Abstract

Researchers have studied open innovation by focusing primarily on big organizations. With digitization, the adoption of open innovation has become widespread, as there is broader access to cheaper and better information and communication technology. Private or public companies will also support individuals, or a group of individuals, to promote an innovative economy. Some countries also provide incubation opportunities and technical and financial support to encourage digital startups. This paper presents insights on the incubation program organized by one of the prominent centers in Qatar that incubate interested potential entrepreneurs to utilize open innovation for digital startups. The paper uses a qualitative analysis method on the data obtained from the interviews with the trainers (staff) of the center and the entrepreneurs who went through the incubation process. Four hypotheses were developed to understand various aspects of open innovation, the collaboration of startups, and the role of the incubation center. A nonparametric statistical test was used to assess the validity of the hypotheses. The results show that incubation and open innovation can contribute to digital startups. The paper concludes with suggested enhancements for incubation. This paper complements the literature by providing a study of open innovation in digital startups and introducing future research in this field.

1. Introduction

Organizations use the open innovation (OI) approach to acquire external knowledge, sources, and resources. The approach is adopted by smaller organizations and startups as well. For digital startups, OI can support gaining access to expertise, toolkits, and infrastructure with the collaborator. The success of digital startups can contribute to the digital economy [1]. Available funding and technological expertise should encourage startups through the government, venture capitalists, banks, or large companies. These digital startups also have access to incubation facilities [2,3]. Similarly, knowledge-sharing is essential to enhance innovative operations in incubation centers [4]. Various factors can lead to the success of these incubation programs to support the OI model.

This study was inspired by the activities of an incubation center for digital startups in Qatar. The center’s name is disguised here and will be referred to as CfDS. The center was established to help entrepreneurs transform related innovative ideas into digital transformation, big data, and e-commerce and smart solutions into valuable businesses. The center also offers startup expertise, professional guidance, and logistical and business services such as office space, business planning, training and education, and legal advice.

This paper will focus on two main research questions to assess the importance of OI practices within digital startups and the incubation center’s support for digital startups. The analysis described in this paper is based on nine startups: five that have already completed incubation and four that were in incubation during data collection. The research questions considered in this paper are:

RQ1: How do digital startups perceive and use OI models?

RQ2: How could incubation centers activate OI models to support startups?

The remainder of the document is structured as follows: In Section 2, there is a review of the standard practices, policies, barriers for OI, and incubation processes. In Section 3, details of the CfDS and data collection methodology are given. Data analysis is presented in Section 4. The insights and discussions of the results are presented in Section 5. Finally, the conclusion and suggestions for future research are provided in Section 6.

2. Literature Review

The success of business incubators depends on their ability to attract startups, business ventures, and new entrepreneurs. In this regard, the cooperation of the incubators with research and development institutes and universities is essential to obtain the benefits from OI [5]. The relevant literature has been reviewed in three different sections. Each section posits a hypothesis that will be tested in this study.

2.1. Open Innovation Policies and Barriers

The OI concept was initially started by large companies to introduce new ideas to the market [6]. OI models focus mainly on interactive knowledge processes within and outside the firm [7] through collaborations with external parties [8]. Although there might be a significant information asymmetry [9], collaboration can lead to a win-win situation in targeted areas, especially when internal integration [10,11] is considered. Startups, young ventures, and small and medium enterprises (SMEs) can take advantage of such a collaboration due to their agility [12,13].

Adoption of OI can be classified into three levels [14,15]: knowledge production focusing on research and development (R&D), financial support, education development, human capital professional training policies, and acquisition of talent; knowledge distribution focusing on protecting patent rights, enabling knowledge relocation with the acceleration of flows at a low cost, and knowledge consumption ensuring transparency. However, the adoption may require different incentives, processes, and outcomes [16]. There are some hurdles in collaboration due to managerial, technical, cultural, funds, and intellectual property (IP) rights [17].

Tsinopoulos et al. [18] also mentioned the necessity of collaboration to identify outside creativity. Collaboration also supports exchanging information [19] and benefiting from the collaborating company’s research [20].

Based on the above discussion, it can be deduced that the innovation process can benefit from many factors, such as the flow of information, sharing of expertise, and access to technology and funds. Therefore, the first hypothesis for testing in this study was formulated.

Hypothesis 01 (H01).

Startups are not confident of the value obtained from the collaboration with the large organization in an OI model.

Hypothesis 11 (H11).

Startup companies are confident of the value of collaboration with a large organization to benefit from an OI model.

2.2. Open Innovation and Entrepreneurship

OI focuses on developing entrepreneurship in organizations by successfully introducing new products to the market [21]. Malik and Wei [22] mentioned that a technology-based SME can develop a stronger market position by expanding its intellectual capital assets through its OI-based alliance with large companies. This alliance can help SMEs to become learning organizations and to create innovative products ([23,24]).

Entrepreneurs need autonomy and support as they are taking risks to enter a market [14,25]. Startups exist because of perceived inventive capacity, agility, entrepreneurship zeal, and a void of hierarchy. Therefore, early identification and support (if necessary) from the government can help them provide a presence in the marketplace [26]. Support can be provided through incubation centers or R&D in technology parks. It can also be provided in terms of education, research funds, liaising the entrepreneurs with research institutes and universities, commercialization, and subsidizing the cost of an IP transfer [27]. The focus should be on open access to data, support entering the marketplace, or creating their marketplace. Government support in multiple aspects becomes vital to creating entrepreneurship with startups and SMEs [28]. Thus, the second hypothesis was proposed as follows:

Hypothesis 02 (H02).

