Abstract

The demand for coffee in the local and global markets has encouraged massive production at upstream and downstream levels. The socioeconomic impact of coffee production still presents an issue, primarily related to the social benefit and economic value added for farmers. This study aims to identify the social impact of the coffee industry in rural areas in three different coffee industry management systems. Many coffee industries exist in rural areas, with various management systems: farmer group organizations, middlemen, and smallholder private coffee production. This study performed the social organization life cycle assessment to identify the social impact of the coffee industry in rural areas according to the management systems. The results indicated that the coffee industry managed by farmers is superior in providing a positive social impact to four stakeholders: workers, the local community, society, and suppliers, as indicated by the highest social impact scores of 0.46 for the workers, 0.8 for the local community, 0.54 for society, and 0.615 for the suppliers. The private coffee industry provides the highest social impact to consumers (0.43), and the middlemen were very loyal to the shareholders, with a total social impact score of 0.544. According to this social sustainability index analysis, the coffee industry managed by the farmer group has the highest endpoint of social impact at 0.64, which is categorized as the “sustainable” status. Meanwhile, the coffee industry managed by private companies and middlemen is categorized as “neutral or sufficient”. The coffee industry should implement improvement strategies to increase their social impact to all stakeholders in their business supply chain.

1. Introduction

The increased coffee demand has promoted massive coffee production at upstream and downstream levels [1]. The intensive agricultural industry production substantially depletes the natural resources and causes environmental damage [2,3,4,5,6,7]. Therefore, sustainability issues related to environmental, energy, and social impacts should be addressed.

Many stakeholders are involved in the coffee supply chain, including farmers, farmer groups, the processing industry, distributors, middlemen, retailers, coffee cafés, and end users. The coffee cherry bean is commonly produced by three actors: smallholder coffee farmers, private companies, and the government. More than 94% of the coffee plantations are managed by smallholder coffee farmers [8], indicating that most of the coffee is supplied by smallholder coffee farmers. After harvesting, farmers commonly sell their product to: (1) a small–medium coffee industry actor that performs the post-harvest processing until the coffee is consumed by consumers, and/or (2) middlemen. In recent years, the development of the small–medium coffee industry in rural areas has increased. Through the coffee industry in rural areas, the coffee farmer has other alternatives to whom they could sell their product besides the middlemen. Therefore, the establishment of a small–medium coffee industry in rural areas is predicted to generate an impact on the coffee farmers from a socioeconomic perspective.

Coffee sustainability studies have recently been conducted in many sectors and regions, including Indonesia. Many studies related to sustainability evaluation in coffee were reported, such as a comprehensive sustainability evaluation of coffee production considering the environmental, energy, and economic impacts at the farm level according to fertilizer application in Indonesia [9]. Globally, studies related to the impact of coffee production on sustainability were also performed in other countries [1,10], such as Brazil, where the environmental impact of green coffee production was identified [11]. A study in Japan investigated the carbon footprint of coffee production [12], while another study determined the environmental impact of coffee production in India [13]. An investigation of greenhouse gas emissions in coffee grown according to the cropping system in Columbia was performed [14], as well as a sustainability assessment of organic coffee in Mexico [15]. The study of coffee production, which focuses on the social and socioeconomic impacts, still needs to be expanded, both globally and locally in Indonesia. A study concerning the social implications of the biorefinery of coffee cut steam was conducted [16]; however, studies have yet to be reported regarding the specific social impact assessment of coffee production considering the management system.

The social impact is essential to determine to capture the existing social benefits for stakeholders involved in the system activities. Social life cycle assessment (S-LCA) is an approach to determine the social impact of the product, process, method, and organization. Through S-LCA, we can identify, communicate, and report the social impacts, sustainability knowledge, and social conditions of the product, process, method, and organization [17,18]. Unlike the environmental and economic LCA, the S-LCA is still at the pioneering stage. One recent development for the social impact assessment guidelines was the publication of the UNEP/SETAC “Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Products” [17]. This procedure still faces challenges in its methodology for performing S-LCA, specifically based on the definition and its functional unit use, the data limitations, and the aggregation of social aspects from the subcategory to impact category level. There is still no consensus for the standard to determine the indicators of social impact characterization. A study of social impact approaches has been proposed, such as by labeling the process with attributes using the rating scale of company performance and the impact to stakeholders [19]. In recent years, some studies proposed the use of the S-LCA methodology according to the typical object and subject observed condition to complete the existing S-LCA method, such as identifying the categories and subcategories of social indicators using a weighting factor [20]. Further, PSILCA was also developed as a new social impact life cycle assessment database [21].

The current research on social impact assessment tends to identify the social impacts of the product, process, and organization. For the product and process, S-LCA is commonly used during the social evaluation. To discover the social impact of an organization, the social organizational life cycle assessment (SO-LCA) is performed. SO-LCA and S-LCA have many methodological similarities, although they differ in the scope of the analysis [22]. The scope of the product and process involves all processes until the product is produced. However, the scope of the organizational social impact involves the whole organization. Many studies have been performed on the social impacts of the product and process, such as the product and process in agriculture production [19,23,24,25,26], in the battery [27], construction [20,28], plastics [29], and wastewater treatment industries [30], and in urban farming [31]. However, the S-LCA evaluation in coffee production in Indonesia does not yet exist based on the product, process, and organizational perspectives. The assessment of the social impacts of the product and process can be used to identify, learn, set up strategies and action plans, and inform management policies and practices. Furthermore, from a more complex organizational perspective, the SO-LCA can provide the essential information to improve the organization’s management system [16]. The social hotspot will be determined after a social impact evaluation is conducted. The status of their impact to stakeholders will be identified. Therefore, the organization will know their position and contribution to the actors involved in their supply chain. Specifically, the organization will know what aspect still needs to be improved according to the impact indicator status. Therefore, it is important to evaluate the social impact of coffee production according to the existence of the coffee industry in rural areas since there is no literature available on social aspect evaluation.

