Abstract

The 1987 Canada-U.S. Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement required Remedial Action Plans (RAPs) be collaboratively generated between local stakeholders and government agencies to implement an ecosystem approach in cleaning up 43 historically polluted Areas of Concern (AOCs) throughout the Laurentian Great Lakes. The institutional arrangements that have emerged over the past 35 years to foster an ecosystem approach in RAPs are expected to have changed over time and be varied in some aspects—reflecting unique socio-ecological contexts of each AOC—while also sharing some characteristics that were either derived from the minimally prescribed framework or developed convergently. Here we surveyed institutional arrangements to describe changes over time relevant to advancing an ecosystem approach in restoring beneficial uses in the 43 AOCs. While eight AOCs evidenced little institutional change, the remaining 35 AOCs demonstrated a growing involvement of local organizations in RAPs, which has enhanced local capacity and ownership and helped strengthen connections to broader watershed initiatives. We also noted an expansion of strategic partnerships that has strengthened science-policy-management linkages and an increasing emphasis on sustainability among RAP institutions. Our study details how institutional arrangements in a decentralized restoration program have evolved to implement an ecosystem approach and address new challenges.

1. Introduction

An ecosystem approach is a socio-ecological style of resource conservation that accounts for the interrelationships among land, air, water, and all living things, including humans, and involves all user or stakeholder groups in comprehensive management and collaborative governance [1,2,3]. Collaborative governance is defined as the processes and structures of public policy decision-making and management that engage people constructively across the boundaries of public agencies, levels of government, and/or the public, private and civic spheres in order to carry out a public purpose that could not otherwise be accomplished [4]. While an ecosystem approach is considered an innovative and integrative management method for protecting, restoring, and improving the health of large ecosystems, applying it to ecosystems spanning multiple jurisdictions can be particularly challenging [5,6,7,8,9]. In this study, we seek to understand how institutional structures have evolved to adopt and promote the use of an ecosystem approach in a non-regulatory restoration program in the Laurentian Great Lakes.

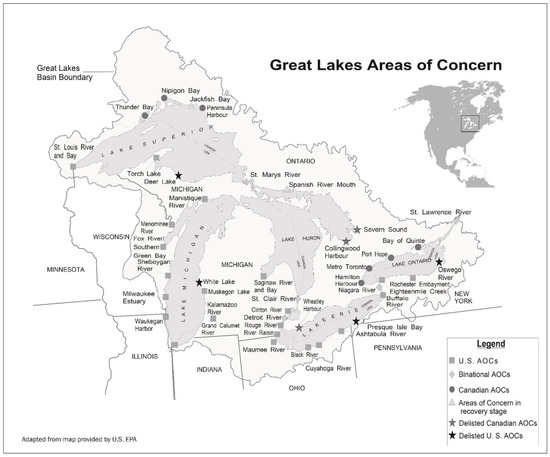

In 1985, an ecosystem-based model of management was introduced into the Laurentian Great Lakes under the auspices of the Canada-U.S. Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement (GLWQA). This agreement requires that collaboratively generated Remedial Action Plans (RAPs) in 43 historically polluted Areas of Concern (AOCs) (Figure 1) be developed and implemented using an ecosystem approach to restore impaired human and non-human Great Lakes uses, which are formally referred to as beneficial uses [3,10]. Annex 1 in the GLWQA outlines the 14 different beneficial use impairments (BUIs), which are caused by reductions in the chemical, physical, or biological integrity of the waters of the Great Lakes [3,10].

Figure 1.

The 43 Areas of Concern (AOCs) identified in the Laurentian Great Lakes Basin of North America. United States’ AOCs are represented by squares, Canadian AOCs by circles, and binational AOCs by diamonds. AOCs in the recovery stage (i.e., all remedial actions completed and monitoring of beneficial use restoration is underway) are indicated by a triangle and delisted AOCs are represented as stars (US: Black; CAN: Grey).

Over time, AOC restoration efforts have benefitted from several important sources of funding that demonstrated and required public and political support given the non-regulatory nature of RAPs. In Canada, early financial support was provided through the Great Lakes Cleanup Fund in the late 1980s and then replaced by the Great Lakes Sustainability Fund in 2000, which was later replaced by the Great Lakes Protection Initiative in 2017. Additionally, the Canada Ontario Agreement Respecting the Great Lakes Water Quality and Ecosystem Health has been an important source of Canadian funds since its inception in 1971 to present day. The establishment of the Great Lakes Legacy Act in 2002 was the first major source of US public funds to support restoration. This was followed by the establishment of Great Lakes Restoration Initiative in 2010, which has received $3.48 billion USD between 2010–2019 with more than a third of those funds distributed to the “Toxic Substances and AOC” focus area (https://www.glri.us/funding). RAP-related expenditures from several different funding sources in both countries totaled $22.78 billion USD countries between 1985–2019 [11]. The financial support generated to support RAPs is, in and of itself, a success and has been important to sustaining progress in AOC restoration.

