Abstract

Botswana’s new national climate-adaptation plan framework acknowledges the fundamental challenges climate change is posing to household resilience. While the plan aims to be gender-responsive, there is limited empirical data on the current gender dynamics around household-level climate-adaptive priorities and practices. This study aims to understand the gendered variations of how people understand resilience to climate change in both rural and a periurban areas. The authors then consider how these views are reflected in current climate-adaptation policies and responses. A household-level baseline survey with 141 participants was conducted in Ramotswa and Xhumaga, using participant-coded narratives to understand how people understand resilience to climate change. This study found that planning for the shocks and stressors of climate change is gendered, and these variations have important implications for how equity should be reflected in a policy response.

1. Introduction

While the gendered dimensions of climate change are well-established [1,2], policy-makers have not always had contextually relevant, rigorous evaluations at their disposal to inform, in a localized way, what the gendered dimensions of climate change are, and what policy responses are needed to support equitable adaptation [3,4]. Our research has found that women are not only experiencing the effects of climate change differently to men but also making decisions around adaptive practices differently. Understanding these differences is critical for shaping a coherent, inclusive policy around adaptation.

This article draws on a household baseline study on household-level resilience to climate change from two communities, Xhumaga, a rural community in the central district of Botswana, and Ramotswa, a periurban area in the southeast district, which explores current adaptive practices, the ways in which these are gendered, and processes of decision-making and planning in response to climate change. The result will be a better understanding of the current drivers of decision-making, as well as the enablers and constraints to equitable adaptation in Botswana and the identification of certain policy opportunities that could support this.

Climate change and its associated negative impacts is a threat to the socioeconomic livelihoods of millions of people globally [5,6]. The developing world is the most likely to feel the exacerbated negative impacts associated with climate change and variability due to their socioeconomic livelihoods’ strong dependency on natural resources and rain-fed agriculture [7,8]. Developing countries also have relatively fewer institutional supports to adapt to climate change, making them more vulnerable to these changes than other parts of the world [9].

The most vulnerable populations in Botswana are concentrated in rural areas, where livelihoods are mainly dependent on rain-fed agriculture and other activities related to farming and natural resource management [10,11]. This economic system exposes these populations to climatic shocks and stressors. The projected severity of anticipated change in climate conditions and their expected negative impacts on agricultural productivity have prompted governments to formulate adaptation strategies to foster resilience within households to the inevitable impacts of climate change [12,13].

To show commitment to protecting its citizens from adverse climate shifts, Botswana has been a signatory and party to many international conventions. Although having ratified protocols such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Kyoto Protocol, Botswana initially did not have a dedicated policy to respond to climate change. This is reiterated by Crawford [14], who highlights that the Botswanan government does not consider climate change a national priority, and this is reflected in a lack of guiding policy, legislation, and strategy towards responding to the impacts of climate change, as well as a dearth of adaptation projects within the country, which only exacerbates existing and expected climate-related threats. This is consistent with regional trends, which are aligned with both a developmental need to focus public sector attention on service provision and social protection, as well as capacity limitations in areas such as climate adaptation, which require both scientific leadership and multidisciplinary collaboration [15].

Despite constraints to a proactive climate-adaptation response, the government of Botswana did acknowledge the potential for future climate, and its associated environmental, threats in its National Development Plan [16]. Despite these intentions, many of the government’s policies remain outdated, and need reviews to, as a minimum, acknowledge climate change as a threat from both developmental and socio-economic standpoints [14]. For instance, the Botswana national agriculture policy which was developed and adopted in 1991 did not mention or address issues of climate change or adaptation. Agriculture in Botswana, which is primarily of a subsistence nature and relies on specific patterns of rainfall and water flow throughout the Okavango Delta, is particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change. While the government acknowledges traditional farming as the most dominant in terms of numbers of people involved and geographical coverage, there remain significant gaps in the ways in which the national policy environment addresses the vulnerabilities of traditional farmers to climate change [16].

The government has faced several challenges in integrating climate adaptation into its planning, and one of them is the uneven landscape of climate-adaptation-related evidence that is relevant to the Botswanan context [17]. While both historical and predictive meteorological data is widely available [18], there is less rigorous, multidisciplinary research that systematically considers localized adaptive practices. While there are many excellent pieces of research that look at a component of this, much of the evidence is limited sectorally, geographically, or both [19].

Efforts are currently underway in Botswana to bridge the gap existing in the formulation and review of policy structures aimed at building resilience to climate change, particularly for traditional farmers and households relying on rain-fed agriculture for their livelihoods [20]. Through various stakeholders and key sectoral players such as officers from government departments, ministries, NGOs, and the private sector, who make up the National Council on climate change, several strides have been made in championing meaningful national climate-adaptation policies. These are now encapsulated in the National Action Plan [16]. Climate change issues are now addressed in a combination of different policy areas, with a common focus on resilience and sustainable growth [20,21]. Climate change has also been increasingly integrated into the national sectorial policies such as the National Health Plan [22]. The latest policy brief from the Ministry of Agriculture also acknowledges the challenges of climate change and the need for more robust adaptation and mitigation plans to be put in place in order to cushion the people’s livelihoods from the adverse impacts of climate change [23].

