Abstract

Accessibility to the cultural heritage of museums is an inalienable right of all individuals. However, these places appear to be very unfriendly and unsustainable towards individuals with mobility, sensory, and cognitive difficulties, resulting in their exclusion from cultural heritage. The aim of the research was to examine the spatial and information accessibility in certain museums and places of historical interest in two culturally important European cities, London (Great Britain) and Thessaloniki (Greece). Fifteen museums in London and fifteen in Thessaloniki were visited and assessed thoroughly. The tools used were a) an extended checklist of accessibility criteria and standards developed in the context of the present research and b) a semi-structured interview. The results showed that the London museums are slightly more accessible than the museums in Thessaloniki, especially with reference to spatial accessibility. All participant museums should focus more on individuals with impairments other than physical/mobility since their main accessibility features appear to serve only mobility and navigation needs. Moreover, while the buildings of the recent past are more accessible, buildings that are listed or are themselves of historical interest are difficult to adjust. The results present which specific categories need to be urgently targeted and, thus, in which direction any corrective action towards accessibility should be placed. These findings are of great interest for all stakeholders in cultural accessibility and social inclusion.

1. Introduction

Disability is the result of the interaction between impairment and attitudinal or environmental barriers that exclude individuals with impairments from various aspects of social life [1]. As a result, inclusion seems to depend on the removal of all these barriers and social features that hinder social participation [2]. Over the past decade, individuals with disabilities have experienced exclusion from different aspects of social engagement and involvement in economic activities [3]. One of the primary areas in which those people faced exclusion was access to museums and historical sites [4,5]. Those places used to be very unfriendly and unsustainable to those individuals who had mobility, sensory, and cognitive difficulties [6,7].

At the beginning of the 21st century, the United Kingdom led the way in providing accessibility to the cultural heritage of museums, which is an inalienable right of all individuals regardless of any physical or cognitive disabilities they may have [8]. Accessibility to the cultural heritage of museums encompasses various dimensions, such as access to a museum’s space, access to information, and access to facilities [8,9,10].

All the European members have been called to enhance and ensure suitable and sustainable conditions for the participation of people with disabilities in various highly important areas of action including accessibility, public participation, equality, education, social protection, health, external action, and professional employment [1,11]. Accessibility contributes to develop sustainability in society and to provide equal opportunities among its citizens, which fully align with the principles of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially with Goal 10 (“Reduce inequalities within and among countries”) [12,13,14].

1.1. The Significance of Accessibility in the Museums

Museums are not merely institutions; they also serve the purpose of fulfilling the requirements of social well-being, social development, and inclusion [15]. A remarkable example is that in England, old disabled people from care houses and children with severe illnesses from hospitals have visited museums to gain that unique and alternative learning experience, meet new people, and enhance creative thinking [16].

Moreover, museums narrate a significant part of human history, identity, and its progress [17,18], and as such, they can equally be evaluated as educational institutions that are shaping modern society [19,20], and they provide life-long learning through non-formal education and a variety of unique learning experiences [21]. Indisputably, people who have the opportunity to visit different kind of museums could be considered as highly privileged since they have access to a huge quantity of multicultural heritage [22] and they delve deep into the aspects of traditions and historical events using the evidence found in exhibits [12].

The significance of museums and historical sites leads to the purpose to make these places accessible because inclusivity contributes to society’s sustainability [12,23,24]. Museum audiences should not be limited to a single homogeneous group, but they should rather be inclusive, while the diverse needs and preferences of individuals should be considered based on factors such as age, disability, origin, interests, and more [25,26].

However, many research studies such as [6,24,27] acknowledge the lack of accessibility in museums and highlight the need for improvement in order to promote equality and inclusivity. According to [28], some museums are still very unapproachable, especially the ones that display the prohibitive sign “Please do not touch the exhibits” without any alternative method of experiencing and processing them being offered [29,30]. As a result, many individuals with visual impairments do not have access to the information of such exhibits [30]. Those practices make people with disabilities miss the chance to participate in the unique learning experiences that museums can offer [3], lose the opportunity to interact and connect with other people [31], feel isolated, and be socially excluded [32]. Therefore, equal opportunities should exist in the process of visiting such spaces, starting with the full accessibility of the respective environment.

1.2. Inclusive and Accessible Museums

Working towards inclusivity is the only way to achieve sustainability in society and humanity. In this direction, museums should be renovated and provide accessibility [13] to meet the needs of all people in the present and future generations [33]. Some of the very good practices that could take place could involve exhibitions designed to include people with disabilities [33], as well as the exploitation of high-technology means to provide a multisensory experience [34].