Regarding the sustainability evaluation of coffee production in Indonesia, some issues still need to be determined through intensive study in this area: Does the coffee production from the upstream to the downstream level beneficially affect the society and stakeholders in the coffee supply chain? In what aspect do they provide the most impact to the coffee farmer? What parts still need to be improved? Which coffee production management is more beneficial to support rural area development? These issues can be addressed by a comprehensive social and socioeconomic impact evaluation at the first important stage. However, no study evaluates the social impact in this field. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the social impact of the small–medium coffee industry in rural areas on all stakeholders involved in the coffee production supply chain. The SO-LCA was chosen as the comprehensive social impact evaluation in this study due to the comprehensive stakeholder evaluation, including the society, local community, consumers, authorities (government), and all stakeholders in the coffee supply chain (workers, suppliers, production actors, distributors, retailers, and investors). The latest version of the S-LCA guidelines provided by UNEP/SETAC 2020 [32] combined with the latest studies on S-LCA [20,29,33] were used in this study.

The study results would be beneficial information for further improvement according to intervention in coffee management to optimize the social benefits. For the coffee industry, the S-LCA results can be considered to redesign its organization management and redevelop the cooperation model with coffee supply chain actors: farmers as suppliers and investors, society, the local community, consumers, and the government, to increase the socioeconomic benefits. A further impact of the S-LCA results is that they can be used for decisionmakers (government) during planning and rearranging of the strategies to support the coffee stakeholders, specifically coffee farmers, coffee farmer groups, and the small–medium coffee industry in rural areas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Location

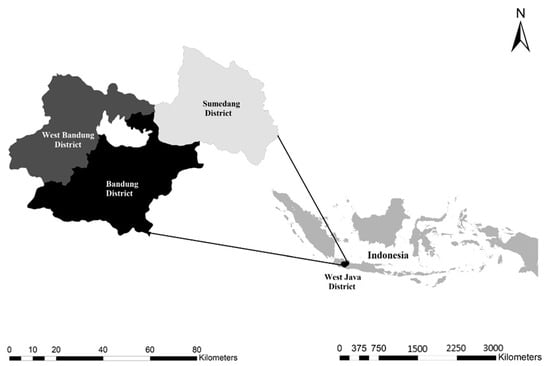

The study is located in West Java province, Indonesia, specifically in three regions: Bandung Regency, Sumedang Regency, and West Bandung Regency. The specific research site location is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research site location.

This area was chosen as it is the center of coffee production in West Java, specifically in Bandung District. About 16 small and medium coffee industries were involved in this study. There are no specific data regarding the total number of small–medium coffee processing industries provided by Indonesian statistics in this area. However, according to the data from the Bandung Statistic Agency, about 38 beverage industry SMEs exist (Bandung Statistic Agency). Therefore, this study involved approximately 42% of the total beverage industry in Bandung District.

2.2. Methodology

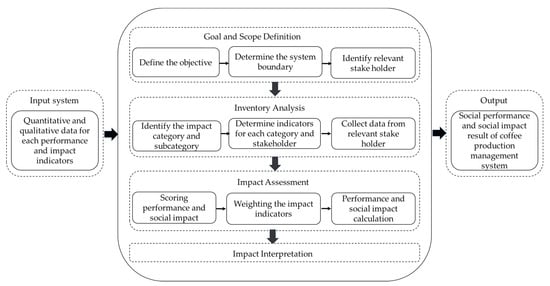

The study adopted the latest social life cycle assessment (S-LCA) framework for social impact evaluation, which follows the ISO standardized environmental LCA [33]. The UNEP/SETAC recommend that an environmental LCA framework can be used to determine the S-LCA. The S-LCA study was performed in four stages, as presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Social life cycle assessment procedure.

2.2.1. Goal and Scope Definition

Defining a clear goal and scope is the first critical stage in the LCA framework [34,35,36,37]. There are multiple preferences of research when defining the scope for S-LCA. Some researchers follow the ELCA framework that focuses on product development, while others prefer to use the companies or business organizations as the main component of S-LCA [30].

This study uses the business organization perspective that focuses on the coffee processing industry, including the entire life cycle and all stakeholders in its supply chain. The goal of this S-LCA was:

- (1)

- To determine the social impact of the coffee industry in rural areas according to its management system: (1) private companies, (2) coffee farmer groups, and (3) middlemen.

- (2)

- To determine the management option that is socially more beneficial for coffee stakeholders.

This study will identify the social impact of the coffee industry in rural areas according to its management system. There are three different management systems of the coffee industry: the private sector, farmer groups, and middlemen. The three coffee industry management systems are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the three coffee industry management systems.

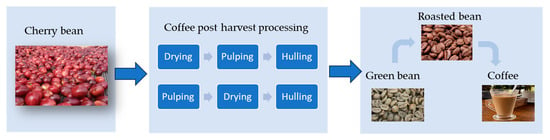

The system boundary of this study is the business organization of coffee production. Generally, the coffee industry conducts some production activity, as expressed in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

System boundary.

