Abstract

This paper introduces a geoethical dilemma in the coastal zone of the Tordera Delta as a case study with the objective of showing the contribution of geoethics to the governance of coastal social-ecological systems. The Tordera Delta, located in Costa Brava, Catalonia, constitutes a social-ecological system that suffers from intense anthropization mainly due to tourist pressures causing a cascade of different environmental problems impacting the Delta functions. The massive sun and beach tourism brought human well-being and economic development to the region, but has caused an intense urbanization of the coastline that altered the coastal dynamics, eroded its beaches, and degraded many ecosystem services, a process that is being worsened today by the climate change events such as the rising sea level or the magnitude of the storms (“llevantades”), typical of the Western Mediterranean coast. Posing the problem of governance in terms of a geoethical dilemma enables discerning among the values connected to the intrinsic meaning of coastal landscapes and the instrumental values that see beaches as goods (commodities) for tourism uses. Finally, the paper reflects on options to overcome this dichotomy of values by considering meaning values as elements that forge cultural identities, contributing to highlighting this societal challenge in the Tordera Delta area, as a case study that can be useful for similar ecosystems.

1. Introduction

At the end of January 2020, Storm Gloria severely hit the Spanish Mediterranean coast resulting in substantial infrastructure and economic damage. The Tordera Delta (TD) located northeast of Barcelona (Catalonia) was especially affected. At the same time, however, the storm largely increased the amount of sediment reaching the shoreline, enlarging the beach’s recreational areas and creating a new lagoon at the mouth of the TD. The moral of this story is that society’s wellbeing increases its vulnerability with raised exposure to natural hazards, but benefits when natural ecosystem functionality is healthy and functional.

Delta areas are complex social-ecological systems (SES) where humans and nature meet and interact and frequent conflicts emerge. Policy and bureaucratic fragmentation often becomes an obstacle for advancing towards sustainable use of these coastal areas, highly vulnerable to natural forces and subject to stressful pressures by human interventions. Deltas constitute fragile habitats considering rising sea level due to climate change and the TD is a good case in point. Climate models for the future in Catalonia [1] suggest that climate changes will include changes in the intensity, duration, frequency, and spatial distribution of extreme events in the short, medium, and long term. Hence, encouragement is needed to promote bold adaptations, which imply improving our relation with Nature as soon as possible. The general regression and disappearance of sandy beaches on Catalonia’s Mediterranean coast, where the TD is located, is an issue of high social and economic significance since beaches support a tourist economic sector, which attracted almost 20 million tourists in 2019 [2]. Coastal regression is mainly due to the accumulative impacts of upstream dams retaining sediments, marine structures blocking sediment redistribution (sport harbors and marine breakwaters), and urbanization of coastal dunes and back shores [3,4], coupled with intensification of winter storms and rising sea level linked to climate change, according to the Laboratori d’Enginyeria Marítima and Centre d’Investigació dels Recursos Costaners de la Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, 75% of the sandy beaches are eroding and the average values of annual erosion are calculated at 1.7 m/year [ref added]. Due to these impacts, only 25% of the Catalonia’s coastal habitats have a favorable conservation status [5]. During the last 60 years, the low part of Tordera Watershed underwent drastic changes in modifying hydraulic conditions and land uses. Today, the area has developed industrial, agricultural, tourist and residential competing uses, exerting unsustainable pressures on natural processes. Twenty years ago, most stakeholders of the TD recognized that cumulative effects resulting from multiple activities carried out without any comprehensive planning resulted in a loss of the TD’s ecosystem functionality, putting the ecosystem resources and beaches in a critical state [ref added]. Since then, numerous studies and researches have been carried out by the Observatori de la Tordera (ICTA-UAB), the Institute of Environmental Science and Technology (ICTA-UAB); the Institució Catalana d’Història Natural (ICHN); the Blanes Centre for Advanced Studies (CEAB-CSIC); the Catalan Water Agency (ACA), and the Ecological and Forestry Applications Center (CREAF) as well as different universities, providing large amounts of data, and even a detailed hydrogeological numerical model for the TD, allowing a sound understanding of the key environmental problems.

However, the social issues of the TD remain a serious challenge. To implement an effective ecosystem-based management (EBM), as recommended by the EU policies, the involvement of the key stakeholders was required [6,7]. With this purpose, the Taula del Delta i de la Baixa Tordera (TDBT) was created in 2017 by key local stakeholders, aimed to become the governance body dealing with the issues and fostering a long-term planned approach. The purpose of the TDBT is to recover the social and ecological balances of the TD and to reduce its vulnerability to climate change by means of developing a strategic and integrated plan in a transparent and participatory manner, as explicitly established by the EU Water Framework Directive. However, despite having the data, knowing the problems, and the technical measures that should be implemented, and the existence of the TDBT, several barriers block the advancement towards an agreed solution. Finding new innovative approaches and perspectives seems crucial to overcome this blocked situation.

To analyze a potential way forward to unlock the governance of the social-ecological system of the TD, a Geoethical approach was proposed. Geoethics is an emerging frontier discipline—between ethics and geosciences—that looks at the values in how humans relate to the Earth System [8]. Existing frameworks for analyzing SES tend to be presented as neutral-value and do not adequately consider the axiological aspect of decision-making. However, understanding the values that underpin governance principles in SES (or in socio-ecological-technical systems “sensu Wesselink et al. [9]”) may be useful to reverse the unsustainable management of fragile and stressed geo-resources, such as coastal landscapes. In this paper, we use a workshop meeting (TD conference) to introduce a geoethical dilemma following geoethics.

