Abstract

In Japan, Chinese female white-collar workers have emerged as a rapidly growing social group. Unlike traditional female migrants, high-skilled women exhibit more autonomy and strategy in their interactions with mainstream society. Traditional immigrant theories do not apply to their patterns of social adaptation. The paper draws on qualitative research with 38 Chinese female white-collar workers working in Tokyo after graduating from Japanese colleges. It illustrates their performance and strategies in adapting to Japanese society and explores how their decision-making process is shaped. The findings show that they exhibit a selective adaptation: They self-identify as “permanent sojourners”—they are eclectic, but inclined to maintain a cultural cognition ordered around their homeland culture, and they have multiple contacts across ethnic groups and reserve cultural differences in social interactions. Furthermore, this mode of adaptation results from the interaction of three factors: individual rational choice, the mutual pressure of the in-group and the out-group, and the national policies and historical issues between China and Japan. This paper argues that the migration patterns of different migrant groups should be interpreted in light of the subjectivity of migrants, taking into account their initiative, human capital, gender, and ethnicity. This study enriches the study of international female migration and adds to the practical research on social adaptation patterns among immigrants.

1. Introduction

The feminization of international migration is a significant trend today [1,2]. Influenced by the global industrial structure, labour market conditions require highly skilled and qualified personnel for a knowledge-based society and sustainable economic development. Countries and multinational corporations try to attract and integrate global talent by improving the research and innovation environment [3]. In recent years, the number of skilled women migrants has increased yearly as women’s educational attainment has increased and women’s participation in the labour market has expanded [4]. Additionally, a women’s sense of agency in the migration process has grown [2].

Faced with a low birth rate and a rapidly ageing society, to fill the labour gap and meet the shortage of global human resources for Japanese companies, the Japanese government has expanded its immigration programme, relaxed the visa review process, and added categories of residency status to encourage international students to work in Japan [5,6]. Unlike earlier high-skilled immigrants, many international students educated in Japan enter the Japanese labour market directly after graduation [7,8,9,10]. China is the top source of international immigrants to Japan. Since the mid-to late 1980s, the number of Chinese students in Japan has continued to constitute the highest percentage of foreign students [11], and the number of Chinese women who studied at Japanese colleges and then obtained work in Japan is also increasing. Benefiting from their higher education in Japan, they have an advantage in language and social adaptation [12]. After graduation, they work in the same jobs as Japanese college graduates.

The migration of female white-collar takes place in the context of international migration motivation theories. First, the economic analysis of migration focuses on the motivation for migration behaviour from an economic perspective, emphasising that the uneven distribution of resources causes migration. Classical and neoclassical economic migration theories consider wage level and economic disparity to be the main reasons for migration [13,14]. However, the new economic migration theory suggests that migration motivation is not the increased income from the absolute income gap between the two places, but is more based on the comparison with reference groups in the migrant’s hometown. It views migration as a rational family decision, and households with below-average income are more likely to migrate [15,16]. Second, the historical–structural explanations explain international migration at a political and economic macrolevel, arguing that migration is a natural consequence of economic globalisation. Labour market segmentation theory explores the origins of migration, in terms of market structure, arguing that developed countries have formed a dual labour market with primary and secondary levels and that foreign immigrants complement the secondary labour market [17]. The world system theory’s main view is that the flow of capital, goods, information, and technology drives the movement of labour from the periphery to the core [18].

However, the above-mentioned motivations can hardly be used to fully explain the migration of female white-collar workers. Many young skilled migrants are attracted to Japanese culture, lifestyle, and occupational planning, even though, sometimes, they earn less than they would in their home countries [12]. On the other hand, many do not intend to stay in Japan for long, despite the lifetime employment and high benefits offered by Japanese companies, which provide social capital for their integration into Japanese society [10]. Many female white-collar workers retain their Chinese nationality, even though they are eligible for naturalization. Previous research on Chinese female migrants in Japan focused on traditional female migrants, such as labour migrants [19] and marriage migrants [20,21]. They are also often described as tied movers, primarily for joining their spouses and trying to stay for the status. Research on Chinese female white-collar workers in Japan has recently begun to increase. Nevertheless, these studies mainly focus on their skilled migrant status and career development as human capital [22,23]. The social interactions and adaptation of Chinese female white-collar workers in Japanese society have not been adequately studied.

Theoretical studies on the social adaptation of immigrants explain adaptation outcomes in various periods from multiple perspectives, including assimilation [24], multiculturalism [25], and segmented assimilation [26]. Assimilation theory provides an early theoretical framework for the social adaptation process of immigrants. Then, multiculturalism and segmented assimilation theory expanded traditional integration theory and revised immigrant integration goals, adaptation patterns, and outcomes. Taking into account the heterogeneity of ethnic minorities and the local socioeconomic backgrounds of the host countries, segmented assimilation argued that human capital and social capital, as well as public policies and the social attitudes of residents in the host countries, have essential effects on the process and outcome of integration [27].

Much empirical research on the social adaptation of immigrants revolves around the relationship between immigrants and mainstream society. The factors of immigrant adaptation can be divided into individual dimensions (language skills, immigration purposes, and cross-cultural understanding) and environmental dimensions (social support, social networks, and attitudes of acceptance in mainstream society) [28,29,30]. Studies have shown that immigrants with high levels of human capital, such as language skills and relevant labour experience, are positively related to their length of residence, and their skills improve their chances of economic success [31]. Additionally, psychological reasons, such as satisfaction, comfort, empathy in interactions with locals, and work efficiency, can impact the degree of adaptation of immigrants [32]. In addition, recent studies have increasingly emphasised the influence of social structures in the home and host countries, such as community services, family support, and public attitudes [33,34,35].

Theoretical studies on social adaptation lack a detailed study of minorities’ internal discrepancies, and many empirical studies confuse adaptation outcomes with influencing factors. In addition, most studies have focused on the adaptation patterns of life in mainstream society, with little attention given to immigrants’ cognitive, affective, and practical changes. It is necessary to explore social adaptation dynamically because the migration decision and the performance of social adaptation are not static. Furthermore, gender is often overlooked as the most natural of variables in the research of social adaptation. “The double disadvantage of being foreign-born and female” [36] makes their adaptation process more complex and challenging than that of immigrant men. Gender gaps still significantly exist in Japan [37], so it is necessary to consider gender in studying the social adaptation of Chinese female white-collar workers in Japan.