2.2.2. Data Inventory

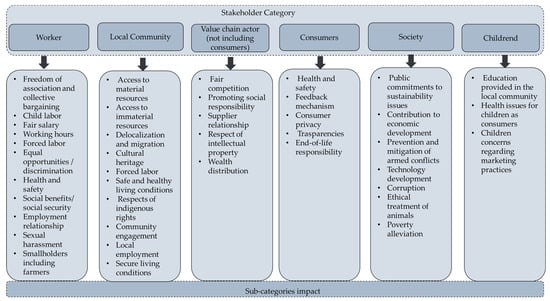

The social life cycle inventory assesses a company’s and its stakeholders’ relationship [19]. This study performed the S-LCA evaluation of the coffee industry in rural areas and assessed its impact on the stakeholders (farmers, farmer groups, the local community, authorities). The stakeholder category, the impact subcategories, and the performance and impact indicators were identified at this stage. The stakeholder category and the impact subcategories adapted the latest version provided by the UNEP S-LCA guidelines [32,33].

This study involved six main stakeholders, as follows:

- (1)

- Workers/employees

- (2)

- Local community

- (3)

- Society

- (4)

- Consumers (all consumers who are part of each supply chain)

- (5)

- Value chain actors (farmers as the main suppliers and shareholders)

- (6)

- Children (the additional stakeholders in the new SETAC/UNEP guidelines)

In terms of subcategories, this study followed the new guidelines for the social life cycle assessment of product and organization 2020, provided by UNEP [32] (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Stakeholder category and impact subcategories.

In terms of the performance and impact indicators, this study considered the indicators from some previous social life cycle assessment studies, considering the stipulation of labor in Indonesia and ILO best practices, and considering the discussion with relevant stakeholders and experts regarding the suitable performance and impact indicators of coffee production. Since there is no international consensus on a characterization method for social impact [38], some previous studies also involved the related stakeholders during the characterization of performance and the impact indicators’ references. Details of the social impact indicators and performance in this study are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Social impact and performance indicators’ references.

During the data collection, 16 small–medium coffee industries in rural areas were evaluated. According to [17], the backbone of the S-LCA is the information and data describing the product life cycle, the process involved, and the relation of stakeholders to the goal scope definition of the study. Therefore, the inventory data, the categories, subcategories, and indicators for social impact evaluation were investigated by following Table 2. The questionnaire was designed for agriculture production, more specifically, to be administered to small and medium coffee industry owners, workers, farmers as suppliers, coffee investors, local communities, and society in rural areas. The questionnaires were filled out on-site, face-to-face, with in-depth interviews with all stakeholder categories in this study.

2.2.3. Social Life Cycle Impact Assessment Method

After the data were collected by field observation and in-depth interviews, the next stage of S-LCA was to determine the performance and social impact of coffee production in rural areas. This study used the scoring system following the combination method proposed by UNEP and some previous studies [20,29,32]. Some studies have also used different leveling techniques, using 1–5 levels with different scales [39]. This study proposed a Likert scaling approach for scoring and prioritizing the indicators (Table 3).

Table 3.

Scoring scale of indicators for qualitative data.

For the qualitative data, the respondents provided the score directly using a Likert scale (Table 3). Meanwhile, this study used the scoring technique for the quantitative and semi-qualitative data by following Table 4. The scoring process involved all coffee stakeholders. The evaluation involved the coffee industry owners providing the score for the industry’s social performance assessment. Meanwhile, the scoring for the social impact assessment involved all coffee stakeholders, such as coffee farmers as suppliers, the local community, consumers, and workers. In this stage, the output is the performance and impact score. According to [32], conducting the weighting procedures during the social impact assessment will provide a more realistic result. Therefore, this study also weighed all elements in all sub-indicators by involving the experts.

Table 4.

Scoring scale of indicators for quantitative and semi-qualitative data.

After the score and weight level were obtained, the endpoint score for the social impact assessment was calculated by Equations (1)–(3) proposed by UNEP through the latest social impact assessment guideline. This study used the endpoint category following [20] (Table 5).

Table 5.

Endpoint category.

To calculate the net score of each subcategory, Equation (1) was used:

where:

- = net score of subcategory “x”

- = indicator “i”

- = number of indicators of subcategory “x”

- = coefficient of indicator “i”

The normalized net score for each endpoint indicator was calculated by using Equation (2):

where:

- = net score of endpoint category “x”

- = subcategory

- = sum of the total score of all subcategories “x”

- = sum of the total coefficient of endpoint indicator “x”

This study also calculated the score of the social sustainability index by using Equation (3):

where:

- = net score of endpoint category “x”

- = endpoint category (score 0–1, following Table 2)

- = sum of the total score of all subcategories “x” (using 1 for all categories)

Lastly, the endpoint score was converted into the social sustainability status (Table 6).

Table 6.

The grading of the social sustainability status.

3. Results

The social performance and social impact of the coffee industry in the rural area according to the management system were compared. This section provides a comparative analysis of each indicator, subcategory, and endpoint impact of the coffee industry management system.

3.1. Social Performance of Coffee Industry with Different Management Systems

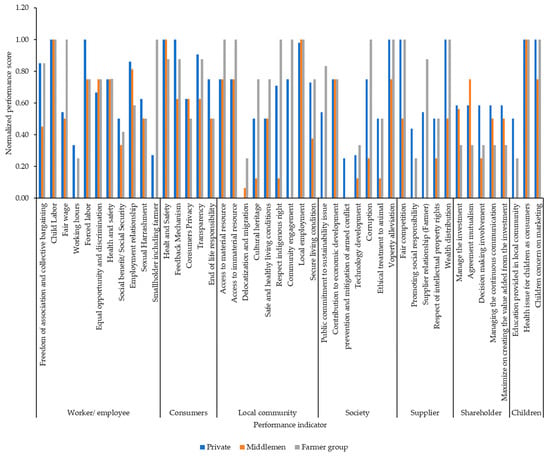

The social performance of the small–medium coffee industry was identified. According to the comparative study of the social performance indicators of three coffee industry management systems, some points were highlighted according to the study results, as presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Social performance of the three coffee industry management systems.

