Abstract

In the town of Sacapulas located in the mountainous country of Guatemala, there is a constant risk of natural disasters. Floods and landslides occur frequently, resulting in the loss of human lives and cultural aspects. Specifically, in the region, the creation of black salt is the most affected. This resource has been created since the time of the Mayans on the salt beach surrounding the town. However, from the 1940s onwards, this industry has shrunk, impacting the sustainability of indigenous people. After conducting several area and space analyses, it was found that the black salt beach has evolved considerably since the last research conducted in 2001. The shape of the space has been reduced, while the use of the area has been modified by the people of the town, who specifically use the hot springs located below the river shore of the beach. This new usage can coexist with the Salt making industry is only made by a few people now, there are few working in this industry, and they only work in the dry season. The result is an opportunity for economic growth and an increase in tourism if the area handled properly by managing the land and planning ahead.

1. Introduction

In recent years, there has been an increase in research related to culture and its inclusion in sustainable development [1,2,3]. Sustainable development is defined as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” [4], whose implementation is based on three important pillars: social, environmental, and economical. [1,2]. This effort has been developed over the last few years with joint efforts such as the Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction, a seminal document that seeks to reduce the impact of disasters in terms of loss of life and livelihoods over the next 15 years from its conception [5]. Specifically, emergencies and incidents can escalate into what is known as a disaster if there is no appropriate management method that can effectively resolve the problem. According to the United Nations, disasters can occur anywhere in the world and can last for short to extremely long periods of time. Depending on the affected society, the use of its resources may be limited and result in the need for external assistance to solve it [6]. This is specifically true if the affected communities are located in highly vulnerability areas, where local customs and cultural heritage are more predominant.

Research regarding culture heritage being threatened by climate change has been extensive since 2003 [7,8], and many advancements have been made so far. Specifically, it is understood that climate change can affect culture both in its tangible [9] and intangible forms [10,11]. One response to counteract this issue has been the different approaches to climate change and cultural heritage by implementing a diverse set of tools, using interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary, or transdisciplinary approaches [12]. A good example is the US National Park Service (NPS), based on a four-pillar approach: science, mitigation, adaptation, and communication [13]. Meanwhile, in developing countries, programs such as UNESCO Local and Indigenous Knowledge Systems (LINKSs) present means to implement intangible cultural heritage (ICH) into disaster management processes. These pockets of knowledge are found in many cultures across the globe and give invaluable insight on the adaptability of a society towards climate change and potential disasters. While ICH is a term rarely used in the Disaster Risk Reduction and Management literature, the proxy terminology “Indigenous knowledge systems and practices” (IKSPs) is more common [9,14]. LINKS has proven to be effective in the implementation of local knowledge with science and environmental policy processes [14].

This international effort has not been fully evidenced in the Latin American country of Guatemala, where the erosion of authority figures results in longer, slower decision making, along with insufficient risk reduction programs [15,16,17]. Guatemala does include disaster risk governance in its legislation, which is included in the legislative decree 109-96 called “Law on the National Coordinator for Disaster Reduction”. Enacted in 1996, it put Guatemala as one of the countries with laws adjusted to the era [18]. This law was based on the Yokohama Strategy and Framework for Action, which gives priority attention to developing countries [19].

Currently, disasters of great magnitude in Guatemala are normally addressed with foreign cooperation such as USAID [20]. Yet, the international help does not reach smaller and less known Mayan communities such as the town of Sacapulas. The town of Sacapulas is a small town located in the Cuchumatanes mountain range in Guatemala. To the north of the village is the Chixoy River, which flows to the south of Mexico. The importance of this town is due to black salt. This product is the result of more than a thousand years of uninterrupted tradition by the Sacapultecos, a Mayan group with roots in the land. The influence of this product has been so great that the black salt industry has been a key part of the Mayan history of the native people of Guatemala. To create black salt, it is necessary to use an area called “Black Salt Beach”, located north of the village where the Chixoy River flows. This is a Mayan village that has historically used natural resources to maintain both economic and environmental sustainability. Sadly, due to climate change, industry and local culture are being threatened by constant floods produced by the Chixoy River. It is known that Mayan society has been always vulnerable towards natural disasters [21,22,23]. Yet, in the last years, the region has experienced an increase in natural disasters [24]. According to the World Risk Report of 2022, Guatemala is found to be 45th on vulnerability, presenting high risk against natural disasters and a high lack of adaptive capabilities [25].

The vulnerability presented in the town of Sacapulas is linked to the Chixoy River and its constant floods over the beach and town. As a consequence, the industry has shrunk. Moreover, without effective architectural planning at hand, the city’s growth has been haphazard. Furthermore, leadership has neglected the space, which results in its constant loss. Previously, most of the Sacapulas town created the salt; nowadays, only four people, who are in an advanced stage of life, are working. Without a space to create this product, there is a major concern for the total loss of Mayan culture that has been developed for over a thousand years (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Black salt product (Source: Author).

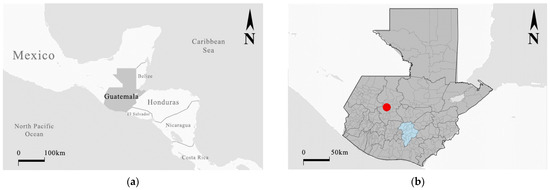

Guatemala is a country in Central America bordered by Mexico to the north; Belize and the Caribbean Sea to the northeast; Honduras to the east; El Salvador to the southeast; and the Pacific Ocean to the south. The country is mountainous in character due to the “Sierra de Los Cuchumatanes”: a mountain range throughout Central America. This results in variations in topographical elevation between 500 m and 3800 m. As a result, several towns and cities are located all across this terrain variation. Although the capital of the country is home to a variety of cultures and races, the interior of the country presents a diversity of mostly indigenous Mayan villages. Most of them live in mountainous, remote areas.

As for natural disasters, hurricanes, earthquakes, and volcanic eruptions are common due to the country’s location (Middle Caribbean and Pacific, where three tectonic plates meet). However, lately, floods and landslides have become quite common compared to other years, resulting in the loss of lives and homes (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(a) Geographical location of Guatemala. (b) Research area, in red. Capital of Guatemala in blue. (Source: Author).

1.1. Research Area

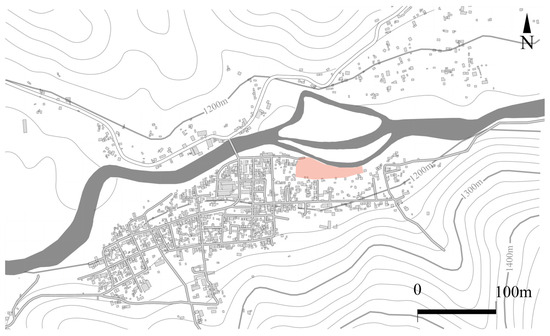

Within the Sierra de los Cuchumatanes, the town of Sacapulas is located in the area of analysis. This town has 55,398 thousand inhabitants according to a census conducted in 2018 by the National Statistic Institute (INE in Spanish) [26]. Historically, the area has presented great importance in pre-Columbian times. Prior to the Spanish conquest, the town of Sacapulas was considered an important economic point for nearby empires. This is due to the fact that black salt, a historical Mayan product, was created in the area. Black salt is the result of the cooking water impregnated with salt, which is harvested by utilizing specific soil that only the salt-maker families own. This soil is then cultivated on the beach to be impregnated with salt during the summer period (November to June). Thanks to the importance of this product, the black salt industry was born and maintained over the years by the efforts of families dedicated to the product. The economic sustainability as well as the surrounding nature are closely maintained by the black salt (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Sacapulas Town in the south of the Chixoy River, with the salt beach in red.

This industry requires two important elements for the creation of the product: the architecture used for cooking the salt and the physical space where the salt is “cultivated”, called the “salt beach”. Specifically, the beach space has been constantly mentioned in Spanish chronicles [27,28] and Mayan oral tradition [29]. The process is carried out initially on the beach, then continues in the salt kitchens. These structures are located south of the beach and consist of a space defined by four walls with a gabled roof of Spanish tile. In front of the salt kitchen is a wooden box elevated from the ground called a “petaquilla”, which serves to filter the salt from the soil. In the center of the kitchen is the “heart of the fire”, or the space where the fire is started to cook salted water. The result of this process are two: white salt called Atzam; or, if the cooking process is continued, black salt called Xuupej.

