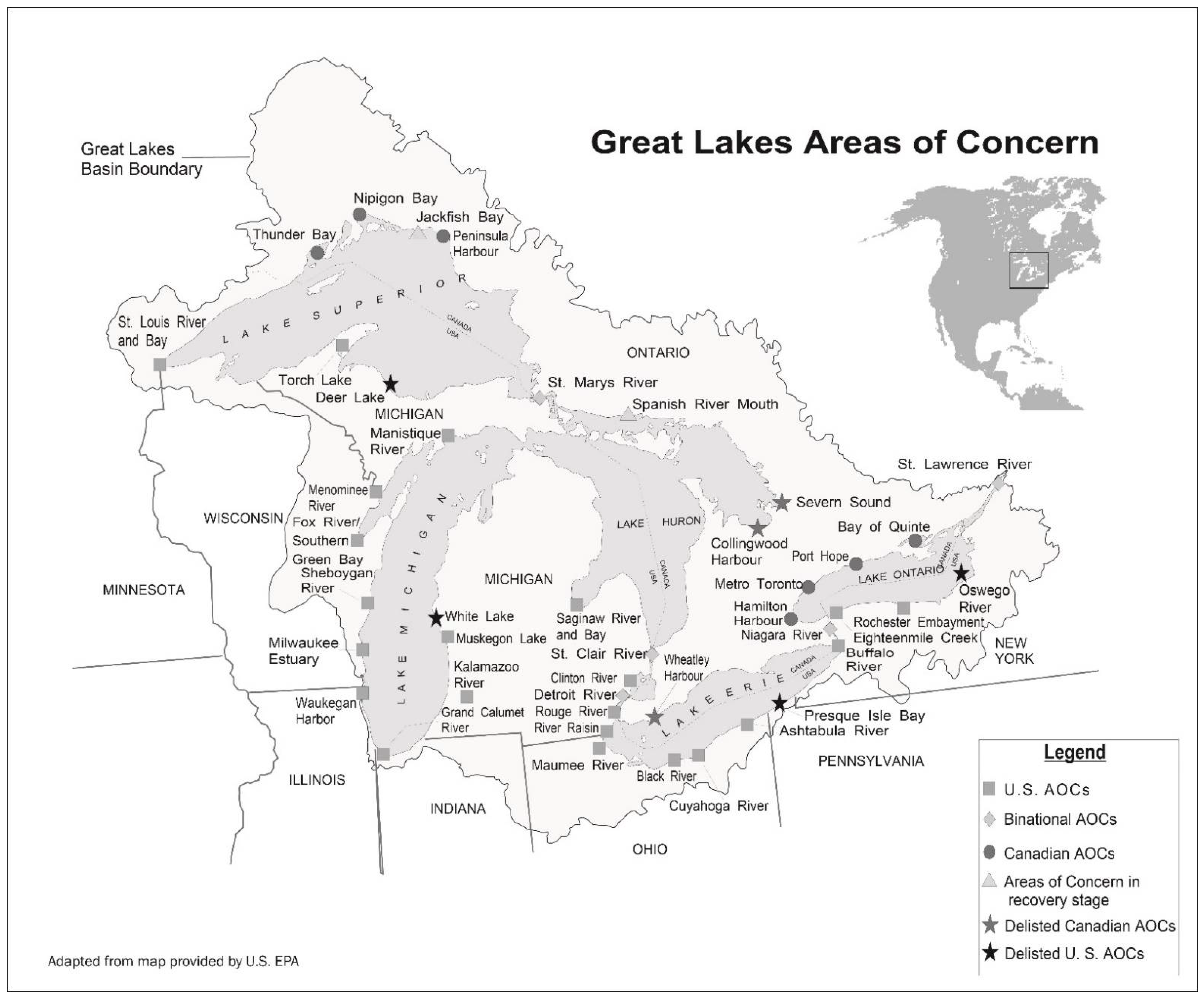

Evolving Institutional Arrangements for Use of an Ecosystem Approach in Restoring Great Lakes Areas of Concern

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- How many AOC institutional structures changed over time and how?

- Who are the typical actors involved in RAPs and what are their roles? How has this changed over time?

- Has the RAP process led to the emergence of new institutions with foci specific or tangential to the RAP?

- From 1985 to present, how many AOCs have established a nonprofit organization?

- How many AOC institutional structures reference life after delisting or sustainability?

- How were pre-existing institutions modified to accommodate the RAP and stakeholder needs?

- How have the roles of institutions and relation among institutions changed over time to address new challenges and needs?

- Does the AOC fall within the jurisdiction of any regulatory cleanup programs (e.g., Superfund, enforcement actions, Resource Conservation and Recovery Act) and, if so, how has this affected RAP institutional structure and function?

3. Results

3.1. Growing Involvement of Local Organizations in RAPs

3.2. Enhanced Institutional Mechanisms for Connecting RAPs to Their Watersheds

3.3. Expansion of Strategic Partnerships

3.4. Increasing Focus on the Future

4. Discussion

4.1. Growing Presence of Integrative Organizations

4.1.1. Integrative Organizations Increase Public Participation

4.1.2. Increasing Public Involvement and the Resulting Increase of Local Ownership and Capacity

4.1.3. Organizations as Institutional Mechanisms for Connecting RAPs to Their Watersheds

4.2. Strategic Collaborations and Partnerships

Partnering with Scientific Institutions Has Strengthened Science-Policy-Management Linkages and Can Cultivate Local Scientific Capacity

4.3. Promoting Sustainability and Fostering a Stewardship Ethic

4.4. Factors Related to Static Institutional Arrangements

4.5. Comparison with Other Experiences throughout the World

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hartig, J.H.; Vallentyne, J.R. Use of ecosystem approach to restore degraded areas of the Great Lakes. J. Hum. Environ. Res. Manag. 1989, 18, 423–428. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie, S.H. Toward integrated resource management: Lessons about the ecosystem approach from the Laurentian Great Lakes. Environ. Manag. 1997, 21, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Governments of Canada; United States of America. Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement; Governments of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada; United States of America: Washington, DC, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, K.; Nabatchi, T.; Balogh, S. An integrative framework for collaborative governance. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2012, 22, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodin, Ö. Collaborative environmental governance: Achieving collective action in social-ecological systems. Science 2017, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetoo, S.; Thorn, A.; Friedman, K.; Gosman, S.; Krantzberg, G. Governance and geopolitics as drivers of change in the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence basin. J. Great Lakes Res. 2015, 41, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingraff-Hamed, A.; Schröter, B.; Schaub, S.; Lepenies, R.; Stein, U.; Hüesker, F.; Meyer, C.; Schleyer, C.; Schmeier, S.; Pusch, M.T. Perception of bottlenecks in the implementation of the european water framework directive. Water Altern. 2020, 13, 458–483. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. A General Framework for Analyzing Sustainability of Social-Ecological System. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, G. Trajedy of the Commons. Science 1968, 162, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar]

