Abstract

The risk factors of COVID-19 are not gender-neutral but gendered. A vulnerability approach to pandemics suggests that females are more prone to risk exposure while there are inequalities in accessing resources and opportunities. These inequalities create a gendered pandemic vulnerability. The current article addresses the specific vulnerability on the gendered risk factors encountered by girls and women due to the gendered pandemic in a global context and their impacts on gender inequality. This study analyses the existing literature on the gendered pandemic and risk factors on females that lead to gender inequality during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, this study adopts a vulnerability approach to the pandemic as an analytical concept. Our findings from the systematic literature review suggest that women’s pre-existing vulnerabilities are exacerbated in the wake of the pandemic due to the gendered risk factors worsening the gender equality gap. We conclude by arguing that our study’s finding supports a vulnerability approach to disasters.

1. Introduction

A pandemic such as COVID-19 is a disaster [1]. The risk factors of the COVID-19 pandemic are not gender-neutral but gendered [2]. Although this is a disease outbreak, gendered socio-economic impacts are visible with varied consequences for men and women in employment positions, in the social protection system, and in the division of unpaid household work and care [3]. The extent of the thrust of the pandemic’s impact on men and women depends both on their pre-crisis roles and the policies that either mitigate or exacerbate these effects [2]. To date, the pandemic has hindered multiple forms of progress made in gender equality, female empowerment, and efforts to reduce gendered violence. The pandemic threatens to reverse hard-won gains in gender equality, exposing women’s vulnerabilities based on their pre-pandemic social, economic, and political situations [4].

The pandemic has posed devastating gendered risks for women in the global context [1]. Even children and other dependants are in jeopardy when women encounter varied risk factors during and after an outbreak [5]. Risk factors are conditions that increase the risk of or vulnerability to negative outcomes [6]. These may include behaviours, circumstances, or elements that would create an environment conducive to gender inequality. Pre-existing gender inequalities place women and men differently at risk when an outbreak impacts their livelihoods [5]. Further, gendered risk exposure, risk perception, and handling are dissimilar between men and women [7]. Thus, the pandemic poses multiple risk factors, such as further entrenchment of pre-COVID attitudes, which have hindered women’s progress. These risk factors have significant implications for gender equality, both during the pandemic and in the subsequent recovery process. Identifying and understanding the gendered risk factors of the COVID-19 pandemic can direct policymakers as they pursue gender-responsive policy making and budgeting. Moreover, the policymakers should accelerate their efforts to re-establish the path towards a more gender-equal society [4].

Crises such as famine, war, natural catastrophe, or disease outbreaks are all well documented, emphasising the effect of women’s vulnerability on the worsening of gendered risks [8]. A vulnerability approach to disasters suggests that “inequalities in exposure and sensitivity to risk and inequalities in access to resources, capabilities, and opportunities systematically disadvantage females, rendering them more vulnerable to the impacts of disasters” [9] (p. 551). This leads to a “gendered disaster vulnerability” [10].

Fineman’s theory of vulnerability emphasises that all human beings are vulnerable and prone to dependency (both chronic and episodic), and the government, therefore, has a corresponding obligation to reduce, ameliorate, and compensate for that vulnerability [11]. Thus, Fineman theorises that in order to meet its obligation to respond to human vulnerability, the government must provide equal access to the “societal institutions” that distribute social goods such as health care, employment, and security. The current study takes a vulnerability approach for analysis. Thus, we argue that a crisis creates gendered vulnerabilities and, conversely, a vulnerability approach is needed to mitigate the gender inequality that arises from a crisis.

In this article, we bring to light the gendered risk factors and how they pose as risk factors for gender equality by providing a comprehensive overview of the multiple areas in which women face difficulties and challenges due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, the research question of the study is: What are the key gendered risk factors of the pandemic and how do these impact gender equality negatively during the pandemic?

Through a systematic literature review, the gendered risk factors for females and girls were identified under the critical areas presented by UN Women on gender equality in a global context. UN Women [1] provide information on gender data and the assessment of progress towards gender equality in six critical areas: (a) population and families; (b) health; (c) education; (d) economic empowerment; (e) power and decision-making; and (f) violence against women and the girl child. This study takes a vulnerability approach to analyse how the pandemic continues to deteriorate women’s empowerment and gender equality.

2. Gender Equality in the Pre-COVID World

Although there are various definitions and approaches to the meaning of gender, the approach adopted by Connell [12] is most relevant for our purpose. Connell refers to the pronounced vulnerabilities of women especially in the context of domestic violence, which as Connell [12] has pointed out, mostly remains unreported (even today, and especially exacerbated by the pandemic). Connell [13] emphasises that gender is a crucial dimension of personal life, culture, economics, and institutions. Using yet questioning the conventional societal definition of men and women based on appearance, Connell [13] identified the unequal impacts and inequalities associated with gender (being/appearing as a man or a woman) during the pandemic. Thus, this simple yet questioning definition of gender as being a man or a woman fits very well in recognising the various risk factors encountered by women during the pandemic.

The Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action remains the most comprehensive road map for advancing women’s rights globally. It is the agenda for women’s empowerment that aims to share power and responsibility that should be established between women and men at home, in the workplace, and in the wider national and international communities. Equality between women and men is a matter of human rights and a condition for social justice and is also a necessary and fundamental prerequisite for equality. By adopting the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in 2015, member countries reaffirmed, in Sustainable Development Goal 5, that gender equality is central to the achievement of sustainable development for all by 2030.

Gender equality or equality between women and men refers to the:

- “equal rights, responsibilities and opportunities of women and men and girls and boys. Equality does not mean that women and men will become the same but that women’s and men’s rights, responsibilities and opportunities will not depend on whether they are born male or female. Gender equality implies that the interests, needs and priorities of both women and men are taken into consideration—recognising the diversity of different groups of women and men. Gender equality is not a ‘women’s issue’ but should concern and fully engage men as well as women. Equality between women and men is seen both as a human rights issue and as a precondition for, and indicator of, sustainable people centred development” [14] (p. 1).

The year 2020 marked the 25th year since the member countries adopted the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action. No country has fully accomplished the Beijing agenda and it remains elusive. However, it is important to recognise the limited progress made by the countries in achieving gender equality in the past quarter century before the COVID-19 pandemic hit the world. The United Nations World’s Women 2020 trends and statistics [1] have been generated using data from 38 countries on six critical areas that have been identified as the foci regarding COVID-19 impacts. These are: (a) population and families; (b) health; (c) education; (d) economic empowerment; (e) power and decision-making; and (f) violence against women and the girl child. Provided below is very brief statistical background information on the above areas as derived from the UN Women Report 2020 [1].

- (a)

- Population and families

By 2020, it has been identified that women outnumber men in older ages due to a biological advantage, but overall, there are 65 million less women in the world. There has been a reduction in child marriages, and in recent times, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, they stood at 20%.