There are several uses for black salt; according to reports, this has not changed over the years. A report in the area conducted by Ruben E. Reyna and John Monaghan for the EXPEDITION magazine was produced in 1978 (published in the 1981 issue of the magazine) [30]. In their report, two main uses are mentioned; these uses were also mentioned by research conducted in the area in 2001 for the magazine “Guatemalan Traditions” (Tradiciones de Guatemala, in Spanish) published by Amilcar Ordoñez Chocano on the 2005 issue [31]. He mentions the same uses as Reyna and Monaghan, but Ordoñez’s explanation is more detailed. The uses are the following:

- Human use: In the case of human use, it was identified that people use salt as a home remedy for different body ailments. Followed by medicinal use, edible use was also identified, specifically in food or beverages such as atol, a traditional cornstarch-based hot drink.

- Animal use: The use in animals is exclusive as a medicinal product, specifically as a deworming agent and remedy for various ailments in cattle.

For both human and animal use, there is no formal research that corroborates the effectiveness of salt as a remedy. This assumes that knowledge of its medicinal properties has been passed down through generations rather than research.

Prior to the conquest, salt was a product created in specific towns and highly valued for its scarcity, which increased the importance of the region. Therefore, there are several events that show the interest in controlling the salt of the region. Prior to the Spanish conquest, the reign of Sacapulas, Quiche, was conquered Sacapulas in the 14th century with the objective of controlling the salt [32]. Although salt has an important value as a product, there is a connection with the Mayan religion and cosmovision of Sacapulas. Its value is such that the mention of the creation of the town and salt as a gift from the gods is found in the Mayan oral recollection “Titulos de los señores de Sacapulas” (Title of the Sacapulas Lords in Spanish) [29]. This results in a mostly religious value, where the beach and the black salt are considered as a gift from the ancestral father “Conejo de Fuego” (understood as a god). Black salt was also prominent in trade during old times, and there are traces of its exchange according to Andrews. Paid as a tribute, the area of Huehuetenango (west of Sacapulas) paid tribute to the conquerors in the form of Sacapulas salt. It is in this period that the product becomes an economic source for the people of Sacapulas. Specifically, the area of Sacapulas lacked agricultural lands, which probably made Sacapulas rely on the trade to acquire additional corn [32]. However, the importance of the beach was secondary, and the existing commercial routes became important for the Spaniards. By introducing an economic value to the salt, the dynamics of the product and the space of the beach changed. This has been maintained during the last years, although its production has been extremely reduced due to several external factors.

Within the black salt industry, specific methods have been created to handle characteristics of the beach. An example of this is the way of delimiting the areas of each of the owners. This was always by irregular means, using pointed stones as boundaries and dividing the space in a more or less regular way. This also creates a unit of measurement to be able to order the spaces that is specific to the salt beach commonly known only to the people of the village: the petaquilla. As mentioned above, the petaquilla is an element used in the creation of black salt. It consists of a wooden box of 1.30 m × 1.30 m × 0.52 m, elevated about 1 m from the ground. The function of this box is to act as a filter in the process of creating black salt. Its volume is about 0.88 m2. Therefore, each person who has ownership of a space of the beach maintains it by means of “petaquillas”, referred to by the people as well as legal documents of internal transactions found in the development of this research.

1.2. Current Issues

However, the salt beach has suffered constant modifications due to the affluence of the Chixoy River; since colonial times, there has been mentions of its growth. There are no visual documents or plans that show the original size of the beach. However, there are mentions of the space. The earliest ones in relation to the dimensions of the beach were reported by the Spanish chronicler Martin Alfonso Tovilla in his report to the Spanish crown called “Hystorias Dyscriptivas” in 1629. The importance of this document lies in the mention of the size of the area at this time, where he mentions that “a mean of half four leagues of length and two stone tosses of width” [28] p. 139. Due to the old Spanish used, several interpretations of the total size can be given:

- “Legua” in the context of New Spain refers to the unit of measurement used by the Spaniards in the colony. There were two: the legal Castilian legua used to establish the dimensions of the land; and the common legua used in the chronicles of the explorations and land travels. The nature of this measurement makes measuring distances very imprecise because it depends on the situation of the chronicler and the value given to it. It was established during the 16th century at 20,000 Castilian feet, 5.5 km, or 6666.66 Castilian varas [33].

- “Tiro de Piedra” (Stone toss) is a phrase that refers to a short distance in the Spanish language. It usually ranges between 40 mts and 50 mts of distance.

Due to the Spanish language and the antiquity of this chronicle, there can be many interpretations of the text. It is not known whether it refers to half a quarter of a “legua” (an eighth of legua), half of four leguas (two leguas), or four leguas (the definition of “half” is omitted). This results in a general misunderstanding about the actual size of the area. However, due to the significant differences between sizes, it likely refers to an eighth of a legua because the territory would remain within the vicinity of Sacapulas. Meanwhile, the width of the area would be between 80 and 100 m by using two stone tosses (Table 1).

Table 1.

Interpretations of the Spanish text.

1.3. Floods and Natural Hazards

The earliest mention of risk within the area is by the chronicler Francisco Antonio de Fuentes y Guzman in the chronicle “Recordacion de Florida” in 1690. He mentions that a Christian convent near the area maintained a bridge which was damaged by flooding from the river. However, it also mentions that it was still standing [27]. There is no other mention of any other important event during the colonial and republican period in Guatemala (1825 onwards). The next mentions about floods are found in the report made by Reina and Monaghan in the village of Sacapulas in 1981; research made by Anthony P. Andrews in 1983 about salt in Mayan villages; and finally, research made by Ordoñez Chocano in 2005. Andrews mentions a flood that occurred in 1949 where the Chixoy River submerged 60% of the usable space, leaving 2 hectares of usable land. Andrews makes no mention of the specific location of this land; however, a subsequent investigation by Ordoñez Chocano in 2001 corroborates the information. There is a mention related to the subject by Reina and Monaghan in 1981, where informants share that people were disinterested in continuing to produce black salt because of the underground space that has yet to be recovered. Finally, during the 2000s, there were constant landslides reported near the river. Storm Stan aggravated the situation in 2005, as well as Hurricane Agatha in 2010.

Not all of the events affecting the area have been climatic. Several actions by various human actors have resulted in the loss of industry and, consequently, the loss of interest in Mayan traditions. Andrews mentions the introduction of coastal salt in 1940 in the region as a loss of the salt market. Also, Ordoñez mentions the expansion of a bridge near the village in 1996 in his research. To build it, an alternate water channel was created to reduce the flow of the Chixoy River, but it was never refilled once its use was completed. This slowly impacted the area due to the consequent excessive flow.

In all cases, there is a constant problem: the lack of photographic material as well as plans of the area that identify the constant modifications that the space has suffered. Therefore, there is no evidence beyond the mentions and the collective memory of the people. However, this tends to be lost due to the fact that the older population is the only one that recounts the events, as well as the extension of the original area. The objective of previous research is to document the process of creation of the black salt. However, they do not emphasize information related to the beach area. This also generates problems due to the lack of interest in research within the area due to their difficulty of access as well as lack of knowledge of the local culture. The last formal research was carried out in 2001 by Ordoñez: The last research was done 22 years ago, which reported that there has been changes in the space and, as a consequence, less people dedicated to the black salt (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Current state of the salt beach.

2. Materials and Methods

According to Sandra Fatoric, an increase in research related to cultural heritage and the risk of its loss due to disasters has increased considerably. However, most of these efforts happen to be in European countries, resulting in a great need for research advancement in less developed countries [7]. This research seeks to address this lack of research. Specifically, this paper seeks to determine what damage the black salt beach has suffered due to the constant flooding caused by the Chixoy River. The questions that this research is based on are the following:

- What are the causes, beyond the natural ones, that result in the space is being lost?