- Great Lakes Water Quality Board. Report on Great Lakes Water Quality; International Joint Commission: Windsor, ON, Canada, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig, J.H.; Krantzberg, G.; Alsip, P. Thirty-five years of restoring Great Lakes Areas of Concern: Gradual progress, hopeful future. J. Great Lakes Res. 2020, 46, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, J.H.; Law, N. Institutional frameworks to direct development and implementation of great lakes remedial action plans. Environ. Manag. 1994, 18, 10–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krantzberg, G. Revisiting governance principles for effective Remedial Action Plan implementation and capacity building. Aquat. Ecosyst. Health Manag. 2018, 21, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holifield, R.; Williams, K.C. Recruiting, integrating, and sustaining stakeholder participation in environmental management: A case study from the Great Lakes Areas of Concern. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 230, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellogg, W.A. Adopting an ecosystem approach: Local variability in remedial action planning. Soc. Nat. Resour. 1998, 11, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zingraff-Hamed, A.; Hüesker, F.; Lupp, G.; Begg, C.; Huang, J.; Oen, A.; Vojinovic, Z.; Kuhlicke, C.; Pauleit, S. Stakeholder mapping to co-create nature-based solutions: Who is on board? Sustainability 2020, 12, 8625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landre, B.K.; Knuth, B.A. The role of agency goals and local context in great lakes water resources public involvement programs. Environ. Manag. 1993, 17, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manno, J. Great Lakes Water Quality Board Position Statement on the Future of Great Lakes Remedial Action Plans September 1996. J. Great Lakes Res. 1997, 23, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Violette, N. A Comparison of Great Lakes Remedial Action Plans and St. Lawrence River Restoration Plans. J. Great Lakes Res. 1993, 19, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, J.H.; Krantzberg, G.; Munawar, M.; Doss, M.; Child, M.; Kalinauskas, R.; Richman, L.; Blair, C. Achievements and lessons learned from the 32-year old Canada-U.S. effort to restore Impaired Beneficial Uses in Great Lakes Areas of Concern. Aquat. Ecosyst. Health Manag. 2018, 21, 506–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondolleck, J.M.; Yaffee, S.L. Marine Ecosystem-Based Management in Practice: Different Pathways, Common Lessons; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gurtner-Zimmermann, A. Analysis of Lower Green Bay and Fox River, Collingwood Harbour, Spanish Harbour, and the Metro Toronto and Region Remedial Action Plan (RAP) processes. Environ. Manag. 1996, 20, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelia, A. Great Lakes Areas of Concern: Life after Delisting an Investigation Conducted at the International Joint Commission Great Lakes Regional Office; International Joint Commission: Windsor, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Niagara River Restoration Council. Niagara River Remedial Action Plan Stage 2 Report; Ministry of Environment and Energy: Hamilton, ON, Canada, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ritcey, A.L. The Future of the St. Lawrence River at Cornwall, Ontario Post-Remedial Action Plan (RAP) Navigating Toward Sustainability. Master’s Thesis, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Muskegon Lake Watershed Partnership. Muskegon Lake Action Plan; Muskegon Lake Watershed Partnership: Muskegon, MI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- The History of Buffalo Niagara Waterkeeper. Available online: https://bnwaterkeeper.org/history/ (accessed on 5 October 2020).

- Partnership for Saginaw Bay Watershed Operations Manual. 2015. Available online: http://psbw.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/PSBWOperationsManual_wAppendices.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2020).

- Finger Lakes—Lake Ontario Watershed Protection Alliance. 2012 Lake Ontario Watershed Basin Forum: Community Visioning Workshop Series Summary; Finger Lakes—Lake Ontario Watershed Protection Alliance: Fulton, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe County Department of Health. Rochester Embayment Remedial Action Plan: Stage 2; Monroe County Department of Planning and Development: Rochester, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Krantzberg, G.; Rich, M. Life after delisting: The Collingwood Harbour story. Aquat. Ecosyst. Health Manag. 2018, 21, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.C. Relationships, Knowledge, and Resilience: A Comparative Study of Stakeholder Participation in Great Lakes Areas of Concern. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2015; p. 177. [Google Scholar]

- Krantzberg, G. Sustaining the gains made in ecological restoration: Case study Collingwood Harbour, Ontario. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2006, 8, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeemering, E.S. Comparing Governance and Local Engagement in the St. Marys River Area of Concern. Am. Rev. Can. Stud. 2018, 48, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beierle, T.C.; Konisky, D.M. What are we gaining from stakeholder involvement? Observations from environmental planning in the Great Lakes. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2001, 19, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council. New Strategies for America’s Watersheds; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ridgway, J.; Cave, K.; DeMaria, A.; O’Meara, J.; Hartig, J.H. The Rouge River Area of Concern-A multi-year, multi-level successful approach to restoration of Impaired Beneficial Uses. Aquat. Ecosyst. Health Manag. 2018, 21, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, J.H.; Zarull, M.A.; Law, N.L. An ecosystem approach to Great Lakes management: Practical steps. J. Great Lakes Res. 1998, 24, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krantzberg, G. Examining governance principles that enable RAP implementation and sustainable outcomes. In Ecosystem-Based Management of Laurentian Great Lakes Areas of Concern: Three Decades of U.S.-Canadian Cleanup and Recovery; Hartig, J.H., Munawar, M., Eds.; Ecovision World Monograph Series; Aquatic Ecosystem Health and Management: Burlington, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Child, M.; Read, J.; Ridal, J.; Twiss, M. Symmetry and solitude: Status and lessons learned from binational Areas of Concern. Aquat. Ecosyst. Health Manag. 2018, 21, 478–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.; Hoffman, J.; Bolgrien, D.; Angradi, T.; Carlson, J.; Clarke, R.; Fulton, A.; Timm-Bijold, H.; MacGregor, M.; Trebitz, A. How the Community Value of Ecosystem Goods and Services Empowers Communities to Impact the Outcomes of Remediation, Restoration, and Revitalization Projects; US Environmental Protection Agency: Duluth, MN, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Angradi, T.R.; Williams, K.C.; Hoffman, J.C.; Bolgrien, D.W. Goals, beneficiaries, and indicators of waterfront revitalization in Great Lakes Areas of Concern and coastal communities Goals, beneficiaries, and indicators of waterfront revitalization in Great Lakes Areas of Concern and coastal communities. J. Great Lakes Res. 2019, 45, 851–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, J.H.; Krantzberg, G.; Austin, J.C.; McIntyre, P. (Eds.) Great Lakes Revival: How Restoring Polluted Waters Leads to Rebirth of Great Lakes Communities; International Association for Great Lakes Research: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Illinois Environmental Protection Agency Waukegan Harbor Remedal Action Plan Stage III. 1998. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2013-12/documents/waukegan_harbor_rap_final_stage_iii_report_1999.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2020).