In terms of physical accessibility, the most obvious aspect refers to the design and the infrastructure of a museum’s space and its facilities [9,35,36]. Physical accessibility enables people with mobility difficulties to navigate easily and safely in public spaces [6,18]. According to [37,38], in Thessaloniki, there had been lots of inaccessible Byzantine monuments located in the city that people with mobility disabilities could not visit. There was a project in Thessaloniki named “PROSPELASIS” that was aimed to enhance spatial accessibility at twenty archaeological sites for the smoother transition of visitors, including the implementation of signage to guide individuals in moving easily and independently from one exhibit to another [37]. A significant requirement for that project was that any interventions that would take place should not damage the inherent characteristics or cause any visual or structural harm [38]. That project succeeded in offering the opportunity to people with disabilities to visit historical monuments and to feel safe [38].

Accessibility in a museum entails more than just physical access; [39] equally vital is access to information, which aids in comprehending the exhibition space [40]. Cognitive and sensory access should also be addressed and, where possible, adjustments should be made to reduce or remove existing barriers [41].

Previous work has emphasized the huge impact that the sense of touch has on individuals with visual impairments, enabling them to develop the ability to receive information related to what they are touching [42]. Related to the above theory, the Prado Museum in Madrid had provided six different famous paintings in 3D replicas that people could explore by touching them. This practice left many of the museum visitors—both those with visual impairments and those without disabilities—very satisfied due to the access they had to information on the paintings [43]. Another remarkable example was a touchable gallery with ancient sculptures that was hosted in a museum in Athens. According to visually impaired people, that project made their experience unforgettable and also made them feel more included in society because they could comprehend the historical background of the sculptures as well as others could [44,45].

Another difficult task for people with disabilities is navigating in museums, as they mostly feel unsafe due to the lack of access to space signs [46]. According to [38], every public space should provide lots of tactile and audio facilities to enable that all individuals have access. On a relative case, the experts had designed a significant path at a historical site in Greece, which included big, colorful arrows on the pavements so that individuals with intellectual disabilities could navigate independently through the archaeological monuments [38]. Equally useful are the technological systems that support people with visual impairments in exploring and navigating unfamiliar environments fully independently [47]. For instance, an exhibition, opened at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (USA) in 2010, included mobile-phone-based electronic systems with installed guides for navigation and orientation within the space, as well as audio descriptions of exhibits and the option to use American Sign Language instead [48].

In addition, conforming to [49,50], the employees of a museum should also be aware and informed of the principles of accessibility because they have the main responsibility to preserve it in those environments. In the research conducted by the authors of [25], it was found that people who worked in museums had not received any training on accessibility facilities and policies. Some employees revealed that they personally felt an inconvenience when accommodating individuals at museums due to the lack of protocols [25].

Taking into consideration the necessity and the importance of providing people with disabilities full and independent access to museums [51,52,53], any kinds of barriers, such as physical, intellectual, geographical, psychological, or economic barriers, that prohibit the access of an individual to a museum must be removed [5,54,55]. However, questions that remain difficult to answer are: how many of those barriers have been removed? And, after all, how accessible are museums nowadays?

1.3. Study

The aim of the research was to examine both the spatial accessibility as well as the information accessibility in certain museums and places of historical interest (Table 1) in two culturally important European cities, London (the capital of Great Britain) and Thessaloniki (the second-largest city of Greece). In addition, the research targeted the comparison between the two cities. Fifteen museums/places of historical interest (hereinafter referred to as “museums”) in London and fifteen in Thessaloniki were visited and assessed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Thirty participants—one representative for each the thirty museums in London and Thessaloniki (Table 1)—participated in the present research. More specifically, the participants who took part in the interviews were individuals from the museums with knowledge on accessibility, such as service managers and museum operation personnel, museum curators, archaeologists, historians, and guides. In cases where such individuals were not available, responses were provided by the most qualified personnel.

The selection of the study museums was based on criteria such as (a) the diversity of their content and their different natures in both cities, such as their being associated with history, art, natural sciences, technology, and interactive exhibitions; (b) a high visitor attendance rate; (c) the cultural significance of the museums; and (d) the operation of the museums for at least five years.

Thus, the museums investigated in London and in Thessaloniki were the following:

Table 1.

The museums examined in the context of the present research.

Table 1.

The museums examined in the context of the present research.

| London (Great Britain) | Thessaloniki (Greece) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Air Forces Museum | Archaeological Museum |

