Abstract

This study examines the knowledge and involvement of consumers in sustainability goals, aiming to provide valuable insights to the textiles and clothing industry to foster their social responsibility efforts and enhance consumer interaction. By comprehending and monitoring consumer behavior, organizations can effectively implement sustainable practices and work towards achieving sustainable development goals. For this study, a questionnaire was designed to evaluate consumer concerns, behavior, self-reliance, and perspectives across four key phases of interest in sustainable consumer behavior regarding textiles—acquisition, use, maintenance, and disposal. The results show a compelling insight into the mindset of participants who prioritize budget, quality, comfort, and functionality over sustainability when acquiring new textile items. Most respondents do not participate in clothing rental or sharing and predominantly refrain from purchasing second-hand products, but they expressed a readiness to extend the lifespan of their products and displayed concern about ensuring a responsible end-of-life for their belongings. Moreover, they attach importance to textile products’ social and informational attributes and demand transparency from brands. These valuable data can guide the industry in its interactions with consumers. Scholars are increasingly committed to sustainability and its implications for practical application and policy development.

1. Introduction

The sustainability topic presents several implications for social, environmental, economic, and health responsibilities. The United Nations’ sustainable development goals (SDGs) [] target beneficial societal changes. Toward that aim, there is a need for action between several entities: governmental and educational institutions, organizations, associations, companies, and the community.

In this study, we focus, especially on SDG 12, which regards sustainable consumption and production patterns, in order to provide suitable guidance for corporate social responsibility action and social marketing campaigns on the back of a theory-based analysis of consumer engagement with sustainability.

The role of consumers in sustainable development is often based on the promotion of circularity, as they are the ones who can ensure the extension of product lifecycles, the suitable disposal of products at the end of the lifecycle, and the reuse of products. This role involves the adoption of behaviors that are not always aligned with the attitudes and values of consumers, and so the study of values and beliefs that are not aligned with sustainable behavior, as well as the determination of consumer perception of self-efficacy, is paramount.

Industry can play a role in changing consumers’ commitment to sustainable behavior, precisely by acting over beliefs that do not represent reality or by influencing social in-groups to promote values that align with sustainable developments, as well as by galvanizing positive attitudes via reward.

In order to be able to improve knowledge and devise strategies, we developed a survey aimed at collecting the values, beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors of Portuguese consumers of fashion and textile industry products. This survey was divided into four sections pertaining to the four phases of consumption, acquisition, use, maintenance, and discarding, all of which have an emphasis on consumer involvement. The survey contained multiple choice, dichotomous choice, and Likert scale-based questions probing consumer values affecting product acquisition, engagement with sustainability information, fast-fashion alternatives, sustainable use, willingness of product maintenance, and mindful product discard habits.

This study looked to answer whether consumers value their consumption habits, their perception of control in sustainable action, their attitude toward sustainable action and fast fashion alternatives, and the sustainable behaviors they already engage in. Answering these questions will allow for a look into consumer psychology and provide guidance regarding what aspect social marketing campaigns should target to increase the adoption of sustainable behavior.

This study is structured as follows: we first present a literature review about this topic, followed by the methodology used, a descriptive analysis of these data, and related findings. We next discuss our results structured around the four phases of consumer action toward product lifecycle: acquisition, use, maintenance, and discarding. This allows us to synthesize the lack of consumer knowledge and awareness of sustainable practices. We conclude by discussing the social psychology implications. These are hugely beneficial and can be made to inform future inquests of social marketing to encourage the adoption of sustainable consumer behavior more effectively in the clothing and textiles industry.

2. Literature Review

The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs [] has outlined the sustainable development goals (SDGs), which delineate the direction for sustainable development in several areas []. These goals encompass social, environmental, and economic aspects, providing a comprehensive framework for fostering sustainability [,,,,]. The SDGs consist of 17 goals that encapsulate various dimensions of sustainability, as referenced by multiple authors, indicating their significance and widespread recognition [,,]. Figure 1 illustrates these 17 SDGs.

Figure 1.

The 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—A Framework for fostering Sustainability.

The SDGs offer a structured approach to address environmental concerns and frame our potential sustainability responses. Furthermore, these goals can serve as a supporting framework for designing measures and influencing consumers’ views, choices, and actions toward responsible consumerism and sustainability, fostering awareness and shaping their perspectives.

The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 12 is to ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns, and nowhere is the impact of this goal more important than in fashion consumption. The environmental impact of the fashion industry can be noticed in the many steps of its supply chains, from the environmental impacts seen in the agricultural and petrochemical production steps to the manufacturing, logistics, and retail []. This impact is especially visible in fast fashion, as it tends to have social and environmental impacts to support the rapid increase in material throughput, having grown to twice the amount of clothing produced than in the year 2000 []. The sheer amount of textile waste produced by fast fashion warrants a fast change in consumption patterns [] and a move towards circularity, for example, with the adoption of second-hand purchase practices, which enable the extension of clothing life cycles and decrease the need for new prime matter []. Regardless of the impact of fast fashion within the industry, previous incurrences in the literature have shown an imbalance in social, economic, and environmental aspects of sustainable development [].

When considering the implementation of these goals, understanding consumer behavior becomes paramount []. Consumers hold significant control over the specific unsustainable consumption patterns in the fashion industry. As end-consumers, their choices and behaviors directly influence the demand for fast fashion and drive textile products’ high consumption and disposal rates []. In recent times, there has been a notable trend among consumers to prioritize cheap and trendy clothing, leading to frequent purchases and swift disposal of items []. This behavior consumption pattern has significantly contributed to generating post-consumer textile waste []. Moreover, it is essential to empower consumers with the knowledge that their choices hold the potential to shape the industry. Consumers can significantly influence the fashion and textile sectors through their purchasing decisions. By consciously selecting sustainable and eco-friendly products, advocating for transparency in supply chains, and patronizing brands that prioritize environmental responsibility, consumers can send a resounding message to the industry. As the demand for sustainable products continues to surge, companies must embrace more sustainable practices and actively work towards reducing their environmental impact.

The concept of a circular economy (CE) may offer an elegant solution that seamlessly connects the dots between sustainable practices, the SDGs, and responsible consumer behavior. This system is understood as sustainable due to its focus on reusing materials and reducing the use of new prime matter [], turning products at the end of their lifecycle into resources to make new products, essentially closing the loop of product lifecycles [,]. Ultimately, this model aims to move away from the traditional linear model of “take, make, dispose” and has been applied around the world as developed and developing economies are working towards a sustainable economy and society [,,]. In order to embrace the circular system, both consumers and industry are essential players, as consumers within a circular system must be open to adopting habits of reusing products, be that as remanufactured products or repaired products, and the industry is forced into an extra effort of marketing this type of products and providing consumer education, for example, via social marketing [].

Several theories can explain consumer engagement with sustainability in the fashion industry and the adoption of sustainable practices. Through the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) [], it is possible to understand that aspects such as consumer attitude, informed by a set of beliefs [] towards a specific behavior, deeply affect their chances of behavioral modification, which, along with their perception of control are two of the most essential factors in the adoption of green consumer behavior [,].

It is through the value-belief-norm (VBN) [] theory that the connection between an individual’s core egoistic and altruistic values and beliefs, prescriptive and descriptive, on environmental issues can be explored, as involvement can often depend on whether the individual consumer holds the prescriptive belief that what is being performed to address sustainable development is not enough, or that it could benefit from their involvement, along with the descriptive belief that their own involvement is a causal effect to the problem. VBN has often been applied in conjunction with TPB due to their individual strengths. While TPB is strong in explaining self-interest, VBN is stronger in altruistic behaviors, providing a complete picture of consumer motivation []. VBN also explains and exposes the importance of informing consumers, with education having a very strong impact on their beliefs [].

