Abstract

This paper investigates the nexus of geopolitical risks (GPRs), economic policy uncertainty (EPU), and tourist arrivals in South Korea. Specifically, this research examines whether arrivals from neighboring tourism source countries (i.e., China and Japan) are influenced by geopolitical events and economic volatilities in South Korea. To establish the research purpose, we investigated the relationships among GPRs, EPU, and tourism demand by using monthly data from January 2003 to November 2019. Additionally, innovative techniques (continuous wavelets, wavelet coherency, and wavelet phase difference) were employed, which allow the decomposition of time series considering different time and frequency components. The results demonstrate inconsistent and heterogeneous co-movements between variables that are localized across different time periods and frequencies. In addition, we detected several significant coherencies that prove the important role of GPR and EPU in explaining changes in the numbers of tourists arriving in South Korea from China and Japan. In terms of time domain, negative and positive correlations in tourism demand were detected, meaning that economic and geopolitical shocks may not always lead to negative consequences. From the frequency domain, the causal effects of GPR mostly appear to have short- to mid-run implications, with almost no relationship in the low-frequency band, whereas EPU holds a heterogeneous influence varying short-term to long-term, including higher to lower frequencies. Results show the resilience of the tourism industry against the transient effects of economic and geopolitical shocks. Tourists become adversely affected by external events such as geopolitical risks and economic uncertainties, but the impact is not consistent over time for tourists from countries neighboring Korea. The findings provide a deeper understanding of how crisis events, including political instability and economic fluctuations, can affect inbound tourism in geographically and historically interrelated countries. Therefore, to minimize the negative effect on tourism demand, it is important for practitioners to consider potential external threats when making forecasts.

1. Introduction

Tourism has emerged as a significant contributor to a country’s economy, where the inflow of tourists results in the creation of more opportunities to provide services, the attraction of foreign investment to promote development, currency-exchange earnings, and tax-related revenues from tourism activities [1,2,3]. The extant literature reports examples of evidence confirming the impact of tourism on economic expansion. [4]. A positive correlation was detected between the tourism sector and economic development with the former substantially contributing to the generation of economic benefits [5]. In addition, several studies have demonstrated a positive causal relationship existing between the tourism industry and economic expansion (GDP) [6,7]. Recognized as an industry largely enhancing sustainable socio-economic growth of destinations, it is thus important for host countries to actively provide a proper tourism environment to attract visitors from across the globe [3,8].

Meanwhile, tourists have a certain tendency to visit a region due to geographical proximity, cultural similarities, time economy, for budget-related reasons, and for other influential factors [9]. This study focuses on three neighboring countries in Asia. Specifically, as inbound tourism markets for South Korea, arrivals from Japan and China are examined, taking into account their geographical and historical interrelations. Since ancient times, various kinds of exchange have been carried out among them, including cultural characteristics, religions, lifestyles, and architecture, and others [10]. However, the contradictions that arise among these three countries have been ignored, which has frequently led to military clashes in the struggle for territorial predominance and supremacy in the East Asian region [10]. All these events, to some extent, have left a mark on the national character and the formation of relations among these neighbors.

South Korea, China, and Japan have become closely interconnected in terms of tourism activities, with nationals from these neighboring states positioned as an important target market and source of income. For instance, according to the Korea Tourism Knowledge and Information System [11], since 2003 the two leading tourism markets inbound to South Korea have been China and Japan. Despite efforts made by South Korea to draw more tourists from other cultural backgrounds to diversify its tourism market, Chinese and Japanese tourists remain the biggest contributors to South Korea’s economy [12]. Considering the existence of a durable relationship between revenue generated from tourism and economic development, it is of significance to emphasize the role that visitors from these source countries play in the long-term prosperity of the tourism industry in their neighboring states [13]. In this regard, investigation of factors affecting steady maintenance of tourist inflow is crucial to ensure economically sustainable growth of the destination.

Since tourism is a geographical, political, historical, cultural, social, and economic phenomenon, global trends in contemporary tourism activities are developing, which can lead to either quantitative increases or decreases in tourism demand. The economic sustainability of the tourism industry can take a downturn when experiencing the effects of external events like political instability or economic uncertainty [14,15,16]. These factors can be defined as macro-environmental trends (both global and local) over which the tourism sector has little or no control. A number of studies have empirically shown the susceptibility of the tourism industry to geopolitical situations and macroeconomic uncertainty (e.g., a global economic crisis) that could disrupt the inflow of tourists and consequently decelerate economic growth [17]. Such changes in geopolitical stability or economic conditions, as a result, can impact the overall tourism industry, including the flow of tourists, their decision-making processes when choosing destinations, perceived risks, foreign investment, and earnings from foreign currency exchange, etc. [14].

Additionally, researchers of international relations have widely examined South Korea, China, and Japan, and have suggested that various conflicts between neighbors are deeply rooted in historical issues, which have triggered political and economic retaliation [18]. For example, Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) deployment in South Korea caused a South Korea–China dispute in 2017, and a South Korea–Japan trade dispute in 2019 generated a South Korean boycott of Japanese products, which in turn negatively affected tourist arrivals [18,19]. It is quite apparent that tourism can experience fluctuations when confronted with various geopolitical instabilities, together with economic volatilities, which can disrupt the sustained growth in tourism.

To complement the extant literature in the context of external factors affecting tourism, this study addresses two objectives. Our primary goal was to investigate the impact of geopolitical risks (GPRs) and economic policy uncertainty (EPU) on inbound tourism from countries neighboring South Korea. While GPRs include critical events such as wars, terroristic acts, political tensions within or between nations, and diplomatic conflicts [3,20], EPU reflects uncertainties regarding the economy, trade, finance, and policy-related matters, which are often associated with a global financial crisis [21]. Tourism researchers have suggested that both GPRs and EPU influence tourism arrivals significantly [3]. However, the impacts of GPR and EPU on tourism demand in the Asia-Pacific region should be considered at the domestic level rather than the global level because of the geopolitical location and other elements among neighboring countries [22].

This research investigated the nexus of GPR, EPU, and tourist arrivals in South Korea. Specifically, we examined whether arrivals from neighboring tourism source countries (i.e., China and Japan) are influenced by geopolitical events and economic volatilities in South Korea. The study’s results will facilitate a more in-depth and detailed analysis of co-movement between the variables. In addition, this research employed a wavelet approach to analyze the effects of domestic GPR and EPU in South Korea on inbound tourism in both time and frequency domains. The methodology provides a dynamic picture of coherencies among the time series alongside the direction and causalities of their interconnection.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Political Instability and Tourism Activities

Security and safety are considered significant primary factors when planning international travel vacations. Hence, situations such as warfare, political coups, strikes, protests, or even deteriorating relations between countries may lead to problems in tourism development and attraction of visitors [23]. It is no surprise that people might fear traveling to places with a weakened level of safety. This behavior is rooted in evolutional processes, and thus, closely relates to the instinct for self-preservation in both humans and animals. Nothing has changed much in the way we perceive events jeopardizing our lives, except for the fact that our world has grown more complex, developed, and sophisticated than it was thousands of years ago. Tourists are usually inclined to avoid traveling to risky places, and instead prefer destinations with a lower perceived risk [24]. This is why perceived risk can be considered one of the most important deterrents that can affect tourists’ behavior and the decision-making processes for potential destinations [25]. Specifically, it can have a serious impact on inbound tourism, resulting in a negative perception of the destination in tourists’ minds.

Interestingly, according to the existing body of literature, some destinations may be estimated to have greater travel risks than others [23]. As stated in a study by Balli et al. [15], such associations can be directly related to the attractiveness of a particular destination. In other words, if countries have appealing tourism destinations, the level of geopolitical risk will be minimal because of the desperate desire of tourists to visit these destinations. In such circumstances, tourists might not perceive a potential risk as serious, despite its presence.

For instance, research by Ingram et al. [23] on the relationship between tourism and political instabilities, including terrorism in Thailand, showed that although there was a negative depiction of Thailand in the media, it still proved to possess quite a strong and favorable image for foreign tourists. In such cases, the tourism industry appears to be temporarily affected by political events, indicating that the effect of the instability is short-lived and predicted to not last too long. Conversely, a study by Tiwari et al. [3] empirically found that events in India related to political instability appeared to have negative impacts on international tourist arrivals, especially in the long term. Surprisingly, however, in some periods, the relationship between tourism and political instability was seen to have positive characteristics. Such results may be interpreted as meaning that despite the high levels of political instability of a destination, people still might be willing to risk it and go because of cheap airfares and accommodation [3]. This is congruent with the findings of Ingram et al. [23] who suggested that such holidays amid unstable political situations are likely to be undertaken by less-risk-averse tourists.

