Abstract

Last-mile logistics is both a source and cause of problems in urban areas, especially problems related to traffic congestion, unsustainable delivery modes, and limited parking availability. In this context, multiple sustainable logistics solutions have been proposed. We focus on micro-depots (MDs), which can function as a consolidation center and a collection-and-delivery point for business-to-consumer (B2C) small parcels. This paper presents a new research idea that extends the existing MD solution by introducing the concept of a shared MD network with parcel lockers. Such networks enable multiple logistics service providers (LSPs) and/or business partners to use an MD while minimizing their individual costs and optimizing the use of urban space. We present case studies of such shared MD networks operating in the cities of Helsinki and Helmond. We provide a framework for auxiliary businesses that can exploit the existing MD structure to offer services to the surrounding population. Finally, we define metrics for evaluating the success of shared MD networks while considering social, environmental and economic objectives. The case studies highlight the complexity of implementing such a solution; it requires stakeholders’ involvement and collaboration. In particular, deciding on the location for a shared MD network is a critical phase, since local authorities have their own regulations, and residents’ preferences are usually different than LSPs’ ones. Nevertheless, if these challenges are overcome, this sustainable last-mile logistics solution has a promising future.

1. Introduction

Last-mile logistics focuses on delivering parcels to the end-customers’ preferred location instead of purchasing the goods at disparate physical stores, increasing the number of freight movements, which is even more aggravating when considering that each parcel is often small [1]. The last mile, furthermore, is a significant component of the parcel delivery cost, which usually comprises close to 50% of the total cost [2], and is often characterized as the most polluting and inefficient part of the supply chain [3]. Thus, minimizing the environmental and economic impacts of last-mile delivery in congested urban areas while satisfying the final customers is an important logistic challenge involving many stakeholders with different and sometimes opposing needs and constraints.

One of the ways to circumvent these challenges is to reduce freight vehicle miles traveled by establishing urban consolidation centers (UCCs) which enable the collaboration between shippers, carriers and retailers with the goal of consolidating deliveries. Typically, this consolidation tends to decrease the number of required delivery trips between the distribution center and the final delivery destination [4]. The UCCs were first planned and implemented in a number of European cities, particularly in France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and the UK, and in Japan, mostly over the two past decades. Their success and economic self-sustainability depend on several factors such as the level of involvement and cooperation of the different last-mile actors (shippers, carriers and retailers) during the early stages of the project, the financial support of public institutions, the local regulatory restrictions and the location of the UCCs and the quantity of services offered [5,6,7].

An additional last-mile logistics solution is the development of collection-and-delivery points (CDP) and automated lockers in urban areas, thereby offering more flexible delivery options for the customers. This alternative to home delivery can also be viewed as a commercial effort to diversify the deliveries options to meet the customer preferences. For example, in France, more than 20% of goods are delivered through a CDP [8]. Moreover, mostly due to the well-known frequency of failed first-time home delivery attempts, the CDP delivery option reduces the travel and environmental costs compared with the later option [9].

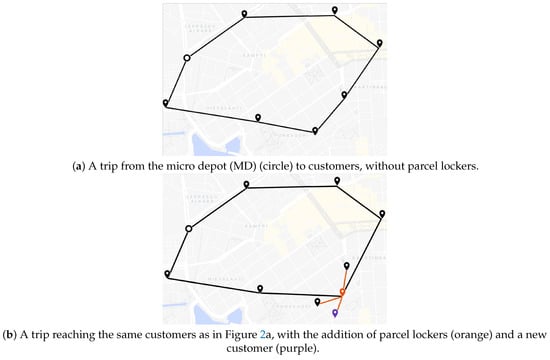

A micro-depot (MD) is a logistics facility usually located inside or close by an urban area, in which a logistics service provider (LSP) can load or unload, sort, store, and deliver parcels from it to the end-receiver. The use of MDs generates two outcomes: consolidation of deliveries (which is why MDs are also known as micro-consolidation centers [10,11]) and employment of vehicles in the last-mile delivery that are less harmful to the environment [12], such as cargo bikes. An MD can also be a CDP, in the sense that parcel lockers can be installed and customers can pick up or deliver their parcels from/to there. MDs have been in use since the early 2010s, usually by large well-established LSPs [12], but typically as a facility for a single company use [10,12,13,14], such as Amazon and UPS lockers. A shared MD is an MD whose facility is used by many LSPs, who can operate independently or have a single white-label company operating on behalf of all of them. As mentioned above, UCCs have to cope with many challenges in order to be financially viable; thus increasing the number of LSPs having access to a given MD and consolidating its use should be alleviate many of the financial challenges.