The incorporation of RAPs into the 1987 Protocol to the GLWQA gave the program legitimacy [2] and represented a shift in the governance paradigm that promoted shared decision-making among stakeholders through local public advisory councils (PACs) and/or other institutional arrangements. Institutional arrangements refer to the organizational structures and mechanisms to achieve cooperative and coordinated planning and action among different organizations whose missions impact or are impacted by uses in AOCs [6,12,13]. While the most basic objective of RAPs is to shed the AOC designation (i.e., delist) by remediation and restoration of all known BUIs, the RAP process also aims to promote collaborative governance that emphasizes stakeholder empowerment [12,13]. Collaborative governance provides an interesting template for studying non-regulatory restoration and revitalization initiatives implemented in a largely decentralized manner (i.e., planning, implementation, and coordination mostly occurs at the sub-federal and local level across multiple jurisdictions instead of being led by a single authoritative entity). While RAPs are intended to be unique, place-based approaches, collaboration among all levels of government and stakeholder groups is essential for collective success around a common goal [14,15,16]. However, the success of RAPs in adopting and implementing an ecosystem approach has been variable and may reflect differences in local context, which can affect the degree and value of public involvement [17]. Variability in use of an ecosystem approach might also be explained through the diffusion of innovation theoretical framework, where successful RAPs involved organizations that saw the potential of the program and made it work in their AOC [15]. Kellogg [15] highlights that while the role of local stakeholder groups may differ across AOCs, they are often critical for shaping the process of lead governmental agencies in adopting an ecosystem approach. Therefore, the varied level and nature of stakeholder involvement across different AOCs would plausibly produce variability in how the locally defined approach is implemented.

The 35-year experience with RAPs provides an opportunity to investigate how local adaptation of a common management strategy unfolds in a large, institutionally rich region like the Great Lakes. In 1987, the GLWQA specifically called for broad-based public participation (i.e., the democratic way for governments and nongovernmental groups to receive public input that facilitates the identification of community goals and enables plan-makers to develop and implement appropriate plans) in RAPs without outlining clear methods for engagement. The vagueness of this mandate has encouraged locally designed ecosystem approaches to fit the unique biophysical, socioeconomic, and political contexts of each AOC. As a result, it is expected that the modern-day institutional arrangements around RAPs exhibit differences driven by local factors while maintaining certain commonalities either derived from the original institutional framework or perhaps developed convergently. However, the degree of difference in how institutional arrangements have evolved to incorporate and implement an ecosystem approach in RAPs has not been characterized but could provide useful insights into common factors of successful RAP institutional structures [18]. Moreover, understanding the role institutional arrangements play in driving and sustaining action from non-regulatory environmental policy has implications for designing and implementing other integrated resource management initiatives in the Great Lakes and elsewhere in the world [19].

The purpose of this study is to assess how RAP institutional arrangements have changed over time to apply an ecosystem approach in restoring uses and to address new and ongoing needs in each AOC. We surveyed the institutional arrangements specific to each AOC to describe changes over time and documented important changes relevant to the successful use of an ecosystem approach in restoring beneficial uses in the 43 AOCs (38 AOCs solely in either the United States or Canada; five binational AOCs, including three binational AOCs with two separate RAP processes).

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a content analysis using online sources, including RAP documents, websites, or other types of media generated by involved organizations to assess changes in institutional structures since RAP initiation in 1985. RAP documents were the starting point for identifying how RAP institutional arrangements have changed over time. These documents were found at AOC’s respective federal (i.e., https://www.epa.gov/great-lakes-aocs or https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/great-lakes-protection/areas-concern.html) and state/provincial agency’s websites or from the PAC’s website, if one existed. In some cases, peer-reviewed and grey literature (e.g., technical reports or theses and dissertations) were reviewed, if pertinent, to characterize RAP institutional structures and their evolution. When publicly available information was lacking, we corresponded with people involved in RAP institutional arrangements for more information.

Our analysis focused on the structural and functional components of institutional arrangements and their evolution. We employed an analytical framework that was comprised of a list of questions that guided our survey and a coding framework to further guide and interpret the data (Table 1). Our list of questions aimed at eliciting descriptive characteristics of the structure of institutional arrangements and their change over time included:

Table 1.

Key characteristics of effective institutional arrangements designed to ensure stakeholder involvement and foster use of an ecosystem approach in RAP development and implementation for Great Lakes Areas of Concern (derived from literature [12,20]).

- How many AOC institutional structures changed over time and how?

- Who are the typical actors involved in RAPs and what are their roles? How has this changed over time?

- Has the RAP process led to the emergence of new institutions with foci specific or tangential to the RAP?

- From 1985 to present, how many AOCs have established a nonprofit organization?

- How many AOC institutional structures reference life after delisting or sustainability?

- How were pre-existing institutions modified to accommodate the RAP and stakeholder needs?

- How have the roles of institutions and relation among institutions changed over time to address new challenges and needs?

- Does the AOC fall within the jurisdiction of any regulatory cleanup programs (e.g., Superfund, enforcement actions, Resource Conservation and Recovery Act) and, if so, how has this affected RAP institutional structure and function?

Our coding framework is based on eight key structural/functional characteristics associated with successful stakeholder involvement and use of an ecosystem approach in RAPs (Table 1). These key characteristics summarize the organizational and process qualities necessary for long-term success of RAPs and were developed from a review of RAP literature [12,20] and other ecosystem-based work (e.g., [21]). These eight characteristics were used to help evaluate data from surveyed documents in the context of use of an ecosystem approach in RAPs and restoration of beneficial uses as called for in the GLWQA. We also documented any institutional changes that did not conform to this analytical framework but were important to understanding the evolution of a given institutional arrangement. Summaries of institutional arrangements and how they evolved are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Evolution of RAP institutional structures for use of an ecosystem approach in restoring Great Lakes AOCs, 1985–2019. Table entries are listed in a geographic order from east to west with exception of binational AOCs, which are listed at the end.

