Abstract

The transition from the industrial economy to the knowledge-based economy has changed the status quo, and consequently, intangibles have gained traction in the scientific discourse of recent decades. The paper aims to scrutinise, econometrically, the nexus between intangibles and firm performance and the moderating role of CEO duality and CEO gender. Capital-intensive industries are largely overlooked by previous studies, which prompted us to explore the electricity and gas industry. The analysis is based on a longitudinal dataset of EU-listed companies and employs a quantitative approach to study the causal relationships between intangibles, firm performance, and CEO characteristics. Results demonstrate that intangible assets are a stepping stone to better financial and market performance, which endorses the resource-based view. Today’s social and cultural milieu sees gender diversity in a positive light. Consonant with the upper echelons theory, the study finds that CEO gender positively impacts the intangibles–firm performance relationship. The hypothesised prejudicial effect of CEO duality, postulated by the agency theory, is only partially supported. Managers and policymakers are advised to pay particular attention to intangibles and science-driven projects to augment corporate performance. Creating a diversity-friendly culture is also of paramount importance.

1. Introduction

The advent of the new economy led progressively to shifting the focus from tangible to intangible assets [1]. The so-called knowledge-based economy, placed under the aphorism “knowledge is power”, has brought changes regarding the source of competitive advantage [2]. The classical factors of production (such as land, machinery, and equipment) have progressively been replaced by elements without physical substance, commonly termed intangibles, or intellectual capital (IC). In this vein, intangible assets have gained traction in the last three decades [3].

To put it in homo economicus terms, corporate investments, regardless of their nature, are objective-driven [4]. Consequently, companies invest in potentially value-enhancing projects and expect that their investment in intangibles brings innovation, new products and, eventually, superior financial performance. Unsurprisingly, a large body of literature has examined the determinants of financial performance and the potential role of intangibles, but the majority of the studies in this realm of research are confined to science-based industries. Motivated by the observations of a recent study [3], pertaining to the scant empirical evidence in capital-intensive industries, this research aims to scrutinise the nexus between intangibles and firm performance in the gas and electricity industry. The lately unprecedented surges in electricity and gas tariffs, against a background of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russo-Ukrainian War, have not only led to a resurgence in academic popularity but also reaffirmed the importance of this industry in the welfare of citizens [5]. This research setting can be considered timely and relevant as energy is the “life blood of all economies and an indispensable prerequisite for all economic activities” [6]. Moreover, several recent studies call for an interdisciplinary approach, aimed at bridging apparently disparate concepts such as IC and sustainability [7,8,9,10], intangibles and sustainable performance [11,12,13] or IC and corporate governance [14,15,16,17,18]. Hence, the characteristics of the chief executive officer (CEO), namely CEO duality and CEO gender, are also brought under the purview of the present study.

At this point, conceptual clarification is needed as intangibles and IC are considered largely synonymous by many scholars [19,20,21,22,23]. In the study at hand, intangible assets are to be understood in the spirit of International Accounting Standard 38 (IAS 38), as “an identifiable non-monetary asset without physical substance. (…) The three critical attributes of an intangible asset are: identifiability, control (power to obtain benefits from the asset), future economic benefits (such as revenues or reduced future costs).” [24]. The accounting treatment of intangibles is applicable mutatis mutandis outside of Europe as well. Intangible assets in the energy and gas industry include but are not limited to: software, technology, patents, research and development (R&D) costs that qualify for capitalisation, drilling rights, assets related to concession contracts, the positive value of energy purchase/sale contracts stated at fair value as part of a business combination governed by IFRS 3, operating or usage rights for power plants, purchased customer contracts and relations, greenhouse gas emission rights, and renewable energy certificates purchased.

The analysis is based on a panel dataset comprising 133 listed companies located in European Union (EU) and spans 10 years (2011–2020). Using a quantitative approach, it is found that intangibles are a stepping stone to better performance in the electricity and gas industry, which endorses the resource-based view (RBV). Results also show that female-led companies manage intangibles wisely, which ultimately translates into better performance. Women are more risk-averse and less prone to opportunism which may account for performance differences between women-led and male-led firms. Concerning the blending of positions (CEO and chairman), the study only offers partial support for the moderating role of CEO duality on intangibles–firm performance relationship.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: the next section provides an overview of the EU energy market and a brief incursion into the extant research on intangibles–firm performance relationship and its connection with corporate governance by looking at the relevant theories: RBV, the agency theory, the stewardship theory, and the upper echelons theory. The study design, including details about sample and model specification, is detailed in Section 3. Section 4 delineates regression results and related discussions while the last section is dedicated to concluding remarks.

2. Literature Insights and Empirical Expectations

2.1. An Overview of the EU Energy Market

Energy is widely recognised as one of the most valuable commodities, a sine qua non of all economic activities and a critical input for households’ welfare [6]. Drawing on the precepts of the neoliberal ideology, which foregrounded market competition, attempts to privatise and liberalise the energy industry marked the last decades on a planetary scale [25,26]. The deregulation and privatisation of the EU energy market were made possible by a package of legislative measures, which became obligatory in 1998 for electricity and 2000 for gas, thus revolutionising a state-owned utility. Prior to liberalisation, in the majority of EU countries, state-owned firms controlled the entire energy supply chain, from generation to transmission and distribution (Italy, Portugal, France, Greece, Ireland) while in other countries, such as Belgium and Spain, the energy industry was dominated by small private and vertically integrated enterprises [27].

The transition from a monopoly structure to a competitive market mainstreamed free trade between (giant) consumers, retailers, and producers, although the final price for consumers was not necessarily lower as one would expect [26,27]. While demonopolisation was expected to inject competition into the energy industry, the EU witnessed the reverse effect, a concentration of power, typically referred to as the Big Five. EDF Energy, RWE Npower, E.ON, ENGIE and ENEL form the so-called Big Five, companies that dominated the market in the 2000s, albeit the last decade’s financial figures highlight the deterioration of their competitive position [27].

