Abstract

Education is the foundation of basic human rights and the peace of mankind as well as the pursuit of sustainable development. In this article, we have developed a blockchain-centered educational program contributing to Goal 4, Quality Education, among the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Education for SD (ESD). The education program featured herein consisted of three lessons in total and has been developed to accommodate gamification techniques. We implemented the education program on 704 elementary school students in Korea for three years from 2019 to 2021. The effectiveness of the education program was primarily analyzed by paired t-test and technical statistics analysis. In a pre-and post-education survey, digital literary, literacy, and numeracy were all significantly improved, with satisfaction level rated at 3.91 out of 5 points. We hope that the blockchain-themed education program proposed herein will provide implications for the promotion of inclusive and equitable quality education.

1. Introduction

The 2015 United Nations (UN) General Assembly adopted the ‘2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)’ to be achieved by individual countries and the international community in 17 categories by 2030. Education is a critical element of the sustainable development agenda, and it has been reflected in SDG4-Education 2030 [1]. These goals are building upon the outcomes and limitations of various past education agendas, for example, ‘EFA, Education For All’ and ‘Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)’, the ‘Incheon Declaration’ from World Education Forum (WEF) hosted by Korea in 2015, and the ‘SDG4-Education 2030 Framework for Action’ suggested education goals to be achieved by the whole world by 2030 [2]. The goal of SDG4-Education is to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and empower lifelong learning opportunities for all. To that end, the UN put forward the following seven targets in connection with Goal 4 [3].

- Goal 4.1: Free Primary and Secondary Education

- Goal 4.2: Equal Access to Quality Pre-Primary Education

- Goal 4.3: Equal Access to Technical/Vocational and Higher Education

- Goal 4.4: Increase the Number of People with Relevant Skills for Financial Success

- Goal 4.5: Eliminate All Discrimination in Education

- Goal 4.6: Universal Literacy and Numeracy

- Goal 4.7: Education for Sustainable Development and Global Citizenship

Given the suggested targets and implementation tools, SDG4-Education 2030 is a universal agenda for all nations, extensively pursuing lifelong learning opportunities for all, featuring a new focus on inclusiveness, equitability, and gender equality, and emphasizing the effectiveness, appropriateness, etc. of learning [2,3].

The education program proposed herein has adopted gamification techniques to converge education with game elements and to contribute to achieving the SDGs; this research has come up with the following three questions in consideration of the educational landscape and context in Korea:

- Does the blockchain-centered education proposed herein contribute to ‘Goal 4.1 Free Primary and Secondary Education’?

- Does the blockchain-centered education proposed herein contribute to ‘Goal 4.4 Increase the Number of People with Relevant Skills for Financial Success’?

- Does the blockchain-centered education proposed herein contribute to ‘Goal 4.6 Universal Literacy and Numeracy’?

This article proposes an education program that can teach elementary students the blockchain that can be a foundation to fostering innovative industries of the future. We expected the education program to contribute to achieving particularly 4.1, 4.4, and 4.6 targets in support of Goal 4. To be more specific, we are confident that blockchain education will enable quality elementary education and ensure gender equality in education by allowing all to readily understand regardless of their gender. Furthermore, we believe that the program will improve literacy and numeracy, enhance digital literacy, and foster talents that understand blockchain technology in a bid to contribute to the ESD and the shared development of the entire world.

2. Related Research

2.1. Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) in Korea

The UN adopted the SDGs in 2015 and has proposed and implemented a wide range of implementation initiatives and actionable strategies in support of such goals ever since, emphasizing exchange and cooperation. Against this backdrop, Korea hosted the ‘Incheon Declaration’ in 2015 with awareness of potential marriage between sustainability and education, proactively engaging in international partnership endeavors in prospect for and carrying out educational initiatives with bearing on the SDGs [4]. In particular, the ESD emphasizes that the agendas of SDG4-Education 2030 must contribute to learning contents for the survival and prosperity of mankind as critical elements of SDG4 and key drivers of other goals.

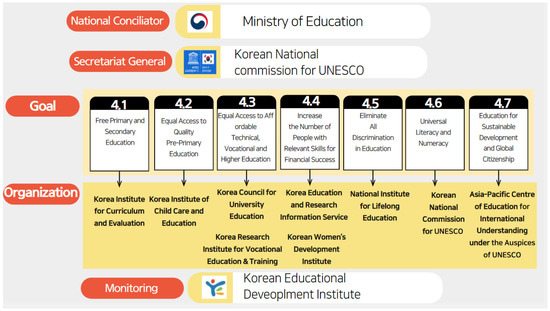

The SDG4 governance framework of Korea is built on two pillars: one is the activities of the SDG4-Education 2030 Council and the other is the private–public–academic collaboration activities launched by the Ministry of Environment and the Presidential Commission on Sustainable Development (PCSD) in support of the Korean SDGs (K-SDGs). Represented in the SDG4-Education 2030 Council are 10 government agencies including the Korean National Commission for UNESCO (UNESCO Korea), the Korea Educational Development Institute (KEDI), the National Institute for Lifelong Education (NILE), the Asia-Pacific Centre of Education for International Understanding (APCEIU), the Korea Institute for Curriculum and Evaluation (KICE), the Korea Education and Research Information Service (KERIS), the Korea Institute of Care and Education (KICCE), the Korean Center for University Education (KCUE), the Korea Research Institute for Vocational Education and Training (KRIVET), and the Korean Women’s Development Institute (KWDI), whereas the SDG4-Education 2030 Council is joined by the aforementioned agencies and the Ministry of Education (International Education Liaison Officer, Educational Statistics Division) and the Statistics Korea (KOSTAT) (Statistics Research Institute, Statistics Training Institute) in addition. Figure 1 shows the competent government agencies represented in the SDG4-Education 2030 Council of Korea and put in charge of the targets of SDG4.

