Abstract

This review examines the use of residual biomass as a renewable resource for energy generation in the Dominican Republic. The odology includes a thorough examination of scientific publications in recent years about logistics operations. The use of mathematical models can be beneficial for the selection of areas with a high number of residual biomass and processing centers; for the design of feedstock allocation; for the planning and selection of the mode of transport; and for the optimization of the supply chain, logistics, cost estimation, availability of resources, energy efficiency, economic performance, and environmental impact assessment. It is also essential to consider the exhaustive analysis of the most viable technological solutions among the conversion processes, in order to guarantee the minimum emissions of polluting or greenhouse gases. In addition, this document provides a critical review of the most relevant challenges that are currently facing logistics linked to the assessment of biomass in the Dominican Republic, with a straightforward approach to the complementarity and integration of non-manageable renewable energy sources.

1. Introduction

Climate change and the increase in world population have increased the global level of environmental degradation and depletion of natural resources. These challenges prompt the need for a transition towards efficient production, consumption in the use of resources, the reduction in and recovery of waste streams, and the transformation required of consumption habits [1]. The most widely used energy sources on the planet are fossil fuels, particularly oil. At present, these fuels are the most widely used globally and drive the economies of the wealthiest countries [2].

The combustion of fossil fuels inherently produces and releases harmful chemicals into the environment, in addition to causing other environmental burdens; therefore, it is essential to move towards the use of renewable energy resources to minimize the environmental impacts of fossil fuels [3,4]. Given the magnitude of the problems that arise with conventional energy sources, agreements have been generated, such as the Paris Agreement in 2015 [5], aimed at counteracting climate change, making it clear that, it must contemplate and include the use of renewable energy sources to transition away from fossil fuels [6].

Among these energy sources stands out biomass, which has forever been used by humanity for heat and lighting [7,8]. In the total primary energy supply, fossil fuels represent 81%, nuclear energy represents 5%, and renewable energy sources represent 14% (of this, biomass contributes around 70%) [9].

This article aims to systematically compile the most important trends in the use of residual biomass as a renewable energy resource, focusing on the Dominican Republic. Specifically, all aspects of the supply chain will be addressed, highlighting logistical aspects [10,11,12,13,14,15,16], optimization models [13,14,15,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27], and geographic information systems [18,19,20], as well as their significance, to make the decision-making process easier [17,28,29,30], referring to the optimization of the use of biomass in terms of availability, cost, and quality; conversion performance; transportation; and storage costs. Analysis is carried out by grouping the collected scientific material around environmental impact, supply chain, costs, and biomass conversion processes.

The main contributions of this work are the following:

- A critical review of trends in logistics operations linked to biomass conversion into energy;

- Identification of relevant factors and their solutions for optimizing resources to impact cost reduction;

- A detailed discussion of the factors identified in the literature and their relationship in the context of the Dominican Republic, to facilitate the integration and reduction in intermittence generated by non-manageable renewable energy sources.

This document is structured as follows: Section 2 describes the relevance and advantages of using biomass as a source of energy; Section 3 analyzes approaches to technological solutions for energy generation; Section 4 presents research trends in the energy use of biomass. Section 5 examines our conclusion and challenges.

2. Energy Use of Biomass

Due to rising oil prices, increased agricultural production, climate change, and new methods of obtaining energy, biomass has resurged as an energy source [31].

Over time, supply concerns, as well as the gradual concern both about achieving sustainable development and mitigating climate change, have emerged. These facts have prompted the international community to advance on global and regional initiatives in support of the introduction of renewable energy sources [32].

As such, the approaches to eliminating greenhouse gases are considered essential in several projections to meet the ambitions set out in the Paris Agreement [33]. Additionally, public acceptance is one of the main factors influencing local utilization of renewable energy [34].

In a productive oil based economy, as in the case of the Dominican Republic, the increase in the cost of fossil fuels, in combination with the detrimental environmental impact, has led authorities to adopt commitments aimed at promoting renewable energies. In particular, promoting biomass generates advantages, as it is a diverse, manageable source with broad technological applications with neutral emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) [35].

In the current environmental context, the Dominican Republic is committed locally and internationally to providing solutions towards a diversified matrix of renewable sources and reducing global greenhouse gas emissions. In this regard, reports from the Directorate of Alternative Sources and Rational Use of Energy of the National Energy Commission (CNE) refer to the need to take advantage of the existing biomass potential, taking into account the commitment to reach 300 MW of installed energy capacity by 2030 in the framework of the Paris Agreement [36].

The Dominican State has made evident its intention to define a diversified and renewable energy matrix, after the approval of Law 57-07 on “Incentives for the Development of Renewable Energy Sources and their Special Regimes” [37], which suggests the granting of incentives to develop energy generation projects from the use of wind, solar, and biomass. At present, large scale energy projects based on renewables have been developed at the national level, taking advantage of the benefits provided by such legislation.

San Pedro Bioenergy stands out among the projects that supply electricity to the National Interconnected Electric System, which has an installed capacity of 30 MW using sugarcane bagasse biomass as fuel. Monte Plata Solar is another project with sufficient capacity to generate 60 MW [38], and the Los Cocos and Larimar wind farms, owned by the company EGE Haina, contribute up to 175 MW. Despite the significant progress made, fundamental challenges still prevail, linked to offering a renewable and sustainable energy supply and other problems associated with aspects such as access to local financing, and the improvement of tax incentives that can cover a broader spectrum of the production chain. Other aspects include the formalization of the market, the contribution of subsidies, the quality of the energy supply, the protection of the producer, and the generation of scientific–technological information [38].

The Dominican Republic has exhibited traditional models for the use of biomass, for example, the generation of steam and electricity in sugar mills and the drying of rice in factories, which were not necessarily carried out within a framework of ecological sustainability. Environmental imperatives set by the headquarters of two free zone companies with large operations in the country, and the enactment of Law 57-07, became catalysts for developing an incipient biomass market [36].

Faced with a growing demand for biomass resulting from the substitution of conventional boilers for biomass boilers for industrial processes, the National Energy Commission of the Dominican Republic saw an excellent opportunity for growth in the market for this energy source. The orderly growth of the biomass business within a sustainable development strategy would not be possible without a study that establishes a baseline of the market (current production) and potential production and the characterization of the types of biomass. This is needed to have the necessary inputs for the quality regulations of this and a ten-year plan of the projected growth of the market [39]. All these considerations served as the basis to justify one of the most recent investigations carried out by the National Energy Commission [37], whose primary purpose was to analyze the current biomass production in the Dominican Republic, as well as its potential, in addition to defining a plan for the use of energy generation, based on obtaining the following products:

- Baseline study of the biomass market for generation;

- Geographical/spatial analysis of the areas with the most significant potential for biomass production;

- Plans to promote the use of biomass for thermal and electric energy;

- Existing laws, regulations, and regulations on biomass.

The demand estimate for the year 2030 for wind and solar energy is around 63% of the demand in real time. This would mean a third more of the wind energy and almost a quarter more of the solar energy used in recent years, thereby reducing natural gas and petroleum derived fuels by more than 25% [20]. In this projection, the need to install a battery as a frequency support is evident [40].

It is crucial to bear in mind that the natural variability of demand due to consumers’ unpredictable and instantaneous decisions is opposed by a generation that, while renewable energy is incorporated into the energy mix, behaves less manageably and dramatically complicates the operation of the electrical system. For a high contingent of non-manageable renewable energies to be safely integrated, it will be essential that the operation of the electrical system be equipped with a variety of tools that guarantee this [41].

