the environmental, social, and cultural fabric of destinations.

1.3. Selected Overtourism-Affected Destinations

A total of 12 rural destinations in the Czech Republic were selected for analysis to reflect the diversity of manifestations of overtourism and the origin of their source. Although some of the destinations are towns (Český Krumlov and Kutná Hora have more than 10,000 inhabitants), the designation “rural” was based on the form of overtourism that manifests itself in these destinations. While typical urban overtourism (with the exception of overtourism tied to the arrival of cruise ships) occurs when tourists arrive at the destination and stay for several days, whereas overtourism in “rural towns” is often caused by one-day visitors who come from nearby big cities (in the Czech Republic, especially from Prague).

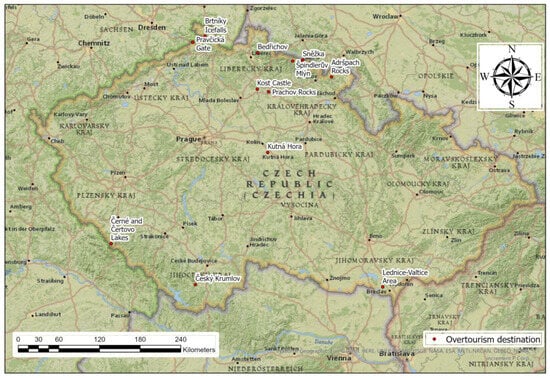

These destinations are Adršpach Rocks, Bedřichov, Brtníky Icefalls, Černé and Čertovo Lakes, Český Krumlov, Kost Castle, Kutná Hora, Lednice-Valtice area, Prachov Rocks, Pravčická Gate, Sněžka, Špindlerův Mlýn. These are some of the most famous tourist destinations in the Czech Republic, where the manifestations of overtourism can be observed over a long period of time (sometimes across many decades). The selection of destinations proceeded in such a way that certain negative impacts of overtourism were first identified in certain types of destinations. Those where these negative impacts were manifested with the highest intensity were then selected (typically, with exceptions, it was the best-known and most visited destinations from the selection). The selection was composed in such a way that, on a relatively small sample of destinations, the application of the toolkit was demonstrated on as diverse a set of destinations as possible, while representing all types of manifestations of overtourism (except big city overtourism, which manifests itself in Prague) that occur in the Czech Republic. Figure 1 shows the location of all destinations on the map of the Czech Republic.

Figure 1.

Location of the analyzed sites on the map of the Czech Republic. Source: own work, map data from Esri.

To better understand the results of the analysis, it is necessary to know the local context of each destination, especially in terms of the origin of overtourism and its manifestations. Therefore, a brief description of each destination is provided below:

The Adršpach Rocks is probably the most beautiful sandstone town in the Czech Republic with stone towers up to 90 m high. It is located in the Broumovsko Protected Landscape Area and the Broumovsko National Geopark and is protected as a National Nature Reserve, which is the highest level of protection in the Czech nature protection system. Due to the ever-increasing number of visitors to the site (around 400,000 visitors per year [,,,,,]), traffic congestion on the access roads and queues of people in the narrow gorges between the rocks are a problem. In response, the municipality has introduced a compulsory reservation system, limiting the maximum number of visitors to 4000 per day []. Overtourism occurs especially during the summer holidays (July and August) and public holidays.

Bedřichov is the most visited destination in the Jizera Mountains, which are considered as the best location for cross-country skiing in the Czech Republic. Bedřichov is home to a number of accommodation facilities and several ski slopes, and especially to several starting points for groomed cross-country skiing trails. The period of manifestations of overtourism is the winter season, when snow conditions are suitable (December–February) when traffic congestion occurs on access roads, public transport collapses and parking lots are overcrowded. The region of the Jizera Mountains is visited annually by more than 2 million visitors [], roughly half of whom stay in the vicinity of Bedřichov.

Brtníky Icefalls (see Figure 2A) are a natural attraction in the Czech Switzerland National Park. They are formed during the alternating periods of snow melting and freezing (usually February and March), when huge icicles resembling frozen waterfalls are formed. If the weather conditions are favorable and impressive icefalls form, hundreds of cars per day head to the destination, which is hardly visited at all most of the year. Due to the scarcity of official parking, illegal parking occurs, often directly on the access roads, creating traffic congestion and dangerous situations. This situation damages the nature in the national park and frustrates local residents. The site is also part of the proposed Neisseland Geopark [], which would support sustainable tourism in the area. The estimated number of visitors during the three months when the icefalls exist is about 100,000.

Figure 2.

Photos of selected analyzed sites: (A) Brtníky Icefalls–Velký Sloup Icefall, (B) Český Krumlov, (C) Kost Castle. Photos by author.

Černé and Čertovo Lakes are unique natural sites in the Šumava National Park. They are lakes of glacial origin, which are among the most visited sites in the national park. The ecosystem of the lakes is very fragile, therefore swimming is forbidden and visitors are only allowed in a restricted zone near the hiking trail. Unfortunately, also due to too many visitors during the main summer season, there are violations of regulations and visitors moving outside the designated areas, thus damaging the surrounding nature. The large number of visitors (about 2 million per year in the whole national park [,,,,,]) creates a strong anthropogenic pressure on the local ecosystems.

Český Krumlov (see Figure 2B) is one of the most famous rural locations in the Czech Republic, with the historic town center, which has a medieval character, and the adjacent castle and chateau with its gardens being visited. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Český Krumlov is a popular destination for day trips for foreign tourists arriving by bus from Prague. The castle and chateau alone has a visitor traffic of around 400,000 tourists per year [,,,,,], the town center alone at least double that. Overtourism results from the overcrowding of the narrow medieval streets by tourists, problems with traffic congestion and parking (partially solved in recent years via a system of collector car parks and limiting the number of arriving buses), and the displacement of local residents from the city center. Overtourism occurs here virtually all year round.

