Abstract

The historic urban landscape (HUL) is the result of the continuous dynamic process of production, interaction, and accumulation. It is full of information from bygone years and remains to this day as a living witness of antiquity and a benefit to the contemporary public, both in mind and spirit. These intangible benefits, however, are easier to overlook than the tangible ones in conservation and management efforts that aim at sustainability. Therefore, we return to the prototype of the category “cultural services” in the ecosystem classification “information service” to evaluate these intangible benefits. The objectives of this study are: (1) to provide a methodological framework to assess the ability of the landscape to continuously provide information services in the historical process; (2) to analyze the drivers affecting HUL’s ability to continuously deliver information services, and then discuss the governance experience of HUL’s intangible dimensions for sustainability. First, we regard HUL as an object to learn from the experience of urban heritage governance: using the methods and tools of ecosystem service evaluation, this paper evaluates the intangible services that the public receives from the landscape over several consecutive historical periods, summarizes the dynamic changes in these services, and analyzes their drivers. Furthermore, we consider that the aforementioned intangible services are brought about in part by the spread of heritage information stored in HUL among specific people, and the continuous provision of information services is considered the sustainability of HUL in intangible dimensions. We use Yuexiu Hill in the center of Guangzhou, China, as a case study to verify the feasibility of our methodological framework by evaluating the information services provided by this ancient area with a construction history of 2000 years over five historical periods. The data needed for the evaluation of the information service was obtained through text mining by retrieving 1063 ancient Chinese poems related to Yuexiu Hill from the poetry database. The results obtained through this evaluation framework will provide a quantitative basis for planning, design, and decision making in small and medium-sized landscapes.

1. Introduction

How best to cope with the changes brought about by rapid urbanization and industrialization in order to maintain and promote human well-being is a current challenge for urban heritage conservation and management. Efforts are being made all over the world to preserve the regional diversity and value of cultural landscapes and their underlying land use practices while, at the same time, seeking to guide landscape changes along sustainable pathways [1] (p. xiv). However, the intangible dimensions of heritage are easier to overlook than the tangible ones, and the intangible values (individual, social, and institutional) are gradually vanishing with the loss of the meaning of urban spaces. According to the Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape, knowledge and planning tools should help protect the integrity and authenticity of the attributes of urban heritage. They should also allow for the recognition of cultural significance and diversity and provide for the monitoring and management of change to improve the quality of life and urban space. Heritage, social, and environmental impact assessments should be used to support and facilitate decision-making processes within a framework of sustainable development [2] (Para. 24).

By focusing on the dynamics of ecosystem services, general sustainability goals can be translated into more specific operations. The concept of “service” seems to be an extremely apt bridging concept that links landscape patterns, ecosystem services, aesthetics, values, and decision making through a “structure–function–value chain” [3]. On the one hand, it helps to integrate the tangible and intangible attributes of historic landscapes in order to evaluate the various benefits that the public derives from cultural landscapes [4,5]. On the other hand, it helps to understand the dynamic links between landscape and human well-being in the evolution of historic landscapes and to draw lessons from historic landscapes to achieve the sustainable management of landscapes [6,7]. Therefore, we combine the approaches of ecosystem services valuation and the historic urban landscape and use information services, a type of ecosystem service, to measure the intangible benefits of historic urban landscape to the public.

Information services are intangible services within the framework of the ecosystem services classification, focusing on the process of the transmission of information between landscapes and people. “Information services” is the prototype of “cultural service” but is not as widely used as “cultural service” [8]. This study advocates a return to the concept of “information services” in order to essentially reveal the reasons for the continuity of the historic urban landscape during its evolution.

De Groot [9] (p. 120) reveals the essential relevance of environment information to human well-being in terms of ecosystem function, stating that natural or semi-natural ecosystems contribute to the maintenance of psychological health by providing opportunities for reflection, spiritual enrichment, cognitive development, and aesthetic experience. Several types of information were listed in Functions of Nature [9] (pp. 120–128): aesthetic information, spiritual and religious information, historic information, cultural and artistic inspiration, and educational and scientific information. The essence of ecosystem services is the flow of materials, energy, and information from the natural capital stock between nature and human society, and these flows are combined with manufacturing and human capital services for human well-being [10]. The intangible well-being that historic urban landscape provides to the public is the result of the flow of information about the historic environment stored in the historic landscape, in historic materials, and in the public’s shared knowledge, that is, “information services” under the ecosystem service classification. The sustainability of historic urban landscape is, in part, the continuous provision of such intangible services in the temporal dimension.

Our review of charters related to the conservation of historical and cultural heritage reveals that information plays an essential role in heritage conservation. The authenticity of information sources and the recording and dissemination of information about the historic environment are key to heritage conservation [11,12]. Historic urban spaces provide an emotionally nourishing environment, which is related to the information field generated by the surrounding surfaces and how easily the information can be received by pedestrians [13]. Interactive communication and the participation of the communities involved are not only the most effective ways to preserve, use, and enhance the spirit of heritage places [14], but are also closely linked to human well-being [15,16]. The effect of the promotion of all kinds of information listed by De Groot on human well-being is more prominent in the HUL. This paper returns to the term “information services” rather than “cultural services” because “information” and its related concepts (such as “information flow” and “information entropy”) can be measured quantitatively, and “information service” is more convenient to identify and quantitatively evaluate the intangible services provided by the historic urban landscape from the perspective of information transmission. In summary, information services can be seen as a more specific and direct means of evaluating cultural services in the context of historic urban landscape.

According to the characteristics of historic urban landscape information storage and dissemination, we have expanded the indicators of historic urban landscape information services based on the classification of information services by De Groot [17,18]. The new classification (Table 1) refers to the indicators of cultural services in Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) [19] to maintain consistency of terms.

Table 1.

Classification of HUL information services.

Sustainability of the landscape means the sustainable provision of ecosystem services [21,22]. Selman [23] extended the above concept to the cultural landscape and believed that the difference between the sustainable cultural landscape and natural landscape is “the ability to reproduce its form, function and significance at the same time”. Whether to continue to provide material or spiritual benefits for the public is the key to the sustainable development of the cultural landscape. Similarly, dealing with the complexity of contemporary cities and maintaining the sustainability of the tangible and intangible attributes of heritage is the core of the HUL approach. Referring to the concept of “landscape sustainability” [22], this paper takes the ability to continuously provide landscape services as a yardstick to measure the continuity of the tangible and intangible attributes of the historic urban landscape. The continuity of “information service” is used to evaluate whether the intangible attribute of the historic urban landscape is sustainable.

Although great progress has been made in the evaluation, quantification, and mapping of relevant service types in previous research [6,24,25], it is still a challenge to implement relevant methods in the planning and management of sustainable historic urban landscape. We can obtain relevant information about the public and landscape from different art forms (such as music, poetry, and serial game arts) [26] and identify intangible services from these tangible manifestations [5]. In addition, landscape characteristics and spatial information are crucial in heritage preservation and management [27]. The use of information with spatial data should be considered for the evaluation of intangible services [28].