| 2 | Bank of England Museum | Museum of Byzantine Culture |

| 3 | British Museum | Cinema Museum |

| 4 | Donatello Sculptures Exhibition | Church of Saint Demetrius |

| 5 | Egyptian Exhibition | Museum of Contemporary and Modern Art |

| 6 | National Army Museum | Museum of Experimental Art |

| 7 | National Gallery | Jewish Museum |

| 8 | Natural History Museum | Museum of the Macedonian Struggle |

| 9 | Royal Academy of Arts | National Art Gallery |

| 10 | Science Museum | Olympic Museum |

| 11 | Tate Britain | Museum of Photography |

| 12 | Titanic Exhibition | Roman Forum |

| 13 | Victoria and Albert Museum | Rotonda |

| 14 | Wallace Collection | Seven Towers Prison (Yedikule) |

| 15 | Welcome Collection | War Museum |

2.2. Instruments

The first tool used in the present research was an extended 3-point Likert checklist of accessibility criteria and standards referring to all individuals with physical and intellectual disabilities. In order to develop the checklist, a series of documents were studied including official guidelines and scientific papers in both English and Greek (Table 2). More specifically, the Greek-language sources 1 and 2 are official guidelines; 3, 4, and 6 are guidelines adopted by the national associations of individuals with impairments; and source 5 is a state regulation. Regarding the English-language sources, 8, 9, 11, 13, and 15 are official documents and guidelines; 10, 12, 14, 16, 17, and 18 are scientific papers; and sources 7 and 19 are special reports.

Table 2.

Greek- and English-language sources used to develop the accessibility checklist for museums.

Data collection involved rating on a scale from 1—referring to a nonexistent accessibility facility/service—to 3, referring to existent accessibility facility/service. The option “Non-Applicable (N/A)” was used in those cases where the accessibility feature described in the assessment list could not be applicable.

Twenty-two categories assessing the accessibility of the museums on two different levels—physical space and information—were created. The categories 1–11 measured spatial accessibility while the categories 12–22 evaluated information accessibility and relative services (Table 3).

Table 3.

The 22 accessibility categories and their components (accessibility criteria), given as a data sample.

The second research tool was a semi-structured interview that explored (a) whether the employees of these spaces had knowledge and had received the appropriate training on accessibility or not, (b) information about accessibility services and best practices available in their museums, and (c) any kind of feedback from individuals with disabilities regarding the sufficiency or the insufficiency of accessibility in the museums of the study’s interest.

The combination of these two tools was expected to result in a wealth of information concerning the accessibility levels of the museums. The aims were (a) to extract detailed and specific data concerning the accessibility features or inadequacies using the checklist and (b) to combine these data with information received by the museum representatives that could not have been anticipated, so as to include them both in the checklist.

2.3. Methodology

The examination of the accessibility facilities and services commenced with observations by the researcher when she visited the museums. During her visits, the researcher collected the data using the checklist, along with photographing exhibits for further study and re-evaluation by the second researcher. At the end of the process, 30 copies of the checklist were collected, each containing different data—one for each museum. The two researchers discussed any disputable points until they reached a point of convergence. In case of further debatable points, a third expert’s consultation was made.

The museums visits lasted approximately 1.5 to 2 h for larger exhibition spaces and 30–60 min for small exhibition spaces. In the second stage of the visit, the semi-structured interview took place with the participation of the employees of the museums. Consequently, the content was transcribed and analyzed by the two researchers separately. Any divergence in the content analysis was further discussed with the third expert.

3. Results

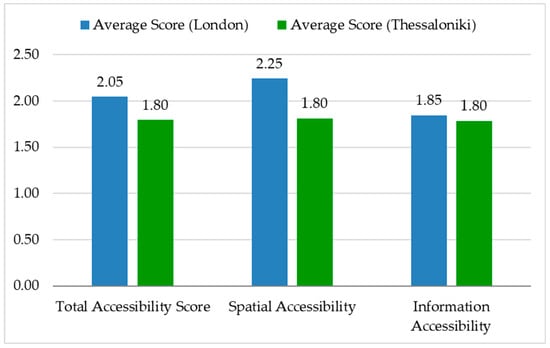

Descriptive statistics analysis and Independent Samples T-test analysis were performed. According to the mean scores of the two museums (a) in all the categories as a total, (b) in terms of spatial accessibility, and (c) in terms of information accessibility, the museums in London appear to be more accessible in all three cases (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Bar graph presenting the comparison of the museums in London and in Thessaloniki with reference to both their accessibility as a total as well as their spatial and information accessibility.

A more detailed study of the data in the 22 accessibility categories revealed that the main differences between the museums of the two cities existed in almost all categories (Table 4), with “Entrances and Doors” (t(28) = 4.09, p < 0.001), “Stairs” (t(27) = 3.08, p = 0.005), “Elevators” (t(25) = 2.49, p < 0.05), “Exhibition Space Location” (t(28) = 4.40, p < 0.001), “Seating Areas” (t(28) = 3.74, p < 0.001), “Information Access—Guided Tours” (t(28) = 2.05, p < 0.05), and “Access to Services” (t(28) = 5.50, p < 0.001) being the variables with statistically significant differences.

Table 4.

Means and standard deviations of the museums in London and Thessaloniki for the 22 accessibility categories.

