Abstract

Effective disaster warning systems prevent deaths and injuries and protect livelihoods. We examined why people at risk do not move to safe places despite warnings and evacuation orders, by looking at responses to warnings for Cyclone Mora (2017) in Bangladesh in two villages of the Khulna District. Qualitative and quantitative data showed that almost all respondents received warnings before the cyclone, most from more than one source. However, only 21.6% of households took shelter in any place other than their own house. Most of these households did so with all members of their household, and most used a cyclone shelter. Almost all non-evacuee households had more than one reason for not moving to another place. The most important reasons were that they thought the weather was good despite warnings, thought the cyclone would not occur in their area, had a fatalistic attitude, were a long distance from the nearest cyclone shelter, had poor road networks to go to the cyclone shelter, considered their own house to be a safe place, were scared of burglary, recalled that nothing happened during previous warnings, and were worried about overcrowded cyclone shelters. Our findings can help develop more effective warning systems in cyclone-prone regions globally.

1. Introduction

Early warning systems have played a vital role in reducing deaths, injuries, and loss of livelihoods from disasters in recent decades [1]. In the era of climate change, the role of early warning systems as an adaptive measure has become even more critical to prepare people for climate-related events and support climate-resilient development [2]. The Sendai Framework [3] and its predecessor the Hyogo Framework [4] have emphasised the significance of early warning systems as a vital component of disaster risk reduction. The Sendai Framework [3] has set a global target to “substantially increase the availability of and access to multi-hazard early warning systems and disaster risk information and assessments to people by 2030”. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [5] and the Paris Agreement [6] have also focused on the importance of strengthening early warning systems. Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3 and SDG 13 have set targets for strengthening early warning systems [5]. Similarly, Articles 7 and 8 of the Paris Agreement have also emphasised the necessity of strengthening early warning systems [6].

The effectiveness of an early warning system is largely dependent on the response of the people at risk to the warnings disseminated and communicated to them [1,7]. Thus, early warning systems need to be people-centred, as emphasised in major international documents such as the Hyogo Framework, the Sendai Framework, and the World Disasters Report 2009 [1,3,4]. Social and psychological aspects of the people or society in which the early warning system is placed must be considered as essential elements [1,7].

In Bangladesh, the Cyclone Preparedness Programme (CPP), established by the League of Red Cross in 1972 and now a joint programme of the Bangladesh Government and Bangladesh Red Crescent Society, has played a significant role in reducing the number of deaths from cyclones [1,8]. Although Bangladesh has significantly improved its dissemination of cyclone early warnings and evacuation, most potential victims do not participate in evacuation initiatives [7,9,10,11].

Cyclone Mora made landfall in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, on 30 May 2017 [12]. It affected 3.3 million people in four districts [13], causing seven deaths in three of those districts [13,14] and damaging more than 100,000 houses in two of them [12]. It also badly affected the makeshift settlements of Rohingya refugees living in Cox’s Bazar [12].

This paper examines evacuation behaviour during Cyclone Mora and reasons why non-evacuee households did not take refuge in any place other than their own house despite evacuation orders.

2. Study Areas and Methodology

This paper defines evacuation as taking refuge in a place (including cyclone shelters) other than one’s own house after receiving orders to take refuge in safe places. This definition excludes people who stay in their own houses, even though their own houses can sometimes be a safe place.

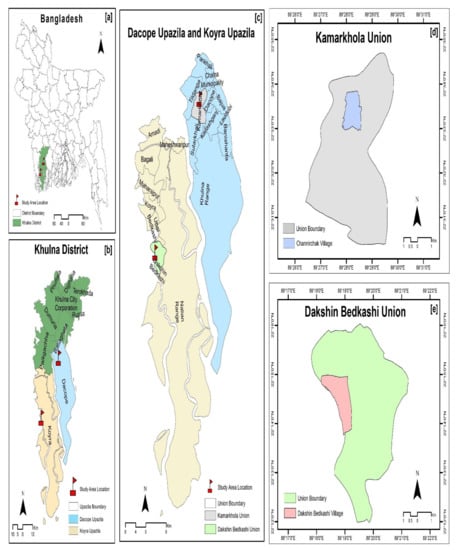

This paper is based on primary data collected from two villages in Bangladesh: Channirchak Village (Kamarkhola Union, Dacope Upazila) and Dakshin Bedkashi Village (Dakshin Bedkashi Union, Koyra Upazila). Both villages are in the Khulna District (see Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3), which is highly vulnerable to cyclones [15], and were the villages worst affected by Cyclone Aila. An upazila (sub-district) comprises several unions, and a union comprises nine wards [16]. Channirchak Village is a part of Ward Number 3 of Kamarkhola Union, and Dakshin Bedkashi Village represents Ward Number 7 of Dakshin Bedkashi Union, as it is the only village in the ward.

Figure 1.

(a) Location of Khulna District in Bangladesh, (b) Khulna District, (c) Dacope Upazila and Koyra Upazila, (d) Location of Channirchak Village within Kamarkhola Union, (e) Location of Dakshin Bedkashi Village within Dakshin Bedkashi Union. Source: First author (2017–2018).

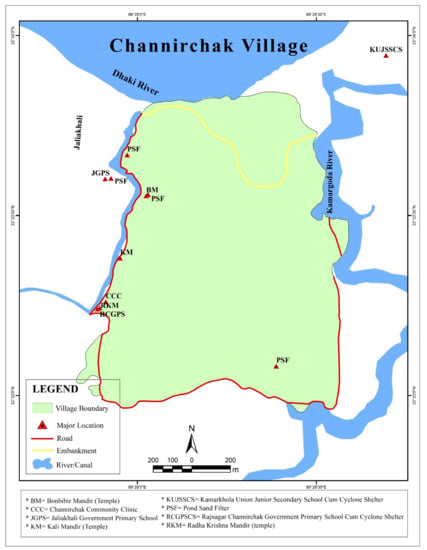

Figure 2.

Map of Channirchak Village. Source: First author (2017–2018).

