Abstract

We present an easy-to-apply method for assessing the sustainability of infrastructure projects. The proposed methodology consists of determining the evaluation criteria to be applied to the projected infrastructure, considering the three fundamental pillars of sustainability (economic, environmental, and social), quantified according to impact values, in a range from zero to five. Once these were determined and assessed according to the range of impact, we established the sustainability limits or admissible impact limits for each type of infrastructure. The interaction between the sustainability limits assessed for each of the sustainability pillars and the evaluation criteria gives rise to the total influence factor (TIF), which is a value that represents the level of sustainability of the project analysed, according to which it can be classified into one of the five categories included, ranging from minor impact to unfeasible. It also allows for the local identification of criteria to which corrective actions can be applied, with corresponding scores calculated based on a rubric system. The result of the assessment of these corrective measures is the average of the scores of these three aspects. The corrective measures applied to the affected criteria will reduce the TIF and, therefore, increase the sustainability of the evaluated infrastructure.

1. Introduction

Nowadays, when considering the development of an infrastructure, the sustainability point of view must be carefully taken into account since it will have a significant impact on the environment, the economy, and the society [1]. In particular, intercity transport infrastructures lead to urban aggregation and diffusion, greatly boosting regional economic development [2]. In addition, the largest linear infrastructure contributes to landscape fragmentation and impacts natural habitats and biodiversity in several ways [3]. On the other hand, the construction of infrastructures also entails a strong impact on the ecosystem as a result of the actions caused by the project [4].

In 2015, different countries that are part of the United Nations met at the Sustainable Development Summit and developed the 2030 Agenda containing the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [5]. These goals have led most industrialized countries to readjust their strategies to align them with the achievement of the SDGs [6]. Infrastructure projects form an important part of industry and contribute directly to SDG 9 and 11 [7]; so, sustainable infrastructure development and planning become a necessity.

Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate the sustainability of these projects from the three pillars on which sustainability is based: environmental, economic, and social [8], as well as to understand that a sustainable infrastructure can take different forms, depending on the location and the choices of strategy in the transformation process.

The environmental factor regards the conservation of environmental heritage and natural resources. It is based on the principle of taking advantage of these resources in the short and long term but without compromising the existence of these resources for future generations [9]. Ecosystem-sensitive project design and nature-based solutions provide flexible, cost-effective, and widely applicable alternatives to mitigate the impacts of climate change [10]. On the other hand, the economic factor is linked to the implementation of an integrated approach with a view to promote responsible long-term growth. The available means of production must be used as efficiently as possible and without compromising future use [11]. Finally, the social factor must take into account that development in countries must be usable by their citizens, covering their basic needs [12]. This has to be accomplished by taking into account cultural diversity and the integration of all citizens into the society, as well as protecting workers’ rights [13]. However, the social factor of sustainability in infrastructure is perhaps the most difficult to consider, since the definition of the criteria that make up sustainability from the social point of view in civil engineering projects is not clearly defined [14]. Social criteria are more or less important depending on the context, the perspectives of the stakeholders, and the stages of the life cycle [15,16]. Taking into account the three pillars of sustainability, the concept of sustainability in infrastructure is likely to take different forms depending on its location, the needs of the population to be served, and the economic availability [17].

In the last decades, some institutions have developed different tools for the evaluation of civil engineering projects, many of them oriented to road infrastructures, in order to introduce the concept of evaluation of Green Infrastructures (GI) and sustainability [18].

The GI assessment systems are the result of a scoring of different criteria that, when weighted, summed, and compared with admissible limits, will establish the degree of sustainability of the infrastructure. This scale ranges from nonsustainable to sustainable [19]. Thus, there are several tools for assessing the sustainability of infrastructure projects. One of these tools is STARS [20], developed in 2019 by three transportation agencies in the Pacific Northwest in the USA, and which can be used to plan the type of transportation project to be built and how it is operated. The Canadian Guide for Greener Roads [21], developed in 2015 by the Transportation Association of Canada, can be applied during the planning, design, construction, and development of the project, also including operations and maintenance.

