Abstract

The aim of the article is to identify a degree of inclusive growth and to examine the influence of determinants of inclusive growth in the European Union (EU-27) countries, with particular emphasis on factors related to the influence of governments and central banks. The study took advantage of the weight correlation method, which was used to build an inclusive growth measure for the EU-27 for the years 2000, 2008, and 2020. For the construction of the inclusive growth rate, 42 factors were selected that affect inclusive growth in the economic, financial, and non-wage area. These determinants are found in the area of the influence of economic authorities, and mainly in the area of authorities responsible for conducting monetary and fiscal policy and general governance. On the basis of the built-up indicator of inclusive growth, it was noticed that among the 27 EU countries in the studied three years, only four countries distinguished themselves with the highest inclusive growth over the last 21 years, these are: Denmark, Luxembourg, Sweden, and Finland. On the other hand, invariably, three countries recorded the lowest inclusive growth, i.e., Bulgaria, Croatia, and Romania. The added value of the structure of the inclusive growth indicator was a possibility to observe which of the three areas: economic, financial, or non-wage, had a significant impact on the position of a given country in the compiled inclusive growth ranking.

1. Introduction

The need to use a growing economic potential to meet aspirations and expectations of a whole society is gradually becoming an increasingly discussed problem. This topic is seen as a problem due to the process of increasing socioeconomic inequalities. Some economists, such as T. Piketty [1] emphasize that these socioeconomic inequalities result from the lack or imperfection of state intervention in the market mechanism. Eliminating these inequalities requires abandoning the so-called market fundamentals and allowing public authorities to intervene more in the economy. It is worth emphasizing that growing property and income inequalities are associated with social exclusion. Hence, at the end of the last century, the concept of inclusive development appeared in social thought. In line with the definition of the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), inclusive development is defined as a type of economic development that integrates society by observing the standards and principles of human rights, ensuring that everyone has an opportunity to participate in socioeconomic life. Moreover, it enables the use of the effects of economic growth and ensures nondiscrimination and responsibility for decisions taken and implemented [2]. According to the World Bank, an inclusive type of economic development leads to the reduction of poverty and enables socially excluded people to participate in the benefits of economic growth [3,4]. In turn, inclusive growth implies that GDP growth is not an end in itself. In this theory, it is more important to distribute the benefits that countries obtain from this growth and to compensate for income and property inequalities [5]. Hence, the following factors were the authors’ motivation to conduct the study presented in this paper:

- (1)

- Economic growth, globally and per capita, is no longer used as a basic measure of the wealth of states and nations;

- (2)

- Economic growth is no longer able to stop the stratification of the population in terms of wealth, nor does it guarantee universal access to economic benefits, reduction of the poverty sphere, or a noticeable improvement in the standard of living of the whole society;

- (3)

- There is still an insufficient number of publications on inclusive growth research;

- (4)

- The need to pay attention in research and literature to the modification of the currently implemented model of economic development, and inclusion in the research of measures of exclusion as more and more people take advantage of the benefits of economic growth;

- (5)

- The need to pay attention to the necessity of engaging economic policy decision makers in shaping inclusive growth in a given country. It is the decisions of economic authorities that have a direct impact on improving the quality of life of societies, improving employment opportunities for citizens, managing free time, ensuring proper social and environmental security, health protection, development of the human spiritual sphere, and meeting a number of other conditions for social inclusion of citizens;

- (6)

- Emphasizing the importance of sustainable finances or governance in the process of studying inclusive growth.

The aim of the article is to identify a degree of inclusive growth and to examine the influence of determinants of inclusive growth in the European Union (EU-27) countries, with particular emphasis on factors related to the influence of governments and central banks.

The structure of the article is as follows. The first part focuses on the introduction to the research along with presentation of the research motivations. The second part presents the results of a review of research on the theoretical foundations of inclusive growth and variables influencing measures of economic and social growth, taking into account the importance of decisions made by economic authorities in selected countries. In the third part, the variables used in the study were presented, and on their basis the measure of inclusive growth in the European Union countries was constructed with the use of a pseudo-single-feature indicator calculated by the weight correlation method. The fourth part contains a discussion on the obtained research results, consolidating them in the economic and research reality. The last section presents conclusions.

2. Literature Review

When discussing inclusive development, attention should be paid to social interest and long-term perspectives [6]. Sustainable development concerns the compliance of growth with the environment and resources, and increasingly often in the context of sustainable development, the question arises whether all groups in society can sufficiently benefit from economic growth [7] (i.e., the concept of inclusive development appears). It is worth mentioning the Europe 2020 Strategy here. This strategy emphasizes the need for joint action of the European Union countries to overcome the crisis, introduce reforms related to the globalization process, aging of societies, and the growing need for rational use of resources. The priorities of the Europe 2020 Strategy include: smart growth, i.e., development based on knowledge and innovation; then sustainable growth, i.e., changes towards a competitive, low-carbon and resource-efficient economy; and inclusive growth, i.e., based on supporting the economy with a high level of employment and ensuring economic, social, and territorial coherence. The first target of the Europe 2020 strategy—employment—concerns employment at the level of 75% among people aged 20–64. In the area of research and development, the goal of the Strategy is 3% of EU GDP allocated to R&D investments. Another target covers the area of energy and climate and concerns a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 20% compared with 1990 levels; increasing energy efficiency by 20% and striving for 20% of energy to come from renewable energies. The fourth goal of the Europe 2020 Strategy—education—concerns the assumption that less than 10% of students leave education prematurely and at least 40% of people aged 30–34 receive higher education. The fifth goal of the Strategy—fight against poverty and social exclusion—assumes a decrease in the number of people at risk of poverty and social exclusion by at least 20 million. In order to effectively implement the goals and assumptions of the Europe 2020 Strategy, the system of macroeconomic policy coordination and management of implementing structural reforms in the EU was strengthened; the so-called The Integrated Guidelines for Growth and Jobs and the European Semester, the cycle of economic policy coordination was established [8].

Sustainable economic development is closely related to the sustainable development of public finances and the issue of the stability of public finances. Fiscal rules, sound public finances, and public debt are important topics for most governments. The implementation of a sound fiscal policy and the improvement of fiscal discipline through fiscal rules are limitations that affect the decisions of decision makers, and thus the economies of these countries. Due to the financial crisis of 2008–2009, the issue of the stability of public finances has become widely discussed. Much attention was paid to fiscal rules, sound public finances, and public debt, and the EU fiscal governance framework aimed to improve the quality of public finances and to control activity at economic and political levels [9]. The European Union is associated with ideas of ensuring fiscal stability in European countries, starting with the Maastricht Treaty of 1992, which specified the requirements of keeping the public deficit at a low level and ensuring budget discipline. Another document, created to strengthen fiscal discipline in the euro area and to strengthen the Maastricht Treaty, is the Stability and Growth Pact of 1997. This was followed by: Revision of the Stability and Growth Pact of 2005 and Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union—Fiscal Compact (2012) [10]. The Sustainable Finance Action Plan, introduced in 2018, contributed to the development of the EU taxonomy of sustainable activities. Subsequently, the Council and the European Parliament adopted the taxonomy regulation in June 2020, which allowed for the identification of activities that are classified as sustainable in terms of climate change and environmental and social impacts. It is worth emphasizing that Europe’s economic transformation will require large pools of public and private capital to carry out many investments. Likewise, European banks such as the European Investment Bank and other national and regional public banks have a key role to play in sustainable development by providing counter-cyclical investments. It is public authorities and European financial institutions that have access to a wide range of economic tools to transition to a sustainable economy. In order to conduct sustainable finances, the following should be properly designed: EU and national budgets, public aid, fiscal planning, public investments and macroeconomic policy, i.e., the policy of central banks and macroprudential policy [11].

The literature emphasizes that in order for growth to be sustainable and to reduce poverty effectively, it must be inclusive [12,13]. Inclusive growth is often described as increasing the rate of growth and increasing the size of the economy by providing level conditions for investment and increasing the opportunities for productive employment [14]. Inclusive growth, according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), means economic development that creates opportunities for all socioeconomic groups of the population and is able to distribute monetary and non-monetary growth in society in an equitable manner [15]. Achieving inclusive growth is difficult due to growing inequalities around the world, which is often associated with technological changes, deepening finances, and the phenomenon of globalization [16,17]. Some authors emphasize that the inequality may be deepened by foreign trade, which means that industries and companies that are able to compete on the global market are far ahead of companies that do not have such opportunities. Inequalities also exacerbate the wage gap between unskilled and skilled workers who can make better use of new and improved technology [18]. Certainly, rapid economic growth is important to reduce poverty but, in order to support sustainable and inclusive growth in the long term, it should be broadly embedded in all sectors [12,13].

