Abstract

Sustainable collaboration among teams drives sustainable public–private partnership (PPP) projects, and the interactions, perceptions, and behaviors of project teams with ad hoc decision-making power critically impact collaborative performance in PPP contexts. While the role relationships between subjective interdependence, collective behaviors, team processes, and performance in PPP project teams are yet to be clarified, further validation is needed to embed this logic in project management. This study aims to clarify the role relationships among the four variables of team interdependence, team interaction, team performance, and government participation. Through an empirical investigation of the data of 367 samples of PPP project teams and data analysis by SPSS 26.0 and Amos 23.0, it is found that team interdependence (task interdependence, result interdependence) has a significant positive effect on cooperative performance, and team interaction plays a mediating role in this process. Compared with enterprises with low government share, team interdependence with high government share has a significant positive effect on the team cooperation performance of PPP projects and has a positive moderating effect on the influence mechanism of team cooperation performance. Based on this, this paper proposes strategies for PPP project team management and sustainable development. It suggests corresponding suggestions for improving PPP project team performance and sustainable development.

1. Introduction

The government and social capital cooperation model (public–private partnership model) is a long-term infrastructure and public services partnership [1,2,3]. Usually, social capital is responsible for designing, constructing, operating, and maintaining most of the infrastructure and obtaining a reasonable return on investment through “user fees” and, if necessary, “government fees”; government departments are responsible for price and quality control of infrastructure and public services to ensure maximum public benefit. The government is responsible for the price and quality control of infrastructure and public services to ensure maximum public interest [4]. As a mainstream mode of infrastructure and public service provision in China, the public–private partnership is becoming increasingly prominent in its beneficial role in expanding domestic demand and stabilizing investment and growth [5]. However, there are some significant problems in its development process, mainly in the form of uncoordinated tasks among public–private partnership project teams, leading to project interruptions and failures. Due to the heterogeneous attributes and complex capital composition of public–private partnership project team members, the project’s failure significantly impacts the regional economy and society. Therefore, interdependent cooperation among teams directly affects the success or failure of public–private partnership projects, and sustainable cooperation among teams determines the sustainable development of projects to a certain extent. In order to achieve sustainable economic, social, and environmental development, there is an urgent need to think deeply about the public–private partnership model with the concept of sustainable development, and the sustainable cooperation of the team plays a vital role in the sustainable development of public–private partnership projects and guiding the direction of social investment [6,7].

Teams are gradually becoming the basic work unit through which organizations accomplish complex tasks, optimizing organizational tasks and balancing organizational and individual interests while increasing organizational flexibility and improving overall performance [8,9]. Facing the uncertainty of the internal and external environment of public–private partnership projects and the increasingly blurred boundaries of engineering organizations, individual organizations or subjects are increasingly unable to adapt to the complexity and uncertainty of projects and meet the needs of the professional division of labor and value creation of projects. Forming project teams with cross-disciplinary, cultural differences and heterogeneous resources based on the project environment, contractual constraints, and subject expectations is an essential organizational basis for the collaborative achievement of public–private partnership project goals and performance [10,11,12]. In public–private partnership practice, 32.2% of railroad projects, 57.3% of road projects, and 74.4% of water supply and sanitation projects worldwide have failed, such as renegotiation [13]. As of August 2021, 4393 judgments involving public–private partnership projects, involving contracts, commitments, and changes, were published on the website of Chinese judges, which indirectly reflects the increasingly prominent problems of public–private partnership project implementation in China. However, public–private partnership projects depend on sincere cooperation between the two sides of the transaction, and their core interest lies in achieving the investors’ interest return claims while accomplishing the project’s engineering objectives. The realization of engineering objectives and interest return depends on the virtuous synergistic behavior between each other during the implementation of PPP projects [2,14].

The increased interdependence of public–private partnership project team subjects can motivate social capital to focus on the government’s project goals and value claims, thus achieving the expectation of effective conflict resolution [15]. It is important to emphasize that although the specific objectives of the partnership between government and social capital entities are multidimensional, the underlying goal is to leverage the comparative advantages of the partnership for project value creation rather than protect or expand their respective established advantages [16,17,18]. For public–private partnership projects, after the contract between the partners is signed and practical, the project team jointly formed by the government and social capital carries out specific activities such as resource allocation, communication and coordination, information feedback, and performance management around the critical tasks of risk sharing and risk management [18,19,20], and the project team derives interdependent project management behaviors (such as risk sharing, conflict resolution, and asset operation, etc.) among team members based on their own capabilities and professional advantages in order to achieve the contract goals, i.e., the project performance not only requires the performance of the main body according to the law but also depends on the excellent performance behavior of the main body of the team [21]. However, in the practice of PPP projects, project teams often overemphasize the role of economic incentives in contract performance while ignoring the characteristics of interdependence among subjects and attaching importance to the legal effect of contract terms while disregarding the extra-contractual voluntary performance behavior of subjects. Although scholars have paid attention to the mechanism of influence between team interdependence and performance [21,22], especially the mechanism of action of task interdependence [23,24], there is a lack of discussion on the explanation of other dimensions of team interdependence. The research outcomes above are only limited to human resource management. At the same time, differences in team members’ backgrounds impact team performance [25]. To achieve contractual goals, PPP project teams are formed by members from two different organizational attributes (public and for-profit). The role relationships between their subject interdependence, cooperative behavior, team processes, and performance need to be clarified, and embedding this logical relationship in a project management context requires further validation. Therefore, taking PPP projects as a carrier, we explore how team interdependence contributes to the positive interaction of PPP project team members and the impact path of team members’ collective performance. We also provide new ideas for PPP project team management.

Over the decades, scholars have conducted numerous studies on the advantages of PPPs. However, the sustainability of PPPs is the most critical aspect [2,3]. Due to the inconsistency of tasks among PPP project teams, there is less interaction among team members, which may lead to compromised team performance and, ultimately, the sustainability of the PPP team and the project. For the potential advantages of PPPs to be realized between groups, stakeholders must focus on performance improvement and sustainability in PPP project transactions [11,19,21]; furthermore, research on factors affecting the application and implementation of PPPs is essential for service delivery and determining the sustainability of PPPs [21,26]. The main contribution of this study is to improve team performance by constructing the cooperative goal interdependence of PPP project team members to promote positive interactions among team members and to help PPP project teams better understand and grasp the influence of the relationship between team interdependence and team performance, improve their team operation mechanism, and enhance team performance more effectively in the construction and operation of PPP projects.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis

Deutsch (1949) first proposed the theory of cooperation and competition (TOC) in the journal Human Relations, which was initially proposed to fill the gap in research on collaboration and competition affecting team processes [27]. The theory of cooperation and competition not only defines the types of team interdependence relationships but also argues for a focus on three variables: team interdependence, interaction patterns, and consequences, and proposes a vital hypothesis based on the three variables; namely, that an individual’s perception of goal interdependence influences their orientation and interactions with other members of the team, i.e., that a team member’s perception of a goal influences the team member’s performance of the behavior, which can have an impact on the team’s outcome. Team interaction is a collection of team members’ behavioral performance that reflects the reality of team members’ cooperation and is an essential variable of the team process. Tjosvold et al. [28], through the theory of cooperation and competition, confirmed that the interdependence of cooperative goals leads to cooperative dependencies in teams and, in this context, promotes positive team interactions (e.g., team members support each other, share information and resources together, and exchange their views), which leads to mutual recognition between subjects and the establishment of a solid partnership, which contributes to the attainment of the goals and positively affects the team’s performance. It can be seen that team interaction has a mediating effect between goal interdependence and team performance; in addition, research on PPP project teams focuses more on the behavior of individual subjects and lacks the examination of inter-subjective interactions [29]. In contrast, cooperative goal interdependence provides a new research perspective for analyzing the inter-subjective interactions of PPP projects. Therefore, exploring the effects of team interdependence on team interaction and performance in PPP projects is essential.

