Abstract

Recently, numerous world heritage sites have burned down or suffered minor damage due to fires. As a result, the Korean government has developed active and passive fire measures in Korean historic villages. Nevertheless, fires have not been prevented, inciting the government to direct its attention toward community-based activities. This paper focuses on human-related fire safety measures and aims to identify the most efficient methods for preventing fires, as well as for minimizing damage caused by them in historic villages. It explores the preventive and response levels of residents and village organizations based on a survey of experts in the field and applies an analytic hierarchy process (AHP) to determine the weighting of the selected attributes. The study proposes that the preventive level is more important than the response level among village residents, and the response level should be prioritized over the preventive level in village organizations in order to prevent and reduce fire risk and damage in Korean historic villages.

1. Introduction

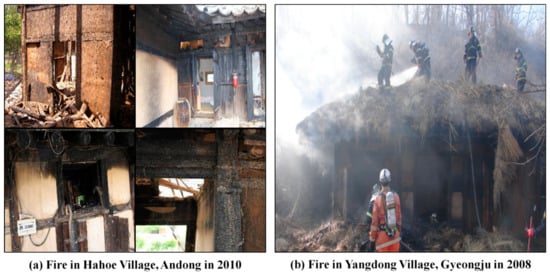

Recently, numerous world cultural heritage sites, including Notre Dame Cathedral (15 April 2019), Shirakawa Village in Japan (4 November 2019), and Shurijo Castle in Japan (31 October 2019), burned down or suffered minor damage due to fire. Hahoe Village in Andong (National Folk Cultural Property No. 122) and Yangdong Village in Gyeongju (National Folk Cultural Property No. 189), Korean historical villages registered as Korean UNESCO sites, also experienced fires. In addition to these villages, Korea contains other historical environments with the same characteristics, often referred to as traditional villages, folk villages, and historical villages.

Village residents have maintained structures and passed down traditions and beliefs to protect these heritage sites over the generations. In Korea, two historic villages have been designated UNESCO World Heritage sites: Hahoe Village in Andong (National Folklore Cultural Heritage No. 122) and Yangdong Village in Gyeongju (National Folklore Cultural Heritage No. 189). Other historic villages of the same nature that still have residents include the Old Village of Hollókő and its surroundings (Hungary), Holašovice Historic Village (Czech Republic), the Historic Villages of Shirakawa-go and Gokayama (Japan), and the Ancient Villages in Southern Anhui—Xidi and Hongcun (China) [1].

Between 2001 and 2017, 16 fire incidents occurred in Korean historic villages. As a result, the Cultural Heritage Administration implemented fire safety and crime prevention systems in 2005 to establish damage prevention facilities with advanced technologies, such as heat and smoke sensor networks [2]. However, despite such efforts, fire risks have not been completely eliminated. Thus, in March of 2017, Korea amended Article 14 of the Cultural Heritage Protection Act and established new clauses for the following areas: Formulating Policy Measures for Prevention of Fire, etc. and Conducting Education and Public Relations Campaigns (Article 14), Development of Fire Response Manuals, etc. (Article 14-2), Installation of Fire Prevention Facilities, etc. (Article 14-3), Designation of Non-smoking Areas (Article 14-4), Request for Cooperation of Related Agencies or Organizations (Article 14-5), and the Building and Managing Database (Article 14-6) [3]. Such efforts by the Korean government suggest that many fires were caused by human error, and that it has begun to direct its attention to human-related measures. Furthermore, the government changed the main paradigms of cultural heritage safety systems from protective measures to human-related proactive measures against fire.

However, thus far, no studies have been conducted to improve effective human-related fire safety measures at historical sites, especially villages. In such cases, what should the focus be to promote community-based preventive and response activities among residents and organizations? This study focuses on community-based activities, categorized by “residents” and “organizations,” and is based upon an expert survey and an analytic hierarchy process (AHP) to clarify the weighting of attributes.

