Abstract

Although they are one of the richest expressions of cultural and landscape heritage, gardens are at the same time one of the most delicate. The preservation and protection of these landscapes are based on what we know of them from the inventories which, in the particular case of historic gardens, have increased since the 1980s, as recommended by the Florence Charter. Portugal has a vast and varied range of historic gardens defined as original and unique. The concern to protect them resulted in lists and inventories being drawn up over time, prompted by academic and institutional initiatives. This article proposes to analyze the inventories of Portuguese historic gardens, specifically in terms of their main characteristics, content, achievements and drawbacks, and to discuss their effectiveness. Twelve inventories were considered. The information was collected from several sources and organized in databases, which were then sampled for a content analysis. The findings show that each study unequivocally added to knowledge about Portuguese landscape art, but also revealed important structural weaknesses. These were found in the different approaches and data standards used and in the information itself, which was often incomplete and was not updated. In addition, information tended to be scattered and there was a lack of interaction between preservation tools. This led to the conclusion that this task is far from being completed and fully effective. The present analysis could provide useful insights and be a starting point to trigger discussion among garden heritage professionals and organizations about centralizing the information on gardens, and to combine efforts to plug the gaps in it, so that the inventory can play an effective part in the sustainable maintenance, management and safeguarding of these assets.

1. Introduction

Gardens are part of the cultural landscape of any civilization and society and reflect the culture, identity and history of a people [1,2]. Since it is composed of living plant material, a garden is a dynamic and constantly changing environment where different types of time (ecological, social and subjective) are brought together and interact [3], thus transforming this space throughout the infinite daily, monthly or annual life cycles [4]. A garden therefore becomes an unfinished work [5] and one that is necessarily ephemeral [6]. This dynamic transformation leads Sales [7] to say that a garden is not an object, but rather a process undergoing constant development and decomposition. As change in the landscape is unavoidable, the function of management is to be able to incorporate this change into the policies of preserving the values of the place. The first step in the process leading to the preservation and protection of cultural landscapes is knowing about their existence and their characteristics.

Gardens are thus one of the richest, but also the most delicate, expressions of cultural and landscape heritage [8,9]. This is especially true of historic gardens, because of what they represent, which should be understood and preserved. The inventory is the first instrument in the process that leads to the safeguarding of the cultural heritage, as it allows the recognition of its existence. According to Meyers [10] (p. 102), “This principle makes inventories an essential tool for cultural heritage management in all of its various aspects”. The author [10] points out that inventories are essential to protect heritage from various constraints, both human and natural, to contribute to determine intervention priorities and to enable and provide a broader understanding and appreciation of, and public engagement with such places and their preservation. As such, it has been a constant premise of several documents on heritage conservation. Under the Principles for the Recording of Monuments, Groups of Buildings and Sites ratified by the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), it is assumed that recording is one of the principal ways to give meaning to, and to understand, define and recognize the values of cultural heritage [11], and so promoting its effectiveness is a vital tool for sustainable heritage management [10].

Therefore, following this line of reflection, cataloguing historic gardens is a key element in protecting and safeguarding them; it is the first step in identifying, quantifying, and publicizing them and their value and importance, and it is also an essential tool to support decision making about their oversight and recovery [9]. However, the task of protecting and safeguarding such a delicate cultural heritage is hampered when the full legacy is not properly known. This handicap derives from the length of time during which gardens of historical interest were not taken seriously and only given scant attention in discussions about heritage [12]. The recognition process for historic gardens as part of the cultural heritage took a long time. It is in a broader framework of the need to protect heritage that historic gardens emerge, albeit largely implicitly until the Florence Charter specifically focused on historic gardens.

The Portuguese Garden perfectly expresses the idea of a garden presented at the start, that is “a reflection of the culture, identity and history of a people”, because it has cultural features that are typically the result of particular circumstances in territorial, historical, cultural, political, religious, economic and social terms [8,13]. These sites represent an invaluable heritage and cultural value, one that is crucial for understanding Portuguese culture and for preserving national memory and identity. Therefore, the knowledge provided by an inventory is extremely important. However, in Portugal, historical gardens have never been a major interest, much less have they had any particular attention paid to them by the competent legislative and administrative authorities, at least in comparison with other forms of cultural heritage [14]. Proof of this are the many gardens that have been disappearing due to new urban needs, as well as those that have been undermined and lost their original historical and artistic character because of unregulated changes [8,14,15,16]. Additionally, since the vast majority of them are private property, closed to the public and often abandoned, cataloguing is not an easy task [9]. Ignorance of their existence and/or their real value have fueled this saga, and impoverished the country in terms of its heritage of historic gardens.

In Portugal, it was mainly in the academic world that an interest in historical gardens, in learning about them and protecting them, manifested itself most clearly and fruitfully, resulting in some listings and inventories. However, state institutions linked both to the management and preservation of heritage and to the tourism sector have also been embracing this theme in recent decades. They have achieved this through partnerships and protocols with academia, which have led to more studies and inventories being carried out on landscape art. Their purpose is not only to remedy the previous lack of knowledge about this heritage, but also to make it accessible to everyone, at home and abroad.

Constant references to the inventories of historic gardens and their authors were made in the various studies on gardens. However, there is a lack of general knowledge about those inventories and the information contained in them, since they have never been subjected to a more specific analysis in evolutionary and comparative terms, nor was their effectiveness discussed. That raised three key research questions that guided this work: (i) what inventories of historic gardens exist in Portugal; (ii) what are their characteristics, what kind of information do they include, where/how are they available; and (iii) what constraints do they present with negative implications for the effective and sustainable management of this heritage. This paper proposes to analyze the inventories of historic gardens in Portugal over time, and answer the above questions. It will also look at the purposes and methodological process whenever the level of available information permits.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Historic Gardens as Cultural Landscapes

Cultural landscapes are realities anchored in a long history of complex interaction between humans and nature [17]. Through their actions, humans have shaped the landscape, and the geographic and natural resources have in turn shaped the history and life of human societies. This means that nature and humans are the two most important factors in determining the character of landscapes. They can then provide information about the relationships established over time between societies and the natural environment, and can therefore contribute to the understanding of history, science, anthropology, technique, literature, among the other foundations of society. It is from this perspective that it makes sense to establish landscapes as cultural heritage, insofar as they are goods in constant evolution that are inherited, used and bequeathed to future generations [18].