Other evaluation tools are INVEST [22] and I-LAST [23], both developed in 2012 in the USA by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) of the US Department of Transportation and the Illinois State Department of Transportation, respectively. INVEST (FHWA 2012) consists of a set of best practices aimed at identifying, recognizing, and promoting efforts beyond sustainability in transportation programs and projects. Its objective was to provide guidance to practitioners in assessing the sustainability of their transportation projects and programs and to promote the progress of sustainability in the transportation field. On the other hand, I-LAST [23] is a tool that can be applied during project scoping, at the end of the design phase, and during construction. It consists of a checklist of sustainable practices with points assigned to each practice in nine categories and 25 subcategories. It is an easy-to-use tool that requires minimal time and effort, although it does not provide a level of certification.

In 2011, the Institution of Civil Engineers of the UK developed CEEQUAL [24], which is a system for assessing the sustainability of civil projects in the design and construction phases by measuring the performance of different criteria. CEEQUAL-trained evaluators assess project/contract strategy and performance following a scoring system that includes a series of environmental and social issues organized into nine sections and 48 subsections from the perspective of the three key stakeholders (clients, designers, and contractors) involved in the project.

Envision, created in 2012 by the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Harvard Zofnass Program for Sustainable Infrastructure and the Institute for Sustainable Infrastructure (ISI), aims to assess the overall contribution of infrastructure projects regarding sustainability [25]. This comprehensive approach to infrastructure development seeks to evaluate projects based on their value to communities, efficient use of funds, and contribution to long-term sustainability. It likewise considers all aspects of the life cycle, allowing for better-informed decisions at all stages, from planning to deconstruction or decommissioning [26]. The ISI rating tool differs from other rating systems because it uses a much more detailed level of communication between the main parties involved in the projects during the rating process. In addition, unlike other rating systems, it allows for greater flexibility in meeting the criteria required for its application [27]. Other remarkable tools are GI-Val [28] and Greenroads [29], both from 2010 and GreenLITES [30] from 2008.

The evaluation systems analysed are based on the assessment of different indicators that reduce the complexity of the data, simplify interpretations and evaluations, and facilitate communication between experts and nonexperts. In addition, these evaluation methodologies help in the decision-making process to improve the execution of the infrastructure project towards sustainable development, and their main mission is to minimize the environmental, economic, and social impacts throughout the project life cycle.

Within this group of tools for assessing the sustainability of civil engineering projects, the following stand out for the comprehensive approach proposed in their implementation: Envision in the United States [31,32], CEEQUAL in the United Kingdom [24], and the Infrastructure Sustainability Rating Scheme in Australia [27]. These projects reflect various aspects of the sustainable development of a wide range of infrastructure projects [26]. Therefore, these are the models for the design of this methodology.

Regarding the normative point of view, ISO/TC 59/SC 17 [33] and ISO/TS 21929-2:2015 [34] are the available standards for the development of engineering projects. The ISO/TS 21929-2:2015 standard deals with adapting general sustainability principles to civil engineering projects and includes a framework that develops sustainability indicators to be used in the evaluation of projects according to economic, environmental, and social impacts. According to the above-mentioned standards, the indicators may include quantitative and/or qualitative descriptive metrics that provide information about a complex experience, such as the dynamic built environment, in an easy-to-use and understandable way [35].

Based on the regulations and the evaluation tools analysed, the objective of this work consisted of developing a methodology for the evaluation of sustainability in the short, medium, and long term in infrastructure projects, trying to integrate different views of the criteria and factors that are included in the project and the applied environment. The matrix created for this purpose covers the three pillars of sustainability (environmental, economic, and social). This matrix has different criteria evaluated by means of a scale of values from one to five, which, added together and weighted, result in the so-called total influence factor (TIF) and represent the sustainability of the project. In short, it is an easy-to-apply method for assessing the viability of infrastructures and provides objective data for the decision-making process in the choice of alternatives in infrastructure projects.

2. Materials and Methods

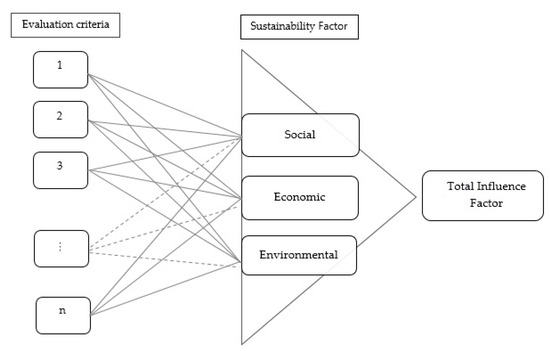

The tool for assessing the sustainability of infrastructure projects by estimating the influence factor (TIF) is the result of a thorough review of the existing methodologies, as well as the ISO standards previously mentioned. Figure 1 shows a simplified scheme of the structure of the proposed model, where it can be observed that different evaluation criteria have a certain influence on the three sustainability factors and, all this in turn, on TIF.