- What have been the actual modifications that the area of the black salt has undergone?

- What are the areas most at risk of being lost considering the current situation?

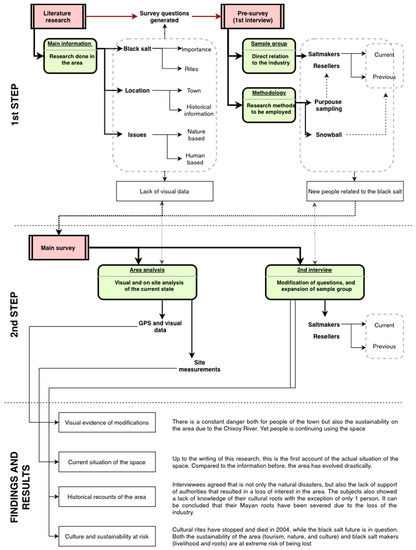

To achieve this research goal, the use of a scientific method where interviewees’ perspectives, attitudes, and opinions were needed. Consequently, a qualitative approach may result in important information needed for an in-depth analysis of Sacapulas, considering that the basic information on the situation could be more precise. Therefore, the main methodology employed in this research is based on modified ground theory. The use of ground theory and its most popular derivations, such as Strauss and Corbin, results in the need for the researcher to have no prior knowledge of the situation to be investigated to result in a theory emerging from unbiased data. This is inadmissible in this research due to the delicacy of the situation and the context. It is of extreme importance to understand the cultural value of the space. Therefore, a flexible method is necessary to admit a prior research problem: in this case, the reinterpretation of the cultural space at risk [34].

Due to the lack of information of the area, it was also needed to integrate quantitative methods into the research. These methods range from visual analysis to historical analysis and serve a specific purpose: the completion of information that, due to various factors, interviews cannot obtain. In order to be able to link the quantitative methods with the data obtained by the qualitative method, methodological triangulation was employed, specifically “between-method triangulation.” This method is proper when one chooses to analyze the same phenomenon (loss of black salt space value) from different angles [35]. Due to the age of members from the black salt industry, there is a possibility that much data may need to be supported by external information. The results are twofold: the first is a deeper understanding of the information gathered. Second, bias that may result from the perspectives of each of the interviewees is eliminated. Methodologies where qualitative and quantitative data are used to understand a phenomenon have already proved successful in the region [14]. The methodology implementation was divided into three steps: research background, primary survey, and results. Research background consists of research and compilation of all existing data by previous researchers as well as local authorities. This creates an understanding of the gaps and needs that the site maintains. All this has been discussed in Section 1.

For qualitative information, it was needed to involve the last salt-makers into the investigation process due to them having most of the information. An on-site survey was made to understand the actual situation and to interact with the people that know the previous situation of the beach. This took place on two occasions: March to April 2022, and September 2022. The survey focused specifically on people with a direct relation to black salt and the industry (salt-makers, salt-maker families, and traders).

For quantitative information, a digital medium of photographic evidence was used. This photographic evidence comes in the form of satellite images produced by the “livingAtlas Arcgis”. Due to the remoteness of the site, there is no satellite information older than 6 February 2011, but several changes in the space were identified. The results are elaborated in Section 3.5. To compare the evolution of the situation, a site visit was conducted with the objective of manually measuring the current space. The results are elaborated in Section 3.6 and Section 4.

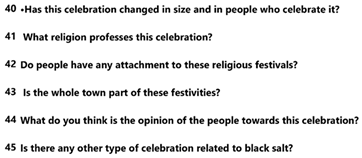

The results of this research suggest answers to the primary questions mentioned in the objectives. The results are elaborated in Section 3 and discussed in Section 4 of this paper. The methodology used in this paper is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Methodology diagram.

2.1. Limits

Due to the location of the site, research on the black salt and its creation area has yet to be performed, which has made it difficult to access recent information. As a result, the available materials on the subject are extremely scarce, generating limits in the scope of the research. Due to this reason, several limits had to be taken in account to maintain a focus in the research objectives:

- This research will not focus on people outside the black salt industry. Due to the nature of the work, salt workers are people who come from families dedicated exclusively to this industry. Meanwhile, salt traders have worked hand in hand with the salt-makers, resulting in a cooperation that was fruitful through the years. This results in a sample group directly in contact with the industry as a whole.

- The research will focus on the black salt space and not on architectural spatial elements resulting from the black salt culture and industry. While mentioned due to the need of context, it is not the goal of this research to focus on the specific aspects of the black salt architecture.

- There is a possibility that a certain part of the black salt beach is located below the Chixoy River. However, no data were taken on the thickness, depth, and characteristics of the terrain where the Chixoy River flows.

- Satellite data will be limited to satellite images of the Sacapulas beach area and will only be considered when there is a significant change in the shape of the river.

- The efforts of this research will not focus on the use of the space by people who do not have a direct relationship with the black salt.

- The area of the beach of the privatized located next to the public area is not taken into account. This is because the focus of this research is on the area that is available for anyone.

2.2. Materials Overview

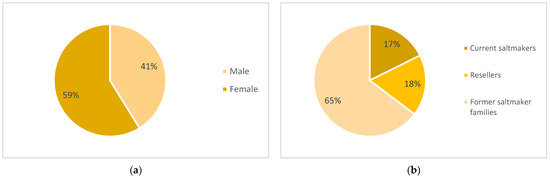

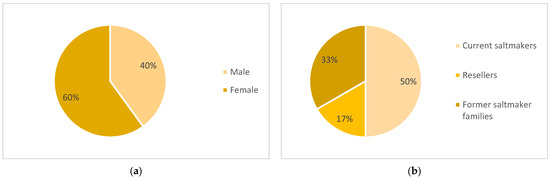

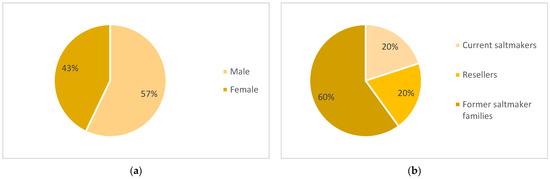

The total sampling performed in this study consists of 17 people who maintain or had a direct relationship with the black salt industry. In total, the sampling division by gender was of 7 men and 10 women. Due to the decline of the industry, the number of respondents is extremely small. However, it constitutes the majority of living persons who have maintained a relationship with black salt. Due to the approach of snowballing research, it is known that there are at least two more people with a direct relationship to the black salt industry. However, it was impossible to contact them due to their lack of interest in being part of this research. Meanwhile, the relationship of the individuals with the black salt can be divided into three categories: three current salt-makers, three resellers that previously worked in the black salt, and 11 members of former salt-making families.

Because two surveys were conducted, the number of subjects per survey is different. In the initial survey, only two men and three women were contacted. Thanks to the snowballing method, this group was expanded in the second survey. Both PSS-C and PSS-D participated in both surveys, so they are also presented in the second sampling group. In this case, their referral name changed to MSS-A and MSS-B, respectively. Regarding the type of relation towards the black salt industry, in the case of the first survey, it is divided into one ex-salt-maker from a salt family and his wife (two persons in total), one reseller, and two salt-makers.

In the second survey, the division of the group by gender is as follows: eight men and six women. The types of relation are as follows: three current salt-makers, nine individuals from salt families, and three resellers. All respondents currently reside in the town of Sacapulas, except for one person who lives in the outskirts of the area (MSS-N). A summary of the people interviewed during the pre- and main survey is found in Table 2 and Table 3. In order to maintain the privacy of the survey respondents, it was chosen to use subject referral names. Pre-survey subject (PSS) is used for the first 4 persons, and “main survey subject” (MSS) is used for the next 14 persons (Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8).

Table 2.

Information on the respondents to the first survey.

Table 3.

Information on the respondents to the second survey.

Figure 6.

(a) Pie diagram of the total percentage of respondents. (b) Pie diagram of the relationship of the respondents towards the black salt industry.

Figure 7.

(a) Pie diagram of the total percentage of respondents on the first survey. (b) Pie diagram of the relationship of the respondents towards the black salt industry on the first survey.