Accordingly, this study focuses on Chinese female white-collar workers in Tokyo and aims to examine the process and manifestations of their social adaptation to Japan. Based on an in-depth empirical study, starting with Chinese female white-collar workers’ articulations of their migration trajectories, this study attempts to investigate the following two research questions:

RQ1: What are their practices in adapting to Japanese society?

RQ2: How was their decision-making process shaped?

In the following sections, this paper presents the research framework of this paper, based on the concept definition, and describes the methods. It then seeks to illustrate how their performance of adaptation and adaptive strategies evolved in three dimensions: self-identity, cultural cognition, and social interaction. This social adaptation pattern results from the interaction between individual and structural factors. Next, the paper attempts to explore the particularities of this adaptation mode by comparing it with other migrant groups, from the perspective of subjectivity.

2. Data and Methodology

2.1. Concept Definition and Analytical Framework

Social adaptation has been understood as how individuals adjust their behavioural habits or attitudes to adapt to the social living environment [38]. Immigrants’ social adaptation “is not uniform as it has been used interchangeably with such concepts as social adjustment, acculturation, and assimilation” [39]. In this study, the social adaptation of immigrants may be defined as a process by which immigrants continue to socialise and adjust their behaviour patterns and psychological states to adjust to the new environment. Therefore, the social adaptation of immigrants emphasises the adjustability and changeability and focuses on the response of immigrant behaviour to the changing environment. Meanwhile, social adaptation is not a one-way process, as immigrant adaptations also cause changes in the social environment of the place they move into. Eventually, immigrants and locals coexist in the same cultural life. The concept of social adaptation of Chinese female white-collar workers in Japan studied in this paper is similarly broad, including the dynamic process of integration and the current state of integration.

Based on Giddens and Bourdieu’s view of space and field [40,41], the subject–practice explanations of postmodern social theory emphasise that migrants are not passive, but dynamic, social and political subjects, who are not trapped by structures, but creating something new with their practices every moment [28,42]. Migrants cross not only the national boundary, but multiple spatial fields simultaneously, including physical, social, and mental spaces [43], such as workplaces, residential communities, and public spaces in cities. This theory provides a new perspective for understanding female white-collar mobility, requiring a subjective view of female white-collar migration decisions. Specifically, from the perspective of subjectivities in migration, social adaptation is presented as a result of subjective construction, rather than as a natural or merely environmentally determined one. Based on the feelings and experiences of Chinese female white-collar workers, the study focuses more on their process of subjective construction.

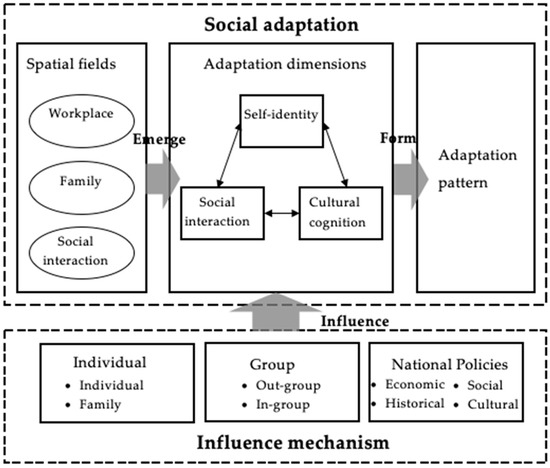

This study follows the research framework in Figure 1. Firstly, Chinese female white-collar workers in Japan move through the spatial fields of the workplace, family, and social interaction. Their daily interaction world is gradually formed in the three spatial fields, from which they generate their unique adaptation performance to Japanese society. Next, referring to the empirical research on social adaptation, their social adaptation performance is summarised in three dimensions, from the perspective of the immigrant subject: self-identity (psychological adaptation), cultural cognition (cognitive adaptation), and social interaction (behavioural adaptation). The two-way arrows between the three dimensions suggest that they influence each other and are interdependent, and there is no one-way progression or causal relationship. Meanwhile, their migration activities are influenced by individual, group, and national policies in different spatial fields and life stages. They present different adaptation performances in the three dimensions, which ultimately influence the formation of their social adaptation patterns.

Figure 1.

Analytical framework.

2.2. Data and Methods

Previous studies have established the effectiveness of qualitative research in migration studies [44,45,46]. The personal contact and perceptual understanding of migration are significant. A qualitative research method can capture the essence and reasons for different steps in the migration process, which cannot be measured through quantitative surveys. This study adopts qualitative research methods of in-depth interviews and participant observation.

The starting points for this fieldwork were five Chinese female white-collar workers at N Corporation, a traditional sizeable Japanese company with over 100,000 employees located in Tokyo. Through them, the researchers met more Chinese women working in Japan after graduating from Japanese colleges. Following snowballing sampling, thirty-eight Chinese female white-collar workers in Tokyo were approached (see Table 1). They were aged 25–44 and had studied and lived in Japan for more than five years.

Table 1.

Profile of participants (N = 38).

In the in-depth interviews, the researchers used biographical narrative interviews. Focusing on each life story, a dynamic “top-down” and “past-to-present” perspective can be used to interpret how “immigrant life” permeates their lives. For example, the researchers would start with the narrative question of “Why did you come to Japan to study?” or “The major choices you made during these years in Japan”. Most interviews occurred in cafes, restaurants, and the interviewees’ homes and lasted about two to three hours. By focusing on each individual life story and allowing the interviewees to tell their stories as they wish, avoiding the imposition of various pre-determined themes in the interviewees’ interpretation of migration behaviour, it is possible to see how they relate their understanding of migrant life in Japan to the overall life story.

The critical spots for participant observation included “joshikai” (ladies party), colleagues’ gatherings, and the activities of the Tokyo Career Girls’ Club. The researchers participated in several of these gatherings, listening to their conversations, asking questions, and joining in. The purpose of participant observation is to collect “naturally occurring descriptions” [47] of their activities. The critical incident technique is used to capture the dynamic changes in their emotions and behaviour. The topics of the meaning of work, life in Japan, and foreign identity in the above scenarios provided material for this study. In addition, participant observation of the women in daily interactions enabled an overall picture to emerge of their self-presentation in their everyday life, such as dressing, thinking style, and habits of treating others.

The researchers also rented a community room to conduct two focus group interviews on “Chinese cultural education of the second generation growing up in Japan” and “Relationships with Japanese neighbours and the impact on their lives in Japan.” Focus group interviews are complementary to the two main qualitative research methods, which can obtain representative and universal opinions to a certain extent. Group interviews are also more suitable for the common identity of “Chinese female white-collar workers”, as the participants have the same academic and work backgrounds. In addition, through official statistical data, the researchers sorted out information on the policies and systems for international students and foreigners in China and Japan.