Figure 1.

Structure of the proposed model for sustainability assessment in infrastructure projects.

The proposed model is flexible because sustainability factors can be included or extracted depending on the planning of the evaluated infrastructure. It is only necessary to change the weighting or importance that each factor will have in the TIF. In brief, the methodological steps are the selection of objectives, sustainability factor evaluation criteria, calculation of sustainability limits (TIF), and application of corrective actions when necessary.

2.1. Selection of Objectives

The defined objectives, considering the pillars of sustainability, are as follows:

- -

- Minimum residual impacts on the environment;

- -

- Profitability from the economic point of view;

- -

- Maximum functionality for users;

- -

- Maximum benefit for the affected territory.

2.2. Assessment Criteria

The definition of the evaluation criteria as the set of variables that relate to alternatives and objectives will allow us to assess the degree of approximation of each of the alternatives to the objectives. Table 1 shows the 20 general evaluation criteria, defined as having an impact on the sustainability factors. Of these, 12 correspond to the environmental factor, 2 to the economic factor, and 6 to the social factor.

Table 1.

General evaluation criteria with impact on sustainability factors.

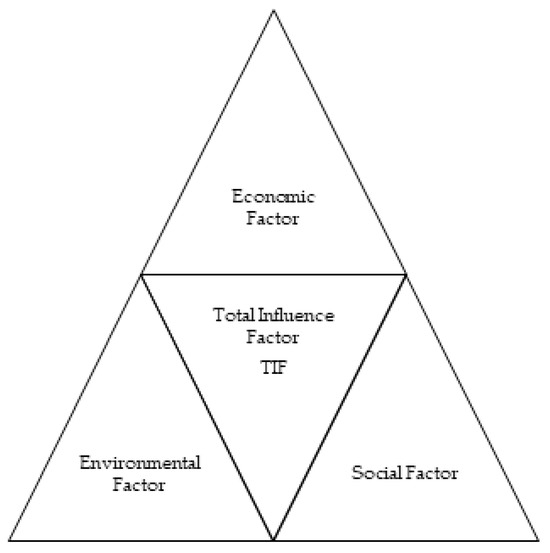

Figure 2 shows the diagram of the relationship between the total influence factor (TIF) and the sustainability factors so that the influence of three of them on TIF can be observed.

Figure 2.

Diagram of direct organization of sustainability factors.

All assessment criteria can be quantified according to the impact values, which are in a range from 0 to 5, where 0 indicates that the criterion does not affect the evaluated sustainability factor and 5 indicates that it has a very high negative impact on the factor. Table 2 shows the breakdown of the intermediate values.

Table 2.

Impact value, definition, and description of the assessment criteria, indicating in every case whether corrective actions are needed or not, and extension if needed.

The use of the numerical values in the first column of Table 2 simplifies the evaluation process, as the significant figures may underestimate or overestimate some of the sustainability factors.

2.3. Sustainability Limits and Total Influence Factor (TIF)

Prior to the evaluation of the infrastructure, it is necessary to define the admissible impact limits or sustainability limits, as well as the weighted relationship between the factors evaluated, in order to obtain the representative TIF of the project.

This sustainability limit will depend on, or be influenced by, the administration (country, autonomous community, region, international agreements, etc.) and by the sustainability trend that the infrastructures are expected to meet, according to the three defined factors, which will adopt a higher or lower assessment depending on the type of infrastructure. These limits are variable and obtained from a statistical analysis of the sustainability factors of similar projects in an informative (initial) study phase.

The proposed method is a tool that allows the assessment of the sustainability of any infrastructure; it will only be necessary to vary the sustainability limits, which will change depending on the specific infrastructure in each case. To do this, it is necessary to collect available data from infrastructures with similar characteristics to those under evaluation.