The pioneering literature on financial markets has employed a simple linear paradigm assuming that prices reflect all extant information and, consequently, stocks are always traded at their fair value. This is the main thrust of the efficient market hypothesis (EMH) which has been fervently questioned on empirical grounds. Over the last decades, scholars have come to realize that EMH fails to explain the intricate price behaviour of the market. The irregularities peculiar to the energy market motivated researchers to move beyond traditional models of price dynamics. Subsequent literature scrutinized energy markets by means of multifractal analysis, whose genesis is linked to the seminal work of Mandelbrot in physics [28]. The energy market is highly volatile, exhibits seasonal patterns, is affected by price spikes (especially powerful during winter when heating demand is expanded in Europe), and faces challenges regarding storage at a reasonable price [25,26,29]. Reportedly, financial data shows scaling features in terms of sample moments (a pattern that repeats intra-daily, daily, weekly, and monthly). Moreover, a single characteristic scale exponent is not always sufficient which leads us to multiscaling or multifractality [28,29]. Nowadays, multifractality is largely considered a “stylised fact” or a universal feature of energy markets [30,31].

Over the past decade, the EU’s concerns about reducing greenhouse gases (mainly carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions) and achieving energy security have intensified, leading to dedicated policies and various green initiatives on the road to climate neutrality by 2050 [32]. Exogenous shocks have recently challenged the EU energy market (the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russo-Ukraine war). Currently, the main predicament is represented by the burdensome dependence on Russian natural gas, particularly in the context of the “gas crises” caused by the military tensions between Russia and Ukraine [33]. Ukraine used to be the major transit route for Russian gas transportation, as shown in Figure 1. A recent study [34] demonstrates that a ban on Russian energy inputs in the aftermath of the war would dramatically destabilise the economy of several EU countries (Czech Republic, Bulgaria, Slovakia, Lithuania, Finland) but the impact would be moderate in most countries because we do not live in a purely “Leontief world”, i.e., with zero substitution. Figure 2 allows us a comparison between EU countries in terms of energy consumption. It is worth noting the downward trend of energy consumption in the member states in the last decade. European Commission aims at reducing the final energy consumption by 36% by 2030 [32].

Figure 1.

EU imports of natural gas from Russia by supply route, 2017–2020. Source: European Commission [35].

Figure 2.

EU energy consumption (thousand tonnes of oil equivalent). Source: Own projection based on Eurostat data [36].

2.2. Intangibles and Firm Performance

The nexus between intangibles and corporate performance has been a concern to accounting, finance, and marketing scholars, being subjected to both theoretical discussions and empirical scrutiny. Drawing on the precepts of the resource-based view, rooted in the strategic management theory [37], several scholars advocate a positive relationship between intangible assets and firm performance. The main assumption behind the theoretical doctrine of RBV is that firm performance is a function of strategic resources. In his seminal work, Barney [38] contends that rare, valuable, non-imitable and non-substitutable resources are the key to a sustainable competitive advantage. While organisational resources include both tangible and intangible assets, intangibles seem to enjoy privileged status according to this theory owing to the peculiarities that make them hardly imitable and scarcely replaceable [3,39,40,41,42]. At this juncture, it is worth highlighting that sustainability does not translate into competitive advantages that persist indefinitely, nor does it refer to a specific timespan, but rather relates to the poor and insignificant possibilities of duplication [38,43]. The literature portrays IC management as a key driver of sustainability [10]. Based on survey data of Polish companies, Gross-Gołacka et al. [9] conclude that human capital bears the strongest impact on a firm’s sustainable development. The effect of IC on financial sustainability and the role of intangibles in predicting financial performance is also empirically evidenced in the work of Jordão and Almeida [11]. Thus, the endowment with intangibles can make a difference in corporate performance in today’s competitive and ever-changing business landscape.

Strategic management plays a pivotal role in separating successful firms from laggards as intangibles are not important per se [43,44]. Teirlinck [45] infers that companies’ financial performance is highly influenced by strategic R&D decisions (absorptive capacity, type of R&D, organisational structuring of R&D projects, and degree of openness) during financial distress times. The optimal configuration is found to vary with firm size.

Anecdotal evidence indicates that investments in intangibles, particularly R&D, lead to superior financial performance through product and service innovation [4]. Using the pharmaceutical industry as a research setting, Rahman [46] demonstrates that R&D investments are fruitful and boost firm performance, measured by ROA, ROE and Tobin’s Q. Spescha [47] infers that a company’s R&D expenditures positively affect its sales growth, though the impact varies with firm size, firm age and industry size, being more pronounced for small and mature companies. Lee and Kwon [48] examine US manufacturing companies and conclude that R&D intensity is a major determinant of firm performance. When conducting the analysis on stratified samples, based on the firm’s technological level, results show that the positive effect of R&D intensity is particularly salient in the high-tech manufacturing industry. Reportedly, there is negligible empirical evidence for the adverse impact of intangibles on performance in developing countries, ascribable to inadequate institutional infrastructure regarding intellectual property rights [42]. Other researchers have expanded the research area by demonstrating that firm performance comes as a result of the interplay between the three components of IC, namely human capital, structural capital and relational capital or the individual influence of one or more of these components, conducting studies in various contexts (Malaysia—[49]; Romania—[23] pharmaceutical industry of Jordan—[50]; information technology industry of Taiwan—[51]; non-financial listed firms from Western Europe—[52]; pharmaceutical industry of China—[1]; children’s clothing industry of Italia—[53]). Pertaining to the value creation process, Brătianu [54] points out that companies with similar potential IC can achieve different performances because the process of transformation into operational IC is impacted by organisational “nonlinear integrators” (i.e., organisational culture, management, leadership). The same idea, based on the precepts of thermodynamics and energy transformations, is substantiated by Bejinaru [55].

Previous research provides valuable insight into intangibles and organisational performance in research-oriented business sectors. However, little is known about the impact of intangibles on performance in the context of traditional industries, orientated mainly towards tangible assets. In this vein, Dženopoljac et al. [3] stress the need to conduct studies in less explored settings, traditionally capital-intensive industries, as science-driven businesses have been extensively analysed. Their research paper heads in this direction revealing that intangibles, proxied by calculated intangible value (CIV), have a positive effect on corporate performance in the oil and gas industry and are a key driver of a firm’s competitiveness. In light of these findings, it is expected that intangibles exert a positive influence on firm performance in the case of EU-listed firms in the electricity and gas industry. Accordingly, this study postulates the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Intangible assets are positively related to firm performance.