Following ethical principles, the researchers obtained informed consent from all participants before conducting the fieldwork. In presenting the findings, the author used only pseudonyms and age in the analysis to protect respondents’ privacy. The author translated the citations from the participants in Mandarin Chinese into English. In addition, an internal expert familiar with the research offered comments on data analysis and translation process.

3. Findings

3.1. Selective Social Adaptation

3.1.1. Self-Identity: Permanent Sojourners

The Chinese female white-collar workers present as “permanent sojourners” in self-identity [48,49], on a spectrum between the sojourner and the settler. During their time abroad, they never stop thinking about the value and meaning of migratory actions. They constantly reconstruct their identity roles amid contradictions and conflicts.

In terms of long-term consciousness, female white-collar workers had a strong intention to return to China at the beginning of their studies in Japan. From the interview data, it was found that they studied in Japan for instrumental reasons, such as “gaining overseas experience”, “obtaining qualifications”, and “an alternative to studying in Europe and the United States”. There were also emotional reasons such as “yearning for Japanese culture” and “following a boyfriend”. However, after finding work, they changed their plans and elected to stay in Japan for a long time. On the other hand, they are also marked by “future orientation” [50]. Although they do not have a definite time set for their return to China, they have a vague sense of a potential future return and are not averse to going to other countries.

“What is this place for me?” “Do I want to stay here for the rest of my life?” I often ask myself these questions. I don’t have to hang in a tree like the Japanese. I think this kind of outsider mentality sometimes has its advantages. When problems crop up, you are not so torn. Japan is not my home field, after all. I will return to China when I am old, but maybe I don’t need to wait to be old. We will go back to China when our children go to college.(L.W.J., 32 years old)

As an ethnic minority, they have a fundamentally different social character from Japanese locals and do not reinvent themselves to be held to the same standards as the Japanese. For example, when they encounter frustration in the workplace, they often use their identity as “foreigners” to regulate themselves.

I’m a foreigner, so the company doesn’t ask me to do as much (as the Japanese do).(T.T., 32 years old)

I’m a foreigner, so I’m different. Alternatively, maybe the company recruited me to show off my personality and didn’t want me to be like the Japanese.(L.H.M., 29 years old)

In the workplace, if they are evaluated in the same way as the Japanese, they take it as a confirmation of their seriousness at work. Nevertheless, in their daily life, if they are said to be Japanese, it becomes a derogatory indication of an inflexible and indifferent mindset. Although they should follow the Japanese ways of handling things, when they meet with their Chinese friends in private, they will complain about the Japanese and Japanese society together. Phrases such as “You know Japanese ……” and “That is what Japanese are like ……” were often used in the interviews. When they encountered conflicts or contradictions, they inadvertently separated themselves from the Japanese.

3.1.2. Cultural Cognition: Eclectic but Inclined towards Chinese Culture

The social adaptation of Chinese female white-collar workers reflects a composite state of being in which they are “middle people” between two societies and cultures. Their cultural cognition is eclectic and demonstrates the maintenance and persistence of their own national culture. Interviewee M.M. described her experience and inner thoughts in the following way:

I went to China on a business trip with my Japanese manager. A Chinese state-owned enterprise manager said he would arrive at 10:00, but actually came at almost 11:00. The Japanese manager said, “I’m used to it. In China, when you say ‘start at 10:00′, 9:00 to 11:00 is considered 10:00”. I said to him, “Not all Chinese are like that. I’m never late”. He said, “That’s because you’ve been in Japan too long”. In Japan, whether it’s a meeting with a tutor or a client, you have to arrive five minutes early, and you can’t be too early lest you put pressure on people. But it’s impossible to be late. Perhaps he was right, and I developed the habit of keeping time in Japan.(M.M., 31 years old)

Chinese female white-collar workers learn and absorb Japanese customs and culture to adapt to Japanese society during their college life in Japan. They make themselves look more Japanese in their appearance (dress and makeup). Their habits, such as “not causing trouble to others” and “never being late but also not being too early to avoid stressing others”, manifest an acceptance and recognition of Japanese cultural norms. However, while they appreciate and absorb Japanese culture, they also dissent from it. In the workplace, some female white-collar workers are dissatisfied with the traditional Japanese corporate culture of the seniority wage system and lifetime employment, and they may take the initiative to negotiate promotion terms with their companies, jump ship to small and medium-sized enterprises, or quit their jobs to start their own businesses. Chinese female white-collar workers find it difficult to accept the “tanshin-funin” (solo assignment) culture that is unique to Japanese companies. In contrast to the majority of Japanese wives who choose to stay in their hometown with their children for 3–5 years, Chinese female white-collar workers will accept a reduction in salary to move to the same workplace with their husbands or even quit their jobs temporarily.

When asked, “Which is more important, the Japanese or Chinese Spring Festival?”, all interviewees agreed, “Both are celebrated, but the Chinese Spring festival is the real one”. Compared to their Japanese colleagues of the same age, most of the interviewees had children at an earlier age. They retained the traditional values of Chinese families in marriage and parenting. Regarding Chinese learning for their children born and growing up in Japan, all interviewees believe that “learning Chinese and traditional Chinese culture is significant”, including the women married to someone who is Japanese. In families with school-age children, the children are enrolled in Chinese language classes and actively involved in traditional cultural activities organised by the embassy and Chinese communities.

I regret that our children must first learn Japanese geography and history when they start school. The culture of China is thousands of years old and profound, and it is a pity that they do not have a Chinese cultural environment.(H.M.,33 years old)

Chinese families may maintain a diet that consists mainly of Chinese food in their choice of ingredients and cooking methods. Authentic Chinese restaurants and Chinese stores are places they frequently visit, which is radically different behaviour from the local people. They accept “Japanese common sense” partly to adapt to society. Nevertheless, they maintain an emotional identity with their homeland and retain a “Chinese style” in language, food, traditional festivals, and family values.

3.1.3. Social Interaction: Multiple Contacts across Ethnic Groups

Chinese female white-collar workers shuttle between their Chinese ethnic group and Japanese society. Because of their work, most of their colleagues and clients are Japanese, but their social support networks and circle of friends for leisure time are primarily Chinese.