In the worker category, the coffee industry managed by the private coffee industry had the highest social activity compared to the others. The superior performance is shown in various indicators, such as in freedom of association and collective bargaining, working hours, forced labor, social benefit, employment relationship, and sexual harassment, with social performance scores of 0.85, 0.33, 1.00, 0.50, 0.86, and 0.63, respectively. This result indicates that the private coffee industry paid attention to employees’ social aspects while also managing the business organization in many aspects: working regulation, employees’ social benefits, and security. However, the coffee industry managed by the farmer group also showed the highest social performance scores in four aspects: 0.85 in freedom of association and collective bargaining, 1.00 in fair wages, 0.75 in equal opportunity and discrimination, and 1.00 in smallholders, including the farmers. Fair wages and involving farmers as workers showed the most significant performance in the coffee farmer group. According to this result, the farmer group is concerned with involving the coffee farmer not only as a supplier but also as a worker. This study is relevant because in the coffee industry managed by farmer groups, coffee farmers organized all business organization activity from the upstream to the downstream level.

Middlemen demonstrated the lowest social performance in the coffee industry. In the coffee supply chain, the middlemen play an essential role in the coffee industry’s history. Before the private smallholder coffee industries massively developed in rural areas, middlemen became the main actors in supplying and distributing coffee to local and global markets. This study indicates that middlemen had a lower performance in terms of fair wages, working hours, social benefits, security, and involving farmers as a worker. Therefore, the middlemen should evaluate their regulations and consider the workers as a vital actor to their business organization.

For consumers, the coffee industry organized by private and farmer groups had a better performance in almost all aspects. This study result is realistic when compared to the conditions in the field, where these two industries are commonly producing all derivative coffee products and managing the selling management system by themselves. Therefore, they consider the consumer aspect while managing their business organization. However, middlemen demonstrated a lower performance, as indicated by the lower performance scores in all aspects. The characteristic of middlemen is that they are seen as collectors and distributors. They do not manage the selling of products to the end consumers. This might be why they do not include a lot of consumer considerations during the organization of their business.

Regarding the coffee industry’s performance for the local community and society, the farmer group had the highest performance, which involves coffee farmers as the leading actors in managing their business organization: as workers, suppliers, and business team management. Inversely, the middlemen had the lowest performance. For the supplier category, the middlemen also had the lowest performance, while the others demonstrated higher performances. However, middlemen and private companies achieved a higher performance with shareholders since some of them have a good relationship with the investors. Meanwhile, the lower performance in the farmer group indicates that they are limited in connecting with the investors. Since the farmer group is managed with organization ownership, managing a good business organization is still challenging. Detailed results are presented in Table A1.

3.2. Social Impact of Coffee Industry with Different Management Systems

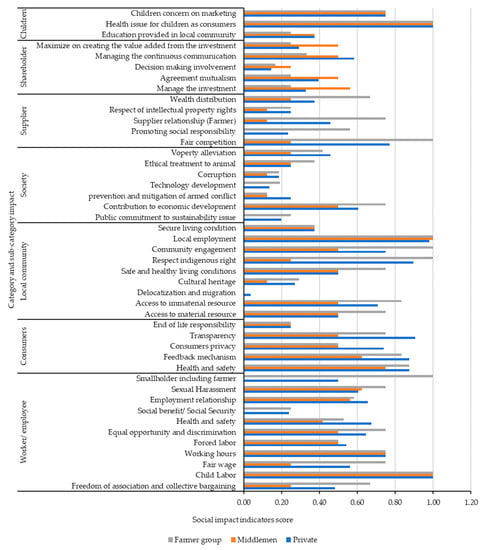

- Comparative Impact Per Impact Subcategory

Besides evaluating the social performance of the coffee industry from the business organization’s side, this study also assessed the social impact of their performance on all coffee stakeholders. According to Figure 6, the farmer group had the highest social impact in five impact indicators for the workers category, such as freedom association (0.67), fair wages (0.75), equal opportunity and discrimination (0.75), sexual harassment (0.75), and smallholders, including farmers (1.00). The highest social impact score was shown by involving the farmers as workers. This result indicates that farmers experience social benefits from their involvement as workers in the coffee industry.

Figure 6.

Comparative social impacts of the social impact indicators.

From the consumer’s perspective, the private coffee industry is more beneficial for customers related to the product and services. In fact, the coffee industry, which is managed by the private sector, has many derivative businesses and distribution facilities until the product is received by consumers, from direct selling, managing coffee at cafés, and connection with retailers. The increasing competition in derivative businesses driven by private coffee industries encourages managers to provide consumers with the best service and products. Therefore, consumers feel the social benefits of the coffee industry’s existence in all social impact indicators: health and safety products (0.88), a feedback mechanism (0.88), consumer privacy (0.74), and transparency (0.91). The farmer group also had a good impact on consumers. Even though the social impact score was lower than that of private companies, the impact was still higher than that of the middlemen.

The coffee industry managed by the farmer group is outstanding in providing a positive impact on the local community and society in terms of job creation, community engagement, and access to local material and immaterial resources. Therefore, to develop a more beneficial impact to the development of rural society, the coffee industry managed by farmer groups should be practiced more broadly. The detailed impacts for each sub-indicator are presented in Figure 6 and Table A2.