2.3. The Moderating Effect of CEO Duality and CEO Gender

Undoubtedly, corporate governance shapes firm behaviour and its principles are paramount for the sustainable development of a company [56]. A firm’s collapse is frequently linked to the lack of corporate governance mechanisms [15]. The upper echelons theory theorizes that the decision-making process and the investment behaviour of a company are contingent on the personal characteristics of the CEO [57]. Relatedly, firm performance is considered a key barometer of CEO managerial abilities [58].

The study considers two dimensions of corporate governance, namely CEO duality and CEO gender. There is a lack of consensus regarding the practice of holding both the title of CEO and the chairman of the board, commonly referred to as CEO duality [59]. The extant research on CEO duality and firm performance is effectively bifurcated into two distinct views, which are firmly grounded in classic economic theories, leading to a schism in the scientific landscape. On the one hand, the agency theory posits that the enhanced power stemming from the cumulation of roles makes the CEO prone to engage in accrual-based earnings management practices, which incurs substantial agency costs, erodes the fiduciary monitoring power of the board and, ultimately, adversely affects firm performance [58,59,60]. The main thrust of this theory is that agents (management) pursue their self-interest to the detriment of the interests of the principals (shareholders) [61]. Accordingly, independent boards play a meaningful role in curbing managerial entrenchment and myopic behaviour [62].

On the other hand, despite the potential managerial abuse, the negative connotation of duality has been debated, giving rise to another theory. The stewardship theory promotes a unified leadership that enhances the decision-making process, mitigates transaction costs, and can lead to superior performance [63]. The basic hypothesis of divergent interests that has been associated with the agency theory is rejected. Conversely, this theory shifts the focus from the CEO’s eminently selfish goals to the steward’s pro-organisational goals [61], claiming that CEO duality can counteract information asymmetry [59,64] and the so-called unity of command would eventually result in superior performance [63]. Following these arguments, it is expected that CEO duality moderates the intangibles–firm performance relationship, but both theories are borne out by empirical evidence [60,62], which explains the reluctance to predict the nature of the effect a priori.

Next, let us turn to CEO gender, a major sociodemographic attribute, scrutinised by both economists and sociologists. Women are subjected to discrimination and face different challenges related to education and work, as advocated by the liberal feminist theory [65]. Women and men do not compete on equal terms in the job market as earlier studies document a gender wage gap [66]. The view that CEO gender affects corporate performance is buttressed by several empirical studies which lend strong support to the upper echelons theory [57,67]. Female versus male-led companies exhibit dissimilarities in terms of leadership styles, risk aversion and confidence levels, with consequences on the investments and the financial health of the company [62]. For instance, Frank and Goyal [68] infer that managerial characteristics, inter alia CEO gender, are related to corporate leverage choices and female c-suite executives (CEO/CFO) are usually associated with lower leverage. Using the difference-in-difference approach, a recent study [65] concludes that corporate performance is fairly modest in the case of female-led companies as opposed to their counterparts’ results and attributes this finding to the low status of women in India and greater agency costs. Conversely, other studies [57,67] argue that female-led companies outperform their men-led counterparts.

Surveying the literature on intangibles and performance, one can find a handful of studies that considered various moderators and one study addressing the moderating effect of corporate governance on the IC–firm performance relationship. Using data from a panel of companies listed on the Saudi Stock Exchange, Hamdan et al. [15] contend that corporate governance positively impacts the relationship between IC and corporate performance operationalised through different proxies, reflecting financial, operational and market performance. As can be seen, previous studies have touched on only tangentially the moderating effect of CEO duality and CEO gender on the intangibles–firm performance relationship, adumbrating the idea of potential moderators. The status quo of insufficient studies exploring this issue prompted us to engage in this scientific endeavour, aimed at discovering whether the nexus between intangibles and performance is affected by CEO characteristics, namely CEO duality and CEO gender. This leads us to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

CEO duality moderates the relationship between intangible assets and firm performance.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

CEO gender (female) moderates the relationship between intangible assets and firm performance.

Figure 3 provides a synoptic view of the hypotheses and the conceptual lens that underpins the present study.

Figure 3.

Conceptual framework.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Data

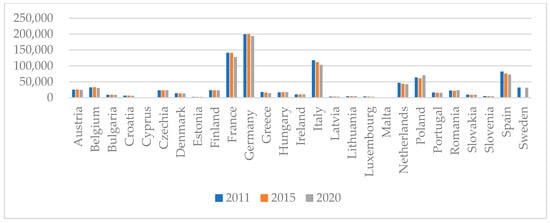

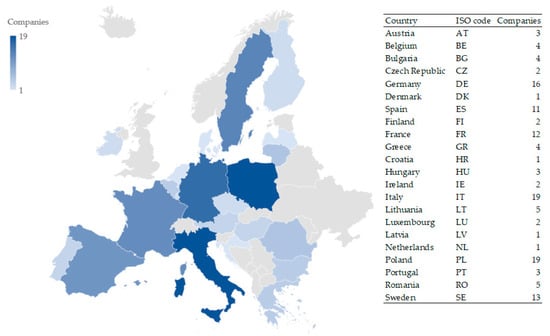

As previously mentioned, the current study aims to explore the causal relationship between intangibles and performance and the moderating effect of CEO duality and CEO gender. The analysis is based on a 10-year timeframe (2011–2020). Through a quantitative approach, the paper scrutinises a panel dataset of 133 EU-listed companies from the electricity and gas industry. Figure 4 gives a bird’s-eye view of the geographical distribution of the analysed companies. Both Italy and Poland (a developed country since 2018 according to FTSE Country Classification, [69]) host the headquarters of 19 electricity and gas companies, while 16 energy companies are located in Germany. The majority of the sampled enterprises are geographically concentrated in developed countries (Italy, Poland, Germany, Sweden, France, and Spain). Emerging countries from Eastern Europe (Romania, Bulgaria, Latvia, and the Czech Republic) are less attractive to investors in the energy sector as the data show.