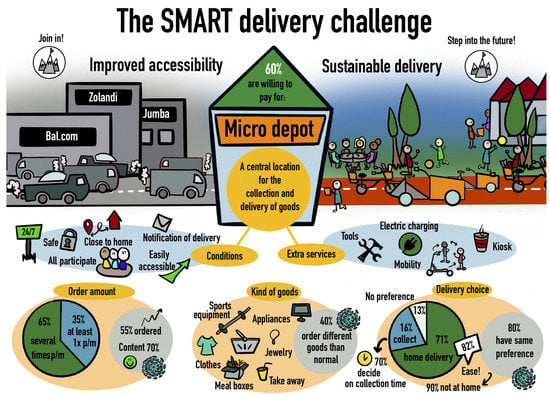

We introduce, in this paper, the–so far unique–concept of a shared MD network for last-mile logistics with parcel lockers and auxiliary business models. Our research idea paper’s intention is to define a new last-mile logistics solution for future academic research and real case studies in multiple cities. The shared component we propose, thus, is an innovation that can yield cost reduction, improved customer service, and reduced congestion, noise and air pollution. The shared MD concept was tested in the real world as part of the Shared Micro-depot for Urban pickup and Delivery (S.M.U.D.) project. This project consisted of a consortium of cities, research institutes and an architectural design firm whose goal was to provide an attractive solution to business-to-consumer (B2C) small parcel last-mile delivery that benefits cities, residents, and businesses. Over the course of a year, the cities of Helsinki (FI) and Helmond (NL) served as testbeds for this new logistics concept. In Helsinki, one strategically located MD was shared by five business partners and served as both a transshipment point and CDP. In contrast, in Helmond, the initial focus was mapping customers’ and residents’ needs, and aligning them with the local authority’s vision of a green and smart city, and with the business partners’ operational processes.

The main takeaways from our case studies are that support from local authorities is vital from the beginning of planning. The location of a shared MD is extremely important, both for business partners and city residents, and for customers’ acceptance; sharing a facility (and a business) is only possible when there is transparency and trust among two business partners; and for the sharing to work, moreover, it is our experience that it is better for a third-party entity to oversee the shared MD’s operation, so that each LSP can handle its business without the concerns of the entire network.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents a literature review; Section 3 discusses the case studies from Helsinki and Helmond, as well as providing alternative implementations for a shared MD; Section 4 describes how one can assess the success of implementing a shared MD network; finally, Section 5 concludes our work.

2. Literature Review

During the last decade, with the rapid growth of online shopping, which has increased the congestion and emissions in cities, the number of academic studies in the area of last-mile logistics has significantly increased [15,16,17], where sustainability is the key objective. In particular, multiple-echelon distribution strategy is a modern trend where the delivery of parcels from the initial distribution center to the final customer is done through intermediate and typically small depots in order to minimize the total transportation cost of the vehicles involved in the deliver process [18,19]. Special attention is given to the complex urban parcel delivery system, because of obvious environmental and social issues [20]; the emergence of sustainable mobility is fueling an increase in the number of research and projects of last-mile delivery in cities.

Numerous mobile depot [21], micro-depot [11,22] and urban consolidation center (UCC) [4,18,23,24,25,26,27] solutions have been implemented in several cities and reviewed in the literature. The work [14] is the first to present the use of a trailer as a mobile depot in an urban area. In their pilot studies in Brussels, in the morning, this mobile depot parks in a parking location in the city. Then, electric cargo bikes pick up parcels from the mobile depot and convey them to their final destination. This pilot study was conducted in cooperation with an international LSP. The authors [14] discuss the sustainable, social and economic effects of this new concept on the different involved stakeholders, using a multi-actor multi-criteria analysis (MAMCA). The survey’s results show that the mobile depot is a profitable solution for all stakeholders (residents, city, LSPs and customers), except for the LSP itself, because of excessive required costs. The analysis also reveals that internalizing external costs, increasing the capacity use of the depot and the drop density would be more economically viable for the LSP. In particular, this work demonstrates the need to share costs with other LSPs, as, among other things, we propose in the present study.