Figure 1.

K-SDG4-Education 2030 Network.

While Korea has been endeavoring to fulfill the SDGs, promoting the EDS as described above, some challenges remain outstanding in the way forward. Speaking of Goal 4.1 to begin with, although Korea features a relatively higher level of academic performance [5], on the other side, a minority of young learners out of formal education reveal that they have undergone problems such as living in seclusion, NEET (Not in Education, Employment, or Training), running away from home, or offense; in addition, they rarely make career decisions [6]. Secondly, in terms of Goal 4.2, admission rates of young children aged 3 to 5 to kindergartens or daycare centers have not dipped below 90% since 2013 [7,8]. In terms of Goal 4.3, as Korea highly depends on private universities for tertiary education, tertiary education is deemed structurally accessible to most students [9]. In terms of Goal 4.4, ever since it became an ICT powerhouse, Korea has been rated low in terms of utilization of or attitude toward digital technologies. Furthermore, self-efficacy for digital technology utilization capability was found to be low, which calls for improvement of digital literacy [10]. With regard to Goal 4.5, Korea has endeavored significantly to promote gender equality in education, achieving improvements in many areas. Currently, the school enrollment rate of female students in Korea is found to be higher or similar to that of male students. However, the problem is that the ratios of students taking science/engineering majors in universities are very unequal among different genders, with 80.9% of male students taking such majors and the ratio of female students standing a meager 19.1%. As science/engineering disciplines teach smart ICT and artificial intelligence, which are the keywords defining the 4th Industrial Revolution, it is critical to encourage female students to take science/engineering majors in undergraduate studies [8]. Speaking of Goal 4.6, a literacy survey targeting Korean adults found that the demographic segment associated with significantly low linguistic proficiency and numeracy accounted for approximately 7.2% of the entire population. The survey findings may imply that the overall literacy of the national population of Korea is high, but the problem is that the illiteracy ratio tends to be high among the female population, old-aged group, or rural residents. Accordingly, it is necessary to provide literacy education programs to the illiterate groups [11]. In terms of Goal 4.7, Global Citizenship Education (GCED) and ESD-related activities have been incorporated into the 2015 educational curricula of Korea, with public education addressing learning topics related to global culture and international citizenship [12]. However, as metrics related to ESD and GCED are not defined in the international arena, it is still challenging to gather strictly relevant data. Fostering sustainable development and enabling global citizenship education requires benchmarking metrics to be developed and the current status analyzed.

2.2. Blockchain Education and Gamification

Blockchain technology was first proposed by Satoshi Nakamoto in 2008 and it has been touted as an innovation enabler for a variety of industries including logistics, distribution, finance, healthcare, and so on. Blockchain is a type of distributed database managed over peer-to-peer networks, with transaction data ledgers not stored in a centralized server but across multiple nodes all connected by blockchain networks [13]. In particular, as many transactions and services delivered offline have been migrated to the online environment in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is now critical to ensure the reliability and security of data in the so-called ‘contactless’ era. Given the requirement, blockchain can be a key enabler of data reliability [14]. This is the reason why elementary students need to understand and learn blockchain technology. As children, potential leaders of the future, are exposed to the promising technology and motivated to learn about it early on, they are more likely to select blockchain-related jobs when they have to make a choice. Furthermore, the UN has named blockchain as an accelerator of SDG fulfillment, suggesting it as a solution to the global trust deficit disorder [15].

Convergence between blockchain and education is focused in most cases on the incorporation of blockchain technology in the Learning Management System (LMS) or other systems to store and manage evaluation data and/or personal data. Turkanovic, M. et al. implemented a blockchain-based higher education trust platform that could facilitate the scoring and grading system of tertiary education worldwide to provide integrated perspectives to various stakeholders affiliated with higher education institutions, business enterprises, and other organizations [16]. Sun, H. et al. conducted research that incorporated blockchain technology with online education. They argued that the blockchain could solve issues associated with the reliability of online courseware, authentication of school grades and certificates, privacy of individual students, sharing of courseware, etc. They suggested that the blockchain be used to solve the issues by providing trusted digital certificates, sharing learning resources on smart contract platforms, encrypting data, etc. [17].

Meanwhile, blockchain education is in its embryonic stage in Korea and across other parts of the world. In Korea, some universities started blockchain departments and training courses as early as 2018. Kukmin University, Dongguk University, Sogang University, and Hanyang University have launched blockchain departments to foster young talents well-versed in blockchain technology. These courses deal with the blockchain platforms, blockchain decentralized applications (dapps), public blockchain, distributed ledger, fintech, software, etc. [18]. Overseas educational institutions, including MIT, EU Business school, Fordham University, and Hochschule Mittweida University, are also conducting blockchain-related courses. Most schools have recently been running these blockchain education courses. While some schools conduct programs centered on blockchain technology itself, some schools divide programs by subdividing blockchain technology, and some departments are grafted with other fields.