3. Results

Four notable institutional adaptations were apparent from our survey. While eight AOCs evidenced little institutional change, the remaining 35 AOCs demonstrated a growing involvement of local organizations in RAPs, new mechanisms connecting RAPs to their watersheds, an expansion of strategic partnerships, and an increasing focus on the future (Table 3).

Table 3.

Main findings of common institutional changes in Areas of Concern (AOCs) that promote the use of an ecosystem approach as deduced from survey results. Each finding is contextualized by the corresponding relevant key characteristic(s) presented in Table 1 and select examples.

3.1. Growing Involvement of Local Organizations in RAPs

Institutional arrangements in 35 of the 43 AOCs evolved over time into structures with broad stakeholder representation and active public participation. In most AOCs, organizational mechanisms for public engagement in AOC restoration were initiated by the formation of PACs. However, RAPs were bolstered in some AOCs by pre-existing local institutions or management frameworks at the outset of the program that had the capacity, understanding, and motivation to support the RAP, e.g., Rochester Embayment and Clinton River (Table 2). Over time, stakeholder representation and involvement of local organizations was broadened in most RAPs. Our survey indicates arrangements that were most evolved often included an integrative institution that was typically a nongovernmental organization (NGO), with exception to a few RAPs where municipal and county level governments played pivotal roles, e.g., Rochester Embayment’s Water Quality Management Agency (Table 2). Integrative organizations have enhanced public involvement and often were nonprofit organizations in the United States or Conservation Authorities in Canada. In our survey we also found that 32 of the 43 AOCs have established nonprofit organizations or Conservation Authorities to help build capacity, implement management actions, promote public education, and cultivate environmental stewardship. These organizations often fill many roles (e.g., public education and outreach, goal setting, research and monitoring, engaging local officials) and address many of the critical elements required of RAP institutional arrangements for implementing ecosystem-based management. The establishment and growth of these organizations has helped build local capacity and ownership, broadened the timeline of thinking to consider life after delisting, enabled a watershed focus, and, in several cases, strengthened the connection of science, policy, and management (Table 2 and Table 3).

3.2. Enhanced Institutional Mechanisms for Connecting RAPs to Their Watersheds

Institutional arrangements have also become increasingly more connected to external networks and organizations working within the same watershed (Table 2 and Table 3). Organizations involved in the RAP often served as the mechanism connecting their mission of use restoration to the management of the encompassing watershed. For instance, the expansion of the organization Friends of the Buffalo River into the present-day group the Buffalo-Niagara Waterkeeper helped integrate the Niagara River RAP into restoration efforts elsewhere in the watershed (Table 2) [27]. Our survey found that in some AOCs it was sometimes deemed most efficient and effective to solve use impairments on a smaller geographic scale and work in and through a broader institutional framework to achieve watershed goals. Some of these broader institutional frameworks were RAP-centric (i.e., they originated from the RAP process with the purpose of supporting the RAP) or were centered around aspects of watershed management not derived from the RAP. For example, the Partnership for the Saginaw Bay Watershed PAC, which merged the Saginaw Basin Alliance and the Saginaw Bay Watershed Council, has voting representatives from each of its subwatersheds and also works closely with The Saginaw Bay Watershed Initiative Network to solve problems on a watershed scale (example of RAP-centric watershed framework) [28]. Contrasting this are non-RAP-centric frameworks such as in the Rochester Embayment AOC, where the Monroe County Water Quality Management Advisory Committee serves as the RAP institutional structure and coordinates with the Water Resources Board of the Finger Lakes—Lake Ontario Watershed Protection Alliance to coordinate efforts on a watershed scale (Table 2 and Table 3) [29,30]. In Ontario, the four north shore Lake Superior PACs have evolved from a government-led initiative to ones that are now led by Lakehead University with a partnership with EcoSuperior, a nonprofit organization promoting stewardship in the Lake Superior basin (Table 2).

3.3. Expansion of Strategic Partnerships

Most institutional arrangements that have advanced RAP progress have created and expanded strategic partnerships among stakeholders. Common partnerships within the RAP institutional arrangement include interagency partnerships, partnerships between and among NGOs and PACs, public-private partnerships, and partnerships with universities. Partnerships were strategic in that they specifically enhanced the RAP by pooling resources, strengthening extension and outreach efforts, and/or increasing research and monitoring capacity. In several AOCs, partnerships with NGOs were initiated early on to help PACs with administrative, fiduciary, and/or technical support, and later often evolved to emphasize public outreach and education efforts, e.g., Friends of the St. Clair River (Table 2). Partnering with universities was documented in many AOCs as well, including Hamilton Harbour with McMaster University and the Wisconsin AOCs in which University of Wisconsin-Extension helped facilitate the process and contribute to public outreach and education efforts. University involvement in AOCs typically was either in public outreach and education, research and monitoring, or centralizing information. Interagency partnerships and public-private partnerships helped leverage expertise from different agencies and stakeholders while also pooling technical and financial resources, e.g., Ashtabula River Partnership (Table 2). In some AOCs, nonprofit organizations were recruited to help revitalize the RAPs and lead restoration efforts, e.g., Buffalo Niagara Waterkeeper for Buffalo River and Friends of the Detroit River for the U.S. portion of the Detroit River (Table 2).