The determinants that contributed to the so-called emerging markets to achieve inclusive growth include: lower initial income, which is associated with conditional convergence, then trade openness, permanent investment, moderate inflation, production volatility, and a better educated workforce [19,20]. In emerging countries, important factors for inclusive growth are undoubtedly macroeconomic stability, human capital, foreign investments, structural changes, business creation, job growth, and financial openness [18]. Based on a panel analysis of the impact of macrostructural factors on inclusive growth in ASEAN countries, it was noted that fiscal redistribution, female labor force participation, productivity growth, FDI inflow, digitization, and savings stimulate inclusive growth. The authors of this study estimated the growth factors conducive to inclusive growth, selecting not only monetary and fiscal factors for the model, but also structural policy factors, such as the labor market, efficiency, digitization, or FDI. Moreover, they used the inclusive growth measure based on the combination of growth of income per capita and income distribution changes into a unified inclusive growth index [21]. Inclusive growth ratio, broken down into an increase in the equity ratio and an increase in GDP per capita, shows whether inclusive growth is stimulated by income or factors measuring equality in society [21,22,23,24]. Inclusive growth factors in the field of fiscal policy based on the tool of equalizing income through taxes and transfers turned out to be important in the light of many studies. A properly designed fiscal redistribution policy can contribute to the improvement of human capital, health, infrastructure, and education, which, as a result, should benefit the poorer part of society and stimulate inclusive growth [25,26]. The central bank and its monetary policy [27] also have an impact on inclusive growth, which is reflected in inflation. High inflation deepens the inequalities between the richer and poorer sections of society. In times of high inflation, the poorer have to give up some consumption. Hence, a monetary policy focused on macro stability may contribute to lowering inflation and minimizing production volatility, which in turn should reduce income inequalities and contribute to improving conditions for the poorer [28,29].

3. Background Section

Ranieri and Almeida Ramos [6], who analyzed several studies on inclusive growth, indicate 15 elements that individual authors treat as key in defining this notion. In their studies, they also emphasized the significance and importance of the factor describing the so-called good governance. Inclusive growth indicators that they identified include: poverty, inequality, growth, employment productivity, entitlements/rights, gender inequality, access to infrastructure, social security, participation, targeted policies, basic social services, good governance, opportunities, barriers for investment, and benefits from growth.

In line with the OECD concept of inclusive growth measures, the literature divides these factors into four main groups, i.e.,: (1) Growth and ensuring equitable sharing of benefits from growth; (2) Inclusive and well-functioning markets; (3) Equal opportunities and foundations of future prosperity; and (4) Governance. In each of these four groups, several most representative indicators were distinguished. In the first group—Growth and ensuring equitable sharing of benefits from growth—the following variables are listed [7,15]:

- GDP per capita growth (%);

- Median income growth and level (%; USD PPP);

- S80/20 share of income as a ratio;

- Bottom 40% wealth share and top 10% wealth share (% of household net wealth);

- Life expectancy (number of years);

- Mortality from outdoor air pollution (deaths per million inhabitants); and

- Relative poverty rate (%).

In the second group—Inclusive and well-functioning markets—OECD included the following factors [7,15]:

- Annual labor productivity growth and level (%, USD PPP);

- Employment-to-population ratio (%);

- Earnings dispersion (inter-decile ratio);

- Female wage gap (%);

- Involuntary part-time employment (%);

- Digital access (businesses using cloud computing services as %); and

- Share of SME loans in total business loans (%).

The OECD in group three—Equal opportunities and foundations of future prosperity—proposed such variables as [7,15]:

- Variation in science performance explained by students’ socioeconomic status (%);

- Correlation of earnings outcomes across generations (coefficient);

- Childcare enrolment rate (children aged 0–2) as %;

- Young people neither employed nor in education and training (18–24)%;

- Share of adults who score below Level 1 in both literacy and numeracy (%);

- Regional life expectancy gap (% difference);

- Resilient students (%).

Finally, in group four—Governance—three variables were distinguished [7,15]:

- Confidence in government (%);

- Voter turnout (%);

- Female political participation (%).

The breakdown of 24 variables selected for the description of inclusive growth proposed by the OECD was based on a report by Stiglitz, Sen, and Fitoussi, which focused largely on measuring welfare in the economy. The concept of welfare was extended beyond the commonly used income per capita [30]. The OECD approach to inclusive growth emphasizes the contribution of the population—especially its part that is less involved in the growth process. Inclusive growth, according to OECD, is based on creating opportunities and accessing wider participation in economic life, depending on political freedoms and social opportunities such as education and health [7]. Some researchers have even developed a social opportunity function with respect to inclusive growth to study the distribution of opportunities in society. Moreover, they emphasized the concept of institutional and economic development related to the availability of economic institutions in the context of equal opportunities for every member of society [31,32]. It is worth mentioning here that the HDI index—that is, Human Development Index—is a sum measure of average achievements in key dimensions of human development, i.e., long and healthy life, knowledge, and a decent standard of living. The HDI is the geometric mean of the normalized indices for each of the three examined dimensions. The purpose of calculating the HDI is to assess the development of a country where the criterion for assessing this development is not only economic growth, but also people and their possibilities. This indicator allows you to compare how countries with the same GNI (Gross National Income) per capita level can achieve different results in terms of social development. The measure of the health area is life expectancy at birth. The measure of the educational area is the learning years of adults aged 25 and over, and the anticipated years of learning for children starting education. On the other hand, the measure of the standard of living is gross national income per capita. However, it should be emphasized that HDI does not take into account inequality, poverty, human safety, empowerment, and other factors [33].

Analyzing the sample of 112 countries in the years between 1975–2012, it was observed that only the efficiency of the government and the law are conducive to inclusive growth. Other factors were also education, improvement of infrastructure, and financial development. It was noticed that the impact of growth on the income of the poorest is nonlinear and decreases with the level of corruption [34]. The most common variables explaining inclusive growth in the studies include:

- Income per capita (measured by GDP per capita logarithm and the squared term to capture a potential Kuznets curve hypothesis stating that inequalities will grow along with the income in the initial stage of development, and will decrease at higher levels of development [35]);

- Human capital (as an indicator of gross enrollment rate in secondary schools—based on the research that indicates that improved level of education is significantly related to the re-education of the poor and economic growth [36];

- Trade openness (openness of trade measured by the sum of exports and imports in % of GDP; theoretical relationship between the openness of trade and poverty is not unambiguous [37], similarly, the literature is not unambiguous in relations between commercial openness and inequality [38,39]);

- Public spending (as public spending on education and healthcare in % of GDP; its increase should help to reduce income inequalities and poverty);

- Basic needs (as a percentage of population with access to better sanitary conditions, which means that better access to sanitary conditions affects the reduction of poverty);

- Inflation (as a change in consumer price index understood as a factor deepening poverty [40]);

- Financial development and openness (measured by a M2 cash aggregate and Chinn–Ito index that is an indicator of openness to the flows in capital markets [41]; choosing this measure—financial development and openness—was an attempt to examine the relationship between development of financial sector and economic growth, which was described in the economic literature [42,43,44,45,46]);

- Unemployment (included as an unemployment rate; the positive correlation between unemployment and income inequalities was expected [47,48]);

- Good governance (measured by using six global governance indicators (Worldwide Governance Indicators—WGI); studies indicate positive effects of good governance on pro-poor growth and thus inclusive growth as well [49,50,51,52]).

Good management is relevant to the development of inclusive growth because it positively affects per capita income and poverty reduction [53]. Governance is defined as using economic, political, and administrative authority to manage state affairs at every level. Management includes processes, mechanisms, and institutions through which citizens express their interests, benefit from rights, or fulfill their duties [54]. According to a different definition, management is a process through which power is executed in management of political, social, and economic institutions in a given country [55]. The World Governance Indicators is a project that reports collective and individual management indicators for over 200 countries in 1996–2000. Methodology and structure of WGI indicators were designed by Kaufmann and Kraay [56]. Measured areas within the governance include [57]:

- Voice and accountability

- Political stability and absence of violence/terrorism

- Government effectiveness

- Regulatory quality

- Rule of law

- Control of corruption

Table A1 (Appendix A) presents the WGI results for the European Union countries (without Great Britain) in 2020. The results of governance were calculated for each of the examined areas separately. Table A1 includes the results for each country in the area of: voice and accountability, political stability and absence of violence/terrorism, and government effectiveness. Governance is an indicator that oscillates between minus 2.5 to plus 2.5. The table also presents percentile ranking for individual countries. It must be noted here that the table presents only the results for 27 countries and the percentiles were calculated for the whole group examined in 2020, which covered about 214 territories and countries.

