Abstract

In response to the increasingly severe climate crisis, the tourism industry has been implementing ESG management and carbon-neutral policies, and sustainability has become the top priority. In this reality, slow tourism is expected to be a sustainable alternative. This study proposes a model of self-expressiveness for slow tourism using the example of Trans-Siberian Railway travel. The main purpose of this study is to analyze the process of the formation of self-expressiveness with the Trans-Siberian Railway experience, its relationship with hedonic enjoyment, and its impact on the life satisfaction of tourists. This research delves into the effects of eudaimonistic identity on life satisfaction via SEM. Moreover, the moderating role that self-expressiveness plays between hedonic enjoyment and life satisfaction is noteworthy, which was assessed based on the bias-corrected (BC) bootstrap method procedure. The data were gathered through an online survey on Instagram and Facebook using a self-administered questionnaire. A total of 210 respondents who had traveled by train in Siberia were used for the analysis. The results indicate that the more Siberian train tourists encountered the flow experience, self-realization, perceived authenticity, and hedonic enjoyment, the greater their self-expression, which had a favorable effect on life satisfaction. In addition, self-expression fully mediated the relationship between hedonic enjoyment and life satisfaction. This research makes a contribution in that it applies eudaimonistic identity theory, which has previously only been applied in the context of leisure, to tourism. Theoretical and practical implications and suggested avenues for future research are also presented.

1. Introduction

The human pursuit of happiness and well-being has always been a powerful stimulus for progress and development in all spheres of life. The desire for a better personal and social life and environmental sustainability has changed the traditional understanding of leisure and tourism [1]. Nowadays, tourists are more conscious not only of the quality of their experiences but also of their consequences. Thus, new types of tourism such as ecotourism, cultural and heritage tourism, health and medical tourism, and slow tourism have emerged. Slow tourism is an alternative form of tourism that originated from the philosophy of slowness, which stands in contrast to our modern fast, busy, and competitive lifestyle. Since the phenomenon of slow tourism is relatively new and has only started to gain attention in the academic literature during the last decade [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9], there is no consensus among researchers about its exact definition or its key principles. However, the importance and potential of slow tourism as an emergent market segment have been proven by empirical data [10]. Caffyn [2] asserted that slow tourism authors place too much attention on defining slow tourism, while the problem of promoting slow tourism and encouraging visitors to make “slower choices” is more urgent, as slow tourism can offer a variety of benefits for tourists, such as more valuable and authentic experiences for destinations and local communities, more sustainable and green forms of tourism, and opportunities for local business development [2,3,4,11].

Geopolitical shocks have a negative effect on tourism, particularly wars [12,13,14,15]. As a result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, travel demand has decreased. As of 2020, Russia and Ukraine accounted for three percent of global tourism expenditures, and a prolonged conflict in 2022 could result in a loss of USD 14 billion in global tourism revenues [16]. Currently, Russian tourism marketers need to find new promotional strategies that would remedy and improve the global image of Russia and expand its international tourist market. Considering the present interest in alternative forms of tourism as opposed to mass tourism and the global shift toward sustainable tourism, one strategy could be promoting travel by the Trans-Siberian Railway as a slow tourism experience. Previous studies have shown that the concept of “slowing down” can be adapted and applied as a destination marketing strategy to locations all around the world by using different dimensions of slow tourism based on place characteristics [2,3,4,5,6,7,8].

The Trans-Siberian (Trans-Sib) Railway is the world’s longest east-west train route, connecting Moscow to Vladivostok. It is on the list of top “must do” attractions in Russia; the route includes St. Petersburg, Moscow, Sochi, and Lake Baikal [17]; and it is also in the Guinness Book of Records as the longest journey (8000 km) in one week [18]. The Trans-Sib is one of the largest companies in the global transport sector, contributing about 1.6% of GDP to the Russian economy. It was ranked fourth in the world for passenger rail transportation, transporting over 1031 billion passengers in 2016 [19,20]. Since the railway functions as a bridge that connects Eastern and Western Russia, the majority of passengers are Russian. Thus, almost all company promotions are focused on the domestic market. During the last three years, domestic passengers traveling via the Trans-Sib have decreased as more passengers prefer to travel by air [20]. Moreover, experts expect this tendency to continue [20], so Russian railways need to start focusing on international tourists whose interest in the Trans-Sib has remained constant.

All human activities can be divided into three categories: activities that cause hedonia, activities that cause both hedonia and eudaimonia, and activities where neither hedonia nor eudaimonia occur [21]. As slow tourism is different from mass tourism, it is usually defined as a hedonic activity [21,22]. In this study, the Trans-Siberian travel experience is proposed as an activity that raises both hedonic enjoyment and eudaimonia (self-expressiveness) to induce in tourists the feeling of being alive and fulfilled, which contributes to life satisfaction and happiness. Though several authors [1,2] have mentioned the positive influence of slow tourism on well-being, no studies on slow tourism from this perspective have been conducted. Drawing upon the ideas of Moore [1] regarding hedonia and eudaimonia in slow tourism and self-expressiveness theory [23], this research investigates how self-expressiveness in slow tourism affects tourists’ overall life satisfaction through the Trans-Siberian Railway. Moreover, by applying self-expressiveness theory to the slow tourism context, this study proposes perceived authenticity as an important predictor of self-expressiveness.

The main purpose of this study is to understand the process of forming self-expressiveness in the Trans-Siberian Railway experience and its influence on tourists’ life satisfaction. To achieve this, the following objectives are presented: (1) to provide a general overview of the academic literature on slow tourism, hedonia, and eudaimonia; (2) to identify factors affecting the formation of self-expressiveness with the Trans-Siberian Railway travel experience; and (3) to examine the relationship between self-expressiveness and hedonic enjoyment with the Trans-Siberian Railway travel experience and its influence on tourists’ life satisfaction. As a result, the goal of this paper is to investigate (1) how flow experience, self-realization, perceived effort, perceived authenticity, and hedonic enjoyment felt by Siberian train travelers influence self-expressiveness and life satisfaction; and (2) how self-expressiveness mediates the relationship between hedonic enjoyment and life satisfaction. This study contributes theoretically and practically to slow tourism research and should help researchers and practitioners build marketing strategies for slow tourism and travel industry stakeholders.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Slow Tourism

Slow tourism is a tourist-oriented approach that aims to enhance the quality of the tourism experience by providing a deeper understanding of the experience and by promoting enjoyment [3]. Along with other alternative forms of tourism, slow tourism encourages a philosophical, ethical, and aesthetic rethinking of traditional notions of leisure. Originating from the Italian Slow Food movement, slow tourism emerged in response to fast food and emphasizes healthy nutrition, local cuisine, and the enjoyment of food [24]. Slow tourism diverges from mass tourism, which emphasizes a rigid itinerary and a checklist of must-see sights to be visited within a limited time frame. This type of tourism can leave tourists feeling fatigued and in need of recovery upon returning home. In contrast, slow tourism provides opportunities for more meaningful and valuable experiences [25,26].