2. Related Works

2.1. Fire Risk in Historic Villages

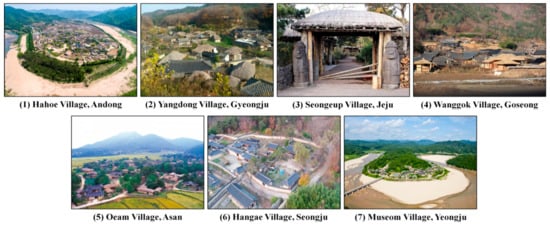

There are seven historic villages in Korea: Hahoe Village, Andong (National Folklore Cultural Heritage No. 122) [4]; Yangdong Village, Gyeongju (National Folklore Cultural Heritage No. 189) [5]; Seongeup Village, Jeju (National Folklore Cultural Heritage No. 188) [6]; Wanggok Village, Goseong (National Folklore Cultural Heritage No. 235) [7]; Oeam Village, Asan (National Folklore Cultural Heritage No. 236) [8]; Hangae Village, Seongju (National Folklore Cultural Heritage No. 255) [9]; and Museom Village, Yeongju (National Folklore Cultural Heritage No. 278) [10]. These historic villages retain more than 500 years of tradition and still exist today; moreover, most have superior natural locations and are surrounded by mountains and bodies of water (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Seven historic villages in Korea.

Most Korean historic villages were constructed from materials readily available from the surrounding natural environment, such as trees, mud, stone, and straw, and are highly prone to damage by storms, floods, termites, and fires [11]. Historic villages are located far from the center of the region. Table 1 and Figure 2 show the cases of fire in Korean historical villages that occurred between 2001 and 2017 [12].

Table 1.

Cases of fire in Korean historic villages, 2001–2017.

Figure 2.

Cases of fire in Korean historic villages.

Most fires are caused by misuse of fire by residents living in the area, indicating the need for countermeasures.

According to the historical disaster statistics from 2001–2017 for cultural heritage sites, 445 total disasters occurred. Among them, wind and flood damage accounted for 44.5% (198 incidents), while fire damage, mainly caused by electrical fires, misfires, arson, and forest fires, accounted for 16.9% (75 incidents) [11]. As a countermeasure after an arson incident in Sungnyemun in Korea, the Cultural Heritage Administration implemented security alarm systems, fire detection and alarm systems, fire extinguishing systems (e.g., fire hydrants), and 24-h preventive monitoring systems at 150 significant cultural heritage sites, 170 historic sites, and 155 important folk material sites.

Characteristic buildings in historic villages include wooden structures, thatched roofs, tile roofs, traditional tile roofs, and slate roofs. Oeam Folk Village consists of 69 houses, 19 of which were built after 2000. Most of the residential buildings are wooden, and a total of 40 houses have thatched roofs. Most of the tile-roofed houses have attached buildings with a thatched roof, and approximately 54.2% of the total buildings (177 houses, 81 tile-roofed buildings/96 thatched houses) have thatched roofs [13]. Of the 159 houses in Yangdong Village, there are 44 thatched houses, 39 traditional tile-roofed houses, 22 western-style roofed houses, 18 slate-roofed houses, and 12 thatched houses with tile roofs.

A research study to predict fire behaviors in historical village buildings and structures using a database on the combustion of rice straw and silver grass indicated that if a thatched roof house were to combust completely, then thatched roof houses within a 5.68 m radius of the burnt house are in danger of fire spread [11]. As confirmed, Korean historic villages are vulnerable to fire, both due to the nature of the building materials and the negligence of residents.

2.2. Fire Safety Measures in Historic Villages

For the fire safety design of a new building, it is necessary to plan, verify, and actualize passive and active measures, and human-related measures based on the location, structure, space, number of occupants, and fire behavior. The building owner and architect play important roles in fire safety design and in clarifying fire safety goals [14]. For this study, the preventive and response levels of passive, active, and human-related measures in buildings are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Passive, active, and human-related fire safety measures in buildings.

The two major measures for fire safety reduction are passive and active. Active measures include early warning and evacuation, which are based on the judgement and action of village residents’ activities. Therefore, human-related measures play the most vital role in immediate fire safety action.