Still, the extant literature argues that, generally speaking, the tourism industry is inclined to become adversely influenced by political unrest, terrorist attacks, and other political events. In a study by Saint Akadiri et al. [14] conducted in Turkey, the findings demonstrated that both tourism development and economic growth are reduced during periods with high levels of geopolitical risk. Such results are in line with the idea that when a certain shock hits a particular area, there is a high likelihood of people abstaining from traveling to that destination due to safety and security concerns. However, other interesting questions arise: How long might the impact last? Does it exert a short-term or long-term effect? Some scholars have stated that shocks and volatilities can have either temporary or long-lasting impacts on tourism demand [26]. Research by Liu and Pratt [27] found that even though tourism appears to be resilient to terrorism, it tends to affect the industry in the short run. Some other studies have also shown that political instability contributes to the fluctuations in inbound tourism in a transient manner [28].

Our study focuses in particular on investigating the causal relationship between geopolitical risks and tourism activities in South Korea, China, and Japan. Due to the geographic proximity of these states, both political and economic interconnections among them are inevitable, so we first explored whether a correlation exists between countries’ geopolitical situations and inbound tourism from each of the aforementioned states. Secondly, we attempted to uncover the strength of the relationships and the direction of the dependency between geopolitical risk and tourism in South Korea, China, and Japan; and third, we examined the impacts’ longevity in the short run or the long run.

To quantitatively capture the effects of geopolitical risks on tourism, this study employs the newly introduced GPR index developed by Caldara and Iacoviello [20]. It can be understood as the “risk associated with wars, terrorist acts, and tensions between states that affect the normal peaceful course of international relations.” The GPR index was composed to calculate the number of times articles associated with geopolitical tensions appeared in newspapers. The index is based on text searches for keywords that can be divided into six categories: geopolitical threats, nuclear threats, war threats, terrorist threats, acts of war, and terrorist acts—events that can disrupt the stability of both domestic and international relations [29]. Because this index depicts changes and trends in the geopolitical situation globally, our goal is to employ country-specific data to trace the nexus of GPR and inbound tourism in South Korea, Japan, and China, which from time to time tend to experience political rows and misunderstandings. Thus, such conflicts might somehow be reflected in the numbers of tourists from those countries.

2.2. Economic Uncertainties and Tourism

A two-way connection exists between tourism and the economic sector. Because tourism can truly be recognized as one of the fastest growing industries, it is a more important, significant contributor to the economic growth of a country [30]. However, economic factors can exert a significant impact on the tourism industry, both globally and domestically. Wang [31] mentioned that tourism demand is highly vulnerable to economic changes. When the economy experiences fluctuations and uncertainties, it can subsequently influence the level of demand and supply in tourism destinations. In general, with increased levels of economic uncertainties, individuals and firms tend to reduce consumption and save more until the situation comes back to normal [17]. Tourism itself encapsulates an export commodity that requires relatively larger sums of investment, compared to goods people use in daily life. Tourism expenditures are said to be more sensitive to times of intensified levels of uncertainty [32]. Hence, in the case of economic shocks, there is a greater possibility that tourists will delay their travel plans for some better time in the future.

The newly developed EPU index by Baker et al. [33] has been gradually stimulating interest among scholars in the fields of economics and finance as a way to assess the impact of uncertainty on different variables, which also include tourism behavior. There is a growing body of research concerning the causal relationship between EPU and tourism activities [21]. For instance, recent studies (e.g., Gozgor and Ongan [34,35]) have examined the impact of economic policy uncertainty on outbound travel expenses, noting that economic policy uncertainty has a significant negative impact on tourism spending, and an increase in uncertainty leads to a decrease in expenditures. A tourism product is not part of life’s essentials, such as food, home, clothes, or family necessities, but rather is a discretionary expenditure that people make voluntarily, depending on their desires. Hence, it is suggested that, during a time of difficult economic conditions, individuals start to act thriftier, and may decide to cut expenses by postponing travel in order to feel more secure and stable. In another study on the impacts of GPR and EPU on tourism in a developing state (i.e., India) by Tiwari et al. [3], the results revealed that EPU appeared to have short-run consequences on tourist arrivals. It was found that GPR has a much stronger impact than EPU, where GPR appeared to show long-term implications on tourist arrivals.

Some of the results showed a positive correlation between economic uncertainties and tourist arrivals. Tourists still may choose to travel, despite a time of heightened economic and financial situations. Such choices may be explained for the so-called value-for-money destinations (for instance, places with favorable exchange rates for foreign travelers). However, another study by Balli et al. [17] investigated the relationships of global economic policy uncertainty and domestic economic policy uncertainty with tourist inflows. The findings showed that both local and global EPUs have a strong and negative impact on tourist flows. It is worth mentioning that tourists might monitor the current economic situation in a destination they plan to visit. Thus, if the exchange rate is unfavorable, or if there are any volatilities in local prices and service quality, that might also lead to a decrease in tourist arrivals due to the disadvantageous economic conditions. That is, tourism demand is negatively affected by foreign exchange risk [36]. This is why policy makers need to take into consideration both global and local uncertainties when forecasting tourism demand. Referring to the extant body of literature, we were able to observe that economic uncertainties and volatilities exert a serious impact on the development of tourism industry, especially in areas that are largely dependent on service-oriented sectors.

3. Methods and Data

3.1. Methods

The present study utilizes wavelet analysis to investigate the effects of domestic GPR and EPU on inbound tourism in South Korea, especially focused on the main source markets of inbound tourism, i.e., Japan and China, in both time and frequency domains. In detail, to examine the obtained data, wavelet coherence and wavelet phase difference techniques were performed by employing MATLAB 9.6 (R2019a) software platform. To the extent of our research, application of the wavelet method to the tourism field can still be considered relatively novel, and a few existing studies have implemented it practically in the context of tourism [3,15,21,37].

This analytic tool facilitates a time–frequency based analysis. The main advantage of this method is that it concentrates on both time and frequency features of co-movement, and on causalities among GPR, EPU, and tourism demand. It allows the capture of variations in the relationship between variables in different time dimensions, and enables the detection of local features of the investigated time series, unlike the conventional time domain based econometric methods (such as auto-regression models, the causality test, and correlation analysis) [21]. Wavelet analysis was introduced to provide more information for a comparison with Fourier analysis. The main advantages of wavelet analysis include time-localized details together with frequency details of the variations in the relationships between the signals. Additionally, it is worth mentioning that while Fourier analysis is mainly utilized for stationary signals, the use of wavelet analysis was extended to allow investigation of non-stationary series [38,39].

Generally, wavelet transform is utilized to break down a time series into some basic wavelets that are localized in both time and frequency domains [39]. There are two types of wavelet: discrete wavelet transform (DWT) and continuous wavelet transform (CWT). The first refers to the process of noise removal and decomposition of data, whereas the second is said to encompass data extraction and detection of data similarity [37,39,40]. Based on methodological considerations from existing studies, the current research implements CWT as a useful tool to examine the effects of GPR and EPU on inbound tourism demand in South Korea by decomposing the concerned series into wavelets [21].

The CWT of a given time series, x(t), can be defined as a convolution type:

where the asterisk indicates complex conjugation, and reveals the complex conjugate function of , namely, the basic wavelet function.

To analyze the effects of domestic GPR and EPU on inbound tourist arrivals in South Korea, a wavelet coherence tool needs to be applied. It allows a three-dimensional analysis, which considers both time and frequency components alongside the strength of the correlation between investigated signals [39]. Therefore, this method makes it possible to simultaneously observe time variations and frequency variations in the interrelationships between series [21]. Torrence and Webster [41] defined wavelet coherence as follows:

where the above squared types represent wavelet coherence, and S is a smoothing operator.

In the absence of smoothing, coherence is equal to 1 on all scales and at all times [39]. Therefore, using a smoothing operator gives a quantity between zero and 1 in the time–frequency window [21], where zero wavelet coherence implies no co-movement between time series, whereas the highest coherency shows the strongest co-movement between signals. In practice, if the co-movement between two time series is significant, it is depicted in red, while blue corresponds to a weak relationship [21]. is a cross wavelet power, which can be understood as a local region in the time-scale space, showing the covariance between two investigated time series.