Figure 3.

Map of Dakshin Bedkashi Village. Source: First author (2017–2018).

This study used an exploratory sequential mixed methods design. Qualitative data were collected in the first phase and quantitative data in the second phase. Qualitative data were collected using a constructivist paradigm, and quantitative data were collected using a post-positivist paradigm. Both qualitative and quantitative strands were mixed during data collection, analysis, and interpretation [17]. Quantitative household-level survey data were collected in the second phase through a survey questionnaire developed based on the preliminary analysis of the qualitative data [17,18]. Data were collected by the first author as part of his research for the Doctor of Philosophy award at the Australian National University (ANU), Australia, in accordance with ANU human research ethics approval (Protocol number 2017/115). He carried out nine months of fieldwork in the two study villages in two phases: May 2017 to January 2018 and March 2019 to April 2019.

Qualitative data were collected through three qualitative data collection methods: in-depth interview, focus group discussion (FGD), and observation. Quantitative data were collected through a household survey. The data were gathered through 83 in-depth semi-structured interviews (32 in Channirchak and 51 in Dakshin Bedkashi), and interviews were with household heads, including female-headed households and the wives of male household heads in the absence of the male household heads. In addition to the 83 interviews, 8 FGDs in two villages, 4 with males and 4 with females, were also conducted. Two FGDs in Channirchak and two FGDs in Dakshin Bedkashi were conducted with male household heads or any adult male members in the absence of male household heads. Similarly, two FGDs in Channirchak and two FGDs in Dakshin Bedkashi were conducted with wives of male-headed households and heads of female-headed households. In addition, 49 key informant interviews (23 for Channirchak and 26 for Dakshin Bedkashi) were conducted. Key informants were elected representatives and the secretary of the local government (UP); government officials, including officials of the Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB), which is a statutory body [19]; employees of national and international NGOs; and political leaders, community leaders, and local school teachers from the two study villages and surrounding areas. Two key informant interviews with two NGO officials were conducted in October 2019 by phone.

Quantitative data were collected through a household survey of 250 households in the two study villages (70 from Channirchak Village and 180 from Dakshin Bedkashi Village). ‘Household’ was the unit of analysis for the survey. The survey respondents were household heads (either male- or female-headed households) or wives of the household heads in the absence of the household heads during the survey. In addition to primary data, various documents and maps were collected from local government authorities, government agencies, BWDB, and many national and international NGOs.

Qualitative data were analysed using thematic analysis [20]. Qualitative interviews were transcribed and then sorted and arranged. Themes were then identified through a bottom-up approach, i.e., through a data-driven approach [20]. Then, each theme, including the similarities and dissimilarities among the research participants regarding a theme, and the interconnectedness among the themes were carefully reviewed. Finally, the findings presented based on the themes were compared with the findings of the relevant existing studies or theories. Survey data were inputted and analysed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). Although qualitative and survey data were analysed individually first, they were mixed during data analysis and interpretation by linking the findings of one database to the findings of another database in a manner that compares and synthesises the findings of both databases [17] and shows the extent to which the qualitative findings can be generalised to a larger sample [17,18].

3. Reception and Sources of Cyclone Warnings during Cyclone Mora

The Storm Warning Centre (SWC) of the Bangladesh Meteorological Department (BMD) provides forecasting and issues cyclone warnings in Bangladesh [21]. The SWC initiates the cyclone alert stage and cyclone warning stage at least 36 h and at least 24 h before the predicted rainfall, respectively. The cyclone disaster stage and cyclone great danger stage are initiated at least 18 h and at least 10 h before the predicted landfall, respectively. The cyclone danger warning is issued when wind speeds exceed 61 km/h, while the cyclone great danger warning is issued when wind speeds exceed 89 km/h [21]. The SWC uses signals from 1 to 11 for maritime ports and 1 to 4 for inland river ports; danger is 5–7, while great danger is 8–10 [22]. The SWC directly sends warning messages to the National Coordination Committee, the CPP, and other user agencies such as local administration and the media. In addition, the CPP also disseminates warning messages to coastal villagers via CPP units at various levels [7]. When communication with the SWC breaks down, Signal 11 is used, which indicates that local officers consider that a devastating cyclone is imminent [22].

During Cyclone Mora, the SWC danger signal for the Khulna District that covers the two study villages was 8 [23,24]. Warning messages during Mora were disseminated to the two study villages through a signal number as well as through the hoisting of cyclone warning flags. It is worth nothing that one flag is hoisted when the signal is 4, two flags are hoisted when the signal is 5 to 7, and three flags are hoisted when the signal is 8 to 10 [8,25]. The information in a cyclone warning message usually includes the position of the cyclone, direction and rate of movement of the cyclone, expected maximum wind speed, forecasted storm surge height, areas likely to be affected, and recommended safety measures for fishing boats [21]. The survey data show that 99.6% of respondents received cyclone warnings before Mora reached landfall. The only respondent who did not receive cyclone warnings was in Dakshin Bedkashi Village. Almost all (99.2%) respondents that received warnings (n = 249) received them from more than one source. The four most important sources were relatives, neighbours, friends, and acquaintances; CPP volunteers; mosques/temples; and radio (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Sources of cyclone warnings during Mora (multiple responses possible).

This finding is consistent with some earlier studies in Bangladesh, which found that 99% [26] and 95% [27] of respondents received warnings prior to Cyclone Gorky (1991) reaching landfall. However, a study on Cyclone Sidr (2007) [28] and one on Cyclone Aila (2009) [29] found that only 17% and 12.5% of total respondents did not receive warnings, respectively. Roy et al. [21], who conducted a study in four unions of Bagerhat and Patuakhali districts, found that 98% of the respondents of two unions of Patuakhali received warnings prior to the landfall of both Cyclone Sidr (2007) and Cyclone Viyaru (2013) (also known as Cyclone Mahasen [30]). However, although 93% of the respondents in the two unions of Bagerhat received warnings prior to the landfall of Cyclone Sidr (2007), only 83% of them received warnings prior to the landfall of Cyclone Viyaru (2013) [21].