Entrepreneurs and startups cannot create the required marketplace for their innovation outcomes; therefore, the existing market is crucial as a valuable business platform.

Hypothesis 12 (H12).

Entrepreneurs and startups can create the required marketplace for their innovation outcomes; therefore, the existing market will not affect innovation ideas.

Organizations that own an IP may not use a portion of the IP. However, such a portion of the IP may provide substantial opportunities for entrepreneurs and startups to create new products. Therefore, the support for IP negotiation could also help entrepreneurs and startups. A study [29] conducted in Kenya showed a positive correlation between using portions of the IP and technology innovation centers or business incubators. Therefore, another hypothesis examined in this paper was to see if the current support for such a negotiation for releasing some part of the innovation is adequate [27].

Hypothesis 03 (H03).

The current support mechanism to negotiate the use of portions of running IP is not adequate to enable OI in digital startups.

Hypothesis 13 (H13).

The current support mechanism to negotiate the use of portions of running IP is adequate to enable OI in digital startups.

2.3. Enabling OI for Startups through Incubation

Incubation centers adopt different models to support new products and services. Among the two incubation centers in the UK and Finland, Kautonen et al. [30] found that the UK incubation center follows a model to stimulate incubated projects from high technology firms and university search. However, in Finland, the center follows another model that supports innovative ideas and startups [30]. Metrics such as access to finance, equipment, and skills by the incubation centers are recommended in [31] to measure business incubators’ effectiveness. The application of metrics by van der Spuy [32] on business incubators within the Northern Cape Province of South Africa showed that only one-third meet the benchmark, which might be considered a waste of government funding.

The comparison of two incubation centers in the USA and Poland for their services in pre-incubation and incubation periods was given in Wolniak et al. [33]. The study showed that clients are satisfied with the services provided by both centers in the pre-incubation, such as the help in engineering analysis and designing the invention details. However, they recommend increasing the number of sources providing services and advice to startup companies during incubation. The incubation period should also increase business management, accounting support, and legal assistance (for example, protecting the IP). Therefore, providing legal assistance becomes essential during the incubation stage to make the participants aware of the digital OI legal frameworks [34].

Digital startups work in a hyper-competitive environment [35]. As digital technology becomes more affordable, innovation may become obsolete. On the other hand, rapid growth can create speed for developing better products and services.

A research study compared several digital startups in Italy and proved that the startups that had access to business incubation programs avoided market failure [3]. Another study of incubation in four business incubators in Northern Sweden showed that the incubation process succeeds with support from the surrounding digital ecosystem [36]. Hamid and Khalid investigated the services provided by several business incubation centers in Pakistan [37]. The authors found that the performance of these centers is similar to that obtained from a government incubation program [37].

A research study [38] focused on knowledge sharing, creativity, and innovation dissemination to measure the effectiveness of business incubators in Saudi Arabia. The study proposed an assessment framework based on these factors, since the findings showed that knowledge sharing has a definite effect on incubators [38,39].

While incubation programs focus more on promoting disruptive ideas and conducting new businesses, acceleration programs focus on supporting the growth of an existing startup, which can come through R&D support [40,41]. Accordingly, incubation is essential, whether the business sector or the government provides it. Government support generally aims to develop capabilities and promote an innovative culture. Therefore, the following hypothesis was proposed.

Hypothesis 04 (H04).

Government support is indispensable to enable OI in digital startups.

Hypothesis 14 (H14).

Government support is not indispensable to enable OI in digital startups.

From the reviews above, it can be summarized that digital startups need to be provided with technical and business support where necessary. Avenues for the budding startups are essential to access incubation, innovative tools, initial funding, and access to expertise to show them the path to success. Creating an OI environment can spark collaboration, discussions, initiatives, and outcomes for successful digital startups. A recent study provided three main success factors for OI, namely examining OI strategies and activities by the startup company management, planning commercialization with the support of experts, and ensuring a smooth OI process [42]. It is noticed that some businesses may adopt acceleration to incubation due to their immediate market perception; however, it is helpful to support incubation efforts at the same time to prosper over the long term.

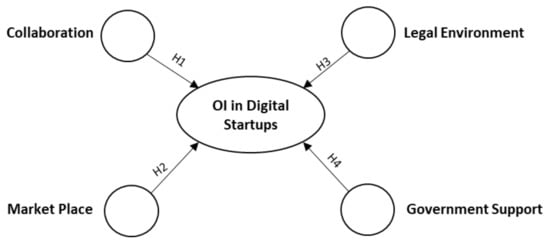

Figure 1 presents the relationships between the suggested hypotheses and the OI concept in startups. Lines in the figure represent the hypothesis, and circles represent the main elements for testing.

Figure 1.

The hypotheses and elements for OI and startups.

3. The Case of the Incubation Center for Digital Startups (CfDS)

Qatar, one of the fast-growing economies in the Middle East, is attracting more foreign direct investments in the Gulf region [43]. The country has adopted a national economic diversification strategy, one of which is to promote the digital economy [43]. The CfDS was established to boost information and communication technology (ICT) based on innovation through incubation and support.