Botswana has since drafted a policy directed at addressing issues of climate change, the Botswana Climate Change Response Policy [16]. This policy document’s main aim is to bring sustainability and climate change resilience issues into the mainstream policy discourse, addressing development planning with the intention of enhancing Botswana’s resilience and capacity to respond to existing and projected climate change impacts [24]. Furthermore, the policy outlines Botswana’s commitment to maintaining low-carbon development pathways and ways that will tackle socio-economic issues, while simultaneously protecting the environment. While issues of gender are considered in the framing of the policy, when it comes to the mechanisms of the implementation of climate change adaptation interventions, there is little targeted consideration. This poses a risk to implementation, as successful adaptation will require a gender-responsive approach in both short- and long-term national policy processes [25,26,27].

In addition to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the promotion and encouragement of gender equality and empowerment in sectors such as agriculture is taken as a priority. As a result, countries have endeavoured and strategized to have more gender-balanced and gender-inclusive policy documents to bridge the gender gap identified in addressing climate change adaptation plans. Despite the efforts made to date, more work is needed in order to reduce this gap. Botswana has developed its new national adaptation plan framework in line with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) guidelines, and this framework demonstrates the fundamental challenges that climate change is posing to national development and highlights how critical a policy response is [16]. While the plan aims to be gender-responsive, there is a lack of rigorous research on the current gender dynamics around household-level climate-adaptive decision-making.

With the increased focus on adaptation in the climate change policy debate, the uneven distribution of impacts and vulnerability between regions and among social groups becomes increasingly important [28]. Evidence points to a frequent lack of attention given to gender aspects during the initial phases of climate change policy processes [29]. While the gender–climate nexus is richly theorized [30], engaging with conceptual debates around gender is largely outside the scope of this paper. However, what is important for the purposes of this discussion is understanding gender as an intersectional vulnerability to climate change. From a policy-planning perspective, this suggests that consideration should be given to both processes and outputs in order to better understand the needs of multiple vulnerable groups. Due to limitations on the data available, this study has somewhat reductionist limitations of speaking to binary genders and is not able to contribute to discussions around gender diversity or other intersections of identity and exclusion. However, many of the findings and recommendations have the potential to be extrapolated to other vulnerable groups.

In many contexts, men and women respond differently to challenges associated with climate change due to social processes such as inheritance rules, land tenure systems, and a lack of support from formal institutions [26,31,32]. Various studies have shown that men and women farmers not only have different abilities to adapt to climate change, variability, and weather-related shocks, they also have different incentives and drivers of decision-making in processes of adaptation [33]. In many cases, women, acknowledging the intersectionality of multiple vulnerabilities, are affected more than men by climate-related shocks and stresses [34,35]. For instance, Wrigley-Asante et al. [26] in a comparative study on gender dimensions of climate change amongst small-holder crop farmers in Ghana established an indication of gendered adaptation to agriculture, despite the use of similar on-farm agronomic practices. Further research has validated this finding. Mearns and Norton [31] argue that, because women are sometimes not part of the household and community decision-making processes that affect their lives, they are often excluded and underrepresented in decision-making and policy processes regarding climate change. These coinciding factors strongly suggest that issues of gender need to be mainstreamed across the entire multisectoral climate-adaptation policy cycle including planning, focused implementation, sustainable financing mechanisms, capacity building, institutional coordination, and measurement of outcomes [36,37].

This baseline project aimed to better understand how communities across Southern Africa understand resilience to climate change and how they define household-level adaptation. Data were gathered in Ramotswa, a periurban area near Gaborone, and Xhumaga, a rural village in northern Botswana. One rural and one periurban site were chosen deliberately, to identify contextual differences in adaptation planning and practice. While the study does not intend to generalize across all rural and urban areas, the aim was to ensure a wide scope of livelihoods and adaptive capacity would be included. This article draws specifically on the data gathered in Botswana to better inform national policy-making, given Botswana’s regional importance around climate adaptation and in particular its hosting role of the Southern African Development Community (SADC), as well as the ecological sensitivity of the Okavango Delta region.

2. Methods and Context

The research took a participant-coded micronarrative approach [38]. This means that participants were invited to share stories about specific experiences related to the objectives of the study; for example, times when they had been affected by climate shocks or stressors or plans that they had in place to adapt to climate change. Once they provided these brief narratives, they were asked questions about their own storytelling, allowing them to do their own coding of the inputs, in a triad format, as explained below. This allowed for both detailed qualitative data around how participants were responding to climate shocks and stressors, but also allowed the participants themselves to analyse these across a range of different metrics. This method was chosen to allow participants to reflect on their own experiences, while at the same time comparing the responses of a large volume of qualitative data and allowing the research team to validate their analysis of responses received. Data was collected as part of a baseline on climate resilience across Southern Africa, but due to adaptation policies being formulated and implemented at a national level, this article deals specifically with data from the two sites in Botswana.