This paper contributes to highlighting this societal challenge in the TD area, as a paradigmatic case study that can be useful for similar ecosystems. Several cases of success show the gains of this innovative approach, applying geoethics in governance processes [10,11,12,13,14] that have the potential to unblock the current barriers in the governance of the TD and will contribute to validate a methodology that might be replicated in other deltas along the Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts.

2. Methodology

2.1. The Tordera Delta Case Study

The TD is an area of great geo-strategic importance for the social and economic development of the region, hosting important activities i.e., tourism, agriculture, fishing, mobility, and environmental infrastructures. The TD refers to the river mouth of the Tordera River that flows into the Mediterranean Sea 70 km north of the city of Barcelona. The Tordera River drains in a basin area of ca. 880 km2 along 59 km and has a typical Mediterranean regime with 7.2 m3 s−1 mean water discharge at the middle of its course, long dry summers and sporadic floods and spring time. The TD is mainly composed of coarse sand derived from granitoid and metamorphic rocks of the pre-littoral mountains. Because of the coarse texture of the sand, the TD has a high permeability that facilitates water infiltration into the delta plain, where large aquifers can be found.

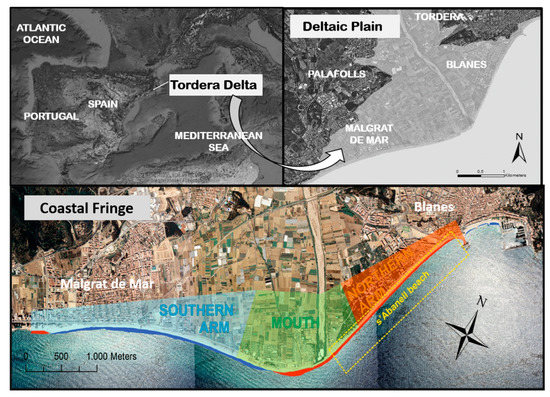

The TD region occupies ca. 20 km2, including coastal and inland area (Figure 1). The Delta partially includes the municipalities of Blanes, Malgrat de Mar, Palafolls, and Tordera, which have a total resident population of around 100,000 inhabitants. During the last 60 years, the TD area has undergone many changes in flow dynamics and lamination conditions, due to dredging activities, land use transformations and extractive water usages. A progressive abandonment of crops and farming areas, together with the growth of impervious soil, such as urban areas, added more pressures to the river system, which in turn influenced its coastal zone, reducing river water flow and river sediment contribution yielding large erosion processes in the TD beaches, one of the most important tourist assets in the area. Nevertheless, the TD area today continues to be an area of high tourist and residential potential, which exerts an enormous pressure to its natural resources but still it contains a highly productive agricultural area and the Blanes harbor still has relevant fishing activity.

Figure 1.

Location of the Tordera Delta [6].

Highly energetic storms hit the TD shores periodically, with common damages on Delta beaches, threatening the population and the touristic activities of this area. Beach erosion has a direct impact on touristic attractiveness. Several campgrounds located at the outer part of the TD plain, are the only existing tourist facilities. Their activity is strongly conditioned by the existence and maintenance of a wide and healthy beach but now beaches are in erosive tendency. To alleviate this trend, traditional sand extraction for beach nourishment, usually dredged at depths between 10 and 30 m in the wave-dominated delta front, has been ineffective, contra-productive and often leads to a complete defaunation of the benthic community. This had a critical impact on artisanal bivalves’ fisheries of the area. Furthermore, the TD constitutes a crucial site for environmental conservation (i.e., wetlands, habitat for protected species, hydrologic connectivity) being partly included in the European Natura 2000 Network. Altogether, many of the recent human developments in the TD have caused relevant conflicts between local private interests, regional projects and environmental protection due to the degradation of several ecosystem services [15,16].

The Catalan River Basin District Management Plan defines the aquifer of the lower part of the Tordera and the TD aquifer as strategic for the socio-economic development of the region, since it supplies many municipalities (around 1 million people during the tourist season), being used both for supply and for industrial and agricultural use. The aquifer had some pollution and, above all, over-exploitation problems, with the consequent intrusion of sea water and salination a few years ago. Due to periodical drought problems, two desalination plants were built in the coasts of Catalonia, one of them in the TD. The Tordera desalination plant can provide up to 10 hm3/year since 2003; however, due to its high energy consumption is only used as a back-up system. Since current climate models predict that severe droughts may increase in the near future, an enlargement of the desalination plant is forecasted for the coming years.

Following the Catalan Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change 2013–2020, the aquifer depletion is expected to worsen under new climate change conditions; projections estimate an average reduction of groundwater recharge of 20% to 30% by 2070–2100. The effects of climate change are not only related to the concentration of precipitation events, but also to their overall reduction and the increase of temperature, which has the consequent effect on increased evapo-transpiration. The combination of these three climate drivers is expected to cause a reduction in water availability to recharge the aquifer as it has been modeled recently for our group [17].

Considering this context of the study area, it is important to highlight that the Tordera River is one of the few remaining unregulated rivers in Catalonia, offering the opportunity to restore its natural functionality. Therefore, to provide an integrated response to social and ecological issues, and to define adaptation actions and policies aiming to reduce delta’ risks in the future becomes a priority. Following the modern principles of environmental management, this response should be formulated within schemes of Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) and ecosystem-based management (EBM), an integrated framework that must go beyond the classical distinction in sectoral management in freshwater and coastal systems. Consequently, the climate problem targeted and the approach used is fully aligned with European climate policy priorities and the Climate Change Adaptation Strategy.

