Abstract

In recent years, the study of heavy work investment (HWI) has been diversifying greatly in the various fields of application in the organizational field, for example, occupational health, human resources, quality at work among others. However, to date, no systematic review has been carried out to examine the methodological quality of the instruments designed to measure HWI. Therefore, the present systematic review examines the psychometric properties of three main measures of HWI: Workaholism Battery (WorkBAT), Work Addiction Risk Test (WART), and Dutch Work Addiction Scale (DUWAS). Five electronic databases were systematically searched, selecting psychometric articles. Of the 2621 articles identified, 35 articles met all inclusion criteria published between 1992 and 2019. The findings indicated that most of the articles were focused on reviewing psychometric properties, analyses were conducted from classical test theory, collected validity evidence based on internal structure and relationship with other variables, and reliability of scores was obtained through the internal consistency method. Of the instruments reviewed, the DUWAS is the one with the highest methodological quality. Recommendations are made for future research to address the psychometric study of these instruments based on recent advances in the field of organizational measurement.

1. Introduction

Heavy work investment (HWI) is a concept developed by Snir and Harpaz [1] who define it as the time and effort invested in work as the two central axes of HWI. Based on Weiner’s attributional framework they propose three main categories of possible predictors of HWI: background (e.g., gender, parenthood, education), internal (e.g., work addiction, workaholism), and external variables (e.g., financial needs, employer demands) [2]. Thus, the present review focuses on the possible internal predictors, i.e., work addiction and workaholism. Current theoretical proposals of HWI use the job demands–resources (JD–R) model, considering this construct as a continuum consisting of three main parts: antecedents, dimensions, and outcomes [3].

HWI is a construct that underlies many others such as work addiction, work engagement, passion for work, workaholism, among others [4]. That is, HWI is seen as a higher-level umbrella construct and that work addiction, work engagement, passion for work, and workaholism would be at a lower-level, subsumed by HWI [3]. The time invested in work consists of the use of a large number of hours, and work intensity is the effort involved in the various tasks that a person performs at the physical and intellectual level. Regarding internal predictors, work addiction presents compulsive behaviors due to the pressure received by workers [5]. Therefore, within work addiction, heavy investment of time is marked. It is important to note that HWI is not in itself a negative or positive construct, but that this will depend on the context in which it develops. Thus, a positive implication of this variable is work commitment, where the worker puts dedication and strength into his work activities [6].

Several studies have explored the relationship between workaholism and work engagement, showing significant associations [7], although with varying results, both positively and negatively [2]. In this sense, HWI has been related to greater job security, better career development opportunities, and higher salary. In parallel, HWI may also be negatively related to individual affective and behavioral outcomes that are to be avoided [8,9]. For example, workaholics tend to be associated with poorer mental and physical health, emotional and cognitive exhaustion, poor sleep habits, cardiovascular problems, poor social relationships, and work–life conflicts [10,11,12]. Thus, it is important to have tools for a correct assessment of the internal factors of HWI (workaholism or work addiction). Workaholism or workaholism includes one of the components of HWI, the heavy time investment in work, however, it does not necessarily include the other component of HWI, the intensity of work during that period [1]. Thus, workaholism or workaholism is related to one aspect of HWI.

In this regard, this review will focus on assessing the quality of three of the most widely used HWI measures reported in the literature: Workaholism Battery (WorkBAT), Work Addiction Risk Test (WART), and Dutch Work Addiction Scale (DUWAS) [13]. In addition, the definitions of standards for educational and psychological tests will be used to ensure consistency with current psychometric guidelines for instrumental studies. To date, there has not been a published study that systematically reviews research on the psychometric properties of HWI measures. This is a significant gap given the increased interest in research beyond the organizational setting. The validity of research findings is contingent on the use of tools with appropriate validity and reliability evidence that measure the constructs of interest. Therefore, the evaluation of psychometrically robust instruments through a systematic review is warranted.

The concept of validity has undergone a long evolutionary process up to the present day. In the 1985 Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing and Manuals, it is maintained that validity is a unitary concept and that the validity of a test is construct validity [14]. In the 2014 Standards, it is insisted that the term test validity is inapplicable, and therefore that of types of validity; rather, it is necessary to provide information from various sources about the purpose for which the test or measurement instrument was developed. It is reiterated that the test is not validated, but rather the inferences made from the scores of the subjects for a given purpose [15].