Figure 4.

Companies’ location.

Secondary data regarding firm-level variables were retrieved from the ORBIS database, while Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) came from the World Bank database. The annual reports were also checked to collect data related to the CEO when required. The resultant sample includes 1330 firm-year observations, corresponding to an unbalanced panel data of 133 companies. To mitigate the potential effect of outliers and obtain unbiased estimates, all continuous variables are winsorized at 1st and 99th percentiles, respectively.

The study employs a panel data approach where temporal and sectional data are jointly considered. Several advantages account for the use of longitudinal data: more degrees of freedom, more sample variability, the possibility of analysing dynamic relationships and improved efficiency specification [70]. Longitudinal regression models can be estimated using two approaches: the fixed effects approach and the random effects approach. Following the results of the Hausman test, the null hypothesis is accepted (p > 0.05) which means that the random-effects regression approach is the preferred specification. Random effects models have been previously used by researchers in the realm of intangibles [71,72,73]. Three equations are estimated:

Performance = β0 + β1IA + β2CEOD + β3CEOG + β4LEV + β5SIZE + β6WGI

Performance = β0 + β1IA + β2IA ∗ CEOD + β3CEOG + β4LEV + β5SIZE + β6WGI

Performance = β0 + β1IA + β2IA ∗ CEOG + β3CEOG + β4LEV + β5SIZE + β6WGI

Hereafter, each equation is estimated in two variants, considering different proxies for firm performance, as described in the following sub-section.

3.2. Variables

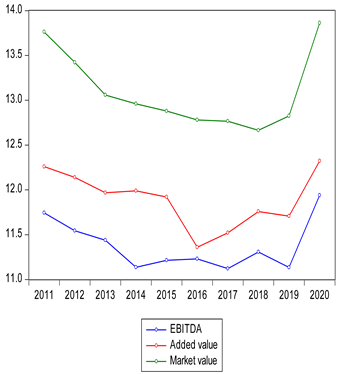

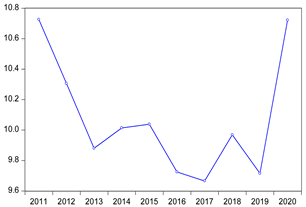

Firm performance is the dependent variable. Being a multidimensional concept, that encompasses multiple facets, its operationalization is challenging. To capture its very nature, the study considers two distinct aspects: earnings and market performance. Thus, consonant with earlier research, EBITDA serves as a proxy for company earnings and profitability [1,11], while market value is seen as an expression of market performance [1,3]. The use of more than one proxy is advisable as it allows us to verify the reliability of the results [57].

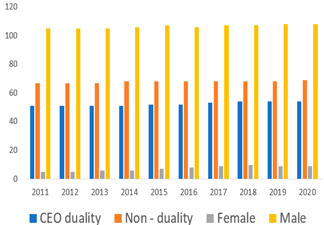

As an explanatory variable, the model includes the natural logarithm of intangible assets. The study considers the value of intangible assets reported in the balance sheet. CEO duality and CEO gender are the moderating variables. CEO duality is a dummy variable which equals 1 if CEO is also the Chairman, and 0 otherwise. CEO gender equals 1 if CEO is female, and 0 otherwise.

To reduce the effect of other factors that could potentially affect performance and lead to model misspecification and spurious results, the model includes three control variables. In line with previous studies, the control variables are leverage [41,74], firm size [15,41,42,57,74], and institutional quality. Details related to measurement and temporal evolution can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variables.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Matrix

Table 2 provides a finer-grained insight into the electricity and gas EU industry by reporting the mean, standard deviation, maximum and minimum values of performance indicators and other firm-level variables. With an average value of 1,640,778 euros of intangible assets, representing approximately 13% of the total assets, electricity and gas companies are still reluctant to invest large amounts of money in non-physical assets, typically associated with greater uncertainty and time-lagged results. Interestingly, the evolution of the performance indicators closely follows the nearly sinusoidal trajectory of intangibles as can be seen from the graphical representations in Table 1. On average, during the analysed period, companies have a market value of 6,635,434 euros, the value added equals 1,733,234 euros and EBITDA equals 1,028,200 euros. Only 6.5% of the top executives are female which shows that social biases and stereotypes are omnipresent even in the digital age. As for CEO duality, one can see that wearing two hats is a common practice in 43.55% of the sampled companies.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

A perusal of Table 3, which presents the correlation matrix and the variance inflation factors (VIF) (below the value of 10, introduced by Kennedy [75], respectively 5, proposed by Studenmund [76]) clearly shows that there are no suspicions of multicollinearity.

Table 3.

Correlation matrix and VIF.

4.2. Regression Results

Regression results are reported in Table 4, for each dimension of corporate performance. Model 1 designates the baseline specification, Model 2 augments this econometric specification with the interaction term between intangibles and CEO duality, while the interaction term between intangibles and CEO gender is incorporated in Model 3.

Table 4.

Regression results.

The first hypothesis, derived from the tenets of the RBV theory, was related to the positive impact of intangibles on firm performance. Notwithstanding the risky nature and the time-lagged impact highlighted by the previous literature [19], the results clearly show that investments in intangibles are a stepping stone to better performance in the electricity and gas industry.

More specifically, holding other factors fixed, a 1% increase in the value of intangibles is associated with around a 0.23% increase in EBITDA (Model 1a, Table 4) and a 0.25% increase in market value (Model 1b, Table 4). Thus, hypothesis 1 is confirmed, regardless of the dependent variable considered. The predictive accuracy of the models can be deemed fairly decent as adjusted R-squared equals 82.55% and 80.12%, respectively. A similar research sample was subjected to empirical scrutiny by Dženopoljac et al. [3]. Their work validated the positive effect of intangibles on firm profitability in the oil and gas sector. This result is also consistent with the shift of perspective associated with the energy industry as “the oil and gas companies have recognized that they are operating in a knowledge-based business where superior performance is achieved through the early identification and appraisal of opportunities and their speedy exploitation” [77].