- (b)

- Health

There has been a 38% decrease in the maternal mortality ratio, an 81% increase in births attended by skilled health personnel, and 77% of women aged 15–49 have had their family planning needs met with modern contraception. A total of 50% of women were able to decide on health care and contraceptive use and could say no to sexual intercourse.

- (c)

- Education

By 2020, gender parity regarding enrolment in primary and secondary education had been achieved. A total of 41% of women compared to 36% of men participated in tertiary education. The proportion of women in STEM stood at 35%. Only 30% of women were classified as researchers, 41% of women complete secondary school compared to 48% of men, and women’s use of the internet had been around 48% compared to 58% for men.

- (d)

- Economic empowerment

By 2020, only 50% of women participated in the labour market compared to 75% of men. Southern Asia, Northern Africa, and Western Asia have seen women’s participation at below 30%. The main barriers identified pre-COVID had been family responsibilities and unequal distribution of unpaid domestic and care work. Statistics point out that 82% of women living alone participate in the labour market, compared to 64% living with a partner and 48% living with a partner and children.

- (e)

- Power and decision-making

Women occupied 25% of parliamentary seats by 2020. In 2020, one in five ministers was a woman. A total of 28% of managerial positions were held by women and 18% of CEOs were women by 2020. Only 13% of police officers were women.

- (f)

- Violence against women and the girl child

Even before COVID-19 disrupted the world, domestic violence was one of the major human rights violations; 2019 recorded approximately 243 million women and girls worldwide aged 15–49 who may have been subjected to sexual or physical violence by a close partner [15].

By 2020, one third of women experienced physical and or sexual violence by an intimate partner. Susceptibility to violence has the potential to increase for older women at the hands of grown children while being at risk of violence from domestic partners. As of 2020, around 137 women are killed daily by a member of their family, globally. A total of 80% of intimate partner homicides have been women. A very low percentage, only 18% of women aged 18–49, have formally reported intimate partner violence. There are many reasons why victim–survivors do not report the acts of violence they encounter [16]. Victims may fear they will not be believed or will be victim-blamed. Some victims are afraid they will lose custody of their children or will lose financial support. Some are concerned about the stigma that this may bring to their family or they are worried that society will judge them. Many victim–survivors fear they will be unsafe after reporting the abuse. Additionally, in some instances, the victims are unaware of where to report and reach out for assistance.

UN Women [1] have identified key factors of discrimination and inequality that result in gender-based violence. These factors are discussed below. These factors have become more pronounced during the pandemic.

Community-related factors: These include harmful gender norms that favour male privilege and limitations placed on women’s autonomy, high levels of poverty and unemployment, high rates of violence and crime, drugs, alcohol, and weapons.

Societal factors: These include discriminatory laws in relation to property ownership, marriage, divorce, and child custody, reduced levels of women’s employment and education, absence or lack of enforcement of laws addressing violence against women, and gender discrimination in institutions such as relating to access to health services.

Interpersonal factors: These include high levels of inequality in relationships, male-controlled relationships, dependence on partners, men’s multiple sexual relationships, and men’s use of drugs and harmful use of alcohol.

Individual factors: These include childhood experiences of violence and/or exposure to violence, mental disorders, and attitudes that support or justify violence as normal and acceptable.

Prior to the pandemic, women were already facing a high risk of violence, especially from intimate partners, low levels of representation in positions of power, reduced participation in paid labour, and only half of the women in the world had access to health care and contraception. Improvements in relation to access to education and women’s safety (for example, from genital mutilation and child marriages) have occurred due to years of attention and efforts from international bodies such as the United Nations and from civil society involvements, as well as from serious implementation of government policies. Such efforts often require direct intervention by relevant bodies and access by women. Policies, for example, to prevent or redress domestic violence impacts have required dedicated resource allocation. On a sociological and global level, structural violence where men have held the majority of powerful positions and retrograde gender roles have dominated [17] prior to COVID-19.

Box 1 presents a snapshot of the important gains in gender equality since the adoption of the Beijing platform for action in 1995 [18].

Box 1. Gender equality review 25 years after Beijing.

- LAWS: Over the past decade, 131 countries enacted 274 legal and regulatory reforms in support of gender equality.

- EDUCATION: More girls are in school—parity in education has been achieved on average, at the global level, yet large gaps remain across and within countries.

- MATERNAL MORTALITY: The global maternal mortality ratio is still high (211 deaths per 100,000 live births) but has fallen by 38% between 2000 and 2017.

- POLITICS: One in four seats are held by women in national parliaments.

- POVERTY: Globally, women aged 25 to 34 are 25% more likely than men to live in extreme poverty (living on less than USD 1.90 per day).

- UNPAID CARE AND DOMESTIC WORK: Women on average perform three times (4.1 h per day) as much unpaid care and domestic work as men (1.7 h per day), with long-term consequences for their economic security.

- LABOUR FORCE PARTICIPATION: The gender gap in labour force participation among adults aged 25 to 54 has stagnated over the past 20 years, standing at 31%.

- GENDER PARITY IN THE WORKPLACE: Women are paid 16% less than men and only one in four managers are women.

- ACCESS TO FINANCE: Share of women and men with an account at a financial institution—women 65% and men 72%.

- YOUTH: 31% of young women aged 15 to 24 are not in education, employment, or training in 2020, more than double the rate for young men (14%).

- VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN: 18% of ever-partnered women aged 15–49 experienced sexual and/or physical violence by an intimate partner in the previous 12 months.

- CLIMATE JUSTICE: The climate emergency will most affect those with limited access to land, resources, or the means to support themselves. Globally, 39% of employed women are working in agriculture, forestry, and fisheries but only 14% of agricultural landholders are women.

- ACCESS TO JUSTICE: In most countries with data, less than 40% of women who experience violence seek help of any sort, indicating barriers and a lack of confidence in the justice system.

- HEALTH: 190 million women of reproductive age (15 to 49) worldwide who wanted to avoid pregnancy did not use any contraceptive method in 2019.

Adapted from: UN Women, 2020, p. 4,5 and created by authors [18].

3. Theoretical Lens—The Vulnerability Approach

3.1. Vulnerability during Disaster Situations

A disaster occurs when a significant number of vulnerable people experience a hazard and suffer severe damage and/or disruption of their livelihood system in such a way that recovery is unlikely without external aid [19]. Vulnerability is the susceptibility to harm [20]. Vulnerability is defined as “the characteristics of a person or group and their situation influencing their capacity to anticipate, cope with, resist and recover from the impact of a disaster” [21] (p. 11). He further states, “the risks involved in disasters must be connected with the vulnerability created for many people through their normal existence”. As [22] (p. 14) argues, “there are no generalized opportunities and risks in nature, but instead, there are sets of unequal access to opportunities and unequal exposures to risks which are a consequence of the socio-economic system”. That is, “vulnerability, captures the differential exposure to risks and capacity to cope with risks systematically attributed to people across space and time, which, together with other attributes such as ethnicity or class, are often functions of an individual’s gender” [9] (p. 552).