In short, two main problems are combined in the low Tordera rivers. First, frequent over-exploitation of water aquifers dries up the ecological flow of the river, hence, the associated ecological functions of the river tend to be degraded, which, in turn, explain that the goals of the European Water Framework Directive cannot be attained. Second, due to the critical situation of the flow of the river, the region has become highly vulnerable to periodic extreme weather events, as the Storm Gloria showed. The water system is the most vulnerable to the impact of both observed and future climate change in this region and they have a tremendous influence on all related socio-economic activities. The functionality of the river needs to be managed in a way that is able to absorb periodic episodes of large floods and a management risk system needs to be developed and implemented to reduce social-ecological exposure and vulnerability.

To try to find a solution to all these inter-related issues, the Taula del Delta i de la Baixa Tordera (TDBT) a bottom-up public participatory organization was created on June 2017 by the city councils of the four municipalities that have part of its territory on the TD: Malgrat de Mar, Blanes, Palafolls, and Tordera.

The aim of the TDBT is to recover the social and ecological balances of the TD and to reduce its vulnerability to climate change by means of developing a strategic and integrated plan in a transparent and participatory manner; the objectives listed in Table 1 clearly show the challenge to find a way to reconcile instrumental and intrinsic values competing in the TD.

Table 1.

Main objectives of the Taula del Delta i de la Baixa Tordera (TDBT).

During the first two years of activities, the TDBT developed a stakeholder mapping, a compilation of different information sources, interviews, organized participatory seminars, focus groups, and prepared a document of objectives and recommendations. However, although initial awareness was high and a number of interesting actions followed, the TDBT activities declined before attaining the goals. It is clear that a new input is needed to bring the governance body back to life to promote the identified actions required to attain the s objectives.

2.2. A Geoethical Theoretical Approach

There is a widespread belief that SES challenges may be overcome with technological, economic, and institutional solutions, but most human and nature interactions are more complex than theory wants to acknowledge [18]. Even when it has been proved that technological fixes will not be sufficient to achieve sustainability [19], the technocratic fallacy tries to convince us that technology will provide the needed solutions to all human–nature challenges regardless of the values behind them. However, human–nature relationships are frequently displayed as a conflict, thus, involving ethics and consequently environmental and social justice, or ecological justice [20] related issues. Furthermore, humans are part of nature; they are mutually interlinked in a co-evolution process making it difficult to separate a part of the problem to analyze the whole [18,19] constituting complex coupled human and natural systems [21]. Therefore, it seems that taking a value-based approach may be interesting in approaching SES challenges [14].

In the relationship between humans and nature—here non-human entities—the geosphere is of special interest when referring to the management of natural resources and their governance, because these geo-resources under utilitarian values sustain our current development patterns. The geosphere includes the geological cycle of water, rocks, and minerals and gases, known as the lithosphere, the hydrosphere, and the atmosphere [22]. However, the concept of the geosphere can be understood in a broader sense where geo-dynamic processes and bio-geochemical cycles result in the expression of multiple geosphere manifestations such as rivers, lakes, mountains… as common beings, thus, introducing their intrinsic value. Whilst instrumental value refers to the use value of an object to accomplish something, hence, the utilitarian values of the geo-resources, intrinsic value is the value within an object itself [23], in this case the value of the any component of the geosphere manifestation. Geosphere manifestations, as common beings support communities of life not only in the biophysical sense but also in the spiritual sense [24]. The spiritual bound of human communities with the land as meaningful whole [25] is indeed at the base of historic memories and cultural identity values that overcomes the dichotomy between instrumental and intrinsic values [26].

Values embedded in cultural geographic identities are at the core of the technocratic artifacts by means of which humans relate to the geosphere. Under this approach, the territory, as a conceptual space, is seen not only as a mere political social construct or a “passive” space of power where social actors interact but also as having power in itself the power of the space [27]. The human–geosphere relationship is a continuous social production of space [28], where the physical environment becomes an agent itself [29], shaping humans’ social relationships, which, in turn, affect to different degrees some of the geosphere’s dynamic processes. This social production of space can be understood as a dialogue between intrinsic and instrumental values at the different levels: the day-to-day perceived physical space through landscapes [30], the conceived spaces (or the territorial representation of space), and the land understood as a lived-symbolic space. The land becomes a representational space holding the cultural identity values that bring together the intrinsic and instrumental values, a place where ecological justice [31] is transformed in spatial justice [32]. How cultural identity values evolve and how they are transmitted are key to understanding the complex interrelations between human societies and the physical spaces we inhabit, frequently involving social inequalities and negative impacts and, hence, land use conflicts [33].

The interaction of geosphere manifestations with the human agency, through technocratic artifacts and their enabling technocracies, result from institutional governance frameworks, technical-hardware and software-knowledge and capacities, as well as the dynamics of power between the different social actors, which in turn characterize specific organizational management practices around these artifacts. All these terms define geosphere governability [10], a concept associated to the noosphere [34] that Moiseev [35] interpreted as Earth system governance.

The concept of the noosphere results from the encounter of the Russian geochemist V.I. Vernadsky and the French Jesuit paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin [36] at the beginning of 20th century. For Teilhard de Chardin, the concept of the noosphere was understood as the human evolution towards a theoretical eschatological point [37]. Conversely, the term as coined by Vernadsky emphasizes the development of human consciousness in its relation with the geosphere, highlighting the importance of the values in how humans relate to geosphere. Rather than focusing on processes, the geosphere governability looks at the contingent outcomes of the relationship when utilitarian and intrinsic values are at stake. These outcomes can be defined in term of impact (I) as the alteration of the biogeochemical cycles of the geosphere because anthropic activities and their feedback loop in terms of geodynamic processes on the same human activities; or in terms of socioeconomic vulnerability (V) [11]. Impacts and vulnerabilities, which largely depend on values, are mappable geophysical features, which are suitable to explore potential geo-prospective scenarios [12,29,38].