Figure 8.

(a) Pie diagram of the total percentage of respondents on the second survey. (b) Pie diagram of the relationship of the respondents towards the black salt industry on the second survey.

2.2.1. Survey Methodology

Due to the lack of research related to the project, there is constant difficulty in engaging in discussions with people related to the salt beach. In addition, the ages of the interviewees are advanced. Therefore, it was decided to conduct the surveys in a semi-open-ended manner as opposed to direct questions. In this way, it is possible to probe as much as possible into the information that the interviewees can offer. The surveys were also conducted using the purpose sampling methodology because the people interested in the research are the group that has worked on black salt. Following this, the snowballing method was used to identify other people involved with black salt in order to proceed to the second interview. The questions used for data collection focused on corroborating the data obtained from the literature review. According to Johanson and Brooks [36], most research only requires a specific sample group size for ground theory if theoretical saturation has been reached. In the case of this research, this point is reached if the information regarding people involved with black salt, their lands, and modification in current use is repeated by the correspondents. The origin of questions was based on concepts derived from the literature research available at the time of the pilot survey. According to the literature review, there are five essential points on which had information had to be obtained:

- Relationship of the person with black salt;

- Black salt industry;

- Other people who are related to black salt;

- Black salt beaches;

- Cultural expressions and black salt.

Therefore, the group of questions considered the central ones of this research are described as the following:

- General questions about the black salt industry which would confirm or deny the previously documented data. In addition, they will demonstrate an evolution in the status of black salt as a cultural product since the last research (2005).

- Questions about the space considered as the “salt beach” which determine the most critical factors affecting the area, the architecture created for the black salt, its perceived value, and future risks.

- Questions related to religious expressions and rites related to black salt. Due to the close relationship between the people of Sacapulas and black salt, this research is interested in knowing if they still know their roots.

Each set of questions contains background questions that facilitate the beginning of the interview and confirm whether the subject has some knowledge. The first set of questions does not relate to the spatial aspects of the area and focuses on the history of black salt. However, its use was necessary to understand the context in which it takes place and establish a knowledge base between the interviewee and the interviewer. The second group of questions was asked to deepen and investigate the topic depending on the data obtained. Once the type of relationship that the interviewee has with the salt mines is established, the questions most pertinent to the subject are asked. Although this group of questions is essential, several of the people to be interviewed are currently of an advanced age. Therefore, the interviewer chooses to adapt the approach and reformulate each question’s crucial aspects so that it is understandable to the interviewee. The third group of questions seeks to understand the extent of the influence of the salt beaches based on their cultural aspects. Taking into account that the existence of the beach has been connected to the town’s development, it is necessary to define how the town has developed in the function of the products that the beach has provided to the people. The specific results for this research are based on the questions related to the spatial aspects of the beach. The survey tool is presented in Appendix A.

To tabulate the data, it was chosen to micro-analyze the interviews by dividing each part where a specific topic is found. Then, the result parts were organized in groups in order to understand the relationship that exists in each line of information. For this purpose, all interview responses were transcribed verbatim. Then, each of the responses was analyzed to find similar patterns. This results in clusters that relate to similar concepts. Initially, 11 different clusters of concepts which appeared during the interviews were created. However, these were reduced to nine since they were too similar in nature, simplifying the development of the microanalysis. For each of these concepts, “worksheets” were created following the same structure used by Kambaru [37]. Each worksheet consists of the concept, definition, interviewee, quote, and time of said quote. An example of the microanalysis tool can be found in Appendix B.

2.2.2. Satellite Analysis Methodology

Regarding the use of imagery data, based on the information recapitulated in Section 1.3, it was chosen to use to the earliest imagery data available. It was decided to use the data system of the WorldImageryMap project to access visual information available by GPS. Unfortunately, due to the area’s remote location, the oldest information for the region is from 6 February 2011, while the most recent information is from 31 March 2021. Another territorial tool was developed locally by the local disaster reduction organism, CONRED (“National Coordinator for Disaster Reduction” in spanish). It consists of regional maps identifying the areas with the highest risk of natural disasters. The prediction of this threat uses the TerraView 4.2.2 methodology and its plugin TerraHydro [38].

2.2.3. In-Site Analysis Methodology

To determine the evolution of the space and to define its current state, the space was measured by a site visit conducted in September 2022. The onsite survey took 2 days to develop the specific planimetry of the beach space. This information was taken by two people (the researcher and his assistant) and focuses specifically on the beach area and its immediate surroundings. Both terrain and elevation data were taken for the space, and the southern area where the salt kitchens are located was studied. Up to this moment, this is the only existing document of the planimetry of the beach, division of the space, and current situation. This information was supported by the use of satellite maps based on Google Earth to determine areas where access was impossible due to the type of terrain, specifically the areas along the Chixoy River which are extremely dangerous. The expected margin of error is 1.8 m, according to previous studies [39]. For the elevation data collection, it was performed manually on-site.

3. Results

3.1. Original Beach Area

Within the interviews, respondents were asked about their knowledge of the black salt area. PSS-A1,2 mentions the existence of the beach from the current site to the area where there is a pit (area D in Figure 9). He also mentions that the current area was defined by a mango tree, which was found during the site visit. Meanwhile, MSS-D mentions the dimensions that the beach originally extended to the entrance of the village, where there is now a bridge. This assumes a distance of 206.20 m across the shore of the beach to the west, which is now lost. This was reiterated by MSS-H, who mentions the existence of a cavern with hot water located in this space. The cavern is only used during the dry season, when the flow of the Chixoy River is low. At the time of development of this research, it could not be accessed. This cavern is used by the people as a hot space area and is an attraction to tourists from nearby villages. When micro-analyzing the interviews, three themes were found to be constantly mentioned by the interviewees. These three themes are consequences of various factors that impact the black salt beach. As a result of the space, the black salt industry and the salt workers are negatively affected.

Figure 9.

Black salt beach and the 4 main points that present modifications due to river Chixoy. Areas “A” to “D” where the focus of this analysis due to the constant changes presented. Area “A” is the west road connecting to the current salt beach, area “B”. Meanwhile, area “C” is the space which Ordoñez Chocano mentions as previous salt beach area. This is corroborated by area “D”, where a road that connects to nowhere is located. This area currently is in ruins, and the state of the road close to the river Chixoy is extremely deplorable. [Esri historical map location of the salt beach area, inside Sacapulas’ town. Modified by author]. Retrieved from https://livingatlas.arcgis.com/wayback accessed on 2 January 2023.

3.2. Lost Space

The people interviewed agreed on natural disasters as the primary cause of lost space; however, several events were mentioned that were not previously documented by any media. The natural disasters that have affected the area have been on five occasions according to research in the area: the late 1930s, 1949, and 1964. In the period from 2010 to 2021, there have been floods documented by local newspapers [40,41,42]. However, interviews documented three other major events that occurred in 1951, 1976, and 1998. It can be observed that the area is constantly hit by natural disasters; however, it is not the type of disaster but the magnitude thereof that modifies the area. MSS-A mentions that in 1951, a flood which threatened the welfare of the people occurred. Meanwhile, in 1976, an earthquake which undermined part of the beach area occurred, destroying the infrastructure of the town of Sacapulas. Specifically, the kitchens used for the creation of black salt were mostly destroyed due to their rudimentary construction. It was identified that there are three kitchens still standing that were used by the salt-makers during the dry season. However, the actual location of the previous kitchens and its number are beyond the scope of this research.

Following this, according to MSS-C, in 1998, Hurricane Mitch affected the town with constant torrents of water that increased the flow of the river affecting the beach area. All this was worsened at the beginning of the 21st century with storm Stan in 2005 and hurricane Agatha in 2010. Both not only reduced the remaining beach space, but also threatened the lives of the people of Sacapulas due to the subsidence caused by the Chixoy River. As mentioned above, there is no documentation in the form of photographs or plans that verify the original size of the space. However, all interviewees conclude that each of the natural disasters that have occurred have in some way reduced either the interest in black salt or the space utilized. During this research, it was expected that the area of the beach would be quite extensive. Yet, when it was accessed, it was found that the majority of the space is buried and effectively lost. Due to the missing visual information, there is no way to understand the development and modifications of the area to make a comparative analysis. Though, it is understood that the space is perceived less as a “beach” and more as a “unused land” by the townspeople. This is mainly due to most of the area being used as cattle growing space. At the moment of this writing, there is only one active space belonging to MSS-A; this is due to its location being relatively far from the Chixoy River (35 m). According to the interviewee, it took 4 years to dig up part of the area and reactivate its use. The location and photographs of the area are attached in Section 3.6.