However, since coherency is squared in the formula, it is not possible to examine whether co-movement between the time series is positive or negative. Thus, based on the theoretical foundation in the existing literature, wavelet phase difference (WPD) is employed in this study to further investigate the dependence and causality relationships among GPR, EPU, and inbound tourism in South Korea. To be more exact, wavelet coherence phase differences explain the lead–lag effect, which shows the degree of the causal relationship between time series (GPR, EPU, and inbound tourist arrivals). Following the materials of Bloomfield [42] and Torrence and Webster [41], WPD depicts the coherence phase between x(t) and y(t) as stated below:

where I and R in the equation are the imaginary and real parts of the smoothed cross-wavelet transform.

3.2. Data

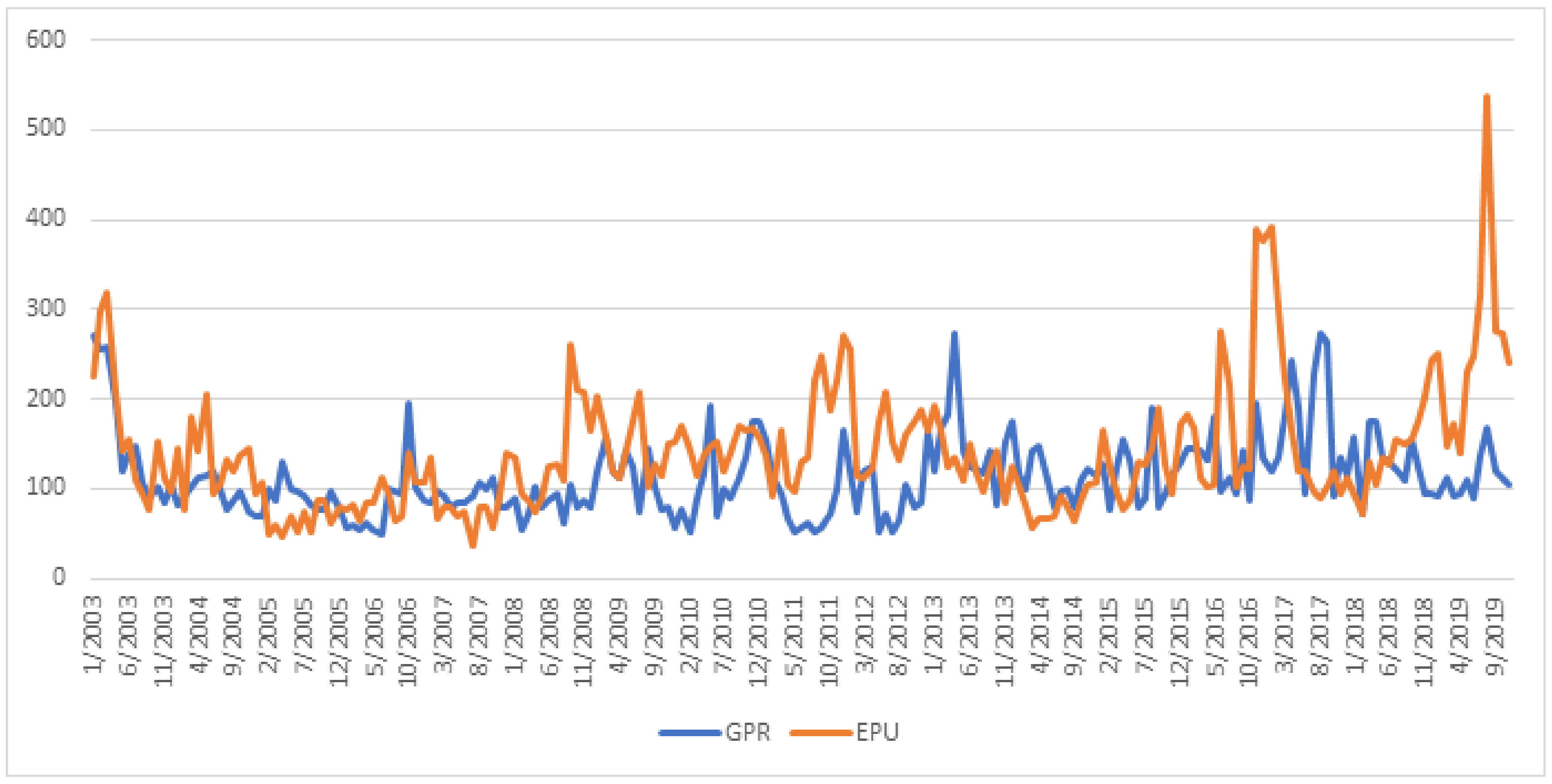

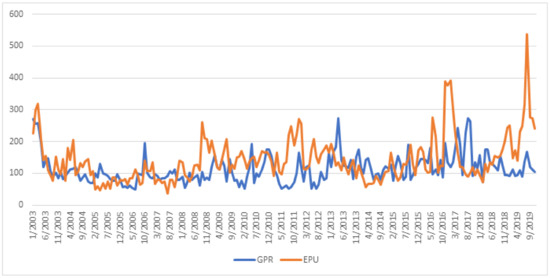

The current study considers monthly data for inbound tourism together with domestic EPU and GPR indexes for South Korea. Monthly statistics reflecting tourist arrivals were extracted from official tourism websites. The sample period was decided by data availability for the measure of inbound tourism in South Korea, and therefore, it spans January 2003 to November 2019 because mobility restrictions of international travelers have been imposed since the outbreak of COVID-19. The data in the EPU index were introduced by Baker et al. [33], and the GPR data were obtained from Caldara and Iacoviello [20]. Figure 1 illustrates the time trends of South Korea’s domestic GPR and EPU index from January 2003 to November 2019.

Figure 1.

Time trends of Domestic GPR and EPU index in South Korea.