From this perspective, the test creator is not only responsible for the validity of the test but also the test user. Furthermore, the validity of a test is not established once and for all but is a continuous process of gathering evidence. From a scientific point of view, the only admissible validity is construct validity [16]. Therefore, the logic that underlies it and the methods used to determine it are those that correspond in general to the scientific method. Its evidence comes from various sources, which presuppose a clear definition of the construct and its dimensions or facets if these are necessary.

It is necessary to keep in mind that no study tests or validates a complete theory only concerning some of the inferences that can be derived from it. For constructs, negative results can be interpreted in three directions: the test may not measure the construct; the theoretical framework may be flawed, making it possible for incorrect inferences to be made; or the study design would not allow for proper testing of the hypotheses. These interpretations communicate poor psychometric and research theoretical training and practice, which can lead to ambiguous interpretation of negative results. Finally, it should always be kept in mind that unexpected relationships, as well as predicted ones, are part of the nomological network of the construct and provide arguments for the meaning of the scores.

Conversely, reliability is the degree to which test scores for a group of subjects are consistent in repeated applications of a measurement procedure and hence the reliability and consistency of a subject’s score is inferred [17]. It is implicit in this definition that test scores are obtained on different occasions under the same conditions as administration and scoring; it also follows that reliability refers to the precision of the measurement, regardless of what the test measures, and that the reliability of the scores is relative since it is subject to the characteristics of the group of subjects in which it is estimated [18].

2. Objectives

The objectives of the present review are to: (1) to systematically identify three of the main measures of HWI in the literature, (2) to evaluate the psychometric properties presented in the reviewed studies, and (3) to determine whether there is a gold standard measure HWI.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design

The present review followed the official PRISMA guidelines [19] on data identification, collection, and analysis. In this sense, the article is a systematic review of instrumental studies on three of the most commonly used measures of HWI: Workaholism Battery (WorkBAT), Work Addiction Risk Test (WART), and Dutch Work Addiction Scale (DUWAS) [13].

3.2. Literature Search

First, five selection criteria were determined: (1) instrumental or psychometric studies [20], where the main objective of the article was the creation, adaptation, or psychometric analysis of an instrument measuring HWI or any of its components (Workaholism or Work addiction), specifically, the WorkBAT, WART, and DUWAS; (2) conducted in any country; (3) published up to 2020; (4) peer-reviewed articles; and (5) published in the Spanish or English language.

Three groups of keywords and phrases were used to search for potential articles. The first group is related to psychometric analysis (psychometric, validation, validity, reliability, adaptation, and dimensionality). The second group is related to HWI (heavy work investment, workaholism, work addiction, passion to work, job demands, work craving, work engagement, addiction to work, passion towards work passion for work, and heavy-work investment). The third group is related to self-report measures (questionnaire, measure, assessment, tool, instrument, scale, inventory, and battery). The final search was performed in all databases on 17 July 2021. All articles published up to 2020 were selected.

The search strategy generated a total of 2621 studies with 770 studies from Scopus, 1034 studies from Web of Science (Web of Science databases, including Science Citation Index Expanded [SCI-EXPANDED], Social Sciences Citation Index [SSCI], Arts & Humanities Citation Index [A&HCI], and Emerging Sources Citation Index [ESCI]), 654 studies from PsycNET (PsycInfo and PsycArticles), 110 studies from MEDLINE via Ovid, and 53 studies from Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection via EBSCO. Table 1 shows the search strategy followed in the five electronic databases.

Table 1.

Search strategy in the five electronic databases.

3.3. Selection Process

The search results were initially screened by title and abstract to exclude research that did not meet the selection criteria. Subsequently, the remaining studies were retrieved from the different databases and the full articles were evaluated according to their relevance to meet the stipulated selection criteria.