Lee [26] emphasizes that slow tourism should not be viewed solely as an antithesis to fast tourism. Rather, slow tourism promotes a deeper exploration of destinations through interactions with local residents, sampling traditional local food, and contemplating the value of life. Thomas [27] presents the acronym SLOW to define slow tourism: sustainable, locally focused, organic, and whole. Dickinson and Lumsdon [4] described slow travel as encompassing sustainable forms of transportation, longer stays at the destination, engagement with local transportation, food, and culture, and support for the environment. Similarly, Hall [28] suggests that slow tourism involves reducing travel distances, traveling at a leisurely pace, and staying longer in one place.

Slow tourism is a concept that extends beyond providing tourists with experiences and pleasures; rather, it aims to benefit not only tourists but also the local community and environment of the destination [3]. Slow tourism emphasizes the need to address destination issues, and it can be associated with the concept of slow growth, which prioritizes both socio-economic development and environmental sustainability [3]. In essence, slow tourism promotes a more comprehensive strategy for sustainability and supports the preservation of the unique local identities associated with leisure, sense of place, hospitality, and rest and recuperation [29,30].

2.1.1. Train Tourism

Train tourism has emerged as a viable alternative tourism product in many destinations worldwide [31]. This form of tourism is becoming increasingly popular due to its lower environmental impact, excellent safety record, and affordability. According to Dickinson and Lumson [4], train tourism provides a superior travel experience compared to other modes of transportation and contributes to the development of remote areas. Although trains were not originally designed for leisure and tourism purposes, scenic routes, luxurious train cars, and onboard experiences have transformed railway journeys into tourist routes [31]. Nowadays, trains are a crucial mode of transportation for tourists, especially in European countries such as France and Germany. What are also notable are Japan, with its high-speed trains; Russia’s Trans-Siberian Railway; and India’s Darjeeling Himalayan Railway, where trains play a significant role in domestic travel [31]. Other examples of famous train journeys include the Cusco-Sacred Valley-Machu Picchu route in Peru, the Blue Train route in South Africa, and the Qinghai-Tibet railway in China.

In general, railway services can be classified based on their main purposes, speeds, and distances [4]. Short-distance trains, also known as rural trains, are popular among tourists due to their nostalgic atmosphere and scenic routes. Long-distance trains that travel across different countries and offer sleeping carriages typically cover distances exceeding 1000 km. Although long-distance trains often operate at high speeds of over 300 km/h, some journeys, such as the Trans-Mongolian or the Trans-Siberian, may move more slowly [4]. While there are general trains that cater to regular travel needs, there are also tourist trains that are specifically designed to provide a unique experience for tourists. However, some general long-distance and regional trains, such as the Trans-Siberian and Interrail, still hold value for tourists [32]. Recently, train tourism has garnered academic attention as a form of slow and sustainable tourism with lower environmental impacts [4,33] and an excellent alternative for tourists who lack their own means of transportation [34]. Despite the increasing demand for this form of tourism, research on the topic remains limited [31].

Bagnoli [33] based his study on the four dimensions of slow tourism proposed by Lumsdon and McGrath [4] and investigated their applicability to the Roia Valley railway line. Based on the results of the study, the enjoyment of the destination and its people, as well as the train journey itself as a core travel experience, were found to be significant factors for tourists visiting the Roia Valley. Slow tourists were found to not only prefer slower modes of transport but also had a unique attitude towards how they spent their time during travel, which distinguished them from mass tourists. Although sustainability was found to be a “utopia,” as tourists were more concerned with their own experiences than the sustainability of the destination, the study still provides insight into the potential benefits of slow tourism for certain destinations [33].

2.1.2. The Trans-Siberian Railway

The original name of the Trans-Siberian Railway was supposed to be “The Great Siberian Way”, but it became more commonly known as the “Trans-Siberian” among people [35]. As the only overland route that spans the country, the Trans-Siberian Railway continues to play an important role in Russia’s economy and transportation system, just as it did when it was first built. The need for the railway arose from economic challenges related to the country’s vast size, but upon completion of the project, it became a point of pride for the entire nation [35]. Construction of the railroad began in 1891, simultaneously from the central part of the country to Vladivostok, and despite harsh weather conditions, unpopulated areas, and supply issues, it was completed in 12 years [36].

Nowadays, the Trans-Siberian Railway is divided into four different routes:

- The Trans-Siberian Route (Moscow–Vladivostok)—the original Trans-Siberian railway running all across the country to Vladivostok. It is divided into two sub-routes: the main (Moscow–Yaroslavl-Kirov–Perm–Ekaterinburg–Siberia–Vladivostok) and the southern (Moscow–Kazan–Ekaterinburg–following the main route);

- The Trans-Mongolian Route (Moscow–Ulan-Bataar–Beijing) runs through Mongolia to China;

- The Trans-Manchurian Route (Moscow–Harbin–Beijing) goes directly to China;

- The Baikal–Amur Route—a second rail connection from Siberia to the Asia-Pacific region [20].

2.2. Hedonia, Eudaimonia, and Slow Tourism

According to ethical philosophy, happiness and well-being are the ultimate goals of human existence [21]. The concept of well-being encompasses two distinct philosophical components: hedonia and eudaimonia. Both components attempt to explain the essence of living well, yet they represent two entirely different perspectives. The hedonic perspective characterizes well-being as happiness, where pleasure reigns supreme and negative experiences and discomfort are absent [37,38,39]. Aristippus, the Greek philosopher regarded as the father of hedonism, taught that happiness is “the totality of one’s hedonic moments” [38]. The eudaimonic perspective stems from Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, where he defines human happiness as living a good life that promotes human flourishing [40,41]. Eudaimonia holds significant meaning because it is distinct from the enjoyment perspective: eudaimonic theories suggest that not every pleasurable experience benefits people’s well-being [38]. While eudaimonia and hedonia can be seen as two contrasting philosophies regarding the path to living well, they are strongly correlated in studies. Some authors have shown that the simultaneous pursuit of hedonic enjoyment and eudaimonia contributes more to well-being than the pursuit of either one alone [40,42]. Furthermore, these two concepts are not just intrinsically desirable experiences; they are also linked to other important human functions [43].

Eudaimonistic identity theory relates to the theories of intrinsic motivation that are considered to be the core of human positive psychological functioning [44]. The theory suggests that both hedonia and eudaimonia are positive subjective states that individuals can experience when engaged in certain activities [22,45]. When individuals focus on developing their best potential, both hedonia and eudaimonia are more likely to emerge [22,45]. Waterman [22] argues that when individuals experience eudaimonia, they are more likely to recognize their best potential in order to achieve successful identity formation. He calls this state “feelings of personal expressiveness” [45]. Personally expressive activities make people experience an unusually intense involvement, a feeling of being fully engaged with the activity, a sense of being alive, a feeling of fulfillment, a sense of being what one was meant to be, and a sense of being true to oneself [45]. Furthermore, activities that enhance self-expressiveness are positively related to overall life satisfaction and happiness [22,45].