As a result of this interaction, landscape consists of both natural and cultural components, which cannot be separated, and so it embraces a variety of manifestations that have been recognized in the framework of the UNESCO Convention for the Protection of the World Heritage, Natural and Cultural. Cultural landscapes thus fall into three main categories, namely, landscape designed and created intentionally by man, organically evolved landscape and associative cultural landscape [17].

Landscapes are valued for their unique character and cultural heritage, and for providing feelings of attachment, belonging and inspiration [19]. Therefore, they are part of the cultural heritage and are key components of local, regional and national identities [20]. They are part of people’s collective identity, as recognized by UNESCO [17], and a core element of individual and social well-being, as admitted by the Council of Europe [21]. When the landscape is valued by itself, taking a memorial dimension and founding the identity of a group, this assumes a new assignment, to “express dreams” [22]. The best expression of this landscape category is, in the opinion of Andrade [23], the historic garden.

Some of the most valued elements of worldwide cultural heritage are historic gardens [8,9]. Garden and parkland landscapes constructed for aesthetic reasons, and which are often (but not always) associated with religious or other monumental buildings and ensembles, belong to the category of landscape designed and created intentionally by man [17]. The historic garden is a creation of societies and a reflection of their history and different cultures; it bears witness to times past and the relationship of humans with nature and with the landscape. It is a complex architectural system, whose joint composition of life and the inert makes it a “Living Monument” [5].

The definition of the historic garden was formalized at the first international symposium on the conservation and restoration of gardens of historical interest, which was held in Fontainebleau (1971) on the initiative of ICOMOS and the International Federation of Landscape Architects (IFLA). It was later adopted and institutionalized by the Florence Charter. A historic garden is described as an architectural and horticultural composition, applicable to a small garden or a large park, whether formal or landscape, of interest to the public from a historical or artistic point of view, and thus a monument, a living monument [24]. The term “historic” acquires a certain relativity, because gardens that have been produced in the past, whether recent or not, can be considered historic [25] so that “historic” transcends the value of antiquity [12]. This definition also has huge elasticity, in that it includes several types of gardens (regular or irregular, classic, baroque, romantic or landscape), which, since they represent an original work, are recognized as part of cultural heritage, and have a certain cultural value [25]. A historic garden is not a matter of age, stylistic features or dimensions; it is defined by its character and historical interest, for what it represents in terms of memorial, identity and culture, for the value it adds to the sites and monuments it may be associated with and for what it awakens in the present [12]. It is this wide conceptual dimension of a historic garden that is considered in the course of this work about inventories.

The ways in which cultural landscapes are understood and managed are vital to sustainability [17,26]. In the current context of increasing concerns about sustainability, and the great pressure cultural landscapes are under due to climate, demographic, social and ideological changes [26], it is fitting to recall how historic gardens have been understood, managed and valued, and what role inventories have played in this process.

2.2. Safeguarding and Enhancing Historic Gardens over Time and the Inventory Figure

Until the 1980s, the guidelines in documents such as the Conventions, Recommendations and Resolutions produced and disseminated by UNESCO, ICOMOS and ICOMOS-IFLA, and even the Council of Europe, did not make any specific reference to historic gardens, although some of them could be adapted and applied to this heritage asset. One example is the 1931 Athens Charter, the first instrument for the conservation and preservation of monuments. It considered the need to study and preserve their surroundings, specifically the ornamental vegetation, and where the inventory was already mentioned as the responsibility of each State or of institutions with due power [27]. The Recommendation concerning the Safeguarding of Beauty and Character of Landscapes and Sites, presented by UNESCO in 1962, laid down guidelines for the protection of landscapes and natural sites, rural and urban, whether or not resulting from the “work of man”, which were of aesthetic, and cultural interest or that constituted characteristic natural surroundings [28]. In 1964, the Venice Charter on the conservation and restoration of monuments and sites formally expressed the extension of the concept of monument to other elements such as the landscape and, although there is no concrete reference to historic gardens, there is an appeal to the need to preserve the traditional framework [27].

Although interest in gardens and their protection had arisen at the time of the Universal and International Exhibitions, which occurred before the Second World War [29], it should be noted that it was only in the late 1960s that the specific Section for gardens was set up by the IFLA. The purpose was to discuss an approach for dealing with gardens of historical interest and it set out to identify and catalogue the major historical gardens in various countries around the world, a total of 1550 in all [6,12]. The International Committee of Historic Gardens and Sites was established in the early 1970s at the Fontainebleau meeting, as a subdivision of ICOMOS and IFLA. It was intended to investigate and inventory the gardens of greatest interest, which made the promotion of conservation, restoration and research of historic gardens and cultural landscapes more effective [1]. This meeting also formalized the definition of historic garden and made recommendations for safeguarding gardens.

Still in the 1970s, the Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage held that cultural and natural heritage can be proposed as world heritage, with cultural heritage including places of interest, which includes the works of man, or the combined works of man and nature. The importance of inventories was again mentioned [27]. The Burra Charter, first adopted in this decade, established guidelines for conserving places of cultural significance, defining terminologies and principles of intervention in architectural and landscape heritage [30].

A new attitude developed towards gardens, principally since the 1980s with the drafting of the Florence Charter by ICOMOS-IFLA International Committee for Historic Gardens, as an addendum to the Venice Charter, covering the specific field of safeguarding historic gardens that was missing. This document defined the historic garden, assigned it the status of a monument, a “living monument” perishable over time and with use, and established a set of principles for interventions in the maintenance, conservation, restoration and reconstruction, use and the legal and administrative protection of this heritage. Furthermore, its Article 9 explicitly drew attention to the importance of identifying and creating listings, along with their relationship with effectiveness in the protection and preservation of historic gardens [24]. The production of garden listings, inventories and registers has since thrived, involving central and local authorities and even civil society. Take the case of the United Kingdom, for example, where each country has its own heritage agency to draw up inventories of parks and gardens and, in addition to the National Register, a number of other agencies, authorities and local associations keep registers of historic parks and gardens [31].

Within the broad spectrum of cultural heritage, guidelines continue to emerge in the various documents produced after the Florence Charter that can be adapted to the preservation of historic gardens. Among the most relevant are the Granada Convention for the Protection of the Architectural Heritage of Europe approved by the Council of Europe in 1985, the Washington Charter for the Conservation of Historic Towns and Urban Areas adopted by ICOMOS in 1987, the previous versions of and the current Burra Charter issued by Australia ICOMOS, the Charter of Krakow 2000 about the Principles for Conservation and Restoration of Built Heritage and the European Landscape Convention of the Council of Europe (2000).