Passive fire safety measures, such as firewalls, fire barrier walls, smoke control, fire partitions, fire retardant paint (column, finishing material), and semi-combustible finishing materials, are included in the architectural planning stage of buildings. Active fire safety measures comprise mechanical, electrical, and/or plumbing facilities that are installed separately in the building and include alarms and communication elements, heat detectors, smoke detectors, fire extinguishing equipment, hose systems, automatic sprinkler equipment, mobile fire extinguishing equipment, and/or fire extinguishers [15]. Certain active measures depend on human judgement and activity, such as using fire hydrants, reducing potential sources of ignition, and executing evacuation plans [16]. In order to achieve sustainable historic villages, understanding community-based activities is essential.

The preventive level of passive measures includes establishing fire precautions such as firewalls, fire doors, and flame-retardant paint, increasing fire resistance, setting fire zones, and exercising caution with fire equipment during repair and improvement work. The response level consists of a comprehensive fire response plan that establishes a list of possessions in the floor plan and heat and smoke control measures.

The preventive level of active measures includes actions taken before the outbreak of a fire and various sensors, lightning protection systems, automatic fire alarm systems, electrical equipment, emergency lighting, exit signs, and various monitoring equipment. The response level after the outbreak of a fire includes facilities such as outdoor fire hydrants, sprinklers, hose reels, fire extinguishers, and mechanical smoke dampers.

The preventive level of human-related measures includes conducting training simulations with residents and organizations regarding their roles in the event of a fire, using firefighting equipment, recognizing important locations, and organizing fire prevention activities. The response level of human-related measures involves the ability to adjust well to an emergency situation and is obtained through training. Examples include fire escape and evacuation activities, involving fire-fighting professionals with occupants, and supporting people with special needs.

Unlike the summary of fire safety measures present in buildings listed in Table 2, historic buildings do not have firewalls, fire doors, or fire-resistant structures. To reduce their vulnerability to fire, since 2005 the Cultural Heritage Administration in Korea has installed fire and crime prevention and protection systems (Figure 3). In addition, fire extinguishers have been installed in historic villages [Figure 3a]. They were provided in historic villages in Korea. Figure 3b shows a streetlight located in Hangae Village, Seongju, outfitted with a flame detector and CCTV to detect sparks and contact nearby fire stations and to monitor outsiders. Figure 3c shows an outdoor fire hydrant, installed in all historical villages and equipped with reel hoses to facilitate use by village residents to extinguish fires before the fire brigade arrives. Figure 3d shows a flame detector, which is usually installed in houses to detect flames and inform the fire station.

Figure 3.

Active fire safety measures in historic villages, Korea.

2.3. Related Studies

The analytic hierarchy process (AHP) used in this study is a decision-making methodology that was developed to create a hierarchy and improve inefficiency in decision-making in cases where the goal of the decision-making or the evaluation standards were diverse or complex. The process using AHP is composed of five steps: (1) hierarchy of the decision problem, (2) pairwise comparison of decision elements, (3) estimation of relative weights, (4) logical consistency, and (5) aggregation of relative weights. These processes make it possible to determine priorities effectively. To increase the reliability of the AHP analysis, it was decided that if the consistency index (CI) is less than 0.1, then it is an acceptable range [17].

Lee proposed that, in analyzing fire risk factors in historical buildings, human-based measures were the most important fire risk factor, followed by historic building construction materials, fire safety systems, and the surrounding natural environment [16]. Cho and Suh categorized risks and their reductions, threats, and current vulnerabilities, and the mitigation and prevention of disaster, and developed 16 preliminary evaluation points to establish an efficient and systematic damage and safety management system for cultural heritage sites [18]. Consequently, human resources for prevention and preventive management were identified as the two areas with the highest weighted grades. The AHP analysis method was used in both of these studies, and is commonly used in studies on fire hazard evaluation and effective management of cultural heritage sites. While conducting evaluation studies regarding the fire risks of historical buildings, the AHP analysis method was first used in a study on the Historic Fire Risk Index (HFRI) [19]. Kwon and Lee [20] applied the AHP analysis method to evaluate the fire risks of crowded wooden building cultural assets, and initial findings indicated that cultural heritage significance (0.625) was more important than the fire risk (0.375), while for sub-items, historical representation and symbolism (0.347) was the highest in cultural heritage risk, while fire load evaluation (0.437) was the highest in fire risk.

A study on Cultural Heritage Disaster Management [21] also used the AHP analysis method for fire risk evaluation of wooden heritage properties. Initial findings indicated an order of management system (0.452), prevention system (0.237), preparatory system (0.159), and response system (0.152).