The variability of feedstock requires the connection of backup generation with a manageable and sufficiently flexible nature, capable of absorbing the production variations derived from the intermittence, in terms of its presence, of the primary resource [41]. In the current scenario of the Dominican Republic, there is a biomass potential that is not sufficiently quantified from the energy point of view, as well as the dispatch and management conditions of this resource in electricity generation to cover the intermittency caused by the renewable energies already used, such as solar and wind.

2.1. Identification of Potentialities

Identifying potentials for the production and use of biomass refers to the evaluation and quantification of biomass potential in a particular locality, according to its different origins and possibilities for introduction into the energy market, considering the estimated costs for its production and market distribution. Resource evaluations are an indispensable element in the feasibility study for establishing a biomass plant, which requires in depth knowledge of the potential for biomass generation according to its nature, be it primary or secondary.

In this sense, biomass resource evaluations should allow estimating the potential, as well as the amount, of usable biomass in an area, even supplying valid information according to the desired level of detail; additionally, such evaluations should serve to determine the size or energy production capacity of a region or to make a decision about the location of a plant [28].

Therefore, a standard methodology is required to recognize potentially suitable areas for sustainable bioenergy crops. This methodology would better identify promising crops and cropping systems, and logistical and economic studies, and better estimate the work required to meet regulatory criteria [42]. Under the premises above, investigations have been directed to estimating the biomass potential in the Dominican Republic, which has made it possible to establish the different biomass resources available and their theoretical energy availability [41].

However, it is essential to clarify the maximum theoretical potential, including technical or economic factors. In addition to identifying the primary biomass resources present, such as sugar cane, coffee, rice, cocoa, and banana, these investigations delve into the possibility of planting energy crops for electricity generation. However, this alternative must be oriented appropriately, since, with an increase in energy production, crops would promote monoculture agricultural practices that could cause a variety of inconveniences with environmental and local impact [43]. It must also be considered that the main barriers in the development of biomass and biofuels are the high cost of the raw material, the lack of reliable supply, and uncertainties [44].

Under the conditions of the Dominican Republic, there is a potential for residual biomass derived from different agro-industrial processes, which, at the same time, constitute a residue that requires the producer to handle or treat it for its final disposal, which can be costly; however, its use for energy purposes is still limited. The energy potential of these wastes for producing electricity or other energy applications must be linked to the sectors that generate them, which would reduce the electricity demand at a local or country level. Furthermore, biomass could also serve as a strategic complement to intermittent renewable energies by supplying electricity during hours of high residual load [45] and thus achieving better stability during the supply of electrical energy and favoring the possibility of increasing the level of penetration of intermittent or nondispatchable renewable energy sources in the Dominican energy mix.

According to the Worldwatch Institute [46], integrating a multiplicity of renewable energy sources could achieve an even more significant reduction in the problems associated with the intermittency of renewable sources. Particularly in the case of the Dominican Republic, the combination of solar and wind generation in the grid could specifically contribute to reducing seasonal variability. In addition, the alternatives for storing electricity, especially those concerning batteries and hydraulic pumping systems, could be offset by the capacity of renewable energy for storing energy generated during periods of high production and low demand, to supply the network at peak hours. Collectively, the use of biomass power plants, fast on and off, in parallel with solar power plants, can also generate baseload energy.

2.2. Biomass Selection Criteria

Correctly choosing biomass in specific areas reveals the importance of using pertinent selection criteria. When choosing the most appropriate energy options, evaluation criteria should be developed that may be useful for decision-makers seeking the integrated performance of other alternatives [46]. Pohekar and Ramachandran further emphasize the importance of the selection criteria. Despite the widespread promotion of renewable energies for different applications, compared to improved technologies for energy production and more intense competitiveness with other conventional energies, the contribution of renewable energies is still considered modest [29].

Consequently, it is preferable to formulate different concepts, primarily associated with energy planning, so that decision-makers can identify and remove obstacles that prevent biomass energy from becoming a relevant source in the future.

Cost considerations still dominate discussions about climate protection and energy sector transition in the Dominican Republic. The expanded use of renewable energies and the application of energy efficiency restoration measures can positively impact local and regional added value and employment [47]. It is necessary to delve into the analysis of the potential, both in this agricultural sector and on an industrial scale, to establish the most suitable conversion routes by type of biomass, to allow the correct use of these and estimate their availability in temporary spaces.

The preceding should make it possible to evaluate complementarity with distributed electricity generation, considering that biomass is a manageable resource that can reduce the intermittency that occurs during generation in the electricity system, compared to other renewable sources of electricity. On the other hand, according to González and Muñoz, sustainability problems and technical–economic parameters linked to supply chain management must be considered [25].

2.3. Numerical Analysis Tools and Geographic Information Systems

Knowing the potential quantity of biomass in a territory is not the only factor considered in determining the viability of using this resource in energy applications [48,49]. There are factors of a spatial nature with decisive influence on its use, since they determine the cost of extraction, the distance from the source to the transport network, and other environmental conditions. The link of a spatial component is, evidently, related to the resource’s valuation and the optimal locations for its use. Numerical analysis technologies and geographic information systems (GIS) are tools that make it possible to assess the complexity of biomass resources and define the most relevant factors from a territorial and cost-estimation point of view [50,51].

Alluding to this, some studies reflect the usefulness of using statistical data and GIS methods in estimating biomass resources and their bioenergy potential [52]. For their part, they reviewed the essential characteristics of biomass logistics operations, discussing how these were incorporated into mathematical optimization models, also explaining the new trends in their optimization [14]. One of the most critical aspects of biomass use is its supply chain and all the elements that are part of it; modeling is a powerful tool to improve its efficiency [53]. However, biomass models for the energy supply chain must include analyzing several different variables and highlighting the main disadvantages of their use [54]. In this regard, models and methods to optimize biomass supply chains have been analyzed, making a complete overview of research in this field focusing on optimization modeling problems and solution perspectives. Other tools, such as satellite, aerial, and terrestrial remote sensing, can be handy to monitor and estimate biomass to increase raw material production from energy crops and maximize their yield [55].

Due to the low demand for biomass by consumers and investors due to the high costs in its transformation for energy purposes, tools are required that allow optimal modeling of the supply chain of this resource. This can be implemented at the national and regional level, considering the abundance and accessibility of biomass in the Dominican Republic. These new optimization models motivate the exercise of a notable contribution to the revitalization of the agro-industrial and rural areas, promoting, in parallel, the achievement of the proposed goals in energy self-sufficiency and the replacement of fossil fuels by renewable energy [56].

Evaluating the effective and absolute magnitude of bioenergy resources, together with the development of geographic information systems that allow estimating their availability, location, ownership regime, and limitations of use, will promote the sustainable and efficient use of bioenergy sources in the country.

The use of biomass under planning and sustainability parameters will collaborate to maintain the region’s agricultural areas’ essential ecological, economic, and social functions. Few studies have been carried out on agro-industrial harvesting and logistics systems linked to biomass resources in the Dominican Republic. In this sense, of particular interest is the identification of existing residual biomass potentials and especially the valuation of land use to define areas that can be utilized for the proliferation of forest biomass and for the systems of geographic information, according to its application in similar studies [57].