The center offers incubation for about two years for each startup and offers an average investment of QAR 164,000 per year per startup. The CfDS provides administrative and logistic services, legal and accounting services, technology services, education and training, mentors, networking, and interns. Experts, business professionals, academics, and other partners of CfDS ensure that startup projects lead to innovative technical ideas. Potential extra funding is also made available through a local bank in the country.

The center provides the necessary guidance and logistical support for the startups at every stage. The actual incubation period is provided through “Startup Track”, where startups are supported for registration as a commercial company, providing office place, technical support, training, guidance, and mentoring. All services are provided to ensure the sustainability of startups in the marketplace.

4. Research Method

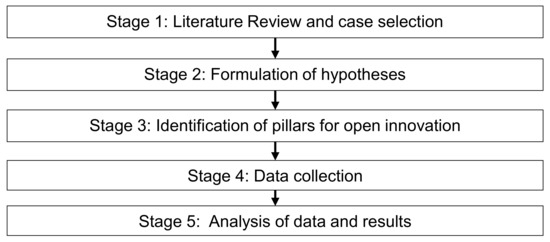

The research is conducted in five stages, as mentioned in Figure 2. The first two stages of the research have been covered in Section 1 and Section 2. The remaining stages will be discussed below.

Figure 2.

Research Method.

4.1. Identification of Knowledge Areas Affecting Open Innovation

Developing knowledge capabilities in different areas contain several elements that guide data collection to test the hypothesis. Table 1 shows the four knowledge areas and 23 elements considered in this study. The list of elements was generated based on the literature mentioned in the table. The first knowledge area is OI in firms, which contains five elements to measure the allocated R&D budget, startup IP knowledge, the possibility of their application, following standards, and benefiting from the collaboration. The second knowledge area concentrates on the government’s role in OI. Thirteen elements spanning funding, IPs, education, commercialization support, and other resource availabilities were considered. The marketplace is assumed as the third knowledge area, which is vital for knowledge migration, flexibility, and fair competition. The fourth knowledge area represents social resources and networks. Networking and social connections can open new opportunities for startups to connect with other countries, organizations, and professionals and to support their OI performance.

Table 1.

Knowledge areas and elements to enable OI in startups.

Table 1.

Knowledge areas and elements to enable OI in startups.

| S.N. | Knowledge Area and Elements | Element Descriptions | Literature Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge area 1: Open innovation in firms | |||

| 1 | Element 1.1 | The budget allocated for R&D | Bogers et al. [16] |

| 2 | Element 1.2 | Startup IP knowledge and application | Bogers et al. [16] |

| 3 | Element 1.3 | Following standards | Bogers et al. [16] |

| 4 | Element 1.4 | Supporting OI through collaboration and interaction | Cheng and Chen [8] |

| 5 | Element 1.5 | Developing employees’ skills | Bogers et al. [16] |

| Knowledge area 2: Government role in OI | |||

| 6 | Element 2.1 | Government has intellectual property laws and patent rights laws | Malik and Wei [22] |

| 7 | Element 2.2 | Government support for entrepreneurship | Fabricio Jr et al. [25] |

| 8 | Element 2.3 | Government financial support for startups | Bogers et al. [16] |

| 9 | Element 2.4 | Government financial support for R&D | Chesbrough et al. [27] |

| 10 | Element 2.5 | Government focus on providing skills to the incubated companies | Galiyeva and Fuschi [31] |

| 11 | Element 2.6 | Government supports the formation of derived companies from large organizations to commercialize research discoveries | Yun et al. [14] |

| 12 | Element 2.7 | Government is benefitting from specialized personnel as innovation resources | De Jong et al. [28] |

| 13 | Element 2.8 | Government allocates resources efficiently | Galiyeva and Fuschi [31] |

| 14 | Element 2.9 | Education system encourages general stimulation for problems | Chesbrough et al. [27], Bogers et al. [16] |

| 15 | Element 2.10 | Education system encourages entrepreneurship Education | Chesbrough et al. [27], Bogers et al. [16] |

| 16 | Element 2.11 | Government accelerates the publication of government data whenever possible. | Chesbrough et al. [27] |

| 17 | Element 2.12 | Utilize OI in government procurement. | Juarez et al. [10] |

| 18 | Element 2.13 | Government promotes the commercial application of technologies developed for it. | Yun et al. [14] |

| Knowledge area 3: Market Place | |||

| 19 | Element 3.1 | Qatar technology market is flexible | Buss and Peukert [20] |

| 20 | Element 3.2 | Qatar’s market encourages knowledge migration. | Inauen and Schenker-Wicki [7,14,15,19] |

| 21 | Element 3.3 | There is competition in different sectors in the Qatar market. | Usman and Vanhaverbeke [13] |

| Knowledge area 4: Social resources and networks. | |||

| 22 | Element 4.1 | Social resources (sites and communities, tools, and platforms such as Creative Commons) are evolved for OI. | Hossain [24] |

| 23 | Element 4.2 | Social networks are used to enlarge knowledge exploration | Hossain [24] |

4.2. Data Collection Method

This paper used data collection and qualitative research methods based on [44,45]. The responses were collected from the CfDS through structured interviews with startup companies supported earlier (called graduated) by the center and those currently being incubated (called incubated). Questions were arranged based on the recommendation given in [46]. The questions were definite, and the participant expressed their level of agreement, which was rated on the Likert scale. A sample of the structured interview scripts is provided in Appendix A using statements (ST) to obtain the answer to each element. For example, ST4 refers to the interview questions related to Element 1.4 and ST23 refers to the interview questions related to Element 4.2.

