Abstract

Health prevention and promotion are increasingly important in the school context. Beyond physical education, measures focused on physical activity (PA) are implemented to enhance students’ mental and physical health. The first aim of this study was to systematically describe two school-based health promotion measures that were based on the idea of active school concepts against the background of the German educational and health policies as well as the German school system. The second aim was to assess the process and implementation quality and potential outcomes of the measures and to identify factors that promote or hinder the implementation of the measures. Both measures were funded and supported by health insurance companies. The measure Fitness at School supported approximately 1195 schools in the last thirteen years by promoting PA-related projects at schools. In the measure Active School NRW, schools that best implement the concept of an active school were awarded. The results provide insights into the conditions that hinder and support the implementation of PA-based health promotion measures at schools and are discussed against the background of sustainable health promotion. Overall, the evaluation indicates that financial investments in health-prevention and -promotion measures in the school setting are beneficial.

1. Introduction

Internationally, health prevention and promotion in schools have become increasingly important in the last decades [1,2,3]. In Germany, health education has been considered a core aspect of school development processes, at least since the corresponding resolution of the Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs of the Länder in the Federal Republic of Germany in 2012. However, sustainable measures focusing on physical activity (PA) and health promotion in German schools have hardly been investigated [4]. The implementation and evaluation of such measures require the consistent consideration of organizational structures as well as objectives of educational and health policy [5].

In this study, two measures that meet these requirements were evaluated. In doing so, the aims of the present study were (1) to systematically describe the measure in the context of the German educational and health policies, (2) to assess the process and implementation quality and potential outcomes, as well as (3) to identify factors that promote or hinder the implementation of the measures. This is to generate action knowledge for the implementation of future health promotion measures in the school context.

The first measure is the implementation of the political action program Active School in NRW (AS) of the federal state North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW). The measure aims to integrate PA into the learning environment of children and adolescents in schools [6]. The implementation of this measure is funded by both the federal state and health insurance companies. The second measure is also funded by a leading health insurance company: The measure Fitness at Schools (FaS) supports schools in offering PA-based extra-curricular projects for students and in cooperating with sports clubs.

Before describing the measures and their evaluations in more detail, the educational and health policy structures in Germany are explained. Additionally, the theoretical and empirical background regarding physical activity and health promotion in childhood and youth is presented. Both aspects form the basis for the implementation and evaluation of the two measures. Lastly, the results are discussed against the background of sustainable health promotion in schools.

1.1. Physical Activity and Health

Scholars are increasingly advocating comprehensive health promotion, including exercise and sports, from early school age. Health-related attitudes and behavior patterns formed at a young age often continue to have an effect in adulthood [7,8]. Therefore, great importance is attached to childhood and adolescence in the context of promoting a health-conscious lifestyle. This is based on a large body of research from various scientific disciplines. International and national reviews as well as meta-analyses of the last 10 years have consistently shown great evidence of positive correlations between PA or fitness levels and various physical and mental health indicators [9,10]. For example, a higher activity level combined with a higher motor performance leads to positive effects in terms of the cardiovascular system (i.e., metabolic biomarkers, cardiovascular fitness, blood levels [11], obesity and pre-adiposity (i.e., free fat mass) [12,13], bone health [14], psycho-social health (including well-being, depression, anxiety, mood, life satisfaction and quality, self-confidence, prosocial behavior) [13,15] as well as cognitive health (including cognitive and academic performance) [16]).

To sum up, the higher the activity level and the performance parameters (intensity and frequency) are, the higher are the health benefits. Accordingly, when the physical activity level decreases, motor performance and health parameters deteriorate. For example, these effects were shown during the COVID-19 pandemic regarding mental health indicators in children and adolescents [17,18].

However, positive health effects only result from regular PA. The environment and context in which children and adolescents can be physically active play a crucial role in regular PA. Therefore, systematic health promotion through PA should take place in the immediate environment of children and adolescents. In addition to the family, the school is an important environment for this [1,19].

1.2. Physical Activity-Based Health Promotion Measures in Schools

Some studies investigated the effect of school-based PA interventions on various outcomes like average PA [20], fitness [21], or academic outcomes [22]. Love et al.’s [20] meta-analysis of randomized control trials (RTCs) for promoting accelerometer-assessed PA through school-based PA interventions revealed no effects of the interventions. Whereas Love et al. [20] included only RTCs lasting at least four weeks, Kriemler et al. [21] summarized RCTs and control trials with a duration of the interventions of at least three months and several more outcome measures (e.g., observations, fitness parameter, general PA) in their review. Their results documented consistently positive effects on students’ PA as well as partly positive effects on their fitness. Particularly for younger children, Pozuelo-Carrascosa et al. [23] found evidence that school-based PA interventions have a positive effect on children’s cardiorespiratory fitness. In the context of school-based PA interventions, a particular focus is on the effect of physically active academic lessons, where academic content is taught using physically active teaching methods, resulting in physically active learning of the students [22,24]. There is evidence of positive effects of active lessons/learning on PA levels [22,25], academic outcomes [25,26,27], academic motivation [28], and partly on health outcomes, especially the BMI [22,27]. Another focus is on active breaks: Active breaks are non-curriculum-linked activities during the lessons that require no or less equipment and are easy and fast to realize. There also is evidence of positive effects of active breaks on PA levels, health outcomes (e.g., physical fitness), and academic outcomes (e.g., time-on-task) [24,27,29]. The terms active lessons, active learning, and active breaks are defined slightly differently in the literature [24], in this study, the terms are used as described above.

The studies basically indicate that school-based PA interventions can be successful, but not necessarily. Naylor et al.’s [30] review revealed that the specific way of the implementation of school-based PA interventions has a decisive influence on its success. Therefore, several scholars call for identifying and developing implementation strategies [3,21] and the assessment of implementation quality [5,20]. Given the fact that the implementation of school-based PA interventions underly country-specific conditions (e.g., different health policies, school systems, and curricula), the implementation strategies and their qualities must be analyzed concerning these conditions [19]. Nathan et al. [5] identified and summarized barriers and facilitators to the implementation of school-based PA interventions but also pointed out that their results are not generalizable to measures in schools in other jurisdictions as most of the analyzed school-based PA interventions were carried out in North America.

This study takes up these desiderata by (1) systematically describing two school-based PA interventions in the context of German educational and health policies and the school system, (2) assessing the process and implementation quality and potential outcomes, as well as (3) identifying factors that promote or hinder the implementation of the measures. This is to generate action knowledge for the implementation of future PA-based health promotion measures in (German) schools and to contribute to the international discourse about school-based PA interventions from a perspective and context, which were hardly present there until now [19].