Using the types of materials and analysis methods mentioned above, this paper will test three assumptions: (1) the continuous provision of information services reflects the sustainability of historic urban landscape in its intangible dimension; (2) text mining of cultural activity related data from historical records is an effective way to assess the ability of landscapes to provide information services over the course of history; (3) the ability and type of information services provided by historic urban landscape are affected by public demand and depend on the clear communication of heritage information. The historic urban landscape of Yuexiu Hill in Guangzhou, China, with a construction history of 2000 years, is a suitable case study to validate our methodology framework.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

Yuexiu Hills is a hilly area north of the ancient city of Guangzhou in China. For over 2000 years (since 214 B.C.), the site of ancient Guangzhou remained unchanged, and the landscape pattern remained stable: continuous hills extended from the north to the center of the city, and watercourses on the hills flowed through the city and southward into the Pearl River.

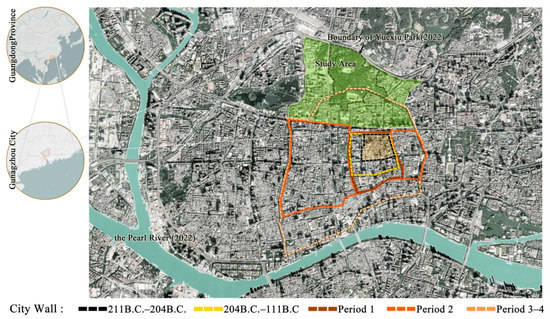

Yuexiu Hill HUL provides a complete sample for the study of the sustainability of the historic urban landscape. Its evolution is closely related to the construction of the ancient city of Guangzhou. The original Yuexiu Hill is a group of natural hills running northeast to southwest. As it is impossible to define its boundaries, we have mapped the general geographical extent based on archaeological data and contemporary road layouts (Figure 1), covering an area of approximately 5110 square meters. The southern foot of Yuexiu Hill was incorporated into the city walls after the urban expansion in the Ming Dynasty and became the most prominent part of the ancient city of Guangzhou in the Qing Dynasty [29]. By the Qing Dynasty, Yuexiu Hill had become the “main Hill” of Guangzhou, occupying a central position in the north of the city. Yuexiu Hill has played the role of holy hill, scenic resort, royal garden, urban landmark, and urban park in the public’s cognition of different historical periods. During the lengthy historical process, it has gradually become the core area of cultural activities in the north of the city, from the “hill outside the city” [30]. With the gradual expansion of the ancient city of Guangzhou to the north, the number of buildings and structures in the Yuexiu Hill HUL has increased, while the coverage of green space has gradually decreased, which has also affected the provision of ecosystem services.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the study area and Guangzhou ancient city wall expansion in different periods.

To facilitate the study of the dynamics of information services provided during the evolution of the Yuexiu Hill HUL, we have divided the historical timeline into five stages of development, Period 1–Period 5, based on the spatial relationship between the ancient city of Guangzhou and Yuexiu Hill (Table 2).

Table 2.

Historical period division.

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. Research Framework

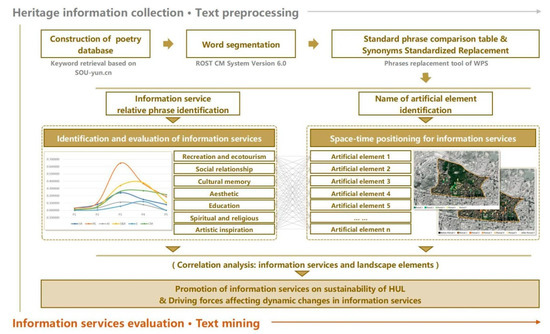

This study collected poems describing Yuexiu Hill in China as information sources and applied text mining methods to analyze the corresponding poetry texts of the five periods separately to extract the data needed for information service evaluation. This study primarily focuses on the following two aspects: the first is to analyze the dynamic changes of various information services in the long-term dimension; the second one is to determine the spatial and temporal distribution of information services through specific artificial elements of HUL. Finally, the analysis of the correlation between the two will reveal the relevance of information services to physical elements and the driving forces that influence the dynamic changes in information services. The research framework is shown in (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Framework of research.

2.2.2. Yuexiu Hill Poetry Database

The collection of relevant information allows for the description, prediction, or evaluation of changes in ecosystem services across attributes [31], with the availability, utilization, and authenticity of information sources being of primary concern during the evaluation process. For the above considerations, we chose to obtain heritage information related to the material elements of the landscape and cultural activities of the Yuexiu Hill HUL from the poems of previous dynasties. As a literary genre, Chinese classical landscape poetry records rich heritage information, such as cultural activities, landscape elements, and spatial locations [32]. Landscape poetry carries the simple ecological views of ancient Chinese communities and reflects the simple ecological ideas, sustainable development consciousness, and corresponding vision of the time. The development of the digital humanities has led to the establishment of a variety of literary and historical databases that can be accessed via the web. These databases provide content descriptions and available information on the year of publication of the works [33].

We searched the “SOU-yun.cn” (last visited on 10 September 2022) system for poems referring to Yuexiu Hill and various historical sites in the Hill to establish an ancient poetry database for Yuexiu Hill. “Souyun” is the most complete online database of ancient Chinese poetry, which contains 900,000 ancient Chinese poems created over approximately 2000 years, providing full-text retrieval, authors, creation time, and other information. We refer to the names of historical sites (including the nicknames of various historical sites in different periods) provided in the list of historical sites in the appendix of Thousands of Years of Yuexiu Hill for poetry retrieval to ensure the integrity of the source information. A total of 1063 poems written between 581 and 1949 were retrieved, reflecting the common understanding of specific people on Yuexiu Hill during this period. These poems have provided information source support for the analysis of the sustainability of the information services provided by Yuexiu Hill HUL. A total of 29 historic sites in Yuexiu Hill are mentioned in these poems.