The elements mentioned in Table 2 are mapped to the hypothesis, as shown in Table 3. Some statements, such as ST5 and ST18, were not used to test the hypothesis; they were added to understand the status of digital startups and the surrounding environment. ST5 was used to understand the internal environment of the startup company in terms of employee development plans, thus the support of innovation within the company. Another example is ST18, where startups’ perception of government efforts in commercializing was measured for a specific software developed by a startup company for a certain entity’s use. This statement gives insight into the commercialization opportunities and the government’s support for the OI concept.

Table 2.

Mapping the elements with hypotheses and interview guide statements.

Table 3.

Critical values for sign test r* α.

Data were collected from digital startups either incubated or graduated from CfDS. Nine digital startup companies participated in this study. At the time of data collection (June–August 2020), there were 14 incubated digital startups and 58 graduated startups. The scope of these companies varies between electronic educational portals, professional training portals, real estate, e-commerce, and children’s mobile learning and skill development applications.

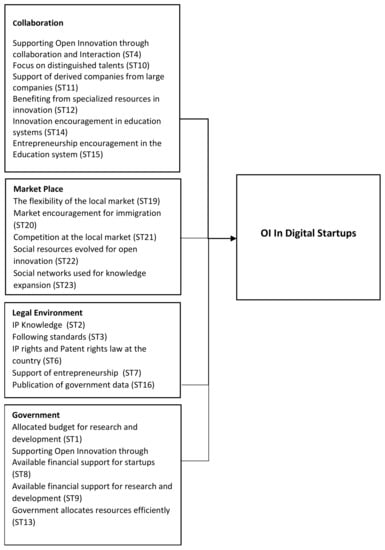

Figure 3 shows four main parts considered to elicit the answer through the interviews, and each of them is related to the use of OI in digital startups. Each statement representing the area is also provided in the figure.

Figure 3.

Survey questions framework.

5. Analysis and Results

The data were collected from the startup coordinator of the center, and nine companies incubated or graduated from the CfDS. The normality of the data was tested by plotting responses for each hypothesis statement. The Likert scale (5 = strongly agree and 1 = strongly disagree) was used for responses. The median for each record was calculated to prepare the data for the test. Since the sample size was small and normal distribution could not be approved, the nonparametric test was used as advised in [47,48]. Information technology also uses nonparametric tests to study machine learning regression algorithms [49] and to analyze surveys in the market structure industry [50]. The sign test was the nonparametric test used in this study to test the hypothesis, using the median of the tested population. The main benefit of this test is its simplicity and applicability to any sample, whether it is continuous, discrete, symmetrical, or non-symmetrical [51]. The sign test has no conditions on the sample size. The sign test is performed on a random sample X1…….Xn from a population, where a critical value r*will be used to test the null hypothesis, signs of each value are determined by subtracting the sample value Xn (V) from the median of the values µ0. The sign test examines the minimum between negative and positive signs; if this number is less than the critical value, the null hypothesis will be rejected because there is a substantial inconsistency between negative and positive signs in the sample [51]. Accordingly, the mean for each statement’s values is calculated to analyze the data. Given the notation (V), the median value for the V values of statements representing the hypothesis is calculated as µ0. The median µ0 is subtracted from each mean value of the statement’s responses (V-µ0), positive signs r+ and negative signs r- are counted, and the minimum value is compared to r*. The nonparametric test is performed with α = 0.05.

Each hypothesis was connected to several statements and was analyzed through the sign test. The tests were performed separately with α = 0.05. The number of records n equals the number of statements used to test each hypothesis. The letter r* refers to the critical value for a specific significance level of significance α and was identified based on Table 3; r* values were calculated using the statistical formula to determine the rejection region. The column of the table represents the number of records (n). The first row provides critical values of r* α at the corresponding α. As the number of records in testing each hypothesis did not exceed ten records, values of r* for an α were given until n = 10.

Table 4 provides the results of the sign test for all the hypotheses. As mentioned earlier, in Table 4, graduated refers to startup companies that completed two years of incubation and started to run their startups independently in the marketplace. Incubated refers to startup companies that are still receiving full support from CfDS.

Table 4.

Hypothesis sign test results.

Note: 0 values have no sign and are considered ties; they are not counted for the sign test.

For each hypothesis testing, the following steps were completed:

- The mean response value of each statement was calculated and denoted as V.

- The median µ0 was calculated for the Means V for the statements representing the hypothesis.

- The median µ0 was subtracted from each mean value (V-µ0) to obtain a sign (r+, r−) as suggested in [52].

- The count of positive signs, r+, and negative sign, r−, was determined, and rmin was determined by finding the minimum (r+, r−).

- r* was determined from Table 3 based on α = 0.05 and n, the number of statements representing the hypothesis.

- decision was made based on the condition that if , then the null hypothesis is rejected.

Table 5 presents the result of hypothesis testing and shows that none of the null hypotheses can be rejected.

Table 5.

Hypothesis testing results.

The analysis shows that H01 was validated, meaning that startup companies perceive difficulties collaborating for OI with large organizations. Complex collaboration could be because of startup companies’ perception of large organizations and project initiation procedures. Similarly, Massimo et al. [53] mentioned the need for collaborations with large organizations to increase innovation in their study. They found that small businesses with more networks and collaborations with larger organizations have more innovations than others with limited networks. Open innovation in startups requires collaboration with outside parties, including large organizations, universities, experts, and innovative talents. Having specialized personnel and innovation resources and encouraging entrepreneurship in the education system will enable OI in startups.