The main concept of this article, “slow”, has sparked philosophical and moralistic debates concerning the modern trend of mass tourism and proposes specific behaviors expected to promote social, cultural, and personal flourishing [1]. Alternative forms of tourism aim to encourage people to become wise, autonomous travelers who can maximize their personal well-being [46]. Additionally, the development of integrated human well-being requires characteristics such as close social relationships, nature fulfillment, self-improvement, and knowledge of people and places that can be found in slow tourism experiences [1]. In other words, slow tourism includes both hedonic and eudaimonic elements. Based on the positive impact of travel experiences on well-being demonstrated in previous studies [47,48] and the ideas of Moore [1] mentioned above, this study applies the eudaimonistic theory [22,45] and attempts to connect slow tourism with the two components of well-being.

2.3. Flow Experience and Self-Expressiveness

The concept of flow was originally defined as “optimal experience” [49]. According to Nakamura and Csikszentmihalyi [50], flow occurs when a person is engaged in challenges that match their skills and when they clearly understand their proximal goals and can immediately analyze progress. Individuals who experience flow during a particular activity feel that the activity is intrinsically enjoyable and experience a sense of total immersion in it. They become completely focused on the activity, lose self-consciousness, and lose track of time [50,51,52]. Intrinsic motivation is a key element of the flow experience, so all flow-producing activities are intrinsically motivated [51].

Previous studies have shown that flow experience has a positive and significant influence on self-expressiveness [22,45,53]. For instance, shopping, which is typically considered a hedonically motivated experience, can also include intrinsic motivation elements such as flow as individuals become fully involved with it and lose track of time [22,52]. Additionally, flow experience gives individuals the perception that the activity is important for defining their true selves [22,53].

Given that slow tourism experiences such as those offered by the Trans-Siberian Railway are motivated by a desire to escape the daily routine, forget about the passage of time, feel fulfilled, and feel a sense of belonging to the environment and local culture [9], they are expected to have a high potential for flow experiences. Activities involved in Trans-Siberian train travel, such as playing games with fellow passengers, gazing out the train windows, and reading [32], can enhance the flow of the overall journey. Thus, considering the results of previous studies, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Flow experience with Trans-Siberian Railway travel is a positive predictor of self-expressiveness.

2.4. Self-Realization and Self-Expressiveness

According to eudaimonic identity theory, engaging in an activity that facilitates self-actualization can have a positive effect on self-expressiveness within that activity [22,45]. Self-realization involves a process of moving from one’s real self towards the ideal self [54]. Intrinsically motivated activities are believed to be aligned with the ideal self, which explains why people often see them as a means to move closer to their ideal selves [55]. As self-realization enhances self-expressiveness, individuals are more likely to be motivated to engage in such activities to achieve personally important goals [45], further increasing their self-expressiveness [22]. Empirical evidence has demonstrated the positive impact of self-realization on self-expressiveness for various activities, including shopping, dancing, and skiing [53,56].

Previous research on slow tourism goals and motivations, specifically motivations for Trans-Siberian travel, has highlighted self-expressiveness as one of the primary reasons for choosing slow travel [9,32]. Building on this literature, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Self-realization in Trans-Siberian Railway travel is a positive predictor of self-expressiveness.

2.5. Perceived Effort and Self-Expressiveness

Self-expressiveness within an activity is linked to the progress individuals make towards their ideal selves [22]. Unlike hedonic activities, intrinsically motivated activities involve not only enjoyment but also challenges and effort. When individuals do not face any challenges in an activity, they are more likely to perceive it as easy and become bored [51]. However, when an activity is perceived as challenging, people tend to become more interested in it and invest more time and effort in it [38,51]. In Waterman’s study [57], high-effort activities were found to have a greater impact on personal expressiveness than low-effort ones. Studies on self-expressiveness in sports tourism and shopping have also identified effort as an important predictor [53,56].

Slow tourists seek out alternative travel experiences that offer opportunities for self-development, which involves stepping outside of one’s comfort zone and facing challenges, thereby moving individuals closer towards their ideal selves [55]. Some respondents in Tihila’s study [32] mentioned that traveling on the Trans-Siberian Railway was a challenging experience, suggesting that Trans-Siberian travel can be considered a high-effort activity. Building on this discussion, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Effort in Trans-Siberian Railway travel is a positive predictor of self-expressiveness.

2.6. Perceived Authenticity and Self-Expressiveness

The concept of authenticity is crucial to understanding and explaining tourist motivations and experiences. According to MacCannell [58], the search for authenticity is the main driving force that motivates people to travel [59]. However, the meaning of authenticity is still a matter of debate, as it can be interpreted from philosophical, psychological, and spiritual perspectives [60]. Generally, authenticity in tourism is defined in three ways: objective, constructive, and existential [59].

The objective approach to authenticity is defined by Boorstin [59] and MacCannell [58] as the authenticity of originals, where tourists seek the experience of museum-linked objects that are found to be authentic [61]. On the other hand, constructivists argue that tourists seek symbolic authenticity that is shaped by society [61]. Finally, existential authenticity focuses on personal experiences and is divided into two dimensions: intra-personal, which involves bodily feelings of pleasure, relaxation, and spontaneity, and interpersonal, which involves self-making and knowing oneself [61].

Self-discovery and self-expressive experiences are important motivations for some people to travel [61,62,63]. The search for authenticity does not necessarily mean the quest for something exotic or primitive; it can also be achieved by experiencing the daily life of local people that differs from one’s everyday activities [63]. When engaged in non-everyday activities, individuals tend to perceive themselves as more authentic and more personally expressed [64].

Although the role of authenticity as the antecedent of self-expressiveness has not been tested empirically, authenticity is considered a core element of the eudaimonia concept [22,41,54]. Furthermore, authenticity is believed to be one of the central dimensions of slow tourism, which means that tourists who travel slowly are more likely to perceive their experience as authentic [2,5,30]. Based on the above views, we propose that perceived authenticity has a positive influence on self-expressiveness.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Perceived authenticity during Trans-Siberian Railway travel is a positive predictor of self-expressiveness.

2.7. Self-Expressiveness, Hedonic Enjoyment, and Life Satisfaction

Self-expressiveness and hedonic enjoyment represent two different perspectives of happiness from a philosophical standpoint, but they are intercorrelated concepts in social science [45]. Some scholars have suggested that the possibility of hedonic enjoyment being caused by eudaimonic variables is equivalent to the possibility of eudaimonia being caused by hedonia [65].