2.2.3. Pre-Processing of Poetry Text Data

The 1063 poems we collected were filtered to remove redundant information, and only the title and body of the poems were retained, which were stored as original text in the format of “*. txt”. The poetry text was then preprocessed as follows:

We performed word segmentation on poetic texts to provide word frequencies of various phrases as information service data. This process includes four steps: pre segmentation, standard phrase replacement, precise segmentation, and the division of “*. txt” text in five periods. First of all, we used the word segmentation tool ROST Content Mining System Version 6.0 (a digital humanities assistant research platform designed and coded by Wuhan University, Wuhan, China) to pre-segment the original text. We found that the presence of a large number of synonyms increases the difficulty of word frequency statistics. To solve this problem, we grouped the phrases with the same meaning and obtained 36 groups of standard phrases related to information services (Table 3). Then, we used the batch replacement tool WPS to replace all synonyms in the original text with all standard phrases in Table 3 (for example, the standard phrase “赋诗” is used to replace synonyms such as “作诗”, “诗文”, and “新诗” in the full text), and received a “standardized text”. After that, we again used the ROST CM version 6.0 word segmentation tool to segment the text more accurately. For example, “越井岗头松柏老, 越王台上生秋草” (meaning “the pines and cypresses at the head of the Yuejing hillock are old, and autumn grass grows on the Yuewang Platform”) was segmented into “越井/岗头/松柏/老, 越王台/上/生/秋草”. Finally, we sorted the poems according to the creation age corresponding to the five development periods of Yuexiu Hill HUL so as to divide the segmented text into five “*. txt” texts and number them according to TEXT 1–5. Each poem in the text is an independent and continuous paragraph.

Table 3.

Comparison table of standard phrases in information services.

2.2.4. Evaluation of Information Service Indicators of Yuexiu Hill HUL

To characterize the dynamic changes in the historical process of the ability of Yuexiu Hill HUL to provide various information services, we used the annual average frequency of each service-related phrase. We used the word frequency statistics tool ROST CM Version 6.0 to identify and count the frequency of various phrases related to information services in the poetry texts of five periods (Table 4), referring to the “Yuexiu Hill HUL Information Service Standard Phrase Table”. Then, we calculated the annual average frequency of each service-related phrase based on the length of five periods (Table 2) and used the sum to obtain the values of the corresponding periods of six types of services (Table 5).

Table 4.

Frequency of phrases related to cultural activities in poetry.

Table 5.

Various information services corresponding to five historical periods.

2.2.5. Hotspot Distribution in Historical Time and Space of Yuexiu Hill HUL Information Services

To clarify the spatial and temporal distribution hotspots of Yuexiu Shan’s HUL information service, we identified the artificial landscape elements that appear in the poetry database and classified them into seven categories. We then counted the sum of word frequencies (Fiz) of the seven groups of artificial elements in the poetry texts for each period separately and converted them into annual average frequencies (Siz) (Table 6). The Siz corresponding to the five historical periods reflect the changes in the ability of each type of artificial element to provide information services over the time interval of this study (Table A1).

Table 6.

Frequency of artificial landscape element names in poetry texts of each period.

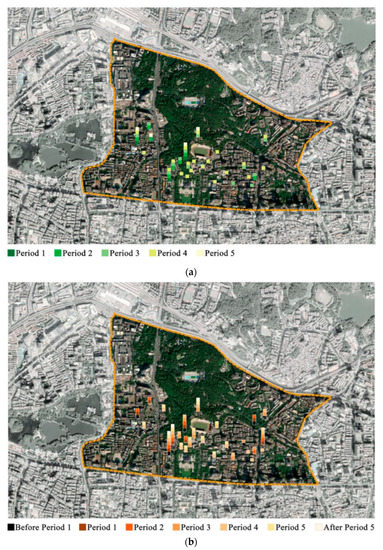

In addition, the presence of an element name in a poem is considered as if the element provided an information service during the corresponding period. We marked the time when each element continuously provided information services in Figure 3a. Then, we found the time of the construction and destruction of the above landscape elements from the historical data and marked the time of the physical existence of the elements in Figure 3b. The two figures compare and analyze whether the time when the landscape elements provided information services matches the time when the physical entities of the elements existed.

Figure 3.

(a) Information service time and spatial hotspot distribution. (b) The temporal and spatial distribution of the physical entity of the ancient sites mentioned in the Yuexiu Hill Poetry Database.

2.2.6. Correlation Analysis of HUL Information Services and Artificial Elements in Yuexiu Hill

Using the Shapiro–Wilk test (Table A2), the data corresponding to the six categories of information services and the seven categories of landscape elements all satisfy a normal distribution. Using IBM SPSS Statistics 26 software, we conducted Pearson Correlation Analysis on the various information services (SRi, REi, AIi, S and Ri, Ei, and CMi) provided by Yuexiu Hill HUL with each of the seven groups of artificial elements (Siz), so as to clarify the relationship between various information services and different types of artificial elements entities. The results of the analysis are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Correlation analysis of the information services and artificial element types of the Yuexiu Hill HUL.

3. Results

3.1. Continuity and Diversity of Yuexiu Hill HUL Information Services

All kinds of information services provided by Yuexiu Hill HUL show continuity in time and diversity in terms of type within the time range of the study (from Period 1 to Period 5).

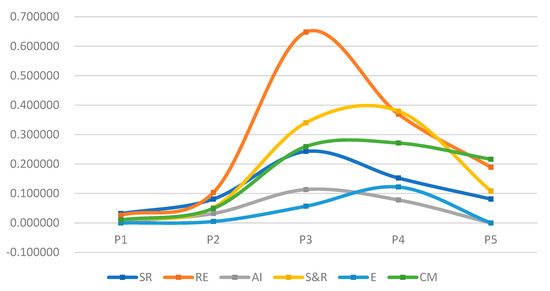

By extracting high-frequency phrases related to information services from poetry texts, we identified six types of information services and calculated the values of each type of service in five historical periods (Table 5). The contents of Table 5 are presented in the form of a line chart (Figure 4) to allow the dynamic changes in various services of the landscape evolution process to be observed. The results show that the provision of six types of information services is not constant, and they experienced rapid growth during the early stages of the development of Yuexiu Hill HUL. However, the six types of information provided by Yuexiu Hill HUL do not exist independently, and there is a certain positive correlation between various services (Table 3). There is a significant correlation between recreation and ecotourism, social relations, and artistic inspiration, which reached its peak in Period 3 (the Ming Dynasty), while the growth of spiritual, cultural memory, and education services lagged behind the other three types of services, reaching a peak in Period 4 (the Qing Dynasty). After Period 4, all information services began to decline. Moreover, artistic inspiration and educational services were at zero in Period 5. While the remaining four types of services continued to be offered, they also showed a significant downward trend.

Figure 4.

Comparison of information services provided by Yuexiu Hill HUL in different historical sections.