There was a significant difference between the two villages in the current study in terms of warnings from mosques/temples, television, and NGOs. Channirchak has three temples and Dakshin Bedkashi has two mosques and two temples. Both mosques in Dakshin Bedkashi have microphones, whereas none of the temples in either village have microphones. As the warnings were disseminated many times from the mosques in Dakshin Bedkashi, the percentage of people mentioning mosques/temples as one of the sources is significantly high. Moreover, as Muslims usually go to mosque every day, they might have received the warnings directly from the imam (who leads prayers) and others who attended prayers in the mosque. Temples usually disseminated warnings by telling people who visited the temples.

Neither Channirchak nor Dakshin Bedkashi have electricity; the few households in each village with a television use solar power or a battery to watch it. More respondents may have received warnings from television in Channirchak because the local bazaar (in a different union), where villagers usually do their daily shopping, has electricity and also some televisions, particularly in tea stalls.

More respondents in Channirchak than Dakshin Bedkashi received warnings from NGOs/NGO volunteers. This might be due to the active presence of NGOs working on disaster risk reduction in Channirchak during the time of Mora. NGO officials and community volunteers involved in the projects being implemented by NGOs played an active role in disseminating warning messages. However, there were no NGOs working directly on disaster risk reduction in Dakshin Bedkashi during that period. There was also a difference between the two villages in terms of both unelected village leaders and local government as a source of warnings, with more warnings being received from them in Channirchak.

4. Evacuation Behaviour during Mora

As per the Standing Orders on Disaster 2019 in Bangladesh, people in areas with signal 8 should be evacuated to cyclone shelters or buildings, and evacuation of all people should be ensured when an area is under signal 9 or 10 [25].

Survey respondents were asked whether either the respondent or any member of the respondent’s household took refuge somewhere other than the respondent’s own house (see Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8). About 21.6% (n = 54) of the total surveyed households (n = 250) took refuge somewhere other than the respondent’s own house. Of these 54 households, 72.2% (n = 39) undertook complete evacuation (evacuation of all members of the household), while 27.8% (n = 15) undertook partial evacuation (evacuation of only one member or some members of the household). Among households that undertook partial evacuation (n = 15), more than one member moved to other places from all the households except one (see Table 2 for details). The survey asked who took refuge if a household undertook partial evacuation in the form of four categories: women, children, older people, and men. It is worth noting that ‘women took refuge in other places’ does not necessarily mean that all female members of a particular household evacuated. This logic also applies to the other three categories.

Figure 4.

Rajnagar Channirchak Government Primary School-cum-Cyclone Shelter, Channirchak. Source: Fieldwork (2017–2018).

Figure 5.

Kamarkhola Union Junior Secondary School-cum-Cyclone Shelter in the adjacent village of Channirchak. Source: Fieldwork (2017–2018).

Figure 6.

Cyclone Shelter and Multipurpose Community Centre in Dakshin Bedkashi (built by Caritas, The Netherlands in 1992 and repaired by Islamic Relief Bangladesh in 2014). Source: Fieldwork (2017–2018).

Figure 7.

Union Parishad building used as a safe place to take refuge, Dakshin Bedkashi. Source: Fieldwork (2017–2018).

Figure 8.

Dakshin Bedkashi Secondary School in Dakshin Bedkashi used as a safe place to take refuge (only the second floor can be used). Source: Fieldwork (2017–2018).

Table 2.

Breakdown of people who evacuated in households with partial evacuation.

Village survey data reveal that 18.6% (n = 13) of the surveyed households (n = 70) in Channirchak undertook either complete or partial evacuation, while that figure was 22.8% (41 out of 180) in Dakshin Bedkashi. In Channirchak (n = 13), in 53.8% of households (n = 7), all members of the household moved to a safer place, while a member or some members moved to a safer place in 46.2% of households (n = 6). On the other hand, among evacuee households in Dakshin Bedkashi (n = 41), all members of the household moved to another place in 78% of households (n = 32), while a member or some members moved to another place in 22% of households (n = 9).

These findings are both consistent and inconsistent with the findings of previous studies. Haque’s [27] study on Cyclone Gorky found that 22.76% (n = 61) of the respondents (n = 268) moved either all household members or women and children only, and 12.69% (n = 34) and 10.7% (n = 27) evacuated all household members and women and children only, respectively. Paul et al.’s [11] study on Cyclone Gorky found that 26.7% of the respondents evacuated. Likewise, Paul’s [10] study on Cyclone Sidr reports that evacuation to safe places took place in slightly over 33% of the respondents’ households, while Paul’s [31] study on Cyclone Sidr reports that 41.4% of respondents evacuated to a safe place (cyclone shelters and other’s house). Ahsan et al.’s [9] study shows that 33% of the respondents took safe refuge during Cyclone Aila. Paul et al. [11], Paul [31], and Ahsan et al. [9] inquired as to whether the respondent evacuated, while Paul [10] asked whether any member of the household evacuated.

Previous studies show that evacuation proportions can be different between areas. For example, 39.1% of the population of the three most vulnerable unions of Kutubdia (Uttar Dhurung, Ali Akbar Deil, and Kaiyarbil) moved to public cyclone shelters or places designated as shelters by the authorities, while only 16.8% of the three most vulnerable unions of Maheshkhali (Dhalghata, Matarbari, and Kutubjom) did so during Cyclone Viyaru. Likewise, for the same three unions in each upazila, 36.4% in Kutubdia and 16.3% in Maheshkhali moved to public cyclone shelters or places designated as shelters by the authorities during Cyclone Komen [7]. The data for Cyclone Viyaru and Cyclone Komen in Kutubdia and Maheshkhali did not count people who evacuated to places other than public cyclone shelters or places designated as shelters by the authorities.

Among evacuee households (n = 54), 72.2% (n = 39) took refuge in a cyclone shelter; see Table 3 for a list of other locations. In households where all members moved to another place or more than one member moved to another place, everyone moved to same place.