Prior research has found that, in disaster situations, women are affected more than men and women’s needs are mostly ignored [23]. Many factors are part of the cause in relation to increasing vulnerabilities among women during disasters [23]. These factors can be broadly classified into three main categories [9]. Firstly, the biological and physiological differences between men and women can hinder women’s responses to disasters. That is, for example, during a natural disaster such as a tsunami or a hurricane, a woman will be more easily swept away by wind or water since the majority of women are less robust than their male counterparts. This situation can be more difficult for women who have low mobility in the final stages of pregnancy and may face difficulties in self-rescue. Secondly, social norms and role behaviour may lead to a behaviour of women that increases their vulnerability in the immediate course of the disaster. Women’s roles in many countries are to care for children and the elderly as well as the family’s domestic property, which hinders their self-rescue efforts mainly during a natural disaster. Women’s dress codes can limit their ability to move swiftly, while behavioural restrictions can hamper their ability to relocate without the consent of a male relative such as their husband, father, or brother. Thirdly, there will be a shortage of resources for basic needs as well as a temporary breakdown of social order after a disaster. This may then create competition leading to gender discrimination that may exacerbate new forms of discrimination. Many disaster researchers state that relief efforts are entirely managed and controlled by men in most countries, excluding women, their needs, competencies, and experiences from contributing to these efforts [9].

However, the above factors may not impact women equally. It is not realistic to consider women as a homogenous vulnerable group. Instead, their unique intersectional identities combine to result in unequal outcomes during and after a disaster. Intersectionality (the way an individual’s multiple identities interact to shape his or her experiences [11]) hence provides a critical lens to explore the interconnected identities of individuals and populations based on race, class, caste, ethnicity, gender, and socio-economic status, among other characteristics [24].

Hamidazada et al. [25] have provided additional factors that exacerbate women’s vulnerabilities in disaster situations. These other factors include a lack of social connections, unequal power relations, limited knowledge and skills, rigid gender roles, inadequate access to health services, minority nationality and language status, informal employment status, patriarchal family structure, the gendered burden of caregiving, limited or absent community support, and more illiteracy.

3.2. Theory of Vulnerability

COVID-19-generated vulnerabilities specifically relating to women can be understood better through a deeper understanding of the human condition of vulnerability. This understanding has been undertaken through Fineman’s [26] conceptualisation of vulnerability. Fineman refers to conditions such as those developed during the pandemic as “inescapable inequality”. Fineman has created underlying links between vulnerability, dependency, social institutions, relationships, and state responsibility. The state is theorised as the legitimate governing entity that needs to undertake the responsibility to monitor social institutions to facilitate the enhancement of individual and social resilience. Vulnerability theory requires a refocusing of attention, raising of new questions, challenging of established assumptions about responsibilities, and addressing of social relationships based on inequality.

Kohn [11] states that the theory explains the basis for comprehensive social welfare policies and that vulnerability can replace group identity (e.g., race, gender, poverty) as a basis for targeting social policy. This, in turn, has a greater appreciation for the impact of intersectionality. The theory proposes that vulnerability is inherent to the human condition and that governments, therefore, have a responsibility to support vulnerability by ensuring that all people have equal access to the societal institutions that distribute resources. Thus, the theory provides an alternative basis for defining the role of government and a justification for comprehensive social welfare policies [11].

Human vulnerability is the result of dependence on social relationships [26,27]. Fineman makes an interesting point that looking at inequality in circumstances such as those created during the pandemic would perhaps not be the best approach because of inevitable inequality. Vulnerability theory requires a greater focus on individual liberty and the government’s role in enhancing it [11]. Since vulnerability is an inherent human condition, it becomes the government’s responsibility to ensure that people have equal access to societal institutions that distribute health care resources [11]. The theory also addresses the state’s responsibility to extend protections of older adults as older adults are less capable of protecting their own interests [11]. This has been identified as a significant prerogative in relation to lockdowns and a limited number of visitors to aged care facilities: the protection of the most vulnerable, that is, older populations. As identified earlier, this state initiative can also be considered as being a more gendered vulnerable protection measure as there are more females in older ages compared to males. Nevertheless, such protective measures have been more prevalent in Western nations and have not been implemented in countries such as India, where vulnerabilities of the elderly, including elderly females, are much greater. This is mainly due to weak family, health, and social welfare systems in developing countries [28].

4. Research Method

4.1. Data Collection

A systematic literature review was carried out of existing empirical, theoretical, and conceptual literature in order to identify the key gendered risk factors (for females) encountered by women and girls during the pandemic. The research question of this study is: What are the key gendered risk factors of the pandemic and how do these impact gender equality negatively during the pandemic?

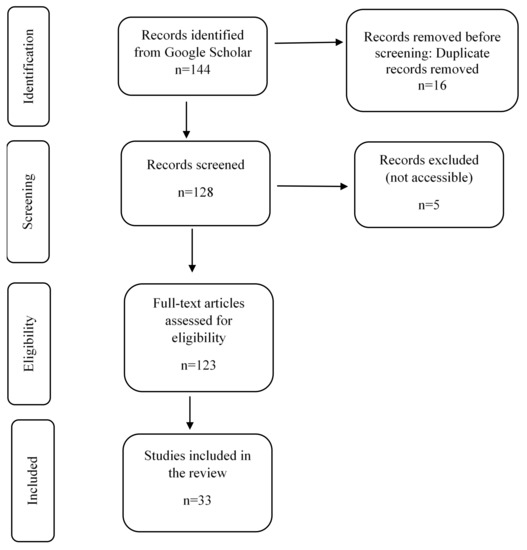

In conducting this study, four steps (identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion) of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) [29] procedure were adopted. PRISMA is beneficial for the critical appraisal of published systematic reviews, which consists of a four-phase flow diagram to guide evidence-based systematic reviews and meta-analyses [29].

The identification step, which is the first step, involves searching for relevant academic and non-academic articles to be included in the review. Google Scholar was used in identifying relevant articles. The search string focused only on two words that were included in the title of the article: “GENDERED” “COVID-19”. Articles that were published during 2020 and 2021 (until 15 August 2021) were considered. It identified a total of 144 articles, with titles consisting of the two terms “GENDERED” and “COVID-19”.

