Abstract

The aim of this study is to develop a new performance evaluation tool that is stringently applied to the hotel chains, considering the associated ethical marketing dimensions to measure its proper strategic, tactical, and operational role and impact within hospitality marketing management plans, campaigns, and strategies implemented. A Delphi technique was conducted as the selected research qualitative method, comprising three rounds. A total of 23 panel participants, such as directors and managers of marketing, e-commerce, sales, and branding, completed all three rounds. Two major areas of ethical marketing, internal and external, both divided into five dimensions, each with underlying items, were found to comprise the ethical marketing model for luxury hotel chains: (1) internal area of marketing (with five dimensions: integration, training, equal opportunities, performance evaluation, and smart policies) and (2) external area of marketing (with five dimensions: stakeholders, booking platforms and CRM, marketing plan, digital marketing campaigns, and social media platforms). The study concludes with useful insights and remarks. The generalisability of the results may be limited owning to the partial or not full applicability across all luxury hotel chains. The model still needs to be empirically applied in luxury hotel chains to enrich its robustness, covering a wider spread of four- and five-star luxury hotels. There is a growing potential for researchers, hotel decision makers, and marketing and sales managers and directors to achieve many advantages and benefits from the proposed model, supporting the efforts for ethical marketing theory and practice, such as hotel brand positioning strategies and formulation of more targeted and finely tuned ethical marketing strategies, tactics, and plans. This is the first study to develop and validate a performance evaluation tool of ethical marketing for luxury hotel chains. This pioneering approach extends the scope into ethical marketing because this model has never been used in this area.

1. Introduction

In general, “business ethics is a study of business activities, decisions and situations where the right and wrongs are addressed. Businesses have become a major provider to the society, in terms of jobs, products and services” [1] (p. 93). Furthermore, business ethics are important because they enable the benefits and also the problems related to ethical issues within the company to be identified in addition to the fact that business ethics provide clues for new directions for the present as well as a traditional perspective and view of ethics [2].

The field of ethical marketing research is growing, extending to the ethical dimensions of marketing [3]. In the marketing context, there are several ethical critics related to major issues that have gained international attention, namely liability of products, product dumping, false or misleading advertising, personal selling tactics, price gouging, foreign child labour, or low-income marketing, among many others (e.g., [3,4,5]).

Nowadays, it is widely acknowledged that ethical marketing stands out as increasingly called for, with emergent, recognized, and valid issues in the hospitality customer’s behaviour. “Despite extensive and thoughtful effort devoted to marketing ethics scholarship over the past several decades, the incidence of ethical violations in marketing practice remains high” [6] (p. 39). Although some models of marketing ethics were developed with the intent to help marketers to achieve the identifications and evaluation the ethical issues, in fact, these frameworks are mostly only known as an “add-on” by the majority of marketing scholarship [6]. In light of this, new approaches, paradigms, and advances are required in hotels’ marketing performance.

Renowned international entities such as the Global Reporting Initiative [7] as well as the Global Compact [8] recognise the importance of ethical behaviour in business communication. In fact, business ethics has a strong impact and role in companies’ behaviour and decisions underlying their marketing campaigns [9]. As Robertson, Voegtlin, and Maak [10] and da Costa et al. [11] stated, in recent years, ethics in companies have naturally increased worldwide through conferences, forums, and congress, leading the promotion of ethical practices, models, and studies in this subject. From another perspective, de Bakker, Rasche, and Ponte [12] attested that it is truly essential to approach business ethics in company marketing campaigns with the purpose of understanding how the ethics dimensions relate to types of marketing campaigns and the extent to which they influence company performance levels (e.g., return).