Table 3.

Non-home places of refuge used during Cyclone Mora.

5. Reasons for Not Taking Refuge

More than three-quarters (78.4%) of the total surveyed households did not take refuge in any place other than their own house. The top five reasons for this were: weather was good despite warnings; cyclone would not occur here; the cyclone is Allah’s/God’s will, so He will save us; distance to the nearest cyclone shelter is too far; and road network to go to the cyclone shelter is poor (see Table 4). Almost all (98%) of the non-evacuee households (n = 196) cited more than one reason for not moving to any place other than own house.

Table 4.

Reasons for not taking refuge in any place (multiple responses possible).

‘Weather was good despite warnings’ was one of the major reasons for not following evacuation orders during Mora, with 89.3% of the non-evacuee households (n = 196) mentioning this. Although most households take some precautionary measures, such as packing of household goods, money, ornaments, and necessary documents after they receive warnings, only some households take shelter in safe places with all members. Some households send only their vulnerable members, such as pregnant women, children, the aged, and people with a disability, to a safe place. However, most households do not move to the safe place until the weather becomes extremely bad. Other studies also found that most people wait up until the last minute and leave home when water reaches their courtyard [10,21,32,33,34]. This can also be understood from the following statements of interviewees:

If weather is calm, wind is not strong, there is no rain or it rains sometimes and sometimes does not, then people do not go [to the cyclone shelter] despite signals. When there is heavy rainfall and severe wind and the condition of the sky is bad, then some people go to the shelter. It depends on the weather.(A CPP volunteer, Channirchak, 8 June 2017).

We always remain alert … We stay prepared but do not go [to the embankment] … We stayed awake all night during Mora.(Channirchak, 23 August 2017).

If there is signal, we pack dry food, clothes, documents of land, and money and then wait. When we see that the weather is too bad, we go to the cyclone shelter, otherwise, we do not go.(Channirchak, 9 June 2017).

We stay prepared. We would go if it comes … When we see the weather is getting worse and other people are going [to the cyclone shelter or other safe places] … wind is violent, the rain is torrential, we then prepare to go to the cyclone shelter. We go at the last minute … If there is no violent storm or heavy rainfall, we do not want to go there.(Dakshin Bedkashi, 18 June 2017).

We stay prepared after packing dry food, clothes, matches, torch, medicines, money and documents of land. We will go if the weather worsens. We observe either the weather is worsening or improving when we stay at home. If the weather gets extremely bad, we would go to the cyclone shelter. We stay prepared. If there is any difficulty, we would go.(Dakshin Bedkashi, 18 June 2017).

‘Thought that cyclone would not occur here’ was also a common reason for not taking refuge, with about 68.9% (n = 135) of respondents of non-evacuee households (n = 196) mentioning this. Haque and Blair [26] and Haque [27] also found that this reason discourages responses to warnings. This is not linked to distrust of warnings; rather, it is due to the way people decide whether to evacuate. For example, 97% (n = 131) of the respondents (n = 135) who considered this as one of the reasons took precautionary measures after receiving warnings during Mora. If they did not believe the warnings, they would not have taken precautionary measures. Most people follow a wait-and-see approach until they believe that they can no longer stay at home due to the heavy rain, severe wind, or storms [10,21,32,33]. Thus, although they do believe warnings, they stay at home after packing their important belongings and observe the weather and regularly monitor cyclone updates to decide whether they need to take safe refuge. Because they think that they can reach the cyclone shelter or other places they consider safe within a very short period, they wait at home until they think that the cyclone will reach landfall. They consider evacuation as the last precautionary measure and take some other precautionary measures even though they do not evacuate. Two important factors that encourage them to stay at home are the limited space in the cyclone shelter or other safe buildings and the difficulty of moving to safe places with their belongings. As roads are poor or muddy, people need to carry their belongings by themselves. However, they all plan to go to the safe place if the situation worsens. As the weather situation during Mora was not so severe despite both the villages being under signal number 8, they thought that the cyclone would not occur near them, and thus they did not take shelter in any place other than own house.

A fatalistic attitude is another important reason that discourages people from taking shelter in safe places [11,26,27,28,31]. About 56.1% (n = 110) of the respondents from non-evacuee households (n = 196) mentioned ‘the cyclone is Allah’s/God’s will, so He will save us’ as one of the reasons for not taking refuge:

I did not go to the cyclone shelter because if I am destined to die, then I will die whether I go to the cyclone shelter or stay at home.(Dakshin Bedkashi, 11 July 2017).

If Allah saves someone, no one can kill him and if Allah does not save someone, then no one can save him. Going to the cyclone shelter is the same as staying at home. If Allah keeps me alive, He will keep me alive if I go to the cyclone shelter or if I stay at home. For this I do not go to the cyclone shelter. I stay at home believing in Allah.(Dakshin Bedkashi, 9 July 2017).

However, many people believe that although Allah/God will decide everything, they must take necessary measures to ensure their safety, as Allah will not help them if they do not help themselves. A typical comment was “Allah saves us, but we cannot survive if we do not try”.(Dakshin Bedkashi, 10 July 2017).

The distance to the nearest cyclone shelter also acts as an important reason for not taking refuge in a safe place [9,10,11,21,28,31,34]. About 41% (n = 80) of the respondents from non-evacuee households (n = 196) mentioned that this was one of the reasons for not taking refuge:

If we had a cyclone shelter nearby, we would have gone to the cyclone shelter. The shelter is 40 to 42 min walking distance from my house. Is it possible to go?(Channirchak, 23 August 2017).

Previous studies suggest that the nearest cyclone shelter should be located within 1.5 km or 1–2 km of residences, as people do not have enough time to reach the cyclone shelter by the time they decide to leave their house [7,9,11,31,34]. However, the analysis of qualitative data shows that although too much distance between the cyclone shelter and residence acts as a barrier to evacuation, too little distance does not itself guarantee taking refuge in a cyclone shelter. In both villages, many of the residents who live close to the cyclone shelter do not go to it as they optimistically think that they can easily go there if the storm becomes violent. Roy et al. [21] (p. 297) also observed this phenomenon. However, some of the residents who are far away from the cyclone shelter do go to the shelter as they are worried that they will not be able to reach the shelter if any problem arises.