You can talk about work, TV shows, food, and Chinese and Japanese culture with Japanese, but for relatively private content, like my relationship with my mother-in-law or a couple’s quarrel, I will talk with Chinese. Because of cultural differences, she may not understand what you mean. Additionally, although there are friends we have known for more than ten years, we always feel a sense of distance from them and they didn’t open their hearts to you either.(H.X., 41 years old)

From the view of the frequency and objects of interaction, the characteristics of their social network are closed and homogeneous. Most of their friends are Chinese, and there are fewer Japanese who can establish permanent and continuous contact. The Japanese friends they make are mainly based on connections from work or school, but they are not in frequent contact with each other. Only two interviewees said they “have Japanese friends and have kept in touch regularly for more than five years”. They are not very active in managing community affairs and participating in community activities. Some mothers join in community activities because of their children.

Chinese organisations in Japan are an important social group for female white-collar workers. There are largely three types of Chinese organisations they participate in: One category may be based on job nature or study experience, such as “The Chinese Students Association (of Japanese schools) or “Tokyo Career Girls”; a second category may be based on their origin in China, such as “Liaoning Province associations in Japan” and “Chambers of Commerce of Shanxi Province in Japan”; the third category is composed of recreational clubs that are based on hobbies. Female white-collar workers belong to one or more organisations and can meet more like-minded Chinese or those with similar life experiences. Diverse Chinese organisations provide emotional support and meet the needs of information sharing and recreation.

Social media expands immigrants’ social networks and communities [51]. It provides an essential exchange of information for immigrants’ cross-cultural adaptation and helps them maintain a stable cross-immigrant identity [52]. Every interviewee has more than two “Chinese WeChat groups”. The members of these groups are very active, and topics mostly cover daily life, such as “What should I wear for my child’s graduation ceremony?” The “Chinese WeChat group” is a crucial way to share information and help each other. It also supplies insights about being a mother in different cultures [53,54].

Female white-collar workers distinguish between Chinese and Japanese friends and differentiate what SNS they use and what content they talk about. They are more likely to bond with Japanese through LINE and Facebook, while reserving WeChat and Weibo for use with Chinese people. It is typical for the workers that “WeChat moments are updated more often than Facebook”. Those who are married to Japanese people use their Japanese names when interacting with their husband’s friends, but use their Chinese names on their own and on WeChat.

Chinese female white-collar workers have a strong sense of their overseas Chinese identity and show an “in-group orientation” [49]. They always discuss the political situation and current affairs in China with their compatriots and express their feelings of longing for the motherland. They feel angry when there are adverse reports about China in the media. When there is news about crimes committed by Chinese in Japan, they think that “the good impression we Chinese in Japan have accumulated is ruined”.

Chinese female white-collar workers live in middle-class neighbourhoods and do not live in ethnic enclaves. Compared to their Japanese neighbours, they have more frequent contact with their Chinese neighbours in the same building. Some of them have established small groups and WeChat groups of Chinese neighbours. They use the neighbourhood’s public space to hold activities during significant Chinese festivals and invite teachers to teach their children Chinese and martial arts. When they encounter intractable problems, they often turn to their Chinese friends, believing that Chinese people are more reliable and keeping them identified as the first contact person in case of emergency, a resource for when they cannot pick up their children, or the guarantor of application for permanent residence.

3.2. Formation and Maintenance of Social Adaptation

3.2.1. Individual Rational Choice

Immigration is an act of investment in human capital [13]. Formal education and on-the-job training are the two significant investments in human capital [55]. Regarding education level, all interviewees had a bachelor’s degree, 76% had a master’s degree or higher, and some held two or three master’s degrees (see Table 1). Regarding career development, they work in the same jobs as Japanese white-collar workers, such as sales (business to business), programmer, consultant, and marketers for large corporations. The jobs show strong professionalism, many opportunities for growth, and a deep international background. As for their ability to understand across cultures, they are more open-minded, due to years of overseas study and work experience, have a positive attitude towards the unknown, and are inclusive of new things.

The accumulation of human capital, such as language skills and labour experience, has increased their chances of economic success [12]. The income of interviewees is higher than the average income of a Japanese women [56], and the household income of married women is in the top 10% of Japanese families. All married women have purchased property, and some have investment income aside from wages, such as stocks, contracted parking lots, restaurant shares, and house rental income. Therefore, they have solid financial ability, going beyond their basic physiological needs.

Regarding visa types, there is a unique “One family, N status” phenomenon for most married female white-collar families. According to the requirements for naturalization, such as income level and years of work, the female white-collar workers interviewed met the criteria for Japanese citizenship, but of the 38 female white-collar workers (twenty-eight married), only four women married to Japanese nationals (out of nine in total) chose Japanese citizenship. The coexistence of Chinese and Japanese nationalities provides an additional option for families in the future. Eleven of the 19 Chinese families combined high-skilled professional status with permanent residency. One spouse with permanent resident status can live in Japan, even if they do not have a job. Similar to Japanese citizens, those with permanent residence also have a higher approval rate when the family buys a house, applies for a loan, or starts a company. The other spouse holding a high-skilled professional visa can apply for a long-term visa for their parents. Therefore, a high-skilled professional visa has more benefits than Japanese citizenship for Chinese working couples with young children to care for. “One family, N status” spreads the risk for the immigrant family’s overseas life, while maximising family benefits. Interviewee D.X.M is one of the types above, but their baby is a dual U.S. and Chinese citizen and has Japanese permanent residency:

My husband and I are both Chinese, I have a permanent residency visa and my husband has a highly-skilled professional visa. Considering the future education of our child, we gave birth in the United States and our baby is a dual U.S. and Chinese citizen and has a Japanese permanent residency now.(D.X.M., 34 years old)

3.2.2. Mutual Pressure of the In-Group and Out-Group

The evaluation and attitude held by others is a mirror reflecting oneself, and individuals know themselves through the “mirror” [57]. The bicultural collision between the home country and the host country generates the uniqueness and loneliness of female white-collar workers.

Alienation of the Out-Group

Human relations in Japanese society are based on the “place”, a coexistence field where ‘we’ and ‘others’ intermingle. The Japanese show great empathy within the place, but are unusually indifferent to people outside of the place [58]. The twelve interviewees who had changed jobs said they had “almost no contact with Japanese people in their previous companies”. A traditional sizeable Japanese company provided them with a stable life, self-confidence, and life satisfaction. Nevertheless, with the dissolution of the working relationship, the relationship between the female white-collar workers and their former colleagues also ended abruptly. It was hard to take for the female white-collar workers.