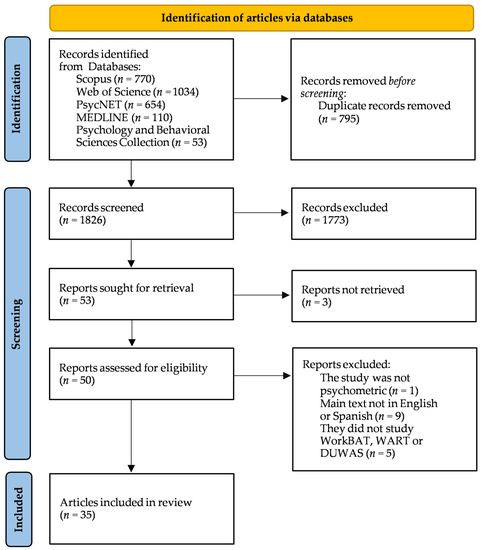

After excluding 795 duplicate searches and 1773 studies that did not meet the selection criteria (because they were qualitative studies, empirical studies, were in a language other than Spanish or English, or were psychometric but worked with other instruments), 53 articles were selected from the review of the title and abstract, and subsequently acquired the 50 articles that were reviewed in their entirety, obtaining a final sample of 35 articles containing 37 studies (one of the articles analyzed the three instruments of interest independently). The flow diagram of the selection of the preceding studies is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of selection of preceding articles.

3.4. Coding Process

The coding was carried out considering the following information from the items analyzed: (a) instrument name, authors, and year; (b) study design; (c) number of items in the instrument; (d) dimensions it measures; (e) number of response options; (f) sample size; (g) participant characteristics; (h) mean and standard deviation of participant age; (i) country of origin of the sample; (j) psychometric theory used for the analyses; (k) validity evidence collected; and (l) reliability evidence collected.

3.5. Literature Analysis

After selection and coding of the articles, 35 articles met all the requirements. However, one of the articles had three studies from each of the objective instruments (WorkBAT, WART and DUWAS). Therefore, 37 studies were compiled in the database for further analysis. The characteristics of each study were organized in Table S1 (Supplementary Materials). Based on the structured information, the results were elaborated to methodologically describe the three main measures of HWI.

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of the Studies

Of the 37 studies analyzed (Table 2), 13 belong to WorkBAT, 12 correspond to WART and 12 worked with DUWAS. The studies were published between 1992 and 2019. Regarding the study design of the articles reviewed, most of them (n = 22) focused on reviewing the psychometric properties (validity and reliability) of the WorkBAT, WART, and DUWAS. Likewise, a significant number of adaptations were reported (n = 12), where they sought to adjust the original tests to different cultural contexts. Finally, three studies were found where the tests that are the main focus of this review were developed or constructed [21,22,23].

Table 2.

Characteristics of the studies for each instrument.

Regarding the number of items, it was observed that the psychometric tests analyzed varied in number due to different factors: (1) they were short versions; (2) items were eliminated due to methodological problems; or (3) they only studied some factors of the instrument. Conversely, the dimensions measured by the tests also changed from one study to another, since the structures were not fully replicated in different samples. Nevertheless, the DUWAS was the one that most of the time showed a two-factor structure (nine studies). In terms of the number of response options, the DUWAS (from “almost never” to “almost always”) and the WART (from “never true” to “always true”) presented almost the same four-point Likert scale across studies. The WorkBAT was usually answered on a five-point Likert scale (from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”).

As for the sample size, in most cases it did not exceed 500 participants, which is necessary to obtain more robust and stable results, especially considering the diversity of structures presented by these tests. Furthermore, in some studies, the sample was larger than 1000 people. The participants in the studies presented diverse characteristics, mainly workers from different economic sectors (e.g., manufacturing, retail, service, education, or medical). Moreover, the age of the participants was generally between 30 and 50 years old. Finally, among the countries where these instruments have been most tested are the United States, Canada, Norway, the Netherlands, Italy, and Brazil, as well as others located in Asia and Oceania. No studies were found in Latin America or Africa.

4.2. Measurement Theory

The measurement theory that predominated in the studies was the Classical Test Theory (CTT) and only one study used the Rasch Measurement Theory (RMT) [54]. No study used the Item Response Theory (IRT). In this regard, it is important to note that some studies did not use a specific theory, because their objective was to collect evidence of validity and they did not focus on the analysis of items or the reliability of the scores [37,38,40]. CTT proposes a linear relationship between the observed score, the true score, and the measurement error, with the main limitation being the dependence of the persons and the test [55]. Conversely, the IRT seeks to explain the relationship between a person’s ability and the probability of answering an item correctly, considering various characteristics such as difficulty, discrimination, or pseudo-guessing [56]. The IRT is considered a descriptive model since it tries to explain as much of the variance as possible [57]. Finally, the RMT is a prescriptive model, in which it is of interest to know whether the data fit the measurement model and, like the IRT, it focuses on the individual analysis of the items based on the interaction between an item and a person [58].