The findings of the present study endorse the RBV theory which suggests that firm performance is contingent upon organisational resources, especially intangible ones that are likely to offer opportunities for differentiation and bring competitive advantages [40,42]. The paper also corroborates the results of previous studies that report a positive relationship between intangible assets and firm performance [3,4,46,48]. For instance, Nadeem et al. [4] bring to the fore the importance of IC in financial performance by looking at the BRICS economies. The results of the GMM system confirm the positive impact of the three IC components on corporate performance in the case of emerging economies. Rahman and Howlader [46] concentrate also on an emerging economy (Bangladesh) and explore the R&D activity of pharmaceutical firms. Their results show that R&D investment is positively correlated with firm value and financial performance and “ensures unique opportunity of innovation and future growth”. A different research setting is scrutinised by Lee and Kwon [48], who turn their attention to US manufacturing enterprises. Their analysis reveals that R&D intensity is an important contributor to firm performance and sustainable growth. As previously mentioned in the theoretical background, there is a dearth of evidence in the empirical literature regarding the adverse effect of intangibles. Of note is the study by Jiang et al. [42], which documents a negative effect of intangibles on corporate performance owing to inadequate institutional infrastructure regarding intellectual property rights.

Besides the positive impact on financial performance, which is not to be neglected, it should be mentioned that intangible investments are critical for green projects. Energy-dependent activities (fuel, transport, automation, etc.) increase atmospheric CO2 levels. Decarbonisation across all sectors requires a joint effort of national and supranational bodies and it is not practicable without R&D investments [78]. Regarding the control variables, they are statistically significant in almost all econometric specifications, suggesting that firm size, leverage, and the quality of institutions shape firm behaviour and impact its performance.

Hypothesis 2 predicted that CEO duality moderates the intangibles–firm performance relationship. To test this assumption, the interaction term added in Model 2 is analysed. The estimated results highlight that the practice of holding the joint positions of chairman of the board and the CEO of the firm adversely affects the relationship between intangibles and market performance. The coefficient is significant at the 5% level. It seems that the benefits of role separation outweigh the presumed advantages of CEO duality and goal alignment in the electricity and gas industry. Similar results are obtained when EBITDA is used as a measure of performance but without statistical significance. Therefore, the paper finds only partial support for the second hypothesis.

This finding can be attributed to the conflicting interests of agents and principals which open the way for managerial entrenchment and opportunism, as advocated by the agency theory. The blending of positions makes the board ineffective and has a detrimental effect on firm performance [61]. The results are consonant with previous research in the field, but run contrary to the stewardship theory, in favour of CEO duality. Using a longitudinal dataset of 179 Pakistani companies spanning 2009–2015, Naseem et al. [62] assert that management should be separated to augment corporate performance as the blending of positions has a detrimental effect on Tobin’s Q. Empirical support on this point is also documented by Alves [59], who shows that wearing two hats escalates the agency costs and results in lower earnings quality. Nuanpradit [58] further buttresses this view by arguing that the cumulation of roles is associated with sales activity manipulation and recommends the use of external strategic shareholder mechanisms to curb agency problems. Conversely, other studies tip the scale in favour of the stewardship theory, maintaining that the so-called unity of command minimises the cost of monitoring and eventually results in superior performance [63]. In an attempt to reconcile the two divergent theories, Wijethilake and Ekanayake [64] advance a middle path, maintaining that the blending of positions is favoured under high board involvement. Nevertheless, the authors admit that too much power in the hands of a CEO is detrimental to corporate performance. A recent study underscores the importance of emotional factors in the ethical issues of a company, concluding that employees that trust their co-workers and leaders are less prone to behave unethically [79]. As the second hypothesis is partially supported, it seems that the benefits of a dual structure prevail in the electricity and gas industry.

Next, the paper tests the third hypothesis by examining the moderating effect of CEO gender. Consistent with the prediction, CEO gender positively affects the relationship between intangibles and market performance. The interaction term of CEO gender with intangibles is positive, meaning that when the investments in intangibles grow in companies managed by women, financial performance has an upward trend. In retrospect, however, the female status faced many challenges on account of societal stereotypes and biases. Fortunately, today’s social and cultural milieu sees gender diversity in a positive light. Admittedly, most of the sampled companies are located in developed countries where there is a long tradition of a free market and there were significant advances regarding the condition of females over the past decades [80]. The results convincingly demonstrate that female-led companies manage intangible assets wisely, which ultimately translates into better performance in terms of both earnings and market performance. Thus, the study corroborates the third hypothesis, endorsing the upper echelons theory.

The current paper also substantiates the results of previous studies that documented that firms managed by women are associated with better performance and fewer risks, noting that women are more risk-averse, more vigilant in spending money and less likely to engage in managerial entrenchment practices [67]. These personality traits are especially important as the study is centred on the energy and gas industry, characterised by high volatility and seasonality. Compared to male executives, women tend to adopt a more cooperative approach to the decision-making process and their peers and take fewer financial risks, as a recent study infers [57]. Their conclusion regarding the gender-performance gap is based on the analysis of a questionnaire applied to a sample of 188 firms from Chile. A similar point is made by Flabbi et al. [81], whose work analyses Italian companies and reports that “a female CEO taking over a male-managed firm with at least 20% women in the workforce increases sales per employee by about 14%”. While the findings of this study are congruent with the results of most studies conducted in developed countries, they are generally in contrast with the papers exploring developing nations. Jadiyappa et al. [65] document a negative association between female CEOs and firm performance, explained by the patriarchal or gender-biased view typical of developing economies such as India. A negative relationship between the two constructs is also found in the case of the Chinese economy, a culture where “it is generally accepted in society that women should take on wider family responsibilities, rather than bearing the burden of being breadwinners” as a recent study highlights [82]. In the present study, the sampled companies are mainly located in developed countries, as argued earlier, which accounts for the positive effect of CEO gender on intangibles–firm performance relationship.