1.3. Educational and Health Policy Structures in Germany

Germany differs from many developed countries in the world in terms of both its education and health care systems. For example, Germany is one of a few other countries with compulsory education and compulsory health insurance. This means that all children and young people of the appropriate age must attend school and every citizen must have health insurance. Since these two aspects are important contextual factors for the measures presented and evaluated later, they are presented in more detail below.

1.3.1. Health Policy and Health Insurance in Germany

Health insurance is mandatory for all people residing in Germany [31]. Approximately 87% of the population (about 70 million people) are insured under statutory health insurance (SHI). All people with SHI have the same entitlement to care if they fall ill, regardless of their monthly financial contribution. The amount of contributions is based solely on their income. Per the solidarity principle of SHI, people who earn well pay more than people who earn less, and healthy people pay the same as sick people. In this way, all insured persons jointly bear the costs of medical care in the event of illness and the personal risk of loss of earnings. The amount of the contribution is initially the same for SHI funds (there are currently 97 SHI funds in Germany, which are organized in the central association of statutory health insurance funds as well as the association of substitute health insurance funds). The contribution is 14.6% of gross income—but only up to a certain salary level, the so-called contribution assessment ceiling [32]. Employers and insured persons each pay 7.3% of the 14.6%. Furthermore, each SHI fund can levy additional contributions from its insured if the membership fees and other funds are not sufficient to cover the costs. In addition, about 11% of the people living in Germany are members of a private health insurance fund (PHI), which are more expensive but provide better services.

Until 2015, the main concern of all health insurers was to finance curative care, but this changed when the Prevention Act was passed [33]. The law on strengthening health promotion and prevention came into force throughout Germany on 25 July 2015. Through this law, health promotion and prevention have a legal basis. According to the Prevention Act, health promotion and prevention should take place in the living environment—where people live, learn, and work. The law focuses on targeted cooperation between the players in health prevention and promotion. The health insurance funds, and long-term care insurance funds, must invest more than 500 million euros in health promotion and prevention: Since 2016, they have had to spend at least seven euros per insured person on disease prevention (primary prevention). Four of the seven euros must be invested in measures in living environments, two each for workplace health promotion and two for prevention in other living environments (e.g., schools) [34]. The amounts are adjusted annually. This means that health prevention and promotion are a legal obligation in Germany, which must be financed by German health insurance funds. Measures for health promotion and prevention in living environments that are supported by funds from the Prevention Act must meet specified criteria. Funding criteria and conditions are laid down in a binding guideline [35]. An essential criterion is that the measures are evaluated. The health insurance funds can either develop and implement an appropriate measure on their own, or commission third parties for this, as was the case for one of the evaluated measures in this study. Even before the Prevention Act, health insurers were supposed to spend money on prevention, but the requirements were less stringent (especially the amounts were not fixed). However, the other measure evaluated in this study was funded within these former guidelines [36].

1.3.2. Schools and Health Promotion in Germany

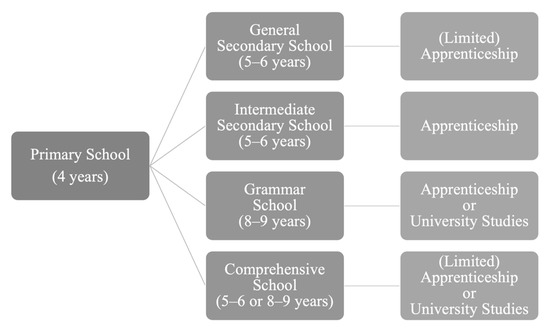

The exact structure of the school system is different in every of the 16 German federal states. The following describes the basic structure of the school system that applies to most of the German states (Figure 1) [37]. All children must attend school for nine years: four years in primary schools and at least five years in secondary schools. The secondary school track is divided into three types of schools: low-, intermediate-, and academic-track schools (i.e., general secondary schools, intermediate secondary schools, and grammar schools). General secondary schools (Hauptschulen) provide vocationally oriented education and the lowest school-leaving certificate after the 9th or 10th grade. Intermediate secondary schools (Realschulen) also prepare for vocational education, but they focus more on administrative and commercial work than general secondary schools that focus more on manual labor. After 10th grade, intermediate secondary schools provide an intermediate school-leaving certificate. If the final grades are good enough, it is possible to transfer to grammar schools. Grammar schools provide an academic curriculum that prepares for higher education and the highest school-leaving certificate after 12th or 13th grade. Besides these three types of schools, there are also comprehensive schools (Gesamtschulen) that provide all school-leaving certificates and secondary schools (Sekundarschulen) that provide the certificates of general and intermediate secondary schools. Additionally, students who dropped out of school after less than 9 years, or students who start vocational training, must attend a vocational school. Vocational schools are specialized for a particular trade or field of work and, depending on the specialization, they can issue one or more of the three school-leaving certificates. Besides these general school types, there are special schools, where the majority of students with special educational needs are educated [38].

Figure 1.

Simplified representation of the school system in Germany.

Although schools in Germany are under the control of the respective state government, each school has a high degree of autonomy regarding concrete measures for quality assurance and development. However, there are instruments for external evaluation of school quality. These instruments are output-oriented. They define certain goals that schools and students should achieve (Paulus, 2009). In the federal state NRW, the topics of standardization, individualization, and school development are the focus of external evaluation. Therefore, the Quality Table for Quality Analysis in Schools (QT) was developed as a framework for the external evaluation of school quality [39]. It also provides impulses for internal evaluation and is thus the basis for the quality-oriented self-management of schools and for internal quality management. According to the QT, health promotion measures based on sports and physical activity are considered measures for promoting school quality. Therefore, the measures investigated in this study can be seen as a measure for promoting school quality as well.

1.4. Evaluation of Active School NRW and Fitness at School

The two evaluated measures (i.e., Active School NRW (AS) and Fitness at School (FaS) were carried out in schools in the federal state NRW. Both measures were scientifically supervised. The investigations were approved by the ethics committee of Bielefeld University (No. 2022-130). The AS measure took place between 2004 and 2010 with a follow-up survey in 2015. The FaS measure is still running, but the given investigation refers to a period between 2017 and 2019.

The evaluation of both measures is based on the evaluation hierarchy of Rossi et al. [40]. The evaluation focused primarily on the third level of the hierarchy (assessment of program process and implementation) and to some extent on the fourth level (assessment of program outcome and impact). The need for physical activity and health promotion programs is evident against the backdrop of global inactivity among children and adolescents (first level) [41]. The concepts underlying the measures have been explained and justified in detail elsewhere (second level) [6,42]. In detail, the evaluation of the AS measure aimed to assess the process and the implementation of the project, whereas the evaluation of the FaS measure aimed to assess the program process and the implementation of the project as well as the project outcomes.