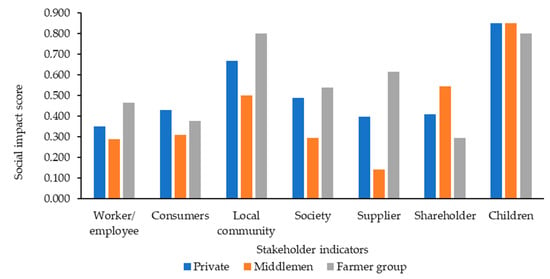

- Comparison of the Social Impact of the Endpoint Categories

This study also performed the calculation of the social impact per stakeholder category impact by using Equation (2). Detailed results are presented in Figure 7 and Table A3.

Figure 7.

Comparison of social impacts for each stakeholder indicator.

According to Figure 7, the coffee industry managed by the farmer group is superior in providing the social impact to four stakeholders: workers, the local community, society, and suppliers, as indicated by the highest social impact scores of 0.46 for the workers, 0.8 for the local community, 0.54 for society, and 0.615 for the suppliers. Meanwhile, the private coffee industry provided the highest impact to consumers (0.43), and the middlemen were very loyal to the shareholders, with a total social impact score of 0.544. Through the category impact evaluation, the actual situation of the level of social impact of the coffee industry with different management systems was captured. It also provided an overview of what aspects need to be addressed.

4. Discussion

4.1. Social Impact Hotspots of the Three Coffee Management Systems

The social hotspot needs to be identified to provide a consideration for future improvement. The hotspot was obtained by defining the status of the social impact score following the scoring system provided in Table 2. Each of the colors indicates the social impact status. Table 7 presents the social impact status for each indicator.

Table 7.

Social hotspot identification of the three coffee industry management systems.

The hotspot identification can provide the direction for improvement, and which aspect still needs improvement will be displayed in this analysis [32]. The social hotspot is indicated with the subcategories colored by orange and red. A previous study in a different study field also proposed this system [20].

The results of this study identified that private companies have one subcategory with a red color status in the local community, which is related to delocalization and migration. Furthermore, the private coffee industry also had 16 orange subcategories spread across all categories: 1 aspect in workers (social benefit and social security), 1 aspect in consumers (end of product life responsibility), 2 aspects in the local community (cultural heritage and secure living conditions), 5 aspects in society (public commitment to sustainability issues, prevention and mitigation of armed conflict, technology development, corruption, and ethical treatment of animals), 3 aspects in suppliers (promoting social responsibility, respect of intellectual property rights, and wealth distribution), 3 aspects in shareholders (manage the investment, decision-making involvement, and maximize on creating the value added), and 1 aspect in children (education provided in the local community). However, the private coffee industry generated a positive impact in five subcategories, as shown by the green color status.

The highest positive social impact was provided by the coffee industry managed by farmer groups, as indicated by the highest score of subcategories colored with the green status. About seven subcategories had a high positive impact on child labor and smallholders including farmers in the worker category, local employment, respect for indigenous rights, and community engagement in the society category, fair competition in the supplier category, and health issues for children as consumers. According to this study result, the coffee industry managed by the farmer group has a significant contribution to the local community and society.

However, the lowest positive impact, as well as the highest negative impact, were provided by middlemen. The positive impact was only shown in three subcategories: child labor, local employment, and health issues for children. Meanwhile, the negative impact was indicated in 10 subcategories, colored red, namely: social benefit and smallholders including farmers in the worker category, delocalization and migration and cultural heritage in the local community category, public commitment to sustainability issues, prevention and mitigation of armed conflict, technological development, and corruption in the society category, and promoting social responsibility and supplier relationships (farmers) in the supplier category.

Through these social hotspot results, this study shows which aspects should be improved by the private coffee industry, middlemen, and farmer groups to achieve positive impacts to the coffee stakeholders in their business supply chains.

4.2. Social Sustainability Index of Coffee Industry Management Systems

The current study on the social sustainability status still needs to be completed. Some studies proposed a method to identify the social sustainability status by indexing their social impact. This study follows [20] by using Equation (3). The social sustainability status is presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Social sustainability status of the three coffee industry management systems.

According to this social sustainability index analysis, the coffee industry managed by the farmer group has the highest endpoint of social impact at 0.64, which is categorized as the “sustainable” status. Meanwhile, the coffee industry driven by the private companies and middlemen is classified as “neutral or sufficient”. The coffee industry actors should conduct improvement strategies to increase their social impact to all stakeholders in their business supply chains.

5. Conclusions

There are some points to highlight related to the social impacts of the three different coffee industry management systems in rural areas: (1) The existence of the coffee processing industry in rural areas generated the most positive impact to the local community, specifically in the impact on the local employment in all types of management systems. (2) The coffee processing industry managed by the farmer group provided the most significant positive impact on the seven subcategories. Furthermore, the coffee industry managed by farmers was superior in providing a positive social impact to four stakeholders: workers, the local community, society, and suppliers, as indicated by the highest social impact scores of 0.46 for the workers, 0.8 for the local community, 0.54 for society, and 0.615 for the suppliers. Meanwhile, the private coffee industry had the highest impact on consumers (0.43), and the middlemen were very loyal to the shareholders, with a total social impact score of 0.544. The coffee industry managed by farmer groups still has a weakness in creating the customer’s social impact. Therefore, this study finding recommends that the farmer organizations increase their performance and consider customers’ preferences while managing their business organization. (3) Middlemen generated the lowest positive impact as well as the highest negative impact. Conversely, middlemen generated a higher positive impact to shareholders compared to other coffee industry management systems. This indicates that middlemen managed a good relationship with shareholders. (4) The coffee industry managed by the farmer groups had the highest endpoint of social impact at 0.64, which is categorized as the “sustainable” status. Meanwhile, the coffee industry managed by private companies and middlemen is classified as “neutral or sufficient”. The coffee industry should conduct improvement strategies to increase the social impact to all stakeholders in their business supply chains.