The Japanese who I worked together with for 8–10 h a day and had lunch with together before have never been in touch since I resigned, including some Japanese female colleagues who used to go to parties with me or go shopping together. I thought I was getting along with them more deeply, but it is not real.(Z.X.,29 years old)

The essence of interaction is a kind of communicative rationality mediated by language and mutual understanding [59]. When interacting with others, the Japanese extend an extreme form of sympathy in which they enter into the other’s heart and change their behaviour according to social expectations [60]. They hide their true feelings to avoid conflict and suppress any desire for further communication, even if it is mutual. In response to the question, “How do you feel about your relationship with Japanese?” the interviewees mentioned “polite” and “do not trouble others”. They also mentioned “a sense of distance”, “I don’t know what they think”, and “I’m too tired and have to be careful”. The contradictions strengthen their awareness of foreign status and prompt them to form a passive attitude. It is challenging to develop a deeply personal relationship between the two parties.

When we went shopping together, no matter what you showed her, she would say “kawaii” (cute), and no matter which dresses I chose, she just would describe the advantages. I felt bored after going out together several times.(L.X.S.,27 years old)

The attitudes of the members of the host country greatly influence the process and pattern of integration for the migrant [27]. The Japanese have the highest distrust towards foreigners among countries in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development [61]. The stereotypes formed by early Chinese immigrants overseas and the sense of superiority derived from Japan having once been the world’s second-largest economy have reinforced the foreigner consciousness of white-collar workers. It also constantly reminds them that they do not belong here. Interviewee X.L. shared a small detail from a chat with a Japanese mother:

Japanese mothers are always surprised by my education and job when I talk with them. Nevertheless, I am surrounded by such Chinese. This means that the Japanese don’t look up to us immigrants at all but still have a condescending attitude.(X.L., 36 years old)

Incomprehension of the In-Group

Every year when I go home to visit my relatives, I am asked how much I earn. A relative said acidly, “That is how much you make overseas? It’s not much more than our child in Beijing”. I was very uncomfortable. In Japan, people have a sense of boundaries, so they don’t ask that question, and even if they asked, they wouldn’t say that.(W.Z.Y.,34 years old)

5 or 6 years ago, I took a business trip from Japan to Taiyuan (China) with a Japanese manager. We took a taxi from the development zone to the airport when we left. When we arrived at the airport, the driver gestured at 80 yuan with his hand and took out an expired invoice. At that time, I said it was incorrect in Chinese, and the driver said, “So you are Chinese?” I gave him money at the actual price of the proper invoice, and he said, “So stingy even after coming from abroad”.(L.C.Q,33 years old)

Group attitudes and social networks in the home country also impact immigrant adaptation. Returning to China is a “temporary relief”, when they can see their long-awaited relatives and feel more relaxed. However, as the two interviewees mentioned above, female white-collar workers experience varying degrees of discriminatory treatment and misunderstanding when they visit their families or go on business trips. Going abroad means they are detached from their original living area and torn from their “acquaintance society”. The female white-collar workers had little contact with their friends in China, except during the traditional festivals, when they would send messages on WeChat. Over time, the “accumulative effect of immigration” [62] emerged, and they gradually adapted to life in Japan. However, they felt uncomfortable in the environment of the home country, and the hometown had become a “foreign land” to which they could not return and could not adapt.

3.2.3. National Policies and Historical Issues

Political factors have more influence on migration than wage differentials between countries [63], and the mobility of immigrants depends heavily on how their skills are evaluated and needed in different cultural, social, and political contexts [64]. As an ageing society with a low birth rate, Japan urgently needs foreign immigrants to alleviate the labour shortage. In July 2008, the cabinet officially proposed the “300,000 International Students Plan” and made it one of the national development strategies. The Japanese government, domestic universities, and the Immigration Bureau have been working together to implement policies to attract more international students to Japan. For them to stay and work in Japan after graduation, the Japanese government relaxed the visa period for international students looking for jobs and supported international students starting businesses after graduation.

The Japanese government has lowered the threshold for foreigners to obtain permanent residence status to ensure that global talent works longer in Japan. The “Japan Revitalization Strategy 2016” proposed the “fastest application system to permanent residency in the world” to reduce the time for foreign talent to obtain permanent residency [65]. In April 2017, the Ministry of Justice updated the “Guidelines for Foreigners to Obtain Permanent Residence Permits” and relaxed the scoring criteria. Foreigners with a score of 80 points or more (as stipulated in the “points calculation table” [66]) can obtain a permanent residence visa in as little as one year. As of 2021, there were 15,735 foreigners with a high-skilled professional visa, of which the Chinese are the most numerous, accounting for 65.5% [67].

As a part of the current Chinese overseas migration boom, immigration to Japan does not exist in isolation. Since the 1960s, China has entered a “new era of immigration” encouraged by restructured social policies for immigrants in North America and Australia, the reorganisation of Europe, and the reorientation of China’s foreign immigration policies. Since the reform period began, especially after the mid-1980s, there has been a boom in overseas study to accelerate education development and talent cultivation. In 1993, the Chinese government put forward the policy of “supporting study abroad, encouraging return to China, and freedom to come and go”, indicating an attitude of support for self-financed students. Elite study abroad gradually tended to become universal.

Unlike other destinations for Chinese immigrants, Japan, which is a close neighbour to China in Asia, has a complicated relationship. Significantly, the unresolved historical issues of the Second World War and territorial disputes have made Chinese people in Japan hold ambivalent attitudes towards Japan. As first-generation immigrants, female white-collar workers were born and raised in China. They harbour a strong sense of national identity and are passionate about defending the dignity of China. Most are psychologically resistant to “becoming a Japanese national” or “becoming Japanese”. They become angry when their children’s history textbooks in elementary school contain distorted explanations of the Sino-Japanese War. The following two quotes present their patriotic complex.

Not only do I not want to change (my nationality), but my parents also disagree. When I left China, my parents repeatedly instructed me “absolutely not to change nationality to Japan”.(H.M., 33 years old)

About the Sino-Japanese war, Japanese history textbooks are written to describe a process of “the enlightenment of civilisation from ignorance”. I told my son that aggression is the true motivation for the war no matter how it is embellished. When my children grow up, I will take them to the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall.(T.H.Y, 41 years old)

In addition, the structural factors are China’s growing economic power and international influence. After the Second World War, Japan entered a period of rapid economic growth, with a considerable income gap between China and Japan. Most of the previous generation of overseas Chinese went to Japan with the dream of getting on in life or even changing the fate of the whole family. Unlike previous generations, this generation went abroad when China’s economy was proliferating, and in 2010, China’s GDP surpassed Japan’s to become the second largest in the world. Along with China’s growing power, Chinese female white-collar workers are taking a wait-and-see attitude towards putting down roots in Japan.