2. Evaluation of Active School NRW

2.1. Active School NRW

The implementation of the measure Active School NRW was conceptualized and executed as a school competition. Schools were awarded for implementing the concept of an active school in as many areas as possible. The term Active School is defined and interpreted differently [6]. The concept of active schools in this measure is conceptualized broadly and is based on the idea that active schools should integrate physical activity in the whole school context by involving students, teachers, parents, and school administration and considering the individual conditions of the school and its environment. Thus, this concept is a multi-component school-based physical activity program [43]. Basic elements of the active school concept are active lessons (i.e., active sitting, active breaks during the lessons, and active learning), active school breaks, and regular physical education (PE) lessons. These points form the basis of the criteria for the competition. Based on the Quality Table for Quality Analysis in Schools (QT) [39], the criteria were differentiated and expanded into nine categories: School data, school organization, school equipment, further teacher training, information/communication, fields of action (lessons, PE, recess, diagnostics, and compensatory sports, extra-curricular activities, class trips), cooperation, evaluation, and all-day activities. Schools could take part in the competition by filling in an online questionnaire that covered all nine categories. The questions were evaluated and scored. The 50 best schools had to submit an additional short presentation outlining why their school is an Active School. The finalists were visited by a jury. Since the questionnaire is based on the QT, which is provided by the Ministry of Education, it serves not only as a tool for participation in the competition but also as an instrument for self-evaluation of the schools and thus for quality improvement and quality assurance. The winners of the competition can bear the title Active School NRW. This award significantly improves the external image and reputation of the schools. In addition, the winning schools received EUR 500–1500 depending on their ranking.

For the given evaluation, the focus was on the implementation of the active school concept at the class level, focusing on the use of physical activity in lessons, especially through active breaks or active learning.

2.2. Materials and Methods

2.2.1. Data Collection

The evaluation is based on data from the online questionnaire from 2010 and data from a follow-up survey from 2015. In 2010, 353 different schools participated in the competition, including primary schools (n = 201), general secondary schools (n = 15), intermediate secondary schools (n = 20), grammar schools (n = 28), comprehensive schools (n = 19), vocational schools (n = 13), and special schools (n = 57). The distribution of school types in the sample corresponds to the absolute distribution of school types in North Rhine-Westphalia at that time [44]. For the follow-up survey, all schools that took part in the competition were contacted. For legal data protection reasons and to increase the response rate, the data was collected anonymously. A shorter version of the online questionnaire for participation in the competition was used for the follow-up survey. In total, 206 schools answered the questionnaire, including primary schools (n = 119), secondary schools (general and intermediate schools, comprehensive and grammar schools) (n = 60) and special schools (n = 27). The response rate was around 66%. Due to data protection requirements on the part of the school authorities, the data from the follow-up could not be linked to the data from 2010. It was therefore not possible to differentiate between the school types of secondary schools. For both surveys, the questionnaire was available on the project’s homepage.

2.2.2. Measures

In the application questionnaire as well as in the follow-up questionnaire, the schools were asked if there was a certain person or group who is responsible for the implementation of the active school concept (yes/no). The implementation of the active school concept at the classroom level was measured by three items in the application questionnaire. In the first item, schools should state how many teachers integrate physical activity into their teaching on a three-point scale (less than half, about half, more than half). In the other two items, schools had to indicate on four-point scales (1 = never, 4 = often) the extent to which active breaks and methods of active learning (e.g., representation of terms or the experience of shapes through movement) were integrated into the lessons for each grade. In the follow-up survey, it was asked whether active breaks and active learning had occurred in the lessons at school (yes/no).

2.2.3. Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS 27. There were no missing values. All data were first analyzed descriptively. To investigate differences between school types regarding dichotomous variables, contingency tables, and chi-square tests were calculated. Effects of school types on metric variables were investigated using Analyses of Variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni-corrected post-hoc tests [45]. To analyze differences between grades within a school type and differences between school types as well as interactions of these two factors, two-way mixed ANOVAs were used. If the assumption of sphericity was violated, Greenhouse–Geiser correction was applied. For the ANOVAs, partial eta-squared was used as effect size [45].

2.3. Results

2.3.1. Responsibilities for Active School Concepts

Table 1 shows the percentage of schools that reported having a person or group responsible for implementing the concept of active school by school type. From the time of application to the time of the follow-up survey, the percentage of all school types has decreased. At both points in time, special schools had the highest percentage of a single person or group responsible for the implementation of an active school concept, elementary schools had the second highest percentage. At the time of application, the distribution was dependent on school type (p = 0.04) but not at the follow-up (p = 0.07).

Table 1.

Percentage of schools with persons/groups responsible for implementing the concept of active schools.

2.3.2. Implementation at the Classroom Level

The one-way ANOVA showed that the proportion of teachers who integrated physical activity into their lessons significantly depended on the school type, F(5, 340) = 65.84, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.53. Post-hoc tests specified that significantly more teachers at primary schools and special schools integrated physical activity into their lessons compared to the other school types (Table 2).

Table 2.

Post-hoc tests for the effect of school types on the proportion of teachers who integrated physical activity into their lessons.

Regarding the effect of school type and grade on the implementation of active breaks the two-way ANOVA indicated a significant effect of school type, F(1, 134) = 4,99, p = 0.001, η2 = 0.13, and grade, Greenhouse–Geiser F(2.25, 301.40) = 102.47, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.43, as well as a significant interaction of school type and grade, F(9.00, 301.40) = 2.40, p = 0.012, η2 = 0.07.

Post-hoc tests for the effect of school type showed that special schools used active breaks significantly (p < 0.05) more often than intermediate secondary schools and grammar schools (Table 3). More precise and following the significant interaction, the post-hoc tests also revealed that the effect of the school type depended on the grade: The tests indicated that special schools used active breaks significantly (p < 0.05) more often than grammar schools in 5th grade, intermediate secondary schools in 7th grade, intermediate secondary schools and comprehensive schools in 8th grade, intermediate secondary schools, comprehensive schools and grammar schools in 9th grade as well as than all other school types in 10th grade. Post-hoc tests for the effect of the grade within a school type revealed significant differences between all grades (p < 0.05), except for the difference between the 9th grade and 10th grade (Table 3). The values indicated that with higher grades, the use of active breaks becomes less frequent.

Table 3.