Taking the first criterion into consideration, i.e., voice and accountability, it can be noticed that in 2020 the countries that were in a group of over 90 percentiles, i.e., showing the highest governance indicator in the examined area included: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and Sweden. The lowest positions of below 60 percentiles were noted for Bulgaria and Hungary. In the area of political stability and absence of violence/terrorism the governance indicator was generally lower; fewer countries were over the 90th percentile and it was only Luxemburg from 27 examined EU countries, and the countries of below the 60th percentile included Cyprus, France, Greece, Italy, and Spain. In the case of the third area of government effectiveness, the following countries achieved a governance indicator of over 90th percentile: Austria, Denmark, Finland, Ireland, Luxemburg, Netherlands, and Sweden. Bulgaria and Romania were below the 60th percentile.

In turn, Table A2 (Appendix A) presents the governance indicator in the subsequent three examined areas, i.e., regulatory quality, rule of law and control of corruption.

The governance indicator in the area of regulatory quality of over 90 was noted in such countries as: Austria, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Ireland, Luxemburg, Netherlands, Germany, and Sweden. None of the examined EU countries were found below the 60th percentile in 2020. Another area is rule of law, where the countries over 90 included Austria, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Luxemburg, Netherlands, and Sweden. Only Bulgaria was below the 60th percentile. The last of the studied areas of governance was control of corruption. Here in 2020, the best position, i.e., over 90 belonged to such countries as: Austria, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Ireland, Luxemburg, Netherlands, Germany, and Sweden. The group of below 60 included Bulgaria, Greece, and Romania.

This is the economic policy including monetary and fiscal policy that plays a crucial role in good management in a given country, and thus affect the reduction of poverty and inclusive growth. Some authors indicate that, namely, e.g., fiscal policy is a crucial tool in income division, and thus, apart from the government efficiency an institutional feature of good management is important, i.e., strong rule of law guaranteeing property rights, business regulations, and efficient compliance by the legal system [58].

It is also worth analyzing the SGI (Sustainable Governance Index) index in the context of impact of economic authorities on sustainable growth. This indicator enables to comprehensively examine sustainable development in the OECD and EU countries. The need for such an indicator results primarily from the fact that in the globalized world several significant challenges have emerged, such as the phenomenon of economic power, social inequality, aging societies, depleting resources, growing public debts, lack of equal opportunities in the labor market, education, or healthcare. These and other challenges are faced by the governments, which should be flexible in their actions and implementation of policies to meet them. SGI as an indicator that examines how governments strive for sustainable development is based on three pillars [59,60]:

- Policy performance (in this respect, it is checked whether governments care for social, economic, and environmental conditions. The objectives in specific policy areas are monitored here:

- ✓

- Economic policies—economy; labor markets; taxes; budgets; research, innovation and infrastructure; global Financial System;

- ✓

- Social policies—education; social inclusion; health; families; pensions; integration; safe living; global inequalities;

- ✓

- Environmental policies—environment; global environmental protection.

- Democracy (in this respect, trust in governance mechanisms and institutions is examined). In this area the tested features include:

- ✓

- Quality of democracy—electoral processes; access to information; civil rights and political liberties; rule of law.

- Governance (in this area the long-term vision of public policy is examined and the extent to which the institutional solutions of a given country increase the capacity of the public sector to act. This area takes into account:

- ✓

- Executive capacity—strategic capacity; interministerial coordination; evidence-based instruments; societal consultation; policy communication; implementation; adaptability; organizational reform;

- ✓

- Executive accountability—citizens’ participatory competence; legislative actors’ resources; media; parties and interest associations; independent supervisory bodies.

The idea of SGI is to support the ability of the OECD and EU countries to act on a long-term basis and to achieve the most sustainable policy outcomes. As a result, the SGI includes 67 qualitative indicators. The SGI indicator is a questionnaire survey where respondents from 41 countries answer the questions by giving points from the scale of 1 to 10 for each question. Finally, the SGI assessment ranges from 1 (the lowest score) to 10 (the highest score) [61]. Table A3 (Appendix A) presents the SGI results for the EU countries in 2020 in three main criteria of the SGI indicator, i.e., policy performance, democracy, and governance, taking into account the areas distinguished under these three mentioned criteria.

Taking into account the first criterion—policy performance—and three areas identified, the highest SGI indicators in 2020 were achieved by: Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Luxemburg, Germany, Estonia, and the Netherlands. In turn, the worst results were recorded in such countries as: Greece and Cyprus. In terms of SGI—democracy—the best performers were: Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Germany, Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia, and the worst were: Hungary, Poland, and Romania. Under the criterion of Governance, the best results were recorded by the following countries: Sweden, Finland, Germany, Denmark, Estonia, and Lithuania, and the worst results were recorded by: Romania, Hungary, Cyprus, and Croatia. Taking into account all three criteria of the SGI indicator in the EU in 2020, the following countries were ranked highest: Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Estonia, as well as Lithuania, and the lowest SGI rankings were observed in: Cyprus, Hungary, and Romania.

It is worth mentioning here that the results of SGI in 2020 were significantly influenced by the COVID-19 crisis. Hartmann concludes that for developing and emerging countries, the COVID-19 crisis arguably appeared at the worst possible moment in their political and economic development [62]. Similarly, in numerous industrialized countries the SGI proved to be sensitive to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the research by Bertelsmann Stiftung in 19 developed countries of the EU and 41 out of OECD surveyed countries, political polarization became a major brake on policy making even before the COVID-19 crisis. The authors of this study indicate that strong democracy and good governance often go hand in hand with sustainable policy outcomes in a country. Moreover, trust in the mechanisms and institutions exercising power allow society to react more decisively and appropriately to changes, even in times of crisis [63].

In summary, it is worth referring to the Nordic countries such as Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden, which record the highest scores in achieving inclusive growth. The basis of the so-called Scandinavian model is a strong economy with high levels of employment and productivity that generates the resources needed to support social services. Moreover, the model is based on the flexibility to adapt to changes in trade and technology. For instance, in Denmark, which enjoys one of the highest standards of living in the world, strong institutions are essential as together with sound economic and social policies, they ensure high economic indicators and high inclusive growth. According to the well-being results, the Danes as well as citizens of other Nordic countries turn out to be the happiest in the world, which, as mentioned above, is related to the level of inclusive growth. The “Swedish model” seeks inclusive growth by pursuing three objectives: flexibility in the labor market, universal healthcare system, and an economic framework that promotes openness and stability. To meet these objectives, strong public finances, trust in the system, and high employment as well as strong social partners are needed [64]. Such a balanced fiscal policy, stable monetary policy as well as trustworthy public institutions contribute to the achievement of the highest measures of inclusive growth, which is the case in the Nordic countries and others that make similar economic and social policy decisions.

4. Materials and Methods

The conducted empirical study was aimed at measuring the level of inclusive growth in the counties of the European Union by means of a pseudo-single-feature index, calculated by the weight correlation method. (We used the specific method (pseudo-single-feature indicator) in the study because, unlike cluster analysis (in fact the most frequently used in this type of research), it eliminates risks resulting from the use of centroids and the distance from them (in cluster analysis observations are grouped centrally). It often happens that in cluster analysis it is impossible to distinguish some ‘obvious’ groups. In the correlation weighting method, an index is calculated which allows to unambiguously assign an object to a group. The essence of the correlation method lies in the application of the Pearson linear correlation coefficient between pseudo-single-factorial variables and the final index, which enables the construction of a synthetic index). The calculations included 42 diagnostic variables, which based on the desk research were distinguished in three areas:

- Economic,

- Financial,

- Non-wage.

