Abstract

In the context of the Sustainable Development Goals interest and concerns about the environmental impact of major sporting events have become increasingly widespread, voiced not only by organizers, but also spectators and residents of affected areas, as well politicians and institutional representatives of the host territories. There are multiple studies of the economic, social, and legal impacts of major sport events. Although several studies have pointed to a range of environmental impacts, there is no clear consensus on the effects that a major event can have on the natural environment. Thus, the aim of this article is to carry out a systematic review of the state of the art. Following the steps proposed by the PRISMA protocol, a selection of scientific articles from between 2000 and 2021 was made. The overall analysis shows that the negatives outweigh the positives, as only 32.91% of the effects described in the articles are deemed to be positive, with 62.03% deemed to be negative, and finally, 5.06% found to be inconclusive. With varying degrees of success, organizers and promoters of major events are already attempting measures to reduce negative impacts and enhance positive ones.

1. Introduction

It is evident that all human activities have consequences for the environment that surrounds us [1]. Historically, this human impact came about as a consequence of cultural evolution, as land and other forms of natural capital have been appropriated to enhance and support the human habitat [2]. The effects that human beings have on the ecosystem, whether positive or negative, take time to manifest themselves, which makes it difficult to respond effectively if we are not able to anticipate and foresee them [3].

Major sporting events, as a large-scale human activity, inevitably have an impact on the environment [4,5,6]. Given that land and nature are finite resources, measures have to be put in place to minimize the negative environmental impact of major sporting events [1,7,8] and to reinforce the effects viewed as positive for the host territory [9]. Since 2000, there has been exponential growth in the number of major events, and the continued boom in the mega-event industry, as well as the recent expansion into emerging markets and non-democratic states, has left it facing an array of new and often poorly understood dangers. Over the next decade, the Olympics and the Football World Cup will be held in a number of emerging states against a backdrop of ever-changing global risks [10].

Since the 1990s, there has been an exponential increase in the research on major events [11]. Studies have often examined the short-term impact of these events and the longer-term legacy they leave behind. For example, a number of researchers [12,13,14] have published guides and articles in reference to events’ environmental impact and legacy.

There is some disagreement about how best to define the word sustainability, but most interpretations of the term involve a focus on human needs and values and an emphasis on the future [15]. The concept of sustainability has its origins in German forestry literature as the principle of “Nachaltigkeitsprinzezip” [16,17]. Sustainability is not necessarily a fixed destination, but rather a set of characteristics intended to describe the functioning of some future system [18]. This perspective frames the concept in a more realistic and actionable fashion, in that it allows for a view of sustainability as a “prediction” of what will endure in a manner sensitive to both time and spatial variability [19].

Sustainability, as a theory of human development, has a high degree of linguistic ambiguity, which makes it difficult both to formulate the method and to clarify the approach needed [20]. Sustainability theory seeks to explain the reciprocal relationship between degraded environmental processes resulting from human activities and the vulnerability of those activities to a degraded environment [2].

The meanings of the concept of sustainability have evolved, and individual professions have attempted to develop definitions that make sense in the context of their respective areas of expertise [21]. It is worth noting that, according to the three-pillar conceptual model of sustainability, the economic and social parts of systems are constrained by the environment, which imposes limits on the degree of intensity with which these systems can function [2]. The model illustrates the codependent relationship the environment has with the social and economic spheres and the role the it plays in underpinning human subsystems.

The triple bottom line (TBL) theory highlights the non-market and non-financial areas of corporate performance and responsibility, specifically considering economic, environmental, and social impact [22]. The TBL is used as a framework to report on company performance and measure it against economic, social and environmental parameters [23]. One widely adopted definition of sustainable development comes from the World Commission on Environment and Development [15], which defines the term as development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. Environmental sustainability is essentially a natural science construct that seeks to apply biophysical principles to define appropriate conditions of balance, resilience, and interconnectedness between human society and the supporting ecosystem [21]. Elsewhere, authors have emphasized the longstanding, intimate connections between the environment and development. Countries consider economic development a top priority, and developing countries have sometimes believed that environmental considerations could limit or impede their development, even desiring pollution as a symbol of industrialization [24].

A range of models have been used to assess sustainability. Firstly, there is the three-pillar model, which includes the environmental, social and economic dimensions [23,25,26]. Secondly, the four-pillar model encompasses institutional, social, economic and environmental dimensions [27]. There is also the model of cosmic interdependence [28] and, finally, the model of the circles of sustainability [29].

There are also a number of methods and measurement models intended to assess environmental sustainability. One such approach is a flexible tool to assess buildings hosting major sport events [30]. Another one is a case-study methodology [31] that uses the life cycle assessment method to evaluate major sporting events. The ecological footprint (EF) method has also been used in some studies [32], as have environmental input–output analysis (ENVIO) and many others [4]. The qualitative and quantitative information collected in these studies is analyzed and detailed in the subsequent tables. It has been considered that the type and magnitude of the impact of sport events differs according to the size of the event. The literature has proven that the impacts and legacy of events of different sizes can vary, and that they should be assessed with this in mind [33,34,35]. A classification system for these events is used in this systematic review to obtain more accurate information.