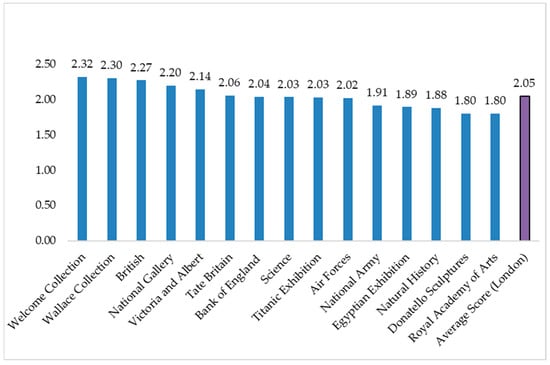

In addition, examining the museums of each city separately and making comparisons of the museums to each other, it was found that in London, the Welcome Collection (M = 2.32), Wallace Collection (M = 2.30), and British (M = 2.27) museums were the most accessible ones in terms of both spatial accessibility and information/services accessibility. The less accessible museums with regard to both spatial and information accessibility were the Royal Academy of Arts (M = 1.80), the Donatello Sculptures Exhibition (M = 1.80), and the Natural History Museum (M = 1.88) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Accessibility scores (means) for each museum in London and the average score.

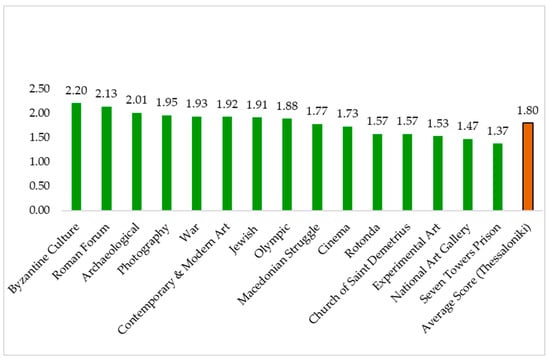

Concerning the museums in Thessaloniki, it was found that the Museum of Byzantine Culture (M = 2.20), Roman Forum (M = 2.13), and the Archaeological Museum (M = 2.01) were the most accessible ones in terms of both spatial accessibility and information/services accessibility, while the less accessible ones were the Seven Towers Prison (Yedikule) (M = 1.37), the National Art Gallery (M = 1.47), and the Museum of Experimental Art (M = 1.53) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Accessibility scores (means) for each museum in Thessaloniki.

Moreover, the data collected through semi-structured interviews were analyzed and coded to provide the items/codes and the frequency of their appearance. The processing of the data was conducted separately for the museums of London and Thessaloniki in order to compare the results concerning each city to each other.

Regarding the activities a museum organizes and offers to children and/or adults with impairments, the item with the highest frequency for both cities was that the museum the interviewees visit offers activities to children with disabilities while these activities need to be well organized and planned (Table 5).

Table 5.

Activities the museums organize and offer for children/adults with disabilities.

Concerning the feedback the staff receives from visitors with disabilities with reference to the accessibility of a museum and its settings, the codes with the highest frequency of appearance were “general satisfaction” for London and the concern about access to museums using public transportation for Thessaloniki (Table 6).

Table 6.

Visitors with disabilities’ feedback about the museums’ accessibility.

Regarding the training of the staff in order to support the visitors with disabilities, the majority of the respondents (from the museums in both London and Thessaloniki) declared that they were underqualified since they had not received any appropriate training (Table 7).

Table 7.

Staff’s training to support visitors with disabilities.

4. Discussion

The present research aimed at the accessibility assessment of the museums of two culturally significant European cities, London and Thessaloniki. Based on the comparison of the two cities, the museums of London appear to be more accessible than the museums of Thessaloniki. This divergence seems to be grounded more in spatial accessibility and less in information accessibility. Specifically, most London museums offer comprehensive access to all areas for wheelchair users through elevators, ramps, or other means. A notable example is that many of the museums in London provide free wheelchairs for visitors, which is a service that stands out. Indisputably, spatial accessibility is very important because it makes visitors feel safe [6]. That was the reason why the European funded project in Greece called “PROSPELASIS” prioritized making two archeological sites in Thessaloniki, Rotonda and the Church of Sent Sophia, spatially accessible to people with mobility disabilities [9].

Reality shows that many times, accessibility is intertwined with access for individuals with mobility impairments, especially when it is discussed in the context of tourism [5]. In the present study, in both cities, i.e., London and Thessaloniki, the level of accessibility to space in museums was higher than the level of accessibility to information. In many museums, the primary focus was on ensuring special accessibility, with access to information being a secondary consideration. The Natural Museum in London aligns with the above theory as—despite the great access to space—there were lots of issues with the access to information. A great example was the lack of subtitles in videos, which had a negative impact on those with hearing impairments. It is also very notable that most of the museums in London had ramps and lifts everywhere in their facilities and, on the other hand, at the same museums, there were only very few exhibits that were accessible to people with visual impairments. This issue highlights how many museums fail to cater to people with sensory impairments. It has been suggested that, though museums differ in accessibility providence from country to country, it seems that there is more attention to physical access than to sensory access [32]. Similarly, the presence of “Do not touch” signs and the lack of tactile exhibits in museums can make them less approachable for individuals with visual impairments [28]. Actually, the focus on individuals with mobility impairments and spatial accessibility does not cause any surprise. Having a retrospective look on accessibility’s evolution, one can easily detect that efforts towards accessibility had their roots in barrier-free buildings [61]. Even when the term Universal Design was introduced to refer to interventions that could lead to accessible environments for all people (disabled or not), this was propagated by Ronald L. Mace [46], an architect renowned for his work on disability.