Based on the literature and the adopted assumptions, it was decided to construct an inclusive growth indicator. It was assumed that the variables used in the study as stimulants have a positive effect on the level of the inclusive growth index, while de-stimulating variables have a negative impact on the described phenomena. The variables collected in the above system were first transformed, which aimed at unifying the nature of the variables (the postulate of uniform preference), bringing dissimilar variables to mutual comparability (the additivity postulate) and replacing the different ranges of variability of individual variables with a constant range (the postulate of constancy of the range or the consistency of extreme values). The following types of variables were distinguished:

Stimulants —variables whose high values are desirable from the point of view of general characteristics of the studied phenomenon,

De-stimulants —variables whose high values are undesirable from the point of view of general characteristics of the studied phenomenon.

Table 1 presents variables used in the study along with their description and division into stimulants and de-stimulants.

Table 1.

Variables used to build an inclusive growth indicator.

The above-identified were divided into three groups of diagnostic variables [66] of inclusive growth and then characterized as stimulants and de-stimulants. The determinants of inclusive growth are related economic, financial, and non-wage factors influencing the growth rate of an inclusive economy in the context of the theory of sustainable finance. The theory of inclusive growth is based on the conviction that the source of economic success is the effective use of natural resources, capital goods, and human and technological resources. These factors significantly affect the value of goods and services developed in the economy. The economic growth indicated among economic factors, measured with GDP per capita, is the basic and best known measure of the competitiveness of the economy. Among the above-mentioned variables, it is worth paying attention to three categories of factors that are most often indicated in the literature on the subject as factors determining economic growth. In this article, they have been identified as inclusive growth factors. Among the variables presented in the table above, the following should be emphasized: government expenditure (expenditure on R&D, expenditure on health care, expenditure on education and expenditure on social purposes). All of them were classified as inclusive growth stimulants. As for these variables, numerous studies can be found that indicate the positive impact of government spending on economic growth. For example, Ghosh and Gregorio [67] showed in their research that public spending had a positive and significant impact on economic growth in the group of 15 analyzed developing countries. Similar studies were carried out by Benos [68], who found that public spending in the area of infrastructure and human capital has a significant impact on the long-term growth of a group of 14 EU countries. Another group of variables are the variables describing the components of trade and FDI (balance of payments as % of GDP; FDI as % of GDP; share of investments by institutional sectors as share of GDP; investment position; and trade openness). All of them were classified as inclusive growth stimulants. With regard to these variables, research indicates that economies that are open to world trade have higher GDP per capita and grow much faster (Romer [69]; Barro [70]). In the context of inclusive growth, a variable that has a significant impact on its level is FDI. De Vita and Kyaw pointed out that FDI has a direct impact on the sectors of economies in which FDI has been located. At the same time, their indirect impact on the overall productivity of the economy was emphasized [71]. Among the economic factors, the household savings rate was classified as a de-stimulant of inclusive growth. According to a simple definition, saving consists in giving up current consumption for the sake of future consumption. On the one hand, the transformation of savings into investments contributes to economic growth, however, often forgotten is a phenomenon that occurs commonly, in the economy referred to as the “saving paradox” [72]. An important group of factors that determine inclusive growth include non-wage factors, such as: government efficiency, political systems, cultural and social factors, geography, and demography. In this article, the following variables have been distinguished: the house price index; Km of highways per 1000 sq km; number of self-employed people aged 15–64 in %; number of patents per capita; life expectancy in years; % of households using broadband Internet; % of people aged 25–64 with higher education; % of people at risk of social exclusion; % of crime, violence, and vandalism; unemployment rate in the age of 15–74; average number of flats per 1 person in a household; voice and accountability; political stability and absence of violence/terrorism; government effectiveness; quality regulators; rule of law; control of corruption. A good example of a study that fits well with that carried out in this paper is that carried out by Arush [73]. The researcher analyzed the impact of individual management factors in economic growth for 71 countries: developed, developing, and undergoing transformation from 1996–2003. The results showed that countries with a high level of governance in areas of government administration at various levels develop faster compared with those characterized by a lower level of governance [73].

Subsequently, the variables were unified [74]. Unitarization is obtaining variables with a uniform range of variability, defined by the difference between their maximum and minimum values in the classical approach. In the case of classical unitarization, the normalization parameters most often assume the following values:

As a result of the application of the above normalization formula, we obtain variables with values belonging to the interval (0; 1) [74].

In further calculations, the variables were unitized in the following way:

In the case of de-stimulants:

In case of stimulants:

In the case of positive variables, the value equal to 1 was obtained by the economy with the highest index among all the respondents. On the other hand, negative variables took the values equal to 1 for the economies that were characterized by the lowest negative phenomenon index. The results obtained in this way were then used to calculate the correlation coefficients between the preliminary inclusive growth index and the coefficients calculated for each of the factors included in the study. To calculate the correlation coefficients, the Pearson correlation index was used, which describes the linear relationship between the variables.

In accordance with the weight correlation method, the obtained correlation coefficients were then used as weights for the weighted average and the average was recalculated. These actions are repeated until the correlation coefficients stabilize. The results obtained after the second iteration [74] (using the weighted average) present the final values of the inclusive development index for the EU economies. The indicators calculated using this method will be compared and analyzed in the following parts of the work for 2000, 2008, and 2020. In the article, for the purposes of comparison, three years were selected for the study: 2000, 2008, and 2020. These are the years in which the first clear symptoms of the coming crises or the effects of previous crises appeared. The analysis of the experiences of the EU countries during the first two economic crises (introduced financial, economic, and social solutions) may be an example of crisis management practices that proved successful or not in the EU countries in connection with another crisis caused by COVID-19.

The selection of the years used for the study is related to the periods of crises in the financial markets. In 2000, we dealt with the so-called Internet bubble, i.e., a period of euphoria on stock exchanges around the world associated with companies from the IT industry and related sectors. Its characteristic feature was the overestimation of enterprises that operated on the Internet or intended to start it. In 2008, however, there was a global financial crisis. The favorable situation on the mortgage loan market is assumed to be the direct cause of the global financial crisis since mid-2007. These were subprime loans, i.e., loans with higher risk granted by U.S. banks. These loans were used as collateral for structured bonds sold by private financial institutions, including the largest American and European banks. In the real estate market, growth continued, and rating institutions gave these bonds high ratings, so awareness of their riskiness was negligible. The insolvency of individual entities also increased significantly, which resulted in the shortage of cash in the credit market and the instability of these institutions. Since the beginning of 2020, the entire world is facing the COVID-19 crisis. The shock caused by the pandemic made it necessary to implement many fiscal policy tools in EU economies. As the numerical data show, in July 2020 the value of the total of 1250 implemented aid tools amounted to approximately EUR 3.5 trillion, i.e., 27% of the gross domestic product of the EU-27. The implemented programs included activities aimed at counteracting the negative effects of the economic crisis by maintaining jobs and liquidity support for SMEs. However, it should be remembered that the fiscal policy tools involved will lead to an increase in budget deficits and the levels of public debt in individual economies [75]. The United Kingdom was excluded from the analysis due to the recurring deficiencies in the data obtained from the Eurostat database. The study included 27 European countries that are members of the community.

Additionally, all the economies covered by the study were grouped into six classes of inclusive growth. The class intervals were calculated based on the arithmetic mean and standard deviation of the calculated values of inclusive growth indicators based on the methodology of Godlewska-Majkowska [74]. On the basis of the obtained statistics, six classes of inclusive growth were determined (from the most developed class A to the F class, which includes the least inclusively developed regions). These classes are left as closed compartments with the lower limits:

Class A: arithmetic mean + standard deviation,

Class B: arithmetic mean + 0.5 × standard deviation,

Class C: arithmetic mean,

Class D: arithmetic mean − 0.5 × standard deviation,

Class E: arithmetic mean − standard deviation,

Class F: 0.

All countries covered by the study were grouped into 6 classes of inclusive growth. The class intervals were calculated based on the arithmetic mean and standard deviation of the calculated ratios after all iterations in the economic, financial, and non-wage areas (detailed calculations are presented in the Appendix A—Table A4). The mean values and standard deviations for examined years are presented in the Tables 3, 5 and 7

5. Results

The study of inclusive growth in 2000, 2008, and 2020 allows for recognizing the directions of changes taking place in European economies, with particular emphasis on the moments of economic crises and decisions made by economic authorities in the studied countries. Over the analyzed years, significant changes took place among the EU-27 countries in terms of inclusive growth. The conditions and the direction of changes in the scope of inclusive growth are presented in the tables below. Table 2 shows the rate of inclusive growth of 27 European Union countries belonging to a designated class in 2000.