In this study, we propose that hedonic enjoyment is a positive contributor to self-expressiveness in the context of Trans-Siberian Railway travel experiences. First, Waterman and his colleagues [45] argued that self-expressiveness is not a necessary condition for increasing hedonic enjoyment, whereas hedonic enjoyment is a prerequisite for self-expressiveness. Furthermore, Ryan and his colleagues [38] have suggested that the main goal of research on eudaimonia is to explore what it means to live well and what outcomes such a life entails, including hedonic satisfactions. Pleasure is considered an essential human experience because it is a desirable condition that humans seek to achieve and because it contributes to other human functions [43]. Since individuals who have positive and enjoyable experiences are more likely to engage in self-expressive activities [21], we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Hedonic enjoyment during Trans-Siberian Railway travel has a positive impact on self-expressiveness.

As mentioned earlier, self-expressive activities have a greater impact on life satisfaction because they lead to both hedonic enjoyment and eudaimonia [22,40,45,66].

Engaging in self-expressive activities provides individuals with opportunities to give meaning to their lives, satisfy their basic psychological needs, and come closer to their ideal selves [66]. When individuals realize that they are involved in activities that move them toward their ideals, it positively affects their life satisfaction.

The positive feelings and emotions experienced during an activity spread to all aspects of life, resulting in a positive impact on life satisfaction [67]. Empirical studies have shown a significant positive relationship between self-expressiveness and life satisfaction, as well as between hedonic enjoyment and life satisfaction [53,56,67]. Therefore, based on previous studies’ results and the arguments presented above, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Self-expressiveness during Trans-Siberian Railway travel is a positive predictor of life satisfaction.

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Hedonic enjoyment during Trans-Siberian Railway travel is a positive predictor of life satisfaction.

2.8. Mediating Effect of Self-Expressiveness

Based on the previous literature, it is proposed that self-expressiveness has a mediating effect on the relationship between hedonic enjoyment and life satisfaction. This is because self-expressive activities not only lead to hedonic enjoyment but also contribute to eudaimonic well-being, which ultimately leads to greater life satisfaction [22,40,45,66]. Huta and Ryan [40] also found that while hedonic activities were positively correlated with positive affect and negatively correlated with negative affect at the individual level, self-expressive activities were not significantly correlated with either. However, at the interpersonal level, individuals involved in self-expressive activities had consistently higher life satisfaction than those who engaged in hedonic activities, which only had a temporary effect on life satisfaction. Therefore, it is proposed that self-expressiveness plays a mediating role in the relationship between hedonic enjoyment and life satisfaction.

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

Self-expressiveness mediates the relationship between hedonic enjoyment and life satisfaction.

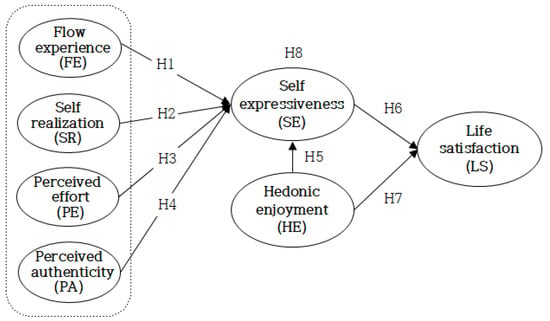

Based on the review of the literature, we present a research framework for hypothesis testing that schematically models the structural relationships between flow experience, self-realization, perceived effort, perceived authenticity, self-expressiveness, hedonic enjoyment, and life satisfaction, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The proposed research model.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Method

In accordance with the primary research objective, this study applies the self-expressiveness theory to the slow tourism context for Trans-Siberian Railway travel. This study delves into the effects of Trans-Siberian Railway tourists’ personal characteristics on life satisfaction via structural equation modeling (SEM). Notable is also the role that self-expression plays as a mediator between hedonic enjoyment and life satisfaction. Specifically, all CFA (confirmatory factor analyses) and SEM (structural equation modeling) investigations were conducted using the AMOS 25.0 software package. CFA was utilized to evaluate the measurement model, whereas SEM was employed to test the hypotheses. Finally, the mediating effects of self-expressiveness were evaluated using the bias-corrected (BC) bootstrap method procedure.

3.2. Measurements of the Variables and Survey Composition

This research’s variables were derived using the following approach: This study constructed a preliminary measurement scheme based on a comprehensive literature analysis and then fitted it to the framework of the slow tourism experience. The variables were categorized into seven major groups: (1) flow experience, (2) self-realization, (3) perceived effort, (4) perceived authenticity, (5) self-expressiveness, (6) hedonic enjoyment, and (7) life satisfaction. The first section consisted of four items measuring flow experience, which were adapted from Waterman et al.’s [45] research. Next, self-realization was made up of three items adopted from Waterman et al. [45] and Sirgy et al. [53]. The perceived effort section was made up of three items adopted from Waterman et al. [45]. To measure tourists’ perceived authenticity, four items were adopted from Kolar and Zabkar [68] and Zhou et al. [69]. The self-expressiveness section was made up of four items adopted from Waterman et al. [45]. Hedonic enjoyment was comprised of four items adopted from Waterman et al. [45]. Lastly, the life satisfaction section was composed of four items adopted from Pavot and Diener [70]. Four items were used to capture the sociodemographic information of the respondents: gender, age, country, and degree of education. Moreover, two additional measures examined travel characteristics related to general information about their travel experience with the Trans-Siberian Railway: previous travel experience to Russia and route. Except for sociodemographic and travel characteristics, the measurement items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree). We invited two experts in the field of slow tourism and requested that they review the survey items to confirm their validity.

3.3. Data Collection

The current study focused on the self-expressiveness experience of international tourists who were at least 16 years old, had taken the Trans-Siberian Railway from February to April 2017, and had spent more than two days on the train. Using a self-administered questionnaire (Appendix A: Table A1), data were collected via an online survey based on Instagram and Facebook. The survey link was sent to several hostels (Baikal Hostel and Irkutsk City Lodge, Irkutsk; Ulan-Ude Travelers House, Ulan-Ude; and Like Hostel, Novosibirsk) that are on the Trans-Siberian Railway route. A total of 215 responses were collected from 10 April to 5 May 2017. After removing incomplete responses and those insincere answers to any of the control questions, a final sample of 210 (a response rate of 97.7 percent) was subjected to the subsequent data analysis, as described below.

3.4. Data Analysis

When the surveys were collected, all data were coded in SPSS 22 format. The demographic profiles of the respondents and the general information regarding their experience were analyzed through descriptive statistics. The study used internal consistency reliability analysis to check whether measurement items were correlated to each other with Cronbach’s coefficient α [71]. The validity of construct measurement was verified with exploratory factor analysis (EFA), as it shows how well items are grouped together to determine the construct [72]. Multiple regression analysis was run to test the hypothesized relationships (H1–H8), as it can provide a clearer graphic picture of the relationship between several variables than other means can [73]. The mediating effects were evaluated using the bias-corrected (BC) bootstrap method [74]. In this research, 5000 bootstrapped samples were utilized to calculate the 95% BC confidence interval (CI).