On the contrary, the existence of conversion technologies for agricultural biomass, developed and in use, is notorious; due to this, the establishment of predictive models of the supply chain of this resource is imperative [58], which define a low cost bioenergy utilization system for agricultural biomass, in adaptation to the realities of the region. In general, in bioenergy, the Dominican Republic has an unlimited amount of agricultural residues and waste, which are residual sources with enormous potential that could meet the growing energy demand [59] and, in turn, increase the share of renewables.

Concerning the above, the region has set ambitious goals to reduce its per-capita greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions through residual biomass. However, its lower calorific value and lower density than mineral coal are disadvantages for the sustainable use of residual biomass as an energy source [60]. The estimation of the quantities of potential and existing biomass available represents the first parameter to be considered for determining the viability and convenience of using biomass in power generation and, in addition, the support of the support plans. This is vital to achieve an integrated and optimized use of the resources present in the territory for biomass management. The Dominican Republic lacks complete and scientifically developed studies on the actual quantification of mobilizable agricultural biomass resources for bioenergy use, both from a quantitative and qualitative perspective, with the support of the aforementioned tools.

3. Biomass as a Source of Energy Generation

Biomass can be used to meet a wide variety of energy needs, including generating electricity, supplying heat for industrial facilities, heating homes, and fueling vehicles, among other applications. The conversion of biomass to these valuable forms of energy can be achieved using various technological solutions that can be separated into two basic categories: thermochemical processes and biochemical/biological processes [11,61].

The options for biomass conversion processes are classified according to the type of final energy products, including thermochemical processes and chemical processes. Focusing on thermochemical processes, the leading technology solutions are as follows [62]:

- Combustion converts biomass energy into heat, mechanical energy, or electricity. The net conversion efficiencies range from 20% to 40%, and even higher values are possible when biomass is burned in coal fired power plants. The most commonly used combustion chambers for biomass applications are fluid bed and hearth designs; the latter is rapidly becoming the technology of choice due to low nitrogen oxide emissions [62].

- Gasification converts biomass into a fuel gas mixture of carbon monoxide, hydrogen, and methane, characterized by a low calorific value burned to produce heat and steam or used in gas turbine cycles to obtain electricity. Conversion efficiencies of up to 50% can be achieved in gasification using integrated biomass gasification/combined gas–steam cycles. Although many biomass gasification processes have been developed commercially, only fluid bed configurations are considered in applications ranging from 5 to 300 MW [62].

- Pyrolysis is the conversion of biomass into a liquid fraction (bio-oil), a solid fraction (charcoal), and a gaseous fraction by heating the biomass in the absence of air [62].

Regarding biochemical processes, the primary conversion options include [62]:

- 4.

- Fermentation is when the sugars released during enzymatic hydrolysis are fermented to carry out ethanol production, also producing carbon dioxide, butanol, organic acids, xylitol, and furfural [63]. This process uses microorganisms to convert a fermentable substrate into recoverable products, such as biomass, alcohols, and organic acids. Hexoses, especially glucose, represent the most assimilable substrate by microorganisms, while pentoses, glycerin, and other compounds need specific or modified organisms to convert possible [64].

- 5.

- Anaerobic digestion converts biomass into biogas, composed mainly of methane and carbon dioxide, through bacterial action in the absence of oxygen. Anaerobic digestion is a commercially proven technology widely used to treat high moisture biomass [12,62].

- 6.

- Another technology is represented by the mechanical extraction processes, capable of producing energy in biodiesel forms. However, it is only a part of the process that consists of transesterifying oils and fats with methanol in the presence of a catalyst. However, currently, the cost of biodiesel compared to fossil fuel makes this conversion uncompetitive; however, the increasing focus of government policies on achieving better air quality standards may rapidly change this perspective [12].

The choice of the appropriate conversion process is influenced by many key factors, such as the type and quantity of biomass resources, energy carriers and end use applications, environmental standards, and economic conditions. Likewise, it is essential to note that biomass resources include wood and wood residues, crops (i.e., short rotation woody crops, woody, herbaceous, sugar, and oilseed crops), byproducts, and solid residues. Municipal waste comes from agro-industrial and food processes, aquatic plants such as algae and water weeds, etc. [64].

In addition to the amount of energy potentially available from certain biomass species, other properties that dictate the most appropriate choice of the energy conversion process are represented by the moisture content, the cellulose/lignin ratio, and the ash content.

Regarding the cellulose/lignin ratio, this parameter only affects the biochemical conversion processes; particularly, biomass with a high proportion of cellulose instead of lignin—such as hardwood, which contains 25–50% cellulose and 20–25% lignin—is more compatible with fermentation processes. Finally, concerning the ash content, low percentages are preferred for thermochemical and biochemical processes because, given the available energy production of the adopted conversion technologies, the resulting amount of the final product is proportionally reduced [12]. How frequently energy is required drives the selection of the technological solution, then the type and amount of biomass available.

Despite the widely accepted potential of the advantageous use of bioenergy, the critical problems regarding biomass remain the limited availability in terms of time due to its seasonality and the dispersed geographical distribution in the territory, which makes the collection, transportation, and storage operations complex and expensive. These critical logistical aspects strongly affect bioenergy conversion systems’ economic and energy performance, introducing limitations on their suitability. In addition, the large number of the possible combinations of various biomass sources, the different conversion approaches available, and the various end use applications (power generation/heat and transport fuel), make it challenging to choose the optimal solution from a cost and power generation perspective [12].

Under these premises, this article presents a documentary review of recent research to determine the economic viability of the use of biomass for direct energy production through thermochemical conversion processes, considering the related technical, organizational, and logistical problems with the bioenergy chain. Thermal utilization processes have been chosen for analysis because they favor the direct production of electrical energy in a reasonably wide range of plant sizes, allowing centralized or decentralized applications that represent the most promising solutions for industrial applications from biomass to energy [11].

4. Research Trends in the Energy Use of Biomass

4.1. Environmental Impact

Concerning the evaluation of biomass resources and the generation of bioenergy for clean and sustainable development, Mboumboue and Njomo [65] developed a study in Cameroon whose purpose was to quantify and evaluate the energy potential of residual biomass; examine the corresponding conversion systems; and, finally, analyze the importance of biomass as a source of energy and its possible contribution to the sustainable development of the country. The results reveal that biomass sources could contribute significantly to meeting future energy requirements, depending on the type and quantity of the biomass source, the desired final energy, the environmental impact, and the economic conditions, as well as the energy conversion of the biomass, through biochemical and biological conversion systems that are in different stages of research, development, demonstration, and commercialization.

Under the premise that biomass combustion has become one of the essential elements in the fight against global warming in the last decade, Wielgosinski and Łechtanska [66] studied the emission of some pollutants in biomass combustion in comparison with the combustion of mineral coal. The objective of this research was to evaluate seven biomass samples in comparison with pulverized mineral coal. The analysis consisted of determining and comparing the pollution emission factors (per unit mass of fuel) of carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen oxide (NO), and the sum of hydrocarbons (such as total organic carbon and TOC) generated in the biomass combustion process.

In addition, the results obtained for coal were compared and the effect of the operating conditions of the process (temperature, airflow) on the emission factors was identified. The study results reveal that, in many cases, the emission indicators determined for biomass—in particular, for total organic compounds—are unexpectedly higher than for mineral coal. Therefore, it is wrong to consider biomass as a truly green fuel, even though it is undoubtedly renewable. Its emissions are too high and comparable to coal combustion, while its hydrocarbon emissions are even higher. Despite these findings, many studies dispute this claim [67].