Both communities were affected differently by climate change, with Xhumaga being located in an elephant corridor, and many concerns were linked to increases in human–wildlife conflict. Ramotswa, as a periurban area, had more participants who are in formal employment and are less reliant on subsistence agriculture, but who were still negatively affected by irregular access to water. In both communities, the gendered dimension of climate adaptation emerged as a central theme, with policy gaps being explicitly identified by research participants.

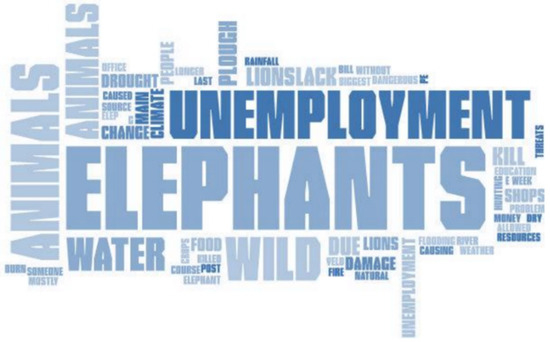

Xhumaga has a total population of about 1500. It is located at a border of Makgadikgadi National Park, which has an estimated elephant population of about 1800, often considered above the carrying capacity of the area, but in keeping with the government’s policy decisions around hunting and conservation [39,40,41]. While significant effort has gone into reducing human–wildlife conflict in the area, at the time the fieldwork was undertaken a number of things contributed to an increase in tensions. This included the destruction of the fence between the national park and the village, and an ongoing drought that dried the seasonal river serving as a natural border to the park, further resulting in animals and people using the same water source. A lack of maintenance of an alternative borehole pump meant that there were no alternative water points in the community. Crop destruction by elephants was rampant, and there was more than one reported case of people being trampled. While only indicative, the word cloud in Figure 1 draws on participant descriptions of the livelihood challenges they faced due to climate change.

Figure 1.

Xhumaga participants’ descriptions of their livelihood challenges. Source: Authors’ own work, developed on Word.

Being a rural agrarian community, gender norms were strictly articulated, but not necessarily strictly enforced. Illustrating the feminization of poverty from a range of perspectives, many households in the community were woman-headed, with wage-seeking migration being reported as more common among men, which provided concomitant flexibility in gender roles. While there is no localized data to verify this, it would be largely in keeping with regional trends [42]. Fetching water for household use is primarily considered women’s labour, making women particularly vulnerable to the shifts in human–wildlife conflict. Overall, households in the community had little capital available for climate-adaptive planning, which reflected decision-making strategies.

Ramotswa, on the other hand, is a periurban area near Gaborone, with a population of about 25,000. As compared to Xhumaga, many households had members who were formally employed, and, while most households still engaged in various forms of subsistence agriculture, there was considerably more economic diversification. Rather than relying on farming for all of the household’s caloric and income needs, agriculture was more likely to supplement household nutrition and income. The community was affected by climate change, with droughts and flooding negatively impacting households, but the capacity of households to both withstand shocks and also invest in adaptive planning was significantly greater than in Xhumaga.

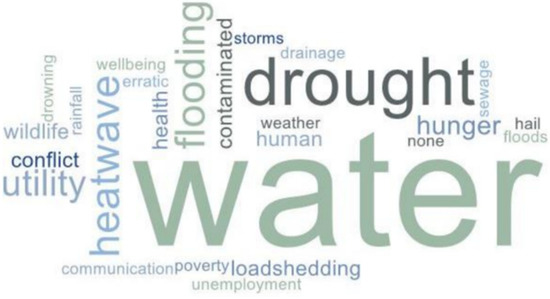

Water shortages are often faced by the community; while there are taps that provide bulk water provision, these often run dry, and households faced a range of administrative barriers to water access, such as inefficient billing systems, insufficient infrastructure maintenance, and frequent outages. The word cloud in Figure 2 reflects the challenges faced by Ramotswa due to climate change, and it illustrates core differences in context to Xhumaga, where human–wildlife conflict is a much more prominent consideration.

Figure 2.

Ramotswa participants’ descriptions of their livelihood challenges. Source: Authors’ own work, developed on Word.

Given these contextual differences, the sections below will look at the research participants, the instruments used, and the ways in which this context was considered in the methods chosen.

2.1. Participants and Process

Participants were chosen by taking satellite images of the settlements, numbering households, and drawing a random sample of households. Thereafter, the first adult available when approaching the household was invited to participate. If they declined (due to other obligations, for example), they were asked if another adult in the household was available to participate. If no adult was available, the next household was approached. Since the research approach was largely qualitative, the intention in the sampling was not to be statistically representative of the entire community but rather to reflect as wide as possible a range of views and include perspectives that may be different based on geographic characteristics, such as proximity to a water source, exposure of the household to wildlife, or distance to fields or grazing land. With that in mind, the sample was quasi-random and included certain anecdotal variations from the sampling strategy. For example, at both sites, certain individuals requested to opt into the study, either because of their interest in the topic or because they had recently been affected by a climate shock or stressor and wished to share their experience. These were 6 participants in total (3 men and 3 women), who were accommodated, because the priority was a richness in data collection and positive and responsive engagement with research participants rather than a rigorous statistical representation.