There are far fewer blockchain education programs targeting children than those designed for adults. However, some have attempted to bring the topic to children in a more interesting way by utilizing board games or cartoons. Kim, J. et al. proposed a strategy to educate the founding principles of blockchain to elementary students by utilizing gamification, which includes educational games designed to teach the basic principles of blockchain and the governing mechanisms of public and private blockchains [19]. Gamification is intended to immerse players in the problem solving process and utilize game-playing strategies and mechanisms in non-game situations, implementing gamification applications based on knowledge about game mechanics, game users, human behaviors, mobile computing, etc., all consisting of games [20]. Gamification processing can be completed in a series of problem recognition, target setting, game rule making, game element determination, simulation, and feedback [20]. Furthermore, as gamification functions with a purpose other than simply playing, it can motivate learners to voluntarily engage in the learning process at school [21]. Immersion in learning inspired by gamification is reported to have a positive impact on learning attitude and class engagement [22,23]. In the case of application of gamification for programming study, the learning consistency of the subject showing a passionate demeanor was improved [24]. Being motivated by gaming rules, the learners had a high satisfaction on a leaderboard that allowed them to follow up on the progress, ranks, or points. Since game-based learning helps students comprehend complex knowledge in specific disciplines, it might lead to immersion in learning for long periods and accordingly obtain better learning outcomes [25]. Several studies also support that gamification has merits in terms of learner motivation, career decision, and affective domain [26,27]. Despite concerns that gamification would negatively influence learners, games in lessons have demonstrated latent strengths that act as a versatile tool to ameliorate existing problems in domestic, social, and psychological scopes [22]. As explained above, when cutting-edge technologies are taught to elementary students, the addition of fun elements such as games or cartoons helps young learners focus more intently on complex technological principles and understand them with more ease.

2.3. Literacies for SDG4

It is important to foster talents having various skills and literacies in fulfilling SDG4, which focuses on quality education. Firstly, digital literacy can be named as a global indicator for Goal 4.4 [28]. Digital literacy has a close bearing on one’s life, as everything is subject to digital transformation these days. Digital literacy is a competence required for accessing, managing, understanding, communicating, and securely creating information on digital devices [28,29]. Digital literacy encompasses a wide range of competencies including ICT literacy, computational thinking, information literacy, media literacy, and so on. Table 1 shows a global framework to measure digital literacy that can be used as an indicator supportive of the fulfillment of Goal 4.4 designed by UNESCO. This digital literacy domain covers basic knowledge of hardware and software, information and data literacy, communication and collaboration, digital content creation, safety, problem solving, and career-related competencies [29].

Table 1.

Digital literacy competencies.

Secondly, to fulfill Goal 4.6, a considerable ratio of the global population should be equipped with universal literacy and numeracy. First of all, literacy means a competence with which an individual can understand, evaluate, utilize and engage texts to belong to a society, fulfill his/her personal objectives, and develop his/her knowledge and potential, whereas numeracy is required for accessing, utilizing, interpreting, and communicating mathematical information and ideas to control and engage mathematical requirements in various situations unfolding in one’s life [30,31]. To numerically evaluate literacy and numeracy in Goal 4.6, the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), the International Survey of Reading Skills (ISRS), the Literacy-Assessment-and-Monitoring-Programme (LAMP), the Strategic Teaching and Evaluation of Progress (STEP), etc. are utilized [26]. The PIAAC is a test designed to evaluate the literacy and numeracy of adults, while the ISRS is a tool measuring primarily reading comprehension. The LAMP is a system evaluating and monitoring the literacy of adults and the STEP is an evaluation system tool to evaluate the competency of teachers for literacy education. The PIAAC managed by the OECD and designed to evaluate both literacy and numeracy is broken down to basic skill assessment and cognitive skill assessment. In the basic skill assessment, basic reading skills and basic numeracy are measured [32]. In the cognitive skill assessment, linguistic skills, numeracy, and adaptive problem solving skills are measured. Table 2 shows the areas and descriptions of the PIAAC assessment tool.

Table 2.

PIAAC assessment.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Procedure

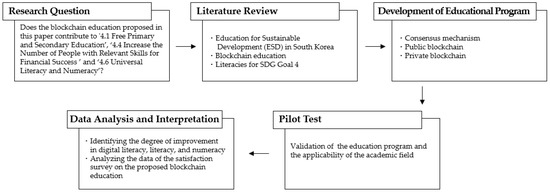

The purpose of this article is to provide a momentum that can facilitate the fulfillment of the sustainable development goals with the blockchain-themed education program proposed herein. To that end, a research topic is defined to begin with. The research topic is focused on Goals 4.1, 4.4, and 4.6 among the seven topics of SDG4 that Korea needs to fulfill with relative urgency. Therefore, the research topic is documented as, ‘Does the blockchain education proposed in this article contribute to SDG Goals ‘4.1 Free Primary and Secondary Education’, ‘4.4 Increase the Number of People with Relevant Skills for Financial Success’, and ‘4.6 Universal Literacy and Numeracy’?’.

Secondly, related research was conducted, with a study on the sustainability education status in Korea to begin with. Secondly, the significance of blockchain technology for the future and its potential for future jobs were studied and the current status of blockchain education ongoing in Korea and other countries was examined. Thirdly, research data were gathered on the digital literacy, literacy, and numeracy described in SDG Goal 4 and competencies required to be fostered for sustainable development. Data gathered and examined as above provided inputs for the design of the blockchain education program targeting elementary students in connection with the fulfillment of the sustainable development goals.

Fourthly, an education program based on learning games was designed in a blockchain-education-related study. Three learning games were developed for blockchain learning, and an education program consisting of three lessons was developed around the games.

Next, a pilot test was conducted to validate the feasibility and field applicability of the developed education program. Blockchain education was conducted on Korean elementary students once a year for three years.

Lastly, to analyze the educational outcomes, the satisfaction level of the participants in the blockchain-focused education program proposed herein was surveyed. Furthermore, the degree of improvement in the digital literacy, literacy, and numeracy of the research participants was identified before and after the education.

These analyses were intended to provide quantitative implications for whether the education program herein can be utilized as an instrument for the fulfillment of sustainable development goals. Figure 2 is the flowchart of the research procedure herein.