Resource dependency theory emphasizes that organizations and their environment are interdependent and inter-exchangeable. The PPP model is a specific form of organizational cooperation in which resource exchange is essential to the partnership between the government and the social capitalist. In PPP projects, the government and social capitalists enter into a partnership aimed at leveraging the strengths of both the public and private sectors for project value creation; resources are the basis for inter-organizational cooperation, and there are complementarities between the government and the social capitalists in terms of critical resources such as material, technology, experience, and policies. Therefore, the government and social capital parties complete the rational allocation of resources and resource integration through inter-organizational resource exchange. The process of resource exchange is the process of inter-organizational interaction; the government and social capital parties in the business of resources will inevitably be accompanied by the exchange of information, coordination of their behavior, and the establishment of organizational mutual trust and other interactive behaviors [30], and at the same time, the resource dependence characteristics of the two will also promote the interests of both parties to promote the interdependent relationship between each other, deriving from the interdependence of the team members in the management of the project behavior [31]. In summary, the government and the social capital party have complementary resources in PPP projects. There is interdependence in resources, and the two parties are bound to have interactive behavior when exchanging resources. Resource dependence theory explains the resource advantages of the government and social capitalists, reveals the essence of their cooperative behavior, provides theoretical support for the study of interactive behavior in PPP projects, and lays the foundation for further research on the relationship between interdependence of collective goals, team interaction, and team performance.

2.1. Team Interdependence and Cooperative Performance

A team is a collection of interdependent individuals who share and fulfill obligations in order to accomplish the goals required by the organization. Interdependence is the degree to which different subjects in a team depend on each other to accomplish a given job [22,23], and interdependence in terms of tasks, actions, outputs, or rewards has a significant impact on the cooperative performance of team members [25,32,33,34]. Feng et al. (2022) [26] found that the government tends to establish a long-term friendly partnership with the private sector and shows a series of behavioral responses, such as trust and cooperation, and the cooperation between the two sides depends on each other; thus, among them, outcome interdependence refers to the extent to which team subjects rely on the performance of other team subjects for significant outputs, and task interdependence describes the relationships among team members that stimulate interactive behaviors, coordination needs, and communication processes among team members within the team processors who rely on each other, contributing to the successful completion of work tasks and the achievement of higher work goals and desired outcomes [23]. Du et al. (2023) [35] established a systematic operational performance assessment framework for PPP transportation infrastructure projects and found that PPP project performance is closely related to the four dimensions of innovatively integrating finance, multi-stakeholder satisfaction, operation and maintenance quality, and sustainability performance. Saad et al. (2021) [36] found that if the partners in a PPP are satisfied with their cooperation, the partnership is less exposed to relational risky behavior or opportunistic behavior. For PPP project teams, the government and social capital parties each have different resource endowments and interest demands, but at the same time, they are based on the successful construction and operation of PPP projects to achieve their respective interest demands [15,24,37], i.e., there is both task interdependence and outcome interdependence in PPP project teams, thus promoting members’ interdependence and goal convergence, maximizing team effectiveness and promoting synergistic benefits. However, government actions (including government pre-preparation, government support and assurance, project governance, and government services) in PPP projects have a significant impact on project performance, especially government services involving dimensions of commitment, attitude, and communication, which will affect partnership, smooth project implementation, and performance [38]. For example, in the Xinling Highway PPP project in Huixian City, due to the coordination and communication of the Huixian Municipal People’s Government, the highway was not properly connected with the highway in Shanxi Province and became a “disconnected road”; the Huixian Municipal People’s Government did not complete its main obligations under the contract, and the social capital party failed to fully provide the contract output requirements (from China Judgment (https://wenshu.court.gov.cn/) (accessed on 15 October 2021), “Huixian Municipal People’s Government, Henan Xinling Highway Construction Investment Co., Ltd. Contract Dispute Second Trial Civil Verdict”, Case No. (2018) Supreme Law Civil Final 1319), and the PPP project was eventually terminated, the partnership was dissolved, and the performance was lost. In addition, the “two evaluations and one case (financial affordability demonstration, value-for-money evaluation, and implementation plan)” are the outcomes of the government-led pre-proposal of PPP projects, the reliability and reasonableness of which directly affect the social capital party’s bidding documents, and the social capital party relies on the “two evaluations and one case” (especially the implementation plan) to carry out project construction and operation after winning the bid, which in turn affects whether the social capital party can provide public goods or services to meet the output requirements agreed in the contract. Based on this, the following research hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Team interdependence has a positive effect on cooperation performance.

Hypothesis 1a (H1a).

Task interdependence has a positive effect on cooperation performance.

Hypothesis 1b (H1b).

Interdependence of outcomes positively affects cooperation performance.

2.2. The Mediating Effect of Team Interaction

Interaction is seen as an activity that must be addressed in project management efforts [38,39]. Team interaction is the main element of the project team building and management process [11,40], which is mainly reflected in a series of cognitive, verbal, and action-oriented interactions among team members [8,41]. These actions are the essential link between team “input” and “output” and have a significant impact on team members’ collective performance [32,42]. In addition, interdependence fuels partners to invest in dedicated resource management uncertainty, integrate complementary resources and capabilities, develop knowledge-sharing paths, and increase external coordination, sustaining collaborative behavior, reducing transaction costs, and improving cooperation performance [43]. Higher team member task interdependence motivates team members to develop frequent interactions around specific task resolution and decision-making [23]; high outcome interdependence then motivates team subjects to adopt pro-social behaviors and engage in interpersonal interactions, i.e., when individual outcomes depend on the cooperative efforts of team members, team member relationships become critical [44]. The more committed they are to each other, the stronger the bonds between team members are more robust; they are more likely to adopt pro-social motives and act to improve relationships, which in turn has an impact on team members’ collective performance; for example, high cohesion teams show higher productivity in performing tasks, which contributes to improved performance [45].

PPP project teams usually comprise relatively decentralized and relatively independent team members. This structure is not an enabling environment. Therefore, the project team must seek the best combination of time, cost, and quality [46]. The resource dependence theory proposes that in PPP projects, the resources between the government and the social capitalist are complementary, and the exchange of resources between the two parties is accompanied by communication and exchange activities. The theory of cooperation and competition suggests that reciprocal conditions can increase the frequency of communication and exchange between team members and improve the motivation of information exchange. Team interaction includes team communication, coordination, and cooperation, and interactive communication is the key to establishing team member relationships [47]. In the high cooperation goal interdependence scenario, the government and social capitalists are willing to exchange opinions and views and engage in positive communication and resource exchange [48]. In addition, a high degree of cooperation goal interdependence leads to a friendly and stable relationship between the government and the social capitalists, which is conducive to communication and information exchange, thus further facilitating a higher level of communication among team members [49]. In order to improve team performance, project teams constantly seek work methods that avoid mistakes, increase efficiency, and reduce the risk of failure [50]. During team interactions, team members can strengthen their knowledge, skills, and techniques to achieve higher quality solutions, reduce errors, and thus improve teamwork performance [51].