Although hospitality ethics studies represent a minority of the body of research in this field, over the last 10 years, this area has gained increasing attention. However, there is a need to continue to develop knowledge about ethics in hospitality by providing more explanatory value for ethical practices in hospitality [13]. As research topics, Myung [13] suggested that theoretical frameworks need to be clearly defined and rigorously applied and tested, and further exploration and discussion of various ethical issues require further research because hospitality ethics research remains at an early stage in its theoretical discovery and description. “Ethically managed hotels show deference to the rights of all stakeholders while not diminishing business value” [14] (p. 10). Currently, there is no ethical marketing framework to analyse and evaluate the performance in the context of the hotel industry. Upon the bases of what dimensions and variables a hotel marketer can define and assess, what is largely appropriate, suitable, right, or acceptable in domestic and international hospitality business when addressed in strategic, tactic, and operational marketing plans? Hence, the formulated research question that guides this study is as follows: How can the way in which hotel chains act in ethical marketing be evaluated?

Thus, this study aims to address a set of two specific objectives, namely (1) developing a tool that allows one to analyse and evaluate the ethics marketing practices in luxury hotel chains’ promotional campaigns and (2) to develop and validate an ethical marketing model for luxury hotel chains. Luxury hotel chains are based on high requirements, standards, and assessments of the leading quality assurance, which are recognized worldwide by the trade and customers. In addition, it is noteworthy that there are many companies that only focus on selling their products and also attracting new customers by means of marketing plans and campaigns without ethical issues [15]. Consequently, this study aims to address this directly identified cutting-edge gap.

This study is structured into four sections addressing the following areas: a literature review on ethical marketing, the methodology approach using a qualitative study based on the Delphi method, and the results and discussion supporting the development and validation of model. Finally, the main conclusions and findings are highlighted, and in addition, the research contributions, implications for management, limitations, and suggestions for future research are presented.

2. Literature Background

2.1. Scope and Definition of Marketing Ethics

The scope of the definition of ethical marketing is complex and extensive in the literature not only over the last 30 years but also over different time intervals, making it difficult to summarise and review a consensual definition of ethical marketing. However, the two most-cited marketing ethics definitions that are dominant in the literature review are mentioned. Murphy et al. [16] (p. 27) defined marketing ethics as “the systematic study of how moral standards are applied to marketing decisions, behaviours and institutions”. Gaski [17] (p. 316) considered marketing ethics as “standards of conduct and moral judgement applied to marketing practice”. In addition, there is a gap regarding an actual definition of marketing ethics, as surprisingly few authors have made such a contribution [18]. Toward this direction, the typical problem with universal application of ethical marketing codes is that ethical standards vary across institutional, organisational, and business environments and from culture to culture [18].

2.2. Ethical Marketing—A New Definition

To bridge the aforementioned research gap in terms of the absence of a complete and current definition of ethical marketing, there seems to be a need to move forward in developing a new concept of ethical marketing that leads to the issue of modernity and brings it up to date. Hence, a new broad redefinition of the concept of ethical marketing is proposed, namely that the ethical marketing concept is composed of an amalgam of internal and external conduct codes in twelve top dimensions, such as (1) decent work of manufacturing staff; (2) brand equity; (3) sustainable production, distribution, and trade; (4) transparency of criteria in selection of key suppliers; (5) satisfaction of all stakeholders; (6) suitable distribution channels; (7) trust in the customer relationship; (8) privacy/security of customer data; (9) legal revenue sources; (10) balanced cost structure; (11) smart retail marketing mix; and (12) consistency in channels and platforms of promotion/sales/payment. The basis of this proposed definition consists of a summary amalgam of boundaries, issues, trends, and assumptions derived from the gaps that the proposed model fills out.

2.3. Ethical Consumption and Ethical Consumer

Generally, the global consumer society is characterised by various types, forms, and habits of consumption. In fact, the consumer plays a decisive role in making organisations accountable to society [19].

Ethical products do not harm the environment or society, i.e., no process, production, individual, animal, or raw material is used in an unethical way. Conversely, unethical products are considered those that harm society as a whole, resulting from inappropriate behaviour by the organisation at the process or production level through manufactured products that are considered potentially harmful to consumers [20].