Table 2.

The level of the inclusive growth index with partial calculations for individual variables grouped by areas in 2000.

As it was explained in the earlier stages of this study, each of the analyzed economies was classified into one of the six classes of inclusive growth. Inclusive growth classes were isolated as left-closed intervals with lower limits based on the arithmetic mean and the standard deviation of the calculated inclusive growth index. In 2000, these values developed in accordance with Table 3.

Table 3.

Classes of inclusive growth in 2000.

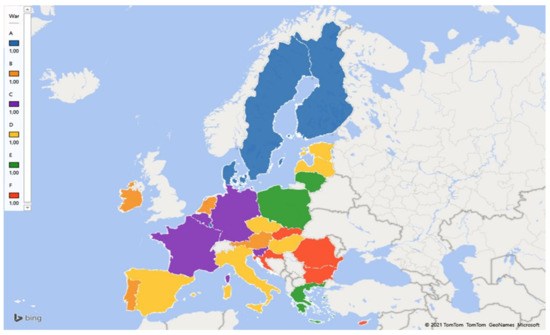

The division of economies presented above shows that the most numerous group was class D (six countries), while only four countries out of 27 were in the elite group. In 2000, the countries that were at the forefront of the ranking (class A) were: Denmark, Luxemburg, Finland, and Sweden. These countries achieved high values of partial indices being the arithmetic mean of the features in three studied areas (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Inclusive growth index for EU-27 in 2000 broken into classes. Source: Own study based on Eurostat data [65].

When analyzing the arithmetic means of variables belonging to the area of economy, it turns out that the average value of the coefficient for all analyzed economies is 0.50. The countries in group A with the highest inclusive growth recorded the following values of this parameter: Luxemburg (0.73), Denmark (0.57), Finland (0.51), and Sweden (0.59). The largest disproportions can be noticed in the group of non-wage factors, for which the average value of this parameter was 0.52, while among the A-class countries, values oscillating significantly above the above-mentioned average dominated (Luxemburg—0.75, Denmark—0.62, Finland—0.67, and Sweden—0.65). It can therefore be concluded that the inclusive growth in the countries classified as class A in 2000 was largely shaped by above-average non-wage indicators, such as transport accessibility, the level of self-employment, the percentage of people with higher education, or the quality of management in the economy. These countries obtained equally high values in the group of financial factors, where the average value of the examined parameters oscillated around 0.44. As a counterweight, it should be noted that the countries located on the eastern border of the EU, such as Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Romania, and Slovakia performed the worst in this respect (definitely below the average: in the area of economy, the average is 26% lower than the average) from group A, in the area of finances by 37%, and in the area of non-wages by as much as 39%). In 2000, most countries qualified for classes B, D, and E, Poland (class E) was on a par with the level of inclusive growth with Greece and Lithuania. These economies were the worst in the area of non-wage factors (below the average).

Table 4 presents the results of inclusive growth index for the 27 EU countries and their class in 2008.

Table 4.

Levels of inclusive growth with partial calculations for individual variables grouped by areas in 2008.

As in the previous version of the study, in the first place, upper and lower limits were established for arithmetic means and standard deviations, which were the basis for determining inclusive growth classes in 2008 (Table 5).

Table 5.

Classes of inclusive growth in 2008.

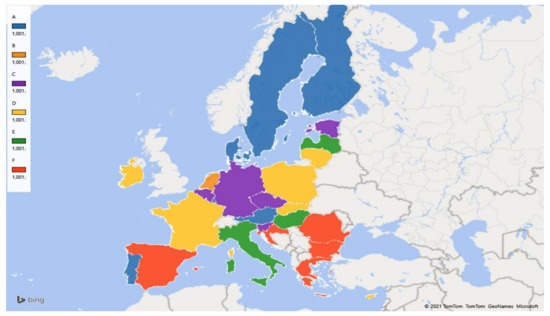

During the global financial crisis (2007–2009), European economies were forced to introduce many solutions in the field of public finances in order to be able to reduce and counteract its long-term effects. In 2008, the level of inclusive growth in European economies changed significantly. Figure 2 presents the map of the inclusive growth indicator for the EU-27 countries in 2008.

Figure 2.

Inclusive growth index for EU-27 in 2008 broken into classes. Source: Own study based on Eurostat data [65].

In Figure 2 it can be noticed that the A-class countries are economies that are many-year-old EU members: Denmark, Luxemburg, Austria, Portugal, Finland, and Sweden. It is therefore worth emphasizing that in maintaining inclusive growth during the crisis in A-class countries, instruments from the area of non-wage factors, and then economy and finance, played an important role, in which the average values for these countries exceeded the average for a given area (non-wage factors): EU average 0.52, and for A-class countries—average 0.66; economy—EU average is 0.47, and for A-class countries—average 0.55; finance—EU average is 0.46 and for A-class countries—average 0.54. During the crisis, the inclusive growth was halted in Ireland and Malta (drop from B to D and C).

The last research period undertaken in this study covers the year 2020, i.e., the moment when all European economies were affected by the crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Table 6 presents the results of the inclusive growth index of the 27 European Union countries and their belonging to a designated class in 2020.

Table 6.

The level of the inclusive growth index with partial calculations for individual variables grouped by areas in 2020.

The separation of the classes presented in Table 6 results from the previously established data, analogically to the previous versions of the study, and the lower and upper limits of the inclusive growth index, which in 2020 are at the level presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Classes of inclusive growth in 2020.

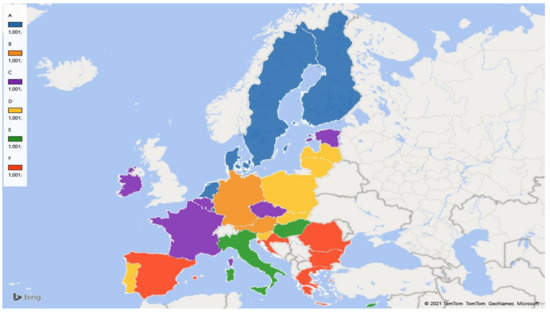

In 2020, the economies of Denmark, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Finland, and Sweden qualified for class A. In these countries, the partial rates of inclusive growth were much higher than the average for the EU. In the area of economic factors, the average for the analyzed economies was 0.504, while the above-mentioned countries averaged 0.60. Similarly, in terms of financial factors, the average of which for the EU countries was 0.534, and for the A-class countries was 0.567; for the non-wage factors, the average for the EU was 0.518 and the average for the EU countries was 0.715. Thus, there was a noticeable change in the group of economies characterized by the highest indicator of inclusive growth. Austria dropped out of class A, which returned to class B in 2000 (it recorded a decrease in average values of non-wage indicators by 4% compared with the EU-27 average). The economy of Portugal also underwent an unfavorable change (change from position A in 2008 to position D). Based on the example of this country, it can be observed that the deteriorating indicators determining inclusive growth through the prism of economic and non-wage factors had a major impact. The promotion to class A of the Netherlands, which in the previous analyzed years was respectively in B position in the previous years, was quite a surprise. In the case of the Netherlands, the economy recorded high rates in all areas (in the economy by 12% higher than the EU-27 average, in finances by 6% higher than the EU average, and non-wage income by as much as 36% higher than the EU average). At the end of the ranking of the EU-27 economies in 2020 there are Bulgaria, Greece, Spain, Croatia, and Romania. These economies recorded lower average values in the area of: economy by 17%, finance by 6%, and non-wages by 32% compared with the averages calculated for all EU-27 countries. Figure 3 presents the inclusive growth index in the EU-27 countries in 2020.

Figure 3.

Inclusive growth indicator for the EU-27 in 2020 by class. Source: Own study based on Eurostat [65].

The analysis of the values calculated for each of the areas of inclusive growth led to the conclusion that non-wage factors, which are directly related to prosperity, favorable conditions for running a business, and the quality of management from the point of view of state policy, play an important role in shaping it. However, economic factors, often resulting from decisions taken at the European Union level, and financial factors resulting from domestic decisions are not without significance. The values of the indicators describing individual areas showed that financial factors have a smaller impact on inclusive growth than economic factors. In each of the analyzed years, it turned out that the average for the area of finance ranged from 0.43 to 0.53, while for the economy this parameter oscillated around the value of 0.50 in each of the years, and for non-wage factors, the average was about 0.51.