4. Results

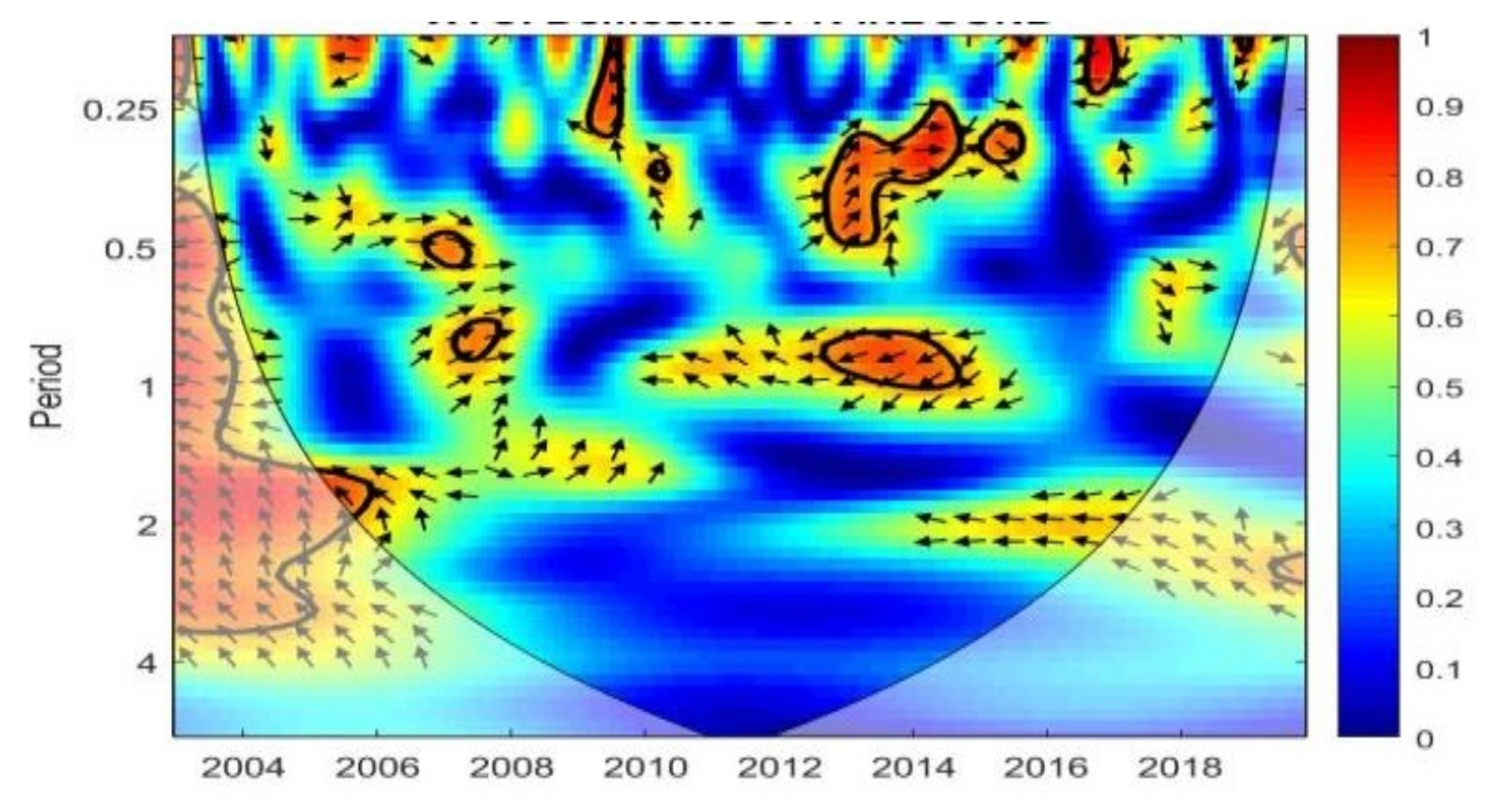

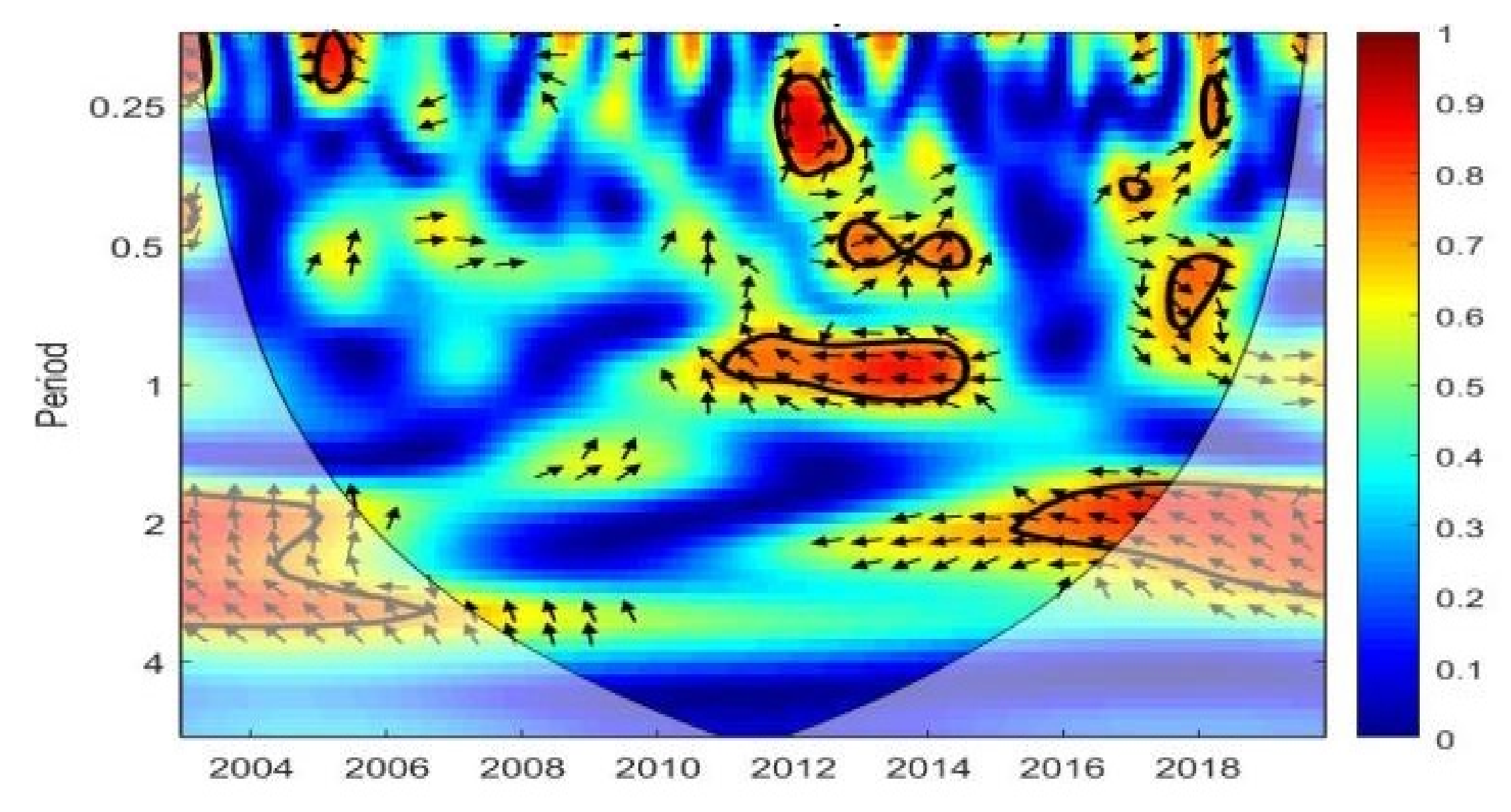

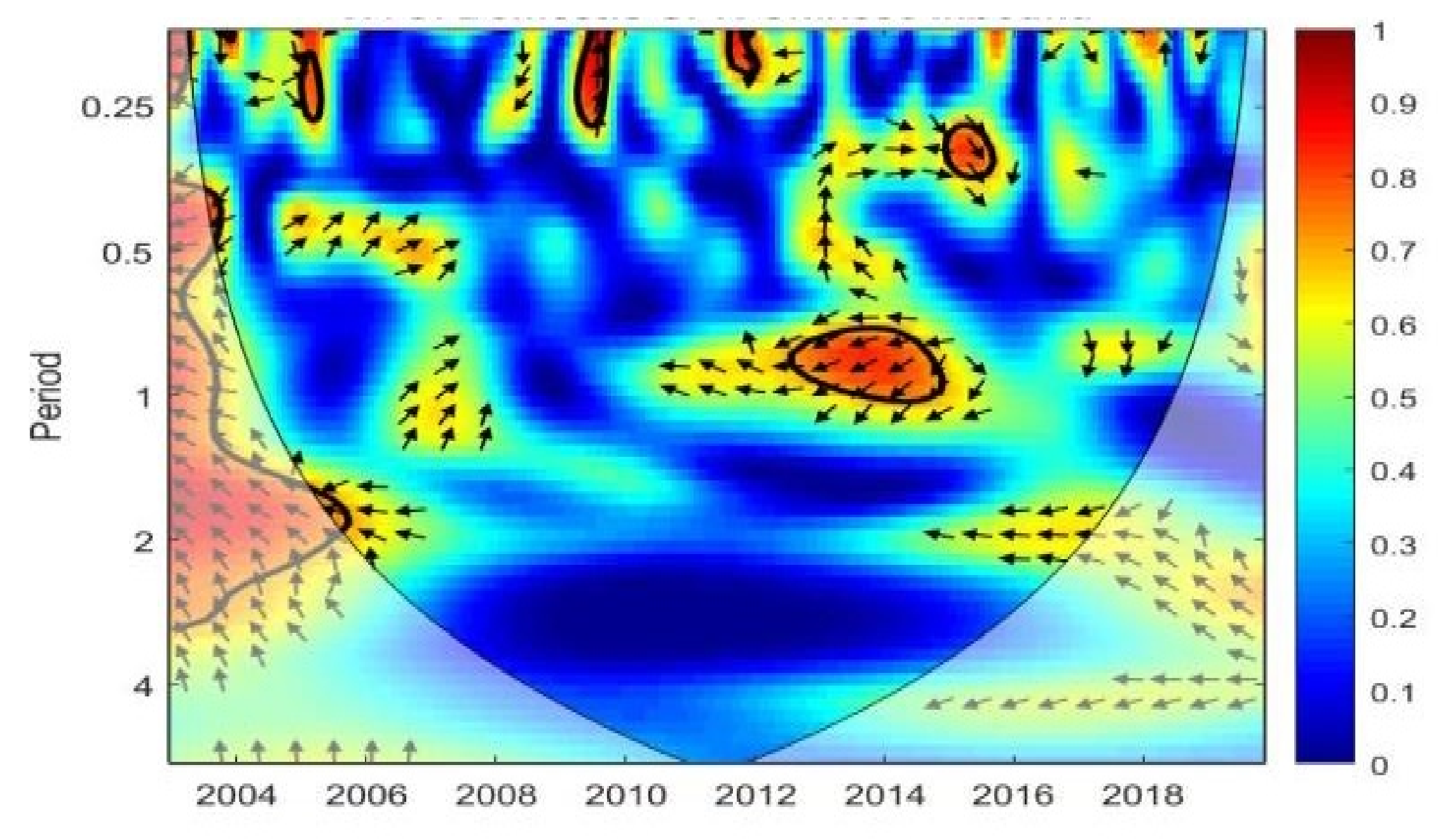

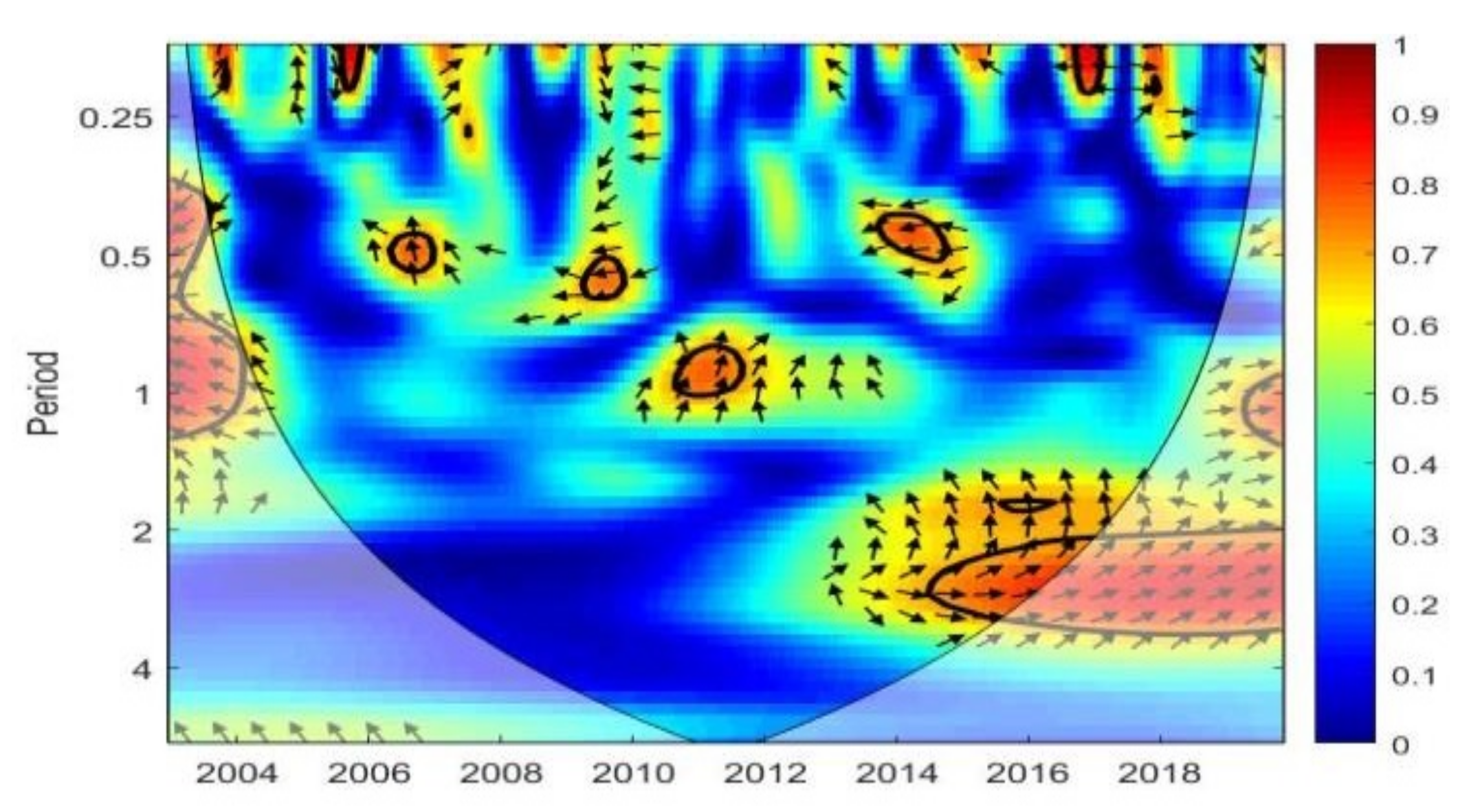

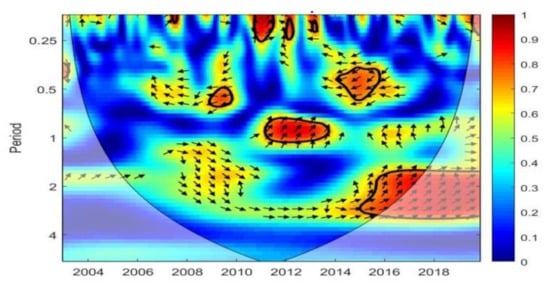

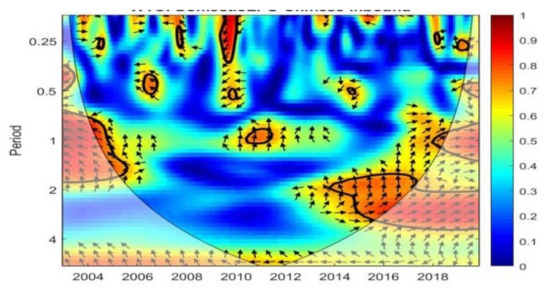

The patterns shown in the figures below identify the relationships among domestic GPR, EPU, and inbound tourism demand in South Korea, focusing on neighboring source countries (i.e., China and Japan). The horizontal axis indicates the periods of the data analyzed, and the vertical axis indicates the frequency, from highest (at the top) to lowest (at the bottom). In the figures, red identifies zones with strong coherencies between the variables, whereas blue represents weak or absent relationships between the time series. The black contour line illustrates the areas of statistical significance at a 5% level generated from 10,000 sets of Monte-Carlo simulations [3]. To