3.3. Ownership

As mentioned in Section 1.1, the use of the beach space is defined by the “petaquillas” that each owner has. As such, an owner is usually designated to have “X amount of petaquillas” instead of “X square meters”. However, due to flooding as well as the irregular nature of the definition of the spaces, the official delimitations have been lost. MSS-B mentions the lack of official ownership documents as an important cause of the loss of space. They also mention the disinterest of their sons to stay in the black salt industry. This is reiterated by both MSS-E, D, and F, daughters of salt farmers. However, MSS-B, D, and E mention that sons of other ex-salt-makers have legally and illegally taken over part of the beach to privatize it. This is due to the fact that the entire area of the beach has thermal waters when they open a hole in the ground. Because of its potential economic value as well as use, areas of the beach have slowly been privatized. This cannot be legally counteracted. MSS-B mentions that due to the lack of studies of the previous salt-makers, the necessary documents to define the owners were not prepared. As a result, at this moment, ownership of beach areas is in doubt. In addition, people have no interest in or doubt the effectiveness of legal methods to protect the public area.

3.4. Rites and Religion

The loss of space also affects people who are interested in being part of the black salt industry. As a consequence, sustainability within the area has been negatively impacted. One of the aspects that people interviewed mentioned is the loss of Mayan rites related to the black salt space. MSS-A1 mentions that in the past, there were festivities in which the grandparents were part of, bringing together young people and people from the village in their celebration. This celebration was mentioned by Monaghan and Reyna previously, and in the document, there are photos of several people attending this event. However, between the period from 1978 and the writing of this research, there has been no photographic data or research mentioning the event. MSS-C mentions that, with the death of MSS-E and D’s father, the celebration is effectively dead, and there are no documents specifying the steps to hold the event. The last celebration of the event was in 2002 according to MSS-A, where only three people attended. Upon further inquiry with the interviewees, the type of information is fragmented due to their age, so only fragments of what happened on that day were documented.

The black salt is also related to the history and founding of the town according to the literature research previously conducted. However, when asked about the knowledge of the Mayan ties that link the town of Sacapulas with the black salt, only one of them said to have knowledge about them. In the same way, this person partially described the creation myth which appears in the Mayan chronicle “Titulo de los señores de Sacapulas”, which certifies the veracity of his knowledge.

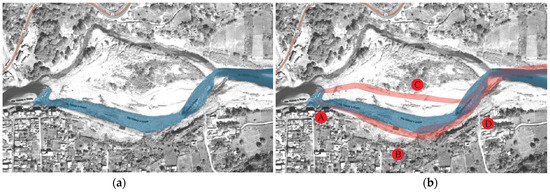

3.5. GPS Observations

In 2015, CONRED performed a risk analysis of the existing risk in the area. This report determined that the area near the river is under a constant threat of flooding. The images obtained by GPS together with the work done by CONRED determine not only a risk of flooding, but also constant changes in the flow of the Chixoy River [38]. Subsequently, the area of the black salt beach is the most affected because it is a public space without any significant construction. Considering the above, it is likely there has been a change since the last research performed in 2004. Using the “livingAtlas Arcgis” system, five different dates were identified on which there was a significant change in the area due to flow increases of the Chixoy River. The photographs showing the changes are as follows: 6 February 2011; 11 July 2012; 26 April 2014; 26 November 2019; and 31 March 2021. Previous imaginary could not be found at the moment of writing.

By comparing the image data, four points were identified where there is a constant change due to the river flow. The northern area delimited in blue is what is called the “island” according to Ordoñez; of which, he comments “On the left bank of the Rio Negro or Chixoy, you can see the island, full of trees, under which the other half of the salt beach area is buried.” [27], p. 166 (Figure 10 and Figure 11).

Figure 10.

Comparison between the earliest image available, and the oldest: February 2011 (a) and November 2019 (b). Chixoy River flow in February 2011: blue. Chixoy River flow in November 2019: red. By focusing on the analysis areas “A” to “D”, it is evident that constant modifications have occurred during the past years. [Esri historical map location of the salt beach area, inside Sacapulas’ town. Note how the river has changed its flow to the south, as well as regularize the shape of its current compared to the flow it had in 2011. Modified by author]. Retrieved from https://livingatlas.arcgis.com/wayback accessed on 2 January 2023.

Figure 11.

Comparison between July 2012 (a) and April 2019 (b). Chixoy River flow in July 2012: red. Chixoy River flow in April 2019: blue Esri (n.d.). On this case, the focus areas “A” to “D” present modifications, yet it is area “C” the one that is modified the most. [Esri historical map location of the salt beach area, inside Sacapulas’ town. Note how the river has changed its flow to the south. As well as regularize the shape of its current compared to the flow it had in 2012. Modified by author]. Retrieved from https://livingatlas.arcgis.com/wayback accessed on 2 January 2023.

When analyzing the oldest available aerial photography and the most recent images, it is evident that there is a constant loss of land at points B and D. Also, the birth of a small river at point C is probably due to the increased flow of the Chixoy River. It is also evident how the river regularizes the shape of its current, becoming less crooked and less curved. Meanwhile, the July 2012 photo shows new divisions that cut the land of the “island” into three parts (area C in Figure 12). Compared to the flow presented in 2011, the river has grown considerably. It is also evident that the meander of the river has increased considerably in size, reducing the beach space.

Figure 12.

Comparison between April 2019 (a) and November 2019 (b). Chixoy River flow in April 2019: red. Chixoy River flow in November 2019: blue. On this case, it can be seen that the area “B” (the current salt beach) and area “C” (the previously mentioned lost space) are the most affected due to the influence of the river. [Esri historical map location of the salt beach area, inside Sacapulas’ town. Note how the river meander tends to move southward. Modified by author]. Retrieved from https://livingatlas.arcgis.com/wayback accessed on 2 January 2023.

The photo from April 2019, shows a reduced flow compared to 2012, however the intermediate partition was maintained. There is evidence of the intermediate partition moving southward. There is no significant variation at point B. The last available photo showing changes is also from 2019. Taken in November, there is a loss of area due to the meandering of the river. In addition, the flow of the river has increased considerably. After 2019, the Chixoy River is the same.

Only satellite data confirm that there is a constant movement of the river channel due to increased inflow during the last few years. The loss of the salt beach area is precisely because of the prominence in river meandering at point B. The river inflow was strong enough to generate separation at point C in 2011. According to comments by subjects PSS-A 1 and MSS-H, the original beach reached as far as point D. There are also mentions by the chronicler Don Martyn Alfonso Tovilla about the extension of the beach territory. This mention reinforces the idea that the meander of the river was less prominent in the 19th century and non-existent in colonial times. Finally, according to the photographic data, only the beach area is affected since point A (connection to the town of Sacapulas) does not seem to be modified in any way.

It is worth mentioning that this visual analysis does not show how the town of Sacapulas reintegrates the “island” area. Furthermore, the site visit confirmed that this area is abandoned. Areas A and D show slight changes in the course of the river in 2014 (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Summary of the Chixoy river movements from 2011 to 2019. Chixoy River flow in April 2019: red. Chixoy River flow in February 2011: blue. As discussed, the analysis areas of “A” to “D” are affected constantly due to the Chixoy river. The red arrows present the movement of the Chixoy river during the years. [Esri historical map location of the salt beach area, inside Sacapulas’ town. Modified by author]. Retrieved from https://livingatlas.arcgis.com/wayback accessed on 2 January 2023.