3.4. Increasing Focus on the Future

We found that 30 of the 43 AOCs now recognize “life after delisting” or “sustainability” as part of their focus. In these AOCs, organizations have typically become the institutional mechanism for ensuring continued use of an ecosystem approach. For example, the Environmental Network of Collingwood remains active in promoting sustainability 26 years after delisting Collingwood Harbour as an AOC. In some AOCs, sustainability is being promoted through several avenues. Such is the case in the former White Lake AOC, where the Muskegon Conservation District has established an environmental stewardship program while the former PAC has reorganized into what is now called the White Lake Environmental Network through which they focus on sustaining momentum into revitalization (Table 2). The increasing prevalence of sustainability-driven organizations and programs suggests that institutional arrangements are evolving beyond the original intended scope of the AOC program (i.e., delisting) and that the program has become more effective over time through strategic partnerships that focus on stewardship and sustainability.

4. Discussion

The changes to institutional arrangements summarized above provide useful lessons for understanding how institutional structures can promote the use of an ecosystem approach in RAPs. The growing presence of integrative organizations has increased public participation, local ownership and capacity, and has enhanced connections between the RAP and their watersheds. Strategic collaborations and partnerships have strengthened science-policy-management linkages giving RAP institutions a greater adaptive capacity in addressing new and ongoing challenges. Additionally, sustainability has emerged as an objective, which highlights how building community support can foster a stewardship ethic that is necessary for advancing and preserving progress in remediation, restoration, and revitalization of the waterway. Our study also indicates that static institutional arrangements can be explained by the strength of their original structures and their unique regulatory contexts.

4.1. Growing Presence of Integrative Organizations

4.1.1. Integrative Organizations Increase Public Participation

The growing roles of local organizations in RAPs noted in our survey indicate that many institutional arrangements have evolved into structures with broad stakeholder representation and active public participation. The importance of strong local involvement in the RAP was well characterized by Krantzberg and Rich [31] who explain how an explicit focus on developing an inclusive process helped nurture local capacity in Collingwood Harbour. They demonstrate how true public participation, as opposed to mere consultation, can legitimize RAPs by supporting participatory decision-making and capacity building that is beneficial to sustaining progress throughout remediation and beyond delisting. However, recruiting and sustaining active stakeholder engagement is a challenge for many AOCs [14]. Williams (2015) [32] identified three components to effective participation in RAPs: (1) the state/province needs to create the opportunity for a local RAP organization to contribute; (2) there should be a meaningful way for citizens or advisory councils to contribute; and (3) there should be opportunities for mutual learning. Our results suggest that opportunities for public participation have been enhanced and capitalized on by local AOC actors as institutional arrangements have evolved.

We found that strong public participation was often led by local organizations that helped creatively connect the public to the RAP process. These were typically NGOs, although in some AOCs this role was attributed to local government, e.g., Rochester Embayment (Table 2), or distributed among multiple organizations, e.g., Rouge River (Table 2). We refer to these organizations as ‘integrative’ because they assimilate the perspectives of stakeholders and the public into the RAP process, they connect the RAP to other environmental and economic programs locally and regionally, and they incorporate the RAP’s goal of restoration into their own organizational objectives or mission. Additionally, these organizations were sometimes convening bodies that helped coordinate multiple agencies in RAP implementation, such as the St. Louis River Alliance for St. Louis River AOC and the Clinton River Watershed Council for the Clinton River AOC (Table 2). The increasing involvement of organizations like these is evidenced by the fact that 32 of 43 AOCs have established nonprofit organizations or worked closely through Conservation Authorities, which demonstrates a notable increase from the 14 AOCs with active nonprofits reported by Hartig and Law [12] more than 25 years ago. Thus, the growing presence of integrative organizations that rallies the community around the RAP is not only characteristic of the evolution of institutional arrangements, but also may be indicative of an empowered arrangement where the locus of environmental governance and stewardship is becoming increasingly local.

4.1.2. Increasing Public Involvement and the Resulting Increase of Local Ownership and Capacity

The growing roles of local organizations might reflect a growing sense of ownership and empowerment among local entities and stakeholders involved in the restoration and revitalization process. Local ownership can help sustain the recovery of beneficial uses thereby helping to ensure the societal, economic, and environmental sustainability of the local community [33]. From the outset of RAPs in 1985, it was recognized that these processes would not be successful if they were implemented in a top-down, command-and-control fashion, rather they would need to be undertaken in a bottom-up collaborative fashion that achieves local ownership [1]. Increasing stakeholder involvement in RAPs has cultivated local ownership and built the capacity of local governmental and nongovernmental organizations to assess issues and opportunities, creatively solve problems, acquire necessary resources, and implement remedial and preventive actions [12,33,34,35]. Since the beginning of the RAP program in 1985, three AOCs have stood out for immediately recognizing the importance of local ownership to solve problems and developing a locally designed ecosystem approach to restore impaired beneficial uses: Fox River/Green Bay, Hamilton Harbour, and Rouge River [1] (Table 2). In another example, Zeemering (2018) [34] demonstrated how Chippewa County Health Department, which has a representative in the St. Mary’s River AOC’s Binational PAC, became more involved over time with water quality monitoring that helped leverage relationships within and outside of the AOC program’s network to improve monitoring. This helped justify future funding for remediation—demonstrating how capacity building through engaging local stakeholders can foster local ownership that improves success of restoration efforts. The growing roles of local organizations noted in our survey not only support a general trend of increasing local ownership across AOCs documented in the literature, but it also signifies a growing capacity for more sustainable management decisions that can help maintain momentum through delisting and transition into a future with less government involvement typical of the past 35 years.