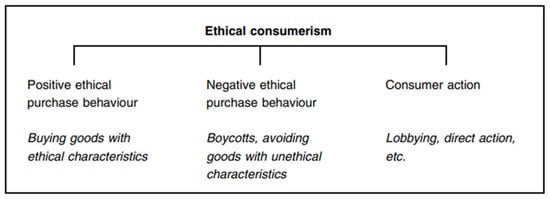

In the field of ethical consumption, some authors (e.g., [19]) argue for three types of ethical consumption, namely positive ethical consumption, negative ethical consumption, and the action of the ethical consumer action (Figure 1). Positive ethical consumption refers to the selection of ethical products at the time of purchase instead of other products that are considered unethical or that have unknown characteristics. Negative ethical consumption is supported in the boycott of unethical products, in which consumers refuse association with certain issues (e.g., animal testing and captive breeding). As the third and last type, ethical consumer action is the result of both lobbying and direct actions for the purpose of influencing other consumers

Figure 1.

Three types of ethical consumerism. Source: Tallontire, Rentsendorj, and Blowfield [19] (p. 7).

Furthermore, regarding ethical consumers, there are three profiles of consumers: the activists, the ethical, and the semi-ethical. Activists are recognised as the main advocates of ethical consumption, as they compare products and encourage other consumers to learn about and try ethical products. Ethical consumers want more information about the ethical products they buy. Finally, semi-ethical consumers consume ethical products irregularly and generally only buy more if they are influenced and if the products are more appealing and easier to access [19].

From another perspective, Carrigan and Attalla [20] classified consumers into four types based on their ethical awareness and ethical purchasing intention. Unaware consumers possess a low level of ethical awareness and low ethical purchase intention. Confused and uncertain consumers demonstrate a low level of ethical awareness yet exhibit high ethical purchase intention. Cynical and disinterested consumers have a high level of ethical awareness but nevertheless have no purchase intention. Finally, careful and ethical consumers obtain sufficient information about the social responsibility of organisations and are highly ethical in their purchasing activities.

2.4. Principles of Marketing Ethics

Marketing ethics refers to the standards and norms that define acceptable conduct, presupposing a relationship of trust between the consumer and the product. This is based both on the qualities shown by the product and on the consumer’s perspective, assuming that it corresponds to what was communicated by the organisation. Marketers must keep up with changes and trends in societal values in order to promote socially responsible and ethical behaviour [21,22]. “The high visibility of marketing activities and managers efforts to administer their firms’ relationships with its stakeholders, continue to keep ethics among the most challenging issues for marketing managers and academics alike” [5] (p. 256).

The main milestones in the field of ethical marketing research indicate that there are several perspectives that generally converge among the various authors. Thus, ethical marketing is categorised into different sub-disciplines, such as advertising and pricing (e.g., [23,24]). Moreover, other authors [17,25] characterise ethical marketing in the normative and positive category, whilst others [26] alternatively advocate a combination of these two categories.

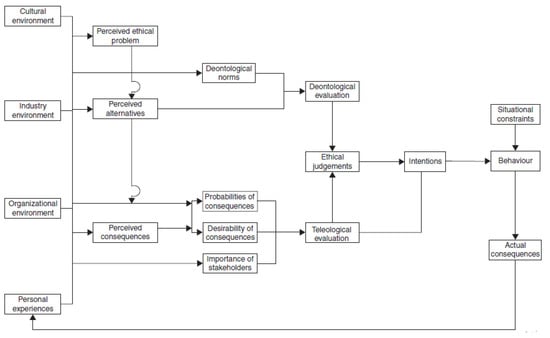

Over the years, Hunt and Vitell [25] pioneered the general theory of marketing ethics (Figure 2), recognised as the most widely used by scholars and practitioners in approaches of marketing ethics management, among the other models and frameworks developed to support ethical decision making in marketing [25,26,27]. This model, the general theory of marketing ethics, attempts to “explain the decision-making process for problem situations having ethical content” [25] (p. 5).

Figure 2.

General theory of marketing ethics. Source: Hunt and Vitell [25] (p. 8).