Geo-prospective scenarios represent the noosphere as a co-evolution production of space between the geosphere and human agency and may be visualized as spaces of practice, “a continuous co-construction of the reality exposing injustices, struggles and resistances and helping us to reconcile a culture of encounter with our symbolic lived spaces” [12]. The visualization of such scenarios is fundamental in achieving cultural change based on hope. Hereby, hope may be understood as “a motivational factor that helps initiate and sustain action toward long-term goals, including flexible management of obstacles that get in the way of goal attainment” [39]. Taking this point of view and expanding the work of Cendrero and Panizza [40] on geomorphology and society, scenarios may be qualitative expressed, highlighting the value dimension underpinning the technocratic artifacts by means of which humans relate to the geosphere and according to the following expression: Noosphere = (Impact + Vulnerability) * values.

2.3. The Geoethical Dilemma as a Geoethical Approach

Taking into consideration the described theoretical framework, a potential way forward to unlock the governance of the SES of the TD is exploring the values within the concept of geosphere governability using a geoethical dilemma. Geoethical dilemmas are defined as the ethical attitude when instrumental and intrinsic values are confronted in the human–geosphere relationship. Geoethical dilemmas help us to discern the meaning values that define the relationship of humans with the geosphere. Geoethical dilemmas unfold as a pedagogy process involving social actors building a values-based ecological dialogue based on solidarity, integrating different views and creating consensus aiming at ecological justice in relation with low impact and vulnerability geosphere governability scenarios.

According to Bellaubi and Arasa [12], a geoethical dilemma is presented as a double-entry matrix representing two possible technocratic alternatives under instrumental or intrinsic values for the two main stakeholders involved in the dilemma. Each alternative is crossed, producing four scenarios. Each scenario can be considered as a noosphere space, as it relates material and spiritual dimensions of the human–geosphere relationship, and may be expressed in terms of geosphere governability [ref added]; meaning it has an impact on the geosphere and, oppositely, implies a derived socioeconomic vulnerability on human activities. Furthermore, each scenario can be quantitatively evaluated regarding the credibility of the social actors involved. Credibility is key in fostering cultural changed [41] by shifting scenarios and it is based on cultural capital [42]. In turn, solidarity as a consciousness for the other [43] may be understood as the created cultural capital within the pedagogic process of a values based ecologic dialogue. In this way, qualitative noosphere scenarios defined in terms of impact and vulnerability may be qualitatively evaluated by a binary scoring system of credibility. The credibility of a stakeholder results from his/her attitude for a value and the associated social cost/gain from the observer. The actor’s attitude scores 1, otherwise it scores 0. Social costs or gains score 1 or 0, and subtracted (if the actor’s attitude is 1) or added (if the actor’s attitude is 0), respectively, to the stakeholder’s attitude according to the perception of the observer over the generated scenario. The rationale for such scoring can be found in Bellaubi and Pahl-Wostl [44], Bellaubi and Lagunov [11], and Bellaubi and Arasa [12].

3. Results

The geoethical dilemma of the TD refers to the urbanization of the coastal landscapes and an increase in recreational harbors, as a result of a mass tourism, and the over-exploitation of ground water, disrupting the morphology and the coastal dynamics and transport of the sediment that results in regression of sand beaches, among others. The involved stakeholders are the Catalan regional and local administrations vs. the tourism sector, whilst the local inhabitants are the “observers”.

The objectives of the geoethical dilemma of the TD are: (1) to understand the current situation of mass tourism, which brings considerable income to the region but has an associated negative environmental impact, especially on the coastal system, considering the values related to the governance, and (2) to open a participatory dialogue under a geo-prospective [29] approach to ask: what are the alternatives to the current tourism model? The geoethical dilemma matrix with the different outcomes’ scenarios and credibilities is shown in Table 2. Scoring of the different scenarios was done on cross-reference of data from different sources, such as a literature review and transect walks in the area, as well as combining the views and opinions of key social actors. Therefore, the results do not aim at any statistical representation but the understanding of attitudes, social practices, and behaviors [45].

Table 2.

Geoethical dilemma matrix in the Tordera Delta.

In scenario 1, both administrations and tourism sector follow attitudes that are penalized (social costs) by the local population. Instead, in scenario 4, their attitudes, although they may not reflect on their values, are welcomed by the local dwellers in terms of social gain. A suggested visualization of the noosphere scenarios 1 and 4 is shown in Figure 2. A geo-prospective approach combined with the geoethical dilemma is of vital importance when conflicting values hold by different stakeholders compete to dialectically “impose” their vision on a territory instead of finding a common dialogical ground, a shared value, that sustain a strategic development visions embedding both intrinsic and utilitarian values in our relationship with the geosphere and that largely depend of our social interactions. This is the case of the TD and the challenges faced by the TDBT.

Figure 2.

Left image: Current Tordera delta aerial view with predominant utilitarian values; right image: proposed ecological restoration introducing intrinsic values to benefit several ecosystem services such as habitat provision, coastal protection, or nutrient regulation. (Pictures, courtesy of Daniel Roca).

4. Discussion

The result of the geoethical dilemma of the TD discussed in the previous section was presented in the CEAB-CSIC Centre, Blanes, at a two-day conference event the 5 and 6 of March, 2020, organized by the Campus of Natural and Cultural Heritage of the University of Girona, CEAB-CSIC and the NGOs ecologist platform SOS Costa Brava. In advance of the conference, a group of scientists prepared and made public the “Manifesto for the Tordera”, which proposed a number of detailed management actions to be put in place to improve river and coastal management. During the conference, attended by over fifty public officials, municipal technicians, researchers, and experts from different fields, it was discussed how geoethics could invigorate the TBDT. For the first time in this context, the contributions of the geoethics perspective were openly discussed, both theoretically and in practice, during a participatory workshop with some of the main local stakeholders that allowed to envisage some possible future scenarios as showed in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3.