For hypothesis H02, technology markets are crucial for OI as a valuable source of entrepreneurs’ business insights The analysis presented the critical role of the technology market’s flexibility, knowledge migration, competition, and social networks to enable OI in startups since flexible markets will create the demand for innovations, acquire talents, and communicate with experts. Social networks will open channels for marketing new products and services widely. The found results are consistent with a previous study’s results by Nguyen et al. [54].

For hypothesis H03, the current support mechanism to negotiate the utilization of a portion of IPs is insufficient to enable OI in digital startups. The analysis showed that we cannot reject the hypothesis. The mechanism to negotiate IP needs to be developed to allow a startup to adopt OI. It is essential to support startups with knowledge of IP, patent rights laws, and entrepreneurship guidelines. Boudreau et al. [55] mentioned that IP rights are not clear for digital innovations due to the unique structure of the resulting product that will vary according to the relevant industry.

For hypothesis H04, the results showed that government support is essential to enable OI. The support can be provided by allocating a budget for R&D within the startup company or as support of CfDS. In addition, the financial support for the startups at the establishment phase and through the firm’s life cycle is vital to sustaining their market position. This result is consistent with earlier studies by Murati-Leka and Fetai [56], that government support is essential when firms introduce new products. The result does not depend on the size of the firm. From the analysis, the following points can be derived:

- Startups recognize the value of investing in R&D to establish their position in the marketplace. Adequate training and mentoring are highlighted throughout their time in the incubation center.

- Startups had information on the laws and policies related to IP, and more than half of them are aware of the opportunity with these laws and policies for their business. More effort is needed to enable digital startups to support them in protecting their innovation (such as software applications). Thus, startups perceive the need to apply OI models.

- There is government funding available to initiate companies, and it is also mentioned that research-related funds are disbursed through the National Research Funds. When working in an OI context, continuous technical expertise is needed until the startup is independent. This type of support can help startups develop new products and services for the broader market.

- Entrepreneurship should be one of the core subjects in education. It should be started right from the primary level of education. If this can be done, a critical mass of entrepreneurs would be developing to take Qatar’s startup lead.

- The technology market is flexible in Qatar, and it encourages the commercialization of innovative ideas. Moreover, knowledge migrates to Qatar’s market since it is considered a rich environment for development, especially with the competition within the local digital market. Sharing motivating factors and hurdles in cross-learning on applications can help increase the likelihood of success.

- Building on social resources, including communities, platforms, and tools, would support OI’s further adoption in digital startups.

6. Discussion

Developing digital startups can support the digitization of many services and boost economic activities. Such startups usually arise when there is an abundance of the market to absorb their product or consistent support that facilitates OI and learning and funding resources. This paper focused on understanding the type and the impact of the support provided for digital startups in an OI context.

The study of the responses showed that the establishment of the CfDS in Qatar is in line with achieving the country’s national strategic vision and aim for globalization. The center is an investment from the government. The results were precise that the provided services to startups supported them, to a great extent, to develop their ideas for commercialization. In terms of startups’ perception of the OI model presented in RQ1, it is based on collaboration, knowledge sharing, and research and development partnerships with research institutes. This perception is in line with known OI Models.

The hypothesis testing provided the following main insights to enable OI in startup companies answering the research question RQ2:

- The CfDS and other science and technology organizations collaborate to provide an incubation hub and business development base. The center collaborates with the government to organize workshops to encourage entrepreneurs to list their digital businesses on Qatar’s “Theqa” e-commerce platform, which can be accessed through the link https://www.theqa.qa (accessed on 1 March 2022) The website aims to improve Qatar’s e-commerce and to grow local online purchases by enabling people and residents to trust Qatar’s e-commerce ecosystem. The successful collaboration of the incubation centers with the universities, other research centers, and government entities can support startups [57]. The collaboration may be expanded to more national and international universities and organizations to gain expertise worldwide to enable the sustainable growth of the startups [58].

- As mentioned earlier, regulations play an essential role in facilitating OI. It is highly recommended to raise awareness in startup companies with the available rules and regulations and to enhance the negotiation mechanisms to apply IP laws to digital startups [59]. These mechanisms will allow registering them under the rights holder, protecting them by law from duplication or usage without official approval from the right holder. In addition, it dramatically protects the work of the startups. It is recommended to initiate IP licensing standards and related trade, create patent pools, and develop open-source models for different sectors, specifically the ICT sector [60]. Intellectual property contracts are essential when acquiring a partnership with other organizations, where patents, trademarks, copyrights, design rights, and technical and commercial information (trade secrets) become essential [55]. An enhancement of these mechanisms may attract more digital startups to start in Qatar’s market and create various digital industries.

- Finally, government support is essential for startups, including consultancy and advisory support such as product compatibility and digital safety for digital transactions. The CfDS encourages digital startups to adapt to the latest technology trends and standards, including cloud computing, the Internet of Things (IoT), big data analysis, machine learning, cybersecurity, e-commerce, smart city solutions, and blockchain. The government’s financial support to increase R&D investment in startup companies is crucial to allow access to state-of-the-art technologies and develop innovative solutions in the marketplace. This support will help sustain startup companies and guarantee market diversity and economic growth [61]. The studies of digital startups and incubation centers are limited in the literature; accordingly, this paper contributes to the knowledge by examining how OI could benefit digital startups.