4.3. Validity

Regarding the collection of validity evidence, the studies analyzed focused mainly on two aspects: the internal structure and the relationship with other variables. However, two studies collected evidence based on test content. This source of validity evidence refers to the degree to which the content (domain definition, domain representation, domain relevance, and appropriateness of construction processes) of a test is congruent with the measurement objectives [59].

4.3.1. Validity Evidence Based on Test Content

Two studies collected this source of evidence based on the presentation of the items and their classification by a group of students or experts in the field, a method different from the one usually used to collect this evidence of validity, which consists of a group of judges giving their assessment of the items according to certain features (representativeness, relevance or clarity). However, the method used in these studies has the characteristic of analyzing the representativeness of the items [37,38]. Both studies belonged to the WART.

4.3.2. Validity Evidence Based on Internal Structure

The three tests studied are multidimensional, so this source of evidence is one of the most widely used to corroborate how the instruments are structured according to their items. The techniques used for this purpose were mainly three: principal components analysis (PCA), exploratory factor analysis (EFA), and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). CFA was usually employed in studies reviewing psychometric properties as the first option, but, in cases where the fit was poor, a less restrictive method, such as PCA or EFA, was chosen. Of the three psychometric instruments, the DUWAS replicated its two-factor structure the most often. Thus, in nine studies, it was observed that the DUWAS was made up of the factors Working excessively and Working compulsively. Regarding the WorkBAT, a three-factor structure (Work involvement, Work enjoyment, and Drive) was observed in eight studies, although a two-factor structure (Work enjoyment and Drive) was also found in four studies. Finally, the WART showed a unidimensional structure in six studies, while four studies reported a five-factor structure (Compulsive tendencies, Control, Impaired communication, Self-worth, and Inability to delegate).

Within this validity, evidence is also the factorial invariance analysis that was employed by some studies to compare whether the structure of the instrument was invariant concerning the country of origin of the participants [23,53]. Factor invariance was performed through multi-group confirmatory factor analysis (MG-CFA), although in some cases the description of the procedure and results was not clear.

4.3.3. Validity Evidence Based on Relations to Other Variables

Since HWI is a relatively recent construct, it is necessary to form a nomological network to determine with which other variables it is related and with which it diverges. In this sense, this source of validity evidence made it possible to relate the total and factor scores of the WorkBAT, WART, and DUWAS to other variables such as Job stress, Job involvement, Time on the job, Overtime worked, Job satisfaction, and other variables linked to the organizational field. In most cases, simple correlation coefficients or simple linear regressions were used, with few studies analyzing the relationship between variables from a more advanced perspective such as structural equation models.

4.4. Reliability

The reliability of the scores was mostly evaluated by analyzing the internal consistency of the items and using the alpha coefficient. However, in no case were the assumptions that this reliability estimator needs to be used (unidimensional, absence of correlated errors, and tau-equivalence of the measurement model) corroborated. In addition, only one study reported confidence intervals for coefficient alpha. The DUWAS was the instrument that most often presented good levels of reliability (greater than 0.70). However, in some studies, it was found to be below this criterion. The WorkBAT and the WART had greater reliability problems in some of their dimensions, probably due to the number of factors (usually four) and the number of items that composed them.

In contrast, some studies evaluated reliability based on the temporal stability or test-retest method, which is necessary to determine whether test scores are constant over time. In most cases, the relationship between scores at time 1 and time 2 was low, less than 0.70 [28]. However, this could be influenced by the use of the simple correlation coefficient used to assess the agreement between the two measures. Only two studies used appropriate statistics for this purpose, such as the intraclass correlation coefficient [13] and Lin’s coefficient of concordance [44].

5. Discussion

The present review aimed to (1) systematically identify three of the main measures of HWI in the literature, (2) evaluate the psychometric properties presented in the reviewed studies, and (3) determine whether there is a gold standard measure of HWI. Regarding the first objective, three measurement instruments were analyzed, the Workaholism Battery (WorkBAT), Work Addiction Risk Test (WART), and Dutch Work Addiction Scale (DUWAS), which are the main measures with which various studies approach the phenomenon of HWI. Regarding the second objective, the empirical evidence of the instruments was systematized concerning the validity and reliability of their scores. Finally, regarding the third objective, although the DUWAS is the test that shows the best performance, because its two-factor factor structure was replicated and presented better levels of reliability in most studies, it is slightly superior to the WorkBAT and the WART, so it cannot be concluded that it is the most optimal measure for the measurement of HWI. Thus, further studies with these instruments, based on more robust methodologies, are needed.