Song et al. [22] applied the AHP analysis method to prioritizing repair targets in structural cultural heritage sites. The initial findings indicated an order of cultural heritage damage (0.488), relative importance of cultural heritage (0.305), and management policies of cultural heritage (0.207). In the cultural heritage field, Lee [16] and Cho, and Suh [18] revealed the importance of human-led management and measures related to cultural heritage sites. However, no study has been conducted on human-related measures in historic villages, such as determining which measures are more instrumental in preventive and response levels between residents and village organizations.

3. Methods

In this study, the terms preventive level and response level are defined and presented in Table 3, and introduced as a means to improve the fire safety performance of historical villages.

Table 3.

Definition of preventive and response levels.

3.1. Configuration of Items

3.1.1. Criteria

The main criteria for preventive and response levels of residents and village organizations were organized as shown in Table 4. Currently, village organizations comprise village preservation societies, operating committees, conservation consulting committees, and traditional folk advisory committees. Thus, criteria regarding preventive and responsive human-related measures were established to focus on residents and village organizations.

Table 4.

Classification of criteria.

3.1.2. Sub-Criteria

The residents’ preventive level encompasses their experience in disaster prevention training, and the degree of the implementation of fire measures and of awareness of firefighting facilities. The residents’ response level includes their adherence to fire prevention practices and to fire prevention education activities.

Village organizations’ response level consists of the village fire brigade’s capability, the age of the village fire brigade, actual capability of organization members, and the village fire brigade captain’s awareness of fire prevention. Village organizations’ preventive level encompasses environmental factors such as the capability of the assembly hall, actual usage rate of the assembly hall, degree of participation of residents, and the ratio of long-term residents.

3.1.3. Sub-Attributes

For the human-related measures in historic villages, sub-attributes for the preventive and response levels of the residents and village organizations were structured as shown in Table 5. Four criteria, 13 sub-criteria, and 22 sub-attributes comprise the preventive and response levels of the residents and village organizations.

Table 5.

Construction of sub-attributes for human-related measures in the constructed AHP hierarchy.

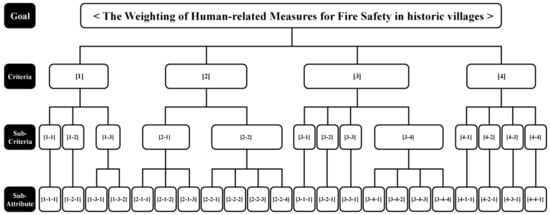

3.1.4. A Hierarchy for Priorities of Human-Related Measures for Fire Safety

Based on the above items, the following hierarchy was constructed (Figure 4). This is the first and most important task in the decision-making process using AHP. The next steps are pairwise comparisons, weight estimations, logical consistency, and weight summary.

Figure 4.

Hierarchical structure of human-related fire safety measures in historic villages.

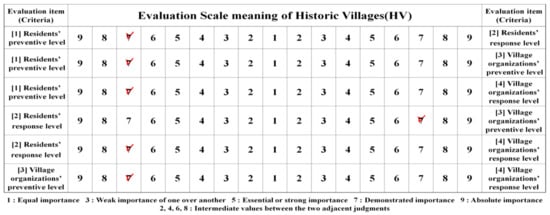

3.2. Sample Design

In the design of a pairwise comparison matrix, the relative weight of each element was derived using a 9-point scale (Figure 5). The red symbols marked in the figure were checked by the questioner. The sample size was a prerequisite for securing reliability, and in the AHP analysis with experts as the primary target, was generally approximately 5–20 people. Nine experts in the fields of cultural heritage, architecture, disaster prevention, etc., were contacted either via email or by a direct visit, with a resulting response rate of 100%. The goal of this analysis was to determine the relative importance between judgment criteria, thus, a distributive mode was utilized. The items constituting the model were evaluated 1:1 to the aforementioned criteria, a pairwise comparison matrix was configured, and the relative weights were derived by calculating the eigenvalues of the matrix.

Figure 5.

A survey of pairwise comparison of evaluation.