detect and quantify relationships among GPR, EPU, and tourism demand including directionality and time–frequency dependencies, the phase difference is reflected by arrows in the wavelet coherence plot [39].

4.1. South Korea’s Domestic GPR and Inbound Tourism

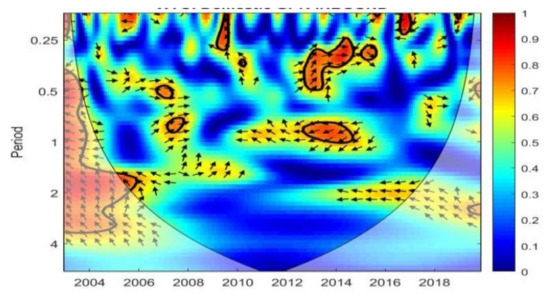

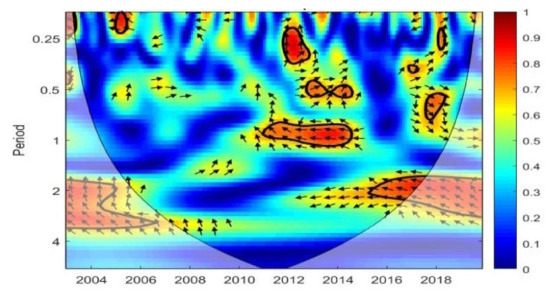

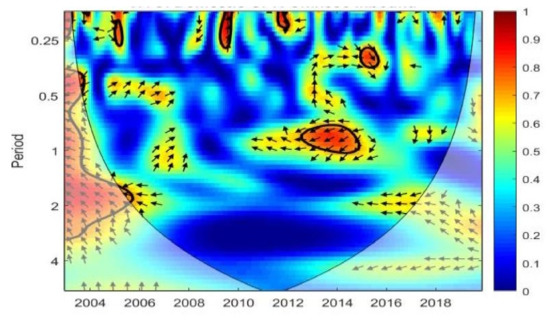

The coherencies in South Korea’s domestic GPR with inbound tourism demand are exhibited in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4. Specifically, Figure 2 presents the coherency in South Korea’s domestic GPR with total tourist arrivals, and Figure 3 and Figure 4 present country-specific tourist arrivals from Japan and China, respectively.

Figure 2.

Domestic GPR—Total Inbound Tourist Arrivals in South Korea.

Figure 3.

Domestic GPR—Inbound Tourist Arrivals from Japan.

Figure 4.

Domestic GPR—Inbound Tourist Arrivals from China.