7. Conclusions and Future Research Directions

Digital startups can be a catalyst for enhancing the digital economy in a country, thus improving the cost and resources required for generating national income. They also support enhancing the capability of entrepreneurs and generating employment.

This paper focused on the promotion of digital startups through OI. The study focused on four main knowledge areas mentioned in the reviewed literature to promote OI. These areas were analyzed as hypotheses in this paper. Various opportunities and elements related to OI have been provided in the paper.

The first research question focused on startups’ perceptions and usage of OI models. This question was tested using hypothesis H1, related to collaboration activities. The research results indicated that startups acknowledge the value of R&D investments and recognize the importance of collaboration, training, and mentoring throughout the business stages [62]. Thus, OI models will foster the R&D opportunities and increase training and mentoring opportunities.

The second research question focused on the methods that incubation centers use to activate OI models to support startups. This question was tested using the hypotheses H2, H3, and H4. This study showed different activities to be initiated to promote OI. The activities could include collaboration with science and technology and research organizations and a knowledge-sharing culture with different institutions and startups [63]. Raising startup companies’ awareness of the current laws and regulations related to digital innovations and providing support for startup companies, such as consultancy services and advisory support and the latest technologies training and education. This kind of support will positively influence digital startups [64]. Startups’ leadership training is essential to support OI in their businesses [65].

The analysis showed that enabling OI in startups requires collaboration with outside parties, including organizations, universities, experts, and innovative talents. This collaboration will accelerate idea development for commercial products in the marketplace. Similar results were concluded by Cavallo et al. [61]. In addition to collaboration having flexible technology markets, markets that encourage knowledge migration and competitiveness are crucial for OI as valuable business insights for entrepreneurs. The analysis also highlights the importance of social networking to disseminate the developed products and enlarge knowledge exploration.

A legal environment with enhanced policies and guidelines will enable OI in digital startups. Some enhancements in the present legal provisions may be necessary to support digital startups. Funding startups can be secured through other government or private entities as well. Providing logistical and consultancy services and supporting R&D by connecting universities and experts are also considered valuable.

Incubation centers’ management and leadership can benefit from this study to enhance their services. Initiating or emphasizing IP laws and regulations will support OI in coordination with other legal institutions and governmental bodies.

We believe that this paper is the first to consider OI in digital startups in the Qatari context. The paper focused on the effectiveness of the incubation centers in promoting digital companies in Qatar.

Future Research Directions

This paper used an interview method to elicit ideas and to develop contribution, which can limit this study. Although this is one of the methods proposed in the literature, it could have been more representative if more startups could have been involved.

This study considered digital startups; therefore, a cross-section examination of the factors for self-initiated startups and incubated startups can provide more insight into enhancing the CfDS program. Findings from such studies could also be correlated with the business-led incubation or incubation programs in different countries.

Another study that can be useful is investigating the motivators and barriers to promoting digital startups through OI. Although the statements mentioned in this study proxy those motivators or barriers, a direct study will give the perspectives to develop policies directed towards enhancing the OI model and incubation model adopted in the country.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A.S., M.E. and S.A.; Formal analysis, R.A.S.; Methodology, R.A.S., S.P. and M.A.A.; Supervision, S.P. and M.A.A.; Writing—Original draft, R.A.S.; Writing—Review & editing, S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data is collected specifically for this study.

Acknowledgments

The initial draft of this paper was submitted as partial fulfillment of the graduate course Innovation and Technology Management offered at the College of Engineering, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Sample of structured interview statements and responses.

Table A1.

Sample of structured interview statements and responses.

| Knowledge Area 1 | Statements Used for the Interview | ST | Transcript of Responses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Element 1.1 | Your company has a budget allocated for research and development | ST1 | The startup coordinator agreed with this statement and discussed how the center communicates with other entities to secure R&D funds. Two digital startups in the incubation stage disagreed since they were at their initial stage, and all their funds were allocated to the establishment and operational activities. Two incubation startups in the Incubation stage and two in the graduation stage agreed, and a small amount is allocated to R&D due to its importance. One graduated startup had a neutral response, while two graduated startups agreed strongly, and they have the proper amount of funds allocated to R&D |

| Element 1.2 | Your company has a clear and strong IP system | ST2 | The startup coordinator and one graduated startup had a neutral answer since they could not judge the clarity of the IP system. In contrast, two incubated startups and one graduated disagreed and believed that the IP system was not clear for them. Two graduated startups and one incubated strongly agreed with the statement since they are aware of the current IP system in the country. One incubated startup agreed since the IP system is available. They need to investigate more about it. |

| Element 1.3 | Your company follows strong standards (in terms of organization and technology) | ST3 | The startup coordinator, four graduate startups, and two incubated startups confirmed their agreement using IT standards and organizational standards. One incubated and one graduated startup have strong standards, and they strongly agree with the statement. |

| Element 1.4 | Your company supports user innovation and interaction | ST4 | Since startup companies are generally based on innovation, user innovation and interaction are the business’s sole. All incubated startups and two graduates rated their support, while three graduated startups strongly agreed. |

| Element 1.5 | Your company develops employee’s skills | ST5 | Employee development is essential to foster innovation, as per graduated startups 1.3. Three graduated and incubated startups confirmed that they develop employee skills and strongly agreed with the statement. They have implemented programs to develop employees’ skills. The coordinator had a neutral response on this aspect, as it depends on a startup’s requirements. One startup disagreed with the statement, as their company promotes and depends on employee self-development. |