The titles of the articles were systematically recorded in an Excel worksheet based on the word “GENDERED” and the next immediate word following “GENDERED”. For example, “gendered impact”, “gendered divisions”, “gendered dimensions”, “gendered effects”, etc. There were 52 gendered themes. The accessibility of the article and whether the article is an academic article or not was also recorded. Duplications and articles that were not accessible were removed from the list. Non-accessible articles were mainly books or book chapters. Additionally, the articles were screened within the search results and added to the total records screened.

In the second stage, abstracts of the articles were screened. Jurisdiction to which the article was related was recorded. The geographic areas of the jurisdictions are represented as per M49 standard, which is used by the Statistics Division of United Nations in its publications and databases (https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49, accessed on 20 August 2021). Articles that addressed the gendered issues in multiple jurisdictions or in a global context were considered for this study. These articles were included under the “global” criterion. Thus, 33 articles were considered for this study. The whole process is presented in the PRISMA flow chart in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Process of document identification and selection (PRISMA flow chart).

In addition, during the second stage, the articles were categorised based on the six critical areas highlighted by the UN Women 2020 report: (a) population and families; (b) health; (c) education; (d) economic empowerment; (e) power and decision-making; and (f) violence against women and the girl child. When the relevant information was not available in the abstracts, the research method section of the article was screened to obtain the jurisdiction and to determine the categorisation. When multiple categories were discussed and analysed in articles, they were recorded under each of the six criteria.

4.2. Data Analysis

The 33 eligible and identified publications were read in order to understand the gendered risk factors that would impact gender equality during the pandemic. Risk factors that were identified were analysed and presented under the six critical criteria on gender equality identified by the UN Women 2020 report, which are: (a) population and families; (b) health; (c) education; (d) economic empowerment; (e) power and decision-making; and (f) violence against women and the girl child.

5. Results

5.1. Family and Population

The unprecedented impact of COVID-19 on schools has underscored their critical role, not only for children’s well-being, but also for parents, especially for women, who spend a major proportion of their time on caregiving in families despite working for pay nearly on par with their spouses or partners [30]. The situation is worse for single parents who have to manage both paid work and caregiving. In many developed countries, school closures are a major institutional constraint on families to provide extra childcare. Schools not only deliver education for children in some countries but also offer an expansive infrastructure of care, especially for primary school kids [30]. Extensive school closures during the pandemic have caused many heterosexual-couple families to return to the conventional norms of fathers working and mothers caring for kids [28], as care is deemed to be supplied predominantly by women during the pandemic [31]. This not only increased the amount of time that women had to spend on childcare but also required women to facilitate home-schooling, which has been a novel experience for many—these additional responsibilities lay on the shoulders of women with zero payment in return.

Further, due to continuous lockdown, families have been unable to access informal care facilities for their kids through grandparents and other close networks. This is complicated by the limitations of care support provided by grandparents, as they are at higher risk for severe illness from COVID-19 and have to minimise contact with others, especially with children who can be asymptomatic and carry the potential to spread the virus without being aware of it [32]. Evidence from Germany, for example, shows that the share of grandparents providing care dropped from 8.3 percent to 1.4 percent since the epidemic started [31]. As part of reduction measures, older people have been advised to stay at home, making them depend on family, friends, or social care workers to deliver groceries and vital medications to them. Much of this support has been part of women’s responsibilities [31].

While there is no comprehensive evidence on the time use of spouses since the onset of the crisis, emerging research on the impacts of the COVID-19 crisis on unpaid care work shows mixed findings. There is a pattern towards the re-traditionalisation of care in the household. For example, a recent study by [33] finds that, among the population working from home in the USA, UK, and Germany during the lockdown, women spend significantly more time caring for children as well as home-schooling relative to men. Wenham et al. [34] state that the closure of schools to control COVID-19 transmission in China, Hong Kong, Italy, South Korea, and beyond might have a differential effect on women, who provide most of the informal care within families, with the consequence of limiting their work and economic opportunities.

Laster and Wright [35] emphasise that women of colour have become overburdened with invisible labour during the pandemic that can impact their well-being. The combination of care and distance-learning responsibilities, along with the stresses of either working or being out of work, has profoundly affected women of colour during the pandemic. However, things may differ among countries.

5.2. Health

The gendered risk factors identified through the systematic literature review related to the criteria of health are discussed below. They mainly concern: working in COVID-19-exposed environments; reproductive health and pregnancies; ethnicity; social norms; limited access to health care; domestic violence-related brain injuries; and mental disorders.

Vora et al. [36] claim that women tend to be more impacted in pandemics due to many risk factors, including an increased biological vulnerability. Their role as primary caregivers to sick relatives, social disadvantages, and the fact that most frontline health workers are women put them at greater risk. Therefore, during the pandemic, evaluations of the complex relationship between biological and behavioural risk factors in gendered analyses are much needed [36].

It is reported as per the Global Health 50/50 COVID-19 data tracker, where data on infection rates among health workers are available in countries such as Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United States of America, that the majority (70% or more) of those who are infected are women [15]. These data reflect the rate of exposure of women in higher-risk environments where they contact people who are already infected and the gendered distribution in the health workforce [37]. Similarly, data from the State Council Information Office in China state that more than 90% of health care workers in Hubei province are women, emphasising the gendered nature of the workforce in the health sector and the risk that predominantly female health workers encounter. This reiterates women’s and men’s differential vulnerability to infection and exposure to the outbreak [34].

The pandemic has also posed challenges for and exacerbated inequities in women’s reproductive health [38]. A number of jurisdictions deemed abortion a nonessential service that could be postponed, while some jurisdictions overtly protected access to abortion. Due to the pandemic, far fewer women want to become pregnant and want to delay pregnancy or have fewer children during the pandemic. However, women reported a lack of access to sexual and reproductive health services, including contraceptive methods and maternal and child care in emergency situations [37,38,39].

It is also stated that PCR testing is not available for some vulnerable people, including displaced populations, non-citizens, migrants, and refugees, who are largely represented by females and girls [40]. For example, in Bangladesh, testing facilities are limited to the capital, Dhaka, which is 400 km away from the world’s largest refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar. Apart from this, there are other vulnerable people who are already suffering from diseases such as HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis. They find their treatment interrupted by digressions of resources, while their pre-existing conditions make them more susceptible to COVID-19 [37,40].

The restriction on movement during lockdown imposed by different jurisdictions has triggered mental disorders among females such as depression, excessive aggression, suicidal tendencies, etc., that have directly impacted mental health [41]. Women who are frontline health workers, caregivers, and community members fear becoming infected or infecting others and are more susceptible to stress and trauma relating to the outbreak [40].

Valera [42] claims that during the pandemic, due to the escalation of intimate partner violence, women who may want to escape may not have the option due to mitigation strategies or exposure fears, which would result in more severe forms of abuse, including traumatic brain injuries. Intimate partner violence and COVID-19 together have enhanced a tendency towards serious trauma from domestic violence. Valera emphasises that [42] urgent attention is required in this regard, and if not, there will be a high risk of the eruption of another pandemic of women who are struggling to live with intimate partner violence and the effects of undiagnosed traumatic brain injuries.