Enhancing credibility of scenario 3.

Table 4.

Enhancing credibility of scenario 2.

The values that define our relationship with the geosphere relate significantly to how we relate to others under the principle of solidarity. Bearing solidarity in mind, we can engage in a values-based ecologic dialogue that allows us to commit on shared values to develop a common future in the human–geosphere relationship. This represents another way forward for complex governance problems, overcoming participatory processes that have often become irrelevant technocratic tools of “environmental consumption” without being able to modify the current socio-environmental unsustainable trends [46].

In Table 2, scenario 1 represents the current situation in terms of geosphere governability in the TD, whilst scenario 4 would be the best outcome in relation with impacts and vulnerability. Scenario 4 is also the most credible, and overcomes a possible “ecological tragedy” in the TD. The paradox remains how to shift from scenario 1 to 4 when the latter is the most credible. Since reaching scenario 4 involves a change of stakeholders’ attitudes, it is perhaps more feasible to look for other possible scenarios that avoid the ecological tragedy. Hereby, we suggest politically articulating the dialogue in order to increase the credibility of scenarios 3 and 2, looking at a way to reduce the social costs of administration or tourism sector by posing the following questions:

To improve the credibility of scenario 3: How can “investors’” benefits have a positive effect on improving social services (living conditions) and environmental services (coastal landscapes)? This question may trigger an increase in the credibility of scenario 3 because the locals see the sharing of the benefits of tourism as an act of solidarity (Table 3). To improve the credibility of scenario 2: How can public administration commit to the proposals of the population and environmental groups, not only in urban planning (beyond consultation and empowerment)? In this situation, the solidarity comes from the administration as “an offer” to include the local views on the tourism sector development (Table 4).

However, the dialogue can also be inwardly driven by suggesting, as exposed above, a change in attitudes and exploring the meaning identity values at stake in the dilemma. Undoubtedly, the mass tourism industry is part of the locals’ way of living. Not only has the tourism development created jobs and boosted the coastal municipalities economy, but also from a socio-cultural point of view, visitors and tourists exposed the locals to new ways of living and thinking. In turn, many locals felt their traditions and the local beaches and old calm villages were lost in favor of economic growth. Taking this “inward way” in the dialogue means to question not only the kind of tourism development model itself, but also if mass tourism is necessary and convenient at all. In this context, the strong reduction of tourism during the last year, as a result of Covid-19 policies, can be seen as an invitation to reflect on how tourism may be articulated together with auto-sustainable local economies based on degrowth theories [47] to find an “equilibrium point” on solidarity, which accepts the benefits of tourism under certain premises and conditions acknowledging that a complete preservation of the environment is perhaps not possible yet. A “small, slow and local” spiritual entrepreneurship tourism [48] that respects people and biodiversity, and a proximity tourism that promotes cultural and natural heritage [49] might be appropriate responses. This solution of compromise could be an attempt to overcome the underlying tension of stakeholder attitudes of intrinsic vs. instrumental values and closer to ecological justice as it tries to reconcile both social and environmental issues. In the end, the values that shape the identity of the people with their environment are the overlapping interacting layers producing a living space.

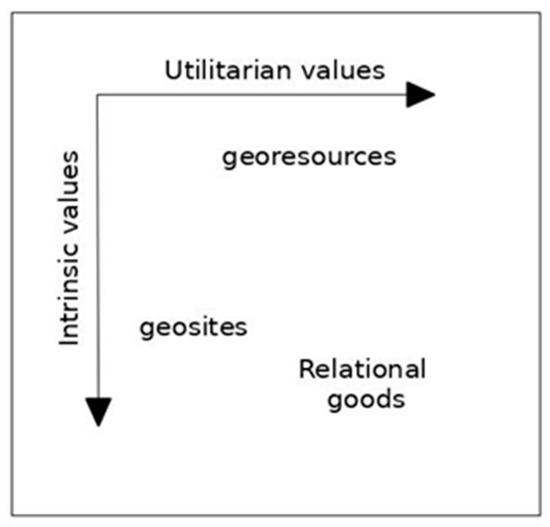

Geoethics appears as an ethic that investigates and reflects on the values that sustain appropriate behaviors and practices, wherever human activities interact with the Earth system [50]. In this sense, geoethics allows a more profound reflection on how to tackle georesources governance starting from their classification. The well-known [51] classification of natural resources when dealing with SES is based on access and rivalry management categories does not capture the complete spectrum of values at stake. Mckelvey georesources classification [52] is an attempt to take into consideration the challenge of the uncertainty of the nature of the resources but largely remain under a utilitarian view. In turn, Alfsen et al. [53] developed a classification integrating the social importance of environmental services provided by georesources, whilst Brilha [54] considers the cultural and immaterial value of geosites under the concept of geoheritage. However, none of these classifications highlight the “geopotential” of the geosphere [55] as fully contributing to the cultural and socio-economic development of a territory [56]. Water, minerals, and soils are more than simple resources to be used or consumed under utilitarian views, as they constitute a complex meshed relations with human interactions through rivers, mountains, lakes, deltas and estuaries; all of them having intrinsic values attached that are frequently ignored. Embedded utilitarian and intrinsic values constitute meaning identity values that overcome the utilitarian–intrinsic dichotomy. A geoethical governance approach allows broadening the existing classification of georesources, considering their constitutive value dimension in the relationship between humans and geosphere by considering them relational goods, immaterial goods that do not decrease with non-consumptive use, but providing well-being instead [57]. Figure 3 displays such an idea.