Within marketing ethics, the most recognised and referenced standard model of ethical marketing is divided into four major dichotomies, such as positive/normative and micro/macro, as well as categorised by a set of functional areas of marketing ethics ([3]). Table 1 presents the categorisation of marketing ethics divided into normative and positive according to the macro and micro context.

Table 1.

Categorisation of marketing ethics. Source: adapted from Hunt [28], Hunt and Vitell [25], and Gaski [17].

In Table 2, the topical areas of marketing ethics are shown, followed by three areas with related topics covered in research on marketing ethics.

Table 2.

Topical areas of marketing ethics. Source: Nill and Schibrowsky [5] (p. 258).

Marketers have the autonomy to control what they say to customers, where they say it, and how they do it. When mass media, such as television or radio programmes, products or promotional materials are perceived as offensive in certain types of events, they often create strong negative reactions in customers. This is the case with a promotion that uses stereotypical images or uses gender as a feature or element, which some individuals consider as offensive [27].

Advertising is one of the most pervasive and powerful phenomena in the contemporary world, denoting a social, economic, and ethical influence on culture, lifestyle, consumption, and daily choices. The consumer is deeply influenced by advertising in the way it is perceived and in the evaluation of relationships, behaviours, values, and judgements. When advertising is good, it incites the consumer to choose and act rationally. Conversely, a bad advertisement has an opposite effect on the consumer, influencing them to make bad choices, turning them into destructive actions for both themselves and society [28].

2.5. Ethics and Ethical Marketing in the Hospitality Industry

Currently, ethical tourism is a widely established concept, with its genesis stemming from sustainable tourism [29], with the difference that an ethical hotel is a broader term compared to a green hotel. Ethical tourism comprises consideration and responsibility covering the physical environment and human and cultural heritage of destination countries [30]. In the hospitality industry, ethics has been recognised as one of the most relevant issues [31]. This is due to the contending complexities directly associated with managing ethical behaviour reflected in a working environment with many frequent ethical issues, diverse individuals, and also worldwide locations [32].

Stevens [33] advocated that ethical management means serious business for hoteliers, as they are responsible for ethical leadership and communicating organisational standards. Within this context, Stevens [33] summarised six ethical issues of hotel managers, such as (1) lack of employee work ethic/low industry pay; (2) diversity issues; (3) guest and employee theft; (4) maintaining rate integrity; (5) issues with contracts/management companies and owners; and (6) lack of ethics by guests. With the intention of establishing customer loyalty, maintaining a cohesive team of hoteliers and building trust with commercial stakeholders, hospitality organisations have established a set of ethical standards and instituted ethical practices [34,35,36,37,38]. The ethical issues in the hospitality workplace should be embedded and repeatedly emphasised and discussed in this industry [36].

Although there are many studies on ethical behaviour, they are almost entirely related to industry and corporate business. In fact, research on applied ethics in the hospitality industry has been very scarce [39,40,41]. Therefore, the topic of ethics education in hospitality has been considered a growing trend in the last two decades, which encourages the industry through the benefits it can obtain [42].

There is agreement among professionals in the hospitality industry that ethics is undoubtedly one of the most important and addressed issues [43]. In the hotel sector, ethical consumption generally has a positive connotation (e.g., customers prefer to stay in a green hotel) [44]. Nicolaides [14] argued that the intense competition throws up challenges for managers to increase profits while simultaneously confronting an endless array of ethical dilemmas in their daily operations related to marketing their real estate services and products with sincerity. Moreover, “a hotel exuding an ethical climate reduces turnover, and augments service quality and guests’ experiences. Ethical practices in any shape or form are likely to increase a hotels’ employees’ productivity and result in higher profits” [14] (p. 2).