This study’s findings provide scientific information regarding the existing social impacts of the coffee industry in rural areas. Capturing the three different coffee management systems will provide a comprehensive social impact evaluation of what management system is more beneficial for farmers and society. Therefore, this study can recommend to governments what management system should be supported to be implemented more broadly in rural areas. For example, the government’s provision regarding developing the coffee industry in rural areas should prioritize the coffee industry managed by farmer groups compared to others. Currently, the assistance and support from the government have yet to reach the coffee industry driven by farmer groups. This study’s findings showed that a coffee industry managed by farmer groups has a more positive impact on local community development in rural areas. Therefore, this study recommends the government pay more attention and prioritize the assistance and support to the coffee industry managed by farmer groups.

In the future, the social impact evaluation in agriculture production needs a standard assessment model involving all agriculture production actors, specifically during the characterization of impact indicators for agriculture production, the weighting and prioritizing of indicators, and the standard of scoring. Since there is no specific standard for a specific sector, the social impact assessment methodology is still in progress.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M.R. and R.N.; methodology, D.M.R., D.P., I.A. and R.N.; data collection, D.M.R. and F.F.; validation, D.M.R., I.A. and R.P; formal analysis, D.M.R., F.F. and R.P; investigation, D.M.R.; resources, D.M.R. and F.F.; data curation, D.M.R.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M.R.; writing—review and editing, D.M.R., F.F., D.P., I.A, R.P. and R.N; visualization, D.M.R., F.F., D.P. and I.A.; supervision, R.N.; project administration, D.M.R.; funding acquisition, D.M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received research funding from the Internal Padjadjaran University Research Grant under the scheme “Riset Kompetensi Dosen Unpad (RKDU)” No. 1549/UN6.3.1/PT.00/2023, and the APC for research publication was funded by the Directorate of Research and Community Engagement, Universitas Padjadjaran.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data are available but could not be published. The raw data can be requested directly from the author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Directorate of Research and Community Engagement, Universitas Padjadjaran, Indonesia, who provided the research grant and APC funding for this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Social performance scores of the three coffee industry management systems.

Table A1.

Social performance scores of the three coffee industry management systems.

| Stakeholder | Sub-Indicators | Private | Middlemen | Farmer Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workers/employees | Freedom of association and collective bargaining | 0.85 | 0.45 | 0.85 |

| Child labor | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Fair wages | 0.54 | 0.50 | 1.00 | |

| Working hours | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.25 | |

| Forced labor | 1.00 | 0.75 | 0.75 | |

| Equal opportunity and discrimination | 0.67 | 0.75 | 0.75 | |

| Health and safety | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | |

| Social benefit/social security | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.42 | |

| Employment relationship | 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.58 | |

| Sexual harassment | 0.63 | 0.50 | 0.50 | |

| Smallholders, including farmers | 0.27 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Consumers | Health and safety | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.88 |

| Feedback mechanism | 1.00 | 0.63 | 0.88 | |

| Consumer privacy | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.50 | |

| Transparency | 0.91 | 0.63 | 0.88 | |

| End of product life responsibility | 0.75 | 0.50 | 0.50 | |

| Local community | Access to material resources | 0.75 | 0.75 | 1.00 |

| Access to immaterial resources | 0.75 | 0.75 | 1.00 | |

| Delocalization and migration | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.25 | |

| Cultural heritage | 0.50 | 0.13 | 0.75 | |

| Safe and healthy living conditions | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.75 | |

| Respect indigenous rights | 0.71 | 0.13 | 1.00 | |

| Community engagement | 0.75 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Local employment | 0.98 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Secure living conditions | 0.73 | 0.38 | 0.75 | |

| Society | Public commitment to sustainability issues | 0.54 | 0.00 | 0.83 |

| Contribution to economic development | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | |

| Prevention and mitigation of armed conflict | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Technology development | 0.27 | 0.13 | 0.33 | |

| Corruption | 0.75 | 0.25 | 1.00 | |

| Ethical treatment of animals | 0.50 | 0.13 | 0.50 | |

| Poverty alleviation | 1.00 | 0.75 | 1.00 | |

| Suppliers | Fair competition | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 |

| Promoting social responsibility | 0.44 | 0.00 | 0.25 | |

| Supplier relationships (farmers) | 0.54 | 0.00 | 0.88 | |

| Respect of intellectual property rights | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.50 | |

| Wealth distribution | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | |

| Shareholders | Manage the investment | 0.58 | 0.56 | 0.33 |

| Agreement mutualism | 0.58 | 0.75 | 0.33 | |

| Decision-making involvement | 0.58 | 0.25 | 0.33 | |

| Managing continuous communication | 0.58 | 0.50 | 0.33 | |

| Maximize on creating the value added from the investment | 0.58 | 0.50 | 0.33 | |

| Children | Education provided in local community | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.25 |

| Health issues for children as consumers | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Child-related marketing concerns | 1.00 | 0.75 | 1.00 |

Table A2.

Social impact per subcategory of the three coffee industry management systems.

Table A2.