4. Discussion

The linear narrative from immigration to permanent residency to citizenship and from alienation to assimilation does not fit Chinese female white-collar workers in Japan. Unlike the “desinicization” or “naturalisation” of earlier immigrants, female white-collar workers do not deliberately avoid Chinese identity. Their ultimate goal is not “Japanese nationality” or “long-time residence in Japan”. Female white-collar workers show distinctive characteristics of “heteroassimilation”. In contrast to other types of social adaptation, this specificity can be discussed in terms of the subjectivity of migrants.

First, the social adaptation of Chinese female white-collar workers is autonomous from the view of the initiative of the immigrant. The status change from international students to white-collar workers settling in Japan is a carefully considered step for personal development under the influence of the Japanese government’s immigration programme and the expansion of the overseas market demand by Japanese companies. They reconstruct their social capital according to their deep-seated personal needs and adjust their lifestyles and behavioural patterns to adapt to new environments. In their specific practice spaces, Chinese female white-collar workers use a dual and situational adaptation strategy that divides the inside and outside clearly. In the study of the “Korean community” in the United States, Kim proposed the “non-zero-sum model of assimilation” [68]. The migrants are not predicated on integrating into the host country’s culture, but rather on preserving their own culture. This also exists in Chinese white-collar workers in Japan. They are more neutral about Japanese cultural values than the locals. However, this does not mean a complete abandonment of Japanese culture. In the public sphere, they seek assimilation in language and appearance, while in the private sphere, they maintain traditional Chinese customs and ethical culture. Japanese and Chinese cultures are stitched together in a way where the boundaries are clearly defined. Female white-collar workers actively choose not to integrate fully and form segmented assimilation patterns and multicultural fusion. However, their integration is different from traditional segmented assimilation and multiculturalism, in terms of motivation. It is not a passive and helpless act resulting from pressure to survive, but a conscious and active choice to seek development opportunities by exercising their cognitive agency and internal drive. Based on the accumulation of social capital, Chinese female white-collar workers have developed a more stable self-evaluation of themselves, which gives them flexibility in adapting to Japanese society.

Second, high human capital is the foundation on which selective adaptation can be achieved. In previous studies on migration from developing to developed countries, adaptation patterns similar to selective adaptation are primarily found in second-generation migrants [27] or 1.5 generation migrants [69]. Selective adaptation requires migrants to have a solid economic background and the flexibility to cope with the environment, which is difficult for early first-generation transnational migrants to do quickly. Labour market segmentation theory emphasises the structural demand for foreign labour as a fundamental reason for transnational migration and considers migration a complement to the secondary labour market in developed countries. However, in this study, Chinese female white-collar workers enter the primary market in developed countries, taking jobs with high earnings, high security, and good working conditions. Different migrant groups enter the host country differently, and the host country also shows different attitudes and acceptance towards them. Unlike other labour immigrant or marriage immigrant women, the experience of studying abroad accumulates human capital, such as language and professional skills, for female white-collar workers, which provides a cushion of adaptation before entering the Japanese workplace. Work experience and labour income give them material and psychological rewards of self-affirmation and open up opportunities and channels for gradual upwards mobility. Based on the accumulation of human capital, cultural capital, and social capital, white-collar workers achieve upwards mobility in socioeconomic status. Segmentation assimilation theory suggests that immigrant groups with higher human capital should show adaptation outcomes that indicate a greater integration into mainstream society. However, in the case of female white-collar groups, human capital and social adaptation appear to be negatively correlated. The diversity of social resources and the flexible status of permanent residents and high-skilled professionals weaken the motivation and initiative of female white-collar workers to integrate into mainstream society. This shifted their social adaptation in Japan towards a conceptual model of a global society. Their study and work experience in Japan provides them with the capital to move again, and they do not need to choose only Japan and China and do not exclude the possibility of migrating to other countries.

Third, gender is an essential factor influencing the direction of migration and the degree of adaptation. The motivation for migration changes along with the shift in focus and needs at each life stage. Unmarried women have greater occupational mobility and more time and contentment in their leisure, but are less attached to Japanese society. On the other hand, married female white-collar workers have a higher degree of economic integration than unmarried women. Building a family allows women to be less isolated in a foreign country, but the gender roles of the wife and mother also increasingly bind them. Given the cost of living and the recent growth of the Chinese economy, Japanese salaries are not competitive [70]. This paper confirms Hof’s claim that monetary considerations alone do not attract foreign talent [71]. Compared to economic conditions, their children’s educational capital and social welfare become the decisive factors that motivate them to stay in Japan. Families with children have stronger ties to Japanese society in community participation and a sense of belonging. Children influence the mobility of immigrant families and weaken their sense of temporary residence. New economic theory, which emphasises the role of the family, is also evidenced in the migration decisions of female white-collar workers’ families. The degree of adaptation and the attitude towards migration among family members are not the same. The family connects the external structure with internal autonomy as a meso-level between the individual and society. The immigration strategy of “One family, N identities” is the trade-off for a multicultural family after weighing the overall benefits.

Fourth, ethnicity is a double-edged sword. Unlike traditional female migrants, most Chinese female white-collar workers work on cross-border-related work, due to their professional skills and foreign status. Their business and work patterns are inseparable from China. Cross-border mobility is normal for them, keeping them in close contact with China. Meanwhile, the diversity of Tokyo satisfies their emotional attachment: More than half of Chinese migrants to Japan are in Tokyo. The growing number of Chinese shops, restaurants, and communities reduces their sense of isolation as an ethnic minority and maintains their experience of their original cultural identity. Female white-collar workers live in a continuous space between China and Japan, and national borders do not fracture their attachment to their ethnicity. Furthermore, the years of studying and living in Japan have accumulated kinds of ethnic contacts. The Chinese circle in Japan can provide instrumental and emotional values for them, opening up a localised space of belonging and providing them with social capital to adapt to Japanese society. Significantly, not all migrant groups can provide this powerful ethnicity. On the other hand, as described in the findings section, due to historical issues and territorial disputes between China and Japan, female white-collar workers in Japan hold ambivalent attitudes towards Japan, compared to immigrants who migrated to other developed countries. This generation of young Chinese people who received a patriotic education in China has a strong sense of national identity and is resistant to changing their nationality. They also emphasise the sense of ethnic and national pride as Chinese people in the education of the next generation, which influences the adaptation behaviours of both generations.