3. Methodology

3.1. Delphi Technique

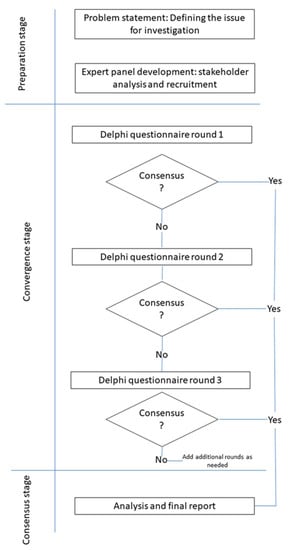

The Delphi method was applied using the three-stage procedure process (as shown Figure 3) according to Donohoe and Needham [45], who reviewed the Delphi techniques applied in tourism. Avella [46] argued that the Delphi method can be particularly advantageous in types of research where there are multidisciplinary issues.

Figure 3.

Delphi process. Source: Donohoe and Needham [45].

Delphi is recognised as one of the most suitable techniques to conduct and validate a type of study of this nature due to the fact that it allows intensive and broad exploration of the participants’ viewpoints by carrying out the associated stage rounds composing the approach of this method [45]. Through a specific question, the Delphi method aims to develop a range of relevant arguments and allows exposure of the reasons behind the different opinions, taking into account the participants in the panels [46,47]. The Delphi Technique remains a widely used tool for gathering input on real-world problems or scenarios [48]. Specifically, the most important consideration when conducting a Delphi study is that participants selected are qualified in order to determine the quality of the study’s outcomes overall [48].

Given the inherent complexity of the ethical marketing concept, it is assumed that the research process will require participants to engage with complex issues identified related to ethical marketing dimensions in the context of luxury hotels. It is suggested that a qualitative Delphi technique is likely to provide a forum amongst previously selected anonymous panellists in which to respond in depth, without any judgement from other participants in the panels.

3.2. Preparation Stage: Sample Design and Data Collection

Regarding the participants for this study, they were chosen according to the identification of a homogeneous standard, which was based on the analysis of the identification of their advanced knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs) to support the uniform selection among them. Based on these assumptions, a total of 23 participants took part in this study, in line with the consensus sample definition parameters of renowned authors (e.g., [48,49,50,51,52]) who advocate that the sample should range between 10 and 35 participants. Given this, it can be inferred that 23 participants in this study is considered an optimal number to achieve accuracy of results. The participants’ sociodemographic profile regarding age, gender, and nationality as well as education is characterized as follows: the age range is between 30 and 55 years old; 10 participants are male, and 13 are female; and as regards education level, all participants have degree-level education, and some also have a Master’s degree; and Portugal, Brazil, Dubai, France, Italy, Spain, Tunisia, Qatar, Southern Europe, and the USA are the nationalities of the participants. The participants’ profile averages five years of experience in international four- and five-star luxury hotel chains and groups of recognised reputational value in the worldwide tourism and hospitality industry as well as their professional roles and positions cumulatively endorsed by their peers and stakeholders. Additionally, Table 3 shows the participants’ information as well as their professional position and hotels classification. Sample selection was considered on the basis of the position of Marketing and Sales Director and the position of Brand and Sales Manager.

Table 3.

Participants information.

The three rounds, in an online meeting format (software e-Delphi.org) (e-Delphi privacy policy is fully GDPR (EU General Data Protection Regulation 2016/679) and U.S. Privacy Law compliant) due to the outbreak of pandemic crisis, lasted from 60 to 90 min and were transcribed. At the beginning of each of the three rounds, the researchers explained the research ethics and the main purpose of the study as well as the expected aims. Initially, 30 participants were expected to participate, but then, prior to round 1, some informed that they could not guarantee availability for all rounds given the period in which they were scheduled. Table 3 presents the details of the participants’ information, namely their roles.