The analysis of the data involved three processes. First, a CFA was conducted to evaluate the factor structure of each of the targeted variables in order to establish measurement model validity evidence. SEM was used to evaluate the structural correlations between the intended latent variables (i.e., flow experience [FE], self-realization [SR], perceived effort [PE], perceived authenticity [PA], self-expressiveness [SE], hedonic enjoyment [HE], and life satisfaction [LS]). As a final step, the mediating effects of self-expressiveness on the correlations between HE and LS were further gauged.

4. Results

4.1. Respondents’ Profile

According to Table 1, the proportion of female respondents (50.0%) and male respondents (50.0%) was equal. The dominant age range was below 20 (44.8%), followed by 20–29 (26.7%). The majority of respondents (73.8%) have a bachelor’s degree or higher. Europe accounted for 54.3% of the total respondents, followed by Asia (26.7%). In the case of their previous travel experience to Russia, this being their first time accounted for an overwhelmingly high proportion at 79.5%. The travel route with the highest percentage was the Trans-Siberian route (59.0%).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic profile and trip characteristics of the samples.

4.2. Full Measurement Model

A CFA was carried out for each of the seven dimensions (Table 2). The findings of the CFA indicate satisfactory model–data fit indices (e.g., χ2 (278) = 525.330 (p < 0.001), Q = 1.890; incremental fit index (IFI) = 0.918; Tucker–Lewis fit index (TLI) = 0.902; comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.916; standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.053; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.065). Moreover, all the standardized factor loadings ranged from 0.532 to 0.830, surpassing the minimum threshold of 0.50.

Table 2.

Confirmatory factor analysis results of the full measurement model.

The average variance extracted (AVE) by FE, SR, PE, PA, SE, HE, and LS was 0.454, 0.604, 0.545, 0.513, 0.624, 0.688, and 0.611, respectively. Although the AVE by FE was below the threshold of 0.50 [75], the loadings of this construct were nearly above 0.50 (FE: from 0.601 to 0.758) and significant at the p < 0.01 level. Jiang, Klein, and Carr [76] explain that measurement error can result in a variance that is larger than the variance captured by the relevant latent variable. Although the composite reliability of this latent variable is good, the AVE may still be less than 0.50 according to Fornell and Larcker’s [75] conservative criterion. In addition, the AVE by FE did not worsen the previously presented fit statistics. Examining the existing service research proves the findings for various factors with AVEs below 0.50 (e.g., [77,78,79,80,81]). Overall, the findings provided support for convergent validity.

All Cronbach’s alphas were larger than 0.70 (FE 0.766, SR 0.768, PE 0.818, PA 0.771, SE 0.842, HE 0.870, and LS 0.823) and values of composite reliability (CR) for all the constructs exceeded the criteria of 0.70, indicating satisfactory convergent validity.

Table 3 reveals that a number of correlation coefficients exceeded the square root of AVE. Thus, we measured the inter-factor correlation’s confidence interval [75]. When 1 is not present within the 95% confidence interval of correlation between two constructs, discriminant validity is verified [82]. For example, the highest correlation between self-expressiveness and life satisfaction (r = 0.900) was 0.814–0.986 of the 95% confidence interval, which confirmed discriminant validity.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity results.

4.3. Structural Model and Testing Hypotheses

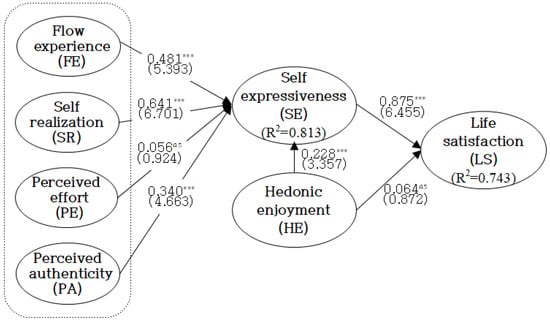

Figure 2 and Table 4 depict the outcomes of the SEM analysis of the structural model. This model’s chi-square value was 575.926 (p < 0.01) with 285 degrees of freedom. All fit indices were declared satisfactory (Q = 2.021, IFI = 0.903, TLI = 0.888, CFI = 0.901, SRMR = 0.060, and RMSEA = 0.070).

Figure 2.

The structural model testing results. Notes: Goodness of fit statistics: χ2 (285) = 575.926 ***, Q = 2.021, IFI = 0.903, TLI = 0.888, CFI = 0.901, SRMR = 0.060, RMSEA = 0.070. FM = Faith maturity, values not in parentheses are standardized parameter estimates; values in parentheses are t-values, *** p < 0.001, and ns—not significant.

Table 4.

Results of the structural model and tests of the hypotheses.

Except for PE (β PE → SE = 0.056, t = 0.924), the other three path coefficients from FE to SE (β FE → SE = 0.481, t = 5.393), from SR to SE (β SR → SE = 0.641, t = 6.701), and from PA to SE (β PA → SE = 0.340, t = 4.663) were significant and positive at the 0.001 alpha level, thus supporting Hypotheses 1, 2, and 4, respectively. These findings indicate that the more Siberian train tourists experienced FE, SR, and PA, the more they experienced SE. The path coefficient between HE and SE (β HE → SE = 0.228, t = 3.357) was likewise significant and positive at the 0.001 alpha level, indicating that the more HE Siberian train tourists encountered throughout their travels, the more SE Siberian train tourists experienced, validating Hypothesis 5. The results of the SEM analysis also provide empirical support for Hypothesis 6 because SE (β SE → LS = 0.875, t = 6.455, p < 0.001) had a significant and positive impact on LS. These findings show that those with a greater level of SE experience had a more positive outlook on their life satisfaction. However, HE (H7) did not have a significant effect on trust (β = 0.064, t-value = 0.872, n.s.), thus invalidating H7. The results explain 81.3 and 74.3 percent of the variance in SE and LS, respectively.

To further analyze the mediating effect of organizational legitimacy, we employed the bootstrap approach with a sample size of 5000 and a 95% confidence interval. Table 5 shows that the 95 percent confidence interval for self-expressiveness was (0.341, 0.782) and excluded zero, indicating that self-expressiveness mediated the effect of Hedonic enjoyment on life satisfaction; thus, H8 is supported. HE did not have a significant effect on LS. LS was significantly associated with SE. According to the judgment criterion of the mediating role suggested by Baron and Kenny [83], the results indicate that SE fully mediated the effect of HE on LS. In contrast to the direct effect (H7), the indirect effect of HE on LS was statistically significant. This may be due to the fact that the indirect effect might be portrayed as a shared outcome in which LS was strengthened by combining LS and HE.

Table 5.

Results of the bootstrap mediation test.