Pursuing the goal of knowing and safeguarding this heritage, a European database of gardens has been set up more recently by the European Institute for Gardens and Landscapes (IEJP), which so far includes data from Portugal, France, Belgium and England in a total of about 18,000 historic gardens. Several other inventories from different European countries are currently being compiled to be added to this database [32].

In addition, some initiatives that have been developed to enhance and publicize historic gardens within Europe should be mentioned. Examples include the European Cultural Heritage Information Network (HEREIN), the European Garden Heritage Network, the Network of European Royal Residences and the European Historic Houses Association. It is also important to mention the European Route of Historic Gardens, a Council of the Europe Cultural Route, seen as the best way to recognize its historical, artistic and social value [33].

In the Portuguese context, historic gardens have never been a major concern. Nonetheless, the Law on Portuguese Cultural Heritage includes a specific reference to historic gardens. It recognizes them as a cultural asset and therefore one of the components of the general valuation regime (Article 70º), and an element that enhances the coherence of monuments, ensembles and sites (Article 44º) [34]. Although it provides two levels of heritage registration—classification and inventory—with a view to ensuring their legal protection and valuation and to prevent their disappearance or degradation, it does not define a historic garden or a specific legal regime, which jeopardizes a more effective protection.

2.3. The Cultural Specificity and the Differentiating Nature of the Portuguese Historic Garden

Portuguese gardens are not comparable to those in countries such as England, France or Italy. The ultimate purpose of displaying or being a symbol of ostentation and power is not part of the essence of the Portuguese garden. On the contrary, a garden was built as an extension of the house and therefore to be habitable, as a haven, intimate and quiet, a place of charm and well-being with nooks and crannies, a crypto-magical spot, more to be enjoyed from within it than admired from the outside [8,35].

The Portuguese garden, originating as an orchard garden, has gone through times and trends and over the centuries has found ways to adapt to circumstances and absorb the various influences that came its way. Caldeira Cabral [8] sees a concept of Portuguese garden being created under a series of varied circumstances and a mix of influences that made it different and unique.

Their location between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic, the climate, the socio-political and economic history, organization and social evolution, together with the rugged topography have left Portuguese gardens imbued with a set of characteristic and distinctive features that give them a character and originality that distinguishes them from the large European gardens to which the general public will be accustomed [8,13].

In the opinion of Castel-Branco [13], the variety of flowering trees and shrubs; the deep views and prospects; the different levels that form terrace-gardens; the tiles with various motifs and colors; large water surfaces in the form of pools, lakes, fountains or monumental fountains, often functioning as the polarizing elements of the area, are the key elements of a Portuguese garden. Other important identifiers define the very essence of the Portuguese garden. They include trellises and arbors, flower beds (alegretes), decorative shell-and-pebble masonry (embrechados), benches and other embellishments (natural and artificial), paths and high walls/hedges, which can be found alone or combined, especially in the large quintas de recreio (recreational farms) (a cluster formed by woods, a formal garden next to the house and a vegetable garden/orchard) of the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries [8,13,35,36,37].

The concept of a garden as a closed space and somewhere to be became diluted in Romanticism, with the influence of European aesthetics, and, above all, with the fashion of the eighteenth and nineteenth century English garden park. The Renaissance period also fostered the development of the monumental religious landscape of the north and, in the second half of the eighteenth century, botanical gardens made their appearance. The twentieth century saw the modernist style making its mark on some national parks [8,35].

According to Caldeira Cabral [8], from north to south and including the islands, Portugal has a wide and diverse spectrum of gardens from the most varied periods, and they display characteristic cultural features. The examples, albeit in different states of preservation, range from the Roman peristyles and mediaeval cloisters to twentieth-century public parks, by way of quintas de recreio, convent and monastery landscapes, sanctuaries, botanical gardens, private and public gardens, parks, avenues and squares of historical, cultural and artistic value and interest. The assortment of types of gardens and the mixture of styles characterize the originality of the art of landscaping in Portugal [8,35].

3. Materials and Methods

The concern with historic gardens has for decades been confined mainly to the academic environment and to some personalities, resulting in a set of listings and inventories, rooted in the early twentieth century, mostly limited in terms of coverage of the national territory as a whole (mainland and islands). It was only in the 1980s that this interest was extended to the institutional decision-making bodies, and protocols began to emerge between various institutions for inventorying gardens.

To accomplish the defined objectives, three major steps were taken. First, bibliographic research was carried out on the inventories of Portuguese historic gardens to find out what inventories existed, their authors and where and how the information was available. The next step was to gather all available information on those inventories in their different formats, analogue and digital, which were scattered throughout the various Portuguese libraries and digital platforms. At the same time, a database was organized with the most relevant information for each inventory, that is to say authorship, type and number of inventoried spaces, their location, and the type of information available on each garden. A qualitative analysis was then carried out on the content, and the outcome is summarized in the next section, with the purposes and the methodological process of carrying out each inventory being added whenever the available information allowed.

Table 1 lists the inventories and similar works that constitute the scope of this study. They are presented chronologically along with information on the geographic area covered.

Table 1.

Inventories of (historic) gardens in Portugal.

It should be noted that the bibliography discreetly mentions two other works that were started, one in the 1940s and the other in the 1960s, but which were not completed or published.

4. Results

This research has identified a wide range of inventories, including public and private and in partnership. The main characteristics of the 12 inventories carried out in Portugal and subjected to analysis are summarized in Table 2. It contains their fundamental characteristics and the type of information covered. Differences and achievements of each inventory, as well as the purposes and methodological process involved, are developed in the text.

Table 2.

Summary of inventory information.