However, access to information is a vital aspect for all individuals with disabilities. The museums examined in the frame of the present study appeared to be underequipped with the (technology) means that could promote access to information and inclusiveness. A notable example from the present study is that people with visual impairments could be supported by the tactile maps that exist in the Museum of Byzantine Culture for navigating independently. Indeed, tactile material and replicas are often suggested as solutions for access to exhibits and artifacts for individuals with visual impairments, with the original exhibits/artifacts being preserved and avoiding erosion [28]. It has been found that tactile material or replicas included in a museum can have a profound impact on visually impaired visitors, allowing them to acquire information about the objects they are touching [37]. For the same reason, museums may use multisensory approaches, including tactile collections and replicas, handling sessions, audio guides and verbal assistance [39], or means of high technology such as virtual, and mixed reality applications [33], to provide a more accessible experience to visitors with visual impairments.

Moreover, based on the feedback received from visitors with disabilities, the interviewees in London and Thessaloniki emphasized the formers’ need to have plenty of tactile and auditory information that provides a full experience of the museums’ exhibits. This finding is in line with previous studies that suggested that although tactile material, replicas, and audio descriptions constitute a significant step towards accessibility, they usually entail strenuous preparation, which make them restricted to being just a part of all the museum exhibits and information [61], while their effectiveness in conveying the necessary information and enabling a positive experience for visitors with visual impairments is questionable [44].

However, apart from individuals with mobility or visual impairments, visitors with other kind of disabilities or impairments appear to be underserved. Regarding the present study, the National Army Museum in Thessaloniki provided big, colorful arrows as signs for helping individuals with intellectual disabilities to find their orientation at all times without support. Indeed, that kind of assistive equipment aims to encourage people with disabilities to have access to information in a museum. However, measures to improve accessibility for individuals with intellectual disabilities—such as the use of more simple language for information on exhibits, or the use of graphics for guidance—proved to be scarce. A similar study on the accessibility of the museums in Seville also found while the needs of people with mobility impairments received the most attention, the needs coverage for individuals with mental disabilities appeared to be marginal [7].

Moreover, a closer look at the differences between the museums of the same city revealed that much of their accessibility levels depended on the chronological ages of the buildings in which the museums were hosted. It is worth mentioning that some representatives of the museums (especially in Thessaloniki) expressed their concerns about the chronological ages of the buildings. According to them, a building’s oldness could be a huge obstacle as it would not allow the provision of a lift, elevator, etc. Moreover, national or international law and regulations regarding the protection of preservable buildings may pose additional obstacles in accessibility intervention procedures. This was why the Seven Towers Prison of Yedikule, the Church of Saint Demetrius, and the Rotonda in Thessaloniki were mostly inaccessible to individuals with mobility disabilities. Indeed, in London, modern museum structures were constructed with accessibility standards in mind, whereas many historical museums and sites in Thessaloniki lacked such considerations. Thessaloniki boasts numerous historical sites dating back to the Byzantine era, a time when there were no regulations for accommodating individuals with disabilities. Consequently, Thessaloniki faces greater difficulty in adapting its spaces to meet contemporary accessibility requirements, and the financial burden of implementing necessary reforms presents a significant challenge. The conflict between a building’s age and accessibility is not the first time this challenge resurfaces. Other researchers have previously highlighted the difficulty in, or even the impossibility of, making adjustments towards accessibility because of a building’s structural specificities [49]. Newer buildings seem to be more compliant with national regulations or international guidelines [44] while older ones present a more gradual conformity [18].

In such cases where it is difficult to solve accessibility issues, probably, they could be compensated for with the support of qualified staff that serve visitors with disabilities. However, the majority of employees reported that they had not received any additional training on how to support people with disabilities and how to provide accessibility in their environment. According to the staff of some museums, everything they learned came from their own experience, without taking any guidance or instructions. It appears that there is willingness among exhibition-space personnel to learn and be trained to better assist individuals with disabilities, particularly to make them feel more comfortable during their visits. Museum staff’s training has previously suggested as a way to deliver multisensory services to individuals with disabilities [50].

The most robust feature of the present research is that for the first time, museums of culturally important cities were evaluated for their accessibility with such an extended, in-depth, and scientifically well-grounded accessibility checklist. However, the findings of the present study provide not only a detailed examination of the museums’ accessibility in London and Thessaloniki but also a general picture of the museums’ accessibility levels that someone could anticipate. Thus, the results of the study are of great significance not only for those who would like to be informed on the museums’ accessibility—in terms of both spatial and information—in the two cities but also for those who would like to work towards accessibility improvement in museums, places of historical interest, and other locations belonging to cultural heritage. The study’s innovation lies in the detailed and holistic assessment of the museums’ accessibility—not only for individuals with sensory impairments but also for individuals with intellectual disabilities. As such, the results could be very useful to those who wish to provide a more inclusive opportunity for access to history and culture.