Kost Castle (see Figure 2C) is one of the most famous medieval castles in the Czech Republic, located in the Bohemian Paradise Protected Landscape Area and the UNESCO Global Geopark Bohemian Paradise. The castle is located in a valley sandwiched between sandstone rocks, so there is not much space for parking, and there are naturally valuable wet meadows right next to the castle, which are protected by the reserve. Due to the relatively small carrying capacity, overtourism occurs during the peak summer season, when traffic congestion, parking problems, and very long waiting times for tours negatively affect the visitor experience. The large number of tourists also poses a risk to the valuable surrounding nature. Although the absolute number of visitors is around 80,000 [,,,,,], even this amount is critical for a relatively small area.

Kutná Hora (see Figure 3A) is a similar type of locality to Český Krumlov, again it is a historic town whose urban conservation area is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. However, the historic center is not as tightly packed and the most visited monuments are spread over a larger area. As a result, the streets are not as intensely crowded with tourists and overtourism is usually only seen in the peak summer season. Its manifestations are traffic congestion, parking problems, and the frustration of local residents. Kutná Hora receives around 1 million visitors per year [,,,,,], the vast majority of whom come for day trips.

Figure 3.

Photos of selected analyzed sites: (A) Kutná Hora, (B) Lednice-Valtice area–Lednice Chateau, (C) Prachov Rocks, (D) Pravčická Gate–state before the forest fire in 2022. Photos by author.

The Lednice-Valtice area (see Figure 3B) is a 283 km2 landscape complex, which is considered to be the most extensive composite landscape in Europe and possibly in the world. The area was formed into a nature park by the Princely House of Liechtenstein during the 18th and 19th centuries and includes many cultural and natural monuments. The whole area is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The access points are the municipalities of Lednice and Valtice, where overtourism occurs during the peak summer season, especially manifested through traffic congestion and parking problems. Visitation to the site is around 400,000 paying visitors [,,,,,], but most of the site is accessible without payment, so the number of visitors will be significantly higher. The small cultural monuments, of which there are dozens, are also suffering from the high numbers of tourists.

Prachov Rocks (see Figure 3C) is one of the most popular natural sites in the Czech Republic, known from many films, TV series and popular songs. It is a sandstone town, much sought after by climbers, which is especially in the summer season a popular place for day trips. Overtourism manifests itself in congestion in the collector car parks, traffic congestion on the access roads, as well as congestion on the hiking trails, especially around the viewpoints. The annual number of visitors to the site is 250,000 during the period when the entrance fee is paid (summer season) [,,,,,], but the number of visitors is at least double all year round.

Pravčická Gate (see Figure 3D) is the largest rock gate in Central Europe. It is located in the Czech Switzerland National Park and thanks to its uniqueness, is a popular tourist destination. Due to its accessibility from Prague, it is a popular destination for day trips for foreign tourists, together with the gorges of the Kamenice River and the Bastei rock bridge in neighboring Saxony. These day trips in particular cause overtourism, with the local transport infrastructure overloaded and the rock gate itself damaged by man-made erosion. Until 1982 it was possible to walk on the rock arch, after which it was forbidden for safety reasons, as it was in danger of collapsing []. Visitation to the site is about 250,000 paying visitors per year [,,,,,], with at least another 100,000 viewing the site without completing the paid section. In 2022, the area around Pravčická brána was affected by a large forest fire, which made access to this natural monument impossible for several months.

Sněžka is the highest mountain in the Czech Republic, located on the border with Poland. It is located in the Krkonoše Mountains, a border mountain range very popular as a destination for trips on both sides of the border. In the upper parts of the Krkonoše Mountains there are very valuable relics of the northern tundra, which is why the entire mountain range is protected in the Czech Republic and Poland as a national park. However, the number of tourists heading to the mountains is enormous, in the order of several million per year, with more than 1 million visitors per year to Sněžka alone [,,,,,]. Overtourism is present in the area almost all year round, and is damaging the valuable natural ecosystems. The Czech National Park Authority is therefore trying to direct visitors to clearly defined corridors, bounded by ropes and nets, in order to protect the surrounding nature.

Špindlerův Mlýn is a small town about 10 km from Sněžka, which is the gateway to the Krkonoše National Park, although the built-up area of the town is not within it. It is the largest winter resort in the Czech Republic, but it is popular all year round. Due to the relatively large capacity of the tourist infrastructure, overtourism occurs only in the winter season, when car queues form on the access road to the town and there are long queues on the ski slopes. However, the overcapacity of the tourist infrastructure puts a significant strain on the surrounding mountain nature. More than 1.3 million visitors visited Špindlerův Mlýn in 2022 [], and their number is still growing.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Toolkit to Reduce the Negative Impacts of Overtourism

In the first phase of the research, different approaches to dealing with overtourism were identified and grouped into the eight categories listed below (T1–T8). The method by which these approaches were identified is described in detail in a separate article []; it was quite complicated, so only a summary of the original ten-page text is presented here. In the first phase, the manifestations of overtourism in the Czech Republic (except Prague) were mapped. Mapping was carried out based on the analysis of media reports (with localities mentioned in connection with overtourism), analysis of visitor evaluations of destinations (evaluations on the Google Maps and Mapy.cz portals, which are the most widespread in the Czech Republic, were used), and field research (verification of whether there really are manifestations of overtourism in the above-mentioned destinations and what local actors are doing about this situation). In this way, 146 destinations where objective overtourism is (or was) manifested, were selected.

In the second step, it was mapped in these destinations how local actors responded to overtourism and whether their efforts were successful. In order to obtain this information, interviews were conducted with local residents, mayors of municipalities, entrepreneurs, and other relevant actors. Successful methods were recorded that have helped to improve or alleviate the situation in destinations affected by overtourism. The method had to have some clear result (e.g., reducing the traffic load, alleviating the frustration of local residents). The successful methods were grouped into the eight categories below in the final step.