Evaluation results regarding the selection criteria of decision participants through primary pairwise comparison indicated low logical consistencies in some criteria. In areas with low logical consistency, feedback on the results was used to review each area of inconsistency to improve the results to within 0.1, which is the threshold of the consistency ratio. The percentage of inconsistency before logical consistency checking was between 0.000 and 0.422. Accordingly, the results were fed back and the illogical aspects were reviewed one by one with the process of modification or supplementation. As a result, the logical consistency of the participants was improved, with an inconsistency ratio from 0.000 to 0.099 below 0.1.

4. Results

According to the expert opinions on the four criteria shown in Table 6, preventive level of the residents (50.9%) scored the highest, followed by response level of village organizations (20.6%), response level of the residents (18.9%), and preventive level of village organizations (9.6%). The weighting of the sub-criteria for preventive level of the residents was determined as follows: experience in disaster prevention training was the highest (72.4%), followed by degree of implementation of fire measures (15.8%), and degree of awareness of firefighting facilities (11.8%). The weighting of the sub-criteria for response level of village organizations was determined as follows: adherence to fire protection practices was the highest (78.1%), followed by adherence to fire protection education activities (21.9%).

Table 6.

Ranking of human-related measures criteria, sub-criteria, and sub-attributes for fire safety in historic villages.

For the response level of village organizations, actual capability of organization members was the highest (40.5%), followed by village fire brigade capability (23.2%), village fire brigade captain’s awareness on fire protection (23.2%), and age of the village fire brigade (13.1%). For the preventive level of the village organizations, the degree of participation was the highest (36.3%), followed by actual usage rate of an assembly hall (26.9%), capability of an assembly hall (22.6%), and rate of long-term residence (14.1%).

Among the 22 sub-attributes, using firefighting facilities had the highest importance (16.8%), followed by the percentage of households participating in training (13.3%), implementation of fire measures (12.8%), installing firefighting facilities (7.9%), ratio of active members to all members (5.9%), participation rate of fire protection practices (5.5%), and identification of hazardous location identification (5.1%). The weighting of these seven sub-attributes all exceeded 5%.

Meanwhile, sub-attributes, such as the age of the village fire brigade (0.8%), the term of a captain (1.0%), and the presence or absence of fire evacuation maps (1.0%), were found to be relatively less important, with weights below 1.0%.

All four criteria ranked as the most important derived from the preventive level of the residents. The ratio of active members to all members was ranked 5th, the participation rate of fire protection practices was 6th, and the identification of hazardous locations was 7th.

5. Conclusions

All over the world, concern has increased for preserving traditional built heritage from destruction by fire. The Korean government has taken great strides in developing fire safety systems, including active and passive fire measures. Nevertheless, fires in historic villages continuously occur. Consequently, the government has focused its attention on community-based activities. However, until now, no research has explored efficient methods for preventing fires in historic villages. This paper intended to fill this gap and has:

- focused on human-related measures in historic villages for prevention and response levels of fire measures.

- defined the preventive and response levels of residents and village organizations.

- evaluated a method to be used to determine the weighting of the selected attributes.

- determined the priority criteria, sub-criteria, and sub-attributes when planning fire safety measures in historic villages.

This study proposed that the preventive level is more important than the response level in residents, and the response level is prioritized over the preventive level in organizations. In general, different types of organizations exist in historic villages. Due to advances in fire safety in such villages, government or safety designers are ranked the highest in the preventive level of individual residents, as well as in the response level of village organizations. Among the 22 sub-attributes, those ranked the highest in importance fell in the preventive level of the residents. For example, using firefighting facilities had the highest importance (16.8%), followed by the percentage of households participating in training (13.3%), implementation of fire measures (12.8%), installing firefighting facilities (7.9%). In general, if the preventive level of an individual improves, the preventive level of the village will inherently improve as well.

We conclude that education that focuses on the preventive level rather than the response level for residents, as well as the development of actual capabilities in the response level, such as fire protection action for village organizations, is essential in preventing and reducing fire risk and damage.