References

- Satalkina, L.; Steiner, G. Digital Entrepreneurship and its Role in Innovation Systems: A Systematic Literature Review as a Basis for Future Research Avenues for Sustainable Transitions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano, D.; Preto, M.T.; Amaral, M. University-industry linkage through business incubation: A case study of the IPN incubator in Portugal. In The Role of Knowledge Transfer in Open Innovation; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 223–244. [Google Scholar]

- Gagliardo, E.D.; Gobbo, G.; Papi, L.; Bigoni, M. The effectiveness of incubation programs in startup development. Riv. Ital. Ragioneria Econ. Aziend. 2017, 5–8, 225–239. [Google Scholar]

- Othman, F.A.A.; Sohaib, O. Enhancing Innovative Capability and Sustainability of Saudi Firms. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitão, J.; Pereira, D.; Gonçalves, Â. Business Incubators, Accelerators, and Performance of Technology-Based Ventures: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.W. The era of open innovation. Manag. Innov. Chang. 2006, 127, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Inauen, M.; Schenker-Wicki, A. Fostering radical innovations with open innovation. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2012, 15, 212–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.C.; Chen, J. Breakthrough innovation: The roles of dynamic innovation capabilities and open innovation activities. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2013, 28, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groote, J.K.; Backmann, J. Initiating open innovation collaborations between incumbents and startups: How can david and goliath get along? Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2020, 24, 2050011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez-Juárez, L.E.; Gallardo-Vázquez, D.; Ramos-Escobar, E.A. CSR and the Supply Chain: Effects on the Results of SMEs. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, J.; Ding, Y. Analysis of the relationship between open innovation, knowledge management capability and dual innovation. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2019, 32, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Kailer, N.; Dorfer, J.; Jones, P. Open innovation in (young) SMEs. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2019, 21, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Vanhaverbeke, W. How startups successfully organize and manage open innovation with large companies. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2017, 20, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.J.; Won, D.; Hwang, B.; Kang, J.; Kim, D. Analysing and simulating the effects of open innovation policies: Application of the results to Cambodia. Sci. Public Policy 2015, 42, 743–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.J. Open Innovation Policy in National Innovation System. In Business Model Design Compass; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bogers, M.; Zobel, A.-K.; Afuah, A.; Almirall, E.; Brunswicker, S.; Dahlander, L.; Frederiksen, L.; Gawer, A.; Gruber, M.; Haefliger, S.; et al. The open innovation research landscape: Established perspectives and emerging themes across different levels of analysis. Ind. Innov. 2017, 24, 8–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, L.S.; Echeveste, M.E.; Cortimiglia, M.N. Critical success factors for open innovation implementation. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2018, 31, 1283–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsinopoulos, C.; Sousa, C.M.P.; Yan, J. Process Innovation: Open Innovation and the Moderating Role of the Motivation to Achieve Legitimacy. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2017, 35, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, E.W.K. Acquiring knowledge by foreign partners from international joint ventures in a transition economy: Learning-by-doing and learning myopia. Strat. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 835–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, P.; Peukert, C. R&D outsourcing and intellectual property infringement. Res. Policy 2015, 44, 977–989. [Google Scholar]

- Spithoven, A.; Vanhaverbeke, W.; Roijakkers, N. Open innovation practices in SMEs and large enterprises. Small Bus. Econ. 2013, 41, 537–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, K.; Wei, J. How external partnering enhances innovation: Evidence from Chinese technology-based SMEs. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2011, 23, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, D. Next generation entrepreneur: Innovation strategy through Web 2.0 technologies in SMEs. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2013, 25, 891–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. A review of literature on open innovation in small and medium-sized enterprises. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2015, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, E.G.; Sugano, J.Y. Entrepreneurial orientation and open innovation in brazilian startups: A multicase study. Interações 2016, 17, 448–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de S. Fabrício, R., Jr.; da Silva, F.R.; Simões, E.; Gale-gale, N.V.; Akabane, G.K. Strengthening of Open Innovation Model: Using startups and technology parks. IFAC-Pap. Online 2015, 48, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.; Vanhaverbeke, W.; Bakici, T.; Lopez-Vega, H. Open Innovation and Public Policy in Europe; Science Business Publishing Ltd.: Brussels branch, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong, J.P.; Kalvet, T.; Vanhaverbeke, W. Exploring a theoretical framework to structure the public policy implications of open innovation. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2010, 22, 877–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugasi, S.O.; Odhiambo, M.A. Implementation of Technology and Innovation Support Centers (TISCs) in Kenya: Challenges and opportunities. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautonen, M.; Pugh, R.; Raunio, M. Transformation of regional innovation policies: From ‘traditional’ to ‘next generation’ models of Incubation. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 25, 620–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Galiyeva, N.; Fuschi, D.L. A research proposal for measuring the effectiveness of business incubators. J. Organ. Stud. Innov. 2018, 5, 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- van der Spuy, S.J.H. The state of business incubation in the Northern Cape: A service spectrum perspective. South. Afr. J. Entrep. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolniak, R.; Grebski, M.E.; Skotnicka-Zasadzień, B. Comparative Analysis of the Level of Satisfaction with the Services Received at the Business Incubators (Hazleton, PA, USA and Gliwice, Poland). Sustainability 2019, 11, 2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, R.; Wang, H. A systematic literature review of open innovation in the public sector: Comparing barriers and governance strategies of digital and non-digital open innovation. Public Manag. Rev. 2020, 24, 489–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, S.D.; Påske, N.; Rodil, L. Managing Ambidexterity in Startups Pursuing Digital Innovation. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2019, 44, 273–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankevich, V.; Holmström, J. Gateways to Digital Entrepreneurship: Investigating the Organizing Logics for Digital Startups. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 2016, p. 13995. [Google Scholar]