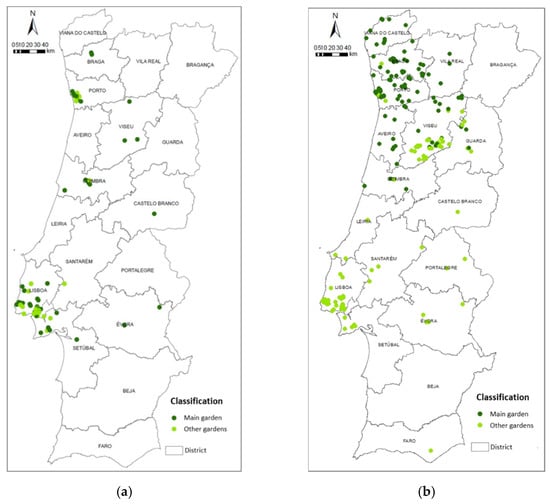

The historian Sousa Viterbo [36,38] produced a first work, A Jardinagem em Portugal (Gardening in Portugal) (1, Table 2), in which he expresses concern about the serious threat that gardens might disappear because they are not studied, registered or protected by specific legislation. The two editions of the work do not have the rigid and systematic character of an inventory; they mainly focus on gardening techniques and the gardeners. However, the author does list a series of remarkable gardens, mostly quintas de recreio, describing about 50 units in some detail, especially at the historical level. He refers to many others, mainly located in the large urban centers of Lisbon, Porto and surrounding areas (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

(a) Sousa Viterbo inventory [36,38]; (b) Ilídio de Araújo [39] inventory. Prepared by the authors.

In the early 1960s, Ilídio de Araújo [39] published A Arte Paisagista e a Arte dos Jardins em Portugal (Landscape Art and the Art of Gardens in Portugal) (2, Table 2). This work was regarded as pioneering in the study of gardens and has served as a reference for subsequent studies until today. However, only a first volume was published, which covered only the north of the country and did not claim to be complete. Based on an extensive collection of relevant literature and visits to the places, the author produced a list of landscape art. In addition to this list, the author adds other gardens, some of which are covered in detail while others are simply mentioned, in total about 200 sites, also showing a larger concentration in the Porto and Lisbon areas (Figure 1b). This inventory confirms the importance and profusion of places of a religious nature in the northern region.

The gardens are described in varying amounts of detail and include information about geographical location, historical and architectural aspects. They are illustrated with photographs and sometimes with the architectural plans, indicating the literature references for each space.

In the 1980s, Aurora Carapinha [37] carried out and presented the Inventário da Arte Paisagista em Portugal (Inventory of Landscape Art in Portugal) (3, Table 2). The purpose of this academic study was to set out what had existed and what still existed, and to characterize and highlight the value of landscape art. Documentary sources were used, with an emphasis on the pre-inventory and the work of Araújo [39], complemented with other guides, artistic inventories, monographic studies and chorographic dictionaries. The types of space inventoried were grouped into ten categories. Of more than 1100 inventoried spaces, almost 50% were quintas de recreio. This inventory contains some information about the ownership (public or private), something that was not provided as explicitly or that did not arise at all in earlier works. For the first time, we are looking at a much larger quantitative dimension than was recorded in studies before, or since.

Along the same lines as the works of Sousa Viterbo [36,38] and Araújo [39], we find Tratado da Grandeza dos Jardins de Portugal (Treaty of Greatness of the Gardens of Portugal) (4, Table 2), by H. Carita and A. H. Cardoso [35]. A work which, although not an inventory in the true sense of the term, references about 150 gardens extensively or merely indicatively, with great emphasis on quintas de recreio, gardens and parks of manor houses and palaces, both existing and disappeared, covering Portuguese landscape art from the Greco-Roman tradition to nineteenth century Romanticism. Historical and architectural aspects and features of the gardens are examined in detail, together with their historical and functional framework, which are profusely illustrated with pictures, drawings and plants. In the early 1990s, Luís Ribeiro [40], in his academic work Quintas do Concelho de Lisboa—Inventário, Caracterização e Salvaguarda (Farms in the Municipality of Lisbon—Inventory, Characterization and Safeguard) (5, Table 2), focused on a specific region, Lisbon, and compiled an inventory of more than 500 farms, resulting in a listing that is also mapped.

The institutional environment has shown a more effective interest in this art since the end of the 1980s. Several protocols were established between state and private institutions and the academic community with a view to promoting actions to restore historic gardens, to set up gardening schools and to inventory the gardens.

In the 1990s, as part of the Architectural Heritage Inventory, a computerized database of Portuguese gardens and historic sites was created by the now defunct General Directorate of Buildings and National Monuments, in collaboration with landscape architects from the University of Évora (6, Table 2). In it, about 300 gardens, convent and monastery landscapes, hunting reserves and parks were registered, described, contextualized historically and given a legal classification and illustrated [15].

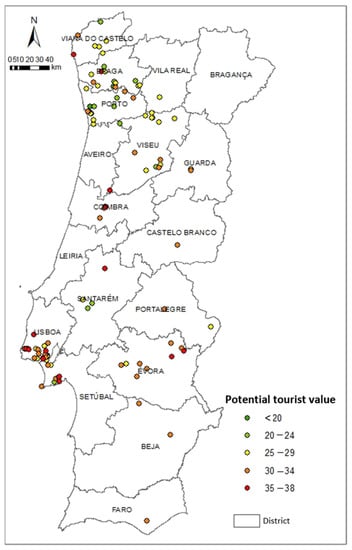

At the end of the 1990s, a team of landscape architects were commissioned by the Institute of Financing and Support to Tourism to carry out a survey of the historical gardens in mainland Portugal, taking into account their tourist potential (7, Table 2). The work was developed in three phases: an initial list was drawn up using previous surveys and other documentary sources; these places were visited to collect information and a photographic record was made; in the third phase, a study was carried out to provide an overview that included the quantification of its potential for tourism. About 120 gardens were identified and each was assigned its own value based on the intrinsic qualities and the items/features of a Portuguese garden (construction time, creator/historical features, landscape features, built elements, vegetation, bibliographic and/or pictorial references and legal classification) and a complementary value, including potentially developing tourism and promoting qualities outside the gardens (location, surroundings, activities carried out, need for restoration and owner inclination) [41]. The potential tourist value, rated between 1 and 40 points, varied between a minimum of 12 and a maximum of 38. The Lisbon and Porto regions account for a large proportion of the gardens with tourist potential (40%), followed by the central region (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Survey of historic gardens for tourism [41]. Prepared by the authors.

In the final work, each garden had an identification sheet and location map, a brief description of the history of the place and its state of conservation and illustrative images. Here, there is already a systematization of the information that is presented in more detail, considering the garden itself from several angles, the surroundings and aspects related to the visit. This work was later revised and updated, resulting in publication of a book.