The research instrument was translated into both Tswana and Humbukushu, with participants having an option of participation in English, Tswana, or Humbukushu. Each site had three data collectors, who were local to the area and spoke Tswana or Humbukushu as either their native language or with fluency. Data were recorded in the original language, and then translated into English for entry into a common repository for storage, coding, and comparison across sites.

There were 141 participants from randomly selected households across both sites in total, with 85 from Xhumaga and 56 from Ramotswa. This represented approximately half of the households in Xhumaga, while in Ramotswa it was only 5%, but all neighbourhoods were represented in the sample. As Table 1 illustrates, 67% of the participants were women, with a higher percentage of female participants in Xhumaga, reflecting the demographic differences expected between urban and rural areas.

Table 1.

Breakdown of research participants by gender and age.

Table 1 presents the breakdown of participants in this study by age and gender. While there will not be a statistical analysis of this breakdown, it is important to have an indicative sense of the study’s participants.

Once the data collection and analysis were completed, site reports were drafted that profiled each individual community participating in the study. These were translated as appropriate and presented to community leaders in an open meeting, as a way of allowing participants to receive feedback on the finding of the study. This also served to validate some findings and raise any issues around the context of resilience at each site, strengthening the final analysis reflected in this article.

2.2. Instrument

The research instrument was designed in four sections to help the research team better understand three key dimensions of resilience to climate change: the absorptive, adaptive, and anticipatory capacity of households. Each section begins with an open question that prompts the participant to share a story, and the participant is then invited to reflect on their story by placing a dot on a triad. While this process was explained to all research participants, some were eager to place the dot themselves, and all were invited to do so, but researchers offered to do this on their behalf according to verbal instructions, if they were uncomfortable with tablets or unfamiliar with visual mapping generally.

The illustration in Figure 3 below shows the interactive mapping tool, which allowed each participant to locate their responses either at one of the labelled corners of the triad, or anywhere in the middle. Triads will then be presented that can colour- or pattern-code responses based on gender, age, location, or other characteristics for visual analysis.

Figure 3.

Screenshot of interactive mapping tool. Source: Authors’ commissioned software development for the purposes of the study; data collection software is held under a creative commons license.

After completing the triad process to reflect on the stories participants told, they were asked a few closed ended survey questions, which included demographic information as well as specific responses around climate shocks and stressors, and the response within their household. As a result, the data gathered by this research instrument is not meant to represent the population of the sites studied but rather to suggest indicative trends and support in the interpretation of qualitative data. The results section below will explore in more detail the ways in which members of both communities have responded to these challenges and discuss the implications this has for climate-adaptive policies.

3. Results

The study found several key differences in the ways climate adaptation is taking place across the different sites of study, as well as differences in the ways men and women are articulating the challenges of climate adaptation within their households. The section below outlines, first, the differences in climate adaptation mentioned across the different sites; next, the gendered differences in the way climate change is experienced within households; and, finally, differences in the way decisions are made around climate adaptation. By explaining these factors in more detail, policy-makers will be better equipped to respond in a way that fully considers gender in their responses.

In describing the effects of climate change on their households, men were more concerned with the economic effects of climate impacts, such as reduced income from agriculture, while women were more likely to be concerned with barriers to accessing water, and the implications of this on well-being. This is consistent with trends in the gendered division of labour. When it came to differences in decision-making, women were often more likely to rely on other people in their community for information and support, while men were more likely to engage with institutions and government structures. This could be in part explained by a difference in anticipation among participants that the government would assist them, with men more confident than women in their ability to access institutional support.

3.1. Defining the Household-Level Effects of Climate Change

There were core differences between sites in the household-level effects of climate change. In Ramotswa, key concerns across all participants were around the administration of the water supply, including issues of billing and provision. In Xhumaga, the water-supply concerns were different. Participants worried about the administrative structures through which boreholes could be sourced, but this was a relatively minor problem when compared to human–wildlife conflict and water scarcity.

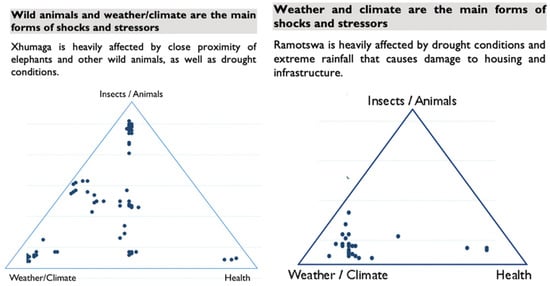

As the triads in Figure 4 demonstrate, climate is one of the biggest causes of stress in households in Ramotswa, while in Xhumaga conflicts with wild animals, which are compounded by climate, are both key causes of household stress.

Figure 4.

Primary shocks and stressors that households face in Xhumaga and Ramotswa. Source: Authors’ own work, based on data extracted on STATA.