- Wernstedt, K.; Hersh, R. Through a Lens Darkly—Superfund Spectacles on Public Participation at Brownfield Sites. RISK Health Saf. Environ. 1998, 9, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros, E.; van der Zwet, A. Sustainable and integrated urban planning and governance in metropolitan and medium-sized cities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupp, G.; Zingraff-hamed, A.; Huang, J.J.; Oen, A.; Pauleit, S. Living Labs—A Concept for Co-Designing Nature-Base Solutions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Celata, F.; Coletti, R. Enabling and disabling policy environments for community-led sustainability transitions. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2019, 19, 983–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulleberg, I. The Role and Impact of NGOs in Capacity Development: From Replacing the State to Reinvigorating Education; International Institute For Educational Planning UNESCO: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

| Key Characteristic | Purpose or Function |

|---|---|

| Fosters integration through a broad-based institutional structure | Engage stakeholders who impact or are impacted by pollution in the AOC, ensure meaningful involvement for use restoration, and foster integration across disciplines and among water, land, air, municipalities, industries, etc. |

| Promotes a watershed focus | Ensure planning and management that account for watershed boundaries |

| Encourages local ownership of RAP process | Structure the RAP process to create a sense of ownership by participants, who were the very businesses, state and local agencies, and citizens who had to help implement remedial and preventive actions; engage local leaders; recruit champions |

| Establish compelling vision and clear goals | Establish a vision that can be carried in the hearts and minds of all stakeholders and measurable targets to focus actions |

| Builds collaboration, partnerships, and capacity | Build institutional capacity and establish or leverage partnerships for cleanup and restoration, and foster collaborative problem-solving and financing |

| Connects to scientific organizations to understand problems and causes, and support scientifically-sound decision-making | Strengthen science-policy-management linkages and practice adaptive management |

| Celebrates a record of success for the AOC, including benefits | Showcase restoration progress publicly to build momentum and maintain community interest and buy-in for revitalization of their ecosystem |

| Emphasizes sustainability planning for life after delisting as an AOC | Enact remedial and preventive actions to advance broader social and economic revitalization in waterfront areas and foster a stewardship ethic |

| Area of Concern | Evolution of AOC/RAP Institutional Structures |

|---|---|

| Peninsula Harbour (Ontario) | The Public Advisory Committee (PAC) was established in 1989 to facilitate public input in RAP development and implementation. The Lake Superior Programs Office was formed in 1991 by Environment Canada, the Canada Department of Fisheries of Oceans, the Ministry of Environment and Energy and the Ministry of Natural Resources as a unique, one-window approach to deliver projects recommended by PACs for the four northshore AOCs (i.e., Thunder Bay, Nipigon Bay, Jackfish Bay, and Peninsula Harbour). The RAP is now facilitated by Lakehead University with supervision from several provincial and federal agencies. The PAC disbanded after they completed their original objectives of evaluating BUIs and developing water use goals for the AOC that could be used as community-based guidelines for the RAP. However, public involvement in the AOC continued through the development and implementation of the contaminated sediment management plan. In 2008, the Peninsula Harbour Community Liaison Committee (CLC) was formed to facilitate public involvement in the sediment management plan and other RAP discussions. The CLC, which is composed of several former PAC members, provides input to the RAP and assists with information sharing within the community of Marathon and the Ojibways of the Pic River First Nation. InfoSuperior was created in the 2000s as a research and information network for Lake Superior, including RAPs, focused on community engagement, stakeholder communication, and assisting with restoration projects. EcoSuperior Environmental Programs was established in 1985 as a nonprofit organization for environmental stewardship in Northwestern Ontario and the Lake Superior Basin through engagement, education, collaboration, action, and leadership. |

| Jackfish Bay (Ontario) | The PAC was established in 1989 to facilitate public input in RAP development and implementation. The Lake Superior Programs Office was formed in 1991 by Environment Canada, the Canada Department of Fisheries of Oceans, the Ministry of Environment and Energy and the Ministry of Natural Resources as a unique, one-window approach to deliver projects recommended by PACs for Thunder Bay, Nipigon Bay, Jackfish Bay, and Peninsula Harbour AOCs. The RAP is now facilitated by Lakehead University with supervision from several provincial and federal agencies. In 2008, the Public Area in Recovery Review Committee (PARRC) was established to continue the role of the original PAC as the AOC transitioned to Area in of Concern in Recovery (AiR) status. The PARRC has helped outline a plan for guiding the AiR through recovery to delisting and has been critical to defining what AiR status means. Among other recommendations, the PARRC has highlighted the importance of ensuring ongoing community engagement and education during the AiR phase. InfoSuperior serves as an important mechanism for facilitation and information sharing. EcoSuperior Environmental Programs is a nonprofit organization established in 1985 for regional environmental stewardship through engagement, education, collaboration, action, and leadership. |

| Nipigon Bay (Ontario) | The PAC was established in 1989 to facilitate public input in RAP development and implementation. The Lake Superior Programs Office was formed in 1991 by Environment Canada, the Canada Department of Fisheries of Oceans, the Ministry of Environment and Energy and the Ministry of Natural Resources as a unique, one-window approach to deliver projects recommended by PACs for Thunder Bay, Nipigon Bay, Jackfish Bay, and Peninsula Harbour AOCs. InfoSuperior serves as an important mechanism for facilitation and information sharing. EcoSuperior Environmental Programs is a nonprofit organization established in 1985 for regional environmental stewardship through engagement, education, collaboration, action, and leadership. |

| Thunder Bay (Ontario) | The PAC was established in 1989 to facilitate public input in RAP development and implementation. The Lake Superior Programs Office was formed in 1991 by Environment Canada, the Canada Department of Fisheries of Oceans, the Ministry of Environment and Energy and the Ministry of Natural Resources as a unique, one-window approach to deliver projects recommended by PACs for Thunder Bay, Nipigon Bay, Jackfish Bay, and Peninsula Harbour AOCs. The RAP is now facilitated by Lakehead University with supervision from several provincial and federal agencies. InfoSuperior serves as an important mechanism for facilitation and information sharing. EcoSuperior Environmental Programs is a nonprofit organization established in 1985 for regional environmental stewardship through engagement, education, collaboration, action, and leadership. |

| St. Louis River (Minnesota and Wisconsin) | A Citizen Advisory Committee (CAC) was established in 1985 to ensure public input for the RAP and to help foster use of an ecosystem approach. In 1996, the CAC was incorporated as a nonprofit organization called the St. Louis River Alliance (SLRA). SLRA works to oversee activities and practices that are helping to restore, protect, and enhance the St. Louis River. |