Sporting events can be classified according to their size, visitor appeal (based on the number of tickets sold), audience reach (based on the cost of broadcasting rights), total cost, and transformational impact (capital investment) [35]. An index has been created by awarding a range of values for each variable, according to which events scoring between 1 and 6 points will be considered major-events, while those that score between 7 and 10 will be called mega-events, and those that score between 11 and 12 will be labelled giga-events, as can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sporting events scoring matrix second measurement.

As the negative environmental impacts of major sporting events has come to light, research and work has been carried out in various contexts in attempts to reverse these harmful environmental impacts and reinforce the beneficial ones.

The increasing concern about negative impacts has put pressure on the major organizers of events to move towards a more sustainable way of doing things.

In light of the large number of articles published on the environmental impact of major events in recent years and the wide range of topics they cover, it was considered useful and necessary to carry out a systematic review of the literature on the environmental impacts of major sporting events in order to ascertain the state of the art.

2. Materials and Methods

To analyze the environmental impacts generated by major sporting events and to be able to categorize these events, a qualitative systematic review was carried out.

2.1. Literature Identification

A systematic literature search was carried out using the following databases: Ebscohost, eBook Collection (EBSCOhost), E-Journals, GreenFILE, Sales & Marketing Source, SportDiscus. Web of Science, Web of Science Core Collection, CABI, Current Contents Connect, BIOSISCitation Index, BIOSIS Previews, MEDLINE, Zoological Record, KCI-Korean Journal Database, Derwent Innovations Index, SciELO Citation Index, Russian Science Citation Index and Scopus. The search was limited to scientific articles published between 2000 and January 2021. It was based on the PRISMA methodology [36] of identification, selection, choice and inclusion. We decided on the period from 2000 to 2021, since no systematic review or meta-analysis covering this time frame was found. There is an increasing need for transfer of knowledge from academia to society from the point of view of environmental sustainability, especially when it comes to major sporting events.

The search string is shown in Table 2, and is made up of four parts: (1) sport, as the focus of the research, together with (2) events, which places us in a specific space and time when a planned event takes place; (3) impact, effect, influence, outcome, result or consequence, referring to all the effects of the sporting event; (4) major, mega, large, big or giga or Olympic, to focus on the object of study; (5) and, finally, to focus on the type of impact on which the study focuses, environment or ecological.

Table 2.

Keywords for the creation of the English search string.

The search string is detailed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Search String.

2.2. Selection and Data Extraction

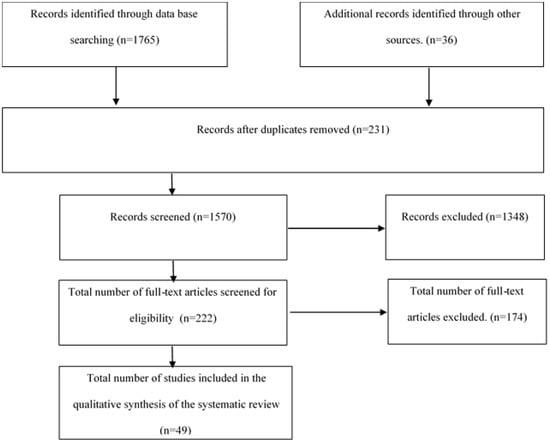

Combining the results from all databases, a total of 1801 records were identified. Once the duplicates had been removed, the total number of records was reduced to 1570, which were then screened for inclusion or exclusion. To reduce bias, a double check by title and abstract was performed. A total of 222 articles were accepted to be filtered through full-text reading. Finally, after the elimination of articles that did not meet the established criteria as they did not refer to major sporting events or did not address their environmental impact, 49 articles were included in the systematic review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Selection and data extraction.

3. Results

Overall, 49 studies were selected and analyzed. All the studies were in English. The studies employed a number of different methods of analysis, as shown in Table 4. Cross-sectional studies represent the majority, with a total of 28 studies or 57.14% of the total. The second most common were longitudinal studies, of which there were 13, representing 26.53%. In third position, there were five theoretical studies and/or policy statements, representing 10.20% of the total, and, finally, we found three non-systematic literature reviews, 6.12% of the total, as can be seen in Table 4.

Table 4.

Types of methods used by the studies.

3.1. Event Identification

The 49 selected articles study a total of 50 events: 21 of the papers (42.85%) refer to the Olympic Games, 9 (18.36%) to the FIFA Football World Cup, 2 (4.08%) to the 2003–2004 FA Cup Final, 2 (4.08%) to the 2003 World Ski Championships in St. Moritz, 9 (2.04%) to a single event other than the above, and the remaining 7 (14.28%) make a general analysis of major events without referring to any specific event As mentioned above, these results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Number of studies by type of event.