5. Conclusions

In the context of the present study, the 30 museums—15 in London and 15 in Thessaloniki—were examined with reference to their accessibility levels (i.e., spatial and information/services). It was proven that the vast majority of the museums in both cities presented opportunities for development in order to include all kinds of visitors in the experiences they offered. Specific categories that need intervention towards accessibility are mainly the following: A) “Entrances and Doors”, “Exhibition Space Location”, “Emergency Exits and Evacuation Routes”, and “Access to Services” for the museums in Thessaloniki and B) “Ramps”, “Protection and Safety Features“, “Orientation”, “Seating Areas”, “Signage”, Exhibition Design”, “Exhibits”, “Text Format”, “Imagery”, “Information Access—Guided Tours”, and “Best Practices” for the museums in both cities. Achieving spatial and information/services accessibility is not always very easy since formal restrictions (e.g., a national law for the protection of preservable buildings) or objective difficulties (e.g., a building’s oldness) may contradict many kinds of structural interventions. However, when someone has the tools to study a problem in detail, and holistically, they can definitely step into corrective actions towards accessibility.

6. Future Directions

The present research focused on (a) the development of a holistic accessibility tool to examine spatial and information/services accessibility and (b) on the examination of museums in two culturally significant cities—London and Thessaloniki. Future research should examine more variables that intervene in accessibility interception, such as national and international law/regulations for the protection of preservable buildings or the financial prerequisites. A more specific investigation of the reasons behind accessibility absence could shed more light on the problem under discussion.

7. Limitations

The examination of the 30 museums was conducted in situ by the one of the researchers and the data collected were discussed by both researchers. However, an initial in situ examination by both the researchers could probably have led to a more objective evaluation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.K.; formal analysis, E.K.; investigation, M.K.; methodology, E.K.; supervision, E.K.; writing—original draft, E.K. and M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethics restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- UN. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), UN. 2007, pp. 1–31. Available online: https://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- Jones, M. Inclusion, social inclusion and participation. In Critical Perspectives on Human Rights and Disability Law, 1st ed.; Rioux, M.H., Basser, L.A., Jones, M., Eds.; Brill-Nijhoff: Leiden, The Netherlands; pp. 57–82. [CrossRef]

- Allday, K. From changeling to citizen: Learning disability and its representation in museums. Mus. Soc. 2009, 7, 32–49. [Google Scholar]

- Sandell, R. Museums as agents of social inclusion. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 1998, 17, 401–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israeli, A. A preliminary investigation of the importance of site accessibility factors for disabled tourists. J. Travel Res. 2002, 41, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, S.; Carneiro, M.J. Accessibility of European museums to visitors with visual impairments. Disabil. Soc. 2016, 31, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-García, M.E.; Criado-García, F.; Camúñez-Ruíz, J.A.; Casado-Pérez, M. Accessibility to Cultural Tourism: The Case of the Major Museums in the City of Seville. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepple, B. The new single equality act in Britain. Equal Rights Rev. 2010, 5, 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sandell, R.; Dodd, J.; Garland-Thomson, R. Re-Presenting Disability: Activism and Agency in the Museum; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Persson, H.; Åhman, H.; Yngling, A.A.; Gulliksen, J. Universal design, inclusive design, accessible design, design for all: Different concepts—One goal? On the concept of accessibility—Historical, methodological and philosophical aspects. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2015, 14, 505–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gábos, A.; Kopasz, M. Concept Paper on the Extension and Further Development of IPOLIS; Leuven, H2020 InGRID-2 Project; Research Institute for Work and Society: Leuven, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, J.; Vegelin, C. Sustainable development goals and inclusive development. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2016, 16, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, H. The Contexts of Social Inclusion. 2015. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2641272 (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Rieger, J. Moving beyond visitor and usability studies: Co-designing inclusion in museums and galleries. In Proceedings of the Advances in Industrial Design: Proceedings of the AHFE 2020 Virtual Conferences on Design for Inclusion, Affective and Pleasurable Design, Interdisciplinary Practice in Industrial Design, Kansei Engineering, and Human Factors for Apparel and Textile Engineering, San Diego, CA, USA, 16–20 July 2020; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 167–172. [Google Scholar]

- Ander, E.; Thomson, L.; Noble, G.; Lanceley, A.; Menon, U.; Chatterjee, H. Generic well-being outcomes: Towards a conceptual framework for well-being outcomes in museums. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2011, 26, 237–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, J.; Jones, C. Mind, Body, Spirit: How Museums Impact Health and Wellbeing; University of Leicester: Leicester, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Goodnow, K.J.; Akman, H. Scandinavian Museums and Cultural Diversity; Berghahn Books: Oxford, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 23–89. [Google Scholar]