Figure 3.

An alternative classification considering human–geosphere relationship.

5. Conclusions

We exposed the importance of geoethics as a possible way forward to unblock governance processes focusing on a values approach. This perspective involves a different way of managing geo-resources, such as water, soil, and minerals, not only from a utilitarian view, but also taking into account the interaction between water, soil, and atmospheric cycles, as a whole that generates the geosphere. Thus, our rivers, deltas, mountains, beaches, or lakes sustain human communities, which highlight the intrinsic value of the geosphere in an inseparable relationship that generates cultural identities. We can remember that particular place or that bend in the river where we were fishing in our childhood; that beech where we walked with our partners, or that summit that we climbed in our youth. These particular forests and meadows, these rivers or beaches are permeated with experiences of ourselves and our ancestors, constituting a part of our identities. Those places cannot be only resources, but a living part of our history and us. They were in place when we were born and raised and will eventually see us die and return to the Earth. Geoethics opens a door to consider that there are deeper inward or spiritual meaningful values that link us with the land we inhabit, which is not inert, but alive and dynamic and, for this very reason, never ceases to interact with us.

Geoethical dilemmas may explain why we become stuck in endless debates on what should be done or avoided. Beyond that, however, there is the delicate question of governance: who decides what to do and how decisions are taken, how are rules framed and legitimized? Fair governance involves more transparent and participatory institutions, as well as more truthful, clear, and accessible information for decision making, which refers to ethical or moral principles. Indeed, principles guide us in what we should do, but they do not tell us why. The profoundest reasons must be discovered in ourselves, at the core of our relationship with Nature, which is never independent of our relationship with ourselves and the other fellows.

The global environmental crisis we are immersed in is also a social crisis strongly related to a type of development that fosters unsustainable—destructive—rhythms of exploitation of the natural resources on which we all depend. The same values that inspire the relationship with our human fellows and ourselves define our relationship with the geosphere.

Any significant intervention in the geosphere has effects at different levels and timescales and on other humans. Thereby, actions like starting the desalination plant of the TD to improve aquifer dynamics related to water extraction, the replenishing of sand extracted from adjacent marine bottoms for tourist use as it has been done in the past in the TD beaches [15,16], or the protection of coastal dunes as recently happened in the same area, are all guided by certain values that are very rarely explained. Often an attitude coherent with the shared values involves a certain social cost, a price to be paid. The social cost is the “price” of the responsibility by sharing the burdens when we make responsible decisions, a kind of social and environmental solidarity: the extent to which we are willing to sacrifice our irresponsible consumerist economic model for the sake of the common good, of both present and future generations.

How can we promote this shared responsibility? How can we foster a dialogue of values that helps to identify those of us who agree, to jointly build a social and environmental fair vision of the future better adapted to the natural cycles and rhythms? How do we imagine the landscapes, deltas, beaches, rivers, meadows, or forests of our land for our children and grandchildren, for generations to come? How should we pass on to our young generations the testimony of the wisest and most inspiring values and memories we have received from our ancestors? Beyond the dialectics of winners or losers, a dialogic dialogue may reconcile us to others and to our land as long as we recognize them. It is about our roots, with the conviction that our values are not absolute, but only a part of the truth, which can be enriched by the values of others, and, thus, foster social growth, in order to be able to better respond together to the increasingly complex and difficult environmental challenges we are facing.

Finding the fragile balance between utilitarian and intrinsic values, and those that give meaning to who we are, either as a person, community, or society, usually is a complex challenge. When the ethical dilemma arises, how can we make progress towards environmental and social justice, with a deep attitude of appreciation for what has been bestowed on us? Geoethics invites us to have a humbler and respectful attitude towards the Earth and to life: to look around and to be amazed, to wonder, because everything is a wonder (as stated by the medieval Catalan philosopher Ramon Llull): appreciating everything we have received, with an attitude of reverence and deep gratitude.

Author Contributions

F.B., (Tortosa, 1971). Geologist and Mining Tech, Eng. with more than 24 years providing technical assistance to development organizations and international agencies, NGOs and research institutions from different countries in the Americas, Africa and Asia-Pacific on natural resources management and climate change. PhD in Natural Sciences (Institute for Environmental Systems Research in University of Osnabrück, Germany), former research fellow at South Ural State University (Russia) and studies in theology (Institute for Religion Sciences Barcelona). Current research on geoethics and integrity at Institute for Environmental Research Xabier Gorostiaga SJ, Universidad Iberoamericana Puebla (Mexico). Member of Silene. J.M.M., (Olot, 1955) With over 30 years of experience as environmental consultant in planning, management and evaluation of natural protected areas and environmental strategic planning, mainly in Western Europe. Member of the IUCN World Commission for Protected Areas and of the Specialist Group on Cultural and Spiritual Values of Protected Areas. Working and researching the interface of natural, cultural and spiritual heritage, in both the management and governance dimensions. He is the chairman of Silene Association and leads a postgraduate course on Spiritual Meanings and Values of Nature, at the University of Girona. R.S., (Barcelona, 1957). Socio-ecologist. Senior Scientist of the National Council of Research of Spain. Associate Professor of the Operations, Innovation and Data Sciences Department of ESADE Business School. Cofounder of the Business and the Environment group of the Global Alliance in Management Education (CEMS). He is developing research and applications in the frontier between social and ecological systems, how they work and interact, how to cope with present and emerging, local and global environmental problems and the role, if any, that science and regulations might play in it. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was carried out partially and received funds within the framework of the ECOPLAYA project (CGL2013-49061) of the National Research Plan of Spain in R+D+i. The authors gratefully acknowledge the ISAAC-TorDelta and the REDAPTA projects coordinated by CREAF with the support from the Biodiversity Foundation of the Ministry for Ecological Transition of Spain that contributed to the development and implementation of the called “Taula del Delta i de la Baixa Tordera (TDBT)” for which we also thank many regional stakeholders involved in the process.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Institut d’Estudis Catalans. Tercer Informe Sobre el Canvi Climàtic a Catalunya; Generalitat de Catalunya: Barcelona, Spain, 2016.