5. Conclusions

Drawing on qualitative research with 38 Chinese female white-collar workers working in Tokyo after graduating from Japanese colleges, this paper has sought to explore the specificity of their social adaptation. In terms of adaptation patterns, their social adaptation is not a simple linear trajectory, showing uneven selective integration across the di-mensions of self-identity, cultural cognition, and social interaction, while featuring upward mobility and embedded coexistence with low adhesion. In terms of influential factors, unlike the migration motivation dominated by economic rationality in traditional migration, this selective adaptation is a strategic construction that fully uses subjectivity. In contrast to the modes of other migrants’ adaptation, this subjectivity is shaped by autonomy, dominant cultural group identity, gender, and ethnicity.

Theoretically, this study takes shape within the literature on the social adaptation theory of international migration. However, the traditional view of social adaptation is defined and approached in the context of integrating disadvantaged cultural peoples into strong cultural peoples, the movement from low-income to high-income, and migration flows to Western countries. Taking Chinese female white-collar workers in Tokyo as an example, this paper extends the study of female migration and goes beyond the traditional Euro-centric framing within the literature. It expands the “seg-mented assimilation” of integration theory and enriches the practical study of social adaptation models.

Empirically, it is situated within the context of increasing demand for global talent between countries. Most international migration studies have generalised their “oth-erness” from a national perspective. Amidst a growing trend of high-skilled female migrants, this study broadens the connotation of non-economic factors as drivers of female migration. It emphasises the construction of subjectivity of white-collar migrants. It also deepens the understanding of female migration, provides new perspectives on retaining high-skilled migrants, and will hopefully stimulate further discussion on the social adaptation of first-generation high-skilled female migrants and their families.

Social adaptation is a process of change. This paper’s concept of selective adaptation in Chinese female white-collar workers is exploratory and still has room for further research. In the follow-up study, a cross-sectional comparison with other Chinese immigrant groups who came to Japan in different periods and from different classes can be made to subdivide and further justify the manifestations and characteristics of selective adaptation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L.; methodology, J.L.; investigation, J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.; writing—review and editing, J.L. and S.C.; supervision, S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Research Project of the National Foundation of Social Science of China (Fund No.21&ZD 183), Community Governance and Post-relocation Support in Cross District Resettlement; Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Fund No. B210207025), Community Governance of Rural Reservoir Migrants in the Context of Rural Revitalization; Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Fund No. B220207041), Post-relocation Support for Migrants Relocated from Easily Accessible Areas under the Threshold of Common Wealth.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the participants for taking the time and sharing their stories with us.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Herrera, G. Gender and international migration: Contributions and cross-fertilizations. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2013, 39, 471–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kõu, A.; Bailey, A. “Some people expect women should always be dependent”: Indian women’s experiences as highly skilled migrants. Geoforum 2017, 85, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Ramis Ferrer, B.; Luis Martinez Lastra, J. Building University-Industry Co-Innovation Networks in Transnational Innovation Ecosystems: Towards a Transdisciplinary Approach of Integrating Social Sciences and Artificial Intelligence. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Migration (IOM). Harnessing Knowledge on the Migration of Highly Skilled Women. Available online: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/iom_oecd_gender.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Sekiguchi, T.; Froese, F.J.; Iguchi, C. International human resource management of Japanese multinational corporations: Challenges and future directions. Asian Bus. Manag. 2016, 15, 83–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oishi, N. Skilled or Unskilled?: The Reconfiguration of Migration Policies in Japan. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2021, 47, 2252–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, H.; Meyer-Ohle, H. Overcoming the ethnocentric firm? Foreign fresh university graduate employment in Japa-n as a new international human resource development method. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 30, 2525–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hof, H. “Worklife pathways” to Singapore and Japan: Gender and racial dynamics in Europeans’ mobility to Asia. Soc. Sci. Jpn. J. 2018, 21, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hof, H. The Eurostars go global: Young Europeans’ migration to Asia for distinction and alternative life paths. Mobilities 2019, 14, 923–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L. Labor Segmentation and the Outmigration Intention of Highly Skilled Foreign Workers: Evidence from Asian-Born Foreign Workers in Japan; Research Institute of Economy Trade and Industry: Tokyo, Japan, 2019; Available online: https://www.rieti.go.jp/jp/publications/dp/18e028.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Japan Student Services Organization. Survey on the Status of Foreign Students. 2022. Available online: https://www.studyinjapan.go.jp/ja/statistics/zaiseki/index.html (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Hof, H.; Tseng, Y.F. When “global talents” struggle to become local workers: The new face of skilled migration to corporate Japan. Asian Pac. Migr. J. 2020, 29, 511–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjaastad, L.A. The Costs and Returns of Human Migration. J. Political Econ. 1962, 70, 80–93. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1829105 (accessed on 31 October 2022). [CrossRef]

- Todaro, M.P. A Model of Labor Migration and Urban Unemployment in Less Developed Countries. Am. Econ. Rev. 1969, 59, 138–148. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, J.E. Differential migration, networks, information and risk. Migr. Hum. Cap. Dev. 1986, 4, 147–171. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, O.; Bloom, D.E. The new economics of labor migration. Am. Econ. Rev. 1985, 75, 173–178. [Google Scholar]

- Doeringer, P.B.; Piore, M.J. Internal Labor Markets and Manpower Analysis: With a New Introduction, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Portes, A.; Walton, J. Labor, Class, and the International System; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.H. Study on Family Strategies of Married Women Working in Japan under Gender Perspective. J. Youth Stud. 2015, 06, 82–90. [Google Scholar]

- Nomura, S. Chinese in Japan; Kodansha: Tokyo, Japan, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Saihan, J.N. International in the Global Immigration Era: Chinese Wives Setting in Rural Japan; Keiso-shobo: Tokyo, Japan, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, Y.F. Becoming global talent? Taiwanese white-collar migrants in Japan. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2021, 47, 2288–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu-Farrer, G. “I am the Only Woman in Suits”: Chinese Immigrants and Gendered Careers in corporate Japan. J. Asia-Pac. Stud. (Waseda Univ.) 2009, 13, 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Park, R.E. Race and Culture; The Free Press: Glencoe, IL, USA, 1950; p. 150. [Google Scholar]