The current consumption of European industrial energy, with particular attention to bioheating, has been reviewed. Specifically, the available solid biomass feedstock and energy conversion alternatives were examined, along with prospects for increased biomass consumption in various industrial sectors, considering that defining global strategies for industrial heat are not accessible due to the diversity of industrial processes [68]. Combustion certainly dominates industrial heat production from biomass; however, gasification systems are already commercially available. The results reveal that the production and consumption of solid biomass in Europe are almost balanced. The pressure on biomass resources is increasing, and this must be monitored from the point of view of the environmental impact of bioheating, ensuring that sustainability is taken into account.

The evidence indicates that it is worth supporting biomass as an energy source from an environmental perspective, suggesting that governments should promote the sustainable supply of biomass materials and that the renewable energy industry should be developed under local conditions. In general, bioenergy plays a fundamental role in preserving the environment by reducing CO2 emissions, a product of the substitution of the use of fossil fuels, and the recovery of specific biomass residues that generate diffuse emissions in addition to its positive impact on ecosystem management. Some other recent studies concerning the approach to this issue are summarized in Table 1 [69].

Table 1.

Environmental impact of the use of biomass according to pollutant emissions.

In general terms, the Dominican Republic has set ambitious goals to reduce its GHG emissions per capita, for which it is proposed to reduce dependence on imports of fossil fuels and their impacts on the environment, including those associated with climate change. “The goal is to reduce GHG emissions by 25% by 2030 compared to 2010”; this will require a change in the country’s energy matrix that includes diversification of supply [37]. In this scenario, biomass constitutes one of the least used energy resources in the country; therefore, increasing its use would contribute to the diversification of the Dominican energy mix and would be a factor to consider to mitigate intermittency during electricity generation non-manageable renewable energies.

4.2. Biomass Supply Chain

Supply chain systems are made up of means and methods that allow the efficient implementation and control of materials and products from the point of origin to consumption. Their purpose is the integration of processes to obtain environmental, social, and economic benefits. As there is a significant source for the use of biomass, the sustainability of the supply chain involves various decisions and points of analysis with questions such as the type of biomass to select, how much and where to take it, what production technology to install, where to locate the centers of use, and with what capacity and which market to satisfy in order to favor the cost–benefit ratio [79]. In general, a sustainable supply chain suggests consideration of the economic performance, environmental impact, and social benefit of supply operations, as argued by Nguyen [80].

Thus, it must be understood that the optimal design of a biomass supply chain is a complex problem, which must take into account a variety of interrelated factors (that is, the spatial distribution of the network nodes, the planning efficiency of logistics activities, and many others) [81]. Comprehensive reviews of biofuel supply chain design as an optimization problem classify the scientific literature based on decision levels, objective functions, model features, sustainability metrics, and solution methodologies [82].

On the other hand, it is also worth noting that the performance of a supply chain highly depends on the decision made after considering multiple factors that affect the efficiency of the biomass supply chain, factors that can be contradicting. It is essential to adopt an optimized biomass supply chain to ensure the sustainable performance of the operating system [83].

However, the main challenges of the supply chain become evident in the stages of production, collection, pretreatment (drying), storage, transport, and point of sale, as a result of the fact that it is common for each process to make independent decisions, and not according to the global objectives, as well as the complexity of the coordination and cooperation environments that these environments deserve.

Previous work by Shen et al. [17] designed a transport decision tool for the optimization of the integrated biomass flow with vehicle capacity limitations, which consisted of the development of an improved mathematical model to solve the problem of synthesis of the multilevel biomass supply chain, including the selection of processing centers, the biomass allocation design, and the selection of the transport mode, taking into account the vehicle capacity constraint (weight and volume) and the penalty for carbon emissions [17]. In this research, a new, easy to use graphical decision-making tool was proposed for transport design in supply chain management; in addition, the potential of the suggested tools to provide an optimal rigid solution for the research problem addressed is highlighted. Finally, several potential future studies are suggested to fill some of the remaining research gaps.

Considering that the transport of biomass raw material to energy conversion facilities is among the main challenges for the use of biomass as a renewable source of energy, a framework was developed for optimally locating biomass collection points in order to improve the procedure for locating biomass based energy facilities, in a case study of Bolivia [22].

It is taken into account that, as part of the biomass collection procedure, agricultural waste is compacted into bales and accumulated at the biomass collection points (BCP) for collection and delivery by trucks to the conversion facilities. This work developed a framework for localizing BCP, using an iterative process model in a GIS environment. The developed BCP framework will improve the efficiency of biomass collection and the accuracy of the location of facilities based on this resource. Decision-makers can use these results to expand the application of biomass in the energy sector in Bolivia.

In order to help the biomass industry take hold, Cooper et al. [84] developed linear estimators of biomass yield maps. The proposed model successfully optimized the supply chain while considering the variability of a spatially distributed resource. It also found that the use of biomass yield estimates reduced the total land use by up to 17% in some cases and improved the biomass production by more than 7%. The improvement in biomass production was evidenced by the increase in the number of bioproducts generated and the increase in financial performance, thus demonstrating the importance of including yield variability in optimization. This model could be used for other spatially distributed resources, such as solar insolation or the availability of wind.

Synchronizing different vehicles performing interrelated operations can better use vehicle fleets and decrease distances traveled and nonproductive times, leading to reduced logistics costs. The proposed approach can improve planning and decision-making processes by providing valuable information on the impact of crucial biomass logistics parameters on routing results [13].

Eliasson et al. [85] examined moisture content management during the storage of logging residues at landings and the effects of hedging strategies. To increase the economic value of fuel, supply chain management must ensure that moisture content is minimized. One method is to cover the waste piles to reduce rewetting during storage. This research aimed to describe the effects on moisture content in covered and uncovered waste piles after storage, in cases with and without direct contact with the soil. The results varied between study sites, but the only method that consistently produced a drier fuel than the lack of cover was when the biomass cover had been placed below and above the chimneys, which produced the most reliable economic effect of the proven treatments and a more homogeneous fuel for the customer. Other related investigations are shown in Table 2, where their contributions are described based on the proposals for optimization of the biomass supply chain and the stage in which they are applied.

Table 2.

Optimization of the processes linked to the biomass supply chain.

The specific context of the Dominican Republic determines that it is in the biomass transport stage where there is the greatest need to implement improvements in the value chain. The use of linear programming mathematical models is required, where specialists evaluate the cost and effectiveness variables through the application of simulations. Currently, models are being implemented that could significantly help to add value to the supply chain where, through the approach of an objective function, calculations are carried out that seek to determine the optimal solutions that will lead the industry to minimize costs or maximize profits [113]. The spatial and temporal availability of these resources in the country, together with their energy potential, should be considered a starting point to decide the degree of using them in the energy mix and their possible contribution to electricity generation, linking them to other renewable energy sources.

4.3. Biomass Management Cost

Supply chain design has traditionally been linked to meeting customer demands at minimum cost. However, over time, the concept has been expanded to include other criteria, among which the minimization of environmental and social impacts stands out [114]. The complexity of estimating costs to produce energy from biomass depends on regional variability in production costs and the supply of raw materials, and the wide diversity of conversion technologies associated with the energy use process. Among the main factors that directly affect bioenergy production costs, the following can be mentioned [115]:

- Those associated with crop production: land and labor costs, crop yields, prices of various inputs (such as fertilizers), water supply, and the management system linked to processes such as mechanized and manual harvesting, among others;

- In situ biomass milling or densification process;

- Those related to the transfer of biomass from the source to a conversion plant: the spatial distribution of biomass resources, the transport distance and the means for it, and the deployment and timing of pretreatment technologies in the chain;

- Those generated from the final conversion of biomass to energy carriers, including the conversion scale, means of financing, plant factors, production and value of co-products, and final costs of conversion in the production plant. Such significant players depend on different locations and technologies. The typology corresponding to the energy carrier used in the conversion process influences the mitigation potential of climate change.