4. Results

4.1. Convergence Stage: Delphi Rounds

In the first round (round 1), three management, marketing, and tourism researchers separately summarised and coded the received responses related to the potential dimensions divided into internal and external areas. Then, the data were compared, the differences simplified, and the final list with the five underlying dimensions derived from each of the two areas was compiled (Table 4). In the second round (round 2), the five dimensions of the internal areas were coded, and the five dimensions of the external areas referred to above were re-presented to the group of participants (Table 5). In the third and final round (round 3), the dimensions and items from both areas were properly combined and ranked as the final model (Table 6), with 50 items (22 items in the dimensions of the internal areas and 28 items in the dimensions of the external areas) in total. Round 1 was held in October, round 2 in November, and round 3 in December 2021, respectively. The high response rate throughout the various rounds is noteworthy, as the total sample of 23 participants effectively participated in all three rounds not in a face-to-face format but in an online meeting format (e-Delphi), mainly due to the geographic and scheduling constraints of each participant as well as the pandemic crisis, thus ensuring their full attendance.

Table 4.

First round results.

Table 5.

Second round results.

Table 6.

Third round results.

Regarding the final validation of the ethical marketing model for luxury hotel chains, consisting of a performance evaluation tool based on a framework, a set of assessment criteria was included. It ranges from 0 to 4 (0—no development, and 4—total development) comprising both areas (internal and external) and closing with the global result expressed in a final score of 200 points, ranging from very poor level (0–49 points) to excellent level (190–200 points) in this framework (as shown below in Table 7).

Table 7.

Ethical Marketing Model for Luxury Hotel Chains.

4.2. Consensus Stage: Analysis and Final Report

This last stage consists of the final consensus analysis by the panel of experts from previous rounds in order to validate the ethical marketing model for luxury hotel chains, resulting in an innovative and useful performance evaluation tool using a practical and operational assessment framework.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The major theoretical contribution of this research points to the new proposed concept of ethical marketing. Ethical marketing is the key driver for brands and products to share value fairly on the market at all stages of the production and advertising/promotional cycle, with credible awareness and strategic positioning standing out from competitors, based on a broad market and covering all segments and targets. Ethical marketing defines an ethical consumption pattern resulting from the purchase decision process of ethical consumers, typically conditioned between choosing a brand or product with ethical or unethical practices. Ethical marketing is a trigger for conscious consumption with essence, purpose, and relevance to society both on the supply and demand sides. In summary, the main mission of ethical marketing is to make conscious the brands and products that are not yet conscious.

As the major methodological contribution of this study, a new tool was developed and validated to evaluate the performance of ethical marketing performed by luxury hotel chains. Ethical hotel marketing in luxury hotels is witnessed in all sectors of the hospitality industry. This ethical marketing model applied to luxury hotel chains is sustained through the external and internal areas, underpinning both the respective dimensions (internal: integration, training, equal opportunities, performance evaluation, and smart policies; and external: stakeholders, booking platforms and CRM, marketing plan, digital marketing campaigns, and social media platforms) represented in this new validated model.

This research approach greatly extends the scope in the ethical marketing and luxury ethical hospitality field because the development of a model of ethical marketing as a performance evaluation tool has never been undertaken in the context of the luxury hotel industry. This novel strategic, tactic, and operational model addresses what is directly associated with the ethical marketing topics for luxury hotels as a competitive value added. Ethical marketing may make great practical contributions to this growing industry and to the development of new customers’ experiential paradigms into ethical hospitality consumption, seeking ethical hotel chains, groups, and brands.

A novel taxonomy was proposed, developed, and validated, which serves as a useful performance tool for systematic, integrative, and synergic best ethical marketing practices underlying luxury hotels in addition to boundaries and key components of the luxury hospitality sector. In addition, the expectation is that luxury hotel customers intend to have an immersive experience, advancing their accuracy of ethical value attribution. In general, the research topic of this study formulates the continuous state of hospitality ethics research and advances a future research agenda for hospitality ethics research into ethical marketing concerning luxury hotels in particular.

To sum up, the most principal findings of this study are presented as follows:

- The new proposed concept of ethical marketing;

- The development and validation of a new tool to evaluate the performance of ethical marketing performed by luxury hotel chains;

- The internal areas of the ethical marketing model applied to luxury hotel chains: integration, training, equal opportunities, performance evaluation, and smart policies;

- The external areas of the ethical marketing model applied to luxury hotel chains: stakeholders, booking platforms and CRM, marketing plan, digital marketing campaigns, and social media platforms.