Schönpflug [43] claims that the consequences of systemic gendered and classed racism on labour markets with limited access to jobs that can be performed remotely and jobs with great exposure to other people and chronic stress result in more health inequalities for black, indigenous, and people of colour (BIPOC), who are especially vulnerable to the virus, including women and girls. In addition, women and girls in certain humanitarian settings are the last to receive medical attention when they become sick due to prevailing social norms. These social norms hinder females from accessing testing and timely treatment for COVID-19, particularly those who are already stigmatised, such as IDPs and refugees, members of certain ethnic or racial groups, or those of different sexual orientations [40]. Further, it is unlikely that women may have access to hospital-based care in some situations, particularly where there is no financial support for their own use of health services. Such inequalities in service access may underlie the differences seen in the global and national data showing lower rates of COVID-related hospital admissions among women [37].

5.3. Education

Schools are closed globally to prevent the spread of the COVID-19 virus. According to UNESCO [44], school closures have sent about 90% of all students out of school. Among them, more than 800 million are girls. A substantial number of these girls live in the least developed countries, where receiving an education is already a struggle.

Akmal et al. [45] carried out a survey among organisations that provide educational services in 32 different countries operating in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, the Middle East, North Africa, and Latin America. Nearly 70% of the respondents stated that girls are more likely to be adversely affected by the COVID-19 school closures than boys. Almost 38% of the respondents believe that girls are dropping out and not coming back to school as a critical concern. Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia suggests that parents may prioritise sending boys back to school instead of girls. This raises concerns about whether girls will come back to school at all.

Risk factors such as exposure to gender-based violence, early marriage, and pregnancy may also hinder girls from returning to school [45]. Some respondents believe that the gendered cost of school closures outweighs the benefits, which may impact increased vulnerability and lack of safety for girls. Muller and Nathan [46] emphasise sexual and reproductive health aspects, where teenage girls might disproportionately drop out of school due to an increased risk of sexual exploitation.

Further, a disproportionate increase in unpaid household work during school closure would be another risk factor that girls might spend less time studying or might even drop out of school compared to boys. Parents, who undermine the value of girls’ education, would keep their daughters at home even after schools reopen. In certain circumstances during the pandemic when caregivers are missing in the household due to work, illness, or death, typically, the girls have to replace the work (fully or partially) performed by the missing caregiver. Therefore, with the current COVID-19 pandemic, there will be more girls than boys helping at home, lagging behind with studying, and dropping out of school. These factors may widen the gender gaps in education and girls’ empowerment, diminishing any progress already made, particularly in developing countries [45].

5.4. Economic Empowerment

Women’s pre-existing vulnerabilities are exacerbated in the wake of disasters. The lockdown and travel restrictions have coerced women to leave the labour force voluntarily [39]. The closure of schools increased the work at home regarding children’s online schooling and physical and social nourishment. In addition, the responsibility of caregiving for family members and elderly parents lies primarily with women.

At the same time, COVID-19 has drastically impacted sectors with a high share of female workers; many women have been left without jobs and income, prompting them to stay at home and accept more domestic responsibilities [31]. This has led to widening gender gaps in labour force participation, wages, and unpaid care work. Additionally, the pandemic-related layoffs of many companies have focused on female employees [31]. All these factors have potentially widened the economic inequality gap between men and women.

In certain situations, with the increased family burdens, women could work a lower number of hours, resulting in reduced wages. It is stated that women and girls have even less self-directed time, including spending time on their own paid work. These risk factors, along with the potential loss of income due to the death of other household income earners, could lead to a long-term and widespread economic impact of COVID-19 on women and girls [40].

More women than men are involved in the informal economy and informal employment, which are prone to job insecurity. Populated marketplaces that are part of the informal economy were closed at the early stage of the outbreak to prevent the spreading of the COVID-19 virus. These factors adversely impacted women since they play critical roles as processors, traders, and entrepreneurs in markets, thus limiting their working opportunities [47]. Globally, females earn a lesser income than their male counterparts. Hence, income losses because of the global coronavirus pandemic would increase the inequalities between them. Over 74% of women in sub-Saharan Africa are in non-agricultural informal employment [48]. During the pandemic, this situation has been a significant vulnerability factor for women. Lockdowns, travel restrictions, stay-at-home measures, and market closures meant that most of these women employed in the informal sector of the economy were temporarily out of employment as many of them could not engage in their usual lifestyles. Further, travel restrictions cause financial challenges and uncertainty for female foreign domestic workers, who travel in Southeast Asia between the Philippines, Indonesia, Hong Kong, and Singapore [34].

Cahn and McClain [38] highlight that the gendered patterns intersect with a “racial justice paradox” as stated by Catherine Powell “the colour of COVID”. That is, people of colour are overrepresented among both the unemployed and among essential workers being asked to take risks at work. Additionally, they are mainly females—“the gender of COVID”. In the USA, women of colour, particularly those who are Black, Latina, and Native American, are at the intersection of the inequities exposed by the pandemic, a consequence that replicates vulnerable intersectional inequalities [38]. These women represent a major proportion of the female workforce in low-paid and undervalued frontline jobs, including care work that is vital to the economy but unable to be performed from home.

Laster and Wright [35] state that the New York Times exposé on essential workers in the pandemic reported that one in three jobs held by women is designated vital, yet that does not mean they are compensated for their necessary labour, even if one is a frontline health care worker. The authors note that of the 5.8 million people working in health care jobs that pay less than USD 30,000 a year, half are non-white, and 83% are women. Women of colour make up two-thirds of home health care workers, and 30% of them are Black women who are licensed practical and vocational nurses [35]. This further enhances the gender vulnerability of women of colour. The health care workers who have died during this COVID-19 pandemic were largely women of colour [49]. For example, nurses of Filipino descent account for 31.5% of the workforce’s COVID-19 deaths, yet they represent only 4% of the workforce [49]. Women of colour health care workers are less well compensated in their jobs and are less well protected in combating COVID-19. Thus, structural gendered racism acts as a risk factor for COVID-19 for women of colour through their occupational status.

5.5. Power and Decision-Making

Women were less likely than men to have power in decision-making around the outbreak, and their needs were largely unmet. There is also a lack of representation of females in the decision-making of COVID-19 [39], making them less empowered and widening the gender inequality gap.