Team communication is an integral part of team interaction and the basis for guaranteeing cooperation. Team communication can realize the sharing of information and knowledge, prompting team members to understand each other and grasp the project’s progress [46]. Team members share each other’s information and ideas, which helps to reduce problems and thus better achieve the team’s shared goals [47,48]. Due to the long-term and uncertain nature of PPP projects, both the government and social capital acquire limited and lagging information, and the communication mechanism can effectively solve unexpected problems, strengthen the commitment of the government and social capital to the project’s win–win situation, and improve the team’s performance [15]. PPP projects rely on the sincere cooperation of both parties to the transaction, the core of which lies in the completion of the project objectives under the premise of the return of the investor’s interests and the realization of the project objectives, and the return of the interests depends on the benign synergistic behavior between each other in the process of PPP project implementation [14]. A highly cohesive PPP project team is conducive to the government and social capitalists adopting synergistic behaviors and showing higher work efficiency in executing tasks, thus improving team performance [52].

The government gives complete trust and support to the private sector, and both sides communicate smoothly and interact well. In PPP projects, if the government and the private sector get along on an equal footing, the cooperation between the two sides will be smooth. In addition, the private sector has a certain degree of control and initiative. Giving full play to the private sector’s advantages in project management is conducive to controlling costs, progress, and quality [21]. After the public–private partnership contract is signed and practical, the project team derives interdependent behaviors due to activities such as risk sharing, benefit allocation, and resource allocation, which are presented in the whole process of project implementation in the concrete form of task discussion and exchange, information feedback, and conflict management. Interaction involves exchanging materials, information, ideas, or other resources [53]. Conflict, communication, cohesion, interpersonal trust, and type of interaction are critical variables in team interactions that have an essential role in team interaction. Through interaction, team members achieve information exchange, resource sharing, and emotional communication, and the goals among team members converge and resonate more easily and emotionally. Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Team interdependence positively affects team interaction.

Hypothesis 2a (H2a).

Task interdependence positively affects team interaction.

Hypothesis 2b (H2b).

Interdependence of results positively affects team interactions.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Team interaction has a positive effect on cooperation performance.

2.3. Moderating Effect of Government Equity Participation

Qian et al. (2023) find that state-owned equity has a significant positive impact on corporate environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance by mitigating the opportunism of controlling shareholders and increasing the positive involvement of firms in pursuing long-term goals [16]. In public–private partnership projects, the government and social capital entities invest dedicated resources to provide the contracted public goods or services to form a “bilateral lock-in” transaction relationship or interdependence [17,18]; the government (public interest claims) and social capital (capital interest claims) with conflicting objectives establish a cooperative relationship and derive interdependent behaviors in PPP projects [15,54]. Each partner assigns and authorizes appropriate personnel to form a specific PPP project team (or project company) to perform contractual responsibilities and obligations and create value. In addition, in the context of government shareholding in the equity structure of the project company, social capital entities can establish a formal government–enterprise relationship using a project contract, and this relationship can, to a certain extent, generate resource and information effects and thus alleviate the project company’s financing constraints [38,55], thereby reducing the project team’s transaction costs and improving cooperation performance. At the same time, government equity participation has a better guarantee power for the smooth implementation of PPP projects [56], and the government can also use monetary funds and decision-making power on significant matters to promote the performance of project contracts or the achievement of collective performance goals as well as individual goal satisfaction [57]. However, this government–enterprise relationship can also hinder the innovative decision-making of project organizations; for example, government shareholding hurts performance [58], and if the goal of government shareholding is a “performance project”, excessive or inappropriate interventions induce increased project costs or inefficient decision making [53,59], which affects the interactive behavior (e.g., passive acceptance of interventions by social capital) and the performance of cooperative agents. Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed in this paper:

Hypothesis 4a (H4a).

Government equity participation plays a moderating role in the path of the effect of team interdependence on cooperative performance.

Hypothesis 4b (H4b).

Government equity participation plays a moderating role in the path of influence of team interdependence on team interaction.

The continuous investment in dedicated assets reflects the recognition of the partnership and the affirmation of the reliability of commitment between the contracting parties, which helps to strengthen the communication of resources and deepen the partnership between them [42,60,61]; moreover, as the participation of the subject increases, the degree of interdependence, information sharing, and communication and interaction between the partners becomes stronger [15,39], thus promoting project success and improved cooperation performance. For public–private partnership projects, Hu Zhen et al. (2019) [62] argue that government equity participation in PPP projects has a positive effect relationship on subject goal achievement and project performance, and in order to achieve their respective expectations and contract goals, government and social capital subjects will actively communicate and strengthen their interactive behaviors after investing dedicated resources, thus contributing to the continuous performance of the project contract and the achievement of performance goals. In addition, when the government participates in the PPP project company, the government has the right to question critical matters such as the project company’s operation and management decisions, cost and benefit, resource allocation, and risk distribution; at this time, the government plays the dual role of both shareholder and regulator and usually intervenes using administrative concessions when disputes arise over the financing model, operation plan, and benefit allocation during the project construction and operation [3,38]. Hu Zhen et al. (2020) [63] also found during their study of government equity participation in PPP projects in Japan that the government has an absolute advantage and a high voice in project negotiation, negotiation, and implementation, diluting the spirit of cooperation and leading to inefficient and lossy project operations. Based on this, this paper proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4c (H4c).

Government equity participation plays a moderating role in the relationship between the effects of team interaction on cooperation performance.

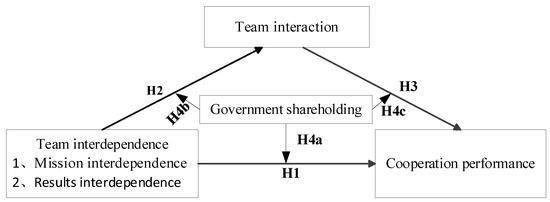

Based on the above analysis, this paper argues that government shareholding attempts to explain the mechanism of team interdependence on cooperative performance in PPP projects, and a comprehensive and in-depth grasp of the project team process makes its research on team interdependence and cooperative performance more relevant to the actual situation. Combining H4a, H4b, and H4c, the following comprehensive hypotheses are proposed and form the complete logical model of this study (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hypothetical model.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Government equity participation moderates the path of team interdependence and team interaction on cooperation performance.

3. Research Design

3.1. Sample Source and Data Collection

In this study, simple random sampling was used to conduct the survey. Simple random sampling ensures equal opportunity so that all relevant respondents can receive the distribution of this questionnaire. It makes the final recovered data highly applicable and avoids limitations and peculiarities to a certain extent.

The questionnaire collection and survey process are divided into two times: the first is for the pilot study and the second is for the formal questionnaire survey. The first trial research used the online distribution of questionnaires, mainly because the first trial research offline distribution of questionnaires does not have the conditions, so the questionnaire is mainly distributed through the questionnaire star and mailbox. The first trial survey questionnaire is also used to improve the content of the questionnaire in order to lay the foundation for the second formal questionnaire survey. The second questionnaire combines online and offline, and the offline questionnaire is mainly distributed to the experts and entrepreneurs in the PPP forum meeting, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Questionnaire collection schedule.