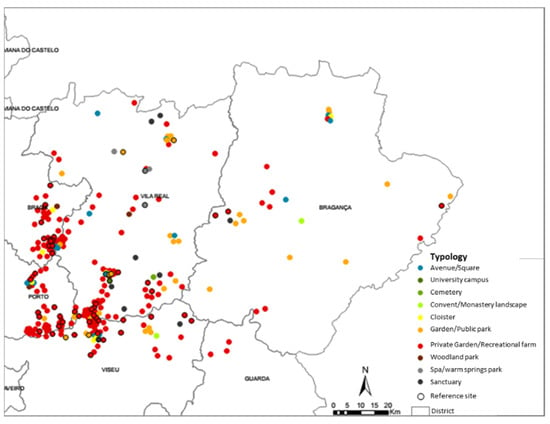

During the course of the new millennium, the inventory Arte Paisagista no Norte de Portugal (Landscape Art in Northern Portugal) was a project carried out by the Department of Landscape Architecture of the University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro (UTAD) (8, Table 2). It covered 36 municipalities in the north-east of Portugal. The methodology adopted included gathering and analyzing several documentary sources of inventory methodologies and gardens, and direct contacts with various public bodies, owners and managers of the places. A list of more than 780 sites of potential landscape interest was produced and this made it possible to start building a digital database and documental archive. The places were visited to collect information and images, resulting in a final selection of 274 sites. The selection criteria were: aesthetic quality; the quality of the construction and decorative elements and the botanical collection; mention of an artistic period or a recognized designer; an association with a historical event or period of special interest; the degree of influence of the site on its cultural and social context; integration and the relationship with the surrounding landscape; and the degree of integrity and conservation status of the site [42]. Private gardens and quintas de recreio (70.1%) were the most prevalent category. About three-quarters of the properties were privately owned and were concentrated in a specific type of area (river valleys) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Landscape Art Inventory in Northern Portugal [42]. Prepared by the authors.

Regarding this inventory, a digital online database was developed, which was accessible to the public through a website (www.artepaisagista.utad.pt/) [42]. The information about typology, flora, and the public edition field inventory should be highlighted on the inventory sheet. The information from this database was transferred to the database of the Inventory of Historic Gardens of Portugal and is included in the European base.

The project LX GARDENS—Gardens and Historic Parks of Lisbon: study and landscape heritage Inventory (LX GARDENS—Jardins e Parques Históricos de Lisboa: estudo e inventário do património paisagístico) was carried out from 2011 to 2014 by the Baeta Neves Centre for Applied Ecology (CEABN) of the Higher Institute of Agronomy of Lisbon in partnership with the University of Algarve (9, Table 2). This was a historical-artistic and botanical study of 60 gardens, farms and historical parks in Lisbon from the eighteenth century until the 1960s. Therefore, one of the project’s goals was “to contribute to the definition of principles and procedures for the identification, grading and protection of gardens based on their historic and artistic value and their presentation as an invaluable part of Lisbon cultural heritage with a strong touristic potential” (p. 413) [43]. The definition of the criteria that should support the classification of the landscape heritage of Lisbon was one of the proposed objectives. With a strong interdisciplinary aspect, this research first involved a literature review of the inventory models used in similar research, both nationally and internationally, and gathering a list of documental, bibliographic and iconographic sources. This was complemented with fieldwork, and photographic and graphic records. An Inventory Model for Landscape Heritage was devised and structured around the themes that included history, history of art, landscape architecture, architecture, urban ecology, botany, tourism and the social sciences, whose information was entered into a relational database—the LX Gardens Database [43], which is not available to the public.

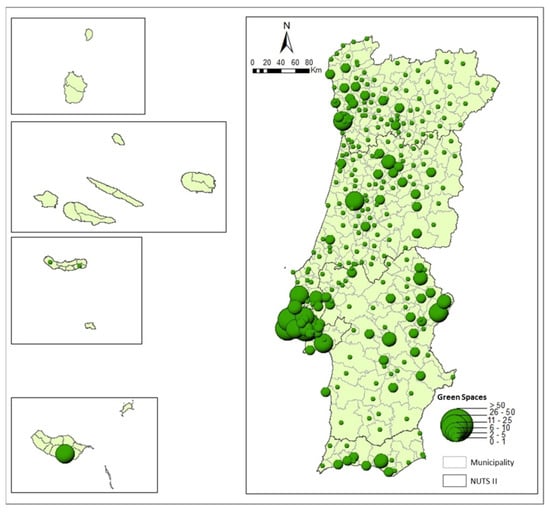

The Architectural Heritage Inventory, already mentioned, was integrated in the Architectural Heritage Information System (SIPA) (10, Table 2). It is ongoing and being updated in terms of the information on the property and at the level of the groups/categories in which the assets are registered, which change over time. The gardens have already appeared in the categories Landscape and, afterwards, Monument, and they are currently entered in the Green Space category. Until mid-2015, this included a range of items (gardens, farms, convent and monastery landscapes, hunting reserves, woods, parks, playing fields, landscaped gardens, cemeteries, and so forth) without a specific category for historic gardens. It contained almost 600 inventoried references spread throughout the country, with a focus on the metropolitan area of Lisbon (Figure 4) [44].

Figure 4.

Architectural Heritage Inventory—Green Space Category [44]. Prepared by the authors.

With the reorganization of the Green Space category, sub-categories were created—a set of green spaces, spaces for walking around, for growing plants, for playing sport, gardens (more than three-quarters of the inventoried spaces) and parks, in which other more specific typologies were defined by type and function. There is no category of historic garden, and the nature of the information, often flawed and with little detail, makes it hard to accurately individualize the historic gardens. Having adopted this new approach, although the asymmetries and main foci of attention have not changed, most of the quintas de recreio, convent and monastery landscapes, manor houses, and so forth, are no longer included and are in the category ‘Architectural Complex’. A significant number of Portuguese historic gardens are thus excluded, up to now [45]. This exclusion may not be definitive, because, as in other cases, the gardens of these groups should have their own specific entry and be included in the Green Space category.

The Architectural Heritage Inventory Standard—Green Space defines indications and rules that guide the inventory of the heritage related to Landscape Architecture in the context of SIPA [46]. The fields that constitute the database are grouped into six categories: identification; description; historical, artistic and typological analysis; technical data and state of conservation (not available); bibliography and specific documentation; identification of the author and data related to the management of the record. The inventory record consists of 48 information fields, of which only 28 are publicly available via the online platform (www.monumentos.gov.pt/) [47], and listed in Table 2.