Figure 5 represents an updated version of the conceptual framework discussed in Section 2 and provides an overall view of the working hypotheses and the positive and negative relationships validated in the study at hand.

Figure 5.

Empirical expectations validation. Note: red arrow—negative relationship; green arrow—positive relationship; green tick—theory validated.

4.3. Robustness Checks

As a final exercise, an additional test to ensure the generalizability of the findings is conducted. The paper further considers value added (VA) as an alternative measure to the dependent variable, firm performance. Although there are many metrics to capture corporate performance, VA remains the most accurate measure according to the stakeholder view, being “created by the stakeholders and then distributed to the same stakeholders” [41]. Data regarding VA, as an expression of the total wealth created, was extracted from the ORBIS database. Computationally, value added is the sum of the following: taxation, net income, cost of employees, depreciation and interest paid. Robustness checks are reported in Table 4 (Model 1c, 2c, 3c). Analogously to the baseline analysis, results confirm that intangibles are an important driver of corporate performance. The hypothesised prejudicial effect of CEO duality to the intangibles–corporate performance relationship is not confirmed as results show that there is no statistical significance. This finding is in line with the main estimates when EBITDA serves as a proxy for firm performance. With regard to CEO gender, the values of the coefficients are barely distinguishable from the aforementioned estimates which confer robustness to the findings.

5. Conclusions

This paper provides evidence regarding the impact of intangibles on firm performance and the moderating effect of CEO duality and CEO gender. The key findings in this research are condensed below. Far from being a tautology, firm performance is contingent upon organisational resources, especially intangibles ones that are hard to imitate and are likely to bring opportunities for differentiation. While confirming the RBV theory, results show that this assumption is applicable to the electricity and gas industry, albeit the impact is less pronounced compared to science-driven industries. The study finds only partial support for the hypothesised deleterious effect of CEO duality on the intangibles–corporate performance nexus. Regarding CEO gender, all analyses endorse that female-led companies manage wisely intangibles assets, eventually augmenting earnings and market performance. This result is consistent with the upper echelons theory.

The present paper differentiates from previous research by analysing research setting less explored, the electricity and gas industry. Although the analysis is limited to the EU context, the findings may have international relevance as well and are a timely contribution to the extant literature. To our knowledge, this is the first study exploring the moderating role of CEO duality and CEO gender on the intangibles–firm performance nexus. In the not-so-distant past, c-suite roles were the preserve of men, but the current zeitgeist favours gender diversity and we look forward to seeing more women in top management positions. In practical terms, the current study stresses the need to pay particular attention to intangibles, understood as a critical input to firm performance, and take appropriate measures to counteract the under-representation of female directors on boards, following the proven beneficial effect of CEO gender on the intangibles–performance relationship. It is also important to notice that the analysed topic transcends discipline-specific approaches. The diversity approach alongside the green policies aimed at reducing energy consumption and CO2 emissions should be heeded by local, national, and supranational entities. As Costa-Campi et al. [78] emphasise, slowing or stopping global warming and transitioning to renewable power sources are not possible without public support for R&D projects.

Confining the research to the investigation of CEO duality and CEO gender, the paper does not consider the plurality of elements that constitutes corporate governance which is due to the data constraints. It may also be conceded that companies have intangibles that go beyond the traditional financial statements and are never disclosed on the balance sheet due to legislative issues such as internally generated brands. Dumay [83] criticises the temptation of “accountingisation” in measuring IC, maintaining that “contemporary IC measurement frameworks are reifying IC in the same manner in which tangible assets are portrayed within accounting, which is akin to attempting to make the intangible tangible”.

These shortcomings pave the way for future research in the realm of intangibles. Admittedly, it would be meaningful to take into account the undisclosed value of intangible assets. The analysis could also be developed by considering as potential moderators other attributes of the CEO (tenure, educational background, age, informal power) as well as board characteristics (independence, size), and ownership type (institutional, managerial). Another fruitful area of incipient inquiry links intangibles with energy transition within the context of UE aspiring goals of achieving climate neutrality by 2050.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.; methodology, M.C., M.M. and M.C.H.; software, M.C.; validation, M.C., M.M. and M.C.H.; formal analysis, M.C.; investigation, M.C.; resources, M.C.; data curation, M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.; writing—review and editing, M.C., M.M. and M.C.H.; visualization, M.C.; supervision, M.C., M.M. and M.C.H.; project administration, M.C., M.M. and M.C.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ge, F.; Xu, J. Does intellectual capital investment enhance firm performance? Evidence from pharmaceutical sector in China. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2020, 33, 1006–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, V.; Smith, S.J. Value creation and business models: Refocusing the intellectual capital debate. Br. Account. Rev. 2013, 45, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dženopoljac, V.; Muhammed, S.; Janošević, S. Intangibles and performance in oil and gas industry. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 1267–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.; Gan, C.; Nguyen, C. Does intellectual capital efficiency improve firm performance in BRICS economies? A dynamic panel estimation. Meas. Bus. Excell. 2017, 21, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, J.M.; Mosquera López, S.; Arenas, O.J. Assessing the Relationship between Electricity and Natural Gas Prices Across European Markets in Times of Distress. Energy Pol. 2022, 166, 113018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sart, G.; Ozkaya, M.H.; Bayar, Y. Education, Financial Development, and Primary Energy Consumption: An Empirical Analysis for BRICS Economies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejinaru, R.; Hapenciuc, C.V.; Condratov, I.; Stanciu, P. The University role in developing the human capital for a sustainable bioeconomy. Amfiteatru Econ. 2018, 20, 583–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Villiers, C.; Sharma, U. A critical reflection on the future of financial, intellectual capital, sustainability and integrated reporting. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2020, 70, 101999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross-Gołacka, E.; Kusterka-Jefmanska, M.; Jefmanski, B. Can elements of intellectual capital improve business sustainability?-The Perspective of Managers of SMEs in Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matos, F.; Vairinhos, V.; Maurício, P.; Leif, S. Intellectual Capital Management as a Driver of Sustainability. Pespectives for Organizations and Society; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Jordão, R.V.D.; de Almeida, V.R. Performance measurement, intellectual capital and financial sustainability. J. Intellect. Cap. 2017, 18, 643–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirino, N.; Ferraris, A.; Miglietta, N.; Invernizzi, A.C. Intellectual capital: The missing link in the corporate social responsibility–financial performance relationship. J. Intellect. Cap. 2022, 23, 420–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vătămănescu, E.M.; Gorgos, E.A.; Ghigiu, A.M.; Pătruţ, M. Bridging Intellectual Capital and SMEs internationalization through the Lens of Sustainable Competitive Advantage: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dalwai, T.; Mohammadi, S.S. Intellectual capital and corporate governance: An evaluation of Oman’s financial sector companies. J. Intellect. Cap. 2020, 21, 1125–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, A.M.; Buallay, A.M.; Alareeni, B.A. The moderating role of corporate governance on the relationship between intellectual capital efficiency and firm’s performance: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Learn. Intellect. Cap. 2017, 14, 295–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.C.; Guedes, M.J.; Soares, N.; da Conceição Gonçalves, V. Strength of the association between R&D volatility and firm growth: The roles of corporate governance and tangible asset volatility. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 88, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, H.M.; Che, M.R.; Rahman, A.; Hasan, M.S.; Ahmad, A. IC and Firms Performance: The Moderating Effect of Malaysia Corporate Government Code 2012 and 2017. Int. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. 2020, 24, 1646–1665. [Google Scholar]