The mobile depot presented in [28] circles the city and only parks when loading and unloading. Thus, this configuration requires less urban space than the solution of [14] and decreases the economic cost of the LSP. Nevertheless, the congestion and the pollution could be reduced further because the suggested mobile depot is neither electric or small. Moreover, these solutions do not propose the installation of parcel lockers, which enable customers to pick up their own deliveries from the depot and reduce the last-mile delivery. Indeed, the inclusion of different delivery modes, such as green vehicles, bikes and parcel lockers, enables this last-mile logistics solution to be more sustainable [29].

Ref. [30] addresses a MAMCA framework to evaluate the social, environmental and economic impacts of freight consolidation policies in an urban environment that consider the objectives and the constraints of all stakeholders involved in the solution. Ref. [31] conduct a simulation study on the UCCs in the city of Copenhagen. They test and analyse several schemes, where a scheme is defined by its combination of administration measures and costs settings.

Multiple articles highlight the importance of the UCCs and MDs’ location; several mathematical and quantitative models support this decision problem by considering sustainable constraints [32,33,34,35].

In urban environments, available space is a serious constraint, because in most cities, it is rare and has a prohibitive cost. Thus, MDs have been implemented in many cities, such as Manhattan [22] and London [10], in order to optimize last-mile logistics. Moreover, the literature proposes and analyzes the introduction of parcel lockers in last-mile logistics [36,37,38]; final customers can collect their deliveries whenever it is convenient for them, and it may avoid the problems involved with home deliveries, while reducing the environment impact.

The present paper differs from most of the concepts of last-mile logistics developed in the literature so far, by proposing a micro UCC in an urban environment that is shared by multiple LSPs—in other words, a shared MD network. Indeed, in the logistic solutions proposed above, the costs of the depot are supported by one LSP, which have a negative effect on the economic viability of the projects. We propose a shared MD, which can be utilized and financially supported by several LSPs. The solution proposed in this paper is related to the mathematical model formulated in [39]; indeed, the authors define a mixed integer programming problem for solving the urban last-mile delivery issue, by assuming that urban depots can be jointly used by multiple LSPs. They show that optimal usage of shared spaces enhanced by multiple delivery options in cities helps to decrease the operational, economic and environmental costs with respect to the single-echelon policy, while focusing on customers’ delivery option preferences. Their methodology is theoretical, whereas our approach is empirical, since real case studies support our proposed solution. Moreover, the shared MD network concept that we propose here is flexible enough to integrate parcel lockers as CDPs and auxiliary business models, which may be economically profitable for the LSPs and sociably profitable for residents.

5. Conclusions

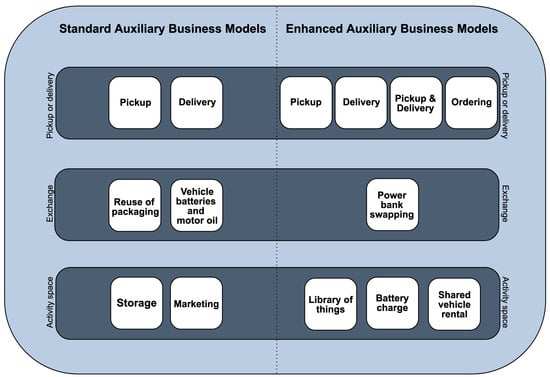

In this paper, we introduced the concept of a shared MD network with parcel lockers and auxiliary business models for B2C small parcel last-mile deliveries. Our contribution to cities and business partners is to showcase studies of a shared MD network’s implementation, to provide a framework for possible auxiliary businesses that can be tailored to each location, and to supply a way of measuring the implementation success. Shared MDs generate advantages for cities and their residents, customers, and business partners.

From the case studies presented, we conclude that implementing them is not an easy task; support, not necessarily financial, from local authorities dictates whether this new model of thinking about city logistics will be sustainable in the long run. The success of a shared MD close to residents also depends heavily on their acceptance of having a logistics facility in the middle of the city, and using the auxiliary services that it provides. Finding the right business partnerships, moreover, is a crucial step in ensuring that sharing an MD unfolds smoothly. The shared MD’s facility, also, when operated by a third party, allows LSPs to handle their business more efficiently.