6. Discussion

There is a clear discrepancy between economic growth and social development. Social development lags behind economic development, which leads to increasing income disparities, maintaining a high level of unemployment, social exclusion, and increasing social tensions. In the related literature it is often emphasized that the cause for such a state is the liberal economic system and world crises lasting several years. When analyzing the factors determining inclusive growth, it is worth emphasizing the changes that took place in individual European economies at the turn of the years 2000–2020. The year 2000 is a time of economic slowdown, then 2008 is the beginning of the financial and economic crisis in Europe, which turned into a debt crisis in the public finance sector, and finally 2020—the COVID-19 crisis, the time of a pandemic that negatively affected the economy and society of every European Union country. Each of the analyzed economies of the EU-27 is different and each of the EU countries reacts differently to economic shocks or other crises [76]. Hence, in order to relate the obtained research results to the economic situation in individual countries, Table 8 contains the most important conclusions of the analyses, which were extended to include aspects of fiscal and monetary policies and governance in individual countries of the EU-27.

Table 8.

Classification of European economies in the analyzed years 2000–2020, including the most important factors determining changes.

The study showed that over the years, in the period of the greatest crises, only a few economies were able to maintain a high level of inclusive growth with the help of properly implemented monetary, fiscal, and governance policies. These were: Denmark, Luxembourg, Sweden, and Finland. The Nordic countries are at the top of the inclusive growth index in each of the analyzed years, showing high economic and social performance among the EU countries. These economies follow restrictive fiscal policies [79] to stimulate economic growth. Moreover, they are in the top positions in terms of GDP per capita, labor productivity, and employment rates among developed economies. (When developing a new set of measures of growth and development conducive to inclusive growth, it is worth considering the shortcomings of GDP at this point. GDP is the most widely used measure of a country’s economic progress and is considered a useful measure of the competitiveness of economies, particularly in terms of added value and productivity. GDP is also related to other economic measures such as employment. While the concept of GDP has always been defined and classified solely as a measure of economic activity, it has often been used as an indicator of well-being. In recent years, there have been concerns that GDP is no longer sufficient to measure economic and social activity, and there is a need to conduct research on other measures of this phenomenon. In addition to GDP, it is increasingly emerging in the debate to develop indicators of progress, factors that integrate more other measures of well-being, including environmental, social, and quality of life aspects. There are two reasons for going beyond GDP: constraints on GDP as a measure of production; and restrictions on the use of GDP as a measure of social and economic progress. So far, GDP remains the base measure, i.e., the one with which the analysis of socioeconomic growth starts). The Nordic countries’ long-term vision for a sustainable and inclusive economy is reflected in low income inequalities, high median living standards, and low carbon emissions. These countries also have high levels of citizen satisfaction and prosperity, with generous social security programs for pensions, education, and public housing. Moreover, the Nordic countries are exceptionally good at promoting inclusive growth and its development. At the end of the ranking (class F), in each of the analyzed years, the following were qualified: Bulgaria, Croatia, and Romania. As these countries face a historic opportunity to chart a better way forward (they are the beneficiaries of the EU’s financial policy), they will need to implement major reforms in terms of fair mobilization of resources, implement remedial measures in the private sector, and implement the necessary investments to move to a more sustainable and inclusive development. The results of these changes may contribute to inclusive growth, however in the long run, unwavering by any economic crisis.

The calculated inclusive growth rates in 2000, 2008, and 2020 show a significant similarity with the Inclusive Development Index (IDI), in which the aggregated factors are included in the following areas: growth and development (factors: GDP per capita, labor productivity, healthy life expectancy, and employment), inclusion (factors: net income Gini, poverty rate, wealth Gini, and median income), and intergenerational equity and sustainability (factors: adjusted net savings, carbon intensity, public debt, dependency ratio). The established IDI values showed that in 2018, among European countries, Norway, Ireland, Luxemburg, and Denmark were in the top four of the ranking, while at the end of the ranking there were such countries as: Greece, Portugal, and Italy [80]. Similar conclusions can be found in the study by Zielenkiewicz, which, using the Ward’s method, classified economies in terms of the obtained IDI indicators. The results of the research showed that the countries with the highest inclusive rate include: Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, while the last class includes: Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain [81].

The results presented in this study confirm the rankings carried out by other institutions and researchers. Obviously, it was confirmed that the ranking in terms of GDP per capita only lowers the ranking of countries that care about sustainable socioeconomic development. In the rankings of development alternative to GDP per capita, the quality of life in a given country is appreciated. In the Human Development Index (HDI), 2018, the first place was taken by Norway and Sweden—the 8th place—while in the Global Competitiveness Index (GCI), Sweden was 9th, Denmark 10th, Finland 11th, and Norway 16th place. Moreover, in terms of the social progress index (Social Progress Impera-tive-SPI-2018), the rankings were as follows for countries such as: Norway (1st place), Denmark (4th place), Finland (5th), and Sweden (11th place). The results of the newly published Responsible Development Index, RDI (prepared by the Polish Economic Institute and published from 2019), are also worth noting. This indicator is an alternative to GDP and measures a country’s development. A total of 159 countries were included in the ranking. The RDI indicator is based on four pillars: (1) Current well-being; (2) Creating future well-being; (3) Non-wage well-being; and (4) Climate responsibility. According to the RDI, the most developed economies in the world are Sweden, Denmark, and Norway [82]. In addition, the Nordic countries dominate in the field of education, in the welfare state, happiness, and sustainability rankings. The RobecoSAM ranking takes into account the position of countries in terms of environmental investment, social investment, and governance. According to this ranking, Norway is perceived as the most sustainable country in the world. Sweden, Finland, and Denmark also top the list for their respective policies on governance, innovation, human capital, and climate indicators. It is the policy of the economic authorities that is of great importance in the pursuit of a given country for economic, social, and environmental development. Similar actions for sustainable development are undertaken in Finland. An example is the Sitra, established more than 50 years ago, which is an innovation fund established by the parliament to promote a new model of society. Sitra supports innovative, sustainable, and effective projects in the economy to shape the future. In turn, Denmark is a pioneer in the transition to a green, sustainable economy [83].

The practical contribution of the conducted research may be manifested in the analysis of the weights of the groups of variables used in the construction of the inclusive growth index. This analysis makes it possible to identify the groups of variables that favorably or unfavorably affect the level of inclusive growth. This allows, in particular, to develop a set of variables, the results of which should be significantly improved as they weaken the overall inclusive growth rate in a given country. Similarly, one can look at the countries with the highest inclusive growth rates to indicate a set of factors of the greatest importance for its level. The directions of future research can be summarized in several points:

- The inclusive growth rate can be extended to include factors from the climatic area;

- More advanced statistical-econometric research methods can be applied;

- It is worth focusing more on using the digital revolution to promote sustainable development;

- It is also important to strengthen the social model and focus of public authorities on societal welfare.

7. Conclusions

Undoubtedly, the analysis of inclusive growth does not only refer to macroeconomics and governance but also to the values and prosperity of a given society. In this article, while looking for a measure of inclusive growth in the EU-27 countries, the 42 used variables were deliberately divided into three groups, i.e., determinants from the area of economy, finance, and the so-called non-wage factors. This division also made it possible to observe how in the analyzed years 2000, 2008, and 2020 the strength of the influence of factors from these three analyzed areas on the inclusive growth indicator in the EU-27 as well as in individual countries changed. These results can also be related to the impact and significance of the decisions of economic authorities in the field of fiscal policy, monetary policy, and governance on the shaping of the factors that make up the inclusive growth index. In summary, only four countries from the 27 EU countries (Denmark, Luxembourg, Sweden, and Finland) achieved the highest rate of inclusive growth in the three analyzed years 2000, 2008, and 2020. In turn, three of the EU-27 countries (Bulgaria, Romania, and Croatia) showed the lowest inclusive growth in each of the analyzed years. On average, in each of the analyzed years, non-wage factors, followed by economic and financial factors, had the largest share in inclusive growth. However, it can be concluded that most of the selected factors influencing inclusive growth are significantly influenced by decisions of economic authorities [84]—governments, central banks, and other institutions of public trust—and that these institutions are responsible for taking steps to make more than four of the countries included in group A—that is, countries with the highest inclusive growth. Of course, many decisions of economic authorities are associated with many limitations and obstacles, such as supply shocks, financial and economic crises, or pandemics such as COVID-19. Sustainable finances, stable monetary policy, and trust-inspiring public institutions contribute to the achievement of higher rates of inclusive growth, which is the case in the Nordic countries or in Luxembourg.