Each approach is briefly described below:

T1—Implementation of a tourism quota or cap: this involves limiting the number of tourists that can visit a particular destination at any given time. It is most often applied in valuable natural sites where large numbers of tourists may cause damage to the site. The most famous case of its use is the Galapagos archipelago, where the introduction of tourist quotas has helped to stabilize local ecosystems []. However, it is also common in various national parks or on various treks through these areas. It is of course easier to apply in areas where there are few possible inputs, which is certainly not the case in the Czech landscape. However, it is also used in the Czech Republic, for example, the case of the Adršpach Rocks [] is well known in the media, where, according to the local nature protection professionals, its introduction helped to solve the long-standing problematic situation with the influx of tourists on summer weekends.

T2—Regulation of accommodation possibilities: control of the number of accommodation places in mass accommodation facilities. Most often this involves regulating the number of hotel rooms, holiday rentals and other accommodation options that are officially listed as holiday facilities. Very widespread in many cities or coastal resorts, the most famous case is probably Barcelona, which stopped allowing the construction and creation of new accommodation facilities (especially hotels) [,]. However, the reaction to this has been a huge boom in so-called short-term rentals (AirBnB is a typical representative), i.e., services that are not officially registered as tourism, although in practice they are the same. In response, Barcelona has also tried to limit this type of business, but not very successfully []. In urban destinations, therefore, the introduction of such measures is somewhat controversial, while similar regulation is much more successful in less populated natural or rural areas where there is not as much housing stock available for short-term rentals. In the Czech Republic, this type of regulation exists only in the form of regulatory measures in national parks or limits set in municipal plans.

T3—Introduction of a tourist tax or fee: this is a fee that tourists have to pay to visit a destination and can be used to finance tourism infrastructure and local initiatives. From the perspective of combating overtourism, this fee should be large enough to discourage at least some tourists from visiting the destination, which targets the quality of the experience (or rather the movable visitors) and not the quantity. Such high fees are typical of some popular African national parks, but in Europe they tend to be destinations where the number of potential visitors is limited for capacity reasons. In the Czech Republic, accommodation fees are compulsory, but due to their low level they do not influence tourists’ decision-making. Entrance fees are included in the entrance to some areas owned by municipalities or private individuals, such as Prachov Rocks or Adršpach Rocks. However, this is a form of entrance fee rather than a tool to reduce the number of tourists.

T4—Strengthening tourism infrastructure: many problematic situations arise because many destinations are ill-prepared for the increasing number of visitors [,]. Therefore, some strategies use an element that seemingly contributes to the growth of tourism in a destination (which may not be a bad thing after all), but in reality, addresses a situation that is resented by local residents—typically tourist parking at the homes of local residents or traffic congestion on access roads. Through the building of appropriate infrastructure, many of the negative impacts of mass tourism can be counteracted while improving the quality of the visitor experience. In addition to a number of examples from abroad, sites in the Czech Republic such as Malá Skála or Polevsko can be mentioned, where the construction of new car parks has helped to calm the situation in the area. In some cases, there is a combination with the T1 tool, where new infrastructure is built at the same time, but at the same time a certain ceiling is applied (e.g., the number of buses arriving in Český Krumlov).

T5—Appropriate separation of functions: subjectively perceived overtourism often manifests itself in the negative reactions of locals to the presence of tourists in a destination, based on the different priorities and daily rhythms of the two groups. The spatial separation of functions in the destination that serves tourists from those that serve locals is already a good practice in the construction of tourist infrastructure in the destination. Examples are tourist resorts around the world that are separated from local developments so as not to disturb local residents. Although this practice in developing countries is more likely motivated by the desire for an undisturbed stay in a tourist bubble, unencumbered by the sight of the dismal living conditions of the local population, in developed countries, including the Czech Republic, it is more about the creation of specialized zones (campsites on the edge of the village, cottage villages, etc.) separated from the residential buildings of the local population [,,]. In terms of use in the Czech Republic, the key document is the municipal master plan.

T6—Promoting Sustainable Tourism: includes the promotion of activities and accommodation that minimizes environmental impact and supports local communities. In general, this involves supporting activities that are not mass in nature, do not threaten the local environment and do not inconvenience local residents. The shift from mass to sustainable tourism is particularly visible in valuable natural sites or small communities that could be destroyed by the influx of tourists. Sustainability should also be seen in the context of the lifespan of tourist infrastructure—many elements of tourist infrastructure are built to be nice to look at, but after a few years they reach the end of their lifespan and there is no money to renew them. It is therefore better to choose more durable materials that will last longer.

T7—Encouraging off-season travel: as overtourism in European non-urban regions only occurs during the peak summer and/or winter season, the rest of the year is a kind of quiet period that has the potential to accommodate additional visitors without negatively affecting the destination. Thus, some strategies encourage tourists to visit destinations in the low season, when there are fewer visitors and the impact on local communities is reduced. This usually involves a change in the marketing of the tourist region, where the beauty of the off-season is promoted (in the Czech Republic, especially autumn images) and tourists are motivated by lower fees for accommodation or services, etc. There is even a worldwide movement of travelers who visit well-known destinations when there are relatively fewer tourists and then share their experiences about the best time to visit with others on the internet—just type the keyword “off-season travel” into a search engine.

T8—Promoting alternative destinations: motivating tourists to visit less crowded destinations that are often overlooked in favor of more popular destinations. A very popular strategy worldwide is to offer similar, lesser-known destinations to tourists visiting well-known locations. In practice, the results of this strategy are questionable, as over-touristed locations usually remain overcrowded and mass tourism overwhelms less visited locations. In the Czech Republic for example, the Bohemian Paradise Protected Landscape Area pursued this strategy for a period of time before discovering that the most visited sites did not improve and, on the contrary, problems with mass tourism arose in sites that were promoted as an alternative. However, the strategy can be effective if it targets day tourists (usually residents of the region) who may decide to visit a new, previously unknown destination rather than a well-known but sought-after one.