With the proposed framework for possible auxiliary businesses that would work in the shared MD network, this paper intended to help municipalities and their business partners to understand the opportunities inherent in sharing an MD: the added value for the community while improving current business operations. The idea of auxiliary businesses for the shared MD network is to make the most with limited resources and, by doing so, increase the value of the urban space used and provide residents with services that, without their consolidation at one location, would be harder to receive. Moreover, companies can think of the shared MD network as an innovation hub, where they can try new models with support from the local authority. The main construct that underpins the entire concept of auxiliary businesses at an MD is the shared component. Besides possibly resulting in reduced personnel and real estate costs, among others, the level of cooperation among business partners is, again, the critical aspect that may prove that these models are good for both the end customer and for the companies themselves.

Our assessment framework lays out valuable metrics to evaluate the establishment of a shared MD network. The three pillars (environmental, economic, and social) are important to make sure the network is sustainable in the long run. With consolidation of deliveries, fewer delivery trips would be necessary, reducing fuel consumption, GHG emissions, and traffic noise. To have public acceptance, all stakeholders need to be involved, beginning in the planning phase. Adopting pilot tests is also a good way of shaping both the service provided and residents’ mindset. The costs of the network should not be neglected, and the local authority usually has to come up with the initial incentive, financially and/or through regulation and policies.

This paper developed a new idea for last-mile logistics to be considered in future academic research and tested in urban environments; as next steps, researchers could compare the implementation of a shared MD network to the current state of business. Different delivery policies may be considered. In addition, the field needs a deeper investigation of the impacts of having a white-label company operating the MD instead of each LSP working independently. Another extension of the shared MD network that may be analyzed in the future is the use of a UCC by multiple LSPs, which consolidates deliveries even more, and only one company delivering to all MDs. Future work, also, can investigate the network from the reverse perspective and analyze the impact caused on the first mile when different shared MD network designs are in place. There are still open questions regarding how to successfully share not only facilities, but also the business. Helmond’s case study points to a direction of a possible solution; yet, other alternatives to eliminating mistrust among business partners and solving liability issues may need to be developed further.

Author Contributions

This research was carried out by several groups in several countries. Each carried out their assigned part and wrote up their part. In addition, the Technion team combined these contributions into this meaningful article. Conceptualization, Y.T.H., K.D., P.G., P.P. (Pete Pättiniemi) and S.v.U.; Formal analysis, L.N.R., Y.T.H., E.D. and P.G.; Funding acquisition, K.D.; Investigation, L.N.R., E.D. and P.G.; Project administration, K.D.; Resources, K.D., P.P. (Pete Pättiniemi), P.P. (Peter Portheine), and S.v.U.; Supervision, Y.T.H. and D.R.; Validation, P.P. (Pete Pättiniemi), P.P. (Peter Portheine) and S.v.U.; Writing—original draft, L.N.R., N.B., Y.T.H., E.D., P.G., K.D., D.R., P.P. (Pete Pättiniemi) and, P.P. (Peter Portheine) and S.v.U.; Writing—review and editing, L.N.R., N.B. and Y.T.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the EIT Urban Mobility grant 20036 for Shared micro depots for urban pickup and delivery (S.M.U.D.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BSD | Brainport Smart District |

| CDP | Collection-and-delivery point |

| dB | Decibels |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| LSP | Logistics service provider |