Social impact per subcategory of the three coffee industry management systems.

| Stakeholder | Performance and Impact Subcategories | Private | Middlemen | Farmer Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workers/employees | Freedom of association and collective bargaining | 0.48 | 0.25 | 0.67 |

| Child labor | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Fair wage | 0.56 | 0.25 | 0.75 | |

| Working hours | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | |

| Forced labor | 0.54 | 0.50 | 0.50 | |

| Equal opportunity and discrimination | 0.65 | 0.50 | 0.75 | |

| Health and safety | 0.67 | 0.42 | 0.53 | |

| Social benefit/social security | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.25 | |

| Employment relationship | 0.66 | 0.56 | 0.58 | |

| Sexual harassment | 0.60 | 0.63 | 0.75 | |

| Smallholders, including farmers | 0.50 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Consumers | Health and safety | 0.88 | 0.75 | 0.88 |

| Feedback mechanism | 0.88 | 0.63 | 0.83 | |

| Consumer privacy | 0.74 | 0.50 | 0.50 | |

| Transparency | 0.91 | 0.50 | 0.75 | |

| End of product life responsibility | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | |

| Local community | Access to material resources | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.75 |

| Access to immaterial resources | 0.71 | 0.50 | 0.83 | |

| Delocalization and migration | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Cultural heritage | 0.27 | 0.13 | 0.29 | |

| Safe and healthy living conditions | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.75 | |

| Respect indigenous rights | 0.90 | 0.25 | 1.00 | |

| Community engagement | 0.75 | 0.50 | 1.00 | |

| Local employment | 0.98 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Secure living conditions | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.38 | |

| Society | Public commitment to sustainability issues | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.25 |

| Contribution to economic development | 0.60 | 0.50 | 0.75 | |

| Prevention and mitigation of armed conflict | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.13 | |

| Technology development | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.19 | |

| Corruption | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.19 | |

| Ethical treatment of animals | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.38 | |

| Poverty alleviation | 0.46 | 0.25 | 0.42 | |

| Suppliers | Fair competition | 0.77 | 0.25 | 1.00 |

| Promoting social responsibility | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.56 | |

| Supplier relationships (farmers) | 0.46 | 0.13 | 0.75 | |

| Respect of intellectual property rights | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.25 | |

| Wealth distribution | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.67 | |

| Shareholders | Manage the investment | 0.33 | 0.56 | 0.25 |

| Agreement mutualism | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.25 | |

| Decision-making involvement | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.17 | |

| Managing continuous communication | 0.58 | 0.50 | 0.33 | |

| Maximize on creating the value added from the investment | 0.29 | 0.50 | 0.25 | |

| Children | Education provided in the local community | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.25 |

| Health issues for children as consumers | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Child-related marketing concerns | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 |

Table A3.

Social impact of endpoint stakeholder indicators of the three coffee industry management systems.

Table A3.

Social impact of endpoint stakeholder indicators of the three coffee industry management systems.

| Category | Private | Middlemen | Farmer Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Workers/employees | 0.350 | 0.290 | 0.464 |