Figure 2.

Research procedure.

3.2. Research Participants

Elementary students in Korea were targeted by this research and participants were selected by judgment sampling. In consideration of the complexity of the blockchain concepts and the degree of understanding of the learning game rules, we decided that the blockchain education target elementary students in middle to upper grades. A total of 704 students participated in the research, with 69 from Jeju Island and Gyeongsangbukdo province in 2018, 232 from Gyeongsangbukdo, Gyeongsangnamdo, and Jeju provinces, and Seoul and Ulsan cities in 2019, and 403 from Gyeongsangbukdo and Gyeongsangnamdo provinces and Seoul city in 2020. Excluding insincere responses from the 704 research participants, we quantitatively analyzed the survey responses from 684 students. In 2018, one year after the development of the education program, the geographical scope of the program was limited to Jeju Island and Gyeongsangbukdo province, covering a relatively small number of students. However, in 2019, the scope was expanded nationwide to cover students in several regions. All the research participants were selected from students who had not received any blockchain education before.

3.3. Developed Blockchain-Centered Educational Program

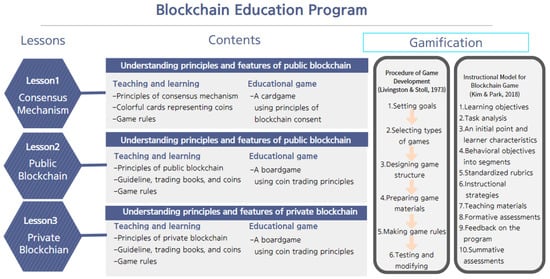

The blockchain-centered educational program proposed herein has been adapted from the blockchain learning game of Kim, J. et al. and expanded as an education program targeting elementary students [19]. We developed an education program designed to enable students to understand the consensus mechanism underpinning blockchain and two types of blockchain: public and private blockchains. The education program consists of three lessons in total, with Lesson 1 for consensus mechanism, Lesson 2 for public blockchain, and Lesson 3 for private blockchain. In all lessons, the students listen to the lectures of teachers first and play games as learning activities. Figure 3 shows the development process and contents of the education program.

Figure 3.

Blockchain education program.

In the blockchain education program, teachers explain the technological principles and concepts of blockchain to students for each topic in a conventional one-way lecture. Learning games are added to help elementary students understand relatively challenging concepts with ease and fun. All learning games were developed in accordance with the game development procedure suggested by Livingston, et al.: setting goals, selecting game types, designing game structure, preparing game materials, making game rules, and testing and modifying [33].

Firstly, the purpose of the game designed to help with the understanding of the consensus mechanism is to get all the cards of the opponent. The game materials to be prepared are cards. Cards required for the game are 18 total: 6 white cards, 6 blue cards, and 6 red cards. The same currency symbol is printed on the cards of all colors. The currency symbol is set to six different cryptocurrencies, including Bitcoin, Ethereum, Ripple, Litecoin, Dogecoin, and Bitcoin cash. The game can be started when the cards are ready. Firstly, a game party of two people is organized. A total of 36 cards are needed, 18 for each player. The party members put six white cards turned upside down to show only the color in front of them Then, each player turns over the opponent’s card, saying the currency symbol of the card in turn. If the currency symbol disclosed matches that of the card turned around, the card can be captured. When the white cards are all used up, the blue cards are used then. The cards are turned around as the currency symbol is shouted. This time, two cards must be turned around, with the currency symbol shouted two times. The cards can be captured only when both currency symbols are correct. Lastly, the red cards can be captured when three currency symbols are matched. As the game is played in three rounds, a student who wins two rounds wins the game. As the game is played, students spontaneously learn that it is more difficult to guess correctly three times than once, which indicates that the consensus mechanism of the blockchain shows that the more nodes, the more difficult it is to record them in a ledger.

Secondly, the purpose of the public blockchain learning game is to acquire as many coins as possible within a specified time period. To play this game, four transaction ledgers, 200 coins, and one die are needed. The transaction ledgers are used as the reader board of the game where the names of game players and coins acquired or lost per game round. This game requires four party members. Each party member chooses a color out of four different colors. When the color is chosen, all party members put their markers on the marker board of their selected color. Then, all students are given 50 coins each. Then, the game is all set to be started. Then, the die is thrown in turn by all students. Each student can move their marker across the number of cells that match the number shown by the die when thrown. When the die shows three, a marker is moved three cells ahead. If the color of the destination cell matches the color selected by a player, he/she can throw the die once more, trading coins by the double. If the die shows an odd number when thrown, coins as many as the odd number must be paid to the owner of the color of the destination cell. If the die shows five, a marker is moved five cells forward, and if the destination cell is of green color (and the color of the student who threw the die is not green), five coins are paid to the party member who chose green. If the trading volume has increased by the double, 10 coins must be paid. If the number of the die is even, coins as many as the number of the die are taken from the party member that chose the color of the applicable cell. If the number of the die is four, a marker is moved four cells forward, and if the color of the destination cell is yellow (and the color of the student who threw the die is not yellow), four coins are taken from the party member who chose yellow. When the trading volume has increased by the double, eight coins are taken in the same manner as above. Whenever a transaction is made, all party members record them in their own transaction ledgers. The player who has won the most coins in a given time period wins the game. As the game is played, students will realize that the game is longer and more inconvenient to play since they have to update their ledgers each time. However, they will also realize that it is difficult to forge transactions, as they are required to document transaction details each time. This mechanism is connected with the concept that a public blockchain is open to everyone and its advantage is that it can ensure security and emphasize transparency. Furthermore, it relates to the weakness of public blockchain that it is slow, as consensus must be reached by many players and the ledgers synchronized continuously.