3.2. Time Mismatch between Information Services Provided by Artificial Elements and Their Existing Physical Entities

Yuexiu Hill HUL has undergone more than 2000 years of evolution, accompanied by the disappearance of old elements and the emergence of new ones. Figure 3a,b shows that the time of existence of each artificial element does not exactly match the time at which its name appears in poetry texts, that is, the time of existence of the artificial element does not exactly match the time when it provides information services. The situation is threefold:

(1) The duration of the continuous provision of information services exceeds the duration of the existence of the physical entity of artificial elements, such as Chaohan Platform and Huluan Path. The Chaohan Platform was built in the Nanyue Period (204 B.C.–111 B.C.) and was built at the same time as the Yuewang Platform. It represents the earliest artificial group of elements in Yuexiu Hill. Although its physical substance disappeared before Period 1, it is mentioned in poetry from the first to the fifth. Huluan Path was built in the Nanhan Period (917 A.D.–971 A.D.) and fell into disuse in the second period, but its name still appears in the poems of Period 3 and Period 4. The information services provided by these elements continued after the disappearance of their physical entities;

(2) The duration of continuous information services coincides with the existence of the physical entity of the artificial element and continues to this day. Since their construction, these elements have been a popular subject for poetry. After multiple reconstructions, sites and features, such as the Yuewang Platform and the Zhenhai Tower, have been preserved. The Yuewang Platform is the most frequently seen historic site in the Yuexiu Hill Poetry Database. It was damaged before Period 1 and was rebuilt during Period 1 and Period 2. A monument built on its site in 1930 has been preserved. Zhenhai Tower, built during Period 3, has become another hotspot after Yuewang Platform. After several renovations, it has taken on military, recreational, and other functions, and is now the Guangzhou Museum. The information services provided by these elements continue after their physical entities are destroyed and rebuilt;

(3) The duration of continuous information services coincides with the existence of the physical entity of artificial elements that have been terminated, such as Bushi Temple, Taiquan Academic, North Garden, Xuehai Academic, Zhaozhong Ancestral Hall, Sanjun Temple, Yingyuan Academy, Yixiu Garden, Xiyan Spring, Banshan Pavilion, Hongmian Temple, Ji Garden, Jupo Academic, etc. These elements were built in Period 3 and Period 4, meeting the specific functional needs of the public in a short period of time. The information services provided by these elements are only provided when their physical entities exist.

3.3. Impact of Land Cover Change on Spatial Distribution of Information Services in Yuexiu Hill HUL

The expansion of the ancient city has affected the land use and land cover of the Yuexiu Hills area, further affecting the spatial distribution of information services. The development of the landscape of Yuexiu Hill and the construction of the ancient city of Guangzhou began around the same time, 211 B.C.–111 B.C. The ancient city has undergone several expansions over the past 2000 years. Each expansion, centered on the original ancient city and extending into the surrounding areas, was accompanied by a reduction in the green area of Yuexiu Hill and the expansion of the artificial construction area. Due to the lack of historical data, we were unable to accurately map the spatial scope of Yuexiu Hill in various historical periods, while the Guangzhou city wall continued to expand, which reflected the change and time depth of land use in Yuexiu Hill (Figure 3a). We compared the changes in land use of Yuexiu Hill HUL (Figure 1) with the spatio-temporal distribution hotspots of information services (Figure 3a) and found that, with the expansion of the artificial construction area, the distribution density of information services increased first and then decreased.

Periods 1 and 2 were the early stages of the development of Yuexiu Hill HUL. In the early stages of the construction of the ancient city of Guangzhou, Yuexiu Hill was spatially separated from the city. There are no large-scale man-made structures in the Yuexiu Hill area, and the natural hills dominate the landscape. In Period 1, as the private domain of the local ruler, only three information service hotspots were identified from the poetry database (Figure 3a). During Period 2, the ancient city of Guangzhou was expanded to the north and south, and Yuexiu Hill was still a suburb outside the city wall. During that time, the number of information service hotspots increased to only seven (Figure 3a).

During Period 3 and the beginning of Period 4, the development of Yuexiu Hill HUL flourished. During this time, Guangzhou City and Yuexiu Hill HUL showed an “intersect” relationship in space, and the natural landscape and artificial landscape reached a balance at this stage. During Period 3, the city wall was extended to the southern foot of Yuexiu Hill (south of Zhenhai Tower). Since then, many artificial landscape elements have been built in the hilly areas within the city walls. In Period 3, 13 information service hotspots were identified (Figure 3a), and in Period 4, 20 hotspots were identified (Figure 3a). At the end of Period 4, however, the provision of information services has entered a recessionary period. During this period, many streets and alleys were built at the southern foot of Yuexiu Hill. In the study area, there are 1677 streets and alleys south of the city wall [34] (p. 118), forming high-density blocks.

In Period 5, the urban area of Guangzhou expanded again in 1923, and the northern boundary was beyond the scope of Yuexiu Hill, showing a spatial “inclusion” relationship with Yuexiu Hill. In the early Republic of China, excessive logging and the outbreak of many wars seriously damaged the vegetation cover of Yuexiu Hill [34] (p. 123). In 1918–1922, the wall was demolished and the municipal road was built on its site. Subsequently, the main part of Yuexiu Hill was demarcated as the scope of the park. Despite the construction of schools, hospitals, administrative institutions, libraries, and other buildings in the southern part of Yuexiu Hill during this period, only four information service hotspots were identified (Figure 3a), a significant reduction from the previous two periods.

3.4. The Impact of Changes in Artificial Landscape Elements on Various Information Services

The Pearson correlation analysis (Table 7) of the various types of information services provided by Yuexiu Hill HUL (SRi, REi, AIi, S and Ri, Ei, and CMi) with each of the seven groups of artificial elements (Siz) revealed that there were differences in the capacity and type of information services provided by different types of landscape elements. The construction of these elements at different periods explains the dynamic changes in the information services associated with them:

The artificial elements that appear in Period 1 poetries are predominantly of the platform type (e.g., Yuewang Platform, Chaohan Platform), which are positively associated with social relations, recreation and ecotourism, spirit and religion, and cultural memory (Table 7). However, the initial level of the five types of services is low, being 0.0317, 0.0265, 0.0053, 0.0106, and 0.0106, respectively (Table 5). In Period 2, Yuexiu Hill was still a hilly country in the north of the city. Most of the scenic spots on the hill were left over from the previous period, and the six types of services only increased slightly compared with the previous period (Table 5). The towers (Zhenhai and Weituo Towers) built in Period 3 were significantly related to recreation and ecotourism, social relations, and artistic inspiration (p < 0.05 **) (Table 7). The construction of them further promoted the provision of the above three services and reached a peak in Period 3 at 0.647802429 and 0.1134, respectively (Table 5). The newly built academies (Yingyuan Academy, Xuehaitang Academy, Jupo Academy, and so on) and Hongmian Temple in Period 4 were significantly related to education services (p < 0.05 **) (Table 7), and education services reached a peak in this period, E4 = 0.1220 (Table 5). In addition, spirit and religious and cultural memory also reached a peak in Period 4, at 0.3800 and 0.2712, respectively (Table 5), probably influenced by the new ancestral halls and private gardens (Yixiu Garden, Ji Garden). The construction of the artificial elements mentioned above has strengthened the capacity of Yuexiu Hill HUL to provide information services.