5. Discussion and Implications

Slow tourism is a form of alternative tourism that has garnered attention from academic researchers and tourism practitioners in recent years. Despite claims about the potential of slow tourism, the number of destinations branded as slow tourism destinations is still limited [2,6]. This study examined the Trans-Siberian Railway travel experience of international tourists from the perspective of slow tourism, applying eudaimonistic identity theory. The aim of this research was to analyze the process of self-expression formation during Trans-Siberian Railway travel and its influence on people’s life satisfaction. Previous studies by Caffyn [2] and Moore [1] support the positive impact of slow tourism on well-being. To achieve this purpose, a research model of self-expressiveness in slow tourism with eight hypotheses was proposed and tested. The positive (+) effect of flow experience, self-realization, perceived authenticity, and hedonic enjoyment on self-expressiveness was supported by Hypotheses 1, 2, 3, and 4. In addition, it was found that self-expressiveness positively affected life satisfaction (H6) and mediated the relationship between hedonic enjoyment and life satisfaction (H8). Nonetheless, as a result of the discovery that self-expressiveness played a full mediating function, hedonic enjoyment did not have a direct impact on the current level of life satisfaction. As a result, H7 was not supported. The majority of respondents were from countries in Europe (54.3%) and Asia (26.7%) that are geographically close to Russia. For most of the survey participants (79.5%), it was their first experience traveling to Russia.

Based on the results, the positive relationship between perceived effort and self-expressiveness, which had been reported in previous studies using eudaimonistic identity theory, was not supported. The mean score of perceived effort was relatively low compared to other variables, suggesting that international tourists do not view the Trans-Siberian Railway as a particularly strenuous experience. In contrast, flow, self-realization, and authenticity were found to positively predict self-expressiveness, which is in line with expectations. Tihila [32] also noted the language barrier between tourists and Russians as a factor hindering interaction. The significant correlations among self-expressiveness, hedonic enjoyment, and life satisfaction support the notion that slow tourism has a positive impact on well-being, life satisfaction, and personal happiness.

The present study has significant theoretical implications in the field of slow tourism. One of its major contributions is the application of eudaimonistic identity theory to the tourism context, which has previously only been applied in the leisure context [53,56]. The study found that self-expressiveness with the Trans-Siberian Railway experience can be predicted by flow, self-realization, and perceived authenticity. Unlike previous studies, perceived authenticity was proposed as the determinant of self-expressiveness. This study used Wang’s [61] concept of existential authenticity to measure tourists’ perceived authenticity of their experience. The results showed that tourists perceived their experience on the train as authentic because it was different from their daily activities, they felt closer to nature, and it positively influenced their self-expression.

Furthermore, this study showed with empirical data that the correlation between hedonic enjoyment and self-expressiveness is not always asymmetrical; hedonic enjoyment was found to be a positive contributor to self-expressiveness. However, it was found that hedonic enjoyment had no effect on quality of life. Hedonic adaptation theory was used to reject H7, which stated that hedonic enjoyment of Trans-Siberian Railway travel is a positive predictor of life satisfaction. According to the theory, even though individuals experience pleasure momentarily when their desires are gratified, the intensity of pleasure gradually diminishes over time as they experience the same degree of stimulation repeatedly. Brickman [84] proposed the hedonic adaptation theory, which asserts that humans are constantly pursuing greater pleasure but eventually adapt and return to their previous level of satisfaction. This explains why the results of this study indicate that the hedonic enjoyment felt by Siberian train tourists had no positive effect on their ultimate life satisfaction. Moreover, the study revealed the mediating role of self-expressiveness in the hedonic enjoyment-life satisfaction relationship. This suggests that tourists nowadays are more interested in having a meaningful experience that promotes self-development and self-improvement than just seeking hedonic satisfaction. Therefore, more research on self-expressiveness in different tourism contexts should be conducted.

An additional significant implication involves analyzing the Trans-Siberian travel experience through the lens of slow tourism. While Tihila [32] has previously studied Trans-Siberian Railway travel from a slow tourism perspective, her study primarily focused on tourist motivations rather than their experiences. This current study offers a more comprehensive examination of the experiences of tourists during their travels on the Trans-Siberian Railway. Specifically, it investigated the factors that influence their self-expressive formation, the benefits they derived from the trip, and the contribution of the journey to their overall life satisfaction.

The results of the present study have many practical implications. The managerial implications of the current study are directed at Russian tourism marketers. This research and previous research by Tihila [32] prove that the Trans-Siberian Railway can and should be promoted as a slow tourism experience. First, it can attract more tourists, as slow tourism is becoming a new trend [1,5]. Secondly, slow tourism, unlike mass tourism, brings benefits directly to the local markets [2,3,4,11]. Additionally, tourism promoters should not ignore the fact that self-expressiveness contributes a lot to people’s life satisfaction [53,56,85], and promoters should try to provide tourists with activities and experiences that can increase self-expressiveness.

Despite the potential contribution of this study to the existing literature, it is important to acknowledge several limitations. Future research on self-expressiveness within the tourism field should endeavor to improve the measurement scale and provide a clearer explanation of the correlations between all constructs. Specifically, a number of respondents reported difficulties with comprehending the measurement items due to variations in their understanding of the constructs as presented in the survey. Thus, a qualitative research approach may be necessary to gather detailed feedback from participants and enable them to express their experiences in their own words, which can ultimately inform the development of a more refined measurement scale for future research. The current study was developed based on Waterman’s eudaimonistic identity theory [22], which focused on the three determinants of self-expressiveness, namely effort, self-realization, and flow. These determinants were included in the model based on previous research findings on self-expressiveness in sports tourism [56], shopping [53], and Trans-Siberian Railway travel motivations [32]. However, other factors such as perceived difficulty, personal interest, and importance [56] may also influence self-expressiveness in the context of Trans-Siberian Railway experiences. Therefore, it is important to consider the potential impact of these factors in future studies on self-expressiveness in this field. Sirgy and colleagues [53] have also suggested that personality traits and cultural characteristics may serve as potential predictors of self-expressiveness. Additionally, the relationship between the constructs presented in the current model should be further examined, as authenticity, a non-original predictor of self-expressiveness, may have an impact on other determinants of self-expressiveness and hedonic enjoyment. The present study did not investigate the potential positive correlation between self-expressiveness predictors and hedonic enjoyment due to the relatively small sample size. Thus, future research with a larger sample size is needed to explore these relationships in more detail. Moreover, with the advancement of ICT technology [86,87], combining train travel and RFID technology in tourism research is regarded as a very fascinating topic.

Author Contributions

Methodology, H.R.; Conceptualization, O.K.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, O.K.; Analysis, H.R.; Writing—Review and Editing, R.H.; Supervision, R.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be obtained from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The data for our study came from the first author’s master’s thesis. All authors have consented to the acknowledgement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Research questionnaire.

Table A1.

Research questionnaire.