According to the information obtained by subjects PSS-A 1 and MSS-H during the two interviews, the area of the beaches started from a mangal (mango tree still existing in the current area of the black salt) to the pit (a pit located at point D, where two churches currently exist). This means there is a constant loss of land from point B (meander of the river) to point D (mentioned by interviewees).

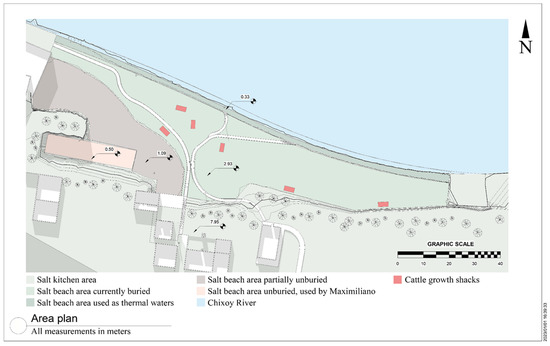

3.6. Planimetry Observations

The current beach area is located north of the town of Sacapulas, next to the Chixoy River. During the site visit, it became evident that, compared to the few existing images of the area, the beach area has been almost totally modified. With the help of the plans, it was possible to analyze the total area of the salt beach. The area can be divided into five different types according to its condition and use. The current surface area is 4873.42 m2, of which almost 57% is covered with soil. Meanwhile, 23% is partially excavated, and MSS-A uses only 5% of this space. His area is the only one known to still be used at time of doing this research. According to his information, his land was excavated by him, and this process took about four years according to the interview (2010 to 2014). Of the total area, almost 4% is dedicated to roads. These roads are dirt roads, so they do not represent any formality in their development nor a regularity in their width.

According to interviews, the method of the decision to shape these roads is still being determined. However, it is hypothesized that it was primarily due to functional reasons caused by the different activities found in the area. These range from obtaining salt-impregnated soil to digging holes in the shore and obtaining hot water (hot springs). A specific activity found in the area is cattle ranching. This is carried out irregularly through the use of six constructions (huts) identified within the area. Due to the disuse of the buried area (55.76% of the total space), cattle use this area for feeding. From the interviews, it is impossible to determine the legality of these constructions, although it is known that at least some of them belong to direct relatives of former salt workers (Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16).

Figure 14.

Area plan of the salt beach.

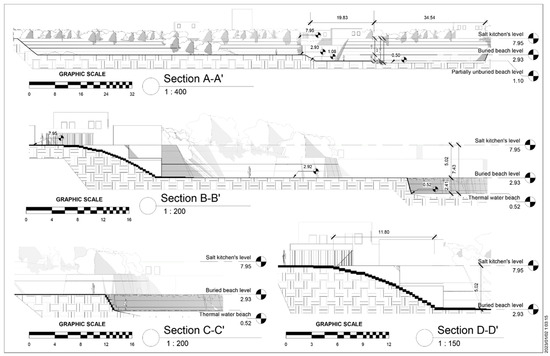

Figure 15.

Measurement plan of the salt beach. The lines “A” through “D” are section lines represented in Figure 16. Section A and B represent the entirety of the terrain, while C and D represent significant changes in elevation.

Figure 16.

Sections of the salt beach.

To create the black salt, it is necessary to use architecture specific to the town of Sacapulas called “Cocinas de sal” (salt kitchens). These kitchens serve as a space to boil the earth impregnated with salt; they also serve as warehouses to manage all the earth with salt to be used throughout the year. The location of these kitchens is south of the actual salt beach, and their access road is made of concrete and stone steps located in connection with the area of the kitchens (Table 4). After finishing the site measurements, it was determined that they do not follow a specific width. This is due to nature growing to the sides of the steps, reducing the usable area. They also do not present rest areas in between certain amount of steps, resulting in an excessive amount of energy needed to transit such stairs. It is known that at least one salt-maker (MSS-A1) uses this trail to access his area. This is an extreme danger due to his advanced age which can potentially result in future negative consequences (Figure 17, Figure 18, Figure 19 and Figure 20).

Table 4.

Summary of salt beach zone areas.

Figure 17.

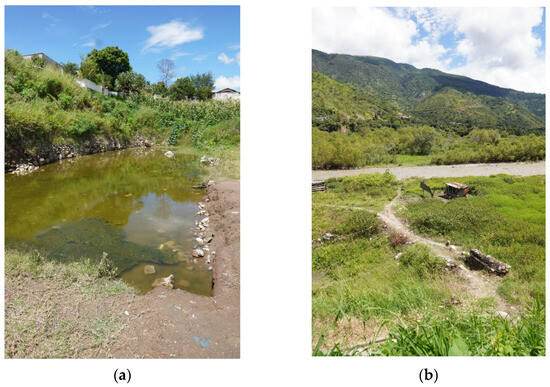

(a) Unburied salt beach, the only place still used my MSS-A (Maximiliano). (b) Irregular roads located inside the buried salt beach.

Figure 18.

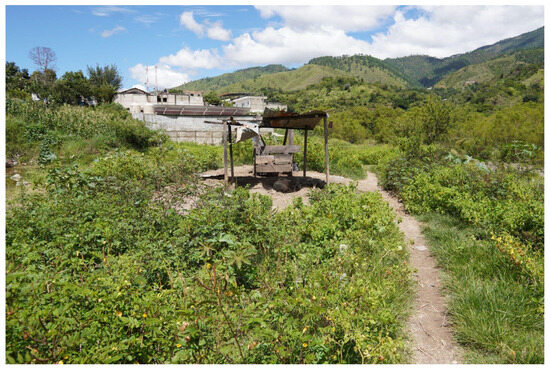

Huts used by people to raise cattle. The legality of these spaces is yet to be determined.

Figure 19.

Sacapulas people using the black salt beach’s shore as a bathing area. This is due to the thermal waters found by opening a hole in the shore.

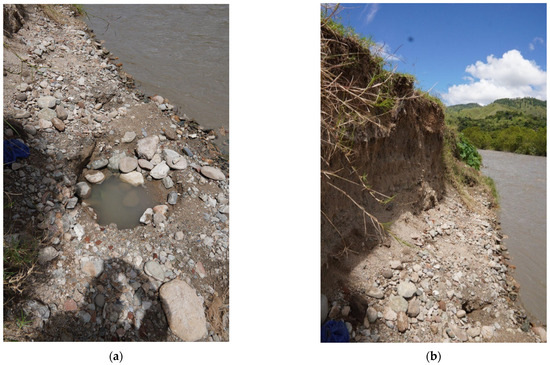

Figure 20.

(a) Example of the hole opened in the shore to extract thermal waters (b) Shore of the beach. It can be noticed the amount of soil that has accumulated in the beach, resulting in the space lost and industry shrunk.

4. Discussion

Disaster response in Guatemala (and, in an extension, Latin America) are defined not by the quality, but by the quickness of information shared pertinent to the situation [43] and their proper usage in decision-making [44]. This is due to the fast occurrence of events, remote location of villages, and immediate access to help. At the start of this research, it was understood that the towns and villages surrounding the Chixoy river suffer from the three characteristics previously mentioned, resulting in a high vulnerability to floods [38]. What was unknown was the extent and consequences of floods in the town of Sacapulas. This research successfully evaluated the current state of the black beach area since the last research conducted in 2004, exposing a major risk of culture loss for the Mayan people. The most important findings are the understanding of the evolution of the space, its value for the local people, and its current value perception due to its usage. It also created the first planimetry area maps of the space, as this kind of visual information has been lacking since the inception of the town. In addition, a surprise finding was that the value of the area has been reinterpreted by the local people, creating a new sense of value while losing most of its cultural roots.