However, as seen in Table 6, a large number of artificial elements were destroyed during Period 5, and large-scale artificial construction and the outbreak of multiple wars significantly altered the landscape character of the southern part of Yuexiu Hill, resulting in a downward trend in the provision of six types of services. Of these, cultural memory has declined at the slowest rate, with the rates for the other information services in order: VSR < VAI < VE < VRE < VS and R (Figure 4).

Comparing the changes in various information services over the five periods, it was found that the addition of artificial landscape elements played a significant role in facilitating the provision of six types of information services. However, while the provision of information services is not entirely dependent on artificial elemental entities, which also play an essential role in the transmission, storage, and dissemination of heritage information, there is a downward trend but no interruption in the provision of information services when elemental entities are severely damaged.

4. Discussion

Yuexiu Hill HUL provides diverse and continuous information services that contribute to the sustainability of the historic urban landscape and are closely related to the preservation of the physical entities contained within.

4.1. Continuous Delivery of Information Services: Sustainability of HUL in the Intangible Dimension

Historic artificial elements record people’s memory, events, beliefs, and other sources of historic environmental information [35]. Although the physical entities have been destroyed or even disappeared, historic information may still be stored in the relics of material elements, even in historic documents and specific social groups. The information recorded and transmitted to the present day continues to bring about intangible benefits such as spiritual enrichment, aesthetic experience, and cognitive development to those who come after [16,36].

Viewed as a whole, Yuexiu Hill HUL provides places for recreation and interaction, as well as services to the public in terms of artistic inspiration, spirituality and religion, education, and aesthetics (Figure 4). The continued provision of these information services reflects the continuity of the Yuexiu Hill HUL in its intangible dimension, which can be diminished or even terminated by the presence of disturbances such as the destruction of physical entities.

From the perspective of the protection and restoration of single artificial elements after the disappearance of artificial elements, their names still appear in poetry texts (Table 6), reflecting the continuous provision of information services after the disappearance of physical entities. For example, Yuewang Platform, Chaohan Platform, Zhenhai Tower, and Huluan Path remain poetic hotspots even after the physical entities and their surroundings have changed. The information services associated with them do not end when the physical elements change or disappear. This phenomenon is most fully reflected in the elements related to cultural memory. The results of the correlation analysis are presented in Table 7, demonstrating the direct and significant correlation (p < 0.05 **) between “platforms” and cultural memory. The original poems corroborate the above view: “King of Yue Zhao Tuo (the name of the king of Nanyue)”, “Song and dance”, “Chongyang”, “nostalgia”, “past events”, and other phrases related to historic figures and events, as well as festive customs, appear in a large number of poems describing these artificial elements in various periods, showing that historic information related to these nodes has formed a common cultural memory of the Yuexiu Hill HUL. Moreover, cultural memory contributes to the formation of a sense of local identity and place and has been one of the driving factors in the sustainability of the historic urban landscape [15].

All kinds of heritage protection behaviors are essentially communication behaviors [14], and their essence is the transmission of historical environmental information. “Memory data stored in the built environment affects people’s behavior and attitude towards the environment [37]”, the impact of which is continuous. Making attractive plans to interpret and display historical environmental information locally [38,39] will help maintain the continuity of information services and further promote the sustainability of the historic urban landscape in intangible dimensions.

4.2. Mutual Promotion of Public Demand for Information Services and Physical Protection for Historic Urban Landscape

The intangible well-being integral to the historic urban landscape is dependent on the continued provision of information services, and the demand for such intangible well-being is an important driver of the multiple restorations that people undertake on the former sites of buildings or structures. In turn, the continued demand for information services drives people to preserve the physical elements of the historic landscape.

The numerous reconstructions of artificial elements, such as the Yuewang Platform and the Zhenhai Tower, confirm this view. The Yuewang Platform is the earliest constructed artificial element on Yuexiu Hill and appears most frequently in the poetry database and is closely associated with information services such as recreation and ecotourism (p < 0.05 **), social relations (p < 0.01 ***), spiritual and religious values (p < 0.10 *), and cultural memory (p < 0.05 **) (Table 7). The Yuewang Platform was abandoned before Period 1, while construction activities were carried out on its former site in Period 1, Period 2, and Period 5. During Period 2, it became a custom for Guangzhou residents to climb to the heights of the former Yuewang Platform during the annual Chongyang Festival, and a number of poems describe the view of the Pearl River from this height. The site was deserted in Period 3 and Period 4, but there are still a number of poems that record the sight of the grass and trees and the memory of the king. It was not until 1930 (Period 5) that a new monument was built on the site of Yuewang Platform, which has been preserved to this day. Zhenhai Tower was built in 1380 (Period 3) as a military lookout but also to enjoy the view from afar. Located directly north of the ancient city in Period 3, the building became an influential landmark in the city and is distinctly visible on maps from Period 3 to Period 4. The building was rebuilt after being destroyed on five occasions and now houses the Guangzhou Museum.

Research has been conducted to validate the similar view that parts of the landscape have been actively conserved through the generations for cultural or spiritual reasons [40,41]. Numerous sacred natural sites are recognized as hotspots of bio-cultural diversity, where there is a link between spiritual, religious, cultural, and biological values [42].

4.3. New Artificial Elements Should Be Allowed to Meet Contemporary Needs

The provision of information services relies on complex interactions and feedback between architectural, human, social, and natural capital. Even ‘presence’ and other ‘non-use values’ require people (human capital) and their culture (social and architectural capital) to acquire them [43]. To a certain extent, the emergence of new elements should be accepted to meet new functional needs, thus creating new meanings and keeping HUL alive [44].

The spatial distribution of information services in the Yuexiu Hill HUL shows that the hotspots of information services in all periods are concentrated in the south, on the side close to the ancient city. The original Yuexiu Hill HUL was a hilly area covered with vegetation, and since 204 B.C., new artificial elements have been constructed in each period. As can be seen from Table 7, these elements are correlated to varying degrees with the provision of various types of information services, which meet the material or immaterial needs of the public in the period in question. The southern area offers a richer range of information services than the northern area, where the green space cover is better preserved.

In terms of temporal distribution, the early stages of the development of Yuexiu Hill HUL were less artificially developed. Regional rulers built artificial elements, such as Yuewang Platform, Chaohan Platform, and Huluan Path, for recreational and leisure purposes in Period 1 and earlier. The construction of these elements set the historical and cultural tone of Yuexiu Hill HUL, although the activities of the public in the area were restricted by the regional rulers. The construction of a large number of study halls and religious buildings in prosperous times facilitated the provision of educational services, as well as spiritual and religious services. Although the physical entities of a large number of these elements have been destroyed or lost over time, the remnants of their construction have become objects of attraction for future generations to visit and inspire poetry. These artificial elements act as information carriers that record the relevant historic events of the period in which they are located, providing an emotionally nourishing environment for future generations [13]. Heritage information stored in the remains and by specific persons continues to provide an intangible service to the public. As the stock of architectural, human, social, and natural capital accumulates, the density of the hotspot distribution of information services continues to increase. Period 3 and the beginning of Period 4 saw the survival of artificial elements that recorded heritage information about the site, while the construction of new elements met the public’s need for information spaces at the time but did not yet completely alter the nature-driven character of the landscape. The Yuexiu Hill HUL maximizes the provision of ecotourism, recreation, and social interaction for the public in these periods (Figure 4), with the first two services in turn usually accompanied by the generation of artistic inspiration (Table 8).