A wide variety of studies have been conducted in these areas. One of them was carried out by Saygin et al. [116], who evaluated the technical and economic potentials of the use of biomass for the production of steam, chemical products, and polymers, assuming that the replacement of fossil fuels by biomass of the restored measure reduces carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. In this work, the effect of the cost of raising industrial steam and the production of materials from biomass is estimated, and their long term global potentials are quantified, including energy savings, reduction in CO2 emissions, cost, and availability of resources.

The authors further indicated that there are profitable opportunities for the production of equipment from biomass waste and by substituting high value petrochemicals that, together, would require more than 20 exajoules (EJ) of biomass. Worldwide, in addition to the base for 2030, potentials could double by 2050 and reach 38–45 EJ (25% of total industrial energy use), with the highest demand in Asia and other developing and transition economies. The exploitation of these potentials depends on energy prices and the industry’s access to biomass supply, which is already attractive due to its high efficiency in reducing CO2 emissions per unit of biomass.

In this same area, Jackson and Ferreira [117] studied woody biomass processing and estimated the possible economic impacts in rural regions. This paper identifies the economic and environmental impacts of introducing woody biomass processing (WBP) in a rural area in central Appalachia. It was concluded that, because long term economic development strategies in rural regions are limited and negative impacts do not drastically alter the regional environmental profile, regional policymakers should include WBP among their portfolio options.

Cardoso et al. [24] carried out a techno-economic analysis of a biomass gasification power plant that deals with mixtures of forest residues to produce electricity in Portugal. As a result of deadly forest fires in central and northern Portugal in 2017, the government launched a set of forest policies that promote the increase in the currently installed forest biomass combustion thermal power plant. Concerning this, the authors above analyzed, from a techno-economic perspective, an 11 MW gasification power plant as a cleaner alternative to traditional combustion plants, which deals with forest biomass mixtures in the central region of Portugal. The results predict the viability of the project: an NPV of 2367 MV, IRR of 8.66%, and PBP of 23.1 years. The sensitivity analysis foresees affordable risks for investors and that the NPV of the project is highly susceptible to the sale price and the production of electricity. Despite the viability of the project delivered by the economic model, it was determined that the economic performance depends mainly on the income from electricity sales regulated by uncertain rates and reimbursements. Therefore, the results suggest that special conditions regarding the project’s attractiveness for potential investors should be considered.

In this same line of research, Wang et al. [118] made a techno-economic analysis of the biomass to hydrogen process compared to the carbon to hydrogen process. In this work, the simulation of biomass to hydrogen processes was validated using the experimental data available from the literature. Based on the simulation results, a techno-economic analysis was carried out from the points of view of the first and second laws of thermodynamics, which included the determination of energy efficiency, material consumption, investment of total capital, production costs, and carbon taxes. The energy analysis results of the addressed processes showed that the energy efficiency could be improved from a thermodynamic perspective. The combination of thermodynamic analysis and techno-economic performance evaluation provides information on the improvement and performance of clean hydrogen production.

Finally, Shen et al. [17] showed the prospects and challenges of marketing the biomass industry in Malaysia. The study considers that biomass, converted into biobased ecological products, can achieve a more balanced carbon cycle through circular utilization. Therefore, the development of the biomass industry seems to be a priority area and is a crucial step to motivate the global circular economy and sustainability. However, due to trade barriers, the biomass industry in developing countries, such as Malaysia, is not keeping pace with the increase in the country’s gross domestic product. This paper summarizes the development barriers and challenges facing the biomass industry in Malaysia; recommendations have been proposed covering technological innovation, logistics management, the interaction between academia and industry, policies and application, social impact, and international benchmarking. These recommendations can be good references for developing the biomass industry in Malaysia and a reflection for other developing countries with biomass resources in promoting the sustainability and marketing of products. The role of five critical stakeholders in the commercialization of biomass technologies is highlighted in the present review. Some other studies linked to the estimation of biomass costs based on their proposals to guarantee the profitability of their use are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Profitability of the use of biomass as a source of energy.

Another challenge decision-makers face is considering the transportation network as the central management component in the biomass supply chain. It must be understood that the transport of biomass is focused on how and when to obtain intermediate products and finished products from their respective origins to their final destinations. In this sense, each supplier will be able to implement strategic and tactical decisions to reduce costs and improve service levels for local customers and export in a receptive, economic, and sustainable transport network. Biomass transportation represents a significant part of its final price, in addition to the fact that this itself requires fuel, the combustion of which adds to GHG emissions [130]. Hence, in quantifying the economic and environmental sustainability of the use of biomass as an energy source, it is necessary and essential to take into account such emissions and the resulting cost of transportation [98].

In the Dominican Republic, the National Energy Commission determined that one of the current difficulties expressed by the biomass market players is the deficient access to forest farms and the little government support in the logistics and access roads aspect, which causes transportation costs to be higher. In addition, “the tax incentives for renewable energies at 40% are insufficient and should reach 75%”. On the other hand, the distance between the processed biomass collection centers and the consumers should not exceed 150 km for the operation to be profitable. In general, “the cost of transportation is a limiting factor in the feasibility of the biomass market, and the proximity between biomass sources and the final consumer is key for the long-term sustainability of the market” [39].

There is still a need in the Dominican energy scenario to define elements related to the cost of biomass energy use, a resource available and not yet sufficiently exploited, mainly due to the low level of knowledge of the existing biomass potentials as well as their spatial location and temporal availability. These elements will allow the evaluation of this energy resource with electricity generation with intermittent renewables and considering biomass as a complementary energy resource to achieve stability in a generation without the need to incur fossil fuel generation or cause interruptions in electricity service.

4.4. Conversion Processes

Mohd and Hashim [74] provided an overview of coal–biomass co-combustion regarding the methods used to convert biomass into energy. It was started from the fact that the energy sector on the global stage faces the great challenge of providing energy at an affordable cost, while taking into account the protection of the environment. Co-combustion of coal with biomass for electricity generation has gradually gained ground, even though its combustion occurs differently due to significant variations in its physical and chemical properties. The research reported in this work reflects the potential of biomass fuel and the scope of maximizing its proportion in the mix in coal fired power generation plants and its benefits.

Heidenreich and Ugo [133] introduced new concepts in biomass gasification, which is considered a key technology for its use; to promote this technology in the future, advanced, cost effective, and highly efficient gasification processes and systems are required. Such research provides a detailed review of new concepts in biomass gasification. Likewise, it is suggested that polygeneration strategies for producing multiple energy products from biomass syngas offer high efficiency and flexibility.

For their part, Ronia et al. [134] made a global review of biomass co-generation technology with policies, challenges, and opportunities, taking into account that the urgency to reduce GHG emissions is increasing and that all countries around the world have begun to invest a substantial amount of resources in renewable energy sources. The work reviewed the central policies that have promoted the co-combustion of biomass at the international level. Furthermore, existing co-combustion plants with technologies and the availability of biomass resources in different countries were examined. Finally, the main global biomass co-combustion initiatives and their perspectives were summarized to ensure the renewable energy objectives.