2.2. Evaluation of the Usefulness of the Toolkit in Developing A Strategy for Mitigating the Negative Effects of Overtourism

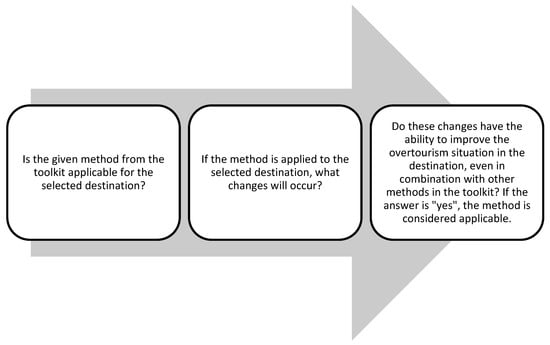

In the first phase of the evaluation (see Figure 4), the method (using the toolkit) was applied to each of the 12 selected destinations. This took into account whether the tool would bring any real improvement in the situation caused by the manifestations of overtourism or not. Therefore, the application of the selected tool should target the specific negative situation in the destination and should not be just a general declamation, e.g., the promotion of sustainable tourism (T6) is of course suitable for any location at any time, but its use within the toolkit is only implemented if it can mitigate the specific impacts of overtourism.

Figure 4.

Diagram of the evaluation process of individual toolkit methods for the selected destination.

After a strategy for mitigating the negative impacts of overtourism using the above toolkit was developed for each site, the results were given to 30 experts for review, 10 of whom were tourism professionals, 10 were representatives of local and regional authorities, and 10 were nature and landscape conservation experts. These 30 respondents were asked to study the strategies developed and to rate each of them on a scale of 0 (minimum) to 10 (maximum) in the following areas:

- Ability to overcome the negative effects of overtourism in the destination;

- The adequacy of the solution in terms of resources;

- Feasibility of the strategy.

They then wrote a free commentary on the strategy in the form of a text string of maximum 5000 characters. Data collection took place between March and June 2023, after which the data was evaluated. The result was a numerical rating for the three variables mentioned above and a text string for the free comment. The data was processed in the Microsoft Excel program. In the case of the free comments, the content was qualitatively coded with superordinate words for greater clarity and speed of searching in the data.

3. Results

The first phase of the research identified suitable tools that could be part of the resulting strategy. For each of the eight tools described above, it was considered whether or not its introduction in the destination would lead to a concrete improvement in the negative impacts of overtourism. Subsequently, it was assessed whether the proposals for the use of each tool also made sense as a whole, i.e., whether they formed a comprehensive and meaningful strategy. The suitability of the proposal was assessed on the basis of a good knowledge of the destination (each destination was visited at least once as part of the field research) and the data was obtained by the author in interviews with local residents, mayors, and entrepreneurs. The resulting proposals are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Use of individual tools from the toolkit for selected destinations.

The results show that in each destination at least one tool could be applied to improve the current situation, i.e., that a solution was found everywhere. Due to the specific conditions in each destination, which cannot be described in detail within the scope of the article, the resulting strategies are only roughly outlined. In Adršpach Rocks, T1 and T3 tools have already been introduced in recent years, which should be complemented by the promotion of sustainable forms of tourism, focusing on the quality of the experience and longer stays in the destination, and the promotion of travel outside the high season when there are significantly fewer visitors. A similar type of natural destination is Prachov Rocks and Pravčická Gate, where the same approach is recommended as for Adršpach Rocks. The same strategy has been proposed for Bedřichov and Špindlerův Mlýn, although they are slightly different types of location (Bedřichov is a base for cross-country skiing, Špindlerův Mlýn is a center for alpine skiing). This strategy is based on regulating accommodation options and promoting alternative destinations in the area. A specific kind of destination is Brtníky Icefalls, where tourist infrastructure is practically absent. Here it was recommended to build tourist infrastructure (especially parking lots) and at the same time to separate the tourist area from the residential areas appropriately. Černé and Čertovo Lakes have a similar strategy as proposed for Adršpach Rocks, only here it is not possible to regulate the tourist quota. For the historic towns of Český Krumlov and Kutná Hora, a strategy has been proposed that emphasizes the strengthening of tourist infrastructure, but also encourages off-season travel. A specific destination is Kost Castle, where a number of measures cannot be implemented due to lack of space, therefore it was recommended to apply a tourist quota and promote alternative destinations in the vicinity that offer the same experience. For the Lednice-Valtice Area, an approach has been taken that both charges for entry to the whole area, and tries to encourage visitors to stay longer with a more intensive experience. The last destination is Mount Sněžka, where, due to the severe overcrowding of the peak, the greatest regulations (tourist quota and entrance fees) would separate visitors from the valuable ecosystems and place emphasis on the durability of the infrastructure.

In the second phase of the research, the proposed strategies were sent to 30 selected experts to comment on them in terms of: (a) their ability to overcome the negative effects of overtourism in the destination, (b) the adequacy of the solution in terms of resources, and (c) the feasibility of the strategy. The results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Average rating of the proposed strategies by respondents.

The results of the evaluation of the proposed strategies show that respondents rated these strategies quite favorably, with all scores exceeding 6. For the first indicator, it can be seen where the situation with overtourism is relatively easy to solve (Brtníky Icefalls) and where, on the contrary, it is so complex that respondents do not trust the proposed solution so much (Sněžka). For the second indicator, the results differed mainly depending on whether the most financially demanding tools were used (T4 and T5) or only some of the cheaper ones. The third indicator took into account local conditions, in particular, where even a well-designed strategy may be rejected due to different interests of key actors, etc. Overall, the best performing destination was the Brtníky Icefalls, as overtourism occurs only during a very limited part of the year and even small investments in infrastructure could yield very positive results here. On the other hand, the situation was most difficult on Mount Sněžka, which is extremely visited, lies on the border with Poland, and has a high conflict of interests between visitors and nature conservation.