Table 8.

Correlation analysis of various information services of Yuexiu Hill HUL.

4.4. Heritage Information Needs to Be Clearly Transmitted for the Maximized Provision of Information Services

Cultural heritage is the view of the entire landscape as a whole, shaped by complex human culture–environment interactions in time and space, and is the most critical medium for transferring information from the past to the future. The complexity and organization of spatial information, and its reception by the people, is crucial to our mindset [13,45]. The proper construction of artificial elements in each period not only helps to meet the functional needs of the public in the respective period but also enriches the spatial information of the urban landscape. However, the excessive construction or large-scale destruction of the original environment can disrupt the public’s perception of environmental information. These changes not only affect the provision of information services but can even cause the public to feel removed and expelled from their original environment.

Based on existing studies and the results of this case study, we speculate on the reasons for the decline in information service capacity at the late stage of the development of the Yuexiu Hill HUL from two perspectives: First, from the end of Period 4, the disorderly construction of artificial elements converted the originally nature-dominated landscape at the southern foot of Yuexiu Hill into a high-density urban landscape, and the interference of redundant information increased the difficulty of identifying and accessing heritage information from the HUL by the public, weakening the ability of the Yuexiu Hill HUL to provide information services. Second, repeated outbreaks of war destroyed the original landscape of the Yuexiu Hill HUL, and the alteration and disappearance of physical entities blocked the public’s access to heritage information from the environment in which they are located, which in turn directly led to a reduction in the HUL’s ability to provide information services. Comparing Figure 3b with the spatial distribution of information service hotspots in each period (Figure 3a), it can be seen that the nature-dominated Yuexiu Hill landscape in Period 1 and the excessive artificial construction in Period 5 were both detrimental to the provision of information services and that there was a balance between the two that maximized the provision of various information services and allowed heritage information to be clearly and effectively communicated to the public.

Heritage records and protection are increasingly valued [33], but these actions must be integrated with the protection of physical entities. Over the past 70 years, planned remediation and management have not only revitalized the hill but have also turned it into a hotspot for ecotourism and social interaction among the public [34] (pp. 186–188). Organization and exhibition houses for public participation in cultural activities and the construction of facilities for this purpose have facilitated the recording and dissemination of heritage information. Despite the alteration of the landscape characteristics, the information services provided by Yuexiu Hill HUL have continued successfully, which provides a pathway for the sustainable development of the intangible dimension of HULs in different regions.

4.5. Limitations

In this study, the choice of ancient poetry data as a source of information for the evaluation of historic urban landscape information services had its own limitations. On the one hand, this is reflected in the coverage of the groups surveyed, with poetry writers mostly confined to academics and officials, lacking adequate representation of public perception. On the other hand, the six types of information services identified in this study from poetry data do not cover all types of information services. Historic urban landscape contribute to human well-being in a variety of ways, which means a comprehensive identification of information service types requires information sources to be as complete as possible. For example, aesthetic services are usually better reflected in photo crowdsourcing [46]; “The frequency of short trips for environmental education purposes” can better reflect the quality of education services provided by landscape [47]; the frequency of symbolic species in flags, badges, brand names, and other places reflects the relationship between the distribution of symbolic species and social benefits [48]. Texts, artificial elements, and associated community groups may all serve as carriers of heritage information, and so we advocate the combination of multiple types of information sources, including text [49,50], music [51], images [46,52,53], etc. Appropriate analysis methods, such as text mining, deep learning of images, and GIS techniques, are chosen for different information types as a way to include additional information service types in the evaluation system.

5. Conclusions

This study explores the possibility of integrating the historic urban landscape approach (HUL) with the historical dynamic evaluation of ecosystem services, taking Yuexiu Hill HUL as an example. This attempt extends the temporal dimension of the service evaluation approach. That is, by collecting heritage information, the dynamics of HUL information services are evaluated over a lengthy temporal dimension and the drivers of change are analyzed. The continuous delivery of information services is considered to represent the sustainability of HUL in the intangible dimension.

Firstly, this study explores the possibility of integrating the historic urban landscape approach (HUL) with the historical dynamic evaluation of ecosystem services. The method of mining relevant data from historical records to evaluate the ability of landscape to provide information services in the historical process is expanded. Taking Yuexiu Hill HUL in Guangzhou as an example, we collected ancient poems written between 581 and 1949 that mentioned Yuexiu Hill HUL and its internal artificial elements for evaluating HUL information services. The established poetry data platform (SOU-yun.cn) has provided us with a large number of reliable data sources, and the maturity of text mining methods has helped to effectively extract key information. In recent years, keyword frequency statistical methods have been widely used in cultural service evaluation [50,54]. We used this method to extract information related to information services and artificial elements from the poetry database to evaluate the information services provided by Yuexiu Mountain HUL in five historical periods.

Second, the continuous provision of information services reflects the sustainability of Yuexiu Hill HUL in the intangible dimension. The analysis results show that, during its evolution, Yuexiu Mountain HUL recorded people’s memories, events, beliefs, and other historical information sources [35]; provided places for entertainment and interaction; and provided the public with artistic inspiration and enlightenment, spiritual and religious, educational, and aesthetic information services. The decline of these information services has lagged behind the disappearance of artificial elements, and the continuous provision of information services has expanded the intangible dimension of the historic urban landscape.

Third, the capacity and type of information services provided by HUL are affected by public demand and the construction of material elements and depend on the explicit transmission of heritage information. We analyzed the correlation between information services and the human element. The results of the analysis, combined with historical evidence, reveal the driving forces affecting the sustainability of the intangible dimensions of Yuexiu Hill. The continuous provision of information services and the physical preservation of the historic urban landscape complement each other. On the one hand, entities are important carriers of heritage information, and the provision of information services depends to some extent on the existence of entities. Both land cover change and landscape element construction affect the transmission of heritage information, which then affects the quality and type of information services. On the other hand, the demand for intangible well-being generated by information services has in turn led to a conscious effort to preserve historic landscapes. Therefore, both the method of evaluating information services as a tool and the intangible well-being resulting from the provision of information services should be given due attention in the development of renewal policies.