Often, the consumer’s personal values or norms—internalized moral standards and principles—require the presence of antecedent conditions to be activated, such as the awareness of their own impact and the consequences of their actions, as well as an emotional bond to the issues at hand, as explained by the norm activation model (NAM) []. This explanation of norm activation is useful to predict intention and is often used in conjunction with TPB in this effect [].

Along with personal values, attitudes, beliefs, and activation factors, sustainable consumer behavior can be foretold by consumer’s social situations, such as their in-groups, or the groups they belong to, and out-groups, the groups they do not perceive themselves to be a part of. The social identity theory (SIT) [,] explains how individual social identity and self-esteem are intricately linked to social dynamics. This social dynamic often leads to the rejection of out-groups and intensifies bias while promoting in-group values, such as action on social causes. SIT can often act as a mediator between TPB, NAM, and VBN through its focus on self-identity [].

If we consider the significance of empowered consumers in promoting sustainable practices, it becomes evident that education alone may not address all the challenges they encounter. Despite possessing the necessary tools and access to information to engage in the market actively, the affordability of sustainable products remains a concern for many budget-conscious individuals []. However, despite education being a potential means of empowerment, it does not solely address the challenges consumers face. In many cases, consumers seeking greener products often find themselves priced out of the market. Budget-conscious individuals may perceive higher risks associated with sustainable purchases, limiting their participation in the sustainable market. To encourage the adoption of greener products, researchers have explored consumer willingness to pay for them, providing insights that can help the industry avoid pricing consumers out of the market []. Studies reveal that consumers already consider a company’s engagement with economic and environmental sustainability, along with price, when assessing the value of a product []. Another struggle consumers face is a lack of readily available information, despite industry and government collaboration to improve accessibility to sustainable-related product information. The Digital Product Passport initiative aims to address this issue by providing comprehensive information for product purchases [,]. However, even with increased information, consumers often find it challenging to comprehend, leading to feelings of distrust [].

This interaction between industry and consumers, along with political deciders and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), forms the necessary multi-stakeholder collaboration (MSC) [,,] necessary to tackle the problem of sustainable development. MSC is capable and integral to informing interactions between a plurality of stakeholders driven to intervene in a particular social ill, requiring that trust between parties is built upon a common purpose, open communication, shared decision-making, and the search for mutually beneficial outcomes [].

Drawing from the preceding discussion, it is imperative to consistently observe consumers’ perceptions, attitudes, values, and beliefs to refine policies and initiatives, such as those pertaining to social marketing, aligning them with their ever-changing preferences. For instance, keeping track of consumer behavior is instrumental in tackling the problem of excessive textile waste. By comprehending disposal patterns and the underlying reasons for item disposal, it becomes possible to develop creative approaches that effectively curtail waste generation. Remaining vigilant to the fluidity of consumer behavior empowers organizations to adjust their strategies effectively, meeting the evolving demands and expectations regarding sustainability and responsible consumption. Thus, the central research problem of this study revolves around effectively aligning consumer behavior and beliefs within the textiles sector with regard to the needed efforts to communicate clear messages about sustainability and engage in other modalities of corporate social responsibility (e.g., campaigns to increase recycling).

With this in mind, this study holds the singular purpose of empirically investigating how consumers, informed by their values, beliefs, and social dynamics, perceive their own actions, along with that of industry, within the fashion space, with regard to sustainability. It is the intention of the authors for this investigation to be performed through the lens of the theoretical framework presented herein and, through discussion, contribute to the application of each of the theories presented in the space of sustainable consumer behavior. This study aims to answer several research questions, among them “Do consumers value their consumption habits?”, “Do consumers perceive themselves to be in control of their engagement with sustainability?” “Do consumers hold a positive attitude towards sustainable actions and the alternatives the market presents to fast fashion?” and “What sustainable behaviors does the consumer population already engage in?” although no less important than “What aspects of consumer psychology should social marketing actions target to increase the adoption of sustainable behavior?”.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample

This study involved a sample of 1056 Portuguese participants, recruited through convenient sampling via social media and e-mail promotions, from March to May 2023. After removing respondents who failed to complete any questions after indicating their consent to ensure sample integrity, the final sample size was reduced to 1026. All participants filled out a consent form to participate in this survey. Data collection was anonymous and performed in conformity with the Declaration of Helsinki []. Among valid samples, further demographic information is discussed below.

Regarding age distribution, a large part of participants (29.1%) fell within the age bracket of 26 to 35 years of age at the time of data collection, while 28% were in the range of 46 to 60 years, 12.67% were in the range of 36 to 45 years, 13.4% were in the age range of 18 to 25 years, and the smallest subgroup was represented by participants above the age of 60 (3.5%). Finally, two participants (0.2%) opted not to disclose their age range.

In terms of gender, the sample generally comprises more women than men. Most respondents (68.5%) identified as female, while 31.1% identified as male. Only one respondent (0.1%) preferred not to reveal that information. No participants identified with other genders, and two individuals (0.2%) chose not to indicate their gender.

For academic qualifications, the majority of participants (81.3%) reported having a higher education degree (47.3% had a postgraduate degree and 33.7% had an undergraduate degree), 16.4% had a high school level education, while 2% of participants had an education level lower than that.

Most respondents (60.1%) identified their geographical area as urban, while 23.8% identified it as a “big city,” and 15.8% identified it as “rural.” One participant chose not to answer this question.

They also reported the number of dependents. Most respondents (54.2%) reported having no dependents, 21.8% of respondents reported having only one dependent, 19.4% of respondents reported having two dependents, 2.7% of respondents reported having three dependents, and 1.6% of respondents reported having more than three dependents. Finally, when reporting about income comfort, most participants (48.2%) stated their income allowed them to pay expenses, 36.6% of participants stated their income allowed them to live comfortably, 9.8% stated their income was difficult to live with, 3.8% stated that they were not able to gauge their income comfort, and 2% stated they find it very difficult to live with their current income. Additionally, 3.4% stated being unable to judge their comfort level with current household income.

3.2. Questionnaire

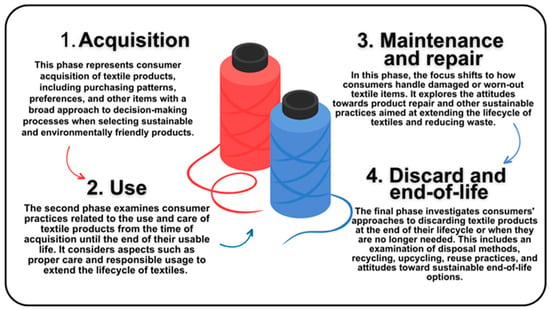

The research team, in collaboration with experts in the field and partners from the project be@t, designed the questionnaire under the same name. The Questionnaire be@t was thoughtfully structured into four sections, aligning with the four key phases of interest in sustainable consumer behavior regarding textiles, as identified by the research team in consultation with experts from the field. This questionnaire is depicted in the supplementary file (Supplement S1). Figure 2 below depicts the representation of the four identified phases, capturing the essence of the questionnaire.

Figure 2.

Phases of Sustainable Consumer Behaviour in the Textile Industry.

In addition to the items for those four phases, demographic characteristics were also collected. The questionnaire had dichotomous (Yes/No, DC), multiple choice (MC), and 5-point Likert scale (LS) response options. The questionnaire inquiries assess the interest of Portuguese consumers in sustainable consumption. It aimed to evaluate their consumption patterns, factors influencing their choices, interest in sustainable products, awareness of ecological characteristics that influence their carbon footprint during product acquisition, as well as their ability and willingness to prolong product usage and provide proper end-of-life treatment for circularity and waste reduction. The questionnaire was considered appropriate to identify and characterize the profiles of such consumers, as it was validated by three experts in the field to evaluate its length, content, and clarity questions, ensuring content validity. Furthermore, during the pilot test, the initial thirty questionnaires were administered without any issues of comprehension reported. Figure 3 showcases all four phases of the questionnaire, including their respective titles.