Respondents wrote a comment on each strategy, specifying whether they believed in the solution or whether they saw something wrong with it. In total, there were 182 such comments (out of 360 possible), most of them quite short. The comments were grouped according to the message they conveyed, and their frequency is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

The most common types of comments on proposed strategies.

The most frequently mentioned problems in implementing the strategies were conflicts between local actors, lack of political will, or problems with ownership of the land on which the new infrastructure would be built. The financial complexity of some of the solutions was also a significant factor, which in the case of smaller municipalities was an important factor as to why various solutions had not been implemented for a long time. In some cases, it was mentioned that overtourism was not a priority for the destination or that implementation was hindered by a strong pro-tourist lobby, mostly represented by hotel owners, service providers, etc. Several comments were quite long, as the selected experts knew the area perfectly or even work in it. As not all respondents knew all destinations in detail, comments were missing for some strategies. However, there were at least 11 comments for each destination.

4. Discussion

Overall, the feedback from the experts confirmed that the proposed toolkit can be used for many types of sites. When it comes to the objective evidence of overtourism, manifested in the collapse of transport and tourism infrastructure, displacement of local residents by visitors, damage to nature, noise, litter, etc., it is necessary to identify the problem and then target a solution in the form of a tool from the toolkit. In addition, the results show that similar strategies have been proposed for similar locations, so it is possible to draw inspiration from suitable solutions in other destinations. For all the selected destinations it was possible to find a solution that at least theoretically can solve the problem of overtourism (however, experience from other destinations in the Czech Republic shows that it can also solve it practically, e.g., in the small historic town of Telč, in the caves in the Moravian Karst, or at the UNESCO monument Pilgrimage Church of St. John of Nepomuck on Zelená hora). This contrasts with the results of other articles that were skeptical about overcoming overtourism []. However, the nature of the destinations studied must be taken into account, as they are not world-famous tourist destinations, such as Prague, Barcelona or Amsterdam, and a significant part of the demand is from domestic visitors, whose numbers are not growing at such a dizzying pace.

Of course, a limitation of the method is that it cannot always respond adequately to situations where objective manifestations of overtourism are almost non-existent in a destination, but local residents are frustrated by visitors and refer to the situation as overtourism. In such cases, it is necessary to consider whether there may be some manifestation of overtourism or whether it is more likely to be the inappropriate behavior of a small number of visitors or the intolerance of some local residents. Indeed, tourism can also be a target of the NIMBY effect [,,], where everyone likes to travel but some people do not like other people around their home. In some cases, local residents became accustomed to relative calm during 2020–2021, when due to the introduction of quarantine measures in connection with the global pandemic of COVID-19, tourism was significantly reduced. After the number of visitors returned to their original levels in 2022 in most locations in the Czech Republic, some local residents were frustrated by this.

It is also worth mentioning what is missing in the developed toolkit, although these were the approaches used and are widely referenced in the literature. Firstly, reducing the promotion of the destination, which is seen as a great tool for tourism degrowth [,,,,]. However, as it turns out, it can work for lesser-known destinations, but certainly not for destinations affected by overtourism, because everyone already “knows” them, everyone wants to visit them, and the disappearance of marketing does nothing to reverse this trend. An example outside of the Czech Republic is the Blue Lagoon in Iceland [], which is not promoted in any way, yet it is one of the most visited destinations on the island and tickets must be booked many days in advance during the season. If the destination is well known to the public, appears in all tourist guides, and there are a dizzying number of photographs of it on the internet, reducing the promotion of the destination has no impact on visitor behavior.

The second measure that does not work is information boards highlighting bans and regulations. Many visitors do not respect them [,]. When a rule is introduced, it must be enforceable, so there must be a mechanism to sanction or prevent transgressions. The best regulation is then the physical form of the tourist infrastructure itself. If the railings are sufficiently impenetrable and the platform is at a height above the terrain that it is not possible to descend comfortably to the surface, hikers will stay on the trail and not damage the surrounding valuable ecosystems. The recklessness of hikers is an important issue, but unfortunately it can only be combated in the long term through appropriate environmental education [,,,,].

A third approach not included in the toolkit is, “if there is no infrastructure, there are no visitors”. Unfortunately, even in this case it cannot be said that the absence of infrastructure would in any way deter tourists from visiting the destination. On the contrary, in this case, visitors will start to devise solutions to enable them to carry out their planned trip, which often leads to conflicts with the local population. In the Czech Republic, however, the situation with overtourism is not satisfactorily addressed on a regional or national scale, and a destination that admits that overtourism is occurring there is faced with the situation that it will not receive money to build additional tourist infrastructure on the grounds that it does not want more visitors. This hypocritical attitude was also mentioned by one respondent in his answer:

“The main problem is that when the locals started to say that there are problems with tourists and that there are too many tourists here, the regional authority reacted by stopping sending money to promote tourism, saying that we don’t want more visitors here. But how are we supposed to attract tourists to events in the off-season, offer alternatives in the area, expand the existing tourist infrastructure and so on if the flow of funds has stopped? If it was about transport infrastructure, it wouldn’t happen. Hardly anyone is going to respond to highway congestion by letting the highway fall into disrepair and saying that motorists will learn to drive the other way.”

Although the three approaches mentioned above are used in the world to fight overtourism, in the locations selected for this study their potential application would not bring any positive improvement. In addition, we have not identified any location affected by overtourism where their application would make sense in the entire territory of the Czech Republic. However, this may be due to the different cultural environment in different regions of the world; see limitations of the study in the Conclusions chapter.

5. Conclusions

The above-mentioned toolkit presents a process to eradicate or reduce the negative impacts of overtourism in a destination. Compared to the current approaches applied in the Czech Republic, it is characterized by the fact that it tries to address the problems through different approaches, which together form a sophisticated strategy. The field research has shown that although many destinations are able to respond to the current situation of overtourism with adequate measures, these measures are rarely based on a comprehensive strategy that takes into account not only the current situation but also the estimation of future developments. It is due to this fact that the measures taken often have only a temporary effect or are not supported by other appropriate steps to mitigate the negative impacts of overtourism.