Our next effort is to further refine the methodological framework and use the evaluation results to guide practices in the conservation and management of the historic urban landscape. By consciously changing the landscape pattern, we achieve a sustainable provision of services while meeting social needs and respecting social values [21]. We will continue to explore ways to preserve the integrity and authenticity of information about the historic environment and to disseminate this information efficiently and interestingly in the community so that the public can derive various benefits from it while stimulating public awareness of the conservation of the historic urban landscape. In addition, the inclusion of new artificial elements adapted to contemporary public needs should also be a focus of conservation and management practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.G. and S.W.; methodology, W.G. and S.W.; software, S.W. and S.C.; validation, W.G. and S.C.; formal analysis, W.G. and S.W.; investigation, S.W.; resources, S.W. and S.C.; data curation, S.W. and S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, S.W.; writing—review and editing, W.G. and S.W.; visualization, S.W.; supervision, W.G.; project administration, W.G.; funding acquisition, W.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province China, grant number 2022A1515011398. This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 52078222.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy reasons.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Minqing Que from South China Agricultural University for his assistance with the formal analysis, and to Director Wang Aijun and Deputy Director Huang Haijie of Yuexiu Park for valuable comments and provision of historical archives.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Evaluation of information services for various types of artificial landscape elements.

Table A1.

Evaluation of information services for various types of artificial landscape elements.

| Element Types | Standard Phrase | f1 | F1 | S1 | f2 | F2 | S2 | f3 | F3 | S3 | f4 | F4 | S4 | f5 | F5 | S5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Platform | Yuewang Platform | 18 | 25 | 0.066138 | 62 | 84 | 0.206388 | 191 | 231 | 0.935223 | 144 | 179 | 0.606780 | 18 | 19 | 0.513514 |

| Chaohan Platform | 7 | 20 | 38 | 35 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Jiao Platform | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Temple | Wanggu Nunnery | 0 | 0 | 0.000000 | 0 | 4 | 0.009828 | 0 | 5 | 0.020243 | 17 | 20 | 0.067797 | 0 | 0 | 0.000000 |

| Guanyin Pavilion | 0 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Xizhu Temple | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Hongmian Temple | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Bushi Nunnery | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Taoist temples and ancestral halls | Sanyuan Taoist Palaces | 0 | 0 | 0.000000 | 3 | 4 | 0.009828 | 1 | 1 | 0.076923 | 10 | 26 | 0.088136 | 0 | 2 | 0.054054 |

| Sanjun Ancestral Hall | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Zhaozhong Ancestral Hall | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Yuewang Tomb | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |||||||||||

| Tower | Zhenhai Tower | 0 | 0 | 0.000000 | 0 | 0 | 0.000000 | 92 | 93 | 0.376518 | 37 | 42 | 0.142373 | 2 | 2 | 0.054054 |

| Weituo Tower | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Small structures | Huluan Path | 0 | 6 | 0.015873 | 0 | 8 | 0.019656 | 19 | 51 | 0.206478 | 7 | 20 | 0.067797 | 0 | 0 | 0.000000 |

| Xieyan Spring | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Wanli Bridge | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Banshan Pavilion | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Yuewang Well | 6 | 8 | 32 | 8 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Garden | North Garden | 0 | 0 | 0.000000 | 0 | 3 | 0.007371 | 1 | 12 | 0.048583 | 0 | 7 | 0.023729 | 0 | 2 | 0.054054 |

| Ji Garden | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Yixiu Garden | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Other Gardens | 0 | 3 | 11 | 0 | 2 | |||||||||||

| Academy | Taiquan Academy | 0 | 0 | 0.000000 | 0 | 0 | 0.000000 | 1 | 4 | 0.016194 | 0 | 26 | 0.088136 | 0 | 1 | 0.027027 |

| Xuehai Academy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Yingyuan Academy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Jupo Academy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Other Academies | 0 | 0 | 3 | 8 | 0 |

Note: Siz = Fiz/Ti (i = 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5; z = Platform, Temple, Taoist temples and ancestral halls, Tower, Small structures, Garden and Academy).

Table A2.

Shapiro–Wilk test of the information services and the landscape elements.

Table A2.

Shapiro–Wilk test of the information services and the landscape elements.

| Information Services | SR | RE | AI | SRV | EV | CM | - |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S–W test | 0.921 | 0.925 | 0.905 | 0.856 | 0.789 | 0.836 | - |

| Element Types | Platform | Temple | Taoist temples and ancestral halls | Tower | Small structures | Garden | Academy |

| S–W test | 0.968 | 0.783 | 0.899 | 0.816 | 0.782 | 0.906 | 0.798 |

Note: All variable levels in the table do not present significance and the original hypothesis cannot be rejected, therefore the data satisfy a normal distribution.

References

- Plieninger, T. Resilience and the Cultural Landscape: Understanding and Managing Change in Human-Shaped Environments; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape; UNESCO: Paris, France, 10 November 2011; Volume 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Termorshuizen, J.W.; Opdam, P. Landscape services as a bridge between landscape ecology and sustainable development. Landsc. Ecol. 2009, 24, 1037–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, A.; Kuttner, M.; Hainz-Renetzeder, C.; Konkoly-Gyuró, É.; Tirászi, Á.; Brandenburg, C.; Allex, B.; Ziener, K.; Wrbka, T. Assessment framework for landscape services in European cultural landscapes: An Austrian Hungarian case study. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 37, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Marggraf, R. Making Intangibles Tangible: Identifying Manifestations of Cultural Ecosystem Services in a Cultural Landscape. Land 2021, 11, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plieninger, T.; Dijks, S.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; Bieling, C. Assessing, mapping, and quantifying cultural ecosystem services at community level. Land Use Policy 2013, 33, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittrich, A.; von Wehrden, H.; Abson, D.J.; Bartkowski, B.; Cord, A.F.; Fust, P.; Hoyer, C.; Kambach, S.; Meyer, M.A.; Radzevičiūtė, R.; et al. Mapping and analysing historical indicators of ecosystem services in Germany. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 75, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, R.S.; Wilson, M.A.; Boumans, R.M.J. A typology for the classification, description and valuation of ecosystem functions, goods and services. Ecol. Econ. 2002, 41, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, R.S.; Spellergerg, I.F. Functions of Nature: Evaluation of nature in environmental planning, management and decision making. Environ. Values 1993, 2, 274–276. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza, R.; d’Arge, R.; de Groot, R.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M.; Hannon, B.; Limburg, K.; Naeem, S.; O’Neill, R.V.; Paruelo, J.; et al. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 1997, 387, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokilehto, J.I.; Larsen, K.E. Nara Conference on Authenticity in Relation to the World Heritage Convention; UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Hoi an Protocols for Best Conservation Practice in Asia: Professional Guidelines for Assuring and Preserving the Authenticity of Heritage Sites in the Context of the Cultures of Asia; UNESCO Bangkok Asia and Pacific Regional Bureau for Education: Klongtoey Bangkok, Thailand, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Salingaros, N.A. Urban Space and its Information Field. J. Urban Des. 1999, 4, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. The Icomos Charter for the Interpretation and Presentation of Cultural Heritage Sites. In Proceedings of the 16th General Assembly of ICOMOS, Québec, the Auspices of the ICOMOS International Scientific Committee on Interpretation and Presentation of Cultural Heritage Sites, Québec city, QU, Canada, 4 October 2008; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, F.; Stephens, J.; Tiwari, R. Grounded Theory as an Approach for Exploring the Effect of Cultural Memory on Psychosocial Well-Being in Historic Urban Landscapes. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaslip, V.; Vahdaninia, M.; Hind, M.; Darvill, T.; Staelens, Y.; O’Donoghue, D.; Drysdale, L.; Lunt, S.; Hogg, C.; Allfrey, M.; et al. Locating oneself in the past to influence the present: Impacts of Neolithic landscapes on mental health well-being. Health Place 2020, 62, 102273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Groot, R. Function-analysis and valuation as a tool to assess land use conflicts in planning for sustainable, multi-functional landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 75, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, R.S.; Alkemade, R.; Braat, L.; Hein, L.; Willemen, L. Challenges in integrating the concept of ecosystem services and values in landscape planning, management and decision making. Ecol. Complex. 2010, 7, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; Volume 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Erll, A. A Companion to Cultural Memory Studies; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2010; p. 441. [Google Scholar]