The questionnaire of this study consisted of two parts: the first part was a survey of the basic information of the subjects and their teams and the second part was a survey of the measured variables. The questionnaire was scored in the form of a Likert-5 scale. The research was conducted in the following two ways. (a) Online distribution: electronic questionnaires were distributed in the public–private partnership expert exchange group of the National Development and Reform Comtask and the PPP expert exchange group of the Ministry of Finance, which brought together middle and senior managers of famous PPP consulting companies in China, and 59 valid questionnaires were collected. Electronic questionnaires were distributed by the staff of PPP centers of provincial finance departments in their work groups, and 141 valid questionnaires were collected. (b) Offline distribution: we participated in the China PPP Investment Forum and China PPP Academic Summit Forum, which are attended mainly by government personnel and representatives of social capital entities engaged in PPP projects for a long time. Two hundred and nine paper questionnaires were distributed twice, and one hundred and eighty-four valid questionnaires were returned.

Most subjects worked in only one public–private partnership project team, and data for subjects who worked in two or more teams simultaneously were removed. The questionnaire instruction section specifically emphasized “respond to the current team situation” to prevent subjects from reflecting on prior experience in the current measure. After excluding individual invalid questionnaires with incomplete and irregular answers, 367 valid questionnaires were finally obtained, with a valid rate of 89.7%, and the basic information of the sample is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of the respondents.

3.2. Measurement of Variables

Team interdependence mainly involves task and outcome interdependence among team subjects in public–private partnership projects. It draws on the research outcomes of Courtright et al. (2015) [64] and Jing Ren et al. (2007) [65] to design measurement questions. The cooperation performance draws on the research findings of Jie-Nan Guo et al. (2020) [66] and Wen-Cong Ma et al. (2018) [67] to design measurement questions. Team interaction draws on the research findings of Marlow et al. (2018) [68] and Sun, Xiuxia, et al. (2021) [40] to design the measurement questions.

Government equity participation mainly refers to the proportion of government equity in the public–private partnership project company. Most local governments have a 10% share in PPP project companies in China [62]. Tian Lihui (2005) [59] argues that there is an asymmetric U-shaped relationship between the size of government shareholding and firm performance, with the role of the relationship between the two turns in the context of government shareholding of about 30%. In addition, through statistical analysis of national demonstration projects in the project database of the Ministry of Finance PPP Center, it is found that the proportion of government equity in PPP projects with government shareholding is mainly concentrated below 30%. Based on this, this study classifies the proportion of government equity participation into three types (greater than 30%, between 10% and 30%, and less than 10%). Combining the variable attributes of government equity participation, the model of moderating effects with latent variables is analyzed using grouped structural equations when the moderating variable is categorical, using the research outcomes of Wen Zhonglin et al. (2020) [69]. Information on the variables is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Variable information.

3.3. Homogeneous Variance Test

In this study, team interdependence, team interaction, and cooperation performance in one questionnaire were all assessed by one public–private partnership project personnel, so there may be a common method bias. For this reason, after data collection, a Harman one-way test was conducted on the variables of interest. The variables of team interdependence, team interaction, and cooperation performance were all placed into one exploratory factor analysis to test the outcomes of the unrotated factor analysis. The outcomes revealed that the factor analysis extracted five factors with characteristic roots greater than one, and the first common factor variance explained 36.045% (<40%). Therefore, there was no significant standard method bias in the data of this study. The results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Interpretation of the common method bias test.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

Since the data used in this paper are from a randomized questionnaire, the questionnaire data need to be tested for reliability and validity. Reliability refers to the reliability, consistency, and stability of the scale. The most applied and mature method for the reliability test method is to rely on Cronbach’s coefficient in SPSS. It is generally recognized that Cronbach’s coefficient should be between 0 and 1. If the reliability coefficient of the scale is above 0.9, it means that the scale’s reliability is excellent; if the reliability coefficient of the scale is between 0.8 and 0.9, it means that the scale’s reliability is inferior. If the reliability coefficient of the scale is between 0.7 and 0.8, the scale’s reliability is acceptable; if the reliability coefficient of the scale is lower than 0.7, the scale’s reliability is not credible. Validity refers to the degree of validity and accuracy of the questionnaire. Validity is generally categorized into content validity and structural validity. Content validity is generally assessed using the KOM value to test whether the factor can be analyzed. Generally speaking, a KMO value above 0.9 is very suitable for factor analysis, 0.8–0.9 is suitable for factor analysis, 0.7–0.8 is acceptable, 0.6–0.7 is barely acceptable, and below 0.6 is very unsuitable. After the KMO value passes the test, the structural validity test can be conducted. Amos 26.0 software examined structural validity, which yielded values such as X2/DF, RMSEA, and GFI. It is worth noting that high reliability is necessary for a scale’s high validity; high reliability does not necessarily imply high validity. Therefore, this paper uses a combination of SPSS and Amos to combine reliability and validity to verify the reliability of the questionnaire data.

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used to examine the scale’s reliability. Table 5 shows that the alpha values of each latent variable reached above 0.7, indicating a high internal consistency reliability of the scale. Table 5 shows that the KMO values of all factors range from 0.746 to 0.851, which indicates that the variables have reliable explanatory power and good representativeness.

Table 5.

Statistical analysis outcomes.

The correlation coefficients between task interdependence, outcome interdependence, team interaction, and collective performance were measured using Pearson correlation analysis in SPSS 26.0, and the outcomes are shown in Table 5. The outcomes of the correlation analysis showed that task interdependence, outcome interdependence, team interaction, and collective performance showed significant correlations, which laid a good foundation for further exploring the relationship between the variables in this study.

4.2. Model Analysis

4.2.1. Direct Utility and Mediating Role Tests

In order to test the discriminant validity between the four variables of this study, a validated factor analysis was conducted using Amos 26.0, and the six fit indicators, X2/DF, RMSEA, GFI, AGFI, CFI, and NFI, were used to compare the goodness of fit of the model. The results showed that the six-factor model fit well (X2/DF = 1.173, RMSEA = 0.029, GFI = 0.869, AGFI = 0.849, CFI = 0.981, and NFI = 0.883), which indicated that the four variables had good discriminant validity. Specific results are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Validated factor analysis of differentiated validity results.

AMOS23 was applied to structural equation modeling, and the sample information obtained from the questionnaire was used to test the role relationship between team interdependence, team interaction, government shareholding, and collective performance. As can be seen in Table 7, the factor loadings of the observed indicators for each potential variable passed the significance test of p < 0.01, and the goodness of fit indicators in the last row of Table 7 were also within the reference values, indicating a good model fit. In addition, Table 7 also presents the standardized coefficients squared (SMCs) for each measured variable, with SMC values greater than 0.5; for example, the SMC value of TI4 in the task interdependence dimension is relatively large, which indicates that the observed variable TI4 is explained by task interdependence to a degree of 73.4%; this also reflects that the interdependence characteristics of the work tasks in each phase of the PPP project largely determine the team members’ task interdependence characteristics, which is consistent with the findings of Quelin et al. (2019) [37], who analyzed the project task interdependence characteristics from a value creation perspective.

Table 7.

Factor load analysis.