Among the limitations of the study, several elements can be indicated:

- EU countries are economically and politically diverse;

- The level of economic integration of EU countries is also diversified;

- There is an asymmetry in budgetary and practical cycles in the EU countries;

- There is a divergent approach by economic authorities to the erosion of social protection and exclusion across the EU;

- In the developed index of inclusive growth, factors of significant importance for its level may have been omitted.

Certainly, inclusive growth in each of the surveyed countries is influenced by many factors that cannot be combined in one indicator. These factors are also influenced by the decisions of economic authorities and other institutions of public trust, the effects of which are disrupted by internal and external economic impulses, financial crises, and other random events. This gives a field for further analysis and research on inclusive growth by constructing panel or logit models. Fundamental reforms need to be introduced in order to pursue inclusive growth in most EU economies, and there is a need for a global and collective contribution to socioeconomic development at all levels. Public and private investment must be mobilized, the social model must be strengthened and internal demand and openness to trade must be increased, and appropriate interactions in society should be promoted. It is the well-being of society that should be placed at the center of any new socioeconomic policy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S. and M.J.; methodology, M.J. and J.S.; software, J.S. and M.J.; validation, J.S. and M.J.; formal analysis, J.S. and M.J.; investigation J.S. and M.J.; resources, J.S. and M.J.; data curation, J.S. and M.J.; writing—original draft preparation, J.S. and M.J.; writing—review and editing, J.S. and M.J.; visualization, J.S. and M.J.; supervision, J.S. and M.J.; project administration, J.S. and M.J.; and funding acquisition, J.S. and M.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The article is part of a research project financed by the National Science Centre, Poland (grant no. UMO-2017/26/D/HS4/00954).

Data Availability Statement

European Commission. Eurostat Database. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database (accessed on 29 October 2021).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Maciej Malaczewski, Professor from the Institute of Econometrics, Faculty of Economics and Sociology, University of Lodz, for consultations and substantive assistance during the preparation of the article. Malaczewski’s suggestions contributed to a significant improvement in the quality of the content contained in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Worldwide Governance Indicators in European Union countries in 2020, part 1.

Table A1.

Worldwide Governance Indicators in European Union countries in 2020, part 1.

| Country | Voice and Accountability | Political Stability and Absence of Violence/Terrorism | Government Effectiveness | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Governance (−2.5 to +2.5) | Percentile Rank | Governance (−2.5 to +2.5) | Percentile Rank | Governance (−2.5 to +2.5) | Percentile Rank | |

| Austria | 1.40 | 95.7 | 0.85 | 74.5 | 1.66 | 94.7 |

| Belgium | 1.28 | 90.8 | 0.59 | 64.6 | 1.12 | 83.7 |

| Bulgaria | 0.26 | 56.0 | 0.47 | 60.8 | −0.07 | 50.5 |

| Croatia | 0.58 | 64.3 | 0.61 | 65.6 | 0.44 | 68.8 |

| Cyprus | 0.91 | 75.4 | 0.29 | 56.1 | 0.88 | 77.4 |

| Czech Republic | 0.98 | 79.2 | 0.92 | 79.2 | 0.96 | 78.8 |

| Denmark | 1.52 | 97.6 | 0.94 | 81.6 | 1.89 | 98.1 |

| Estonia | 1.17 | 88.4 | 0.71 | 70.3 | 1.34 | 88.5 |

| Finland | 1.62 | 99.5 | 0.94 | 82.1 | 1.95 | 99.0 |

| France | 1.07 | 82.6 | 0.31 | 56.6 | 1.25 | 86.5 |

| Germany | 1.38 | 94.2 | 0.67 | 68.9 | 1.36 | 88.9 |

| Greece | 0.97 | 78.7 | 0.13 | 51.4 | 0.44 | 69.2 |

| Hungary | 0.39 | 58.9 | 0.86 | 75.0 | 0.58 | 72.1 |

| Ireland | 1.39 | 95.2 | 0.98 | 83.0 | 1.48 | 90.9 |

| Italy | 1.06 | 82.1 | 0.44 | 59.9 | 0.40 | 67.3 |

| Latvia | 0.87 | 73.4 | 0.46 | 60.4 | 0.88 | 76.9 |

| Lithuania | 1.01 | 80.2 | 0.87 | 75.5 | 1.06 | 82.7 |

| Luxembourg | 1.50 | 96.6 | 1.23 | 93.9 | 1.84 | 97.1 |

| Malta | 1.12 | 84.5 | 0.95 | 82.5 | 1.04 | 81.7 |

| Netherlands | 1.53 | 98.1 | 0.85 | 74.1 | 1.85 | 97.6 |

| Poland | 0.62 | 66.7 | 0.57 | 63.2 | 0.38 | 66.3 |

| Portugal | 1.26 | 89.9 | 1.03 | 85.8 | 1.02 | 81.3 |

| Romania | 0.58 | 65.2 | 0.59 | 63.7 | −0.22 | 42.8 |

| Slovak Republic | 0.88 | 74.9 | 0.64 | 67.5 | 0.54 | 71.6 |

| Slovenia | 0.94 | 78.3 | 0.71 | 69.8 | 1.17 | 85.6 |

| Spain | 1.01 | 80.7 | 0.40 | 58.0 | 0.89 | 77.9 |

| Sweden | 1.50 | 97.1 | 1.02 | 85.4 | 1.72 | 95.7 |

Source: WGI [57].

Table A2.

Worldwide Governance Indicators in European Union countries in 2020, part 2.

Table A2.

Worldwide Governance Indicators in European Union countries in 2020, part 2.

| Country | Regulatory Quality | Rule of Law | Control of Corruption | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Governance (−2.5 to +2.5) | Percentile Rank | Governance (−2.5 to +2.5) | Percentile Rank | Governance (−2.5 to +2.5) | Percentile Rank | |

| Austria | 1.40 | 90.9 | 1.81 | 97.1 | 1.51 | 90.9 |

| Belgium | 1.35 | 88.9 | 1.37 | 88.9 | 1.48 | 89.9 |

| Bulgaria | 0.52 | 69.7 | −0.09 | 51.4 | −0.27 | 46.2 |

| Croatia | 0.43 | 65.9 | 0.29 | 62.0 | 0.20 | 61.5 |

| Cyprus | 1.00 | 80.8 | 0.58 | 70.7 | 0.38 | 65.9 |

| Czech Republic | 1.24 | 86.5 | 1.06 | 83.2 | 0.59 | 71.2 |

| Denmark | 1.79 | 97.6 | 1.86 | 98.1 | 2.27 | 100.0 |

| Estonia | 1.54 | 92.8 | 1.38 | 89.4 | 1.61 | 92.3 |

| Finland | 1.85 | 99.0 | 2.08 | 100.0 | 2.20 | 99.5 |

| France | 1.20 | 85.6 | 1.33 | 88.0 | 1.15 | 84.6 |

| Germany | 1.58 | 93.3 | 1.56 | 91.3 | 1.86 | 95.2 |

| Greece | 0.55 | 72.1 | 0.32 | 63.0 | 0.06 | 58.7 |

| Hungary | 0.48 | 67.8 | 0.51 | 67.8 | 0.10 | 60.6 |

| Ireland | 1.47 | 91.8 | 1.50 | 90.4 | 1.57 | 91.3 |

| Italy | 0.50 | 68.3 | 0.24 | 60.6 | 0.54 | 69.2 |

| Latvia | 1.19 | 85.1 | 0.96 | 81.3 | 0.72 | 75.5 |

| Lithuania | 1.09 | 83.2 | 0.99 | 81.7 | 0.81 | 79.8 |

| Luxembourg | 1.84 | 98.6 | 1.79 | 95.7 | 2.06 | 96.6 |

| Malta | 1.22 | 86.1 | 0.92 | 78.8 | 0.37 | 64.9 |

| Netherlands | 1.75 | 96.6 | 1.76 | 94.7 | 2.03 | 96.2 |

| Poland | 0.89 | 76.4 | 0.54 | 69.2 | 0.65 | 73.1 |

| Portugal | 0.83 | 75.5 | 1.18 | 85.1 | 0.75 | 76.9 |

| Romania | 0.38 | 64.4 | 0.37 | 64.4 | −0.03 | 54.8 |

| Slovak Republic | 0.78 | 74.5 | 0.68 | 73.6 | 0.44 | 66.3 |

| Slovenia | 0.92 | 77.4 | 1.07 | 83.7 | 0.81 | 79.3 |

| Spain | 0.77 | 73.6 | 0.90 | 78.4 | 0.74 | 76.4 |

| Sweden | 1.68 | 95.2 | 1.81 | 96.6 | 2.13 | 98.1 |

Source: WGI [57].