| MD | Micro depot |

| MAMCA | Multi-actor multi-criteria analysis MAMCA |

| UCC | Urban consolidation center |

References

- Savelsbergh, M.; Van Woensel, T. City logistics: Challenges and opportunities. Transp. Sci. 2016, 50, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joerss, M.; Schröder, J.; Neuhaus, F.; Klink, C.; Mann, F. Parcel Delivery: The Future of Last Mile; Technical Report September; McKinsey & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gevaers, R.; Van de Voorde, E.; Vanelslander, T. Cost modelling and simulation of last-mile characteristics in an innovative B2C supply chain environment with implications on urban areas and cities. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 125, 398–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Duin, J.R.; Quak, H.; Muñuzuri, J. New challenges for urban consolidation centres: A case study in The Hague. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010, 2, 6177–6188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tario, J.D.; Ancar, R.; Panero, M.; Hyeon-Shic, S.; Lopez, D.P. Urban Distribution Centers: A Means to Reducing Freight Vehicle Miles Traveled; Final Report; The New York State Energy Research and Development Authority: Albany, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, J.; Browne, M.; Woodburn, A.; Leonardi, J. The role of urban consolidation centres in sustainable freight transport. Transp. Rev. 2012, 32, 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, F.; Musolino, G.; Trecozzi, M. A system of models for the assessment of an urban distribution center in a city logistic plan. WIT Trans. Built Environ. 2013, 130, 799–810. [Google Scholar]

- Morganti, E.; Dablanc, L.; Fortin, F. Final deliveries for online shopping: The deployment of pickup point networks in urban and suburban areas. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2014, 11, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Cherrett, T.; McLeod, F.; Guan, W. Addressing the last mile problem: Transport impacts of collection and delivery points. Transp. Res. Rec. 2009, 2097, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.; Allen, J.; Leonardi, J. Evaluating the use of an urban consolidation centre and electric vehicles in central London. IATSS Res. 2011, 35, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janjevic, M.; Kaminsky, P.; Ndiaye, A.B. Downscaling the consolidation of goods-state of the art and transferability of micro-consolidation initiatives. Eur. Transp. Trasp. Eur. 2013, 3, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Stodick, K.; Deckert, C. Sustainable Parcel Delivery in Urban Areas with Micro Depots. In Mobility in a Globalised World 2018; Sucky, E., Kolke, R., Biethahn, N., Werner, J., Vogelsang, M., Eds.; University of Bamberg Press: Bamberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderluh, A.; Hemmelmayr, V.C.; Nolz, P.C. Synchronizing vans and cargo bikes in a city distribution network. Cent. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 25, 345–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlinde, S.; Macharis, C.; Milan, L.; Kin, B. Does a mobile depot make urban deliveries faster, more sustainable and more economically viable: Results of a pilot test in Brussels. Transp. Res. Procedia 2014, 4, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, I.; Borbon-Galvez, Y.; Verlinden, T.; Van de Voorde, E.; Vanelslander, T.; Dewulf, W. City logistics, urban goods distribution and last mile delivery and collection. Compet. Regul. Netw. Ind. 2017, 18, 22–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, J.; Hellström, D.; Pålsson, H. Framework of last mile logistics research: A systematic review of the literature. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosona, T. Urban Freight Last Mile Logistics—Challenges and Opportunities to Improve Sustainability: A Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perboli, G.; Tadei, R.; Vigo, D. The Two-Echelon Capacitated Vehicle Routing Problem: Models and Math-Based Heuristics. Transp. Sci. 2011, 45, 364–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Choy, K.L.; Ho, G.T.; Chung, S.H.; Lam, H. Survey of green vehicle routing problem: Past and future trends. Expert Syst. Appl. 2014, 41, 1118–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perboli, G.; Rosano, M. Parcel delivery in urban areas: Opportunities and threats for the mix of traditional and green business models. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 99, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marujo, L.G.; Goes, G.V.; D’Agosto, M.A.; Ferreira, A.F.; Winkenbach, M.; Bandeira, R.A. Assessing the sustainability of mobile depots: The case of urban freight distribution in Rio de Janeiro. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 62, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, A.; Fatisson, P.E.; Eickemeyer, P.; Cheng, J.; Peters, D. Urban micro-consolidation and last mile goods delivery by freight-tricycle in Manhattan: Opportunities and challenges. In Proceedings of the Transportation Research Board 91st Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 22–26 January 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Crainic, T.G.; Ricciardi, N.; Storchi, G. The-Day-Before Planning for Advanced Freight Transportation Systems in Congested Urban Areas; Université de Montréal, Centre de Recherche sur les Transports: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Crainic, T.G.; Ricciardi, N.; Storchi, G. Models for evaluating and planning city logistics systems. Transp. Sci. 2009, 43, 432–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Feliu, J.; Perboli, G.; Tadei, R.; Vigo, D. The Two-Echelon Capacitated Vehicle Routing Problem. 2008. Available online: https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00879447 (accessed on 4 June 2020).