Early in the second decade of the twenty-first century, CEABN, instigated by DGPC and the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, in cooperation with IEJP, created the Inventory of Gardens and Landscapes in Portugal (11, Table 2), which contains more than 700 Portuguese historic gardens. It is a platform for professionals, researchers, students, tourists and the general public, and at the same time it provides Portuguese data for the European inventory, which can be viewed at http://europeangardens.eu/inventories/pt/ [48]. Where the records are complete, the basic information is similar to that found in the survey of gardens for tourism (7), or in SIPA (10). However, in relation to other inventories, there is (more) information on botany, physiography, and topography, pedology, climate and the activities and events that the gardens can host, as well as information on various scenic intrusions in the surrounding area. Most of the records are incomplete; some just have the information that identifies and locates the gardens, some others also add information about the contacts, the time of creation and the ownership.

This inventory in many ways represents an innovation compared to previous work. First of all, because it focuses on the category of historical gardens, given the extent of the identified assets, which cover the entire national territory (mainland and islands); it has gathered much of the information that was patchy in other inventories, and it is linked to other Portuguese databases such as SIPA (10) and the DGPC inventory of heritage already classified or in process of being classified. Moreover, it is accessible digitally to a wider audience and has an international range by virtue of the nature of the medium in which it is provided, and because it forms part of a European database.

Meanwhile, the Portuguese Association of Historic Gardens (AJH) has carried out the Historic Gardens Inventory (12, Table 2), under the VALORIZAR Program instigated by Turismo de Portugal and under the Lisbon European Green Capital 2020 Project, aiming to create a set of tourist routes of historical gardens. The survey of historic gardens for tourism (7) as well as the Inventory of Gardens and Landscapes in Portugal (11) were taken into account in addition to fieldwork [49]. More than 800 gardens covering the entire national territory have already been inventoried and are available online, with more restricted information fields focused on useful information for the visit and a description of the places. The northern region has the highest number of inventoried gardens, about 50% [50], exactly the same as the previous inventory.

In addition to these larger works, there are other, less well-known, academic and institutional inventory studies that are focused on specific areas, which are scattered around the country’s libraries and institutions [51].

5. Discussion

Each of the inventories presented is important as a documental source that contributes to counter the lack of knowledge about this type of heritage, especially in a more particular professional environment related to this art and at an institutional level. Except for Ribeiro’s inventory [40], which focused only on quintas de recreio, almost all studies identify a wide spectrum of garden types, confirming the diversity of landscape art in Portugal, reported by Cabral [8], that quintas de recreio are the most typical kind of garden, as Carapinha [37] already concluded, and that these are mostly private property. In addition, the geographical distribution highlights the areas where greater numbers of gardens are located, such as the northern region, especially around Porto, and the Lisbon region.

The methodologies have also evolved gradually to the state of complexity of the listing and inventory process and of the information gathered from the work carried out. Instead of extensive descriptions, essentially focused on historical and formal aspects in an amalgamation of poorly organized and systematized information, as can be found essentially in the oldest documents, inventories were emerging that used specific methodologies, including a wider range of better organized information that allows a more complete and detailed identification and characterization of spaces. This is especially true in the CEABN (7), UTAD (8), DGPC/SIPA (10), CEABN & IEJP (11) and AJH (12) inventories, as can be seen in Table 2. The records include several kinds of information about gardens (i.e., history, architecture, botany, typology, functionality and legal classification), and about their location and surroundings.

Consistent data standards are considered by Meyers [10] to be one of the key elements for the effectiveness of inventories. The DGPC/SIPA follows specially developed data standards for the category Green Space, and the above inventories also follow an organizational structure. However, although the general information is similar, there is a lack of uniformity between them (information fields and content). Furthermore, it turns out that the architectural and archaeological heritage as well as the historical context are described, extensively sometimes, while the landscape heritage is disregarded. In the CEABN & IEJP inventory, the information is given in a better organized, more complete, disaggregated form, with some items being specified. However, not all records in the ongoing inventories have all the fields fully filled out with up-to-date information. For instance, in SIPA only about 5% of the records are complete (level 1), and in the Inventory of Gardens and Landscapes in Portugal only 23% of the records have been fully, or almost fully, filled out (2022 data), mainly for the well-known gardens, and the gardens that appear in previous works. In addition, the information is not yet available in other languages as it is supposed to be, just a small abstract in English. These inventories are permanent and still running, and so have time and space to improve, unlike the others, which are closed documents.

There was also a development in the final product that had implications for the accessibility to information. The transfer of published and unpublished works to digital platforms allows not only the continuous input of information but also access to a larger audience, a fact that helps to propagate and promote heritage and foster public engagement with such places and their preservation. SIPA allows new inventory records to be input by users registered on the platform.

Common to all works is a clear concern to learn about and document this fragile heritage with a view to preserving it. The theoretical framework sees landscape inventories as important working tools able to contribute to deciding on priority actions for the recovery, conservation and protection of these spaces [5,9,10]. The analyzed inventories are, above all, an information repository for which it is difficult to establish a concrete direct relationship with effective actions to protect, preserve and enhance the Portuguese landscape heritage. This is because of a set of limitations and constraints which could compromise the real effectiveness of inventories in the management and protection of this heritage. These constraints are related to:

- Portuguese legislation, which sees the inventory as one of the instruments for the protection of cultural heritage but does not set out the inventory procedure or the content that must be included. Data standards for landscape heritage were developed based on the needs and ambitions of each inventory and the result is a lack of uniformity and different levels of information;

- The available information in the ongoing inventories is neither systematic nor up to date, let alone exhaustive, as required by Article 6 of Law no. 107/2001. At SIPA, the information about the protection status is updated but other priorities and the lack of financial investment and personnel to continue this work are among the reasons given for this situation;

- The results of some projects have been confined to their own management structure. This is despite their dissemination at meetings or conferences, which are mainly aimed at a specific audience. Thus, some databases have never been available online until today, others are no longer available but can be consulted in reference libraries, academic libraries or other records offices, along with the oldest studies;

- The multiplication of online platforms with inventories means an unnecessary replication and dispersion of similar information, teams, efforts and expenses;

- The lack of interplay between the legal instruments of protection considered in the legislation—inventory and classification. This means that the classification does not follow the inventory, which has been carried out more or less systematically. In fact, a relatively small percentage of gardens have been classified compared to the number of gardens inventoried. One cause of this is the succession and uncoordinated coexistence of institutions responsible for cultural heritage that led to the duplication of competences and wastage of resources.