As predicted, the original black salt beach was much larger than it is today. This is corroborated by the Spanish chronicles mentioning the original size of the space and correlated with the interviews and site analysis conducted. Unlike nowadays, the community of Sacapulas always attempted to recover the area once a natural disaster occurred, which kept it relatively safe from modifications. It can be hypothesized that this work was performed since colonial times, and the importance of the black salt was perceived by all members of the village. By engaging in a community activity, this could have strengthened the ties of everyone involved, while maintaining a collective understanding of the importance of the beach. This cleaning process can be considered as a system of indigenous knowledge systems and practices (IKSPs), where the people themselves know the process to recover the area after a natural disaster [9]. However, the IKSPs shown by Sacapulas’ people could not cope with the increased magnitude of recent floods. Instead, the use of machinery was needed to recover the area which was only granted once in 1951. By being impossible to recover the area and not engaging in the IKSPs, the ties between the village, salt production, and its intangible cultural roots slowly eroded. After the events, the IKSPs were never shared across the generations and resulted in a breakout point between community and the land. It makes sense, as new generations have no idea of what is needed to recover the area. The only person conducting these IKSPs is MSS-A, an elderly person. None of the previous research regarding Sacapulas mentioned the magnitude of the vulnerability nor the IKPSs of Sacapulas.

With cultural roots threatened and being slowly lost, loss of cultural perception has taken place. This manifests itself in two ways: lack of ownership knowledge and loss of rites and religion. First, the lack of formal documentation of the space results in legal problems regarding the current ownership of the land. Initially, it was believed that the perceived value of the area was mostly by people related to the black salt industry. However, this does not hold true as townspeople use the area as hot springs. This fact has been extremely crucial in the current perception of the area because it increases the value of the area to the community. This activity was not previously documented by any research. It is believed that without any regularization by the authorities, the area may become a point of conflict due to its potential monetary value; the area is currently exploited by a nearby beach hotel.

Second, and probably the most critical aspect, is the loss of Sacapulas rites, religion, and culture due to the loss of space. This knowledge is commonly transmitted from generation to generation and includes practices that can improve response to immediate risks. Yet, as mentioned before, this is not the case with new generations. This has extended to the Mayan rituals exclusive to the Sacapulas town, whose information was never the focus of previous researchers. According to the results obtained, it is understood that the practice of salt beach cleansing and Mayan mysticism were always known by the salt-makers. They, in turn, shared their knowledge with the town. But, as fewer salt-makers continued to work in the industry, this information was devalued over time. It is not known at this point if they tried to share this knowledge with younger generations to keep the traditions going.

While floods are the main cause of this, other factors could have also had negative influences. Such examples are the lack of ownership documents, local economic shift, spread of protestant religion in rural areas, and political problems during the internal war era (1960–1996). With many reasons to stop developing the industry, many of the salt workers changed professions, leaving only the four people active at this moment. Most of the ex-salt-makers passed away and the remaining ones are elders, so obtaining information of the rites is an active issue that needs to be addressed as soon as possible. Such issues emerged during the development of this research and extended to the interview phase. Complex questions could not be addressed extensively, as the cognitive abilities of the correspondents made it challenging.

To understand what has been lost, the importance of Sacapulas to the Mayan history must be reiterated. It is known that the town of Sacapulas was an important point in the development of trade routes for salt production in the region [29,32]. It is also known that the importance of salt was rooted in the Mayan rites that explain its conception. It is also known that it was the Mayan kingdom of Quiche (Q’umarkaj in K’iche’) conquered the area due to its importance [29]. This importance of rites and culture extended beyond the conquest. Interviews determined that the rites performed in late years were of a Christian character. The only explanation for this is some kind of syncretism between both cultures: “The attempt to combine opposing doctrines and practices, especially in reference to philosophical and religious systems” [45], which occurs after the Spanish conquest. It is the importance of these rites that pushes the local community to find a way to continue their roots, even if it means mixing them with an invading culture. However, the death of the father of informants MSS-E and D resulted in the last celebration. Assuming that the syncretism of cultures occurred in 1548, around 454 years of culture died in 2002. The lack of interest in this subject is unacceptable and demonstrates a lack of interest on the part of both local entities and the Guatemalan government. If this continues, the tangible cultural aspects will be lost as well. These are materialized through the salt kitchens and the salt itself. The impact they have suffered up to this point is not yet known, and further research is needed related to location, condition, and current use.

By conducting this research, it was evident that the extent of the work to be achieved is bigger than the expertise of the researcher. Further analysis could focus specifically on three main points: analysis of the current situation of tangible culture elements, understanding on detail the usage of the beach, and a proposal to safeguard the culture while reducing the potential risk of the Chixoy River. Other topics fall into categories where other researchers could be interested, such as the detailed process of the black salt creation considering the temperature and characteristics needed for its creation; and soil analysis under the current Chixoy River to pinpoint the original extension of the black salt beach.

5. Conclusions

The existence of black salt has been important for both the region and culture in Guatemala. Meanwhile, the beach space has been important specifically for the people of Sacapulas. Culture, history, and IKSPs are directly linked to this space. The loss of the industry and space has not only greatly affected the Sacapulas people, but also the Guatemalan people. Specifically, the perceived cultural value of the area has shrunk tremendously due to constant floods and post-disaster mismanagement. Yet, thanks to the thermal waters used for the creation of salt, the use of the beach has been reinterpreted by the people of Sacapulas: a new value has been found in the beach. This value is directly benefiting the towns around Sacapulas. However, the use of the space has been irregular and does not present any current planning to recover the idle spaces or formalize current activities. Without a formality, the true value of the space has not been fully developed. This presents a new risk to the people in the area for two reasons. First, the space used is located next to the Chixoy River, which flows at high velocities. Second, people are taking over the active area, which means a reduction in the area usable by the people of Sacapulas. If neither of these two problems can be solved, the result will be the appropriation of public services and the loss of human lives due to the Chixoy River.

For these reasons, immediate intervention is necessary to recover the natural resources of this beach or at least reorganize its use for future generations. Because both the current salt workers and the people of Sacapulas use the area, its value has increased. Therefore, it is necessary to deepen the knowledge of the real value of the space. What is the frequency of use and influence? What are the actors that use the area? How can we quantify this and, if possible, understand its true relation to the town of Sacapulas? These are questions that can move forward a proper response in the area. Along with this, it was found that the tangible cultural elements are at risk of being lost. There needs to be research conducted to prevent this: further research is needed to assess their current situation.

However, this project cannot be developed unless there is cooperation, meaning the support of the main and local authorities of Guatemala, something that historically has been weak. While this is quite the challenge, other countries have successfully adapted indigenous communities’ knowledge with vulnerability reduction. These examples have proven exceptionally well in such situations where decision makers and townspeople have to work together. This approach has not been yet implemented in the region, but it shows an opportunity to make a positive change in Sacapulas. If IKPS methods are implemented successfully in local disaster management, Mayan communities all across Guatemala could potentially benefit too. It is understood that more research is needed, and cooperation could be better. Yet, it is something that can bear fruit to a better, more resilient future for everyone.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M. and L.P.Y.S.; methodology, L.P.Y.S.; software, L.P.Y.S.; validation, S.M. and R.N.; formal analysis, L.P.Y.S.; investigation, L.P.Y.S.; resources, S.M., R.N. and L.P.Y.S.; data curation, L.P.Y.S.; writing—original draft preparation, L.P.Y.S.; writing—review and editing, S.M. and R.N.; visualization, L.P.Y.S.; supervision, S.M. and R.N.; project administration, S.M. and R.N.; funding acquisition, S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study since no data and information related to the ethical guidelines were at the discretion of the committee at Hokkaido University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

A big acknowledge to RAICES for their help during the development of this research. A big thanks to the people of Sacapulas that has helped to conduct this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Example of the Semi-Open Questionnaire Performed in Sacapulas

Appendix B. An Example of the Microanalisis Tool Used in the Interview, Where the Time, Interviewee and Concept Are Organized

| Concept | <Terrain> | |

| Definition | Information | |

| Itterations | PSS-A-1,2 | 00:28 I: At what point was all that space filled? A-1: When they came, they left the area...; the bosses didn’t come anymore... to plant or something like that. And others left the place. |

| 24:18 I: Do you remember more or less where the salt was before? A-1: Yes, there on the beach, where that hole was (area C). There were salt pans belonging to an owner that was there. And that’s where it started, where there was a mangal. | ||

| PSS-D | 00:07 D: The earth stayed and go, who is going to activate That’s why we needed to study more, we needed to work more. | |

| Theoretical notes | Those involved do not have exact knowledge of where each person’s land is located. No specific dates were mentioned, so there is a gap at this time. | |