Wenham et al. [34] state that the differences in power between men and women meant that women did not have autonomy over their sexual and reproductive lives during the pandemic. The situation was heightened by women’s inadequate access to health care and insufficient financial resources to travel to hospitals for check-ups for them and their dependants, despite them undertaking most of the community trajectory control activities. The resources for reproductive and sexual health were diverted to emergency response, contributing to a rise in maternal mortality in some developing countries. Reproductive health services, such as contraception and abortion services, have been either shut down or rendered inaccessible due to the pandemic [34]. Some community organisations reported on their websites regarding the reduction in manufacturing and shortages of contraceptives. Many community family clinics were shut down in the rural areas of developing countries. The lack of personal protective equipment and transportation to the clinics limited reproductive health services. The UNFPA (2021) [49] reported that measures for the containment of COVID-19 have led to 47 million women in low- and middle-income countries losing their access to contraception. In India itself, about 3 million unintended pregnancies are predicted to occur as a result of the pandemic and lockdown. On a global scale, an estimated 7 million unplanned pregnancies are expected. To further exacerbate the situation, many of these women will face the early stages of their pregnancy during peak times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Many of them have limited decision-making ability in their sexual and reproductive lives [38].

The power of women in decision-making had been impacted during the pandemic at different levels and professions too. Lange [50] reports that in October 2020, a scientific congress was held under the patronage of the German Society of Cardiology. Due to the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, the meeting was rescheduled to be held virtually. The organising committee decided to shorten the schedule substantially. Thus, 37 of 82 speakers and chairs were informed a few days before the congress that their session was called off. Out of the cancelled sessions, 29 (41%) were male speakers (95% CI 29–53%), whereas eight (73%) of 11 were female speakers (39–94%), bringing the female speaker participation down from 13% to 7% of speakers. Lange [50] states that this scenario highlights how important it is for organising committees of scientific meetings to have a diverse gender-balanced representation at a time when resources are scarce.

On a different aspect, Park [51] investigates whether and how gendered leadership makes a difference in dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic. He states that women-led countries show epidemiologic patterns different from male-led countries. Using daily panel data over the first half of the year 2020 across OECD countries, he investigates whether gendered leadership makes a difference in dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic, and how the effect varies by the maturity of the democracy and gender representation in parliament and government. This country comparison seeks to explain the initial trajectories of the pandemic with the lens of gendered leadership embedded in democratic and representative institutions. He finds that women-led countries show epidemiologic patterns different from male-led countries. The effect of gendered leadership was contingent on the maturity of democracy and the degree of gender representation in both parliament and bureaucracy. Cahn and Clain (2020) [38] also claim that the pandemic situation would have been different if there were more women in leadership positions. Currently, the consequences of the pandemic have been exacerbated by political leadership modelling, which predominantly reflects an approach of masculinity.

5.6. Violence against Women and the Girl Child

Pandemics such as COVID-19 are a crisis, and during such times, violence against women and girls increases [1]. The United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, on 6 October 2020, referred to the “horrifying surge in domestic violence” aimed at women and girls linked to lockdowns by governments globally. Displacements, loss of jobs, school closures, lockdown, financial stress, and a lack of communication have forced women and girls to stay for more extended periods with their abusers. These gendered risk factors are discussed below.

During the pandemic, due to financial strains from loss of employment and income, men, who have been undertaking the traditional gender role of providing for the family, may experience a sense of inadequacy, uncertainty, and loss of control, resulting in the provoking of power assertion [1]. This urge can be acted on through violence towards partners and children. Quarantine, isolation, physical distancing, and increased domestic and care burdens are causing increased stress, anxiety, and mental health problems. Conflict can escalate to abuse and can be exacerbated by excessive alcohol consumption. The pandemic has resulted in risk mitigating services being unavailable or strained and restrictions on mobility, work, school, social engagement, and empowerment initiatives being interrupted.

There has been a dramatic rise in gender-based violence during the pandemic. UN Women (2021) [1] has stressed that one in three women was experiencing physical or sexual violence worldwide prior to the pandemic. Since the outbreak, all types of violence against females have increased. Most of the violence is perpetrated by current or former husbands or intimate partners. In some countries, reported violence has increased five-fold (UN Women, 2021) [1]. Gendered violence is experienced to a higher degree in low- and lower–middle-income countries where the pandemic is expected to have more dire impacts. There are also more occurrences of gendered violence due to severe constraints on preventative and redress resources.

Akmal et al. (2020) [45] carried out a survey among organisations that provide educational services in 32 different countries operating in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, the Middle East, North Africa, and Latin America. Respondents from Bangladesh suggest that violence against women has increased during COVID-19 lockdowns, partly due to poverty-related stress and prolonged periods of staying at home. Financial insecurity and alcohol consumption patterns of the abusers are other concerns.

Girls’ exposure to gender-based violence at home during school closures is a vital concern. Akmal et al. (2020) [45] reflect that services provided by education organisations stretch well beyond teaching and learning. Schools and education programs serve as safe havens for girls against physical violence or harmful traditional practices such as child marriage. Schools also serve as platforms providing health services, such as general vaccinations, which have now been deferred due to school closures. Fuhrman et al. [40] further state that girls may have less access to health, hygiene resources, and their caregiving burdens may increase. Some children are at risk of becoming separated from their parents or caregivers, who may be hospitalised or die.

Standish and Weil [52] state that if domestic violence increases, the rate of femicide will increase globally. Femicide is an extreme form of domestic violence and is most frequently the result of intimate partner abuse. The violation of women by their partners can be short or long term. Sometimes, if the victim complains to the police or authorities about domestic violence, the abuse can result in femicide.

In Spain, homicides connected with domestic violence have become regular occurrences. They are likely to increase in the future if the future remains uncertain [1]. In the US, some abusers spin the situation into a trap. They do this by carrying out actions such as threatening to leave their victims to COVID-19 pandemic rules, banning hygienic measures, and threatening to ban the victim from accessing health care resources in case they catch the virus [1]. These reports are uncertain about the actual number of women violated as the housing policies are still in place worldwide. This also shows that most women lock onto their attackers and cannot communicate with the outside world. Due to the lack of facilities, abuse against women and children in rural areas goes undisclosed in some situations.

Countries such as Brazil, China, France, Italy, and the USA reported unprecedented increases in domestic violence reports. The emergency calls received from women who were victims of domestic violence in Europe increased by around 60% [53]. In France, there was an increase of over 30% in domestic violence incidents. The numbers tripled in China [1]. As reported by Australian practitioners, there was an increase in the number of cases related to first-time family violence [54]. It was revealed that people mentioned “domestic violence” during the lockdown more than other periods in analysing tweets/comments on domestic violence [55].