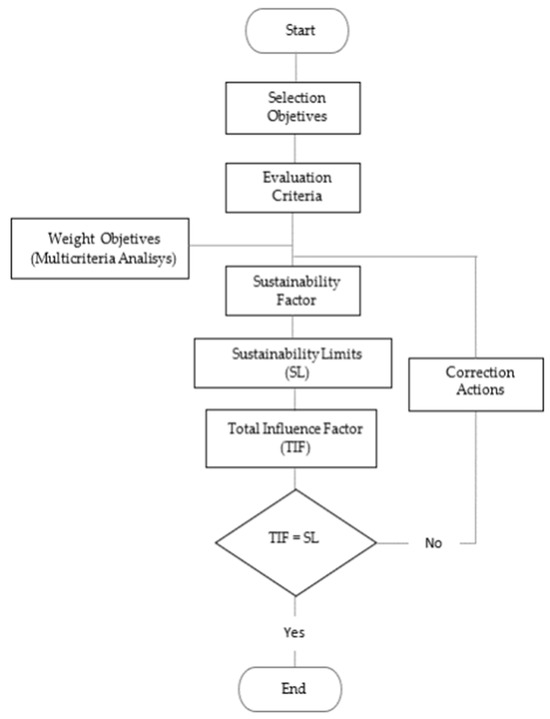

The structure of the model created starts from the use of the weights of the objectives obtained by multicriteria analysis methods for the selection of the best alternative and comparing them with the three pillars or factors of sustainability: social, economic, and environmental calculating a redistribution of the weights of sustainability factors. A simple statistical analysis establishes the sustainability limits (SL). The last step is the estimation of the influence factor (TIF). Figure 3 shows a flow chart of the process followed to develop the proposed model.

Figure 3.

Flow chart of the proposed model.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Application of the Proposed Method for Sustainability Assessment of a Road Project

The data used for the application of the proposed methodology are from road sections in the construction phase available from the Ministry of Transport, Mobility and Urban Agenda of the Government of Spain. The road sections are:

- -

- Road 1: El Villar de Arnedo bypass, Province of La Rioja;

- -

- Road 2: Connection alternatives between the Trujillo–Cáceres Highway (A-58) and the La Plata Highway (A-66) in the area of Cáceres, Province of Cáceres;

- -

- Highway 3: Bypass of the A-1 Highway, Section: Airport Axis Highway junction (M-12) and R-2 Highway, El Molar Bypass, Province of Madrid;

- -

- Road 4: Study of alternatives and development of the solution adopted for the new road connecting the municipalities of Onda and Betxi from “Carrer Tosalet hata Camí D’Onda, 33”, Province of Castellón;

- -

- Road 5: Inca Bypass, Modification of the section between the Ma-2130 (Lluc) and the MA-12 (Palma-Sa Pobla Highway), Province of Palma de Mallorca;

- -

- Road 6: Highway between Ávila (A-50) and the Northwest Highway (A-6).

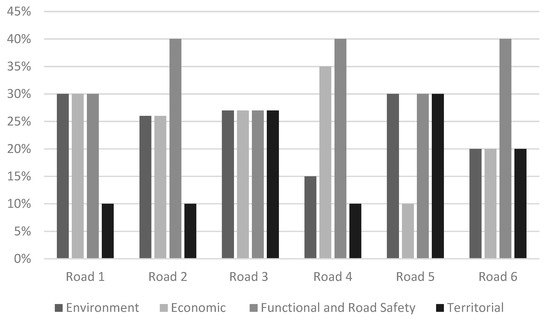

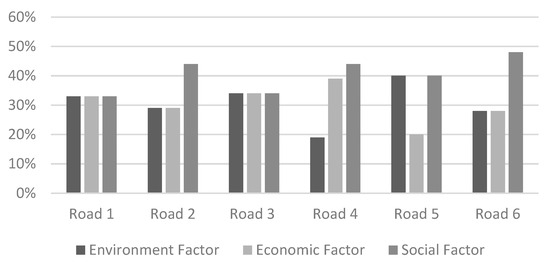

In these informative studies, the Pattern methodology [36] is used to choose the best alternative that a project can have. It is a multicriteria analysis method of total aggregation, where the weights assigned to each of the objectives involved in the calculation are fixed. Table 3 and Figure 4 show the allocation of weights for each of the best alternatives of the roads used in the study.

Table 3.

Summary of weight assignment according to the Pattern method to the best alternative in each one of the roads used.

Figure 4.

Weighting of project objectives for the studied roads.