The questionnaire was distributed using the online survey platform Qualtrics© (2022) through LinkedIn, Instagram and Facebook.

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of the phases of the questionnaire and topics evaluated in each of them.

3.3. Data Analysis

This empirical study is characterized as quantitative using descriptive techniques. The results section below showcases raw frequencies, which signify the count of the responses for each item. This choice aimed to capture unmodified data points and provide a specific level of granularity in the characterization of this consumer behavior domain. These results are inherently objective and do not undergo interpretation or transformation. Due to their inherent characteristics, these raw frequencies are regarded as discrete numerical values, and their measurement entails a straightforward counting procedure [].

These collected data were subjected to frequency analysis using IBM® Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, version 29.0.0.0 (241)) (Windows, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) [] to examine the distribution of responses across various categories. Only participants who finished the questionnaire were considered, which led to the exclusion of 30 participants. Those participants were eliminated before the frequency analysis process. The result was as follows.

4. Results

For a better understanding of the results obtained in this study, this section has been organized into four sections, mirroring the phases of the questionnaire discussed above.

4.1. Acquisition Phase

Participants were asked for the most common reason for acquiring new textile items (MC). A total of 65.5% of participants indicated replacing old or worn-out items as one of the most common reasons. The second most frequently cited reason (37.2% of participants) is the need for size or fit changes, while the third most reported reason was to avail of promotions and discounts (31.9%). Less common reasons expressed by participants included having items for special occasions and updating their wardrobe with the latest fashion trends, at 20.6% and 17.3%, respectively. Additionally, 1.2% of individuals declared additional reasons, which were not as frequently mentioned. Figure 4 further depicts participants’ reasons for acquiring new textiles.

Figure 4.

Factors influencing the purchasing decisions of new textile items, expressed in frequency of choice.

Participants were then asked for the range of the number of clothing items bought per month (MC). Most participants (81.5%) declared buying 0 to 2 textile items per month. Around 14.5% of participants stated they buy 2 to 5 items per month, and a smaller number of participants stated buying 5 to 8 or even more than 10 items per month. Yet, 2.5% of participants did not provide an answer to this question.

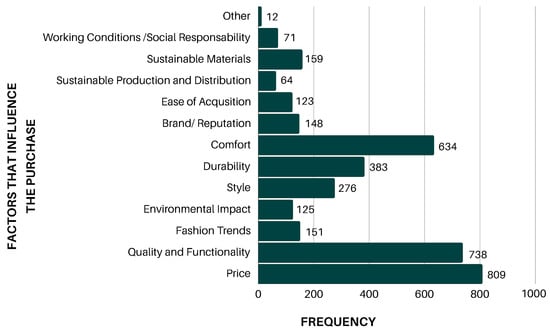

When asked for the most influential factors in product acquisition, price was identified as the most prominent factor affecting decision (this fact was selected by 54.9% of participants), while quality and functionality were a close second, with 50.3% of participants stating their importance. The third most cited factor impacting decision-making was comfort, selected by 43.2% of participants. It is important to note that participants could choose more than one option.

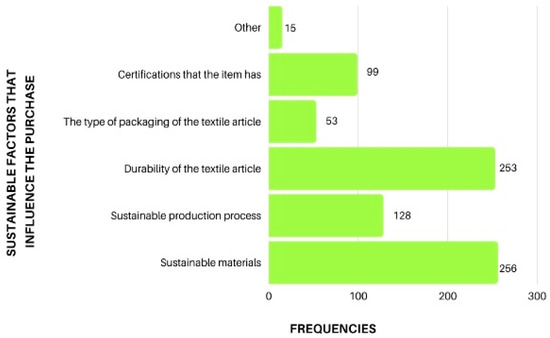

Upon being asked if they take the sustainability of an item into account (MC), most participants (61.1%) reported that they consider an item’s sustainability when buying a textile product. A total of 36.2% stated that they value item sustainability. Additionally, 2.5% of participants expressed that they have some consideration for an item’s sustainability when making a textile product purchase, while 0.2% reported not considering it at all. The findings suggest that a significant proportion of participants place importance on sustainability when buying textile products, with a considerable number acknowledging its value in their decision-making process.

Participants who indicated that they consider were further queried about the specific sustainability factors they prioritize (MC). The two most mentioned factors were sustainable materials and item durability, followed by sustainable production processes. In smaller proportions, participants also highlighted the importance of certifications items possess and the type of packaging used. These choices are visually represented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Sustainable factors considered by participants prioritizing item sustainability.

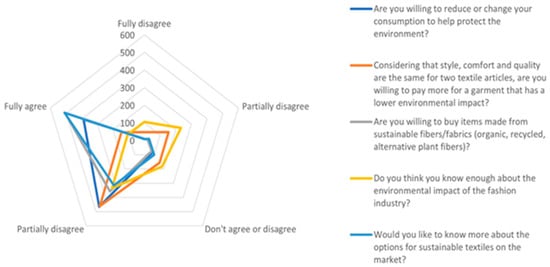

Participants were presented with a series of questions concerning their willingness to adopt sustainable behaviors, to which they responded using a five-point Likert scale. The radar chart in Figure 6 indicates that most participants were ready to embrace the suggested behaviors. Notably, opinions were divided when participants were asked about their level of knowledge regarding the environmental impact of the fashion industry. A considerable number remained undecided, while a larger group partially disagreed, and the majority partially agreed. Furthermore, most expressed a keen interest in learning more about the sustainable options for textile items available in the market.

Figure 6.

Perceived potential for changing behaviors towards sustainability.

When presented with the hypothesis of a social score being added to the label of textile products indicating the fairness of labor conditions and company practices (DC), most participants (61%) indicated this would be an influencing factor. In comparison, 31% stated that it would be an influencing factor, but it would not be a determining one.

Participants were asked about their habit of reading labels before buying products (DC), with the results being somewhat divided, as the majority (53%) stated they possess that habit, and 39% of participants stated they do not have the habit of reading labels before purchasing items.

The participants who indicated the habit of reading labels prior to product purchase were questioned on the perceptibility of ecological certificates on labels (DC). Of these, the majority (83.3%) stated not finding this information easily perceptible, while only a small minority (16%) stated finding this information perceptible.

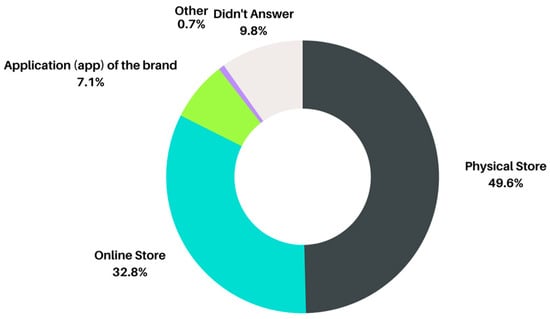

When asked what platforms they use to gather information about products (MC), the main source of information indicated by participants (51%) remains physical stores, while 33.8% of participants prefer online stores for this purpose. A smaller percentage of participants rely on brand applications to obtain product information before making a purchase (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Most accessed points of sale used to obtain information on textile articles, expressed as a percentage of all choices.

When asked about their preferred method of accessing product information (MC), a majority of participants (49.75%) indicated a preference for accessing it through the product label, while 33.7% expressed a preference for using visual codes such as QR or barcodes. A small number of participants (8.17%) showed interest in obtaining this information through an NFC (near field communication) smart tag, which is a technology standard that facilitates secure, short-range wireless connectivity, allowing fast, bidirectional interactions between electronic devices [].

Participants were asked whether they engaged in the practice of sharing textile items (DC), with the vast majority (63.19%) indicating that they did not have this habit, while a smaller portion of participants (30%) reported sharing textile items.

For participants who reported sharing textile items, the majority of responses (89.5%) indicated that they share with family members. A significant portion (41.8%) also tended to share with acquaintances, while a smaller percentage (13.3%) indicated sharing with unknown individuals.