About the measurement theory used, the tests have not been tested through the Item Response Theory (IRT) or different models of the Rasch Measurement Theory (RMT), so the performance of the items and the test in people with different levels of HWI is not known. That is, through these models, it is possible to identify at what level of trait of the person, the instruments are more or less reliable since from the CTT reliability is only estimated globally. Moreover, from these two perspectives, it is possible to construct computerized adaptive tests, where workers do not always have to answer the same items and the same number of items, but where the items are adapted to their responses and their trait levels.

Regarding validity, it is necessary to provide evidence of the content of the items. The two studies that were found, and that collected this evidence are more than 20 years old, so the context in which they were evaluated is different from the current one. Likewise, two additional sources of validity have not been studied to date. The evidence of validity is based on response processes, which would allow us to know to what emotions, feelings, thoughts, memories, and behaviors of those evaluated associate when they read the items of the instruments. In this way, we could approximate an explanation that the items are indeed assessing aspects of HWI. In addition, the last source of evidence that has not been considered is that based on the consequences of the application of the test and that involves aspects that go beyond the assessment, such as the actions that could be taken after learning the results in a particular group.

Regarding the reliability of the measures, the results were very variable, finding in many cases values below the minimum acceptable (0.70). However, it is important to note that in no case were the alpha coefficient assumptions corroborated, so there is a possibility that they are underestimated or distorted. Likewise, as in other statistical techniques, it is necessary to consider the nature of the items being worked on, since the WorkBAT, WART, and DUWAS have a Likert-type scale, whose level of measurement is ordinal. Therefore, reliability estimators should be calculated based on a polychoric matrix, which allows a coherent evaluation of the internal consistency of the scores. Conversely, temporal stability has been used in several studies, although methodologically, the best coefficient was not used to see if the scores changed substantially from one assessment to another. In almost all cases, a correlation coefficient was used, which is responsible for seeing whether the scores would be found to be related. However, in these cases, it is suggested to use a coefficient that assesses the concordance (coincidence) of the scores.

Currently, there are systematic reviews of measures of different variables relevant to the organizational field, for example, stakeholder engagement [60] or human resource management systems [61]. However, as mentioned at the beginning of the review, this is the first work that systematically evaluates the psychometric properties of HWI measures. Nevertheless, the study by Andreassen et al. (2013) [13] empirically studied the psychometric properties of the WorkBAT, WART, and DUWAS, through a cross-sectional study where they analyzed the temporal stability and factorial structure of the aforementioned instruments. The study was conducted with 368 Norwegian workers and found that the correlations between the scales were low, showing low convergent evidence, weak temporal stability of scores, and an internal structure for the WorkBAT of four factors, as well as for the WART, while the DUWAS showed a two-factor factorial solution. The authors concluded that the three measures could be used interchangeably. This coincides with the findings of the present review since no outstanding performance of any of the measures was observed over the others.

The present review has some limitations. First, this review only synthesized those articles written in English or Spanish, and articles written in other languages were not involved. Further, three instruments measuring one side of HWI were analyzed, which, although they are not the main ones, are not the only ones, since other tests could also be observed in the selection of the final articles, although in a smaller proportion (for example, the Workaholism Analysis Questionnaire—WAQ or Bergen Work Addiction Scale—BWAS). Moreover, only articles published up to 2020 were analyzed. However, in 2021, one psychometric study has been published that present tools specific to the HWI considering Time Commitment and Work Intensity as dimensions [62]. Thus, the aforementioned limitations should be taken into consideration for future studies, where other instruments are analyzed, that can help to understand this construct that is in full development and boom in terms of research to have a clearer approximation of its functioning.

This systematic review has theoretical and practical implications related to HWI. At a theoretical level, the review of the three instruments allows us to know the different aspects of HWI, specifically workaholism and work addiction, exploring how they are theoretically related to other variables, such as job satisfaction and engagement. In this way, it allows the construction of a nomological network for HWI, where different organizational and mental health constructs are explored. However, the practical implications lie in knowing the strengths and weaknesses of the three measures analyzed to know which versions have the most empirical support and which are still to be studied.