Post-hoc tests for the effect of school type and grades on the implementation of active breaks.

Regarding the implementation of active breaks in primary schools, the one-way ANOVA showed a significant effect of grade, Greenhouse–Geiser F(1.66, 332.52) = 98.53, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.33. Post-hoc tests indicated that the frequency of use of active breaks decreases significantly (p < 0.01) as the grade increases (M1st grade = 3.8, M2nd grade = 3.7, M3rd grade = 3.4, M4th grade = 3.3).

Results from the follow-up survey showed that a large proportion of schools integrated active breaks into lessons to implement the concept of active schools (Table 4). The percentage of schools that did this depended significantly on the school type, χ2(2, N = 206) = 5.51, p = 0.06. Primary schools used active breaks more frequently than special schools, followed by secondary schools. This distribution corresponds to the results at the time of application.

Table 4.

Percentage of schools that used active breaks for the implementation of the active school concept.

Regarding the effect of school type and grade on the implementation of active learning, the two-way mixed ANOVA indicated a significant effect of school type, F(4, 134) = 3.01, p = 0.021, η2 = 0.08, and grade, Greenhouse–Geiser, F(2.01, 269.41) = 38.41, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.22, as well as a significant interaction of school type and grade F(8.04, 269.41) = 3.46, p = 0.001 η2 = 0.09.

Post-hoc tests for the effect of school type showed no significant differences between the average values of the school type but revealed significant differences between school types within certain grades. The tests indicated that in special schools, methods of active learning were used significantly (p < 0.05) more often than in intermediate secondary schools in 5th grade. Moreover, general secondary schools used these methods significantly (p < 0.05) less often than comprehensive schools in 8th grade and comprehensive schools and intermediate secondary schools in 8th grade. Post-hoc tests for the effect of the average effect of grades revealed significant differences between all grades (p < 0.05), except for the difference between the 5th and 6th grade, as well as between the 8th, 9th, and 10th grade (Table 5). The tests also indicated that these differences were due to differences within the general secondary schools and special schools. Within both school types, methods of active learning seemed to be used less with increasing grades.

Table 5.

Post-hoc tests for the effect of school type and grades on the implementation of methods of active learning.

Regarding primary schools, there was a significant effect of the grades, Greenhouse–Geiser, F(1.76, 351.37) = 158,96, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.44. Post-hoc tests indicated that the frequency of use of methods for active learning decreased significantly (p < 0.001) as the grade increased (M1st grade = 3.8, M2nd grade = 3.6, M3rd grade = 3.1, M4th grade = 3.0).

Results from the follow-up survey showed that a large proportion of schools integrated methods of active learning into lessons to implement the concept of active schools (Table 6). The percentage of schools that do so depended significantly on the school type, χ2(2, N = 206) = 11.38, p = 0.003. Primary schools used methods of active learning more frequently than special schools, followed by secondary schools. This distribution corresponded to the results at the time of application.

Table 6.

Percentage of schools that used methods of active learning for the implementation of the active school concept.

2.4. Discussion

This evaluation of the AS measure was set out to investigate the implementation quality and sustainability of the active school concept considering different school types.

Data from the project application and the follow-up survey showed that at these points in time, there was a majority of schools with a single person or group responsible for the implementation of the concept, but the number decreased. Even if teachers were still motivated to implement the concept, despite the lack of financial incentives at the time of the post-survey, schools often experienced staff changes and competing projects that required attention during several school years [46]. A dependency on the type of school at the administrative level was evident at the time of the project application, which also occurred in the following analyses on the class level.

Regarding the implementation of physical activity in lessons, the results revealed that more teachers in primary schools and special schools integrated physical activity (i.e., active breaks and methods of active learning) into their lessons. These results can partly be explained, on the one hand, by the fact that elementary-school-aged students have a higher need for physical activity as well as a lower attention capacity [47,48]. Moreover, from a didactic perspective, teaching in primary schools (in Germany) is more implicit and play-oriented compared to secondary schools, so the use of PA-based methods is more anchored in the curricula [49]. For this reason, there are also significantly more didactic materials available for designing active breaks at primary schools [50]. On the other hand, students at special schools also tend to be less cognitively capable, so physical activity may be used more frequently there to enable focused studying. In addition, in both school types, the demands on the social education of the students are higher than in the other types of schools [49,51]. Since active breaks and methods of active learning are often playful and collaborative, they could also be used to promote social learning at these school types.

The analyses also showed an effect of grade. From first grade to tenth grade, the use of active breaks decreased in all school types. This is only partially true for the use of active learning methods. Here, the decrease with increasing grade was only seen in primary schools and special schools, and up to the seventh grade in general secondary schools. The reduction in the use of active breaks can be explained by the fact that learning, performance, and marks become increasingly relevant with increasing grades since finals and graduation are drawing closer. Active learning methods focus primarily on learning, while active breaks focus on physical activity [24]. Therefore, teachers appear to reduce the use of active breaks, but not the use of active learning methods, which they thus consider to be of greater benefit in achieving their learning goals. In contrast, teachers in special schools seem to use active learning methods as well as active breaks less often as grade increases. This may be due to the fact that in contrast to the other types of schools, children at special schools do not attend any further school after the tenth grade and must be prepared for working life. By reducing the active elements, an attempt could be made to prepare them for a daily working life in which regular physical activity is rather rare.

Overall, results showed that the implementation of the concept of the active school depends very much on the school type and grade.

3. Evaluation of Fitness at School

3.1. Fitness at School

The project Fitness at School (FaS) is funded by the German health insurance AOK (Allgemeine Ortskrankenkasse/General Local Health Insurance) and supported by the Ministry of Education NRW [52]. Since 2015, the project has fallen under the Prevention Act. That is why the AOK can use the measure to fulfill its legal obligations to use financial resources for health prevention. Since the school year 2009/2010, the project has been offered to all the approximately 1600 secondary schools in North Rhine-Westphalia. Schools can apply ideas for physical activity-based health promotion projects (e.g., implementation of extracurricular activities and collaborations with sports clubs, sports assistant training, and teacher training courses). The goals of the projects should be to improve students´ fitness, guarantee the provision of a wide range of sports, and encourage and enable students to do sports for life [53]. A special feature of FaS is that schools must develop the ideas for the projects themselves considering the needs of their students and the existing equipment. Therefore, the projects are needs-based and customized. Schools must describe their school’s situation as part of their application and present ideas for a project derived from this. The applications are submitted online. A team of experts, consisting of sports scientists, is available by phone or e-mail to answer questions about the application process or the project ideas. A committee of scientists and representatives of the AOK and the Ministry of Education NRW decide which projects will be funded. Funded schools receive up to EUR 5000 over two years. The first half of the money is paid at the start of the project, and the second half after one year. However, for the disbursement of the second installment, the schools must participate in an interim survey. The interim survey as well as a voluntary final survey after the second year are answered online. Since the school year 2009/2010, the AOK has funded projects with a total of approximately EUR 3 million. The funded projects can be divided into the following thematic areas: Getting to know new sports/facilitating the way into sports clubs, implementing more movement into the school day, social learning, training of sports assistants, inclusion/integration, and adventure/climbing/nature [54].