When asked whether they tend to rent textile items (DC), only as much as 1% of participants displayed this habit. 92.4% of participants stated not having the habit of renting textile items.

Having been queried on the habit of purchasing second-hand clothing (DC), a small share of the sample (21.3%) demonstrated the use of second-hand when purchasing textile items. 71.8% of participants stated not using these platforms.

4.2. Use Phase

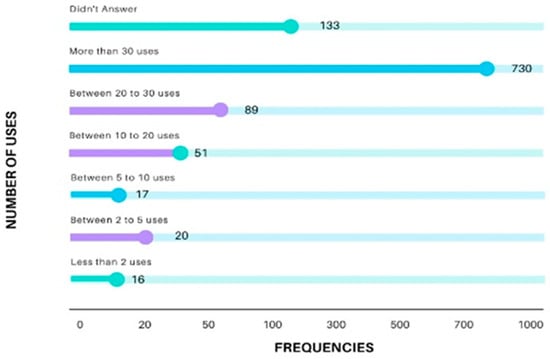

When asked about the number of uses of a textile item from acquisition to discard (MC), most respondents claimed to have used items over thirty times during their life cycle, while a minority stated using them up to or less than 30 times. Results are detailed in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Average times used for a common textile item.

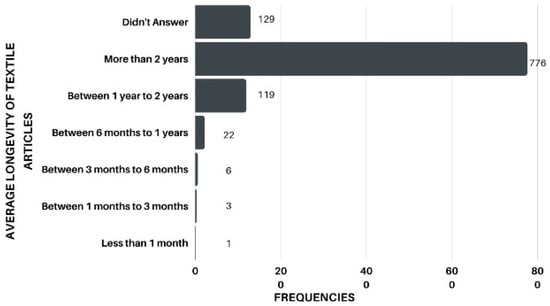

Participants were asked about the longevity of their textile items (MC), with most respondents (73.5%) reporting that they kept their textile items for over two years before discarding them. A small proportion (12.2%) chose not to respond to this question. Figure 9 illustrates the distribution of these results.

Figure 9.

Longevity of textile items, expressed in frequency of choice.

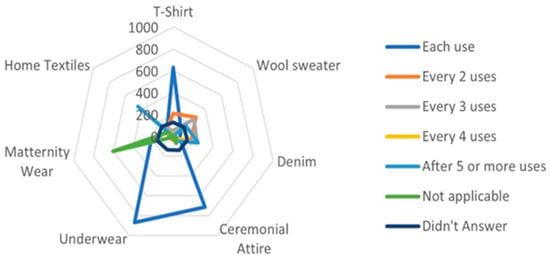

Participants were asked how often they wash different types of clothing items (LS). As shown in Figure 10, participants exhibited varying washing frequencies for different items. T-shirts and maternity wear were commonly washed after every use, while ceremonial attire and home textiles are washed less frequently as intervals vary between two and five or more uses.

Figure 10.

Average frequency of washing per textile item, expressed as the frequency of choice.

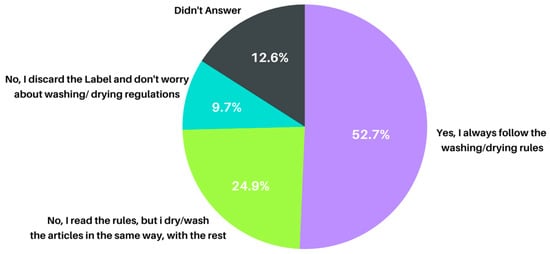

When asked about compliance to textile label directions (MC), most participants (52.7%) tend to follow label recommendations when washing and drying items, while a smaller, yet still significant, proportion of participants (24.7%) indicated reading the labels but disregarding the information and washing all items in the same manner. A smaller portion of the sample indicated discarding the label and not being concerned about following its recommendations. The results are displayed in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Tendency to follow label recommendation when washing/drying textile items, expressed as a percentage of choice.

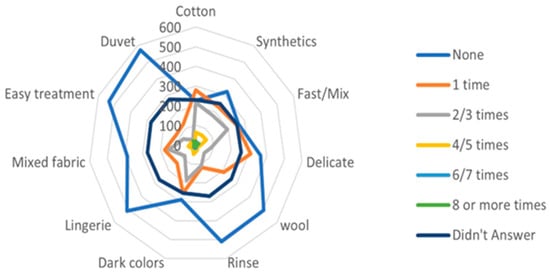

Participants were questioned about their clothes-washing habits (LS). The radar chart in Figure 12 presents the distribution of average uses for washing machine programs over a week. It is possible to observe that most programs are used very little, with most participants stating they do not use them at all; an example is the cotton program. Other programs, such as rinse and duvet, show a more balanced use.

Figure 12.

Average amount of uses for each washing program listed per week.

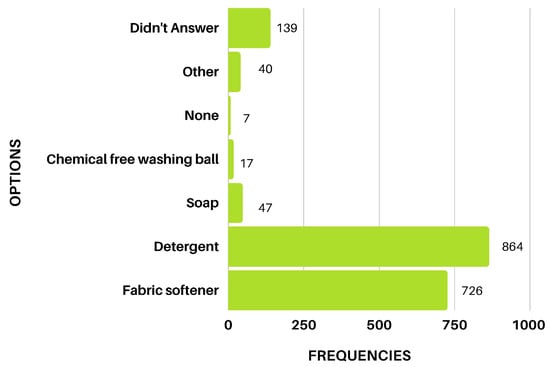

When asked about their concerns with using chemical items in clothes washing (DC), a large portion of the sample (60.5%) indicated concern with using chemical items during the washing of textile items, while 28.9% indicated not having this concern.

Respondents were asked which chemical items they use in clothes washing (MC). Most participants use detergent and/or fabric softener in washing, while a smaller percentage of participants use soap and chemical-free washing balls. A smaller percentage of the sample (0.66%) do not use chemical items in washing textiles. These results are made explicit in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Product usage in clothes washing expressed as the frequency of choice.

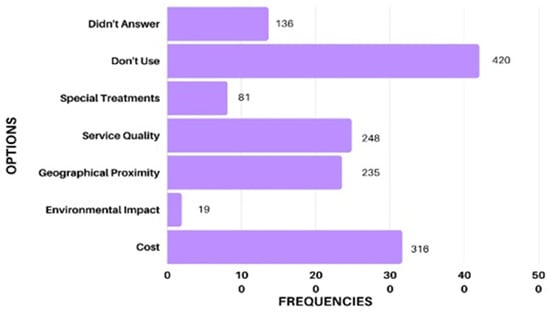

Participants were asked about their use of third-party clothes-washing services (MC). A large portion of participants (39.77%) do not use third-party services for washing, drying, or ironing clothes. Similar amounts of participants value the cost, quality, and geographical proximity of the service (see Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Factors influencing the use of third-party services for washing, drying, and ironing textile items.

When asked about how they dry items (MC), most participants (77.4%) do not use a tumbler dryer to dry textile items and prefer to dry items in the open air. A smaller share of participants (13.4%) usually choose to use tumble dryers.

4.3. Maintenance Phase

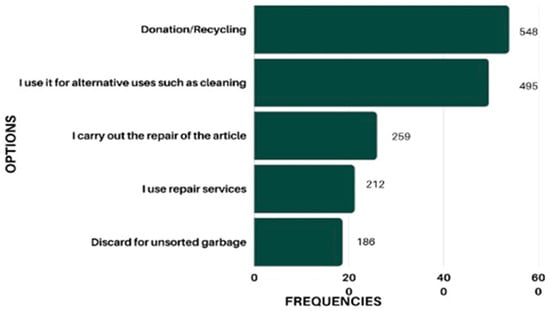

When asked how they handle a damaged textile item (MC), the largest portion of participants (50.9%) opt to handle it by either donating or recycling it through textile item collection containers. Another considerable percentage of respondents (46.9%) prefer to repurpose the item for alternative uses (i.e., cleaning). In comparison, a smaller percentage of participants (17.6%) choose to dispose of the damaged items as regular undifferentiated trash, while 20.1% opt for professional repair services. Additionally, a substantial number of participants decided to repair the article themselves. These responses are visually depicted in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Preferred treatment of damaged items, expressed as the frequency of choice.