One important limitation of this study was, however, a lack of research conducted on living residents and existing organizations of historic villages. In addition, the availability of this method for assessing fire risk in historic villages—specifically, to rank various elements for effective fire safety design—should be improved. Clearly, further work is needed to understand the components of community-based activities necessary for fire safety in historic villages.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-H.L.; Methodology, J.-H.L., J.-H.C.; Investigation, J.-H.L., W.-Y.C.; Data curation, J.-H.L., W.-Y.C.; Validation W.-Y.C.; Writing–original draft, J.-H.L.; Writing—review and editing, J.-H.C.; Supervision J.-H.C.; Funding acquisition, J.-H.L., J.-H.C.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by research funding for R&D projects by the National Fire Agency (NFA) [No. 2018-NFA002-005-01030000-2020] and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant (No. NRF-2018R1A2B3005951 and No.2019R1A2C1004548), which was funded by the Korean government (MSIT).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Home Page. World Heritage List. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/ (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- Kim, D.H.; Lee, J.H.; Yi, M.S. Development of safety equipment database for effective management in wooden cultural heritage. J. Fire Sci. Eng. 2016, 30, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Korea Legislation Research Institute, Korea Law Translation Center Home Page. Cultural Heritage Protection Act, Article 14 of Chapter III (Creating Foundation for Protection of Cultural Heritage). Available online: https://elaw.klri.re.kr/eng_service/lawView.do?hseq=33988&lang=ENG (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- Available online: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hahoe_Folk_Village (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Available online: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yangdong_Folk_Village (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Available online: https://SeongeupHistoricVillage,Jeju-HeritageSearch|CulturalHeritageAdministration(cha.go.kr) (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Available online: https://WanggokVillage,Goseong-HeritageSearch|CulturalHeritageAdministration(cha.go.kr) (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Available online: https://OeamVillage,Asan-HeritageSearch|CulturalHeritageAdministration(cha.go.kr) (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Available online: https://HangaeVillage,Seongju-HeritageSearch|CulturalHeritageAdministration(cha.go.kr) (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Available online: https://MuseomVillage,Yeongju-HeritageSearch|CulturalHeritageAdministration(cha.go.kr) (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Kim, D.H.; Lee, J.H. An Experimental Analysis of Thatched-Roof Materials to Assess Fire Risk in Historical Villages. J. Korean Soc. Hazard Mitig. 2015, 15, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, D.H.; Yi, M.S. A study on safety culture for enhancing local resilience in historic villages. In Proceedings of the Korean Society of Hazard Mitigation, Seoul, Korea, 16–17 February 2017; p. 145. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.S.; Lee, W.K.; Oh, K.H.; Shin, K.Y.; Kwon, H.S. A Study on the Basic Ideas for Fire Fighting Prevention System in Traditional Folk Village: Focused on Oeam Folk Village in Asan. J. Archit. Hist. 2010, 19, 71–90. [Google Scholar]

- Architectural Institute of Japan. Principles of Fire Safety Design; Architectural Institute of Japan: Tokyo, Japan, 2013; p. 1. ISBN 978-4-8189-2709-4. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, J. Simplified Design for Building Fire Safety; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1993; p. 215. ISBN 0-471-57236-5. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.H. A Study on the Weighting of Fire Safety Attributes for Fire Risk Assessment in Historic Buildings: Focused on NakSansa. J. Korean Soc. Saf. 2012, 27, 189–196. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, T.L.; Vargas, L.G. Uncertainty and rank order in the analytic hierarchy process. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1987, 32, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.S.; Suh, H.J. AHP Analysis techniques for the weighted evaluation of Cultural Heritage Disaster Safety Management Systems. J. Korean Soc. Hazard Mitig. 2018, 18, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, J.M. Fire-Risk Indexing: A Systemic Approach to Building-code “Equivalency” for Historic Buildings. J. Preserv. Technol. 2003, 34, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, H.S.; Lee, J.S. A study on the fire fighting general index for fire fighting of crowded wooden building cultural asset. J. Archit. Hist. 2012, 21, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.D. Disaster Management of Cultural Assets in Korea: Feed-forward Control Strategy for the Wooden Cultural Assets Buildings. Ph.D Thesis, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju, Korea, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Song, K.J.; Kim, C.J.; Kang, K.I. Development of the Decision Support Model for Prioritizing the Cultural Properties Repair. J. Archit. Inst. Korea Struct. Constr. 2007, 23, 211–218. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).