- Shahwan, T.M.; Habib, A.M. Does the efficiency of corporate governance and intellectual capital affect a firm’s financial distress? Evidence from Egypt. J. Intellect. Cap. 2020, 21, 403–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garanina, T.; Hussinki, H.; Dumay, J. Accounting for intangibles and intellectual capital: A literature review from 2000 to 2020. Account. Financ. 2021, 61, 5111–5140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, W.; Matonti, G.; Nicolo, G.; Tucker, J. MtB versus VAIC in measuring intellectual capital: Empirical evidence from Italian listed companies. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2019, 13, 588–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulyadi, M.S.; Panggabean, R.R. Intellectual capital reporting: Case study of high intellectual capital corporations in Indonesia. Int. J. Learn. Intellect. Cap. 2017, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osinski, M.; Selig, P.M.; Matos, F.; Roman, D.J. Methods of evaluation of intangible assets and intellectual capital. J. Intellect. Cap. 2017, 18, 470–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Precob, C.; Mironiuc, M. The Influence of Reporting Intangible Capital on the Performance of Romanian Companies. Audit Financ. 2016, 14, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Accounting Standards Board. International Financial Reporting Standards; International Accounting Standards Board: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Resta, M. Multifractal Analysis of Power Markets Some Empirical Evidence. 2004. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/wpa/wuwpem/0410002.html (accessed on 7 May 2022).

- Ali, H.; Aslam, F.; Ferreira, P. Modeling Dynamic Multifractal Efficiency of US Electricity Market. Energies 2021, 14, 6145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weghmann, V. Going Public: Liberalisation A Decarbonised, Affordable and Democratic Energy System for Europe. The Failure of Energy Liberalization. 2019. Available online: https://www.epsu.org/sites/default/files/article/files/GoingPublic_EPSU-PSIRUReport2019-EN.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Segnon, M.; Lux, T. Multifractal models in finance: Their origin, properties, and applications. In The Oxford Handbook of Computational Economics and Finance; Chen, S., Kaboudan, M., Du, Y., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malo, P. Multifractality in Nordic Electricity Markets; Helsinki School of Economics: Helsinki, Finland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Aslam, P.; Ferreira, P.; Ali, H.; José, A.E. Application of Multifractal Analysis in Estimating the Reaction of Energy Markets to Geopolitical Acts and Threats. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Shi, F.; Yu, Z.; Yao, S.; Zhang, H. Asymmetric multifractality in China’s energy market based on improved asymmetric multifractal cross-correlation analysis. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2022, 594, 127027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. State of the Energy Union 2021—Contributing to the European Green Deal and the Union’s Recovery. Available online: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/energy-strategy/energy-union/sixth-report-state-energy-union_en (accessed on 17 June 2022).

- Rodríguez-Fernández, L.; Carvajal, A.B.F.; de Tejada, V.F. Improving the concept of energy security in an energy transition environment: Application to the gas sector in the European Union. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2022, 9, 101045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baqaee, D.; Moll, B.; Landais, C.; Martin, P. The Economic Consequences of a Stop of Energy Imports from Russia. Focus 2022, 84, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Quarterly Report Energy on European Gas Markets with Focus on the European Barriers in Retail Gas Markets. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/default/files/quarterly_report_on_european_gas_markets_q4_2020_final.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2022).