The events included in the systematic review have been classified according to their size, in accordance with the system defined by Müller, as detailed in Table 6. Data from previous studies on events have been used to develop this classification [35,79,80]. Thus, we have a total of five giga-events (21.74%), nine mega-events (39.14%) and nine major events (39.13%).

Table 6.

Dimensions of the events.

3.2. Identification of Impacts Associated with the Events

Overall, the results show a greater prevalence of detrimental impacts than of beneficial ones. As can be seen in Table 7, a total of 26 impacts were considered positive, representing 32.91% of the total. A total of 49 negative impacts were identified, or 62.03% of the total. Lastly, there are four inconclusive impacts, which have no perceptible effect on the environment, accounting for a total of 5.06%. The table shows the number of studies (n) that refer to each event.

Table 7.

Type of impact per event according to its classification and type (events n = 52).

Table 7 shows the positive impacts of the analyzed events. The studies included in the systematic review highlight a total of 12 positive impacts. In the case of events in which two or more studies reflect the same impact, we counted each one as a separate impact. For example, in the case of the 2008 Beijing Olympics, where three of the six articles agreed on the decrease in air pollution, we counted this three times.

Although a similar number of studies analyzed events of each of the three dimensions (19 looked at giga-events, 15 at mega-events and 18 at major-events), the giga-events clearly outperform the other categories in terms of the positive impacts identified in the literature, as can be seen in Table S1. The most frequent positive impacts are the decrease in air pollution, the improvement of the host city’s livability and improvements in the ecological civilization index. Table S1 is available in the Supplementary Materials.

The negative or adverse impacts are shown in Table S2. In this case, the impacts of mega-events were greater in number than those of major events. The former had 18 identified impacts, while the latter had 14, and giga-events had only 13 identified impacts. The most frequent negative impacts are the increase in air pollution, the poor formulation of the environmental sustainability program, and the omission of environmental responsibility on the part of the organizers and promoters.

Only three events were found not to have generated any definite impact (Table S3), or, in other words, had an inconclusive impact. Firstly, this is the case of the future Football World Cup to be held in Qatar in 2022, which aims to have neutral emissions. Secondly, it was the case of the 2003 St. Moritz World Ski Championships, about which the two articles underlined the importance of the planning phase to achieve the environmental sustainability objectives. Lastly, no impacts are defined in the article covering the England Football Cup Final of the 2003–2004 season, which also reinforces the importance of the planning phase.

3.3. Impacts Associated with Events According to Their Dimension

The giga-events were found to have 15 (53.57%) positive impacts and 13 (46.43%) negative impacts, a total of 28. The mega-events had 5 (20.83%) positive impacts, 1 (4.17%) inconclusive impact and 18 (75%) negative impacts, a total of 24 impacts. The major events had a total of 3 (15%) positive impacts, 3 (15%) inconclusive impacts and 14 (70%) negative impacts, a total of 20 impacts. Finally, there were impacts that were not associated with any specific event, specifically, 3 (42.86%) positive impacts and 4 (57.14%) negative impacts, a total of 7.

3.3.1. Positive Impacts

In the case of the 1992 Barcelona Summer Olympic Games, environmental education initiatives were identified. These programs were intended to improve society’s knowledge of the importance of the environment and to raise awareness of the measures taken in connection with the Games. For example, there were some restorative initiatives, such as the planting of trees to offset carbon emissions during the preparation and execution of the games [47].

It is clear that some events have helped to improve the infrastructure of the cities and territories that host them. In the case of the Athens Summer Olympic Games in 2004, the city’s metro system grew by a factor of 1.74 [6]. The improvement of motorways is also a clear example, as during the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens, motorways were upgraded [6]. A report on the World Games held in Kaohsiung in 2009 shows that residents, especially women, value major events positively as long as they are linked to improvement in the city’s landscape and facilities [51]. Some authors also challenge governments to improve the quality of cities so that residents will be more willing to host sporting events [51,56].

The reduction of air pollution is one of the impacts that appears most frequently in studies on giga-events. In the case of the Athens Summer Olympics in 2004, the Beijing Summer Olympics in 2008, and the Rio Summer Olympics in 2016, all studies show that emissions of different particulate pollutants such as ozone (O3), carbon dioxide (CO₂), carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and sulfur dioxide were reduced (SO2) [6,9,60,64,67,71]. However, it should be noted that in the case of the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics, pollution levels returned to normal levels after the Games were over [9,67,71].

A couple of papers state that the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics increased the score on the ecological civilization index, improving the urban thermal environment thanks to the increase in the areas with permeable surfaces, which made the city more livable [63,66]. Other studies show the effect of major sporting events in Russia, focusing on the cases of the 2013 Universiade held in Kazan, the 2014 Winter Olympics held in Sochi and the 2018 Football World Cup. These studies found that after the events, citizens became more environmentally friendly and lived a greener lifestyle, changes that could be linked to the increased accessibility of green infrastructure, such as the widespread implementation of recycling bins, the creation of green ways for cyclists, and the environmental certification of products and services [39].