Tourism is a social phenomenon that brings economic recovery even to regions that are far from major cities and other economic centers [,,]. A significant part of the popular tourist destinations in the Czech Republic are located in peripheral locations (see Figure 1 in regions where the border effect is negatively manifested [,]). If it were not for tourism, these would be very poor regions. Therefore, the sector needs to be able to overcome the problems caused by the concentration of large masses of visitors in space and time, which manifests itself as overtourism []. The proposed toolkit could thus help destinations not only in Central Europe to overcome this “disease” and steer the destination towards sustainable development. Based on the research results, it can be concluded that the goal of the article has been achieved, as the toolkit can be used to mitigate the negative effects of overtourism. However, there are also limitations to the use of the results of this study, which are listed below.

The primary limitation lies in the challenge of generalizing findings beyond the selected 12 rural locations. Overtourism manifests differently based on diverse geographical, cultural, and economic contexts. Therefore, conclusions drawn from a specific set of rural areas may not be universally applicable, limiting the external validity of the study. The study’s temporal scope may introduce limitations regarding the dynamic nature of overtourism. A snapshot approach focused on specific periods might not encapsulate seasonal variations or long-term trends, impacting the comprehensiveness of the analysis.

The study’s confined scope may hinder the ability to conduct meaningful comparative analyses. Comparisons across different countries or regions could provide a more nuanced understanding of overtourism dynamics and mitigation strategies, contributing to a broader theoretical framework.

The effectiveness of mitigation strategies heavily relies on stakeholder engagement. A study confined to 12 rural locations may not adequately capture the perspectives and interests of diverse stakeholders, including local communities, businesses, and government entities, potentially limiting the robustness of proposed solutions.

The study’s geographic specificity may lead to language and cultural considerations that impact the applicability of findings beyond the Czech Republic. Cultural nuances, regulatory frameworks, and community dynamics may differ significantly in other regions, affecting the transferability of proposed mitigation strategies.

In conclusion, while this study provides valuable insights, researchers must acknowledge the limitations related to generalizability, temporal constraints, comparative analysis, stakeholder representation, and cultural considerations. Recognizing these constraints is crucial for both the academic rigor of the study and the informed application of its findings in broader contexts.

Funding

This research was funded by the Technology Agency of the Czech Republic, grant number TL03000020, project name “Proactive solutions to the negative effects of overtourism”. The author also expresses its gratitude to the Technical University of Liberec, which is co-financing this project.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The author declares that the study was conducted in accordance with the ethical rules that are generally accepted for questionnaire surveys in humanities research.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request from the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Cheer, J.M. Overtourism and Tourismphobia: A Journey Through Four Decades of Tourism Development, Planning and Local Concerns. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2019, 16, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phi, G.T. Framing overtourism: A critical news media analysis. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 23, 2093–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, V.M.; Coromina, L.; Gali, N. Overtourism: Residents’ perceptions of tourism impact as an indicator of resident social carrying capacity-case study of a Spanish heritage town. Tour. Rev. 2018, 73, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R.; Butler, R. The phenomena of overtourism: A review. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2019, 5, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohac, A.; Drapela, E. Overtourism Hotspots: Both a Threat and Opportunity for Rural Tourism. Eur. Countrys. 2022, 14, 157–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Cheer, J.M. Overtourism and degrowth: A social movements perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1857–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K.S.; Li, L.H. Understanding visitor-resident relations in overtourism: Developing resilience for sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1197–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhati, A.; Upadhayaya, A.; Sharma, A. National disaster management in the ASEAN-5: An analysis of tourism resilience. Tour. Rev. 2016, 71, 148–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R.; Graci, S.R.; Holmes, M. Does the tourist care? A comparison of tourists in Koh Phi Phi, Thailand and Gili Trawangan, Indonesia. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkumiene, D.; Pranskuniene, R. Overtourism: Between the Right to Travel and Residents’ Rights. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drapela, E. Prevention of damage to sandstone rocks in protected areas of nature in northern Bohemia. AIMS Geosci. 2021, 7, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drapela, E.; Bohac, A.; Bohm, H.; Zagorsek, K. Motivation and Preferences of Visitors in the Bohemian Paradise UNESCO Global Geopark. Geosciences 2021, 11, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrill, R. Residents’ attitudes toward tourism development: A literature review with implications for tourism planning. J. Plan. Lit. 2004, 18, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, V.; Pires, S.M.; Costa, R. A strategy for a sustainable tourism development of the Greek Island of Chios. Tourism 2020, 68, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambarota, D.M.; Lorda, M.A. Tourism as a strategy for local development. Rev. Geogr. Venez. 2017, 58, 346–358. [Google Scholar]