- Institut d’Estadística de Catalunya; IDESCAT. Dades Turístiques 2019; Generalitat de Catalonia: Barcelona, Spain, 2019.

- Garcia-Lozano, C.; Pintó, J.; Daunis, I.; Estadella, P. Reprint of Changes in coastal dune systems on the Catalan shoreline (Spain, NW Mediterranean Sea). Comparing dune landscapes between 1890 and 1960 with their current status. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2018, 211, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Lozano, C.; Pintó, J. Current status and future restoration of coastal dune systems on the Catalan shoreline (Spain, NW Mediterranean Sea). J. Coast. Conserv. 2018, 22, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Generalitat de Catalunya, Departament Territori i Sostenibilitat. Avaluació de l’Estat de Conservació dels Hàbitats d’Interès Europeu 2013–2018; Generalitat de Catalunya, Departament Territori i Sostenibilitat: Barcelona, Spain, 2019.

- Sardà, R.; O’Higgins, T.; Cormier, R.; Diedrich, A.; Tintoré, J. A proposed ecosystem-based management system for marine waters: Linking the theory of environmental policy to the practice of environmental Management. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardá, R.; Valls, J.P.; Pintó, J.; Ariza, E.; Lozoya, J.P.; Fraguell, R.; Martí, C.; Rucabado, J.; Ramis, J.; Jimenez, J.A. Towards a new Integrated Beach Management System: The Ecosystem-Based Management System for Beaches. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2015, 118, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Capua, G.; Peppoloni, S. Defining Geoethics. 2019. Available online: http://www.geoethics.org/definition (accessed on 18 April 2020).

- Wesselink, A.; Fritsch, O.; Paavola, J. Earth system governance for transformation towards sustainable deltas: What does research into socio-eco-technological systems tell us? Earth System Gov. 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellaubi, F.; Bustamante, R. Towards a New Paradigm in Water Management: Cochabamba’s Water Agenda from an Ethical Approac. Geosciences 2018, 8, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellaubi, F.; Lagunov, A. Value-Based Approach in Managing the Human-Geosphere Relationship: The Case of Lake Turgoyak (Southern Urals, Russia). Hum. Ecol. 2020, 48, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellaubi, F.; Arasa, A. Geoethics in Groundwater Management: The Geoethical Dilemma in La Galera Aquifer, Spain. In Geoethics: Status and Future Perspectives; Di Capua, G., Ed.; Geological Society of London: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://sp.lyellcollection.org/content/early/2020/09/22/SP508-2020-125 (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Groenfeldt, D.; Schmidt, J.J. Ethics and water governance. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenna, L. Value-Laden Technocratic Management and Environmental Conflicts: The Case of the New York City Watershed Controversy. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2010, 35, 81–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagristà, E.; Sardá, R.; Serra, J. Consecuéncias a Largo Plazo de la Gestión Desintegrada en Zonas Costeras: El Caso del Delta de la Tordera (Cataluña, España). Costas 2019, 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sagristà, E.; Sardá, R. Assessing the Success of Integrated Shoreline Management in the Tordera Delta, Northeastern Spain. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2020, 20, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagristà, E. Aplicación de Herramientas de Gestión por Ecosistema para su Uso en la Gestión Integrada de Zonas Costeras (GIZC): El Caso del Delta de la Tordera y la Playa de S’Abanell. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 2020; 420p. [Google Scholar]

- Bellaubi, F. Exploring the relevance of the spiritual dimension of the Noosphere in Geoethics. In Geo-Societal Narratives. Contextualsing Geosciences; Bohle, M., Marone, E., Eds.; Nature Springer: Cham, Switzerland, in press.

- Daly, H.E. The Economic Growth Debate: What Some Economists Have Learned but Many Have Not. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 1987, 14, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortetmäki, T. Is Broad the New Deep in Environmental Ethics? A Comparison of Broad Ecological Justice and Deep Ecology. Ethics Environ. 2016, 21, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Dietz, T.; Carpenter, S.R.; Folke, C.; Alberti, M.; Redman, C.L.; Schneider, S.H.; Ostrom, E.; Pell, A.N.; Lubchenco, J.; et al. Coupled Human and Natural Systems. AMBIO R. AMBIO A J. Hum. Environ. 2007, 36, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.S., Jr.; Ferrigno, J.G. (Eds.) State of the Earth’s Cryosphere at the Beginning of the 21st Century: Glaciers, Global Snow Cover, Floating Ice, and Permafrost and Periglacial Environments; U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1386–A; U.S. Geological Survey: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- Álvarez, P. (Ed.) Healing a Broken World. In Promotio Iustitiae; No 106; Social Justice and Ecology Secretariat (SJES): Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Verschuuren, B.; Mallarach, J.-M.; Bernbaum, E.; Spoon, J.; Brown, S.; Borde, R.; Brown, J.; Calamia, M.; Mitchell, N.; Infield, M.; et al. Cultural and spiritual significance of nature. Guidance for protected and conserved area governance and management. In Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series No. 32; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2021; XVI + 88p. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, J. Natural meanings and cultural values. Environ. Ethics 2019, 41, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Rolston, H. Environmental Ethics: Duties to and Values in the Natural World; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, M.L. Geopoliticaustral Espacios, Territorios y Poder: Algunas Categorías del Análisis Geopolítico, Punta Arenas. 2006. Available online: https://geopolitica.blogia.com/2006/050903-espacios-territorios-y-poder-algunas-categor-as-del-an-lisis-geopol-tico.php (accessed on 24 October 2020).