3.2. Materials and Methods

3.2.1. Data Collection

Data from applications between 2009 and 2021 were used for descriptive evaluation. During this period, 1195 schools had applied. For a detailed evaluation, data from the interim survey in 2018 and the final survey in 2019 were used. The participating and surveyed schools started their projects in 2017. In total, 58 schools participated in both surveys. The schools included general secondary schools (n = 3), intermediate secondary schools (n = 6), secondary schools (n = 2), comprehensive schools (n = 21), grammar schools (n = 9), vocational schools (n = 7) and special schools (n = 10). Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the data from 2020 onwards are not suitable for a representative evaluation of the project.

3.2.2. Measures

To evaluate the acceptance of the individual project, each school had to indicate on a three-point scale (no, partly, yes) whether certain groups of people (e.g., parents and students) accepted the project and participated in it. To evaluate the project’s outcomes, the schools had to indicate on the same scale whether certain project objectives had (already) been achieved. Both were asked in the interim and final survey. The following aspects were only part of the final survey: It was asked whether the expectations of the project were met for a final overall evaluation. To assess facilitators and barriers for the implementation of the project, the schools were asked to rate given facilitators and barriers in terms of their importance for the success of the project on a four-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree).

3.2.3. Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS 27. Cases with missing values were deleted listwise. Most of the data were analyzed descriptively. To analyze the development of the acceptance and the goal-achievement of the projects, paired t-tests were performed. Cohen’s d was calculated as effect size. Mean values were formed over the assessments of the barriers and facilitators for the project implementation. Based on these mean values, rank orders were formed.

3.3. Results

3.3.1. Project Process

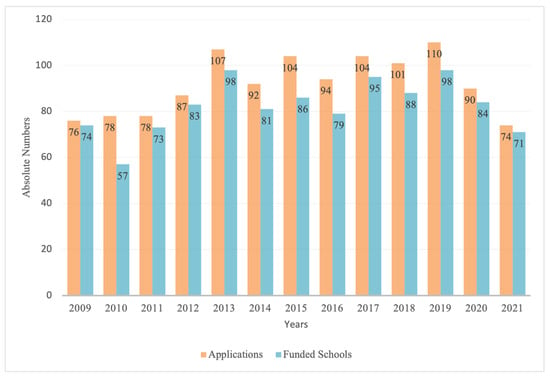

Figure 2 illustrates the number of applications and the number of funded schools. From 2009 to 2021, 1195 applications were submitted, and 1067 projects were funded. In the first five years, the data showed an increase in applications and funded projects. Until 2020, both remained roughly constant. From 2020, both decreased. Between 2009 and 2021, an average of 89% of projects were funded.

Figure 2.

Number of applications and funded schools.

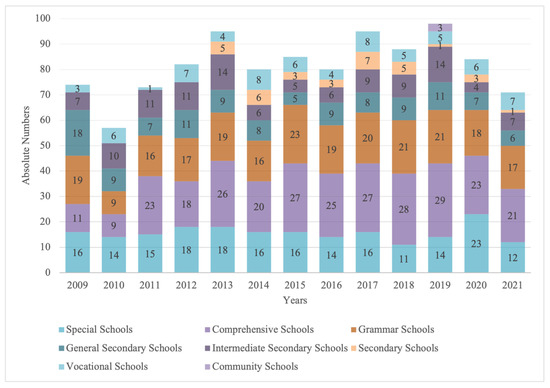

Figure 3 illustrates the number of participating and funded schools by school type. The proportions of school types remained rather stable over time. The distribution of school types in the sample for the detailed evaluation (2017) corresponds to the absolute distribution of school types in North Rhine-Westphalia at that time, only comprehensive schools are slightly overrepresented (15% more) [44]. This distribution is similar in the other years. About 50% of schools participated once in the project, 25% twice, 12.5% three times, and 12.5% more often.

Figure 3.

Number of participating and funded schools by school type.

3.3.2. Implementation and Outcomes

Regarding the project acceptance and involvement, results indicated, that the number of participants increased significantly from interims to post-survey (Table 7), whereas the acceptance and involvement of the parents, as well as the acceptance of the colleagues, decreased significantly. Student involvement and acceptance remained stable at a high level.

Table 7.

Project acceptance, involvement, and outcomes from interim to post-survey.

The data also revealed that schools’ perceptions of achievement of project goals did not change over time (Table 7). Most schools indicated that they were (partially) meeting project goals. Additionally, 84.2% of the schools stated that their expectations of the project have been fully or mostly met; 7.0% of the schools were undecided. That their expectations of the project were hardly or not met was stated by 8.8% of the schools.

Table 8 shows the schools’ ratings of the factors that facilitate the implementation of the respective project, in descending order of relevance. The data showed that all factors except networking with other schools were important or rather important for the implementation of the project. Particularly important were the support from the school management, cooperation with extracurricular partners, and long-term commitment of all project participants.

Table 8.

Facilitators for the implementation of PA-based health promotion projects.

Table 9 shows the schools’ ratings of the factors that hinder the implementation of the respective project, in descending order of relevance. The generally low values indicate that the schools did not consider the factors listed to be a barrier to the implementation of PA-based health promotion projects. However, personal workload and a lack of time, as well as external factors, were seen as comparatively most obstructive.

Table 9.

Barriers to the implementation of PA-based health promotion projects.

3.4. Discussion

The analyses aimed to assess the program process and implementation as well as the program outcome of the FaS measure. The data on the temporal course of the measure showed on the one hand that most schools participated only once or twice in the measure. This indicates a sustainable implementation of the respective projects at the schools. On the other hand, the initial increasing and then constant number of applicants indicated that the measure was well disseminated and that there was a high demand for financial support for the implementation of PA-based health promotion projects at schools. The distribution of school types also indicated that all school types were equally addressed by the measure. The overrepresentation of comprehensive schools was because all-day programs, in which projects can take place, are traditionally implemented at this school type [55].