Lastly, the private blockchain learning game is basically similar to the public blockchain learning game, with slightly different rules adopted. Game materials to be prepared are the same as those required for the public blockchain learning game. In this game, only one student per game party is designated to document transactions. The student designated so selects his own party members. Once the game parties are all set, the game is started. When the die is thrown and a transaction occurs, the student documenting transactions records all transaction details in the transaction ledger. All the other players document their own transaction details in the ledger. Lastly, the student responsible for updating the transaction ledger checks the ledger and announces the winner. The private blockchain permits only authorized persons to join the blockchain network. This feature of the private blockchain is implemented by the student designed to document transactions and authorized to select party members. This game is expected to be finished earlier than the public blockchain learning game, as one person is designated per party to document the transaction ledger. The player authorized so is to play the role of central authority by metaphor. In addition, teachers may intervene to make sure that students can learn that they can forge transaction details with relative ease, as only a few authorities are allowed us to administer transactions.

3.4. Instruments Used

For research instruments, a total of three tools were adopted, including an education satisfaction assessment tool, a digital literacy measuring tool, and a tool that can measure both literacy and numeracy. First of all, as the education satisfaction assessment tool, the elementary student’s software education satisfaction assessment tool developed by Lee, Y. et al. was adopted to the needs of the blockchain education herein [34]. The tool covers four different categories: purpose and contents of education, learning game, education environment, and career planning assistance. The Likert scale was set to 5-point. The KMO value of the tool was found to be 0.899, with Bartlett’s test result p = 0.000 and Cronbach’s α = 0.898. Thus, the validity and reliability of the tool were verified.

Secondly, the digital literacy measuring tool was developed in reference to the framework of the digital literacy measuring tool designated by UNESCO, with questionnaires designed to be comprehensible by elementary students [29]. It is a 5-point Likert scale and the tool covers seven different areas, including the fundamentals of hardware and software, information and data literacy, communication and collaboration, digital contents creation, safety, problem solving, and career-related competencies. The area of career-related competencies covers capabilities and competencies for operating hardware or software, allowing for flexible modification, depending on the competencies of jobs using digital technologies. Thus, that area was changed to include questions on the understanding of blockchain technology in this research. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value of the tool was 0.874, with Bartlett’s test result p = 0.000, which vouches for strong validity. Furthermore, its reliability was verified with Cronbach’s α = 0.816.

Thirdly, the tool that could measure both literacy and numeracy was developed in reference to the PIAAC Assessment. As the PIAAC Assessment was designed to target adults, its complexity was lowered to better suit the needs of elementary students. The tool covers two areas: literacy and numeracy, with a total score of 100 points, with 50 points for each area. In terms of literacy, the tool can measure basic reading skills and linguistic skills, whereas in the numeracy area, basic numeracy and numeracy are measured. The KMO value of the tool was 0.798, with Bartlett’s test result p = 0.001 and Cronbach’s α = 0.914, which proves the validity and reliability of the tool.

3.5. Analysis Method

For the research methods, instruments were first developed to analyze the effects of the blockchain-themed program developed herein. The research findings were gathered and analyzed by IBM SPSS 24.0 program. The research tools were tested on validity and reliability. For the validity test, KMO of technical statistics and Bartlett’s test were conducted as a part of exploratory element analysis. In this research, the validity determination criteria were set to KMO values of 0.6 or higher as generally used in social science studies and Bartlett’s test outcome p of the significance level of less than 0.05 [35]. In addition, Cronbach’s α was obtained to determine the reliability of the tool. Cronbach’s α value of 0.6 generally used as a reliability benchmark in social science studies was selected as the reliability criterion for the questionnaire [36].

To determine whether the blockchain modules proposed herein can contribute to the fulfillment of Goal 4.1, a satisfaction level survey was conducted after education, and correlations of satisfaction level with participation in education were identified through technical statistics analysis and Pearson correlations analysis with sub-areas. Furthermore, in connection with the fulfillment of Goals 4.4 and 4.6, in the annual education programs, pre-and post-digital literacy, literacy, and numeracy scores of the participating students were analyzed via paired samples t-test.

4. Result

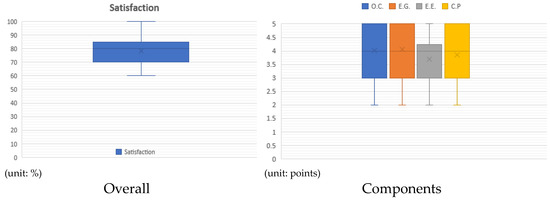

4.1. Analysis of Satisfaction Survey Findings with Blockchain Education

In the survey of satisfaction with the blockchain-centered education proposed herein, the overall satisfaction level was found to be 3.91 out of 5 points. Specifically, in sub-areas covering the purpose and contents of education, learning game, education environment, and career planning assistance, the satisfaction level with the learning game was the highest at 4.07 points, with the satisfaction with the career planning assistance the lowest at 3.85 points. Table 3 shows the satisfaction findings with the blockchain education, and Figure 4 visualizes the data for the entire areas and each sub-area.

Table 3.

Satisfaction analysis findings with blockchain education. (N = 684).

Figure 4.

Blockchain education satisfaction findings.

The Pearson correlations across sub-elements of the satisfaction with blockchain education were found between O.C. and E.G. and O.C. and C.P. The entire satisfaction score had static correlations with all sub-elements (Table 4).

Table 4.

Pearson correlations across sub-elements of satisfaction level with blockchain education.