During the survey, participants were asked about their attitudes toward repairing damaged textile items (MC) and their willingness to invest in repair services (MC). Remarkably, the majority of respondents (65.6%) displayed a keen interest in paying for item repair services. In contrast, a considerable portion (25.9%) stated that they preferred to handle the repair themselves without relying on third-party assistance.

Curiously, when asked about the specific percentage of the item’s value they would be willing to spend on repairs (MC), no responses were received. Consequently, no valid answers are available for this question. This finding suggests that respondents may hold diverse perspectives on the cost–benefit ratio of repair services concerning the item’s value.

Lastly, when queried about their preferred third-party repair services (MC), most participants (78.9%) mentioned utilizing the services of a familiar seamstress. A smaller percentage opted for branded external repair services (8.2%), while an even smaller fraction chose brand repair services (4.6%).

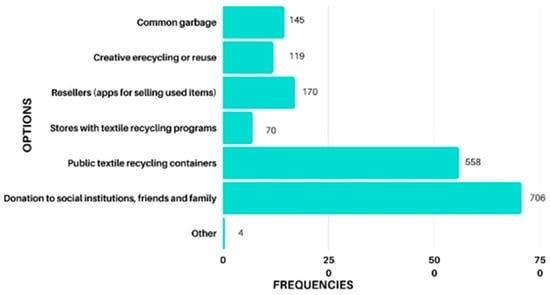

4.4. Discard Phase

Respondents were asked for their preferences regarding item disposal (MC). In Figure 16, the results strongly depict the participants’ thoughtful choices when handling textile items. A substantial majority (66.9%) donate items to social charity institutions or friends and family. To promote sustainability, a noteworthy portion (52.8%) actively engage with public textile item recycling containers to discard their textiles responsibly. Additionally, a smaller yet environmentally conscious portion (16.1%) seizes the opportunity to resell items, giving them a new lease on life. These insightful findings provide valuable insights into the participants’ eco-conscious behaviors and contributions to a more sustainable and compassionate world.

Figure 16.

Most used forms of discard for textile items expressed as the frequency of choice.

Participants were asked if they had a preference for a time of year to dispose of items (MC). A significant proportion of participants (64.8%) prefer not to designate a specific time of year to discard textile items, whereas 24.6% actively choose specific periods for disposal.

The participants who opted for a specific time of year to discard items were asked what this time was (MC). The majority (73%) prefer the change of seasons for this purpose. Meanwhile, a portion (21%) finds the vacation period ideal for decluttering and rejuvenation. Finally, a minority (3.6%) prefer to combine festive periods with decluttering during special occasions. These distinct preferences reveal the diverse and thoughtful ways participants approach textile item disposal.

When asked what would motivate them to recycle textile items (MC), the most referred reason (chosen by 80% of participants) was knowing that the items being recycled would have a responsible end of life. A smaller portion of the participants stated that receiving a reward would be a reason to recycle textiles, while the minority of participants (4.5%) valued being able to send textile items directly to the brand.

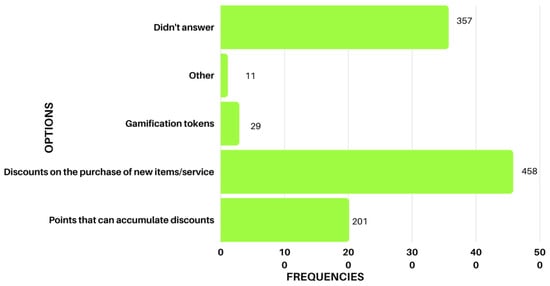

When asked about the possibility of brand compensation for responsible discard campaigns (MC), most participants (68%) feel that when handing over items they do not use back to the brand, they should be compensated. A total of 22.2% of participants stated the opposite: they do not think they should be compensated.

The participants who felt they deserved compensation were asked what form this should take (MC). The majority express a preference for receiving it in the form of discounts on new items or services. A smaller but noteworthy segment favors accumulating discounts for future use. Then, a smaller percentage (2.7%) mentioned the use of gamification tokens as a suitable reward. These results can be observed in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Preferred forms of compensation by brands for handing over items they no longer use expressed as the frequency of choice.

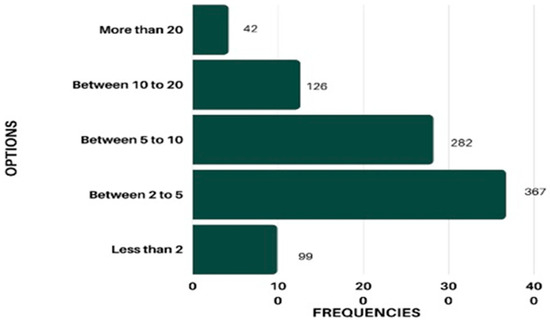

Participants were asked how many items they discard per year (MC). As evidenced by the chart in Figure 18, most respondents tend to discard anywhere from 2 to 5 items per year, while a sizeable portion discards anywhere from 5 to 10 items, and a smaller portion of the sample discards from 10 to 20 or over 20 items per year. The minor portion discards less than two items per year.

Figure 18.

Average amount of textile items discarded per year expressed as the frequency of choice.

5. Discussion

This study presents a comprehensive analysis of the results obtained by applying the questionnaire be@t to a sample of 1026 participants during the first semester of 2023. The questionnaire is organized into four sections, including questions on the acquisition, use, maintenance, and disposal of textile products. Throughout this study, it was possible to explore several issues related to consumers’ habits, preferences, and attitudes towards textile products, as well as the Portuguese consumer’s perception of sustainable practices and the textile sector. The results revealed valuable insights into consumers’ environmental concerns, the importance of clear and accessible information, the adoption of conscious consumption practices, and the willingness to hand over items for recycling.

While this study is inherently empirical in its essence, it is imperative to emphasize that its core objective extends beyond the mere presentation of empirical findings. In addition, the following section was meticulously structured with a practical orientation. This dual emphasis on empirical investigation and practical applicability was a conscious and deliberate choice with the intention to bridge the gap between academic research and its tangible utility in addressing practical, real-world challenges.

Thus, in the forthcoming subsections, we will discuss the results of the four key phases of interest in sustainable consumer behavior regarding textiles in a way that can be of value to practitioners, policymakers, and researchers in the field. These phases encompass acquiring, using, maintaining, and disposing of textile products. By organizing our analysis based on these distinct sections, we aim to comprehensively understand consumers’ habits, preferences, and attitudes throughout the entire lifecycle of textile items.

5.1. Acquisition Phase

In the section dedicated to acquiring textile products, the findings highlight a prevalent motivation among participants: replacing old or worn-out pieces. These results suggest that participants value their textile products’ functionality and durability, making purchases only when needed. The average monthly purchases of 0 to 2 textile items demonstrate a conscious consumption pattern, where participants demonstrate a mindful approach to shopping, opting for only essential purchases. This approach may reflect a concern for sustainability and an attempt to avoid over-consumption and reduce waste in consumer behavior.

Yet, on the acquisition side, this study reveals that three main factors significantly influence the purchase of a given textile product: ’price,’ ’quality and functionality,’ and ’comfort.’ Participants express notable concern about product costs, diligently searching for options that align with their household budget. Such financial considerations necessitate industry involvement in establishing affordable price points for eco-friendly products—a topic well-explored in the existing literature, assessing consumer willingness to pay []. From the perspective of TPB, it is possible to imagine that this preference of the consumer to purchase products based on price, quality, and comfort could be derived from the relative favorability of this attitude when compared with the favorability of purchasing products based on their sustainability []. This does not necessarily stem from a negative attitude towards purchasing sustainable products, but rather, while it can be seen that respondents have generally positive attitudes regarding sustainable products, they might be more driven—have a more favorable attitude—towards buying products that are more financially responsible. Similarly, there may be social pressure from the in-groups for financial responsibility rather than environmental or social responsibility []. This speaks volumes to industry pricing of more sustainable items and the need to lower pricing to negate this effect.