References

- Sabatini, F. Culture as fourth pillar of sustainable development: Perspectives for integration, Paradigms of Action. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrant, L.J.; Vadher, A.N.; Teller, J. Disaster Risk Management and cultural heritage: The perceptions of european world heritage site managers on disaster risk management. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 89, 103625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrant, L.J.; Vadher, A.N.; Sarač, M.; Başoğlu, D.; Teller, J. Using organigraphs to map disaster risk management governance in the field of Cultural Heritage. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.L. Sustainable development. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030—PreventionWeb. 18 March 2015. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/files/43291_sendaiframeworkfordrren.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- United Nations. Risks and Disasters. Available online: https://www.un-spider.org/risks-and-disasters (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Fatorić, S.; Seekamp, E. Are cultural heritage and resources threatened by climate change? A systematic literature review. Clim. Chang. 2017, 142, 227–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, P.; Ninglekhu, S.; Hollenbach, P.; McCaughey, J.W.; Lallemant, D.; Horton, B.P. Rebuilding Historic Urban Neighborhoods After disasters: Balancing disaster risk reduction and heritage conservation after the 2015 earthquakes in Nepal. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 86, 103564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawangen, A.; Roberts, J.K. Interactions between disaster risk reduction and intangible culture among indigenous communities in Benguet, Philippines. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 94, 103801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vhurumuku, E.; Mokeleche, M. The nature of science and indigenous knowledge systems in South Africa, 2000–2007: A critical review of the research in Science Education. Afr. J. Res. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2009, 13 (Suppl. S1), 96–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, A.; Santangelo, A.; Tondelli, S. Investigating the integration of cultural heritage disaster risk management into urban planning tools. The Ravenna Case Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrecht, G.; Rockman, M. International approaches to climate change and cultural heritage. Am. Antiq. 2017, 82, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Local and Indigenous Knowledge Systems (Links). UNESCO.org. 1 January 1970. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/links (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Fernandez, M. Risk perceptions and management strategies in a post-disaster landscape of Guatemala: Social conflict as an opportunity to understand disaster. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 57, 102153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Lemus, V.M. Disaster risk governance in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic in Central America: The case of Guatemala. Pandemic Risk Response Resil. 2022, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, J.G.; Hernandez, M.A. The unintended consequences of confinement: Evidence from the rural area in Guatemala. J. Econ. Psychol. 2023, 95, 102587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congreso de Guatemala. Decreto Legislativo ley 109-96. Decreto Legislativo 109-96. 7 November 1996. Available online: https://www2.congreso.gob.pe/sicr/cendocbib/con2_uibd.nsf/52B034338E20D4570525770C0060034B/$FILE/Decreto_109.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk. Yokohama Strategy and Plan of Action for a Safer World: Guidelines for Natural Disaster Prevention, Preparedness and Mitigation. PreventionWeb. 4 February 2009. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/publication/yokohama-strategy-and-plan-action-safer-world-guidelines-natural-disaster-prevention# (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- U.S. Agency for International Development. Guatemala: Humanitarian Assistance. 31 May 2023. Available online: https://www.usaid.gov/humanitarian-assistance/guatemala (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Me-Bar, Y.; Valdez, F. On the vulnerability of the ancient maya society to natural threats. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2005, 32, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sioui, M.P. Drought in the Yucatan: Maya perspectives on tradition, change, and adaptation. In Current Directions in Water Scarcity Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 2, pp. 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.L.; Sabloff, J.A. Classic period collapse of the Central Maya Lowlands: Insights about human–environment relationships for Sustainability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 13908–13914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SGCCC. Primer Reporte de Evaluacion del Conocimiento Sobre CAMBIO CLIMATICO en Guatemala. 1er Reporte de Cambio Climatico en Guatemala. 2019. Available online: https://www.sgccc.org.gt/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/1erRepCCGua_Introduccion.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- World Risk Report 2022. Bündnis Entwicklung Hilft, Ruhr University Bochum—Institute for International Law of Peace and Conflict 2022. Available online: https://weltrisikobericht.de/weltrisikobericht-2022-e (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Sabbioni, C.; Cassar, M.; Brimblecombe, P.; Lefevre, R.A. Vulnerability of Cultural Heritage to Climate Change. Pollut. Atmos. 2009, 202, 157–169. [Google Scholar]

- Citypopulation. Available online: https://www.citypopulation.de/en/guatemala/admin/ (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- De Fuentes y Guzmán, F.A. Recordación Florida; Dirección General del Diario de Centro América y Tipografía Nacional: Ciudad de Guatemala, Guatemala, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tovilla, M.A.; Scholes, F.V.; Adams, E.B. Relaciones Histórico-Descriptivas de la Verapaz, el Manché y Lacandón en Guatemala; Editorial Universitaria: Santiago, Chile, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Akkeren, R. Título de los señores de Sacapulas. In Crónicas Mesoamericanas; Cabezas Carcache, H., Akkeren, R., Eds.; Universidad Mesoamericana: Guatemala City, Guatemala, 2008; pp. 59–91. [Google Scholar]

- Reina, R.; Monaghan, J. The Ways of the Maya Salt Production in Sacapulas, Guatemala; expedition; University of Pennsylvania: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1981; Volume 23, pp. 13–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ordóñez Chocano, A. Estudio Histórico Antropológico de la sal Negra en Sacapulas, Departamento del Quiché, Guatemala. Tradiciones de Guatemala; CEFOL, Universidad San Carlos de Guatemala: Guatemala City, Guatemala, 2005; Volume 59, pp. 159–192. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, A. Maya Salt Production and Trade; University of Arizona: Tucson, AZ, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Garza Martínez, V. Medidas y caminos en la época colonial: Expediciones, visitas y viajes al norte de la Nueva España (siglos XVI–XVIII). Front. Hist. 2012, 17, 191–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnsour, M.A. Using modified grounded theory for conducting systematic research study on sustainable project management field. MethodsX 2022, 9, 101897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; Knight, P.T. Interviewing for Social Scientists; SAGE Publications, Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, G.A.; Brooks, G.P. Initial Scale Development: Sample Size for Pilot Studies. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2010, 70, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambaru, A. Qualitative Research and a Modified Grounded Theory Approach. Tsuru Univ. Rev. 2018, 88, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CONRED. Disaster Maps. 2015. Available online: https://conred.gob.gt/mapas/municipales_ameindes/QUICHE/SACAPULAS/QUICHE%201416.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Zomrawi, N.; Ahmed, G.; Eldin, M. Positional accuracy testing of Google Earth. Int. J. Multidiscip. Sci. Eng. 2013, 4, 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Oliva, W. Reportan Inundación Súbita en Sacapulas, Quiché. Prensa Libre. 1 July 2021. Available online: https://www.prensalibre.com/ahora/ciudades/quiche/reportan-inundacion-subita-en-sacapulas-quiche/ (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Inundación en Quiché Deja Daños, Heridos y un fallecido. Cruz Roja Guatemalteca. Available online: https://www.cruzroja.gt/noticias/inundacion-en-quiche-deja-danos-heridos-y-un-fallecido/ (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- CONRED. Boletín Informativo no. 2790—LLUVIAS de las Últimas 24 Horas Afectan a 46 Personas. 24 August 2012. Available online: https://conred.gob.gt/boletin-informativo-no-2790-lluvias-de-las-ultimas-24-horas-afectan-a-46-personas/ (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Müller, A.; Bouroncle, C.; Gaytán, A.; Girón, E.; Granados, A.; Mora, V.; Portillo, F.; van Etten, J. Good data are not enough: Understanding limited information use for climate risk and food security management in Guatemala. Clim. Risk Manag. 2020, 30, 100248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Raya, N.; Díaz-Pacheco, J.; López-Díez, A.; Dorta Antequera, P.; Cabrera, A. A lava flow simulation experience oriented to disaster risk reduction, early warning systems and response during the 2021 volcanic eruption in Cumbre Vieja, La Palma. Nat. Hazards 2023, 117, 3331–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, E.A. Syncretism. In The Concise Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).