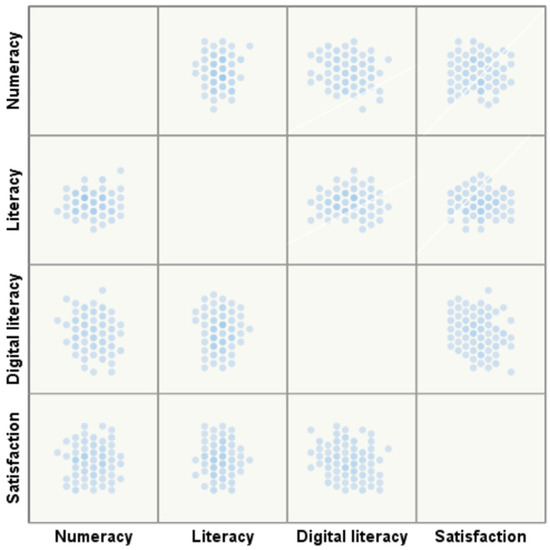

In the analysis of correlations between satisfaction with education and study variables of the elementary students who participated in the blockchain education program, a significant negative correlation with the post-survey finding of digital literacy was found (Figure 5). The Pearson correlation between satisfaction with education and digital literacy was −0.219 with a significance level at p = 0.000.

Figure 5.

Scatter plot of correlations between post-survey findings and satisfaction level.

4.2. Digital Literacy Improvement by Blockchain Education

The blockchain-themed program developed herein was used on 704 elementary students in Korea from 2019 to 2021. A paired-samples t-test was conducted to identify corresponding improvements in digital literacy, literacy, and numeracy. The education program was used on different research subjects each year, so all participants were first exposed to the program regardless of the year. Therefore, variation in competencies across different years was meaningless. Hence, the study findings of all research subjects of the three years were aggregated and analyzed.

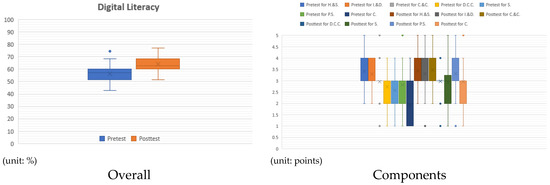

Firstly, in terms of digital literacy, statistically significant findings were gathered in five areas out of seven, including communication and collaboration, digital content creation, safety, problem solving, and career-related competences. In other areas including basics of hardware and software and information and data literacy, average test scores were somewhat improved but not significantly after the education. Digital literacy was improved from the pre-education average of 2.81 to 3.20 points after the education. Table 5 shows the paired samples t-test outcomes of digital literacy before and after the education program. Figure 6 visualizes in box plots the differences between the pre-test average and the post-test average per area.

Table 5.

Paired t-test results of digital literacy. (N = 684).

Figure 6.

Difference between pre-test average and post-test average of digital literacy.

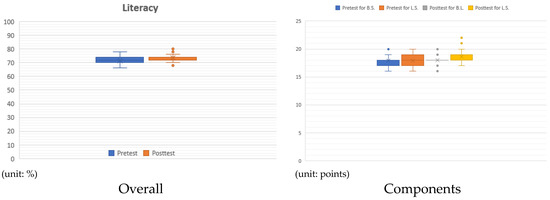

4.3. Improvement of Literacy and Numeracy by Blockchain Education

Improvement of pre-and post-education literacy as well as significance level need to be examined herein. Literacy is broken down into two areas: basic literacy and linguistic skill. The area that was identified as statistically significant before and after the education was linguistic skill. Literacy including the two areas was improved from 17.88 points before the education to 18.33 points after the education. Table 6 shows the paired t-test findings of literacy before and after the education. Figure 7 visualizes in box plots the differences between the pre-test average and the post-test average per area.

Table 6.

Paired t-test results of literacy. (N = 684).

Figure 7.

Difference between pre-test average and post-test average of literacy.

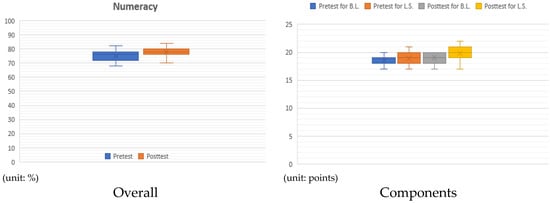

Next comes the analysis of differences in numeracy before and after the education. Numeracy is broken down to basic numeracy and numeracy and both areas showed statistically significant findings. Speaking of overall numeracy encompassing the two areas, the pre-education score of 18.74 was improved to 19.43 points on average. Table 7 shows the paired t-test findings of numeracy before and after the education. Figure 8 visualizes in box plots the differences between the pre-test average and the post-test average per area.

Table 7.

Paired t-test results of numeracy. (N = 684).

Figure 8.

Difference between pre-test average and post-test average of numeracy.

5. Discussion

Embarking on this research, we attempted to quantitatively analyze whether the blockchain education program designed by us could be an ESD enabler for SDG Goal 4. Accordingly, we defined three specific search topics in a bid to identify the contribution of the blockchain education proposed herein to Goals 4.1, 4.4, and 4.6.

Firstly, Goal 4.1 is about ensuring equitable-quality, free elementary and middle school education for all male and female children so that they can demonstrate appropriate and effective learning performance. The blockchain education program proposed and designed herein was launched in public schools so that the students could access the education program free of charge. Furthermore, given the high satisfaction level among the students with the education program (M = 3.91 points), it was noted that the students were satisfied despite the program introducing an unfamiliar concept. Hence, the education program is deemed to have contributed to the fulfillment of Goal 4.1 In addition, the contents of the blockchain education program had static correlations with the satisfaction of learners with the education game and career planning, and it was indicated that they could be satisfied with participation in the program even if they were still in need of digital literacy. This program will be further refined and adapted before being released free of charge to all schools and institutions for free use. Furthermore, training programs for schoolteachers will be launched to refine their technological competence for blockchain technology.