As a limitation, the initial aim was to obtain a total of 30 participants in each round, but this was not possible due to their unavailability for the schedule of the rounds despite several attempts. Therefore, the other limitation refers to the fact that this model is pioneering, so it still needs to be placed in the context of other hotel studies on ethics.

Regarding future research, the validation of the ethical marketing model for luxury hotel chains in smart luxury hotels and eco resorts is suggested as well as other emergent typologies of hotels (e.g., millennial hotels). Furthermore, it is suggested that this evaluation tool should be validated by a quantitative analysis to increase its scientific robustness. From a tourism multidisciplinary perspective, this study presents innovative and useful inputs in order to continuously map the ethical marketing promoted by luxury hotels.

Marketing managers and directors, sales and marketing managers and directors, sales managers, brand managers, communication managers, and CRM and loyalty managers and directors should invest increasingly in an ethically integrated offer in the continuous improvement of their services, commodities, and support infrastructures to provide customers with an excellent ethical hospitality experience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.S.; methodology, V.S. and N.A.; validation, V.S. and N.A.; formal analysis, N.A.; investigation, V.S.; resources, V.S.; data curation, V.S.; writing—original draft preparation, V.S.; writing—review and editing, V.S. and N.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is financed by national funds through FCT—Foundation for Science and Technology, IP, within the scope of the reference project UIDB/04470/2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abdullah, H.; Valentine, B. Fundamental and Ethics Theories of Corporate Governance. Middle East. Financ. Econ. 2004, 4, 88–96. [Google Scholar]

- Crane, A.; Matten, D. Business Ethics, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nill, A.; Schibrowsky, J.A. Research on Marketing Ethics: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Macromark. 2007, 27, 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, C.B.; Wotruba, T.R.; Low, T.W. Direct selling ethics at the top: An industry audit and status report. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2002, 22, 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, D. An empirical examination of marketing professionals’ ethical behavior in differing situations. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 24, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abela, A.V.; Murphy, P.E. Marketing with integrity: Ethics and the service-dominant logic for marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 3953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Reporting Initiative. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/ (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Global Compact. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/ (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Jones, C.; Parker, M.; Bos, R.T. For Business Ethics; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, D.C.; Voegtlin, C.; Maak, T. Business ethics: The promise of neuroscience. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 144, 679–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, R.L.; Dias, Á.L.; Pereira, L.; Santos, J.; Miguel, I. The basis for a constructive relationship between management consultants and clients (SMEs). Bus. Theory Pract. 2020, 21, 666–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bakker, F.G.; Rasche, A.; Ponte, S. Multi-stakeholder initiatives on sustainability: A cross-disciplinary review and research agenda for business ethics. Bus. Ethics Q. 2019, 29, 343–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myung, E. Progress in Hospitality Ethics Research: A Review and Implications for Future Research. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2018, 19, 26–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaides, A. Ethical Hospitality Marketing, Brand-Boosting and Business Sustainability. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2018, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, G. Psychology and business ethics: A multi-level research agenda. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 165, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.E.; Laczniak, G.R.; Bowie, N.E.; Klein, T.A. Ethical Marketing: Basic Ethics in Action; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gaski, J. Does marketing ethics really have anything to say? A critical inventory of the literature. J. Bus. Ethics 1999, 18, 315–334. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, E. Ethical Debates in Marketing. In Contemporary Issues in Marketing and Consumer Behaviour; Butterworth-Heineman: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tallontire, A.; Rentsendorj, E.; Blowfield, M. Ethical Consumers and Ethical Trade: A Review of Current Literature; Natural Resources Institute: Greenwich, CT, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Idowu, S.O.; Capaldi, N.; Zu, L.; Gupta, A.D. Encyclopedia of Corporate Social Responsibility; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Carrigan, M.; Attalla, A. The myth of the ethical consumer-Do ethics matter in purchase behaviour? J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 560–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pride, W.M.; Ferrell, O. Marketing; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P.; Pridgen, M. Ethical and legal issues in marketing. In Advances in Marketing and Public Policy; Bloom, P.N., Ed.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1991; Volume 2, pp. 185–255. [Google Scholar]