In the figures, red zones are detected, indicating the presence of the relationship between domestic GPR and inbound tourist flows. Specifically, as shown in Figure 2 and Figure 4, the red areas together with arrows pointing left and downwards show that domestic GPR has a leading negative influence on tourism inflows. On the whole, the patterns depicted in the three figures imply the presence of short-run and mid-run coherencies of up to one year, but the islands do not seem to have a strong and consistent effect, meaning that inbound tourism in South Korea is not significantly affected by geopolitical shocks in the long term. It is presumable that the majority of geopolitical events visually appear to have a short-run and mid-run impact of from three months to one year in the frequency band.

Two significant clusters showing strong coherencies between geopolitical shocks and tourism demand can be detected. The first is located in the mid-term frequency band (eight months to one year) during the period from 2012 to 2015, indicating a negative leading impact from domestic GPR on inbound tourism demand. However, in the figures, we observe another interesting correlation between domestic GPR and inbound tourism. The period of the cluster similarly stretches from approximately 2012 to 2015 and seems to have a short-run impact in the three- to six-month frequency band. However, it is worth noting that arrows are facing up and to the right, which indicates that the two time series are in phase, and local GPR has a positive leading effect on inbound tourism in South Korea.

Another interesting point seen in the figures is that despite the quite dangerous geographic proximity of South Korea to North Korea, the tensions from which top the current geopolitical threats [43], this does not necessarily demonstrate a significant impact on inbound tourism. Based on such results, we can conclude that although the potential nuclear risk from North Korea is present, which may hypothetically result in war, tourists traveling to South Korea from China and Japan do not consider South Korea as a highly volatile destination regarding risk perceptions. According to Fuchs and Reichel [44], tourists perceiving high-risks regarding a destination tend to use risk reduction strategies. In particular, non-repeat tourists are likely to reduce their risks by consulting with previous tourists to the destination, while repeaters by making decisions with relatives and friends. That is, because many tourists from China and Japan have visit experience to South Korea, the destination is perceived by tourists as a popular and safe destination to travel not only for repeat tourists but also for first-time visitors. This implication is congruent with the study of Balli et al. [15], emphasizing that if a country has attractive tourist spots, the impact of GPR on people’s intentions to visit that country will not be high.

From Figure 4, we can see that the relationship between domestic GPR and Chinese tourists visiting Korea is not consistent over time. There are some strong coherencies between the time series in certain periods; however, they are mostly located in the short-term frequency band. Domestic GPR in South Korea was strongly related to Chinese inbound tourist arrivals from 2012 to 2015, with the impact of the dependence ranging from eight months to one year (mid-run). In this relationship, the arrows point left and down, which implies an out-of-phase movement, with GPR leading. The results can be interpreted as follows. When two time series are out of phase, it means they move in opposite directions. Based on a news search, this timing coincided with the following actions by the South Korean government. To compensate for the decline in Japanese visitors, South Korea decided to ease visa restrictions for mainland Chinese, which further boosted the local tourism industry with a new source of income from Chinese tourists. Such a move registered very strong growth in international arrivals from China. Therefore, it is possible for an interesting phenomenon to be captured where geopolitical situations between states can serve as a turning point with enough power to change the direction and bring in a new source of tourist inflows. Hence, the timing is important, and there are cases when the increase in geopolitical risk can contrarily induce growth of inbound tourism.

By contrast, in Figure 3, the regions showing strong coherencies between domestic GPR and Japanese visitors are more evident. The locations of islands in red are also diverse, ranging from high-frequency to low-frequency bands with short-run and long-run impacts, respectively. In the period between 2011 and 2015, there is a significant zone showing a strong relationship between the time series, but the directions of the arrows seem to vary. Both the domestic GPR and inbound Japanese tourists are out of phase, with the arrows pointing to the left. The impact of the coherence seems to be mid-run, ranging up to one year in the frequency band. Chronologically, this time coincides with a decrease in Japanese tourists to South Korea due to the unfavorable exchange rate between the Korean Won and Japanese Yen. Although Japan is today the second largest market for inbound tourism (following China), before 2012, the majority of international visitors were Japanese and accounted for approximately 40% of the total international arrivals, followed by China and the U.S. at 11% and 9%, respectively. Thus, although the underlying source of the drop in Japanese tourists mainly lay in Japan’s change of economic policies aimed at boosting domestic demand and gross domestic product, such economy-related events can also (in a certain way) disrupt the peaceful and stable development of geopolitical relations between South Korea and Japan.

Besides, the figure also suggests two clear, strong, short-run correlations of approximately three to five months in the period from 2012 to 2015. However, it should be noted that those zones identify positive relationships. For the first region, the arrows point up and slightly to the right, underlying the leading effect of GPR. Contrarily, the second island is located in the lower frequency band from six months to one year where the arrows point to the right and downwards with Japanese inbound leading. In 2017, there is also a small red region signifying coherency with an impact from six months to one year in the frequency band. Surprisingly, the relationship also appears to be positive, with Japanese inbound leading and GPR lagging. It grew from the connection in the short-run impact with the arrows pointing up, indicating a leading effect from GPR. Such changes in direction can be seen as an interesting phenomenon and should be more deeply investigated.