It should be noted that some of these issues are not exclusive to Portugal. In the European context it is common not to have a specific central authority or specific legislation focusing on gardens; therefore, their protection tends to be integrated in Institutions and in the legal regulations defined for heritage in general. Serbia is one example where parks and gardens are included in national legislation [52]. For example, the spread of information across various documentary sources and the multiplication of state and non-state digital platforms also happens in United Kingdom, France [31] and even Australia [53]. These have inventories at different territorial scales, which is not the case in Portugal. However, in the case of Australia, there is some agreement between databases and there has been an effort to centralize information [53]. In England, the Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest, a statutory document, imposes high selection criteria for a garden to be included in the Register, focusing on age, rarity, completeness of condition and examples of the work of known national and local designers. In addition, sites less than 30 years old are normally registered only if they are of outstanding quality and under threat [31], something that does not happen in the ongoing inventories in Portugal.

6. Conclusions

This paper has focused on the analysis of a set of inventories of historical gardens carried out over the years in the academic world and also on the initiative of the institutional environment. The content analysis allows to recognize that each study, listing and inventory carried out at different times by different figures, groups and entities with different methodologies and purposes has helped to enrich knowledge of the Portuguese landscape heritage. This reflects the growing interest in its protection and preservation, which, on some occasions, resulted in protocols between institutions for the recovery of gardens being fulfilled. It also leads to the conclusion that this is not an easy heritage to inventory, and it is only possible to protect what is properly known.

Some weaknesses were identified that can be reduced to two major dimensions: information and its organization, systematization, standardization, updating, completeness and availability; and legislation and its clarification, specification, integration and cooperation.

It thus seems clear that in the case of Portugal, for inventories to fulfill their core objective and be effective, it is particularly necessary that heritage and garden heritage professionals, together with the relevant entities, cooperate, discuss and understand the possibility and the advantages of centralizing information about historic gardens in a single list. For this to happen, it is crucial to analyze the existing inventories, to discover more details about the strengths and weaknesses in terms of information, which will allow a sounder understanding of what further work needs to be completed. Solid data standards should be defined consistently and validly over time, with a specific legal framework that establishes a typology of spaces and specifies what information should be added, while ensuring there is a balance, such that the inventory can be compiled in accordance with Article 6 of Law no. 107/2001. Information must be the target of a permanent and systematic investment, both financial and in human resources, which can be achieved by creating and maintaining a team of dedicated professionals to carry out this task on a permanent basis. The effectiveness of the inventory also requires establishing a broad compromise between the heritage legal framework, the entities and the inventory process, so that the information produced leads to classification and also to the creation of specific legislation for historic gardens.

If this is not taken into account soon, not only will sustainable heritage management be compromised, but eventually the preservation and safeguarding of these heritage assets will be jeopardized, too, together with their access, new uses and interpretations by society. In this regard, tourism has been seen as a strategic vehicle to safeguard, value and ensure their cultural and economic sustainability. Inventories and the information they contain are crucial not only to support the implementation and development of tourism strategies based on innovative and effective interpretation techniques, but to prevent any damage that might arise from tourist use.

The lack of access to information in some databases and the slowness of the entities in providing data or clarification on them did not permit a deeper analysis of certain inventories. Despite such limitations, this paper enriches our understanding about the historic gardens’ inventory process by gathering information, and through the evolutionary and comparative analysis carried out. It also provides some insights for a future endeavor with regard to the inventory of historic gardens.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, visualization, supervision, S.S.; writing—review and editing, visualization, supervision, P.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by FCT—Foundation for Science and Technology, grant number FCT_SFRH/BD/85081/2012 and also received support from the Centre of Studies in Geography and Spatial Planning (CEGOT), funded by national funds through the FCT under reference UIDB/04084/2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere thanks to FCT and CEGOT for supporting this research and to Jean Ann Burrows, a native English speaker, for her valuable contribution in translating this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Añón, C.F. Introduction. In Jardins et Sites Historiques; ICOMOS, Ed.; Fundación Cultural Banesto: Madrid, Spain, 1993; pp. 25–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kimber, C.T. Gardens and Dwelling: People in Vernacular Gardens. Geogr. Rev. 2004, 94, 263–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, M.; Church, A.; Claremont, A.; Stenner, P. ‘I love being in the garden’: Enchanting encounters in everyday life. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2009, 10, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berjman, S. El Paisaje y el Património. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/publications/jardines_historicos_buenos_aires_2001/conferencia1.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2016).

- Estadão, L. Salvaguarda dos Jardins Históricos Através do Inventário. Caracterização Topológica e Tipológica dos Jardins do Alentejo; Graduation Report; Universidade Técnica de Lisboa: Lisbon, Portugal, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gollwitzer, G. L’Inventaire des Jardins Historiques. In Jardins et Sites Historiques; ICOMOS, Ed.; Fundación Cultural Banesto: Madrid, Spain, 1993; pp. 31–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sales, J. The Conservation of English Landscape Gardens of the National Trust. In Historic Gardens and Sites; ICOMOS, Ed.; Sri Lanka National Committee of ICOMOS: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 1993; pp. 145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira Cabral, F. Fundamentos da Arquitectura Paisagista; Instituto da Conservação da Natureza: Lisboa, Portugal, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Estadão, L. Políticas de Inventário de Jardins Históricos em Portugal. In Proceedings of the Congresso 30 Anos APAP a Paisagem da Democracia, Porto, Portugal, 12–14 October 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, D. Heritage inventories: Promoting effectiveness as a vital tool for sustainable heritage management. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 6, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. Principles for the Recording of Monuments, Groups of Buildings and Sites. 1996. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/charters/archives-e.pdf (accessed on 29 July 2020).