3.2. Barriers to Accessing Water

Women in both Ramotswa and Xhumaga articulated unique challenges in accessing water. In Xhumaga, access problems were, firstly, about the scarcity of water points and, secondly, about the dangers of wildlife that shared them. In Ramotswa, the barriers to water access were primarily administrative, but they were still significant. Women at both sites were more likely to mention concerns about temporality affecting their access to water. In Ramotswa, the concerns were about the time required to deal with rectifying problems in the billing systems and related expenses, such as cell phone costs to report problems or travel expenses to go to government offices to resolve the issues. In Xhumaga, the temporal concern was both around the distance of the water points and the need to consider the movements of wildlife during their water-collection work. Water was inaccessible at dusk and dawn, when elephants often passed through the access points. However, those were often the times where households had a greater need for water, and women were freer from other domestic responsibilities. Both sites often experienced water outages.

“We spend long periods of time without water but water bills are always high”Response, Man, 41

When reflecting on the challenges demonstrated around accessing water, there were significantly gendered differences in the approaches people took to resolving their situation. There are a number of ways that government institutions are mandated and able to resolve issues of water access, whether it is through infrastructure provision or maintenance, billing systems, water tankers, or other means. Women were generally unwilling to approach government institutions for support in resolving their challenges in access to water, while this hesitancy was not shared by men. Across both sites combined, 38% of women reported that they could get help from the government if they tried to access it, whereas 55.5% of men reported confidence that the government would provide assistance if required. This significant difference reflects a stark contrast in the way individuals link to public-sector institutions, and emphasizes the need for planning around how to build trust and participation with vulnerable communities.

3.3. Water Quality and Variability

Research participants across both sites expressed concerns about water quality, although, again, this had a gendered dimension. Men were more concerned about the contamination of water for agricultural and livestock purposes. They also emphasized the cost associated with either accessing clean water or purifying the available water. Women, on the other hand, were more likely to link poor water quality to challenges in domestic use, such as health issues in children.

“Our water is highly contaminated making it unsuitable for arable agriculture and livestock rearing”Participant, Man, 44

Another participant observed:

“The water used to be clean. But now, you can see diarrhoea is more common. Years ago, our children were not bothered, but now you find they are missing a lot of school due to sickness”Participant, Woman, 18

The Ramotswa area faces a range of challenges in water quality, due to a large aquifer that underlies the area combined with varied sanitation infrastructure [43]. Participants in the research were generally aware of the deterioration in ground water quality that they had been facing recently, with nearly a quarter citing concerns of water quality as an ongoing issue.

All participants, regardless of gender, emphasized the difficulties caused by variable rainfall. While both men and women from both sites pointed to the poor agricultural results that came from intermittent droughts and flooding, so the gendered dimension of rain-fed agriculture was particularly evident. Men were more likely to either have access to physical infrastructure that would mitigate against the variable rainfall (for example, irrigation systems), and women were more likely to depend on rain-fed crops for their household’s food security. While most respondents linked the difficulties of subsistence farming to variable rainfall, others drew causal linkages to other aspects of climate change, such as heat making certain seed varieties less suitable, or the increase in certain pests.

“Excessive heat makes it difficult for plant growth. We used to have plenty of vegetables”Participant, Woman, 9

Yet another participant pointed to some of the results of these changes:

“With the drought we are experiencing, elephants come more frequently to the village. There is no food in the park, so they destroy our fields”Participant, Woman, 41

Some participants also spoke about their own responses to the changes:

“We have a problem with runoff in our fields. When the rain is too heavy, it will sit in the field, and our crops will rot. We have dug channels for drainage, but this year there wasn’t enough rain, so we don’t know if it will work”Participant, Man, 22

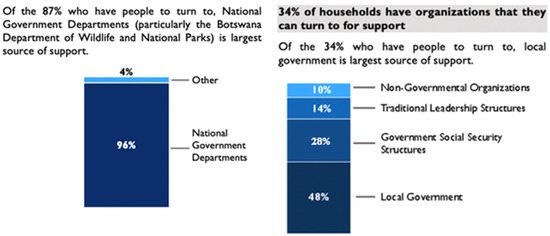

While the challenges faced by farmers are common, they are clearly experienced along gendered lines. Additionally, the sources of help participants cite as available varies by gender. Across both sites, women were far more likely to seek help from individuals, while men were more likely to find support from organizations. One of the most striking differences between the two sites is the role the government plays in supporting households that are facing shocks and stressors. Only a third of households in Ramotswa could turn to some kind of organization for support, and, of those, fewer than half would approach local government. In Xhumaga, on the other hand, 87% of households could find support from organizations, and 96% of these turned to national government departments. This is undoubtedly explained by the community’s reliance on the department of wildlife to resolve issues of livestock predation and human–wildlife conflict, which does not pose as significant a problem in Ramotswa. It also points to the scarcity of other institutions providing social support in rural areas.