The optimistic attitude of people who live close to a shelter is dangerous. During Cyclone Aila, many people living close to the cyclone shelter or safe building could not reach them by the time they left their house, as the village became flooded very quickly. The optimistic attitudes can be seen in the following interview excerpts:

This [the Union Parishad building] is very close to us. If Allah creates such a situation [that compels to take refuge in other place], then we can go this distance.(Dakshin Bedkashi, 17 June 2017).

Many people do not come to the cyclone shelter because the cyclone shelter is far away from their residence. Many people [of the east neighbourhood of the village] need to walk about two to three kilometres to reach the cyclone shelter. So, they do not want to come to the cyclone shelter. Many people living close to the cyclone shelter also do not come [to the cyclone shelter] … Those who live within five to ten minutes walking distance of the cyclone shelter, they think that the cyclone shelter is located a little distance from us. They think that we can go this distance when danger comes … Many of them get into trouble for this delay. Although people from the distant place can come to the cyclone shelter, people living close to the cyclone shelter cannot come to the cyclone shelter due to their procrastination and thus fall into trouble as they cannot go to the cyclone shelter at the last moment.(A key informant from the village who worked for an NGO, Channirchak, 9 June 2017).

‘Poor road access to the cyclone shelter’ was a reason for 39.3% (n = 77) of the non-evacuee households (n = 196) for staying at home, as found in previous studies [21,28,31]. A part of each study village was not well connected to the cyclone shelter because road damage by Cyclone Aila was not repaired at the time of fieldwork in April 2019. People in both the villages usually need to walk to the shelter and carry their belongings as the roads are not suitable for buses or cars. Although motorcycles and vans use the roads on sunny days, most of the roads in both the villages become muddy and impassable if there is rain.

‘Consideration of own house as a safe place’ was one of the reasons for staying home for 29.1% (n = 57) of the non-evacuee households, as has been found in other studies [10,21,26,27,28,31,34]. Although consideration of houses as safe places deters people from moving to safe places, the consideration of houses as safe places can also protect ‘ontological security’ and hence the mental health of people at risk [35,36]. People relinquish the representation of houses as safe places when they experience hazard events such as cyclones damaging their house. While some may react to the loss of representation of houses as safe places by taking protective actions, others may lose their ‘ontological security’ and as a result, may experience mental distress. Thus, the mental suppression of the awareness of the risk by people in harm’s way can protect their ontological security and hence their mental health [35]. ‘Fear of burglary’ also appeared as an important reason that discouraged people in both villages to move to safe places in 25.2% of non-evacuee households. Other studies in Bangladesh also found this [10,11,21,26,27,28,31,33,34]. In households where some members take shelter in other places, a male member usually stays at home to protect a household’s items and valuables from being stolen [33]. The following quotes show the impacts of the fear of burglary:

[We] went to the cyclone shelter two or three times after Cyclone Aila. My son stayed at home and I along with my daughter-in-law and grandson went to the cyclone shelter. My son stayed at home to protect things as people could steal things [if nobody stays at home].(A widow female interviewee, Dakshin Bedkashi, 17 June 2017).

I stay at home as there are some items such as rice, shopped items, and other household items at home. Thief can steal these things at night.(An interviewee who stays at home although he sends all his household members to the cyclone shelter or other safe place, Dakshin Bedkashi, 6 August 2017).

I am afraid of my house being burgled. [If I go to the cyclone shelter], my goats and household items would be stolen.(Dakshin Bedkashi, 1 August 2017).

‘Warnings on previous occasions but nothing happened’ was one of the reasons for 19.9% (n = 39) of the respondents of the non-evacuee households (n = 196) for not taking refuge in any place other than their own house. Moreover, ‘taking refuge in the cyclone shelter or other safer places during warnings for previous cyclones but nothing happened’ was a reason for about 6.6% (n = 13) of respondents (n = 196). These two reasons are directly related to people’s experience of warnings on previous occasions. Although they received warnings on previous cyclones such as for Cyclone Viyaru, Cyclone Komen, and Cyclone Roanu, these cyclones changed their course to hit elsewhere or did not cause any significant damage in both the villages. It is worth mentioning that the Khulna District was under signal number 5 during both Cyclone Viyaru and Cyclone Komen and under signal number 7 during Cyclone Roanu [37,38,39].

Earlier studies have argued that people ignore the warnings due to experiencing false warnings on previous occasions [10], causing disbelief in the warnings [10,27,28,32,34]. However, the present study suggests that this is not the case. For instance, 95% (n = 37) of respondents who mentioned ‘received warnings on previous occasions but nothing happened’ as one of the reasons for not taking refuge (n = 39) took precautionary measures after receiving the warnings. Similarly, all the respondents (n = 13) who mentioned ‘took refuge in the cyclone shelter or other safer places during warnings for cyclones after Cyclone Aila but nothing happened’ also took precautionary measures after receiving warnings. Thus, although the cyclone did not hit on previous occasions, they believed the warnings. Otherwise, they would not have taken precautionary measures after receiving the warnings. This can also be understood from the fact that only 1.5% of the non-evacuee households mentioned disbelief in the warning as one of the reasons for not taking refuge. This contradicts previous studies that found disbelief in the warning as one of the major factors for not taking refuge [10,26,27,28,31,34]. For instance, Paul’s [10] study on Sidr found that about 19% of the non-evacuees did not believe the warnings. Likewise, Haque’s [27] study found that of household heads who stayed home after receiving warnings, 53.2% (n = 74) of urban household heads (n = 139) and 58.9% (n = 56) of rural household heads (n = 95) mentioned disbelief in the warning as one of the reasons.