Beyond financial aspects, participants also prioritize purchasing products of excellent quality that fulfill their practical needs, ensuring the item’s longevity without compromising comfort during use. These three factors combined underscore a balanced decision-making approach, wherein financial considerations and the overall excellence of textile products are judiciously weighed. On the other hand, the factors of ‘sustainable production and distribution’, ‘labor conditions and social responsibility’, and ‘ease of purchase’ seem to have lower priority in deciding to buy textile products since they were mentioned by a very small portion of the sample. The literature suggests that sustainability, both environmental and economic, as well as price, have a combined effect on product evaluation []; however, the results of this questionnaire show that there is still some way to go with consumers for sustainability to become a widespread consideration at the final moment of the purchasing decision.

While past findings suggest that most respondents currently do not prioritize sustainable concerns during their purchase decisions, it is crucial to emphasize that they have a notable desire to change this behavior. Based on this study, most respondents reported being willing to reduce or modify their consumption pattern, paying more for garments with lower environmental impact and/or purchasing products composed of sustainable fibers or fabrics. These results reveal a positive momentum towards more sustainable practices in the fashion industry, suggesting a genuine desire to take action to reduce environmental impact and promote more conscious consumption. With the right behavioral intentions, even with a lack of action, it is clear interventions in the form of social marketing [,] should be focused on addressing the barriers to sustainable behavior, such as the above-mentioned attitude [] and social pressure [,] regarding the price and perceived quality of items while emboldening the positive intentions of consumers. Considering that this is the general trend within the sample, it is also possible to consider the effects that emboldening these attitudes have on the social dynamics of in-groups [,], as large groups sharing overwhelmingly positive attitudes towards sustainable behavior may provide adequate antecedent conditions [] for the activation of the personal norms, which have shown to be overwhelmingly based on positive values towards environmental and social sustainability [].

It is noteworthy that participants expressed a keen interest in acquiring information about the products they purchase, actively reading the labels of textile items. The increased availability works to counteract misinformed beliefs regarding sustainable products, which in itself is hugely important in the formation of personal norms. In their quest for knowledge, both physical and online stores are perceived as crucial sources of information about products, practices, and available options. Regarding textile product labels, which were described as the preferred means to obtain information about the item, these data reveal that less than half consider that the information presented on the labels is perceivable, which indicates that there is a need to improve the clarity and comprehensibility of the information provided to consumers to meet their expectations and facilitate informed decision-making []. This is supported by findings reported in the literature that consumers do not understand sustainable fashion production []. In fact, while industry and government are working on solutions to the availability of information on the sustainability of products with initiatives such as the Digital Product Passport [,], these findings also suggest that there is much literacy work to be conducted regarding the textile sector and the practices that are currently in place, which could merit industry involvement in consumer education by means of social marketing [], as well as in the labeling of sustainable products []. However, one positive aspect is that most respondents express a desire to attain more information about the sustainable textile options available on the market. This expression of interest highlights the need for greater outreach and education on existing sustainable options to empower consumers to make more informed and conscious choices.

Most respondents also consider that the way companies treat their employees (i.e., social score) is a relevant factor for the purchasing decision. This awareness demonstrates a growing concern about working conditions and the social responsibility of brands and companies. This is corroborated by the literature, as previous studies demonstrated consumers care about companies’ interactions with sustainability [].

The apparent reluctance of respondents to buy second-hand reused clothing could be due to their perception of risk in product functionality. Some authors have pointed out risk perception when purchasing a recycled product []. Consumers may perceive risk in the performance of a recycled product compared with a new product, affecting the price they are willing to pay to change from a recycled to a new product []. This reluctance could impact the application of certain sustainable practices of textile consumption, such as collaborative consumption in fashion and the clothing library []. Regarding the sharing of textile items, the results indicate that this practice is rare for most participants, with almost all reporting not having the habit of sharing or renting garments or using second-hand purchase platforms. TPB may be useful in explaining this reluctance, as a negative attitude to this behavior may hinder its adoption [,]. This attitude may well be explainable, as well, in a collective sense through SIT and NAM, as an in-group with overwhelmingly negative views on alternative consumption practices will hinder norm activation [,,].

5.2. Use Phase

More than half of the participants show concern about using chemicals in washing their textile items, with a preference for drying items outdoors and without using third-party services (e.g., dry cleaners). Consumers appear to demonstrate a combination of self-sufficiency in carrying out washing, drying, and ironing services for textiles and a vital consideration for the costs associated with outsourced services. Although most respondents demonstrated attentiveness in reading and adhering to care labels, a significant portion reported ignoring or disposing of these instructions. Those who opted to discard or disregard the clothing item labels might have encountered difficulty identifying the symbols depicted [], a pattern reminiscent of findings from a study conducted on a student population. Students frequently overlooked the label information in that study and struggled to comprehend the instruction [].

5.3. Maintenance Phase

The results further reveal that most participants prefer to give alternative uses to damaged textile items, such as using them for cleaning purposes or opting for proper disposal in textile collection containers for donation or recycling. This demonstrates a concern for sustainability and making the most of items when they are not in optimal condition. Participants also say they are willing to pay for the repair of their textile items, which reflects the importance they place on extending the life of items rather than discarding them prematurely. When they resort to repair, they prefer known sewists, reinforcing the importance of relationships with professionals specialized in the maintenance of textile items.

In the context of selecting a service provider, consumer trust in both personnel and the store holds significant importance []. In the specific case of the preference for known sewists within the Portuguese textile consumer culture, one noteworthy factor to consider is the prominence of women in the clothing manufacturing industry. This aspect potentially influences the level of trust in these services, particularly as gender roles continue to evolve in the job market []. Consumers might link familiarity with the service providers, particularly in communities where interpersonal connections hold a crucial role in building trust. It is essential to acknowledge that trust is a multifaceted construct influenced by various social, cultural, and individual factors. Trust in corporate social responsibility practices has shown to be a critical factor in positive consumer revisiting intention []. This effect has been studied within consumer-fashion brand relationships, as consumers need to perceive brand actions towards social responsibility as altruistic, with trust being a direct predictor of purchasing intention []. Therefore, understanding the specific drivers of consumer trust in known sewists within the textile consumer culture would likely require additional research, considering aspects such as community dynamics, historical gender roles, and the significance of interpersonal relationships in the decision-making process. This could also be a clear case of the effect of social acceptance of practice within in-groups [,], as well as the formation of a subjective norm, amplifying the adoption of this practice, speaking volumes to the value of both SIT and NAM in the promotion of sustainable practices [,,].

5.4. Disposal Phase

In the disposal phase, the findings reveal that over half of the participants practice conscious disposal, opting to donate textile items to charities, friends, and family or using recycling bins. The primary motivation for donation appears to be the belief that the items will be responsibly handled at the end of their lifecycle, showcasing an understanding of recycling’s environmental impact reduction and its role in the circular economy, speaking to the value of prescriptive and descriptive beliefs in the activation of personal norms. These choices highlight a concern for responsible disposal aimed at minimizing waste and contributing to sustainability. The literature points out the values observed by consumers when disposing and reusing items, pointing out that resale and donation behaviors can be explained by environmental concerns, while reuse and resale can be explained by economic factors, and convenience was a highly motivating factor for discard habits []. Interestingly, almost two-thirds of respondents believe brands should compensate consumers for handing over items they no longer use. The most desired form of compensation is through discounts on the purchase of new items or services. This reveals consumers’ expectations to be rewarded for their sustainable actions, encouraging them to continue participating in responsible disposal practices. These results highlight the importance of shared responsibility between consumers and brands in properly managing textile articles, promoting sustainability, and the valorization of natural resources.