Figure 5 illustrates the clear differences in sources of support between the communities of Ramotswa, on the left, and Xhumaga, on the right, which, as mentioned above, also illustrates the differences in the problems faced by both communities.

Figure 5.

Sources of support in times of crisis. Source: authors’ own work, based on responses received.

Particularly concerning is the overwhelming centrality of government departments as sources of institutional support and the gendered variation in access. Women are nearly half as likely to report turning to a department for support as men, meaning that women in this rural area lack support from organizations.

3.4. Decision-Making Strategies around Climate Adaptation

Our research considered the different ways people plan around climate adaptation. There seem to be variations along gender lines in the ways in which household heads and members take adaptive steps. For example, men in our sample were more concerned about the economic impact of variable rainfall, while women were more concerned about barriers to accessing water for domestic use and the household implications of such poor access.

For example, certain farming practices and natural ‘signals’ around the climate are linked to cultural beliefs, which women have expressed a priority around propagating. Some participants highlighted this as valuable, even at an economic cost.

“Since the drought began, we haven’t really harvested. But every year we plant, because my children must see how to prepare the fields”Participant, Woman, 32

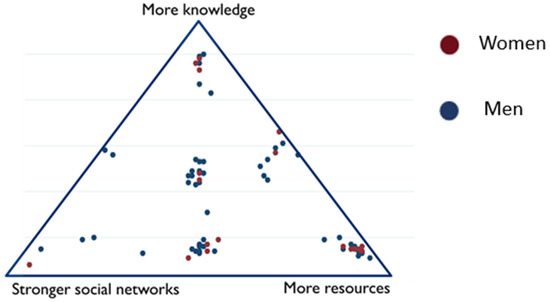

Figure 6 shows that men prioritize the tangible support of resources in adapting to climate change, while women are more likely to value knowledge and social networks. This may influence the policy guidance for household-level support to adaptation efforts.

Figure 6.

Requirements for better planning to adapt to climate change. Source: Authors’ own work.

Due to the gendering of household divisions of labour, certain changes had a disproportionate effect on women. Sometimes this effect is direct. For example, with women being primarily responsible for fetching water, both the scarcity of water and human–wildlife conflict around water has a disproportionate effect on women. However, sometimes the results have been less linear. For example, with elephants more frequently entering human settlements in Xhumaga, it was no longer considered safe to plant a vegetable garden in a household compound, since this would attract elephants. It meant that either women had to forego the income they could make from selling surplus vegetables, or alternatively had to take additional security risks and forgo time to work within the house and travel to fields that are a greater distance from their compounds to plant vegetables.

4. Discussion

For Botswana’s adaptation policy to be successful, it needs to be fully gender-responsive. This means not only considering the impact of the planned institutional responses on men and women but also deepening our understanding of current adaptive practices and decision-making processes, to better understand what inclusive policy support will look like. The results above indicate that household-level adaptation to climate change varies along rural and periurban lines, but that in both communities there are gendered differences in the ways in which climate-related challenges are experienced and understood and then in the related decision-making processes. Furthermore, in making decisions around taking adaptive steps to address the issue, men and women leverage different social and institutional connections.

As presented in Section 3.2, men are more likely than women to seek the support of institutions and organizations when they are faced with a shock or stressor. Additionally, it is apparent from the above results that women face different barriers to men in accessing services offered by the government, including a regular, quality water supply. Further research may be needed to explore whether this is due to a lack of information or awareness, technical barriers such as a lack of transport, or other forms of exclusion. However, this is broadly in line with Mearns and Norton’s [31] argument that women may not be well-integrated into organizational decision-making around a climate response. However, it is important to note that women are equally likely to seek help, although they do this through informal networks of friends or family. This suggests that there may be opportunities to make formal institutional responses more accessible to women through appropriate outreach.

Additionally, it is clear that gendered differences in the allocations of household labour mean that changes in water availability and quality affect women and men differently. As posited by Goh [34] and Perez et al. [33] and supported by our data, this could be due to the increase in household labour as a result of climate change, as well as the fact that women carry much of a household’s reproductive labour, which is disproportionately affected by shifts in water-supply quality and availability. This suggests there may be opportunities to integrate reproductive labour and its household-level consequences into climate change policy responses.

Furthermore, it is apparent from the above research results that women and men respond differently to the barriers they face as a result of climate change, such as seeking out additional information from divergent sources. In order for a policy response to be genuinely gender-responsive, there should be dedicated disaggregation of this kind of relevant data by gender, and further research should be done to better understand these differences. For example, dedicated public-sector programming that considers the gendered nature of rain-fed agriculture would contribute significantly to supporting women’s access to the available resources as well as to creating a feedback loop between women who are affected by climate change and those developing the policies that affect them [44].