People’s belief in warnings despite not taking refuge might be explained by their experience with Cyclone Aila and the widespread training inhabitants of both the villages received on disaster preparedness from the government and NGOs in the post-Aila period. Both the villages were under danger signal number 7 during Cyclone Aila, and people from both the villages ignored the warnings. However, they experienced a disastrous situation contrary to their expectation. After that, the government brought both the villages under CPP coverage and trained some of the villagers to serve as CPP volunteers. Moreover, NGOs provided training to a representative from almost all households in both the villages on cyclone preparedness in the post-Aila response and recovery period. NGOs also trained village-level volunteers to disseminate warnings and help people to evacuate to safe places, and to participate in the search and rescue operations after a cyclone. Thus, people now usually understand that although on some occasions a cyclone might not affect their village despite warnings, because the track of the cyclone might change, they must not ignore the warnings, as the cyclone might not change its course and thus can hit their villages.

‘So many people in the cyclone shelter’ was one of the reasons for about 18.4% (n = 36) of the respondents of the non-evacuee households for staying at home after they received warnings. The typical response from the qualitative interviews was ‘I do not like to go to the cyclone shelter as it becomes overcrowded’ (Dakshin Bedkashi, 5 August 2017). Other studies also found that ‘too many people’ act as a barrier for taking shelter [10,26,27,33,34]. Comments from the current study reflect this:

People do not go to cyclone shelter because they do not get space in the cyclone shelter if they go. Thus, they arrange alternatives. It seems that 2000 people require to take shelter in the cyclone shelter but the cyclone shelter has space for 500 people. So how can people go there?(Dakshin Bedkashi, 18 June 2017).

Although it [not taking shelter in cyclone shelter or safe buildings] is a bad practice, what would people do? Cyclone shelter and other public buildings can accommodate 10 people, but the village has 50 people. Where would the rest of the people take refuge?(Dakshin Bedkashi, 11 July 2017).

I took refuge two times after Aila on the embankment…. Cyclone shelter is far away from our home. The shelter becomes full of people by the time we try to reach the shelter.(Dakshin Bedkashi, 10 July 2017).

Only 3.5% of non-evacuee households in Channirchak and 24.5% in Dakshin Bedkashi considered ‘so many people in the cyclone shelter’ as a reason for not going to a shelter. Neither of the villages have adequate buildings (cyclone shelters and other buildings) compared to the population that needs to take refuge. Channirchak has only one school-cum-cyclone shelter, which was built after Cyclone Aila by the government, within the village. Many people from the village and other adjacent villages take shelter here. However, many people from one part of Channirchak go to another school-cum-cyclone shelter, which was also built after Cyclone Aila by an NGO, in the adjacent village; they do not go to the cyclone shelter in their own village due to the poor roads.

Although lack of space in the cyclone shelter is a problem in Channirchak, the problem is severe in Dakshin Bedkashi. The cyclone shelter and all other buildings used as shelters in Dakshin Bedkashi cannot accommodate all of the village inhabitants. Moreover, people from other adjacent villages also take refuge in these buildings. The lack of space can be understood from the following interviewee:

Maximum 25 to 30% of the total population of our village can take shelter in all the buildings of the village [except private house]. This village has more buildings within the union. At union level, maximum 10% of the total population of the union can take shelter in all the buildings [cyclone shelter, school and all other buildings that can be used for taking shelter; except private house] of the union.(This interviewee included the new school building built after Mora in his estimation, Dakshin Bedkashi, 11 July 2017).

A lack of facilities in the cyclone shelter also discourages people from taking refuge [7,9,10,34]. About 8.2% (n = 16) of the non-evacuee households considered a lack of drinking water, lights, and toilets in the cyclone shelter as a reason for not taking refuge in any place other than one’s own house. While none of the non-evacuee households of Channirchak considered lack of facilities in the cyclone shelter as one of the reasons, 11.5% of the non-evacuee households in Dakshin Bedkashi did. This is because the newly built primary school-cum-cyclone shelter in Channirchak and the newly built school-cum-cyclone shelter in the adjacent village, which is used as a shelter by many people in part of the village, have water, lights (solar), and toilets inside the shelter building. On the other hand, the cyclone shelter in Dakshin Bedkashi is old. Although it was repaired by an NGO after Cyclone Aila, it does not have lights, and the tube well and toilets are located outside the building. Another reason for non-compliance with evacuation orders was the lack of a separate space and toilet for women in the cyclone shelter [7,9,10]. About 5.1% (n = 10) of the respondents from non-evacuee households mentioned this. In Bangladeshi culture, women do not usually want to stay with unknown men in the same room [34]. Many Muslim women maintain purdah (curtain), and thus, they want a separate space to avoid non-related adult men [7,9,33]. The following statement from a female interviewee depicts the issues:

The environment in the cyclone shelter is not good, there is also problem of bathroom. Many people come there [overcrowded]. Men and women need to stay together. Many men come there who are not of good character.(Dakshin Bedkashi, 1 August 2017).

While none of the respondents from non-evacuee households in Channirchak considered lack of separate space and toilets for women in the cyclone shelter as one of the reasons for not evacuating, 7.2% of the respondents of the non-evacuee households in Dakshin Bedkashi did consider this as one of the reasons. This might be because both of the newly built cyclone shelters in Channirchak and the adjacent village have multiple rooms and more than one toilet inside the building (the shelter in Channirchak has four toilets, and the shelter in the adjacent village has two toilets). Thus, women and men can use separate rooms and toilets if they require them. The cyclone shelter in Dakshin Bedkashi, on the other hand, has only one big room, and the two toilets (in dilapidated condition due to poor maintenance and repair) are located outside the building.