The comparison of the four objectives with the three factors of the sustainability pillars results in a direct relationship between the environmental and economic objectives and the environmental and economic sustainability factors. Regarding the social sustainability factor resulting from the comparison, it could be associated with the functional objective and road safety. The fourth objective, territorial, has been distributed homogeneously among the three sustainability factors.

where:

Swf = Social weighting factor according to the type of infrastructure;

SO = Functional and road safety objective;

TO = Territorial objective;

Ewf = Environmental weighting factor according to the type of infrastructure;

EO = Environmental objective;

Ecwf = Economic weighting factor according to the type of infrastructure;

EcO = Economic objective;

wf = Weighting factor.

Table 4 and Figure 5 show the redistribution of the weights of the four objectives to the three sustainability factors.

Table 4.

Redistribution of the weighting of objectives and association with sustainability factors.

Figure 5.

Weighting of objectives redistribution and association to the sustainability factors for the studied roads.

The distribution of the objective weights with the three sustainability factors results in a simple statistical analysis of the data, as shown in Table 5. According to this table, the standard deviation of the data is lower than 0.1, a value used in most of the informative studies analysed.

Table 5.

Statistical analysis of objective weights.

Table 6 shows the sustainability limits (SL) for road projects based on the statistical analysis, including the sustainability factor, the limit values, and the descriptions.

Table 6.

Sustainability Limits (SL) for Roads.

The definition of SL for roads allows, in turn, the definition of the TIF, obtained by multiplying the sustainability limits of each evaluation criterion by each sustainability factor; the total sum being the number that represents the level of sustainability of the project analysed. Table 7 shows the classification according to the established ranges.

Table 7.

Data measurement for sustainability factors.

3.2. Assessment of the Infrastructure

As previously mentioned, it is possible to assess the infrastructure in a local and a global way; the local way refers to each of the sustainability factors, whereas the global way refers to TIF. This assessment allows for the cataloguing of the infrastructure project in terms of its sustainability.

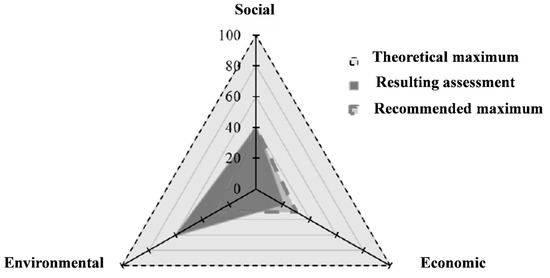

3.2.1. Assessment Triangle of the Project

The impact triangle graphically shows the interaction between the sustainability factors and the assessment criteria, providing visual information on the project evaluation and the admissible impact limits or sustainability limits.

Thus, Figure 6 shows the assessment triangle of the project. This triangle consists of a theoretical maximum of 100 points, which is represented in the triangle vertices for the three sustainability factors; a recommended maximum or a sustainability limit, represented by the triangle with the dashed line and according to the values shown in Table 7; and the results of the sustainability assessment, represented by the solid triangle.

Figure 6.

Assessment triangle of the project.

3.2.2. Classification of the Infrastructure

The TIF calculation estimates the degree of sustainability of the evaluated project. Previously, there was a local evaluation of the infrastructure for each sustainability factor. The TIF calculation expression is:

where:

Se: Sum of criteria scores according to the environmental point of view;

Sc: Sum of criteria scores according to the social point of view;

Sec: Sum of criteria scores according to the economic point of view.

A comparison between the TIF value and the infrastructure rating ranges in Table 7 provides a value. The lower limit for a project to be sustainable without applying corrective measures is 40 points. When the TIF value is higher than 40 points, corrective actions are required. These corrective actions will cause the TIF value to decrease, in order to keep the infrastructure within the admissible range.

3.2.3. Corrective Actions

There are corrective actions that, depending on the evaluation criteria, reduce the negative impacts caused by any of the sustainability factors. They may be differently difficult to implement due to the cost, the space required for their execution, the necessary equipment, the existence or not of qualified personnel for their implementation, etc.

The application of corrective actions is generally needed to reduce the negative impact of an assessment criterion whenever such impact has a value of two or higher, as previously indicated in Table 2.