One of the most important positive environmental and economic effects for the host of the Olympic Games is the development and improvement of the transport industry [45].

In preparation for the London 2012 Summer Olympics, nearly 2 million tons of contaminated soil was cleaned up for reuse in the Olympic Park [45].

Growing concern for the environment is driving cities to apply environmental criteria in the design, planning and implementation phases, leading to an increase in sustainable construction, the use of recycled materials, the use of renewable energy, and the protection of ecologically vulnerable areas and endangered species [38]. The plan for the 2012 London Summer Olympics called for 42% recycled material to be used, and thousands of plants, trees and bulbs to be planted [45].

Parallel to some events, a series of green initiatives are generated. This happened in London 2012 and the 2006 Football World Cup in Germany [37,45]. Over time, event promoters and organizers are increasingly incorporating green initiatives and sustainability principles into their plans [78].

Some events have been moved away from protected areas, thus favoring a better use of the heritage sites and avoiding some of the environmental impact of these events, as in the case of various Winter Olympic Games [6].

Visitors to the 2013 Africa World Cup of Nations did not believe that the event would increase pollution in the area, nor that the environment would degrade in the area where the event was held [52].

3.3.2. Negative Impacts

Other papers reviewed show residents’ perceptions of environmental impact, often finding that respondents tended to support green events, but not major events such as the Olympic Games [55].

Several studies point to the increase in air pollution linked to major sporting events, such as the 2006 Winter Olympics in Turin, the 2010 Commonwealth Games in Delhi, the English Football Cup Final in 2003–2004, the 2004 Rally World Championships, the stages of the Tour de France that passed through the UK, the 2009 Australian Formula 1 Grand Prix and the Major League Baseball in the United States [4,40,46,50,53,61,62,69]. The 2009 Australian Formula 1 Grand Prix saw the surrounding ecosystem disrupted by increased pollution and other issues [46].

Residents’ perceptions of adverse environmental effects have also been closely observed [54], and it has been noted that residents aged between 33 and 55 associate major events with increased pollution and increased traffic congestion, specifically in a study of the 2012 London Summer Olympics. Residents’ perceptions of increased pollution and increased waste are also shared with other studies [51].

Visitors to the 2010 Football World Cup in South Africa recognized that the event had adverse environmental effects such as increased pollution, increased waste, high water consumption, noise pollution, destruction of natural habitats and loss of biodiversity [58]. Meanwhile, a study of the 2016 Hail International Rally shows that environmental damage is very important to the local population, and the researchers urge organizing committees to consider all possible procedures to reduce the adverse side effects on the environment [49].

The lack of communication from promoters and organizers to residents was evident in the London 2012 Summer Olympics [54].

Poor formulation of the sustainability program, omission of responsibility and minimization of adverse environmental effects caused by the event were common to the following events: (a) London 2012 Summer Olympics; (b) Rio 2016 Summer Olympics; (c) the 2012 edition of the European Football Championship; and (d) the 2010 World Cup in South Africa [1,5,41,43,48,68].

Especially noteworthy is the case of the 2014 World Cup held in Brazil, as the stadium was certified as carbon-neutral, yet the certificate was issued thanks to a program that envisaged planting 1.4 million trees in the area, to reverse the adverse effects of the construction. In the end, only 70,000 trees were planted, and the nursery was abandoned after achieving only 5% of the planting required to determine a positive impact. This program was clearly poorly formulated, and there was a clear omission of environmental responsibility and a failure to enforce the agreements that had been defined [5]. Other authors [76] have observed that major sporting events have adverse effects on biodiversity and natural resources. Indeed, environmental and climate safeguards were introduced into FIFA’s bidding procedure for the years 2018 and 2022. These requirements call for the hosts to adopt ambitious climate policies and regulations to reduce their carbon footprint, yet climate change does not appear to feature prominently in the substantive and material provisions included in the bid. In fact, it is not even a major part of their program.

Elsewhere, related authors have found no positive effects of the hosting of the mega-sport event on four quality of life domains of the residents themselves [68]. The individual perception of changes in quality of life varies, and does not necessarily correspond with what has been foreseen in the program.

Before the London Summer Olympics of 2012, it was been pointed out that 6.5 million people would attend the London 2012 Summer Olympics, which would generate more than 3300 tons of food packaging waste [45].

From an ideological point of view, and with reference to the 2016 Summer Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro, the academic consensus seems to be coalescing around the notion that large sporting events such as the Olympics are incongruent with sustainability [75].

Some events have led to environmental degradation and the destruction of protected areas, such as the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro [8,45,70]

Poor or nonexistent coordination has also been pointed out [44,68,77] in the cases of the 2010 World Cup held in South Africa and the 2014 World Cup held in Brazil.

Excessive use of energy and water, together with high waste generation, were pointed out in connection with the English Football Cup 2003–2004 season [50].