| Torch Lake (Michigan) | A Public Action Council was established in 1997 and within one year became incorporated as a nonprofit organization. The Council advised on restoration and has successfully raised funds from local sources to defray logistical costs. Restoration benefited from the Superfund Program, including U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), and Michigan Departments of Environmental Quality (DEQ) and Natural Resources. U.S. EPA entered into an interagency agreement with NRCS that allowed it to leverage the NRCS’s soil erosion/bank stabilization expertise, site familiarity, and existing rapport with the community. |

| Deer Lake and Carp River and Creek (Michigan) | A PAC was established in 1987 to ensure public input on RAP development and implementation. The Council worked with the State of Michigan to achieve delisting as an AOC. The City of Ispeming has committed to long-term stewardship of Partridge Creek because it owns the property. |

| Manistique River and Harbor (Michigan) | Public meetings were held in 1986 and 1987. In 1993, a Public Advisory Council was established, and U.S. EPA started engaging potentially responsible parties (Manistique Papers and Edison Sault Electric Company) for remediation of PCB-contaminated sediment. Early remediation of contaminated sediments was led by the Superfund program. The RAP process was primarily a government-led process, with the federal government leading remediation of contaminated sediment, the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) serving as the RAP coordinator, and City of Manistique’s wastewater superintendent serving as the Council chair. The Council adopted delisting guidelines in 2005 and a committee was established to address habitat under the Council. The City of Manistique has taken the lead on championing the Manistique River as a tourist destination and built a boardwalk to reconnect people to this waterway. |

| Lower Menominee River (Wisconsin and Michigan) | The CAC was formed in 1988 as a means of incorporating stakeholder feedback into the RAP and to serve as ambassadors on AOC issues for the Marinette and Menominee communities. The CAC developed governing bylaws in June of 2011 to ensure the committee’s long-term viability and balanced community representation. CAC members also played a critical role in community engagement and outreach. Representatives from the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) and Michigan MDEQ, and each municipality, serve on the technical advisory committee (TAC), along with representatives from academia, the private sector, and utilities. |

| Fox River and Southern Green Bay (Wisconsin) | Wisconsin DNR established a CAC in 1986 for public involvement in the RAP and to ensure use of an ecosystem approach. Four TACs supported RAP development. The original CAC was disbanded in 1988 and replaced with an Implementation Committee. University of Wisconsin-Extension helped facilitate education and outreach. The Green Bay community’s strong sense of place is reflected in the institutional arrangement surrounding the RAP. In reference to the community’s football team, the CAC adopted the name “The Clean Bay Backers” as a means of evoking loyalty to their water resources much like the community’s loyalty to their football team. The CAC has been active in community engagement, including an annual “Bringing Back the Bay Tour” in which they take local officials and community leaders on an area tour and inform them on ecosystem problems. The CAC includes individuals from the general public, municipalities, academia, and nonprofit organizations, including Ducks Unlimited and the Fox-Wolf Watershed Alliance. |

| Sheboygan River (Wisconsin) | In 1984, the Sheboygan County Water Quality Task Force was created by citizens concerned about pollution in the AOC. This Task Force was used to ensure public input in RAP development, with support from the Sheboygan River and Harbor TAC and a Wisconsin DNR Workgroup for river cleanup. The Task Force eventually evolved into a CAC. The University of Wisconsin Extension helped with public education and outreach and helped facilitate the CAC and TAC. Sheboygan River Basin Partnership (SRBP) was created in 1998 as a nonprofit alliance of conservation/environmental groups in the watershed. SRBP’s mission is to cultivate partnerships to raise public awareness, increase participation in stewardship, and promote sound environmental decision making for the river. Water Action Volunteers, a collaborative citizen program under the Wisconsin DNR and University of Wisconsin Extension, performed citizen science to assess ecosystem health. Waterfront revitalization is now being championed by the City of Sheboygan and the Sheboygan County Economic Development Corporation. |

| Milwaukee River Estuary (Wisconsin) | Starting in 1987, Wisconsin DNR and a TAC began developing the RAP, with input from a CAC and Citizen Education and Participation Subcommittee. The CAC provided input on RAP goals, established a long-term vision, advised on RAP implementation, and served as a unifying entity for all AOC stakeholders. By the mid-1990s the TAC and the CAC stopped meeting, but RAP development continued through a steering committee. However, the RAP lacked a true stakeholder coalition. In 2012, Wisconsin DNR and University of Wisconsin-Extension established a new CAC with broader participation. University of Wisconsin-Extension facilitated this process with grant support from U.S. EPA. Today, the CAC is comprised of public, private, and nonprofit representatives to provide two-way communication between AOC staff and member organizations. Milwaukee Riverkeeper is a nonprofit organization focused on monitoring water quality and providing science-based advocacy for the Milwaukee River. Water Action Volunteers, a collaborative citizen program of Wisconsin DNR and University of Wisconsin Extension, performs citizen science to assess ecosystem health. |

| Waukegan Harbor (Illinois) | In 1990, a Citizens’ Advisory Group (CAG) was established to assist Illinois Environmental Protection Agency in RAP development and implementation. It was structured to include corporate, governmental, shipping, environmental, and public representatives. The CAG’s institutional structure was broad and diverse early on with 26 member-organizations in 1990 and was increased to 34 member-organizations in 2019. The CAG has been instrumental in obtaining cooperation from local parties regarding investigations, gaining access from private businesses, and securing federal grant money. The CAG also promotes redevelopment and stewardship of the lakefront and works with others to protect Waukegan Harbor as a local and regional asset. |

| Grand Calumet River (Indiana) | Citizens Advisory for the Remediation of the Environment (CARE) was established in 1987 to advise Indiana Department of Environmental Management on restoration of uses in the AOC. The committee is comprised of members of local organizations, industries, academia, and agencies dedicated to improving the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the area’s ecosystem. CARE also educates the public about AOC progress. The Grand Calumet River Restoration Fund (GCRRF) was established through a settlement with industrial users in the Sanitary District of Hammond. Its purpose is to address and correct environmental contamination in the AOC, including the cleanup of contaminated sediment and the remediation of natural resource damages. GCRRF was established by a memorandum of understanding between state and federal partners and is authorized to conduct studies and make decisions for the management and administration of funds. Chicago Wilderness Alliance is sponsored by the Friends of the Forest Preserves, which is a nonprofit organization formed in 1996. It has more than 260 public and private partners involved in restoring, protecting, and connecting 728,400 ha, including portions of the Grand Calumet River through conservation and sustainable development practices. |