Table A3.

Sustainable Governance Indicators for European Union countries in 2020.

Table A3.

Sustainable Governance Indicators for European Union countries in 2020.

| Country | Policy Performance | Democracy | Governance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Policies | Social Policies | Environmental Policies | Quality of Democracy | Executive Capacity | Executive Accountability | |

| Austria | 6.5 | 6.3 | 5.8 | 7.4 | 6.0 | 7.5 |

| Belgium | 6.2 | 6.4 | 5.8 | 7.3 | 5.5 | 7.6 |

| Bulgaria | 5.7 | 4.4 | 6.0 | 5.5 | 4.7 | 6.0 |

| Croatia | 5.2 | 4.9 | 6.2 | 5.7 | 4.2 | 5.4 |

| Cyprus | 5.0 | 5.6 | 4.1 | 6.0 | 4.0 | 5.2 |

| Czech Republic | 6.4 | 6.2 | 5.8 | 7.3 | 5.3 | 7.3 |

| Denmark | 7.9 | 7.8 | 8.1 | 8.9 | 8.4 | 8.3 |

| Estonia | 7.3 | 6.8 | 7.1 | 8.6 | 6.7 | 7.6 |

| Finland | 7.2 | 7.3 | 7.7 | 9.1 | 8.4 | 8.6 |

| France | 6.2 | 6.9 | 7.4 | 7.2 | 6.8 | 6.4 |

| Germany | 7.4 | 7.1 | 6.8 | 8.7 | 7.0 | 7.9 |

| Greece | 4.4 | 4.9 | 4.7 | 7.0 | 4.8 | 6.5 |

| Hungary | 5.4 | 4.6 | 5.9 | 3.4 | 4.4 | 4.7 |

| Ireland | 6.8 | 6.6 | 6.4 | 8.2 | 6.8 | 7.1 |

| Italy | 4.5 | 5.5 | 6.2 | 6.9 | 4.9 | 6.2 |

| Latvia | 6.7 | 5.2 | 7.1 | 7.9 | 7.5 | 5.3 |

| Lithuania | 6.9 | 6.0 | 7.0 | 8.1 | 7.2 | 6.8 |

| Luxembourg | 7.2 | 7.5 | 7.3 | 7.6 | 6.6 | 7.9 |

| Malta | 6.7 | 5.7 | 5.1 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 6.5 |

| Netherlands | 7.5 | 6.8 | 6.3 | 7.1 | 6.1 | 6.9 |

| Poland | 6.2 | 5.3 | 4.7 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 6.1 |

| Portugal | 5.8 | 6.0 | 6.2 | 7.6 | 6.2 | 5.8 |

| Romania | 4.9 | 4.6 | 6.0 | 4.9 | 4.1 | 4.9 |

| Slovak Republic | 5.7 | 5.1 | 5.7 | 6.5 | 4.4 | 6.1 |

| Slovenia | 6.1 | 6.6 | 6.5 | 7.3 | 5.0 | 7.1 |

| Spain | 5.6 | 6.5 | 6.7 | 7.3 | 6.6 | 6.6 |

| Sweden | 7.9 | 7.4 | 8.7 | 9.3 | 8.5 | 8.8 |

Source: [59].

Table A4.

Calculation of the inclusive growth rate for a selected country—Poland, for one year 2000.

Table A4.

Calculation of the inclusive growth rate for a selected country—Poland, for one year 2000.

| Economic Factors | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disposable Income Per Capita | GG Deficit/Surplus as % GDP | Gini index | Gross Fixed Formation (Share of Investments by Institutional Sectors as Share of GDP) | Gross Household Savings Rate (Gross Household Savings Rate) | Inflation | Consumption Per Capita | Investment Position | Purchasing Power Adjusted GDP Per Capita | |

| Stimulant (A)/destimulant (D) | S | S | D | S | D | D | S | S | S |

| Average index | 23,104 | −2 | 28 | 23 | 10 | 6 | 77 | −26 | 25,159 |

| Poland | 15,449 | −4.00 | 30.00 | 23.69 | 12.93 | 10.1 | 26.1 | −40.90 | 14,200 |

| Economic factors continue | |||||||||

| Real effective exchange | Short term interest rates—three mounts interbank interest rates | General Government debt jako % PKB | Labor costs (average hourly costs in euro) | Market openness | |||||

| Stimulant (A)/destimulant (D) | S | D | D | D | S | ||||

| Average index | −1 | 8 | 49 | 17 | 102 | ||||

| Poland | 9.70 | 18.9 | 36.4 | 7.11 | 60.00 | ||||

| Financial factors | |||||||||

| Balance of payments as % of GDP | FDI as % of GDP | Pensions in euro per capita | Households with a high financial burden due to the cost of living in% | % of households with credit arrears | R&D expenditure as % of GDP | Government spending on health care as % of GDP | Education expenditure as % of GDP | Social spending as % of GDP | |

| Stimulant (A)/destimulant (D) | S | S | S | D | D | S | S | S | S |

| Average index | 0 | 32 | 3,851 | 32 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 15 |

| Poland | 0.500 | 5.500 | 1,587.86 | 44.20 | 2.30 | 0.64 | 0.9 | 5.60 | 17.70 |

| Financial factors continue | |||||||||

| Private sector debt as % of GDP | Liabilities of the financial sector as % of GDP | ||||||||

| Stimulant (A)/destimulant (D) | D | D | |||||||

| Average index | 96 | −29.15 | |||||||

| Poland | 35 | −35.90 | |||||||

| Non-wage factors | |||||||||

| House Price Index | Km of motorways per 1000 sq km | Number of self-employed people aged 15–64 in % | Number of patents per capita | Life expectancy in years | % of households using broadband Internet | % of people aged 25–64 with higher education | % of people at risk of social exclusion | % of crime, violence, and vandalism | |

| Stimulant (A)/destimulant (D) | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | D | D |

| Average index | 66 | 16 | 62 | 0 | 76 | 14 | 34 | 28 | 10 |

| Poland | 56.01 | 1.00 | 54.70 | 0.00 | 78.20 | 4.00 | 20.20 | 45.30 | 2.30 |

| Non-wage factors continue | |||||||||

| Unemployment rate in the age of 15–74 | Average number of flats per 1 person in a household | Voice and accountability | Political stability and absence of violence/terrorism | Government effectiveness | Regulatory quality | Rule of law | Control of corruption | ||

| Stimulant (A)/destimulant (D) | D | D | S | S | S | S | S | S | |

| Average index | 9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Poland | 16.00 | 1.00 | 1.08 | 0.31 | 0.61 | 0.75 | 0.71 | 0.71 | |

| Standardization of comparable variables | |||||||||

| Economic factors (standardization, indicator for Poland) | Disposable income per capita | GG deficit/surplus as % GDP | Gini index | Gross fixed formation (Share of investments by institutional sectors as share of GDP) | Gross household savings rate (Gross household savings rate) | Inflation | Consumption per capita | Investment position | Purchasing power adjusted GDP per capita |

| 0.18 | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.48 | 0.24 | 0.80 | 0.10 | 0.52 | 0.06 | |

| Real effective exchange | Short term interest rates—three months of interbank interest rates | General Government debt jako % PKB | Labor costs (average hourly costs in euro) | Market openness | |||||

| 0.87 | 0.68 | 0.70 | 0.84 | 0.05 | |||||

| Financial factors (standardization, indicator for Poland) | Balance of payments as % of GDP | FDI as % of GDP | Pensions in euro per capita | Households with a high financial burden due to the cost of living in% | %of households with credit arrears | R&D expenditure as % of GDP | Government spending on health care as % of GDP | Education expenditure as % of GDP | Social spending as % of GDP |

| 0.500 | 0.011 | 0.088 | 0.339 | 0.842 | 0.113 | 0.121 | 0.758 | 0.676 | |