3.3.3. Inconclusive Impacts

The organizers of the Football World Cup to be held in Qatar in 2022 are planning to build the first zero-carbon stadium. Local organizers are applying green technologies and sustainable urban development concepts. They also underline that more needs to be done to reduce adverse environmental impacts [74].

In the case of the study of the 2003 Alpine World Ski Championships in St. Moritz, the importance of the planning phase to eliminate negative influences on the environment is emphasized, and the authors contend that some negative aspects, such as excessive traffic, could be eliminated at the planning stage [42,57]. However, the positive effects envisaged at the planning stage are often linked to the social and economic spheres, relegating environmental effects to the status of a secondary concern [57]. Nonetheless, as observed in connection with the 2003–2004 English Football Cup Final, events of this nature have potentially large impacts on the environment, and there is a need to give these concerns greater consideration in the planning of future events [53].

The environment has become a key factor in the hosting of the Olympic Games, and both residents and visitors often consider events’ environmental legacy to be the most important, as their quality of life depends on it. Major events can have a potential impact on local ecosystems, and these effects are difficult to assess quantitatively. Some authors also propose a method for feasibility analysis of sport events based on environmental estimation methods [72].

The quality of life of residents is affected by the legacy of major sporting events. In one study, residents said the environmental legacy was of the greatest importance. The environmental impact and legacy of an event is crucial for the residents [65].

In another study [73], major sporting events are said to demonstrate an improvement in the image of social civilization. The study proposes a quantitative evaluation model based on the quantitative recursive analysis of the ecological environment in sports events, starting from the air pollution index, vegetation cover rate and urban microclimate, as factors of environmental quality evaluation. Once this has been carried out, it suggests a series of actions hosts can take to establish an environmental protection strategy.

4. Discussion

This study focuses on the environmental sustainability of large sports events, examining whether the effects are positive, negative, or inconclusive. The articles have been grouped according to the dimension of the events they cover [35], as it was felt that this classification would be helpful in identifying studies looking at different kinds of events. However, other studies classify events according to other criteria, and this led to a potential bias in the results when comparing them with each other.

We have been able to observe that there is a parity between the positive and negative impacts identified in giga-events, while in the mega-events there are only five positives impacts and 18 negative impacts, and the mayor-events continue with the trend of the mega-events, in this case with three positive impacts identified against 14 negative impacts.

As sustainable development goals become enshrined in sport organizations and public sector bodies, harmful impacts will be reduced, and measures to increase beneficial impacts will be increased [40].

5. Conclusions

This systematic review provides an overview of the environmental impacts of the major events that have been studied. Obviously, the fact that these events have been studied does not imply that they are the only ones, nor that they are more important than others.

Of the total number of impacts studied in the review, 26 (32.91%) were positive impacts, 4 (5.06%) were inconclusive impacts (having no impact or legacy on the territory), and 49 (62.03%) were negative impacts. Even so, if we classify according to giga-event, mega-event, major event and studies not linked to any specific event, we find differences, a finding that reinforces the article’s approach of dividing events according to their dimension.

The fact that an event has a greater number of positive impacts does not imply that the total balance is positive; only on the basis of comprehensive studies on all environmental impacts can we come to a final verdict on the environmental impact of an event.

In light of the number of studies published, there is evidence of a growing concern and interest in environmental sustainability on the part of researchers investigating major events and their model of sustainability. From the analysis and review of the articles, we can affirm that progress is being made, since the organizers and promoters of major events have, with varying degrees of success, begun to incorporate more measures to reduce the negative impacts and enhance the positive ones. It is necessary to continue working and establishing measures and methods to reduce the adverse environmental effects of major sporting events and to enhance their positive effects.