4.1.3. Organizations as Institutional Mechanisms for Connecting RAPs to Their Watersheds

It is generally accepted that a watershed is the appropriate unit for water resource planning and management [36], and our survey noted how many RAP institutional arrangements have evolved to enhance collaboration throughout watersheds and with multiple jurisdictions to restore beneficial uses. As documented in Table 2 and Table 3, local or regional nonprofit organizations were often important conduits for connecting RAPs to other watershed level initiatives. The realization that RAP objectives were inherently linked to the health of the surrounding watershed has been vital to advancing RAPs. For instance, early in the Rouge River RAP, stakeholders learned that to solve their problems of the release of raw sewage from 168 combined sewer overflows and urban stormwater runoff it would take collaboration among all 48 watershed communities and three counties [37]. The incorporation of the Alliance of Rouge Communities, whose purpose is to “provide an institutional mechanism to encourage watershed-wide cooperation and mutual support to meet water quality permit requirements and to restore beneficial uses of the Rouge River to the area residents” [37] exemplifies how a watershed focus can be reflected in institutional arrangements. Thus, elevating the watershed perspective is another example of how local organizations have supported and facilitated an ecosystem approach in RAPs.

4.2. Strategic Collaborations and Partnerships

Our survey highlights how many RAP institutional arrangements have grown from and evolved into a series of strategic collaborations and partnerships. Cleanup of AOCs has not been easy and required networks focused on gathering stakeholders, coordinating efforts, securing funding, and ensuring desired results are achieved. Effective collaboration in RAPs requires cooperative learning that involves stakeholders working in teams to accomplish a common goal under conditions that involve positive interdependence (i.e., all stakeholders cooperate to complete a task) and individual and group accountability [38]. In some AOCs, an integrative organization helped to foster collaboration, while in other AOCs these partnerships developed organically. For example, the Clinton River Watershed council convened stakeholders and coordinated implementation among involved stakeholders through a partnership agreement (Table 2). In contrast, the ongoing evolution of the St. Lawrence River Restoration Council at Cornwall is the product of collaboration of multiple entities and has become an integrative organization in itself (Table 2). Furthermore, collaboration, partnerships, and capacity building are critical to success of RAPs. For example, partnerships and collaborative funding were essential to achieving: over $1 billion in combined sewer overflow and urban stormwater controls in the Rouge River AOC; $180 million (Canadian) in habitat rehabilitation in the Toronto and Region AOC; $86 million of contaminated sediment remediation in the Ashtabula River AOC; and $110 million cleanup of the Severn Sound AOC [11]. Another example of innovative partnerships and collaboration among stakeholders is the four North Shore of Lake Superior AOCs (i.e., Peninsula Harbour, Jackfish Bay, Nipigon Bay, and Thunder Bay), where the Lake Superior Programs Office played an instrumental role in early RAP development and implementation.

RAPs have been one of the principal programs to operationalize use of an ecosystem approach in management of the Great Lakes, invoking new governance paradigms [39]. Collaborative governance makes it possible to address actions that serve a public purpose by engaging groups and individuals across different institutions and spheres of society [4]. A recent analysis of connecting river RAPs found that the establishment of informal networks stemming from formal agreements resulted in individuals and groups completing partnership projects appropriate to their capacities and roles [40]. Key partnership success factors include effective working relationships, trust among partners, clarity of roles and responsibilities, well-recognized benefits to all, and effective facilitation.

Partnering with Scientific Institutions Has Strengthened Science-Policy-Management Linkages and Can Cultivate Local Scientific Capacity

The results from our survey suggest that the involvement of universities and local science centers in RAP institutional arrangements has helped to strengthen the science-policy-management connection in the AOC. Although some RAP institutional structures have scientists as members, that is not always the case. Linkages to universities and research centers are needed to help understand cause-and-effect relationships, translate science, evaluate remedial options, track progress, set priorities, and implement actions in an iterative fashion for continuous improvement [11]. We chose to distinguish partnerships with scientific institutions from other strategic partnerships because it is required to implement adaptive management and highlights the benefit of building local scientific capacity that can contribute to that management. From our survey, we found that RAP institutions that did this best sought, created, and acted on opportunities to cultivate local scientific capacity that enhanced the value of science and adaptive management outlined in the RAP. Some examples include the St. Lawrence River Institute of Environmental Science that has bolstered local research capacity at the St. Lawrence at Cornwall AOC, efforts by Lakehead University to centralize information and facilitate restoration of the North Shore AOCs on the InfoSuperior website they maintain, Canada Centre for Inland Waters’ applied research and science transfer that supports the Hamilton Harbour RAP, the Great Lakes Institute for Environmental Research of the University of Windsor that has performed necessary research in support of removing beneficial use impairments, and the River Raisin Institute’s centralization and synthesizing of water quality data into actionable plans that contribute to watershed restoration (Table 2 and Table 3).