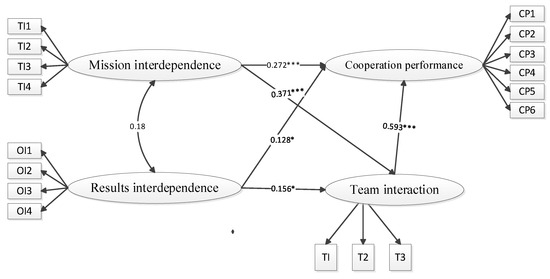

4.2.2. Direct Effect

According to Figure 2, it can be seen that task interdependence has a significant positive effect on team cooperation performance (β = 0.272, p < 0.01), outcome interdependence has a significant positive effect on cooperation performance (β = 0.128, p < 0.1), and Hypotheses H1a and H1b pass statistical tests, which also reflect that team cooperation performance in public–private partnership projects is influenced by team task interdependence and outcome interdependence. This study showed that the collective performance of PPP project team members was enhanced by increasing the interdependence of PPP project team members in terms of tasks and outcomes, and Hypothesis H1 passed the test. This outcome supports and complements the studies of Hambrick et al. (2015) [32]. Sun Mouxuan et al. (2021) [15] validated the positive impact of team interdependence on team performance through an empirical study of structural interdependence in corporate executive teams. Sun Mouxuan et al. (2021) [15] demonstrated the relationship between interdependent behaviors on willingness to cooperate and performance. Therefore, the role of interdependent behaviors among team members is critical and significant for the collective performance of team members in both PPP project teams and corporate executive teams.

Figure 2.

Final model. * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001.

Second, task interdependence had a significant positive effect on team interaction (β = 0.371, p < 0.01), and the resultant interdependence had a significant positive effect on team interaction (β = 0.156, p < 0.1), and Hypotheses H2a and H2b passed the test; this indicates that more vital interdependence in public–private partnership projects increases team members’ scarce resources, credible commitments, and constructive opinions about each other’s need, which in turn fuels positive interaction behaviors among team members. This outcome also further echoes the findings of Courtright et al. (2015) [64], Kumaraswamy et al. (2008) [12], and Kivleniece et al. (2012) [17]. Practitioners agree on the positive effect of subject interdependence on team interaction behavior, which is particularly evident in the process of PPP project operation. When the level of interdependence is low, the project management plan is usually oriented to the goals of the dominant partner, and any renegotiation during implementation can be protracted. In contrast, when interdependence is high, the project management plan is usually developed with multiple discussions and adjustments, balancing project goals with individual goals, and proactively investing resources in risk prevention during implementation. In addition, team interaction significantly positively affects cooperative performance (β = 0.593, p < 0.01). Hypothesis H3 holds, which predicts that a 1-unit change in team interaction will change team members’ collective performance by 0.593 units, regardless of other factors, indicating that frequent interaction between team members enables information sharing and conflict coordination, which in turn reduces renegotiation transaction costs, maintains the stability of teamwork relationships, and improves team members’ collective performance; this supports the “mechanism of team interaction on performance” proposed by Mathieu et al. (2017) [8] and indirectly responds to Fan Daoan et al.’s (2019) [14] “Cooperating agents in PPP project execution the synergistic behavior formed by interactive interactions affects project construction, operational efficiency, and performance”.

4.2.3. Intermediary Effect

To explore the mediating effect between variables, the Bootstrap method was used to set the sample size to draw 3000 with an interval of 95% to test the mediating effect. Table 8 shows some of the results of mediating effect. Team interaction mediates the relationship between task interdependence (outcome interdependence) and cooperative performance role. According to Table 8, the direct effect of team interdependence on cooperative performance is greater than the mediating effect, i.e., collective performance is most influenced by team interdependence and second most influenced by team interaction. In public–private partnership projects, project teams composed of government and social capital create task-, goal-, or result-dependent behaviors during the whole project life cycle for effective contract performance and individual goal achievement, which create project value and improve cooperative performance based on bilateral communication, coordination, or exchange based on bilateral resource inputs and project task requirements to create project value and improve cooperative performance based on enhancing the quality of the bilateral partnership. At the same time, this finding partly echoes Courtright et al.’s (2015) [64] suggestion that “team interdependence encourages maximum interaction among team members, further contributing to effective decision making and improved performance”. It supports DeChurch et al.’s (2010) [34] explanation of the mechanism of team interaction on team interdependence and team members’ collective performance from the team process perspective. Moreover, this indirectly supports Kivleniece et al. (2012) [17], who emphasize that the interactive exchange between both government and social capital in PPP projects reinforces the relationship between the role of bilateral dependence on value creation and cooperation outcomes.

Table 8.

Exploration of intermediary effects.

4.3. Moderating Effect of Government Equity Participation

To better study the moderating mechanism of government equity participation on the interrelationship between team interdependence and cooperative performance, referring to the test method of moderating effect model with latent variables by Wen Zhonglin et al. (2020) [69] and Fan Bernai et al. (2016) [70], the cases in the sample were ranked according to the proportion of government equity participation from high to low, and the 1/4 of the total sample with the highest proportion of government equity participation was included in the high government equity ratio group (n1 = 92), denoted as group A; the 1/4 with the lowest proportion of government equity participation was included in the low government equity ratio group (n2 = 92), denoted as group B. The group structure equation was conducted for both groups A and B. The cases in the sample are ranked according to the proportion of government shareholding from high to low, and 1/4 of the total sample with the highest proportion of government shareholding is included in the high government equity group (n1 = 92), denoted as group A. The lowest 1/4 of government shareholding is included in the low government equity group (n2 = 92), denoted as group B. The structural equation analysis of groups A and B is conducted to test the moderating effect of each path of the hypothesized model separately, and the specific testing procedure (The regression coefficients of the structural equations of the two groups are first restricted to be equal, and a χ2 value and the corresponding degrees of freedom are obtained. This restriction is removed, and the model is re-estimated to obtain another χ2 value and the corresponding degrees of freedom. The previous χ2 is subtracted from the later χ2 to obtain a new χ2, whose degrees of freedom are the difference between the degrees of freedom of the two models. The moderating effect is significant if the χ2 test result is statistically significant.) is described in Wen Zhonglin et al. (2020) [69] and Fan Bernai et al. (2016) [70]. Table 7 of the results of the moderating effects analysis shows that:

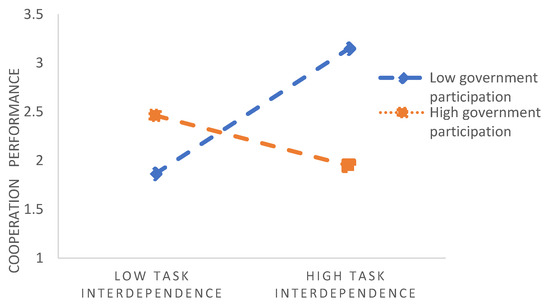

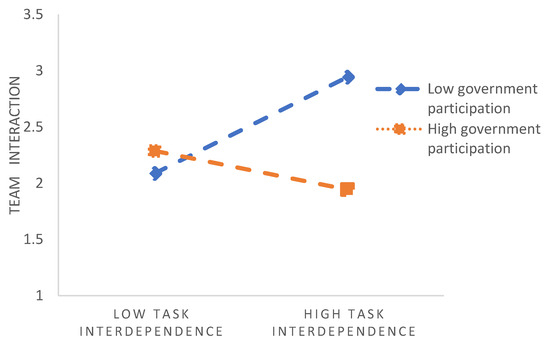

First, government equity participation negatively regulates the relationship between task interdependence and cooperative performance, and the positive effect of team task interdependence on cooperative performance is enhanced when government equity participation is low. This indicates that when the proportion of government equity participation in public–private partnership projects is low, the government has less pressure to invest financial resources in PPP projects and less workload for financial performance assessment, which makes government subjects reduce process intervention and process dependence on social capital subjects. In contrast, social capital parties with more extensive equity participation carry out asset operations and expect to quickly recover the initial investment by the relevant requirements of the project contract or equity agreement, which makes the social capital entities pay more attention to the whole process of PPP projects rather than just the final results. This finding indirectly responds to Li Feng et al. (2021) [57], who stated that “Although a larger proportion of government shareholding in the SPV company provides greater security for the project, it increases the financial pressure and coordination complexity, which is not conducive to the smooth implementation of the project”. This is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The moderating role of government equity participation between task interde-pendence and cooperative performance.

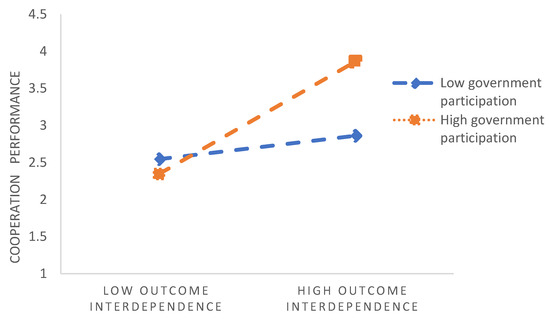

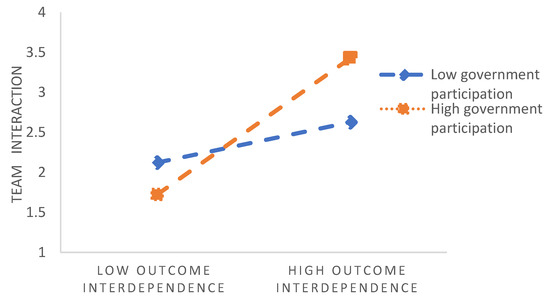

Second, government equity participation positively moderates the relationship between outcome interdependence and team members’ collective performance, and the positive effect of outcome interdependence on team members’ collective performance is enhanced with high government equity participation. This indicates that a higher percentage of equity participation in PPP projects corresponds to more financial investment, and the asset specificity makes the government face the corresponding financial performance assessment, which in turn helps the government to make prudent decisions and focus on the effect of financial investment, especially the financial flow of the whole project process. In addition, government officials or government staff in the team are also concerned about individual performance (e.g., rank treatment, etc.), which motivates government representatives in the team to take the initiative to strengthen the interaction with social capital subjects and increase the mutual dependence of both parties, a result that, to some extent, responds to Cai Xianjun et al.’s (2020) [58] suggestion that “the more significant the promotion incentives of officials, the more likely they are to choose PPP projects in which the government takes more risks”. This is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The moderating role of government equity participation between outcome interdependence and cooperative performance.

Third, government equity participation negatively regulates the role of task interdependence and team interaction, which indicates that when the proportion of government equity participation in public–private partnership projects is low, social capital players focus on each critical task or milestone event in the whole project life cycle in order to recover their investment and obtain investment reward in advance during the operation period, and proactively provide feedback to the government on project construction and operation information and strengthen the interaction and deepen the intensity of cooperative relationship in order to implement the project and achieve the expected goals smoothly. In addition, government equity participation positively regulates the relationship between outcome interdependence and team interaction, which indicates that the interactive behavior among PPP project team members is more directly influenced by team outcome interdependence when the proportion of government equity participation in PPP projects is higher, mainly because the constraints of fiscal budget performance management and government project expenditure performance evaluation help the government side in PPP projects pay attention to the effect of financial capital input and output, and the social capital side is required to allocate resources scientifically and rationally to provide the contracted outputs. This is shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6.

Figure 5.

The moderating role of government participation between task interdependence and team interaction.

Figure 6.

The moderating role of government equity participation between outcome interdependence and team interaction.

Fourth, the negative moderating effect of government equity participation on the positive relationship between team interaction and cooperative performance is insignificant. Although this effect is insignificant, the fitting results show that the positive effect of team interaction on cooperative performance decreases with high government shareholding. The significance of the effect diminishes, and the tendency of negative regulation exists. Higher government shareholding reduces the effect of team interaction on cooperative performance, prompting the government to set intervention strategies scientifically. This is shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

Moderating effect of government equity participation (moderating variable: government equity participation).

5. Conclusions

A review of public–private partnership project research reveals that the existing results mainly focus on risk sharing, and many research results “focus excessively on risk sharing techniques and methods” and “sever the link between project risk sharing agents and performance output”. Through literature combing and logical deduction, this paper establishes a model of the influence mechanism of team members’ cooperative performance in PPP projects with team members’ collective performance as the primary research variable and then uses questionnaires and structural equations to test the influence mechanism of team members’ cooperative performance in PPP projects, focusing on the mediating role of team interaction in the influence mechanism of team interdependence on cooperative performance and the moderating effect of government shareholding in the relationship between the role of team interdependence and cooperative performance. This paper obtains the following main conclusions:

First, team interdependence in public–private partnership programs significantly positively affects team members’ collective performance, with task interdependence having the most significant impact. This corresponds to this paper’s initial Hypotheses H1, H1a, and H1b. On the one hand, PPP projects involve pre-decision, planning and design, bidding and tendering, construction and operation, etc. These main contents follow the law of engineering construction and life cycle characteristics, and the interdependence of tasks is the basis for the smooth implementation of PPP projects. On the other hand, in PPP projects, the realization of individual goals of the government and social capital is not independent. It is necessary to take into account individual goals while realizing the public value goals of the project, i.e., the interdependence of team members’ goals further strengthens the interdependence of tasks and results; on this basis, team members actively invest dedicated resources for project risk sharing and control to achieve project success and performance goals.

Second, team interaction has a positive effect on team performance, and team interdependence has a positive impact on team performance through its positive effect on team interaction. This corresponds to the initial Hypotheses H2, H2a, H2b, and H3. Optimizing team interdependence in public–private partnership projects is conducive to helping team members strengthen interaction and communication, while improving team interaction is conducive to improving team cooperative performance. This view is supported by practitioners who argue that although the PPP project contract specifies the rights and obligations of both partners, the content and duration of the work, and the risk allocation relationship, etc., there are many uncertainties in both the environment in which the project is located and the operational process that affects the success of the project or the performance of the cooperation. It is difficult to rely entirely on the contract to deal with all issues, which requires interactive communication and improvisation between the cooperating parties or team members. As Salvato et al. (2017) [25] point out, “cooperative interdependence will determine positive interactions of mutual trust and support among team members”. Through positive and frequent interactions, team members continuously invest dedicated resources to cope with uncertainty and maintain the cooperative relationship, thus achieving contractual goals and meeting individual expectations.