- Hamid, N.; Khalid, F. Entrepreneurship and Innovation in the Digital Economy. Lahore J. Econ. 2016, 21, 273–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binsawad, M.; Sohaib, O.; Hawryszkiewycz, I. Factors impacting technology business incubator performance. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2019, 23, 1950007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binsawad, M.; Sohaib, O.; Hawryszkiewycz, I. Knowledge-Sharing in Technology Business Incubator. In Information Systems Development: Advances in Methods, Tools, and Management; Isd2017 Proceedings; Paspallis, N., Raspopoulos, M., Barry, C., Lang, M., Linger, H., Schneider, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, P.; Richter, N.; Schildhauer, T. Open Innovation with digital startups using Corporate Accelerators—A review of the current state of research. Z. Polit. (ZPB) Policy Advice Political Consult. 2015, 7, 152–159. [Google Scholar]

- de Carvalho, A.C.C.C. Digital Startups Accelerators: Characteristics and Evolution Trends. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.-C.; Phillips, F.; Yang, C. Bridging innovation and commercialization to create value: An open innovation study. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 123, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, M.; Joseph, R. Qatar Emerging as the Most Attractive FDI Destination in the GCC. Int. J. Econ. Financ. 2016, 8, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, G.A. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qual. Res. J. 2009, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, J.; Macve, R.; Struyven, G. Qualitative research: Experiences in using semi-structured interviews. In The Real Life Guide to Accounting Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 339–357. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, R.; Samaranayaka, A.; Cameron, C. Parametric vs. nonparametric statistical methods: Which is better, and why? N. Z. Med. Stud. J. 2020, 30, 61–62. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, W.; Jeong, M.; Jeong, K. Theoretical comparative study of t tests and nonparametric tests for final status surveys of MARSSIM at decommissioning sites. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2020, 135, 106945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trawiński, B.; Smętek, M.; Telec, Z.; Lasota, T. Nonparametric statistical analysis for multiple comparison of machine learning regression algorithms. Int. J. Appl. Math. Comput. Sci. 2012, 22, 867–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashenfelter, O.; Sullivan, D. Nonparametric Tests of Market Structure: An Application to the Cigarette Industry. J. Ind. Econ. 1987, 35, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzegorzewski, P.; Śpiewak, M. The sign test and the signed-rank test for interval-valued data. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2019, 34, 2122–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.C.; Runger, G.C. Applied Statistics and Probability for Engineers, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 207–219. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, M.G.; Laursen, K.; Magnusson, M.; Rossi-Lamastra, C. Introduction: Small Business and Networked Innovation: Organizational and Managerial Challenges. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2012, 50, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.; Nguyen, P.; Do, H. The effects of entrepreneurial orientation, social media, managerial ties on firm performance: Evidence from Vietnamese SMEs. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2022, 6, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreau, K.J.; Jeppesen, L.B.; Miric, M. Profiting from digital innovation: Patents, copyright and performance. Res. Policy 2022, 51, 104477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murati-Leka, H.; Fetai, B. Government and innovation performance: Evidence from the ICT enterprising community. J. Enterprising Commun. People Places Glob. Econ. 2022. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, M.; Grimaldi, M.; Cricelli, L. Benefits and costs of open innovation: The BeCO framework. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2018, 31, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellnhofer, K. Entrepreneurial alertness toward responsible research and innovation: Digital technology makes the psychological heart of entrepreneurship pound. Technovation 2021, 102384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagedoorn, J.; Zobel, A.-K. The role of contracts and intellectual property rights in open innovation. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2015, 27, 1050–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ahmed, N.; Khan, S.A.Q.A.; Naz, S. Role of Business Incubators as a Tool for Entrepreneurship Development: The Mediating and Moderating Role of Business Start-up and Government Regulations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochleitner, F.P.; Arbussà, A.; Coenders, G. Inbound open innovation in SMEs: Indicators, non-financial outcomes, and entry-timing. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2017, 29, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Sarto, N.; Cazares, C.C.; Di Minin, A. Startup accelerators as an open environment: The impact on startups’ innovative performance. Technovation 2022, 113, 102425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, J.; Hawryszkiewycz, I.; Sohaib, O. Deriving High-Performance Knowledge Sharing Culture (HPKSC): A Firm Performance & Innovation Capabilities Perspective; Association of Information Systems: Tokyo, Japan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Kang, K.; Sohaib, O. Investigating factors affecting Chinese tertiary students’ online-startup motivation based on the COM-B behaviour changing theory. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, G.; Dooley, L.; Bogue, J. Open innovation within high-tech SMEs: A study of the entrepreneurial founder’s influence on open innovation practices. Technovation 2021, 103, 102232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, A.; Burgers, H.; Ghezzi, A.; van de Vrande, V. The evolving nature of open innovation governance: A study of a digital platform development in collaboration with a big science centre. Technovation 2021, 102370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).