6. Discussion and Conclusions

The risk factors of a disaster, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, are not gender-neutral [2]. Instead, the disaster impact is contingent upon the vulnerability of affected people, which differs across economic class, ethnicity, gender, and other factors [9]. The pandemic threatens to reverse hard-won gains in gender equality, exposing women’s vulnerabilities based on their pre-pandemic social, economic, and political situations [4]. Thus, the pandemic poses multiple risk factors that have significant implications for gender equality, both during the pandemic and in the subsequent recovery process. Through a systematic literature review, the gendered risk factors for females and girls during the pandemic were identified in an attempt to answer the research question: What are the key gendered risk factors of the pandemic and how do these impact gender equality negatively during the pandemic? This study takes a vulnerability approach to analyse how the pandemic continues to deteriorate women’s empowerment and gender equality.

The findings of this study were presented under the critical areas identified by UN Women on gender equality in a global context: (a) population and families; (b) health; (c) education; (d) economic empowerment; (e) power and decision-making; and (f) violence against women and the girl child.

Our findings from the systematic literature review suggest that women’s pre-existing vulnerabilities are exacerbated in the wake of the pandemic due to the gendered risk factors worsening the gender equality gap. Vora et al. [36] claim that women tend to be more impacted in pandemics due to many risk factors, including an increased biological vulnerability. Continuous lockdown and extensive school closures have increased the amount of time that women had to spend on childcare and facilitating home-schooling, in addition to the daily household responsibilities, with zero payment in return.

On the other hand, these broader implications of school closures may disproportionately affect girls by exacerbating existing gender-specific vulnerabilities and challenging progress and commitment towards gender equality and girls’ empowerment. Risk factors such as exposure to gender-based violence, unpaid household work during school closure, early marriage, and pregnancy may hinder girls from returning to school [45].

It is plausible that the pandemic will continue to exacerbate existing gaps and even result in unprecedented risk factors that impact women’s and girls’ vulnerability to COVID-19 as well as to other health conditions. Predominantly, the majority of the health care workers in many jurisdictions are females, indicating their vulnerability and exposure to the outbreak differently to men [34]. The pandemic has also posed challenges for and exacerbated inequities in women’s reproductive health [38]. Indeed, women reported a lack of access to sexual and reproductive health services, including contraceptive methods and maternal and child care in emergency situations [37,38,39]. It was found that some vulnerable people, such as displaced populations, non-citizens, migrants, and refugees, that are represented mainly by females and girls do not even have access to PCR testing [40]. In addition, women and girls in specific humanitarian settings are the last to receive medical attention when they become sick due to prevailing social norms [43].

COVID-19 has drastically impacted sectors with a high share of female workers; many women have been left without jobs and income, prompting them to stay at home and accept more domestic responsibilities [31]. Women in the informal economy and informal employment are severely impacted by lockdowns, travel restrictions, stay-at-home measures, and market closures. People of colour are overrepresented among both the unemployed and among essential workers being asked to take risks at work. Additionally, they are mainly females, revealing “the gender of COVID” effect and the enhanced gendered vulnerability of women of colour [38]. Thus, structural gendered racism acts as a risk factor for COVID-19 for women of colour through their occupational status.

There is also a lack of representation of females in the decision-making of COVID-19 [39], making them less empowered and widening the gender inequality gap. There has been a dramatic rise in gender-based violence during the pandemic against females around the world. Most of the violence is perpetrated by current or former husbands or intimate partners and involves physical, mental, and financial abuse, and in unfortunate situations this can result in femicides.

We conclude by arguing that our study’s findings support a vulnerability approach to the pandemic. The acceptance of vulnerability supports the ideology that political and economic systems need to react in a responsive and supportive way to those who are vulnerable [54]. Human beings are innately dependent on the provision of care by others as children or when ill, aged, or disabled. Hence, governments and other donor institutions need to take actions to respond to and mitigate the socio-economic consequences [56] of the pandemic through funding, budgeting, and other social protection programs, prioritising women as direct recipients of benefits while empowering them. Focus is needed on the particular medical, economic, and security needs of women in the aftermath of disasters as well as on mechanisms to ensure the fair and non-discriminatory allocation of relief resources [9].

A vulnerability approach argues that the state must be responsive to the realities of human vulnerability and its corollary, social dependency, as well as to situations reflecting inherent or necessary inequality when it initially establishes or sets up mechanisms to monitor these relationships and institutions [5]. Further, all judicial and administrative changes need to consider the gendered nature of existing laws and institutional practices that sometimes maintain, reproduce, or exacerbate gender inequalities. These changes may translate to gender-responsive policies and system improvements to support vulnerable female populations [57]. Understanding human vulnerability suggests that equality, as it tends to be used to measure the treatment of individuals or groups, is a limiting aspiration when it comes to social justice. Equality is typically calculated by comparing the circumstances of those individuals considered equals [26]. Gender and social justice need to be the new normal during the disaster recovery process. Hence, policymakers should step up their efforts to re-establish the path towards a more equal society for men and women. A responsive state is required in this regard.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.K. and P.S.; methodology, P.S.; formal analysis, T.K. and P.S.; investigation, P.S. and T.K.; data curation, P.S. and T.K.; writing—original draft preparation, T.K.; writing—review and editing, P.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- United Nations. The World’s Women 2020 Trends and Statistics. Available online: https://worlds-women-2020-data-undesa.hub.arcgis.com/ (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Jenkins, K.; Australian Human Rights Commission. The Gendered Impact of COVID-19. Available online: https://humanrights.gov.au/about/news/gendered-impact-covid-19 (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Rubery, J.; Tavora, I. The COVID-19 crisis and gender equality: Risks and opportunities. In Social Policy in the European Union: State of Play; European Trade Union Institute (ETUI): Brussels, Belgium; European Social Observatory (OSE): Brussels, Belgium, 2020; pp. 71–96. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.Y.; Inocencio, A.M. COVID-19 Is No Excuse to Regress on Gender Equality; Asian Development Bank: Manila, Philippines, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Enarson, E. Human security and disasters: What a gender lens offers. In Human Security and Natural Disasters; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Framework of Analysis for Atrocity Crimes: A tool for prevention. In United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Salvati, P.; Petrucci, O.; Rossi, M.; Bianchi, C.; Pasqua, A.A.; Guzzetti, F. Gender, age and circumstances analysis of flood and landslide fatalities in Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 1, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, H.J.; Wong, K.R.; Nguyen, K.N.; Mahamadachchi, K.N. COVID-19 and women’s triple burden: Vignettes from Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Vietnam and Australia. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumayer, E.; Plümper, T. The gendered nature of natural disasters: The impact of catastrophic events on the gender gap in life expectancy, 1981–2002. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2007, 1, 551–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enarson, E. Through women’s eyes: A gendered research agenda for disaster social science. Disasters 1998, 22, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, N.A. Vulnerability theory and the role of government. Yale JL Feminism 2014, 26, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, R. Gender and Power; Polity Press: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, R. Gender in World Perspective, 4th ed.; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UN Women. United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women, 2001 August Fact Sheet 1. Available online: https://www.un.org/womenwatch/osagi/pdf/factsheet1.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2021).