The data on acceptance and involvement during the project show different results. On the one hand, participation in the projects increased, which indicates that implementation of the projects takes time. On the other hand, the acceptance of the projects on the part of the parents and colleagues decreased. One reason for this could be the organizational changes due to the new school year (new timetable, new tasks) [56]. However, overall, the acceptance of the projects on the part of the staff and the parents as well as the students’ involvement and acceptance remain at a high level, indicating a positive implementation of the projects. The results concerning the projects’ outcomes also confirm this conclusion. The outcomes are rated high in all areas throughout the project. In particular, the results of the outcomes in the final survey supported the results of the interim survey. Although the further funding of the projects was independent of the results of the interim survey, it can be assumed that the final survey yielded more valid results, since the projects could no longer be funded after the final survey anyway.

Regarding the facilitators and barriers that may influence the implementation of PA-based health promotion projects, the findings echoed results from a recent review by Nathan et al. [5] on barriers and facilitators to the implementation of physical activity policies in schools. Sufficient time and the support of the school administration seem to be particularly crucial for the implementation of PA-based health promotion projects in schools. It is striking that the relevance of all potential barriers is rated rather low. This can be attributed to the fact that the respective projects are developed precisely by the schools (with professional advice) for the schools. Specific local conditions and obstacles can therefore already be anticipated and considered during the planning phase. Therefore, a lack of sensitivity to school culture and school needs, which were identified as obstructive in other studies, were not relevant in this measure [57]. In addition, cooperation with external partners is rated as an important factor for the successful implementation of the projects. Thus, the participation of external partners, the schools (incl. school management), and external experts prove to be particularly relevant for a successful implementation of PA-based health promotion projects at schools. This finding provides empirical evidence for the effectiveness of the co-production of active lifestyles through an interactive-knowledge-to-action approach [58] (also the Cooperative Planning process [59]) in extracurricular settings. According to this approach, all relevant actors of a setting should be involved in the planning of health promotion projects in certain settings to systematically make joint decisions and implement the project as a co-production. Overall, the evaluation of the FaS measure indicates a good program process and implementation as well as satisfactory outcomes.

4. General Discussion

In this study, two PA-based health promotion measures, which were based on the idea of active school concepts, were described systematically against the background of German educational and health policies. Due to national specifics in the context of school health promotion, these descriptions allow for a better contextualization of the evaluation results and better international comparability [5]. Another aim of the study was to analyze the process and implementation quality as well as potential outcomes of the measures. The results were generally positive, suggesting that the measures’ primary goal of encouraging more physical activity of children had been achieved. However, there were also indications of a need for action (e.g., school form-specific training and materials for active breaks). In particular, the results on factors facilitating or hindering the implementation of the FaS measure allow a connection to the discussion on implementing health promotion projects based on cooperative planning processes [58,59]. The results point to the potential of this approach and to the need to consider it more strongly in the planning and implementation of future measures.

The implementation of PA-based health promotion measures in German schools have hardly been investigated. Therefore, these results make a significant contribution to a better understanding of the implementation of such measures. It should be noted that both measures are externally funded, and schools must actively seek funding. This ensures that only schools that have identified a need for such measures at their school and are willing to act are funded. In addition, external funding by health insurers falls under the Prevention Act [33]. This means that the evaluation of the measures is obligatory, which increases the likelihood of a appropriate implementation at the schools [57]. It should be noted, however, that such measures represent an additional burden for teachers. Therefore, schools are dependent on committed teachers. As already stated by Jourdan et al. [60], teachers should be prepared to initiate and implement such measures in schools, especially through training and continuing education.

Although this evaluation of the measures provides initial empirical evidence for the implementation of aspects of the active school concept, the results also have limitations. Since some data are only based on the subjective view of the teachers, other and more valid data from the schools should be collected in future studies (e.g., students’ views, observations, or data from wearable internet of things devices [61]). What is more, the imprecise allocation of data in the longitudinal analyses allows only a limited interpretation. In principle, against the background of the rather low evidence on the implementation of such measures, larger-scale panel studies should be carried out to generate action knowledge for better implementation of the measures. This study has made an initial contribution to this using two measures from Germany as examples.