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither Agree Nor Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flow experience | □1 | □2 | □3 | □4 | □5 |

| 1. I felt I have clear goals. | □1 | □2 | □3 | □4 | □5 |

| 2. I lost track of time. | □1 | □2 | □3 | □4 | □5 |

| 3. I forgot personal problems. | □1 | □2 | □3 | □4 | □5 |

| 4. I felt I know how well I am doing. | □1 | □2 | □3 | □4 | □5 |

| Perceived effort | |||||

| 5. I put a lot of effort into this trip. | □1 | □2 | □3 | □4 | □5 |

| 6. I spent so much time on this trip. | □1 | □2 | □3 | □4 | □5 |

| 7. This trip was challenging for me. | □1 | □2 | □3 | □4 | □5 |

| Self-realization | |||||

| 8. The opportunity to realize the best I can be. | □1 | □2 | □3 | □4 | □5 |

| 9. The opportunity to achieve goals that are important in my life. | □1 | □2 | □3 | □4 | □5 |

| 10. The opportunity to develop my best potential. | □1 | □2 | □3 | □4 | □5 |

| Perceived authenticity | |||||

| 11. During the trip I felt connected with Russian people and their culture. | □1 | □2 | □3 | □4 | □5 |

| 12. I liked the calm and peaceful atmosphere during the visit. | □1 | □2 | □3 | □4 | □5 |

| 13. This trip provided me with experience that is totally different from my daily life. | □1 | □2 | □3 | □4 | □5 |

| 14. During the trip I felt in harmony with the nature. | □1 | □2 | □3 | □4 | □5 |

| Self-expressiveness | |||||

| 15. The Trans-Siberian Railway travel gave me the greatest feeling of really being alive. | □1 | □2 | □3 | □4 | □5 |

| 16. The Trans-Siberian Railway travel gave me my strongest feeling that this is who I really am. | □1 | □2 | □3 | □4 | □5 |

| 17. I felt a special fit or meshing when I was travelling by the Trans-Siberian railway. | □1 | □2 | □3 | □4 | □5 |

| 18. I felt more complete when I was travelling by the Trans-Siberian railway. | □1 | □2 | □3 | □4 | □5 |

| Hedonic enjoyment | |||||

| 19. This trip gave me my strongest sense of enjoyment. | □1 | □2 | □3 | □4 | □5 |

| 20. This trip gave me my greatest pleasure. | □1 | □2 | □3 | □4 | □5 |

| 21. During the trip I felt good. | □1 | □2 | □3 | □4 | □5 |

| 22. During the trip I felt happier than I do when engaged in most other activities. | □1 | □2 | □3 | □4 | □5 |

| Life satisfaction | |||||

| 23. I believe that in most ways my life is close to my ideal. | □1 | □2 | □3 | □4 | □5 |

| 24. I think that the conditions in my life are excellent. | □1 | □2 | □3 | □4 | □5 |

| 25. I believe that I am satisfied with my life. | □1 | □2 | □3 | □4 | □5 |

| 26. I can say that so far I have gotten the important things I want in life. | □1 | □2 | □3 | □4 | □5 |

References

- Moore, K. On the periphery of pleasure: Hedonics, Eudaimonics, and slow travel. In Slow Tourism: Experiences and Mobilities; Fullagar, S., Markwell, K., Wilson, E., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2012; Volume 54, pp. 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Caffyn, A. Advocating and implementing slow tourism. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2012, 37, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, D.; Timms, B.F. Re-branding alternative tourism in the Caribbean: The case for ‘slow tourism’. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2010, 10, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, J.E.; Lumsdon, L.M.; Robbins, D. Slow travel: Issues for tourism and climate change. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 281–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wearing, S.; Wearing, M.; McDonald, M. Slow’n down the town to let nature grow: Ecotourism, social justice and sustainability. In Slow Tourism: Experiences and Mobilities; Fullagar, S., Markwell, K., Wilson, E., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2012; Volume 54, pp. 36–50. [Google Scholar]

- Matos, R. Can slow tourism bring new life to alpine regions. In The Tourism and Leisure Industry: Shaping the Future; Weiermair, K., Mathies, C., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Murayama, M.; Parker, G. Fast Japan, slow Japan’: Shifting to slow tourism as a rural regeneration tool in Japan. In Slow Tourism: Experiences and Mobilities; Fullagar, S., Markwell, K., Wilson, E., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2012; Volume 54, pp. 170–184. [Google Scholar]

- Noor, F.A.M.; Nair, V.; Mura, P. Rail travel: Conceptualizing a study on slow tourism approaches in sustaining rural development. SHS Web Conf. 2014, 12, 01058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Assaf, A.G.; Baloglu, S. Motivations and goals of slow tourism. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintel. Slow Travel Special Report; Mintel International Group Ltd.: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, N. A Manifesto for Slow Travel; Hidden Europe Magazine: Berlin, Germany, 2009; Volume 25, pp. 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bandara, J.S. The impact of the civil war on tourism and the regional economy. South Asia J. S. Asia Stud. 1997, 20, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, E.; Gozgor, G.; Paramati, S.R. Do geopolitical risks matter for inbound tourism? Eurasian Bus. Rev. 2019, 9, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, D.M.; Katircioglu, S.; Adaoglu, C. The vulnerability of tourism firms’ stocks to the terrorist incidents. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1138–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailemariam, A.; Ivanovski, K. The impact of geopolitical risk on tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 3134–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, D.K.; Kumar, R. Russia-Ukraine War and the global tourism sector: A 13-day tale. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 26, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visit Russia, Russian National Tourist Office. Available online: http://www.visitrussia.org.uk/travel-to-Russia (accessed on 3 February 2017).

- Guinness World Records. Available online: http://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/longest-train-journey-without-changing-trains (accessed on 3 February 2017).

- LinkedIn, Russian Railways. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/company/russian-railways (accessed on 3 February 2017).

- Russian Railways. Available online: http://eng.rzd.ru/newse/public/en?STRUCTURE_ID=15&layer_id=4839&refererLayerId=3920&refererPageId=4110&id=107003 (accessed on 3 February 2017).

- Waterman, A.S. Reconsidering happiness: A eudaimonist’s perspective. J. Posit. Psychol. 2008, 3, 234–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, A.S. Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 64, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, A.S. Eudaimonic identity theory: Identity as self-discovery. In Handbook of Identity Theory and Research; Schwartz, S.J., Luyckx, K., Vignoles, V.L., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Parkins, W.; Craig, G. Slow Living; Berg Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Georgica, G. The Tourist’s Perception about Slow Travel–A Romanian Perspective. Procedia Econom. Bus. Adm. 2015, 23, 1596–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M. A Comparative Study based on Slow City Principles and Defining Slow Tourists Types. Kor. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2013, 22, 299–313. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, M. Slow Down. Available online: http://www.medibank.com.au/bemagazine/post/wellbeing/slow-down/ (accessed on 27 January 2017).