Third, government equity participation plays a moderating role in the mechanism of influence on teamwork performance, which corresponds to the initial Hypotheses H4a, H4b, H4c, and H5. Government equity participation can enhance teamwork performance, improve the government’s perception of “construction over the operation”, and improve the fit between team interdependence and cooperation performance expectations. In particular, during the operation of public–private partnership projects, government equity participation enhances the guarantee of project success and performance to a certain extent. However, to a certain extent, the pressure of financial responsibility of government equity participation encourages it to use administrative control to interfere with project operation and management, which increases the difficulty of coordination and complexity of the game between project partners, thus increasing project costs and affecting cooperation performance. However, within 10% of the fiscal expenditure responsibility, the control gained by government equity participation intervenes in the PPP project operation and management process in the form of resource allocation, price control, or performance assessment, which can effectively improve the efficiency of team members’ interaction and collaboration, reduce the complexity of the game, and reduce the coordination cost, thus enhancing the project success guarantee and cooperation performance level.

Based on the theory of cooperation, competition, and resource dependence, this study carries out the influence mechanism of team performance in PPP projects from the perspective of the interdependence of cooperative target teams. Most previous studies have focused on the relationship between goal interdependence, goal setting or goal orientation, and performance in the field of human resource management at the organizational level and have explained the inducing factors, acting relationships, and potential consequences of goal interdependence among individuals in an organization based on the theory of cooperation and competition. General corporate team goal interdependence usually refers to the goal dependence problem between employees from within the same organization or between leaders and employees. In contrast, PPP project team goal interdependence is a goal dependence problem between team members formed by two organizations with different attributes (public and for-profit). In PPP project practice, project teams jointly formed by government and social capital subjects inevitably face several decision-making dilemmas of goal dependence or goal conflict. This study, to guide the PPP project team to pay attention to and maintain the goal dependence of teamwork, suggests that the project team should take the initiative to analyze the credibility of the goals, resources, and commitments of the main body in each stage of the project, to continually strengthen the enhancement of the project team’s dependence and cooperation performance, as well as the sustainability of the PPP project.