Exploring consumers’ perceptions of whether brands should compensate them for handing over items they no longer use is relevant to understanding consumers’ perspectives on the role of brands in managing discarded products, to guide corporate social responsibility strategies [], considering, for example, the implementation of incentive programs or rewards to encourage consumer participation in these processes. Offering incentives can encourage consumers to opt for more sustainable options, such as recycling or donating, rather than simply discarding textile products, while arguably serving as recognition of value, therefore galvanizing beliefs [,,], which in turn will strengthen the positive attitude towards responsible disposal in a MSC environment [], and facilitating the formation or validation of personal norms [], while serving, as well, as a motivator for the activation of those same personal norms []. In addition, if brands demonstrate a commitment to compensating consumers for proper disposal, this can build consumer trust and loyalty, with this being hugely advantageous for MSC []. In fact, institutional product buyback and program convenience positively affect brand satisfaction [].

5.5. Strengths and Limitations

It is important to underline certain limitations found within this study. Among these, perhaps the most important is the stark heterogeneity of the sample, noticeable, especially in its female majority, as well as the fact that the large majority of respondents were found to reside in the North of Portugal. There is a need to validate the survey, as it was created specifically for this study. A focused study on the validation of the survey would be beneficial to the validity of the present article.

Along with its limitations, it would be important, as well, to mention the strengths of this study. This study presents an inquiry into a topic of the utmost importance with its focus on the study of the fashion consumer and their relationship with sustainable development. The study of this population’s perspective through the lens of social psychology is hugely beneficial and can be made to inform future inquests of social marketing to encourage the adoption of sustainable consumer behavior more effectively in the clothing and textiles industry. Along with the focus on an important topic, this study presents a new tool in the form of the survey Questionnaire be@t, which, after proper adaptation and validation, could prove beneficial for future studies.

5.6. Prospects for the Future

Data elucidated in this study offer intriguing hypotheses that hold the potential to guide forthcoming research endeavours. Specifically, in terms of the acquisition phase, it would be considered interesting to investigate whether a discernible correlation exists between perceived financial considerations and the preference towards price-centric textile purchases. Additionally, it may also be important to explore whether perceived societal pressure for financial responsibility exerts a deleterious influence on the receptivity towards sustainability-driven purchasing attitudes. An inquiry into this hypothesis would undoubtedly augment our comprehension of social in-group dynamics in sustainable behavior, particularly within the demographic described, characterized by a conscientious concern for the financial aspect of clothing acquisition.

Furthermore, focusing on a more comprehensive examination of the utilization practices among textile consumers is warranted. It is conceivable that a prospective hypothesis, guided by these data under consideration, posits that consumers demonstrating self-sufficiency in laundering and maintenance of textile items may show a predisposition towards more eco-friendly practices. This may manifest in a preference for outdoor drying of clothing items or the avoidance of third-party services. Also, it would be worthwhile to scrutinize the hypothesis that consumers’ willingness to read and adhere to care labels on textile items correlates positively with the intent to engage in sustainable laundering and maintenance behavior.

In terms of item maintenance, one could advance the hypothesis that consumers who express a predilection for giving alternative use to damaged textile items are more likely to have a heightened concern for sustainability and a commitment to prolonging the life cycles of textile products.

Finally, it is plausible to posit the hypothesis that consumers who endorse conscientious disposal practices for textile items at the end of their life cycles are more inclined to hold affirmative descriptive beliefs regarding the potential impact of recycling in mitigating environmental consequences, indicative of a more pronounced alignment with sustainable values.

6. Conclusions

This study uncovers a promising trajectory towards embracing sustainable textile consumption practices involving various stakeholders, including government, industry, and the consumer. Through an exploration of consumers’ habits, preferences, attitudes towards textile products, and their perception of sustainable practices in the textile sector, this research aims to unearth the fundamental elements that can sow the seeds of positive transformation within the fashion industry.

Our findings indicate a noticeable shift in consumers’ mindset towards more sustainable consumption. However, it also underscores the necessity of expanding access to information and sustainable product options. Consumers are increasingly conscious of the social and informational dimensions connected to textile products and seek greater transparency and accessibility from brands. The concerns suggest a paradigm shift, with consumers emerging as proactive agents in fostering a fairer and more sustainable economy through purchasing decisions. As a result, companies that embrace socially responsible practices and demonstrate transparency regarding labor policies are more likely to attract and retain conscious consumers. Moreover, the fact that consumers actively seek eco-certifications sends a clear message to the industry, signaling a growing demand for sustainable products and encouraging continuous improvement in environmental practices within the textile production sphere.

The results present a clear opportunity for social marketing interventions, both working to galvanize the positive attitudes consumers already hold and to strengthen the personal norms that drive those positive attitudes. In many instances, social marketing campaigns focused on information must be capable of providing clear and concise information to the consumer in an effort to unravel misinformed beliefs, which both lead to biased and unsustainable personal norms and a negative attitude to certain practices. The adoption of alternative consumption patterns such as the purchasing of second-hand clothing, sharing of items, alternative models such as the clothing library, and the renting of textile items are clear examples of where social marketing campaigns may help unravel the negative attitudes shown to be held by consumers regarding these practices, both through providing better quality information to end the perception that recycled or second-hand products are of lesser quality or comfort and to dispel social bias held within in groups that exclude this practice from the zeitgeist.

Finally, the results indicate that a significant number of consumers face difficulties in understanding sustainability information provided on product labels and finding sustainable textile options. These results underscore a consumer knowledge and awareness gap, potentially obstructing the widespread adoption of sustainable practices. Considering the marketing approach, this finding accentuates the importance of offering transparent information and actively educating consumers about sustainable practices and their profound impact. In this pursuit, brands are pivotal in elevating consumer literacy concerning sustainability, guiding them toward informed and mindful decisions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su152215812/s1; the English version of the questionnaire will be provided as Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.R.R. and P.O.-S. methodology, P.R.R. and P.O.-S.; software, P.R.R.; formal analysis, P.R.R.; investigation, P.R.R. and P.O.-S.; resources, P.O.-S.; data curation, P.R.R.; writing—original draft preparation, P.R.R.; writing—review and editing, P.O.-S., P.B., F.M.-P. and M.P.; visualization, P.O.-S.; supervision, P.O.-S. and P.B.; project administration, P.O.-S.; funding acquisition, P.O.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded through the Portuguese Recovery and Resilience Plan in accordance with the grant: be@T—Bioeconomia para Têxtil e Vestuário, investimento TC-C12-i01—Bioeconomia Sustentável”. Additional funding was provided by the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT), Research Centre for Human Development (CEDH), Project UIDB/04872/2020, Portugal, and Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT), Patrícia Batista, CEECINST/00137/2018, Portugal.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Blanquerna Universitat Ramon-Llull (24 October 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available from authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