- Vu, H.M.; Ngo, V.M. Strategy development from triangulated viewpoints for a fast-growing destination toward sustainable tourism development—A case of Phu Quoc islands, Vietnam. J. Tour. Serv. 2019, 10, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, M.S.; Zaragoza, M.P.P. Analysis of the Accommodation Density in Coastal Tourism Areas of Insular Destinations from the Perspective of Overtourism. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazquez-Salom, M.; Cladera, M.; Sard, M. Identifying the sustainability indicators of overtourism and undertourism in Majorca. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 1694–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, T.; Berselli, C.; Pereira, L.A.; Limberger, P.F. Overtourism: An Analysis of Demographic and Socioeconomic Factors with the Evasion Indicators of Residents in Brazilian Coastal Destinations. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2022, 19, 526–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogowski, M. A method to analyze variability and seasonality the visitors in mountain national park in period 2017–2020 (Stolowe Mts. National Park; Poland). J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2021, 35, 100407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, F.; Jeong, Y.; Putri, I.; Kim, S.I. Sociopsychological Aspects of Butterfly Souvenir Purchasing Behavior at Bantimurung Bulusaraung National Park in Indonesia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barac-Miftarevic, S. Undertourism vs. Overtourism: A Systematic Literature Review. Tourism 2023, 71, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capocchi, A.; Vallone, C.; Pierotti, M.; Amaduzzi, A. Overtourism: A Literature Review to Assess Implications and Future Perspectives. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W.; Dodds, R. Overcoming overtourism: A review of failure. Tour. Rev. 2022, 77, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowreesunkar, V.; Seraphin, H. Conclusion: Local communities’ quality of life: What strategy to address overtourism? Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2019, 11, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, M. Overcoming overtourism in Europe: Towards an institutional-behavioral research agenda. Z. Wirtsch. 2020, 64, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postma, A.; Schmuecker, D. Understanding and overcoming negative impacts of tourism in city destinations: Conceptual model and strategic framework. J. Tour. Futures 2017, 3, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, G. From carrying capacity to overtourism: A perspective article. Tour. Rev. 2020, 75, 212–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. Tourism carrying capacity research: A perspective article. Tour. Rev. 2020, 75, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeporsdottir, A.D.; Hall, C.M.; Wendt, M. Overtourism in Iceland: Fantasy or Reality? Sustainability 2020, 12, 7375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, K.; McCool, S.F. A critique of environmental carrying capacity as a means of managing the effects of tourism development. Environ. Conserv. 1998, 25, 291–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szuster, B.; Needham, M.D.; Lesar, L.; Chen, Q. From a drone’s eye view: Indicators of overtourism in a sea, sun, and sand destination. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 1538–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertocchi, D.; Camatti, N.; Giove, S.; van der Borg, J. Venice and Overtourism: Simulating Sustainable Development Scenarios through a Tourism Carrying Capacity Model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llausas, A.; Vila-Subiros, J.; Pueyo-Ros, J.; Fraguell, R.M. Carrying Capacity as a Tourism Management Strategy in a Marine Protected Area: A Political Ecology Analysis. Conserv. Soc. 2019, 17, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, F.; Viviano, G.; Manfredi, E.C.; Caroli, P.; Thakuri, S.; Tartari, G. Multiple Carrying Capacities from a management-oriented perspective to operationalize sustainable tourism in protected areas. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 128, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasquinelli, C.; Trunfio, M. Reframing urban overtourism through the Smart-City Lens. Cities 2020, 102, 102729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontanari, M.; Traskevich, A. Smart-Solutions for Handling Overtourism and Developing Destination Resilience for the Post-COVID-19 Era. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2023, 20, 86–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trunfio, M.; Pasquinelli, C. Smart technologies in the COVID-19 crisis: Managing tourism flows and shaping visitors’ behaviour. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 29, 2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Hernandez, M.; Ivars-Baidal, J.; de Miguel, S.M. Overtourism in urban destinations: The myth of smart solutions. Bol. Asoc. Geogr. Esp. 2019, 83, 2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, A.T. Venice: The problem of overtourism and the impact of cruises. Investig. Reg.-J. Reg. Res. 2018, 42, 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaderi, Z.; Hall, M.C.M.; Ryan, C. Overtourism, residents and Iranian rural villages: Voices from a developing country. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour.-Res. Plan. Manag. 2022, 37, 100487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R. Measuring tourism success: Alternative considerations. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2022, 14, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulsen, U.; Yolcu, H.; Ataker, P.; Ercakar, I.; Acar, S. Counteracting Overtourism Using Demarketing Tools: A Logit Analysis Based on Existing Literature. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakar, K.; Uzut, I. Exploring the stakeholder’s role in sustainable degrowth within the context of tourist destination governance: The case of Istanbul, Turkey. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 917–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Miguel, S.M.; Vaquero, M.D.; Parra, B.M. Managing overtourism in historic centers through demarketing. Investig. Tur. 2023, 25, 196–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Wood, K.J. Demarketing Tourism for Sustainability: Degrowing Tourism or Moving the Deckchairs on the Titanic? Sustainability 2021, 13, 1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Changing Paradigms and Global Change: From Sustainable to Steady-state Tourism. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2010, 35, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drapela, E. Causes of overcoming overtourism failure in Czechia. In Public Recreation and Landscape Protection—With Sense Hand in Hand? Proceedings of the 14th Conference, Chiba, Japan, 10–14 May 2023; Fialová, J., Ed.; Mendel University in Brno: Brno, Czech Republic, 2023; pp. 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, U.; Barnes, S.J.; Abbasi, S.; Anjam, M.; Aktan, M.; Khwaja, M.G. The Bridge at the End of the World: Linking Expat’s Pandemic Fatigue, Travel FOMO, Destination Crisis Marketing, and Vaxication for “Greatest of All Trips”. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drapela, E. How to Deal with Overtourism without Regulations? In Topical Issues of Tourism, Proceedings of the 17th International Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 12–15 April 2023; Scholz, P., Ed.; College of Polytechnics Jihlava: Jihlava, Czech Republic, 2023; pp. 72–81. ISBN 978-80-88064-68-8. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, R.; Sequeira, A. Urban Art touristification: The case of Lisbon. Tour. Stud. 2020, 20, 182–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocola-Gant, A. Place-based displacement: Touristification and neighborhood change. Geoforum 2023, 138, 103665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, G.H.; Chen, Q.W. Tourism and inequality: Problems and prospects. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2021, 19, 732–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, L. Tourism, Consumption and Inequality in Central America. New Political. Econ. 2011, 16, 347–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CzechTourism. Visitation of Tourist Destinations in 2017 (Návštěvnost Turistických Cílů 2017). Available online: https://tourdata.cz/data/navstevnost-turistickych-cilu/ (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- CzechTourism. Visitation of Tourist Destinations in 2018 (Návštěvnost Turistických Cílů 2018). Available online: https://tourdata.cz/data/navstevnost-turistickych-cilu-2018/ (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- CzechTourism. Visitation of Tourist Destinations in 2019 (Návštěvnost Turistických Cílů 2019). Available online: https://tourdata.cz/data/navstevnost-turistickych-cilu-2019/ (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- CzechTourism. Visitation of Tourist Destinations in 2020 (Návštěvnost turistických Cílů 2020). Available online: https://tourdata.cz/data/navstevnost-turistickych-cilu-2020/ (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- CzechTourism. Visitation of Tourist Destinations in 2021 (Návštěvnost Turistických Cílů 2021). Available online: https://tourdata.cz/data/navstevnost-turistickych-cilu-2021/ (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- CzechTourism. Visitation of Tourist Destinations in 2022 (Návštěvnost Turistických Cílů 2022). Available online: https://tourdata.cz/data/navstevnost-turistickych-cilu-2022/ (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- The Adršpach Rocks. Available online: https://www.adrspasskeskaly.cz/en (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Liberec Region. Analysis of the Impacts/Benefits Resulting from Tourism in the Liberec Region. Available online: https://kultura.kraj-lbc.cz/page414/strategicke-dokumenty/analyza-navstevnosti-2020 (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Drapela, E.; Buechner, J. Neisseland Geopark: Concept, Purpose and role in promoting sustainable tourism. In Public Recreation and Landscape Protection—With Sense Hand in Hand; Fialová, J., Ed.; Mendel University in Brno: Brno, Czech Republic, 2019; pp. 268–272. ISBN 9788075096593. [Google Scholar]