| Kalamazoo River (Michigan) | In 1987, the Michigan DNR developed the RAP with funding from the State of Michigan. The City of Kalamazoo formed a coalition of stakeholders and agency representatives known as the Kalamazoo River Basin Strategy Committee (Basin Committee). The Basin Committee helped implement and coordinate the RAP and a fisheries management plan. In 1993, the Kalamazoo River Public Advisory Council was established to fill this institutional niche. In 1998, the Council’s function was assumed by the nonprofit organization Kalamazoo River Watershed Council (KRWC) that has established broader goals that go beyond delisting. In 2001, the Kalamazoo River/Lake Allegan Watershed Phosphorus Reduction Committee was established to complement the PAC and oversee coordinated efforts to establish Total Maximum Daily Loads to comprehensively address nonpoint sources. |

| Muskegon Lake (Michigan) | In 1985, a Public Advisory Council was established to ensure public participation in the RAP and help implement an ecosystem approach. In the early 1990s the Muskegon Lake Watershed Partnership was established as a community-based, volunteer partnership organization to support grassroots, local, state, regional, federal, and international programs to restore Muskegon Lake and the Great Lakes. This Partnership has developed a Muskegon Lake Ecosystem Action Plan to facilitate the continuation of coordinated, natural resources stewardship of Muskegon Lake and Lower Muskegon River Watershed from 2018 through 2025. |

| White Lake (Michigan) | The RAP was developed by state and federal agencies, local government officials, stakeholder groups, and independent citizens. In 1992, the Muskegon office of the Lake Michigan Federation (now the Alliance for the Great Lakes) obtained a grant that officially established a Public Advisory Council. The Lake Michigan Federation provided administrative support to the Council in the early years, but later transferred that role to the Muskegon Conservation District (MCD) who served as a fiduciary and provided technical support to the PAC through delisting. U.S. EPA provided funds to support a position for three years at the MCD to set up an environmental stewardship program. This program focuses on community partnerships for long-term conservation, preservation, and restoration of White Lake. MCD has helped foster use of an ecosystem approach and achieve local ownership. White Lake was delisted as an AOC in 2014, but the PAC has remained active and has developed a strategic plan for 2015–2018 that established the White Lake Environmental Network—a network of stakeholders focused on sustaining momentum for revitalization. |

| Saginaw River and Bay (Michigan) | In 1987, the Saginaw Basin Natural Resources Steering Committee was established to provide public input on the RAP. Today, the board of directors of the Partnership for the Saginaw Bay Watershed (Partnership) serves as a Public Advisory Council. The Partnership is a nonprofit organization that is comprised of public and nongovernmental stakeholders across the Saginaw River Basin. This Partnership merged the Saginaw Basin Alliance and the Saginaw Bay Watershed Council in 1995, and facilitates intergovernmental coordination and public involvement, provides guidance on public policy, and assists with restoration projects in the basin. The Partnership is structured and functions as a collaborative for watershed management. The Saginaw Bay Watershed Initiative Network (WIN) is a community-based, voluntary initiative that connects people, resources, organizations, and programs. Implementation of the RAP has advanced with funding acquired through WIN with financial support from 11 foundations. |

| Collingwood Harbour (Ontario) | The Public Advisory Committee (PAC) was established in 1987 to ensure public input in RAP development and foster use of an ecosystem approach. The PAC was incorporated in 1993 with an office located in downtown Collingwood. A storefront called The Environment Network of Collingwood opened for the RAP to serve as a central location for RAP activities. Several years later, the name was changed to The Environment Network. The Network went on to develop a strategic plan called the Greening of Collingwood that championed pollution prevention for residents, businesses, and industries. To this day the Network operates as a cooperative, providing people with opportunities for work and a place for people to learn how they can operate their business or home in an ecologically, socially, and economically sustainable manner. |

| Severn Sound (Ontario) | The RAP was initiated in the mid-1980s through a partnership agreement between the federal and provincial governments and municipalities in the Severn Sound area. The partnership became the Severn Sound Environmental Association (SSEA)—a Joint Municipal Services Board Ontario Municipal Act, Section 202, representing the 10 municipalities in the Severn Sound area. SSEA played a key role in sewage treatment plant upgrades, farm pollution control projects, stormwater treatment studies, tree planting, shoreline restoration and ecosystem monitoring, and public outreach on environmental issues. SSEA helped provide community-based and cost-effective environmental management for the AOC, which helped sustain momentum and achieve delisting. Following delisting, creative local partnership agreements and financing were arranged to continue long-term implementation and to meet emerging environmental and sustainability challenges. |

| Spanish River (Ontario) | A PAC was established in the late 1980s to assist with RAP development and promote use of an ecosystem approach. Early on the effectiveness of the PAC was hampered by poor working relationships resulting from disputes and disagreements among stakeholders [22]. These issues were addressed, and a coordinated approach was achieved among the federal and provincial governments and the PAC that led to implementation of all recommended actions and being designated as an “AOC in recovery” in 1999. In 1994, a group of concerned citizens formed the nonprofit organization called the Friends of the Spanish River (FOSR). FOSR was active in the RAP and worked closely with all stakeholders on community engagement, RAP implementation, and public education. FOSR disbanded in 2013, having achieved their mandate. |

| Clinton River (Michigan) | A Public Advisory Council was established in 1986 and worked closely with stakeholders to ensure use of an ecosystem approach in the RAP process. The Council served as an integrative organization among stakeholders, delineated specific remedial actions to be implemented by various entities through a “partnership agreement”, and tracked progress. The Clinton River Watershed Council (CRWC), a nonprofit organization established in 1972, has provided grassroots coordination from the outset of the RAP process. CRWC has coordinated local restoration efforts and provided administrative and technical support to the Council. CRWC has also helped foster a “sense of place” and local ownership through engaging and educating the public on watershed issues and leveraging the river’s “placemaking” potential to support community development. |

| Rouge River (Michigan) | In 1985, the Rouge River Basin Committee was established to develop and implement the RAP with representation for all 48 watershed communities. In 1986, the Friends of the Rouge was established to raise awareness and promote cleanup of the Rouge River. In 1992, the representatives of the Basin Committee were reorganized into the Rouge RAP Advisory Council and in 1993 the Rouge River National Wet Weather Demonstration Project was established with over $350 million to help implement CSO controls and innovative storm water management techniques called for in the RAP. In 2003, the Alliance of Rouge Communities was founded to help implement comprehensive monitoring, facilitate communication among watershed stakeholders, and coordinate sub-watershed planning to implement stormwater plans. |

| River Raisin (Michigan) | Since 1985, Michigan DNR and DEQ have worked with a Public Advisory Council to ensure public involvement and local ownership of the RAP, and have coordinated with the River Raisin Watershed Council, the City of Monroe, and many others. In 2006, the city established the Commission on the Environment and Water Quality and nested the River Raisin Public Advisory Council under this commission, ensuring a long-term commitment to both restoration and life after delisting within the city’s governmental structure. The River Raisin Institute was established by the Immaculate Heart of Mary (IHM) Sisters to revitalize and preserve sustainable ecosystems, including the River Raisin AOC. The Institute, the River Raisin Watershed Council, and Public Advisory Council collaborate on watershed management and sustainability. |