We propose some corrective actions, with their corresponding evaluations, based on a rubric structure. The development of the rubrics considers aspects, such as human resources, execution times, and implementation costs. Tables S1–S3 show, as examples, four of the rubrics created for this purpose that refer to different evaluation criteria, such as reuse and recycling of materials, cultural heritage, public access, and project risk. The values used for the evaluation have been one and two so that one refers to a simple corrective action and two to a complex corrective action. The result of the evaluation is the average score of the three aspects. Table 8 shows the overall assessment of the corrective actions.

Table 8.

Aspects evaluated for the corrective actions.

The implementation of corrective actions generates an increase in the economic sustainability factor, which implies an increase in the cost of the project. The quantification of this factor is important to determine the possibility of increasing the project in the operation phase. Table 9 shows a summary of alternatives referring to the corrective actions for one of the evaluation criteria for environmental, social, and economic sustainability factors.

Table 9.

Summary of alternatives referring to the corrective actions for one of the assessment criteria for the environmental, social, and economic sustainability factors.

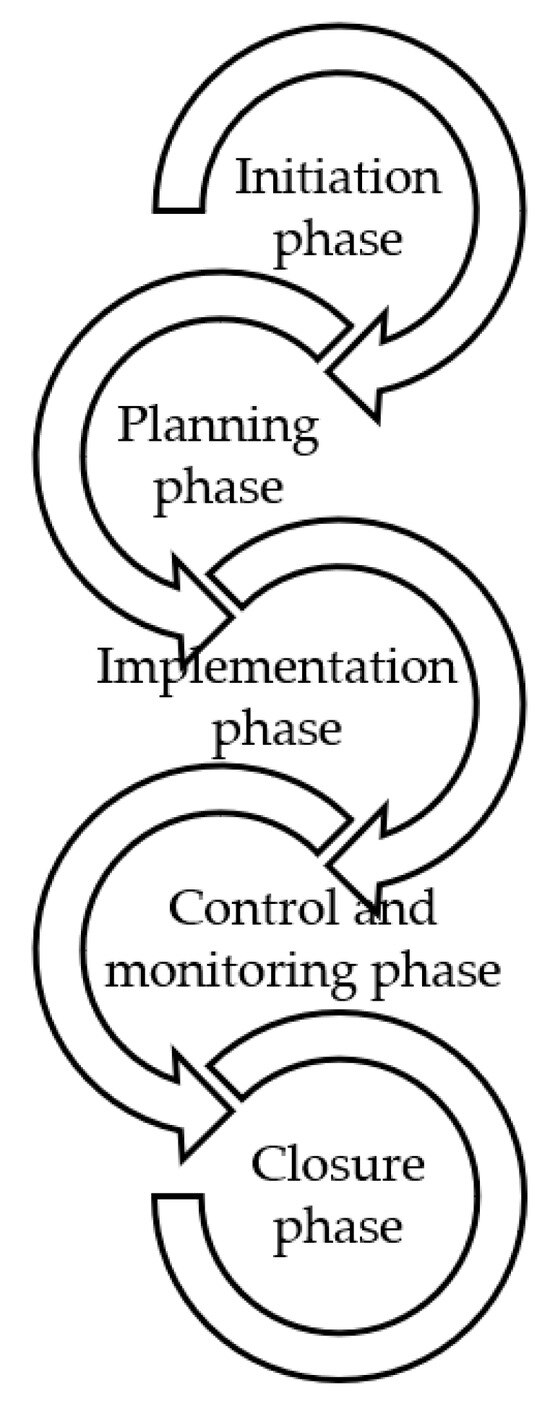

The proposed tool is an efficient method for assessing the sustainability of any type of infrastructure and lifecycle phases (initiation, planning, implementation, control and monitoring, and closure), as shown in Figure 7. For this purpose, it is necessary to choose the sustainability limits that best respond to the characteristics and phase of the life cycle of the project under evaluation.

Figure 7.

Phases of the life cycle of a project.

Compared to the other existing methods, INVEST [22], I-LAST [23], and STARS [20] are only applicable to linear infrastructures, whereas Envision [25] and CEEQUAL [24] are methods that evaluate the sustainability of civil infrastructures in general but based on a certification system that requires a bureaucracy. That certifies whether or not the projects meet the requirements demanded by these methodologies. However, the method developed is not a certification method; it is a measure of project sustainability as an aid in decision-making.