- WHO. Gender Equity in the Health Workforce: Analysis of 104 Countries. 2020. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/311314/WHO-HIS-HWF-Gender-WP1-2019.1-eng.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Scott, K. Why Victim-Survivors Don’t Report Domestic Violence. ABC Everyday. 2021. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/everyday/reasons-why-victim-survivors-dont-report-domestic-violence/100035002 (accessed on 18 November 2021).

- Mosken, A. Exberliner. When Men Lose Control. 2011. Available online: https://www.exberliner.com/features/people/when-men-lose-control (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Ajibade, I.; McBean, G.; Bezner-Kerr, R. Urban flooding in Lagos, Nigeria: Patterns of vulnerability and resilience among women. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 1714–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaikie, P.; Cannon, T.; Davis, I.; Wisner, B. At Risk: Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability and Disasters; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sapirstein, G. Social resilience: The forgotten dimension of disaster risk reduction. Jàmbá J. Disaster Risk Stud. 2006, 1, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wisner, B. At risk: Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability and Disasters, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon, T. Vulnerability analysis and the explanation of “natural” disasters. In Disasters, Development and Environment; Varley, A., Ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1994; pp. 13–33. [Google Scholar]

- Khondker, H. Women and floods in Bangladesh. Int. J. Mass Emergencies Disaster 1996, 14, 281–292. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. U. Chi. Legal F. 1989, 1989, 139–167. [Google Scholar]

- Hamidazada, M.; Cruz, A.M.; Yokomatsu, M. Vulnerability factors of Afghan rural women to disasters. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2019, 10, 573–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fineman, M.A. Introducing vulnerability. In Vulnerability and the Legal Organization of Work; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fineman, M.A. (Ed.) Vulnerability: Reflections on a New Ethical Foundation for Law and Politics; Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.: Burlington, VT, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnaswamy, B.; Sein, U.T.; Munodawafa, D. Ageing in India. Ageing Int. 2008, 32, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, C.; Ruppanner, L.; Christin Landivar, L.; Scarborough, W.J. The Gendered Consequences of a Weak Infrastructure of Care: School Reopening Plans and Parents’ Employment During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Gend. Soc. 2021, 2, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugarova, E. Unpaid care work in times of the COVID-19 crisis: Gendered impacts, emerging evidence and promising policy responses. In Proceedings of the UN Expert Group Meeting Families in Development: Assessing Progress, Challenges and Emerging Issues, Focus on Modalities for IYF, New York, NY USA, 16–18 June 2020; 2013; Volume 30, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- UNDESA. COVID-19 and Older Persons: A Defining Moment for an Informed, Inclusive and Targeted Response; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Adams-Prassl, A.; Boneva, T.; Golin, M.; Rauh, C. Inequality in the impact of the coronavirus shock: Evidence from real time surveys. J. Public Econ. 2020, 189, 104245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenham, C.; Smith, J.; Morgan, R. COVID-19 is an opportunity for gender equality within the workplace and at home. BMJ 2020, 369, 1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laster Pirtle, W.N.; Wright, T. Structural Gendered Racism Revealed in Pandemic Times: Intersectional Approaches to Understanding Race and Gender Health Inequities in COVID-19. Gender Soc. 2021, 35, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vora, K.S.; Sundararajan, A.; Saiyed, S.; Dhama, K.; Natesan, S. Impact of COVID-19 on women and children and the need for a gendered approach in vaccine development. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 16, 2932–2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, S.; Buse, K. COVID-19 and the gendered markets of people and products: Explaining inequalities in infections and deaths. Can. J. Dev. Stud. Revue Canadienne D’études Développement 2021, 42, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahn, N.; McClain, L.C. Gendered complications of COVID-19: Towards a feminist recovery plan. Georget. J. Gend. Law 2020, XXII, 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Mansoor, T. Gendered Impact and Implications of COVID-19: A Narrative Global Status-Quo Review. Life Sci. 2020, 22, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhrman, S.; Kalyanpur, A.; Friedman, S.; Tran, N.T. Gendered implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for policies and programmes in humanitarian settings. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenilmez, M.I. The Gendered Face of COVID-19: A Research Call to Action. J. Emerg. Econ. Policy 2020, 6, 44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Valera, E.M. When pandemics clash: Gendered violence-related traumatic brain injuries in women since COVID-19. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 1, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schönpflug, K. A feminist economics view on racialized, gendered, and classed effects of the COVID-19 crisis. Pandemie 2020, 27, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. COVID-19 School Closures Around the World Will Hit Girls Hardest. 2020. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/news/covid-19-school-closures-around-world-will-hit-girls- (accessed on 19 September 2021).

- Akmal, M.; Hares, S.; O’Donnell, M. Gendered Impacts of COVID-19 School Closures: Insights from Frontline Organizations; Policy paper; Centre for Global Development: London, UK, 2020; Volume 175, pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, J.E.; Nathan, D.G. Gendered effects of school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2020, 395, 1968–1970. [Google Scholar]

- Akrofi, M.M.; Mahama, M.; Nevo, C.M. Nexus between the gendered socio-economic impacts of COVID-19 and climate change: Implications for pandemic recovery. SN Soc. Sci. 2021, 1, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNICEF. Girls Spend 160 Million More Hours than Boys Doing Household Chores Everyday. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/pressreleases/girls-spend-160-million-more-hoursboys-doing-household-chores-everyday (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- UNFPA. COVID-19 Pandemic. 2021. Available online: https://www.unfpa.org/covid19 (accessed on 18 September 2021).

- Lange, B. Maintaining a gendered perspective in scientific meetings during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2020, 396, 1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S. Gendered leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic: How democracy and representation moderate leadership effectiveness. Public Manag. Rev. 2021, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standish, K.; Weil, S. Gendered pandemics: Suicide, femicide and COVID-19. J. Gend. Stud. 2021, 30, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahase, E. COVID-19: EU States Report 60% Rise in Emergency Calls about Domestic Violence. 2020. Available online: https://www.bmj.com/content/369/bmj.m1872 (accessed on 22 September 2021).

- Fitz-Gibbon, K.; Maher, J.; Elliott, K. Barriers to Help Seeking for Women Victims of Adolescent Family Violence: A Victorian (Australian) Case Study. In Young People Using Family Violence; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, J.; Chen, J.; Chen, C.; Hu, R.; Zhu, T. The hidden pandemic of family violence during COVID-19: Unsupervised learning of tweets. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e24361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, M.; Buvinic, M.; Bourgault, S.; Webster, B. The Gendered Dimensions of Social Protection in the COVID-19 Context; Center for Global Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Enarson, E.; Fothergill, A.; Peek, L. Gender and disaster: Foundations and new directions for research and practice. In Handbook of Disaster Research; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 205–223. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).