Likewise, the article contributes to the HWI research line, especially in the current context of a health emergency, where teleworking conditions have made the line between personal and professional life increasingly thinner, or in some cases, disappearing. Therefore, it is necessary to have good measurement tools that can capture relevant details of HWI in workers who have high levels of time and effort investment. In this sense, the findings obtained suggest that the DUWAS, the WorkBAT, and the WART can be used to measure HWI. However, the DUWAS presents a slightly better psychometric performance than the other two scales, so it should be considered as a first option although the decision should be linked to other factors such as the objective of the measurement, the components to be explored, and the context of the application.

These findings suggest that HWI has consequences in the organizational field and applied settings (e.g., occupational health or human resources). Moreover, integral to theory development is the ability to differentiate a construct from its antecedents and outcomes. Therefore, developing a thorough understanding of the nature of the HWI phenomenon and its consequences requires the use of sound and appropriate psychometric tools to measure the construct.

6. Conclusions

The present systematic review constitutes the first effort to summarize the psychometric properties of three popular HWI measures (WorkBAT, WART, and DUWAS). In this way, the review provides empirical evidence of the performance of the three instruments so that researchers, psychologists, managers, and other interested parties can choose the measure that best suits their needs and objectives of use. According to the findings obtained, the three HWI measurement instruments have similar performance, so it is advisable to conduct additional psychometric studies focused on other sources of validity evidence, analysis of bias due to certain sociodemographic variables, or with more robust psychometric models (for example, from the IRT or RMT). Finally, based on this review, it is possible to propose new lines of research focused on covering under-explored or unexplored psychometric aspects of the WorkBAT, WART, and DUWAS.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su132212539/s1, Table S1: Characteristics of the studies for each instrument.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C.A.-P., A.A.T.-M., R.A.Z.-T. and D.E.R.-O.; methodology, J.C.A.-P., A.A.T.-M., R.A.Z.-T. and D.E.R.-O.; software, J.C.A.-P., A.A.T.-M., R.A.Z.-T. and D.E.R.-O.; validation, J.C.A.-P., A.A.T.-M., R.A.Z.-T. and D.E.R.-O.; formal analysis, J.C.A.-P., A.A.T.-M., R.A.Z.-T. and D.E.R.-O.; investigation, J.C.A.-P., A.A.T.-M., R.A.Z.-T. and D.E.R.-O.; resources, J.C.A.-P., A.A.T.-M., R.A.Z.-T. and D.E.R.-O.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C.A.-P., A.A.T.-M., R.A.Z.-T. and D.E.R.-O.; writing—review and editing, J.C.A.-P., A.A.T.-M., R.A.Z.-T. and D.E.R.-O.; visualization, J.C.A.-P., A.A.T.-M., R.A.Z.-T. and D.E.R.-O.; supervision, J.C.A.-P., A.A.T.-M., R.A.Z.-T. and D.E.R.-O.; project administration, J.C.A.-P., A.A.T.-M., R.A.Z.-T. and D.E.R.-O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Snir, R.; Harpaz, I. Beyond workaholism: Towards a general model of heavy work investment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2012, 22, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, G.; Gaudiino, M. Workaholism and work engagement: How are they similar? How are they different? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2019, 28, 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabak, F.; Tziner, A.; Shkoler, O.; Rabenu, E. The complexity of Heavy Work Investment (HWI): A conceptual integration and review of antecedents, dimensions, and outcomes. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziner, A.; Buzea, C.; Rabenu, E.; Shkoler, O.; Truţa, C. Understanding the relationship between antecedents of Heavy Work Investment (HWI) and burnout. Amfiteatru Econ. 2019, 21, 153–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M.D.; Demetrovics, Z.; Atroszko, P.A. Ten myths about work addiction. J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 845–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Shimazu, A.; Demerouti, E.; Shimada, K.; Kawakami, N. Work engagement versus workaholism: A test of the spillover-crossover model. J. Manag. Psychol. 2014, 29, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth-Király, I.; Morin, A.J.S.; Salmela-Aro, K. A longitudinal perspective on the associations between work engagement and workaholism. Work Stress 2021, 35, 27–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Prado, J.C.; Sandoval-Reyes, J.G.; Sanchís-Pedregosa, C. Job demands and recovery experience: The mediation role of heavy work investment. Amfiteatru Econ. 2020, 22, 1206–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzetti, G.; Guglielmi, D.; Schaufeli, W.B. Same involvement, different reasons: How personality factors and organizations contribute to heavy work investment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beek, I.; Taris, T.W.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Brenninkmeijer, V. Heavy work investment: Its motivational make-up and outcomes. J. Manag. Psychol. 2014, 29, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudiino, M.; Di Stefano, G. To detach or not to detach? The role of psychological detachment on the relationship between heavy work investment and well-being: A latent profile analysis. Curr. Psychol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balducci, C.; Alessandri, G.; Zaniboni, S.; Avanzi, L.; Borgogni, L.; Fraccaroli, F. The impact of workaholism on day-level workload and emotional exhaustion, and on longer-term job performance. Work Stress 2021, 35, 6–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Hetland, J.; Pallesen, S. Psychometric assessment of workaholism measures. J. Manag. Psychol. 2013, 29, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, I.; Olea, J.; Abad, F.J. Exploratory factor analysis in validation studies: Uses and recommendations. Psicothema 2014, 26, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Educational Research Association; American Psychological Association; National Council on Measurement in Education. Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing; American Educational Research Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-0935-302-356. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.; Bernstein, I. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994; ISBN 9780070478497. [Google Scholar]