- Glazer, N.; Moynihan, D.P. Beyond the Melting Pot: The Negroes, Puerto Ricans, Jews, Italians, and Irish of New York City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Portes, A.; Zhou, M. Gaining the upper hand: Economic mobility among immigrant and domestic minorities. Ethn. Racial. Stud. 1992, 15, 491–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, A.; Zhou, M. The New Second Generation: Segmented Assimilation and Its Variants. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 1993, 530, 74–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldlust, J.; Richmond, A.H. A multivariate model of immigrant adaptation. Int. Migr. Rev. 1974, 8, 193–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, A.V.; Pérez, M.V.; Bustos, C.; Hidalgo, J.P.; del Solar, J.I.V. Inclusion profile of theoretical frameworks on the study of sociocultural adaptation of international university students. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2019, 70, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. How to retain global talent? Economic and social integration of Chinese students in Finland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marger, M.N. Social and human capital in immigrant adaptation: The case of Canadian business immigrants. J. Socio. Econ. 2001, 30, 169–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, B.C. Coping, acculturation, and psychological adaptation among migrants: A theoretical and empirical review and synthesis of the literature. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2014, 2, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaren, L.M. Anti-immigrant prejudice in Europe: Contact, threat perception, and preferences for the exclusion of migrants. Soc. Forces 2003, 81, 909–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmann, J.P. The paradox of integration: Why do higher educated new immigrants perceive more discrimination in Germany? J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2019, 45, 1377–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, E.; Chiang, L.H.N.; Denton, N.A. Immigrant Adaptation in Multi-Ethnic Societies: Canada, Taiwan, and the United States; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 285–287. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, M. At a Disadvantage: The Occupational Attainments of Foreign Born Women in Canada. Int. Migr. Rev. 1984, 18, 1091–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Economic Forum. Global Gender Gap Report 2021. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2021.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Samadi, M.; Sohrabi, N. The mediating role of the social problem solving for family process, family content, and adjustment. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 217, 1185–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimbos, P.D. A comparison of the social adaptation of Dutch, Greek and Slovak immigrants in a Canadian community. Int. Migr. Rev. 1972, 6, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration; China Renmin University Press: Beijing, China, 2016; pp. 63–84. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Practical Reason: On the Theory of Action; Joint Publishing: Hong Kong, China, 2007; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.H. Index of assimilation for rural to urban migrants: A further analysis of the conceptual framework of assimilation theory. J. Popul. Econ. 2010, 2, 64–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre. The Production of Space; Blackwell: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Kõu, A.; Bailey, A. “Movement is a constant feature in my life”: Contextualising migration processes of highly skilled Indians. Geoforum 2014, 52, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigad, L.I.; Eisikovits, R.A. Migration, motherhood, marriage: Cross-cultural adaptation of North American immigrant mothers in Israel. Int. Migr. 2009, 47, 63–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, G.; Chou, E. Transnational familial strategies, social reproduction, and migration: Chinese immigrant women professionals in Canada. J. Fam. Stud. 2020, 26, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, R.M.; Fretz, R.I.; Shaw, L.L. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1995; p. 114. [Google Scholar]

- Uriely, N. Rhetorical ethnicity of permanent sojourners: The case of Israeli immigrants in the Chicago area. Int. Sociol. 1994, 9, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, P.C. The sojourner. Am. J. Sociol. 1952, 58, 34–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bonacich, E.A. Theory of Middleman Minorities. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1973, 38, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tian, H.; Chang, J. Chinese first, woman second: Social media and the cultural identity of female immigrants. Asian J. Women’s Stud. 2021, 27, 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khvorostianov, N.; Elias, N.; Nimrod, G. “Without it I am nothing”: The Internet in the lives of older immigrants. New Media Soc. 2011, 14, 583–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miconi, A. News from the Levant: A Qualitative Research on the Role of Social Media in Syrian Diaspora. Soc. Media Soc. 2020, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; de Haan, M.; Koops, W. Learning to be a mother: Comparing two groups of Chinese immigrants in the Netherlands. Asian Pac. Migr. J. 2019, 28, 220–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, T.W. Investment in human capital. Am. Econ. Rev. 1961, 51, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- National Tax Agency. Current Survey of Private Sector Salaries 2021. Available online: https://www.nta.go.jp/publication/statistics/kokuzeicho/minkan2020/pdf/000.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Cooley, C.H. On Self and Social Organization; Huaxia Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2015; pp. 335–340. [Google Scholar]

- Nakane, C. Personal Relations in a Vertical Society—A Theory Of Homogeneous Society; Kodansha: Tokyo, Japan, 1967; pp. 123–131. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. Nachmetaphysisches Denken; YINLIN PRESS: Nanjing, China, 2001; p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- Lebra, T.S. Japanese Patterns of Behavior; University Press of Hawaii: Honolulu, HI, USA, 1976; p. 38. [Google Scholar]

- Vogt, G. Multiculturalism and trust in Japan: Educational policies and schooling practices. Jpn. Forum. 2017, 29, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D.S.; Goldring, L.; Durand, J. Continuities in transnational migration: An analysis of nineteen Mexican communities. Am. J. Sociol. 1994, 99, 1492–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriescu, M. How Policies Select Immigrants: The Role of the Recognition of Foreign Qualifications. Migr. Lett. 2018, 15, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu-Farrer, G.; Yeoh, B.S.; Baas, M. Social construction of skill: An analytical approach toward the question of skill in cross-border labour mobilities. J. Ethn. Migr. 2021, 47, 2237–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Revitalization Strategy 2016. Available online: https://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/singi/keizaisaisei/pdf/zentaihombun_160602_en.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Immigration Services Agency of Japan. Points-Based Preferential Immigration Treatment for Highly-Skilled Foreign Professionals. Available online: https://www.isa.go.jp/common/uploads/pub-291_01.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Immigration Services Agency of Japan. Number of Highly-Skilled Foreign Professionals by Nationality and Region in 2022. Available online: https://www.moj.go.jp/isa/content/930003527.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Kim, K.C.; Hurh, W.M. Adhesive sociocultural adaptation of Korean immigrants in the US: An alternative strategy of minority adaptation. Int. Migr. Rev. 1984, 18, 188–216. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B. Becoming a Rooted Cosmopolitan? The Case Study of 1.5 Generation New Chinese Migrants in New Zealand. J. Chin. Overseas 2018, 14, 244–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays Specialist. The 2018 Hays Asia Salary Guide. Available online: https://www.hays.com.my/documents/276768/0/Hays+Asia+Salary+Guide+2018+EN.pdf/c6b0c692-c4eb-8647-9a2b-277c1ec1d175?t=1596561697142 (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Hof, H.B. Mobility as a Way of Life: European Millennials’ Labour Migration to Asian Global Cities. Ph.D. Thesis, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).