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Original Work Published in 1974; Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Voiron, C. L’anticipation du changement en prospective et des changements spatiaux en géoprospective. Espace Géograph. 2012, 41, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.L. Sensing Nature: Unravelling metanarratives of nature and blindness. In Geohumanities and Health, Global Perspectives on Health Geography; Atkinson, S., Hunt, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Chapter 6; pp. 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kortetmäki, T. Justice in and to Nature: An Application of the Broad Framework of Environmental and Ecological Justice. Ph.D. Thesis, The Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences of the University of Jyväskylä, Jyväskylä, Finland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Soja, E.W. Seeking Spatial Justice; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tàbara, J.; Ilhan, A. Culture as trigger for sustainability transition in the water domain: The case of the Spanish water policy and the Ebro river basin. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2008, 8, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernadsky, V.I. The Biosphere and Noosphere. Am. Sci. 1945, 33, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Moiseev, N.N. The Study of the Noosphere—Contemporary Humanism. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 1989, 122, 595–606. [Google Scholar]

- Levit, G.S. Biosphere and the Noosphere Theories of V.I. Vernadsky and P. Teilhard De Chardin: A Methodological Essay. Acad. Int. Hist. Sci. 2000, 50, 160–177. [Google Scholar]

- Casadesús, R. L’évolution comme métaphysique de l’union chez Teilhard de Chardin. Rev. Quest. Sci. 2014, 185, 373–398. [Google Scholar]

- Dodane, C.; Joliveau, T.; Riviere-Honegger, A. Simuler les évolutions de l’utilisation du sol pour anticiper le futur d’un territoire. Cybergeo. European Journal of Geography Systèmes, Modélisation, Géostatistiques. Document, 689. 2014. Available online: http://cybergeo.revues.org/26483 (accessed on 6 November 2020).

- Grund, J.; Brock, A. Why We Should Empty Pandora’s Box to Create a Sustainable Future: Hope, Sustainability and Its Implications for Education. Sustainability 2019, 11, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cendrero, A.; Panizza, M. Geomorphology and Environmental Impact Assessment: An introduction. Suppl. Geogr. Fis. Dinam. Quat. 1999, 3, 167–172. [Google Scholar]

- Knott, D.; Muers, S.; Aldridge, S. Achieving Culture Change: A Policy Framework; Cabinet Office: London, UK, 2008.

- Bourdieu, P.; Passeron, J.C. Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture. Reviewed by T. Broadfoot. Comp. Educ. 1978, 14, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Tischner, J. Selected by Dobrosław Kot from Etyka solidarności [The Ethics of Solidarity], Kraków. 2005. Available online: www.tischner.org.pl/content/images/tischner_4_ethics_years_later.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2019).

- Bellaubi, F.; Pahl-Wost, C.L. Corruption risks, management practices and performance in Water Service Delivery in Kenya and Ghana: An agent-based model. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellaubi, F.; Visscher, J.T. Integrity and corruption risks in Water Service Delivery in Kenya and Ghana. Int. J. Water Gov. 2016, 4, 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Bellaubi, F. Exploring the transmission of values in the Human-Geosphere relationship. TIAS Quarterly No. 02/2019 (July), The Newsletter of the Integrated Assessment Society (TIAS). 2017. Available online: https://www.tias-web.info/publications/tias-quarterly/ (accessed on 28 April 2020).

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F.; Carnicelli, S.; Krolikowski, C.; Wijesinghe, G.; Boluk, K. Degrowing tourism: Rethinking tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1926–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramis Pujol, J.; Suárez Barraza, M.F.; Sardà, R. Socio-ecological spirituality and entrepreneurship: Sa Pedrissa network in Majorca. In Proceedings of the Spirituality and Creativity in Management World Congress, Barcelona, Spain, 23–25 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Llurdes, J.C.; Diaz-Soria, I.; Romagosa, F. Patrimonio minero y turismo de proximidad: Explorando sinergias. El caso de Cardona. Anàlisi Geogràf. 2016, 62, 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Capua, G.; Bobrowsky, P.; Kieffer, S.W.; Palinkas, C. (Eds.) Geoethics: Status and Future Perspectives; Special Publications; Geological Society: London, UK, 2020; p. 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- McKelvey, V.E. Mineral Resource Estimates and Public Policy: Better Methods for Estimating the Magnitude of Potential Mineral Resources Are Needed to Provide the Knowledge That Should Guide the Design of Many Key Public Policies. Am. Sci. 1972, 60, 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Alfsen, K.H.; Bye, T.; Lorentsen, L. Natural Resource Accounting and Analysis. The Norwegian Experience 1978–1986; Sosiale og økonomiske Studier 65; Central Bureau of Statistics of Norway: Oslo, Norway, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Brilha, J. Inventory and Quantitative Assessment of Geosites and Geodiversity Sites: A Review. Geoheritage 2016, 8, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, A.; Lüttig, G.; Snezko, I. Man’s Dependence on the Earth: The Role of the Geosciences in the Environment; Springer: Stuttgart, Germany; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1987; p. 260. [Google Scholar]

- Velazquea Bellaubi, F. Valoración de los Recursos Geológicos del Territorio para Fines de Ordenación Ambiental; Unpublished Report; Colombian Geological Service INEOMINAS: Bogota, Colombia, 1998; Internal (non-published) report.

- Latouche, S.; Harpagès, D. La Hora del Decrecimiento; Octaedro: Barcelona, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).