- Safranek, J. Pravčická brána—The most watched rock gate (Pravčická brána—Nejsledovanější skalní brána). Ochr. Prir. 2017, 17, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- KRNAP. Analysis of Visitors to the Krkonoše National Park (Krnap) in 2022. Available online: https://www.krnap.cz/media/migd2min/analyza_navstevnosti_krkonos_rok_2022_31_3_2023-upraveno.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Burbano, D.V.; Meredith, T.C. Effects of tourism growth in a UNESCO World Heritage Site: Resource-based livelihood diversification in the Galapagos Islands, Ecuador. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1270–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elorrieta, B.; Schwitzguebel, A.C.; Torres-Delgado, A. From success to unrest: The social impacts of tourism in Barcelona. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2022, 8, 675–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Calle-Vaquero, M.; Garcia-Hernandez, M.; de Miguel, S.M. Urban Planning Regulations for Tourism in the Context of Overtourism. Applications in Historic Centres. Sustainability 2021, 13, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gralak, K. Tourism Gentrification as a Symptom of an Unsustainable Tourism Development. Probl. Zarz.-Manag. Issues 2018, 16, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, H.; Takizawa, A. Population Decline through Tourism Gentrification Caused by Accommodation in Kyoto City. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocola-Gant, A.; Lopez-Gay, A. Transnational gentrification, tourism and the formation of ‘foreign only’ enclaves in Barcelona. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 3025–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.F.; Lee, M.Y.; Wong, J.W.C. Assessing community attitudes toward industrial heritage tourism development. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2020, 18, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litwin, S.W.; Smith, W.W.; McEwen, W.R. Not in My Backyard: Personal Politics and Resident Attitudes toward Tourism. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 674–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Glanz, H. Identifying potential NIMBY and YIMBY effects in general land use planning and zoning. Appl. Geogr. 2018, 99, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drugova, T.; Kim, M.K.; Jakus, P.M. Marketing, congestion, and demarketing in Utah’s National Parks. Tour. Econ. 2021, 27, 1759–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.L.; Jeong, E.H.; Zhang, X.Y.; Jang, S.C. Green Marketing Versus Demarketing: The Impact of Individual Characteristics on Consumers’ Evaluations of Green Messages. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2023. early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blue Lagoon, Iceland. Available online: https://www.bluelagoon.com/ (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Loi, K.I.; Pearce, P.L. Annoying Tourist Behaviors: Perspectives of Hosts and Tourists in Macao. J. China Tour. Res. 2012, 8, 395–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairi, N.D.M.; Ismail, H.N.; Jaafar, S.M.R.S. Tourist behaviour through consumption in Melaka World Heritage Site. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 582–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drapela, E. Using a Geotrail for Teaching Geography: An Example of the Virtual Educational Trail “The Story of Liberec Granite”. Land 2023, 12, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, F.P. Environmental education and tourism: Methodologies for environmental education applied as tourist-recreational activities in natural settings. Tur.-Estud. E Prat. 2016, 5, 60–79. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.M.; Dai, J.L.; Dewancker, B.J.; Gao, W.J.; Liu, Z.Q.; Zhou, Y. Impact of Situational Environmental Education on Tourist Behavior—A Case Study of Water Culture Ecological Park in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toffolo, M.M.; Simoncini, G.A.; Marchini, C.; Meschini, M.; Caroselli, E.; Franzellitti, S.; Prada, F.; Goffredo, S. Long-Term Effects of an Informal Education Program on Tourist Environmental Perception. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 830085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drapela, E. Assessing the Educational Potential of Geosites: Introducing a Method Using Inquiry-Based Learning. Resources 2022, 11, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddulph, R. Limits to mass tourism’s effects in rural peripheries. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 50, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, E. Making sense of sustainable tourism on the periphery: Perspectives from Greenland. Tour. Geogr. 2022, 25, 1303–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, A.C. Tourism Development in a Rural Periphery. Case Study: The Sub-Carpathians of Oltenia. J. Settl. Spat. Plan. 2014, 3, 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Drapela, E.; Karnikova, N. Methodological issues of using the gravity model to determine the power of border effect. In Useful Geography: Transfer from Research to Practice; Masarykova Univerzita: Brno, Czech Republic, 2018; pp. 367–375. ISBN 978-80-210-8907-5. [Google Scholar]

- Drapela, E.; Basta, J. Quantifying the Power of Border Effect on Liberec Region Borders. Geogr. Inf. 2018, 22, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C. Critical tourism studies: New directions for volatile times. Tour. Geogr. 2021, 23, 659–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).