Additionally referring to biomass conversion processes, Sharifzadeh et al. [135] reviewed the state of the art and future research directions regarding the multiscale challenges of rapid biomass pyrolysis and bio-oil enhancement, under the knowledge that rapid biomass pyrolysis is potentially one of the cheapest routes to renewable liquid fuels. However, their commercialization poses a challenge on multiple scales, starting with the characterization of raw materials, products, and intermediates at molecular scales, and continuing with the understanding of the complex reaction network that takes place in different reactor configurations and the case of catalytic pyrolysis and improvement in different catalysts. This study provides a comprehensive multiscale review that discusses the innovation of these aspects and their multiscale interactions. The research is focused on fast pyrolysis, although reference is made to other types of pyrolysis technologies for the sake of comparison and knowledge transfer. In terms of proposals to increase efficiency, other investigations related to biomass conversion processes are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

The efficiency of the biomass conversion process.

The substitution of traditional bioenergy uses for modern forms of energy in the Dominican Republic shows an evident need for advances in the efficiency of conversion technologies and the devices currently used, as well as the production of charcoal for stoves [39].

Using the existing biomass potential in the Dominican Republic for energy purposes is conditioned to studies of potentials both in the case of residual and woody biomass and its characterization, and the correct selection of the most suitable route for its use. The excellent link of these previously exposed factors will bring with it the feasibility of using biomass in the Dominican energy mix, an element that, as already explained, directly influences the improvement of the stability of electricity generation with renewable energy sources to be considered a manageable energy resource.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

The most significant conclusions of this study are summarized based on the research trends exposed from the different perspectives addressed:

5.1. Environmental Impact

- The dependence of today’s society on fossil fuel resources and their consequent negative influence on climate change has led to the rethinking of how energy is produced and consumed. The studies reiterate the emergence of serious environmental problems due to fossil fuels; thus, biomass has sparked growing interest as a promising renewable energy.

- Despite the belief that wood and biomass combustion is entirely safe and does not have adverse effects on a social and environmental level, some research disputes this claim, arguing that biomass cannot be considered ecological even though it is a renewable fuel. Its emissions are too high and comparable to coal combustion, which is scientifically debatable. Hence, it is suggested to deepen the review of other studies to issue solid conclusions in this regard.

- Solid biomass is the only source of renewable energy with practical use in the industrial field, so it is essential to identify its current employment in the sector to analytically project its future use and define global strategies for heat production. The pressure on the use of ecological energy resources in the industrial sector is increasing, so it is essential to consider their control and sustainability.

5.2. Supply Chain

- The aforementioned mathematical models provide solutions to some problems related to the biomass supply chain, including selecting processing centers, the design of biomass allocation, the selection of the mode of transport, and the evaluation of the environmental impact in order to facilitate decision making.

- Other models use geographic information systems and the spatial distribution of biomass and road maps to select areas with high availability located close to the conversion centers. These simulations improve the efficiency of biomass collection and precision in the location of the facilities, allowing decision makers to use the results for the expansion of the application of biomass in the energy sector.

- Supply chain optimization is a tool that has been used to help the biomass industry gain a foothold; for this, models are also used to generate yield maps based on reference data on the quality of the available land, which more accurately suggest decision-making on the quantity and location of biomass growth operations.

- Additionally, simulations that address the collection and delivery of full truckloads can provide helpful information on the impact of critical parameters of biomass logistics on routing results, increasing the efficiency of transportation planning processes.

- Regarding biomass storage, it is necessary to consider that, to maximize the economic value of the fuel, supply chains must be managed so that moisture content is reduced to a minimum, for which various treatments are being tested to obtain more homogeneous fuels that generate reliable economic effects.

5.3. Costs

- In addition to the environmental impact, it is pertinent to evaluate the technical and economic potentials of using biomass for energy purposes, among which energy saving, reduction in CO2 emissions, cost, and availability of resources stand out.

- Woody biomass processing is one of the most viable alternatives for generating energy and reducing dependence on imports, offering opportunities to stimulate regional economies, especially in rural regions where development options in this sector are often limited.

- Techno-economic analyses of biomass conversion plants can include measuring the economic performance, estimating the investment risk, and evaluating the environmental impact under special conditions concerning the project’s attractiveness.

- Other analyses are oriented to the simulation of biomass processes that include the determination of energy efficiency, material consumption, total capital investment, production costs, and carbon taxes, and providing information on the improvement and operation of biofuel production.

- The development of the biomass industry is suggested to be a motivating factor for the global circular economy and sustainability in developing countries; however, it faces a series of commercialization barriers and challenges, the analysis of which allows the generation of recommendations that cover the areas of technological innovation, logistics management, the interaction between academia and industry, policies and application, social impact, and international benchmarking.

5.4. Conversion Processes

- Using coal with biomass as a complementary fuel in combustion or gasification processes is a viable technological option to reduce fossil fuel emissions. Some research shows the potential of biomass fuel and the scope of maximizing its proportion in the mix in coal based power generation plants and the benefits derived from it.

- In biomass, gasification is considered a key technology, the promotion of which requires advanced, profitable, and highly efficient processes and systems. Hence, there is a need to investigate the concepts for the integration and combination of processes that aim to allow greater efficiency, better quality and purity of gas, and lower investment costs.

- The joint combustion of biomass can have a very influential role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions, since it can reduce the possible environmental impacts associated with the combustion of fossil fuels; for this, it is necessary to study the main global biomass co-combustion initiatives and their perspectives to ensure the goal of renewable energy.

- According to its potential as one of the cheapest routes to renewable liquid fuels, it is pertinent to analyze the challenges in using rapid pyrolysis of biomass.

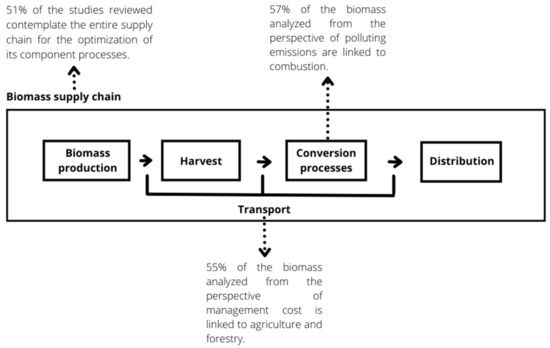

Figure 1 shows that about 51% of the studies reviewed contemplate the entire supply chain for the optimization of its component processes, 57% of the biomass analyzed from the perspective of polluting emissions are linked to combustion and 55% of the biomass analyzed from the perspective of management cost is linked to agriculture and forestry. This information makes it possible to understand the trends linked to biomass studies.

Figure 1.

Trend of studies linked to the biomass supply chain.

This research provides a simplified compilation of an invaluable body of knowledge that is particularly useful for evaluating the integration of renewable energy technologies in any economic sector based on the optimal use of residual biomass, for which it is used as a general procedure in the analysis and modeling of the logistics system due to its significant influence on the decision-making process.