- Raykov, T. Estimation of composite reliability for congeneric measures. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1997, 21, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flora, D.B. Your coefficient alpha is probably wrong, but which coefficient omega is right? A tutorial on using R to obtain better reliability estimates. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 3, 484–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ato, M.; López, J.J.; Benavente, A. A classification system for research designs in psychology. An. Psicol. 2013, 29, 1038–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, J.T.; Robbins, A.S. Workaholism: Definition, measurement, and preliminary results. J. Pers. Assess. 1992, 58, 160–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B.E. The Work Addiction Risk Test: Development of a tentative measure of workaholism. Percept. Mot. Skills 1999, 88, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Shimazu, A.; Taris, T.W. Being driven to work excessively hard: The evaluation of a two-factor measure of workaholism in the Netherlands and Japan. Cross-Cult. Res. 2009, 43, 320–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanai, A.; Wakabayashi, M.; Fling, S. Workaholism among employees in Japanese corporations: An examination based on the Japanese version of the Workaholism Scales. Jpn. Psychol. Res. 1996, 38, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, R.J. Workaholism in organizations: Measurement validation and replication. Int. J. Stress Manag. 1999, 6, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, R.J. Spence and Robbins’ measures of workaholism components: Test-retest stability. Psychol. Rep. 2001, 88, 882–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, R.J.; Koksal, H. Workaholism among a sample of Turkish managers and professionals: An exploratory study. Psychol. Rep. 2002, 91, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, R.J.; Richardsen, A.M.; Martinussen, M. Psychometric properties of Spence and Robbins’ measures of workaholism components. Psychol. Rep. 2002, 91, 1098–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMillan, L.H.W.; Brady, E.C.; O’Driscoll, M.P.; Marsh, N.V. A multifaceted validation study of Spence and Robbins’ (1992) Workaholism Battery. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2002, 75, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersoy-Kart, M. Reliability and validity of the Workaholism Battery (Work-BAT): Turkish Form. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2005, 33, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Ursin, H.; Eriksen, H.R. The relationship between strong motivation to work, “workaholism”, and health. Psychol. Health 2007, 22, 615–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.C.; Hu, C.; Wu, T.C. Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the workaholism battery. J. Psychol. 2010, 144, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boada-Grau, J.; Prizmic-Kuzmica, A.-J.; Serrano-Fernández, M.-J.; Vigil-Colet, A. Estructura factorial, fiabilidad y validez de la escala de adicción al trabajo (WorkBAT): Versión española. An. Psicol. 2013, 29, 923–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Santos, J.; Sousa, C.; Sousa, A.; Figueiredo, L.; Gonçalves, G. Psychometric evidences of the Workaholism Battery in a Portuguese sample. J. Spat. Organ. Dyn. 2018, 6, 40–51. [Google Scholar]