5. Conclusions

There is a well-established body of research suggesting that men and women are impacted differently by climate change. However, many sub-Saharan countries are particularly affected by climate change, due to the economic importance of rain-fed agriculture in addition to geographic and meteorological characteristics. Furthermore, due to institutional limitations, many are in the process of shaping their climate-adaptation responses. Doing this well requires empirical, gender-disaggregated data that is often not available. This study found that there are three key considerations for Botswana’s climate-adaptation policy response, which are particularly important in ensuring they are inclusive of the needs of women. The first is that access to formal institutions is currently gendered, and for institutional responses to be accessible to women, there is a need for additional outreach. The second is that gendered divisions of household labour mean that the uneven availability of water has different implications for men than women. However, these differ according to context, so more research is needed to understand how an appropriate policy response could support equity. Finally, it is evident that decision-making processes to take adaptive steps around climate change are different for men and women, so a better understanding of this phenomenon in a wider range of geographic and economic contexts could lay the necessary foundation for a contextually appropriate policy response.

Author Contributions

K.M. carried out data collection and curation as well as original draft preparation; L.M. contributed to data collection and curation, analysis, and original draft preparation; M.M. contributed to data collection and curation, analysis, and original draft preparation; C.B.M. was responsible for the conceptualization, methodology, and software as well as review and editing of drafts. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is made possible in part by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), contract number 720-674-18-C-00007. The contents of this research are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States government.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the University of Witwatersrand, protocol code: HRECNMW21/01/07, received 19 January 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study may be available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to restrictions on ethical clearance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Roehr, U. Gender, Climate Change and Adaptation. Introduction to the Gender Dimensions; Both Ends Briefing Paper Series; Academia: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Behrman, J.A.; Bryan, E.; Goh, A.H. Gender, Climate Change, and Group-Based Approaches to Adaptation; International Food Policy Res Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Makadzange, P.F. The Study of Institutionalisation of a National Monitoring and Evaluation System in Zimbabwe and Botswana. Ph.D. Thesis, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, A.; Rosenstock, T. Reflections on Monitoring and Evaluating Climate Adaptation; Learning Session on Climate Change Adaptation Metrics for Smallholder Agriculture; CGIAR: Montpellier, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, M.; Serrao-Neumann, S. Climate Change Effects on People’s Livelihood; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, S.; Bajagain, A. Impacts of Climate Change on Livelihood and Its Adaptation Needs. J. Agric. Environ. 2019, 20, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdeczny, O.; Adams, S.; Baarsch, F.; Coumou, D.; Robinson, A.; Hare, B.; Reinhardt, J. Climate change impacts in Sub-Saharan Africa: From physical changes to their social repercussions. Reg. Environ. Change 2017, 17, 1585–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogomotsi, P.; Sekelemani, A.; Mogomotsi, G. Climate change adaptation strategies of small-scale farmers in Ngamiland East, Botswana. Clim. Change 2020, 159, 441–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, F.; Terwisscha van Scheltinga, C.; Verhagen, J.; Kruijt, B.; van Ierland, E.; Dellink, R.; Kabat, P. Climate Change Impacts on Developing Countries—EU Accountability; Think Tank: Santa Rosa, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Skoufias, E.; Essama-Nssah, B.; Katayama, R. Too Little Too Late: Welfare Impacts of Rainfall Shocks in Rural Indonesia. Bull. Indones. Econ. Stud. 2012, 48, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrandrea, M.; Abdrabo, M.; Adger, W.; Federation, Y.; Anisimov, O.; Arent, D.; Yohe, G. Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability—IPCC WGII AR5 Summary for Policymakers; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Akinnagbe, O.; Irohibe, I. Agricultural adaptation strategies to climate change impacts in Africa: A review. Bangladesh J. Agric. Res. 2015, 39, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. FAO Strategy on Climate Change. 2017. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/financial/2017docs/fao-climate2017.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Crawford, A. Review of Current and Planned Adaptation Action in Botswana; CARIAA Working Paper No. 7; UK Aid: London, UK; Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Filho Leal, W.; Balogun, A.L.; Ayal, D.Y.; Bethurem, E.M.; Murambadoro, M.; Mambo, J.; Mugabe, P. Strengthening climate change adaptation capacity in Africa-case studies from six major African cities and policy implications. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 86, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Botswana. National Adaptation Plan Framework for Botswana. 2020. Available online: https://napglobalnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/napgn-en-2020-nap-framework-for-botswana.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Basupi, L.V.; Quinn, C.H.; Dougill, A.J. Adaptation strategies to environmental and policy change in semi-arid pastoral landscapes: Evidence from Ngamiland, Botswana. J. Arid Environ. 2019, 166, 17–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simelton, E.; Quinn, C.H.; Batisani, N.; Dougill, A.J.; Dyer, J.C.; Fraser, E.D.; Stringer, L.C. Is rainfall really changing? Farmers’ perceptions, meteorological data, and policy implications. Clim. Dev. 2013, 5, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westholm, L.; Ostwald, M. Food production and gender relations in multifunctional landscapes: A literature review. Agroforest Syst. 2020, 94, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanrpan (Producer). Climate-Smart Agriculture in Botswana; [Policy Brief 10/2017]; Fanrpan: Pretoria, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dube, O.P. Impacts of climate change, vulnerability and adaptation options: Exploring the case for Botswana through Southern Africa: A review. Botsw. Notes Rec. 2003, 35, 147–169. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Botswana. National Health Policy: Towards a Healthier Botswana; Government of Botswana: Gaborone, Botswana, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner, B.G.; Mungatana, E.D.; Baleta, H. Impacts of Drought Induced Water Shortages in South Africa: Sector Policy Briefs; Water Research Commission: Pretoria, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Botswana. Draft Climate Change Repsonse Policy. UNDP. 2020. Available online: https://info.undp.org/docs/pdc/Documents/BWA/DRAFT%20CLIMATE%20CHANGE%20RESPONSE%20POLICY%20%20version%202%20(2).doc (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- Paudyal, B.R.; Chanana, N.; Khatri-Chhetri, A.; Sherpa, L.; Kadariya, I.; Aggarwal, P. Gender integration in climate change and agricultural policies: The case of Nepal. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 3, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrigley-Asante, C.; Owusu, K.; Egyir, I.S.; Owiyo, T.M. Gender dimensions of climate change adaptation practices: The experiences of smallholder crop farmers in the transition zone of Ghana. Afr. Geogr. Rev. 2019, 38, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assan, E.; Suvedi, M.; Olabisi, L.S.; Bansah, K.J. Climate change perceptions and challenges to adaptation among smallholder farmers in semi-arid Ghana: A gender analysis. J. Arid. Environ. 2020, 182, 104247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahsen, M.; Sanchez-Rodriguez, R.; Lankao, P.R.; Dube, P.; Leemans, R.; Gaffney, O.; Smith, M.S. Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability to global environmental change: Challenges and pathways for an action-oriented research agenda for middle-income and low-income countries. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2010, 2, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampaire, E.L.; Acosta, M.; Huyer, S.; Kigonya, R.; Muchunguzi, P.; Muna, R.; Jassogne, L. Gender in climate change, agriculture, and natural resource policies: Insights from East Africa. Clim. Chang. 2020, 158, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyana, K.; Lwasa, S.; Kasaija, P. Gender ideologies and climate risk: How is the connection linked to sustainability in an African city?. In Research Anthology on Environmental and Societal Impacts of Climate Change; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 914–929. [Google Scholar]