| Consumers | 0.429 | 0.309 | 0.377 |

| Local community | 0.669 | 0.500 | 0.800 |

| Society | 0.490 | 0.294 | 0.540 |

| Suppliers | 0.398 | 0.143 | 0.615 |

| Shareholders | 0.411 | 0.544 | 0.294 |

| Children | 0.850 | 0.850 | 0.800 |

References

- Rahmah, D.M.; Mardawati, E.; Pujianto, T.; Kastaman, R.; Pramulya, R. Coffee Pulp Biomass Utilization on Coffee Production and Its Impact on Energy Saving, CO2 Emission Reduction, and Economic Value Added to Promote Green Lean Practice in Agriculture Production. Agronomy 2023, 13, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mansour, F.; Jejcic, V. A model calculation of the carbon footprint of agricultural products: The case of Slovenia. Energy 2017, 136, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, S.; Rohani, A.; Aghkhani, M.H.; Abbaspour-Fard, M.H.; Asgharipour, M.R. Sustainability assessment of rice production systems in Mazandaran Province, Iran with emergy analysis and fuzzy logic. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2020, 40, 100744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, M.; Spada, A.; Contò, F.; Pellegrini, G. GHG and cattle farming: CO-assessing the emissions and economic performances in Italy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 3704–3712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, A.; Krukowski, A.; Różańska-Boczula, M. Assessment of sustainability in agriculture of the European Union countries. Agronomy 2019, 9, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troiano, S.; Novelli, V.; Geatti, P.; Marangon, F.; Ceccon, L. Assessment of the sustainability of wild rocket (Diplotaxis tenuifolia) production: Application of a multi-criteria method to different farming systems in the province of Udine. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 97, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinyes, E.; Asin, L.; Alegre, S.; Muñoz, P.; Boschmonart, J.; Gasol, C.M. Life Cycle Assessment of apple and peach production, distribution and consumption in Mediterranean fruit sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 149, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Data Information Center of Agriculture Ministry of Indonesia. Coffee Outlook Indonesia; Data Information Center, Agriculture Ministry of Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmah, D.M.; Putra, A.S.; Ishizaki, R.; Noguchi, R.; Ahamed, T. A Life Cycle Assessment of Organic and Chemical Fertilizers for Coffee Production to Evaluate Sustainability toward the Energy–Environment–Economic Nexus in Indonesia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramulya, R.; Bantacut, T.; Noor, E.; Yani, M.; Zulfajrin, M.; Setiawan, Y.; Pulunggono, H.B.; Sudrajat, S.; Anne, O.; Anwar, S.; et al. Carbon Footprint Calculation of Net CO2 in Agroforestry and Agroindustry of Gayo Arabica Coffee, Indonesia. J. Jordan Biol. Sci. 2023, 16, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coltro, L.; Mourad, A.L.; Oliveira, P.A.P.L.V.; Baddini, J.P.O.A.; Kletecke, R.M. Environmental profile of Brazilian green coffee. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2006, 11, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassard, H.A.; Couch, M.H.; Techa-Erawan, T.; Mclellan, B.C. Product carbon footprint and energy analysis of alternative coffee products in Japan. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 73, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basavalingaiah, K.; Paramesh, V.; Parajuli, R.; Girisha, H.C.; Shivaprasad, M.; Vidyashree, G.V.; Thoma, G.; Hanumanthappa, M.; Yogesh, G.S.; Dhar, S.; et al. Energy flow and life cycle impact assessment of coffee-pepper production systems: An evaluation of conventional, integrated and organic farms in India. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 92, 106687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Alba, I.; Boissy, J.; Chia, E.; Andrieu, N. Integrating diversity of smallholder coffee cropping systems in environmental analysis. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2020, 25, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, A.; Ibarra, A.A.; Galeana-pizaña, J.M.; Manuel, J. Changes over Time Matter: A Cycle of Participatory Sustainability Assessment of Organic Coffee in Chiapas, Mexico. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Marulanda, V.A.; Solarte-Toro, J.C.; Carlos, A.C.A. Economic and social assessment of biorefinerues coffee cut steam. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2020, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Benoît-norris, C.; Vickery-niederman, G.; Valdivia, S.; Franze, J.; Traverso, M.; Ciroth, A.; Mazijn, B. Introducing the UNEP/SETAC methodological sheets for subcategories of social LCA. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2011, 16, 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekener-Petersen, E.; Hoglund, J.; Finneveden, G. Screening Potential Social Impact of Fosil Fuel and Biofuels for Vehicle. Energy Pol. 2014, 73, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyekum, E.O.; Fortuin, K.P.J.; van der Harst, E.J.M. Environmental and social life cycle assessment of bamboo bicycle frames made in Ghana. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 1069–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.U.; Poon, C.S.; Dong, Y.H.; Lo, I.M.C.; Cheng, J.C.P. Development of social sustainability assessment method and a comparative case study on assessing recycled construction materials. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2018, 23, 1654–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maister, K.; Di Noi, C.; Andreas Ciroth, M.S. PSILCA V.3 Database Documentation. A Product Social Impact Life Cycle Assessment Database. 2020. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/366605856_PSILCA_v3_Database_documentation (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- D’Eusanio, M.; Bianca Maria Tragnone, L.P. Social Organisational Life Cycle Assessment and Social Life Cycle Assessment: Adifferent twins? Correlation from a case study. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2022, 27, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, D.; Quinteiro, P.; Pereira, V.; Dias, A.C. Social life cycle assessment based on input-output analysis of the Portuguese pulp and paper sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 330, 129851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunuwila, P.; Rodrigo, V.H.L.; Daigo, I.; Goto, N. Social impact improving model based on a social life cycle assessment for raw rubber production: A case of a Sri Lankan rubber estate. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 338, 130555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haryati, Z.; Subramaniam, V.; Noor, Z.Z.; Hashim, Z.; Loh, S.K.; Aziz, A.A. Social life cycle assessment of crude palm oil production in Malaysia. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 29, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, D.; Burgess, M. An environmental, energetic and economic comparison of organic and conventional farming systems. Integr. Pest Manag. Pestic. Probl. 2014, 3, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thies, C.; Kieckhäfer, K.; Spengler, T.S.; Sodhi, M.S. Assessment of social sustainability hotspots in the supply chain of lithium-ion batteries. Procedia CIRP 2019, 80, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana Gerta Backers, M.T. Social Life Cycle Assessment in the Construction Industry: Systematic Literature Review and Identification of Relevant Social Indicators for Carbon Reinforced Concrete. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramjeewon, R.K.F.T. Comparative life cycle assessment and social life cycle assessment of used polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles in Mauritius. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2013, 18, 155–171. [Google Scholar]

- Serreli, M.; Petti, L.; Raggi, A.; Simboli, A.; Luliano, G. Social life cycle assessment of an innovative indutrial wastewater treatment plant. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2021, 26, 1878–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobos-Chavero, S.; Madrid-Lopez, C.; Villalba, G.; Durany, X.G.; Huckstadt, A.B.; Matthias Finkbeiner, A.L. Environmental and Social Life Cycle Assessment of growing media for urban rooftop farming. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2021, 26, 2085–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Guideline for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Product and Organization; UN Environmental Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rebolledo-Leiva, R.; Moreira, M.T.; González-García, S. Progress of social assessment in the framework of bioeconomy under a life cycle perspective. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 175, 113162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halog, A.; Manik, Y. Life Cycle Sustainability Assessments. Encycl. Inorg. Bioinorg. Chem. 2016, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantas, A.; Stamford, L.; Azapagic, A. A framework for evaluating life cycle eco-efficiency and an application in the confectionary and frozen-desserts sectors. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 21, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, G.; Vogel, E.; Decian, M.; Farinha, M.J.U.S.; Bernardo, L.V.M.; Borges, J.A.R.; Gimenes, R.M.T.; Garcia, R.G.; Ruviaro, C.F. Assessing the eco-efficiency of different poultry production systems: An approach using life cycle assessment and economic value added. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 24, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, C.; Møller, H.; Johnsen, F.M.; Saxegård, S.; Brunsdon, E.R.; Alvseike, O.A. Life cycle sustainability assessment of a novel slaughter concept. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 272, 122651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandra, A.; Stefan, S. Development of a social impact assessment methodology. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2013, 18, 1106–1115. [Google Scholar]

- Ciroth, A.; Franze, J. LCA of an Ecolabeled Notebook: Consideration of Social and Environmental Impacts along the Entire Life Cycle; UN Environmental Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2011. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).