- Quak, H.; Tavasszy, L. Customized solutions for sustainable city logistics: The viability of urban freight consolidation centres. In Transitions towards Sustainable Mobility; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011; pp. 213–233. [Google Scholar]

- Van Duin, R.; Slabbekoorn, M.; Tavasszy, L.; Quak, H. Identifying dominant stakeholder perspectives on urban freight policies: A Q-analysis on urban consolidation centres in the Netherlands. Transport 2018, 33, 867–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvidsson, N.; Pazirandeh, A. An ex ante evaluation of mobile depots in cities: A sustainability perspective. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2017, 11, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perboli, G.; Rosano, M.; Saint-Guillain, M.; Rizzo, P. Simulation–optimisation framework for City Logistics: An application on multimodal last-mile delivery. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2018, 12, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljohani, K.; Thompson, R.G. A stakeholder-based evaluation of the most suitable and sustainable delivery fleet for freight consolidation policies in the inner-city area. Sustainability 2019, 11, 124. [Google Scholar]

- Van Heeswijk, W.; Larsen, R.; Larsen, A. An urban consolidation center in the city of Copenhagen: A simulation study. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2019, 13, 675–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crainic, T.G.; Ricciardi, N.; Storchi, G. Advanced freight transportation systems for congested urban areas. Transp. Res. Part Emerg. Technol. 2004, 12, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, A.; Chauhan, S.S.; Goyal, S.K. A multi-criteria decision making approach for location planning for urban distribution centers under uncertainty. Math. Comput. Model. 2011, 53, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, C.; Goh, M.; Zhao, Y.; Zheng, J. Location selection of city logistics centers under sustainability. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2015, 36, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopha, B.M.; Asih, A.M.S.; Pradana, F.D.; Gunawan, H.E.; Karuniawati, Y. Urban distribution center location: Combination of spatial analysis and multi-objective mixed-integer linear programming. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2016, 8, 1847979016678371. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch, Y.; Golany, B. A parcel locker network as a solution to the logistics last mile problem. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwan, S.; Kijewska, K.; Lemke, J. Analysis of parcel lockers’ efficiency as the last mile delivery solution–the results of the research in Poland. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 12, 644–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Duin, J.; Wiegmans, B.; van Arem, B.; van Amstel, Y. From home delivery to parcel lockers: A case study in Amsterdam. Transp. Res. Procedia 2020, 46, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perboli, G.; Brotcorne, L.; Bruni, M.E.; Rosano, M. A new model for Last-Mile Delivery and Satellite Depots management: The impact of the on-demand economy. Transp. Res. Part Logist. Transp. Rev. 2021, 145, 102184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterom, J. The SMART Delivery Challenge; Unpublished work; Studio IlluStek: Breda, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. Urban Europe—Statistics on Cities, Towns and Suburbs; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016; pp. 3–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1596443911913&uri=CELEX:52019DC0640#document2 (accessed on 4 June 2020).

- Durand, P. On a Longer Lifetime for Products: Benefits for Consumers and Companies; Technical Report 47; European Parliment: Strasbourg, France, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Circular Economy Action Plan; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/circular-economy/pdf/new_circular_economy_action_plan.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2020).

- Monier, V.; Hestin, M.; Cayé, J.; Laureysens, A.; Watkins, E.; Reisinger, H.; Porsch, L. Development of Guidance on Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR). BIO Intelligence Service. In Collaboration with Arcadis; Ecologic Institute; Institute for European Environmental Policy (IEEP); Umweltbundesamt (UBA): Neuilly-sur-Seine, France, 2014; Available online: https://www.ecologic.eu/15139 (accessed on 4 June 2020).

- Brar, G.S.; Saini, G. Milk run logistics: Literature review and directions. In Proceedings of the World Congress on Engineering 2011, WCE 2011, London, UK, 6–8 July 2011; Volume 1, pp. 797–801. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament. Directive 2006/66/EC of the European Parliament and the Council of 6 September 2006 on batteries and accumulators and waste batteries and accumulators and repealing Directive 91/157/EEC. Off. J. Eur. Union 2006, 58, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Amazon. Amazon Day Delivery. 2020. Available online: https://www.amazon.com/b?ie=UTF8&language=en_US&node=17928921011 (accessed on 4 June 2020).

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; Capstone: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).