It is necessary to develop methodologies that allow the identification of the natural stocks of bioenergy resources and their production potential at the country scale. In addition to carrying out studies aimed at optimizing the supply of biomass—in order to improve the management practices of its production, collection, and distribution systems, as well as the technologies for converting this resource into energy—the development of multipurpose management systems (mainly agricultural and forestry), the search for promising forest species, the development of efficient conversion technologies, and their profitability should be considered.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.G.-B. and I.L.-D.; methodology, H.G.-B.; writing—original draft preparation, H.G.-B.; writing—review and editing, H.G.-B., M.A.-M. and J.A.d.F., supervision, J.A.d.F. and I.L.-D.; funding acquisition, INTEC. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Instituto Tecnológico de Santo Domingo (INTEC) grant number CBA-332202-2019-P- And The APC was funded by Instituto Tecnológico de Santo Domingo (INTEC).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Instituto Tecnológico de Santo Domingo (INTEC) for the financial support of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| GHG | greenhouse gas |

| IRR | internal rate of return |

| PBP | payback period |

| NPV | net present value |

| CO2-e | carbon dioxide equivalent |

| Bbl | barrel |

| ROI | return on investment |

| USD | United States dollar |

| MW | megawatt |

| GJ | gigajoules |

| TEA | techno-economic analysis |

| BSP | biomass steam processing |

References

- Ahmadvand, S.; Khadivi, M.; Arora, R.; Sowlati, T. Bi-objective optimization of forest-based biomass supply chains for minimization of costs and deviations from safety stock. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2021, 11, 100101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajardo-Ronquillo, V.P. Incidencia de la Caída de los Precios del Petróleo en la Economía Latinoamericana. Polo Del Conoc. 2020, 5, 1054–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Tarighaleslami, A.; Ghannadzadeh, A.; Atkins, M.; Walmsley, M. Environmental Life Cycle Assessment of a Cheese Production Plant towards Sustainable Energy Transition: Natural Gas to Biomass vs. Natural Gas to Geothermal. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 122999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Haseeb, M.; Mahmood, H.; Alkhateeb, T.T.Y.; Murshed, M. Renewable energy use and ecological footprints mitigation: Evidence from selected South Asian economies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nava, C. El acuerdo de París. Predominio del soft law en el régimen climático. Boletín Mex. De Derecho Comp. 2016, 147, 99–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cano, J. Estudio de Caso: El Auge de las Energías Renovables; Institución Universitaria Politécnico Grancolombiano: Bogotá, Colombia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Casteló, A. Diseño de un Sistema Sostenible de Calefacción para una Vivienda Mediante una Energía de Biomasa; Universidad Politécnica de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, J. Análisis de la Problemática de Investigación de Aspectos Avanzados de la Generación Eléctrica con Biomasa. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de la Rioja, Barcelona, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Popp, J.; Kovacs, S.; Olah, J.; Diveki, Z.; Balazs, E. Bioeconomy: Biomass and biomass-based energy supply and demand. New Biotechnol. 2021, 60, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, S.; Lautala, P.; Handler, R.M. Securing the feedstock procurement for bioenergy products: A literature review on the biomass transportation and logistics. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 200, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, A.C.; Palumbo, M.; Pelagagge, P.M.; Scacchia, F. Economics of biomass energy utilization in combustion and gasification plants: Effects of logistic variables. Biomass Bioenergy 2005, 28, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKendry, P. Energy production from biomass (part 2): Conversion technologies. Bioresour. Technol. 2002, 83, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, R.; Marques, A.; Amorim, P.; Rasinmäki, J. Multiple vehicle synchronisation in a full truck-load pickup and delivery problem: A case-study in the biomass supply chain. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 277, 174–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malladi, K.T.; Sowlati, T. Biomass logistics: A review of important features, optimization modeling and the new trends. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 94, 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Osmani, A.; Awudu, I.; Gonela, V. An integrated optimization model for switchgrass-based bioethanol supply chain. Appl. Energy 2013, 102, 1205–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How, B.S.; Ngan, S.L.; Hong, B.H.; Lam, H.L.; Ng, W.P.Q.; Yusup, S.; Ghani, W.A.W.A.K.; Kansha, Y.; Chan, Y.H.; Cheah, K.W. An outlook of Malaysian biomass industry commercialisation: Perspectives and challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 113, 109277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Yang, K.L.H. Transportation decision tool for optimisation of integrated biomass flow with vehicle capacity constraints. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 136, 197–223. [Google Scholar]

- Buffat, R.R.M. Spatio-temporal potential of a biogenic micro CHP swarm in Switzerland. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 103, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charis, G.; Danha, G.; Muzenda, E. A review of the application of gis in biomass and solid waste supply chain optimization: Gaps and opportunities for developing nations. Detritus 2019, 6, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cintas, O.; Berndes, G.; Englund, O.; Cutz, L.; Johnson, F. Geospatial Supply–Demand Modeling of Biomass Residues for Cofiring in European Coal Power Plants; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Larson a, J.; Yu, E.; English, B.; Jensen, K.; Gao, Y.W.C. Effect of outdoor storage losses on feedstock inventory management and plant-gate cost for a switchgrass conversion facility in East Tennessee. Renew. Energy 2015, 74, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morato, T.; Vaezi, M.K.A. Developing a framework to optimally locate biomass collection points to improve the biomass-based energy facilities locating procedure—A case study for Bolivia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 107, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Li, X.; Yao, Q.; Chen, Y. Challenges and models in supporting logistics system design for dedicated-biomass-based bioenergy industry. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 1344–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, J.; Silva, V.E.D. Techno-economic analysis of a biomass gasification power plant dealing with forestry residues blends for electricity production in Portugal. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 7412753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, M.; Ruiz, M.; Del Campo, A.; Garcia, A.; Francés, F.y.L.C. Managing low productive forests at catchment scale: Considering water, biomass and fire risk to achieve economic feasibility. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 231, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nicoletti, J.; Ning, C.Y.F. Incorporating agricultural waste-to-energy pathways into biomass product and process network through data-driven nonlinear adaptive robust optimization. Energy 2019, 180, 556–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Thunman, H.S.H. A fast-solving particle model for thermochemical conversion of biomass. Combust. Flame 2020, 213, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, L.; Bretón, D.; Pérez, R.y.A.L. Métodos de Estimación de la Biomasa Potencial. 2012. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280086387_Metodos_de_estimacion_de_la_biomasa_potencial (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Pohekar, S.D.; Ramachandran, M. Application of multi-criteria decision making to sustainable energy planning—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2004, 8, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, C.M.R. Microalgae-Based Biofuels and Bioproducts: From Feedstock Cultivation to End-Products; Woodhead Publishing Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bolivar, R.A.; Mostany, J.; del Carmen García, M. Petróleo versus energías alternas. Dilema futuro. Interciencia 2006, 31, 704–711. [Google Scholar]