Since this paper uses data collected from a questionnaire survey, the research in this paper has the following shortcomings. This paper studies the relationship between the interdependence of cooperation goals in PPP project teams on team performance, which belongs to team-level research. Although the data questionnaire survey involves all parts of the country, the data are relatively thin, and the sample size is not large enough. In the late stage of the team, the survey can only carry out character pair processing, social capital side, and the government side of the same team to survey at the same time. In addition, the influence of cooperative goal interdependence on team performance is also affected by many factors, such as differences in the ability of team members, etc. In the future, under the condition of having a large sample, other factors will be considered to conduct a study on cooperative goal interdependence on team performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S. and H.Z.; methodology, H.Z.; software, H.Z.; validation, S.S., H.Z. and F.Z.; formal analysis, H.Z. and S.S.; investigation, H.Z.; resources, S.S. and X.Y.; data curation, H.Z., F.Z. and H.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Z., S.S. and F.Z.; writing—review and editing, S.S., X.Y. and H.Z.; visualization, S.S.; supervision, S.S.; project administration, S.S. and X.Y.; funding acquisition, S.S. and X.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Annual Project of Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning of Henan Province (2022BZH004) in 2022, the Postdoctoral Research Project of Henan Province (2021-281) in 2021, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Universities of Henan Province in 2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gong, J.; Lu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Fu, J. Fiscal Pressure and Public–Private Partnership Investment: Based on Evidence from Prefecture-Level Cities in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei-Kyei, R.; Tam, V.W.Y.; Komac, U.; Ampratwum, G. Review of the Relationship Management Strategies for Building Flood Disaster Resilience through Public–Private Partnership. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojewnik-Filipkowska, A.; Węgrzyn, J. Understanding of Public–Private Partnership Stakeholders as a Condition of Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Zhu, D.J. Theory and practice of sustainable development-oriented PPP model. J. Tongji Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2017, 28, 78–84+103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Yin, C.Q. How ESG concepts empower PPP performance management: Realistic dilemmas and coping strategies. Constr. Econ. 2022, 43, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, F.R.; Zeng, T.H.; Shao, H. Simulation study on the system dynamics of sustainability risk of pipeline corridor PPP project. Financ. Account. Mon. 2020, 16, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppenjan, J.F.M.; Enserink, B. Public-Private Parnerships in Urban lnfrastructures: Reconiling rivate Sector Partcipation and Sustainability. Public Adm. Rev. 2009, 69, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, J.E.; Hollenbeck, J.R.; Knippenberg, D.; Ilgen, D.R. A century of work teams in the Journal of Applied Psychology. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 452–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. Formation and influencing mechanisms of teamwork remodeling. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 28, 390–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Pennec, M.; Raufflet, E. Value Creation in Inter-Organizational Collaboration: An Empirical Study. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 148, 817–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, L.; Wu, J.; Wang, S. Factors Affecting Local Governments’ Public–Private Partnership Adoption in Urban China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaraswamy, M.M.; Anvuur, A.M. Selecting sustainable teams for PPP projects. Build. Environ. 2008, 43, 999–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Ding, X. A histological study of PPP project failures—A clear set of qualitative comparative analysis based on 30 cases. Public Adm. Rev. 2019, 12, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.A.; He, Q.H.; Yang, D.L. Research on the mechanism of occurrence of investors’ synergistic behavior and its evolutionary law in PPP projects. Oper. Res. Manag. 2019, 28, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.X.; Zhu, F.W. A study on the conflict of public-private system logic and the cooperative behavior of social capital in PPP projects. Nankai Manag. Rev. 2021, 1, 1–21. Available online: http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/12.1288.f.20210630.1535.004.html (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- Qian, T.; Yang, C. State-Owned Equity Participation and Corporations’ ESG Performance in China: The Mediating Role of Top Management Incentives. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivleniece, I.; Quelin, B.V. Creating and capturing value in public-private ties: A private actor’s perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2012, 37, 272–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warsen, R.; Klijn, E.H.; Koppenjan, J. Mix and Match: How Contractual and Relational Conditions Are Combined in Successful Public–Private Partnerships. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2019, 29, 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, B.; Zhou, D.; Zhao, J.; Yin, Y.; Li, X. Fuzzy Synthetic Evaluation of the Critical Success Factors for the Sustainability of Public Private Partnership Projects in China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Gan, T.; Wang, H.M. The logic of PPP project operation under the threshold of multiple subjects--a multi-case study based on infrastructure and public service projects. Public Adm. Rev. 2021, 5, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Wang, N.; Mu, W.; Zhang, L. The Instrumentality of Public-Private Partnerships for Achieving Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.J.; Wei, J.J.; Wang, L.; Xie, X.Y. How does wrongdoer status affect colleague tolerance?—The role of task goal deviation and team interdependence. Manag. World 2021, 37, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.S.; Loignon, A.C.; Woehr, D.J.; Loughry, M.L.; Ohland, M.W. Dyadic Viability in Project Teams: The Impact of Liking, Competence, and Task Interdependence. J. Bus. Psychol. 2020, 35, 573–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, G.; Jin, T.; Jeong, Y.; Lee, S.K. Evolution of Partnerships for Sustainable Development: The Case of P4G. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvato, C.; Reuer, J.J.; Battigalli, P. Cooperation across Disciplines: A Multilevel Perspective on Cooperative Behavior in Governing Interfirm Relations. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 960–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Hao, S.; Li, X. Project Sustainability and Public-Private Partnership: The Role of Government Relation Orientation and Project Governance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, M. A Theory of Co-operation and Competition. Hum. Relat. 1949, 2, 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjosvold, D.; Chen, N.; Huang, X.; Xu, D. Developing Cooperative Teams to Support Individual Performance and Well-Being in a Call Center in China. Group Decis. Negot. 2014, 23, 325–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.X. A Review of the Development and Contribution of Resource Dependence Theory. Gansu Soc. Sci. 2005, 1, 116–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G.R. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hans, V.H.; Joop, K. Building Public-Private Partnerships: Assessing and Managing Risks in Port Development. Public Manag. Rev. 2001, 4, 593–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Humphrey, S.E.; Gupta, A. Structural Interdependence Within Top Management Teams: A key moderator of upper echelons predictions. Strat. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrick, M.R.; Bradley, B.H.; Colbert, A.E. The moderating role of top management team interdependence: Implications for earl teams and working groups. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 544–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeChurch, L.A.; Mesmer-Magnus, J.R. The Cognitive Underpinnings of Effective Teamwork: A Meta-Analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 32–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Wang, W.; Gao, X.; Hu, M.; Jiang, H. Sustainable Operations: A Systematic Operational Performance Evaluation Framework for Public–Private Partnership Transportation Infrastructure Projects. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, S.K.; Elshaer, I.A.; Ghanem, M. Relational risk and public-private partnership performance: An institutional perspective. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quelin, B.V.; Cabral, S.; Lazzarini, S.; Kivleniece, I. The Private Scope in Public–Private Collaborations: An Institutional and Capability-Based Perspective. Organ. Sci. 2019, 30, 831–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, P.; Dicorato, S.L. Sustainable Development, Governance and Performance Measurement in Public Private Partnerships (PPPs): A Methodological Proposal. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krane, H.P.; Olsson, N.O.E.; Rolstadås, A. How Project Manager–Project Owner Interaction Can Work within and Influence Project Risk Management. Proj. Manag. J. 2012, 43, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.X.; Sun, M.X.; Zhu, F.W.; Chen, L. Team interaction behavior and project role identity: An action research. Nankai Manag. Rev. 2021, 24, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.N.; Ge, Y.H. Team processes and strategic decision performance in executive teams of start-up companies—The moderating role of cognition. J. Manag. Eng. 2021, 35, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, M.; Mathieu, J.; Zaccaro, S. A Temporally Based Framework and Taxonomy of Team Processes. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 356–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, J.; Matous, P. Testing the impact of targeted team building on project team communication using social network analysis. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, R.; Wohlgezogen, F.; Zhelyazkov, P. The two facets of collaboration: Cooperation and coordination in strategic alliances. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2012, 6, 531–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinel, W.; Utz, S.; Koning, L. The good, the bad and the ugly thing to do when sharing information: Revealing, concealing and lying depend on social motivation, distribution and importance of information. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2010, 113, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenia, S.; Dangelico, R.M.; Nonino, F.; Pompei, A. Sustainable Project Management: A Conceptualization-Oriented Review and a Framework Proposal for Future Studies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwig, A.; Clarke, S.; Johnson, S.; Willis, S. Workplace team resilience: A systematic review and conceptual development. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 10, 169–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjosvold, D.; Wong, A.; Chen, N. Constructively Managing Conflicts in Organizations. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 545–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Tjosvold, D. Servant leadership for team conflict management, co-ordination, and customer relationships. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2016, 56, 238–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamsal, M.; Dwidienawati, D.; Ichsan, M.; Syamil, A.; Trigunarsyah, B. Multi-Perspective Approach to Building Team Resilience in Project Management—A Case Study in Indonesia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, G.; Cui, Q.; Sang, L.; Wang, W.; Xia, D. Knowledge-Sharing Culture, Project-Team Interaction, and Knowledge-Sharing Performance among Project Members. J. Manag. Eng. 2018, 34, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.Z.; Hu, S.Q.; Zhang, L.J. Ruminations on the partnership model of PPP project based on incomplete contract. J. Southwest Pet. Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2021, 23, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.; Li, Y.; Li, H. Renegotiation Strategy of Public-Private Partnership Projects with Asymmetric Information—An Evolutionary Game Approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. Infrastructure Public–Private Partnership (PPP) Investment and Government Fiscal Expenditure on Science and Technology from the Perspective of Sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.L.; Hu, Y.Y. Functional alienation, root causes and solutions of PPP model in China. J. Shanghai Univ. Financ. Econ. 2020, 22, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.F.; Yun, F.; Huang, J.H.; Lian, Y.J. A study on the impact of state-owned capital participation on the investment efficiency of non-state-owned enterprises. Economist 2021, 3, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wu, J.; Wu, Y.H. Why government-social capital cooperation (PPP) is easy to contract and hard to land--an analysis based on southwest region. Financ. Econ. Sci. 2021, 6, 118–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.J.; Wu, W.X.; Xu, J. The impact of promotion incentive mechanism on government and social capital cooperation projects. China Soft Sci. 2020, 3, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.H. The U-shaped curve of the impact of state equity on the performance of listed companies and the two-handed theory of government shareholders. Econ. Res. 2005, 10, 48–58. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=VtEo6IuKaTCYKB61uTRzKnLMIwTIXCCrT6LewrBi5oP-Qv0nwglthb-HvfVMg53ZjbSMmiT6I39TuNjwEwHdbUg_fbKxg4gJ5f9pEi2UUqTUoIwtFGW3Qu6GGlnwmir7&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Cui, W.J.; Sun, C.; Chen, G. Distance produces beauty? The impact of government-business relationship on corporate integration and innovation. Sci. Technol. Manag. 2021, 42, 81–101. [Google Scholar]

- Rangan, S.; Samii, R.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. Constructive Partnerships: When Alliances between Private Firms and Public Actors Can Enable Creative Strategies. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 738–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Wang, L. The relationship between government shareholding, trust and performance in PPP projects. Constr. Econ. 2019, 40, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Ma, Y.R. Risks of government shareholding in PPP projects: The reform experience and insights of the third sector in Japan. Mod. Jpn. Econ. 2020, 1, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtright, S.H.; Thurgood, G.R.; Stewart, G.L.; Pierotti, A.J. Structural Interdependence in Teams: An Integrative Framework and Meta-Analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 1825–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Wang, E.P. Interdependence and teamwork. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 2007, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.N.; Hao, S.Y.; Ren, X. The influence of leadership goal orientation on team performance in project situations. Soft Sci. 2020, 34, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.C.; Ye, Y.P.; Xu, M.D.; Zhu, G.L. “Two lovers love each other” or “right for each other”: The matching of industry-university-research partners and the mechanism of its influence on knowledge sharing and cooperation performance. Nankai Manag. Rev. 2018, 21, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlow, S.L.; Lacerenza, C.N.; Paoletti, J.; Burke, C.S.; Salas, E. Does team communication represent a one-size-fits-all approach?: A meta-analysis of team communication and performance. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2018, 144, 145–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.L.; Liu, H.Y. Mediating and Moderating Effect Methods and Applications; Education Science Press: Beijing, China, 2020; pp. 128–135. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, B.N.; Jin, J. Mechanisms of public service provision on perceived performance of public services-mediating role of government image and moderating effect of public participation. Manag. World 2016, 10, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).