4. Conclusions

The assessment triangle of the project, associated with the TIF (Total Influence Factor), defines the proposed methodology. This factor is calculated after defining the sustainability limits, incorporating a set of estimated corrective actions based on a rubric structure that considers human resources, execution times, and implementation costs with the values of one when it is due to a simple correction action, and two if it is a complex one.

The methodology is applicable to any type of infrastructure. To do this, the following steps must be followed: select the objectives, define the evaluation criteria according to the type of infrastructure, evaluate the variables considered, define the decision rule for the project alternatives, compare with the sustainability factors and redistribute the weights, use statistical calculations to obtain the sustainability limits, calculate the TIF, and incorporate corrective measures in the evaluation in order to make the project sustainable.

For the calculation of the sustainability limits, it is necessary to use real data from similar infrastructures already built, so that the indices calculated are more like the real project and the accuracy is greater. The indices calculated in this paper were on the basis of several road sections, in which the best alternatives have been chosen using a multicriteria selection method called the Pattern method, widely used for this purpose in Spanish infrastructures.

The three pillars of sustainability used as basic criteria are applied depending on the particular characteristics or complexity of the evaluated project, which generates a change in the TIF and the admissible limits. The assessment triangle of the project is useful to understand what the impact index of the project is, as well as if the project itself is feasible or unfeasible.

In addition, if the TIF is above the sustainability limits allowed, a series of corrective actions can be applied (which are included in the methodology and have been assessed through a system of rubrics), which will reduce the value of the TIF and turn the evaluated work into a sustainable project.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su152014909/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.I.M.-L. and E.M.G.-d.-T.; methodology, M.I.M.-L., E.M.G.-d.-T., D.A.-G. and S.G.-S.; software, M.I.M.-L.; validation, M.I.M.-L., E.M.G.-d.-T. and S.G.-S.; formal analysis, M.I.M.-L., E.M.G.-d.-T. and D.A.-G.; investigation, M.I.M.-L., E.M.G.-d.-T., D.A.-G. and S.G.-S.; data curation, M.I.M.-L. and E.M.G.-d.-T.; writing—original draft preparation, M.I.M.-L., E.M.G.-d.-T., D.A.-G. and S.G.-S.; writing—review and editing, M.I.M.-L., E.M.G.-d.-T. and S.G.-S.; supervision, M.I.M.-L. and S.G.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Rodrigo Torres Aguirre, a student of the Master in Infrastructure Planning and Management in Civil Engineering of Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, for his collaboration in obtaining the experimental data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Arce, R.; Gulloón, N. The Application of Strategic Environmental Assessment to Sustainability Assessment of Infrastructure Development. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2000, 20, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhang, L.; Xiong, C.; Wang, R. Transportation and Regional Economic Development: Analysis of Spatial Spillovers in China Provincial Regions. Netw. Spat. Econ. 2016, 16, 769–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardet, X.; Foltête, J.C.; Clauzel, C. Designing a Graph-Based Approach to Landscape Ecological Assessment of Linear Infrastructures. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2013, 42, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.H.; Jang, W.; Han, S.H.; Kim, D.; Kwak, Y.H. How Conflict Occurs and What Causes Conflict: Conflict Analysis Framework for Public Infrastructure Projects. J. Manag. Eng. 2018, 34, 04018019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swilling, M.; Hajer, M.; Baynes, T.; Bergesen, J.; Labbé, F.; Musango, J.K.; Anu Ramaswami, B.R.; Serge Salat, S.S. El Peso De Las Ciudades Los Recursos Que Exige La Urbanización Del Futuro; International Resource Panel: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Marzouk, M.; Othman, A. Planning Utility Infrastructure Requirements for Smart Cities Using the Integration between BIM and GIS. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 57, 102120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clevenger, C.M.; Ozbek, M.E.; Simpson, S. Review of Sustainability Rating Systems Used for Infrastructure Projects. In Proceedings of the 49th ASC Annual International Conference Proceedings, San Luis Obispo, CA, USA, 10–13 April 2013; pp. 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Thacker, S.; Adshead, D.; Fay, M.; Hallegatte, S.; Harvey, M.; Meller, H.; O’Regan, N.; Rozenberg, J.; Watkins, G.; Hall, J.W. Infrastructure for Sustainable Development. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, J.; Callicott, K.M. Ecological Sustainability as a Conservation Concept. Conserv. Biol. 2002, 11, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, J.; Jacobs, S. Nature-Based Solutions for Europe’s Sustainable Development. Conserv. Lett. 2017, 10, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three Pillars of Sustainability: In Search of Conceptual Origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, R.H.W.; Peterson, N.D.; Arora, P.; Caldwell, K. Five Approaches to Social Sustainability and an Integratedway Forward. Sustainability 2016, 8, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallance, S.; Perkins, H.C.; Dixon, J.E. What Is Social Sustainability? A Clarification of Concepts. Geoforum 2011, 42, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, L.A.; Yepes, V.; Pellicer, E. A Review of Multi-Criteria Assessment of the Social Sustainability of Infrastructures. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 187, 496–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labuschagne, C.; Brent, A.C. An Industry Perspective of the Completeness and Relevance of a Social Assessment Framework for Project and Technology Management in the Manufacturing Sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, L.A.; Yepes, V.; García-Segura, T.; Pellicer, E. Bayesian Network Method for Decision-Making about the Social Sustainability of Infrastructure Projects. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 176, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.B.; Elle, M. Assessing the Potential for Change in Urban Infrastructure Systems. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2000, 20, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheryn, D.; Pitman, C.B.D.; Martin, E.E. Green Infrastructure as Life Support: Urban Nature and Climate Change. Trans. R. Soc. South Aust. 2015, 139, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.Y.; Chen, P.H.; Chou, N.N.S. Comparison of Assessment Systems for Green Building and Green Civil Infrastructure. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AASHE The Sustainability Tracking, Assessment and Rating System (STARS). Available online: https://stars.aashe.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/STARS-2.2-Technical-Manual.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2023).