- Andrade, I.E.-J. Construção e desconstrução do conceito de jardim histórico. Risco 2008, 8, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Castel-Branco, C. (Ed.) O jardim português e a história da água nos jardins. In A água nos Jardins Portugueses; Scribe: Lisboa, Portugal, 2010; pp. 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, C.M. Jardins Históricos Portugueses: Conceção e enquadramento jurídico para a sua gestão e valorização. In Genius Loci: Lugares e Significados | Places and Meanings; Rosas, L., Sousa, A.C., Barreira, H., Eds.; CITCEM: Porto, Portugal, 2018; Volume 3, pp. 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Castel-Branco, C. Jardins Históricos. Poesia Atrás dos Muros; Inapa: Lisboa, Portugal, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Carapinha, A. Uma breve perspectiva histórica. In Guia dos Parques, Jardins e Geomonumentos de Lisboa; Travassos, D., Ed.; Câmara Municipal de Lisboa: Lisboa, Portugal, 2009; pp. 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. The Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/?msclkid=b88f3457c23511ec926b2c6b9d0c607a (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Gonçalves, R.M.T. A Protecção do Património Paisagista—1.ª parte. Rev. Patrim. Estud. 2001, 1, 108–115. [Google Scholar]

- Schulp, C.; Levers, C.; Kuemmerle, T.; Tieskens, K.; Verburg, P. Mapping and modelling past and future land use change in Europe´s cultural landscapes. Land Use Policy 2019, 80, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.; Lennon, J. (Eds.) Managing Cultural Landscapes; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. The European Landscape Convention. Florence. 2000. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/landscape/text-of-the-european-landscape-convention (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Claval, P. Géographie Culturell; Armand Colin: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, I.E.-J. Dimensão Ambiental do Patrimônio Verde Público Urbano: O Impacto do Entorno Urbano nos Jardins de Interesse Histórico. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Historic Gardens—The Florence Charter. 1981. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/charters/gardens_e.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2011).

- Pechère, R. La restauration des jardins historiques et la philosophie du coloque. In Historic Gardens and Sites; ICOMOS, Ed.; Fundación Cultural Banesto: Madrid, Spain, 1993; pp. 29–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tully, G.; Piai, C.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J.; Delhommeau, E. Understanding Perceptions of Cultural Landscapes in Europe: A Comparative Analysis Using ‘Oppida’ Landscapes. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2019, 10, 198–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, F.; Correia, M.B. Património Arquitectónico e Arqueológico; Cartas, Recomendações e Convenções Internacionais; Livros Horizonte: Lisboa, Portugal, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Recommendation Concerning the Safeguarding of the Beauty and Character of Landscapes and Sites. Available online: http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=13067&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html (accessed on 29 July 2020).

- Lummen, A.M. La Memoria de la História. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/publications/jardines_historicos_buenos_aires_2001/conferencia2.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2016).

- Australia ICOMOS. The Australia ICOMOS Charter for the Conservation of Places of Cultural Significance—(The Burra Charter). Available online: https://australia.icomos.org/publications/charters/ (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- Silva, S. Lazer e Turismo nos Jardins Históricos Portugueses. Uma Abordagem Geográfica; Fundação Eng.º António de Almeida: Porto, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- IEJP. European Inventories. Available online: http://europeangardens.eu/en/european-inventories-2/european-inventories/ (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- ERHG. The European Cultural Route Project. Available online: http://europeanhistoricgardens.eu/en/ (accessed on 3 December 2020).

- Assembleia da República Portuguesa. Lei nº 107/2001 de 8 de Setembro de 2001. Available online: https://dre.pt/dre/detalhe/lei/107-2001-629790 (accessed on 6 March 2012).

- Carita, H.; Cardoso, A.H. Tratado da Grandeza dos Jardins em Portugal ou da Originalidade e Desaires Desta Arte; Edição dos Autores: Lisboa, Portugal, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa Viterbo, F. A Jardinagem em Portugal: Apontamentos Para a Sua História; Imprensa da Universidade: Coimbra, Portugal, 1906. [Google Scholar]

- Carapinha, A. Da Essência do Jardim Português. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de Évora, Évora, Portugal, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa Viterbo, F. A Jardinagem em Portugal, 2nd ed.; Imprensa da Universidade: Coimbra, Portugal, 1909. [Google Scholar]

- Araújo, I. A Arte Paisagista e a Arte dos Jardins em Portugal; Ministério das Obras Públicas, Direção Geral dos Serviços de Urbanização: Lisboa, Portugal, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, L. Quintas do Concelho de Lisboa—Inventário, Caracterização e Salvaguarda; Pedagogical Aptitude Report; Universidade Técnica de Lisboa: Lisboa, Portugal, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Castel-Branco, C. Levantamento e Avaliação de Jardins Históricos Para Turismo; Centro de Ecologia Aplicada Baeta Neves do Instituo Superior de Agronomia: Lisboa, Portugal, 1998; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro. Arte Paisagista no Norte de Portugal—Inventário de Sítios de Interesse. Available online: http://www.artepaisagista.utad.pt/area_est.html (accessed on 2 June 2012).

- Soares, A.L.; Talhé Azambuja, S.; Marques, T.; Silva, A.I.; Azambuja, J.; Arsénio, P. Historic Gardens of Lisbon—A Landscape Heritage Inventory Model. In Proceedings of the European Council of Landscape Architecture Schools (ECLAS) 2014 Conference Landscape: A Place of Cultivation, Porto, Portugal, 21–23 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- IHRU. Pesquisar o Inventário do Património Arquitetónico. 2014. Available online: http://www.monumentos.gov.pt/Site/APP_PagesUser/Default.aspx (accessed on 30 March 2014).

- DGPC. Pesquisar o Inventário do Património Arquitetónico. 2022. Available online: http://www.monumentos.gov.pt/Site/APP_PagesUser/Default.aspx (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- IHRU. Normas de Inventário do Património Arquitetónico—Espaço Verde (NIPA-E.V.), version 4.0, no. 8; Instituto da Habitação e Reabilitação Urbana: Lisboa, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- DGPC. Inventário do Património Arquitetónico—Estrutura de Dados. Available online: http://www.monumentos.gov.pt/site/app_pagesuser/SitePageContents (accessed on 28 June 2018).

- IEJP. Inventário de Jardins e Paisagens em Portugal. Available online: http://europeangardens.eu/inventories/pt/ (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Andresen, T. Inventário dos Jardins Históricos de Portugal. Objetivos, Metodologia, Critérios. Available online: https://www.jardinshistoricos.pt/fileman/Uploads/Documents/AJH_Inventario.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- AJH. Inventário dos Jardins Históricos de Portugal. Available online: https://www.jardinshistoricos.pt/home/search (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Amaral, F.; Castel-Branco, C. Inventory of historic landscapes and gardens in Portugal. In Proceedings of the 2013 Esri International User Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 8–12 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- AISBL HEREIN The Europe of Gardens. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/hors-serie-herein-1-l-europe-des-jardins-the-europe-of-gardens/16809a41d3 (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Australian Garden History Society. A National Review of Inventories of Historic Gardens, Trees & Landscapes. Available online: https://www.gardenhistorysociety.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Inventories_of_historic_gardens_final_6-7-2012had9.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2018).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).