In conclusion, we would like to thank several individuals who contributed valuable to this study. Namely, Ana Lia Moutinho, an undergraduate student, and Jessica Qiu, a master’s student, for their assistance in organizing these data using IBM SPSS. Also, we appreciate the contribution of Patrícia Vergara for her invaluable assistance in editing the images used in this study. Finally, we are grateful to Miguel Ferreira, a research assistant from the Human Neurobehavioral Laboratory, for providing valuable insights that contributed to developing the discussion and conclusion. Furthermore, we extend our gratitude to our industry partners from the be@T consortium for their collaboration in designing the questionnaire and promoting it through their social media, websites, and newsletters. Although these team members did not meet the criteria for authorship, their contributions were integral to the success of this research project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. The 17 Goals; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Coscieme, L.; Mortensen, L.F.; Donohue, I. Enhance Environmental Policy Coherence to Meet the Sustainable Development Goals. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 296, 126502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, O. Sustainable Development Goals: Improving Human and Planetary Wellbeing. Glob. Change 2014, 82, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Halati, A.; He, Y. Intersection of Economic and Environmental Goals of Sustainable Development Initiatives. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 189, 813–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hediger, W. Sustainable Development and Social Welfare. Ecol. Econ. 2000, 32, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koltun, P. Materials and Sustainable Development. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2010, 20, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Program. The SDGs in Action; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Niinimäki, K.; Peters, G.; Dahlbo, H.; Perry, P.; Rissanen, T.; Gwilt, A. The Environmental Price of Fast Fashion. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, S. Sustainable Consumption and Production Patterns in Fashion. In The UN Sustainable Development Goals for the Textile and Fashion Industry; Gardetti, M.A., Muthu, S.S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; Volume 1, pp. 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen, K.; Johnson Jorgensen, J. Millennial Perceptions of Fast Fashion and Second-Hand Clothing: An Exploration of Clothing Preferences Using Q Methodology. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.-J.; Choi, T.-M. A United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals Perspective for Sustainable Textile and Apparel Supply Chain Management. Transp. Res. E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2020, 141, 102010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voola, R.; Bandyopadhyay, C.; Azmat, F.; Ray, S.; Nayak, L. How Are Consumer Behavior and Marketing Strategy Researchers Incorporating the SDGs? A Review and Opportunities for Future Research. Australas. Mark. J. 2022, 30, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castano Garcia, A.; Ambrose, A.; Hawkins, A.; Parkes, S. High Consumption, an Unsustainable Habit That Needs More Attention. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 80, 102241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, V.; Michaelides, M. What Is the Economic Impact of Fast Fashion?—Economics Research Question. Int. J. Sci. Res. Sci. Technol. 2022, 9, 571–581. [Google Scholar]

- Stanescu, M.D. State of the Art of Post-Consumer Textile Waste Upcycling to Reach the Zero Waste Milestone. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 14253–14270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geisendorf, S.; Pietrulla, F. The Circular Economy and Circular Economic Concepts-a Literature Analysis and Redefinition. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 60, 771–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahel, W.R. The Circular Economy. Nature 2016, 531, 435–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Völker, T.; Kovacic, Z.; Strand, R. Indicator Development as a Site of Collective Imagination? The Case of European Commission Policies on the Circular Economy. Cult. Organ. 2020, 26, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winans, K.; Kendall, A.; Deng, H. The History and Current Applications of the Circular Economy Concept. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 68, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum (WEF). Transforming African Economies to Sustainable and Circular Models. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/impact/the-african-circular-economy-alliance-impact-story (accessed on 14 July 2023).

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosnjak, M.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. The Theory of Planned Behavior: Selected Recent Advances and Applications. Eur. J. Psychol. 2020, 16, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelmaged, M. E-Waste Recycling Behaviour: An Integration of Recycling Habits into the Theory of Planned Behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 124182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuriev, A.; Dahmen, M.; Paillé, P.; Boiral, O.; Guillaumie, L. Pro-Environmental Behaviors through the Lens of the Theory of Planned Behavior: A Scoping Review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155, 104660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A Value-Belief-Norm Theory of Support for Social Movements: The Case of Environmentalism. Res. Hum. Ecol. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Ruiz-Menjivar, J.; Luo, B.; Liang, Z.; Swisher, M.E. Predicting Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation Behaviors in Agricultural Production: A Comparison of the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Value-Belief-Norm Theory. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 68, 101408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikienė, G.; Poškus, M.S. The Importance of Environmental Knowledge for Private and Public Sphere Pro-Environmental Behavior: Modifying the Value-Belief-Norm Theory. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative Influences on Altruism. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977; pp. 221–279. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei, R.; Safa, L.; Damalas, C.A.; Ganjkhanloo, M.M. Drivers of Farmers’ Intention to Use Integrated Pest Management: Integrating Theory of Planned Behavior and Norm Activation Model. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 236, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajfel, H. The Achievement of Inter-Group Differentiation. Differentiation between Social Groups; Academic Press: London, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Scheepers, D.; Ellemers, N. Social Identity Theory. In Social Psychology in Action; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 129–143. [Google Scholar]

- Gkargkavouzi, A.; Halkos, G.; Matsiori, S. Environmental Behavior in a Private-Sphere Context: Integrating Theories of Planned Behavior and Value Belief Norm, Self-Identity and Habit. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 148, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, S. Sustainable Consumer Empowerment through Critical Consumer Education: A Typology of Consumer Education Approaches. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2005, 29, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzaoui Essoussi, L.; Linton, J.D. New or Recycled Products: How Much Are Consumers Willing to Pay? J. Consum. Mark. 2010, 27, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Ng, A. Environmental and Economic Dimensions of Sustainability and Price Effects on Consumer Responses. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 104, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adisorn, T.; Tholen, L.; Götz, T. Towards a Digital Product Passport Fit for Contributing to a Circular Economy. Energies 2021, 14, 2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walden, J.; Steinbrecher, A.; Marinkovic, M. Digital Product Passports as Enabler of the Circular Economy. Chem. Ing. Tech. 2021, 93, 1717–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritch, E.L. Consumer Interpretations of Fashion Sustainability Terminology Communicated through Labelling. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2022, 26, 741–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereno, A.; Eriksson, D. A Multi-Stakeholder Perspective on Sustainable Healthcare: From 2030 Onwards. Futures 2020, 122, 102605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, A.; Fayezi, S. Ameliorating Food Loss and Waste in the Supply Chain through Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 93, 328–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrane, F.Z.; Ndubisi, N.O.; Kamble, S.; Karuranga, G.E.; Poulin, D. Building Trust in Multi-Stakeholder Collaborations for New Product Development in the Digital Transformation Era. Benchmarking Int. J. 2021, 28, 205–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Bull. World Health Organ. 2001, 79, 373–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, J.F.; Donoghue, C. Statistics: A Tool for Social Research and Data Analysis; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2020; ISBN 0357371151. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM® Statistical Package for Social Sciences. In IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 29.0.0.0 (241); IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Xu, L.; Pan, K.; Leng, T.; Li, Y.; Danoon, L.; Hu, Z. E-Textile Embroidered Wearable Near-field Communication RFID Antennas. IET Microw. Antennas Propag. 2019, 13, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P. Marketing for Nonprofit Organizations, 1st ed.; Atlas: São Paulo, Brazil, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Lee, N. Corporate Social Responsibility: Doing the Most Good for Your Company and Your Cause; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; ISBN 812651843X. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, J.; Koep, L.; Damert, M. Labels in the Textile and Fashion Industry: Communicating Sustainability to Effect Sustainable Consumption. In Sustainable Textile and Fashion Value Chains; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 257–274. [Google Scholar]

- Zamani, B.; Sandin, G.; Peters, G.M. Life Cycle Assessment of Clothing Libraries: Can Collaborative Consumption Reduce the Environmental Impact of Fast Fashion? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 1368–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiah, A.; Dzramedo, B.E. Students’ Understanding and Use of Information on Care Labels on Clothes. J. Art Des. 2023, 3, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín Gutiérrez, S.S. A Model of Consumer Relationships with Store Brands, Personnel and Stores in Spain. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2006, 16, 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavora, I.; Rubery, J. Female Employment, Labour Market Institutions and Gender Culture in Portugal. Eur. J. Ind. Relat. 2013, 19, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Kwon, J. CSR Perception and Revisit Intention: The Roles of Trust and Commitment. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2020, 3, 607–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, H.L.; Martinez, L.M.; Martinez, L.F. Sustainability Efforts in the Fast Fashion Industry: Consumer Perception, Trust and Purchase Intention. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2021, 12, 571–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joung, H.-M.; Park-Poaps, H. Factors Motivating and Influencing Clothing Disposal Behaviours. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2013, 37, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Frank, B.; Lu, Z. Market Success through Recycling Programs: Strategic Options, Consumer Reactions, and Contingency Factors. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 353, 131003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).