| Maumee River (Ohio) | The first public meeting for the RAP was convened by Ohio Environmental Protection Agency in 1987. Out of this initial meeting came a RAP Advisory Committee made up of a broad cross section of business, government, community, and nongovernmental stakeholders. Key assistance was provided by Toledo Metropolitan Area Council of Governments. Later the name was changed to the Maumee River AOC Advisory Committee. A critical partner in the success of the Maumee RAP has been the Duck and Otter Creeks Partnership formed in 1999. The Partnership worked very closely with the Maumee RAP to develop the Stage II RAP for the Maumee AOC. |

| Black River (Ohio) | In the early 1990s, a committee called the Black River RAP was established as a unique community-based public/private initiative for restoration of impaired uses. Its motto was “Our River, Our Responsibility”. Based on guidance from the U.S. EPA, the name was changed to the Black River AOC Advisory Committee in 2014. The Black River Facilitating Organization (BRFO) identifies and focuses on priorities within the Black River AOC, supports agencies involved in restoration and remediation, facilitates public outreach, and promotes watershed education. The BRFO raises funds, manages programs and projects, and coordinates and assists the Advisory Committee. During early RAP development, Seventh Generation was established as a nonprofit organization to promote environmental education and help people see how their decisions would impact the next seven generations, consistent with Iroquois Nation beliefs. One of their accomplishments before closing was the creation of the Black River Environmental Center. |

| Cuyahoga River (Ohio) | In 1988, the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) appointed a 33-member planning committee to develop the Cuyahoga River RAP. This organization, called the Cuyahoga River RAP Coordinating Committee was made up of a balanced representation of stakeholders in the planning and implementation process. In 1989, the nonprofit Cuyahoga River Community Planning Organization (later renamed Cuyahoga River Restoration) was created to support the RAP’s activities. Today, Cuyahoga River Restoration continues to support efforts to restore, revitalize, and protect the Cuyahoga River watershed and nearshore are of Lake Erie. In 2012, Flats Forward was created as nonprofit organization for community and economic development. |

| Ashtabula River (Ohio) | In 1988, a 30-member RAP Advisory Council was established by Ohio Environmental Protection Agency to ensure public participation in the RAP using an ecosystem approach. In 1994, a group of federal, state, local, and private entities came together to form the Ashtabula River Partnership (ARP) to foster cooperative approach to remediation of contaminated sediments within the AOC. The ARP was an important institutional mechanism that played a critical role in project success. This partnership pooled technical resources, worked together to build a consensus approach to remediation of contaminated sediment that plagued the AOC for the better part of four decades, and utilized a mix of public and private funding sources to address the problem. The ARP also served as a forum for coordination among the key players, meaningful engagement of the impacted community in problem resolution, and streamlined technical discussions and permitting processes. |

| Presque Isle Bay (Pennsylvania) | A Public Advisory Committee and Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) were the driving forces behind the RAP process. While the Committee officially formed in 1991, the foundation of stakeholder involvement had been present before AOC designation. The concerned citizens that advocated for Presque Isle Bay to be designated an AOC in 1991 joined this Committee. Joining the Committee was an established delegation created by the Mayor of Erie and Erie County Executive called the Erie Harbor Improvement Council. A second evolution of the Committee occurred following the delisting of the AOC in 2013. The Committee then joined the Pennsylvania Great Lakes Lake Erie Environmental Forum (Forum), which was formed by the Pennsylvania DEP with the help of Pennsylvania Sea Grant to engage and inform the public. The Forum then expanded its focus to include the entire watershed. Supporting the Forum and environmental stewardship are Pennsylvania Sea Grant, Pennsylvania DEP, Environment Erie, Erie County Conservation District, Pennsylvania Lake Erie Watershed Association, and the Regional Science Consortium at Presque Isle [23]. Waterfront revitalization is now being championed by the City of Erie, the Port Authority, and Erie County. |

| Wheatley Harbour (Ontario) | Lacking a formal PAC, the Wheatley Harbour RAP was developed through a multi-institutional partnership, including Environment and Climate Change Canada, several provincial agencies, the Essex Region Conservation Authority, and the Essex County Stewardship Network. The community was engaged on an “as needed” basis throughout the RAP process. After delisting in 2010, monitoring and maintenance activities have been conducted under the auspices of on-going, governmental programs, such as provincial fish contaminant monitoring, Lake Erie’s Lakewide Action and Management Plan, and federal programs [23]. |

| Buffalo River (New York) | From 1985 through the early 2000s, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) served as the RAP coordinator, with public participation and input from a Remedial Advisory Committee. In 2003, the Buffalo Niagara Waterkeeper was the first nonprofit organization in the Great Lakes selected to re-energize the RAP process, coordinate implementation, and catalyze further progress, ensuring life after delisting. Since 2012, this unique partnership has raised $56.5 million (U.S.) for contaminated sediment remediation and $25 million (U.S.) for habitat rehabilitation. |

| Eighteen Mile Creek (New York) | The RAP was developed by New York State DEC, in cooperation with the Remedial Advisory Committee, which was comprised of local officials, landowners, and stakeholders selected by the New York State DEC commissioner. In 2005, the Niagara County Soil & Water Conservation District (NCSWCD) took over as the lead agency for the RAP. The NCSWCD helped coordinate remedial actions among federal, state, and local partners and provides staff support to the Committee that provided input on RAP implementation and ensured public outreach. |

| Rochester Embayment (New York) | A comprehensive water quality management structure was in place in Monroe County prior to the onset of the RAP process and provided an existing institutional framework for the RAP. The RAP was written by and coordinated by the Water Quality Management Agency (WQMA) of the Monroe County Health Department. The Monroe County Water Quality Coordinating Committee (WQCC) and analogous committees in other counties provided technical expertise to the WQMA and coordinated task groups. The Water Quality Management Advisory Committee (WQMAC), in existence since 1979, was the primary mechanism for public input on the RAP. Regional organizations helped connect surrounding counties to the RAP process, while also connecting the RAP to larger watershed programs. Primary among these were the Water Resources Board (WRB), which is the governing body of the Finger Lakes–Lake Ontario Watershed Protection Alliance (FL-LOWPA). FL-LOWPA is an alliance of 24 New York counties in the Lake Ontario Basin and provides additional resources to the RAP and helps coordinate the RAP with other watershed, management programs that address local water priorities. The RAP formed the Water Education Collaborative (WEC) as a nonprofit organization and the Stormwater Coalition of Monroe County. WEC administers public education programs that support the RAP and water quality initiatives in the community. The Stormwater Coalition is an intermunicipal agreement with 29 institutions that work collaboratively to comply with Federal stormwater regulations to improve water quality. WEC and the Stormwater Coalition provide a foundation for stewardship and revitalization following future delisting as an AOC. |