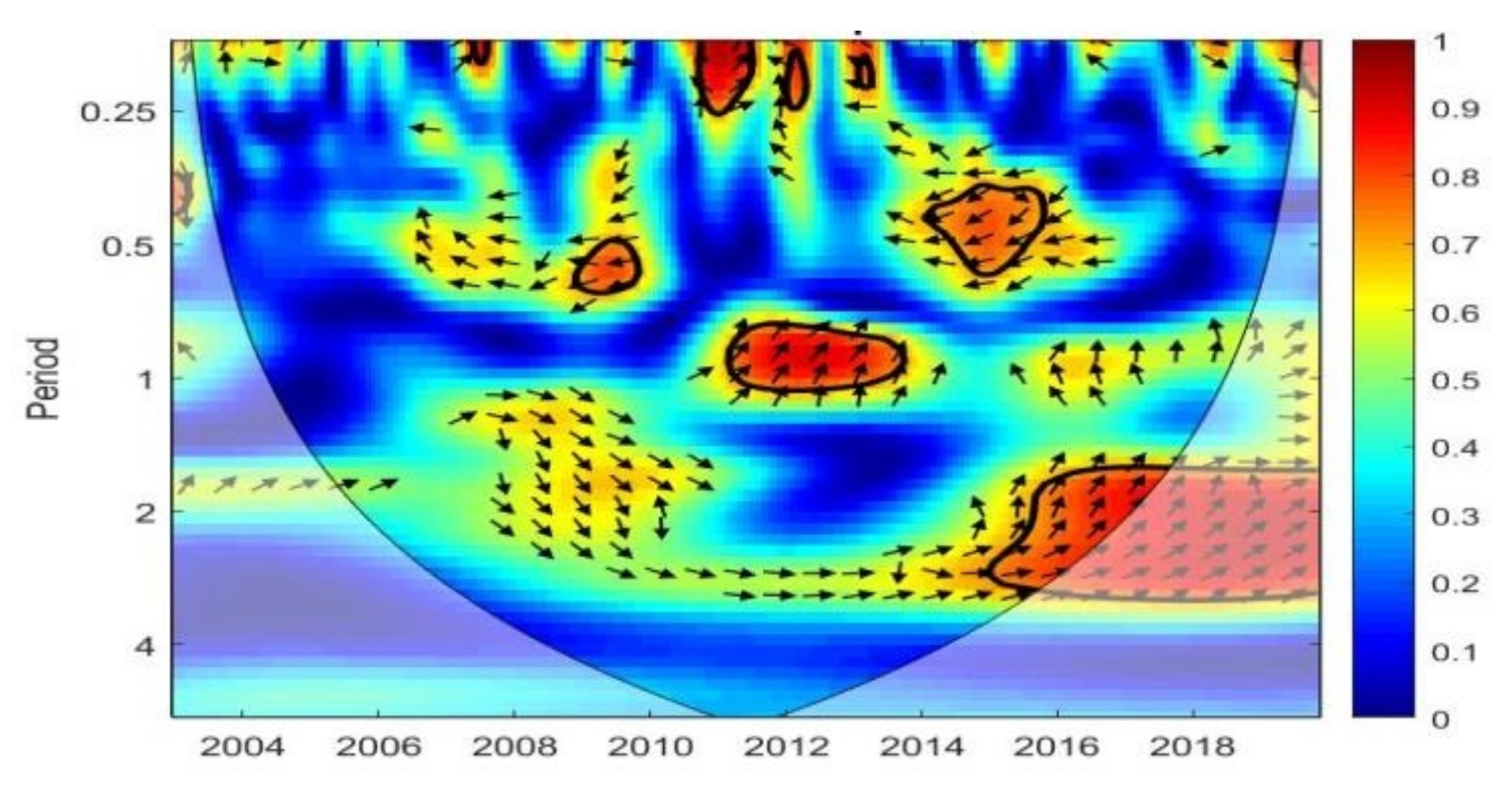

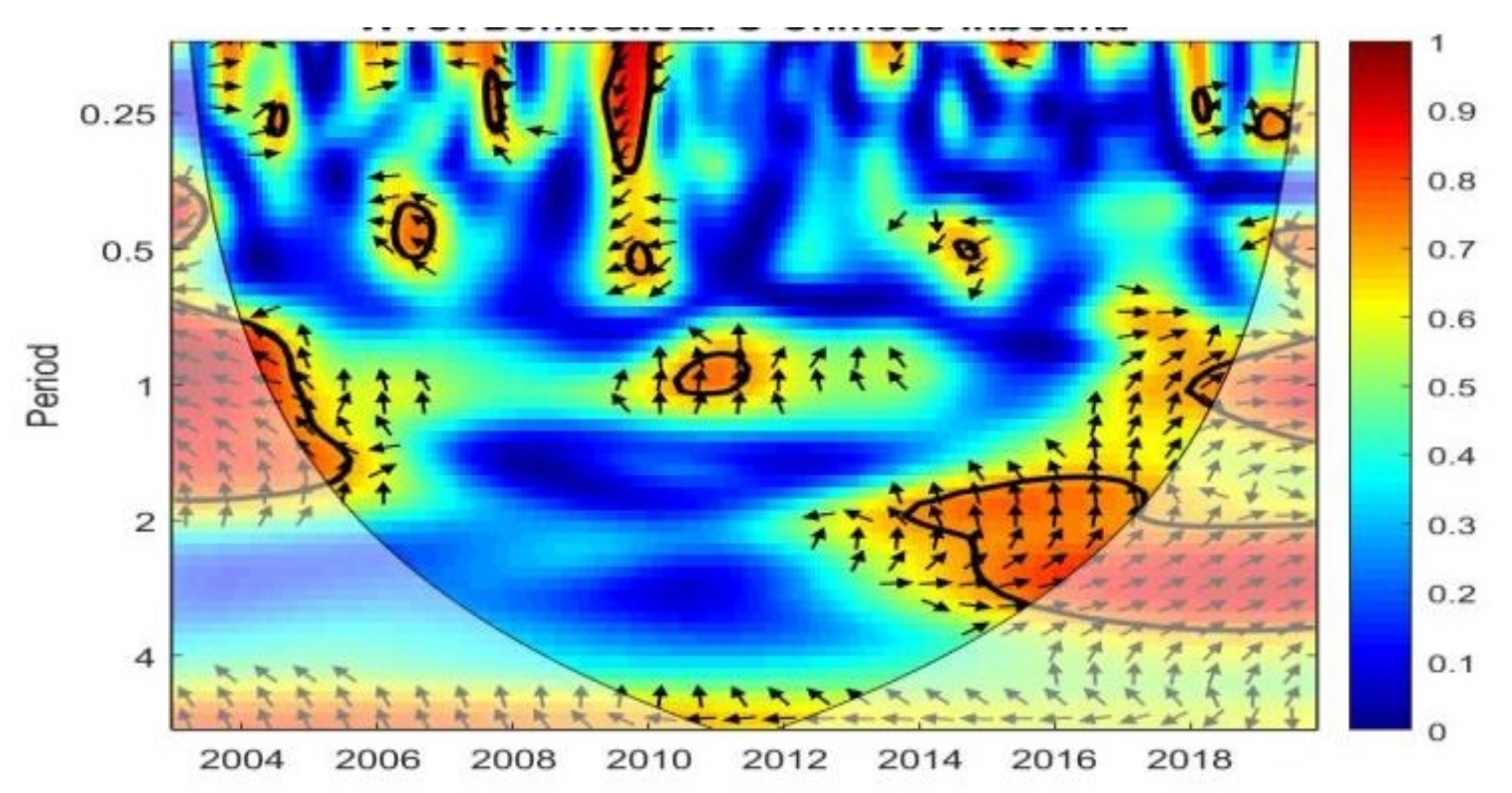

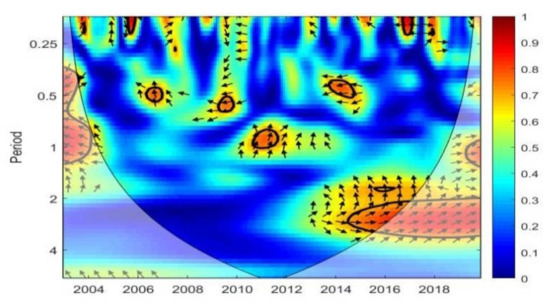

4.2. South Korea’s Domestic EPU and Inbound Tourism

Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 show wavelet coherence results. In the interrelationships of South Korea’s domestic EPU-tourist arrivals from China (Figure 6) as well as South Korea’s EPU-tourist arrivals from Japan (Figure 7), significant correlations are found in the short-term, mid-term, and long-term co-movements.

Figure 5.

Domestic EPU—Total Inbound Tourist Arrivals in South Korea.

Figure 6.

Domestic EPU—Inbound Tourist Arrivals from Japan.

Figure 7.

Domestic EPU—Inbound Tourist Arrivals from China.

The correlations observed are for one to six months, for six months to one year, and in two- to four-year cycles. First, there are some negative correlations between domestic EPU and inbound tourism for the time scale of the mid-run band (six months to one year) specifically around 2008 (during the Global Financial Crisis) with EPU leading. However, the effect of EPU does not appear to be consistent. Such results are in line with studies by Tiwari et al. [3] and Wu and Wu [21], where the effect of the relationship was mostly found in the lower frequency but was weak. It signifies that despite the presence of a difficult economic situation, the impact of EPU on foreign tourists’ intentions to visit South Korea was not strong. Regardless of the presence of certain economic uncertainties, people were still willing to visit this Asian destination. Thus, in this state of affairs, the economic crisis appears to have had little impact on the strongly resilient tourism industry in South Korea.

There are evident, strong, short-run coherencies with Chinese tourists, yet in the figures above, the power of the relationship between Korea’s domestic EPU and Japanese tourists appears to be quite stronger, with larger regions in red plus diverse localization in the period of time. Based on spectral results, we can see that the connection between domestic EPU and Japanese inbound tourists appears to be stronger than with Chinese tourists. Specifically, it is possible to identify the common area of significant coherence in the low-frequency bands from two to four years for all three figures spread over the sub-period from 2014 on. Interestingly, as pictured in the figures, coherencies seem to be in phase, with domestic EPU leading. This is congruent with the results of Tiwari et al. [3], pointing out that (sometimes) unstable economic situations domestically may create favorable conditions (such as beneficial exchange rates) for foreign tourists to visit a particular country.

5. Conclusions

The relationships between countries have evolved into a complex system that addresses, and subsequently impacts, such areas as economics, politics, business, finance, trade, and tourism, thus making states more dependent upon each other in the geopolitical context. Gaining a better understanding of the nexus between external shocks and tourist inflows from neighboring countries will provide practitioners with relevant information useful for establishing further strategies to enhance sustainable economic development of a tourist destination. In this regard, the present research investigated whether tourists inbound to South Korea from China and Japan are affected by domestic GPR and EPU. We utilized monthly data from the GPR index and EPU index. Additionally, to empirically capture the behavioral patterns in relationships among GPR, EPU, and tourism demand, the wavelet transform approach was applied. Based on the results, the following implications can be drawn.

First, we detected some interconnections between tourist arrivals and economic uncertainties, but the relationship did not appear to be consistent over time, and was restricted to only certain periods without significant long-term effects. The influence of EPU on tourism flows was reported to be heterogeneous, varying from short-run to long-run impacts during intervals of between two and four years. Overall, wavelet analysis has shown the transient effects of economic and geopolitical shocks, which means that tourists might be adversely impacted by certain events; however, these transient effects do not evolve over time.

Second, it is worth mentioning that, besides negative correlations, we were able to capture some positive relationships between variables. Such results are in line with the research of Tiwari et al. [3], implying the possibility for EPU to contribute to an increase in tourism demand for destinations under specific conditions.