5. Conclusions

Overall, the evaluation indicated that financial investments in health-prevention and -promotion measures in the school setting are beneficial. In schools, it is possible to familiarize many children with an active lifestyle in the long term through easily accessible PA offers (i.e., PA in lessons and extracurricular activities), regardless of the children’s social status. This is particularly important as students spend more and more time in schools and access to sports clubs becomes more difficult, especially for socially disadvantaged students [62]. The dependence of the implementation quality on school types should also be considered against the background of social inequality since the students’ decision on school types also differ according to their social situation [63]. Additionally, the findings concerning differences between school types should be considered in future projects to implement such concepts. For example, school-form-specific and age-specific didactic materials for implementing active breaks and methods of active learning should be created and evaluated. Moreover, both topics should be given greater consideration in the teacher training for secondary schools as these methods can also be effective with adolescents [64]. Nevertheless, the effects of school type and grade found in this study should be further investigated, especially in other school systems, to generalize the results and gain better insights in the factors affecting the implementation of PA-based health promotion measures in schools. These measures require more attention from a scientific perspective, but should also be supported from political stakeholders, as evidence-based and well-implemented measures can, for example, help achieve the goals of the World Health Organization’s Global Physical Activity Action Plan [65].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B., I.P., B.G. and U.L.; methodology, M.B., I.P. and U.L.; formal analysis, M.B.; investigation, M.B., I.P. and U.L.; resources, I.P. and B.G.; data curation, M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B., I.P. and U.L., writing—review and editing, M.B., I.P., B.G. and U.L.; visualization, M.B. and U.L.; supervision, I.P. and B.G.; project administration, U.L.; funding acquisition, M.B., I.P., B.G. and U.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the AOK Rheinland/Hamburg and the Ministry for School and Education of the Federal State of North Rhine-Westphalia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Bielefeld University (protocol code: 2022-130, date of approval: 16 May 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to data privacy reasons and local legislation.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support for the publication costs by the Open Access Publication Fund of Bielefeld University and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kibbe, D.L.; Hackett, J.; Hurley, M.; McFarland, A.; Schubert, K.G.; Schultz, A.; Harris, S. Ten Years of TAKE 10!®: Integrating physical activity with academic concepts in elementary school classrooms. Prev. Med. 2011, 52, S43–S50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osganian, S.K.; Parcel, G.S.; Stone, E.J. Institutionalization of a school health promotion program: Background and rationale of the CATCH-ON study. Health Educ. Behav. 2003, 30, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassar, S.; Salmon, J.; Timperio, A.; Naylor, P.-J.; van Nassau, F.; Contardo Ayala, A.M.; Koorts, H. Adoption, implementation and sustainability of school-based physical activity and sedentary behaviour interventions in real-world settings: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadaczynski, K.; Paulus, P.; Nieskens, B.; Hundeloh, H. Gesundheit im Kontext von Bildung und Erziehung—Entwicklung, Umsetzung und Herausforderungen der schulischen Gesundheitsförderung in Deutschland. Z. Bild. 2015, 5, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, N.; Elton, B.; Babic, M.; McCarthy, N.; Sutherland, R.; Presseau, J.; Seward, K.; Hodder, R.; Booth, D.; Yoong, S.L. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of physical activity policies in schools: A systematic review. Prev. Med. 2018, 107, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottmann, L.; Küpper, D.; Pack, R.-P. Bewegungsfreudige Schule: Schulentwicklung Bewegt Gestalten—Grundlagen, Anregungen, Hilfen; Bertelsmann: Gütersloh, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hirvensalo, M.; Lintunen, T. Life-course perspective for physical activity and sports participation. Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umberson, D.; Crosnoe, R.; Reczek, C. Social Relationships and Health Behavior Across Life Course. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2010, 36, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, J.V.; Sera, F.; Cummins, S.; Flouri, E. Associations between objectively measured physical activity and later mental health outcomes in children: Findings from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2018, 72, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiner, M.; Niermann, C.; Jekauc, D.; Woll, A. Long-term health benefits of physical activity—A systematic review of longitudinal studies. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega, F.B.; Ruiz, J.R.; Castillo, M.J.; Sjöström, M. Physical fitness in childhood and adolescence: A powerful marker of health. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poitras, V.J.; Gray, C.E.; Borghese, M.M.; Carson, V.; Chaput, J.-P.; Janssen, I.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Pate, R.R.; Connor Gorber, S.; Kho, M.E.; et al. Systematic review of the relationships between objectively measured physical activity and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, 197–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, J.R.; Ortega, F.B.; Martínez-Gómez, D.; Labayen, I.; Moreno, L.A.; de Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Manios, Y.; Gonzalez-Gross, M.; Mauro, B.; Molnar, D.; et al. Objectively measured physical activity and sedentary time in European adolescents: The HELENA study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 174, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, I.; LeBlanc, A.G. Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, E.M.; Corcoran, P.; O’Regan, G.; Keeley, H.; Cannon, M.; Carli, V.; Wasserman, C.; Hadlaczky, G.; Sarchiapone, M.; Apter, A.; et al. Physical activity in European adolescents and associations with anxiety, depression and well-being. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 26, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubans, D.; Richards, J.; Hillman, C.; Faulkner, G.; Beauchamp, M.; Nilsson, M.; Kelly, P.; Smith, J.; Raine, L.; Biddle, S. Physical Activity for Cognitive and Mental Health in Youth: A Systematic Review of Mechanisms. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20161642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunsch, K.; Nigg, C.; Niessner, C.; Schmidt, S.C.E.; Oriwol, D.; Hanssen-Doose, A.; Burchartz, A.; Eichsteller, A.; Kolb, S.; Worth, A.; et al. The Impact of COVID-19 on the Interrelation of Physical Activity, Screen Time and Health-Related Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents in Germany: Results of the Motorik-Modul Study. Children 2021, 8, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braksiek, M.; Lindemann, U.; Pahmeier, I. Physical Activity and Stress of Children and Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Germany—A Cross-Sectional Study in Rural Areas. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuer, C.; Bailey, R. The active school concept. In Physical Activity and Sport during the First Ten Years of Life; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 173–187. ISBN 9780429352645. [Google Scholar]

- Love, R.; Adams, J.; van Sluijs, E.M.F. Are school-based physical activity interventions effective and equitable? A meta-analysis of cluster randomized controlled trials with accelerometer-assessed activity. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 859–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriemler, S.; Meyer, U.; Martin, E.; van Sluijs, E.M.F.; Andersen, L.B.; Martin, B.W. Effect of school-based interventions on physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents: A review of reviews and systematic update. Br. J. Sport. Med. 2011, 45, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.; Murtagh, E.M. Effect of active lessons on physical activity, academic, and health outcomes: A systematic review. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2017, 88, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozuelo-Carrascosa, D.P.; García-Hermoso, A.; Álvarez-Bueno, C.; Sánchez-López, M.; Martinez-Vizcaino, V. Effectiveness of school-based physical activity programmes on cardiorespiratory fitness in children: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br. J. Sport. Med. 2018, 52, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmon, J.; Mazzoli, E.; Lander, N.; Ayala, A.M.C.; Sherar, L.; Ridgers, N.D. Classroom-Based Physical Activity Interventions. In The Routledge Handbook of Youth Physical Activity; Brusseau, T.A., Fairclough, S., Lubans, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 523–540. ISBN 9781000050707. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, E.; van Steen, T.; Direito, A.; Stamatakis, E. Physically active lessons in schools and their impact on physical activity, educational, health and cognition outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sport. Med. 2020, 54, 826–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavilidi, M.F.; Drew, R.; Morgan, P.J.; Lubans, D.R.; Schmidt, M.; Riley, N. Effects of different types of classroom physical activity breaks on children’s on-task behaviour, academic achievement and cognition. Acta Paediatr. 2020, 109, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnelly, J.E.; Lambourne, K. Classroom-based physical activity, cognition, and academic achievement. Prev. Med. 2011, 52, S36–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vazou, S.; Gavrilou, P.; Mamalaki, E.; Papanastasiou, A.; Sioumala, N. Does integrating physical activity in the elementary school classroom influence academic motivation? Int. J. Sport Exe. Psychol. 2012, 10, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erwin, H.; Fedewa, A.; Beighle, A.; Ahn, S. A Quantitative Review of Physical Activity, Health, and Learning Outcomes Associated With Classroom-Based Physical Activity Interventions. J. Appl. Sch. Psychol. 2012, 28, 14–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, P.-J.; Nettlefold, L.; Race, D.; Hoy, C.; Ashe, M.C.; Wharf Higgins, J.; McKay, H.A. Implementation of school based physical activity interventions: A systematic review. Prev. Med. 2015, 72, 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, R.; Blümel, M.; Knieps, F.; Bärnighausen, T. Statutory health insurance in Germany: A health system shaped by 135 years of solidarity, self-governance, and competition. Lancet 2017, 390, 882–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Ministry of Health. Health Insurance Contributions. Available online: https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/beitraege.html (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Gesetz zur Stärkung der Gesundheitsförderung und der Prävention (Präventionsgesetz) [Prevention Act]. Available online: http://www.bgbl.de/xaver/bgbl/start.xav?startbk=Bundesanzeiger_BGBl&jumpTo=bgbl115s1368.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Gerlinger, T. Präventionsgesetz. Available online: https://leitbegriffe.bzga.de/alphabetisches-verzeichnis/praeventionsgesetz/ (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Leitfaden Prävention. Available online: https://www.gkv-spitzenverband.de/media/dokumente/krankenversicherung_1/praevention__selbsthilfe__beratung/praevention/praevention_leitfaden/2021_Leitfaden_Pravention_komplett_P210177_barrierefrei3.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Geene, R.; Reese, M. Handbuch Präventionsgesetz: Neuregelungen der Gesundheitsförderung; Mabuse-Verlag: Frankfurt, Germany, 2017; ISBN 9783863213763. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, M.; Neumann, M.; Dumont, H. Recent developments in school tracking practices in Germany: An overview and outlook on future trends. Orb. Sch. 2017, 10, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, J.J.W. Barriers to Inclusion: Special Education in the United States and Germany; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 9781315635880. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education NRW. Quality Table NRW. Available online: https://www.schulministerium.nrw/system/files/media/document/file/qualitaetstableau_nrw_hinweise_und_erlaeuterungen.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Rossi, P.H.; Lipsey, M.W.; Henry, G.T. Evaluation: A Systematic Approach; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: A pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1·6 million participants. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altgeld, T.; Kolip, P. Konzepte und Strategien der Gesundheitsförderung. In Lehrbuch Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung, 3rd ed.; Hurrelmann, K., Klotz, T., Haisch, J., Eds.; Huber: Bern, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Brusseau, T.A.; Burns, R.D. Introduction to Multicomponent School-Based Physical Activity Programs. In The Routledge Handbook of Youth Physical Activity; Brusseau, T.A., Fairclough, S., Lubans, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 557–576. ISBN 9781000050707. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education NRW. Statistik Telegram 2017/18. Available online: https://www.schulministerium.nrw/sites/default/files/documents/StatTelegramm2017.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Mayers, A. Introduction to Statistics and Spss in Psychology; Pearson: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-0273731016. [Google Scholar]