- Urbán, R.; Kun, B.; Mózes, T.; Soltész, P.; Paksi, B.; Farkas, J.; Kökönyei, G.; Orosz, G.; Maráz, A.; Felvinczi, K.; et al. A four-factor model of work addiction: The development of the Work Addiction Risk Test Revised. Eur. Addict. Res. 2019, 25, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, B.E.; Post, P.; Khakee, J.F. Test-retest reliability of the Work Addiction Risk Test. Percept. Mot. Skills 1992, 74, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B.E.; Post, P. Validity of the Work Addiction Risk Test. Percept. Mot. Skills 1994, 78, 337–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, B.E.; Phillips, B. Measuring workaholism: Content validity of the Work Addiction Risk Test. Psychol. Rep. 1995, 77, 657–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, B.E.; Post, P. Split-half reliability of the Work Addiction Risk Test: Development of a measure of workaholism. Psychol. Rep. 1995, 76, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, B.E. Concurrent validity of the Work Addiction Risk Test as a measure of workaholism. Psychol. Rep. 1996, 79, 1313–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flowers, C.P.; Robinson, B. A structural and discriminant analysis of the Work Addiction Risk Test. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2002, 62, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taris, T.W.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Verhoeven, L.C. Workaholism in the Netherlands: Measurement and implications for job strain and work-nonwork conflict. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 54, 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, M.; Yepes-Baldó, M.; Berger, R.; da Costa, F.F.N. Workaholism in Brazil: Measurement and individual differences. Adicciones 2014, 26, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravoux, H.; Pereira, B.; Brousse, G.; Dewavrin, S.; Cornet, T.; Mermillod, M.; Mondillon, L.; Vallet, G.; Moustafa, F.; Dutheil, F. Work Addiction Test questionnaire to assess workaholism: Validation of French version. JMIR Ment. Health 2018, 5, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Líbano, M.; Llorens, S.; Salanova, M.; Schaufeli, W. Validity of a brief workaholism scale. Psicothema 2010, 22, 143–150. [Google Scholar]

- Falco, A.; Kravina, L.; Girardi, D.; Dal Corso, L.; Di Sipio, A.; De Carlo, N.A. The convergence between self and observer ratings of workaholism: A comparison between couples. Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 19, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molino, M.; Ghislieri, C.; Colombo, L. Working excessively: Theoretical and methodological considerations. G. Ital. Med. Lav. Ergon. 2012, 34, A5–A10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Sharma, J. A confirmatory factor analysis of Dutch Work Addiction Scale (DUWAS). Glob. Bus. Rev. 2013, 14, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littman-Ovadia, H.; Balducci, C.; Ben-Moshe, T. Psychometric properties of the Hebrew version of the Dutch Work Addiction Scale (DUWAS-10). J. Psychol. 2014, 148, 327–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rantanen, J.; Feldt, T.; Hakanen, J.J.; Kokko, K.; Huhtala, M.; Pulkkinen, L.; Schaufeli, W. Cross-national and longitudinal investigation of a short measure of workaholism. Ind. Health 2015, 53, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, I.; Kamal, A.; Masood, S. Translation and validation of Dutch Workaholism Scale. Pakistan J. Psychol. Res. 2016, 31, 331–346. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, W.F.; Mathias, L.A. da S.T. Addiction to work and factors relating to this: A cross-sectional study on doctors in the state of Paraíba. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2017, 135, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balducci, C.; Avanzi, L.; Consiglio, C.; Fraccaroli, F.; Schaufeli, W. A cross-national study on the psychometric quality of the Italian version of the Dutch Work Addiction Scale (DUWAS). Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2017, 33, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonnis, M.; Cuccu, S.; Cortese, C.G.; Massidda, D. The Italian version of the Dutch Workaholism Scale (DUWAS): A study on a group of nurses. BPA Appl. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 65, 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Traub, R.E. Classical Test Theory in historical perspective. Educ. Meas. Issues Pract. 1997, 16, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMars, C. Item Response Theory; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sharkness, J. Item Response Theory: Overview, applications, and promise for institutional research. New Dir. Institut. Res. 2014, 2014, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, T.G.; Yan, Z.; Heene, M. Applying the Rasch Model: Fundamental Measurement in the Human Sciences, 4th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sireci, S.; Faulkner-Bond, M. Validity evidence based on test content. Psicothema 2014, 26, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowen, D.J.; Hyams, T.; Goodman, M.; West, K.M.; Harris-Wai, J.; Yu, J.-H. Systematic review of quantitative measures of stakeholder engagement. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2017, 10, 314–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boon, C.; Den, D.N.; Lepak, D.P. A systematic review of human resource management systems and their measurement. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 2498–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkoler, O.; Rabenu, E.; Iqbal, M.Z.; Ferrari, F.; Hatipoglu, B.; Roazzi, A.; Kimura, T.; Tabak, F.; Moasa, H.; Vasiliu, C.; et al. Heavy-Work Investment: Its dimensionality, invariance across 9 countries and levels before and during the COVID-19’s pandemic. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2021, 37, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).