4.3. Promoting Sustainability and Fostering a Stewardship Ethic

Concern among some RAP practitioners is that AOC delisting can result in loss of momentum due to lack of a tangible reason to organize, loss of important sources of funding, and less frequent environmental monitoring [23]. As cleanup nears completion, many AOCs are considering “life after delisting” and exploring how to leverage remedial and preventive actions to advance broader social and economic revitalization in waterfront areas [41]. In total, our survey found that 30 of the 43 AOCs mention “life after delisting” and/or sustainability (Table 2 and Table 3). This suggests the purpose of institutional arrangements are evolving beyond the original goal of delisting an AOC, into a longer-term focus on sustainability. Language regarding sustainability or life after delisting was often found in the mission statements or objectives of local organizations involved with the RAP. The tangible effect of this language has been a concerted effort to foster a stewardship-minded populace. In recent years, more emphasis is being placed on how AOC cleanup leads to reconnecting people to waterways that then leads to waterfront revitalization [42,43]. As AOC communities look to the future, local organizations will likely play a key role in reconnecting people to their restored waterfront in order to promote community revitalization.

4.4. Factors Related to Static Institutional Arrangements

Institutional arrangements remained relatively static in eight AOCs (i.e., Torch Lake, MI, Deer Lake, MI, Manistique River, MI, Lower Menominee River, MI/WI, Waukegan Harbor, IL, Wheatley Harbour, ONT, Oswego River, NY, and Port Hope, ON). This lack of substantial change does not equate to lack of RAP progress as three of these AOCs have been delisted (i.e., Deer Lake, Oswego River, and Wheatley Harbour) and two have completed all management actions identified in their Stage 2 RAPs (i.e., Lower Menominee River and Waukegan Harbor). In general, we believe that the lack of change indicates that the original institutional structures were well-suited to handle challenges and implement remedies. For instance, Waukegan Harbor’s institutional structure was broad and effective in building partnerships with capacity-building organizations. The problems in Waukegan Harbor were also clearly defined with regulatory agencies playing the key role in the cleanup of PCB-contaminated soils and sediment, resulting in all management actions being completed within five years of the Stage 2 RAP [44]. Cleanup remedies with clear and well recognized regulatory program responsibilities may also explain the lack of institutional evolution in some AOCs. Indeed, a majority of the eight AOCs with stable institutional structures had use impairments and problems that were being addressed under regulatory cleanup programs like the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA, i.e., Superfund) or the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) in addition to being an AOC. In Port Hope, Ontario, cleanup of radionuclide waste is being undertaken through regulatory programs of the Canadian federal government. Regulatory programs are inherently top-down driven processes and can rely on enforcement and liability to initiate clean ups [45]. In these AOCs, regulatory cleanup programs took precedence over voluntary efforts. Furthermore, federal funds and responsible parties typically finance regulatory cleanups so there is less need for creative and collaborative financing by local organizations.

4.5. Comparison with Other Experiences throughout the World

Comparing the nature, mechanisms, and level of public participation in RAPs to conservation management initiatives elsewhere in the world can shed light on common challenges and potentially useful strategies for overcoming barriers to effective implementation. The call for public involvement through PACs brought the public into the process at its outset. As PACs and institutional arrangements evolved, they became forums that helped establish trust amongst stakeholders, promoted shared learning and decision-making, and oriented decision-makers and managers towards an ecosystem approach [12]. Collaboration and inclusivity have been guiding principles in the RAP planning and implementation process and should be an aspiration for all forms of polycentric resource governance. However, establishing and sustaining valuable public involvement in non-regulatory programs is not a challenge unique to the AOC program and its absence in a program can be a barrier to implementation. While seeking to identify governance bottlenecks in the implementation of the European Union’s Water Framework Directive, Zingraff-Hamed et al. [7] noted how practitioners thought public involvement was insufficient at every step of the implementation process, and that participatory decision-making was not common and even rejected at times. In the AOC program, a present challenge is in sustaining active stakeholder participation, which Holifield and Williams [14] suggest can be addressed through a committed focus to cultivating relationships between stakeholders and managers as well among stakeholders themselves. Our research speaks to the strength of relationship building and broad participation at an institutional level (Table 3), which has been touted as an important and transferable characteristic of effective governance in other sustainable resource management approaches, e.g., Integrated Strategies for Sustainable Urban Development in Barcelona [46] or the ‘Living Labs’ concept [47]. Overall, investment in building stakeholder networks and relationships at individual and institutional levels could be a particularly useful strategy for improving public participation in the implementation of collaborative resource governance.

The diverse and influential roles NGOs have in advancing and supporting RAPs has implications for voluntary conservation efforts internationally. RAPs lack regulatory authority and strong legislative mandates, so the success of RAPs is derived from a stewardship ethic that comes from the cultivation of an individual and collective sense of place—meaning a personal connection to a location [2]. Local nonprofits have been useful toward this end because many seek to connect communities to the watersheds they reside in through citizen science, educational campaigns, and engaging local leaders. The recognition of formally organized community groups as effective mechanisms for implementing bottom-up initiatives is also evident elsewhere in the world. In their survey of 63 community-based initiatives in Europe, Celata and Colleti [48] found that nonprofits are often the best-equipped form of community-based initiative in acquiring financial resources and support in conducive political environments. In areas of the world where government capacity and involvement in certain initiatives is minimal, NGOs have often filled the leadership void and have become increasingly involved with capacity development and local empowerment [49]. We found that nonprofits often served as the integrative organization in an AOC and had great flexibility in their roles, which mirrors what Celata and Colleti [48] report for the community-based conservation initiatives they studied. Our results paired with the international literature suggests that NGOs are an important component to the sustained success of non-regulatory conservation programs and can complement government involvement when present.