People who have livestock also feel discouraged to move to safer places as they cannot move with their cattle, on which their livelihood is dependent [7,9,33]. Overall, 3.1% of the surveyed respondents mentioned that ‘no place for keeping livestock in the cyclone shelter’ was one reason for not moving to a safe place after receiving the warnings. The low figure for this reason can be explained because among non-evacuee households (n = 196), about 63% (n = 123) and 78% (n = 152) did not have sheep/goats and cows, respectively, during the survey period, which was almost six-and-a-half months after Mora. As an interviewee who owns cattle said:

If our cattle perish, then there is no benefit even if I survive. I could have gone to the cyclone shelter if I could keep my cattle in a secured place … I could at least survive even if I can save three out of five cows and two cows die … The space in the shelter for keeping cattle is less. If you go with 10 [cows], there is no place there for others to keep their cows.(Channirchak, 10 June 2017).

6. Discussion and Recommendations

This study shows that although households usually take some precautionary measures in response to warnings, most take a wait-and-see approach. A noticeable finding is that disbelief in the warnings is not an important reason for non-compliance with the evacuation orders. Moreover, the thought that a cyclone will not occur near their own house is linked to the way people decide to evacuate. When people follow a wait-and-see approach and keep an eye on a cyclone’s course, they believe that they will know when the weather becomes bad enough to turn into a cyclone. The study also shows that the fatalistic attitude of the people at risk still plays an important role in determining the success in the evacuation outcome. This suggests that people at risk use non-rational strategies such as belief or faith to manage risk. Thus, acknowledgement and recognition of the strategies that are not fully rational but are used by people in harm’s way to deal with risk will be helpful for addressing the issue of non-compliance with the evacuation orders [40].

Although greater distance between the residence of respondents and the nearest cyclone shelter acts as a barrier to evacuation, a shorter distance does not itself guarantee that residents will evacuate to a shelter. People living close to a cyclone shelter not only follow a wait-and-see approach but also optimistically think that they can reach the shelter quickly if there is any problem. However, they usually do not leave themselves enough time to walk even a short distance by the time they decide to go to safe places. Additionally, as they usually need to carry their belongings, they feel less inclined to go because there is no good road network. As a substantial part of each village is not well connected to the shelter located within the village, ‘poor road network’ appeared as a very important reason for not seeking refuge.

Unlike previous studies, this study shows that although warnings that did not translate into emergencies on previous occasions do influence evacuation behaviour, they do not create mistrust in the warnings; people are aware that the projected cyclone might not affect their place sometimes despite warnings, as the cyclone might change its course. This type of development is linked to their lived experience and the trainings that household members and community people received from the government and NGOs after Aila and the inclusion of the area under CPP coverage. The lack of facilities, a separate space and toilet for women, and a place for keeping livestock in the cyclone shelter also discouraged people to evacuate to places other than their own house.

To address the issue of non-compliance with warnings and evacuation orders, more cyclone shelters should be constructed; having more small cyclone shelters is preferable to having fewer large ones. As most people decide to go to the cyclone shelter at the last moment, shelters should be located within 1–2 km, preferably not more than 1.5 km, from people’s homes, so that they can easily move to the shelter during an emergency [7,11,34]. Shorter distances would also lessen anxiety about houses being burgled. In addition, shelters should be constructed on a site that is well connected to all sides of the village and to elevated roads. Moreover, all cyclone shelters (existing and new) should have basic amenities, such as water, lights, and toilets [7,41] and separate rooms and toilets for men and women [7,41,42]. More killas (raised earthen platforms) should be constructed in the same compound as the cyclone shelters, as people do not want to keep their cattle in distant killas; this distance acts as a barrier to evacuation [7,10,41]. Rich coastal households should also be encouraged and given special loans with little interest to build cyclone-resistant two-story houses that can be used as mini cyclone shelters [41].

Warnings should include sufficient information such as certainty of the cyclone making landfall, approximate location of the area of landfall, approximate time of impact, areas that would be most affected, duration of cyclonic wind, and time by which people must take protective action [7,21]. People in warning areas should also be briefed if any cyclone does not strike the area, despite the warnings issued for that area.

As people wait until the last moment to leave their house, they need to be educated to take shelter in safer places in time through awareness-raising campaigns. As a fatalistic attitude is a major issue, awareness-raising programs should use religious leaders and references from religious scriptures to encourage people to take safe refuge when they are instructed to do so. Measures should also be taken to ensure the safety of the property left at the house from being looted when people take shelter in safe places. Moreover, regular cyclone drills need to be arranged to make people aware of evacuation procedures as part of disaster preparedness activities.

The Sendai Framework aims to lower global disaster mortality considerably by 2030 [3]. To meet this target, Bangladesh needs to minimise the potential loss of life from cyclones by ensuring that people at risk respond properly to warnings and evacuation orders. As receiving warnings alone does not result in compliance with evacuation orders, the cyclone warning systems need to factor in human responses as part of their operational design in order to achieve better outcomes.