Every stakeholder in the world of major sporting events has a key role to play, and should be responsible for ensuring that major events produce positive environmental impacts, including event promoters, host territories, politicians, residents, athletes, consumers... The importance of sustainability education at all levels and for all stakeholders has been demonstrated, as well as the guarantees that ensure compliance with established regulations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su142013581/s1, Table S1: Positive impacts by event according to their classification and type (events N = 52); Table S2: Negative impacts by event according to their classification and type (events N = 52); Table S3: Inconclusive impacts by event-by-event classification and type (events N = 52).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C.-E. and E.I.; methodology, S.C.-E., E.I. and J.S.-U.; software, S.C.-E., E.I. and J.S.-U.; validation, S.C.-E., E.I. and J.S.-U.; formal analysis, S.C.-E. and E.I.; investigation, S.C.-E., E.I., J.S.-U. and F.S.; resources, S.C.-E. and E.I.; data curation, S.C.-E., E.I., J.S.-U. and F.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C.-E.; writing—review and editing, S.C.-E., E.I., J.S.-U. and F.S.; visualization, S.C.-E.; supervision, S.C.-E. and E.I.; project administration, S.C.-E.; funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ross, W.J.; Leopkey, B. The Adoption and Evolution of Environmental Practices in the Olympic Games. Manag. Sport Leis. 2017, 22, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lein, J.K. Futures Research and Environmental Sustainability: Theory and Method; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-315-37113-9. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, C.; Alonso, S.; Benito, G.; Dachs, J.; Montes, C.; Buendía, M.; Rios, A.; Simó, R.; Valladares, F. Cambio Global. Impacto de la Actividad Humana Sobre el Sistema Tierra; Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas: Madrid, España, 2006; p. 170. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, A.; Munday, M.; Roberts, A. Environmental Consequences of Tourism Consumption at Major Events: An Analysis of the UK Stages of the 2007 Tour de France. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabb, L.A.H. Debating the Success of Carbon-Offsetting Projects at Sports Mega-Events. A Case from the 2014 FIFA World Cup. J. Sustain. For. 2018, 37, 178–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziralis, G.; Tolis, A.; Tatsiopoulos, I.; Aravossis, K. Sustainability and the Olympics: The Case of Athens 2004. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2008, 3, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappelet, J.-L. Olympic Environmental Concerns as a Legacy of the Winter Games. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2008, 25, 1884–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, C. Between Discourse and Reality: The Un-Sustainability of Mega-Event Planning. Sustainability 2013, 5, 3926–3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhong, C.; Yi, M. Did Olympic Games Improve Air Quality in Beijing? Based on the Synthetic Control Method. Environ. Econ. Policy Stud. 2016, 18, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frawley, S. (Ed.) Managing Sport Mega-Events; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-315-75764-3. [Google Scholar]

- López, J.S.M. Mega-eventos deportivos en América Latina: Implicaciones, características y tendencias. ¿Los gobiernos deben seguir apoyando económicamente su realización? Espac. Abierto Cuad. Venez. Sociol. 2016, 25, 31–50. [Google Scholar]

- Valle, P.L.; Rico, S.R.; Extremera, A.B.; Gallegos, A.G. Análisis de las medidas de impacto ambiental en los Raids de aventura en España. Interciencia 2012, 37, 729–735. [Google Scholar]

- Magaz-González, A.M.; Fanjul-Suárez, J.L. Organización de Eventos Deportivos Y Gestión de Proyectos: Factores, Fases Y Áreas. Rev. Int. Med. Cienc. Act. Física Deporte Int. J. Med. Sci. Phys. Act. Sport 2012, 12, 138–169. [Google Scholar]

- Sotiriadou, P.; Hill, B. Raising Environmental Responsibility and Sustainability for Sport Events: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Event Manag. Res. 2015, 10, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Brundtland. Brundtland Report: Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987; p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- Du Pisani, J.A. Sustainable Development—Historical Roots of the Concept. Environ. Sci. 2006, 3, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiersum, K.F. 200 Years of Sustainability in Forestry: Lessons from History. Environ. Manag. 1995, 19, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, P. A Perspective on Environmental Sustainability. 2004. Available online: https://www.donboscogozo.org/images/pdfs/energy/A-Perspective-on-Environmental-Sustainability.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- White, M.A. Sustainability: I Know it When I See it. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 86, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childers, D.L.; Pickett, S.T.A.; Grove, J.M.; Ogden, L.; Whitmer, A. Advancing Urban Sustainability Theory and Action: Challenges and Opportunities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, J. Environmental Sustainability: A Definition for Environmental Professionals. J. Environ. Sustain. 2013, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Towards the Sustainable Corporation: Win-Win-Win Business Strategies for Sustainable Development. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1994, 36, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Enter the triple bottom line. In The Triple Bottom Line: Does it All Add Up? Assessing the Sustainability of Business and CSR; Henriques, A., Richardson, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; pp. 1–16. ISBN 978-1-84977-334-8. [Google Scholar]

- Talbot, L.M. Introduction: The quest for environmental sustainability. In Foundations of Environmental Sustainability: The Coevolution of Science and Policy; Rockwood, L., Stewart, R., Dietz, T., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 3–24. ISBN 978-0-19-804226-6. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, R. Envisioning Sustainability Three-Dimensionally. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1838–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorov, V.; Marinova, D. Models of sustainability. In Proceedings of the MODSIM 2009 International Congress on Modelling and Simulation, Cairns, Australia, 13–17 July 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Spangenberg, J.H. Institutional Sustainability Indicators: An Analysis of the Institutions in Agenda 21 and a Draft Set of Indicators for Monitoring Their Effectivity. Sustain. Dev. 2002, 10, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mebratu, D. Sustainability and Sustainable Development: Historical and Conceptual Review. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 1998, 18, 493–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, P. Urban Sustainability in Theory and Practice: Circles of Sustainability, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1-315-76574-7. [Google Scholar]