5. Conclusions

The Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement charge to use an ecosystem approach in RAPs challenged governments and other stakeholders to transform management. RAPs represent a shift in governance paradigm by sharing decision-making among stakeholders through local PACs, stakeholder groups, and other institutional structures. Experience has shown that there is no single best approach to implementing an ecosystem approach in RAP development and implementation, rather it is fair to say that there were 43 locally designed ecosystem approaches that helped involve stakeholders in a meaningful way, foster cooperative learning, share decision-making, and ensure local ownership.

Institutional arrangements in 35 of the 43 AOCs evolved since 1985 to improve effectiveness, transition to implementation, and ensure relevancy and sustainability. Since 1985, 32 of the 43 AOCs have established a nonprofit organization or worked with one that has built capacity and helped secure necessary funding. Continued research and cooperative learning are needed to help these institutional structures grow and evolve to meet long-term goals of sustainability.

Considerable work is underway throughout the world to foster use of an ecosystem approach and practice ecosystem-based management practices. It is recommended that an international conference be convened to share practical experiences in the use of an ecosystem approach in management, including its origin, status, and how it can fully maximize its impact on the Great Lakes and elsewhere.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H.H. and P.J.A.; Investigation, P.J.A. and J.H.H.; Funding Acquisition, J.H.H. Writing—Original Draft Preparation, P.J.A. and J.H.H.; Writing—Review & Editing, K.C.W., J.W. and G.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Erb Family Foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the RAP stakeholders who provided input and spoke with us about their AOC. We are grateful to the Erb Family Foundation for providing the entirety of funds that supported this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hartig, J.H.; Vallentyne, J.R. Use of ecosystem approach to restore degraded areas of the Great Lakes. J. Hum. Environ. Res. Manag. 1989, 18, 423–428. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie, S.H. Toward integrated resource management: Lessons about the ecosystem approach from the Laurentian Great Lakes. Environ. Manag. 1997, 21, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Governments of Canada; United States of America. Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement; Governments of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada; United States of America: Washington, DC, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, K.; Nabatchi, T.; Balogh, S. An integrative framework for collaborative governance. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2012, 22, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodin, Ö. Collaborative environmental governance: Achieving collective action in social-ecological systems. Science 2017, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetoo, S.; Thorn, A.; Friedman, K.; Gosman, S.; Krantzberg, G. Governance and geopolitics as drivers of change in the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence basin. J. Great Lakes Res. 2015, 41, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingraff-Hamed, A.; Schröter, B.; Schaub, S.; Lepenies, R.; Stein, U.; Hüesker, F.; Meyer, C.; Schleyer, C.; Schmeier, S.; Pusch, M.T. Perception of bottlenecks in the implementation of the european water framework directive. Water Altern. 2020, 13, 458–483. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. A General Framework for Analyzing Sustainability of Social-Ecological System. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, G. Trajedy of the Commons. Science 1968, 162, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar]

- Great Lakes Water Quality Board. Report on Great Lakes Water Quality; International Joint Commission: Windsor, ON, Canada, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig, J.H.; Krantzberg, G.; Alsip, P. Thirty-five years of restoring Great Lakes Areas of Concern: Gradual progress, hopeful future. J. Great Lakes Res. 2020, 46, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, J.H.; Law, N. Institutional frameworks to direct development and implementation of great lakes remedial action plans. Environ. Manag. 1994, 18, 10–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krantzberg, G. Revisiting governance principles for effective Remedial Action Plan implementation and capacity building. Aquat. Ecosyst. Health Manag. 2018, 21, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holifield, R.; Williams, K.C. Recruiting, integrating, and sustaining stakeholder participation in environmental management: A case study from the Great Lakes Areas of Concern. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 230, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellogg, W.A. Adopting an ecosystem approach: Local variability in remedial action planning. Soc. Nat. Resour. 1998, 11, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zingraff-Hamed, A.; Hüesker, F.; Lupp, G.; Begg, C.; Huang, J.; Oen, A.; Vojinovic, Z.; Kuhlicke, C.; Pauleit, S. Stakeholder mapping to co-create nature-based solutions: Who is on board? Sustainability 2020, 12, 8625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landre, B.K.; Knuth, B.A. The role of agency goals and local context in great lakes water resources public involvement programs. Environ. Manag. 1993, 17, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manno, J. Great Lakes Water Quality Board Position Statement on the Future of Great Lakes Remedial Action Plans September 1996. J. Great Lakes Res. 1997, 23, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Violette, N. A Comparison of Great Lakes Remedial Action Plans and St. Lawrence River Restoration Plans. J. Great Lakes Res. 1993, 19, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, J.H.; Krantzberg, G.; Munawar, M.; Doss, M.; Child, M.; Kalinauskas, R.; Richman, L.; Blair, C. Achievements and lessons learned from the 32-year old Canada-U.S. effort to restore Impaired Beneficial Uses in Great Lakes Areas of Concern. Aquat. Ecosyst. Health Manag. 2018, 21, 506–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondolleck, J.M.; Yaffee, S.L. Marine Ecosystem-Based Management in Practice: Different Pathways, Common Lessons; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gurtner-Zimmermann, A. Analysis of Lower Green Bay and Fox River, Collingwood Harbour, Spanish Harbour, and the Metro Toronto and Region Remedial Action Plan (RAP) processes. Environ. Manag. 1996, 20, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelia, A. Great Lakes Areas of Concern: Life after Delisting an Investigation Conducted at the International Joint Commission Great Lakes Regional Office; International Joint Commission: Windsor, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Niagara River Restoration Council. Niagara River Remedial Action Plan Stage 2 Report; Ministry of Environment and Energy: Hamilton, ON, Canada, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ritcey, A.L. The Future of the St. Lawrence River at Cornwall, Ontario Post-Remedial Action Plan (RAP) Navigating Toward Sustainability. Master’s Thesis, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Muskegon Lake Watershed Partnership. Muskegon Lake Action Plan; Muskegon Lake Watershed Partnership: Muskegon, MI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- The History of Buffalo Niagara Waterkeeper. Available online: https://bnwaterkeeper.org/history/ (accessed on 5 October 2020).