- Whysall, P. Marketing ethics-An overview. Mark. Rev. 2000, 1, 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.D.; Vitell, A.A. General theory of marketing ethics. J. Macromark. 1986, 6, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalikis, J.; Fritzsche, D.J. Business ethics: A literature review with focus on marketing ethics. J. Bus. Ethics 1989, 8, 695–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.J. A contextualist proposal for the conceptualization and study of marketing ethics. J. Public Policy Mark. 1995, 14, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.D. The nature and scope of marketing. J. Mark. 1976, 40, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siham, B. Marketing Mix-An Area of Unethical Practices? Br. J. Mark. Stud. 2013, 1, 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sasu, C.; Pravat, G.C.; Luca, F.A. Ethics and Advertising. SEA Pract. Appl. Sci. 2015, 3, 513–518. [Google Scholar]

- Weeden, C. Ethical Tourism: An Opportunity for Competitive Advantage? J. Vacat. Mark. 2002, 8, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansing, P.; De Vries, P. Sustainable Tourism: Ethical Alternative or Marketing Ploy? J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 72, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Swanger, N. An industry-driven model of hospitality curriculum for programs housed in accredited colleges of business. J. Hosp. Tour. Educ. 2004, 16, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kincaid, C.S.; Baloglu, S.; Corsun, D. Modeling ethics: The impact of management actions on restaurant workers’ ethical optimism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, B. Hotel Managers Identify Ethical Problems: A Survey of their Concerns. Hosp. Rev. 2011, 29, 22–36. [Google Scholar]

- Holievac, I.A. Business ethics in tourism–As a dimension of TQM. Total Qual. Manag. 2008, 19, 1029–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, R. Hotel general managers’ perceptions of business ethics education: Implications for hospitality educators, professionals, and students. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2012, 11, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.-C.; Cheng, S.-S. Hospitality Ethics: Perspectives from Hotel Practitioners and Intern Students. J. Hosp. Tour. Educ. 2021, 33, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleverdon, R.; Kalisch, A. Fair Trade in Tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2000, 2, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B.W.; Burns, P.; Palmer, C. Tourism Research Methods: Integrating Theory with Practice; CABI Publishing: Manchester, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Yaman, H.R.; Gurel, E. Ethical ideologies of tourism marketers. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 470–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.Y.S.; Tsang, N.K. Perceptions of tourism and hotel management students on ethics in the workplace. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2013, 13, 228–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knani, M. Ethics in the Hospitality Industry: Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilikidou, I.; Delistavrou, A.; Sapountzisc, N. Customers’ Ethical Behaviour towards Hotels. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 9, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Donohoe, H.M.; Needham, R.D. Moving best practice forward: Delphi characteristics, advantages, potential problems, and solutions. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 11, 415–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avella, J.R. Delphi panels: Research design, procedures, advantages, and challenges. Int. J. Dr. Stud. 2016, 11, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thal, K.I.; Stacey, S.S.L.; George, B. Wellness tourism competences for curriculum development: A Delphi study. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2021, 21, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-C.; Sandford, B.A. The Delphi Technique: Making Sense of Consensus. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2007, 12, pdz9-th90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasson, F.; Keeney, S. Enhancing rigour in the Delphi technique research. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2011, 78, 1695–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuusi, O. The Delphi method. In How Do We Explore Our Futures? Methods of Futures Research? Acta Futura Fennica 10. The Finnish Society for Future Studies; Kuusi, O., Heinonen, S., Salminen, H., Eds.; Project Anticipation: Trento, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, C.A. The status and future of sport management: A Delphi study. J. Sport Manag. 2005, 19, 117–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, J.; Bobeva, M. A generic toolkit for the successful management of Delphi studies. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methodol. 2005, 3, 103–116. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).