- Fekry, D.; El Zafarany, A.M.; Shamseldin, A.K.M. Develop a Flexible Method to Assess Buildings Hosting Major Sports Events Environmentally through the World. HBRC J. 2014, 10, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hadjichristodoulou, C.; Mouchtouri, V.; Vaitsi, V.; Kapoula, C.; Vousoureli, A.; Kalivitis, I.; Chervoni, J.; Papastergiou, P.; Vasilogiannakopoulos, A.; Daniilidis, V.D.; et al. Management of Environmental Health Issues for the 2004 Athens Olympic Games: Is Enhanced Integrated Environmental Health Surveillance Needed in Every Day Routine Operation? BMC Public Health 2006, 6, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, L.; Knight, J.; Handler, R.; Abraham, J.; Blowers, P. The Methodology and Results of Using Life Cycle Assessment to Measure and Reduce the Greenhouse Gas Emissions Footprint of “Major Events” at the University of Arizona. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2016, 21, 536–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agha, N.; Taks, M. A Theoretical Comparison of the Economic Impact of Large and Small Events. Int. J. Sport Financ. 2015, 10, 199–216. [Google Scholar]

- Horne, J. The Four ‘Knowns’ of Sports Mega-Events. Leis. Stud. 2007, 26, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M. What Makes an Event a Mega-Event? Definitions and Sizes. Leis. Stud. 2015, 34, 627–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolles, H.; Söderman, S. Addressing Ecology and Sustainability in Mega-Sporting Events: The 2006 Football World Cup in Germany. J. Manag. Organ. 2010, 16, 587–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Qu, L.; Spaans, M. Framing the Long-Term Impact of Mega-Event Strategies on the Development of Olympic Host Cities. Plan. Pract. Res. 2013, 28, 340–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermolaeva, P. «Green? Cool. Yours»: The Effect of Sports Mega-Events in Post-Soviet Russia on Citizens’ Environmental Consumption Practises (Cases of 2013 Universiade in Kazan and 2014 Sochi Olympics). J. Organ. Cult. Commun. Confl. 2016, 20, 165. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C. Assessing the Impact of a Major Sporting Event: The Role of Environmental Accounting. Tour. Econ. 2008, 14, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, J.R.; Gold, M.M. “Bring It under the Legacy Umbrella”: Olympic Host Cities and the Changing Fortunes of the Sustainability Agenda. Sustainability 2013, 5, 3526–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupf-Haller, R.; Locher Oberholzer, N. Environmental Planning for Significant Sport Events—A Case Study of the World Ski Championships 2003. Tour. Rev. 2005, 60, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaczun, Z. EURO 2012 vs. Sustainable Development. Probl. Ekorozwoju 2012, 7, 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Death, C. ‘Greening’ the 2010 FIFA World Cup: Environmental Sustainability and the Mega-Event in South Africa. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2011, 13, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokri, A.; Moosavi, S.J.; Dousti, M. Study of Economic, Social and Environmental Impacts of Olympic Games on the Host Cities from Professors and Experts Viewpoint Case Study: London 2012 Olympic. Int. J. Sport Stud. 2013, 3, 984–991. [Google Scholar]