Third, the fact that tourism demand appeared to be relatively immune to external uncertainties occurring between the states might be understood in that tourists consider attractiveness of a tourist destination, safety, and geographic proximity as important factors outweighing economic situations.

Another interesting finding is that tourists’ reactions to such shocks may vary depending on their country of origin. For instance, Japanese tourist flows were found to be more susceptible to shocks related to South Korea rather than China. The results indicate the importance of taking into account economic volatilities when forecasting tourist arrivals from neighboring countries. Hence, governments are responsible for ensuring economic stability in tourism destinations in order to support continuous growth in the tourism sector.

For future research, some limitations should be taken into consideration. First, during the analysis of wavelet figures, we noticed some regions of similar localization between GPR and EPU. According to Tiwari et al. [3] and Wu and Wu [21], political instabilities and economic uncertainties may have some events in common, implying the existence of a mutual interaction between GPR and EPU indexes. For instance, because economic challenges can result in deterioration of political stability or relations between states, war-like events can, in turn, negatively affect economic policies [3]. Therefore, to identify the pure relationships and causalities among GPR, EPU, and inbound tourism, in a future study we hope to exclude the effects of variables on each other by utilizing partial wavelet coherence (PWC).

Lastly, due to restrictions on tourist mobility, we were not able to broadly examine data after the COVID-19 outbreak. Such external factors are not limited to only political issues and economic volatilities, and hence, it is necessary to discover newly changing tourism paradigms in the era of COVID-19. A study conducted in Taiwan by Wang [31] emphasized the importance of viral diseases (such as the SARS outbreak in 2003), unforeseen natural events (e.g., earthquakes), and terrorist attacks (like the September 11 attacks on the U.S.), on the ability to explain the rise and fall of international tourism demand. Therefore, in the next studies, we hope to gain a deeper understanding of changes and trends in tourism demand caused by the impacts of crisis events.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K. and I.K.; methodology, A.K.; software, A.K.; validation, A.K. and I.K.; formal analysis, A.K.; investigation, A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K.; writing—review and editing, I.K.; visualization, A.K.; supervision, I.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Alam, M.S.; Paramati, S.R. The impact of tourism on income inequality in developing economies: Does Kuznets curve hypothesis exist? Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 61, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.A.; Sharif, A.; Wong, W.K.; Karim MZ, A. Tourism development and environmental degradation in the United States: Evidence from wavelet-based analysis. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 1768–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.K.; Das, D.; Dutta, A. Geopolitical risk, economic policy uncertainty and tourist arrivals: Evidence from a developing country. Tour. Manag. 2019, 75, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, F.; Wei, L.; Asif, M. The contribution of sustainable tourism to economic growth and employment in Pakistan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risso, W.A.; Brida, J.G. The contribution of tourism to economic growth: An empirical analysis for the case of Chile. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 2, 178–185. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Ma, H. On Econometric Analysis of the Relationship between GDP and Tourism Income in Guizhou, China. Int. J. Bus. Adm. 2015, 6, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreishan, F.M. Time-series evidence for tourism-led growth hypothesis: A case study of Jordan. Int. Manag. Rev. 2011, 7, 89. [Google Scholar]

- Wakimin, N.; Azlinaa, A.; Hazman, S. Tourism demand in Asean-5 countries: Evidence from panel data analysis. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2018, 8, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keum. Characteristics and Prospects of South Korea’s Inbound Tourism Markets. Seoul Solution, 5 April 2017. Available online: https://seoulsolution.kr/en/content/6558 (accessed on 20 February 2020).

- Hoefer, H.J.; Lueras, L.; Chung, N. Korea: Insight Guides, 1st ed.; Apa Productions: Hong Kong, China, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Tourism Knowledge and Information System Statistics on Tourists. Available online: http://tour.go.kr (accessed on 25 February 2021).

- KBS World. Korea Aims to Attract 20 Million Foreign Tourists in 2020. 27 January 2020. Available online: https://world.kbs.co.kr/service/contents_view.htm?lang=e&menu_cate=business&id=&board_seq=378509 (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- Adnan Hye, Q.M.; Ali Khan, R.E. Tourism-led growth hypothesis: A case study of Pakistan. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 18, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint Akadiri, S.; Eluwole, K.K.; Akadiri, A.C.; Avci, T. Does causality between geopolitical risk, tourism and economic growth matter? Evidence from Turkey. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 43, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balli, F.; Uddin, G.S.; Shahzad SJ, H. Geopolitical risk and tourism demand in emerging economies. Tour. Econ. 2019, 25, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S. Uncertainty, economic growth its impact on tourism, some country experiences. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 83–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balli, F.; Shahzad SJ, H.; Uddin, G.S. A tale of two shocks: What do we learn from the impacts of economic policy uncertainties on tourism? Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, C. (Re)producing the ‘history problem’: Memory, identity and the Japan-South Korea trade dispute. Pac. Rev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.-H.; Kim, I. Co-Movement between Tourist Arrivals of Inbound Tourism Markets in South Korea: Applying the Dynamic Copula Method Using Secondary Time Series Data. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldara, D.; Iacoviello, M. Measuring geopolitical risk. FRB Int. Financ. Discuss. Pap. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.P.; Wu, H.C. Causality between European economic policy uncertainty and tourism using wavelet-based approaches. J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 1347–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Tian, G.; Wu, Y.; Mo, B. Impacts of geopolitical risks and economic polity uncertainty on Chinese tourism-listed company stock. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2020, 1–14, (early view). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, H.; Grieve, D.; Ingram, H.; Tabari, S.; Watthanakhomprathip, W. The impact of political instability on tourism: Interviewee of Thailand. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2013, 5, 92–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kozak, M. Tourist harassment: A marketing perspective. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 384–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neacşu, M.C.; Neguţ, S.; Vlăsceanu, G. The impact of geopolitical risks on tourism. Amfiteatru Econ. 2018, 20, 870–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanouar, C.; Goaied, M. Tourism, terrorism and political violence in Tunisia: Evidence from Markov-switching models. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 404–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Pratt, S. Tourism’s vulnerability and resilience to terrorism. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agiomirgianakis, G.; Serenis, D.; Tsounis, N. Effective timing of tourism policy: The case of Singapore. Econ. Model. 2017, 60, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.H.J.; Chiu, C.-W. How important are global geopolitical risks to emerging countries? J. Int. Econ. 2018, 156, 305–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Lin, S.; Witt, S.F.; Zhang, X. Impact of financial/economic crisis on demand for hotel rooms in Hong Kong. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.S. The impact of crisis events and macroeconomic activity on Taiwan’s international inbound tourism demand. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragouni, M.; Filis, G.; Gavriilidis, K.; Santamaria, D. Sentiment, mood and outbound tourism demand. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 60, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.R.; Bloom, N.; Davis, S.J. Measuring economic policy uncertainty. Q. J. Econ. 2016, 131, 1593–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozgor, G.; Ongan, S. Economic policy uncertainty and tourism demand: Empirical evidence from the USA. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 19, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongan, S.; Gozgor, G. Tourism demand analysis: The impact of the economic policy uncertainty on the arrival of Japanese tourists to the USA. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyócsa, Š.; Vašaničová, P.; Litavcová, E. Interconnectedness of international tourism demand in Europe: A cross-quantilogram network approach. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2019, 526, 120919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.P.; Wu, H.C. A multiple and partial wavelet analysis of the economic policy uncertainty and tourism nexus in BRIC. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 906–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roueff, F.; Von Sachs, R. Locally stationary long memory estimation. Stoch. Process. Appl. 2011, 121, 813–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, L. Co-movement of Asia-Pacific with European and US stock market returns: A cross-time-frequency analysis. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2013, 29, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinsted, A.; Moore, J.C.; Jevrejeva, S. Application of the cross wavelet transform and wavelet coherence to geophysical time series. Nonlinear Process. Geophys. 2004, 11, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrence, C.; Webster, P.J. Interdecadal changes in the ENSO–monsoon system. J. Clim. 1999, 12, 2679–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomfield, P. Fourier Analysis of Time Series: An Introduction; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Willis Towers Watson and Oxford Analytica. How Are Leading Companies Managing Today’s Geopolitical Risks? 2017. Available online: www.oxan.com/services/advisory/country-risk/political-risk-management-survey/ (accessed on 25 February 2021).

- Fuchs, G.; Reichel, A. An exploratory inquiry into destination risk perceptions and risk reduction strategies of first time vs. repeat visitors to a highly volatile destination. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).