- Eurostat. Final Energy Consumption by Sector. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/energy/data/database (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Bharadwaj, A.S. A Resource-Based Perspective on Information Technology Capability and Firm Performance: An Empirical Investigation. MIS Q. 2000, 24, 169–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalonga, B. Intangible resources, Tobin’s q, and sustainability of performance differences. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2004, 54, 205–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, F.; Hussain Baig, M.; Rehman, I.U.; Latif, F.; Sergi, B.S. What drives the impact of women directors on firm performance? Evidence from intellectual capital efficiency of US listed firms. J. Intellect. Cap. 2019, 21, 513–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi-Belkaoui, A. Intellectual Capital and Firm Performance of U.S. Multinational Firms: A Study of the Resource-Based and Stakeholder Views. J. Intellect. Cap. 2003, 4, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.X.; Yang, Q.; Li, S.; Wang, Y. The moderating effect of foreign direct investment intensity on local firms’ intangible resources investment and performance implications: A case from China. J. Int. Manag. 2011, 17, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahy, J. The resource-based view of the firm: Some stumbling-blocks on the road to understanding sustainable competitive advantage. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 2000, 24, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, P.; Cabrer-Borrás, B.; del Mar Benavides-Espinosa, M. Intangible capital and business productivity in the hotel industry. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2020, 16, 691–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teirlinck, P. Configurations of strategic R&D decisions and financial performance in small-sized and medium-sized firms. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 74, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Howlader, S. The impact of research and development expenditure on firm performance and firm value: Evidence from a South Asian emerging economy. J. Appl. Account. Res. 2022, 23, 825–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spescha, A. R&D expenditures and firm growth–is small beautiful? Econ. Innov. New Technol. 2019, 28, 156–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kwon, H.B. Synergistic effect of R&D and exports on performance in US manufacturing industries: High-tech vs. low-tech. J. Model. Manag. 2021. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bontis, N.; Chong, W.C.K.; Richardson, S. Intellectual capital and business performance in Malaysian industries. J. Intellect. Cap. 2000, 1, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharabati, A.A.A.; Jawad, S.N.; Bontis, N. Intellectual capital and business performance in the pharmaceutical sector of Jordan. Manag. Decis. 2010, 48, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.Y.; Chang, C. Intellectual capital and performance in causal models. Evidence from the information technology industry in Taiwan. J. Intellect. Cap. 2005, 6, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sardo, F.; Serrasqueiro, Z. A European empirical study of the relationship between firms’ intellectual capital, financial performance and market value. J. Intellect. Cap. 2017, 18, 771–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucci, T.; Simoni, C.; Zanni, L. Measuring the relationship between marketing assets, intellectual capital and firm performance. J. Manag. Gov. 2015, 19, 589–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brătianu, C. Intellectual capital research and practice: 7 myths and one golden rule. Manag. Mark. 2018, 13, 859–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejinaru, R. Knowledge strategies aiming to improve the intellectual capital of universities. Manag. Mark. 2017, 12, 500–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Achim, M.V.; Văidean, V.L.; Ioana, A.; Popa, S. The impact of the quality of corporate governance on sustainable development: An analysis based on development level. Econ. Res. Istraživanja 2022, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Méndez, C.; Inostroza Correa, A. Gender and financial performance in SMEs in emerging economies. Gend. Manag. 2022, 37, 603–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuanpradit, S. Real earnings management in Thailand: CEO duality and serviced early years. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2019, 11, 88–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, S. CEO duality, earnings quality and board independence. J. Financ. Rep. Account. 2021. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorata, N.T.; Petra, S.T. CEO duality and compensation in the market for corporate control. Manag. Financ. 2008, 34, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abels, P.B.; Martelli, J.T. CEO duality: How many hats are too many? Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2013, 13, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseem, M.A.; Lin, J.; ur Rehman, R.; Ahmad, M.I.; Ali, R. Does capital structure mediate the link between CEO characteristics and firm performance? Manag. Decis. 2020, 58, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.J.; Kang, K.H. The moderating effect of CEO duality on the relationship between geographic diversification and firm performance in the US lodging industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 1488–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijethilake, C.; Ekanayake, A. CEO duality and firm performance: The moderating roles of CEO informal power and board involvements. Soc. Responsib. J. 2020, 16, 1453–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadiyappa, N.; Jyothi, P.; Sireesha, B.; Hickman, L.E. CEO gender, firm performance and agency costs: Evidence from India. J. Econ. Stud. 2019, 46, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.D.; Zhang, X.; Nguyen, T.H. The gender wage gap and the presence of foreign firms in Vietnam: Evidence from unconditional quantile regression decomposition. J. Econ. Stud. 2022, 49, 489–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.A.; Vieito, J.P. Ceo gender and firm performance. J. Econ. Bus. 2013, 67, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, M.Z.; Goyal, V.K. Corporate Leverage: How Much Do Managers Really Matter? SSRN Electron. J. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- FTSE Russell. Poland: The Journey to Developed Market Status. Available online: https://content.ftserussell.com/sites/default/files/research/poland---the-journey-to-developed-market-status_final.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Ramos, C.M.Q.; Casado-Molina, A.M. Online corporate reputation: A panel data approach and a reputation index proposal applied to the banking sector. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 122, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, N.A.; Okwo, M.I.; Obinabo, C.R. Effect of Intangible Assets on Corporate Performance of Selected Commercial Banks in Nigeria (2012–2018). IOSR J. Econ. Financ. 2020, 11, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosiana, N.; Surjandari, D.A. The Effect of Hidden Value of Intangible Assets, Investment Opportunity Set, and Environmental Performance on Economic Performance. J. Econ. Financ. Account. Stud. 2022, 4, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalirezaei, H.; Anvary Rostamy, A.A.; Saeedi, A.; Zaghard, M.K.V. Corporate social responsibility and bankruptcy probability: Exploring the role of market competition, intellectual capital, and equity cost. J. Corp. Account. Financ. 2020, 31, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppong, G.K.; Pattanayak, J.K. Does investing in intellectual capital improve productivity? Panel evidence from commercial banks in India. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2019, 19, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, P. A Guide to Econometrics, 6th ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2008; p. 199. [Google Scholar]

- Studenmund, A.H. Using Econometrics: A Practical Guide, 6th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2016; p. 234. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, R.M. The Development of Knowledge Management in the Oil and Gas Industry. Universia Bus. Rev. 2013, 40, 92–125. [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Campi, M.T.; Duch-Brown, N.; García-Quevedo, J. R & D drivers and obstacles to innovation in the energy industry. Energy Econ. 2014, 46, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mura, L.; Zsigmond, T.; Machová, R. The effects of emotional intelligence and ethics of SME employees on knowledge sharing in Central-European countries. Oeconomia Copernic. 2021, 12, 907–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vita, L.; Mari, M.; Poggesi, S. Women entrepreneurs in and from developing countries: Evidences from the literature. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flabbi, L.; Macis, M.; Moro, A.; Schivardi, F. Do female executives make a difference? The impact of female leadership on gender gaps and firm performance. Econ. J. 2019, 129, 2390–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Hassan, A. Management gender diversity, executives compensation and firm performance—Evidence from growth enterprises markets (gem) listed companies in China. Int. J. Account. Inf. Manag. 2022, 30, 115–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumay, J.C. Intellectual capital measurement: A critical approach. J. Intellect. Cap. 2009, 10, 190–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).