| Oswego River (New York) | The New York State DEC formed a Citizen’s Advisory Committee in 1987 which was tasked it with providing public input on the RAP. The Committee was comprised of local residents, industrial representatives, outdoor enthusiasts, scientists, environmentalists, and local governmental representatives. In 1991, the Committee was replaced by a Remedial Advisory Committee (RAC), which had a similar composition as the Committee, but also aided the New York State DEC in RAP implementation. The RAC dissolved following delisting in 2006. Post-delisting momentum has been maintained by city and county governments [23], and the focus of environmental stewardship has expanded beyond the original AOC boundaries to focus on the larger watershed. This watershed focus is consistent with the earlier RAP’s approach that considered upstream remedial actions that affected use impairments within the AOC. |

| Bay of Quinte (Ontario) | In 1987, a PAC was established to facilitate public input on RAP development. Since 1997, implementation of recommended actions for the Bay of Quinte area has been facilitated by members of the Bay of Quinte Restoration Council, including representatives from the Lower Trent Region Conservation, Quinte Conservation, Environment and Climate Change Canada, Ontario Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Ontario Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte, local communities, and Canadian Forces Base Canada. |

| Port Hope (Ontario) | Port Hope is a unique situation because of legacy contamination with low-level radioactive waste materials from historical mining and refining operations between 1933 and 1953. Cleanup has been led by the Government of Canada and the Port Hope Area Initiative. Throughout the environmental assessment phase, there was extensive public consultation, and public engagement continues through a Citizen Liaison Group. |

| Toronto and Region (Ontario) | In 1987, Environment Canada and Ontario Ministry of the Environment established a PAC to facilitate public input in RAP development. Today, the Toronto and Region RAP is managed by representatives from Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC), the Ontario Ministry of the Environment, Conservation, and Parks (MECP), the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (MNRF), Toronto Water, and the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA). Since 2002, TRCA has led the administration of the RAP under an agreement with ECCC and the MECP. The RAP team works with many partners, including nonprofits organizations like Waterfront Toronto. |

| Hamilton Harbour (Ontario) | In 1985, a Hamilton Harbour stakeholder group was established to ensure public participation in the RAP and help implement an ecosystem approach. A scientific Writing Team made up of federal and provincial scientists and resource managers prepared RAP reports. The Writing Team reported their findings to the Stakeholder Group for input. No distinction was made between decision-making authority of the Stakeholder Group or the Writing Team; they worked by consensus. Upon completion of the Stage 2 RAP in 1992, the Stakeholder Group disbanded and defined two groups to take its place; the Bay Area Implementation Team (BAIT) and the Bay Area Restoration Council (BARC). BAIT includes all the agencies, institutions, and corporations who accepted the responsibility for implementing recommended remedial actions. BARC is an independent incorporated citizens group responsible for monitoring progress on the remedial actions and to educating and advocating for remedial actions. Neither BAIT nor BARC were identified as subordinate to the other. BAIT and BARC continue to work to clean up and restore Hamilton Harbour as a thriving, healthy, and accessible ecosystem. |

| St. Marys River (Michigan and Ontario) | A binational PAC (or BPAC) was established in 1988 with various stakeholder groups from the United States and Canada. The BPAC has been active in fostering partnerships with other community groups that focus on the restoration and protection of the St. Marys River ecosystem. Through these relationships, the BPAC identifies and prioritizes programs and projects that can help achieve the goals of RAP. A priority list of these projects has been incorporated into the Lake Superior Lakewide Action and Management Plan (LAMP). The BPAC operates out of an office at Lake Superior State University. The BPAC’s partnership with the University has increased the BPAC’s capacity by involving students in RAP-related activities such as maintaining the BPAC’s website and interactive map explorer for visualizing RAP progress. The BPAC also supported the creation of the nonprofit organization: Friends of the St. Marys River (FOSM). In addition to supporting the RAP, FOSM works to promote and protect the river’s value as a Canadian Heritage River, which was granted to it in 2000. Through the establishment of FOSM and the network of stewardship-focused stakeholder groups, the BPAC is fostering a culture of local involvement in environmental planning that should persist beyond delisting. In 2008, the St. Mary’s Water Quality Network was formed to promote public outreach efforts regarding the fish tumors impairment. |

| St. Clair River (Michigan and Ontario) | In 1988, a BPAC was established by U.S. EPA, Environment Canada, Michigan DNR, and Ontario Ministry of the Environment to advise and oversee a RAP team during the planning, adoption, and implementation. The BPAC serves as an interface between the public and the RAP team. RAP team members and BPAC members compose four task teams. Also, in 1988 two nonprofit organizations were formed under the name of Friends of the St. Clair River (FOSCR) to support BPAC efforts in Canada and the United States. FOSCR started as a fiduciary for BPAC, but over time evolved to foster public education and community engagement. Together, FOSCR and BPAC have made public education and community engagement a priority from the outset. In 2005, the Canadian Remedial Action Plan Implementation Committee was established to guide implementation of the remaining remedial actions on the Canadian side of the AOC. U.S. EPA and Michigan DEQ informally participate in this committee as needed. |

| Detroit River (Michigan) | A BPAC was established in 1987 at the onset of Stage 1 RAP development. It soon was paralyzed by lack of trust and ineffective governance and split apart into separate U.S. and Canadian public involvement processes. In 1991, the Detroit River Public Advisory Council (PAC) was established in the United States to facilitate public involvement in cleanup efforts. Also, in the early 1990s the Friends of the Detroit River were established as a nonprofit organization to enhance public involvement in the RAP. Today, the PAC continues to facilitate public participation in the RAP and assists with its implementation, under the direction of the Friends of the Detroit River. U.S. PAC members now periodically participate in Detroit River meetings in Canada. |

| Detroit River (Ontario) | A BPAC was established in 1987 for RAP development. With the dissolution of BPAC, the Detroit River Canadian Cleanup (DRCC) was established in Ontario in 1998 with federal and provincial funding. A RAP Coordinator works out of the Essex Region Conservation Authority office, provides support for RAP participants, and liaises with U.S. RAP participants on an ongoing basis. DRCC includes a local, provincial, and federal agency personnel who have RAP implementation responsibility, as well as private sector, academic, and nongovernmental partners. DRCC also has an active PAC that includes participants from Essex County Field Naturalists’ Club, Little River Enhancement Group, Citizens Environment Alliance, Unifor (formerly Canadian Auto Workers) and the Windsor and District Labour Council, among others. DRCC and PAC members periodically participate in Detroit River meetings in the U.S. |