- Welage, N.; Liu, K. Wheelchair accessibility of public buildings: A review of the literature, Disability and Rehabilitation. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2011, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, G.E. Progressive museum education: Examples from the 1960s 1. Int. J. Progress. Res. Educ. 2013, 9, 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Woolf, A.B.; Armstrong, J.; Jamieson, L.; Golding, J.B. Recent trends in Australasian and world horticultural market access research and development. In International Symposium Postharvest Pacifica 2009—Pathways to Quality: V International Symposium on Managing Quality in 880; International Society for Horticultural Science: Leuven, Belgium, 2009; pp. 463–470. [Google Scholar]

- Zakaria, N.N. Assessing the working practices and the inclusive programs to students with disabilities in the Egyptian museums: Challenges and possibilities for facilitating learning and promoting inclusion. Front. Educ. 2023, 8, 1111695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J.H.; Dierking, L.D.; Adams, M. Living in a Learning Society: Museums and free-choice Learning. In A Companion to Museum Studies; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 323–339. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, I.F. Assessment method of accessibility conditions: How to make public buildings accessible? Work 2012, 41 (Suppl. 1), 3774–3780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argyropoulos, V.; Nikolaraizi, M.; Kanari, C.; Chamonikolaou, S. Current and future trends in museums regarding visitors with disabilities: The case of visitors with visual impairments. In Proceedings of the 9th ICEVI European Conference, Dialogue, Bruges, Belgium, 2–7 July 2017; pp. 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Sandahl, J. The museum definition as the backbone of ICOM. Mus. Int. 2019, 71, vi–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanari, H.; Argyropoulos, V. Museum educational programmes for children with visual disabilities. Int. J. Incl. Mus. 2014, 6, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynard, E.; Pica, A.; Coratza, P. Urban geomorphological heritage. An overview. Quaest. Geogr. 2017, 36, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillen, R. Museum disability access: Social inclusion opportunities through innovative new media practices. Pac. J. 2015, 10, 95–107. [Google Scholar]

- Argyropoulos, V.; Nikolaraizi, M.; Chamonikolaou, S.; Kanari, C. Museums and people with visual disability: An exploration and implementation through an ERASMUS+ Project. In Proceedings of the EDULEARN16 Proceedings IATED, Barcelona, Spain, 4–6 July 2016; pp. 4509–4516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candlin, F. Don’t touch! Hands off! Art, blindness and the conservation of expertise. Body Soc. 2004, 10, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandell, R. Social inclusion, the museum and the dynamics of sectoral change. Mus. Soc. 2003, 1, 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, J. The long-term impact of interactive exhibits. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 1991, 13, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kates, R.W. What kind of a science is sustainability science? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 19449–19450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietroni, E.; Pagano, A.; Biocca, L.; Frassineti, G. Accessibility, natural user interfaces and interactions in museums: The IntARSI project. Heritage 2021, 4, 567–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, N. Audience development and social inclusion in Britain: Tensions, contradictions and paradoxes in policy and their implications for cultural management. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2006, 12, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, R.L.; Marston, J.R. Measuring accessibility for people with a disability. Geogr. Anal. 2003, 35, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vozikis, K.T. Are there accessible environments in Athens, Greece today. WSEAS Trans. Environ. Dev. 2009, 7, 488–497. [Google Scholar]