Secondly, Goal 4.4 is about increasing the number of people equipped with appropriate skills including professional job skills required for job placement, decent jobs, and entrepreneurship. Global indicators for the fulfillment of Goal 4.4 include digital literacy. As digital technologies are connected with all industries at the onset of the fourth Industrial Revolution, understanding digital technologies and devices is getting increasingly significant for one’s life [37]. In particular, for elementary students, digital literacy is expected to be named as one of the essential competencies for remaining competitive in the future [38]. After being exposed to the blockchain-centered educational program proposed herein, the digital literacy of the students was improved by 0.39 points on average from the pre-education level of 2.81 points on average to 3.20 points. Furthermore, five out of seven sub-areas featured statistically significant findings. The two areas where statistical significance was not found were the basic knowledge of hardware and software and the data literacy required for assessing data and sharing content with digital technologies. They are deemed to be attributable to the fact that the blockchain education herein is a far cry from basic computer knowledge and data management required for simply turning on/off computers. Meanwhile, what is noteworthy in the digital literacy analysis findings is that the difference in the pre-and post-education averages for the career-related competencies was most drastically improved. This implies that the students who had little knowledge about blockchain became aware of the importance and future potential of blockchain technology, which indicates that the education program is effective for future career planning. Blockchain technology is one of the promising technologies that can guarantee placements in decent jobs. Through gaming activities that implied concepts of informatics derived from professional fields, young learners can experience career-related works in information technology [27]. Accordingly, it is indicated that the education program herein had a significant impact on the fulfillment of Goal 4.4.

Goal 4.6, which is the last research topic, is about the accomplishment of literacy and numeracy. To fulfill Goal 4.6, it is important to ensure that students are better skilled in linguistic and numeric competencies. When the education program was conducted on students, their linguistic skill, a sub-area of literacy, was improved with statistical significance. However, basic literacy did not show a statistically significant difference, as the blockchain education program did not have a significant bearing on the improvement of reading skills involving a selection of appropriate words for a given sentence or correct sentences. Meanwhile, in terms of numeracy, the education program improved both basic numeracy and numeracy skills with statistical significance. Such activities as trading cryptocurrencies or documenting transaction ledgers in learning games are deemed to have been conducive to improving the understanding of and prowess with numbers. These findings demonstrate that the education program herein could contribute to improving the linguistic and numeracy skills of students. Therefore, the education program is deemed to have been conducive to the fulfillment of Goal 4.6.

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted that gamification receives the spotlight due to its value in increasing prompt learner responses, learning immersion, participation, motivations, and immediate interactions in an online learning environment [23]. Though this study adds that the gamification approach is helpful to teach and learn core principles of blockchain technology, it has not demonstrated how the gamification approach affects elementary school students in the online context. Thus, it is imperative to develop a further refined program on blockchain for the online version to widely spread for vulnerable learners.

6. Conclusions

Blockchain is touted as underpinning the fourth Industrial Revolution characterized by hyper-connectivity and super-intelligence [39]. The World Economic Forum forecasted that 10% or more of the global GDP would be associated with blockchain technologies by 2025 [40]. In particular, given its features that can decentralize data controlled by a centralized system in the pact and allow individuals to transact among themselves, blockchain technology is being welcomed as an innovative enabler for finance, manufacturing, public service, culture, and distribution sectors. Hence, blockchain technology, to be ever significant in the future, is regarded as an essential technology with which children, our future leaders, must be familiar.

This article focused on Goal 4 out of the SDGs and proposed an education program utilizing blockchain as game content and enabling students to readily access and understand blockchain technology by playing games. In so doing, the students were encouraged to improve their digital literacy, literacy, and numeracy to contribute to quantitative fulfillment of Goal 4 and enable ESD, facilitating the fulfillment of the SDGs in the end.

Yet, the education program herein, which specifies elementary students as a primary target, is not suitable for middle or high school students or adults. Furthermore, as the education program is not sub-divided per skill level of learners, it may not be applicable to learners who already understand what blockchain is. In addition, although SDG4 has a total of seven targets, we focused on potential contributions to the fulfillment of Goals 4.1, 4.4, and 4.6. Concerning the limitation of the research, we will continue to refine and develop the education program to meet the varying needs of different skill levels of learners. In addition, we will conduct studies and analyses subsequently to provide quantitative implications for the other four targets.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, validation, formal analysis and writing—original draft preparation, E.C.; writing, review and editing, Y.C.; supervision and project administration, N.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2019S1A5C2A04083374), and this work was supported by the Korea Foundation for the Advancement of Science and Creativity (KOFAC) grant funded by the Korea government (MOE).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to a Confidentiality Agreement.

Conflicts of Interest

E.C., Y.C. and N.P. declare no conflict of interest.