- Demirbaş, A. Biomass resource facilities and biomass conversion processing for fuels and chemicals. Energy Convers. Manag. 2001, 42, 1357–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clery, D.S.; Vaughan, N.E.; Forster, J.; Lorenzoni, I.; Gough, C.A.; Chilvers, J. Bringing greenhouse gas removal down to earth: Stakeholder supply chain appraisals reveal complex challenges. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2021, 71, 102369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titov, A.; Kövér, G.; Tóth, K.; Gelencsér, G.; Kovács, B. Acceptance and Potential of Renew-able Energy Sources Based on Biomass in Rural Areas of Hungary. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerma Arce, V. Planificación, Logística y Valorización de Biomasa Forestal Residual en la Provincia de Valencia; Universitat Politècnica de València: Valencia, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mariano, F. Meta de producción de los 300 MW en biomasa para el año 2030. In Bioenergía Dominicana; Revista del Proyecto de Bioelectricidad Industrial: Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- IRENA. Prospectivas de Energías Renovables: República Dominicana, REmap 2030. 2016. Available online: https://www.cne.gob.do/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/2820172920ESP20REmap20RD202030.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Espinasa, R.; Balza, L.; Hinestrosa, C.; Sucre, C. Dossier energético: República Dominicana; Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Frías, A.; Checo, H.; Reyes, J. Estudio de la Producción Actual y Potencial de Biomasa en República Dominicana y su Plan de Aprovechamiento para la Generación de Energía; Comisión Nacional de Energía: Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, C.y.C.C. Mix de Generación en el Sistema Electrico Español en el Horizonte 2030; Foro de la Industria Nuclear Española: Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Carbajo, J. La Integración de las Energías Renovables en el Sistema Eléctrico; Fundación Alternativas: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweers, W.; Bai, Z.; Campbell, E.; Hennenberg, K.; Fritsche, U.; Mang, H.-P.; Lucas, M.; Li, Z.; Scanlon, A.; Chen, H.; et al. Identification of potential areas for biomass production in China: Discussion of a recent approach and future challenges. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 2268–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochs, A.; Konold, M.; Lucky, M.; Musolino, E.; Weber, M. Hoja de Ruta para un Sistema de Energía Sostenible: Aprovechamiento de los Recursos de Energía Sostenible de la República Dominicana; Worldwatch Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahraee, S.M.; Shiwakoti, N.; Stasinopoulos, P. Biomass supply chain environmental and socio-economic analysis: 40-Years comprehensive review of methods, decision issues, sustainability challenges, and the way forward. Biomass Bioenergy 2020, 142, 105777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, V.; Lehtveer, M.; Göransson, L. Biomass in the electricity system: A complement to variable renewables or a source of negative emissions? Energy 2019, 168, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-J.; Jing, Y.-Y.; Zhang, C.-F.; Zhao, J.-H. Review on multi-criteria decision analysis aid in sustainable energy decision-making. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 2263–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droege, P. Contributor Biographies. In Urban Energy Transition; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez, J. Los Sistemas de Información Geográfica en la Planificación e Integración de Energías Renovables; CIEMAT: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Velázquez, B. Situación de los sistemas de aprovechamiento de los residuos forestales para su utilización energética. Ecosistemas Rev. Científica Ecol. Medio Ambiente 2006, 15, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, J.; Yi, W.; Cai, H.; Li, Y.; Su, Z. Agri-biomass supply chain optimization in north China: Model development and application. Energy 2022, 239, 122374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Paz, C.; Domínguez, J.y.P.M. Metodología SIG para la Localización de Centrales de Biomasa mediante Nota Multicriterio y Análisis de Redes. In Modelos de Localización-Asignación para el Aprovechamiento de Biomasa Forestal; CIEMAT: Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Long, H.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Jia, J. Biomass resources and their bioenergy potential estimation: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 26, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Hu, H.; Wang, S.; Rodriguez, L.F.; Ting, K.; Lin, T. Multiperiod stochastic programming for biomass supply chain design under spatiotemporal variability of feedstock supply. Renew. Energy 2022, 186, 378–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, L.J.R.; Causer, T.P.; Ciolkosz, D. Biomass for energy: A review on supply chain management models. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 120, 109658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamed, T.; Tian, L.; Zhang, Y.; Ting, K.C. A review of remote sensing methods for biomass feedstock production. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 2455–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirante, R.; Bruno, S.; Distasoa, E.; La Scalab, M.T.P. A biomass small-scale externally fired combined cycle plant for heat and power generation in rural communities. Renew. Energy Focus 2019, 28, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro Cerrillo, R.M.; Palacios Rodríguez, G.; Clavero Rumbao, I.; Lara, M.Á.; Bonet, F.J.; Mesas-Carrascosa, F.-J. Modeling major rural land-use changes using the GIS-based cellular automata metronamica model: The case of Andalusia (Southern Spain). ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnansounou, E.; Pandey, A. Life-Cycle Assessment of Biorefineries; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- CNE. Reglamento de la Ley 57-07; Comisión Nacional de Energía: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Özyuguran, A.Y.S. Prediction of Calorific Value of Biomass from Proximate Analysis. Energy Procedia 2017, 107, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauser, N.M.; González, G.; Mendieta, C.M.; Kruyeniski, J.; Area, M.C.; Vallejos, M.E. Biomass waste as sustainable raw material for energy and fuels. Sustainability 2021, 13, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broek, R.; Faaij, A.; Wijk, A. Biomass combustion power generation technologies. Biomass Bioenergy 1996, 11, 271–281. [Google Scholar]

- Abascal, R. Estudio de la Obtención de Bioetanol a Partir de Diferentes Tipos de Biomasa Lignocelulósica. Matriz de Reacciones y Optimización; Trabajo de fin de grado; Universidad de Cantabria, Escuela Politécnica de Ingeniería de Minas y Energía: Cantabria, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala-Mendivil, N.; Sandoval, G. Bioenergía a partir de residuos forestales y de madera. Madera Bosques 2018, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mboumboue, E.N.D. Biomass resources assessment and bioenergy generation for a clean and sustainable development in Cameroon. Biomass Bioenergy 2018, 118, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielgosinski, G.; Łechtanska, P.N.O. Emission of some pollutants from biomass combustion in comparison to hard coal combustión. J. Energy Inst. 2016, 90, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, J. La Ciencia Irrumpe Contra la Biomasa Forestal para Energía, pero También en su Defensa. Energías Renovables. 2018. Available online: https://www.energias-renovables.com/bioenergia/la-ciencia-irrumpe-contra-la-biomasa-forestal-20181029 (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Malico, I.; Nepomuceno, R.; Gonçalves, A.S.A. Current status and future perspectives for energy production from solid biomass in the European industry. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 112, 960–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Liu, Y.; Lin, B. Should China support the development of biomass power generation? Energy 2018, 163, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbas, A. Potential applications of renewable energy sources, biomass combustion problems in boiler power systems and combustión related environmental issues. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2005, 31, 171–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, D.; Grim, G.; Nelson, E.; Tan, E.; Ruddy, D.; Hernandez, S.; Westoverb, T.; Hensley, J.; Carpenter, D. High-Octane Gasoline from Biomass: Experimental, Economic, and Environmental Assessment. Appl. Energy 2019, 241, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambarotta, A.; Morini, M.; Zubani, A. A Model for the Prediction of Pollutant Species Production in the Biomass Gasification Process. Energy Procedia 2017, 105, 700–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, C.; Alves, E.; Oliveira, A.; Borges, F.; Ribas, L.; Vakkilainene, E.C.M. Characterization of residual biomasses from the coffee production chain and assessment the potential for energy purposes. Biomass Bioenergy 2019, 120, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Idris, M.N.; Hashim, H.; Razak, N.H. Spatial optimisation of oil palm biomass co-firing for emissions reduction in coal-fired power plant. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 3428–3447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, B.G.; Kiah, M.H.M.; Irshad, A.; Andrews, G.E.; Phylaktou, H.N.; Li, H.; Gibbs, B.M. Rich biomass combustion: Gaseous and particle number emissions. Fuel 2019, 248, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfau, S.; Hanssen, S.; Straatsma, M.; Koopman, R.; Leuven, R.H.M. Life cycle greenhouse gas benefits or burdens of residual biomass from landscape management. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 220, 698–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]