- Mearns, R.; Norton, A. (Eds.) Social Dimensions of Climate Change: Equity and Vulnerability in a Warming World; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yaro, J.A. The perception of and adaptation to climate variability/change in Ghana by small-scale and commercial farmers. Reg. Environ. Change 2013, 13, 1259–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, C.; Jones, E.M.; Kristjanson, P.; Cramer, L.; Thornton, P.K.; Förch, W.; Barahona, C.A. How resilient are farming households and communities to a changing climate in Africa? A gender-based perspective. Glob. Environ. Change 2015, 34, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, A.H. A Literature Review of the Gender-Differentiated Impacts of Climate Change on Women’s and Men’s Assets and Well-Being in Developing Countries; CAPRi Work; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Quisumbing, A.; Meinzen-Dick, R.S.; Njuki, J. 2019 Annual Trends and Outlook Report: Gender Equality in Rural Africa: From Commitments to Outcomes; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kyazze, F.B.; Owoyesigire, B.; Kristjanson, P.M.; Chaudhury, M. Using a Gender Lens to Explore Farmers’ Adaptation Options in the Face of Climate Change: Results of a Pilot Study in Uganda; CCAFS Working Paper; CCAFS: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kristjanson, P.; Bryan, E.; Bernier, Q.; Twyman, J.; Meinzen-Dick, R.; Kieran, C.; Doss, C. Addressing gender in agricultural research for development in the face of a changing climate: Where are we and where should we be going? Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2017, 15, 482–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Merwe, S.E.; Biggs, R.; Preiser, R.; Cunningham, C.; Snowden, D.J.; O’Brien, K.; Jenal, M.; Vosloo, M.; Blignaut, S.; Goh, Z. Making Sense of Complexity: Using SenseMaker as a Research Tool. Systems 2019, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modise, O.M.; Lekoko, R.N.; Thakadu, O.T.; Mpotokwane, M.A. Toward Sustainable Conservation and Management of Human-wildlife Interactions in the Mmadinare Region of Botswana: Villagers’ Perceptions on Challenges and Prospects. Hum.–Wildl. Interact. 2018, 12, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Redmore, L.E. In the Era of Elephants: Rural Change and Vulnerability in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. Ph.D. Thesis, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, K.E. Elephants for Africa: Male Savannah elephant Loxodonta africana sociality, the Makgadikgadi and resource competition. Int. Zoo Yearb. 2019, 53, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, E. Making a Living: Changing Livelihoods in Rural Africa; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- McGill, B.M.; Altchenko, Y.; Hamilton, S.K.; Kenabatho, P.K.; Sylvester, S.R.; Villholth, K.G. Complex interactions between climate change, sanitation, and groundwater quality: A case study from Ramotswa, Botswana. Hydrogeol. J. 2019, 27, 997–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bangalore, M.R. Shock Waves: Managing the Impacts of Climate Change on Poverty; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).