References

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, A/RES/70/1. Available online: https://undocs.org/a/res/70/1 (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Korea. Unpacking Sustainable Development Goal 4-Education 2030, 2nd ed.; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Korea: Seoul, Korea, 2018; pp. 1–75. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Institute for Statistics. Quick Guide to Education Indicators for SDG 4; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Institute for Statistics: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2018; pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Korean Educational Development Institute. Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goal 4 in Korea; Korean Educational Development Institute: Chungcheong, Korea, 2019; pp. 5–59. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, J.M. Current Status of Domestic and Foreign Implementation and Priority Tasks. SDG4-Education 2030 Forum: Monitoring and Domestic Implementation, Seoul, Korea, 20 September 2018. Available online: https://www.unesco.or.kr/assets/data/report/rhXV4vJzkmqzcIJcdYa8fi4Mu495yc_1552977857_2.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Lee, S. Qualitative case study research about school droupouts’ returning experience to the specialized high school in alternative education: The students out of schools, open the doors of another school. J. Youth Welf. 2015, 17, 333–356. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education Republic of Korea; Korean Educational Development Institute. 2019 Education Statistics Analysis Data Collection–Statistics on K-12; Korean Educational Development Institute: Chungcheong, Korea, 2019; pp. 5–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education Republic of Korea; Korean Educational Development Institute. Statistical Yearbook of Education; Korean Educational Development Institute: Chungcheong, Korea, 2020; pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.H.; Kim, S.C. Examination of current issues and the suggestion of reform based on public character in higher education. J. Educ. Cult. 2020, 26, 37–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. IEA International Comparative Study: ICILS 2013 Results Analysis. In KICE Research Report 2014; Korea Institute of Curriculum & Evaluation (KICE): Cheongju, Korea, 2014; pp. 87–91. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Lifelong Education. Statistical Information Report of Adult Literacy Proficiency Survey. Available online: http://125.61.91.238:8080/SynapDocViewServer/viewer/doc.html?key=0000000077af38a2017ebebd71d36f1d&convType=img&convLocale=ko_KR&contextPath=/SynapDocViewServer (accessed on 25 January 2019).

- Ministry of Education Republic of Korea. 2015 Revised National Curriculum; Ministry of Education Republic of Korea: Seoul, Korea, 2015; pp. 48–87.

- Yaga, D.; Mell, P.; Roby, N.; Scarfone, K. Blockchain Technology Overview; National Institute of Standards and Technology Internal Report 8202. Available online: https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1906/1906.11078.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Bhardwaj, S.; Kaushik, M. Blockchain-technology to drive the future. Smart Comput. Inform. 2018, 78, 263–271. [Google Scholar]

- Aysan, A.; Bergigui, F.; Disli, M. Blockchain-based solutions in achieving SDGs after COVID-19. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkanović, M.; Hölbl, M.; Košič, K.; Heričko, M.; Kamišalić, A. EduCTX: A blockchain-based higher education credit platform. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 5112–5127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, X. Application of blockchain technology in online education. Int. J. Emerg. 2018, 13, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.T. Proposal for Direction of blockchain education on gamification. J. Korea Soc. Comput. Game 2019, 32, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Park, N. Blockchain technology core principle education of elementary school student using gamification. J. Korean Assoc. Inf. Educ. 2019, 23, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Introduction to Gamification; Hongreung Puplishing Company: Seoul, Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, J.; Koh, H. A study on the development of a digital art museum education program through the use of gamification. Art Educ. Rev. 2020, 74, 229–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Kim, S.K.; Rachmatullah, A.; Ha, M.S.; Yoon, H.S. The effects of science class applied gamification contents. Sch. Sci. J. 2018, 12, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.-Y.; Lee, M.-H. Analysis of learning immersion and class participation in gamification-based classes. J. Educ. Innov. RSRCH 2021, 31, 163–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibanez, M.B.; Di-Serio, A.; Delgago-Kloos, C. Gamification for engaging computer science students in learning activities: A case study. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2014, 7, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Ahmad, F.H.; Malik, M.M. Use of digital game based learning and gamification in secondary school science: The effect on student engagement, learning and gender difference. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2017, 22, 2767–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, D.; Park, N. Development of a STEAM program to learn the principles of quantum mechanics by applying the gamification mechanism. J. Korean Assoc. Inf. Educ. 2016, 20, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Park, N. Teaching book and tools of elementary network security learning using gamification mechanisms. J. Korea Inst. Inf. Secur. Cryptol. 2016, 26, 787–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Global Education Monitoring Report 2020: Inclusion and Education: All Means All; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2020; pp. 247–254. [Google Scholar]

- Law, N.; Woo, D.; Torre, J.; Wong, G. A Global Framework of Reference on Digital Literacy Skills for Indicator 4.4.2; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Institute for Statistics: Quebec, QC, Canada, 2018; pp. 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- PIAAC Literacy Expert Group. PIAAC Literacy: A Conceptual Framework; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development: Paris, France, 2009; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Murry, T.S. DataAngel Policy Research. In Functional Literacy and Numeracy: Definitions and Options for Measurement of SDG 4.6; DataAngel Policy Research: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018; pp. 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Research Institute for Vocational Education & Training. PIAAC. Available online: https://www.krivet.re.kr/ku/ca/kuADALs.jsp (accessed on 3 September 2018).

- Livingston, S.A.; Stoll, C.S. Simulation Games, An Introduction for the Social Studies Teacher; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, S.; Hong, J.; Koo, D.; Park, J. Development of measuring tools for analysis of elementary and secondary school students’ software education satisfaction. J. Korean Assoc. Inf. Educ. 2019, 23, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F.; Rice, J. Little Jiffy, Mark Iv. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1974, 34, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.R. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Park, N. Blockchain-based data-perserving AI learning environment model for AI cybersecurity systems in IoT service environments. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimbeni, F.; Vosloo, S. Digital Literacy for Children: Exploring Definitions and Frameworks; United Nations Children’s Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kuleto, V.; Bucea-Manea-Țoniş, R.; Bucea-Manea-Țoniş, R.; Ilić, M.P.; Martins, O.M.D.; Ranković, M.; Coelho, A.S. The potential of blockchain technology in higher education as perceived by students in Serbia, Romania, and Portugal. Sustainability 2022, 14, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. Building Block(chain)s for a Better Planet; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).