- Ridgers, N.; Parrish, A.-M.; Salmon, J.; Timperio, A. School recess phyiscal activity interventions. In The Routledge Handbook of Youth Physical Activity; Brusseau, T.A., Fairclough, S., Lubans, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 504–522. ISBN 9781000050707. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Pérez, E.; Ostrosky-Solís, F. Attention and memory evaluation across the life span: Heterogeneous effects of age and education. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2006, 28, 477–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varma, V.R.; Dey, D.; Leroux, A.; Di, J.; Urbanek, J.; Xiao, L.; Zipunnikov, V. Re-evaluating the effect of age on physical activity over the lifespan. Prev. Med. 2017, 101, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Einsiedler, W.; Götz, M.; Heinzel, F. Handbuch Grundschulpädagogik und Grundschuldidaktik; UTB: Stuttgart, Germany, 2011; ISBN 9783825284442. [Google Scholar]

- Masini, A.; Marini, S.; Gori, D.; Leoni, E.; Rochira, A.; Dallolio, L. Evaluation of school-based interventions of active breaks in primary schools: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2020, 23, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedderich, I.; Biewer, G.; Hollenweger, J.; Markowetz, R. Handbuch Inklusion und Sonderpädagogik; UTB: Stuttgart, Germany, 2015; ISBN 9783825286439. [Google Scholar]

- AOK Rheinland/Hamburg. Active at School. Available online: https://www.fitdurchdieschule.de (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Lindemann, U. The “Fitness at School” initiative as a contribution to promoting health and physical activity at schools. Playground@landscape 2019, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann, U.; Pahmeier, I.; Braksiek, M. Gesundheits- und Bewegungsförderung als Beitrag zum Qualitätsmanagement von Schulen. In Interdisziplinäre Forschung und Gesundheitsförderung in Lebenswelten: Bewegung Fördern, Vernetzen, Nachhaltig Gestalten; Wollesen, B., Meixner, C., Gräf, J., Pahmeier, I., Vogt, L., Woll, A., Eds.; Feldhaus Edition Czwalina: Hamburg, Germany, 2020; pp. 17–28. ISBN 3880206899. [Google Scholar]

- Steinmann, I.; Strietholt, R. Student achievement and educational inequality in half- and all-day schools: Evidence from Germany. Int. J. Res. Ext. Educ. 2019, 6, 175–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.S.; Weiss, B. Sustainability of teacher implementation of school-based mental health programs. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2005, 33, 665–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschesnes, M.; Martin, C.; Hill, A.J. Comprehensive approaches to school health promotion: How to achieve broader implementation? Health Promot. Int. 2003, 18, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rütten, A.; Frahsa, A.; Abel, T.; Bergmann, M.; de Leeuw, E.; Hunter, D.; Jansen, M.; King, A.; Potvin, L. Co-producing active lifestyles as whole-system-approach: Theory, intervention and knowledge-to-action implications. Health Promot. Int. 2019, 34, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptack, K.; Strobl, H. Factors influencing the effectiveness of a Cooperative Planning approach in the school setting. Health Promot. Int. 2021, 36, ii16–ii25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourdan, D.; Samdal, O.; Diagne, F.; Carvalho, G.S. The future of health promotion in schools goes through the strengthening of teacher training at a global level. Promot. Educ. 2008, 15, 36–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quy, V.K.; van Hau, N.; van Anh, D.; Le Ngoc, A. Smart healthcare IoT applications based on fog computing: Architecture, applications and challenges. Complex Intell. Syst. 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jekauc, D.; Reimers, A.K.; Wagner, M.O.; Woll, A. Physical activity in sports clubs of children and adolescents in Germany: Results from a nationwide representative survey. J. Public Health 2013, 21, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Züchner, I.; Fischer, N. Kompensatorische Wirkungen von Ganztagsschulen—Ist die Ganztagsschule ein Instrument zur Entkopplung des Zusammenhangs von sozialer Herkunft und Bildungserfolg? Z. Erzieh. 2014, 17, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budde, H.; Voelcker-Rehage, C.; Pietrabyk-Kendziorra, S.; Ribeiro, P.; Tidow, G. Acute coordinative exercise improves attentional performance in adolescents. Neurosci. Lett. 2008, 441, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018-2030: More Active People for a Healthier World; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).