- Hall, C.M. Introduction: Culinary tourism and regional development: From slow food to slow tourism? Tour. Rev. Int. 2016, 9, 303–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumsdon, L.M.; McGrath, P. Developing a conceptual framework for slow travel: A grounded theory approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woehler, K. The rediscovery of slowness, or leisure time as one’s own and as self-aggrandizement? In The Tourism and Leisure Industry: Shaping the Future; Weiermair, K., Mathies, C., Eds.; The Haworth Hospitality Press: London, UK; Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Camargo, B.A.; Garza, C.G.; Morales, M. Railway tourism: An opportunity to diversify tourism in Mexico. In Railway Heritage and Tourism; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2014; pp. 151–165. [Google Scholar]

- Tihilä, K. Taking it Slow on the Trans-Mongolian Railway-or Not? A Case Study on Slow Travel and Tourist Experience. Master’s Thesis, Helsinki University, Helsinki, Finland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bagnoli, L. Slow tourism and railways: A proposal for the Italian-French Roia Valley. Dos Algarves. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2016, 27, 120–136. [Google Scholar]

- Dallen, J. Sustainable transport, market segmentation and tourism: The Looe Valley branch line railway, Cornwall, UK. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 180–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Way to Russia. Available online: http://waytorussia.net/TransSiberian/ (accessed on 10 February 2017).

- Trans-Siberian Express. Available online: https://www.transsiberianexpress.net/?gclid=CK_h193q89ICFRRvvAodRTcNHg (accessed on 10 February 2017).

- Kahneman, D.; Diener, E.; Schwarz, N. Well-Being: Foundations of Hedonic Psychology; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tännsjö, T. Narrow hedonism. J. Happiness Stud. 2007, 8, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huta, V.; Waterman, A.S. Eudaimonia and its distinction from hedonia: Developing a classification and terminology for understanding conceptual and operational definitions. J. Happiness Stud. 2014, 15, 1425–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B.H. Know thyself and become what you are: A eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2008, 9, 13–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.; Park, N.; Seligman, M.E.P. Orientations to happiness and life satisfaction: The full life versus the empty life. J. Happiness Stud. 2005, 6, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, L.A.; Hicks, J.A.; Krull, J.L.; Del Gaiso, A.K. Positive affect and the experience of meaning in life. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 90, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological wellbeing. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, A.S.; Schwartz, S.J.; Conti, R. The implications of two conceptions of happiness (hedonic enjoyment and eudaimonia) for the understanding of intrinsic motivation. J. Happiness Stud. 2008, 9, 41–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, L.A. Interventions for enhancing subjective well-being: Can we make people happier and should we? In The Science of Subjective Well-Being; Eid, M., Larsen, R.J., Eds.; Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 431–448. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Lehto, X.Y.; Cai, L. Vacation and well-being: A study of Chinese tourists. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 42, 284–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettema, D.; Gärling, T.; Olsson, L.E.; Friman, M. Out-of-home activities, daily travel, and subjective well-being. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2010, 44, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M.; LeFevre, J. Optimal experience in work and leisure. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 56, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow and the Foundations of Positive Psychology; Springer: Berlin, Germany; Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Finding Flow: The Psychology of Engagement with Everyday Life; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, D.L.; Novak, T.P. Marketing in Hypermedia Computer-Mediated Environments: Conceptual Foundations. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Lee, D.J.; Grace, B.Y.; Gurel-Atay, E.; Tidwell, J.; Ekici, A. Self-expressiveness in shopping. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 30, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Can. Psychol. 2008, 49, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiver, J.; McGrath, P. Slow Tourism: Exploring the discourses. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 27, 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosnjak, M.; Brown, C.A.; Lee, D.J.; Yu, G.B.; Sirgy, M.J. Self-expressiveness in sport tourism: Determinants and consequences. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, A.S. When effort is enjoyed: Two studies of intrinsic motivation for personally salient activities. Motiv. Emot. 2005, 29, 165–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCannell, D. Staged authenticity: Arrangements of social space in tourist settings. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 79, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boorstin, D. The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America; Political Science; Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 2012; p. 336. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, C.J.; Reisinger, Y. Understanding existential authenticity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N. Rethinking Authenticity in tourism experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepp, A.; Gibson, H. Tourist roles, perceived risk and international tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 606–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Geographical consciousness and tourism experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 863–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, K. Authenticity as a concept in tourism research: The social organization of the experience of authenticity. Tour. Stud. 2002, 2, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashdan, T.B.; Biswas-Diener, R.; King, L.A. Reconsidering happiness: The costs of distinguishing between hedonics and eudaimonia. J. Posit. Psychol. 2008, 3, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Huta, V.; Deci, E.L. Living well: A self-determination theory perspective on eudaimonia. J. Happiness Stud. 2008, 9, 139–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.J.; Sirgy, M.J.; Grace, B.Y.; Chalamon, I. The well-being effects of self-expressiveness and hedonic enjoyment associated with physical exercise. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2015, 10, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolar, T.; Zabkar, V. A consumer-based model of authenticity: An oxymoron or the foundation of cultural heritage marketing? Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 652–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.B.; Zhang, J.; Edelheim, J.R. Rethinking traditional Chinese culture: A consumer-based model regarding the authenticity of Chinese calligraphic landscape. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavot, W.; Diener, E. The satisfaction with life scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. J. Posit. Psychol. 2008, 3, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, P. An Easy Guide to Factor Analysis; Routledge: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Babbie, E. The Basics of Social Research; Cengage Learning: Wadsworth, OH, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Meth. Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.J.; Klein, G.; Carr, C.L. Measuring information system service quality: SERVQUAL from the other side. MIS Q. 2002, 26, 145–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Ozturk, A.; Kim, T.T. Servant leadership, organisational trust, and bank employee outcomes. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 39, 86–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, F.; Augusto, M. Job characteristics and the creativity of frontline service employees. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koburtay, T. Guests’ happiness in luxury hotels in Jordan: The role of spirituality and religiosity in an Islamic context. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 23, 987–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Huang, K.; Shen, S. Are tourism practitioners happy? The role of explanatory style played on tourism practitioners’ psychological well-being. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Yan, S.; Wang, J.; Xue, Y. Flow Experiences and Virtual Tourism: The Role of Technological Acceptance and Technological Readiness. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Assumptions and comparative strengths of the two-step approach: Comment on Fornell and Yi. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 20, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brickman, J.; Campbell, D.T. Hedonic relativism and planning the good society. In Adaptation Level Theory; Appley, M.H., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Trang, N.T.; Yoo, J.J.E.; Joo, D.; Lee, G. Incorporating senses into destination image. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2023, 27, 100760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaby, O.; Hamadache, M.; Soper, D.; Winship, P.; Dixon, R. Development of a novel railway positioning system using RFID technology. Sensors 2022, 22, 2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotny, Á.; Dávid, L.; Csáfor, H. Applying RFID technology in the retail industry–benefits and concerns from the consumer’s perspective. Amfiteatru Econ. J. 2015, 17, 615–631. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).