7. Conclusions

The effectiveness of cyclone warnings to enable people to take safety measures is vital for preventing deaths, injuries, and loss of livelihoods. While this research focussed on Bangladesh, similar risks from cyclones exist in coastal regions in other parts of the world. The results from this case study suggest ways in which the concerns of residents in cyclone-prone regions in developing countries may be addressed to develop more effective warning systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: S.K.S.; Methodology: S.K.S.; Data transcription: S.K.S.; Software: S.K.S.; Formal analysis: S.K.S.; Investigation: S.K.S.; Resources: S.K.S.; Data curation: S.K.S.; Writing—S.K.S.; Writing—review and editing: S.K.S. and J.P.; Visualisation: S.K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The first author was awarded an Endeavour Postgraduate Scholarship (PhD) by the Australian Government and a Postgraduate Research Scholarship by the Australian National University (ANU), Australia. He was also awarded Fieldwork and Discretionary funding as a PhD student from the School of Culture, History and Language, the Australian National University, Australia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The ethical aspects of this research have been approved by the Australian National University Human Research Ethics Committee (Protocol 2017/115).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this paper are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support and guidance for this research from the late Helen James, as well as Chris Ballard. The authors would also like to acknowledge the valuable comments of the anonymous reviewers on the original manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRCRCS). World Disasters Report: Focus on Early Warning, Early Action; IFRCRCS: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- World Meteorological Organization (WMO). The Second Multi-hazard Early Warning Conference (MHEWC-II). 2021. Available online: https://mhews.wmo.int/en/about (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. 2015. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/files/43291_sendaiframeworkfordrren.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- United Nations (UN). Report of the World Conference on Disaster Reduction. World Conference on Disaster Reduction; UN: Kobe, Japan, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- United Nations (UN). Paris Agreement; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, S.K.; James, H. Reasons for non-compliance with cyclone evacuation orders in Bangladesh. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 21, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyclone Preparedness Programme (CPP). Bangladesh, 2021. Available online: http://www.cpp.gov.bd/ (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Ahsan, N.; Takeuchi, K.; Vink, K.; Warner, J. Factors affecting the evacuation decisions of coastal households during Cyclone Aila in Bangladesh. Environ. Hazards 2015, 15, 16–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, B.K. Factors affecting evacuation behavior: The case of 2007 Cyclone Sidr, Bangladesh. Prof. Geogr. 2012, 64, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, B.K.; Rashid, H.; Islam, M.S.; Hunt, L.M. Cyclone evacuation in Bangladesh: Tropical cyclones Gorky (1991) vs. Sidr (2007). Environ. Hazards 2010, 9, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRCRCS). Bangladesh: Cyclone Mora; Information Bulletin, MDRBD019, Date of Issue: 7 June 2017; IFRCRCS: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/IBBDTC070617.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Hong Kong Red Cross. Bangladesh Cyclone Mora 2017: Work Report 1. 2017. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/bangladesh/bangladesh-cyclone-mora-2017-work-report-1 (accessed on 13 August 2021).

- Daily Star. 7 Die as Cyclone Mora Crosses Coastal Area. 2017. Available online: https://www.thedailystar.net/frontpage/devastation-not-much-feared-1413238 (accessed on 13 August 2021).

- Saha, S.K.; Ballard, C. Cyclone Aila and post-disaster housing assistance in Bangladesh. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.K. Cyclone Aila, livelihood stress, and migration: Empirical evidence from coastal Bangladesh. Disasters 2017, 41, 505–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Daily Star. Water Development Board: Autonomy Gone, Efficiency Too. 2020. Available online: https://www.thedailystar.net/backpage/news/water-development-board-autonomy-gone-efficiency-too-1996721 (accessed on 23 May 2021).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roy, C.; Sarkar, S.K.; Aberg, J.; Kovordanyi, R. The current cyclone early warning system in Bangladesh: Providers’ and receivers’ views. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2015, 12, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bangladesh Meteorological Department (BMD). Signals. 2014. Available online: http://bmd.gov.bd/?/p/=Signals (accessed on 31 December 2020).

- Bangladesh Meteorological Department (BMD). Special Weather Bulletin: Sl. No. 15 (Fifteen); Storm Warning Center, BMD; Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2017.

- Daily Star. Cyclone Mora: ‘Great Danger’ Signal 10 at Ctg, Cox’s Bazar Ports. 2017. Available online: https://www.thedailystar.net/country/cyclone-mora-chittagong-coastal-people-asked-move-shelters-bangladesh-1412551 (accessed on 12 May 2018).

- Ministry of Disaster Management and Relief (MoDMR). Standing Orders on Disaster 2019; Ministry of Disaster Management and Relief, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2019.

- Haque, C.E.; Blair, D. Vulnerability to tropical cyclones: Evidence from the April 1991 Cyclone in coastal Bangladesh. Disasters 1992, 16, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, C.E. Climatic hazards warning process in Bangladesh: Experience of, and lessons from, the 1991 April Cyclone. Environ. Manag. 1995, 19, 719–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.K.; Routray, J.K. An Analysis of the causes of non-responses to cyclone warnings and the use of indigenous knowledge for cyclone forecasting in Bangladesh. In Climate Change and Disaster Risk Management; Filho, L.W., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 15–39. [Google Scholar]

- Mallick, B. Cyclone shelters and their locational suitability: An empirical analysis from coastal Bangladesh. Disasters 2014, 38, 654–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, S.K. Cyclone, Salinity Intrusion and Adaptation and Coping Measures in Coastal Bangladesh. Space Cult. India 2017, 5, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paul, S.K. Determinants of evacuation response to cyclone warning in coastal areas of Bangladesh: A comparative study. Orient. Geogr. 2014, 55, 57–84. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, A.M.R.; Bhuyia, A.U.; Choudhury, A.Y.; Sen, R. The Bangladesh Cyclone of 1991: Why so many people died. Disasters 1993, 17, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeda, K. Gender differences in human loss and vulnerability in natural disasters: A case study from Bangladesh. Indian J. Gend. Stud. 1995, 2, 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, B.K.; Dutt, S. Hazard warnings and responses to evacuation orders: The case of Bangladesh’s Cyclone Sidr. Geogr. Rev. 2010, 100, 336–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harries, T. Feeling secure or being secure? Why it can seem better not to protect yourself against a natural hazard. Health Risk Soc. 2008, 10, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harries, T. Ontological security and natural hazards. In The Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Natural Hazard Science; Cutter, S.L., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Disaster Management Information Centre (DMIC). Situation Report; Issue 28, 15 May 2013; Ministry of Disaster Management and Relief: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Disaster Management Information Centre (DMIC). Cyclonic Storm (Komen) Situation; 30 July 2015; Ministry of Disaster Management and Relief: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRCRCS). Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) Bangladesh: Cyclone Roanu; Date of Issue: 24 May 2016; IFRCRCS: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zinn, J.O. Heading into the unknown: Everyday strategies for managing risk and uncertainty. Health Risk Soc. 2008, 10, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.K. Social Capital and Post-Disaster Response and Recovery: Cyclone Aila in Bangladesh, 2009. Ph.D. Thesis, The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tatham, P.; Oloruntoba, R.; Spens, K. Cyclone preparedness and response: An analysis of lessons identified using an adapted military planning framework. Disasters 2012, 36, 54–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).