- Fairley, S.; Tyler, B.D.; Kellett, P.; D’Elia, K. The Formula One Australian Grand Prix: Exploring the Triple Bottom Line. Sport Manag. Rev. 2011, 14, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragón-Pérez, A. The Influence of the 1992 Earth Summit on the 1992 Olympic Games in Barcelona: Awakening of the Olympic Environmental Dimension. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2019, 36, 244–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, I.; Heath, E.T. The Potential Contribution of the 2010 Soccer World Cup to Climate Change: An Exploratory Study among Tourism Industry Stakeholders in the Tshwane Metropole of South Africa. J. Sport Tour. 2009, 14, 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Azim Ahmed, T.S. A Triple Bottom Line Analysis of the Impacts of the Hail International Rally in Saudi Arabia. Manag. Sport Leis. 2017, 22, 276–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.; Flynn, A.; Munday, M.; Roberts, A. Assessing the Environmental Consequences of Major Sporting Events: The 2003/04 FA Cup Final. Urban Stud. 2007, 44, 457–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.C.; Lai, Y.H.; Chen, L.S.; Chang, C.M. Influence of International Mega Sport Event towards Cognition of Economic, Social-Cultural and Environmental Impact for Residents: A Case Study of the 2009 Kaohsiung World Games. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 524–527, 3392–3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bama, H.K.N.; Tichaawa, T.M. Major Sporting Events and Responsible Tourism: Analysis of the 2013 Africa Cup of Nations (AFCON) Tournament in Port Elizabeth, South Africa. Afr. J. Phys. Health Educ. Recreat. Dance 2015, 21, 205–219. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, A.; Flynn, A. Measuring the Environmental Sustainability of a Major Sporting Event: A Case Study of the FA Cup Final. Tour. Econ. 2008, 14, 751–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantaki, M.; Wickens, E. Residents’ Perceptions of Environmental and Security Issues at the 2012 London Olympic Games. J. Sport Tour. 2010, 15, 337–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Zhang, J.J.; Ma, X.; Connaughton, D.P. Residents’ Perceptions of Environmental Impacts of the 2008 Beijing Green Olympic Games. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2011, 11, 275–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonsiritomachai, W.; Phonthanukitithaworn, C. Residents’ Support for Sports Events Tourism Development in Beach City: The Role of Community’s Participation and Tourism Impacts. SAGE Open 2019, 9, 2158244019843417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, J.; Biegert, T.; Müller, H.; Elsasser, H. Sustainability of Mega Events: Challenges, Requirements and Results. The Case-study of the World Ski Championship St. Moritz 2003. Tour. Rev. 2004, 59, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govender, S.; Munien, S.; Pretorius, L.; Foggin, T. Visitors’ Perceptions of Environmental Impacts of the 2010 FIFA World Cup: Comparisons between Cape Town and Durban. Afr. J. Phys. Health Educ. Recreat. Dance 2012, 18, 104–111. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.-D. The 2012 London Olympics: Commercial Partners, Environmental Sustainability, Corporate Social Responsibility and Outlining the Implications. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2013, 30, 2197–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, L.M.B.; Ramos, M.B.; Gioda, A.; França, B.B.; de Oliveira Godoy, J.M. Air Quality Monitoring Assessment during the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 191, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bono, R.; Degan, R.; Pazzi, M.; Romanazzi, V.; Rovere, R. Benzene and Formaldehyde in Air of Two Winter Olympic Venues of “Torino 2006”. Environ. Int. 2010, 36, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locke, S.L. Estimating the Impact of Major League Baseball Games on Local Air Pollution. Contemp. Econ. Policy 2019, 37, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P. Evaluation of Ecological Civilization Development in the Post-Olympic Times. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2019, 17, 8513–8525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Cruz, A.R.H.; Dionisio Calderon, E.R.; França, B.B.; Réquia, W.J.; Gioda, A. Evaluation of the Impact of the Rio 2016 Olympic Games on Air Quality in the City of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Atmos. Environ. 2019, 203, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Kaplanidou, K. Examining the Importance of Legacy Outcomes of Major Sport Events for Host City Residents’ Quality of Life. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2017, 12, 903–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Liu, Y.; Du, M. Impact of the 2008 Olympic Games on Urban Thermal Environment in Beijing, China from Satellite Images. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 32, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Tang, A.; Liu, X.; Kopsch, J.; Fangmeier, A.; Goulding, K.; Zhang, F. Impacts of Pollution Controls on Air Quality in Beijing during the 2008 Olympic Games. J. Environ. Qual. 2011, 40, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfitzner, R.; Koenigstorfer, J. Quality of Life of Residents Living in a City Hosting Mega-Sport Events: A Longitudinal Study. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beig, G.; Chate, D.M.; Ghude, S.D.; Mahajan, A.S.; Srinivas, R.; Ali, K.; Sahu, S.K.; Parkhi, N.; Surendran, D.; Trimbake, H.R. Quantifying the Effect of Air Quality Control Measures during the 2010 Commonwealth Games at Delhi, India. Atmos. Environ. 2013, 80, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilani, R.M.; Machado, C.J.S. The Impact of Sports Mega-Events on Health and Environmental Rights in the City of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Cad. Saúde Pública 2015, 31, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Cai, H.; Xie, S. Traffic-Related Air Pollution Modeling during the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games: The Effects of an Odd-Even Day Traffic Restriction Scheme. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 409, 1935–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, C.-C.; Huang, C.-H. An Innovative Trend of Sport Event in Environmental Perspective. In International Conference on Innovative Technologies and Learning; Wu, T.-T., Huang, Y.-M., Shadiev, R., Lin, L., Starčič, A.I., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 625–630. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, A. Research on the Surrounding Environment of Large-Scale Sports Events. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 208, 12057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza Talavera, A.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G.; Koç, M. Sustainability in Mega-Events: Beyond Qatar 2022. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boykoff, J.; Mascarenhas, G. The Olympics, Sustainability, and Greenwashing: The Rio 2016 Summer Games. Capital. Nat. Social. 2016, 27, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fermeglia, M. The Show Must Be Green: Hosting Mega-Sporting Events in the Climate Change Context. Carbon Clim. Law Rev. 2017, 11, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, R.; Cronje, J. Building a White Elephant? The Case of the Cape Town Stadium. Int. J. Sport Policy Polit. 2019, 11, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, A.; Schlenker, K.; Schulenkorf, N.; Brooking, E. The Social and Environmental Consequences of Hosting Sport Mega-Events. In Managing Sport Mega-Events; Frawley, S., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 150–164. ISBN 978-1-138-79677-5. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Dick, R.; McNabb, A.; YinChu, T. Preparation for an International Sport Event: The Promotional Strategies of 2009 Kaohsiung World Games. Sport J. 2010, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Business Group. The Report: South Africa 2013; Oxford Business Group: Oxford, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1-907065-85-9. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).