- Nassauer, J.I.; Opdam, P. Design in science: Extending the landscape ecology paradigm. Landsc. Ecol. 2008, 23, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Landscape sustainability science: Ecosystem services and human well-being in changing landscapes. Landsc. Ecol. 2013, 28, 999–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selman, P. What do we mean by sustainable landscape? Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2017, 4, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kosanic, A.; Petzold, J. A systematic review of cultural ecosystem services and human wellbeing. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 45, 101168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, N.; Brady, E.; Steen, H.; Bryce, R. Aesthetic and spiritual values of ecosystems: Recognising the ontological and axiological plurality of cultural ecosystem ‘services’. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 21, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentini, L.; Guerra, V.; Lazzari, M. Enhancement of Geoheritage and Development of Geotourism: Comparison and Inferences from Different Experiences of Communication through Art. Geosciences 2022, 12, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez Sanchez, M.; Tejedor Cabrera, A.; Gomez del Pulgar, M.L. The potential role of cultural ecosystem services in heritage research through a set of indicators. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 117, 106670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggio, A.; Kuffer, J.; Lazzari, M. Advances and trends in bibliographic research: Examples of new technological applications for the cataloguing of the georeferenced library heritage. J. Librariansh. Inf. Sci. 2017, 49, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X. Yuexiu Hill; Guangdong People’s Publishing House: Guangzhou, China, 2008; p. 106. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, S.L. Research on the Conservation of Space Pattern of Guangzhou; South China University of Technology: Guangzhou, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Norton, B.B.R.; Costanza, R.; Cooper, W.; Russell, C.; Hayden, G.; Brody, M.; Payne, J.; Suter, G.; Hale, T.; Bromley, D.; et al. Issues in ecosystem valuation: Improving information for decision making. Ecol. Econ. 1995, 14, 73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Li, X.; Zhao, W. Research on Cultural Landscape Patterns of Guanzhong Area Based on Text Mining of Tang Poetry. Landsc. Archit. 2019, 26, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, X. Research on the Development Path of Cultural Heritage Information Visualization from the Perspective of Digital Humanities. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2022, 2022, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, P.Z. Yuexiu Hill of the Thousand Years; Guangdong People’s Publishing House: Guangzhou, China, 2018; p. 273. [Google Scholar]

- Molavl, M.; Malekshah, E.R. Is Collective Memory Impressed by Urban Elements? Manag. Res. Pract. 2017, 9, 14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Innes, A.; Scholar, H.F.; Haragalova, J.; Sharma, M. ‘You come because it is an interesting place’: The impact of attending a heritage programme on the well-being of people living with dementia and their care partners. Dementia 2021, 20, 2133–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, M.C. The City of Collective Memory: Its Historical Imagery and Architectural Entertainments; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996; p. 572. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, W.; Guo, Y.; Jiang, F. Playing for a Resilient Future: A Serious Game Designed to Explore and Understand the Complexity of the Interaction among Climate Change, Disaster Risk, and Urban Development. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, A. Games on Climate Change: Identifying Development Potentials through Advanced Classification and Game Characteristics Mapping. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeri, Z.; Mohammadi-Samani, K.; Bergmeier, E.; Plieninger, T. Spiritual values shape taxonomic diversity, vegetation composition, and conservation status in woodlands of the Northern Zagros. Iran. Ecol. Soc. 2021, 26, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, R. Sacred Natural Sites: Guidelines for Protected Area Managers; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Frascaroli, F.; Bhagwat, S.; Guarino, R.; Chiarucci, A.; Schmid, B. Shrines in Central Italy conserve plant diversity and large trees. Ambio 2016, 45, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; de Groot, R.; Sutton, P.; van der Ploeg, S.; Anderson, S.J.; Kubiszewski, I.; Farber, S.; Turner, R.K. Changes in the global value of ecosystem services. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 26, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes Zancheti, S.; Piccolo Loretto, R. Dynamic integrity: A concept to historic urban landscape. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 5, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, A. Shaping the contours of fractured landscapes: Extending the layering of an information perspective on refugee resettlement. Inf. Process. Manag. 2020, 57, 102062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenerelli, P.; Püffel, C.; Luque, S. Spatial assessment of aesthetic services in a complex mountain region: Combining visual landscape properties with crowdsourced geographic information. Landsc. Ecol. 2017, 32, 1097–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocior, E.; Kruse, M. Educational values and services of ecosystems and landscapes—An overview. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 60, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirpke, U.; Meisch, C.; Tappeiner, U. Symbolic species as a cultural ecosystem service in the European Alps: Insights and open issues. Landsc. Ecol. 2018, 33, 711–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Marggraf, R. Ecosystems in Books: Evaluating the Inspirational Service of the Weser River in Germany. Land 2021, 10, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-h.; Park, H.-j.; Kim, I.; Kwon, H.-s. Analysis of cultural ecosystem services using text mining of residents’ opinions. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 115, 106368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coscieme, L. Cultural ecosystem services: The inspirational value of ecosystems in popular music. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 16, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenerelli, P.; Demšar, U.; Luque, S. Crowdsourcing indicators for cultural ecosystem services: A geographically weighted approach for mountain landscapes. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 64, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, N.; Hiura, T. Demand and supply of cultural ecosystem services: Use of geotagged photos to map the aesthetic value of landscapes in Hokkaido. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 24, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayama, N.; Baba, Y.G. Measuring artistic inspiration drawn from ecosystems and biodiversity: A case study of old children’s songs in Japan. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 43, 101116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).