- Naniopoulos, A.; Tsalis, P. A methodology for facing the accessibility of monuments developed and realised in Thessaloniki, Greece. J. Tour. 2015, 1, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naniopoulos, A.; Tsalis, P.; Papanikolaou, E.; Kalliagra, A.; Kourmpeti, C. Accessibility improvement interventions realised in Byzantine monuments of Thessaloniki, Greece. J. Tour. 2015, 1, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alisha, M.Y.; Kusuma, N.R. Wayfinding system for the blinds in the museum. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 673, 012047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, D. Approaches in museums towards disability in the United Kingdom and the United States. Mus. Manag. Curatorsh 2009, 24, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, E.; van der Linden, J. Using eTextile objects for touch based interaction for visual impairment. In Proceedings of the 2014 ACM International Symposium on Wearable Computers: Adjunct Program, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–17 September 2014; pp. 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostakis, G.; Antoniou, M.; Kardamitsi, E.; Sachinidis, T.; Koutsabasis, P.; Stavrakis, M.; Zissis, D. Accessible museum collections for the visually impaired: Combining tactile exploration, audio descriptions and mobile gestures. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services Adjunct, Florence, Italy, 6–9 September 2016; pp. 1021–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyropoulos, V.S.; Kanari, C. Re-imagining the museum through “touch”: Reflections of individuals with visual disability on their experience of museum-visiting in Greece. Alter 2015, 9, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, L.; Mayfield, S. Accessible Tourism: Transportation to and Accessibility of Historic Buildings and Other Recreational Areas in the City of Galveston, Texas. Public Works Manag. Policy 2004, 8, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danso, A.K.; Ayarkwa, J.; Dansoh, A. State of Accessibility for the Disabled in Selected Monumental Public Buildings in Accra, Ghana. Ghana Surveyor 2011, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wegscheider, A.; Guével, M.R. Emploi et handicap: Politiques publiques et perspectives des employeurs en Europe. Alter Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2021, 15, 2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Loomis, J.M.; Klatzky, R.L.; Golledge, R.G. Navigating without vision: Basic and applied research. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2001, 78, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, H. American sign language and audio description on the mobile guide at the museum of fine arts, Boston. Curator Mus. J. 2013, 3, 369–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayhoe, S. A practice report of students from a school for the blind leading groups of younger mainstream students in visiting a museum and making multi-modal artworks. J. Blind. Innov. Res. 2013, 3, 1–11. Available online: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/id/eprint/50351 (accessed on 20 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Darcy, S.; McKercher, B.; Schweinsberg, S. From tourism and disability to accessible tourism: A perspective article. Tour. Rev. 2020, 75, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollins, H. Reciprocity, accountability, empowerment: Emancipatory principles and practices in the museum. In Re-Presenting Disability, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2013; pp. 228–243. [Google Scholar]

- Mace, R.L.; Hardie, G.J.; Place, J.P. Accessible environments: Toward universal design. In Design Interventions: Toward a More Humane Architecture; North Carolina State University: Raleigh, NC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Miesenberger, K.; Kouroupetroglou, G.; Mavrou, K.; Manduchi, R.; Rodriguez, M.C.; Penáz, P. Computers Helping People with Special Needs. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference, ICCHP-AAATE 2022, Proceedings, Part I, Lecco, Italy, 11–15 July 2022; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Environment, Physical Planning, and Public Works, Office of Studies for Persons with Disabilities. Designing for All, Specifications Document; Ministry of Environment, Physical Planning, and Public Works, Office of Studies for Persons with Disabilities: Athens, Greece, 1996.

- International Council of Museums. Greek Section ICOM Code of Ethics Museums; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2009; pp. 13–42. Available online: https://icom-greece.mini.icom.museum/wp-content/uploads/sites/38/2018/12/code-of-ethics_GR_01.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- ESAmeA. Culture for All. Ensuring Equal Participation of People with Disabilities in Cultural Life. 2019, pp. 10–41. Available online: https://paratiritirioanapirias.gr/storage/app/uploads/public/5f8/6cf/3de/5f86cf3deca24869042506.doc (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- National Confederation of Disabled People. Culture for All; National Confederation of Disabled People: Athens, Greece, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Government Gazette of the Hellenic Republic. Persons with Disabilities and Persons with Reduced Mobility According to Current Legislation; Government Gazette of the Hellenic Republic: Athens, Greece, 2020.

- Weisen, M. How accessible are museums today? In Touch in Museums; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2020; pp. 243–252. [Google Scholar]

- Isikoren, S.H.; Aygenc, E. Sustainability of Exhibition Halls while adapting to Design Concept and Technology in Museums. St. Barnabas Icon and Archaeological Museum Examples. Rev. Cercet. Interv. Soc. 2018, 62, 331–351. [Google Scholar]

- Hirzy, E.C. Excellence and Equity: Education and the Public Dimension of Museums: A Report from the American Association of Museums; American Association of Museums: Washington, DC, USA, 1998.

- Salmen, J. Everyone’s Welcome: The Americans with Disabilities Act and Museums; 1575 Eye St., NW., Suite 400; American Association of Museums: Washington, DC, USA, 1998.

- Hall, P.; Imrie, R. Architectural practices and disabling design in the built environment. Environ. Plan. B 1999, 26, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, A. A Story of Engagement: The British Council; British Council: London, UK, 2009; pp. 1934–2009. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Human-Centered Design. ADA Checklists for Existing Facilities; Institute for Human-Centered Design: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wapner, J. Mission and Low Vision: A Visually Impaired Museologist’s Perspective on Inclusivity. J. Disabil. Policy Stud. 2013, 33, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, M. Second Legislative Review of the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act, 2005. Retrieved from the Government of Ontario Website. 2014. Available online: https://docs.ontario.ca/documents/4019/final-report-second-legislative-review-of-aoda.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Brittin, J.; Sorensen, D.; Trowbridge, M.; Lee, K.K.; Breithecker, D.; Frerichs, L.; Huang, T. Physical activity design guidelines for school architecture. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, P.; Thomas, B. The economics of museums: A research perspective. J. Cult. Econ. 1998, 22, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffinbargar, M.S. An Assessment of Disability Access at the University of Kentucky; University of Kentucky: Lexington, KY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).