| Niagara River (Ontario) | In 1988, a PAC was established by Environment Canada and Ontario Ministry of the Environment to ensure stakeholder participation in the RAP process and to foster use of an ecosystem approach. In 1998, it was incorporated as a nonprofit organization called the Niagara River Restoration Council (NRC). The NRC is based out of Welland, Ontario, but is active in the implementation on both sides of the river. The NRC has carried out habitat rehabilitation projects, including the construction of stream buffers and the removal of barriers to fish migration throughout the Niagara region. In 1999, the Niagara Peninsula Conservation Authority (NPCA) took an active leadership role and became the host organization for administering and coordinating the RAP with funding support from the federal and provincial government and continues today to fulfill these secretariat services. The NPCA has been an active participant in the RAP initiative since its inception in the late 1980s and has completed many remedial and preventive actions. Although there are separate RAPs for the Ontario side and the New York side, they are formally connected through an international advisory committee [24]. In addition, the Niagara River Toxics Management Plan is binational in scope and has been instrumental in reducing toxic substances’ loadings. |

| Niagara River (New York) | New York State DEC has served as the RAP coordinator since 1985. The expansion of the former Friends of the Buffalo River (established in 1989) into the Buffalo Niagara Waterkeeper helped to integrate the Niagara River RAP into regional efforts to clean up the larger watershed, which includes several other AOCs. In 2004, the Niagara River Greenway Commission was established to preserve and enhance the Niagara River Greenway, while emphasizing economic development activities. Although there are separate RAPs for the Ontario side and the New York side, they are formally connected through an international advisory committee (Niagara River RAP Stage 2, 1995). In addition, the Niagara River Toxics Management Plan is binational in scope and has been instrumental in reducing toxic substances’ loadings. |

| St. Lawrence River at Massena and Akwesasne (New York) | New York State DEC is the lead agency for the St. Lawrence River at Massena RAP. Government agencies and potentially responsible parties identified in the Superfund process were most involved in the initial stages of the RAP. DEC formed a Citizen Advisory Committee in the late 1980s to advise on RAP development. The Committee’s focus on evaluating the RAP process in the early stages produced more efficient operating procedures and effective conflict management mechanisms. The CAC disbanded after the submission of the Stage 2 RAP and was replaced by a Remedial Advisory Committee with a charge to provide advice on RAP implementation and restoration targets and ensuring that stakeholders’ interests and concerns addressed. The AOC was then renamed the St. Lawrence River at Massena and Akwesasne to reflect the involvement of the Akwesasne Mohawk Nation. |

| St. Lawrence River at Cornwall (Ontario) | The RAP team was formed in 1986, consisting of agency representatives from Environment Canada and Ontario Ministries of the Environment and Natural Resources. In 1988, a PAC was formed for public involvement in the RAP. The PAC’s desire for a locally based research institute encouraged the creation of the St. Lawrence River Institute of Environmental Science (SLRIES) in 1992. SLRIES has bolstered community engagement and local research capacity in part due to the partnerships they have fostered with regional universities. In 1997, the PAC disbanded and was replaced with the Cornwall and District Environment Committee (CDEC), which currently serves as a public watchdog overseeing the implementation of the RAP, while also monitoring other environmental issues [25]. The St. Lawrence River Restoration Council (SLRRC) was originally formed in 1989 as forum for information sharing among the involved parties, which included members from the Cornwall PAC, several of their U.S. counterparts from Massena Citizen Advisory Committee, and the Mohawks Agree on Safe Health (MASH) group. The original SLRRC disbanded in 1991. In 1998 it was reinstated with a new purpose focused on oversight and accountability in the implementation of the 64 recommended Canadian remedial actions. The new SLRRC integrated governments and local stakeholders into a single institution—contrasting the earlier approach of separate entities (i.e., RAP team, PAC, and former SLRRC). The SLRRC is currently led by the Raisin Region Conservation Authority. As cleanup and the relative priority of environmental issues has changed over the last decade, the SLRRC has sought to re-examine its mandate, responsibilities, and scope of activity. In 2014, SLRRC evolved into a new organization serving as a river-related environmental communication, education, and coordination hub for future activities on the St. Lawrence River in eastern Ontario. The SLRRC aims to organize a comprehensive network that supports ongoing research and remediation on the river, while at the same time encouraging an environmentally balanced and sustainable approach to recreation and development. |

| Common Changes in Institutional Arrangements That Advanced the Use of an Ecosystem Approach and Other Conclusions | Relevant Key Characteristic(s) | Selected Examples |

| Increased prevalence of local nonprofits acting as an integrative organization for the institutional arrangement | Encourages local ownership of RAP process Fosters integration through broad-based institutional structure Promotes a watershed focus Builds collaboration, partnerships, and capacity |

|

| Effective watershed management has been facilitated through strengthened connections to networks external to RAPs often through a local or regional organization | Promotes a watershed focus Builds collaboration, partnerships, and capacity |

|

| Partnering with scientific institutions has strengthened science-policy-management linkages and can cultivate local scientific capacity | Connects to scientific organizations to understand problems and causes, and support scientifically-sound decision-making |

|

| Institutional arrangements have grown from and evolved into a constellation of strategic partnerships | Builds collaboration, partnerships, and capacity |

|

| RAP institutional structures are increasingly looking beyond just restoring beneficial uses and addressing sustainability and life after delisting | Emphasizes sustainability planning for life after delisting as an AOC. |

|

| Eight AOCs did not experience significant changes to their institutional arrangement likely due to original arrangements being well-suited to implement the RAP and/or the co-existing presence of a regulatory remediation program may have driven RAP progress without needing to amend its institutional arrangement. | Not applicable. |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alsip, P.J.; Hartig, J.H.; Krantzberg, G.; Williams, K.C.; Wondolleck, J. Evolving Institutional Arrangements for Use of an Ecosystem Approach in Restoring Great Lakes Areas of Concern. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1532. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031532

Alsip PJ, Hartig JH, Krantzberg G, Williams KC, Wondolleck J. Evolving Institutional Arrangements for Use of an Ecosystem Approach in Restoring Great Lakes Areas of Concern. Sustainability. 2021; 13(3):1532. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031532

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlsip, Peter J., John H. Hartig, Gail Krantzberg, Kathleen C. Williams, and Julia Wondolleck. 2021. "Evolving Institutional Arrangements for Use of an Ecosystem Approach in Restoring Great Lakes Areas of Concern" Sustainability 13, no. 3: 1532. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031532

APA StyleAlsip, P. J., Hartig, J. H., Krantzberg, G., Williams, K. C., & Wondolleck, J. (2021). Evolving Institutional Arrangements for Use of an Ecosystem Approach in Restoring Great Lakes Areas of Concern. Sustainability, 13(3), 1532. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031532