- Partnership for Saginaw Bay Watershed Operations Manual. 2015. Available online: http://psbw.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/PSBWOperationsManual_wAppendices.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2020).

- Finger Lakes—Lake Ontario Watershed Protection Alliance. 2012 Lake Ontario Watershed Basin Forum: Community Visioning Workshop Series Summary; Finger Lakes—Lake Ontario Watershed Protection Alliance: Fulton, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe County Department of Health. Rochester Embayment Remedial Action Plan: Stage 2; Monroe County Department of Planning and Development: Rochester, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Krantzberg, G.; Rich, M. Life after delisting: The Collingwood Harbour story. Aquat. Ecosyst. Health Manag. 2018, 21, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.C. Relationships, Knowledge, and Resilience: A Comparative Study of Stakeholder Participation in Great Lakes Areas of Concern. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2015; p. 177. [Google Scholar]

- Krantzberg, G. Sustaining the gains made in ecological restoration: Case study Collingwood Harbour, Ontario. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2006, 8, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeemering, E.S. Comparing Governance and Local Engagement in the St. Marys River Area of Concern. Am. Rev. Can. Stud. 2018, 48, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beierle, T.C.; Konisky, D.M. What are we gaining from stakeholder involvement? Observations from environmental planning in the Great Lakes. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2001, 19, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council. New Strategies for America’s Watersheds; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ridgway, J.; Cave, K.; DeMaria, A.; O’Meara, J.; Hartig, J.H. The Rouge River Area of Concern-A multi-year, multi-level successful approach to restoration of Impaired Beneficial Uses. Aquat. Ecosyst. Health Manag. 2018, 21, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, J.H.; Zarull, M.A.; Law, N.L. An ecosystem approach to Great Lakes management: Practical steps. J. Great Lakes Res. 1998, 24, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krantzberg, G. Examining governance principles that enable RAP implementation and sustainable outcomes. In Ecosystem-Based Management of Laurentian Great Lakes Areas of Concern: Three Decades of U.S.-Canadian Cleanup and Recovery; Hartig, J.H., Munawar, M., Eds.; Ecovision World Monograph Series; Aquatic Ecosystem Health and Management: Burlington, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Child, M.; Read, J.; Ridal, J.; Twiss, M. Symmetry and solitude: Status and lessons learned from binational Areas of Concern. Aquat. Ecosyst. Health Manag. 2018, 21, 478–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.; Hoffman, J.; Bolgrien, D.; Angradi, T.; Carlson, J.; Clarke, R.; Fulton, A.; Timm-Bijold, H.; MacGregor, M.; Trebitz, A. How the Community Value of Ecosystem Goods and Services Empowers Communities to Impact the Outcomes of Remediation, Restoration, and Revitalization Projects; US Environmental Protection Agency: Duluth, MN, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Angradi, T.R.; Williams, K.C.; Hoffman, J.C.; Bolgrien, D.W. Goals, beneficiaries, and indicators of waterfront revitalization in Great Lakes Areas of Concern and coastal communities Goals, beneficiaries, and indicators of waterfront revitalization in Great Lakes Areas of Concern and coastal communities. J. Great Lakes Res. 2019, 45, 851–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, J.H.; Krantzberg, G.; Austin, J.C.; McIntyre, P. (Eds.) Great Lakes Revival: How Restoring Polluted Waters Leads to Rebirth of Great Lakes Communities; International Association for Great Lakes Research: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Illinois Environmental Protection Agency Waukegan Harbor Remedal Action Plan Stage III. 1998. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2013-12/documents/waukegan_harbor_rap_final_stage_iii_report_1999.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2020).

- Wernstedt, K.; Hersh, R. Through a Lens Darkly—Superfund Spectacles on Public Participation at Brownfield Sites. RISK Health Saf. Environ. 1998, 9, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros, E.; van der Zwet, A. Sustainable and integrated urban planning and governance in metropolitan and medium-sized cities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupp, G.; Zingraff-hamed, A.; Huang, J.J.; Oen, A.; Pauleit, S. Living Labs—A Concept for Co-Designing Nature-Base Solutions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Celata, F.; Coletti, R. Enabling and disabling policy environments for community-led sustainability transitions. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2019, 19, 983–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulleberg, I. The Role and Impact of NGOs in Capacity Development: From Replacing the State to Reinvigorating Education; International Institute For Educational Planning UNESCO: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).