- TAC Transportation Association of Canada. Canadian Guide for Greener Roads Released. Available online: https://www.tac-atc.ca/en/canadian-guide-greener-roads-released (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Federal Highway Administration. US Department of transportation INVEST. Available online: https://www.sustainablehighways.org/ (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- IDOT Illinois Department of Transportation. Livable and Sustainable Transportation Rating System and Guide (I-LAST) Version 2.02. Available online: https://idot.illinois.gov/transportation-system/environment/index (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- BRE Building Research Establishment CEQUAL. Available online: https://www.bregroup.com/services/testing/ (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- ISI Envision (a). Available online: https://sustainableinfrastructure.org/envision/use-envision/ (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Laali, A.; Nourzad, S.H.H.; Faghihi, V. Optimizing Sustainability of Infrastructure Projects through the Integration of Building Information Modeling and Envision Rating System at the Design Stage. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 84, 104013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISCA IS Rating Scheme. Available online: https://www.certifiedenergy.com.au/is-rating (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- DEFRA Green Infrastructure Valuation Toolkit (GI-Val). Available online: https://ecosystemsknowledge.net/green-infrastructure-valuation-toolkit-gi-val (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- University of Washington Greenroads—Rating System. Available online: https://csengineermag.com/university-of-washington-and-ch2m-hill-impart-greenroads-rating-system (accessed on 26 November 2021).

- NYSDOT New York State Department of Transportation. What Is GreenLITES. Available online: https://www.dot.ny.gov/programs/greenlites (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Institute for Sustainable Infrastructure (ISI). Envision: Sustainable Infrastructure Framework Guidance Manual; Institute for Sustainable Infrastructure, ISI: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: https://sustainableinfrastructure.org/wp-content/uploads/EnvisionV3.9.7.2018.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2023).

- ISI Envision (b). Available online: https://sustainableinfrastructure.org/resource/website-tutorials/ (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- ISO/TC 59/SC 17; Sustainability in Buildings and Civil Engineering Works. International Organization for Standarization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

- ISO/TS 21929-2:2015; Sustainability in Building Construction—Sustainability Indicators—Part 2: Framework for the Development of Indicators for Civil Engineering Works. International Organization for Standarization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Al Hazaimeh, I.; Alnsour, M. Developing an Assessment Model for Measuring Roads Infrastructure Sustainability in Jordan. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2022, 7, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, J. Anejo No 10 Análisis Multicriterio. 2014. Available online: https://obraspublicas.navarra.es/documents/8789247/8851029/TBA_Anejo_10_Analisis_Multicriterio_A.pdf/3ba7a734-7562-6a92-97f4-37ac625afe50?t=1601895349844 (accessed on 22 April 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).